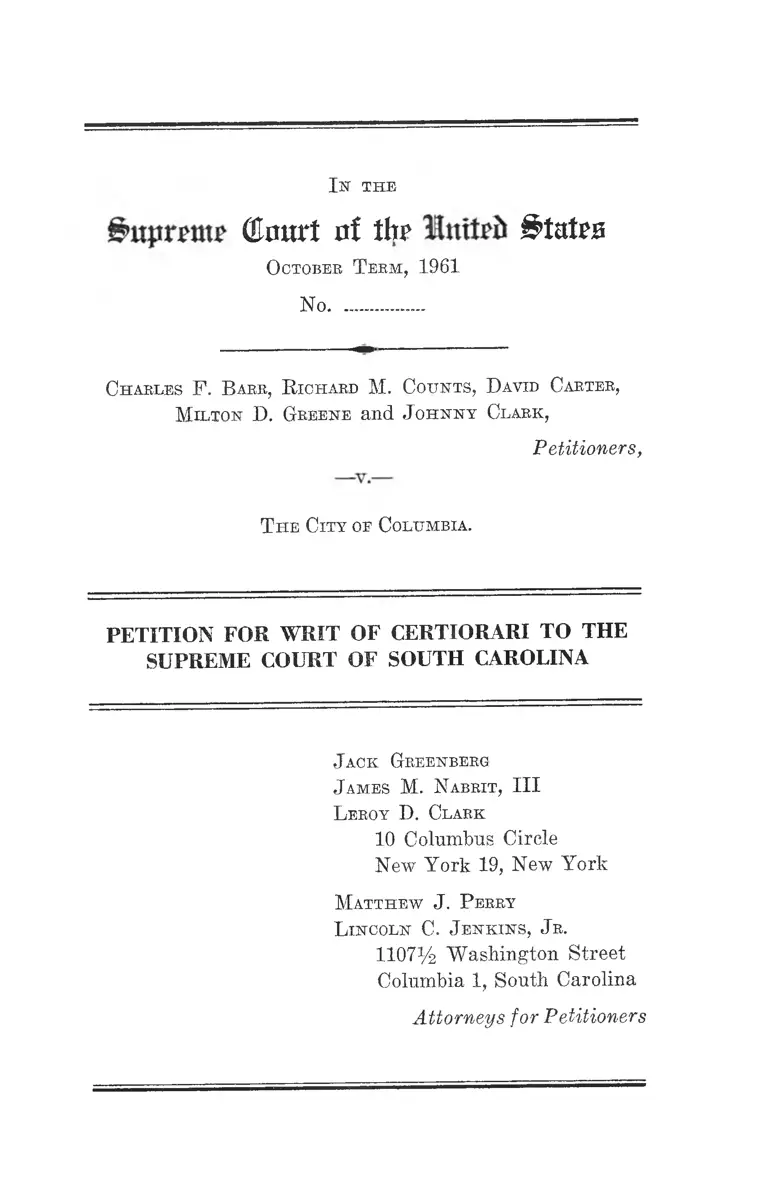

Barr v. City of Columbia Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of South Carolina

Public Court Documents

January 8, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Barr v. City of Columbia Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of South Carolina, 1962. cf2b378a-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/81da7b7b-5573-400f-8ff1-4fd7f04eab7f/barr-v-city-of-columbia-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-south-carolina. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

Isr t h e

(Emtrt nf tht> States

O ctober T erm , 1961

No.................

Charles F . B arr, R ichard M. C ounts, D avid Carter,

M ilton D. Greene and J o h n n y Clark ,

Petitioners,

T h e C ity of Columbia .

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, I I I

L eroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

M atthew J . P erry

L incoln C. J e n k in s , J r.

1107% Washington Street

Columbia 1, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Citation to Opinion Below ...... 1

Jurisdiction..................................................................... 2

Questions Presented ..................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ..... 3

Statement ....................................................................... 4

How the Federal Questions Were Raised..................... 6

Reasons For Granting the W rit................................... 8

I. The Decision Below Conflicts With Prior De

cisions of This Court Which Condemn the Use

of State Power to Enforce a State Custom of

Racial Segregation .......................................... 8

II. The Decision Below Conflicts With Decisions

of This Court Securing the Right of Freedom

of Expression Under the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States 19

Co n c l u s io n ................................................................................... 26

A p p e n d ix ............................................................................................. l a

T able op Cases

Abrams v. United States, 250 U. S. 616 ............... 20

Avent v. North Carolina, No. 85, October Term 1961 .. 10

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1961) ..... 18

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F. 2d 531, note

1 (5th Cir. 1960) ......................................................... 18

11

PAGE

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454 ................................ 9

Breard v. Alexandria, 341 U. 8. 622 ............................ 15, 20

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 XL S. 483 ................ . 10

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 ............................11,19

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 .............................................................................14,15

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 ........................ 25

Champlin Kef. Co. v. Corporation Com. of Oklahoma,

286 U. S. 210 ............................................................. 25

City of Charleston v. Mitchell, filed Dec. 13, 1961,

-----S. C.----- , ------S. E. (2d) ........ .......................... 8

City of Greenville v. Peterson, filed Nov. 10, 1961

-----S. C .------ , 122 S. E. (2d) ................................. 8

Civil Eights Cases, 109 IT. S. 3 ................................10,16

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 .......................................... 19

District of Columbia v. John E. Thompson Co., 346

U. S. 100 .................................................................... 13

Frank v. Maryland, 359 IT. 8. 360 ............................... 16

Freeman v. Eetail Clerks Union, Washington Superior

Court, 45 Lab. Eel. Ref. Man. 2334 (1959) .............. 22

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 ....14,16,17,18,19, 21, 25

Hudson County Water Co. v. McCarter, 209 U. S. 349 .... 15

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. S. 643, 6 L. ed. 2d 1081..............15,16

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501.......... ..................... 11, 21

Martin v. Struthers, 319 U. 8. 141................................ 20

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167....................................... . 9

Munn v. Illinois, 94 U. 8. 113 .................................. 11,18

Napue v. Illinois, 360 U. S. 264 ................................... 9

N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 ..................... 20

Ill

PAGE

N. L. R. B. v. American Pearl Button Co., 149 P. 2d

258 (8th Cir. 1945) ..................................................... 21

N. L. R. B. v. Fansteel Metal Corp., 306 U. S. 240 .... 21

People v. Barisi, 193 Mi sc. 934, 83 N. Y. S. 2d 277

(1948) ........................ ................................................. 21

People v. King, 110 N. Y. 418, 18 N. E. 245 (1888) .... 13

Peterson, et al. v. City of Greenville, 30 U. S. L.

Week 7236 .................................................................. 24

Pickett v. Kuclian, 323 111. 138, 153 N. E. 667, 49

A. L. R. 499 (1926) ................................................. 13

Poe v. Ullman, 367 U. S. 497, 6 L. ed. 2d 989 ......... 15

Railway Mail Ass’n v. Corsi, 326 U. S. 88................ 13,14

Republic Aviation Corp. v. N. L. R. B., 324 IT. S. 793 ....11, 21

Schenck v. United States, 249 U. S. 47........................ . 22

Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 91 ........................ 9

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ........... ....9,10,11,15

Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 205 ................................ 25

State v. Gray, 76 S. C. 83 .................... ......................... 23

State v. Green, 35 S. C. 266 ............................ 23

State v. Halfback, 40 S. C. 298 ....................................... 23

State v. Mays, 24 S. C. 190................. 23

State v. Tenney, 58 S. C. 215......................................... 23

State of Maryland v. Williams, Baltimore City Court,

44 Lab Rel. Ref. Man. 2357 (1959) ............................ 22

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 ......................... 20

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199............. 24

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 .....................15, 20, 21

United States v. Willow River Power Co., 324 U. S. 499 11

IV

PAGE

Western Turf Asso. v. Greenberg, 204 U. S. 359 .......... 13

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette,

319 IT. S. 624 ............................................................ 20

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 ............................ 26

S tatutes

South Carolina Code, §15-909 .................. .................... 3 4

South Carolina Code, 1952, §16-386, as amended 1960 ..3, 4, 8

Oth er A u thorities

Annotation 49 A. L. R. 505 ...... ............................. ....... 13

Konvitz, A Century of Civil Rights, Passim (1961) .... 14

1 st th e

ihtpmur Court of % luttrsi Stairs

O ctober T erm , 1961

No.................

