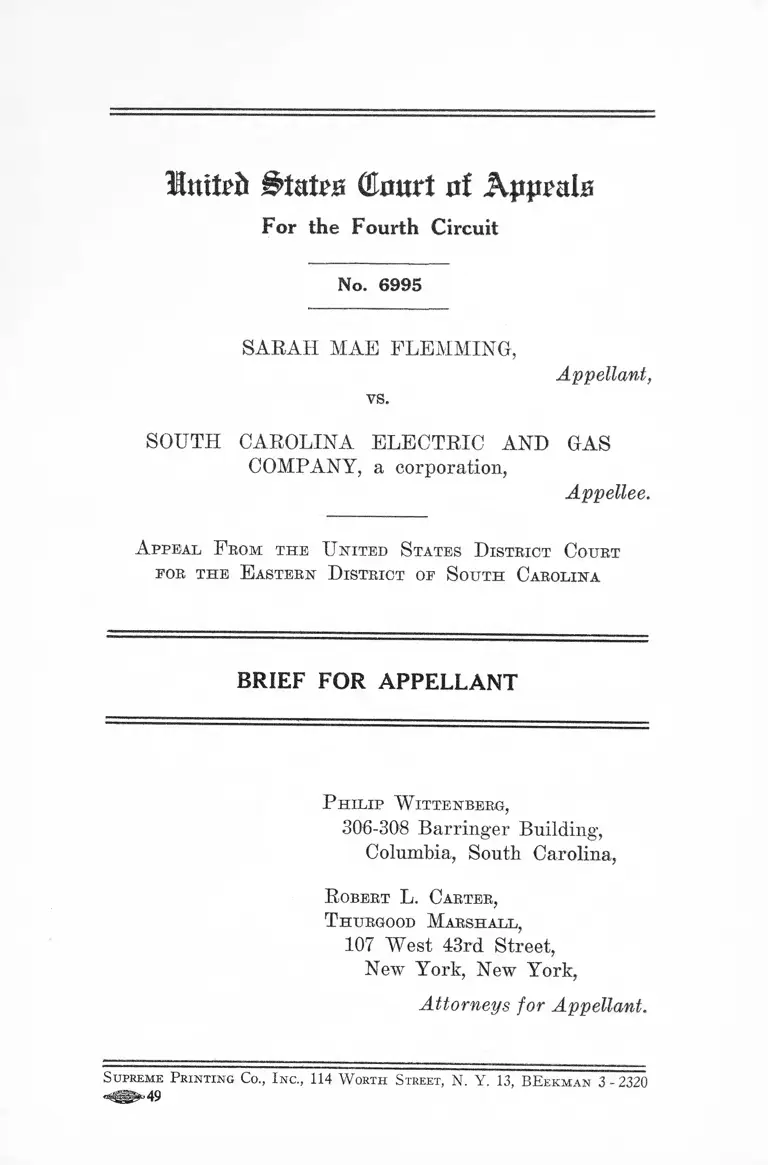

Flemming v. South Carolina Electric and Gas Company Brief for the Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1955

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Flemming v. South Carolina Electric and Gas Company Brief for the Appellant, 1955. 161f26f7-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/82b01060-04b7-4fa2-92cd-aa2f275c827a/flemming-v-south-carolina-electric-and-gas-company-brief-for-the-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

lUttfi'it Btntm ( ta r t nf Ajj^aln

For the Fourth Circuit

N o. 6 9 9 5

SARAH MAE FLEMMING,

vs.

Appellant,

SOUTH CAROLINA ELECTRIC AND GAS

COMPANY, a corporation,

Appellee.

A pp e a l F rom t h e U n it e d S tates D istr ic t C ourt

for t h e E a stern D istr ic t of S o u t h C arolina

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

P h il ip W itten b er g ,

306-308 Barringer Building,

Columbia, South Carolina,

R obert L. C arter,

T hurgood M a rshall ,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York,

Attorneys for Appellant.

Supreme Printing Co., I nc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, BEekman 3-2320

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Statement ....................... 2

Statutes Involved ........................................... 3

Questions Presented ................................................. 9

Argument :

I. Appellant’s complaint involves State action

within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amend

ment ................................................................. 10

II. The Statutes requiring enforcement of segre

gation by appellee are unconstitutional and

void and are not governed by the Plessy v.

Ferguson form ula........................................... 12

A. These Statutes Seek To Enforce Racial

Segregation Prohibited by the Fourteenth

Amendment under Present Interpretation

of the Scope and Reach of That Provision 13

B. The Ratio Decidendi of Plessy v. Fergu

son Has Been Repudiated and Only the

Bare Decision Remains............................. 14

1. The State Policy Here Involved Seeks

To Enforce Classifications and Distinc

tions Invalid under Both the Equal Pro

tection and Due Process Clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment ..................... 15

2. Established Custom, Usage and Tradi

tion Designed To Insure the Negro’s

Inferiority Cannot Be an Appropriate

Yardstick for Measuring State Action

Under the Fourteenth Amendment . . . . 17

3. The Police Power Argument Is Of No

A vail....................................... 18

PAGE

11

4. The Cases Upholding Segregation in

Public Education upon which the Plessy

Decision Rests Have Now Been Re

jected by the Supreme C ourt.............. 19

C. The Supreme Court’s Approach to the In

terstate Commerce Act Is a Clear Indi

cation that the State Policy Here Involved

Is Unconstitutional .................................. 21

D. This Court Is Not Bound to a Blind Adher

ence to Plessy v. Ferguson Merely Because

the Supreme Court Has Not Expressly

Rejected its Authority in Intrastate Com

PAGE

merce ......................................................... 26

Conclusion.................................................................. 28

Table of Cases

Barbier v. Connolly, 113 U. S. 2 7 ............................. 15

Barnette v. State Board, 47 F. Supp. 251 (1942),

aff’d, 319 U. S. 624 ............................................... 26

Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 28 . . . . 12

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 ....................12,13,15,18,

20, 25, 27, 28

Brown v. Baskin, 174 F. 2d 391 (CA 4th 1949) . . . . 12

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 . . . . 12,13,18,

20, 25, 27, 28

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 ................ 13,16,18,20

Chance v. Lambeth, 186 F. 2d 879 (CA 4th 1951),

cert, denied 341 U. S. 941...................................... 13

Chesapeake & 0. & S. R. R. Co. v. Wells, 85 Tenn.

613 (1887) ......................................................... 19

Chicago & N. W. R. R. Co. v. Williams, 55 111. 185

(1870) 19

I l l

Chiles, v. Chesapeake & Ohio Ry. Co., 218 U. S. 71 .. 13

Dawson v. Mayor, — F. 2d ----- , March 14, 1955

13,18, 21, 28

Day v. Owen, 5 Mich. 520 (1858) ........................... 19

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160 ................... 14

Enoch Pratt Free Public Library v. Kerr, 149 F. 2d

212 (CA 4th 1945), cert, denied 326 U. S. 721 . . . . 12

Hall v. DeOuir, 95 U. S. 485 .................................... . 13

Heard v. Georgia R. Co., ICC Rep. 428 (1888) . . . . 19

Heard v. Georgia R. Co., 3 ICC 111 (1889) ............. 19

Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816 13,17, 21, 22, 25

Houck v. So. Pacific R. Co., 38 Fed. R. 226 (C. C.

