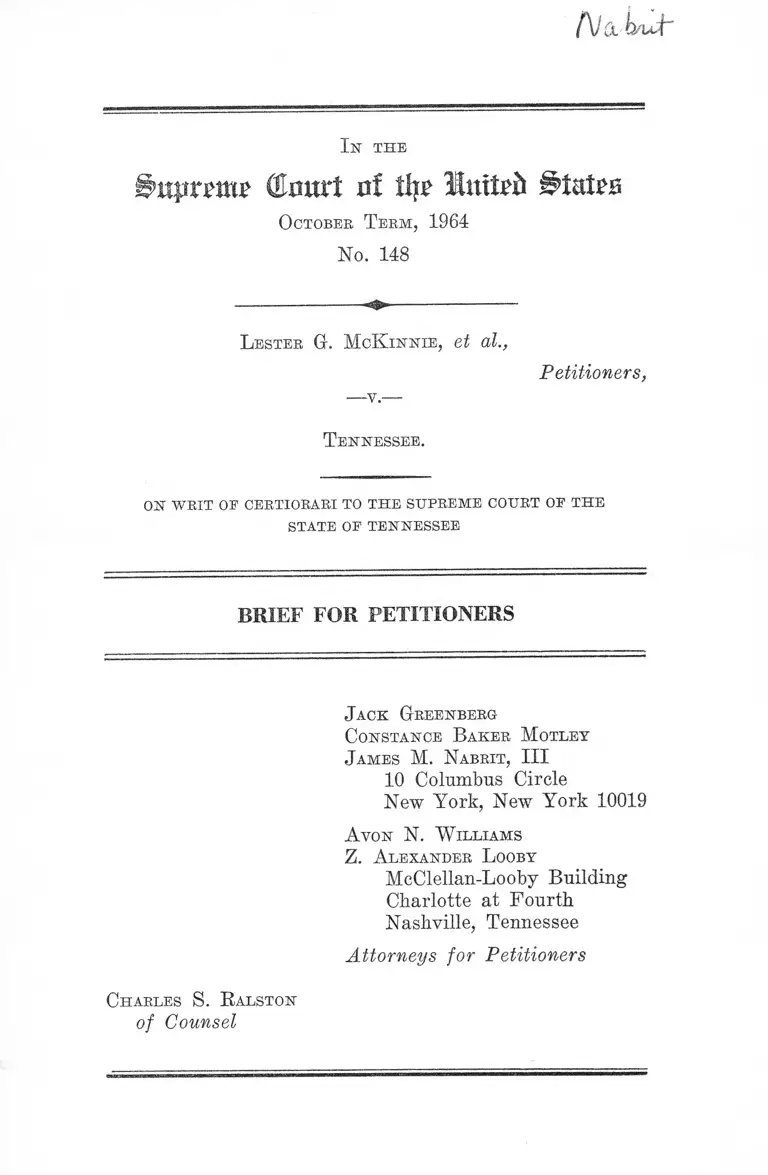

McKinnie v, Tennessee Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McKinnie v, Tennessee Brief for Petitioner, 1964. 389295a8-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8190c614-e4a7-4bbf-a3f7-9f04f51d2f49/mckinnie-v-tennessee-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

A/a

XlsT THE

(Eourt at tl}? Intted S>tata

October T erm, 1964

No. 148

L ester G. McK innie, et al.,

—v.—

Petitioners,

T ennessee.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OP THE

STATE OF TENNESSEE

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Jack Greenberg

Constance Baker M otley

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A von N. W illiams

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

Charles S. R alston

of Counsel

I N D E X

Opinions Below ................................................................. 1

Jurisdiction........... - ........................................................... 1

Questions Presented........... ......... -................................... 2

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved....... 3

Statement of the Case...................................................... 5

Summary of Argument ......... ................. - ...................... 10

Argument....................-..................................................... 13

I. The Enactment of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, Subsequent to These Convictions But

While They Were Still Under Direct Review,

Makes Necessary Either Their Outright Re

versal or a Remand to the State Courts for Con

sideration of That A c t ......................................... 13

A. The Civil Bights Act of 1964 Abates These

Prosecutions As a Matter of Federal Law,

and These Cases Should Be Reversed on

That Ground.................................................... 13

B. The Least Possible Consequence in This

Case, of the Rule Announced in Bell v.

Maryland Is Its Remand to the State Court,

for Consideration There of the Effect of

the Enactment of the Federal Civil Rights

Act of 1964 ...................................................... 15

PAGE

11

II. Petitioners’ Convictions Enforced Racial Dis

crimination in Violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States —.......................................... - ..................... 17

III. Petitioners’ Convictions Deny Due Process of

Law Because They Are Based on No Evidence

of the Essential Elements of the Crime of Un

lawful Conspiracy ................................................ 19

IV. Petitioners Were Denied Due Process in Vio

lation of the Fourteenth Amendment When the

Trial Judge Instructed the Jury That Peti

tioners Were Charged With Violation of a Stat

ute When (a) Petitioners Had Not in Fact

Been Indicted for Violation of the Statute and

PAGE

(b) It Was Not Even a Criminal Statute .... 24

V. Petitioners Were Denied Due Process in That

Their Convictions Were Affirmed on a Ground

Not Litigated in the Trial Court...................27

VI. Petitioners Were Denied a Fair and Impartially

Constituted Jury Contrary to Due Process of

Law and Equal Protection of the Laws Secured

by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution ............. ...........................29

Conclusion........................................................................ 32

A ppendix .......................... ..................... -................................— la

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title I I ............. ..... ......... . la

I l l

T able of Cases

Aldridge v. United States, 283 II. S. 308 12, 31

PAGE

Bell v. Maryland, 378 U. S. 226 ......................... 10,14,15,16

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 ......................... 23

Cline y . State, 204 Tenn. 251, 319 S. W. 2d 227 (1958) 20

Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S. 196 ..................12, 20, 26, 27, 29

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 ................................... 26

Delaney v. State, 164 Tenn. 432, 51 S. W. 2d 485 (1932) 20

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 -........... -..... -11, 21, 22, 23

Glasser v. United States, 315 U. S. 60 ..........-.................. 31

Hamilton v. Alabama, 368 U. S. 52 ................................. 27

Hauenstein v. Lynham, 100 U. S. 483 ............................. 16

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267 ........................... 10,18

Sbelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ............ -....................... 18

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 376 U. S. 339 .... 26

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128........................................ 31

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 .............. 12, 25,27

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 ......... ............-12, 25, 27

Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U. S. 217 .............. 31

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199............................. 23

United States v. Chambers, 291 U. S. 217...................... 14

United States v. Tynen, 78 U. S. (11 Wall.) 88 .............. 14

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 23

IV

F ederal Statutes

Civil Eights Act of 1964, Title II, 78 Stat. 241

1 IT. S. C. §109, 61 Stat. 635 ...............................

.3,10,13,

14,15

...... 3

PAGE

State Statutes

1 Maryland Code §3 (1957) ............................................ 15

Tenn. Code Ann. §1-301 ................................................5,16

Tenn. Code Ann. §39-1101(7) ............................. 4,17,19,24

Tenn. Code Ann. §62-710 .........................4,18, 24, 25, 26, 27

Tenn. Code Ann. §62-711 .....................................5,17,19, 24

Other A uthority

Brief for Petitioners, Hamm v. City of Bock Hill, No.

2 October Term, 1964 .......... ....... .... ........ ............. 14

In t h e

B n p m i u ( t a t r t x d % Itttte it B t n t m

October Term, 1964

No. 148

L ester G. McK innie, et al.,

Petitioners,

T ennessee.

ON WRIT OE CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OE THE

STATE OP TENNESSEE

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Tennessee (R. 315)

is reported at------Tenn.------- , 379 S. W. 2d 214, the opinion

of the Supreme Court of Tennessee on petition for rehear

ing (R. 328) is reported at------Tenn.------- , 379 S. W. 2d 221.

The Criminal Court of Davidson County, Tennessee, Divi

sion Two, delivered no opinion (R. 314).

Jurisdiction

The final judgment of the Supreme Court of Tennessee,

which is the order denying rehearing, was entered on March

5, 1964 (R. 329). The petition for writ of certiorari was

filed June 3, 1964, and granted October 12, 1964 (R. 331).

