Brief of Defendants-Appellants in Response to Motion to Dismiss

Public Court Documents

February 1, 1972

29 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Brief of Defendants-Appellants in Response to Motion to Dismiss, 1972. 40db4dd5-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/81adb7a7-aada-498d-b68e-66f66b894247/brief-of-defendants-appellants-in-response-to-motion-to-dismiss. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

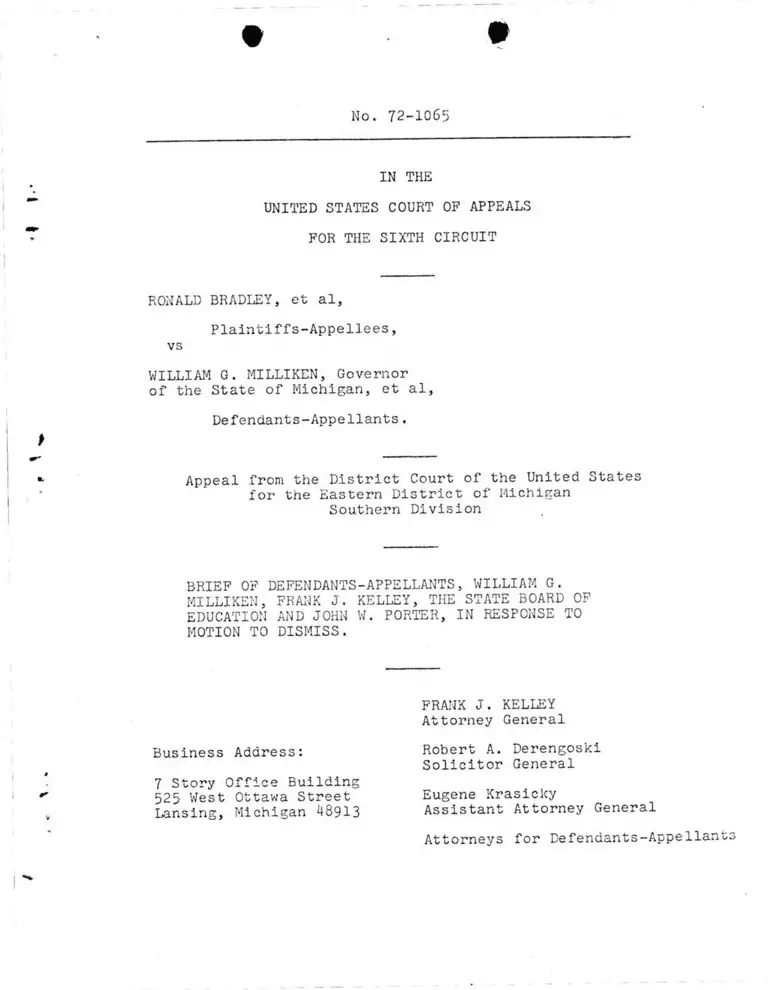

No. 72-1065

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

RONALD BRADLEY, et al

Plaintiffs-Appellees

vs

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, Governor

of the State of Michigan, et al,

Defendants-Appellants.

Appeal from the District Court of the United States

for the Eastern District of Michigan

Southern Division

BRIEF OF DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS, WILLIAM G.

MILLIKEN, FRANK J. KELLEY, THE STATE BOARD OF

EDUCATION AND JOHN W. PORTER, IN RESPONSE TO

MOTION TO DISMISS.

