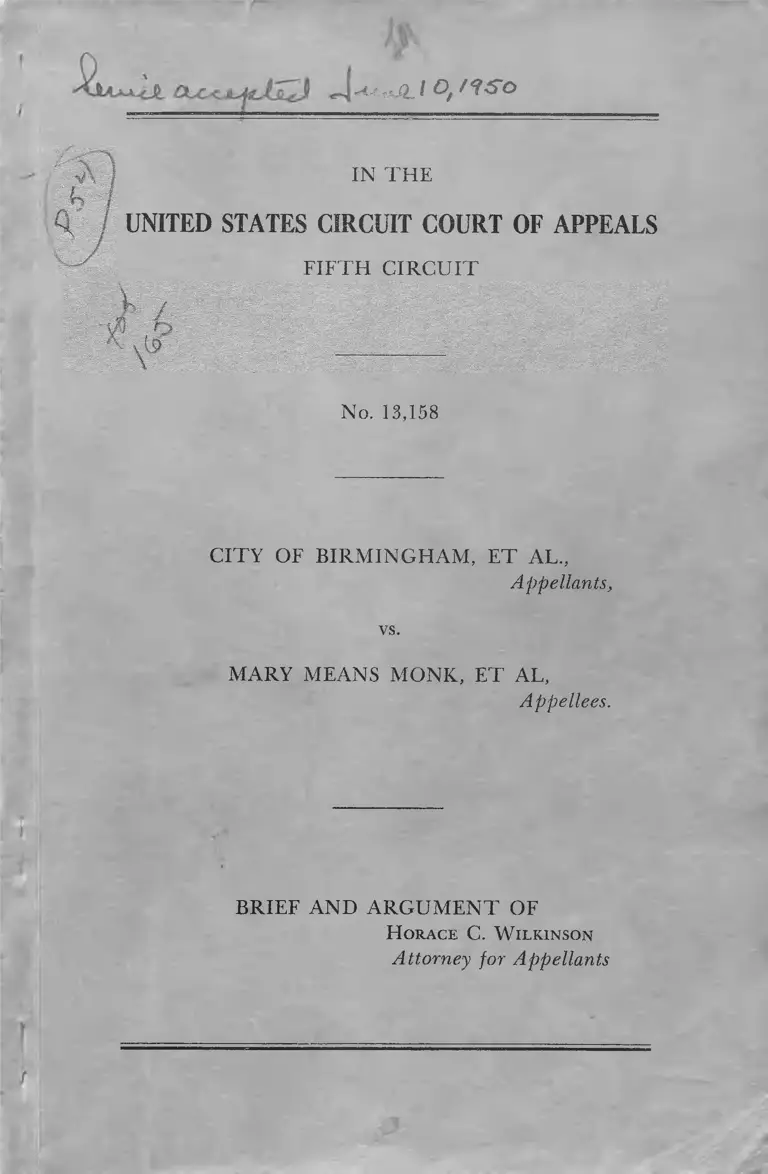

City of Birmingham v. Monk Brief and Argument of Horace C. Wilkinson

Public Court Documents

June 1, 1950

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of Birmingham v. Monk Brief and Argument of Horace C. Wilkinson, 1950. ba4ad4ea-c69a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/82c91c80-4cfa-4123-bb85-83887224d084/city-of-birmingham-v-monk-brief-and-argument-of-horace-c-wilkinson. Accessed March 10, 2026.

Copied!

mJu j l I O, / is o

IN THE

UNITED STATES CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS

FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 13,158

CITY OF BIRMINGHAM, ET AL.,

Appellants,

vs.

MARY MEANS MONK, ET AL,

Appellees.

BRIEF AND ARGUMENT OF

H orace C. W ilk in so n

Attorney for Appellants

SUBJECT INDEX

Page

Staetment of the Case____________________________________ I

The Facts _____________________________________________ 7

Proposition of Law_____________________________________ 29

Assignment of Error_____________________________________ 34

ARGUMENT

Proposition I

a. The court erred in holding that this case is ruled by

Buchanan v. Warley________________________________ 42

b. The zoning ordinances do not “take” property without

due process _______________________________________ 50

c. A non-absolute right may be restricted by legislation----- 52

d. The City Commission believes that its zoning ordinance

does not conflict with the 14th Amendment----------------- 56

e. Long and repeated recognition of validity of ordinance— 57

Proposition II

a. Social and economic data admissible and material-------- 60

b. Constitutional interpretation is more than a rule of

thumb ___________________________________________ 66

c. Segregation is not forbidden by U. S. Constitution-------- 69

Proposition III

a. Residential segregation socially desirable----------------- — 73

b. Residential segregation discourages debasement of bloods 77

c. Residential segregation is advantageous to the Negro----- 93

d. Residential segregation lessens racial antipathies----------- 94

e. Residential segregation makes each race more at ease----- 96

f. Equitable segregation ______________________________ 98

Proposition IV

Residential segregation is essential to peace and order----------102

Proposition V

Equitable segregation is economically desirable-------------- 114

Proposition VI

a. Residential segregation the most practical solution----- 137

b. The nature of race conflict__________________________ 143

c. The city’s right to preserve racial integrity-------------------145

SUBJECT INDEX (Cont.)

Page

Proposition VII

The use of property may be regulated under the Police

pow er--------------------------------------------------------1________149

Proposition VIII

The difference between the races affords a sound basis for

the exercise of the police power______________________

a. The marked differences_____________________________ 156

b. Science of Government_____________________________ 160

c. Military Value ____________________________________162

Proposition IX

An impracticable construction of the Constitution will be

avoided ___________________________________________ 164

Conclusion __________________________________________ 165

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS

City Code of Birmingham (1944)

Sections 1604 and 1605

(Supp. Ord. No. 709-F)

Chapter 57

Section 1645

Code of Alabama (1940)

Title 62-Sec. 719

” 62-Sec. 711

” 14-Sec. 360-361

” 16-Sec. 7

” 27-Sec. 11

ACTS OF ALABAMA

Acts 1909—Page 392

Acts 1915—Page 294—Sec. 6

Alabama Constitution (1901)

Sec. 102

Sec. 256

Sec. 182

Text Books

Cooley’s Constitutional Limitations

Vol. II—Page 1317

BIBLIOGRAPHY

THE APPRAISAL JOURNAL-January 1944

PRINCIPLES OF CITY LAND VALUES

(Hurd) 77-78

21 ILLINOIS LAW REVIEW-716

APPRAISAL JOURNAL, February, 1940

(A Source of Property Value)

THE STATE (Woodrow Wilson) Page 592

EBONY (May, 1949) Page 18

SELECTED ESSAYS ON CONSTITUTIONAL LA W -

Vol. 2, Pages 1175-1176 and 1193, 1179, 1180, 1194.

HARVARD LAW REVIEW, Vol. 38, Page 6

MICHIGAN LAW REVIEW-Vol. 24, Page 17

MILTON R. KNOVITZ (Irene Morgan case)

PENNSYLVANIA LAW REVIEW-Vol. 79, Page 665

ILLINOIS LAW REVIEW, Vol. 21, Pages 704-716

THE NATION (August, 1947) Page 123

NEW YORK COMMISSION REPORT-Page 74

PENNSYLVANIA COM. REPORT, Page 131

COLLIER’S WEEKLY (November 3, 1946)

NEGRO GHETTO, Pages 167-170

W HAT THE NEGRO WANTS (R. W. Logan), Pages 7, 28

THE NEGRO IN CHICAGO

NEGRO DIGEST (December, 1944) Page 31

WHAT THE NEGRO WANTS (DuBois), Pages 65, 66

AMERICAN JOURNAL ON SOCIOLOGY, Vol. 50-Page 351

DEUTERONOMY, Chapter 23, V-2

HEBREWS, Chapter 12-V6-8

AMERICAN INSTITUTIONS AND TH EIR PRESERVATION

(Cook)

BALFOUR, SIR ARTHUR JAMES

MY THREE YEARS IN MOSCOW (Smith), 285, 268

WHERE I WAS BORN AND RAISED (Cohn, 1949), Page 156

DOWD, Professor

RACE AND NATIONALITY (Fairchild, Professor), Page 88

THE CRADLE OF TH E CONFEDERACY (Hodgson)

NEGRO HOUSING, Page 213

THE NEGRO IN AMERICAN LIFE, Pages 474, 476

TOOMBS, SENATOR ROBERT

THE AMERICAN RACE PROBLEM (1927)

PLANNING FOR THE SOUTH (Sickle)

BISHOP, Reporter

BIBLIOGRAPHY (Cont.)