Charles F. B arr, R ichard M. Counts, D avid Carter,

M ilton D. Greene an d J o h n n y Clark ,

— v . — •

Petitioners,

T h e C ity oe Columbia.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of South Carolina,

entered in the above entitled case on December 14, 1961

rehearing of which was denied January 8, 1962.

Citation to Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina,

which opinion is the final judgment of that Court, is re

ported at 123 S. E. 2d 521 (1961) and is set forth in the

appendix hereto, infra, pp. 8a-12a. The opinion of the Rich

land County Court is unreported. and is set forth in the

appendix hereto, infra, pp. la-7a.

2

Jurisdiction

The Judgment of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

was entered December 14, 1961, infra, p. 12a. Petition

for rehearing was denied by the Supreme Court of South

Carolina on January 8, 1961, infra, p. 13a.

Questions Presented

1. Whether the Court below denied petitioners’ rights

under the due process and equal protection clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States to freedom from state supported racial discrimina

tion and freedom of expression, where petitioners have been

convicted of the crimes of trespass and breach of the peace

for having remained seated at the lunch counter of a li

censed drug store which was open to the public (including

petitioners), but was pursuing a practice of serving Negroes

take-out food orders only while serving white persons at

counter seats, in conformity with state custom of segrega

tion, and where petitioners were ordered to leave solely on

the basis of race and were arrested and convicted in sup

port of the racially discriminatory practice.

2. Whether petitioners were denied their rights to free

expression as protected by the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment:

(a) when convicted for engaging in a sit-in protest

demonstration,

(b) and when said convictions were under statutes

so vague as to give no fair warning that their conduct

was prohibited.

3

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

2. This case involves Section 16-386, Code of Laws of

South Carolina, 1952, as amended 1960:

16-386 Entry on lands of another after notice pro

hibiting same.

Every entry upon the lands of another where any

horse, mule, cow, hog or any other livestock is pastured,

or any other lands of another, after notice from the

owner or tenant prohibiting such entry, shall be a mis

demeanor and be punished by a fine not to exceed one

hundred dollars, or by imprisonment with hard labor

on the public works of the county for not exceeding

thirty days. When any owner or tenant of any lands

shall post a notice in four conspicuous places on the

borders of such land prohibiting entry thereon, a proof

of the posting shall be deemed and taken as notice

conclusive against the person making entry as afore

said for the purpose of trespassing.

3. This case involves Section 15-909, Code of Laws of

South Carolina, 1952:

15-909 Disorderly Conduct, etc.

The mayor or intendant and any alderman, council

man or warden of any city or town in this State may

in person arrest or may authorize and require any

marshall or constable especially appointed for that pur

pose to arrest any person who, within the corporate

limits of such city or town, may be engaged in a breach

of the peace, any riotous or disorderly conduct, open

obscenity, public drunkenness, or any other conduct

4

grossly indecent or dangerous to the citizens of such

city or town or any of them. Upon conviction before

the mayor or intendant or city or town council such

person may be committed to the guardhouse which, the

mayor or intendant or city or town council is authorized

to establish or to the county jail or to the county chain-

gang for a term not exceeding thirty days and if such

conviction be for disorderly conduct such person may

also be fined not exceeding one hundred dollars; pro

vided that this section shall not be construed to prevent

trial by jury.

Statement

Petitioners, five Negro students, were arrested for par

ticipating in a sit-in demonstration at the Taylor Street

Pharmacy in the City of Columbia, South Carolina, and

were convicted of trespass and breach of the peace in viola

tion of Section 16-386, as amended, and Section 15-909,

respectively, of the Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1952

(E. 1). They were sentenced to pay a fine of one hundred

dollars on each charge, or serve thirty days on each charge

(R. 1).

Petitioners, students at the nearby Benedict College,

entered the Taylor Street Pharmacy on March 15, 1960 in

the afternoon. They proceeded to the lunch counter in the

rear of the store, after some had made purchases in the

front portion, and seated themselves at the lunch counter

(R. 9, 39). The policy of the store was to serve Negroes

on the same basis as whites at all places in the store except

the lunch counter (R. 23). At the lunch counter Negroes

could secure food to be removed from the store, but were

not to sit at the counter and eat their purchases (R. 24).

There was a general sign that the manager reserved the

5

right to refuse service, but there was no sign specifically

barring use of the counter by Negroes (R. 25). The State

police had alerted the manager that a sit-down demonstra

tion would occur, and had detailed three policemen to the

store (R. 3, 25). As petitioners sat down some of the white

patrons at the counter stood up (R. 17). The manager came

to the counter and informed petitioners that they “might

as well leave” because they would not be served (R. 32).

Petitioners did not leave at this request (R. 32). Police

Officer Stokes then directed the manager to request again

that petitioners leave, which he did (R. 18). Shortly there

after the police officers arrested petitioners (R. 5). The

manager had left the luncheon area after his announcement

to the petitioners, and the police officers arrested petitioners

without a direct request from him (R. 19, 21). The co-owner

of the restaurant in addition to being informed by the

police of the coming demonstration, testified that: “We

[the police and himself] had a previous agreement to the

effect, that if they did not leave, they would be placed under

arrest for trespassing” (R. 29), and later:

“Q. Was it your idea to have these defendants ar

rested, or was it the idea of the police department?

A. I ’ll put it that it was the both of us’ idea, that if

they were requested to leave and failed to leave, that

they would be arrested” (R. 30).

The petitioners were well-dressed, orderly and did not

physically interfere with any other customers throughout

the whole of their request for service at the lunch counter

(R. 8, 27). The co-owner of the restaurant replied affirma

tively that there was no difference between the dress and

demeanor of the petitioners and other customers “other than

the color of their skin” (R. 27).

6

How the Federal Questions Were Raised

At the close of the trial in the Recorder’s Court of the

City of Columbia, petitioners moved to dismiss the charges

against them alleging: the evidence showed the arrests were

State enforcement of discrimination based solely on the

petitioners’ race and that petitioners were deprived of the

liberty of protesting segregation through requesting to be

served as others; all in violation of the due process and

equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the United States Constitution (R. 46-50), The motion was

denied (R. 50-52). Defendants also moved for arrest of

judgment, or in the alternative, for a new trial raising the

same issues as raised under the motion to dismiss (R. 54-

55). These motions were denied (R. 55).

After considering petitioners’ exceptions (R. 57), the

Richland County Court, on appeal held:

The State has not denied Defendants equal protec

tion of the laws or due process of law within the Fed

eral or State constitutional provisions.

And the proprietor can chase his customers without

violating constitutional provisions. State v. Clyburn,

101 S. E. (2d) 295, 247 N. C. 455; Williams v. Howard

Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F. (2d) 845; Slack v. At

lantic White Towers, etc., 181 F. Supp. 124 (Dist. Court

Md.) 284 F. (2d) 746” (R. 58).

In appealing to the Supreme Court of South Carolina,

petitioners set forth the following exceptions to the judg

ment below (R. 63-64).

Exceptions

3. The Court erred in refusing to hold that the evi

dence shows conclusively that the arresting officers

7

acted in the furtherance of a custom, practice and

policy of discrimination based solely on race or color,

and that the arrests and convictions of appellants under

such circumstances are a denial of due process of law

and the equal protection of the laws, secured to them

by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution.