FRANK J. KELLEY

Attorney General

Business Address: Robert A. Derengoski

Solicitor General

7 Story Office Building

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

Eugene Krasicky

Assistant Attorney General

Attorneys for Defendants-Appellants

TABLE OP CONTENTS

Table of Cases — -----------------------------

Statement of the Issue -----------------------

Statement of Facts --------------- — ---------

Argument----------- ------ --------------------

I. The order is a final decision-------- -

II* Taylor is unsound and should not be

followed--- ---------------------------

TABLE OF CASES

Bradley v Milliken, 438 F2d 9^5 (1971) ------

Bradley v School Board of City of

Richmond, Virginia, 51 FRD 139 (ED va, 1970)-

Same, F2d ___, January 5, 1972 — ---- — —

Brown Shoe Co v United States, 370 US 294 (1962)

Board of Education of Oklahoma City Public

Schools v Dowell, 275 F2d 1 5 8 ------- --------

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County,

Florida v Braxton, 326 F2d 6l6, cert den

377 US 924 (1964) ------------- -------------- 13>

Dickinson v Petroleum Conv Corp, 338 US 507,

508 (1950) ----------------------------------

Gillespie v United States Steel Corp,

321 F2d 5 1 8-- -------------------------------

Kelley v Metropolitan County Board of

Education of Nashville, 436 F2d 8 5 6 ------- —

Kelly v Greer, 354 F2d 209 --------------------

1

1

2

11

18

6, 20

20

8, 16

16

14, 16

4

10, 16

10

16

x

9

Lee v Macon County Board of Education,

267 P Supp 458 (MD ala, 1967)--- --------------- 5

Lansing District v State Board of Education,

367 Mich 591 (1962) — ----- -------------— ------ 5

Mapp v Board of Education of Chattanooga,

No. 14, 444, 295 F2d 6 1 7------- ------- ---------12, 13, 17

McCoy v Louisiana State Board of Education,

332" F2d 9 1 5 ------------------------------------- 15

Penn School District No. 7 v Lewis Cass

Intermediate School District Board of

Education, 14 Mich App 109, 120 (1968) --------- 5

Stamicarbon, N.V. v Escambia Corp, 430 F2d 920.-- 15

Robinson v Shelby County Board of Education,

Nos. 20123 and 20124 ----- ---------------------— 17

Swann v Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd of Ed,

402 US 1; 91 S Ct 1267 ( 1971)------ ------------ 6

,, 1 O'P n n r~\ f 1\7 o w R n n V i P 1 1

X U J Ju 'JA V Ju JV U i. U W j - U U V A ^ U ^ ^ + -------y

288 F2d 600 — --- ------— -------------------*--- 12> !3S

Trahan v Lafayette Parish School Bd,

330 F Supp 450 (WD La, 1971) ----------- — ----- 7

United States v Associated Air Transport, Inc.

256 F2d 857 -------- ---------------------------- 14

US v Board of School Commissioners, Indianapolis,

332 F Supp 655 --- ------------------------------- 6

Welling v Livonia Board of Education, 382 Mich 620 5

In re Wingreen Co, 412 F2d 1048 --------------- ■ I4

Workman v Board of Education of Detroit,

18 Mich 399 (1869) ------------ ---------------- 6

ii

1 6, 1'

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUE

Is the order dated November 5, 1971, which

incorporates the findings of fact and conclusions of

law that the state of Michigan has committed acts which

have been causal factors in the de_ jure segregated

condition of the Detroit public schools contained in

the District Court's Ruling on the Issue of Segregation,

and which directs these defendants to submit a metro

politan plan of desegregation, an appealable decision or

order?

The state defendants contend "yes.

STATEMENT OF FACTS AND PROCEEDING

These defendants, collectively, will be called

"state defendants" and individually by title of their

offices.

The facts stated in plaintiffs' motion under

the title of "procedural history of the litigation" are

substantially correct and need not be amplified. The

state defendants do not see the point of plaintiffs'

self-serving statement, "Although plaintiffs have, from

the outset, questioned the 'appealability' of the

district court's order," in a procedural history of the

litigation.

In their remarks on page 5 of their motion, under

the heading "the substance of the order appealed from,"

plaintiffs have been somewhat less than candid, particularly

in view of their remark on page 6 that it was permissible

for the state defendants to insist upon a formal order,

despite their previous waiver. On October 7, 197i} the

state defendants prepared a proposed order reflecting

the directions made by the district judge on October 4,

1971, and forwarded it to plaintiffs' attorneys. A copy

of the letter of transmittal is attached hereto as

Appendix 1. Three weeks later the state defendants'

attorneys received a copy of a letter from plaintiffs

-2

«

attorney to Mr. Ritchie, attorney for some intervening

defendants, in which plaintiffs’ attorney said that he

had misplaced the proposed order, but that he would not

approve it anyway because he wanted to be consistent.

