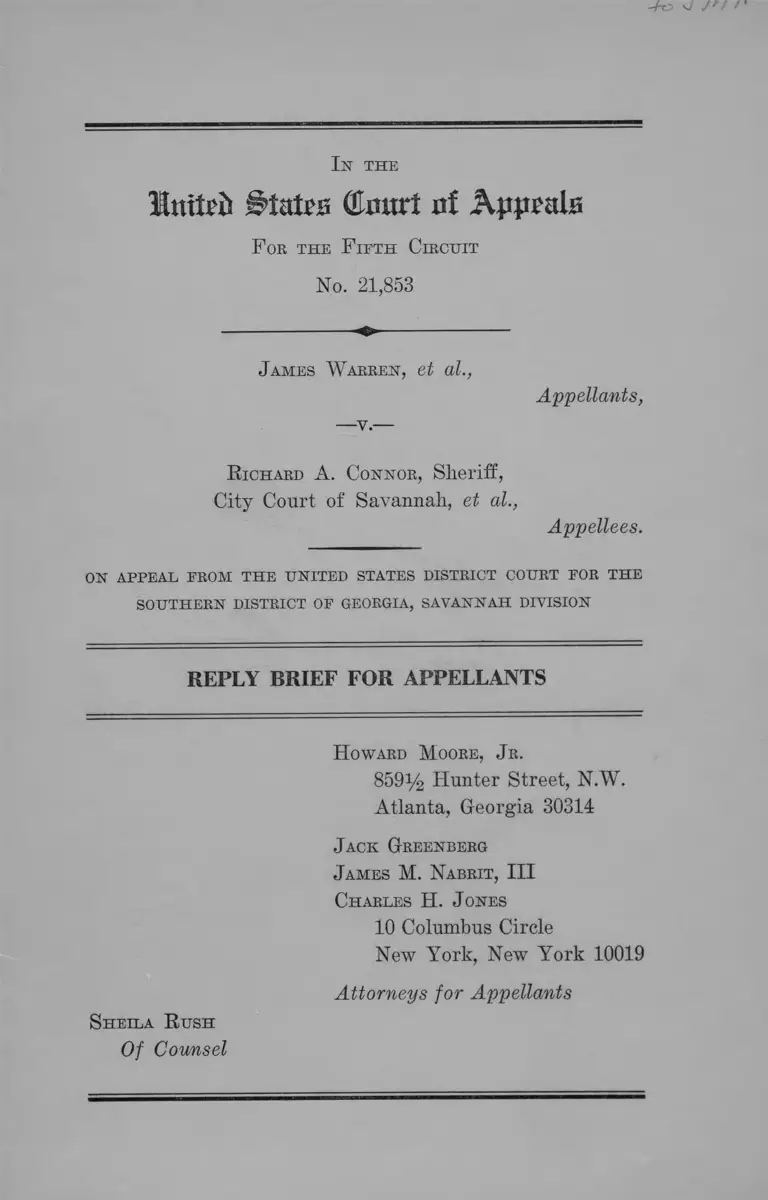

Warren v. Connor Reply Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Warren v. Connor Reply Brief for Appellants, 1965. e433c97e-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/818a805e-78d0-4d6b-9543-5073b43f7335/warren-v-connor-reply-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

InttfJj States (Emort of Appeals

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 21,853

James W arren, et al.,

•v.-

Appellants,

R ichard A. Connor, Sheriff,

City Court of Savannah, et al.,

Appellees.

OUST APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA, SAVANNAH DIVISION

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

H oward M oore, Jr.

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Charles H . J ones

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

S heila R ush

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

A rgument ......................................................................................... 1

Conclusion ......................................................................... 12

T able op Cases

Cobb v. Balkcom, 339 F. 2d 95, 100-01 (5th Cir. 1964) .. 5

Dilworth v. Riner, 343 F. 2d 226 (1965) ....................... 8

Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391.................................................. 2,5

Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379 U. S. 306 .......................... 5, 6, 7, 8, 9

Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U. S. 618.................................. 6

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. S. 643 .............................................. 6

Tolg v. Grimes, 5th Cir., No. 21661 .................................. 5

Wallace v. Foster, 1950, 206 Ga. 561, 57 S. E. 2d 920 .... 3

Wells v. Pridgen, 1922, 154 Ga. 397, 114 S. E. 355 (342

F. 2d at p. 391) ............................................................... 3

Whippier v. Balkcom, 342 F. 2d 388 (5th Cir.

