Brown v. Lee Brief and Appendix of Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. Lee Brief and Appendix of Appellees, 1963. 192474c3-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/81ff39da-fe80-489c-9d02-1e3edeb89534/brown-v-lee-brief-and-appendix-of-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

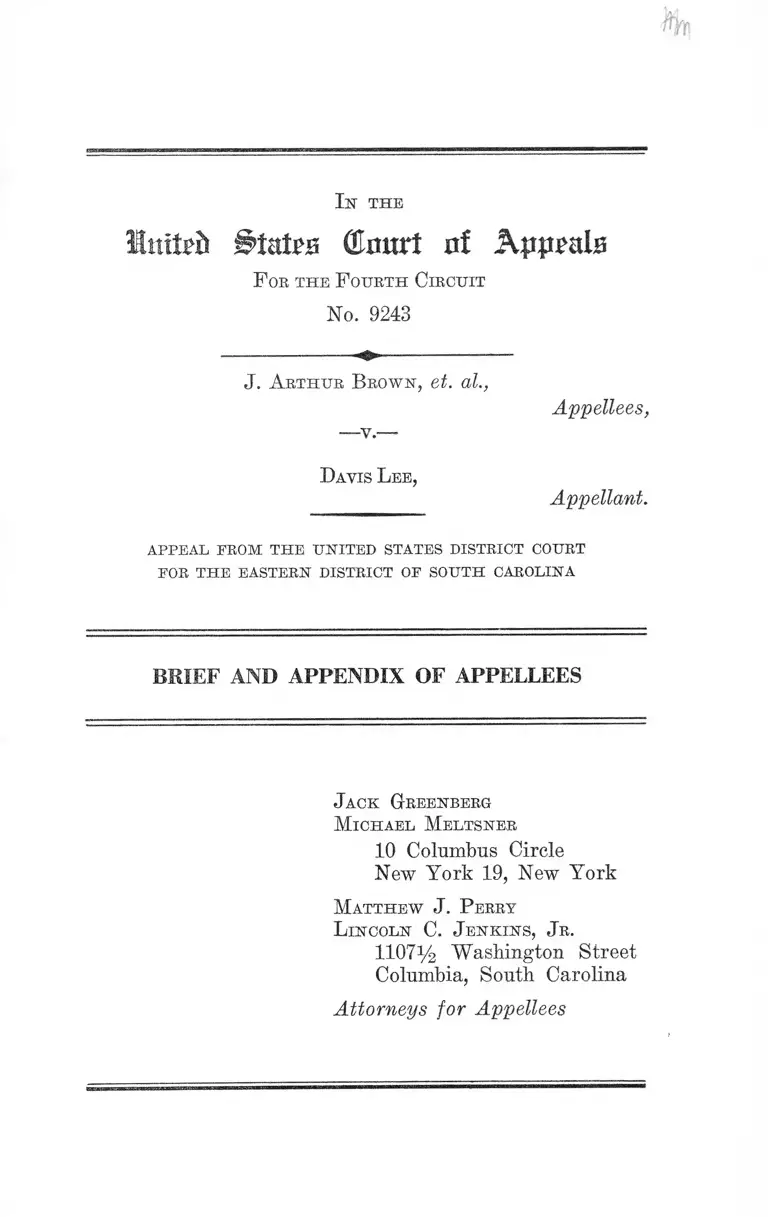

I n th e

Hutted States (Eourt of Appeals

F oe the F otjeth Circuit

No. 9243

J. A rthur Brown, et. al.,

Appellees,

Davis L ee,

Appellant.

APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

POR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

BRIEF AND APPENDIX OF APPELLEES

Jack Greenberg

M ichael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

M atthew J. Perry

L incoln C. Jenkins, Jr.

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Attorneys for Appellees

INDEX TO BRIEF

PAGE

Statement of the C ase........................................................ i

A rgument ............................................................................. g

I. Appellant Lee Never Raised a Legally Permis-

sable Defense for Denying the Relief Granted

Below, and, Therefore, Has No Standing to Com

plain of the Manner in Which Such Relief Was

Granted .... ...... .......................................................... 5

II. The District Court Did Not Abuse Its Discretion

by Enjoining Segregation at Parks and Beaches

Owned and Operated by the State of South Caro

lina ......... ................. ................ .................................. 7

Conclusion.................................................................................... 12

Table op Cases:

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 31 ...................................6,11

Chandler & Price Co. v. Brandtgen & Kluge Inc.,

296 U. S. 53 ...................................................................... 10

Columbia G & E Corp. v. American Fuel & P. Co.,

322 IT. S. 379 .................................................................. 10

Dawson v. Mayor & City Council of Baltimore, 220

P. 2d 386 (4th Cir. 1955), aff’d 350 U. S. 877 .......6,11

East Baton Rouge Parish School Board v. Davis, 287

F. 2d 379 (5th Cir. 1961) ........... ............ .................. 6, 7

11

PAGE

Hansberry v. Lee, 311 U. 8 . 32 ........................................ 6

Louisiana v. NAACP, 366 U. S. 293 ............................... 9

Reynolds Pen Co. v. Marshall Field & Co., 8 F. R. D.

313 (N. D. 111. 1948) ...................................................... 10

St. Helena Parish School Board v. Hall, 287 F. 2d

376 (5th Cir. 1961) ...................................................... 6

Salem Engineering Co. v. National Supply Co., 75 F.

Supp. 993 (W. i). Penn. 1948) ............. -.................... 10

Staude Mfg. Co. v. Berles Cuton Co., 31 F. Supp. 178

(E. D. N. Y. 1939) ........................................................ 10

True Gun-All Equipment Corp. v. Bishop Co., 26

F. R. D. 150 (E. D. Kty. 1960) - ....... .................... 10

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 ........6,11

Statutes :

S. C. Code (1962) §§51.1 et seq......................................... 2

15 U. S. C. §15 ..................... -.............................................. 3

Other A uthority:

Moore’s Federal Practice, §24.17 10

Ill

INDEX TO APPENDIX

PAGE

Motion to Intervene as a Defendant........................_..... la

Intervener’s Answer ........................ 2a

Order Granting Intervention ........................................... 4a

Motion for Leave to Set Up Counterclaim ................... 5a

Counterclaim ........................................................................ 6a

Motion to Bring in Additional Party ........................... 12a

Affidavit of Default ............... 13a

Letter From Appellees’ Counsel to Judge M artin....... 14a

Letter From Appellees’ Counsel to Clerk ..... 16a

Transcript of Hearing ...... 17a

Opinion .................................................................................. 22a

Order ...................................................................................... 31a

Notice of Appeal 32a

Isr th e

Imteft States Court of Appmis

F oe the F otjkth Circuit

No. 9243

J. A rthur Brown, et al.,

-v.-

Appellees,

Davis L ee,

Appellant.

APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

BRIEF OF APPELLEES

Statement of the Case

As the appendix submitted by appellant Davis Lee does

not comply with Rule 10 of the Rules of this Court, appel

lees have printed an appendix to this Brief in order to

provide the Court with portions of the record necessary to

an informed disposition of this appeal.

Appellant’s Statement of the Case does not state fairly

or completely the points involved or the posture of this

appeal and, therefore, appellees include here a Statement

correcting and amplifying that found in appellant’s Brief.

