Shaw v Hunt Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1994

44 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Shaw v Hunt Jurisdictional Statement, 1994. b960ede6-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/82060824-b203-457a-b35e-a135a4eaa2c3/shaw-v-hunt-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed January 31, 2026.

Copied!

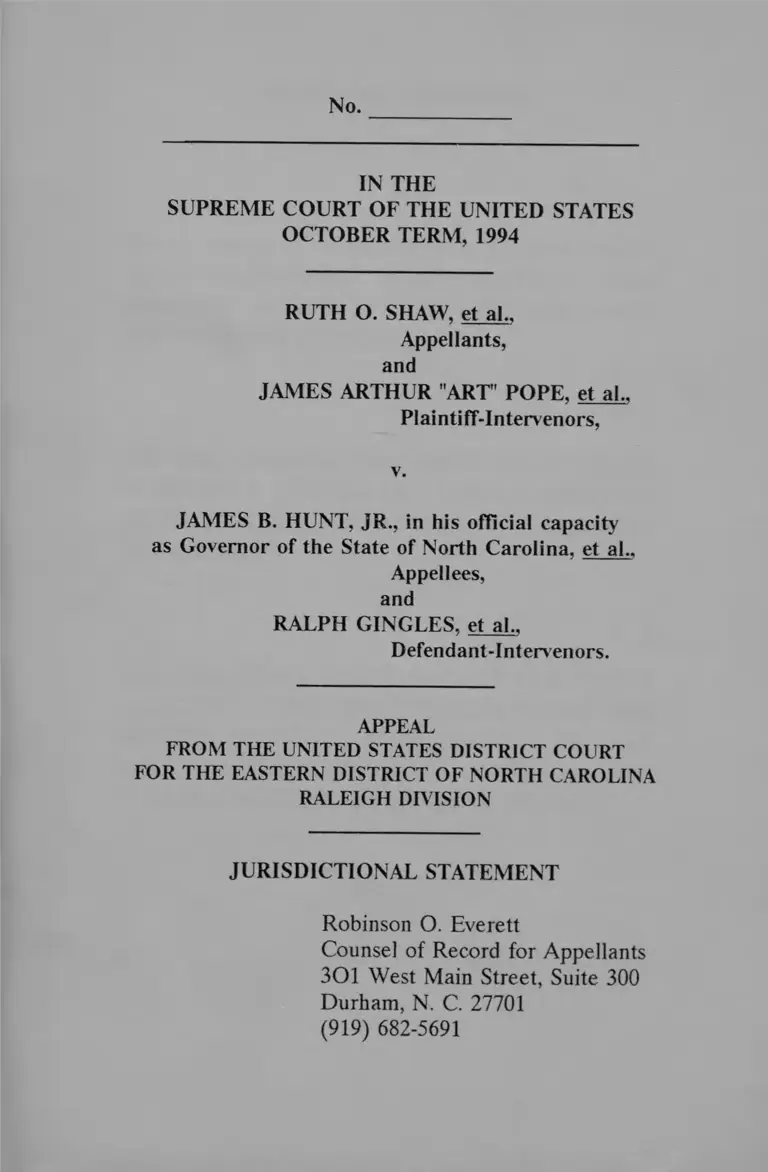

No.

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1994

RUTH O. SHAW, et al..

Appellants,

and

JAMES ARTHUR "ART" POPE, et al..

Plaintiff-Intervenors,

v.

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., in his official capacity

as Governor of the State of North Carolina, et al..

Appellees,

and

RALPH GINGLES, et al..

Defendant-Intervenors.

APPEAL

FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALEIGH DIVISION

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Robinson O. Everett

Counsel of Record for Appellants

301 West Main Street, Suite 300

Durham, N. C. 27701

(919) 682-5691

1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I

WAS N O R T H C A R O L IN A ’S R A C IA L L Y

GERRY M A N D ERED RED ISTRICTIN G PLAN

ENACTED WITHOUT A COMPELLING STATE

INTEREST FOR DOING SO?

II

DID THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY ENACT NORTH

CAROLINA’S RACIALLY GERRYMANDERED

REDISTRICTING PLAN WITHOUT NARROWLY

TAILORING IT?

Ill

DID THE COURT BELOW NEGATE THE "STRICT

SCRUTINY" TEST BY MISALLOCATING THE

BURDEN OF PERSUASION, RELYING ON POST

HOC RATIONALIZATIONS, AND MAKING

CLEARLY ERRONEOUS FINDINGS OF FACT?

THE PARTIES

Appellants, Plaintiffs in the action below, are as

follows:

RUTH O. SHAW, MELVIN G. SHIMM, ROBINSON O.

EVERETT, JAMES M. EVERETT, and DOROTHY

BULLOCK.

Plaintiff-Intervenors in the action below, are as

follows:

JAMES ARTHUR "ART" POPE, BETTY S. JUSTICE,

DORIS LAIL, JOYCE LAWING, NAT SWANSON,

RICK WOODRUFF, J. RALPH HIXON, AUDREY

McBANE, SIM A. DELAPP, JR., RICHARD S.

SAHLIE, and JACK HAWKE, Individually.

Defendants in the action below, are as follows:

JAMES M. HUNT, JR., in his official capacity as

Governor of the State of North Carolina; DENNIS A.

WICKER, in his official capacity as Lieutenant Governor

of the State of North Carolina, and President of the

Senate; DANIEL T. BLUE, JR., in his official capacity as

Speaker of the North Carolina House of Representatives;

RUFUS L. EDMISTEN, in his official capacity of

Secretary of the State of North Carolina; THE NORTH

CAROLINA STATE BOARD OF ELECTIONS, an

official agency of the State of North Carolina; EDWARD

J. HIGH, in his official capacity as Chairman of the North

Carolina State Board of Elections; JEAN H. NELSON,

in her official capacity as a member of the North Carolina

ii

Ill

State Board of Elections, LARRY LEAKE, in his official

capacity as a member of the North Carolina State Board

of Elections, DOROTHY PRESSER, in her official

capacity as a member of the North Carolina State Board

of Elections, and JUNE K. YOUNGBLOOD, in her

official capacity as a member of the North Carolina State

Board of Elections.

and

Defendant-Intervenors in the action below, are as

follows:

RALPH GINGLES, VIRGINIA NEWELL, GEORGE

SIMKINS, N. A. SMITH, RON LEEPER, ALFRED

SMALLWOOD, DR. OSCAR BLANKS, REVEREND

DAVID MOORE, ROBERT L. DAVIS, C. R. WARD,

JERRY B. ADAMS, JAN VALDER, BERNARD

OFFERMAN, JENNIFER McGOVERN, CHARLES

LAMBETH, ELLEN EMERSON, LAVONIA ALLISON,

GEORGE KNIGHT, LETO COPELEY, WOODY

CONNETTE, ROBERTA WADDLE, and WILLIAM M

HODGES.