1965) ...........................................................................1,2, 3, 4

11

PAGE

S tatutes

28 U. S. C. §2241(c)(3) .................................................. . 5,6

28 U. S. C. §2254 .............................................................. 2

42 U. S. C. §1981 .............................................................. 4

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 241...........5, 6, 8, 9,10,11

Ga. Code Ann., §26-3005 .................................................... 6

Other A uthorities

9

9

H. R. Report No. 914 (88th Cong. 1st Sess. 1963)

110 Cong. Rec. 6871 (daily ed. April 7, 1964) .....

110 Cong. Rec. 12999 (daily ed. June 11,1964) ..... . 10

In the

Unttrii States (Hour! of Appeals

F or t h e F i f t h C ir c u it

No. 21,853

J a m e s W a r r e n , et al.,

-v.-

Appellants,

R ic h a r d A. C o n n o r , Sheriff,

City Court of Savannah, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA, SAVANNAH DIVISION

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Argument

A. Whippier v. Balhcom, 342 F. 2d 388 (5th Cir. 1965)

squarely disposes of the two interrelated procedural grounds

upon which the district court relied in denying appellants’

federal habeas corpus petitions. United States District

Judge Scarlett remanded appellants to state custody, with

out hearing, upon the following bases:

. . . [1] The exhaustion of state remedies is a juris

dictional requirement in federal habeas corpus pro

ceedings . . . [2] The court finds that the [appellants]

presently have available to them the state remedy of

2

habeas corpus (Georgia Code 50-1) . . . State habeas is

an appropriate remedy when the trial court was with

out jurisdiction, or where it exceeded its jurisdiction

in making the order, rendering the judgment, or pass

ing the sentence by virtue of which the party is im

prisoned, so that such order, judgment, or sentence

is not merely erroneous, but is absolutely void (R. 61,

62).

Whippier, relying upon Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391, de

cided, first, that the exhaustion requirements of 28 U. S. C.

§2254 are not a limitation upon jurisdiction, but rather a

matter of comity (342 F. 2d at p. 390):

. . . In Fay v. Noia, 1963, 372 U. S. 391, 83 S. Ct. 822, 9

L. Ed. 2d 837, the Court struck down the highest bar

rier posed by the exhaustion principle, holding that a

state prisoner is never barred from federal habeas

corpus by mere failure to exhaust state remedies no

longer open to him (footnote omitted).

. . . The exhaustion principle is a matter of comity, not

‘a matter of jurisdiction. In federal habeas proceed

ings, jurisdiction is confirmed by the allegation of an

unconstitutional restraint and is not defeated by any

thing that may occur in the state court proceedings’.

Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. at 426.

Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. at 438-439, made it clear that a

trial judge lacks discretion to deny federal habeas relief

except to an applicant “ who has deliberately by-passed the

orderly procedure of the state courts.” As previously noted

(see Appellants’ Brief, p. 7), the trial court’s ruling did

3

not rest on any claim that appellants had deliberately by

passed state appellate review, but rather on the more cen

tral question, that Georgia habeas corpus was a remedy

available to review appellants’ federal constitutional claims.

Turning to this issue, in Whippier, supra, the Court of

Appeals held that resort to Georgia habeas corpus was not

necessary since Georgia law is settled against post-convic

tion review of claims other than “ deprivation of counsel” :

Habeas corpus in Georgia is a door that not every

constitutionally deprived prisoner can open.4 The

magic words are ‘deprivation of counsel.’ The applicant

who cannot say them may not pass. . . . The Georgia

rule is that habeas corpus cannot be used as a sub

stitute for appeal, writ of error, or other remedial pro

cedure for the correction of errors or irregularities al

leged to have been committed by a trial court. Wallace

v. Foster, 1950, 206 Ga. 561, 57 S. E. 2d 920. This

rule has been applied so strictly that the state is unable

to cite a single case in which the Georgia Supreme

Court, on habeas corpus, has held a judgment void on

any ground other than denial of counsel.

4 The general rule is that the judgment of a court having

jurisdiction of the offense and the party charged with its

commission is not open to collateral attack. [Citations omit

ted.] The remedy by habeas corpus should be confined to

cases in which the judgment or sentence attacked is clearly

void, by reason of its rendition by a court without jurisdic

tion in the premises, or by reason of the court’s having

exceeded its jurisdiction in the premises . . . [Citations omit

ted.] The denial of due process of law, although erroneous,

must be such as to deprive the court of jurisdiction. Wells

v. Pridgen, 1922, 154 Ga. 397, 114 S. E. 355 (342 F. 2d at

p. 391).