2

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U. S. Code §1257(3), petitioners having asserted below and

here denial of rights secured by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

Questions Presented

1. Does the federal Civil Eights Act of 1964 compel the

reversal of these convictions, as a matter of federal law!

2. Must these cases be remanded to the state courts for

consideration of the effect of the federal Civil Eights Act

of 1964?

3. Do these convictions result in the enforcement of

racial discrimination against petitioners, with such admix

ture of “ state action” as to bring to bear the equal protec

tion guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment?

4. Is the record so devoid of any evidence of the essen

tial elements of unlawful conspiracy as to render the con

viction for that offense a deprivation of due process of law

under the Fourteenth Amendment?

5. Did the action of the trial judge in instructing the jury

three times that petitioners were charged with violating a

law under which they had not been indicted and which was

not even a criminal statute deprive petitioners of due proc

ess of law under the Fourteenth Amendment?

6. Did the Supreme Court of Tennessee affirm peti

tioners’ conviction on a ground not litigated in the trial

court so as to deny them an appeal which considered the

case as it was tried, in violation of the due process clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment ?

3

7. Did a trial by an all-white jury, some of whose mem

bers admitted personal belief in racial segregation, preclude

petitioners having a fair and impartial jury of their peers

in violation of due process, and did the trial judge's refusal

to dismiss jurors challenged by petitioners for good cause

deny petitioners due process of law under the Fourteenth

Amendment ?

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved

1. This case involves the following provisions of the

Constitution:

Article VI, Clause 2;

The Fourteenth Amendment

2. This case also involves the following statutes of the

United States:

Civil Eights Act of 1964, Title II, 78 Stat. 243-246,

set forth, infra, at p. la ;

1 U. S. C. §109, 61 Stat. 635:

Repeal of statutes as affecting existing liabilities.—

The repeal of any statute shall not have the effect to

release or extinguish any penalty, forfeiture, or lia

bility incurred under such statute, unless the repeal

ing Act shall so expressly provide, and such statute

shall be treated as still remaining in force for the

purpose of sustaining any proper action or prosecution

for the enforcement of such penalty, forfeiture, or

liability. The expiration of a temporary statute shall

not have the effect to release or extinguish any penalty,

forfeiture, or liability incurred under such statute, un

less the temporary statute shall so expressly provide,

and such statute shall be treated as still remaining in

4

force for the purpose of sustaining any proper action

or prosecution for the enforcement of such penalty,

forfeiture, or liability.

3. This case also involves the following sections of the

Code of the State of Tennessee:

39-1101. “ Conspiracy” defined.—The crime of con

spiracy may be committed by any two (2) or more per

sons conspiring: . . . (7) to commit any act injurious

to public health, public morals, trade, or commerce . . .

62-710. Right of owners to exclude persons from

places of public accommodation.—The rule of the com

mon law giving a right of action to any person ex

cluded from any hotel, or public means of transporta

tion, or place of amusement, is abrogated; and no

keeper of any hotel, or public house, or carrier of pas

sengers for hire (except railways, street, interurban,

and commercial) or conductors, drivers, or employees

of such carrier or keeper, shall be bound, or under any

obligation to entertain, carry, or admit any person

whom he shall, for any reason whatever, choose not to

entertain, carry, or admit to his house, hotel, vehicle,

or means of transportation, or place of amusement ;

nor shall any right exist in favor of any such person

so refused admission; the right of such keepers of

hotels and public houses, carriers of passengers, and

keepers of places of amusement and their employees to

control the access and admission or exclusion of per

sons to or from their public houses, means of trans

portation, and places of amusement, to be as complete

as that of any private person over his private house,

vehicle, or private theater, or places of amusement for

his family.

5

62-711. Penalty for riotous conduct.—A right of ac

tion is given to any keeper of any hotel, inn, theater, or

public house, common carrier, or restaurant against

any person guilty of turbulent or riotous^conduct

within or about the same, and any person found guilty

of so doing may be indicted and fined not less than one

hundred dollars ($100), and the offenders shall be li

able to a forfeiture of not more than five hundred dol

lars ($500), and the owner or persons so offended

against may sue in his own name for the same.

1-301—The repeal of a statute does not affect any

right which accrued, any duty imposed, any penalty in

curred, nor any proceeding commenced, under or by

virtue of the statute repealed.

Statement

Petitioners, Lester Gr. McKinnie, Nathal \V inters, John

R. Lewis, Harrison Dean, Frederick Leonard, Allen Cason,

Jr., John Jackson, Jr., and Frederick Hargraves, were ar

rested and convicted of unlawful conspiracy after an at

tempted “ sit-in” demonstration at the Burras and Webber

Cafeteria in Nashville, Tennessee.

Around noon on October 21, 1962, petitioners, young

Negro college students, entered the front door of the Bur-

rus and Webber Cafeteria (R. 96).1 Two swinging doors

on the sidewalk opened on the vestibule (R. 89), six feet by

six feet, four inches (R. 271).2 Another set of swinging

doors led into the dining room (R. 89).

1 The cafeteria had a front entrance and a hack entrance (R.

124).

2 Estimates of the size of the vestibule varied from four feet by

four feet (R. 89) to twelve feet by twelve feet (R. 170), but Otis

Williams, the doorman at the Cafeteria, testified that he measured

it as six feet by six feet, four inches (R. 270-271).

6

Before the petitioners could go through the second doors,

the doorman, Otis Williams held them closed and said,

“Now, we don’t serve colored people in here. I want to be

nice to you, but we don’t serve ’em . . . and you can’t come

in” (R. 271).3 Petitioners remained standing in the vesti

bule for approximately 20 or 25 minutes when they were

arrested (R. 92, 278).4 5 People were walking in front of the

cafeteria, and estimates of the number of people who stood

by or near the outside door of the vestibule varied from

three or four to seventy-five or one hundred (R. 97, 101,

113, 126, 178-179, 202, 234). It was not established how

many, if any, of those standing outside desired to enter the

B. & W. or were just curious observers. No witness testi

fied that they were prevented either from entering or leav

ing the cafeteria (R. 98, 104, 115, 133, 164-166, 179-181, 187,

197-198, 204, 230, 247, 251). The doorman did testify that

some customers on the outside left rather than force their

way through the crowd (R. 278, 281). However, he also ad

mitted that several did enter the cafeteria (R. 281).

Several patrons of B. & W. testified that if the doorman

had not been holding the door so that the petitioners could

not enter, there would have been no congestion (R. 100-101,

165, 228-229).® Although the doorman and other witnesses

3 Williams, a 64 year old man weighing only 140 pounds, held

the door and kept petitioners out while allowing white patrons in

the vestibule to enter the cafeteria, one at a time through a crack

in the door (R. 271, 280, 281). He stated he was hired to keep

Negro patrons out (R. 281-282) and was ordered to lock the doors

if Negroes came (R. 282). When petitioners arrived, Williams

“ caught the door going into the cafeteria, and stopped them there,

and the white people, too . . . ” (R. 269).

4 The doorman testified that petitioners were there forty or forty-

five minutes (R. 272). However, he did indicate that in the excite

ment he was not able to keep accurate track of the time (R. 278).

5 Charles Edwards stated:

“ Q. If the doorman hadn’t blocked the door, they would

have gone in the place, so that ingress and egress would have

7

testified that petitioners were “pushing and shoving” in the

vestibule (E. 168, 169, 214, 278-280),6 their evidence indi

cated that this was occasioned in part by white patrons

coming through the crowded vestibule (E. 175-177, 279-

280). All the witnesses entered the cafeteria, although a

few spoke of having to “ elbow” or “ push” their way through

(R. 116-117, 187). Others entered with little difficulty (E.

109,164).7

One witness testified that as she approached the restau

rant she heard someone say, “When we get there, just keep

pushing. Do not stop. Just keep on pushing,” that she

looked around and saw a group of Negroes who passed her

been free? Wouldn’t it? A. I suppose so, if he had wanted

Negroes in, too.

Q. Yes, sir, the doorman was blocking them so that they

couldn’t get in? A. The doorman was holding the door, and

the Negroes were blocking the vestibule so that people couldn’t

get in there.

