Lupper v. Arkansas Oral Argument

Public Court Documents

October 12, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lupper v. Arkansas Oral Argument, 1964. 8ca6fb16-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8293a936-b44a-4f94-a7a4-93a0f2a46da2/lupper-v-arkansas-oral-argument. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

1

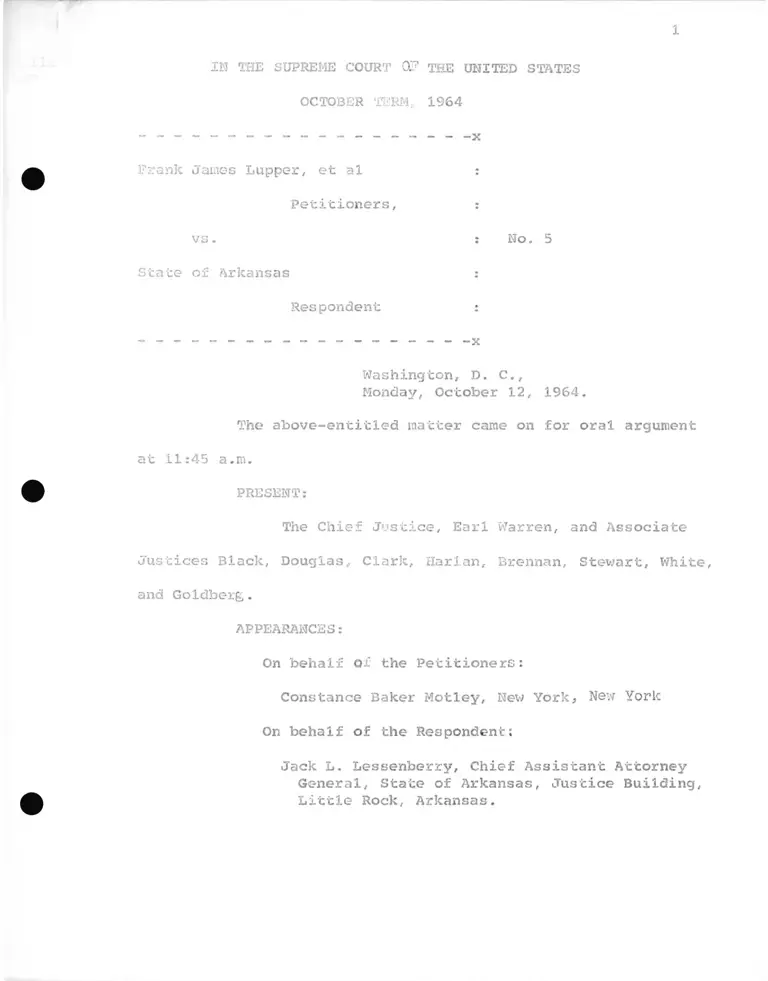

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1964

x

Frank James Lupper, et al

Petitioners,

v s .

State of Arkansas

No- 5

Respondent

Washington, D. C.,

Monday, October 12, 1964.

The above-entitled matter came on for oral argument

at 11:45 a.m.

PRESENT:

The Chief Justice, Earl Warren, and Associate

Justices Black, Douglas, Clark, Harlan, Brennan, Stewart, White,

and Goldberg.

APPEARANCES:

On behalf Of the Petitioners:

Constance Baker Motley, New York, New York

On behalf of the Respondent:

Jack L. Lessenberry, Chief Assistant Attorney

General, State of Arkansas, Justice Building,

Little Rock, Arkansas.

5

said the people have argued this was already in the Fourteenth

Amendment. And so in the Senate, I understand, that was specific

ally taken up. And tint appears on page 31 of our brief. In

the Senate there was this change made from the words "hereby

created" — it was changed to,"based on this title," which would

seem to indicate that there v?as some real notion that here were

rights which were preexisting which were being protected now

specifically.

JUSTICE WHITE: Then I suppose if your preemption or

Federal supremacy argument to abate these actions is to succeed,

then I suppose you are saying that the Court must decide whether

there was a right to service in these establishments prior to

the passage of the Act.

MRS. MOTLEY: No.