Texas 1888) ........................................................... 19

Hypes v. Southern R. Co., 82 S. C. 315, 64 S. E. 395

(1909) . . . , ............................................................. 12

Jones v. City of Opelika, 316 U. S. 584 .................... 27

King v. Illinois Central R. R. Co., 69 Miss. 245, 10

So. 42 (1891) ........................................................ 12

Logwood v. Memphis & C. R. R. Co., 23 Fed. 318

(C. C. Tenn. 1885) ................................................. 19

Marchant v. Pennsylvania R. Co., 153 U. S. 380 . . . . 15

Memphis & Charleston R. R. Co. v. Benson, 85 Tenn.

627 (1887) ............................................................... 19

Minnersville School District v. Gobitis, 310 U. S. 586 26

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80 .................... 22, 24

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 ........................... 12,18

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Ass ’n., 202 F. 2d

275 (CA 6th 1953), vacated and remanded 347

U. S. 971 ................................................................. 13

McCabe v. Atcheson, Topeka & Santa Fe Ry. Co., 235

U. S. 131................................................................. 22

McGuinn v. Forbes, 37 Fed. 639 (D. Md. 1889) . . . . 19

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637 13,18, 25

PAGE

IV

Nebbia v. New York, 291 U. S. 502 ........................... 16

New Jersey Steam-Boat v. Brockett, 121 U. S. 637 .. 13

People v. Gallagher, 93 N. Y. 438 ........................... 20

People v. King, 110 N. Y. 418 (1888) ....................... 19

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 567 ...........1,10,14,15,17,18

19, 20, 21, 28

Railroad Co. v. Brown, 17 Wall. 445 ................ . 17

Rice v. Elmore, 165 F. 2d 387 (CA 4th 1947), cert.

denied 333 U. S. 875 ............................................. 12

Roberts v. Boston, 5 Cush. 198 (1849) .................... 20

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 IT. S. 1..........................2,13,17, 22

Silver v. Silver, 280 U. S. 117 .................................. 16

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 ........................... 17

South Florida R. Co. v. Rhoads, 25 Fla. 40, 5 So.

623 (1889) ............................................................... 10

St. Louis & M. & S. Ry. Co. v. Waters, 105 Ark. 619,

152 S. W. 619 (1912) ........................................ 12

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 ................ 17

Sweat! v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ....................... . 18, 25

Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461.................................. 12

The Sue, 22 Fed. 843 (C. C. Tenn. 1885) ................ 19

Westchester & P. R. Co. v. Miles, 55 Pa. 209 (1867) 19

Whiteside v. Southern Bus Lines, 177 F. 2d 949 (CA

6th 1949) .................................................. 13

Williams v. Carolina Coach Co., I l l F. Supp. 329

(E. D. Va. 1952), aff’d 207 F. 2d 408 (CA 4th 1953) 13

Statutes

S. C. Code, § 58-1401 (1952) .................................... 3,11

S. C. Code, §58-1402 (1952) .................................. 4,11

S. C. Code, §58-1403 (1952) ...................................... 4,11

S. C. Code, §58-1406 (1952) ............................. 5,11

PAGE

PAGE

C. S. Code, § 58-1422 (1952) ..................... .............. 5,11

S. C. Code, §58-1451 (1952) ..................... .............. 5,11

S. C. Code, §58-1452 (1952) . .................... .............. 6,11

S. C. Code, § 58-1453 (1952) .................. . . . . . . . . . 6,11

S. C. Code, §58-1461 (1952) ...................... ............ 6,11

S. C. Code, §58-1491 (1952) .................. .............. 2,7,10

S. C. Code, § 58-1492 (1952) ....... ......... .............. 2,7,10

S. C. Code, § 58-1493 (1952) ...................... .............. 2,7,10

S. C. Code, §58-1494 (1952) ...................... .............. 8,10

S. C. Code, §58-1495 (1952) ..................... .............. 8,10

S. C. Code, § 58-1496 (1952) ...................... .............. 9,10

Interstate Commerce Act, 49 USCA §3(1). .21, 22, 23, 24, 25

Other Authorities

35 Am. Jur., 983 , ...................................................... 12

Dollard, Caste and Class in A Southern Town 350

(1932) .................................................................... 17

Johnson, Patterns of Negro Segregation, 270 (1943) 17

Myrdal, 1 American Dilemma, 635 (1944) ............ 17

Waite, The Negro in the Supreme Court, 30 Minn.

L. R. 219 (1946) 19

litttteii #tat££ CEnurt nf Appals

For the Fourth Circuit

No. 69 9 5

--------------o—------------

S arah M ae F l e m m in g ,

vs.

Appellant,

South Carolina E lectric and Gas C o m pa n y , a corporation,

Appellee.

A ppe a l from t h e U n ited S tates D istr ic t C ourt for t h e

E astern D istrict of S o u t h Carolina

'■— ----------------------------------------------- o ------------------------------------------------------------

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Statement

Appellant, a Negro woman, brought this action in the

court below to recover damages resulting from appellee’s

enforcement of unconstitutional and discriminatory laws

requiring the enforcement of racial segregation in intra

state carriers operating within the State of South Carolina

(la). Appellee filed a motion to dismiss (5a) and an answer

(6a). The trial court found the state policy requiring racial

segregation consistent with the Fourteenth Amendment on

the theory that the “ separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy

v. Ferguson governed disposition of this case. Based upon

this conclusion, the court granted appellee’s motion to dis

miss on the ground that the complaint failed to state a

claim upon which relief could be granted (7a). The court ’s

opinion is reported at 128 F. Supp. 469. This appeal fol

lowed.

2

The facts are briefly these (see appellant’s complaint at

la) : On June 22, 1954, appellant boarded a bus owned by

appellee, a carrier engaged in the business of transporting

the public via bus in Columbia, South Carolina. The par

ticular bus on which appellant rode was typical of those in

appellee’s fleet. It had a front and a rear exit; a long ver

tical seat on either side at the front and directly behind the

driver; behind this, horizontal seats on each side of the aisle,

extending to the rear, with a long back rear seat extending

across the entire width of the bus. Under South Carolina

law, Sections 58-1491-1493, Code of Laws of South Caro

lina, 1952, segregation of the races on motor vehicle car

riers is required and violations are subject to fine. Section

58-1493 empowers the bus driver to change the designation

of space ‘ ‘ so as to increase or decrease the amount of space

or seats set apart for either race * * * But no contiguous

seats on the same bench shall be occupied by white and col

ored persons at the same time. ’ ’ To comply with these pro

visions, appellee lias adopted and enforces a policy of seat

ing white persons from the front to rear and Negro passen

gers from rear to front. Pursuant to these rules or practices,

no Negro may occupy a seat in front of space in which white

persons are sitting; and no Negro can sit beside a white

person.1

When appellant got on the bus, it was extremely crowded,

and many Negroes were standing up front where wThite

people were seated. Since no Negro could sit in front of or

beside a white person, the seats at the front of the bus were

exclusively reserved for white passengers at that time.