PRICE, BEN

PEOPLE v. PROPERTY

ROCKY MOUNTAIN LAW REVIEW (Vol. 18)

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF REALTORS CODE

HOUSING FOR THE MACHINE AGE

THE REVIEW OF THE SOCIETY OF

RESIDENTIAL APPRAISERS

UNDERWRITING MANUAL (FHA) (1935)

TH E INSURED MORTGAGE PORTFOLIO

PUNISHMENT W ITHOU T CRIME

TH IRD NATIONAL MUNICIPAL REVIEW (July, 1914)

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF LAND VALUES IN CHICAGO

(Hoyt)

THE NEGRO PROBLEM (1914)

TABLE OF CASES

Page

Borden’s Co. v. Baldwin, 293 U. S. 194___________________ 32, 67

Boyer v. Garrett, MMS U. S. Dist. Ct., Maryland, Dec. 30,

1949 ______________________________________________ 31, 54

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60----------------------- 29, 41, 50, 52, 56

Buck v. Bell, 274 U. S. 200__________________________30, 46, 75

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296------------------------ 29, 33, 44

Cassee Realty Co. v. Omaha, 144 Neb. 753-----------------------------33

Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education, 175

U. S. 528 _________________________________________ 32, 71

Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Corp., 87 N. E. (2d) 241----------------32

Eldridge v. Trezevant, 160 U. S. 452------------------------------------ 58

Elmore County v. Tallapoosa County, 221 Ala. 182--------- -—31, 57

Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U. S. 365____________ 29, 30, 45

Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337------------------------------------------32, 72

Gompers v. U. S. 233 U. S. 604____________________________ 32, 66

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78___________________________ 32, 71

Hadacheck v. Sebastian, 239 U. S. 394-------------------------------- 29, 44

Henderson v. U. S., 80 Fed. Supp. 32-----------------------------------31, 54

Holden v. Hardy, 169 U. S. 366------------------------------------------- 33

Hirabayashi v. U. S., 320 U. S. 81-----------------------------------30, 45

Jackman v. Rosenbaum, 260 U. S. 22------------------------------------ 58

Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U. S. 11------------------ 30, 46, 64, 74

TABLE OF CASES (Cont.)

Page

Kyle v. Abernathy, 46 Colo. 214_________________________31, 57

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214_________________ 30, 45

Laurel Hill Cemetery v. San Francisco, 216 U. S. 358 (1910)___ 58

Miller vs. Schoene, 276 U. S. 272____________________________33

Miller v. Oregon, 208 U. S. 412___________________ 30, 46, 65, 76

Munn v. Illinois, 94 U. S. 113______________________________29

Nectow v. City of Cambridge, 277 U. S. 183______________ 32, 33

Noble State Bank v. Haskell, 219 U. S. 104__________________ 33

Norton v. Randolph, 176 Ala. 381______________________ 30, 47

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633_____________________ 29, 45

Pace v. State, 69 Ala. 231_______________________________30, 53

People v. Gallagher, 45 Amer. Report 232___________________ 70

People v. School Board, 161 N. Y. 598___________________ 32, 72

Pierce Oil Company v. Hope, 248 U. S. 498_______________ 29, 44

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537_______________ 30, 31, 53, 58, 97

Prudential Insurance Co. v. Cheek, 259 U. S. 530_________ 31, 55

Roberts v. City of Boston, 5 Cush. 198______________________71

Reinman v. Little Rock, 237 U. S. 171___________________ 29, 44

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631 (1948)_____________ 72

St. Anthony Falls Water Power Co. v. Board of Water Com

mission, 168 U. S. 349 (1897)____________________________58

State v. Board of School Comm., 226 Ala. 62_____________ 31, 54

State v. Board of Trustees, 126 Ohio St. 290_________________ 32

State ex rel Carter v. Harper, 182 Wis. 148, 196 N. W.

451 ------------------------------------------------------------------30, 47, 77

State v. Hillman, 110 Conn. 92____________________________ 33

Story v. State, 178 Ala. 98______________________________30, 81

Taylor v. Hackensack, 137 NJL 139_________________________ 33

Texas & N. O. R. R. v. Brotherhood R. & S. Clerks, 281 U. S.

548 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- 33

Traux v. Corrigan, 257 U. S. 312___________________________66

U. S. v. Caroline Products Co., 304 U. S. 144___________ 32, 67, 68

Vidalia v. McNelly, 274 U. S. 676 (1927)______________________58

Weaver v. Board of Trustees of Ohio State Univ., 126 Ohio

St. 290 ______________________________________________ 73

West Chester R. R. Co. v. Miles, 55 Pa. St. 209 (1867)-.4, 31, 54, 89

West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, 300 U. S. 379_________ 30, 33, 47

Worthington v. District Court, 37 Nev. 212_______________ 31, 57

IN THE

UNITED STATES CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS

FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 13,158

CITY OF BIRMINGHAM, ET AL.,

Appellants,

vs.

MARY MEANS MONK, ET AL,

Appellees.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is an appeal from a final judgment rendered by the

United States District Court in Birmingham, Alabama, in

favor of Mary Means Monk and fourteen other Negroes

against the City of Birmingham, a municipal corporation,

H. E. Hagood, its Building Inspector, and Commissioner

James W. Morgan, in whose department the zoning law

is administered.

The court declared Sections 1604 and 1605 of the City

Code of Birmingham (1944) and a supplementary ordi

nance No. 709-F, unconstitutional and ordered an injunc

tion against their enforcement. (R. p. 263) . The ordi

nances are set out in the appendix.

Sections 1604 and 1605 are a part of the basic zoning

law of Birmingham. They make it unlawful for a Negro,

with some minor exceptions, to occupy property for resi

dential purposes in an area zoned A-l or white residential

and for a white person to occupy property for residential

purposes in an area zoned B-l or negro residential.

2

The plaintiffs filed a complaint in the District Court

(R. p. 1) in which they claimed that Sections 1604 and

1605 and supplementary ordinance No. 709-F were un

constitutional because they prevented the plaintiffs from

constructing and occupying residences upon certain real

estate in the Graymont-College Hills section of Birming

ham which has been zoned white residential since 1926.

The plaintiffs claimed that they were negroes and that

they were excluded from that area, by the zoning ordinance,

solely because of their race or color. They averred that

Mary Means Monk had applied for and had been denied

a permit to build and occupy a house as a residence in said

area and that all other negroes will be denied a permit to

build and occupy a residence on any lots they own in said

area because said lots are in a white residential zone. They

asked the court to injoin the enforcement of Sections 1604

and 1605 of the City Code of Birmingham and said Ordi

nance No. 709-F and to render a judgment declaring said

ordinances unconstitutional, null and void.

The defendants filed an answer (R. p. 19) in which

they denied that the plaintiffs are prevented from living

on the property they claim to own solely because of their

race and color. The defendants set up that the classifi

cation of certain areas in the City of Birmingham in its

zoning ordinances as white residential sections and negro

residential sections is based... in part, upon the difference

between the white and negro races and not solely upon race

or color. The defendants denied that the zoning ordi

nances are unconstitutional.

With respect to the origin and operation of the basic

zoning ordinances in Birmingham the defendants averred

(R. p. 22) :

“. . . . The zoning ordinances of the City of Birming

ham were adopted more than twenty years ago after pro

tracted public hearings in which each class of citizen

ship in Birmingham was represented and heard, that it

3

embraced a comprehensive plan for zoning in line with

the best thought in the Nation on the subject of zoning

and that said plan embodied in said zoning ordinances

has been highly successful in its operation for twenty

years or more and has contributed by stabilizing property

values in the respective zones to the material prosperity

and progress of the City of Birmingham, that it has alle

viated racial friction and race tension and has contributed

to the public peace and the public welfare to a marked

degree. Defendants aver that said ordinance is a valid

and legal exercise of the police power of the City of Bir

mingham which by specific statutory enactment is com

mensurate with the police power of the State of Alabama

and is a power that is inalienable and cannot be sur

rendered by the City of Birmingham, Alabama, or by

the State of Alabama.”