IV

QUESTIONS PRESEN TED ................ ............. i

PARTIES IN THE COURT B ELO W ............. ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS.................................... iv

TABLE OF A U TH O R ITIES.............................. v

OPINIONS B ELO W ............................................. 1

JURISD ICTIO N .................................................... 2

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

AND STATUTES INVOLVED.................... 2

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E .......................... 3

THE QUESTIONS PRESENTED ARE

SUBSTANTIAL................................................ 6

I. The Evidence Clearly Reveals That

North Carolina’s Racially Gerrymandered

Redistricting Plan Did Not Further A

"Compelling State Interest"........................ 9

II. North Carolina’s Redistricting Plan

Was Not "Narrowly Tailored"................. 23

III. The District Court Misallocated

The Burden Of Persuasion

And Relied Erroneously On

Post Hoc Rationalizations........................ 28

CONCLUSION........................................................ 30

APPENDIX OF CONSTITUTIONAL

AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS.............. A-l

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES:

Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986)............ 23

Board o f Education o f Kiryas Joel Village

School District v. Grumet,

114 S.Ct. 2481 (1994)...................................... 18

Dolan v. City o f Tigard, 114 S.Ct. 2309

(1994)......................................................................... 24

Growe v. Emison, 507 U.S.___,

113 S.Ct. 1075 (1993)............................................... 16

Hays v. Louisiana, 839 F.Supp. 1188

(W.D.La. 1993), vacated, Louisiana

v.. Hays, 114 S.Ct. 2731 (1994)

adopted by reference, Hays v.

Louisiana, No. 92-1522 (W.D.La. 1994)..... 8,9,14,30

J.E.B. v. Alabama ex rel T.B., 114 S.Ct.

1419 (1994).............................................................. 18,23

Johnson v. DeGrandy, 114 S.Ct. 2647

(1994)................................................................... 14,16

Johnson v. Miller, No. 194 - 008

(S.D.Ga. Sept. 12, 1994)........................................ 8,14

Page

VI

Kassel v. Consolidated Freightways Corp.,

450 U.S. 662 (1981)................................ 30

Pope v. Blue, 809 F.Supp. 392

(W.D.N.C.1992) affirmed 506 U.S.___,

113 S.Ct. 30 (1992) ........................................... 4

Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co.,

488 U.S. 469 (2989)........................................... 9,24,28

Shaw v. Barr, 808 F..Supp. 461

(E.D.N.C. 1992)................................................... 4

Shaw v. Reno, 113 S.Ct. 2816 (1993).........................passim

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30

(1986) ...........................................................................16,17

Vera v. Richards, C.A. No. H-94-2077

(S.D.Tex, Aug. 17, 1994)....................................... 3 8

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (Continued)

Page

Vll

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS:

Page

U.S. Const. Art. I, § 2 ........................................... 4

U.S. Const, amend. X IV ...................................... 2,12

U.S. Const, amend. X V ........................................ 2

STATUTES:

2 U.S.C. § 2 (c ) ........................................................ 22

28 U.S.C. § 1253 ..................................................... 2

Section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act of 1965, as amended.

42 U.S.C. § 1973................................... 2,11,14,15,16,17

Section 5 of the Voting Rights

Act of 1965, as amended.

42 U.S.C. § 1973c............................... 2,4,5,11,12,14,24

FED. R. CIV. P. 52(b) 2,6,9

Page

viii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (Continued)

Chapter 7 (1991 Extra Session)

amending North Carolina Election

Code................................................................. 3

N.C.G.S. § 163-11............................................. 19

OTHER:

2 McCormick, EVIDENCE § 337 (4th Ed.

1992)................................................................... 29

Swain, Carol, BLACK FACES,

BLACK INTERESTS (1993)....................... 22

9 Wigmore, EVIDENCE § 2486 (Chadboume

Rev. (1981)......................................................... 29

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1994

No.

RUTH O. SHAW, et al..

Appellants,

and

JAMES ARTHUR "ART' POPE, et al..

Plaintiff-Intervenors,

v.

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., in his official capacity

as Governor of the State of North Carolina, et al..

Appellees,

and

RALPH GINGLES, et al..

Defendant-Intervenors.

APPEAL

FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALEIGH DIVISION

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

OPINIONS BELOW

The judgment and opinion, as amended, of the

three-judge district court are contained in the Appendix

to Jurisdictional Statements filed jointly by these

2

appellants, who were the five original plaintiffs, and by

the eleven plaintiff-inteivenors, who are also appealing

[hereafter "App.J.S."], at pages la to 154a.

JURISDICTION

The district court entered judgment against

appellants on August 1, 1994, and at the same time a

majority opinion was filed, as well as the dissenting

opinion of Chief Judge Voorhees. On August 15, 1994,

plaintiffs filed a motion to amend and add findings

pursuant to Rule 52(b) of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure. On August 22, 1994, amended opinions were

filed by the majority and the dissenting judge in the

district court. On August 29, 1994, plaintiffs filed a notice

of appeal. On September 1, 1994, the district court

denied plaintiffs’ 52(b) motion and on September 15,

1994, the plaintiffs filed a supplemental notice of appeal.

Subsequently, pursuant to Rule 22 of the Rules of the

Supreme Court, the plaintiffs and plaintiff-intervenors

filed a motion applying for a determination that the time

for docketing the appeals in this case, together with the

consolidated single appendix to the jurisdictional

statements of plaintiffs and plaintiff-intervenors, run to

and including November 21, 1994. This motion was

granted by the Chief Justice. This Court has jurisdiction

under 28 U.S.C. § 1253.

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

AND STATUTES INVOLVED

This case arises under the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United

States and involves Sections 2 and 5 of the Voting Rights

3

Act of 1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1973b, 1973c

(1973), which are reprinted in Plaintiff-appellants’

Appendix to this Jurisdictional Statement (pp.Al-A-4).

The appeal concerns the constitutionality of Chapter 7 of

the 1991 Extra Session Laws of North Carolina

(hereinafter "Chapter 7"), the challenged congressional

redistricting statute and amends Chapter 163, Article 17

of the North Carolina General Statutes. Chapter 7 is

reprinted at App.J.S. pp. 169a to 240a. A map of the

Chapter 7 congressional plan was appended to the Court’s

Opinion in the first appeal of this case, Shaw v.

Reno,___U.S.___,113 S.Ct. 2816 (1993) (hereafter "Shaw").

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This appeal from the decision rendered by a

divided three-judge district court raises substantial

questions concerning the constitutionality of the current

North Carolina congressional redistricting plan.1 All three

judges in the court below found this plan to be a racial

gerrymander. However, a majority concluded that the

plan survived "strict scrutiny" because it was "narrowly

tailored to further the State’s compelling interest in

complying with theVoting Rights Act." (App.J.S. at 7a).

That conclusion gave rise to this appeal.

The challenged redistricting plan was enacted by

the General Assembly on January 25, 1992, after an

1 Chief Judge Voorhees’ extensive dissent in the court below

makes obvious the importance of these questions. (App.J.S. at 116a-

154a) See also footnote .55 of Judge Edith Jones’ opinion in Vera v.

Richards, No. H-94-2077 (S.D.Tex. Aug. 17, 1994)

4

earlier plan had been denied preclearance by the Attorney

General pursuant to Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act,

see 42 U.S.C. § 1973c. The current plan first was attacked

unsuccessfully as an unconstitutional political gerrymander

directed against Republicans. Pope v. Blue, 809 F.Supp.

