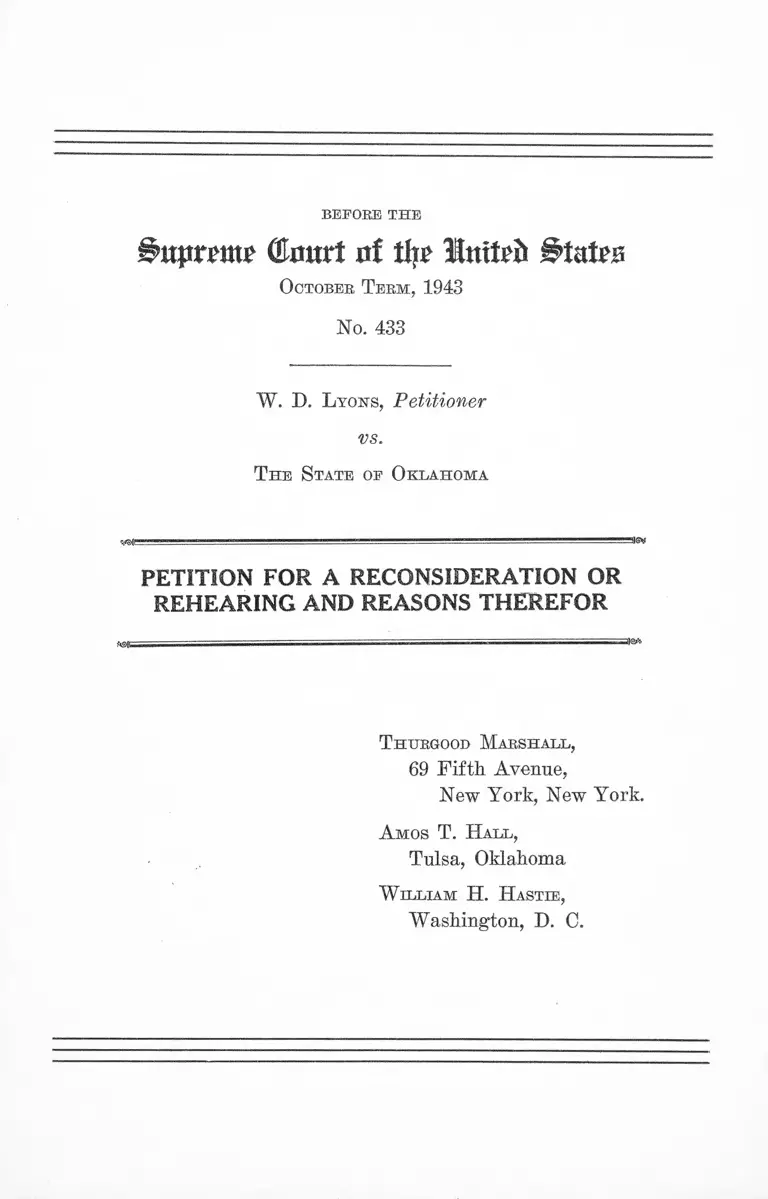

Lyons v The State of Oklahoma Petition for a Reconsideration or Rehearing and Reasons Therefor

Public Court Documents

June 5, 1944

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lyons v The State of Oklahoma Petition for a Reconsideration or Rehearing and Reasons Therefor, 1944. 4d6a112f-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/81572c0a-68af-4aad-955a-7bc9f4d69416/lyons-v-the-state-of-oklahoma-petition-for-a-reconsideration-or-rehearing-and-reasons-therefor. Accessed February 19, 2026.

Copied!

B E F O R E T H E

(tort rtf tin lnttr& itora

October Teem, 1943

No. 433

W . D. L yons, Petitioner

vs.

T he State of Oklahoma

PETITION FOR A RECONSIDERATION OR

REHEARING AND REASONS THEREFOR

T hoegoot) Marshall,

69 Fifth Avenue,

New York, New York.

A mos T. H all,

Tulsa, Oklahoma

W illiam H. H astie,

Washington, D. 0.