Appellees, eleven Negro citizens of the United States

and South Carolina, filed a complaint in the district court

July 8, 1961,1 naming as defendants the South Carolina 1

1 An Amended Complaint was filed October 17, 1961 which did

not substantially alter the original complaint (22a).

2

State Forestry Commission, the State Forester and State

Park Director. Appellees sought an injunction against

racial segregation at state-owned and operated beaches and

parks and against the enforcement of statutes of the State

of South Carolina which required such segregation, S. C.

Code (1962) §§51.1 et seq. (25a). The complaint was filed

as a “ class action” on behalf of appellees and other Negro

citizens similarly situated “who have been denied the use

of public park facilities in the State of South Carolina.”

On July 11, 1961, appellant Davis Lee filed a Motion to

Intervene as a defendant (la ) and proposed Intervener’s

Answer (2a). Mr. Lee sought intervention on the ground

that he “ is similarly situated like the approximately 900,000

other Negro citizens of South Carolina and as such has a

defense to plaintiffs’ claim presenting both questions of law

and of fact which are common to the main action” (la ). He

alleged that to grant relief against segregation “ would de

prive him and other Negro citizens of the right to freedom

of choice in the selection of their friends” (2a). Neither the

Motion to Intervene or the proposed Answer referred in

any way to claims for money damages, losses suffered by

Mr. Lee’s business or the addition of parties not then before

the court (la-3a).

The Motion to Intervene was granted and the proposed

Answer accepted December 13,1961, the district court grant

ing the motion upon consideration that intervener claimed

“a defense to the plaintiffs’ claim presenting both questions

of law and of fact which are common to the main action”

(4a).

February 5, 1962, Mr. Lee filed a Motion for Leave to

Set Up a Counterclaim and Supplemental Answer on the

ground that the counterclaim was not set up in his original

answer “because he had to wait for the court to rule on his

Motion to Intervene” (5a). He also filed a motion to have

3

the South Carolina Branches of the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) joined

as a party (12a).

The proposed counterclaim (6a-lla ) sought to set up a

claim for ten million dollars “ for violations in restraint of

trade” under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, 15 U. S. C. §15,

against appellees and the South Carolina Branches of the

NAACP. The facts alleged to support the proposed coun

terclaim are confusing, rambling and redundant and no

specific acts are ascribed to the appellees, although there

are eonclusory allegations to the effect that appellees and

the South Carolina Branches of the NAACP supported an

alleged boycott against Mr. Lee’s business, apparently be

cause of his disapproval of the NAACP. Mr. Lee demanded

a trial by jury on the issues raised by the counterclaim

(11a).

On May 28, 1962, Mr. Lee filed an Affidavit of Default,

claiming his proposed counterclaim had not been answered

and, therefore, appellees and the South Carolina Branches

of the NAACP were in default for the sum of ten million

dollars (13a). At this time the court had taken no action

on the Motion for Leave to Set Up a Counterclaim or the

motion to add the South Carolina Branches of the NAACP

as a party to the action.

On April 18, 1963, the district court2 held a hearing on

all pending motions, took evidence and heard oral argu

ment. Among the motions considered were appellees’ mo

tions for a preliminary injunction (filed November 30,

1961) and for summary judgment (filed March 23, 1963)

to end segregation at parks and beaches operated by the

State of South Carolina and enjoin the operation of state

2 The Hon. Judge J. Robert Martin presided at the April 18,

1963 hearing. Prior to the summer of 1962, when he retired, pre

trial motions in the ease were heard by the Hon. Judge George

Bell Timmerman.

4

statutes which required segregation. The transcript of that

proceeding reveals that Mr. Lee, as intervener, was present

and appeared pro se (17a). He argued the merits of his

Motion for Leave to Set Up a Counterclaim and asked the

court to voluntarily dismiss the Affidavit of Default (18a,

19a). He filed also a motion to amend his proposed counter

claim in order to add the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People as a party. He would not

comment on the other motions before the court because,

“ I was not supplied with any of the pleadings,” but stated

to the court, “ I am concerned principally with my personal

action in this matter” (19a). After appellees’ counsel ad

dressed himself to Mr. Lee’s contentions, the court gave

Mr. Lee opportunity to reply (21a) and extended the same

privileges as accorded the other parties with respect to fil

ing memoranda and reply briefs (21a).

July 10, 1963, the district court filed its opinion and order

(22a-31a). The court determined that plaintiffs and other

Negroes similarly situated were entitled to injunctive re

lief to protect their right to use the state parks of South

Carolina and the court issued such an injunction, including

an injunction against the enforcement of the state statutes

which required segregation at parks (31a). The court’s

opinion stated that Mr. Lee had raised no defense capable

of effecting the outcome of the litigation and that his pro

posed counterclaim and motion to add parties would create

issues foreign to the original action (30a):

The Answer of the Intervener, Davis Lee, does not and

could not affect the outcome of this case. Lee’s motion

to bring in additional parties and to file a counterclaim

against the plaintiffs and the additional parties at

tempts to create issues which are foreign to the pres

ent action and to gain jurisdiction of parties over which

this Court does not now have jurisdiction. Mr. Lee

5

may pursue his alleged cause of action in a separate

suit against any parties who may have committed

unlawful acts against him. His motions to bring in

additional parties and to file a counterclaim are hereby

denied.

The judgment entered by the district court did not, however,

mention the proposed counterclaim (31a).

A R G U M E N T

I.

Appellant Lee Never Raised a Legally Permissable De

fense for Denying the Relief Granted Below, and, There

fore, Has No Standing to Complain of the Manner in

Which Such Relief Was Granted.

Appellees take the position that the Court should not

reach the merits of this appeal for the reason that appel

lant Lee never raised any legally cognizable defense to

the relief sought by appellees and, therefore, was improp

erly granted permission to intervene in the first instance.3

He may not complain of the relief received by appellees

below, the manner in which it was granted, or the failure

of the district court to grant him leave to file a counterclaim

because he had no standing to oppose the relief granted.

Mr. Lee sought to intervene on the ground “ that he is

similarly situated like the approximately 900,000 other

Negro citizens of South Carolina, and as such has a defense

to plaintiff’s claim presenting both questions of law and of

3 Appellees also have filed with the Court a Motion to Dismiss

the appeal herein on the grounds of lack of jurisdiction and frivol-

ity.

6

fact which are common to the main action” ( la ).4 * The only

ground for intervention alleged by Mr. Lee and relied on

in the order granting permission to intervene was the con

tention that “ to grant the relief prayed by plaintiffs would

deprive him and other Negro citizens of the right to freedom

of choice in the selection of their friends” (24a). This was

the “ defense to plaintiffs’ claim” for which he sought and

was granted intervention (4a). But this is no defense to

the claim raised by plaintiffs in their complaint for injunc

tive relief prohibiting operation of segregated public facili

ties. The unconstitutionality of segregation at state-sup

ported public facilities is closed as a litigable issue. Dawson

v. Baltimore City, 220 F. 2d 386 (4th Cir. 1955) aff’d 350

U. S. 877; Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526; Bailey

v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 31, 33. Mr. Lee need not avail him

self of his constitutional rights but that does not mean he

can preclude others who desire to exercise their rights from

doing so.

The Fifth Circuit has dealt with this question in St.