While appellant was standing in this section of the bus, a

white passenger, who was occupying the first or second hori

zontal seat on the right-hand side of the bus, got up to leave.

1 Of course the converse is true. No white person is supposed to

sit behind or beside a Negro. But these indiscriminate discrimina

tions, see Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, are of no aid in a deter

mination of the constitutionality of the state’s policy.

3

•Appellant took the .seat vacated, which resulted in her sit

ting in front of one or two white passengers. As soon as

. she sat down, the bus driver ordered appellant to move to

the rear in a loud and threatening tone of voice. When he

repeated this order a second time, fearing further humilia

tion and possible bodily harm, appellant left the disputed

seat and prepared to leave the bus although as yet some dis

tance from her desired destination. When the bus stopped

to permit passengers to get off, appellant attempted to fol

low a white passenger out the front door. The aisle was

extremely crowded to the rear. The driver permitted the

white passenger to exit from said front door but refused

to allow the appellant to do so. He ordered her to leave

by the rear door and struck her to enforce his command—

all this solely because of appellant’s race and color.

As aforesaid, the trial court dismissed for failure to

state a claim upon which relief could be granted. We

brought the cause here convinced that this was error.

Statutes Involved

PUBLIC SERVICE COMPANIES

ARTICLE 1.

G en era l P rovisions

§ 58-1401. Definitions.

As used in articles 1 to 6 of this chapter:

(1) The term “ corporation” means a corporation, com

pany, association or joint stock association;

(2) The term “ person” means an individual, a firm or

a copartnership;

(3) The term “Commission” means the Public Service

Commission;

4

(4) The term “ motor vehicle carrier ” means every cor

poration or person, their lessees, trustees or receivers, own

ing, controlling, operating or managing any motor propelled

vehicle, not usually operated on or over rails, used in the

business of transporting persons or property for compen

sation over any improved public highway in this State;

(5) The term “ trailer” means a vehicle equipped to

carry a load and which is attached to and drawn by a motor

vehicle and trailers shall be classed as motor vehicles and.

subject to the provisions of articles 1 to 6 of this chapter;

and

(6) The term “improved public highway” means every

improved public highway in this State which is or may here

after be declared to be a part of the State Highway System

or any county highway system or a street of any city or

town.

§ 58-1402. Transportation by motor vehicle for compensa

tion regulated.

No corporation or person, their lessees, trustees or

receivers, shall operate any motor vehicle for the transpor

tation of persons or property for compensation on any im

proved public highway in this State except in accordance

with the provisions of this chapter and any such operation

shall be subject to control, supervision and regulation by

the Commission in the manner provided by this chapter.

§ 58-1403. Certificate and payment of fee required.

No motor vehicle carrier shall hereafter operate for the

transportation of persons or property for compensation on

any improved public highway in this State without first

having obtained from the Commission, under the provisions

of article 2 of this chapter, a certificate and paid the license

fee required by article 3.

5

§ 58-1406. Penalties.

Every officer, agent or employee of any corporation and

every other person who wilfully violates or fails to comply

with, or who procures, aids or abets in the violation of, any

provision of articles 1 to 6 of this chapter or who fails to

obey, observe or comply with any lawful order, decision,

rule, regulation, direction, demand or requirement of the

Commission or any part or provision thereof shall be guilty

of a misdemeanor and punishable by a fine of not less than

twenty-five dollars nor more than one hundred dollars or

imprisonment for not less than ten days nor more than

thirty days.

§ 58-1422. Revocation, etc., of certificates; appeal.

The Commission may, at any time, by its order, duly en

tered, after a hearing had upon notice to the holder of any

certificate hereunder at which such holder shall have had

an opportunity to be heard and at which time it shall be

proved that such holder has wilfully made any misrepre

sentation of a material fact in obtaining his certificate or

wilfully violated or refused to observe the laws of this State

touching motor vehicle carriers or any of the terms of his

certificate or of the Commission’s proper orders, rules or

regulations, suspend, revoke, alter or amend any certificate

issued under the provisions of articles 1 to 6 of this chapter.

But the holder of such certificate shall have the right of

appeal to any court of competent jurisdiction.

ARTICLE 4.

D rivers ’ P e r m it s .

§ 58-1451. Drivers’ permits required of operators.

No certificate holder under article 2 of this chapter, shall

operate or permit any person to operate a motor vehicle

for the transportation of persons or property for compen

6

sation in this State unless and until the operator thereof• .

shall have obtained from the Public Service Commission a

driver’s permit, which may be revoked for cause by the

Commission. No such permit shall be issued to any person ,

under eighteen years of age. Such permit shall always lie

carried by the person to whom it is issued , and .shall be

shown to any official or citizen upon request.

§ 58-1452. Examination and qualifications required for

drivers’ permits.

Each applicant for a driver’s permit under the provi

sions of this article shall be examined by a person desig

nated by the Commission as to his knowledge of the traffic

laws of this State and as to his experience as a, driver and

such applicant may be required to demonstrate his skill and

ability to handle safely his vehicle. He shall be of good

moral character and he shall furnish such information con

cerning himself as required, upon forms provided for such ,

purpose. The Commission shall provide for such examina

tions and issue such permits as such examinations may

justify. If the result of any such examination be unsatis

factory, the permit shall be refused.

§ 58-1453. Fee for drivers’ permits.

The Commission shall collect an annual fee of two. dol

lars for each driver’s permit issued hereunder and: all! funds n :

so collected shall be paid into the State Treasury monthly,: ,

to the credit of the State Highway Fund.

ARTICLE 5.

R ig h t s and D u t ie s G en er a lly .

§58-1461. Commission to supervise carriers; rates.

The Commission shall supervise and regulate every

motor carrier in this State and fix or approve the rates,

fares, charges, classification and rules and regulations per-

7

taming thereto of each such motor carrier. The rates now

obtaining, for the respective motor carriers shall remain in

effect until such time when, pursuant to complaint and

proper hearing, the Commission shall have determined that

such rates are unreasonable.

MOTOR VEHICLE CARRIERS

ARTICLE 7

S egregation o r R aces

§ 59-1491. Segregation required.

All passenger motor vehicle carriers operating in this

State shall separate the white and colored passengers in

their motor buses and set apart and designate in each bus

or other vehicle a portion thereof, or certain seats therein,

to be occupied by white passengers and a portion thereof,

or certain seats therein, to be occupied by colored passen

gers, any such carrier that shall fail, refuse, or neglect to

comply with the provisions of this section shall be guilty

of a misdemeanor and, upon indictment and conviction,

shall be fined not less than fifty dollars nor more than two

hundred and fifty dollars for each offense.