The defendants set up in their answer that the most

exceptional circumstances not only justify but require the

classification made by the zoning ordinances and that the

enforcement of the zoning ordinances is imperative.

The defendants averred that,

“ There has been dynamiting, rioting, violence, dis

order and damage to property in the areas in which the

plaintiffs claim to own property on recent previous oc

casions when negroes attempted to occupy property in

said area zoned white residential. . .

The defendants further averred:

• ■ • • That should the plaintiffs undertake to occupy

the property they claim to own, there is a clear, grave

and present danger of a race riot, violence and loss of

life and tremendous property damage, all of which will

likely or probably follow such action and which cannot

be prevented by any amount of police protection that

the City of Birmingham or the State of Alabama is able

to afford. . . .” (R. p. 20).

4

The defendants further averred that if the plaintiffs

undertook to occupy the property they claim to own that,

“• • • • The lives of a large number of citizens, white

and negro, in Birmingham would be jeopardized and the

public peace and order disturbed to a marked degree.. .

The defendants further averred that an overwhelming

majority of white and colored citizens in Birmingham favor

residential segregation as the same is established by the

zoning ordinances referred to in the complaint and that

said white and negro citizens recognize that said residential

segregation is advantageous to both races and in the in

terest of both races and in the public interest for the fol

lowing reasons:

(a) Racial antipathies would be lessened. Because of

differences between the races, resulting from different

cultural backgrounds and different physical make-ups, a

natural prejudice prevents harmony. By keeping one sepa

rated from the other it follows that the prejudice will mani

fest itself less frequently.

(b) Each race would be more at ease—the white be

cause it has a distaste for the colored, and the colored be

cause it would feel less imposed upon and more inde

pendent. This, no doubt, is one of the important elements

prompting various legislatures to enact laws separating the

races in trains, schools and cities.

(c) Because of this feeling of independence the negro,

as a race, would be more progressive. There would be

greater incentive for him to move forward in that he would

feel he was improving his own castle rather than that of the

white man. Mr. Shannon says that with segregation “all

would have better opportunity to develop along normal

lines toward racial self-sufficiency, racial self-respect, and

racial self-reliance.”

(d) There would be less miscegenation. West Chester

R. R. Co. v. Miles, 55 Pa. St. 209 (1867), states that co-

U /JU .

5

yMJd IV

?;\ ■ ' J j® * s

mingling of the races even on street cars was pernicious fori

the very reason that “the tendency of intimate social inter

mixture is to amalgamation contrary to the law of races ” I

(R. p. 21).

The defendants further set up that:

“The white and colored citizens in Birmingham have

abided by the zoning ordinances referred to in the com

plaint for more than twenty years prior to the filing of

the complaint and that by unanimous consent up to the

filing of the complaint abided by and respected the

classifications established by the zoning board and ap

proved by the Commission of the City of Birmingham,

Alabama, as provided in said zoning law and as a result

there has been developed in the City of Birmingham a

well established and well recognized custom which has

crystalized into a contract between the whites and negro

citizens in Birmingham to the effect that the members of

each race will abide by and respect the classifications

established by the zoning board and that the members

of one race will not undertake to occupy property for

residential purposes that is located in an area zoned for

residential purposes for the members of the other race.

Based on that agreement and the aforesaid recognition

of the said classifications for more than twenty years,

thousands of white citizens have built their homes in

areas zoned white residential and thousands of colored

citizens have built their homes in areas zoned negro

residential area relying upon the aforesaid agreement and

custom and its observances for a period of twenty years

fully confident that the area zoned white residential

would not be invaded by negroes and that the area zoned

negro residential would not be invaded by members of

the white race until the respective zoning classifications

were changed by the zoning board in the way and man

ner provided by said zoning ordinances.” (R. p. 28) .

In addition to the calamity in the form of a race war

which will result from the plaintiffs being allowed to live

in a white residential section, the defendants averred that

6

residential property in Birmingham, white and colored

alike, would immediately depreciate in value from twenty-

five to fifty percent if the Birmingham zoning law is nulli

fied and as a result,

. . . . The municipal revenue would be so greatly

diminished as a result of the depreciation in property

values that the City of Birmingham would be unable to

render the necessary fire, police, health, street and light

service to white and black that is necessary and essential

that the education of white and black in Birmingham

would be greatly impaired as a result of the diminution

in municipal revenue and that the comfort, peace and

progress of both races would be disturbed and arrested

and all municipal services to both races materially im

paired as a result of the diminution in revenue resulting

from the decrease in property values. . . (R. p. 29).

In addition to injuries suffered by the City of Birming

ham in its corporate capacity, the defendants averred that:

“. . . . Thousands of property owners in Birmingham,

white and colored alike will suffer irreparable injury and

damage if the plaintiffs are allowed or permitted to upset

or overturn the arrangement that has prevailed in the

City of Birmingham for more than twenty years, and that

it would be inequitable to allow the plaintiffs to disturb

the aforesaid arrangement which is essential to peace and

order and the preservation of life and property values

in the City of Birmingham.” (R. p. 30) .

The defendants also averred that the human rights of

the citizens of Birmingham to freedom from disorder is

superior to any property rights asserted by the plaintiffs.

That claim was made in the following language:

“Defendants aver that the human right of hundreds

of thousands of negroes and whites in the City of Birm

ingham to peace and order and freedom from race war

and race riots, that their right to life, liberty and the

7

pursuit of happiness is superior to any alleged right of

the plaintiffs to occupy property they claim to own which

they admit they purchased with full knowledge of the

restrictions placed on its occupancy by the City of Birm-

ham, Alabama, which have been acquiesed in, accepted

and abided by the citizens of both races for more than

twenty years. The defendants aver that the aforesaid

human rights are paramount to any property rights as

serted by the plaintiffs.”

The defendants also set up that plaintiffs could take an

appeal to the Board of Adjustment from the refusal of the

administrative officer, H. E. Hagood, to issue the building

permit and that Mary Means Monk had not availed her

self of the right of appeal provided for in Section 719,

Title 62, Alabama Code of 1940. (R. p. 27).

THE FACTS

The City of Birmingham is an Alabama municipal cor

poration. It lies mostly in Jones Valley between two moun

tains. One on the North and one on the South and has a

population of about four hundred thousand people. More

than forty percent of its population are negroes.

Prior to 1910 the territory now within the corporate

limits of the City of Birmingham consisted of the City of

Birmingham and eleven other municipalities lying East,

West and North of Birmingham. There were one or more

white and one or more colored residential districts in each

of these outlying communities.

In 1909 the boundary lines of the City of Birmingham

were altered or rearranged so as to include within the cor

porate limits of the City of Birmingham the territory then

included within the eleven municipalities, effective Jan

uary 1, 1910. Acts 1909, page 392.

In 1915 the legislature of Alabama conferred upon the

City of Birmingham express authority to prevent conflict

and ill feeling between the races and delegated to Birming-

8

ham full, complete and unlimited police power possessed

by the State of Alabama in so far as it is possible for the

legislature of Alabama under the Constitution of Alabama

and of the United States to delegate such powers. Acts

1915, page 294, Section 6.

In 1923 the legislature of Alabama expressly empowered

the legislative body of the City to establish a zoning com

mission and to classify inhabitants by regulations, which

will not discriminate in favor of or against any class of in

habitants. Alabama Code 1940, Title 62, Section 711.

The City employed the well known engineering firm of

Morris Knowles of Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, to prepare a

comprehensive zoning plan for the City of Birmingham.

After several years study and innumerable public hearings

in which all races, classes and interests were heard at length,

the City was zoned by a basic zoning ordinance which is

now Chapter 57 of the General City Code of Birmingham

of 1944, Generally speaking, the City was divided by this

ordinance into five districts, white residential, negro resi

dential, commercial, light industrial and heavy industrial.

The white and negro residential districts were in turn sub

divided in A-l residential for white, B-l residential for

negroes, A-2 residential for whites, and B-2 residential for

negroes. In the white residential districts no building or

part thereof shall be occupied or used by a person of the

j negro race, with minor and unimportant exceptions. In

L the negro residential districts, no building or any part

j thereof shall be occupied or used by any person of the

white race, with certain minor and unimportant exceptions.