Helena Parish School Board v. Hall, 287 F. 2d 376, 379

(5th Cir. 1961) and East Baton Rouge Parish School Board

v. Davis, 287 F. 2d 380 (5th Cir. 1961). In those cases

parents of white school children sought to intervene, in a

suit brought to desegregate the schools, claiming desegrega

4 Should it be consequential, intervention was “permissive” and

not of right as claimed by appellant. Intervention of right was

neither claimed nor granted, for such intervention would require

“representation of the applicant’s interest by existing parties is or

may be inadequate and the applicant is or may be bound by a

judgment in the action,” Federal Buies of Civil Procedure, Rule

24(a). There was no allegation in the Motion to Intervene or find

ing in the order granting intervention of inadequate representa

tion or that Mr. Lee would be bound by a judgment in the action.

Nor could Mr. Lee be bound by a judgment in the action for in a

spurious class suit only the parties are bound. Hansberry v. Lee,

311 U. S. 32, 45. Finally, both the Motion to Intervene and the

order granting intervention use the language of Rule 24(b) Fed

eral Rules of Civil Procedure, “Permissive Intervention.”

7

tion violated their rights. The Fifth Circuit rejected such

intervention as follows, 287 F. 2d at 379.

We also conclude that no legally permissable basis for

denying the relief sought in the complaint was pleaded

of the interveners. It was merely an effort of the inter

vener to obtain a ruling in this trial court that the

Supreme Court decision in the School Segregation Case

was erroneous. This the district court had no power

to do.

As Mr. Lee merely sought to obtain a ruling that segre

gation in publicly owned recreational facilities was con

stitutional, he had no valid claim or defense to raise before

the district court and has no standing to claim error in the

manner which the district court disposed of the issues be

fore it. The procedures followed by the district court are

immaterial to Mr. Lee, for at no time has he raised any

substantive right which could defeat the relief granted by

the district court.

II.

The District Court Did Not Abuse Its Discretion by

Enjoining Segregation at Parks and Beaches Owned

and Operated by the State of South Carolina.

Should the Court reach the merit of Mr. Lee’s appeal, it

will find the district court acted at all times within the area

of discretion granted to it by the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure.

Appellant claims the court below erred “ by hearing Mo

tion for Summary Judgment before completion of the rec

ord.” 5 The only question of fact raised by the complaint—

the segregation of South Carolina’s state parks—was not 6

6 Appellant’s Brief, p. 7.

8

denied by Mr. Lee in his answer (2a). (Indeed segregation

was required by statute, the enforcement of which the dis

trict court enjoined.) Testimony offered by appellees at

the April 18, 1963 hearing established that appellees were

not permitted to enter state parks although white persons

were admitted at the same time. This evidence was not

contradicted. As there were no material or genuine issues

of fact before the court, disposition of the legal issues on

summary judgment was appropriate.

Appellant’s “ Motion for Declaratory Judgment,” filed

over 30 days after the April 18, 1963, hearing does not sup

ply a factual issue. The motion attacked the procedures

followed by the district court at the April 18, 1963 hearing,

such as the sequence in which the court heard the various

motions before it and the court’s decision to hear oral testi

mony. Mr. Lee was present at the hearing and able to raise

these objections at that time. He cannot toy with the court

by objecting to trial procedures while a case is pending

decision over 30 days after the time of trial. A district

court acts within its allowable discretion when it determines

the order and character of the motions and evidence it will

hear. Such objections as were not made at the hearing were

waived. The cases cited by appellant in which summary

judgment was denied are not relevant. In those cases there

were genuine issues of fact outstanding with respect to

the merits of a cause. That is not the case here.

Appellant claims that the district court erred in not, on its

own motion, ordering counsel for the other parties to serve

him with those “ pleadings” 6 he claimed he had not received.

Appellant does not now indicate the “ pleadings” which he

did not have nor does he explain why he did not move the

court below to require service. 6

6 Mr. Lee in his Brief refers to “pleadings” but he seems to refer

to papers filed in the case and pleadings indiscriminately.

9

At the conclusion of the April 18, 1963 hearing appellant

Lee stated for the first time that he had not received all

the “ pleadings” in the case. He did not state which “ plead

ings” he had not received or request that he receive specific

“ pleadings” from the appellees. He did not move the court

to require service of such “ pleadings” as he claimed he had

not received. Mr. Lee may not have received all of the

papers exchanged by the parties prior to the granting of his

Motion to Intervene, but certainly there is no responsibility

to serve ag intervener before he is made a party. After

Mr. Lee was granted permission to intervene, appellees

served Mr. Lee with all pleadings and papers filed in the

case pertaining to him and required to be served. On March

22, 1963, Mr. Lee was served with the Motion for Summary

Judgment and was informed by counsel for appellees of

the matters which would be brought before the court on

April 18, 1963 (14a-16a). Appellant had almost a month to

prepare for the hearing and request such papers as he had

not received, but he chose to remain silent. By his conduct,

he is barred from asserting now what he could have easily

remedied prior to the April 18 hearing.

Appellant claims that the court below erred in permitting

witnesses to testify at the April 18, 1963 hearing when the

Motion for Summary Judgment did not specifically men

tion that witnesses would testify. Appellant relies on Rule 7

of Federal Rules of Civil Procedure to support this con

tention, but Rule 7 only states that the “ grounds” for a

motion must be stated in the motion. It does not require

that a litigant state the manner in which he intends to

establish the “ grounds” stated. A decision to hear oral

testimony in support of Motions for Summary Judgment

and Preliminary Injunction is clearly in the discretion of

the District Judge. See Louisiana v. NAACP, 366 U. S.

293, 298 (Mr. Justice Frankfurter concurring).

10

Appellant Lee claims an intervener has an absolute right

to file a counterclaim regardless of its subject matter or

the parties it seeks to join. He claims that the district court

was bound in this litigation to hear his ten million dollar

damage claim for restraint of trade against appellees and

parties not before the court. He offers no authority for

this theory other than general statements from commen

tators.

It has long been settled, however, that an intervener is

not permitted to assert claims beyond the issues framed by

the pleadings. Chandler <& Price Co. v. Brandt gen & Kluge,

Inc., 296 U. S. 53, 56-59 (1935). The Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure have not relaxed this principle that an intervener

cannot bring by counterclaim issues not in dispute between

the original parties or in which one of the original parties

has no interest. See Columbia G <fc E Corp. v. American

Fuel & P. Co., 322 U. S. 379, 383 (1944). (“As an intervener

the United States was limited to the field of litigation open

to the original parties, Chandler Co. v. Brandtjen and

Kluge, 296 U. S. 53, 57-60” ) ; Reynolds Pen Co. v. Marshall

Field & Co., 8 F. R. D. 313 (N. D. 111. 1948); Staude Mfg.

Co. v. Berles Cuton Co., 31 F. Supp. 178 (E. D. N. Y. 1939);

Salem Engineering Co. v. National Supply Co., 75 F. Supp.

993 (W. D. Penn. 1948). Indeed, if it had been known at

the time Motion to Intervene was filed that Mr. Lee would

seek to introduce extraneous issues into the case, the grant

of intervention would have been improper. See True Gun-

All Equipment Corp. v. Bishop Co., 26 F. R. D. 150 (E. D.