§ 58-1492. Discrimination in accommodations prohibited.

- Such carriers shall make no difference or discrimina

tion in the quality or convenience of the accommodations

provided for the two races under the provisions of § 58-1491.

§58-1493. Changing space assigned or requiring change

of seats.

The driver, operator, or other person in charge of any

such motor vehicle shall at any time when it may be neces

sary or proper for the comfort and convenience of passen

gers so to do, change the designation so as to increase or

8

decrease the amount of space or seats set apart for either

race and may require any passenger to change his seat as

it may be necessary or proper. But no contiguous seats on

the same bench shall be occupied by white and colored per

sons at the same time. Any driver, operator or other per

son in charge of any such vehicle who shall fail or refuse

to carry out the provisions of this section shall be guilty

of a misdemeanor and upon conviction thereof shall be fined

not less than five dollars nor more than twenty-five dollars

for each offense.

§ 58-1494. Driver a special policeman.

Each driver, operator or person in charge of any such

vehicle, in the employment of any company operating it,

while actively engaged in the operation of such vehicle,

shall be a special policeman and have all the powers of a

conservator of the peace in the enforcement of the provi

sions of this article and in the discharge of his duty as such

special policeman in the enforcement of order upon such

vehicle. Such driver, operator or person in charge of such

vehicle shall likewise have the powers of a conservator of

the peace and of a special policeman while in pursuit of

persons for disorder upon such vehicles or for violating the

provisions of this article and until such persons as may

be arrested by him shall have been placed in confinement

or delivered over to the custody of some other conservator

of the peace or police officer. Acting in good faith, he shall

be for the purposes of this article the judge of the race

of each passenger whenever such passenger has failed to

disclose his race.

§ 58-1495. Violations of article by passengers.

All persons who fail while on any motor vehicle car

rier to take and occupy the seat or seats or other space

assigned to them by the driver, operator or other person

in charge of such vehicle or by the person whose duty it is

9

to take up tickets or collect fares from passengers therein

or who fail to obey the directions of any such driver, oper

ator or other person in charge as aforesaid to change their

seats from time to time as occasions may require, pursu

ant to any lawful rule, regulation or custom in force by

such lines as to assigning separate seats or other space to

white and colored persons, respectively, having been first

advised of the fact of such regulation and requested to

conform thereto, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and

upon conviction thereof shall be fined not less than five

dollars nor more than twenty-five dollars for each offense,

§ 58-1496. Ejection of such passengers.

Any person who shall violate any of the provisions of

§ 58-1495 may be ejected from any such vehicle by any

driver, operator or person in charge of such vehicle or by

any police officer or other conservator of the peace and,

if any such person ejected shall have paid his fare upon

such vehicle, he shall not be entitled to the return of any

part of it. For the refusal of any such passenger to abide

by the request of the person in charge of the vehicle, as

aforesaid, and his consequent ejection from the vehicle,

neither the driver, operator, person in charge, owner, man

ager, or bus company operating the vehicle shall be liable

for damages in any court.

Questions Presented

1. Whether appellant’s challenge to the enforcement of

a state policy, requiring the segregation of Negro and white

passengers on intrastate carriers operating in the State of

South Carolina as violative of her rights under the Four

teenth Amendment and claim for damages for injuries

resulting therefrom, constitute a valid cause of action cog

nizable in the federal courts?

10

2. Whether in light of the present status of the law-

in respect to the scope and reach of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, a federal court should apply prevailing constitu

tional yardsticks in this case and hold the state policy here

in question unconstitutional, even though the Supreme

Court has not. yet specifically overruled Plessy v. Ferguson

in the field of intrastate commerce!

ARGUMENT

I

Appellant’s complaint involves State action within

the meaning of the Fourteenth Am endm ent.

Appellee is engaged in the business of a motor vehicle

carrier, transporting passengers for hire over the streets

of Columbia, South Carolina. Appellee operates under

franchise and as such enjoys monopolistic privileges. As

has been aptly stated by one court, the rules and regula

tions of a common carrier insofar as they affect the travel

ling public are minor laws. South Florida B. Co. v. Rhoads,

25 Fla. 40, 5 So. 623 (1889).

Sections 58-1491, 1492, 1493, 1494, 1495 and 1496 (set

out ante) provide for the segregation of the races on motor

vehicle intrastate carriers operating within the State of

South Carolina; require that equality be provided in respect

to appointments and conveniences; make violations by car

rier, driver or passenger a misdemeanor subject to fine;

make each operator in charge of the bus a special police

man with authority to preserve the peace and enforce the

state laws with respect to segregation, with power to con

fine and arrest for violations thereof; and hold the carrier

and bus operator free from damages resulting from the

ejection of any person who refuses to obey the bus driver

in connection with these provisions. Pursuant to these

11

provisions, appellee is required to enforce racial segrega

tion in the seating of Negro and white passengers on its

buses. Appellee is also authorized to enforce the state

policy in this respect, and its drivers are made special

police officers for this purpose. Appellee has adopted the

state’s policy as its own. It enforces a policy or practice

with respect to the loading and seating of Negro and white

passengers which fully incorporates the state regulations

and is a de facto and de jure state agency for enforcement

and maintenance of racial segregation on its vehicles.

In addition, the state controls and regulates appellee’s

operation through a Public Service Commission. See par

ticularly Sections 58-1401 to 58-1403, Section 58-1406, Sec

tion 58-1422, Sections 58-1451 to 58-1453 and Section 58-1461

of the Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1952 set out ante.

Under these provisions the Public Service Commission is

given authority to supervise and regulate carriers operat

ing intrastate, approve rates (58-1461); license drivers

(58-1451); grant and revoke certificates of public conve

nience (58-1403 and 1422). The carrier, its officers,

agents or employees and “ every other person who * * *

fails to obey, observe or comply with any lawful order,

decision, rule, regulation, direction, demand or require

ment of the Commission * * *” are subject to criminal pen

alties (58-1406). Thus, appellee is required to act for the

state in the enforcement of racial segregation on its buses,

and is subject not only to fine and conviction for failure to

comply with state policy, but also to the complete destruc

tion of its business by revocation of its certificate of public

convenience.

There can be no question but that in the course of the

altercation here that the bus driver, Warren Christmus,

was acting within the scope of his employment. He was

seeking to enforce the state segregation laws as required

both by statute and by his duty as an employee and to pro

tect his employer from penalties resulting from violation

12

of state law. That his acts in this regard are the acts of

appellee, and that appellee is thus responsible is clear

beyond question. See Hypes v. Southern 11. Co., 82 S. C.