4

In Whippier, petitioner applied for federal habeas corpus

relief subsequent to prosecuting an unsuccessful appeal to

the Georgia Supreme Court. The district court denied re

lief for non-exhaustion, ruling that state habeas corpus was

available on three of petitioner’s five federal habeas claims,

which had never been presented to the Georgia Courts.1

The Court of Appeals, in reversing the district court’s

order, reasoned that even though several of petitioner’s

federal claims had not been presented on appeal in the state

system, Georgia habeas corpus has been so judicially cir

cumscribed as a post-conviction remedy, that petitioner

could be deemed to have exhausted his state remedies.

Appellants claim (see Appellants’ Brief, p. 6, fn. 1),

essentially, that §26-3005, Ga. Code Ann., facially, and as

applied runs afoul of Fourteenth Amendment due process

and equal protection guarantees, and violates 42 U. S. C.

§1981. Unlike an asserted deprivation of counsel, appel

lants’ claims like those presented in Whippier, share a com

mon disability under Georgia law. As Whippier indicates,

Georgia courts have never held, where a procedural objec

tion was raised, that claims similar to appellants’ will void

a state judgment and thus bring it within the scope of state

habeas corpus. Their claims, like Whippler’s, would be

1 The five claims asserted by Whippier, in his federal habeas

corpus petition, are summarized in the opinion as follows (see 342

F. 2d at pp. 390, 391) : (1) Admission in evidence, over Peti

tioner’s timely objection, of a coerced confession; (2) Admission

in evidence, over Petitioner’s timely objection, o f certain evidence

obtained as the result of an unlawful search and seizure; (3) In

dictment by a grand jury and trial jury [sic] by a traverse jury

from which Negroes had been systematically excluded; (4) Con

finement from July 19, 1960 to December 5, 1960 without benefit

of a commitment hearing; (5) Causing Petitioner to incriminate

himself by taking his fingerprints under the pretense of custodial

purposes and actually using then [sic] to obtain a conviction.

5

equally barred by the Georgia limitation on habeas cor

pus review. In any event, Cobb v. Balkcom, 339 F. 2d 95,

100-01 (5th Cir. 1964) (systematic exclusion of Negroes

from grand and traverse juries) makes it clear that appel

lants cannot be required to speculate upon the possibility

that George habeas corpus may expand, in light of Fay v.

Noia, supra, to include consideration of a federal sub

stantive right not previously embraced.

B. Subsequent to the tiling of appellants’ brief, the

United States Supreme Court decided Hamm, v. Rock Hill,

379 U. S. 306, finding that state trespass convictions not

finalized at the time of the passage of the Civil Bights Act

of 1964, and pending on direct review, were, under the

force of the Supremacy Clause, abated by the passage of

that Act. The effect of the Civil Bights Act of 1964 and its

interpretation in Hamm is to foreclose punishment for any

pre-enactment conviction not finalized at the time that the

federal law intervened. The applicability of the Civil

Bights Act of 1964 to cases pending collateral review is an

issue now pending before this court in Tolg v. Grimes,

5th Cir., No. 21661, and necessarily subsumed in the case

at bar.2

Title 28 U. S. C. §2241(c)(3) provides:

(c) The writ of habeas corpus shall not extend to a

prisoner unless—

(3) He is in custody in violation of the . . . laws

. . . of the United States; . . .

2 Appellants noted (see Appellants’ Brief, p. 10) that as the

judgment below was entered prior to passage of the Civil Rights

Act, that issue was not presented, but it should be further noted

that appellees, in their brief, nowhere contest the obvious impli

cations of passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, upon appel

lants’ convictions.

6

Section 203(c) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U. S. C.

§2000a-2) provides:

No person shall . . . punish or attempt to punish

any person for exercising or attempting to exercise

any right or privilege secured by section 201 or 202.

Section 201(a) provides:

All persons shall be entitled to the full and equal

enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, privileges,

advantages, and accommodations of any place of public

accommodation, as defined in this section, without dis

crimination or segregation on the ground of race, color,

religion, or national origin.

Appellants submit that the effect of Hamm, extending

to all convictions not “ finalized,” is to carve out a category

of inclusion broader than cases pending direct review.