JUSTICE WHITE: Otherwise Section 203 does not reach

your argument. Section 203 says no one will interfere or try to

punish anyone for exercising a right secured by 201 or 202.

Well, if the .right under those two sections is created with the

passage of the Act, these particular defendants were not exercis

ing any rights secured by Section 201 and 202. These defendants

in these cases, they committed their act before the Act was

passed.

MRS. MOTLEY: If I can answer the question, these

defendants were exercising a right now secured by this Act, and

203 now prohibits the infliction of the punishment which has not

6

yet been inflicted, that is, the prison term and the $500 fine.

JUSTICE WHITE: The Act says you shall not punish

anyone for doing an act which before the statute he had no right

to do but after the statute he has a right to do. Is that the

meaning of 202?

MRS. MOTLEY: Yes, I would say so.

As in the preceding case, these petitioners also con

tend that Title II mandates a referral of the judgments below,

and a remanding of these cases for dismissal as a matter of

Federal law pursuant to the unique legislative phenonemen rule

enunciated by this C ourt in Bell against Maryland, and in accord

ance with the express terms of Section 203(c) of Title II, which

we have just referred to, permitting punishment for exercising

the right to equal treatment in places of public accommodation.

The argument just made by Mr . Greenberg, of course, in

the preceding case with respect to this we adopt. But I would

like to point out that Arkansas, like Maryland, and unlike South

Carolina, does have a saving clause statute. In fact, they have

two which relate to this problem. And these statutes appear on

pages S and 7 of our brief.

Unlike Maryland, however, these Arkansas statutes

refer only to repeal of any criminal or penal statute. Conse

quently, if this Court, for some reason, should not agree with

petitioner’s argument that Title II has the effect of compelling

a reversal of these convictions as a matter of Federal lav; and

9

case.

MRS. MOTLEY: Yes.

JUSTICE HARLAN: And therefore of course you could

have different interpretations.

MRS. MOTLEY: Yes, the courts could interpret it

differently, yes.

JUSTICE GOLDBERG: That is an alternate argument.

MRS. MOTLEY: Yes, sir.

If, as respondents claim, Arkansas — to further

expand on this point -- if, as respondents claim, Arkansas has now

set its face against its officially segregated past and has now

turned for the future, free from state-imposed racial segregation

in the public life of that state, then certainly this new state

policy might be taken into consideration by the Supreme Court

of the state upon a remand of these cases to chat court to deter

mine the effect of Title II on these convictions.

But as Mr. Greenberg has already argued, this remand

for state court consideration of the effect of Title II is

entirely unnecessary, and there is ample Federal authority and

necessity for remand for dismissal by this Court.

Petitioners here argue, as did petitioners in Bell

against Maryland, that their convictions violate the equal pro

tection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment since their convic

tions enforce racial discrimination in violation of that clause.

THE CHIEF JUSTICE: We will recess.

11

11 be-applicable,, and under state law they would abate.

And the State of South Carolina could not discriminate against a

Federal law.

In Arkansas, on the other hand, there is a saving

statute, and therefore it is a question of statutory interpreta

tion.

If repeal means the same thing as repeal in the

Federal statutes, then the Supreme Court of Arkansas might hold

that these convictions abate because there is no statute saving

the punishment. If not, then the proceedings do not abate, and

of course that would be a question of state lav; — under the law

of the state they would not abate, and then we could not come

back here on that question, although of course we have other ques

tions, Constitutional questions, dealing with protection and so

forth, which we argue.

JUSTICE BRENNAN: Senator Motley, what have you to

say about the record indicating coverage of this establishment?

MRS. MOIAEY; Well, in this case, as in the preceding

case, the record is clear that this was a department store.

JUSTICE BRENNAN: Locally owned, was it not?

MRS. MOTLEY: Pardon me?

JUSTICE BRENNAN: The record does not show it was one

of these national chains.

MRS. MOTLEY: No, it does not. It appears to be

locally owned. There is no testimony on that question. But

12

it is a department store, and one or the petitioners testified

that he had been a customer there for some time and that his

mother had an account there for nineteen or twenty years. It

was therefore a place open to the public, and our position is

chat open to the public includes all of the public and is there

fore covered by the Civil Rights Act, because it is a place which

serves the public.