4. The Court erred in refusing to hold that the evi

dence establishes merely that at the time of their

arrests appellants were peaceably upon the premises

of Taylor Street Pharmacy as customers, visitors,

business guests or invitees of a business establishment

performing economic functions invested with the pub

lic interest, and that the procurement of the arrest of

appellants by management of said establishment under

such circumstances in furtherance of a custom, prac

tice in and policy of racial discrimination is a violation

of rights secured appellants by the due process and

equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the United States Constitution.

The Supreme Court of South Carolina disposed adversely

of all of petitioners’ constitutional claims. After a summary

of the facts, the court stated:

The questions involved are stated in appellants’

brief as follows:

1. Did the Court err in refusing to hold that under

the circumstances of this case, the arrests and convic

tions of appellants were in furtherance of a custom

of racial segregation, in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution? (Ex

ceptions 3, 4.)

A. Was the enforcement of segregation in this case

by State Action within the meaning of the Four

teenth Amendment?

8

B. Were appellants unwarrantedly penalized for ex

ercising their freedom of expression in violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment?

The questions designated 1, A and B, must he de

cided adversely to appellants under City of Greenville

v. Peterson, filed November 10, 1961,----- - S. C. ----- ,

-----S. E. (2d)------, and City of Charleston v. Mitchell,

filed December 13,1961,-----S. C.------ , ----- 8. E. (2d)

----- . Each of these cases involved a sit-down demon

stration at a lunch counter in a privately owned place

of business and the precise questions raised by Excep

tions 3 and 4 in the instant case were raised in those

cases and overruled. In the City of Charleston case

we affirmed a conviction for violation of Section 16-386

as amended, which is the same section under which the

appellants were convicted.

REASONS FO R GRANTING THE W RIT

I.

T he D ecision Below Conflicts W ith P rio r D ecisions o f

This C ourt W hich C ondem n th e Use o f State Pow er to

E nfo rce a State Custom of R acial Segregation.

In this case it is clear that the petitioners were refused

service, ordered to leave the lunch counter, arrested and

convicted of crimes on the basis of their race pursuant to

and in the enforcement of a policy of racial discrimination.

It is undisputed that the practice of the Taylor Street

Pharmacy was to stand ready to serve food at its lunch

counter seats to white persons and to refuse such service

to all Negroes; that it was the policy to serve Negroes only

when they were taking the food elsewhere to eat; and that

petitioners were refused service solely because of their

race and for no other reason. It is also apparent that the

arrests were made to support this discrimination, and that

9

the trial court convicted petitioners on evidence plainly indi

cating that race, and race alone, was the reason they were

ordered to leave the lunch counter, and consequently ar

rested and charged upon their failure to leave. This is

thus a case where the difference in treatment to which peti

tioners have been subjected is clearly a racial discrimina

tion.

There are several dominant and relevant components of

action by state officials in the chain of events leading to

appellants’ conviction and punishment for violating the

racially discriminatory customs. The police alerted the co

owner of the store that an attempt to integrate the lunch

counters would occur on the day the petitioners frequented

the store (R. 3, 25). They had made an agreement with this

proprietor to secure the arrest of the petitioners and had

dispatched an extra detail of police to the premises prior

to petitioners’ arrival (R. 3, 25). Although one police offi

cer testified he was only on the scene to prevent violence

(R. 7) the co-owner testified that the prearranged plan with

the police was for the petitioners to be arrested if they

failed to conform to requests to leave the white lunch coun

ter (R. 30). It was the police officer who directed the man

ager to give the final request to the petitioners to leave

(R. 18). Here, as in all criminal prosecutions, there is fur

ther state action by state officers in the persons of the

prosecutors and judges; the official actions of such officers

are “state action” within the meaning of the Fourteenth

Amendment under clear authorities. The subject of judicial

action as “state action” was treated exhaustively in part II

of Chief Justice Vinson’s opinion in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U. S. 1, 14-18; cf. Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454.

Policemen (Screws v. United States, 325 IT. S. 91; Monroe

v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167) and prosecutors (Napue v. Illinois,

360 U. S. 264) are equally subject to the restraints of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

10

Ever since the Civil Bights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 17, it has

been conventional doctrine that racial discrimination when

supported by state authority, violates the Fourteenth

Amendment’s equal protection clause; and since Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, it has been settled that

racial segregation constitutes a forbidden discrimination.

However, in this case the involvement of the public law

enforcement and judicial officers in the racial discrimination

practiced against petitioners through their use of the state’s

criminal law machinery to support and enforce it, is now

sought to be excused because, it is said, there is also “pri

vate action” in the picture, and the state is said to be merely

enforcing “private property” rights through its criminal

trespass and breach of the peace laws. It is argued that

the state is not really excluding and punishing Negroes,

but only “trespassers” inciting a breach of the peace, and

that the state stands ready to punish whites in these cir

cumstances as well. While petitioners are aware of no

case of a white person convicted for refusing to leave an

all-Negro establishment under a trespass or breach of the

peace law,1 there is no reason to doubt that this might occur

in communities deeply wedded to the segregation customs.

The answer made to a parallel argument in Shelley v.

Kraemer, 334 U. 8. 1, 22, is apt—“Equal protection of the

laws is not achieved through indiscriminate imposition of

inequalities.”

But the argument that it is only trespassers inciting a

breach of peace and not Negroes qua Negroes who are

punished by the State, and thus it is private property rights

and order and not racial discrimination that is being pre

served by the state’s officers and laws, requires further anal-

1 White persons have been convicted for trespass when in com

pany with Negroes in “white only” establishments. Avent v. North

Carolina, No. 85, October Term 1961.

11

ysis. We shall examine in turn, the specific nature of the

property right and the state’s legitimate interests includ

ing protection of the right to privacy and general tran

quility, and their relation to state customs and laws.

As a starting point it is fit to observe, as this Court did

in Shelley v. Kraemer, supra, that the mere fact that prop

erty rights are involved does not settle the matter. The

Court said at 334 U. S. 1, 22:

“Nor do we find merit in the suggestion that prop

erty owners who are parties to these agreements are

denied equal protection of the laws if denied access to

the courts to enforce the terms of restrictive covenants

and to assert property rights which the state courts

have held to be created by such agreements. The

Constitution confers upon no individual the right to

demand action by the State which results in the denial

of equal protection of the laws to other individuals.

And it would appear beyond question that the power of

the State to create and enforce property interests must

be exercised within the boundaries defined by the

Fourteenth Amendment. Cf. Marsh v. Alabama, 326

U. S. 501, 90 L. ed. 265, 66 S. Ct. 276 (1946).”

This Court has said on several occasions, “that dominion

over property springing from ownership is not absolute and

unqualified.” Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 74; United

States v. Willow River Power Co., 324 IT. S. 499, 510; Marsh

v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501, 506; cf. Munn v. Illinois, 94 U. S.

113. As the Court said in Marsh, supra, “The more an

owner, for his advantage, opens up his property for use

by the public in general, the more do his rights become

circumscribed by the statutory and constitutional rights of

those who use it. Cf. Republic Aviation Corp. v. N. L. R. B.,

324 U. S. 793, 796, 802.”

12

Because it does matter a great deal what kind of property

interest is being created and enforced by the State in given

circumstances, we must inquire: What is the nature of the

property right of the Taylor Street Pharmacy which is

being enforced by the state in the criminal trespass charge?