392 (W.D.N.C. 1992), affirmed 506 U.S. _____, 113 S.Ct.

30 (1992). Then on March 28, 1992, the five plaintiff-

appellants filed an action against various Federal and

State officials in which they alleged that the redistricting

plan was an unconstitutional racial gerrymander.

The district court granted motions to dismiss as to

all the defendants, although Chief Judge Voorhees

dissented from the ruling that the plaintiffs had failed to

state a claim for relief against the State defendants. Shaw

v. Barr, 808 F.Supp. 461 (E.D.N.C. 1992). Upon appeal,

this Court upheld the dismissal below of the Federal

defendants; but it decided that, under the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, the five

plaintiffs had stated a claim for relief against the State

defendants. Shaw, supra 2 The case was remanded to the

three-judge court for it to decide whether the redistricting

plan was a racial gerrymander, as the plaintiff-appellants

had alleged, and, if so, whether the plan was justified by

"a compelling governmental interest" and was "narrowly

tailored". (Shaw, 113 S.Ct. at 2832)

Upon remand, the district court allowed twenty-two

registered voters from various congressional districts to

intervene as defendants. Eleven other registered voters

2 The Court did not find it necessary to decide whether plaintiffs

had also stated a claim for relief under Article I, § 2 of the

Constitution or under the Fifteenth Amendment.

5

were permitted to intervene as plaintiffs.3 Extensive

discovery then commenced with defendants taking the five

plaintiffs’ depositions; and thereafter the various parties

deposed numerous experts, as well as some legislators and

lay witnesses. In some instances, discovery was limited by

an order of the district court which recognized a

"legislative privilege" on the part of the General

Assembly’s members and staff.

After discovery had been completed, the plaintiff-

intervenors moved to enjoin the defendants from

conducting any further election under the current

redistricting plan. Over Chief Judge Voorhees’ dissent,

the motion was denied. Likewise, the plaintiffs failed in

their motion in limine to prevent the defendants from

offering evidence based on census data and socioeconomic

information which had not become available until January

1993 - a year after enactment of the redistricting plan.

On March 28, 1994, a six-day trial commenced, at

which each of the four groups of parties was allowed to

call one expert and one lay witness, as well as to offer in

evidence extensive stipulations, depositions, and other

documentary evidence.4 On August 1, 1994, judgment was

entered for the defendants with Chief Judge Voorhees

3 Jack Hawke, the Chairman of the Republican Party of North

Carolina, was allowed to intervene individually as a plaintiff, but not

in his official capacity.

4 Also, at a computer workstation the three judges viewed a

demonstration of how computer technology and census bloc

information had been used together to draw the boundaries of

congressional districts in North Carolina.

6

dissenting; and majority and dissenting opinions were

filed. On August 22, 1994, amended opinions were filed.

Meanwhile, the plaintiffs had moved to amend and add

findings pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(b); but this motion

was denied on September 1, 1994 — again over the dissent

of Chief Judge Voorhees. Plaintiffs and plaintiff-

intervenors all duly filed notices of appeal.

THE QUESTIONS PRESENTED ARE

SUBSTANTIAL

On their prior appeal, the five plaintiff-appellants

presented squarely to this Court the question of whether

they could attack a racially gerrymandered redistricting

plan which had been enacted by the General Assembly in

order to assure that two African-Americans would be

elected to Congress from North Carolina. Reversing the

majority decision of the three judges, this Court ruled

that, as registered voters, the plaintiffs - regardless of

their race — had stated a claim for relief. However, upon

remand, it would be necessary for them to prove their

allegations at trial; and, if they did so, the plan would be

subject to "strict scrutiny" to "determine whether the

North Carolina plan is narrowly tailored to further a

compelling governmental interest". (113 S.Ct at 2832)

By m eans of overwhelming direct and

circumstantial evidence - and over the defendants’

stubborn opposition5 - the plaintiffs convinced all three

5 During the oral argument before this Court, Mr. Powell, who

represented the State defendants, responded to a question from the

Court: "There’s no dispute here over what the State’s purpose is.

(continued...)

7

judges of the court below that the redistricting plan is a

racial gerrymander. Moreover, the district court properly

interpreted Shaw to mean that voters of all races have

standing to attack North Carolina’s racial gerrymander.6

5(...continued)

There’s a dispute over how to characterize it legally, but we’re not in

disagreement over what the State legislature was trying to do"

(Transcript of Oral Argument at p.38). As plaintiff-appellants

interpreted this statement, the State conceded that the redistricting

plan was a racial gerrymander, but contended that such a

gerrymander was constitutional. Nonetheless, upon remand, the

defendants hotly contested that a racial gerrymander had been

enacted.

6 The evidence at trial made clear that plaintiffs Shaw and

Shimm, who reside in the Twelfth Congressional District, not only

have suffered injury to their "personal dignity" by being assigned to

vote on a racial basis but also have suffered other injury. The shape

of the "bizarre" district in which they have been placed reflects its

purpose to guarantee that an African-American will be elected to

Congress; and white voters like plaintiffs Shimm and Shaw perceive

that the Representative elected from the district is "more likely to

believe [his] primary obligation is to represent only "African-

Americans:. See Shaw, 113 S.Ct. at 2832. This perception of having

"second class status" discourages these voters from participating

actively in congressional primaries and elections. [Transcript 1089-

1090 (Shimm Testimony)]. The correctness of their perception was

corroborated recently when Twelfth District Congressman Melvin

Watt stated during a panel discussion "that it adds to the debate to

be able to bring up a perspective without catering, or having to cater

to the business or white community." [Transcript p. 999, (Watt

Testimony)] (emphasis supplied). [See also footnote 5 of Chief Judge

Voorhees’ dissent, (App. J.S, 128a)] Congressman Watt’s mindset is

also revealed by his statement on the McNeilll-Lehrer television

program that he had "characterize^] Justice O’Connor’s opinion in

Shaw as "racist". [Transcript 995 (Watt Testimony)]. Plaintiffs Shaw

(continued...)

8

Consequently, the district court was required to apply the

"strict scrutiny" test to the gerrymander; and its

misapplication of that test presents on this appeal the

substantial and important questions of what constitutes a

"compelling State interest" and when a racially

gerrymandered plan is "narrowly tailored".7

This appeal also presents substantial and important

questions about the methodology employed by the court

below in applying the "strict scrutiny" test. Paradoxically,

the burden was placed on the plaintiffs of persuading the

factfinders that there was no "compelling State interest"

and that the gerrymander was not "narrowly tailored"

(App.J.S. 42a-43b). Furthermore, despite an extensive

legislative record to the contrary, the majority in the

district court accepted "post hoc rationalizations" in

assuming the presence of a legislative intent which could

6(...continued)

and Shimm, along with all other voters in the Twelfth District, were

specially injured by being placed in that district because its confusing

boundaries and its bisecting of several Metropolitan Statistical Areas

(MSA’s) and media markets make the district "dysfunctional".

[Transcript pp. 209, 219-220, 232 (O’Rourke Testimony)]

7 The importance of these questions is underscored by the fact

that three-judge district courts in Louisiana, Texas, and Georgia have

also been recently required to apply the "strict scrutiny" test to racially

gerrymanderered congressional redistricting plans. [See Hays v.