315, 64 S. E. 395 (1909), and cases cited in 35 Am. Jur. 983-

984. The statutes which make the bus driver a conservator

of the peace in no way destroys the master-servant rela

tionship, nor relieves the carrier of its responsibility here

to appellant. See King v. Illinois Central R. R. Co., 69

Miss. 245, 10 So. 42 (1891); St, Louis dc M & S. Ry. Co. v.

Waters, 105 Ark. 619, 152 S. W. 619 (1912). Further, it

is clear that the carrier in regard to the enforcement of

the state policy requiring segregation was a state instru

mentality at least for this limited purpose, and thus the

action here complained of constitutes state action within

the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment. See Enoch

Pratt Free Public Library v. Kerr, 149 F. 2d 212 (CA 4th

1945), cert, denied, 326 U. S. 721; Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S.

461; Rice v. Elmore, 165 F. 2d 387 (CA 4th 1947), cert,

denied, 333 U. S. 875; Brown v. Bas.hin, 1?4 F. 2d 391 (CA

4th 1949). Appellee was enforcing the state policy both

for itself and for the state, and appellant was entitled to

invoke the protection of the Fourteenth Amendment,

I I

The statutes requiring enforcem ent of segregation

by appellee are unconstitutional and void and are not

governed by the Plessy v. Ferguson formula.

Whatever the status of the “ separate but equal” doc

trine today, the trend of decisions culminating in Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, and Bolling v. Sharpe,

347 U. S. 497 (the School Segregation Cases) has been to

give greater sweep and scope to the Fourteenth Amend

ment’s interdiction against state enforced racial or color

distinction. Morgan v. Virginia, 328 IT, S. 373, and Bob-Lo

Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 28, have weakened the

13

doctrine’s effectiveness in intrastate commerce. The School

Segregation Cases, supra; McLaurin v. Oklahoma State

Regents, 339 U. S. 6 3 7 Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1;

Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816; Buchanan v.

Warle-y, 245 U. S. 60; Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical

Assn., 202 F. 2d 275 (CA 6th 1953), vacated and remanded,

347 U. S. 971; and this Court’s decision in Dawson v. Mayor,

----- F. 2 d ----- , decided March 14, 1955, have abandoned

the “ separate but equal” doctrine in public education, hous

ing, interstate commerce and public recreation. True, these

decisions do not apply in terms to intrastate commerce. We

think, however, that, these more recent developments in the

law warrant the conviction that the kind of state policy

here involved also falls within the Fourteenth Amend

ment’s proscription against state enforced racial distinc

tions.

A . T h e se S ta tu te s S eek to E n fo rc e R a c ia l S e g re

g a tio n P ro h ib ite d b y th e F o u r te e n th A m e n d

m e n t u n d e r P re s e n t I n te r p r e ta t io n o f th e

S co p e and R e a c h o f T h a t P ro v is io n .

A common carrier is required to protect its passengers

against assault or interference with the peaceful comple

tion of their journey, New Jersey Steam-Boat Co. v. Brock-

ett, 121 U. S. 637; and to be ready and willing to serve on an

equal basis all passengers who might apply without dis

tinction or discrimination.2

2 It is true that Chiles v. Chesapeake & Ohio Ry. Co., 218 U. S.

71, holds that carriers may regulate the seating of Negro and white

passengers in interstate commerce in the absence of national regula

tion. But this theory grew out of the vacuum left by the decision in

Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485, that such regulation was outside the

province of the states. In the absence of federal regulation, it was

felt, therefore, that incorporation of the “separate but equal” doctrine

into the carrier regulations was permissible. Contra: Whiteside v.

Southern Bus Lines, 177 F. 2d 949 (CA 6th 1949) ; Chance v. Lam

beth, 186 F. 2d 879 (CA 4th 1951), cert, denied, 341 U. S. 941;

Williams v. Carolina Coach Co., I l l F. Supp. 329 (E. I). Va. 1952),

aff’d, 207 F. 2d 408 (CA 4th 1953).

14

Appellant is here asserting a right considered sacred in

a democracy—the right to freedom of locomotion. But for

the state policy here being questioned, there could be little

doubt that appellee violated its contractual obligation to

appellant under the circumstances of this case.

It could not be seriously contended that any state by

legislation or common carrier by regulation could deny to

any group of its citizens the right of access to the services

of common carriers solely on the basis of race or color.

Indeed, freedom of locomotion cannot be hampered by state

legislation even though for the laudable purpose of pro

tecting the property of persons already resident within a

particular state. Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160.

The question raised here is whether a state policy which

restricts appellant’s liberty to use common carrier facili

ties on the grounds of race is offensive to the Fourteenth

Amendment, We contend that it is, despite the fact that

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 567, has specifically applied

the 1 ‘ separate but equal ’ ’ doctrine in the field of intrastate

commerce.

B. T h e R a tio D e c id e n d i o f P le s sy v. F e rg u so n H a s

B een R e p u d ia te d a n d O n ly th e B a re D ec ision

R em a in s .

The rationale relied upon for the adoption of the “ sepa

rate but equal” doctrine in Plessy v. Ferguson was based

upon three fundamental premises: (1 ) that, classifications

and distinctions based upon race were not violative of the

constitution as long as equal facilities were provided the

Negro group; (2) that laws based upon established social

usage, custom, and tradition were not unreasonable; and

(3) that since the statute in question was designed to pre

serve the public peace, state power exerted to achieve this

end could not have been prohibited by the Fourteenth

Amendment. Moreover, the Court in the Plessy ease relied

15

all but exclusively on state and lower federal court deci

sions upholding segregation in public schools to support

these premises, upon which it grounded its conclusion

that the Louisiana statute was constitutional.

Now segregation has been expressly declared unconsti

tutional in the field of public education, and the present

approach of the Supreme Court to the Fourteenth Amend

ment is at war with the rationale of the Plessy case. Thus,

all that remains is the Plessy decision itself with its ra

tionale repudiated and the precedents on which it relied

for support discarded—now at best, a sport in the law.

1. T h e S tate P olicy H ebe I nvolved S e e k s to

E nforce Cla ssifica tio n s and D ist in c t io n s

I nvalid I I ndeb B o th t h e E qual P rotection

and D u e P rocess C lauses of t h e F o u r t e e n t h

A m e n d m e n t .

It has long been held that the Fourteenth Amendment

prohibited all unreasonable classifications and distinctions

even though non-racial in character. See Barbier v. Con

nolly, 113 U. S. 27; MarcJiant v. Pennsylvania 11. Co., 153

IT. S. 380, 390. In Plessy this yardstick was not applied

and segregation was upheld. Thus, the conventional test

applicable to state classifications and distinctions in general

were never applied to governmental action requiring the

segregation of Negroes. “ Separate but equal” was sub

stituted instead.