A copy of this letter is attached as Appendix 2.

Thereafter, the state defendants’ attorneys

submitted the order to the district judge for entry,

with the result that the district judge prepared his

own order, incorporating his findings of fact and

conclusions of law, and entered it on November 5, 1971.

It appears that:

1. Plaintiffs did not want an order entered -

without such an order the district judge's decision on

the fundamental Issue could not be reviewed.

2. If plaintiffs were actually thinking in

terms of waiver, they would have raised the point

immediately upon receipt of the proposed order trans

mitted on October 7, 1971, rather than misplacing the

proposed order and claiming consistency three weeks

later.

-3-

ARGUMENT

I.

THE ORDER OF THE DISTRICT COURT ENTERED

ON NOVEMBER 5, 1971, IS A FINAL ORDER

WITH REGARD TO THE STATE DEFENDANTS.

In Dickinson v Petroleum Conv Corp, 338 US 507,

508 (1950), Mr. Justice Jackson began the Court’s Opinion

by saying:

"The only issue presented by this case turns

on the finality of a judgment for purposes

of appeal, a subject on which the volume of

judicial writing already is formidable."

In the ensuing 20 years there does not appear to have been

a lessening in either volume or formidability.

The relative statutory provision is:

"The courts of appeals shall have jurisdiction

of appeals from all final decisions of the

district courts of the United States, the

United States District Court for the District

of the Canal Zone, the District Court of Guam,

and the District Court of the Virgin Islands,

except where a direct review may be had in

the Supreme Court." 28 USC 1291

The decision and order of the District Court are

unique. First, by requiring the submission of a metropolit

plan of desegregation they grant relief for which the plain

tiffs did not ask.

Second, under the Michigan Constitution of 1963

control over the public school system is lodged in the

legislature and delegated by it to local school districts

which are given plenary powers by the legislature to

carry out the delegated functions given them by the

legislature. Lansing District v State Board of Education,

367 Mich 591 (1962). Welling v Livonia Board of Education.

382 Mich 620 (1969). No power over the operation of the

public school system is lodged in the Attorney General or

the Governor, and the State Superintendent and State Board

of Education have only limited powers with regard to local

school districts, and none with regard to the unilateral

alteration of school district boundaries or the reorgani

sation of school districts as no such power uas ueen

conferred upon them by the legislature. Penn School

District No. 7 v Lewis Cass Intermediate School District

Board of Education, 14 Mich App 109, 120 (1968). Yet,

the District Court has not only found these defendants

responsible in some degree for a dual school system in

Detroit, but has ordered them to present a plan of

desegregation which includes not only the Detroit School

District but also an undetermined area outside of Detroit

consisting of school districts that were not parties to

this suit. This is not the case of Lee v Macon County

Board of Education, 267 F Supp 458 (MD Ala, 1967), aff'd

per curiam sub nom, Wallace v US_, 389 US 213 (1967),

-5-

where certain state officers usurped power to interfere

with the District Court's desegregation decree.

Third, for more than 50 years by statute the

boundaries of the Detroit School District and of the

City of Detroit have been coterminous. 1919 PA 65, § 3;

1927 PA 319, Part 1, Ch 8, § 3; 1955 PA 269, § 183; MCLA

3*10.183; MSA 15.3183. The District Court's decision and

order are the first holding by a trial court requiring the

submission of a "metropolitan plan" to desegregate a local

school district in a jurisdiction where the separation of

the races was never imposed by lav/ and where school

district boundaries were not established for the purpose

of separating the races or for the purpose of creating

racially separate school systems. Contrast Bradley v

School Board of City of Richmond, Virginia, 51 FRD 139

(ED Va, 1970); US v Board of School Commissioners,

Indianapolis, Indiana, 332 F Supp 655 (SD Ind, 1971)•

In Workman v Board of Education of Detroit,

18 Mich 399 (1869), the Michigan Supreme Court ruled

that an attempt to establish a segregated district in

Detroit violated state law.