B E F O R E T H E

irtpmnp (tart at tljr Wnltib BUUn

October Term, 1943

No. 433

W. D. L yons, Petitioner

vs.

T he State of Oklahoma

PETITION FOR A RECONSIDERATION

OR REHEARING

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice and the Associate Jus

tices of the Supreme Court of the United States:

Comes now the petitioner herein and presents this peti

tion for a reconsideration or rehearing* and for the vacating

of the judgment of this Court affirming a judgment of the

Criminal Court of Appeals of the State of Oklahoma.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of this Court herein prayed to be recon

sidered was entered on the 5th day of June, 1944. This

petition for a reconsideration or rehearing is filed within

twenty-five days from June 5, 1944, in accordance with Rule

33 of this Court.

2

Reasons for Petition

I. The decision herein conflicts with a decision o f this

Court in Brown v. Mississippi, yet the opinion herein fails to

mention the Brown case.

In Brown et at. v. Mississippi, 297 U. S. 278 (1936), the

issue before this Court was essentially the same as in the

present case. There prisoners were tortured by police

officers and thus forced to confess. A day later they were

taken before other public officials and reputable private

citizens, none of whom had been party to the prior wrong

doing, and in peaceful surroundings free from all indicia

of coercion, were permitted to give “ voluntary” confessions.

This Court, in its opinion, described the situation by quot

ing, with approval, the following language from the dis

senting opinion of the Supreme Court of Mississippi:

“ All this (the extortion of the first confession)

having been accomplished, on the next day, that is,

on Monday, April 2, when the defendants had been

given time to recuperate somewhat from the tortures

to which they had been subjected, the two sheriffs,

one of the county where the crime was committed,

and the other of the county of the jail in which the

prisoners were confined, came to the jail, accom

panied by eight other persons, some of them deputies,

there to hear the free and voluntary confession of

these miserable and abject defendants. The sheriff

of the county of the crime admitted that he had heard

of the whipping, but averred that he had no personal

knowledge of it. He admitted that one of the defen

dants, when brought before him to confess was limp

ing and did not .sit down, and that this particular

defendant then and there stated that he had been

strapped so severely that he could not sit down, and

as already stated, the signs of the rope on the neck

of another of the defendants were plainly visible to

all. Nevertheless the solemn farce of hearing the

3

free and voluntary confessions was gone through

with, and these two sheriffs and one other person

then present were the three witnesses used in court

to establish the so-called confessions, which were re

ceived by the court and admitted in evidence over

the objections of the defendants duly entered of rec

ord as each of the said three witnesses delivered their

alleged testimony” (297 U. S. at 282-3).

In these circumstances this Court considered it too clear

to require extended discussion that the prisoners could not

have been free from the coercive effect of the violence which

attended the first confessions at the time of the second con

fessions. Convictions obtained through the use of these

“ voluntary” confessions were held to deny due process of

law.

In the present ease, the coercion attending the first con

fession was so clear and gross that the inadmissibility of

that confession has been conceded throughout the trial and

subsequent appeals. Its great immediate effect upon the

prisoner being admitted, the necessary inference of some

substantial continuation of that effect exists here as in the

Brown case. Hence, it becomes pertinent to inquire whether

any circumstances intervening between the first and second

confessions or attending the second confession distinguish

the two cases.

A longer time elapsed between the first and second con

fessions in Brown v. Mississippi than in the present case.

The prisoners there at least had a night’s rest and twenty-

four hours to regain their composure. Here the brutal in

quisition of the early morning hours normally devoted to

rest was followed by the second confession on the same day.

There is no significant difference between the circumstances

immediately attending the second confessions in the two

cases. Indeed, in the Brown case, the absence of any coer

4

cive conduct at the time of the second confession and the

absence of the parties who extorted the first confession are

admitted. Thus, it is even clearer there than here that the

only coercive influence in question was the violence to which

the prisoners had previously been subjected—violence from

the effects of which Brown had a better and longer oppor

tunity to recover than did petitioner.