JUSTICE GOLDBERG: Mrs. Motley, can you clear up a

factual discrepancy which appears in the two briefs here and

give us vour version as to actually what happened on che facts.

They went to the lunch/■ counter and asked to be

served. The manager said they could not be served. How long,

according to your version, did they remain at the lunch counter,

and when the police came it appears they were going out of the

store — and that is challenged. Would you just enlighten us

a little on the facts of this case?

MRS. MOTLEY: Yes. It appears chat these petitioners

went to the lunch counter and they were approached by the manager,

and the assistant manager. The manager merely says he told them

he did not want any disturbance and they would have to leave.

Then the assistant manager testified that he approached the boys

at the lunch counter and spoke to one -- not one of these peti

tioners but one in the group — and said, "Well, we are just not

prepared to serve you now. Would you excuse yourself meaning

move away from the counter.

13

The manager went outside of the store and got the

police officers and came back. The police officers had already

been called by another police officer who had observed these

petitioners going into the store and observed them seating them

selves at the counter, and ran out co call the police headquarters,

which apparently was not too far away, because when the manager

came out, there were the two policemen across the street.

The manager came back in with the two police officers

and there were the petitioners walking out towards the front

door. The police officers said, "Are you the two men?*’ And

the manager identified them as being among the five which he saw

at the lunch counter. And that was when they arrested them.

Now—

JUSTICE GOLDBERG: How much time elapsed in this

whole period?

MRS. MOTLEY: There is no direct testimony as to

how much time actually elapsed. But it does appear that it was

just a few minutes, two to five minutes — I believe the manager

testified it cook him to go over and come back into the store.

JUSTICE GOLDBERG: But the whole episode obviously

must have lasted longer. Does this account for the half

hour that the statement refers to?

MRS. MOTLEY: Yes, that”s right. From the time they

came into the store initially, when they were on their way out —

the whole business cook place sometime between 11:30 and 12:00.

14

No one knows the exact time. But the going out and getting the

police was apparently just a couple of minutes.

Now, before — I will come back to those facts when

I get to our due process argument. But I did want to say a word

about our equal protection argument.

We argued here, as petitioners in Beil and the other

cases decided last term, that these convictions violate the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, since these con

victions enforce racial discrimination in violation of that

clause. The came constitutionally relevant reasons which we

urged so extensively and so exhaustively in Bell for reaching

this conclusion have been succinctly repeated in our brief here

at pages 46 to 69.

G'USTICE STEWART: That is basically the Shelley against

Kraemer argument?

MRS. MOTLEY: Yes. And our custom argument and our

regime of law argument. These arguments were made until very

recently to this Court last term and the Court's decision in

Bell evidences that this Court is thoroughly familiar with our

intentions in this regard —— that we would like to not argue

that really extensively here today. However, I think it should

be noted again that since the granting of certiorari in these

cases and this court's decision in Bell, we now have a Federal

legislative prohibition against enforcement of the custom of

segregation by the states, which we did not have before when

16

It is like the situation in Shelley against Kraeraer.

We had a specific Federal statute there on the right to acquire'

lease and hold real property without regard to race and color.

Wow we have a Federal statute which says specifically that the

courts may not enforce the custom of segregation.

JUSTICE BLACK: How would you define custom so as to

make it specific and definite, as a law has to be?

MRS. MOTLEY: Well, that which is generally pursued

in the community. Here we do not really have that problem because

the custom was identified in the South Carolina case and explic

itly recognized as the custom of the community.

JUSTICE BLACK: By what percentage of the community?

MRS. MOTLEY: Well, according to the record in this

case, it appeared thit this was universal during that period in

that particular city of Rock Hill but certainly it would have to

be a substantial majority of the community following a particular

custom of excluding Negroes, I would think, to say that we have

in this community a custom of discriminating against Negroes.

And certainly in every southern state where the state as a

matter of state policy, has had state laws requiring segregation

in various areas, all such states, I would say, have a custom

generally in the community of segregation flowing from that as

a matter of fact.