There can no longer be doubt, however, as a result of

Bolling v. Sharpe, supra, that racial differentiations en

forced pursuant to state law are now subject at least to

the same test applicable to legislative classifications and

distinctions non-racial in character. There the Court said:

Classifications based solely upon race must be

scrutinized with particular care, since they are con

trary to our traditions and hence constitutionally

16

suspect. As long ago as 1896, this Court declared

the principle ‘that the Constitution of the United

States, in its present form, forbids, so far as civil

and political rights are concerned, discrimination by

the General Government, or by the States, against

any citizen because of his race.’ And in Buchanan

v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, the Court held that a stat

ute which limited the right of a property owner to

convey his property to a person of another race

was, as an unreasonable discrimination, a denial of

due process of law.

Although the Court has not assumed to define

‘liberty’ with any great precision, that term is not

confined to mere freedom from bodily restraint.

Liberty under law extends to the full range of con

duct which the individual is free to pursue, and it

cannot be restricted except for a proper govern

mental objective.. Segregation in public education

is not reasonably related to any proper governmen

tal objective, and thus it imposes on Negro children

of the District of Columbia a burden that consti

tutes an arbitrary deprivation of their liberty in

violation of the Due Process Clause.

The real aim of the statutes now before this Court is

to perpetuate the myth of an inferior Negro and a superior

white caste. Measured against due process, this state policy

must fall because it seeks to deprive Negroes of liberty in

order to maintain and perpetuate a color caste in South

Carolina. Measured against equal protection, the policy

is bad because the color classification here enforced is not

based upon any real difference pertinent to a valid legis

lative objective.8 As such, these distinctions cannot stand,

since they are arbitrary and unreasonable. 3

3 Compare Nebbia v. New York, 291 U. S. 502 (due process),

with Silver v. Silver, 280 U. S. 117 (equal protection) in respect to

the similarity in the test of reasonableness under either clause.

17

2. E sta blish ed C ustom , U sage and T radition

D esigned to I n su r e t h e N egro ’s I n fer io r ity

C an n o t be an A ppro pria te Y ardstick for

M ea su rin g S tate A ctio n U nder t h e F our

t e e n t h A m e n d m e n t .

In Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court found the

Louisiana statute which required racial segregation in

intrastate carriers reasonable because the state, policy

accorded with the established social usage, custom and

tradition. But the primary intendment of the Thirteenth,

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments was to revolution

ize the legal relationship between Negro and white per

sons and place the Negro on a plane of complete equality

with the white man. Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S.

303. And see Railroad Co. v. Brown, 17 Wall 445. There

can be little doubt at this late date that racial segregation

stems from a belief in the Negro’s inferiority and is

designed to perpetuate the myth of white supremacy. As

such, segregation on buses and street cars is bitterly

resented by Negroes as a badge of inferiority. See Myrdal,

1 American Dilemma 635 (1944); Johnson, Patterns of

Negro Segregation 270 (1943); Dollard, Caste and Class

in A Southern Town 350 (1937). Unquestionably, this was

the kind of established social usage, custom and tradition

that the Fourteenth Amendment intended to eradicate from

the American scene.

In the cases involving the rights of Negroes under the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, our courts have

consistently refused to regard custom and usage, however

widespread, as determinative of reasonableness. This was

true in Smith v. Allivright, 321 U. S. 649, of a deeply en

trenched custom and usage of excluding Negroes from vot

ing in the primaries. It was true in Shelley v. Kraemer,

supra, of a long-standing custom of excluding Negroes

from the use and ownership of real property on the basis

of race. In Henderson v. United States, supra, a discrimi

18

natory practice of many years was held to violate the

Interstate Commerce Act, In the Swecitt v. Painter, 339

U. S. 629; McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, supra; and

the School Segregation Cases, supra, the Court broke with

a long-standing and deeply rooted tradition of enforced seg

regation in public education. In each instance the custom

and usage had persisted for generations, and this was cited

as grounds for its sanction. But to give sanction to custom

and usage aimed at perpetrating racial inferiority, which

the Fourteenth Amendment was specifically designed to

correct, is to countenance defeat and frustration of the

Amendment’s purpose. For this reason the Plessy argu

ment falls under its own weight.

3. T h e P olice P ow er A r g u m e n t is oe no A vail .

The Plessy reasoning that racial segregation is neces

sary to preserve the public peace, and should, there

fore, be upheld, is no longer persuasive. For if the

state does not have the power asserted, its exertion is

no less unconstitutional if exercised to preserve the peace

than if exercised to perform some other governmental

function. See Buchanan v. War ley, supra; and Mor

gan v. Virginia, supra. And this Court’s statement

in Dawson v. Mayor, — F. 2d —, March 14, 1955, has

definite pertinence here: “ It is now obvious, however,

that segregation cannot be justified as a means to preserve

the public peace, merely because the tangible facilities

furnished to one race are equal to those furnished the

other. . . .”

Police power, therefore, can no longer support an

exertion of state authority otherwise in conflict with con

stitutional rights.

19

4. T h e C ases U ph o l d in g S egregation in P ublic ■_

E ducation U po n W h ic h t h e P lessy D ecisio n

B ests H ave N ow B e e n B e je c t e d by t h e ;

S u pr e m e C o urt .

The Court in Plessy rested its decision almost exclu

sively on state and lower federal court cases upholding

segregation in the public schools.4

Throughout its opinion, the Court in Plessy cited school

cases as the sole authority for the major points of its deci

sion. Bor example, at page 544, the Court said that laws “ re-

quiring their [white and Negro] separation in places

where they are liable to be brought into contact do not neces

sarily imply the inferiority of either race to the other, and

4 The court cites only one group of non-school cases as direct

authority for its; decision. This is a string of state and lower federal

Court decisions cited by the Court at p. 548 as holding that stat

utes requiring segregation on public conveyances are constitutional.

It appears, however, that not one of these cases actually stands for

this proposition. See Waite, The Negro in the Supreme Court, 30

Minn. L. R. 219, 248-251 (1946). At least two of the cases were

decided either before passage or ratification of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. West Chester & P. R. Co. v. Miles, 55 Pa. 209 (1867)-; Day

v. Owen, 5 Mich. 520 (1858). Several of the cases did not concern

any governmental enactment or action at all. The Sue, 22 Fed. 843

(C. C. Tenn. 1885 ) ; McGuinn v. Forbes, 37 Fed. 639 (D. Md.

1889:) ; Chicago & N. W. R. R. Co. v. Williams, 55 111. 185 (1870).

One case upheld a criminal indictment of a proprietor of an amuse--

ment park for refusing to admit Negroes against an attack that the

New York statute authorizing the indictment was unconstitutional.

People v. King, 110 N. Y. 418 (1888). And none of the other

cases dealt with the constitutionality of governmental enactments or

action requiring or permitting the segregation of persons because of

race. Chesapeake, O. & S. R. R. Co. v. Wells, 85 Tenn. 613 (1887) ;■

Memphis & Charleston R. R. Co. v. Benson, 85 Tenn. 627 (1887) ;

Houck v. So. Pacific R. Co., 38 Fed. R. 226 (C. C. Texas 1888) ;

Logwood v. Memphis & C. R. R. Co., 23 Fed. 318 (C. C. Tenn.