Louisiana, 839 F.Supp. 1188 (W.D.La. 1993) (Hays I) vacated,

Louisiana v. Hays, 114 S.Ct. 2731, adopted by reference, Hays v.

Louisiana, (Hays II) No. 92-1522 (W.D.La. 1994); Vera v. Richards,

supra, n.l; Johnson v. Miller, No. 194-008 (S.D.Ga. Sept.12, 1994)

9

not possibly have existed.8 This Court should decide

whether these evidentiary rulings were contrary to the

spirit and purpose of the "strict scrutiny" test.9

I. The Evidence Reveals Clearly that

N o r t h C a r o l i n a ’ s R a c i a l l y

Gerrymandered Redistricting Plan Did

Not Further A Compelling State Interest.

Having found on remand that the plaintiffs had

proved the redistricting plan to be a racial gerrymander,

the three-judge district court should have subjected it to

"strict scrutiny". Shaw, supra\ c f Richmond v. J.A.

Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469 (1989). Unfortunately, only

Chief Judge Voorhees applied this test correctly - while

the majority below ignored undisputed evidence which

demonstrated the absence of any "compelling State

interest".

The majority’s first mistake was in stating the issue

to be whether the State "had a compelling interest in

enacting any race-based redistricting plan" — rather than

"enacting the particular race-based redistricting plan under

challenge" (App.J.S. at 43a-44a) (emphasis in original). In

this way, the burden to be carried by the State was

8 The majority inferred the legislative intent from census data

and socioeconomic information which only became available a year

after Chapter 7 was enacted. This technique for determining

legislative intent was criticized in Hays I, supra, n.7

9 The erroneous evidentiary rulings in the court below led to

clearly erroneous findings. Plaintiff-appellants attempted to clarify

the record for appellate review by moving under Rule 52(b) to amend

and add findings; but this motion was denied.

10

reduced far below what Shaw had in mind in requiring

that "strict scrutiny" be given to racial gerrymanders.

Under Shaw it should be immaterial that the State

might be able to imagine a "compelling governmental

interest" in enacting some hypothetical redistricting plan —

such as a plan which is "race-based" in that it seeks to

avoid splitting neighborhoods in which African-Americans

or Native Americans are concentrated. The real question

that the court below should have answered was whether

North Carolina had a "compelling governmental interest"

in enacting a redistricting plan which, in order to create

two majority- black districts and guarantee the election of

two African-Americans to Congress, ignored traditional

redistricting principles, such as compactness,

contiguousness, communities of interest, and maintenance

of the integrity of political subdivisions. On the evidence

at trial, the answer to that question should have been in

the negative.10

The majority in the court below stretches the facts

in a vain attempt to give an affirmative answer to its

misleading question whether "any race-based redistricting

plan" could have been justified by "the State’s compelling

interest in complying with the Voting Rights Act".

(App.J.S. 7a, 44a-57a) According to its version, after the

10 It is doubtful that any state interest could be so "compelling"

as to permit the total disregard of traditional redistricting principles

which is manifested by the North Carolina racial gerrymander. Shaw

indicates that a majority-black district can only be created when the

State "employs sound districting principles" and only when the

affected racial group’s "residential patterns offer the opportunity of

creating districts in which they will be in the majority". 113 S Ct

2832.

11

first redistricting plan was denied preclearance, the

General Assembly "reasonably concludefd], after

conducting its own independent reassessment of the

rejected plan in light of the concerns identified by the

Justice Department, that the Justice Department’s

conclusion is legally and factually supportable". (App.J.S.

at 54a)

From the summer of 1991, when the first

redistricting plan was enacted, until after it was denied

preclearance on December 18, 1991, State officials

consistently took the position that the first plan - which

contained only one minority-black district — adequately

complied with the Voting Rights Act. Moreover, even

after the denial of preclearance, a court action in the

District of Columbia was considered by the General

Assembly — until a method was suggested for satisfying

the demands of the Department of Justice and at the

same time protecting Democratic incumbents and

candidates. Clearly the enactment of the redistricting plan

was not the result of a newly-formed belief by the General

Assembly that two majority-black congressional districts

were necessary to comply with Sections 5 and 2. Instead,

the legislature made a tactical choice to accede to

demands by the Attorney General that were generally

perceived as unreasonable.11

11 In their answer, the State defendants alleged that the

Attorney General’s "interpretation of the Voting Rights Act...required

the creation of two majority-minority congressional districts in North

Carolina" (Defendants Answer para.23); that to "comply with Section

2 of the Voting Rights Act, the State was required to enact a

congressional redistricting plan with two majority-minority districts in

(continued...)

12

Shaw recognized that states have an interest "in

complying with federal antidiscrimination laws that are

constitutionally valid as interpreted and as applied." 113

S.Ct. 2830 (emphasis supplied). By negative implication

this statement suggests that a state has no "compelling

interest" in complying with requirements for Section 5

preclearance which far exceed the intent of the Voting

Rights Act and violate the Equal Protection Clause.

Certainly Shaw did not intend to immunize racial

gerrymanders enacted by a legislature which surrendered

to unreasonable interpretations of the Voting Rights Act

by the Attorney General. Otherwise, in practical effect,

the Civil Rights Division could expand the Voting Rights

Act beyond what Congress intended or the Constitution

permitted.12

The undisputed evidence offered at trial makes

clear that the Civil Rights Division was using its

preclearance power under Section 5 to rewrite the Act by

requiring proportionate representation. On January 24,

1992 — the day when the current redistricting plan was

11(...continued)

order to avoid dilution of African-American voting strength". (Ans.

Fifth Defense) In effect, these allegations admit the fact,

demonstrated by uncontradicted evidence, that the General Assembly

enacted the second redistricting plan, because otherwise preclearance

would be denied by the Civil Rights Division and not because of any

"independent reassessment of the rejected plan".

12 Furthermore, a State’s interest in obtaining preclearance from

the Department of Justice is not "compelling", because the State has

available to it the alternative of seeking preclearance in the District

Court of the District of Columbia with direct appeal to the Supreme

Court. 42 U.S.C. § 1973c.

13

enacted — Senator Dennis Winner, the Chairman of the

Senate Redistricting Committee, described to the North

Carolina Senate what had occurred at a meeting that he,

Speaker Daniel Blue, and others had with Assistant

Attorney General John Dunne on December 17,1991, the

day before preclearance had been denied: 13

And I could not figure out why they

called us up there and don’t understand

that to this day. And Mr. Dunne, some

of the staff asked a question or two or

said — made an occasional comment, Mr.

Dunne did most of the talking. The

essence of what he said at that meeting

was - and he said this in different ways

over, and over, and over again -- you

have twenty-two percent black people in

this State, you must have as close to

twenty-two percent black Congressmen,

or black Congressional Districts in this

State. Quotas.