It is made the duty of the Chief Building Inspector of

the City to administer and enforce the zoning law and a

right of appeal from the decision of the administrative offi

cer may be taken to the Board of Adjustment by any per

son aggrieved under Section 1645, Birmingham Code, 1944.

In the basic zoning map which was introduced in evidence

as defendants Exhibit 2, it appears that there are thirty-

seven negro residence areas in Birmingham plus a thirty

acre tract known as Taylors Hill in a white residential zone

which has not been disturbed because it was occupied by

negroes at the time the City was zoned in 1926. It is en

tirely surrounded by a white residence area.

George R. Byrum, Jr., Chairman of the Board of Ad

justment testified (R. p. 78) that the percentage of the

vacancies in the different residence areas was substantially

uniform throughout and that all of the negro areas are

from 90 to 92 percent improved and that about 8 or 10

percent of each respective area is vacant and available for

improvement.

This was based on an actual inspection of the property

made the week before the trial in the District Court.

A map of the area in which the lots owned by the plain

tiff are located was introduced in evidence as defendants

Exhibit 1. This map shows that the streets in that dis

trict run north and south and the Avenues east and west.

All of the property west of Center Street between 9th

Avenue and 11th Avenue, a distance of four blocks, is

zoned white except six lots on the east side of block 36.

Blocks 40 and 46 between 11th Avenue and 11th Court

West on Center Street are also zoned white. West of

Center Street between 9th Avenue and 11th Avenue for

more than a mile is zoned white. Lots owned by the plain

tiffs are located in Blocks 37, 38, 39, 40 and 47, all of which

are exclusively white blocks.

The evidence is to the effect that Mary Means Monk

applied for a building permit to erect a dwelling or a house

on a lot in Block 37 which she proposed to occupy as a

residence. (R. p. 54) . The building inspector examined I

the plans and specifications for the dwelling and found

they were in compliance with the structural requirements

of the building code of the City of Birmingham, but the

issuance of the building permit applied for was refused

because the purpose for which the property was to be used

10

would violate Sections 1604 and 1605 and Ordinance 709-F

above referred to.

Commissioner James W. Morgan testified (R. p. 91)

that the building inspector was in his department and under

his immediate supervision and that he refused to have Mr.

Hagood issue the permit on the grounds that Mary Means

Monk’s property was in a white district and that it is his

policy that no permits are issued to negroes who propose

to build homes and occupy them in a white residential

section. Mr. Morgan testified that this policy was based

on the custom that had been observed throughout the years,

that he thought it best for white people to have their own

area to live in and their own places of worship to attend

and their own schools. Mr. Morgan testified that during

the 12 years he had been on the City Commission, the

white and colored areas of Birmingham had been well ob

served by members of both races until recently. This ques

tion was propounded to Mr. Morgan:

“Q. In your opinion, I wish you would tell the court

whether or not the zoning ordinance as drafted, approved

and enforced and applied and construed and administered

has been conducive to public peace and order.”

The plaintiff’s objection was sustained on the ground

that under Buchanan versus Warley that is most certainly

not in issue. (R. p. 94) .

The defendants offered to show that the ordinance had

been conducive to public peace and order.

This question was propounded to Mr. Morgan:

“Q. Mr. Morgan, if the custom that has been observed

here with respect to the residential sections, white and

colored, by both races since you have been on the Com

mission is upset or overturned, what in your judgment

will be the effect on property values, residential property

values, in the City of Birmingham?

The plaintiffs objection was sustained and the defend

ants offered to show that it would result in a very sub

stantial decrease in ad valorem residential value. (R. p. 95) .

This question as propounded to Commissioner Morgan:

“O. I would be glad if you would state to the court

what in your judgment and opinion as a member of the

Commission of the City of Birmingham would be the re

sult on the City finances and its ability to render municipal

services such as fire, police, health, street improvements,

education, and matters of that kind, if a substantial de

crease in municipal revenue is brought about by a disre

gard of the custom that has prevailed for 12 years with

respect to the residential zoning?

The plaintiffs objection was sustained and the defend

ants offered to show that it would impair the City’s ability

to the extent that it would probably not be able to render

those essential services to the extent required and necessary

and essential for the comfort and convenience of the citi

zens. (R. p. 96) .

Commissioner Morgan further testified that the zoning

ordinance was enacted to preserve peace and order in the

community and for the best interest of all concerned and

that the zoning ordinance was the reason why the building

permit was denied.

The defendants offered to show that in the immediate

territory of plaintiff’s lots six bombings had occurred with

in the last few months as a result of the attempt of the

negroes to invade that territory. The court refused to

allow evidence of that character to be introduced. (R.

p. 98).

Commissioner Morgan further testified that in his judg

ment and opinion and belief that there is a clear and grave

and present danger to the peace and public welfare in Bir

mingham from the upsetting of the custom that has grown

up under the zoning laws.

Commissioner Morgan testified (R. p. 102) that he ap

pointed a committee to work out the situation and that as

12

a compromise the City Commission re-zoned thirty-five

acres for negro residential property and that when the

committee for the NAACP (National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People) came before the Com

mission with such forceful demands, namely, that they

would not accept any compromise on this proposition, but

that segregation had to be abandoned in Birmingham, he

believed it had a strong bearing on the discontinuance of

any effort to be helpful. It certainly had that effect on

him. He further testified that he thought the action of

the NAACP made further action on the part of the Com

mittee futile at this time and that the demands of the

Graymont Civic Association which rejected the recommen

dation of the Zoning Board and the Committee did not

have anything to do with the Committee resigning. He

testified that the Graymont Civic Association is a civic

club of about one hundred residents of that area out there.

N. L. Thompson, Manager of the Western Union Tele

graph Company in Birmingham in response to a subpoena

duces tecum (R. p. ] 06) produced a number of telegrams

on file with the Western Union office in Birmingham for

transmission and delivery to President Truman, Attorney

General Tom C. Clark, A. A. Carmichael, Attorney Gen

eral of Alabama, Commissioner Eugene Connor, Walter

White, Chief of Police Floyd Eddins, which he testified

were transmitted and delivered by the Western Union Tele

graph Company. The first telegram dated August 13,

1949, informed Attorney General Carmichael that,

“Racial tensions made acute by Friday night bomb

ings of two ministers home. Situation demand swift

and sure attention. NAACP pleads for your office to

conduct a thorough investigation of every worth aspect

of the problem. Not one of six bombings of Negro

homes solved. Had it been the other way it is doubtful

outcome would be same. NAACP will not relax its

fight against racial zoning laws.” (R. p. 108) .

13

Telegram to President Truman on the same date in

formed him that:

“Violent unsolved bombings of negro homes rose to

six Friday night, August 12, in short span. Racial ten

sions sharp enough for unhappy possibilities. . . .”

(R. p. 109).

Telegram to Commissioner Eugene Connor on the same

date informed him that:

“Just three days after you allegedly warned that quote

we’re going to have bloodshed in this town unquote

unless white citizens have their way about racial zoning

homes of two negro ministers were bombed. These

two become the sixth negro homes to be bombed. Not

one arrest has been made. . . .” R. p. 110) .

Telegram to Attorney General Tom Clark on the same

date informed him that:

“. . . . Six negro homes bombed over short period

without single arrest. Racial tensions inflamed by un

fortunate utterances by one public official. Three days

after Commissioner Connor allegedly said quote we’re

going to have more bloodshed in this town unquote in

connection with the racial zoning question violence

came.” (R. p. 111).

Telegram to Commissioner Jimmy Morgan on the same

date informed him that:

“. • . . The NAACP will fight without let up all forms

of racial zoning because such is unlawful. We shall

continue to support and encourage negro citizens to

stand firm at all cost and sacrifices for the precious

right to own and live where one can buy or rent.

NAACP urges round the clock protection for negro

citizens in Smithfield area. Not one of six bombings of

negro homes have been cleared up. . . .” (R. p. 112) .

14

Telegram to the President of the City Commission,

Cooper Green, on the same date said:

. We urge day and night police protection for

the negro homedwellers in Smithfield area. . . (R.

p. 113).