Kty. I960).7

7 It is true that Professor Moore has directed some criticism

toward this rule suggesting that a district court might order sepa

rate trials, 4 Moore’s Federal Practice §24.17, p. 135, but his posi

tion has not been adopted. And even Moore takes the position that

the district court should limit counterclaims which would unduly

delay or complicate the issues before the court.

11

Appellant claims that the decision of the district court

is erroneous because he is a Negro and does not wish to halt

segregation and because he did not have an opportunity to

convince the district court appellees have no right to de

segregated state parks. Both these contentions are un

acceptable in light of Supreme Court decisions establishing

beyond any doubt Negro citizens’ right to use of state

parks without discrimination on the basis of race. Watson

v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526; Bailey v. Patterson, 369

U. S. 31, 33; Dawson v. Mayor and City Council of Balti

more, 350 U. S. 877. Nor does Mr. Lee indicate how he was

denied the opportunity to support his position. He directs

us generally to the transcript of the April 18, 1963 hearing

but, far from suggesting he was denied his right to partici

pate, that transcript indicates he was given every oppor

tunity to express himself on the questions before the court

(18a-21a). His claim that the court interfered with his

right to participate is baselesss and, significantly, Mr. Lee

never confronted the court at the time of the hearing with

any complaint that the court was not giving him a fail-

opportunity to express himself.

12

CONCLUSION

W herefore, for the foregoing reasons, appellees pray

that the judgment of the district court be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Matthew J. Perry

L incoln C. Jenkins, Jr.

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Attorneys for Appellees

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

Davis Lee, the above applicant for intervention, move the

Court for an order permitting him to intervene as a defen

dant in the above entitled action and permitting his pro

posed answer annexed hereto to be filed as the answer of

said intervenor in this action, upon the grounds that he is

similarly situated like the approximately 900,000 other

Negro citizens of South Carolina, and as such has a defense

to plaintiffs’ claim presenting both questions of law and

of fact which are common to the main action.

Davis Lee

407 Butler Street,

Anderson, S. C.

July 11, 1961

Motion to Intervene as a Defendant

(Filed: July 11, 1961)

2a

Comes now Davis Lee, who has filed herewith his motion

to intervene under Eule 24 of the rules of Federal Civil

Procedure, and submits this as his annexed answer.

1. The applicant to intervene is a citizen of South Caro

lina. He lives at 407 Butler Street, Anderson, South Caro

lina, and is publisher of several weekly newspapers, and is

directly affected by any class action brought by any group

who claims to represent all of the Negro citizens of this

state.

2. The applicant to intervene contends that plaintiffs and

their attorneys have declared that this action was brought

on behalf of themselves and all other persons “ similarly

situated” ; that he regards himself as being “ similarly situ

ated” , and that he has not authorized anyone to bring any

action on his behalf, and that he feels that the majority of

Negro citizens of this state have not authorized anyone to

represent them.

3. This intervener feels that to grant the relief prayed

by plaintiffs would deprive him and other Negro citizens of

the right to freedom of choice in the selection of their

friends.

4. That the complaint does not contain a cause of action

upon which relief can be granted in its present form.

5. That the complaint is defective in that it claims to be

brought under existing Federal Statutes for the violation

of rights guaranteed under the Constitution which require

Intervener’ s Answer

(Filed: July 11, 1961)

3a

Intervener’s Answer

no Jurisdictional amount, yet plaintiffs have set up a Juris

dictional amount in a complaint in which a money judg

ment is not sought.

Davis Lee

Intervener and Attorney

407 Butler Street,

Anderson, S. C.

July 11, 1961

4a

This cause came on to be heard on the motion of Davis

Lee, an individual, for permission to intervene and be made

a party defendant in the above entitled suit and to file his

proposed answer to the complaint in this suit.

The motion of the applicant for intervention is made upon

the ground that he is similarly situated like the approxi

mately 900,000 other Negro citizens of the State of South

Carolina and, as such, has a defense to the plaintiffs’ claim

presenting both questions of law and of fact which are com

mon to the main action.

Upon consideration of the motion of said Davis Lee, the

motion is hereby granted.

It is further ordered that the proposed answer of the

intervenor, Davis Lee, to the complaint shall stand as

and for the answer of the said Davis Lee to the complaint

in the above entitled action, and it is further

Ordered that the proceedings heretofore had or taken in

this action shall be effective for and against the said Davis

Lee, made a party defendant to this action by this order.

George B ell T immerman

United States District Judge

December 13, 1961

Order Granting Intervention

(Filed: December 12, 1961)

Motion for Leave to Set Up Counter-Claim

(Filed: February 5, 1962)

Comes now, Davis Lee, defendant by intervention, and

moves the court for leave to file a supplemental answer and

counter-claim, a copy of which is attached hereto, on the

ground that defendant failed to set up the said counter

claim in his original answer because he had to wait for the

court to rule on his motion to intervene.

February 5, 1962

Davis Lee

407 Butler Street

Anderson, South Carolina

6a

Counter-Claim

(Filed: February 5, 1962)

The Counter-Claimant Alleges:

1— That he is a defendant by intervention and that juris

diction of the court is based on allegations of Federal

violations in original complaint.

2— That this counterclaim is brought on behalf of this

defendant by intervention, and all other citizens of South

Carolina, both Negro and White, who have lost homes,

businesses, jobs, credit standing or other valuable considera

tion as the result of the unlawful activities of these plaintiffs

and The South Carolina Branches of The NAACP.

3— That The South Carolina Branches of The NAACP

be made a party to this action.

4— That this counterclaim is a suit for damages, and for

injunctive relief, seeking relief for the redress for boycotts

and other unlawful acts in restraint of trade in violation

of South Carolina Code Article 2, section 66-64, and for

violation of The Sherman Anti-Trust Act F. R. C. P. 8 (a),

28 U. S. C. A. section 1337, and for violations in restraint

of trade under Title 15 section 15 United States Code An

notated to section 26.

5— That this counterclaimant brings this action under sec

tion 10-205, South Carolina Code of laws, in behalf of him

self, and thousands of citizens like himself, who have been

hurt, and suffered great financial losses through the unlaw

ful acts of these plaintiffs and the branches of The NAACP

in South Carolina that these injured citizens, constitute a

class so numerous as to make it impossible to bring them all

before the court at this time.

7a

6— That this counterclaimant is the publisher of several

weekly newspapers. That his papers have opposed pressure

groups and agitators; And that he has pointed out to his

readers from time to time that these groups have done his

race more harm than good. His editorials have been re

printed around the world; They have been reproduced in

daily and weekly papers in every state in this nation, and 26

of them have been inserted in The Congressional Record.

7— Because of the wide circulation given Ms views, and

the influence they have had on the thinking of the masses of

Negroes, These plaintiffs and The South Carolina Branches

of The NAACP, which they head and and help to direct,

have entered into a conspiracy to silence and put this

counterclaimant out of business.

8— For a newspaper to survive and be self sustaining, it

must have circulation and advertising.

9— These plaintiffs and The South Carolina Branches of

The NAACP were aware of the above facts, so they there

by entered into a conspiracy with each other to prevent this

defendant’s newspapers from building the circulation and

from getting the advertising.

10— That on or about October 15th, 1958, citizens of Rock

Hill, South Carolina, who were shocked at the high handed

pressure tactics of the local branch of The NAACP, invited

this counterclaimant to visit their city. As the result he

wrote and published a series of articles and editorials. 11

11— Officials of the local branch began an immediate boy

cott of his newspaper. Dr. Duckett, wealthy Negro Physi

cian who has backed The NAACP financially, went to

Counter-Claim

8a

agents and frightened them to the extent that they were

afraid to sell the paper.