13 See Daily Proceedings in the Senate Chamber for Friday,

January 24, 1992, at p. 4. At his pretrial deposition, Senator Winner

waived his "legislative privilege" and testified that, at the meeting in

Washington on December 17, 1991, Assistant Attorney General

John Dunne had told him and other representatives of the General

Assembly, "that we ought to have a quota system with respect to

minority seats. You had 22 percent blacks in this state. Therefore,

you ought to have as close to that as you could have of congressional

districts. That is really all I remember about it . . . . 1 think his

substance was really that you had - if you had 22 percent blacks in

North Carolina that you ought to have 22 percent minority

congressional seats. Whatever shape didn’t matter." (Winner

Deposition Jan. 11, 1994. pp. 6, 10, 17-19)

14

Senator Winner’s account of the position taken by

Assistant Attorney General Dunne is corroborated by the

language of Dunne’s letter of December 18, 1994, denying

preclearance. Also, it fits perfectly with the findings of

other three-judge district courts that the Civil Rights

Division required maximization of majority-black districts

as a requirement for preclearance of redistricting plans in

Louisiana and Georgia. See Hays I, supra; Johnson v.

Miller, supra

Maximization of majority-minority districts is not

required by the Voting Rights Act Johnson v. DeGrandy,

___U .S .__ j 114 S.Cl 2647 (1994). Indeed, as the three-

judge district court explained in footnote 21 of Hays,

supra, the Civil Rights Division’s insistence on

maximization of majority-minority districts not only is

unauthorized by the Voting Rights Act but also

contravenes Section 2’s prohibition of requiring

proportional representation.14 Yet that insistence, to

which the General Assembly of North Carolina

capitulated, was erroneously relied on by the majority in

the court below to find "a compelling State interest" which

overcomes the equal protection rights of the plaintiff-

appellants.15

14 (839 F.Supp. 1196-7, n.21). In his majority opinion in

Johnson v. Miller, supra, Judge Edenfield has described in some detail

the questionable and coercive tactics used by the Civil Rights Division

in its effort to make the Georgia legislature follow a policy of

maximizing majority-black districts.

15 To allow a "Nuremberg defense" and find as a "compelling

interest" that the State was forced to comply with the Section 5

preclearance requirements imposed by the Civil Rights Division tends

(continued...)

15

The majority in the court below also found that the

denial of preclearance caused the General Assembly to

become fearful that any redistricting plan without two

majority-black districts would violate Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973. To this end, the

majority equated the letter of December 18, 1991 denying

preclearance to "an ’administrative finding’ that its

proposed plan violates the anti-discrimination provisions

of the Voting Rights Act, which is sufficient — unless

clearly legally and factually unsupportable — to justify its

adoption of a race-based alternative plan designed to

remedy that violation". (App.J.S. p. 54a, n. 34)

Treating the letter in this manner gives it an effect

not suggested by its language. Moreover, Congress never

intended that a denial of preclearance by the Civil Rights

Division would give rise to a "compelling State interest" in

enacting a racial gerrymander. In any event, the

"administrative finding" by Assistant Attorney Dunne was

"clearly legally and factually unsupportable" because of its

false premise that the maximization of minority-black

districts is required by the Voting Rights Act.

The three preconditions for establishing vote

dilution in multi-member districts in violation of Section

2 are that a minority group be "sufficiently large and

geographically compact to constitute a majority in a

single-member district"; that it be "politically cohesive";

and that "the white majority votje] sufficiently as a block

to enable it...usually to defeat the minorities preferred

15(...continued)

to induce collusion between the Department of Justice and State

legislatures in creating racial gerrymanders.

16

candidates". Johnson v. DeGrandy, supra; Thornburg v.

Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 50-51 (1986). The same

preconditions apply to single-member congressional

districts. Growe v. Emison,501 U.S.____, 113 S.Ct. 1075

(1993).

As this Court recognized in Shaw, the black

population of North Carolina is "relatively dispersed;

blacks constitute a majority of the general population in

only 5 of the State’s 100 counties" (113 S..Ct. at 2820).

Consequently, a congressional redistricting plan would

not violate Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, even if it

contained no majority black districts.16

After enacting the first redistricting plan — which

had only one majority-black district — the General

Assembly contended for months that it complied fully with

Section 2 and that because of the lack of "geographical

compactness" of the black population, Gingles did not

16 In North Carolina the second Gingles precondition is met, for

ninety-five percent or more of the African-American voters are

registered as Democrats and they vote cohesively for black

Democratic candidates. On the other hand, the third precondition is

absent. White voters in North Carolina are less cohesive than blacks

and often are disposed to vote for black candidates against whites.

(Keech Deposition, (passim) For example, in her deposition, (at p.

34) plaintiff Shaw testified in response to defendants’ questions that

in 1982 and 1984 she had voted in the Democratic congressional

primary for an African-American candidate against a white candidate.

As a result of "white crossover", a number of African-Americans have

been nominated or elected for local and state office even when black

voters were not in the majority.

17

apply17 Under these circumstances, the effort by the

majority in the court below to find a "compelling State

interest" in the imagined desire of the General Assembly

to avoid a Section 2 violation is devoid of any factual or

legal basis.

Although the majority purports to invoke various

other "compelling State interests", clearly its real concern

is with the "interest" in guaranteeing greater racial

diversity of North Carolina’s congressional delegation in

order to make reparations for the absence of any black

member of Congress from North Carolina since 1901.

Thus, the majority opinion refers in its "Conclusion" to

"the inability of any African-American citizen of North

Carolina, despite repeated responsible efforts, to be

elected in a century". (App.J.S. at 114a). Consequently,

the question is raised whether, by means of a racial

gerrymander, a state may establish racial quotas for its

congressional delegation because of a "compelling

interest" in rectifying supposed past discrimination.

To use quotas, however, furthers no "compelling

interest" but, instead, leads only to the disaster of

"Balkanization" and racial polarization. Especially when

traditional redistricting criteria are disregarded and

17 As the legislative record shows, Daniel Blue, the Speaker of

the House of Representatives, and 'Toby" Fitch, a co-chairman of

the House’s Redistricting Committee — both of whom are African-

Americans — signed submissions to the Department of Justice which

were intended to make clear that the Gingles preconditions were not

met. In his deposition, Senator Winner stated that it had been his

belief that Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act did not require the

creation of even one minority-black congressional district in North

Carolina.

18

"bizarre" districts are formed, the State sends a clear

message that it accepts and relies on racial stereotypes

and, by so doing, perpetuates and reinforces those

stereotypes and destroys confidence in the electoral

process. Cf., J.E.B. v. Alabama ex rel. T.B., ___U.S.___

114 S.Ct. 1419 (1994) (condemning reliance on gender

stereotypes).18

Furthermore, some of the burden of the quotas

falls upon voters who had no connection with the past

discrimination. Thus, plaintiff Shaw, who moved to North

Carolina from Minnesota, and plaintiff Shimm, who came

from New York, had no part to play in any past

discrimination against blacks in North Carolina;19 and yet,

they have been placed in a dysfunctional minority-black

congressional district, where they correctly perceive that

they have "second-class status" and that their political

participation is discouraged. Indeed, the mobility of the

American population (see Stipulation 146) allows little

relationship to exist between those whites who perpetrated

past discrimination against blacks and those whites

subjected to the burdens of racial gerrymandering — or

between the blacks who were the victims of past

18 The Court seems to be increasingly committed to the view

that States must be neutral with respect to their citizens and groups

of citizens. Cf, Board o f Education ofKiryasJoel Village School District

v. Grumet, __ U.S.___, 114 S.Ct. 2481 (1994) (disapproving

boundaries of school district gerrymandered to further religious

instruction).

