Barrows v. Jackson Respondent's Brief on Certiorari

Public Court Documents

April 27, 1953

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Barrows v. Jackson Respondent's Brief on Certiorari, 1953. 53847696-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/82ce7bd0-4a05-4f63-9507-e1b2728c2553/barrows-v-jackson-respondents-brief-on-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

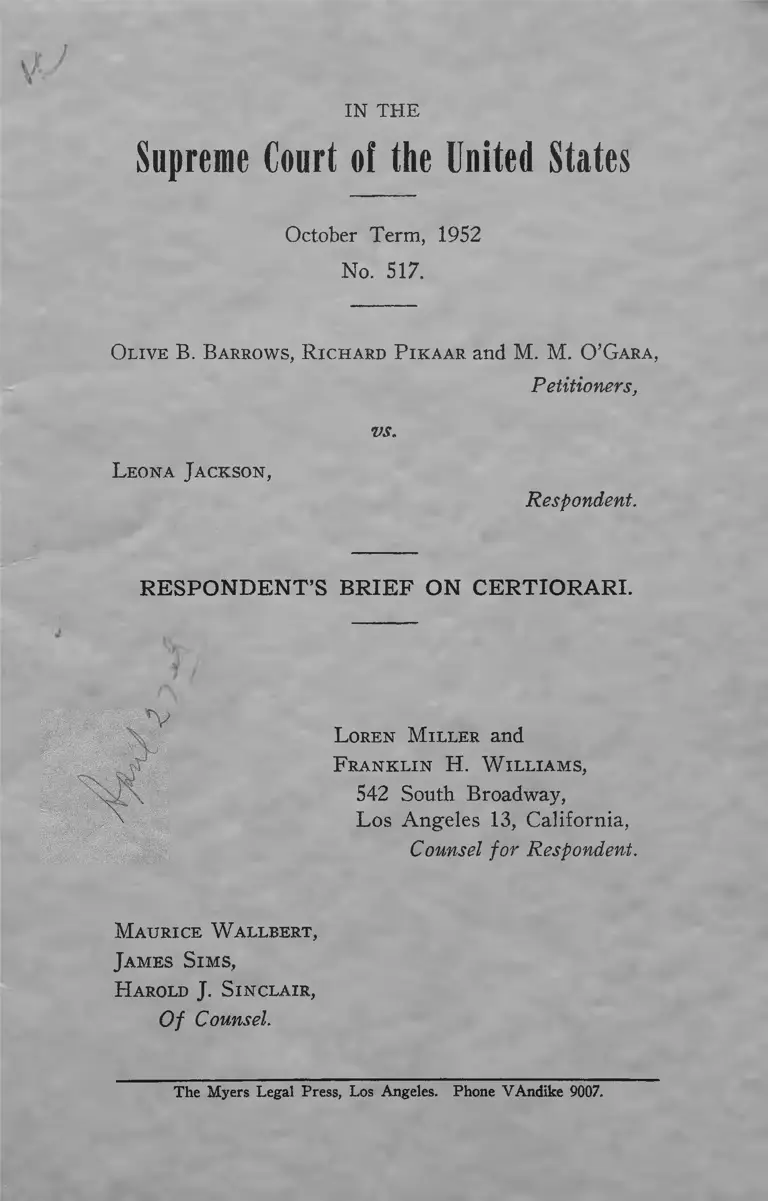

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1952

No. 517.

Olive B. Barrows, R ichard P ikaar and M. M. O’Gara,

Petitioners,

Leona J ackson,

vs.

Respondent.

RESPONDENT’S BRIEF ON CERTIORARI.

L oren M iller and

F ranklin H. W illiam s,

542 South Broadway,

Los Angeles 13, California,

Counsel for Respondent.

Maurice W allbert,

James S im s,

H arold J. S inclair,

Of Counsel.

The Myers Legal Press, Los Angeles. Phone VAndike 9007.

SUBJECT INDEX

PAGE

Question presented ........................................................................... 1

Statement of the case.......................................... 1

Argument.......................... 3

Conclusion ......................................................................................... 10

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

Cases page

American Federation of Labor v. Swing, 312 U, S. 321............... 4

Barrows v. Jackson, 112 A. C. A. 613............................... .......... 5, 9

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60............................................5, 6

Burke v. Maze, 10 Cal. App. 206.................................................... 2

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3.................................................... 3, 4

Cummings v. Hokr, 31 Cal. 2d 844................................................. . 9

Los Angeles Investment Co. v. Gary, 181 Cal. 680....................... 2

Martin v. Holm, 197 Cal. 733.... ................................................... 8