12— The papers were shipped to Rock Hill by Trailway

bus, and the Negro attendant, who was a member of The

NAACP, held the papers and hid them until the date

on the papers had expired.

13— The Rock Hill branch appealed to other branches

for an all out boycott of counterclaimant’s paper. An ap

peal was made to the national office in New York for help

to destroy this counterclaimant and Ms newspapers. The

national office responded to the request.

14— Mass meetings were held throughout the state.

Meetings were held at State College at Orangeburg and

Negro lawyers and business leaders from the two Caro-

linas met and discussed how to get rid of this counterclaim

ant.

15— An Anderson Negro preacher, who pastored three

churches at the time, approached a shady character follow

ing a meeting of the local NAACP in January, 1959, and

offered him $500.00 to way-lay this counterclaimant. This

defendant was tipped off about the plot and headlined it in

his. newspaper.

16— Throughout South Carolina and other states, the boy

cott against counterclaimant’s newspapers have spread.

17— A leading chain of banks in South Carolina placed

an advertisement in counterclaimant’s South Carolina

paper. The Ad ran for nearly two years. In 1960 one of

the Vice-presidents, called and informed this counter

Counter-Claim

9a

claimant that the bank would have to cancel the A d ; That

northern textile officials, who had large deposits, claimed

that the bank was supporting this defendant against The

NAACP, and if the bank did not discontinue the Ad, the

textile firm would move its account. The bank canceled

the Ad.

18— These acts and conspiracies on the part of these

plaintiffs and the branches of The NAACP in South Caro

lina were successful to the extent that counterclaimant has

been bankrupted; that his credit has been jeopardized, and

he has been embarrassed financially.

19— To that end, and for that purpose, the plaintiffs and

The South Carolina branches of The NAACP, connived and

conspired with each other to do and make, and pursuant

to the conspiracy did and made, the above acts, all of

which were done and made for the1 purpose of destroying

counterclaimant’s newspaper in violation of the rights

guaranteed to him by The First and 14th Amendments to

The Federal Constitution.

20— That counterclaimant took over The Savannah Trib

une, a weekly Negro newspaper November 1, 1960, and the

local branch of The NAACP, at the direction of W. W. Law,

local president and Georgia State president, immediately

circulated a petition to get members to sign that they would

not read the paper.

21— Thus the Georgia NAACP became a part of The

conspiracy to destroy this counterclaimant and his news

papers. Pressure was brought to bear on advertisers to keep

them from advertising in counterclaimant’s newspaper— A

large number of Negro business places that sold other

Counter-Claim

10a

Negro newspapers refused to permit the distributor to

leave this defendant’s newspaper in their places for sale.

22— That these plaintiffs and The South Carolina

branches of The NAACP brought suit to force the state to

integrate Edisto Beach State Park. This action forced the

state to close the park. John Doe, a state employe, was

thrown out of work, and a few weeks later he lost his home

and everything that he had.

23— John Doe The 2nd is the operator of a Men’s clothing

Store in Sumter, South Carolina. He spoke out against

the pressure tactics that was being employed by the local

NAACP. An immediate boycott was organized against him

to the extent that he has lost $100,000 per year in revenue.

24— John Doe The 3rd operated a bus company in Rock

Hill, South Carolina. The local NAACP demanded that he

integrate his buses, when he refused to comply an im

mediate boycott was imposed. He was forced to suspend

operation, and the local NAACP purchased two buses and

went in the bus business.

25— This counterclaimant alleges and avers that thou

sands of John Does have been hurt all over South Carolina

by the acts of these plaintiffs and The South Carolina

branches of The NAACP, that only fictitious names have

been used, to protect these victims from further reprisals,

but that this counterclaimant, after obtaining their consent,

will amend this complaint and insert their true names.

26— As a result of the combination and conspiracy herein

before alleged and of the various acts done in pursuance

thereof by these plaintiffs and the branches of The NAACP

Counter-Claim,

11a

and others, as herein alleged, The power and influence

of the association has been greatly increased, and all South

Carolina businesses that oppose the pressure techniques

of the association will be boycotted.

27—Under the law, both state and Federal, every member

of an un-incorporated association is personally liable for

the conduct and acts of the un-incorporated association.

This counterclaimant is of the opinion, and has reason

to believe, that the branches of The NAACP in South Caro

lina are un-incorporated, and that each member is person

ally liable under the law for damages inflicted by the boy

cotts.

Wherefore, counterclaimant prays judgment against the

plaintiffs and The South Carolina branches of The NAACP,

and against each of them for the sum of $10,000,000 (Ten

Million Dollars), treble damages, as provided by said

Clayton Amendment to the said Sherman Anti-Trust Act,

together with a reasonable counsel fee, and besides the

costs and disbursements of this action.

Counterclaimant demands trial by jury.

Dated: February 5,1962

Counter-Claim

Davis L ee

407 Butler Street

Anderson, South Carolina

12a

Motion by Defendant to Bring in Additional

Party Because of Counter-Claim

(Filed: February 5, 1962)

1— Defendant Davis Lee, moves the court to make an

order bringing in The South Carolina Branches of The

NAACP as an additional party directing that a summons

be served upon J. Arthur Brown, State President, who is

also a plaintiff in this cause, requiring him to answer.

2— That J. Arthur Brown as a citizen of South Carolina,

so that jurisdiction of said South Carolina Branches of the

NAACP can be obtained and the joinder will not deprive

the court of jurisdiction of the action.

Davis L ee

407 Butler Street

Anderson, South Carolina

February 5,1962

13a

Affidavit of Default

(Filed: May 28, 1962)

Comes now, Davis Lee, defendant by intervention in the

above entitled cause, and moves this court for a judgment

by default in the above-entitled cause, and shows that the

counter-claim in the above cause was filed in this court on

the 6th day of Feb., 1962 and that copy of such counter

claim was sent to the attorneys of the plaintiffs by the

clerk of this court on the 6th day Feb. 1962; that no answer

or other defense has been filed by the plaintiffs.

Wherefore, defendant moves that this court make and

enter a judgment by default against the plaintiffs and The

South Carolina branches of the NAACP, and against each

of them for the sum of $10,000,000 (Ten Million Dollars),

treble damages, as provided by said Clayton Amendment to

said Sherman Anti-Trust Act, together with reasonable

counsel fee, and besides the cost and disbursements of this

action.

Counterclaimant demands trial by jury.

Davis L ee

407 Butler Street

Anderson, South Carolina

Dated: May 28,1962

(Seal)

Ollie M. Stalling

Notary Public for S. C.

Sworn before me this 28th day of May, 1962.

14a

(March 22, 1963)

Honorable J. Robert Martin

United States District Judge

Greenville, South Carolina

R e : Brown, et al. v. S. C.

Forestry Commission, et al.

Civil Action No. 774

Dear Judge Martin:

We request a hearing in the above case as soon as possible.

As you probably know, this case has been pending since

July, 1961 and there are numerous motions which remain

pending. These are as follows:

1. Plaintiffs’ Motion for Preliminary Injunction.

2. Intervener’s Motion for Leave to file Counterclaim.

3. Intervener’s Motion for Judgment by Default.

4. Plaintiffs’ Motion to Strike Portions of Defendants’

Answer.