Telegram to the Sheriff of Jefferson County, Holt Mc

Dowell, said:

“With two bombings Friday night, August 13, in

Birmingham the number has risen to six unsolved

bombings of negro homes. The community has been

inflamed by unfortunate statements attributed to at

least one city public official. . . .” (R. p. 114) .

All of these telegrams were signed by the Chairman, Exe

cutive Committee, Birmingham Branch NAACP.

In a telegram to Chief of Police Floyd Eddins dated June

2, 1949, it was said:

“A situation exists growing out of controversy over

racial residential zoning which demands hourly police

protection for Reverend Milton Curry of 1100 Center

Street North and Reverend E. B. Deyampert of 1104 Cen

ter Street North.”

This telegram was signed by the President of the Birming

ham Branch, NAACP.

On May 23, 1949, a telegram was sent to Attorney Gen

eral Tom Clark, saying:

“Urge conspiracy prosecution in case where Willie Ger

man of 1100 North 11th Avenue denied occupancy of

his home by threats and acts of Birmingham public offi

cials May 21, 1949.” (R. p. 117) .

President Truman was advised by telegram dated June 2,

1949, that:

15

“Because of fear that local police protection is break

ing down in Smithfield area where racial zoning contest

has provided controversy, the Birmingham Branch of

NAACP voted Thursday night to bring this to your at

tention. We urge that the prestige of the White House

be thrown behind efforts of negro citizens to have pro

tection here where their civil liberties are being threat

ened.”

These telegrams were sent by the Birmingham Branch

of the NAACP.

After the telegrams had been read in evidence without

objection, the court said:

“THE COURT: Those telegrams are in, but I don’t

see where they have any bearing on any issue in this

case.” (R. p. 118) .

E. A. Camp, Jr., testified (R. p. 120) that he was Vice-

President and Treasurer of the Liberty Life Insurance

Company and handled investments for that company.

That he was familiar with its policy with reference to mak

ing loans on white and colored property in Birmingham

and elsewhere. That his company makes loans on white

residential property and colored residential property where

in his opinion it is properly located and is good security

for a loan. He was asked this question:

“Q. What is the policy of the Liberty National Life

Insurance Company with reference to making loans on

white and colored residential property?”

Plaintiff’s objection was sustained and defendants offered

to show by this witness and other witnesses that the policy

of the Liberty National and other life insurance companies

is that they loan on white residential property where it is

zoned white and loan on colored residential property where

it is zoned colored. They do not loan on property that is in

a mixed zone or in a twilight zone or in the path of being

16

changed from one classification to the other. That sta

bilized conditions is one of the main factors taken into con

sideration in making loans on property.” (R. p. 122) .

The defendants also offered to show that the building

and loan associations, the mortgage companies, trust com

panies, banks and other financial people have followed that

same policy in Birmingham and elsewhere for many years.

(R. P. 122).

The court declined to admit the evidence. Mr. Camp

was then asked this question:

Q. Mr. Camp, in your opinion, I wish you would

tell the court what effect the invasion of a white resi

dential zone by negro citizens has on the appraised value

and fair market value of property in Birmingham?”

The plaintiffs objection was sustained and the defend

ants offered to show that it varies, causing depreciation

from 25 to 50 percent, according to locality. (R. p. 123) .

W. Cooper Green, President of the City Commission of

Birmingham testified (R. p. 124) that the Commission of

Birmingham is the governing body of the City and is com

posed of three members. He has special supervision over

the financial department, the parks and playgrounds, the

stadium and dog pound. There is a mixture of miscel

laneous departments. He testified that he had lived in

Birmingham forty-five years. He is familiar with the ter

ritory in the controversial area in the North Smith field

portion of Birmingham. He testified that he lived in the

Graymont-College Hills area from 1922 to 1936. He re

members a controversy arising between the white and

colored people in 1922 or 1923 about whether Center

Street would be the dividing line between the white and

colored settlements out there. He attended the meeting.

There was a committee representing the Graymont Civic

Association, a colored committee representing the negro

citizens. These committees met with the City Commission,

17

worked out a compromise and agreed on Center Street as

the dividing line, except one little strip down at the 8th

Avenue end of Center Street which was zoned colored later

by the zoning board in 1926. The territory west of Center

Street was to be white and the territory east of Center Street

was to be colored. (R. p. 125) .

That settlement has been observed and abided by gen

erally from that time until this controversy arose.

President Green identified a document which was pre

pared under his supervision giving certain facts and figures

about the City of Birmingham in 1946. It was in the

nature of a report to the people of Birmingham of the con

dition of affairs at that time. The document contains

statements about population, owner occupied property,

finance, schools, salaries, public health, libraries, municipal

auditorium, parks and playgrounds, department of public

welfare, housing, police and fire department, streets and

highways, garbage collection, street lighting, showing the

amount expended for the various services and the percent

age of the revenue that was particularly expended for the

negro citizens in Birmingham. Exhibit 16.

The defendants claimed that the information was rel

evant to show the amount of money that is needed for the

services rendered and that the facts stated therein showed

that there was no discrimination against the negro race in

Birmingham. (R. p. 127) .

The plaintiff’s objection was sustained and the defend

ants then offered in evidence a document entitled “The

1948 Municipal Tax Dollar, Condensed Statistical and

Operational Data”, published and distributed to the citi

zens of Birmingham by the City Commission. This was

defendants’ Exhibit No. 17. The court sustained the plain

tiff’s objection to the introduction of the document in evi

dence.

18

Mr. Green testified that when the Graymont area was

basically zoned in 1926, the zoning lines followed the

lines of the agreement that the white and colored citizens

reached in respect to said area in 1923. Mr. Green testi

fied that after the whites and negroes reached the agree

ment in 1923, and the property was zoned in 1926 there

had been no challenge of the arrangement in any way,

shape, form or fashion in the ten years he had been on the

Commission until the recent controversy involving the in

vasion of the area West of Center Street by some negroes

arose.

Mr. Green testified that there had been no change in the

zoning west of Center Street since 1926, but that on the

north end about thirty acres was rezoned from white to

colored and that the area rezoned was about ninety-five

percent vacant.

President Green was asked this question:

“Q. I will ask you to tell his Honor what in your

opinion would be the result of upsetting the custom that

was translated into the zoning laws by the ordinance, zoning

ordinance in 1926, with respect to white and colored areas

in the Graymont section?”

Plaintiff’s objection was sustained and Mr. Green was

then asked this question:

“Q. Mr. Green, I will ask you whether or not in your

opinion there is a clear and present grave danger of jeopardy

to life and property if the white section out there that we

have been talking about is invaded by negroes?”

The plaintiffs objected and the witness answered.

“Yes, sir.”

The court sustained the objection. The defendants

offered to show by this witness that in his opinion grave

disorder and damage to property and jeopardy to life and

limb would result from that situation. (R. p. 155).

The witness testified that the City of Birmingham was

up to its tax limit. After he had so testified the court sus-

19

tained an objection whereupon the defendants offered to

show that Birmingham is up to its tax limit and that it has

no new sources of revenue that it could tap under the law,

and if there is any substantial diminution in the ad valorem

tax from residential property sources, the city’s ability to

furnish necessary municipal services would be materially

impaired. (R. p. 156) .

The witness testified that the zoning ordinance was being

enforced to the best of his ability and that for the good of

racial harmony, law and order the Commission upholds the

ordinance and observes the principle that a negro can own

land in one area that is zoned for white occupancy, but

he is not allowed to occupy the land.

Mr. Green testified:

“I believe this matter goes beyond the written law, in j

the interest of peace and harmony and good will and racial

happiness.” “I think this thing creates bloodshed. Under

the police powers to keep law and order, we have that au

thority. There are some things that law cannot cover, and j

I think this is one of them.” (R. p. 158) .

He testified that nothing except the zoning ordinance

and its enforcement that he knewT of prevents the plaintiffs

in this case in continuing to build their home on the land

they bought.

Mr. Green was asked this question:

“Q. Mr. Green, in your opinion does the City Com

mission of the City of Birmingham or the State of Alabama,

both of them combined, have enough police force to pre

vent race riots, violence and damage to property if the in

vasion of white sections by negroes becomes general in Bir

mingham?”

The plaintiff’s objection was sustained.