People v. Davis, 147 Cal. 346.......................................................... 2

Shelley v. Kramer, 334 U. S. 1...........................2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10

Vesper v. Forest Lawn, 20 Cal. App. 2d 157.............................. 8

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 339...................................................... 3

Wayt v. Patee, 205 Cal. 46.... ................... ....................................2, 8

Werner v. Graham, 181 Cal. 874.................................................... g

Wing v. Forest Lawn, 15 Cal. 2d 472.......................... ................. 8

Young v. Cramer, 38 Cal. App. 2d 64............................................ 8

S tatutes

California Civil Code, Sec. 1213...................................................... 2

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment..................... 3

T extbooks

Restatement of Law of Contracts, Sec. 1...................................... 7

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1952

No. 517.

Olive B. Barrows, R ichard P ikaar and M. M. O’Gara,

Petitioners,

Leona Jackson,

vs.

Respondent.

RESPONDENT’S BRIEF ON CERTIORARI.

Question Presented.

Although the issue is somewhat obscured by Petition

er’s arguments on collateral matters the question presented

here is whether or not judicial cognizance of a damage

action against the signer of a race restrictive covenant,

whose sale of race restricted real property eventuates in

its occupancy by a Negro, is permissible state action.

Statement of the Case.

Respondent owner of a lot signed a race restrictive

covenant in 1944 proscribing Negro occupancy. On

February 2, 1950, she conveyed the lot to predecessors in

title of Negro occupants. On September 3, 1950, she va

cated the premises and the next day Negroes began oc

cupancy. It is alleged that she vacated in order to “per

mit persons known to her to be other than the Caucasian

— 2 —-

race” to move into the premises. She failed to include

the proscriptive clause in her deed of February 2, 1950,

as she had covenanted to do.1 Because California has long

held that covenants against the sale of land to persons

of particular racial groups contravene its statutory and

public policy against restraints on alienation,2 Petitioners

predicated their suit on the theory that the occurrence of

non-conforming occupancy, per se, gave rise to a cause of

action for damages against Respondent and in favor of

Petitioners who were signers of the agreement.

Basing its decision on Shelley v. Kramer, 334 U. S. 1,

the trial court sustained a demurrer without leave to

amend as against all Petitioners and ordered judgment

for Respondent. Also relying on Shelley, the California

District Court of Appeal affirmed the judgment of the

trial court. The California Supreme Court denied a pe

tition to hear the case after decision by the District

Court of Appeal.3

Petitioners are here on petition for certiorari.

1The covenant was recorded and in California recordation of

such an instrument imparts notice of its terms to subsequent pur

chasers. (California Civ. Code, Sec. 1213; Wayt v. Pa-tee, 205

Cal. 46.) (Recitals in the deed are superfluous.)

Covenants against sales have been held void. This rule was

established in Los Angeles Investment Co. v. Gary (1919), 181

Cal. 680, and was followed without variance until the decision in

Shelley v. Kramer, 334 U. S. 1, with California courts upholding

covenants against use and occupancy and refusing enforcement of

agreements against sale.

3Under California procedure the refusal of its Supreme Court

to hear a cause after decision by its District Court of Appeal indi

cates approval of the result reached but does not necessarily indi

cate concurrence in the grounds of the decision. (People v. Davis,

147 Cal. 346; Burke v. Maze, 10 Cal. App. 206.)

— 3 —

Argument.

Petitioners’ assignment of errors is bottomed on the

proposition that Shelley held that race restrictive cove

nants are “valid,”4 and, they argue, that since such agree'

ments are “valid” the State must afford a remedy in dam

ages where non-Caucasian occupancy ensues as a result of

a signer’s sale of a restricted parcel. This unsophisticated

concept slurs over the basic issue of whether State par

ticipation in the discriminatory scheme of the covenantors

is forbidden by the command of the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

Plainly enough, Petitioners attempted to invoke state

participation when they filed suit asking the state courts

to assess and levy damages against Respondent. Judicial

action is, of course, State action.

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 339, 347;

Shelley v. Kramer, 334 U. S. 1.

The precise impact of the Fourteenth Amendment lay

in the fact that it “makes void 'State action of every kind’

which is inconsistent with the guarantees therein contained

and extends to manifestation of ‘State authority in the

shape of laws, customs, judicial or executive procedings.’ ”

Shelley v. Kramer■, supra.

As this Court pointed out in Shelley, the landmark

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, establish the proposition

4This Court did not hold such agreements “valid” in those words.