Q. . . . The doorman was the one who was blocking the

door and keeping people out? . . . A. He was holding the

Negroes out, and as a result, they had the vestibule blocked,

and the other people could not get by” (R. ,100-101).

6 The evidence of the doorman was the strongest against peti

tioners. He testified that they pushed white persons up against

the wall and doors (R. 271, 280, 289), that they were acting

“brutish” (R. 289), and that one tried to force his way in (R. 289-

290).

7 Mrs. Charles Edwards testified that she “ just went right in”

(R. 109). Mickey Lee Martin testified:

“ Q. You had no trouble getting in? A. No, sir.

Q. Did you have to ask them to let you in ? A. Sir ?

Q. Did you have to ask these colored people to let you in?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And did they let you in? A. Yes, sir, they let me in”

(R. 164).

Patrolman Pyburn testified that after petitioners were standing

four on either side of the vestibule “a person medium size could

get in” (R. 245-246).

on the street and entered the restaurant (R. 210-211, 219-

222).8

W. W. Carrier, Manager of B. & W., testified that in

formed of petitioners’ presence, he went to the front door

(R. 89) and “discovered a large gathering of people . . . on

the outside, and eight young Negroes were in the vestibule,

in between the two doors” (R. 89). Carrier did not speak

to petitioners at that time (R. 91). He called the police and

went outside to wait for them (R. 92). He testified:

Q. As you attempted to pass through the vestibule,

what, if anything, occurred? A. TVell, actually noth

ing, sir. The—the young men were standing in position,

and it was just a matter of my easing through the

crowd (R. 92).

Petitioners informed him that they were seeking service

(R. 94), but Carrier refused because they were Negroes9

(R. 95). At no time did he directly order petitioners to

leave.10 Plis sole comment was to request that they move

back and let a lady get out which petitioners did (R. 93).

He admitted that persons were able to get in and out of the

cafeteria (R. 91).

8 See also testimony at R. 223, 225.

9 On cross-examination Carrier stated:

“ Q. You have the facilities to serve them? A. We do have.

Q. Was your place of business crowded at the time? A. It

was beginning to be crowded, sir.

Q. Now, the only reason that you didn’t serve them was

because they were Negroes and not white, wasn’t it? A. Yes,

sir.

Q. And the same boys, seeking service would have been all

right if they were white ? A. Yes, sir” (R. 95).

10 Carrier testified he did not swear out warrants against peti

tioners and had no idea how his name appeared oil them as prosecu

tor (R. 123).

9

The police arrived shortly after 12:20 and arrested peti

tioners (R. 126, 129). They were charged under a grand

jury presentment11 (R. 1-5) alleging that they:

[0]n the 21st day of October, 1962, and prior to the

finding of this presentment, with force and arms, in

the County aforesaid, unlawfully, willfully, knowingly,

deliberately, and intentionally did unite, combine, con

spire, agree and confederate, between and among them

selves, to violate Code Section 39-1101-(7) and Code

Section 62-711, and unlawfully to commit acts injurious

to the restaurant business, trade and commerce of

Burrus and Webber Cafeteria, Inc., a corporation, lo

cated at 226 Sixth Avenue North, Nashville, Davidson

County, Tennessee (R. 2).

The indictment also alleged that the B. & W. Cafeteria

had a policy of not admitting Negroes, that this policy was

carried on under rights established by Tennessee law, that

there were integrated restaurants in Nashville known to

petitioners, and that petitioners wilfully and deliberately

conspired to conduct “ sit-ins” at various white-only restau

rants in furtherance of the integration movement of which

they were a part (R. 3-4).

Petitioners were tried together in the County Court of

Davidson County, Tennessee. After conviction of unlawful

conspiracy (R. 15) they were sentenced to ninety days in

jail and fifty dollars fine 12 (R. 16). Appeals were taken to

11 Petitioners were arrested without warrants by Nashville police

officers and originally charged with violating City Code Chapter 26,

Section 59 (state law regarding sit-ins) (ft. 160). Later in the

same day, warrants were issued charging them with unlawful con

spiracy. The grand jury presentment was made on December 12,

1962 (R. 1).

12 The jury suggested a fine of less than fifty dollars (R. 313)

but the judge later imposed the severer sentence.

1 0

the Supreme Court of Tennessee which affirmed the convic

tions (R. 326) and denied a petition to rehear (R. 329).

Summary o f Argument

I.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title II (Public Accommo

dations), compels the reversal of these cases and their re

mand for dismissal, both under the doctrine expounded in

Bell v. Maryland, 378 U. S. 226, and by virtue of §203(c) of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, forbidding “punishment” of

acts such as those here shown to have been committed. The

federal and common-law doctrine of abatement of criminal

prosecutions, on removal of the taint of criminality, here

applies.

Moreover, it is clear, under the holding in Bell v. Mary

land, supra, that this case must at least be remanded to the

state court for consideration of the abating effect of the

Civil Rights Act under state law, since that Act is part of

the law of every state.

II.

This case involves the use of state powTer to effect racial

discrimination, contrary to the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment.

In Tennessee at the time of the prosecutions discrimina

tion was expressly permitted under statute. Petitioners,

after attempting to seek service in a white-only cafeteria,

were prosecuted under a presentment that characterized

their integration movement as an unlawful conspiracy.

Thus, the State adopted the posture of supporting and en

forcing segregationist policies, and, under the rule of Lom

bard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267, denied petitioners the

11

equal protection of the laws in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

III.

These convictions deny due process of law in that the

record is devoid of evidence of the essential elements of the

crime charged, unlawful conspiracy.

Under Tennessee law, it is necessary to prove both an

agreement and an overt act in order to convict for con

spiracy. All the evidence in this case shows, however, is

that petitioners went to a cafeteria to attempt to obtain

service, were barred from entrance after they had gone into

a small vestibule, and that the resulting congestion made it

inconvenient for other patrons to enter.

The lack of evidence that they agreed or intended to ob

struct the doorway or to disrupt the cafeteria’s business in

any way requires that the convictions be reversed, under

the rule in Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157.

IV.

Petitioners were denied due process in that the trial

judge instructed the jury that they were charged with

violating a statute when no such charge was in the indict

ment, and the statute was civil, not criminal.

The Supreme Court of Tennessee admitted that the trial

judge erred in instructing the jury that petitioners were

charged with conspiracy to violate a statute that merely

removed the old common law duty of innkeepers and others

to serve all patrons. The court, however, dismissed the

error as insubstantial because there was ample evidence

for a conviction on the other charges.

However, this court has held that where a jury renders a

general verdict, as was done here, and the instructions were

1 2

erroneous, particularly as to the statutes under which the

defendants were charged, the convictions must be reversed

since it is impossible to tell the effect the error had on the

jury’s determination. Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1;

Stromberg v. California, 2S3 U. S. 359.

V.

Petitioners were denied due process by the Supreme

Court of Tennessee affirming their convictions on a theory

other than that under which the cases were presented to the

jury.

The presentment and the judge’s instructions made the

right of the cafeteria to discriminate a central issue in this

case, so that an aura of illegality was cast over petitioners’

attempt to gain equal service. The Tennessee Supreme

Court, however, based its decision on the assumption that

the question of a right to segregate was not present. This

action violated the rule established in Cole v. Arkansas, 333

U. S. 196, that a defendant is entitled to have his case de

cided by a state appellate court on the same basis on which

it was presented at trial.

VI.

Petitioners were denied a fair and impartial jury con

trary to due process of law and equal protection of the laws

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment.

The presentment made the right to operate a segregated

establishment a central issue in the case. However, the trial

judge refused petitioners the right to challenge for cause

veniremen who stated that they believed in the right to

discriminate. Therefore, the jurymen began prejudiced

against the petitioners, in violation of the rule stated in

Aldridge v. United States, 283 U. S. 308.

13

A R G U M E N T

I.

The Enactment o f the Civil Rights Act o f 1964, Sub

sequent to These Convictions Rut While They Were Still

Under Direct Review, Makes Necessary Either Their

Outright Reversal or a Remand to the State Courts for

Consideration o f That Act.

A. The Civil Rights Act o f 1964 Abates These Prosecutions

as a Matter o f Federal Law, and These Cases Should Be

R eversed on That Ground.