JUSTICE BLACK: In ocher words, state action would

be something less than law as you understand it, and it would

19

Shelley against Kraemer.

MRS. MOTLEY: Yes.

JUSTICE STEWART: Is there any indication in the legis

lative history of 201(d) that Congress intended to go beyond

existing case lav; in this matter of state discrimination, and

what was state discrimination? Specifically, that there was

any intention to import the supposed analogy of Shelley against

Kraemer in this connection?

MRS. MOTLEY: Vie 11, I have this quote from a

Committee or House Report here which says that state action may

under some circumstances be involved where the state lends its

aid to the enforcement of discriminatory practices carried on by

private persons. This is Shelley against Kraemer. The court

held that judicial enforcement of private restrictive covenants

constituted state action in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

So they specifically had Shelley in mind, as you see. The court

characterized the case as one in which the states had made

available to individuals desiring to oppose racial discrimination

the full coercive power of government. And then they cite Barrows,

and Bowman against Birmingham, which is a Fifth Circuit case,

and Lombard, which is a decision of this C ourt.

So chat it is clear that they had in mind our Shelley

argument in this situation.

JUSTICE STEWART: Really they reviewed this decision

in capsule form.

26

trespass.

MRS. MOTLEY: Yes.

JUSTICE HARLAN: That is the clear charge, right or

wrong.

MRS. MOTLEY: That is right.

JUSTICE HARLAN: And that is the charge that the

defendants knew was being preferred against them.

MRS. MOTLEY: That's right.

JUSTICE HARLAN: Is that equally true in the Lupper

case?

MRS. MOTLEY: Well, they were — I do not have a copy

of the warrant here. In the Lupper case — no, I do noc think

there is a copy of the warrant. There is a copy of the informa

tion, S. guess, on page 3 that I am looking at.

JUSTICE HARLAN: What does the information say?

MRS. MOTLEY: Well, there are two -- Act 14 — no,

there is not. That merely recites what took place in the

beginning here.

JUSTICE BRENNAN: Does this mean anything, Mrs.

Motley, on page 9, on a motion to quash — there is a recital

there — I guess this is defendant5s motion to quash. The

contention is that Act 226 and so forth, "under which these

defendants have been charged with creating a disturbance or

breach of the peace" and Act 14 under which these defendants

have been charged with failure to leave the business premises

27

of the store at the request of management.

MRS. MOTLEY: Yes, that v;as the defendants5 motion

to quash.

JUSTICE BRENNAN: Is that a recital of something?

MRS. MOTLEY: I am not certain that that is a recital

exactly what the information charged. I thought there was a

copy of the information at the beginning, but apparently not.

JUSTICE HARLAN: May I ask you one more question,

Senator.

Mr. Greenberg said that in the Hamm case, the vague

ness point which you are now addressing yourself to, was not

raised specifically, but he thought adequately, in terms of

the broader question that is involved in the Hamm, but not here,

as to the prosecutor's refusal to elect the statute under which

he was proceeding. Was the vagueness point raised in che Lupper

case below?

MRS. MOTLEY: Yes, sir, it was raised in the Supreme

Court of Arkansas and the Supreme Court of Arkansas passed on

it not precisely in these terms, but they said the statute

was clear, that what was required for conviction was a refusal

to leave the premises, and there was no ambiguity on the face

of the statute. But vagueness was definitely one of the issues

before the state court here.

JUSTICE ill RIAN: So they construed cheir statute as

meaning leaving the lunch counter as being included within the

29

the Attorney General, on his staff, and of course represent the

respondent in this action. I think it proper chat I mention

at the outset chat any lack of convincing quality in the brief

and my oral argument I hope is not based upon reasonable authority

thereof, but maybe my own ineptness and the feeling that every

young advocate may have at his baptism before this Court.

I think petitioners and cheir several eminent counsel

are to be congratulated on the magnificent job they have done,

both in preparing their brief and in this effective oral presenta

tion.

But I necessarily disagree with them.

I think it proper that certain aspects of the record

before this case be emphasised before I embark on the argument.

This case does involve a privately-owned — it is a

family-owned department score. It does have a mezzanine tea

room that does serve luncheons. And I certainly did not mis

lead — intend to mislead Mr. Justice Stewart in saying it

just served salads. They do have light luncheons in there.