“ Finalized,” a term twice used by the majority is appro

priately more inclusive3 given the Court’s recognition of

the Congressional emphasis upon the cessation of punish

ment expressed in §203(c).

Doubtless, §203(c)’s proscription of punishment collides

with 28 U. S. C. §2241 (c)(3) no less than this expression

of Congressional will operated in Hamm to abate convic

3 It is interesting to note that in a later Supreme Court decision,

Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U. S. 618, where the Court used both the

terms “ final judgment” and “ finalized,” in refusing to apply

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. S. 643, to a case on collateral review, it was

careful to define “ final judgment” :

By final we mean where the judgment of conviction was

rendered, the availability of appeal exhausted, and the time

for petition for certiorari had elapsed . . . 381 U. S. at 622,

footnote 5.

7

tions pending direct review at the time of passage. The

Court, in Hamm, discussing the effect of the Act upon

prosecutions stated (379 U. S. at p. 313):

“Although [United States v.] Chambers [291 U. S.

217] specifically left open the question of the effect

of its rule [of abatement] on cases where final judg

ment was rendered prior to ratification of the Twenty-

First Amendment, and petition for certiorari sought

thereafter, such an extension of the rule was taken for

granted in the per curiam decision in Massey v. United

States, supra, [291 U. S. 608] handed down shortly

after Chambers.

It is apparent that the rule exemplified by Chambers

does not depend on the imputation of a specific inten

tion to Congress in any particular statute. . . . Rather,

the principle takes the more general form of imputing

to Congress an intention to avoid inflicting punish

ment at a time when it can no longer further any legis

lative purpose, and would be unnecessarily vindic

tive.” (Emphasis added.)

While the Court found that the general principle of

abatement “ is to be read wherever applicable as part of

the background against which Congress acts,” it also deter

mined that Congress had exercised its power to abate in

the Act itself. 379 U. S. at 314. Given the sufficiency of

the common law doctrine of abatement to vacate pre-enact

ment convictions, Congress’ specific prohibition on punish

ment with no specific reference to abatement implies an

intent to devitalize all pre-enactment convictions. It would

be anomalous to conclude that such power is abbreviated

by the passage of time for filing certiorari.

8

It is entirely consistent with the language in Hamm and

the general thrust of that opinion to include within the

category of finalized convictions all except those where

punishment has ceased. The Court was precise in depict

ing the Act as a “ far-reaching and comprehensive scheme”

sufficient to annul contrary state practices. 379 U. S. at 314.

It also commented upon the substitution of a right for a

crime as a “ drastic change.” Under such circumstances

where congressional and judicial sentiment are in accord,

continued punishment certainly becomes meaningless and

unnecessarily vindictive.

Section 203(c) of the Act forces this conclusion. The

provision condemns any punishment for the exercise of

rights secured by the Title, not simply arresting, prose

cuting, sentencing, or committing. If Congress intended

to restrict the reach of this provision to a particular form

of punishment, it could have easily done so. That the con

gressional intent was otherwise and that an unqualified

meaning of “punishment” was intended was made clear

by Judge Bell in Dilworth v. Riner, 343 F. 2d 226 (1965)

where he rejected the argument that prosecution was not

punishment if there was the possibility of reversal on ap

peal. He emphasized that “ the right to public accommoda

tions on a non-discriminatory basis is a federal right the

claim to which Congress has said shall not be the subject

matter of punishment,” and that individuals exercising

such federal rights “ may simply not be punished.” 343

F. 2d at 231.

This interpretation of congressional intent is supported

by the legislative history. Senator Stennis of Mississippi

objected to §203(c) as it applied to the law enforcement

processes of the State:

9

This is patently an attempt to make enforcement by

State judges and State law enforcement officers of

State laws which may later be held to conflict with

the act a violation of a federal law and to subject them

to punitive Federal action. (110 Cong. Rec. 6871

(daily ed. April 7, 1964).)

The Court in Hamm could not find “ persuasive reasons”

to impute to Congress an intent to insulate the prosecutions

under review there, noting that the supposed right to dis

criminate on the basis of race had been qualified by the

statute in a congressional effort to “ eradicate an unhappy

chapter in our history.” 379 U. S. at 315. Appellant fur

ther submits that Congress in considering the public ac

commodations title of the bill was thinking not only in terms

of “ rights” to be created by it, but of rights already exist

ing, at the very least on the moral plane, which were to be

secured by it. The House Committee Report on the Civil

Rights Act, H. R. Report No. 914 (88th Cong. 1st Sess.