1885) ; Heard v. Georgia R. Co., 1 ICC Rep. 428 (1888) ; Heard v.

Georgia R. Co., 3 ICC Rep. I l l (1889).

2 0

have been generally, if not universally, recognized as within

the competency of the state legislatures in the exercise of

their police power. The most common instance of this is con

nected with the establishment of separate schools . . .”

(emphasis added). The Court then proceeded to quote

extensively from Robert v. Boston, 5 Cush. 198 (1849), a

Massachusetts decision, which held school segregation valid

and cited several other state and federal school cases to

the same effect at 545.

Later, the Court, after conceding at 550 that “ every

exercise of the police power must be reasonable and extend

only to such laws as are enacted in good faith for the pro

motion of the public good and not for the annoyances or

oppression of a particular class,” stated at 550-551 that

“ [g]auged by this standard, we cannot say that a law which

authorizes or even requires the separation of the two races

in public conveyances is unreasonable or more obnoxious

to the 14th Amendment than the acts of Congress requiring

separate schools for colored children in the District of

Columbia, the constitutionality of which does not seem to

have been questioned, or the acts of state legislatures.”

Finally, for its argument that the harmony of the races

cannot be promoted by laws which conflict with the general

sentiment of the community, the Court again cites as sole

authority a school case, People v. Gallagher, 93 N. Y. 438,

448.

But the School Segregation Cases have now made it clear

that the states and the federal government are prohibited

from enforcing racial segregation in public education. Thus,

the main body of legal precedent upon which the Plessy case

relies can no longer be considered authority to support such

a decision today.

Moreover, it is unlikely and unthinkable that state im

posed racial segregation would be considered arbitrary

and unreasonable in the field of public housing, Buchanan

v. Warley, supra; in public education, the School Segrega

21

tion Cases, supra; and in interstate commerce, Henderson

v. United States, supra; and yet would constitute a valid

exercise of governmental authority in the field of intra

state commerce.

And to paraphrase this Court’s opinion in the Dawson

case, it is obvious that racial segregation in intrastate

transportation can no longer be sustained as a proper exer

cise of a state police power, for if that power cannot be

sustained where enforced commingling must necessarily

result, it cannot be sustained with respect to intrastate

carrier facilities, the use of which is entirely optional.

For these reasons we think this Court must strike down

the state policy here involved as prohibited by the Four

teenth Amendment, in spite of the fact that the Plessy

decision has not yet been specifically overruled by the

Supreme Court in the field of intrastate commerce.

C. T h e Suprem e C ourt’s A p p roach to th e In ter

sta te C om m erce A ct Is a C lear In d ication T hat

th e S ta te P o licy H ere Involved Is U n con stitu

tional.

The Supreme Court in interpreting Section 3(1) of the

Interstate Commerce A ct5 has construed this provision as

if the mandate of the equal protection clause of the Four

teenth Amendment and the mandate of equality in Section

5 Section 3(1) of the Interstate Commerce Act is as follows:

“It shall be unlawful for any common carrier subject to

the provisions of this part to .make, give, or cause any undue

or unreasonable preference or advantage to any particular

person, company, firm, corporation, association, locality, port,

port district, gateway, transit point, region, district, territory,

or any particular description of traffic, in any respect what

soever; or to subject any particular person, company, firm,

corporation, association, locality, port, port district, gateway,

transit point, region, district, territory, or any particular

description of traffic to any undue or unreasonable prejudice

or disadvantage in any respect whatsoever: * * *”

2 2

3(1) were one and the same. Even such subsidiary concepts

read into the equal protection clause—as the personal and

present nature of the right, McCabe v. Atchison Topeka <&

Santa Fe Ry. Co., 235 U. S. 131, and that equality is not

accorded by indiscriminate discrimination, Shelley v. Krae-

mer, supra■—are now a part of the definitive meaning- and

scope of Section 3(1). See Mitchell v. United States, 313

U. S. 80, 97; Henderson v. United States, supra at 824 and

825.

A reading of Henderson v. United States, makes it clear

that Section 3(1) prohibits the segregation of Negi’o and

white passengers in interstate commerce. There the Su

preme Court struck down a carrier regulation which sought

to segregate Negro and white passengers in the use of

dining- car service.

When the cause was before the Interstate Commerce

Commission, the controversy centered around a regulation

of the Southern Railway Co. pursuant to which two tables

at the end of its dining cars were left open for Negro

passeng’ers. When Negroes were seated and served at those

tables, curtains were drawn shutting them off from the rest

of the car. If, however, white passengers sat at these

tables before Negroes sought service, in spite of the fact

that there were empty tables in other parts of the dining

room, Negroes could not be served until these end tables

were again free.

This regulation was attacked before the Commission as

violative of the Interstate Commerce Act. The Commis

sion upheld the regulation, Henderson v. Southern Rail

road, 258 ICC 413, but the United States District Court

for the District of Maryland found the regulation violative

of the Interstate Commerce Act, 63 F. Supp. 906.

Thereafter, the carrier promulgated a new regulation

which provided that one table seating four persons would

be reserved exclusively and unconditionally for Negro

23

passengers and that the rest of the tables in the cars would

be for the exclusive use of white persons. A curtain or

partition was to separate the table for Negro passengers

from the rest of the tables in the dining car. The Com*

mission found this modified ruling conformed to the re

quirements of the Act, 269 ICC 78, and the District Court,

with Judge Soper dissenting, upheld the Commission’s

order, 80 F . Supp. 32. On appeal the Supreme Court

struck the regulation down.

The Court said at 824, 825:

. . . The right to be free from unreasonable dis

criminations belongs, under § 3(1 ), to each par

ticular person. Where a dining car is available to

passengers holding tickets entitling them to use it,

each such passenger is equally entitled to its facilities

in accordance with reasonable regulations. The denial

of dining service to any such passenger by the rules

before us subjects him to a prohibited disadvantage.

Under the rules, only four Negro passengers may be

■served at one time and then only at the table reserved

for Negroes. Other Negroes who present themselves

are compelled to await a vacancy at that table, al

though there may be many vacancies elsewhere in

the diner. The railroad thus refuses to extend to

those passengers the use of its existing and unoccu

pied facilities. The rules impose a like deprivation

upon white pas-sengers whenever more than 40 of

them seek to be served at the same time and the

table reserved for Negroes is vacant.

We need not multiply instances in which these

rules sanction unreasonable discriminations. The

curtains, partitions and signs emphasize the artifici

ality of a difference in treatment which serves only

to call attention to a racial classification of passen

gers holding identical tickets and using the same pub

lic dining facility . . . They violate § 3(1 ).