The Taylor Street Pharmacy used the premises involved

in its commercial business as a drug store opened to the

public generally for the transaction of business including

the sale of food and beverages at its lunch counter. This

case does not involve enforcement of a general desire to

keep everyone, or Negroes, or even these petitioners, from

coming upon the premises. The white public was invited to

use all the facilities of the drug store, and the Negro public

was invited to use all facilities except the lunch counter

stools. Negroes were even welcomed to purchase food at

the lunch counter provided they stood up to purchase it

and left the store to eat. The property interests enforced

for the Taylor Street Pharmacy do not involve the integrity

of a portion of its premises set aside for non-public use,

such as space reserved for the owner or its employees. Nor

does the property interest enforced here relate to an owner’s

claim that a portion of its premises is being sought to be

used for a purpose alien to its normal or intended function.

Petitioners merely sought to use a lunch counter stool while

consuming food sought to be purchased on the premises, the

purpose for which the stools were being maintained. The

state is not being called upon here to enforce a property

owner’s general desire not to sell its goods to Negroes, since

food and beverages were offered for sale to Negroes at

this counter if they remained standing and took their pur

chases away with them. And further the proprietor himself,

by opening every other department of his store to Negroes

on the same basis as whites, has in the most affirmative

manner possible stated that the mere fact of the purchaser’s

race is not disruptive of any operating business.

13

The property interest which is being enforced here is a

claimed right to open premises to the public generally (in

cluding Negroes) for business purposes, including the sale

of food and beverages, while racially discriminating against

Negroes qua Negroes at one of the facilities for the public

in the business premises—including a claimed right to have

Negroes arrested and criminally punished for failing to

obey the owner’s direction for them to leave this portion of

the store. This claimed property right—the right to racially

discriminate against Negroes with respect to being seated

in the circumstances indicated—is indeed a type of property

interest. The question remains whether the States’ laws

can give recognition and enforcement to such an interest

without violating the Fourteenth Amendment.

Petitioners submit that it is readily apparent that the

property interest being enforced against them on behalf of

the Taylor Street Pharmacy, bears no substantial relation

to any constitutionally protected interest of the property

owner in privacy in the use of his premises. The State is

not in this prosecution engaged in protecting the right to

privacy. It has long been agreed by the courts that a state

can “take away” this property right to racially segregate in

public accommodation facilities without depriving an owner

of Fourteenth Amendment rights. Western Turf Asso. v.

Greenberg, 204 U. S. 359; Railway Mail Ass’n v. Corsi, 326

IT. S. 88; Pickett v. Kuchan, 323 111. 138, 153 N. E. 667, 49

A. L. R. 499 (1926); People v. King, 110 N. Y. 418, 18 N. E.

245 (1888); Annotation 49 A. L. R. 505; cf. District of

Columbia v. John R. Thompson Co., 346 IT. S. 100.

And indeed a great number of states in our Nation have

enacted laws making it criminal to engage in just the type

of racially discriminatory use of piivate property which

the Drug Company seeks state assistance in preserving

14

here.2 From the fact that the States can make the attempted

exercise of such a “right” a crime, it does not follow neces

sarily and automatically that they must do so, and must

refuse (as petitioners here urge) to recognize such a

claimed property right to discriminate racially in places

of public accommodation. But the fact that the States

can constitutionally prohibit such a use of property and

that when they do so they are actually conforming to the

egalitarian principles of the Fourteenth Amendment {Rail

way Mail Ass’n v. Corsi, supra, at 93-94) makes it evident

that the property interest asserted by the Taylor Street

Pharmacy is very far from an inalienable or “absolute”

property right. Indeed the property owner here is at

tempting to do something that the state itself could not

permit him to do on state property leased to him for his

business use (Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority,

365 IT. S. 175), or require or authorize him to do by positive

legislation (cf. Mr. Justice Stewart’s concurring opinion in

Burton, supra).

A basic consideration in this case is that the pharmacy

lunch counter involved is a public establishment in the

sense that it is open to serve the public and is part of the

public life of the community (Mr. Justice Douglas, con

curring in Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 176). As a

consequence of the public use to which the property has

been devoted by the owner, this case involves no real claim

that the right to privacy is being protected by this use of

the State’s trespass lawrs. And, of course, it does not follow

from the conclusion that the State cannot enforce the racial

bias of the operator of a lunch counter open to the public,

that it could not enforce a similar bias by the use of tres

pass laws against an intruder into a private dwelling or any

2 See collections of such laws in Konvitz, A Century of Civil

Bights, Passim (1961).

15

other property in circumstances where the state was exer

cising its powers to protect an owner’s privacy. This Court

has recently reiterated the principle that there is a con

stitutional “right to privacy” protected by the Due Process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, Mapp v. Ohio, 367

II. S. 643, 6 L. ed. 2d 1081, 1090, 1103, 1104; see also Poe

v. Ullman, 367 U. S. 497, 6 L. ed. 2d 989, 1106, 1022-1026

(dissenting opinions). It is submitted that due considera

tion of the right to privacy affords a sound and rational

basis for determining whether cases which might arise in

the future involving varying situations should be decided

in the same manner urged by petitioner here-—that is,

against the claimed property interest. Only a very ab

solutist view of the property “right” to determine those

who may come or stay on one’s property on racial grounds

—an absolutist rule yielding to no competing considera

tions—would require that the same principles apply through

the whole range of property uses, public connections,

dedications, and privacy interests at stake. The Court

has recognized the relation between the right of privacy

and property interests in the past. See e.g. Thornhill v.

Alabama, 310 U. S. 88, 105-106; Breard v. Alexandria, 341

U. S. 622, 626, 638, 644.

Petitioners submit that a property right to determine on

a racial basis who can stay on one’s property cannot be

absolute at all, for this claimed right collides at some

points with the Fourteenth Amendment right of persons

not to be subjected to racial discrimination at the hand

of the government. Burton v. Wilmington Parking Author

ity, supra; Shelley v. Kraemer, supra. Mr. Justice Holmes

said in Hudson County Water Co. v. McCarter, 209 U. S.

349, 355.

All rights tend to declare themselves absolute to their

logical extreme. Yet all in fact are limited by the

16

neighborhood of principles of policy which are other

than those on which the particular right is founded,

and which become strong enough to hold their own

when a certain point is reached.

Petitioners certainly do not contend that the principles

urged to prevent the use of trespass laws to enforce racial

discrimination in a lunch counter operated as a public busi

ness would prevent the state from enforcing a similar bias

in a private home where the right of privacy has its

greatest meaning and strength. A man ought to have the

right to order from his home anybody he prefers not to

have in it, and ought to have the help of the government

in making his order effective. Indeed, the State cannot

constitutionally authorize an intrusion into a private home

except in the most limited circumstances with appropriate

safeguards against abuses. Mapp v. Ohio, supra; cf. Frank

v. Maryland, 359 U. S. 360. Racial discrimination in a

private home, or office, or other property where the right

of privacy is paramount is one thing. Racial discrimina

tion at a public counter is quite another thing indeed.

The involvement of the State of South Carolina as a

whole entity in the present discrimination is so intimate

and manifold that the state action standard may be satis

fied or bolstered by other criteria than the participation

of its police and courts in enforcing the discriminatory

result complained of by petitioners. For racial discrimina

tion has deep roots in South Carolina custom and law.

“Custom” is specifically included in the opinion in the

Civil Rights Cases as one of the forms of “state authority”

which might be used in efforts to support a denial of Four

teenth Amendment rights (109 U. S. 3, at 17). See also

Mr. Justice Douglas concurring in Garner v. Louisiana,

368 U. S. 157,176.

17

The Taylor Street Pharmacy in excluding Negroes from

its lunch counter was following a custom of segregating

Negroes in public life which is characteristic of South

Carolina as a community, and which custom has been firmed

up and supported by the segregation policies and laws of

South Carolina as a policy.3

The segregation laws form an edifice created by law—

the systematic segregation of Negroes in public life in

South Carolina. There is good ground for belief that the

segregation system, of which the custom enforced by the

Taylor Street Pharmacy is a part, was brought into being

or at least given firm contour in its beginning, by State

laws.