Mr. A. Key Foster testified (R. p. 162) that he was Vice-

President of the First National Bank of Birmingham and

had about twenty-five years experience in the banking busi

ness which included the appraisal of mortgage loans on resi-

20

dential property in Birmingham. He testified that there

has been observed in Birmingham a custom in substance

that the white people remained in the white residential

areas as zoned by the City and the negroes did the same

thing with respect to areas zoned for negroes.

“Q. Was that fact taken into consideration in making

mortgage loans and appraising property?”

Plaintiff’s objection was sustained and defendants offered

to show that that was a very important question in the

making of loans and the appraising of property and fixing

values on it.

Mr. Foster testified that in the appraisal of property by

financial institutions such as banks, insurance companies,

mortgage loan companies, building and loan associations,

and institutions of that kind, the location of the property

and its stability of its classification is a very important

factor. (R. p. 164) .

It was then asked:

"Q. I will ask you, Mr. Foster, if property is in the

path of a contemplated change from white to colored classi

fication, or from colored to white classification, if that is a

factor that is taken into consideration in the appraisal of

property?”

Plaintiff’s objection was sustained.

The court ruled that the elements that enter into the

appraisal of property for the purpose of making mortgage

loans was immaterial in the issuance of the case. (R.

p. 164) .

The defendants offered to show all of the elements that

enter into a property appraisal of property by a man ex

perienced in that line of business for the purpose of show

ing just how they do arrive at values. That the location

and stability of classification is highly important. That

there are other such things, such as the type of tenant who

is going to occupy it, the type of occupant, whether white

21

or colored, whether professional or an artist, a laborer or

merchant, or what not. (R. p. 165) .

Mr. Foster testified that he was a member of the com

mittee of five appointed in 1949 by Commissioner Morgan

to work out a solution of the controversy that arose be

tween the negroes and whites over the Center Street zoning

in the Graymont territory. That committee conferred

with the negro committee several times.

Mr. Foster stated that the whole contention was that

the colored people wanted some more room to build high

class residential homes and the committee recommended

that a line be drawn down the center of Center Street, that

the territory east of Center Street be zoned colored, and

west zoned white, and that the line be drawn east and west

down 11th Avenue, that south of the line be white and

north of the line over the hill, down the other side, wfhich

is largely vacant, be zoned colored.

Mr. Foster testified that the two committees discussed

the advisability of residential zoning as a social matter in

Birmingham and that his committee explained to the negro

committee that they felt for the sake of peace and harmony

that there ought to be a segregation of races, regardless of

whether there was any ordinance to that effect or not and

it was generally agreed by them that that was the desire-

able thing to do. The negro committee wanted to keep

their people on their side of the established line if the

white people would see that the white people stayed on

their side. There were two blocks between 11th Court and

11th Avenue which the committee recommended to be

made into a park so that there would be sort of a zone be

tween white and negroes. The matter was finally com

promised by drawing a line down 11th Court instead of

11th Avenue.

V. L. Adams testified (R. p. 171) that he was engaged

in the coal business in Birmingham and lived in the Gray

mont section for about twenty-six years on 9th Court. Mr.

22

Adams testified that he was a member of the Graymont

Civic Association in 1923 when a controversy came up

about Center Street being the dividing line between the

white and colored races and that it was agreed that Center

Street was to be the dividing line up to a certain point, and

then it went back to the right some 180 or 200 feet, and

then went diagonally across the hill there to about that

bridge over the Frisco Railroad which is shown at the top

of the map which is identified as defendants’ exhibit 1.

Mr. Adams testified that agreement was generally re

spected by both white and negroes in that territory until

three or four years ago when some negroes tried to break

the white zone set up out there. Air. Adams testified that

he knew the sentiment out in the Graymont section and he

was asked:

“Q. I will ask you if in your opinion and judgment,

if there is a clear and present grave danger to public peace

and order, and to property values out there if the white

section that is in force here is invaded by the negroes?”

Witness testified, “Very great.”

The court sustained the objection made after the wit

ness answered and the defendants offered to show that

there was such clear, present and grave danger to the public

peace and order and to property value.

Mr. Walter E. Henley testified (R. p. 178) that he was

born in Birmingham in 1877 and as a young man became

connected with banking. He later left banking and under

took the development and operation of some large coal

properties and in 1925 returned to active banking since

that time. He was President of the Birmingham Trust &

Savings Company which is now the Birmingham Trust

National Bank for twelve years and is now Chairman of its

Board of Directors and actively engaged in the banking

business. In his industrial experience he employed a great

many negro citizens and in his banking business he has had

a great many dealings with negroes, financing the construe-

23

tion and loans on their houses. Mr. Henley testified that

his bank makes loans on white and negro residential prop

erty, that he is familiar with residential property values in

Birmingham generally and has been familiar with those

values over a period of years. That the Trust Department

of his bank under his supervision and direction has made

large numbers of loans which were scattered all over the

City of Birmingham, that he is familiar with the district

known as the Graymont-College Hills section, North Smith-

field.

Mr. Henley was asked:

“Q. I will ask you whether or not, if the restrictions in

the zoning of Birmingham are removed from that territory

and from residential property in Birmingham in general

with respect to the areas that are classified white residential

and colored residential, and the difference between them

is blotted out or ignored or disregarded, whether or not as

a matter of fact property values in the residential areas

would decrease?”

Plaintiff’s objection was sustained, whereupon counsel

for the defense stated to the court:

“MR. WILKINSON: We reserve an exception. It may

be that we can save the time of calling a number of wit

nesses to the stand. I wanted to elaborate on that con

siderably, if your Honor please, and get them to explain

why the property values would decrease, and to explain to

the court that that is a fact. There is nothing speculative

about that, it is just as certain to take place as the sun rises

and sets, because there are certain well recognized stand

ards in the financial world, and I thought the court would

be entitled to that information for what it might be worth

in this case. (R. p. 180) .

THE COURT: Well, I want you to make a full offer

to show all the facts necessary. Under the decisions of the

Supreme Court of the United States I don’t think it is ad

missible in evidence, unless they change their rules.

24

MR. WILKINSON: Well, I beg to differ with the

court about that, but I am not going to stop to argue it at

this point. I will take that up in my argument. I want

to be sure that I get the full factual picture before the

court, or at least an effort to get it before the court.

THE COURT: I want you to have the full benefit of

that opportunity too, for purposes of appeal in the case.

Q. Mr. Henley, I will ask you whether or not you know

whether or not there is anything speculative about the

effect upon property values, residential values in Birming

ham if the provisions of the zoning law are no longer ap

plicable and enforceable—

MR. MARSHALL: Objection.

Q—with respect to white and colored areas?

MR. MARSHALL: Objection.

THE COURT: Read me that question, Mr. Reporter.

(The question was read.)

THE COURT: I sustain the objection.

MR. WILKINSON: We reserve an exception. We

offer to show if your Honor please by this witness that the

effect upon residential property values in Birmingham, if

the provisions of the zoning law with respect to white and

colored areas is not enforceable is not a matter of specula

tion, but that this witness can and will testify as a matter

of fact that over a period of years this district, this City,

and particularly this Graymont-College Hills area, has been

built up, the residences have been built by white and

colored alike, and financed by his institution and by other

financial institutions in Birmingham, all of whom relied

upon the stability which it was believed that the zoning

laws afforded' that property, to colored and white alike.

And if those provisions are no longer enforceable, that the

protection it was believed that the property enjoyed, both

white and negro, is removed, the stabilizing effect is des

troyed, and that when that is recognized, that as a matter

of fact the property thus affected very materially depreciates

25

in value from 25 per cent on up, according to its location

and character. (R. p. 182) .

I don’t like to put a long string of questions if your

Honor understands just what I am trying to show.

THE COURT: That’s all right. I think I understand

it, and I want you to have that showing, but I don’t think

the evidence is admissible.”

The defendants offered to, but were not allowed to show

by Mr. Henley that out of the vast number of contacts that

he has had with members of the negro race that they have

been outspoken in their approval of residential segregation,

and outspoken in their recognition of its value to their race

as well as to the white race. Mr. Henley testified that a

great many houses had been built in the Graymont-College

Hills section both east and west of Center Street since 1926.