But if you can imagine it just very briefly, this is the type

of place where during the serving hours a young lady comes out

and models sweaters and skirts and other female attire to their

customers chat are seated there. They are almost all women that

use this facility.

Now, these demonstrators, ̂ ame in. There were not

just five — there were five there perhaps when Mr. Holt came

45

THE CHIEF JUSTICE: That is all — that they had

colored boys up there. Now, what does that mean if it does

not mean that they were concerned about them because they were

colored?

MR. LESSENBERRY: Well, I can see this — that such

a record to this Court probably means that these people were

per se bad.

THE CHIEF JUSTICE: Because they were colored?

MR. LESSENBERRY: It is my impression — chat co me,

from Little Rock, and living in a community of different ethnic

groups, it means nothing else more than a description of who

was there. I just do not see that an officer or a store

manager saying "We have colored boys" means that is necessarily

bad. I do not think the store manager intended to give chat

implication.

THE CHIEF JUSTICE: Well, how about all your other-

restaur ants at that time? Did they or did they not cater to

white and colored?

MR. LESSENBERRY: There were some. There was a

restaurant at Ninth or Twelfth Street that was serving colored

and white when I was a child. People had been free to do what

they so desired. I see one of the petitioners, local counsel,

here, and that is the reason I looked back.

THE CHIEF JUSTICE: Suppose—

MR. LESSENBERRY: If I am misstating that—

49

I-iR. LESSEBBERRY: Yes, they were in position to

leave. I think they were in one of the corridors. One of them

stated he was looking at some shades.

The fact of the matter is, though, that upon the

request, upon two different requests, they said, "Well, what

for? Why? We are not going to leave." They wanted to argue

and did argue — and 1 suppose for a period of time. Ic did

not seem critical to the prosecutor below. And I honestly do

not think it i3 too critical here and now chat they stayed

there any time after these two lawful requests.

I want to skip a portion of my argument and move

over to the statement concerning the application of 203(c).

That is, as I read the notes of the brief of the petitioners,

they say that there is not retroactive application of the Civil

Rights Act. They admit that initially. But then they say that

203(c) prohibits punishment — shall prohibit punishment. They

would say at this time. In other words they would admit or say

to this Court "We agree that this was a criminal act, and chat

there was a valid prosecution, and that there is no retroaction

as far as the affirming state court conviction; but on the other

hand you cannot now convict them."

I think that—

JUSTICE STEWART: They make several alternative argu

ments. But as I understand it, you are certainly correct as to

one of their alternative arguments. It is not that you cannot

50

now convict them; it is chat you cannot now punish them.

MR. LESSBMBERRY: That is the point. In other words,

you would deprive from the entire legal process the thing to be

gained, punishment, from this. It makes legal procedure a

criminal procedure, a mockery and nothing more than a farce, to

my way of thinking, at least.

They say, and make a very emotional argument, that

if these punishments are to be permitted, that this would be

a last vestige of segregation — and after the national conscience

has said that these persons should not be convicted.

But if it please the Court, the national conscience

did not provide for retroaction. Congress could have done that.

They did not. The national conscience, in true terms, was

actually not in sympathy with these petitioners. If they were,

it would create a dual system of justice to my way of thinking,

simply for the benefit of these petitioners.

There have been a number of cases which dramatically

point this up.

This Court denied certiorari I think back in 1949

when the Federal statutes were changed from permitting imprison

ment for rape at either death or life imprisonment. After the

charge it went back for retrial, and they argued chat the jury

be instructed to provide for a lesser term of years — that the

jury be so instructed. The court refused to do so.

I think there is a significant difference in a man

51

being fined $500 and given 30 days, and not permitting a

jury to give him some term of years but serving life imprison

ment .

There are numerous analogies here — the violations

of the Emergency Price Control Act. I do not think there is

any question that this statute — we could twist it so it would

have Federal origin — itt would not have been abated under the

Federal savings statute.

I do not believe that the supremacy clause of the

United States Constitution has given such an interpretation

that we are going to treat states one way and Federal laws

another wav.