As Mr. Justice Douglas wrote recently concurring in

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157,181:

“Though there may have been no state law of municipal

ordinance that in terms required segregation of the

races in restaurants, it is plain that the proprietors

in the instant cases were segregating blacks from whites

pursuant to Louisiana’s custom. Segregation is basic

3 S. C. A. & J. R, 1952 (47) 2223, A. & J. R. 1954 (48) 1695

repealing S. C. Const. Art. II, §5 (1895) (which required legis

lature to maintain free public schools). S. C. Code §§21-761 to

779 (regular school attendance) repealed by A. & J. R. 1955 (49)

85; §21-2 (appropriations cut off to any school from which or to

which any pupil transferred because of court order; §21-230(7)

(local trustees may or may not operate schools); §21-238 (1957

Supp.) (school officials may sell or lease school property whenever

they deem it expedient); S. C. Code §40-452 (1952) (unlawful

for cotton textile manufacturer to permit different races to work

together in same room, use same exits, bathrooms, etc., $100 penalty

and/or imprisonment at hard labor up to 30 days; S. C. A. & J. R.

1956 No. 917 (closing park involved in desegregation suit) ; S. C.

Code No. §§51-1, 2.1-2.4 (1957 Supp.) (providing for separate

State Parks) §51-181 (separate recreational facilities in cities with

population in excess of 60,000) ; §5-19 (separate entrances at

circus) ; S. C. Code Ann. Tit. 58, §§714-720 (1952) (segregation

in travel facilities).

18

to the structure of Louisiana as a community; the

custom that maintains it is at least as powerful as

any law. If these proprietors also choose segregation,

their preference does not make the action ‘private’,

rather than ‘state’ action. If it did, a minuscule of

private prejudice would convert state into private ac

tion. Moreover, where the segregation policy is the

policy of a state, it matters not that the agency to

enforce it is a private enterprise. Baldwin v. Morgan,

supra; Boman v. Birmingham Transit Go., 280 F. 2d

531.”

Finally the property involved in this case is “affected

with a public interest,” Munn v. Illinois, 94 U. S. 113.

By its use it has become “clothed with a public interest . . .

[is] of public consequence, and affect[s] the community at

large” (Id. at 126). This property is operated as a lunch

counter under a license granted by the City of Columbia

(R. 23). The licensing by the state demonstrates the pub

lic’s interest in the business and the governmental recog

nition of this public character. As Mr. Justice Douglas

stated concurring in Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157,

184: “A license to establish a restaurant is a license to

establish a public facility and necessarily imports, in law,

equality of use for all members of the public.”

The charge of breach of the peace has the same posture

as that of trespass and is even more simply a direct instance

of state power being utilized to enforce segregation. There

was absolutely no evidence of violence or threats of violence

by petitioners directed toward anyone. The only testimony

remotely resembling a disturbance of the peace was to

the effect that some whites “stood up” when petitioners

sat down; any inference of threatened violence by these

persons would therefore stand on a weak reed. But even if

the record contained a showing that these whites were about

19

to unlawfully attack petitioners, the prohibition of state

enforcement of segregation under the Fourteenth Amend

ment is of course a rejection of all the reasons why segrega

tion might be thought good, including fear of disorder.

Buchanan v. Warley, supra; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1.

It is submitted that the totality of circumstances in

this case, including the actions of the State’s officers in

arranging the arrests and prosecuting petitioners, the

municipal licensing of the property involved and the con

sequent public character of the business property involved,

the plain and invidious racial discrimination involved in

the asserted property rights being protected by the state,

the absence of any relevant component of privacy to be

protected by the state’s action in light of the nature of

the owner’s use of his property, and the state custom of

segregation which has created or at least substantially

buttressed the type of discriminatory practices involved,

are sufficient to require a determination that the petitioners’

trespass and breach of the peace convictions have abridged

their rights under the Fourteenth Amendment,

II.

T he D ecision Below Conflicts W ith Decisions o f This

C ourt Securing the R ight o f F reedom of E xpression

U nder th e F o u rteen th A m endm ent to the C onstitution

o f the U nited States.

Petitioners were engaged in the exercise of free expres

sion by means of nonverbal requests for nondiscriminatory

lunch counter service which were implicit in their continued

remaining at the lunch counter when refused service. The

fact that sit-in demonstrations are a form of protest and

expression was observed in Mr. Justice Harlan’s con

currence in Garner v. Louisiana, supra. Petitioners’ ex

pression (asking for service) was entirely appropriate to

20

the time and place at which it occurred. Petitioners did not

shout, obstruct the conduct of business, or engage in any

expression which had that effect. There were no speeches,

picket signs, handbills or other forms of expression in the

store which were possibly inappropriate to the time and

place. Rather petitioners merely expressed themselves by

offering to make purchases in a place and at a time set

aside for such transactions. Their protest demonstration

was a part of the “free trade in ideas” (Abrams v. United

States, 250 U. S. 616, 630, Holmes, J dissenting), and was

within the range of liberties protected by the Fourteenth

Amendment, even though nonverbal. Stromberg v. Cali

fornia, 283 U. S. 359 (display of red flag); Thornhill v.

Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 (picketing); West Virginia State

Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U. S. 624, 633-624

(flag salute); N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449

(freedom of association).

Petitioners do not urge that there is a Fourteenth Amend

ment right to free expression on private property to all

cases or circumstances without regard to the owner’s

privacy, and his use and arrangement of his property.

This is obviously not the law. In Breard v. Alexandria,

341 U. S. 622 the Court balanced the “householder’s desire

for privacy and the publisher’s right to distribute publica

tions” in the particular manner involved, and upheld a law

limiting the publisher’s right to solicit on a door-to-door

basis. But cf. Martin v. Struthers, 319 U. S. 141 where

different kinds of interests were involved with a cor

responding difference in result.

As was true with the discussion above of the racial dis

crimination issue, so the free expression issue is not re

solved merely by reference to the fact that private property

rights are involved. The nature of the property rights

asserted and of the state’s participation through its of-

21

fleers, its customs, and its creation of the property interest,

have all been discussed above in connection with the state

action issue as it related to racial discrimination. Similar

considerations should aid in resolving the free expression

question.

In Garner v. Louisiana, Mr. Justice Harlan, concurring,

found a protected area of free expression on private prop

erty on facts regarded as involving “the implied consent

of the management” for the sit-in demonstrators to remain

on the property. It is submitted that even absent the

owner’s consent for petitioners to remain on the premises

of this pharmacy, a determination of their free expression

rights requires consideration of the totality of circum

stances respecting the owner’s use of the property and the

specific interest which state judicial action is supporting.

Marsh v. Alabama, supra.

In Marsh, supra, this Court reversed trespass convictions

of Jehovah’s Witnesses who went upon the. privately owned

streets of a company town to proselytize for their faith,

holding that the conviction violated the Fourteenth Amend

ment. In Republic Aviation Corp. v. N. L. R. B., 324 U. S.

793, the Court upheld a labor board ruling that lacking

special circumstances employer regulations forbidding all

union solicitation on company property constituted unfair

labor practices. See Thornhill v. Alabama, supra, involving

picketing on company-owned property; see also N. L. R. B.

v. American Pearl Button Co., 149 F. 2d 258 (8th Cir.

1945); and compare the cases mentioned above with N. L.

R. B. v. Fansteel Metal Corp., 306 U. S. 240, 252, condemn

ing an employee seizure of a plant. In People v. Barisi, 193

Misc. 934, 83 N. Y. S. 2d 277, 279 (1948) the Court held that

picketing within Pennsylvania Railroad Station was not a

22

trespass; the owners opened it to the public and their

property rights were “circumscribed by the constitutional

rights of those who use it.” See also Freeman v. Retail

Clerks Union, Washington Superior Court, 45 Lab. Eel.