It did hold that “restrictive agreements standing alone cannot be

regarded as a violation of any rights guaranteed . . . by the

Fourteenth Amendment. So long as the purposes of these agree

ments are effectuated by voluntary adherence to their terms

there has been no action by the States.” (Shelley v. Kramer,

supra.)

4

that any and every kind of State action taken to assist

the individual in a racially discriminatory plan or scheme

runs afoul of the Amendment.5

We do not understand Petitioners to contend that a

State statute, city ordinance, or other enactment of a

State or one of its subdivisions assessing damages against

the signer of a race restrictive covenant, whose sale of

such property eventuates in Negro occupancy, would es

cape constitutional condemnation. However Petitioners

do contend that because the remedy they seek derives from

a substantive rule of law fashioned from the complex of

code provisions and decided cases their action is immune

to constitutional attack. But:

“It has been recognized that the action of state

courts in enforcing substantive common law rules

formulated by those courts may result in denial of

rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.”

Shelley v. Kramer, supra, p. 17.

A substantive rule of law, then, is no less, and no more,

subject to constitutional scrutiny than legislative enact

ments or executive action.

Cf.:

American Federation of Labor v. Swing, 312 U.

S. 321;

Shelley v. Kramer, supra.

BThis Court noted that the Civil Rights Cases contained no less

than eighteen phrases condemnatory of state participation—either

legislaive, executive, or judicial—in discriminatory action. It must

be kept in mind that the Civil Rights Cases do not hold that the

Amendment confers on the individual any right to discriminate.

They simply hold that so long as the individual engages in dis

criminatory conduct without the aid of the state his conduct is not

wrongful under the Amendment. The state may prohibit such

conduct; it may not assist it.

— 5—

The fact that participation of State courts is sought to

enforce the terms of a private agreement does not aid

Petitioners.

“Nor is the Amendment inffective simply because

the particular pattern of discrimination, which the

state has enforced, was defined initially by the terms

of a private agreement. State action, as that phrase

is understood for the purposes of the Fourteenth

Amendment, refers to exertions of State power in all

forms.”

Shelley v. Kramer, supra.

The California courts found as a fact that the purpose

of the covenant drawn in issue here was discriminatory.

The District Court of Appeal thus epitomizes this aspect

of the matter:

“Racial discrimination is inherent in the covenant;

its purpose and impact is to prevent the use or occu

pancy of real property by non-Caucasians, to segre

gate non-Caucasions ‘simply that and nothing more.’

The basic pattern of racial discrimination is much

the same in an action for damages as it is in a suit

in equity.” [R. p. 53.]

Barrows v. Jackson, 112 A. C. A. 613.

The question of whether or not the State may lend its

aid to residential segregation is not new to this Court.

That issue was decided thirty-five years ago in Buchanan

v. War ley, 245 U. S. 60.

The City of Louisville enacted an ordinance prescribing

racial residential segregation. Buchanan, a white man

agreed to sell a parcel of the interdicted property to War-

ley, a Negro. Warley breached his agreement and, when

sued, pleaded the ordinance by way of justification for his

breach. He prevailed in the State courts. On writ of

error to this Court, Buchanan attacked the constitution

ality of the ordinance insofar as it denied his right to sell

to a Negro. There, as is the case with Petitioners here,

the objection:

“is made that this writ of error should be dismissed

because the alleged denial of constitutional rights in

volves only the rights of colored persons and plain

tiff in error is a white person.”

Buchanan v. Warley, supra, p. 72.

This Court looked through form and saw that the ef

fect of sustaining Warley’s defense would be to prevent

the use and occupancy of real property by Negroes—

the same end envisaged here as epitomized by the Dis

trict Court of Appeal. There the command of the ordi

nance was absolute prohibition; here the attempt is made

to prevent Negro occupancy by the imposition of penalties

in the guise of damages on those whose sales result in

Negro occupancy.

In Buchanan this Court observed that:

“The right which the ordinance annulled was the

civil right of a white man to dispose of his property

if he saw fit to do so to a person of color.”

Buchanan v. Warley, supra, p. 81.

What Petitioners seek here is application of a substan

tive rule of law which, through imposition of damages,

will annul the civil right of a white person to dispose of

her property in such a manner that Negro occupancy may

ensue. Conceivably, fear of imposition of damages might

effectively prevent all sales where Negro occupancy might

ensue—the very end sought by Petitioners here, and in Bu

chanan. Nor can it be doubted

. . that among the civil rights intended to be

protected from discriminatory State action by the

Fourteenth Amendment are the rights to acquire,

enjoy, own and dispose of property.” (Italics ours.)

Shelley v. Kramer, supra, p. 10.