The federal Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 241, went

into effect on July 2, 1964. The B. & W. Cafeteria comes

within the terms of Title II, providing for equal enjoyment

of public accommodation, since, being open to the general

public (R. 94) it served or offered to serve interstate trav

elers.13 Therefore, the petitioners would have had federal

statutory protection in seeking service if they had acted

after passage of the act.

13 Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title II, Section 201 . . .

(b) Bach of the following establishments which serves the public

is a place of public accommodation within the meaning of

this title if its operations affect commerce, or if discrimina

tion or segregation by it is supported by State action: . . .

(2) Any restaurant, cafeteria, lunchroom, lunch counter,

soda fountain, or other facility principally engaged in sell

ing food for consumption on the premises,. . .

* * * # * •

(c) The operations of an establishment affect commerce within

the meaning of this title if (1) it is one of the establish

ments described in paragraph (1) of subsection (b) ; (2) in

the case of an establishment described in paragraph (2) of

subsection (b), it serves or offers to serve interstate travelers

or a substantial portion of the food which it serves . . . has

moved in commerce; . . . [Emphasis added].

14

Moreover, Section 203(c) of the Act provides, “No person

shall . . . (c) pnnish or attempt to punish any person for

exercising or attempting to exercise any right or privilege

secured by section 201 or 202.” Assuming, for the moment

only, that petitioners were prosecuted for attempting to ex

ercise 201 rights, this section clearly would bar the com

mencement of any prosecution if the incident here had taken

place after July 2, 1964. It would also bar prosecutions or

existing punishments begun before that date, since the sec

tion bars punishment of rights “ secured” by the Act. In

other words, the Act does not only create new rights, but

also protects rights already in existence.

In addition to the wording of section 203(c), these prose

cutions also should cease under the Federal rule that a

change in the law, prospectively rendering that conduct in

nocent which was formerly criminal, abates prosecution on

charges of having violated the no longer existent law. See

Bell v. Maryland, 378 U. S. 226, 231, n. 2; United States v.

Chambers, 291 U. S. 217; United States v. Tynen, 78 U. S.

(11 Wall.) 88. And under the supremacy clause of the

Constitution (Article VI, clause 2), a federal statute has

the same abative effect on a state criminal proceeding.14

Turning to the application of these principles to the case

at hand, it is clear that the character of the presentment is

of central importance. If the petitioners had simply been

prosecuted for disorderly conduct, it would have been diffi

cult to say that they were being punished for “attempting

to exercise” rights secured by section 201. However, in the

presentment the state charged that petitioners knew that

the B. & W. Cafeteria had a policy of racial segregation

(R. 3), and that they “unlawfully, willfully, . . . and in

14 These are the same arguments made in more detail for peti

tioners in Hamm v. City of Bock Hill, No. 2, October Term, 1964,

Brief for petitioners, pp. 18-41.

15

tentionally” united and conspired to conduct “ sit-ins” in

order to try to compel the owners to serve them on a non-

segregated basis (E. 3-4).

Thus, in the guise of a prosecution for conspiring to ob

struct commerce and commit disorderly acts, the state has

set out to punish petitioners for attempting to gain rights

protected by the 1964 Act.

For these reasons, these prosecutions must be abated as

a matter of federal law.

B. The Least Possible C onsequence in This Case, o f the Rule

A nnounced in Bell v. Maryland Is Its Rem and to the State

Court, fo r Consideration There o f the E ffect o f the Enact

m ent o f the Federal Civil Rights Act o f 1964 .

In Bell v. Maryland, 378 U. S. 226, decided at the last

term of this Court, it was held that the enactment of a state

public accommodations law, subsequent to the commission of

the alleged offenses but wliile the convictions were still

under review, made appropriate a remand to the state

courts, for consideration of the question whether, within

the framework of the state common and statutory law, such

intervening enactment destroyed the legal basis for prose

cution and made dismissal appropriate. This action was

taken by this Court after careful consideration both of the

general common law rule and of the Maryland general “ sav

ing clause,” 1 Md. Code §3 (1957), see Bell v. Maryland,

supra, 378 U. S. at pp. 230-234, 236, 237.

The federal Civil Eights Act besides being a permanent

federal law, is a part of the law of each state.

It must always he borne in mind that the Constitu

tion, laws and treaties of the United States are as much

a part of the law of every state as its own local laws and

Constitution. This is a fundamental principle in our

system of complex national polity. See also Shanks v.

16

Dupont, 3 Pet., 242; Poster v. Neilson, 2 Pet., 253;

Cherokee Tobacco, 11 Wall., 616; Mr. Pinkney’s Speech,

3 Elliot’s Const. Deb. 231; People v. Gierke, 5 Cal., 381.

(.Hau&nstem v. Lyriham, 100 II. S. 483, 490.)

For the narrower application of the Bell holding the

position, therefore, must be taken to be the same as it would

be if Tennessee had, while these prosecutions were pend

ing, enacted laws exactly equivalent, in tenor and effect, to

the federal Civil Eights Act.

Tennessee has a general “ saving clause” statute, Tenn.

Code Ann. $1-301:

The repeal of a statute does not affect any right

which accrued, any duty imposed, any penalty incurred,

nor any proceeding commenced, under or by virtue of

the statute repealed.

The application of this statute to the saving of these

prosecutions is even more dubious than that of the Mary

land statute, Bell v. Maryland, supra, for the Tennessee

statute speaks only of “repeal,” where the Maryland statute

speaks of “amendment” as well, see Bell v. Maryland, supra,

278 U. S. 226 at pp. 234-5, and the operation of a public

accommodations statute, forbidding racial discrimination,

upon a general trespass law, more nearly resembles “ amend

ment” than “ repeal,” though (as the Court points out in

Bell) neither word may be apt.

As to this case, therefore (even on the assumption, which

is contrary to fact, see Point I-A supra, that the abating

effect of the Civil Rights Act is to be taken to be solely a

state-law question), the least effect of Bell must be reversal

and remand for consideration of the question whether the

Civil Eights Act, in its section quoted above, has the effect

of abating these prosecutions.

17

II.

Petitioners’ Convictions Enforced Racial Discrimina

tion in Violation o f the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution o f the United States.

If it could be assumed (as apparently it was by the

Supreme Court of Tennessee) that this case involved simply

prosecutions for conspiracy to commit an act injurious to

commerce under §39-1101 and conspiracy to commit turbu

lent or riotous conduct under §62-711, then the main ques

tion would be the sufficiency of the evidence supporting

those charges (See Part III, infra). However, by the way

it framed the presentment, the State has put itself in the

posture of directly enforcing racial discrimination.

The presentment recited at some length that the owners

of the B. & W. Cafeteria had a rule that they would serve

only white customers, and that this policy was allowed

under the provisions of the Tennessee Code (R. 2-3). It

charged that petitioners knew of this practice, and deliber

ately embarked on a program of “ sit-ins” for the purpose

of forcing owners to integrate their restaurants (R. 3, 4).

The participation in this integration movement was char

acterized as an “unlawful conspiracy,” and the disturbance

involved in this case was termed “ an overt act” {Ibid.).

Thus, the emphasis of a case that could have been pre

sented simply as one of a group of persons obstructing a

doorway, was shifted radically to one of enforcement of

racial discrimination. The jury must have believed that the

case involved the maintenance of a segregated establish

ment, and they must have regarded themselves as the en

forcers of the B. & W.’s policies. Moreover, the judge’s

charge could only have reinforced this belief; he read the

presentment and the text of the statute giving the B. & \V.

the right to discriminate, and told the jury that petitioners

18

were charged with conspiracy to violate that statute (i.e.,

to violate the owner’s right to run a segregated cafeteria).

Since the State, through its agents, the prosecutor, grand

jury, and judge, decided to frame the ease as to involve

itself in the enforcement of the segregationist policies of

the B. & W., it cannot now claim that all that was involved

was a simple prosecution for conspiracy to commit dis

orderly conduct. This case, therefore, is analogous to

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267, where there was also

no ordinance or state law specifically requiring segregation.