Ref. Man. 2334 (1959); and State of Maryland v. Williams,

Baltimore City Court, 44 Lab. Eel. Eef. Man. 2357, 2361

(1959).

In the circumstances of this case the only apparent state

interest being subserved by this trespass prosecution, is

support of the property owner’s discrimination in con

formity to the State’s segregation custom and policy. This

is all that the property owner has sought.

Where free expression rights are involved, the questions

for decision is whether the relevant expressions are “in

such circumstances and . . . of such a nature as to create a

clear and present danger that will bring about the substan

tive evil” which the state has the right to prevent. Schenck

v. United States, 249 U. S. 47, 52. The only “substantive

evil” sought to be prevented by this trespass prosecution

is the elimination of racial discrimination and the stifling

of protest against it; but this is not an “evil” within the

State’s power to suppress because the Fourteenth Amend

ment prohibits state support of racial discrimination.

The fact that the arrest and conviction were designed to

short circuit a bona fide protest is strengthened by the

necessity of the state court to make a strained and novel

interpretation of the statutes in order to bring petitioners’

conduct within their ambit. Petitioners’ conviction for tres

pass rests on an interpretation which flies in the face of the

plain words of the statute, all prior applications, and ig

nores the most recent legislative amendment to said statute.

The trespass statute prior to amendment read:

23

Every entry upon the lands of another after notice

from the owner or tenant prohibiting such entry shall

be a misdemeanor and be punished by a fine not to

exceed one hundred dollars or by imprisonment with

hard labor on the public works of the county for not

exceeding thirty days. When any owner or tenant

of any lands shall post a notice in four conspicuous

places on the borders of such land prohibiting entry

thereon and shall publish once a week for four con

secutive weeks such notice in any newspaper circulating

in the county in which such lands are situated, a proof

of the posting and of publishing of such notice within

twelve months prior to entry shall be deemed and taken

as notice conclusive against the person making entry

as aforesaid for the purpose of hunting or fishing on

such land. (Code of Laws, South Carolina, 1952.)

The amended statute under which petitioners’ convictions

were had added the language which is italicized:

Every entry upon the lands of another where any

horse, mule, cow, hog or any other livestock is pastured,

or any other lands of another . . .

The Legislature obviously limited the statute to trespass

on land primarily used for farm purposes nor was this a

major innovation, for petitioners have been able to find

no cases under the instant criminal statute or its predeces

sors in which the trespass punished was not for entry on

land (generally farm land) or some adjunctive land such

as on the road. See State v. Green, 35 S. C. 266; State v.

Mays, 24 S. C. 190; State v. Tenney, 58 S. C. 215; State v.

Hallback, 40 S. C. 298; State v. Gray, 76 S. C. 83 (all cases

of trespass on land or specifically farm land). The amend

ment was merely declaratory, making explicit on the face

of the statute the prior applications. The action of the court

24

below in extending the statute to business premises is, there

fore, completely novel and unsupported by prior cases or

the recent amendment.

Further, the statute in terms prohibits only going on the

land of another after being forbidden to do so. The Su

preme Court of South Carolina has now construed the stat

ute to prohibit also remaining on property when directed

to leave the following lawful entry. In short, the statute

is now applied as if “remain” were substituted for

“enter.” There is no history to support this second novel

construction of the statute. No South Carolina case has

ever adopted such a construction. The instant case is

the first case which directly or indirectly convicts defen

dants who went upon business premises with permission

and merely refused to leave when directed for unlawful

“entry.”

Subsequent to petitioners’ conviction the legislature of

the State of South Carolina enacted into law Section 16-388

a trespass statute making criminal failing and refusing “to

leave immediately upon being ordered or requested to do

so” the premises or place of business of another. See Peti

tion for Writ of Certiorari in Peterson, et al, v. City of

Greenville, filed in this Court February 26, 1962, 30 U. S. L.

Week 3276.

There is no question but that petitioners and all Negroes

were welcome within the Taylor Street Pharmacy—apart

from the lunch counter stools. The lunch counter is an

integral part of the store and can only be reached by “entry”

into the store proper—to which petitioners were admittedly

invited. Absent the special expansive interpretation given

Section 16-386 by the Supreme Court of South Carolina

the case would plainly fall within the principle of Thompson

v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199, and would be a denial

25

of due process of law as a conviction resting upon no evi

dence of guilt. There was obviously no evidence that peti

tioners entered upon land of a farmlike character “after

having been forbidden to do so” and the conclusion that

they did rests solely upon the special construction of the

law.

The escape from invalidity of the conviction for lack of

evidence of guilt via a construction completely unpredict

able by the words of the statute or any prior applications

renders the statue vague as being without sufficient prior

definition of the acts prohibited. Under the novel interpre

tation conduct is reached which the words of the statute do

not fairly and effectively proscribe, thus depriving peti

tioners of any notice that their acts would subject them

to criminal liability.

The vice of vagueness is particularly odious where the

right of free speech is put in jeopardy. Conduct involving

free speech can only be prohibited within a statute “nar

rowly drawn to define and punish specific conduct as con

stitute a clear and present danger to a substantial interest

of the state.” Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, 307,

308; Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 185 (Mr. Justice

Harlan concurring). If the Supreme Court of South Caro

lina can affirm the convictions of these petitioners by such

a construction they have exacted obedience to a rule or

standard that is so ambiguous and fluid as to be no rule

or standard at all. Champlin Ref. Co. v. Corporation Com.

of Oklahoma, 286 U. S. 210. Such a result cannot but have

a “potentially inhibiting effect on speech.” Smith v. Cali

fornia, 361 U. S. 205, 210. But when free expression is

involved, the standard of precision is greater; the scope

of construction must, therefore, be consequently less. If

this is the case when a State court limits a statute it must

a fortiori be the case when a State court expands the mean-

26

ing of the plain language of a statute. Winters v. New York,

333 U. S. 507, 512.

The above threat to free speech is also present under the

conviction for breach of the peace. Even under a strained

inference that the standing up of the whites was a threat

to attack the petitioners, such an attack would be com

pletely unlawful. Yet, the imminence of such an attack

by others is the sum and substance of the charge of breach

of the peace against petitioners. Again, petitioners were

not effectively warned by the statute that they were par

ticipating in criminal conduct solely by being present to

protest racial segregation where others might do unlawful

violence on their persons. Free speech was similarly denied

by conviction under the breach of the peace statute which

in no wise definitively prohibited petitioners’ conduct.

CONCLUSION

W herefore, fo r th e fo reg o in g reaso n s , i t is re sp ec tfu lly

su b m itted th a t th e p e titio n fo r a w r i t of c e r t io ra r i should

be g ra n te d .

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

L eroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

M atthew J . P erry

L incoln C. J e n k in s , J r.

1107y2 Washington Street

Columbia 1, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

I n th e

RICHLAND COUNTY COURT

City of Columbia,

— Y,—

Respondent,

B abb, et al.,

Appellants.

O rd er o f th e R ichland County Court

These Appeals from the Recorder’s Court of The City of

Columbia were orally argued together before me and taken

under advisement. The facts are largely undisputed. All

of the Defendants are Negroes. Eckerd’s Drug Store and

Taylor Street Pharmacy are separate stores in The City

of Columbia. Besides filling prescriptions, each sell drugs

and sundries and has a section where lunch, light snacks

and soft drinks are served. Trade is with the general public

in all the departments except the lunch department where

only white people are served.

On one occasion, Bouie and Neal went into Eckerd’s and

on another day the other Defendants went into the Taylor

Street Pharmacy, sat down in the lunch department and

waited to be served. All said they intended to be arrested.

In each case, the manager of the store came up to them with

a peace officer and asked them to leave. They refused to do

so and were then placed under arrest and charged with

trespass and breach of the peace. Bouie, in addition, was

charged with resisting arrest. It is undenied that he re

sisted.