5. Plaintiffs’ Objections to Interrogatories Propounded

by Defendants.

6. Plaintiffs’ Objections to Defendants’ Requests for

Admission.

7. Defendants’ Motion for an Advisory Jury.

In addition to the above, we are today filing Notice of Mo

tion for Summary Judgment. I have inserted April 18,

1963 as the date for hearing of this motion. However, if

that date is not satisfactory with the Court, we request that

Letter to Judge Martin

15a

you set a date for the hearing of this and other pending

motions as soon as your schedule permits. In the event the

matter cannot be disposed of on the Motion for Summary

Judgment, we request an early trial upon the merits.

With kindest regards, I am

Respectfully yours,

Matthew J. Perky

M JP :a

c c : Honorable Daniel R. McLeod

. Attorney General of South Carolina

Columbia, South Carolina

Mr. David W. Robinson

Robinson, McFadden & Moore

Attorneys at Law

1213 Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Mr. Davis Lee

407 Butler Street

Anderson, South Carolina

Letter to Judge Martin

1 6 a

(March 22, 1963)

Mr. John C. Rogers

Deputy Clerk of Court

United States District Court

Columbia, South Carolina

R e : Brown, et al. v. S. C.

Forestry Commission,

et al.— C /A No. 774

Dear Mr. Rogers:

I am herewith enclosing the original and copy of Notice of

Motion for Summary Judgment in the above matter for

filing in your office. Copies of same are being forwarded to

Defendants’ Counsel

Letter to Clerk

Yery truly yours,

Matthew J. Perry

MJP :a

Enclosures

c c : Honorable Daniel R. McLeod

Attorney General of South Carolina

Columbia, South Carolina

Mr. David W. Robinson

Robinson, McFadden & Moore

Attorneys at Law

1213 Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Mr. Davis Lee

407 Butler Street

Anderson, South Carolina

17a

Hearing on Motions

1st the

DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

F oe the E astern D istrict of South Carolina

Columbia D ivision

C /A AC-774

— 1 —

J. A rthur Brown, et al.,

—vs.—

Plaintiffs,

S. C. F orestry Commission, et al.,

Defendants.

Motions pending in the above case came on to be heard

in the United States Courtroom at Columbia, South Caro

lina, on the 18th day of April, 1963, with

H onorable J. Robert Martin, Jr.,

United States District Judge, Presiding.

A p p e a r a n c e s :

Matthew J. Perry, Escp, and

L incoln C. Jenkins, Jr., Esq.,

For the Plaintiffs

David W. Robinson, Esq., and

Harry L ightsey, Jr., Esq.,

For the Defendants

Davis L ee, Esq.,

For Intervenor

18a

Hearing on Motions

* * * * *

The Court: I believe you have got a motion as to the

intervention.

Mr. Perry: Yes, sir.

—43—

Mr. Robinson: Do I understand that counsel is not going

to press his motion for summary judgment or for temporary

injunction?

Mr. Perry: Yes, sir, I do intend to press them. How

ever, I thought that the intervenor would now proceed with

his motions, and then of course we would conclude with

our motions for preliminary injunction and for summary

judgment, unless the Court would prefer otherwise.

The Court: Well, Mr. Robinson, I don’t imagine is inter

ested in the latter part of it. Suppose we clear him off

as of this time, if that is all right with you.

* * * * *

— 69—

* * * * *

The Court: You are the movant as far as the intervenor

is concerned?

Mr. Perry: No, sir, Mr. Lee is the intervenor and repre

sents himself.

The Court: Very good.

Mr. Lee: If it please the Court, I would like to give a

posture of the case as it stands now.

In July of 1961 these plaintiffs filed their complaint in

this court as a class action. I took the position that they

didn’t represent me, and that I wanted to declare that so

that everybody would know that when they said that the

—70—

action was brought on behalf of everybody similarly situ

ated that that didn’t apply to me.

— 42—

19a

In September of 1961 I filed a motion to intervene as a

defendant in the case. Judge Timmerman heard the motion

in December and granted my motion.

In February of 1962 I filed an amended answer which

included a counterclaim. The plaintiffs didn’t answer, and

later I filed an affidavit of default. In connection with the

affidavit of default, I wish to submit at this time a motion

for voluntary dismissal of the affidavit of default, and a

motion to amend the counterclaim.

It is impossible for me to comment on the matters that

transpired here before noon, because of the fact that I was

not supplied with any of the pleadings by either the plain

tiffs’ counsel or counsel for the defendants. I am concerned

principally with my personal action in this matter.

Up to now the plaintiffs have filed no pleadings as far as

I am concerned. And because of the fact that they have not

filed any pleadings where I am concerned, their motion

for summary judgment where I am concerned is premature.

And that is my position, your Honor.

Mr. Perry: Your Honor, may it please the Court if I

understand the posture of this matter correctly, Judge

Timmerman passed an order allowing Mr. Lee to intervene

on the ground that Mr. Lee had represented that the plain-

—71—

tiffs in this action did not represent him in that he is not

a member of the class— or rather that he is a Negro but

that he had never authorized anyone to represent him in

this action, and that therefore he wanted to come in and

let it be known that he was not a party to this suit.

Thereafter, Mr. Lee filed a motion for leave to file a

counterclaim. The counterclaim, the proposed counterclaim

was attached to the motion for leave to file the counterclaim

and purported to seek damages against these plaintiffs and

Hearing on Motions

20a

certain other parties in the sum of ten million dollars. The

motion for leave to file the counterclaim has never been

heard and passed upon. Hence, we take the position that

it is not before the Court, unless of course your Honor will

at this time entertain that motion, which we, I hasten to say,

do not urge.

I might say further that—well, may I inquire, sir, as to

where we are now on the motion? Does the Court consider

that the plaintiff has urged his motion for leave to file a

counterclaim?

The Court: I would interpret it that that is what he is

now asking.

Mr. Perry: I see. Well I believe, sir, that the proposed

counterclaim seeks damages under the Sherman antitrust

amendment, and it seeks damages against the named plain

tiffs and against the class of persons the named plaintiffs

- 7 2 -

purport to represent, and also against certain other parties,

namely, the National NAACP, the State NAACP, who are

not parties to this proceeding.

Now the proposed basis for the intervenor’s claim or the

alleged basis of it would appear to be matters foreign to

this suit. The intervener was allowed to come into this

matter because of his assertion that the State of South

Carolina could not properly defend in his behalf, and that

he wanted to interpose a special defense. The proposed

counterclaim does not in any way address itself to any

thing contemplated by the original action. And if it is felt

that a cause of action exists under the Sherman anti-trust

act, why, that can be made the basis of a completely sepa

rate suit. We respectfully urge that it has no place as a

part of this action.

I thank you, sir.

Hearing on Motions

21a

Tlie Court: Is there anything you care to say in reply?

Mr. Lee: If it pleases the Court, an intervenor might

bring a counterclaim on any cause of action that he might

have, that is not even connected with this particular action.

The Court: As in the other matters, I will extend the

same privilege of 15 days for each to file a memorandum of

your positions, the authorities that you care to submit, and 5

- 7 3 -

days after which to file replies.

Mr. L ee: Thank you, sir.

Mr. Perry: Thank you, sir.