19 Ironically, as Professor Shimm testified in his deposition,

members of his family had undergone persecution in the Holocaust;

and he personally had been a victim of discrimination — rather than

a perpetrator.

19

discrimination and those blacks who are now the intended

beneficiaries of racial quotas for political office.

The majority’s rationale also is based on the false

premise that African-Americans can be elected to

Congress from North Carolina only from majority-black

districts. Since approximately 95% of the registered black

voters in North Carolina are Democrats and the

Democrats have closed primaries, a good opportunity

exists for an African-American to obtain the Democratic

nomination and be elected from a district where blacks

are not a majority. In a number of recent elections,

blacks have won local and statewide offices in races

against whites. Moreover, in order to enhance the

opportunity for minority candidates to be elected, the

General Assembly changed the election laws in 1989 to

dispense with a second primary if the leader in the first

primary received more than 40% of the votes cast.

(N.C.G.S. § 163-111; Stipulation 127).

The reference by the majority in the court below

to "repeated responsible efforts" of African-Americans to

be elected to Congress is misleading. The only serious

efforts were in the Second District. The first two of those

efforts by black candidates (Eva Clayton and Howard

Lee) were against an experienced and well-entrenched

incumbent (L. H. Foutain). The more recent efforts were

in 1982, when an African-American candidate (H.M.

Michaux, Jr.) received 46% of the vote in the Democratic

primary in the Second District; 20 and in 1984, when a

20 Under the 1989 change in the election code, H.M. Michaux,

Jr., the African-American, who led in the first primary and received

(continued...)

20

different African-American candidate received 48% of

the vote.21 Under these circumstances, there is ample

reason to believe that in some congressional districts

drawn pursuant to traditional redistricting principles

African-Americans would be elected from North

Carolina.22

Even if it were assumed that blacks can only be

elected to Congress from North Carolina if majority-black

districts are created, the substantial question remains

whether the interest in achieving this diversity is so

"compelling" as to justify the creation of dysfunctional

congressional districts that totally disregard traditional

redistricting principles such as compactness,

contiguousness, communities of interest, and maintaining

the integrity of political subdivisions. In an extensive

footnote, the majority in the court below opines that

"objective evidence" reveals — "perhaps counter-intuitively"

20(... continued)

more than 40% of the vote, would have won the Democratic

nomination.

21 Both African-American candidates were from Durham, and

received many "white crossover" votes from white voters such as

plaintiff Shaw. In 1984, Kenneth Spaulding, the black candidate, ran

against Tim Valentine, who had defeated Michaux two years before

and was now an incumbent. Thus, the increased percentage of the

vote for the African-American candidate is even more significant.

22 In view of the small number of black candidates for Congress

until 1992, it is a fallacy to conclude — as did the majority below —

that blacks could not be elected from North Carolina without a racial

gerrymander. The same logic would lead to the erroneous conclusion

that because women had never been elected to Congress in the past

they could not be elected without the benefit of a quota.

21

— that "bizarre", "ugly" shapes really make no difference

because, in due course, voters will learn who represents

them in Congress. (App.J.S.. at p. 106a, n. 60).

This observation by the majority brushes aside as

irrelevant the evidence at trial concerning confusion on

the part of voters as to their district and their

representative.23 It ignores evidence that, according to a

poll commissioned by the State defendants in the fall of

1993, only 6% of the voters knew who was their

congressman.24 25 It disregards the adverse effects on

"political access" of having districts like the Twelfth -

which is not compact and extends through three

Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSA’s) and three media

markets.-5 Finally, it is at odds with the purpose of

23 For example, the affidavit of David Stradley (Exhibit 104)

describes the confusion in his princinct, the Chambersburg precinct

in Iredell County, which is split among three congressional districts.

The headline "2nd, 12th District lines still unclear for many voters”,

which appeared in the Durham, North Carolina Herald-Sun on

November 9, 1994 (at p.A7), attests to the continuing confusion of

voters about the boundaries of congressional districts.

24 According to the poll, which was commissioned by the State

and conducted in October and November 1993, only 6% of those

polled in the Twelfth District knew that their congressman was Melvin

Watt. On the other hand, 6% believed their congressman was

[Senator] Jesse Helms; 8% believed their congressman was Alex

McMillan [who represented the Ninth District] and 12% believed

their congressmana was Howard Coble, [who represented the Sixth

District], [Transcript at 841-842, 866-869 (Lichtman Testimony)].

25 Professor Timothy O’Rourke explained that a geographically

compact congressional district serves in many ways the interests of

(continued...)

22

2 U.S.C. § 2(c), which requires single-member

congressional districts.26

Implicit in the majority’s opinion is the view that a

state has a compelling interest in guaranteeing "descriptive

representation".27 This view is based on a racial

stereotype — only a black officeholder can adequately

represent blacks28 — that Shaw condemns.29 This Court

25(...continued)

"political access" of voters to their representatives and to candidates

for office. [Transcript, pp. 209-220 (O’Rourke Testimony)]

26 Presumably, the requirement of single-member districts was

imposed in order to enhance "political access" to Representatives.

Congress did not require that a member of Congress reside in the

district from which he or she is elected. However, it probably never

contemplated that — as happened in North Carolina on November 8,

1994 -- Sue Myrick, who resides in the Twelfth District, would be

elected to Congress from the Ninth District (see The Herald-Sun.

Durham, N.C., November 10, 1994 (at C-3) and that Walter Jones,

Jr., who resides in the First District, would be elected to Congress

from the Third District.

27 In her recent book about the representation of black interests

in Congress, Carol Swain, an African-American political scientist,

makes the important distinction between "descriptive representation"

- representation by black officeholders - and "substantive

representation" — representation by someone who advances the

interests of black voters. See Swain, Black Faces. Black Interests.

page 5 (1993).

28 The logical, but equally unacceptable, corollary would be that

only white officeholders can adequately represent the interests of

white voters.

(continued...)

23

should now decide whether Shaw permits reliance on

such racial stereotypes to establish a "compelling State

interest" which justifies a racial gerrymander.

II. North Carolina’s Redistricting Plan

Was Not "Narrowly Tailored"

Even the majority in the court below concedes that

the two majority-black districts "are not the two most

geographically compact., that could have been created

were no factors other than equal population requirements

and effective minority-race voting majorities taken into

account" (Finding 4, AppJ.S. p.KWa).29 30 The ensuing

attempt to excuse this lack of compactness (see Findings

5 and 6) raises substantial questions both as to whether

"narrow tailoring" has been established and as to the

legitimacy of the methodology the majority employed.31

The requirement of "narrow tailoring" suggests the

29(...continued)

29 The rejection of racial stereotypes in Shaw follows a line of

cases stemming from Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986).

Recently, in extending Batson to prohibit gender-based peremptory

challenges, this Court denounced gender stereotypes, J.E.B. v.

Alabama ex rel. T.B., supra.

30 According to a study, North Carolina’s Twelfth District is the

least "geographically compact" out of all 435 districts in the United

States. Moreover, North Carolina has four of the 28 least

geographically compact congressional districts. [Transcript p. 217

(O’Rourke Testimony)].