2a

Order of the Richland County Court

Bouie and Neal were tried on March 25, 1960, and the

other Defendants on March 30, 1960, before The Honorable

John I. Rice, City Recorder of Columbia, without a jury;

trial by jury having been waived by all the Defendants.

All the Defendants were convicted and sentenced and

these appeals followed. Motions raising the constitutional

questions were timely made. ,

There are 16 grounds of Appeals in the Bouie and Neal

proceeding and 13 grounds of appeal in the proceeding

involving the other Defendants, raising the following ques

tions: (1) Did the State deny Defendants, who are Negroes,

due process of law and equal protection of the laws within

the Federal and State Constitutions either by using its

peace officers to arrest them or by charging them with vio

lating Sects. 16-386 (Criminal Trespass) and 15-909 (Breach

of Peace) of the Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1952, as

amended, when they refused to leave a lunch counter when

asked by the manager thereof to do so? (Bouie and Neal

Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15; other Defen

dants, Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13.) (2) Was

there any substantial evidence pointing to the guilt of the

Defendants? (Bouie and Neal, No. 8; other Defendants,

No. 7.)

Since Defendants did not argue Bouie and Neal’s Excep

tions 7, 9 and 16, I have considered them abandoned.

The State has not denied Defendants equal protection of

the laws or due process of law within the Federal or State

Constitutional provisions.

A lunch room is like a restaurant and not like an inn.

The difference between a restaurant and an inn is ex

plained in Alpauyh v. Wolverton, 36 S. E. (2d) 907 (Court

of Appeals of Virginia) as follows:

3a

Order of the Richland County Court

“The proprietor of a restaurant is not subject to the

same duties and responsibilities as those of an inn

keeper, nor is he entitled to the privileges of the latter.

28 A. Jr., Innkeepers, No. 120, p. 623; 43 C. J. S., Inn

keepers, No. 20, subsection b, p. 1169. His responsi

bilities and rights are more like those of a shopkeeper.

Davidson v. Chinese Republic Restaurant Co., 201 Mich.

389, 167 N. W. 967, 969, L. R. A. 1919 E, 704. He is

under no common-law duty to serve anyone who applies

to him. In the absence of statute, he may accept some

customers and reject others on purely personal

grounds. Nance v. Mayflower Tavern, Inc., 106 Utah

517, 150 P. (2d) 773, 776; Noble v. Higgins, 95 Misc.

328, 158 N. Y. S. 867, 868.”

And the proprietor can choose his customers on the basis

of color without violating constitutional provisions. State

v. Clyburn, 101 S. E. (2d) 295, 247 N. C. 455; Williams v.

Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 P. (2d) 845; Slack v.

Atlantic Whitetower, etc., 181 F. Sup. 124 (Dist. Court

Md.), 284 P. (2d) 746.

In the Williams case, supra, Judge Soper, speaking for

the Court of Appeals for The Fourth Circuit, said: “As an

instrument of local commerce, the restaurant is not subject

to the Constitution and statutory provisions above (Com

merce Clause and Civil Rights Acts of 1875), and is at lib

erty to deal with such persons as it may select.”

And in Boynton v. Virginia, ...... U. S......... , 81 S. Ct.

182, 5 L. Ed. (2d) 206, The Supreme Court of The United

States took care to state:

“Because of some of the arguments made here it is

necessary to say a word about what we are not deciding.

We are not holding that every time a bus stops at a

4a

Order of the Richland County Court

wholly independent roadside restaurant the Interstate

Commerce Act requires that restaurant service be sup

plied in harmony with the provisions of that Act. We

decide only this case, on its facts, where circumstances

show that the terminal and restaurant operate as an

integral part of the bus carrier’s transportation service

for interstate passengers.”

I have reviewed all of the cases cited by both the City

and the Defendants, and in addition have reviewed subse

quent cases of the Court of Appeals and The United States

Supreme Court, including the case of Burton v. Wilming

ton Parking Authority, handed down on April 17, 1961, and

find none applicable or controlling except the Williams and

Slack cases, supra.

The Defendants, under South Carolina law, had no right

to remain in the stores after the manager asked them to

leave. Shramek v. Walker, 149 S. E. 331, 152 S. C. 88. As

the Court quoted the rule, “while the entry by one person

on the premises of another may be lawful, by reason of

express or implied invitation to enter, his failure to depart,

on the request of the owner, will make him a trespasser,

and justify the owner in using reasonable force to eject

him.”

If the manager could have ejected Defendants himself,

he could call upon officers of the law to eject them for him.

Since the Defendants refused to leave, they were criminal

trespassers under Sect. 16-386 and breached the peace under

Sect. 15-909 of The Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1952,

and their conviction was proper.

Shelly v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 92 L. Ed. 845, 68 S. Ct.

836, 3 A. L. R. (2d) 441, and Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S.

249, 97 L. Ed. 1586, 73 Supreme Court 1031 cited by the

5a

Order of the Richland County Court

Defendants are not in point. In both of these eases, there

had been a sale of real estate to a non-eaucasian in violation

of restrictive covenants. In the Shelly case, the Court held

that the equity of court of the State could not be used

against the non-caucasian to enforce the covenant. In the

Barrows case, the court held that the covenant could not be

enforced by an action at law for damages against the co

covenanter, who broke the covenant.

In both of these cases, there were willing sellers and will

ing purchasers. The purchasers paid their money and en

tered into possession. Having entered, they had a right to

remain.

In the cases before the Court, there were no two willing

parties to a contract. True, the Defendants wanted to buy,

but the storekeeper did not want to sell and the Defendants

had no right to remain after being asked to leave. A white

person would not have the right to remain after being

asked to leave either. In either case, a person would be a

trespasser. The Constitutions provide for equal rights, not

paramount rights.

I have only to pick up my current telephone directory and

look in the yellow pages to find at least four establishments

listed under “Restaurants” that advertise that they are for

colored or for colored only.

To say that a white proprietor may not call upon a police

man to remove or arrest a Negro trespasser or a Negro pro

prietor cannot call upon a policeman to remove or arrest a

white trespasser would lead to confusion, lawlessness and

possible anarchy. Certainly, the Constitutions intended no

such result.

The fundamental fallacy in the argument of Defendants

is the classification of the stores and lunch counters as public

places and the operations thereof as public carriers.

6a

Order of the Richland County Court

A person, whatever his color, enters a public place or

carrier as a matter of right. The same person, whatever his

color, enters a store or restaurant or lunch counter by

invitation.

That person’s right to remain in a public place depends

upon the law of the land, and in a public carrier upon such

law and such reasonable rules as the carrier may make, and,

under the Constitution, neither the law nor rules may dis

criminate upon the basis of color.

On the other hand, the same person has no right to enter

a store, a restaurant, or lunch counter unless and until

invited, and may remain only so long as the invitation is

extended. Whether he enters or remains depends solely

upon the invitation of the storekeeper, who has a full choice

in the matter. The operator can trade with whom he wills,

or he can, at his own whim and pleasure, close up shop.

There is no question but that the Defendants are guilty.

They were asked to leave and they refused. They, there

upon, were trespassers and such constituted a breach of the

peace. In addition, Bouie admittedly resisted a lawful

arrest.

The trespass statute (Section 16-386, as amended, Code

of Laws of South Carolina, 1952) is not restricted to “pas

ture or open hunting lands” as Defendants argue. The

statute specifically says “any other lands”. In Webster’s

New International Dictionary, the definition of “land” in

“Law” is as follows:

“ (a) any ground, soil, or earth whatsoever, regarded as

the subject of ownership, as meadows, pastures, woods,

etc., and everything annexed to it, whether by nature,

as trees, water, etc., or by man, as buildings, fences,

etc., extending indefinitely vertically upwards and

downwards, (b) An interest or estate in land; loosely

any tenement or hereditament.”