Although, in Swann v Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Bd of Ed, 402 US 1; 91 S Ct 1267, 1284 (1971), the Cour.t

6-

holds out the hope that there can be a final, in the

sense of last, judgment in a case where a dual school

system is claimed, but in the same paragraph then adds.

"This does not mean that federal courts are without

power to deal with future problems."

In Trahan v Lafayette Parish School Bd, 330

F Supp 450 (WD La, 197D, the court began its opinion

by noting that the case, filed on March 5, 1965, was

before the court for the fifth time on motion by

plaintiffs for further relief. It then added that in

this type of case the process of making remedial

adjustments Is a continuing one.

Although the subject matters are as diverse

as cattle and people, a divestiture action by the United States

to redress a violation of § 7 of the Clayton Act is a

perfect parallel to a school desegregation case in terms

of the methodology of remedy. The district court in a

section seven case first makes a finding of illicit

acquisition or merger and then orders the submission

of a desegregation plan. In the anti-trust case where

the United States is a party there is a provision for a

direct appeal to the Supreme Court from "the final judgment

of the district court," while under 28 USC 1291 the appeal

7-

is to the court of appeals from the "final decisions

of the district courts." Thus, in Brown Shoe Co v

United States, 370 US 294 (1962), where the government

sought to enjoin the consummation of a merger between

Brown and Kenney as a violation of the Clayton Act,

a motion for a preliminary injunction was denied, and

the companies were permitted to merge, provided that

their businesses be operated separately and their assets

be kept separate. Even in the nature of the temporary

relief requested and granted there is a close parallel

to a school desegregation suit in that while the district

courts do not necessarily grant all of the relief pende 11te

requested by the plaintiffs, arrangements are usually made

either through agreements or preliminary injunctions so

that actions are not taken during the pendency of the

action by the school district that will make desegregation

more difficult in the event that a dual school system is

adjudged.

From a decree of the district court ordering

divestiture, the defendant appealed to the Supreme Court.

Although the government did not contest jurisdiction, the

court noted that jurisdiction cannot be conferred by consent

and, therefore, a review of the sources of the court’s

jurisdiction is the threshold inquiry.

-8-

It then adopted what it called "the touchstone

of federal procedure," "a pragmatic approach to the

question of finality." The court held that the district

court's decree had sufficient indicia of finality to be

properly appealed because:

1. The decree disposed of the entire

complaint - every prayer for relief

passed upon.

2. The sole remaining task of the district

court would be the acceptance of a plan

for full divestiture and the supervision

of the plan accepted.

3. The defendant did not attack the order of

divestiture as such, its contention was

that no order of divestiture would have

been proper. Since divestiture was

considered below and attacked on appeal

v*> vi ri 1 1 /-s y-v A v* rs* k ̂ n t n -v>^ n k -i' 4--? t rX U U ViAXiigj -i- tli/a. » t

judicial considerations of the same

question in a single suit will not occur.

4. The nature of the divestiture order will

be such that it can only be formulated

after careful and extended negotiation.

Because third persons, such as buyers

and bankers must be found to accomplish

the divestiture, having the underlying

decision unsettled would only make still

more difficult the expeditious enforcement

of the anti-trust laws.

5. The final consideration is precedent - the

Supreme Court has consistently reviewed

district court anti-trust decrees con

templating future divestiture plans.

It would appear that the above rationale is

applicable in toto to a school desegregation case:

-9-

1. The decree disposed on the entire com

plaint - every prayer for relief was

passed upon.

2. The sole remaining task for the district

court will be the acceptance of a plan

for full desegregation and the supervision

of the plan accepted.

3. The defendants here do not attack the order

of desegregation as such; it is their

contention that no order of desegregation

should have been entered. The attack is on

all or nothing basis.