31 The majority’s dubious methodology is the subject of question

III in this Jurisdictional Statement.

24

need for an effort to match the remedy with the supposed

harm.32 No such effort was made in drawing North

Carolina’s redistricting plan. For example, at the time of

redistricting, blacks in the Twelfth District were registered

to vote at a slightly higher rate (54.71%) than whites

(53.34%). Only two of the ten counties bisected by the

Twelfth District are among the 40 North Carolina

counties which have been subject to preclearance at any

time; and only 73.4% of the voters in the Twelfth District

reside in the eight counties never covered under Section

5. Futhermore, of the forty counties covered under

Section 5, sixteen are outside either the First or Twelfth

District.33

Thus, many of the persons who were subjected to

the most baneful effects of the racial gerrymander did not

reside in the areas where blacks had not been

participating equally in the electoral process when the

Voting Rights Act was enacted. Also, many of the

African-Americans who received the supposed benefits of

being placed in minority-black districts were not those

who at some earlier time had been precluded from equal

political participation. These disparities reflect the

absence of "narrow tailoring".

32 Cf Richmond v. JA. Croson Co., supra. Insistence on this

matching would parallel the imposition of due process requirements

of "essential nexus", "rough proportionality", and "individualized

determination" when property is taken for a paublic purpose. Dolan

v. City o f Tigard,___ U.S.____, 114 S.Ct. 2309 (1994).

33 Because of their proximity to the majority-black districts, 11

of the 16 covered counties could readily have been included in such

districts if the General Assembly had "narrowly tailored" the districts

to remedy past discrimination.

25

The finding by the majority in the district court

that there were "internally homogeneous commonalities of

interest" in the majority-black districts is at odds with the

testimony of defendants’ witness, Gerry Cohen, that the

blacks residing in the major cities of the Twelfth District

"have been tied together with corridors with a requisite

number of whites to meet the one-person, one-vote

standard". 34 Thus, "homogeneity" was equated with race

in a manner condemned by Shaw. Furthermore, the

creation of these "corridors" violated the equal protection

rights of whites by purposefully directing against them the

adverse effects of the fragmentation of precincts and

census blocks.35

The majority’s description of the "homogeneity" of

the "rural" First District is irreconcilable with the

undisputed evidence that the First District divides twelve

towns with a population of 10,000 or more; 36 and the

34 [Transcript at p. 614 (Cohen Testimony)] Cohen played the

major role for the General Assembly in using computer technology to

draw the districts; and he personally operated the computer terminal

utilized for this purpose. Plaintiff-appellants Shaw and Shimm live in

one of the "corridors of whites" to which Cohen alluded.

35 To create two majority-black districts, it was necessary to

divide various precincts and even census blocks. Predominantly white

precincts and census blocks were divided, but predominantly black

were not. [Transcript pp. 496, 613, 614 (Cohen Testimony);

Transcript pp. 94-100, 106, 107, 189, 190 (HofeUer Testimony)] .

36 Fayetteville has a population of 75,928, of which 20, 337

blacks and 5,940 whites were placed in the First District; Greenville

has a population of 45,000, of which 13,197 blacks and 5,082 whites

(continued...)

26

entire legislative record — which was an exhibit at trial --

contains no reference to the "distinctiveness" and

"homogeneity" of the voters placed in the two majority-

black districts.37 Moreover, because the districts were

drawn by use of computer technology to display North

Carolina’s 229,000 census blocks on the computer screen,38 39

and the only data then available concerned race,

"homogeneity" could only be sought by relying on race.

Thus, the majority’s finding as to "homogeneity" of the

districts stems from the very same racial stereotypes which

this Court condemned in Shaw?9

36(...continued)

were placed in the First Disitrict; and from the seaport city of

Wilmington 15,369 blacks and 4,660 whites were placed in the First

District. [Transcript at pp. 609-611 (Cohen Testimony)] Like the

"urban" Twelfth District, the "rural" First District divides twelve towns

with a population of more than 10,000; and for census purposes such

towns are "urban".

37 [Transcript at pp. 1028, 1037, 1041, 1046-1048 (Pope

Testimony)]. If the General Assembly sought to attain "homogeneity",

this goal existed only as to blacks — and not as to whites. Any such

race-based disparity of treatment would itself violate the Equal

Protection Clause.

38 Likewise, the General Assembly computer was used to draft

Chapter 7, the lengthy and detailed redistricting statute. (App.J.S. pp.

169a-240a) A cursory examination of this statute makes obvious that

a legislator would find it impossible to draw any conclusion aabout

the "internal homogeneity" of the twelve districts created by that

statute.

39 The three-judge district court made this point in Hays I.

Moreover, even if greater "homogeneity" in socioeconomic

(continued...)

27

Even if incumbent protection" — another goal of

North Carolina’s racial gerrymander — might sometimes

be a permissible goal of redistricting, it has nothing to do

with remedying past racial discrimination and is at odds

with "narrow tailoring".40 However, the North Carolina

racial gerrymander went beyond "incumbent protection" to

protect Eva Clayton, then only an announced candidate,

by moving Vance County from another district into the

First District. [Transcript at 590, (Cohen Testimony)]

Also, the boundaries were drawn in a way that would

permit two black members of the General Assembly to

run at some future time. [Transcript at 591-592, (Cohen

Testimony)] Indeed, as part of the "narrow tailoring",

the North Carolina House of Representatives transferred

to the First District 131 residents of Wayne County, of

whom 110 were white, in order "to needle the president

pro tempore of the Senate". [Transcript 611 (Cohen

Testimony)]

Some black precincts in Winston-Salem, one of the

largest cities in North Carolina, were at one point to be

included in the majority-black Twelfth District. However,

they were transferred to another district and replaced by

some black populations in a smaller city, Gastonia; and

these were connected to the Twelfth District by a narrow

corridor. [Transcript 977 (Watt testimony)] This change

39(...continued)

characteristics might be attained by grouping persons according to

race, this is not a valid justification for such grouping.

40 Perhaps some of the incumbents being protected had been

elected to office initially as a result of past discrimination against

African-Americans.

28

was at odds with any goal of achieving "homogeneous

communities of interest".41 Once again there is revealed

the absence of the "narrow tailoring" which the Court

referred to in Shaw. Cf. Richmond v. J. A. Croson., supra.

The majority found that the General Assembly

sought to maintain "technical territorial contiguity"

(App.J.S. 109a). This refers to an effort by draftsmen of

the North Carolina plan to comply in form with the

standard of "contiguity" while ignoring it in substance.

For example, in some instances, portions of a North

Carolina congressional district will touch another only at

an imaginary point shown on a computer screen.

Moreover, North Carolina’s plan has employed the unique

and unprecedented device of the "double crossover" — a

single imaginary point at which each of two Districts is

"contiguous". 42 The Court should decide whether under

Shaw such redistricting practices are included within

"narrow tailoring".

III. The District Court Misallocated The

Burden Of Persuasion And Erroneously

Relied On Post Hoc Rationalizations

In their answer, the defendants attempted to allege

41 On the other hand, the transfer favored a black candidate

from the Charlotte area like Melvin Watt. (Ibid.)