Sufficient state involvement was found in pronouncements

by city officials that “ sit-ins” would not be allowed, followed

by prosecutions for trespass. Here, there was a statute

clearly designed to allow segregation, since it abrogated

the long established common law rule that prohibited dis

crimination in certain businesses. And although there was

no action before the arrests, as there was in Lombard, the

prosecutor and grand jury did act as enforcers of private

discrimination by making the maintenance of segregated

facilities a main issue in the case. In so doing, the state

denied petitioners the equal protection of the laws in vio

lation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In addition, the convictions here must fall under the rule

of Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1. Tennessee has a statute,

§62-710, which is specifically designed to permit racial dis

crimination. The State, moreover, has used its prosecutor

and its courts to actively enforce the permitted custom of

segregation. As Shelley made clear, such employment of

any branch of the state is a violation of the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The action of peti

tioners was like that of other “ sit-in” demonstrators, and

the state may not evade the duty imposed by Shelley simply

by characterizing the prosecution as one for conspiracy to

commit a disorderly act or to interfere with commerce.

19

III.

Petitioners’ Convictions Deny Due Process o f Law Be

cause They Are Based on No Evidence o f the Essential

Elements o f the Crime o f Unlawful Conspiracy.

The presentment under which petitioners were charged

alleged that they:

. . . with force and arms, unlawfully, willfully, know

ingly, deliberately, and intentionally, did unite, com

bine, conspire, agree and confederate between and

among themselves, to violate Code Section 39-1101(7)

and Code Section 62-711, and unlawfully to commit

acts injurious to the restaurant business, trade or com

merce of Burrus and Webber . . . (R. 2).

In its opinion the Supreme Court of Tennessee stated:

Section 39-1101, T. C. A., makes it a misdemeanor

for two or more persons to conspire to do an unlawful

act. In order for the offense to be indictable, it must

be committed manu forti—in a manner which amounts

to a breach of the peace or in a manner which would

necessarily lead to a breach of the peace (R. 318).

The court further stated that:

. . . [Conspiracy may be inferred from the nature

of the acts done, the relation of the parties, the interest

of the alleged conspirators, and other circumstances;

and that such a conspiracy consists of a combination

between two or more persons for the purpose of ac

complishing a criminal or unlawful act, or an object,

which although not criminal or unlawful in itself, is

pursued by unlawful means, or the combination of two

or more persons to do something unlawful, either as a

means or as an ultimate end (R. 319).

2 0

Under Tennessee law, as under that of most jurisdic

tions, the elements of a conspiracy are an agreement be

tween two or more persons to commit an unlawful act, and

the commission of some overt act in furtherance of the

plan.15 In this case there would be two possible unlawful

acts that the petitioners agreed to do: first, to seek service

at a white-only cafeteria; and second, to obstruct passage

into the cafeteria by jamming the vestibule.

Since the Supreme Court of Tennessee acknowledged that

an agreement to try to integrate a cafeteria could not be

an unlawful conspiracy (R. 322), the State had to produce

evidence of an agreement to try to force service by illegal

means, viz., the deliberate obstruction of the entrance way.16

This burden, however, was not met. The only direct evi

dence of a conspiracy was the testimony of two witnesses

that they heard one of the petitioners say, as the group

approached the B. & W., that when they got there or when

they started in, they should keep going, keep pushing, and

not stop (R. 210-211, 219-222, 223, 225).

Even assuming that the other members of the group

agreed to this course of action, the statement is still no

evidence of a conspiracy to obstruct or interfere with the

cafeteria entrance. The statement can only mean that

petitioners had decided to enter the cafeteria even though

some attempt might be made, whether by the management

15 For construction of the Tennessee conspiracy statute see:

Delaney v. State, 164 Tenn. 432, 51 S. W. 2d 485 (1932) (Persons

must unite and agree to pursue an unlawful enterprise) ; Cline v.

State, 204 Tenn. 251, 319 S. W. 2d 227 (1958) (gist of conspiracy

is agreement to effect unlawful end, but, before offense is complete,

party to conspiracy must commit some “overt act” ) .

16 The mere showing that a disorder took place, or even that peti

tioners might have been guilty of disorderly conduct would not be

enough, since conspiracy was charged. Cole v. Arkansas, 333 IT. S.

196.

2 1

or white customers, to deter them. In other words, the

statements show a resolution to seek service and use the

cafeteria facilities, and give no support to any intention to

obstruct their use by any other customers.

Under Tennessee law conspiracy may also be inferred by

circumstantial evidence; however, for such an inference to

be drawn, the standard of sufficiency of evidence applicable

in Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, must be met. The

testimony at trial here does not support the conclusion that

petitioners had agreed to obstruct the entrance or do any

other disorderly act.

In the first place, the doorway was not in fact blocked to

the extent that no one could enter; witnesses testified either

that they were able to make their own way through the

crowd (R. 91, 92, 109, 245-246, 251), or that petitioners

stepped aside when asked (R. 93,164). Indeed, the evidence

is clear that what actually caused obstruction and crowding

in the vestibule was the fact that the doorman would not

let the petitioners in; the testimony of a number of wit

nesses showed that if he had opened the door there would

have been no difficulty (R. 100-101, 165, 228-229, 281).

Morover, no witness testified that petitioners committed

any disorderly act or acts which constituted a breach of

the peace, or that violence occurred or was even threatened.

They used no bad language (R. 226) and did not force

themselves past the doorman who held the door, something

they could easily have done, considering his size and weight

(R. 276). Petitioners were not “ugly” or “disrespectful”

but were, as one witness testified, “ just there” (R. 108-109).

Although they were told “we don’t serve colored people in

here” and “you can’t come in,” no one asked them to leave

the vestibule, where they remained until they were ar

rested.

2 2

Two witnesses testified that petitioners were “pushing”

and “ shoving” (R. 168, 214). However, it was not estab

lished whether this pushing and shoving resulted from the

natural congestion in the vestibule caused by the doorman’s

blocking the door or by petitioners’ actions alone. More

over, a few white patrons stated that they “pushed” inside

the vestibule. One man testified that he “kind a pushed”

his way in (R. 136) and another testified that he “push[ed]

my way through with my boy . . . I did a little pushing”

(R. 187).

Not only, therefore, was there no evidence that petitioners

conspired to commit an unlawful act, the record solidly

refutes the Supreme Court of Tennessee’s conclusion that

the means employed were unlawful.

This case is not materially different from the ordinary

“ sit-in” cases, where Negroes have been convicted for tres

pass after remaining at lunch counters when requested to

leave by restaurant owners, solely because of race. No

constitutional difference exists between sitting quietly on

a lunch stool and standing quietly in a vestibule to protest

racial discriminaton. This court has found no problem in

reversing “ sit-in” convictions based on no more evidence

than the Negroes’ “mere presence” at white restaurants.

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157. Here as in Garner, the

petitioners were not ordered to leave by the restaurateur

or his employees.

It has been recognized that a Negro sitting at a lunch

counter in a southern state to protest racial segregation is

engaged in a type of expression protected by the Four

teenth Amendment. Garner v. Louisiana, supra (Mr. Jus

tice Harlan, concurring). If, therefore, petitioners’ con

duct is construed to constitute an unlawful conspiracy,

then the statute under which they were charged and con

victed is unconstitutionally vague in that it failed to warn

23

petitioners that it was unlawful to quietly remain in a

cafeteria vestibule and because, if so construed, it limits

petitioners’ right of free expression. Garner v. Louisiana,

supra; Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296; Winters v.

New York, 333 IT. S. 507, 509.

In summation then, the evidence shows only that: peti

tioners agreed to go to the B. & W. Cafeteria to attempt to

secure non-segregated service there; when they arrived

their entrance was blocked by the doorman (there was no

evidence that they should have expected this to happen);

during the time they were trying to get in the resulting

congestion made it inconvenient for white patrons to enter

or leave, although none was prevented from doing so; this

situation existed for only a brief time, 20 or 25 minutes,

until the police arrived; petitioners co-operated fully with

the officers, both in standing on both sides of the vestibule

and in leaving. The record is totally devoid of any evidence

indicating that they either had agreed to obstruct the door

way beforehand or even that they wanted or tried to after

they arrived.

Because there is no evidence to support the charges of

unlawful conspiracy, the convictions deny petitioners due

process of law. Thompson v. Louisville, 362 TJ. S. 199;

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157.

24

IV.