4. The desegregation plan will require careful

formulation and, undoubtedly, extended

hearings if not negotiations.

5. As we have indicated, the district court's

judgment is without precedent. Appellate

review at this point will be a material

factor in alleviating the unsettling

influence and will materially lessen the

djffir.uity in effectuftjng the desegregation

plan, if the district court's judgment is

affirmed.

6. This court has reviewed district court

judgments which are fundamental to the

further conduct of the case. Order

filed June 20, 1961 in Happ v Board of

Education of Chattanooga, No. 14,44L\.

Gillispie, infra. Kelley v Metropolitan

County Board of Education of Nashville,

436 F2d 856" (CA b, 1970) .

This court decided Gillespie v United States Steel

Corp 321 F2d 518 (CA 6, 1963), rev'd on other grounds,

379 US 148 (1964). The district court had granted a motion

to strike certain allegations of the complaint and the plain

tiff appealed. Although Judge McAllister remarked that the

-10-

district court's order, on its face, appeared to be

interlocutory and not appealable, on this issue he

concluded as follows:

"The question of whether the order of the

District Court is an appealable or an

nonappealable order is a close one. We

would, at this time, in the interests of

the due and proper administration of

justice, prefer to decide the appeal on

the merits, if that is possible; we think

it is. . . ." p 522

In affirming on this point, the Supreme Court

said:

". . . We think that the questions presented

here are equally 'fundamental to the further

conduct of the case.' . .-. [I]n light of the

circumstances we believe that the Court of

Appeals properly implemented the same policies

Congress sought to promote in § 1292(b) by

treating this obviously marginal case as

final and appealable under 28 USC § 1291

(1958 ed)." 379 US 148, 154.

II.

THE HOLDING IN TAYLOR v BOARD OF EDUCATION OF

NEW ROCHELLE, 288 F2d 600 (CA 2, 19 6 1) IS

UNSOUND AND SHOULD NOT BE FOLLOWED.

-11-

In their motion at page 7, plaintiffs say that

the only possible source for this Court’s jurisdiction

over the instant appeals is 28 USCA 1292(a)(1)., reading

as follows:

"(a) The courts of appeal shall have juris

diction of appeals from:

(1) Interlocutory orders of the

district courts of the United States, the

United States District Court of the District

of the Canal Zone, the District Court of

Guam, and the District Court of the Virgin

Islands, or of the judges thereof, granting,

continuing, modifying, refusing or dissolving

injunctions, or refusing to dissolve or modify

injunctions, except where a direct review may

be had in the Supreme Court;"

They then cite and discuss Taylor v Board of Education of

New Rochel£, 288 F2d 600 (CA 2, 1961), not only for this

proposition but also for the proposition that a judgment

of a district court is ordering the filing of a desegregation

plan is not an order "granting, continuing, modifying, refusing

or dissolving injunctions." Taylor cites Mapp, No. 14,444,

memorandum opinion filed January 20, 1961 as the law of the

Sixth Circuit, but refuses to follow it.

The state defendants respectfully submit that on

the basis of the authorities cited earlier in this brief

plaintiffs' assumption of "only possible source" is mani

festly in error. The state defendants further submit that

12-

plaintiffs' reliance on Taylor without discussing the

later reported cases of other circuits holding to the

contrary is also in error.

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County,

Florida v Braxton, 326 F2d 6l6 (CA 5, 1964), cert den 377

US 924 (1964), raised the initial question of whether the

order appealed from was appealable. As distinguished from

the case at bar, the board was challenging not the fact

of desegregation, but the form of the order requiring it.

The order appealed from contained preliminary paragraphs

restraining, e.g., "continuing to operate a compulsory

bi-racial school system in Duval County, Florida; assigning

pupils to schools on the basis of race and color of the

pupils, etc.," and then stated that these paragraphs shall

not be effective until the further order of the court, and

further directed the defendants to submit a detailed and

comprehensive plan for putting the preliminary paragraphs

into effect. The Court of Appeals in a two to one decision

held the district court's order to be an injunction and

appealable under 28 USC 1292(a)(1).