Hearing on Motions

22a

(Filed: July 10, 1963)

This suit was originally filed on July 8,1961, by the plain

tiffs for their own benefit and on the behalf of all other

persons similarly situated. In the Complaint the plaintiffs

allege that they are denied the use of public park facilities

in the State of South Carolina solely because they are

Negroes in violation of their constitutional rights. The

plaintiffs ask that certain statutes of the State of South

Carolina, which allegedly require racial discrimination in

the public park system in South Carolina, be declared un

constitutional and that the defendants be enjoined from

prohibiting them and other Negroes similarly situated from

making use of the public parks and beaches owned and

operated by the State of South Carolina.

By Order of The Honorable George Bell Timmerman,

dated September 17, 1961, the plaintiffs filed an Amended

Complaint on October 17, 1961, which, in effect, asked for

the same relief as the original complaint.

On November 30, 1961, plaintiffs filed a Motion for Pre

liminary Injunction in which they asked that the Court

grant a preliminary injunction against the defendants re

straining them from enforcing certain statutes of South

Carolina and from discriminating against Negroes in re

gard to the use of the public parks and beaches owned and

operated by the State of South Carolina until this suit

could be heard on its merits.

On December 17, 1963, the defendants filed an Answer in

which they admit that the State of South Carolina operates

some parks for white citizens and some parks for Negro

citizens in accordance with State law but deny that such

operation of the park facilities deprives the plaintiffs of

their constitutional rights. Defendants further allege that

Opinion and Order

23a

this action is brought in reality by nonresident corpora

tions.

Along with the Answer, defendants moved that the issues

in the cause be tried by the Court with an Advisory Jury.

On January 2, 1963, plaintiffs filed a motion to strike

paragraphs (11), (12), (13), (15) and so much of para

graph (16) as alleges “ This action is in reality an effort

by nonresident corporations to enforce alleged rights to

equal protection possessed by individuals.”

On January 11, 1963, defendants propounded fifteen in

terrogatories to the plaintiffs in which they seek informa

tion pertaining to the National Association for the Ad

vancement of Colored People; the NAACP Legal and

Educational Defense Fund, the relationship between the

NAACP and its Legal and Educational Defense Fund, the

offices held in the NAACP by the plaintiffs Newman,

Shaprer, Brown and Nelson; the payment of legal fees

to the attorneys representing the plaintiffs in this ac

tion (and other suits pending in the Federal Courts) and

the status of the attorneys in relation to the NAACP or

its Legal and Educational Defense Fund. The plaintiffs

promptly filed objections to all interrogatories propounded

upon the ground that they are irrelevant, immaterial, im

pertinent and not directed to any issue in controversy in

this action.

On March 23, 1963, the plaintiffs filed a Motion for Sum

mary Judgment under the provisions of Rule 56 of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

On July 11, 1961, Davis Lee, moved the Court for an

Order permitting him to intervene in the action as a defen

dant, and file an Answer to the complaint in the suit, upon

the ground that he was similarly situated like the approxi

mately 900,000 Negro citizens of the State of South Carolina

and, as such, has a defense to the plaintiffs’ claim present

Opinion and Order

24a

ing both questions of law and of fact which are common to

the main action. By order of The Honorable George Bell

Timmerman, dated December 13, 1961, the motion was

granted and the Answer of the defendant Davis Lee was

filed effective October 12, 1961.

On February 5, 1962, the defendant Davis Lee filed a

motion to bring in the action an additional party, the South

Carolina Branches of the National Association for the Ad

vancement of Colored People. At the same time the said

defendant filed a motion for leave to file a “ supplemental

Answer and counterclaim,” the proposed counterclaim was

filed as an attachment to the latter motion. In the pro

posed counterclaim, defendant asks damages against the

plaintiffs and the South Carolina branches of the NAACP

in the sum of $10,000,000, treble damages, as provided by

the Clayton Amendment to the Sherman Anti-Trust Act on

the theory that the plaintiffs in concert with the South

Carolina Branch of the NAACP has disrupted his news

paper business and has injured the business of other citi

zens by organized boycotts of trade and other alleged un

lawful activity. On April 18, 1963, the defendant, Davis

Lee, filed a proposed amendment to the original proposed

counterclaim in which he alleges that the NAACP also con

spired in the activities referred to above and asks for the

sum of $500,000 treble damages, as provided by the Clayton

Amendment to the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. At the same

time the defendant, Davis Lee, moved the Court for an

Order joining the National Organization and the South

Carolina Branches of the NAACP as parties to the action.

On April 18, 1963, this Court held a hearing on all the

pending motions in Columbia, South Carolina, at which

time all arguments were heard and testimony was intro

duced in connection with the Motion for Summary Judg

ment. The Court took all motions under advisement and

Opinion and Order

25a

gave counsel for the parties permission to file briefs in

support of their respective positions.

The State of South Carolina operates a total of twenty-

six State Parks, nineteen of which are designated for the

use of white citizens and seven of which are designated for

the use of Negro citizens. The State Park system is oper

ated pursuant to State Statutes which are as follows:1

“ § 51.1. The State Commission of Forestry may con

trol, supervise, maintain and wherever practicable im

prove all parks belonging to the State or for general

recreational and educational purposes.

“ § 51-2.1. The State Commission of Forestry may oper

ate and supervise only racially separate parks. The au

thority to operate and supervise racially integrated

parks is denied to the Commission, the State Forester,

the State Director, and the Superintendent of State

Parks.

“ § 51-2.2. No person shall have access to the facilities

of the State parks without the express permission of

the State.

“ § 51-2.3. The State Commission of Forestry may ad

mit to the facilities of the State parks only persons

having the express permission of the State to use such

facilities. The authority to admit to the facilities of

the State parks persons who do not have the express

permission of the State to sue them is denied to the

Commission, the State Forester, the State Director,

and the Superintendent of State Parks.

“ § 51-2.4. Permission is hereby granted to the citizens

of the State to use the facilities at the parks for their

Opinion and Order

1 References are to the South Carolina Code (1962).

26a

own race under such rules and regulations not incon

sistent with the provisions of §§ 51-2.1 to 51-2.2.3 as

the State Commission of Forestry may establish.”

The State Parks are geographically located throughout

the State so that a park is reasonably accessible to all the

people regardless of where they reside. Because of the

greater number of white parks than Negro parks, the white

parks are much more accessible to the white population

than the Negro parks are to the Negro population. The

parks are located in areas outside of urban communities.

None of them have the benefit of city police protection.

Generally speaking, the recreational activities in these parks

consists of swimming, camping, picnicking and in some cases

the rental of cabins. The parks employ no law enforcement

officers as such and must rely upon the local law enforce

ment authorities for the preservation of law and order.

During the year 1962, some three million people made use

of the State Parks’ facilities in South Carolina.

On August 30, 1960, three of the plaintiffs, J. Arthur

Brown, H. P. Sharper and J. Herbert Nelson, presented

themselves at Myrtle Beach State Park, one of the beaches

maintained by the State of South Carolina. When the plain

tiffs arrived at the park entrance, they were advised that

the park was closed and were denied admission. At the

time the park was occupied by white persons and there is no

evidence that such persons were required to leave the park.