He was then asked this question:

“Q. Mr. Henley, I would like to ask you whether or

not in view of your long residence and experience in Birm

ingham you know of any better way for society in Birm

ingham to protect itself against the result of the feeling of

race hostility that has been manifested here than by the

zoning laws of the City which we claim were in force and

effect?” (R. p. 184) .

The plaintiff’s objection was sustained and defendants

offered to show the witness did not know of any better

method.

Defendants offered in evidence (R. p. 185) a portion of

the transcript of the proceedings of a negro mass meeting

in Birmingham on August 17, 1949 in which the nature

and extent of the violence in the Smithfield area was des

cribed and in which the speaker said:

“We will not cease calling on you until the flag of victory

shall not only wave over the battle field of Center Street,

but the flag of victory will be waving all over Birmingham.”

The plaintiff’s objection was sustained.

26

Mr. H. B. Hanson, Jr., testified (R. p. 188) that he is

the immediate past President of the Graymont Civic Asso

ciation, was President from July, 1947 to July, 1949. He

moved into that community after returning from the war

in 1946. He had no knowledge of any agitation going on

in reference to negro citizens crossing to Center Street at

the time he moved out there. That agitation came to his

knowledge after he purchased his home in that area. Mr.

Hanson testified that he made a careful study of each block

to see what the situation was, trying to be completely fair.

That the negro population is fairly dense up to Second

Street and then thins out in the last two blocks. There are

quite a few vacant lots east of Center Street on top of the

hill, going along Center Street.

Mr. Hanson testified that he commanded five thousand

negroes during the war and that the ill will between the

races in that area had reached a point that when he woke

up in the night and heard a noise, he feared that it was a

bombing or something was happening. It was getting

desperate, so he went to work to get a fair solution of the

problem. He testified that he worked to get the thirty-five

acres zoned for residential purposes and that north of 11th

Court and West of Center Street the area is ninety-eight

percent vacant. (R. p. 192) .

The witness testified that he located in that area because

it was close to Birmingham-Southern College and he wanted

to send his children to that Methodist College.

Commissioner Eugene Connor, the Commissioner of

Public Safety in Birmingham testified (R. p. 203) he was

a member of the legislature of Alabama for three sessions,

a railroad man, farmer, traveling salesman before he be

came Commissioner of Public Safety.

Commissioner Connor testified that the zoning laws had

been generally and universally observed by both races so

far as the residential areas are concerned during the twelve

years he has been a member of the City Commission until

27

this controversy arose. He was not allowed to testify that

during the time he had been on the Commission the zoning

law has as a matter of fact protected the citizens, both white

and colored. He was then asked this question:

“Q. I will ask you as an experienced legislator and as

an experienced member of the City Commission, whether

or not you know of any better way of the City of Birming

ham protecting its citizens against the consequences arising

from the feeling of race hostility than the present zoning

ordinance of the City of Birmingham?”

The plaintiff’s objection was sustained and the defend

ants offered to show that the zoning law does represent the

best judgment.

Mr. Connor testified that practically seventy-five per

cent of the houses in the territory west of Center Street have

been built since 1926 when the city was zoned and that

about seventy-five percent of the negro houses east of Cen

ter Street had been built since the city was zoned.

Mr. Connor testified that Birmingham does not have an

adequate police department and has not had an adequate

police department since he has been Police Commissioner.

All available money has been used to provide an adequate

police department. He asked for fifty additional police

last September, was turned down for the reason that the

city did not have the money. (R. p. 209) .

Chief of Police Floyd Eddins testified (R. p. 210) that

he has been with the Police Department of the City of Bir

mingham since November, 1919. He has served as patrol

man, sergeant, captain, assistant chief and chief and has

been chief for seven years. There was introduced in evi

dence a statement prepared by Chief Eddins showing the

number of policemen by square miles patrolled and the

yearly budget of cities in the Birmingham class. Accord

ing to this statement, Atlanta, Georgia has 464 policemen

to patrol 34 miles of territory with a yearly budget of

$1,823,125.12. Birmingham has 333 policemen to patrol

28

52 square miles of territory with a yearly budget of $1,179-

960.00. Indianapolis, Indiana, has 653 policemen to patrol

55 square miles of territory with a yearly budget of $2,524,-

468.81.

This table showed that because of lack of money Birm

ingham is handicapped in the matter of police protection.

Chief Eddins testified that racial tension has been high

in Birmingham particularly in that part of Birmingham

known as the Graymont-College Hills area. He was not

allowed to testify about the number of bombings and other

disorders in that area that have occurred since the contro

versy arose, but which the defendants offered to show. The

court ruled that they were not material.

Chief Eddins testified that up until 1947 the zoning law

adopted in 1926, together with such ordinances as have

been adopted from time to time since that time have been

generally and universally observed by the white and colored

population in Birmingham. (R. p. 215) .

Commissioner Connor was recalled as a witness and testi

fied that Mary Means Monk never took any appeal from

the action of Mr. Hagood, the administrative officer, to

the Zoning Board or to the City Commission. (R. p. 217) .

The defendants undertook to show that in a mandamus

proceeding which Mary Means Monk filed against the

building inspector, that when the point was raised that she

had not taken an appeal from Mr. Hagood’s refusal to issue

the building permit that she dismissed the petition. The

court stated that has already shown in this case and sustained

plaintiff’s objection. Defendants offered to show those

facts.

Commissioner Morgan was recalled as a witness and

under question by the court stated that it is the policy of

the City Commission to enforce Sections 1604 and 1605 of

the City Code and Ordinance 709-F. (R. p. 244) .

The District Court ruled that the defendants’ conten

tions “both factual and doctrinal” were not material “to

29

the issue of the constitutionality of such ordinances” and

on authority of Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S., 60, ad

judged the aforesaid provisions in the zoning ordinances

unconstitutional as in violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment and ordered an injunction against, their further en

forcement. The defendants in the court below appealed

from that final judgment. (R. p. 246).

PROPOSITIONS OF LAW

I.

The Fourteenth Amendment embraces two concepts of

liberty absolute and non-absolute rights.

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, 60 Sup. Ct. 900;

84 L. Ed. 1213.

II.

The right to occupy a particular piece of real estate for

a particular purpose is not an absolute right.

Reinman v. Little Rock, 237 U. S. 171; 35 Sup. Ct. 511;

59 L. Ed. 900.

Hadacheck v. Sebastian, 239 U. S. 394; 36 Sup. Ct. 143;

60 L. Ed, 348.

Pierce Oil Co. v. Hope, 248 U. S. 498; 39 Sup. Ct. 172;

/ 63 L. Ed. 381.

*7 Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U. S. 365; 47 Sup. Ct.

114; 71 L. Ed. 303.

Munn v. Illinois, 94 U. S. 113; 24 L. Ed. 77.

III.

Exceptional circumstances will justify discrimination on

the basis of the racial descent of a citizen.

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633; 68 Sup. Ct. 269;

92 L. Ed. 249.

30

Hirabayashi v. U. S., 320 U. S. 81; Sup. Ct. 1375;

87 L. Ed. 1774.

Korematsu v. U. S., 323 U. S. 214; 65 Sup. Ct. 193; 89

L. Ed. 194.

IV.

Reasonable restraints upon the use to which property

may be devoted are not unconstitutional.

Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., Supra.

Muller v. Oregon, 208 U. S. 412; 28 Sup. Ct. 324; 52 L.

Ed. 551.

Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U. S. 11; 25 Sup. Ct. 358;

49 L. Ed. 643.

Buck v. Bell, 274 U. S. 200; 47 Sup. Ct. 584; 71 L. Ed.

1000.

West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, 300 U. S. 379; 57 Sup.

Ct. 578; 81 L. Ed. 703.

State ex rel Carter v. Harper, 182 Wis. 148; 196 NW 451;

33 ALR 269.

Norton v. Randolph, 176 Ala. 381; 58 So. 283; 40 LRA

(NS) 129—Am. Cas. 1915 A 714.

V.

A state may prohibit intermarriage between whites and

negroes.

Alabama Constitution (1901), Section 102.

Plessy v. Furguson, 163 U. S. 537.

Pace v. State, 69 Ala. 231; 44 A Rep. 513; Affd 106 U. S.

583.

Story v. State, 178 Ala. 98; 59 So. 481.

VI.

A state may require separation of the races in schools.

Alabama Constitution (1901), Section 256.

Plessy v. Furguson, Supra.