The Court considered and distinguished Taylor,

supra, by saying that in Duval the language of the order

(injunction) was different from Taylor in that the plan was

-13-

to comply with specific provisions set forth in the

postponed injunction. However, it did go on to say that

to the extent that its definition of an injunction may

differ from the understanding of what constitutes an

injunction as expressed by the Court of Appeals for the

Second Circuit, it must respectfully disagree. Certainly,

when a panel of one circuit tells a panel of another circuit

that it erred, this should be done as ambiguously and

indirectly as possible. The fact remains that the Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit was not impressed by the

decision of the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

The extent of this disagreement is made even

clearer by United States v-Associated Air Transport, Inc,

256 F2d 857 (CA 5, 1958), where the Court held that a

conditional injunctive order is not appealable until the

condition is complied with.

Duval has been cited as controlling in a number

of later cases in the Fifth Circuit, all requiring the doing

of an act in the course of litigation as opposed to an order

determining a liability. In the case of In re Wingreen Co,

412 F2d 1048 (CA 5, 1969), in a bankruptcy chapter X

reorganization the Internal Revenue Service was ordered

to audit the debtor's records for the purpose of determining

-14-

whether there might be a tax refund. On appeal the

trustee claimed the nonappealability of the order. The

Court held that the order had sufficient operative finality

to be appealable.

In Stamicarbon, N.V. v Escambia Corp, 430 F2d 920

(CA 5j 1970), a patent infringement suit, the Court said

that the thread that runs through the cases is the idea

"that we must look at what the district court did and

measure that against the standard of section 1292 to determine

appealability."

To same effect in the segregation context is

McCoy v Louisiana State Board of Education. 332 F2d 915

(CA 5, 1964), where a black student sought admission to a

college limited by state law to white students only. The

district court refused to act on the plaintiff's motion for

a preliminary injunction until she sought mandamus in the

Court of Appeals. Then the district court dismissed the suit

as to the state board and ruled that the board members were

necessary parties. In determining that the district court's

order was appealable, the Court said:

"In view of the short time remaining until

the start of the summer session, it is clear

that the practical effect of the court's order

was to deny the preliminary injunction. Thus

the district court's order was appealable under

28 USC § 1292(a) or 28 USC 1291." P 917

-15-

Although the Court did not rely upon Duval, supra,

ln Kelly v G r e e r , 354 F2d 209 (CA 5, 1965), the Court held

that an order quashing a writ of assistance was appealable.

It said:

"Furthermore, the Supreme Court has recently

stated that a 'final decision' within the

meaning of section 1291 'does not necessarily

mean the last order possible to be made in

the case' and that the requirement of finality

is to be given a 'practical rather than a

technical construction.'" [citing Gillespie,

supra.] p 210 ..

In Board of Education of Oklahoma City Public Schools

v Dowell, 275 F2d 158 (CA 10, 1967), an order directing the

filing of a desegregation plan was appealed. The Court

decided the matter on the merits without raising the question

of the appealability of the order.

Now for Taylor, 288 F2d 600 (CA 2, 1 9 6 1). While

Judge Friendly's opinion is entitled to the greatest respect,

he was unable to persuade one of his own brethren, as he was

unable to persuade Judges Tuttle and Johnson in Duval.

Second, Taylor has not been followed in another circuit and,

as nearly as can be determined, has not been cited as authority

in a majority opinion in a case which involved the type of

order considered.

Third, Taylor was decided before either Gillespie,

supra, or Brown Shoe, supra.

Taylor is also distinguishable from thas case of

Bradley because the district judge in his decision expressly

stated that it was "unnecessary at this time to determine

the extent to which each of the items of relief requested

by plaintiffs will be afforded." As the state defendants

have indicated above, the district judge in the case at bar

passed upon the entire complaint and claims for relief.

At page 604 of Taylor attempts to equate the order

directing that a desegregation plan be submitted after a

full hearing on the merits to the order of a judge directing

the parties (actually their attorneys) to file briefs, findings and

other papers. The analogy is too unbelievable to persuade.