I want to say something about historical prejudices

in Arkansas and the South. I cannot help but feel some

personal animosity and disappointment in view of this argument.

I think that Arkansas — it is wrongful that Arkansas and the

community of Little Rock be condemned for some antiquated

statutes. I noticed one cited by the petitioners — it has

reference to separation of railways. If you look at chat

statute, it was enacted within three years of Plessey v.

Ferguson. It held what this Court held at that time. I think

a real fine analogy was Mr. GreenbergTs statement that he

did not believe that the provisions of the National Prohibition

Act have been repealed by our own Congress. Legislatures seem

to be too busy trying to take care of new business rather than

52

disponing of old business as it becomes ineffective.

There have been, as far as S know, even che Little

Rock school decision — there wasn't any Federal compulsion on

the Little Rock School Board. They implemented their own plan

of integration. It was only because of the disturbance there.

I invite the Court's attention to those cases, to see where

the community leaders, Chamber of Commerce, the police officers

all acted to enforce the law. And X think that they have.

I cannot believe that this Court will tell the

people of Arkansas that they will take judicial notice that

they, the people of Arkansas, are prejudiced. As Psalm 11 says,

it seems co me it is appropriate here — if our foundations shall

fall, what shall happen to the righteous. I think there are some

righteous people. I do not think it is proper -— if you can make

an argument of vagueness, if you can make an argument of vague

ness of the statute, you can certainly make an argument of

vagueness of this indictment that is brought against the

people of Arkansas because certainly there was no evidence

submitted below, there was no proof, there was some mere infer

ence in their motion for new trial that was not even argued.

If this had been a jury discrimination case, this Court would

hold, consistent with other holdings in hundreds of other cases,

that these matters have to be brought to the state court's

attention — Carter v. Texas. You cannot just file a motion,

and again prove and gain a reversal.

54

secured by this statute? Isn't that something unprecedented

in your state? Do you think any of the existing law in your

state covers that situation?

KIR. LESSENBERRY: I think the existing statute covers

it. But as far as I know, it has not been interpreted by a case.

But to borrow a phrase, if we go back to Sutherland on Statutory

Construction, and the purpose of a savings statute, in cases

in .Federal Courts — they ail adhere to that purpose. Because

immodestly enough if these demonstrators caused Congress co

enact a Civil Rights Act, still those people acted imprudently

when they went to a place and did not leave after they had been

advised to do so.

I want to talk very briefly now, if I may, in regard

to the case of Shelley v. Kraemer. 7. arn not absolutely satis

fied to simply distinguish Shelley v. Kraemer. i think Shelley

v. Kraemer is saying something more. X think it confirms the

fact that an individual has a right to discriminate if he so

desires.

X understand Shelley v. Kraemer co say two or three

different things. The first is that a state court cannot require

persons to discriminate if they do not wish to do so. Also,

Shelley v. Kraemer was determined in part at least on the feder

ally-given right of colored people to deal in property as white

men.

There is a phrase in Shelley v. Kraemer which is

55

significant to rue, and that is "Voluntary adherence co restric

tive covenants is not constitutional." Isnct that an individual

right, to discriminate, voluntary adherence? I believe that

it is.

t These cases are not like Marsh v. Alabama where a

decision can rest upon the right of religion, nor are they

as in Smith v. Airice, or Terry v. Adams, where under the

Thirteenth Amendment a person has a right. They are not cases

involving at this time, I hope, interstate commerce, where

we could invoke Boynton v. Virginia.

None of these cases, none of these principles say

that a person has a right to go to a particular restaurant,

a hot dog stand on the corner, or a mezzanine tea room and

demand service. Even petitioners in their brief describe it

as some sort of right. They do not define it for us,

And then in my closing moments, I want to—

JUSTICE BLACK: You do not deny that under the

Civil Rights Act they do have the right to go into such a

restaurant and ask for service?

DIR. LESSEMBERRY: Yes. I would presuppose and

concede that the Civil Rights Act, for the sake of this

argument, is constitutional in all respects.

JUSTICE BRENNAN: And would on the date this incident

happened have given them the right for service as demanded.

MR. LESSENBERRY: As a covered establishment. But