Petitioners Were Denied Due Process in Violation o f

the Fourteenth Amendment When the Trial Judge In

structed the Jury That Petitioners Were Charged With

Violation o f a Statute When (a ) Petitioners Had Not

in Fact Been Indicted for Violation o f the Statute and

(b ) It Was Not Even a Criminal Statute.

Petitioners were indicted for unlawfully conspiring to

violate Sections 39-1101(7) (act injurious to commerce) and

62-711 (riotous conduct) of the Code of Tennessee. After

reading the presentment to the jury, the judge read them

the texts of not only the two above sections hut also that

of Section 62-710 (R. 298). This section abrogates the rule

of the common law imposing a duty on innkeepers, etc., to

serve all persons, and allows them to exclude anyone for

any reason. He then, on three occasions, told the jury that

petitioners were charged with conspiracy to violate not only

Sections 39-1101(7) and 62-711, bnt also Section 62-710.17

17 The trial judge told the jury (R. 299) :

You will note from the language of the presentment that

the defendants are charged with the offense of unlawful con

spiracy to violate Code Section 39-1101(7), Code Sections

62-710 and 62-711, in that they did unlawfully commit acts

injurious to the restaurant business, trade and commerce of

Burrus & Webber Cafeteria, Inc., a corporation, located at

226 6th Avenue North, Nashville, Davidson County, Tennessee.

And also at (R. 302-303) he said:

. . . I f you find and believe beyond a reasonable doubt that

the said defendants unlawfully, wilfully, knowingly, deliber

ately, and intentionally did unite, combine, conspire, agree

and confederate between and among themselves, to violate

Tennessee Code Section 39-1101-(7) and Code Sections 62-710

and 62-711, and unlawfully to commit acts injurious to the

restaurant business, trade and commerce of Burrus and

Webber Cafeteria, Inc., a corporation, located at 226 6th

Avenue North, Nashville, Davidson County, Tennessee, as

Petitioners’ motion for a new trial, urging this as a denial

of due process, was overruled (E. 18-19, 27).

It is clear that §62-710 itself could not form the basis for

a criminal charge of any sort. It merely changes a rule of

the common law and is not a penal statute. Moreover, the

state could not punish someone for conspiring to violate

the section, since the section imposes no duties. It merely

says that innkeepers may refuse to serve, if they choose; it

says nothing about other persons seeking service, even

from a reluctant owner. Indeed, the Supreme Court of

Tennessee acknowledged that the statute was civil and the

judge’s charge was error (R. 321).

The instruction to the jury that they could convict peti

tioners on a charge not capable of being made, clearly vio

lated petitioners’ right to due process of law. In Stromberg

v. California, 283 U. S. 359, a conviction based on a general

verdict under a state statute was set aside because one part

of a statute submitted to the jury was unconstitutional. In

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1, the court in instructing

the jury about a city ordinance did so on a theory which

permitted conviction on an unconstitutional basis.

In addition, even if §62-710 might form the basis of a

criminal charge, it could not be used in this case since the

presentment was not brought under it.18 It is clear that a

charged in the presentment, then it would be your duty to

convict the defendants; provided, that they, or one of them,

did, in pursuance of said agreement, or conspiracy, do some

overt- act to effect the object of the agreement; that is, if you

find that said agreements and acts in the furtherance of said

objective were done in Davidson County, Tennessee.

See also, R. 305.

18 The presentment mentions §62-710 but the petitioners were

specifically charged under §§39-1101(7) and 62-711 (R. 2). As

will be discussed infra, however, the presentment does add to the

confusion resulting from the judge’s charges.

26

defendant may not be convicted for one offense after hav

ing been indicted for another. DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. 8.

353. Cf., Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S. 196; Shuttlesworth v.

City of Birmingham, 376 U. S. 339.

The Supreme Court of Tennessee rejected these argu

ments, saying that the charge, even though error, could not

have been harmful since there was ample evidence to con

vict the defendants of the offenses defined in the other code

sections (E. 321). However, this conclusion overlooked the

nature of the case and the presentment involved. The

jury’s verdict was a general one, viz., “ guilty of unlawful

conspiracy” (E. 15). It is impossible from this to ascer

tain what the jury believed petitioners were guilty of con

spiring to do. The presentment itself referred to §62-710

and described at some length the practices of the B. & W.

Cafeteria in excluding Negroes; it also stated that the

owners of the B. & W. had the right to discriminate under

Tennessee law (E. 3). The presentment recited that the

petitioners were engaged in “a movement to coerce, compel,

and to intimidate owners of restaurants . . . and cafeterias

serving only white persons to ‘integrate’ ” against the

policy established by virtue of §62-710 (E. 3, 4).

Thus, from the presentment alone the jury could have

been confused and under the impression that petitioners, by

the mere act of attempting to integrate against the wishes

of the B. & W., were committing an unlawful act. Such an

impression could only have been affirmed by the judge’s in

struction, which specifically stated that petitioners were

charged with conspiring to violate the section giving the

B. & W. the right to discriminate. Since the jury’s verdict

does not indicate what in fact was the basis for its decision,

the possible prejudicial effect of the judge’s charge cannot

be ignored. Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359; Termi-

27

niello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 4. C l, Hamilton v. Alabama,

368 U. S. 52; G'ofe v. Arkansas, 333 IT. S. 196.

The State Supreme Court’s statement that “ there were

no questions raised following the charge about the pro

priety of reading it [§62-710]” misses the mark on several

counts. First, the petitioners sought and were refused an

instruction, contrary to the one given, to the effect that

notwithstanding §62-710, the restaurant had no right to

exclude them (R. 310). Secondly, they did object, by motion

for new trial, to the reading of this statute (R. 18-19).

Thirdly, they also objected, on due process grounds, to the

trial judge’s misstatement of the offense charged in the

motion for new trial (E. 19). Finally the stated ground of

decision below was “harmless error” and not any theory

that the objection was not timely. In any event there were

no objections made to the instructions given in Stromberg

supra, and Terminiello, supra.

v .

Petitioners Were Denied Due Process in That Their

Convictions Were Affirmed on a Ground Not Litigated

in the Trial Court.

The petitioners wTere tried and convicted under a grand

jury presentment which was drawn on the theory that the

B. & W. Cafeteria was legally entitled under Tennessee law

(§62-710) to exclude petitioners because of their race

(R. 2-3). The trial judge read the presentment and also

§62-710 to the jury (R. 292-295; 298), and refused a re

quested instruction that the cafeteria had no legal right to

exclude persons because of race (R. 310). Moreover, be

cause the judge instructed the jury that petitioners were

charged with conspiracy to violate §62-710 (i.e., to violate

the cafeteria’s right to discriminate), the jury must have

considered that a right to segregate was a central issue.

However, the Tennessee Supreme Court decided the case

on the assumption “ for the sake of argument that discrimi

nation based on race by a facility such as this cafeteria

does violate the due process and equal protection clauses”

(R. 318-319). The court asserted that the only question,

given this assumption, was whether the method that peti

tioners adopted was illegal (R. 319). The Supreme Court

of Tennessee disposed of the claimed trial error in refusing

an instruction that the cafeteria had no legal right to re

fuse service on the basis of race by saying (R. 322):

As we have heretofore said, this question is not the

issue in this case, and was not the basis of the indict

ment and conviction. Even if we assume that the owner

of the cafeteria had no right to exclude these defen

dants, this does not excuse their conduct in blocking

this narrow passageway.

However, the case was submitted to the jury on the

theory that the petitioners had lawfully been excluded from

the B. & W. Cafeteria because of their race. Thus, the

affirmance of the conviction was on a theory that did not

take into account the issue that was inextricably bound into

the presentment and the charge to the jury.

It is obvious that the jury might have found the peti

tioners not guilty if it had been instructed that the B. & W.

Cafeteria had no legal right to exclude petitioners because

of race, and that it violated their rights when it did so.

Moreover, the jury was not instructed to consider the issue

which the State Supreme Court did decide, i.e., assuming

petitioners had a right to enter the cafeteria, was their

method of seeking to vindicate that right unlawful.

Since the basis for affirming the convictions was not the

same as that under which the convictions wrere rendered,

29

the decision of the Tennessee Supreme Court must be re

versed under the holding of Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S. 196,

202:

To conform to due process of law, petitioners were

entitled to have the validity of their convictions ap

praised on consideration of the case as it was tried and

as the issues were determined in the trial court.