31

State v. Board of School Commissioners, 226 Ala. 62;

145 So. 575.

VII.

A state may require the separation of the races on intra

state carriers.

Henderson v. U. S.;J30 Fed. Supp. 32.

Plessy v. Furguson, Supra.

West Chester Co. v. Miles, 55 Pa. St. 209

VIII.

The state may separate the races in parks, playgrounds,

swimming pools and golf courses.

Boyer v. Garrett, (MMS) U. S. District Court, Mary

land, Dec. 30, 1949.

IX.

The privileges and immunities protected by the Four

teenth Amendment are only those privileges and immuni

ties which owe their existence to the federal government.

Prudential Insurance Co. v. Cheek, 259 U. S. 530; 42

Sup. Ct. 516; 66 L. Ed. 1044.

X.

The enforcement of a statute over a long period of years,

without its constitutionality being challenged may be con

sidered a virtual recognition of its constitutionality.

Worthington v. District Court, 37 Nev. 212; 442 Pac.

230; Am. Cus. 1916 E 1097.

Elmore County v. Tallapoosa County, 221 Ala. 182; 128

So. 158.

Kyle v. Abernathy, 46 Colo. 214; 102 P. 158.

32

XI.

A policy of racial exclusion may be essential to the safety

of invested funds.

Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Corp., 87 NE (2d) 241.

XII.

Supporting facts essential to a decision of constitutional

questions of novel and far reaching importance should be

definitely found by the lower court upon adequate evi

dence.

Ne'ctow v. City of Cambridge, 277 U. S. 183; 72 L. Ed.

842; 48 Sup. Ct. 447.

Bordens Co. v. Baldwin, 293 U. S. 194; 55 Sup. Ct. 187;

79 L. Ed. 281.

U. S. v. Caroline Products Co., 304 U. S. 144; 58 Sup.

Ct. 778; 82 L. Ed. 1234.

Gompers v. U. S., 233 U. S. 604; 34 Sup. Ct. 693; 58 L.

Ed. 115.

XIII.

Segregation per se is not prohibited by the Constitution

of the United States.

Camming v. Richmond County Board of Education, 175

U. S. 528; 20 Sup. Ct. 197; 44 L. Ed. 262.

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78; 48 Sup. Ct. 91; 72 L.

Ed. 172.

Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337; 59 Sup. Ct. 232; 83 L.

Ed. 208.

People v. School Board, 161 N. Y. 598; 56 NE 81.

State v. Board of Trustees, 126 Ohio St. 290; 185 NE

196.

XIV.

A restriction on one form of liberty may be justified on

33

the very ground that it removes an impediment to another

liberty.

Holden v. Hardy, 169 U. S. 366; 18 Sup. Ct. 383; 42 L.

Ed. 780.

Texas & N. O. RR v. Brotherhood R & S Clerks, 281

U. S. 548; 50 Sup. Ct. 427; 74 L. Ed. 1034.

West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, 300 U. S. 379; 57 Sup.

Ct. 578; 81 L. Ed. 703.

Miller v. Schoene, 276 U. S. 272; 48 Sup. Ct. 246; 72

L. Ed. 568.

XV.

Zoning regulations may result to some extent in the

taking of property and yet not be deemed confiscatory or

unreasonable.

State v. Hillman, 110 Conn. 92; 157 Atl. 294.

Taylor v. Hackensack, 137 NJL 139; 58 A (2d) 788;

Affd 62 A (2d) 686.

Cassee Realty Co. v. Omaha, 144 Neb. 753; 14 NW (2d)

600.

Cantwell v. Connecticut, Supra.

Nectoic v. City of Cambridge, Supra.

XVI.

The police power may be put forth in aid of what is

sanctioned by usage or held by the prevailing morality or

strong and preponderant opinion to be greatly and imme

diately necessary to the public welfare.

Noble State Bank v. Haskell, 219 U. S. 104; 55 L. Ed.

112; 31 Sup. Ct. 186.

S4

FIRST ASSIGNMENT OF ERROR

The court erred in sustaining the plaintiffs’ objection to

the following question propounded to Commissioner Mor

gan:

“Q. In your opinion, I wish you would tell the court

whether or not the zoning ordinance as drafted, approved

and enforced and applied and construed and adminis

tered has been conducive to public peace and order.”

(R. p. 94) .

SECOND ASSIGNMENT OF ERROR

The court erred in refusing to allow the appellants to

show that the zoning ordinances had been conducive to

public peace and order. (R. p. 94) .

THIRD ASSIGNMENT OF ERROR

The court erred in sustaining the plaintiffs’ objection to

the following question propounded to Commissioner Mor

gan:

“Q. Mr. Morgan, if the custom that has been ob

served here with respect to the residential sections, white

and colored, by both races since you have been on the

Commission is upset or overturned, what in your judg

ment will be the effect on property values, residential

property values in the City of Birmingham.” (R. p. 94) .

FOURTH ASSIGNMENT OF ERROR

The court erred in sustaining the plaintiffs’ objection to

the following question propounded to Commissioner Mor

gan:

“Q. I would be glad if you would state to the court

what in your judgment and opinion as a member of the

Commission of the City of Birmingham would be the

35

result on the City finances and its ability to render mu

nicipal services such as fire, police, health, street im

provements, education, and matters of that kind, if a

substantial decrease in municipal revenue is brought

about by a disregard of the custom that has prevailed

for 12 years with respect to the residential zoning?”

(R. p. 95).

FIFTH ASSIGNMENT OF ERROR

The court erred in refusing to allow the appellants to

show that it would impair the City’s ability to the extent

that it would probably not be able to render those essential

services to the extent required and necessary and essential

for the comfort and convenience of the citizens. (R. p. 96) .

SIXTH ASSIGNMENT OF ERROR

The court erred in refusing to allow the appellants to

show that in the immediate territory of plaintiff s lots six

bombings had occurred within the last few months as a

result of the attempt of the negroes to invade that territory.

(R. p. 98) .

SEVENTH ASSIGNMENT OF ERROR

The court erred in sustaining the plaintiffs objection to

the following question propounded to Mr. E. A. Camp, Jr.:

“Q. What is the policy of the Liberty National Life

Insurance Company with reference to making loans on

white and colored residential property?” (R. p. 121) .

EIGHTH ASSIGNMENT OF ERROR

The court erred in refusing to allow the appellants to

show that the policy of the Liberty National and other life

insurance companies is that they loan on white residential

property where it is zoned white and loan on colored resi

dential property where it is zoned colored and that they

36

do not loan on property that is in a mixed zone or in a

twilight zone or in the path of being changed from one

classification to the other and that stabilized conditions is

one of the main factors taken into consideration in making

loans on property. (R. p. 22).

NINTH ASSIGNMENT OF ERROR

The court erred in refusing to allow the appellants to

show that the; building and loan associations, the mortgage

companies, trust companies, banks and other financial

people have followed that same policy in Birmingham and

elsewhere for many years. (R. p. 22) .

TENTH ASSIGNMENT OF ERROR

The court erred in sustaining the plaintiff’s objection to

the following question propounded to Mr. E. A. Camp, Jr.:

“O. Mr. Camp, in your opinion, I wish you would

tell the court what effect the invasion of a white resi

dential zone by negro citizens has on the appraised value

and fair market value of property in Birmingham?”

(R. p. 123).

ELEVENTH ASSIGNMENT OF ERROR

The court erred in refusing to allow the appellants to

introduce in evidence Exhibit 16 which document gives

certain facts and figures about the City of Birmingham in

1946. (R. p. 127).

TWELFTH ASSIGNMENT OF ERROR

The court erred in sustaining the plaintiffs’ objection to

the introduction of Exhibit No. 17 entitled “The 1948

Municipal Tax Dollar, Condensed Statistical and Opera

tional Data.” (R. p. 139) .

37

THIRTEENTH ASSIGNMENT OF ERROR

The court erred in sustaining the plaintiffs’ objection to

the following question propounded to President Green:

“Q. I will ask you to tell his Honor what in your

opinion would be the result of upsetting the custom that

was translated into the zoning laws by the ordinance,

zoning ordinance in 1926, with respect to white and

colored areas in the Graymont section?” (R. p. 154) .

FOURTEENTH ASSIGNMENT OF ERROR