Plaintiffs appear to endorse Judge Friendly's

criticism of this Court in its handling of Mapp v Board of

Education, 14,444 and 14,517, 295 F2d 617. If this Court's

handling of Mapp did present a problem, there appears to be

no evidence of it in the opinion. Second, Tennessee had a

dual school system by statute. Therefore, the issue, as

opposed to the issue in the case at bar, was not whether a

dual school system existed, but how it was going to be

dismantled. For the same reason, plaintiffs' citation of

Robinson v Shelby County Board of Education, Nos. 20123 and

20124, is inappropriate. As in Mapp, neither of these cases

from Tennessee really involve the question of whether a dual

-17-

+

school system existed. After Brown I, this was a foregone

conclusion.

• CONCLUSION

In the second appeal in this cause, this Court

emphatically made the point that there should be a prompt

hearing on the merits, with appropriate findings of fact

and conclusions of law in accordance with FR Civ P 52a.

Bradley v Milliken, 438 F2d 945 (1971). The trial has been

completed, the district judge has made his findings of fact

and conclusions of law of de jure segregation in the Detroit

school district as a result of the conduct of the defendants,

and these findings and conclusions have been incorporated

in the order entered November 5, 1971. The fundamental

question of plaintiffs’ right to relief has been conclusively

established. The state defendants are now seeking appellate

review on this question of fundamental importance to this

cause.

The defendants have not sought a stay of proceedings

pending this appeal. Thus, the appeal enhances the expeditious

resolution of the questions presented in this cause. The

process of formulating and submitting desegregation plans,

both intra-district and metropolitan in scope, is going

forward pending appeal.

-18-

If this Court reverses on the finding of de_ jure

segregation, there will be no need for further remedy

proceedings. If this Court affirms, then any subsequent

appeals will be limited to the question of the appropriate

scope and form of the remedy, with the exception of the

question of faculty segregation, which will be discussed

infra.

Further, it may very well be that the relief afforded

herein will be ordered implemented in stages. One order may

implement an intra-district remedy with a subsequent order

implementing some form of metropolitan remedy for the reason

that the process of formulating a metropolitan remedy is

obviously much more complex and time consumings Which

remedial order will be a final decision for purposes of

appeal?

Moreover, the parties are presently in the process

of preparing and submitting metropolitan plans to the district

court. A motion to join 85 suburban school districts as parties

is currently pending before the trial judge. The state

defendants' attorneys are informed and have good reason to

believe that a substantial number of suburban school districts

and other persons residing in the suburban school districts

intend to file intervention motions in this cause. The

precedent established in a case involving a metropolitan

-19-

remedy is to order or allow the affected school districts

to become parties to the case with further evidentiary

proceedings relating to such parties so that they may obtain

due process of law. Bradley v School Board of Richmond,

Virginia, 51 FRD 139 (ED Va, 1970). Same, ____F2d _____

(Jan. 5, 1972). Given the complicated question of a

metropolitan remedy and the joinder or intervention of other

parties, the additional proceedings before the district court

will be substantial. Thus, if appeal is now denied, it will

be very difficult at a later date to fairly review the

fundamental question of right to relief against the original

defendants as distinguished from the question of remedy.

In addition, the cost involved in preparing and

implementing desegregation plans involving either a school

district with almost 300,000 students or a metropolitan area

with scores of school districts and approximately 900,000

students is clearly enormous. Such massive undertakings,

involving the expenditure of very substantial sums of public

funds, should not be implemented prior to appellate review

on the basic question of do jure segregation.

Finally, there is plaintiffs' cross-appeal on the

question of faculty segregation. If this appeal is dismissed,

the district court will order implementation of a remedy

-20-

involving the students prior to a subsequent appeal. A

stay of such order may or may not be sought or obtained.