VI.

Petitioners Were Denied a Fair and Impartially Con

stituted Jury Contrary to Due Process of Law and. Equal

Protection of the Laws Secured by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Almost without exception, the white veniremen, includ

ing some of the twelve persons who tried and convicted

(petitioners, upon extensive examination by petitioners’

counsel during voir dire, admitted a firm and life-long prac

tice, custom, philosophy and belief in racial segregation

(R. 32-39, 44-46). Most of the veniremen expressed belief

that a restaurant owner had a right to exclude anybody, in

cluding Negroes, from his place of business.

Despite this fact, the trial judge in a number of instances

overruled petitioners’ challenges for good cause and held

certain white jurors competent (R. 38, 46, 68, 80, 85-86).

For instance, Herbert Amic was held competent by the

trial court over petitioners’ challenge after testifying:

Q. But you think that a business open to the public-

should be allowed to exclude Negroes? A. If they so

desire, yes.

Q. A restaurant business, then specifically,—in par

ticular? And having that opinion wherein the indict

ment in this case charges that the B. & W. Cafeteria

30

had had such a rale, and that these defendants went

there and sought service, knowing that the B. & W. had

such a rule and then you would start out with a prej

udiced attitude toward these defendants? A. Well,

I would—

Q. By reason of your belief? A. I would believe the

B. & W. would be right in this case on their position.

Q. And you would start—what I am saying, though,

is you would start out in this case with a prejudiced

attitude toward the defendants, wouldn’t you? A. In

this particular case, I imagine I would (R. 56-57).19

Similarly, the trial court held competent other jurors,

over petitioners’ objections for cause, who testified that

their entire lives and all their personal associations had

been on a segregated basis without any contact with Ne

groes on a basis of equality (R. 78-80, 84-85).

In the case at bar, where the very issue to be tried was

the right of a restaurateur to exclude persons on the basis

of race, the trial judge’s failure to exclude these jurors with

admittedly preconceived notions against Negroes and in

favor of B. & W.’s practice of racial segregation, was highly

prejudicial and denied petitioners’ right to trial by a fair

and impartial jury.

This Court has repeatedly recognized that “ the American

tradition of trial by jury, considered in connection with

either criminal or civil proceedings, necessarily contem

plates an impartial jury drawn from a cross-section of the

19 Mr. Amic did testify later that he was not prejudiced against

Negroes as such (R. 61), and that he could render a fair and im

partial verdict (R. 61-62). However, the real question is not

whether he was prejudiced against Negroes, but whether his opinion

on an element in the case made crucial by the way the presentment

was framed would make a fully impartial judgment unlikely.

31

community.” Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U. S. 217,

220; Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128, 130; Glasser v. United

States, 315 U. S. 60, 85. This Court has also recognized

that racial prejudice is a valid ground for disqualification

of a juror; in Aldridge v. United States, 283 U. S. 308,

it was said:

. . . [T]he question is not as to the civil privileges of

the Negro, or as to the dominant sentiment of the com

munity and the general absence of any disqualifying

prejudice, but as to the bias of the particular jurors

who are to try the accused. If in fact, sharing the gen

eral sentiment . . . one of them was shown to entertain

a prejudice which would preclude his rendering a fair

verdict, a gross injustice would be perpetrated in al

lowing him to sit (283 U. S. at 314).

It is clear that the jurors described above and declared

competent by the trial court were incapable, by virtue of

their segregationist beliefs, to render petitioners a fair and

impartial verdict and that their presence as jurors preju

diced petitioners’ right to an unbiased trial. Such action

denied due process as well as equal protection of the laws.

The test established in Aldridge, supra, is more than met

here.

32

CONCLUSION

W herefore, for the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully

submitted that the judgment below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

Constance B aker Motley

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A von N. W illiams

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

Charles S. R alston

of Counsel

APPENDIX

Civil Rights Act of 1964

Title II

Pub. Law 88-352 78 STAT. 243.July 2. 1964

T I T L E I I — I N J U N C T I V E R E L I E F A G A I N S T D I S C R I M I N A

T I O N I N P L A C E S O F P U B L I C A C C O M M O D A T IO N

S e c . 2 0 1 . (a ) A l l persons shall be entitled to the fu ll and equal

en joym en t o f the g ood s, services, facilities , p riv ileges, advantages,

and accom m odations o f any p lace o f p u b lic accom m odation , as d e

fined in th is section, without, d iscrim ination o r segregation on the

g rou n d o f race, co lor, re lig ion , o r national orig in .

(b ) E a ch o f the fo llo w in g establishm ents w hich serves the pu b lic

is a p lace o f p u b lic accom m odation w ith in the m eaning o f th is title

i f its operations affect com m erce, o r i f d iscrim ination o r segregation

by it is su pported by State action :

(1 ) any inn , hotel, m otel, o r other establishm ent w hich p r o

v ides lo d g in g to transient guests,- other than an establishm ent

located w ith in a b u ild in g w hich contains not m ore than five

room s fo r rent o r h ire and w hich is actually occu p ied b y the

p rop rie tor o f such establishm ent as his residence;

(2 ) any restaurant, cafeteria , lunchroom , lunch counter, soda

fou nta in , o r oth er fa c ility p r in cip a lly engaged in selling fo o d fo r

consum ption on the prem ises, in clud ing , but not lim ited to, any

such fa c ility located on the prem ises o f any retail establishm ent;

o r any gasoline s ta tion ;

(3 ) an jr m otion picture house, theater, concert hall, sports

arena, stadium or oth er p lace o f exh ib ition o r en terta inm ent; and

(4 ) any establishm ent ( A ) ( i ) w hich is p h ys ica lly located

w ith in the prem ises o f any establishm ent otherw ise covered by

th is subsection, o r ( i i ) w ith in the prem ises o f w hich is p h ysica lly

located any such covered establishm ent, and ( B ) w hich holds

itse lf out as serv ing patrons o f such covered establishm ent.

( c ) T h e operations o f an establishm ent affect com m erce w ith in the

m eaning o f this title i f (1 ) it is one o f the establishm ents described in

p a ra grap h (1 ) o f subsection ( b ) ; (2 ) in the case o f an establishm ent

described in p aragraph (2 ) o f subsection ( b ) , it serves or offers to

serve interstate travelers o r a substantial p ortion o f the fo o d w hich it

serves, o r gasoline o r other products w hich it sells, has m oved in

com m erce ; (3 ) in the case o f an establishm ent described in paragraph

(3 ) o f subsection ( b ) , it custom arily presents film s, perform ances, ath

letic team s, exh ib itions, o r other sources o f entertainm ent w hich m ove

in com m erce ; and (4 ) in the case o f an establishm ent described in

p aragraph (4 ) o f subsection ( b ) , it is p h ys ica lly located w ith in the

prem ises o f , o r there is p h ys ica lly located w ith in its prem ises, an

establishm ent the operations o f w hich affect com m erce w ith in the

m eaning o f this subsection. F o r p u r <oses o f this section, “ com m erce”

m eans travel, trade, traffic, com m erce, transportation , o r com m unica

tion am ong the several States, o r between the D istrict o f C olum bia and

any State, o r between any fo re ig n coun try o r any territory or p os

session and any State o r the D istrict o f C olum bia , o r between points

in the same State but th rough any other State o r the D istrict o f

C olum bia o r a fo re ig n country.

(d ) D iscrim in ation o r segregation b y an establishm ent is sup

p orted by State action w ith in the m eaning o f this title i f such d is

crim ination o r segregation (1 ) is carried on under co lo r o f any law ,

statute, ord inance, o r regu la tion ; o r (2 ) is carried on under co lo r o f

any custom or usage required o r en forced b y officials o f the State or

p o lit ica l subd ivision th e re o f; o r (3 ) is required by action o f the

State o r p o litica l subdivision thereof.

(e) The provisions of this title shall not apply to a private club

or other establishment not in fact open to the public, except to the

extent that the facilities of such establishment are made available

Equal a c c e ss .

Establishments

a ffe c tin g in

te rs ta te com

merce.

Lodgings•

Restaurants, e tc .

Theaters, s ta

diums, e tc .