24

Our attention has been directed to nothing which

removes these racial allocations from the statutory

condemnation of ‘undue or unreasonable prejudice

or disadvantage.. . . ’

The carrier argued that the regulation should be sus

tained on the ground that the allocation of space was fair

and equitable in view of the lack of demand for dining

car space by Negro passengers. The Court held, however,

the regulation constituted a denial of equality required by

Section 3(1) because of the possibility that Negro passen

gers might be denied dining car service even though there

was available space in that portion of the dining car re

served for white persons.

On this point the Court stated at 825:

It is argued that the limited demand for dining-

car facilities by Negro passengers justifies the regu

lations. But it is no answer to the particular pas

senger who is denied service at an unoccoupied place

in a dining car that, on the average, persons like him

are served. As was pointed out in Mitchell v. United

States, 313 U. S. 80, 97, 81 L. ed. 1201, 1212, 61 S. Ct.

873, “ the comparative volume of traffic cannot jus

tify the denial of a fundamental right of equality of

treatment, a right specifically safeguarded by the

provisions of the Interstate Commerce Act.” . . .

That the regulations may impose on white pas

sengers, in proportion to their numbers, disadvan

tages similar to those imposed on Negro passengers

is not an answer to the requirements of §3(1).

Discriminations that operate to the disadvantage of

two groups are not the less to be condemned because

their impact is broader than if only one were affected.

The considerations which led Judge Soper to dissent

from the judgment sustaining the Commission’s second

25

order—see 80 F. Supp. 32, 39—were adopted and ex

panded by the Supreme Court. Under the Henderson

formula it is impossible to maintain segregation in rail

road dining cars, because no regulation requiring segrega

tion in an area of limited space can avoid the possibility

that a Negro might be denied service or use of a facility

when space is available in the section reserved for other

racial groups.

The reasons which led to a rejection of the car

rier regulation in Henderson apply with equal force here.

No Negro or white person may occupy contiguous space

on the same seat on appellee’s bus under South Carolina

law. Thus, situations must occur when a seat is available

beside a white person on the carrier and all the seats are

filled which, under state law and carrier practice, Negroes

may properly occupy. A Negro entering the bus must

stand even though there is available space in the section

of the bus reserved for white persons. Under the Hender

son formula this constitutes a denial of equality.

Because of the parallelism between the Supreme Court’s

approach to the Interstate Commerce Act and its approach

to the Fourteenth Amendment, it is doubtful that the Court

would now construe the Fourteenth Amendment as per

mitting segregation in intrastate commerce under the

“ separate but equal” doctrine when it would be forbidden

under Section 3(1) of the Interstate Commerce Act.

Placement of the Henderson case is also of considerable

importance. It should be noted that while Henderson does

not prohibit segregation in terms, it does so in effect. It

should also be remembered that Henderson was de

cided at the same , time as McLaurin v. Oklahoma State

Regents and Sweatt v. Painter, supra, which accomplished

the same result in the field of public education These

latter cases were followed by the School Segregation Cases

in which the “ separate but equal” doctrine was expressly

26

repudiated. It is logical to assume that the Court, when

again faced with this question in the field of transportation,

will decide the issue squarely and in the same manner as

in the field of public education. Again, we submit, it is

highly doubtful that the Court would apply one standard

to one field with respect to equal protection and due process

* and another standard here, especially in the light of its

approach to Section 3(1) of the Interstate Commerce Act.

D. T h is C o u r t Is N o t B o u n d to a B lin d A d h e re n c e

to P le ssy v. F e rg u so n M e re ly B e c a u se th e

S u p re m e C o u rt H a s N o t E x p re ss ly R e je c te d

I ts A u th o r i ty in I n t r a s ta te C o m m erce .

The unmistakable trend is away from support for the

“ separate but equal” doctrine and in the direction of hold

ing legislative classifications and distinctions based upon

race violative of the Fourteenth Amendment. In the area

here involved, as we have already indicated, while the doc

trine has not been specifically overruled, its rationale is

not now followed—-and it has been repudiated in other

fields. This situation bears striking similarity to that

facing the Southern District of West Virginia in Barnette

v. State Board, 47 F. Supp. 251 (1942), aff’d, 319 U. S.

624. There the Court had to decide whether to apply the

doctrine enunciated in Minnersville School District v. Go-

hitis, 310 U. S. 586 which was technically controlling, or to

reject that doctrine in light of subsequent defection from

the Gobitis doctrine by a majority of the Supreme Court.

The court felt that judicial responsibility compelled it to

reject Gobitis and to hold the flag salute requirement uncon

stitutional under the First Amendment. There it was said

at pages 252-253:

Ordinarily we would feel constrained to follow

an unreversed decision of the Supreme Court of the

United States, whether we agreed with it or not. It

is true that decisions are but evidences of the law and

not the law itself; but the decisions of the Supreme

27

Court must be accepted by the lower courts as bind

ing upon them if any orderly administration of

justice is to be attained. The developments with

respect to the Gobitis case, however, are such that

we do not feel that it is incumbent upon us to accept

it as binding' authority. Of the seven justices now

members of the Supreme Court who participated in

that decision, four have given public expression to

the view that it is unsound, the present Chief Justice

in his dissenting opinion rendered therein and three

other justices in a special dissenting opinion in

Jones v. City of Opelika, 316 U. S. 584, 62 S. Ct.

1231, 1251, 86 L. Ed. 1691. The majority of the court

in Jones v. City of Opelika, moreover, thought it

worthwhile to distinguish the decision in the Gobitis

case, instead of relying upon it as supporting author

ity. Under such circumstances and believing, as we

do, that the flag salute here required is violative

of religious liberty when required of persons hold

ing the religious views of plaintiffs, we feel that we

would be recreant to our duty as judges, if through

a blind following of a decision which the Supreme

Court itself has thus impaired as an authority, we

should deny protection to rights which we regard as

among the most sacred of those protected by consti

tutional guaranties.

The present case is even more compelling because this

Court has for guidance the School Segregation Cases

which clearly and concisely define the scope and reach of the

Fourteenth Amendment with respect to the basic question

involved—the validity of state enforced racial segregation.

It is true, of course, that those cases apply to public educa

tion and the instant case involves intrastate commerce.

Yet, when decision must be made concerning the validity

of racial segregation in other areas, it would seem more

appropriate to follow the School Segregation Cases, than

28

a discredited decision which is now at variance with the

whole trend of constitutional development.

The possibility of reaffirmation of the Plessy doctrine

by the Supreme Court in view of the present status of the

law seems remote indeed, and recognition of this is im

plicit in this Court’s opinion in the Dawson case. Under

the circumstances, we urge the rejection of the Plessy

formula and application of the doctrine applied by the

Supreme Court in the School Segregation Cases and by this

Court in the Dawson Case.

CONCLUSION

For the r e a s o n s h e r e i n a b o v e stated, it is respectfully

submitted t h a t t h e judgment o f t h e court below should

be reversed.

P h il ip W itten b er g ,

306-308 Barringer Building,

Columbia, South Carolina,

R obert L. C arter ,

T httkgood M a rsh a ll ,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York,

Attorneys for Appellant.