7a

Order of the Richland County Court

The statute thus applies everywhere and without dis

crimination as to color. There is no question but that it was

designed to keep peace and order in the community.

Since Defendants had notice that neither store would

serve Negroes at their lunch counters, they were trespassers

ab initio. Aside from this however, the law is that even

though a person enter property of another by invitation, he

becomes a trespasser after he has been asked to leave.

Shramek v. Walker, supra.

For the reasons herein stated, I am of the opinion that

the judgments and sentences of the Recorder should be sus

tained and the Appeals dismissed, and it is so ordered.

s / J o h n W . C b e w s ,

Judge, Richland County Court.

Columbia, S. C.,

April 28, 1961.

8a

O pin ion o f S uprem e C ourt o f South C arolina

THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA

I n t h e S u p r e m e C o u r t

T h e C i t y o p C o l u m b i a ,

— v .—

Respondent,

C h a r l e s F. B a r r , R ic h a r d M . C o u n t s , D a v id C a r t e r ,

M i l t o n D. G r e e n e a n d J o h n n y C l a r k ,

Appellants.

Appeal From Richland County

John W. Crews, County Judge

Case No. 4777

Opinion No. 17857

Filed December 14,1961

O x n e r , A. J . : The five appellants, all Negroes, were

convicted in the Municipal Court of the City of Columbia

of trespass in violation of Section 16-386 of the 1952 Code,

as amended, and of breach of the peace in violation of

Section 15-909. Each defendant was sentenced to pay a fine

of $100.00 or serve a period of thirty days in jail on each

charge but $24.50 of the fine was suspended. From an order

of the Richland County Court affirming their conviction,

they have appealed.

The exceptions can better be understood after a review

of the testimony. The charges grew out of a “sit-down”

demonstration staged by appellants at the lunch counter

9a

Opinion of Supreme Court of South Carolina

of the Taylor Street Pharmacy in the City of Columbia,

a privately owned business. In addition to selling articles

usually sold in drugstores, this establishment maintains a

lunch counter in the rear, separated from the front of the

store by a partition. The customers sit on stools. The

policy of this store is not to serve Negroes at the lunch

counter although they are permitted to purchase food and

eat it elsewhere. In a sign posted the privilege of refusing

service to any customer was reserved.

Shortly after noon on March 15, 1960, appellants, then

college students, according to a prearranged plan, entered

this drugstore, proceeded to the rear and sat down at the

lunch counter. The management had heard of the proposed

demonstration and had notified the officers. To prevent

violence, three were present when appellants entered. As

soon as they took their seats several of the customers at

the counter, including a White woman nest to whom one

of appellants sat, stood up. The manager of the store then

came back to the lunch counter. He testified that the situa

tion was quite tense, that you “could have heard a pin drop

in there”, and that “everyone was on pins and needles,

more or less, for fear that it could possibly lead to violence.”

He immediately told appellants that they would not be

served and requested them to leave. They said nothing and

continued to sit. At the suggestion of one of the officers,

the manager then spoke to each of them and again re

quested that they leave. One of them stood up and inquired

if he could ask a question. As this was done, the other four

appellants arose. The manager replied that he did not

care to enter into a discussion and a third time told appel

lants to leave. Instead of doing so, they resumed their

seats. After waiting several minutes, the officers arrested

all of them and took them to jail.

10a

Opinion of Supreme Court of South Carolina

The foregoing summary is taken from the testimony

offered by the State. Only two of the appellants testified.

They denied that the manager of the store requested them

to leave. They testified that an employee at the lunch

counter stated to them, “You might as well leave because

I ain’t going to serve you”, which they did not construe

as a specific request. They said after it became apparent

that they were not going to be served, they voluntarily left

the lunch counter and as they proceeded to do so, were

arrested. They denied that any of the White customers

got up when they sat down, stating that these customers

did so only after the employee at the lunch counter said:

“Get up, we will get them out of here.”

The questions involved are stated in appellants’ brief

as follows:

“I. Did the Court err in refusing to hold that under

the circumstances of this case, the arrests and con

victions of appellants were in furtherance of a custom

of racial segregation, in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution? (Ex

ceptions 3, 4).

“A. Was the enforcement of segregation in this

case by State Action within the meaning of the

Fourteenth Amendment ?

“B. Were appellants unwarrantedly penalized for

exercising their freedom of expression in violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment 1

“II. Did the State fail to establish the corpus delicti

or prove a prima facie case? (Exceptions 1, 2).”

The questions designated I, A and B, must be decided

adversely to appellants under City of Greenville v. Peter-

11a

Opinion of Supreme Court of South Carolina

son, filed November 10, 1961, ----- S. C. ----- , ----- - S. E.

(2d) ----- , and City of Charleston v. Mitchell, filed Decem

ber 13, 1961,----- S. C. ----- , ----- S. E. (2d) ----- . Each

of these cases involved a sit-down demonstration at a lunch

counter in a privately owned place of business and the

precise questions raised by Exceptions 3 and 4 in the in

stant case were raised in those cases and overruled. In the

City of Charleston case we affirmed a conviction for viola

tion of Section 16-386 as amended, which is the same section

under which the appellants were convicted.

We think that Question II is based on exceptions too

general to be considered. They are as follows:

“1. The Court erred in refusing to hold that the

City failed to prove a prima facie case.

“2. The Court erred in refusing to hold that the

City failed to establish the corpus delicti.”

The foregoing exceptions do not comply with Rule 4,

Section 6 of this Court. They do not point out in what

respect the City failed to make out a prima facie case or

to establish the corpus delicti. We do not know to which

of the two offenses involved these exceptions are directed.

We are not aided by appellants’ brief. Only scant reference

is there made to these two exceptions and apparently the

position is taken that their determination is dependent upon

the disposition of the other questions which we have held

to be without merit.

It has been held that an exception to the effect that the

judgment is contrary to the law and the evidence is too

general to be considered. State v. Turner, 18 S. C. 103;

State v. Cokley, 83 S. C. 197, 65 S. E. 174; State v. Davis,

121 S. C. 350, 113 S. E. 491. The same conclusion has been

12a

Opinion of Supreme Court of South Carolina

reached with reference to an exception “that plaintiff failed

to make out a case against defendant.” Concrete Mix, Inc.

v. James, 231 S. C. 416, 98 S. E. (2d) 841. Other pertinent

cases are reviewed in Hewitt v. Reserve Life Insurance

Co., 235 S. C. 201, 110 S. E. (2d) 852. It was pointed out

in Brady v. Brady, 222 S. C. 242, 72 S. E. (2d) 193, that

“every ground of appeal ought to be so distinctly stated

that the Court may at once see the point which it is called

upon to decide without having to ‘grope in the dark’ to

ascertain the precise point at issue.”

In oral argument counsel for appellants raised the ques

tion of merger of the two offenses and argued that there

could not be a conviction on both charges. But this question

is not raised by any of the exceptions, is not referred to in

the brief of appellants and, therefore, is not properly be

fore us.

Affirmed.

T a y l o r , C.J., L e g g e , M o s s and L e w i s , J.J., concur.

13a

1st the

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

C i t y o f C o l u m b i a ,

Respondent,

— a g a i n s t —

C h a r l e s F. B a r r , R ic h a r d M . C o u n t s , D a v id C a r t e r ,

M i l t o n D. G r e e n e a n d J o h n n y C l a r k ,

Appellants.

Order of Denial of Petition for Rehearing

(Endorsed on back of Petition for Rehearing)

The within petition for rehearing is denied.

Filed: January 8,1962.

s/ C. A. T a y l o r C. J.

s/ G. D e w e y O x n e r A. J.

s / L i o n e l K. L e g g e A. J.

s / J o s e p h R. M o s s A. J .

s/ J. W o o d r o w L e w i s A. J.

•"-BsSp"38