Other covered

establishm ents•

Operations a f

fe c tin g com

merce c r i t e r ia .

’ ’ Commerce,”

Support by State

a c tio n .

Private esta b lish

ments.

Pub, Law 88-352

78 STAT. 244»

July 2, 1964

E ntitlem en t,

In ter feren ce .

R estraining

orders, e tc .

Attorneys1

f e e s .

N o tific a tio n

of S ta te .

Community Re

la tio n s Serv

ic e .

Hearings and

in v e stig a tio n s•

to tlie custom ers o r patrons o f an establishm ent w ith in the scope o f

subsection (b ) .

Sec. 202. A l l persons shall be en titled to be free , at any establish

m ent o r p lace , fr o m d iscrim ination o r segregation o f any k in d on

the g rou n d o f race, co lo r , re lig ion , o r n ationa l o r ig in , i f such d iscrim

ination o r segregation is o r p u rp orts to be requ ired by -any law ,

statute, ord inance, regu lation , rule, o r ord er o f a State o r any agency

o r p o litica l subdivision thereof.

Sec. 203. No person shall (a) withhold, deny, or attempt to with

hold or deny, or deprive or attempt to deprive, any person of any

right or privilege secured by section 201 or 202, or (b) intimidate,

threaten, or coerce, or attempt to intimidate, threaten, or coerce any

person with the purpose of interfering with any right or privilege

secured by section 201 or 202, or (c) punish or attempt to punish

any person for exercising or attempting to exercise any right or

privilege secured by section 201 or 202.

Sec. 204. (a ) W h enever any person has engaged o r there are

reasonable grou nd s to believe that any person is about to engage

in any act o r practice/ p roh ib ited b y section 203, a civ il action fo r

preventive re lie f, in clu d in g an ap p lica tion fo r a perm anent o r tem

p orary in ju n ction , restra in in g order, o r other order, m ay be

instituted by the person agg riev ed and, upon tim ely ap p lication , the

court m ay, in its d iscretion , perm it the A ttorn ey G eneral to intervene

in such c iv il action i f he certifies that, the case is o f general pu b lic

im portance. I Tpon ap p lica tion b y the com pla in an t and in such c ir

cum stances as the court m ay deem just, the court, m ay appoin t an

attorney fo r such com pla in an t and m ay authorize the com m encem ent

o f the civ il action w ith ou t the paym ent o f fees, costs, o r security.

(b ) In any action com m enced pursuant to th is title , the court, in

its d iscretion , m ay allow the p reva ilin g party , other than the L n ite d

States, a reasonable attorney ’s fee as part o f the costs, and the I nited

States shall be liable fo r costs the same as a p rivate person. _

( c ) In the case o f an alleged act o r p ractice p roh ib ited by this title

w hich occu rs in a State, o r p o litica l subdivision o f a State, w hich has

a State o r loca l law p roh ib it in g such act o r practice and establishing

o r au th orizin g a State o r loca l au th ority to grant o r seek re lie f from

such practice o r to institute crim inal proceed ings w ith respect thereto

u pon receiv in g n otice th ereof, no c iv il action m ay be brou gh t undei

subsection (a ) b e fo re the exp iration o f th irty days a fte r w ritten

n otice o f such alleged act o r practice has been g iven to the ap propria te

S tate o r loca l au th ority b y registered m ail o r in person , p p m d e d that

the court m ay stay proceed ings in such c iv il action pen d in g the

term ination o f State o r loca l en forcem ent proceedings.

(d ) In the case o f an alleged act o r p ractice proh ib ited by this

title w h ich occu rs in a State, o r p o litica l subd ivision o f a State, w hich

has n o State o r local la w p roh ib it in g such act o r p ractice , a c iv il action

m ay be brou gh t under subsection (a ) : Provided, T h at the court m ay

re fe r the m atter to the C om m unity R elations S erv ice established by

title X o f th is A c t fo r as lo n g as the court believes there is a reasonable

p ossib ility o f ob ta in in g v o lun tary com pliance, but. fo r not m ore than

s ixty d a y s : Provided further, T h a t u pon exp iration o f such s ix ty -d a y

p eriod , the court m ay extend such p eriod fo r an ad d itiona l period , not

to exceed a cum ulative total o f one hundred and tw enty days, i f it,

believes there then exists a reasonable p ossib ility o f securing voluntary

com plian ce. , „ ,, . ,. ,. ,

Sec. 205. The Service is authorized to make a full investigation of

any complaint referred to it by the court under section 204(d) and

may hold such hearings with respect thereto as may be necessary.

July 2, 1964

T he S erv ice shall conduct any hearings w ith respect to any such com

p la int in executive session, and shall n ot release any testim ony g iven

therein except by agreem ent o f a ll parties in vo lved in the com pla in t

w ith the perm ission o f the court, and the S erv ice shall endeavor to

brin g about a volun tary settlem ent between the parties.

S e c . 206. (a ) W henever the A ttorn ey G eneral has reasonable cause Suits by A tto r -

to believe that any person o r g rou p o f persons is engaged in a pattern ne7 General,

or practice o f resistance to the fu ll en joym en t o f any o f th e righ ts

secured b y th is title, and that the pattern o r practice is o f such a

nature and is intended to deny the fu ll exercise o f the righ ts herein

described, the A ttorn ey G eneral m ay b r in g a c iv il action in the a p p ro

priate d istrict court o f the U n ited States b y filin g w ith it a com pla in t

(1 ) signed by h im (o r in h is absence the A c t in g A ttorn ey G en era l),

(2 ) setting fo r th facts perta in in g to such pattern o r practice , and

(3 ) requesting such preventive re lie f, in clu d in g an ap p lication f o r a

permanent, o r tem porary in ju n ction , restrain ing order o r oth er order

against the person o r persons responsible fo r such pattern o r p ra c

tice, as he deem s necessary to insure the fu ll en joym ent o f the righ ts

herein described.

(b ) In any such p roceed in g the A ttorn ey G eneral m ay file w ith the

clerk o f such court a request that a court o f three ju d ges be convened

to hear and determ ine the case. Such request by the A tto rn e y G en

eral shall be accom panied by a certificate that, in his op in ion , the

case is o f general pu b lic im portance. A co p y o f the certificate and

request fo r a th ree-ju d ge court, shall be im m ediately fu rn ish ed by

such clerk to the ch ie f ju d g e o f the c ircu it (o r in his absence, the

presid ing c ircu it ju d g e o f the c ircu it) in w hich the case is pending.

U pon receipt o f the cop y o f such request it shall be the duty o f th e Designation of

ch ie f ju d g e o f the circu it o r the p resid ing c ircu it ju d g e , as the case judges,

m ay be, to designate im m ediately three ju d ges in such c ircu it, o f

w hom at least, one shall be a c ircu it ju d g e and another o f w hom shall

be a district ju d g e o f the court in w hich the p roceed in g w as insti

tuted, to hear and determ ine such case, and it shall be the duty o f

the ju d ges so designated to assign the case fo r h earing at the earliest

practicable date, to participate in the h earing and determ ination

thereof, and to cause the case to be in every w ay expedited . A n Appeals,

appeal fro m the final ju dgm en t o f such court w ill lie t o the Suprem e

Court.

In the event the A ttorn ey G eneral fa ils to file such a request in

any such p roceed ing , it shall be the du ty o f the ch ie f ju d g e o f the

district (o r in his absence, the actin g ch ie f ju d g e ) in w h ich the case is

pending im m ediately to designate a ju d g e in such d istr ict to hear and

determ ine the case. In the event that no ju d g e in the district is

available to hear and determ ine the case, the ch ie f ju d g e o f the district,

or the acting ch ie f ju d g e , as the case m ay be, shall ce rt ify th is fa c t

to the ch ie f ju d g e o f the c ircu it (o r in his absence, the acting ch ie f

ju d g e ) w ho shall then designate a d istrict o r circu it ju d g e o f the circu it

to hear and determ ine the case.

It shall be the duty o f the ju d g e designated pursuant to th is section

to assign the case fo r hearing at the earliest practicab le date and to

cause the case to be in every w ay expedited .

S e c . 207. (a ) T h e d istrict courts o f th e U n ited States shall have D is tr ic t cou rts,