On June 15, 1961, J. Arthur Brown, Edith Davis, Mary

Nesbitt, Hils Norris, Jr., Murry Canty, Sam Leverett and

Gladys Porter attempted to enter Sesqui Centennial Park,

located near Columbia, South Carolina. Upon their arrival

at the park entrance, Chief J. P. Strom, of the South Caro

lina Law Enforcement Division informed the plaintiffs that

the park had been closed and that they could not enter.

Opinion and Order

27a

All of the plaintiffs are members of the NAACP and

some of them hold offices in that organization. All the plain

tiffs were residents and citizens of the State of South Caro

lina at the time they attempted to enter the parks and at

the time this suit was instituted but subsequently H. P.

Sharper and Edith Davis have moved from the State of

South Carolina.2

There can be no doubt that the plaintiffs were denied ad

mission to the State Parks because they were Negroes; in

fact, under the statutory law of South Carolina, they were

and are prohibited from using the nineteen parks desig

nated for white persons.

The recent case of Watson v. Memphis, ------ U. S. --------

(No. 424) decided May 27, 1963, by the United States Su

preme Court dictates to this Court the decision which must

be reached in the present case. In the Watson ease, the

plaintiffs brought a class action against the City of Mem

phis, Tennessee, in which they alleged that the City had

denied certain of the plaintiffs access to various recre

ational facilities owned and operated by the City. The

City admitted that it operated a majority of the facilities

on a segregated basis and admitted that it must terminate

this practice but contended that complete desegregation of

the recreational facilities should be done gradually. At the

trial in the District Court, the defendant offered testimony

of several law enforcement officers who stated that, in their

opinion, if the facilities were integrated, racial strife would

develop to such an extent that it would be necessary to close

many of the parks thus depriving many citizens of these

facilities. The District Court denied the relief sought by

the plaintiffs and ordered the city to submit within six

2 These plaintiffs no longer have standing to pursue this action

and they are hereby dismissed as plaintiffs.

Opinion and Order

28a

months a plan3 for the gradual integration of all facilities.

On appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit,

the Order of the District Court was affirmed. 303 F. 2d 863.

The United States Supreme Court Reversed. Mr. Justice

Goldberg in his opinion for the court said:

“ * # * Solely because of their race, the petitioners

here have been refused the use of city-owned or oper

ated parks and other recreational facilities which the

Constitution mandates be open to their enjoyment on

equal terms with white persons. The city has effected,

continues to effect, and claims the right or need to pro

long patently unconstitutional racial discrimination

violative of now long-declared and well-established

rights. The claims of the city to further delay in

affording the petitioners that to which they are clearly

and unquestionably entitled cannot be upheld except

upon the most convincing and impressive demonstra

tion by the city that such delay is manifestly com

pelled by constitutionally cognizable circumstances

warranting the exercise of an appropriate equitable dis

cretion by a court. In short, the city must sustain an

extremely heavy burden of proof.

“ Examination of the facts of this case in light of

the foregoing discussion discloses with singular clarity

that this burden has not been sustained; . . . ” Page 7

# # * * #

“In support of its judgment, the District Court also

pointed out that the recreational facilities available for

Negroes were roughly proportional to their number

3 Although the plan was not part of the record in the case, it

was described in oral argument before the Court of Appeals. The

plan did not provide for complete desegregation of all facilities

until 1971. Watson v. City of Memphis, supra f /n 1.

Opinion and Order

29a

and therefore presumably adequate to meet their needs.

While the record does not clearly support this, no more

need be said than that, even if true, it reflects an im

permissible obeisance to the now thoroughly discredited

doctrine of ‘separate but equal.’ The sufficiency of

Negro facilities is beside the point; it is the segregation

by race that is unconstitutional.” Page 11

The Court remanded the case for proceedings in accord

ance with the opinion.

Applying the Watson case to the facts presented here,

there can be only one decision. Under the facts stated above

and the decision which must be reached herein, there is no

necessity in ruling on the various motions as between the

plaintiffs and the original defendants except the motion for

summary judgment. Under the existing facts, there are

no remaining issues to be passed upon which would or

could affect the outcome of this case. The plaintiffs were

denied admission to two of the State Parks operated by

the State of South Carolina solely because of their race

in accordance with the statutory law of South Carolina.

There can be no racial discrimination in the operation

of State owned or operated recreational facilities. Wat

son v. City of Memphis, supra. The plaintiffs and all

other Negroes similarly situated are entitled to use

the State Parks of South. Carolina in the same man

ner and to the same extent as are white persons.

The statutory laws set out above which require separate

parks for the use of white citizens and Negro citizens are

in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United

States Constitution.

The plaintiffs’ motion for summary judgment under Rule

56 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure must be granted.

Opinion and Order

30a

The record reflects that in the opinion of the officers of

the Commission of Forestry and the South Carolina Law

Enforcement Department, the desegregation of the South

Carolina parks will drastically affect the police protection

required at the various parks and in their opinion the de

segregation will result in serious racial strife at the parks.

Some affiants stated that they believe it would be necessary

to close the parks if they were desegregated. To a similar

argument in the Watson case, the United States Supreme

Court said: “ * * * The compelling answer to this conten

tion is that constitutional rights may not be denied simply

because of hostility to their assertion or exercise.” Page 8

(citations of cases omitted) The Court cannot, however,

ignore the fact that long standing customs are not changed

without planning, education, leadership and foresight. Con

sidering the far reaching consequences of this decision upon

the State of South Carolina, it is manifest that the State

must be allowed a reasonable opportunity to staff these

facilities with properly trained joersonnel and police officers

so that the transition of the State Parks from a segregated

system to an integrated one may be carried out in an

orderly manner.

The Answer of the Intervenor, Davis Lee, does not and

could not affect the outcome of this case. Lee’s motion to

bring in additional parties and to file a counterclaim against

the plaintiffs and the additional parties attempts to create

issues which are foreign to the present action and to gain

jurisdiction of parties over which this Court does not

now have jurisdiction. Mr. Lee may pursue his alleged

cause of action in a separate suit against any parties who

may have committed unlawful acts against him. His mo

tions to bring in additional parties and to file a counter

claim are hereby denied.

Opinion and Order

31a

Opinion and Order

Order

I t is h e r e b y o r d e r ed that the South Carolina Commis

sion of Forestry be enjoined and restrained from discrim

inating against the plaintiffs and all other Negroes simil

arly situated in using the State Parks of South Carolina

solely because of their race.

I t is f u r t h e r o r d e r e d , that the State of South Caro

lina and the South Carolina Forestry Commission be en

joined and restrained from enforcing §§ 51-2.1, 51-2.2,

51-2.3 and 51-2.4 of the South Carolina Code (1962).

I t is f u r t h e r o r d e r ed that this Order become effective

sixty days from date.

J. Robert Martin, J r .

United States District Judge

A T rue Copy, A ttest.

T ho. A . Cauthen

Clerk of U. S. District Court

East. Dist. So. Carolina

(Seal)

Greenville, S. C.

July 10, 1963.

32a

Notice of Appeal

(Filed: August 5, 1963)

Notice is hereby given that Davis Lee, defendant by

intervention, above named, hereby appeals to the United

States Court of Appeals for The Fourth Circuit from the

Order and final judgment signed and issued by Judge J.

Robert Martin in the above cause, July 10th, 1963.

Davis L ur

Defendant by Intervention—

Appellant and Counsel

407 Butler Street

Anderson, South Carolina

38