In the matter of trial procedure the cases are substan

tially alike. In each case the Trial Judg*e admitted the con

fession and then charged that it should be disregarded if the

jury had reasonable doubt as to its voluntary character. In

the Brown case this Court concluded that the finding of the

Trial Court and jury that the prisoners were free from

coercion was so patently unreasonable as to offend basic

notions of fair trial. Yet, in the present case this Court

concluded that reasonable men might differ on the issue of

whether or not the defendant was free from coercive influ

ence when he made the second confession.

It is respectfully submitted that these two decisions are

irreconcilable. Despite this conflict no mention of the

Brown case appears in the present opinion. It is believed

that the doctrine of the Brown case is sound and salutary,

and that it should not be rejected sub silentio or otherwise.

In the interest of justice and to clarify an important issue

likely to recur frequently in the administration of criminal

justice, reconsideration of the decision herein is prayed.

II. This Court should reexamine its conclusion that the

denial o f a specific instruction directing the attention o f the

jury to the relation o f prior coercion to the second confession

involved no issue o f due process.

In the opinion herein this Court examined the general

instruction of the Trial Court to the effect that a confession

5

obtained by force, intimidation or threats is inadmissible.

The opinion also takes cognizance of the fact that the Trial

Judge denied petitioner’s request for a specific instruction

that, if the second confession was influenced by fear en

gendered by the treatment at the time of the first confession,

then the second confession must be disregarded. The Court

then concluded that no essential element of fair trial re

quired this specific instruction. This conclusion should be

reexamined.

The effect of the brutality attending the first confession

upon the prisoner’s mind twelve hours later was a critical

issue in this ease. I f the resolution of this issue was a

matter upon which there could have been reasonable dif

ferences of opinion, it was all important that the jury under

stand precisely the question for its decision. The outcome

of a trial for a capital felony here depended upon the jury ’s

decision as to the mental carry-over of fear and compulsion

from one occasion to another in circumstances under which

human experience shows the very great probability of such

carry-over. The very minimum requirement of a fair trial

is that the minds of the jury be directed specifically to this

issue.

This ease does not involve a “ mere error” in a jury

verdict. This case presents a situation which is clearly in

consistent with the fundamental principles of liberty and

justice. A person who is on trial for his life or liberty

should be entitled to concrete, specific instructions to the

jury, which will fully and clearly articulate the dramatic

and fully alive situation to which he is exposed. The test

of due process does not lie in vague generalities, but in con

crete situations. In so far as the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment has in it any life, it has that life

by virtue of its application by this Court to specific, con

crete, factual situations.

6

Further evidence that the specific instruction which the

Court refused to give involved a fundamental issue of fair

trial is to be found in the verdict of the jury. The jury

had before it uncontroverted evidence of an atrocious mur

der without any circumstances of mitigation whatever. Yet

the jury did not impose the death penalty. This verdict is

explicable only on the theory that the jury under the general

instructions given erroneously believed that the circum

stances immediately surrounding the second confession con

sidered alone made it admissible, but the continuing coercive

influence of the earlier event was too obvious to permit the

imposition of the death penalty on such untrustworthy evi

dence.

The specific instruction requested was essential to make

clear to the jury their duty in the premises and thus to

assure the petitioner the substance of fair trial.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons petitioner respectfully urges

that a rehearing be granted and that upon further considera

tion the judgment of June 5, 1944, affirming the judgment

of the lower court in this cause, be set aside.

Respectfully submitted,

T hurgood Marshall,

69 Fifth Avenue,

New York, New York.

A mos T. H all,

Tulsa, Oklahoma

W illiam H. H astie,

Washington, D, C.

I, T htjkgood Marshall, attorney for the petitioner, W. D.

Lyons, do hereby certify that the foregoing petition for re

hearing of this cause and for vacating the order reversing

the judgment of the lower court is presented in good faith

and not for the purpose of delay.

T huegood Marshall,

Attorney for Petitioner.

[3701]

L awyers P ress, I nc., 165 William St., N. Y . C .; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300