1963) contains passages corroborating our position.

. . . Today, more than 100 years after their formal

emancipation, Negroes, who make up over 10 percent

of our population, are by virtue of one or another

type of discrimination not accorded the rights, privi

leges, and opportunities which are considered to be,

and must be, the birthright of all citizens.

In the next paragraph, it is added:

. . . A number of provisions of the Constitution of the

United States clearly supply the means to “ secure these

rights,” and H. R. 7152, as amended, resting upon this

authority, is designed as a step toward eradicating

10

significant areas of discrimination on a nationwide

basis. It is general in application and national in

scope.

That this language refers, among other things, to the

public accommodations problem is made clear on the same

page, where it is said of the bill:

. . . It would make it possible to remove the daily

affront and humiliation involved in discriminatory de

nials of access to facilities ostensibly open to the gen

eral public . . .

This application is also suggested by specific statement

in the part of the Report at p. 20 dealing with public

accommodations :

Section 201(a) declares the basic right to equal ac

cess to places of public accommodation, as defined,

without discrimination or segregation on the ground

of race, color, religion, or national origin. [Emphasis

added.]

In the Senate, a textual change, highly significant here,

took place when, in §207(b), the phrase “based on this

title” was substituted for “hereby created,” in application

to the rights to public accommodation. Senator Miller of

Iowa, explaining, said:

One can get into a jurisprudential argument as to

whether the title creates rights. Many believe that the

title does not, but that the rights are created by the

Constitution. [Emphasis added.] (110 Cong. Rec.

12999 (daily ed. June 11, 1964).)

11

These passages make plain that the Act was passed in

an atmosphere in which the right to nondiscrimination was

conceived of, at least in part, as something that existed

before the bill, something that was recognized, declared,

and protected rather than being created by the bill. They

further show that there is nothing unnatural in a construc

tion of §203 (c) that extends to pre-enactment convictions

now on collateral review if the right “ secured” and es

pecially implemented by the law was conceived of as exist

ing, at least morally, prior to its passage. In this setting,

an all-inclusive reading of “punishment” is mandatory. It

is precisely these “ secured” rights which §203 (c) now in

sulates from punishment. To condition the effectuation of

Congress’ intent not to punish the exercise of such rights

on the method by which a conviction is being reviewed is

to defeat the congressional intention.

At least some of the “ rights” “ secured” by Title II of

the Civil Eights Act were necessarily conceived as pre

existing the Act, as a matter of strictest law, for Title

II proscribes discrimination supported by state action

(§§201a, b). Moreover, among the forms of “ state action”

illegal under the Act is state “ enforcement” of “ custom”

(§2001d(2))—terminology seemingly applicable to the case

at bar. In §203 (c), Congress lumps together all these

“ rights” without the slightest suggestion of there being

intended any distinction between them, with respect to

the present lawfulness of “ punishing” their assertion,

whenever that assertion took place. It can hardly be be

lieved that Congress would have wished to present this

Court with the task of unravelling and disentangling those

“ rights” which did and those which in some strict sense

did not antedate the Act, merely for the purpose of dis

12

posing of residual convictions for actions now approved.

It is much, more reasonable to think that Congress meant

to forbid “ punishment” of all actions descriptively similar

to those now shielded by the Act.

CONCLUSION

W herefore, for the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully

submitted that the Order and Judgment of the District

Court along with appellees’ Motion to Dismiss, denying the

petition for writ of habeas corpus and remanding appel

lants to custody, be reversed, vacated, and set aside with

directions to the District Court to conduct a full evidentiary

hearing and with further directions to consider the effect

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 upon future custody of the

appellants, or such other directions as to this Court appear

to be just and conformable to the usages and principles of

law and equity.

Respectfully submitted,

H oward M oore, Jr.

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

J ack Greenberg

James M. N abrit, III

Charles H . J ones

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

S heila R ush

Of Counsel

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on the ....... day of October, 1965,

two copies of the foregoing brief were served upon Hon

orable Arthur Bolton, Attorney General of the State of

Georgia, and Peyton Hawes, Assistant Attorney General,

State Judicial Building, Atlanta, Georgia 30303, by United

States Mail, air mail, postage prepaid.

Attorney for Appellants