Plaintiffs will then appeal the faculty question. If

they prevail on that question, further remedial orders

will be required from the district court. Once again, the

operation of the affected school district or school districts

will be disrupted. Many children, having recently been

required to attend a new school, will then be required to

adjust to new teachers in their classrooms and in their

school buildings. The continuity and stability of their

educational experience will once again be disturbed. The question

of remedy should be approached within the context of an

appellate decision settling the question of the scope of the

right to relief as a guide to the remedy.

It is respectfully submitted that the plaintiffs

herein seek to avoid entirely appellate review on the merits

or, if that is not feasible, to postpone such review until

the question of relief is an accomplished fact. The state

defendants are seeking appellate review of the district

court's final and conclusive decision, reduced to a written

order, that ae jure segregation exists in the Detroit school

district as a result of the conduct of the state defendants.

f t

The state defendants respectfully request that this Court

deny plaintiffs' motion to dismiss the appeal of the state

defendants herein.

Respectfully submitted,

FRANK J. KELLEY

Attorney General

Robert A. Derengoski

Assistant Attorney General

Gerald F. Young

George L. McCargar

Assistant Attorneys General

Attorneys for State Defendants

Business Address:

7 Story Office Building

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

-22-

October 7, 1971

Mr. Louis R. Lucas

Attorney at Law

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

He: Bradley, et al v. Hilllken

' iiO. 35257

Dear Mr. Lucas:

Enclosed please find a proposed order reflecting

the decisions made by Judge Roth on October 1 9 7 1.

an order

suggested

for their

note the

It appears that some of my clients v/lsh to read

of the court, I contacted Judge Roth and he

that I prepare it and circulate to all parties

approval. If it meets with your approval, please

same and send it on to Mr. Bushnell for his approval

Sincerely,

LK: hb

Erie.

Eugene Krasicky

Assistant Attorney General

APPENDIX 1

Octomr 21 f 1 9 7 1

.% le x d a u c r u . R i t c P i s , s & q,

2333 Guardian Builciinr

D e t r o i t . * r i o i i i ^ a a 4 d 226

Rial nradi^y v. bill! -Iv 4̂4 i

g o . 33257

near dr. 3iteh£«o

hr.. arasicxf naa previously aut-sitcoa to k o a

propoaed order royardrnp tna tiuiu-j senodui®. tor 4u&-

ii’.irsioa oif plans and a report and evaluation of tho

iiaanot l*lan for ty approval, x nae no nej<Se«?»ity ?or

-,ii w.,I lli’’ «i“i Or-..U,.' US.,, k-wiUj. ■: ><lu; i.j - ̂̂ Ca.UUt

ca/.au v ail parties ac t.*a previous conference- la open

Court, 1 save not u ,pxovou :.r. j.rasi c,;y ‘ ,j orcar. i ii

notifyinj you so taat you xaf take wnsstevar action with

regard to the or*?r yon d-?.so necessary, anJ tuen pass

it on to dr. uusiViiail.

1 lavs wisplaosc*. Gr. krasiCKy * a proposed ora-ar

ana am p? copy of tnis is tear rcpuasciua tnafc no iumisn

you with another copy.

• Very truly - yours-.

PCui-8 , tiiCiiS

LP.L, i f # ‘

cc ■ honorable! dfcaphen J. doth

George t. ;-.u»ha«il, dr.,- cut.

Cujtnu r.rasic:;j’, is;i .w

i *<’. J w C - 0 1 *3 i i ^ i-j-i-*"’' «

APPENDIX 2

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that a copy of the foregoing

brief in response to motion to dismiss was served upon the

following named counsel of record by United States mail,

postage prepaid, addressed to their respective business addresses

Messrs. Louis R. Lucas and

William E. Caldwell

Mr. Nathaniel R. Jones

Messrs. J. Harold Flannery,

Paul R. Dimond and

Robert Pressman

Mr. E. Winther McCroom

Messrs. Jack Greenberg and

Norman J. Chachkin

Mr. George T. Roumell, Jr.

Mr. Theodore Sachs

Mr. Alexander B. Ritchie

Ehgene Krasicky ■

Assistant Attorney General

Dated: February 1, 1972