The short of the matter is that the State may not,

through judicial, executive or legislative action, annul the

civil right of any person to dispose of his property as he

sees fit, and that is true whether the attempted annulment

is by way of outright prohibition or through the imposi

tion of penalties in the guise of damages.

At this posture of the case Petitioners interject the con

tention that Respondent is bound by her “contract” and

that she “waived” her civil right to dispose of her prop

erty as she saw fit. Lawyers seeking to enforce agree

ments are fond of terming all writings to which their

clients are parties “contracts” because the very term “con

tract” implies an agreement enforceable in a court of law.6

6“A contract is a promise or set of promises for breach of which

the law gives a remedy or the performance of which the law in

some way recognizes as a duty.” (Restatement of the Law of

Contracts, Sec. 1.) Weighed in these scales and equated with the

holding in Shelley it cannot be said that race restrictive agree

ments are “contracts” in the ordinary sense of the term. Of

course, not every agreement is a “contract” in that sense. English

courts withheld enforcement of agreements in restraint of trade,

for example, although the agreements were “valid.” Agreements

not conforming to the Statute of Frauds are “valid” as are agree

ments against which the Statute of Limitations has run. Laches

may bar enforcement of a valid agreement.

The need for this semantic exercise is greater in this case

than in the ordinary action because here Petitioners hope,

by use of the term, to encase their claim for damages in

armor that will render it impervious to constitutional at

tack. What eludes Petitioners here is the legal conse

quences that flow from the signing of restrictive agree

ments, racial or building, under California law. Califor

nia has long and consistently held that such agreements

create . . equitable easements or servitudes for the

benefit of the lots of co-owners.”

Young v. Cramer, 38 Cal. App. 2d 64, 69.

This doctrine of equitable servitudes has been affirmed

and reaffirmed in a long line of cases, involving both

building and racial restrictions.

Werner v. Graham, 181 Cal. 874;

Martin v. Holm, 197 Cal. 733;

Vesper v. Forest Lawn, 20 Cal. App. 2d 157;

Wing v. Forest Lawn, 15 Cal. 2d 472;

Wayt v, Patee, 205 Cal. 46.

Once the servitude was created the California courts,

applying substantive rules of law, charged the conscience

of the violator with observance of the servitude and either

enjoined further violation or held him answerable in dam

ages. Either remedy was available at the option of the

complainant.

After Shelley the California courts declined to lend

further aid in enforcement of race restrictive covenants,

holding correctly that the full impact of this Court’s de-

-9-

cision fell on the substantive rule of law under which they

had previously charged the conscience of the violator

with observance of the terms of the agreement. ( Cum

mings v. Hokr, 31 Cal. 2d 844.) In this case the variant

is that aid of the California courts was sought through

a levy of damages rather than through injunctive relief.

Again they declined, correctly, to apply the substantive

rule of law to effectuate the discriminatory purpose of the

covenantors. The District Court of Appeal phrased its

declination in these words:

“The Fourteenth Amendment does not proscribe

individual action; but when, as here, the aid of a

court is sought to compel one of the parties to the

restrictive covenant to abide by its terms by sub

jecting him to an action for damages because of the

use or occupancy of the property by non-Cauca

sians—it is no longer a matter of individual action:

it is one of State participation in the maintenance

of racial residential segregation.” [R. p. 53.]

Barrows v. Jackson■, supra.

Petitioners are as free in California as they ever were

to enter into race restrictive agreements and to voluntarily

adhere to them. There is nothing in the decision of

which Petitioners complain that narrows that right in any

particular. The fact that they are free to observe the

terms of their agreement does not entitle them to demand

State action to accomplish their discriminatory purposes.

Parties cannot, by stipulation or agreement, confer on any

court jurisdiction to exceed its constitutional powers.

— - 10—

Conclusion,

It is true as Petitioners set forth that there is an even

division of the highest courts of the various states on the

question involved here. California and Michigan have

ruled adversely to Petitioners’ claim; Oklahoma and Mis

souri have upheld the right of their courts to entertain

damage actions of this kind. A trial court in the District

of Columbia dismissed such an action on the authority of

Shelley. Respondent agrees that the issue needs clarifi

cation but because the question presented has been so com

pletely disposed of by prior decisions we respectfully

urge that this Court grant certiorari and affirm the de

cision of the Court below without further briefs or

argument.

Loren M iller and

F ranklin H. W illiam s,

Counsel for Respondent.

Maurice W allbert,

James S im s,

H arold J. S inclair,

Of Counsel.

Service of the within and receipt of a copy

thereof is hereby admitted this.................day of

January, A. D. 1953.

1-.30-53—85