42 [Transcript at pp. 212, 276-277 (O’Rourke Testimony)]. For

example, there is a "double crossover" between the First and Third

Districts: no one can go from the eastern to the western part of the

Third District without going through the First District; nor can

anyone go from the northern to the southern part of the First District

without going through the Third District.

29

affirmatively that the redistricting plan was "narrowly

tailored" to further a "compelling State interest"; and the

district court properly imposed on them the burden of

producing evidence as to these defenses. It should also

have placed the burden of persuasion on the defendants,

for usually a party bears this burden as to its affirmative

allegations and as to issues on which it must produce

evidence. See 9 Wigmore, Evidence § 2486 (Chadboume

Rev. 1981); 2 McCormick, Evidence § 337 (4th Ed. 1992).

Still another reason to place the burden of persuasion on

the defendants was because they invoked "legislative

privilege" to prevent plaintiffs from obtaining evidence

about some of the events that preceded enactment of the

racial geriymander by the General Assembly.43 See

Wigmore, supra, § 2486. Under such circumstances,

relieving the defendants of the burden of persuasion as to

"compelling State interest" and "narrow tailoring" is

inconsistent with "strict scrutiny".44

When the redistricting plan was enacted by the

General Assembly in January 1992, it lacked census

43 For example, when defendant Daniel Blue, the Speaker of the

House, who had been active in the redistricting process, was deposed

by plaintiffs, he invoked legislative privilege. When the plaintiffs

subpoenaed former Assistant Attorney General John Dunne to take

his deposition, the United States — an ally of the defendants —

moved to quash the subpoena; and he never testified.

44 In Shaw, the Court commented that the State must have a

"strong basis in evidence for [concluding] that remedial action [is]

necessary". 113 S.Ct. 2832. This comment is inconsistent with

allowing the burden of persuasion to be placed on plaintiffs except to

show that the legislature purposefully created race-based districts

which violate sound redistricting practices.

30

socioeconomic data which only became available a year

later. Therefore, apart from data as to the racial

composition of census blocks, the legislature had no basis

for drawing the exceptionally contorted district lines

detailed in Chapter 7 (App.J.S. 169a-240a). For the

majority to attribute a benign purpose to the drawing of

these lines is a "post hoc rationalization" -- correctly

criticized in Hays I, supra. Under these circumstances it

is "contrary to precedent as well as to sound principles of

constitutional adjudication for the courts to base their

analyses on purposes never conceived by the lawmakers".

See. Kassel v. Consolidated Freightways Corp., 450 U.S. 662,

682 (1981) (Brennan, J. concurring in result).45

CONCLUSION

The majority opinion in the court below is at odds

with the clear meaning of the Court’s milestone opinion

in Shaw. Accordingly, this Court should either summarily

reverse the judgment of the court below, or should note

probable jurisdiction of this appeal.

Respectfully submitted.

Robinson O. Everett

Attorney of Record

for Appellants

301 W. Main Street, Ste. 300

Durham, North Carolina 27701

Tel. (919) 682-5691

Clifford Dougherty

2000 N. 14th St.

Suite 100

Arlington, VA

22201

(703) 536-7119)

45 In their zeal to sustain the redistricting plan by finding a

benign legislative intent,, the majority below made numerous findings

which have no evidence for support or are contrary to the

overwhelming weight of the evidence.

A-l

APPENDIX

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

AND STATUTES INVOLVED

(a) Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States, which provides in

pertinent part:

No state shall make or enforce any law which shall

abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of

the United States; nor shall any State deprive any

person of life, liberty or property, without due

process of law; nor deny to any person within its

jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws;

(b) the Fifteenth Amendment to the constitution of the

United States, which provides in pertinent part:

The right of citizens of the United States to vote

shall not be denied or abridged by the United

States or by any state on account of race, color, or

previous condition of servitude.

(c) Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973

which provides:

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to

voting or standard, practice, or procedure shall be

imposed or applied by a state or political

subdivision in a manner which results in a denial

or abridgement of the right to vote on account of

race or color, or in contravention of the

A-2

guarantees set forth in section 4 (f) (2), as

provided in subsection (b)

(b) A violation of subsection (a) is established if,

based on the totality of circumstances it is shown

that the political processes leading to nomination

or election in the state or political subdivision are

not equally open to participation by members of

a class of citizens protected by subsection (a), and

that its members have less opportunity than other

members of the electorate to participate in the

political process and to elect representatives of

their choice. The extent to which members of a

protected class have been elected to office in the

state or political subdivision is one circumstance

which may be considered: Provided, That nothing

in this section establishes a right to have members

of a protected class elected in numbers equal to

their proportion in the population.

(d) Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U. S.C. §

1973c which provides:

Whenever a State or political subdivision with

respect to which the prohibitions set forth in

section 1973(a) of this title based upon

determinations made under the first sentence of

section 1973b(b) of this title are in effect shall

enact or seek to administer any voting

qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard,

practice, or procedure with respect to voting

different from that in force or effect on November

1, 1964, or whenever a State or political

subdivision with respect to which the prohibitions

A-3

set forth in section 1973b(a) of this title based

upon determinations made under the second

sentence of section 1973b(b) of this title are in

effect shall enact or seek to administer any voting

qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard,

practice, or procedure with respect to voting

different from that in force or effect on November

1, 1968, or whenever a State or political

subdivision with respect to which the prohibitions

set forth in section 1973b(a) of this title based

upon determinations made under the third

sentence of section 1973b(b) of this title are in

effect shall enact or seek to administer any voting

qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard,

practice, or procedure with respect to voting

different from that in force or effect on November

1, 1972, such State or subdivision may institute an

action in the United States District Court for the

District of Columbia for a declaratory judgment

that such qualification, prerequisite, standard,

practice, or procedure does not have the purpose

and will not have the effect of denying or

abridging the right to vote on account of race of

color, or in contravention of the guarantees set

forth in section 1973b(f)(2) of this title, and unless

and until the court enters such judgment no

person shall be denied the right to vote for failure

to comply with such qualification, prerequisite,

standard, practice, or procedure; Provided, That

such qualifications, prerequisite, standard,

practice, or procedure may be enforced without

such proceeding if the qualification, prerequisite,

standard, practice, or procedure has been

submitted by the chief legal officer or other

A-4

appropriate official of such State or subdivision to

the Attorney General and the Attorney General

has not interposed an objection within sixty days

after such submission, or upon good cause shown,

to facilitate an expedited approval within sixty

days after such submission, the Attorney General

has affirmatively indicated that such objection will

not be made. Neither an affirmative indication by

the Attorney General that no objection will be

made, nor the Attorney General’s failure to

object, nor a declaratory judgment entered under

this section shall bar a subsequent action to enjoin

enforcement of such qualification, prerequisite,

standard, practice, or procedure. In the event the

Attorney General affirmatively indicates that no

objection will be made within the sixty-day period

following receipt of a submission, the Attorney

General may reserve the right to reexamine the

submission if additional information comes to his

attention during the remainder of the sixty-day

period which would otherwise require objection in

accordance with this section. Any action under

this section shall be heard and determined by a

court of three judges in accordance with the

provisions of section 2284 of title 28 and any

appeal shall lie to the Supreme Court.