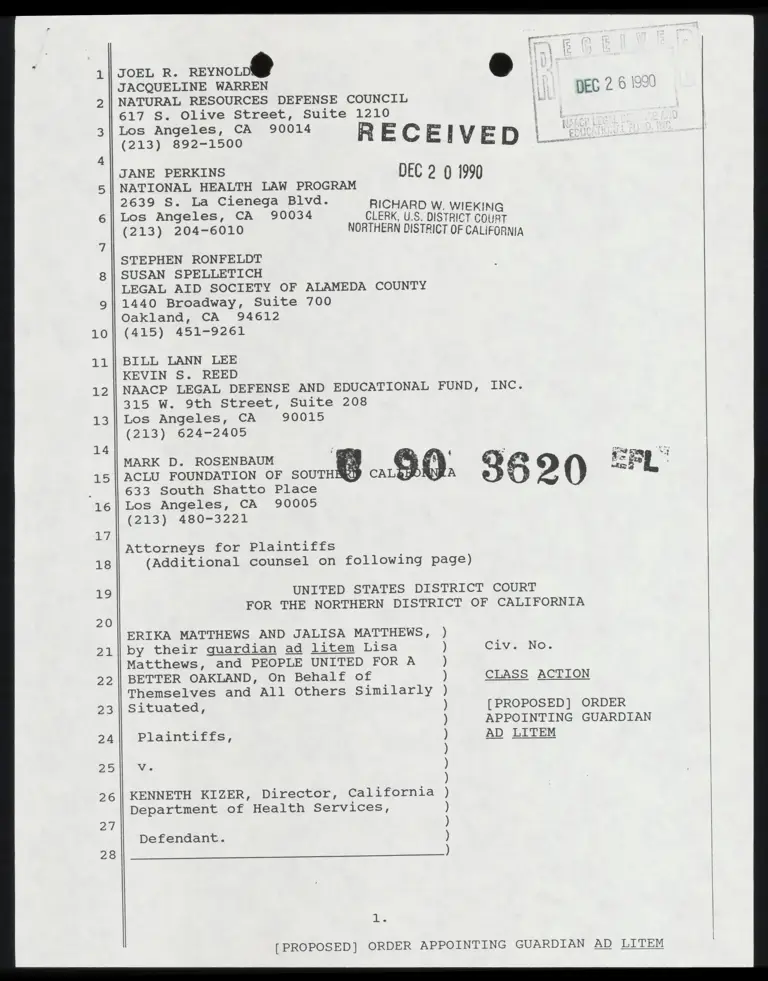

(Proposed) Order Appointing Guardian Ad Litem

Public Court Documents

December 20, 1990

3 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Matthews v. Kizer Hardbacks. (Proposed) Order Appointing Guardian Ad Litem, 1990. da69150f-5e40-f011-b4cb-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/82f7986e-4380-4d69-9f46-7a1d1aa0cac3/proposed-order-appointing-guardian-ad-litem. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

1 | JOEL R. sewvorl 1

JACQUELINE WARREN i DEC 2 6 1990

2 || NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL thik

617 S. Olive Street, Suite 1210

Los Angeles, CA 90014 Wi

3 (313) 892-1500 R E C E ! V E DPD us

JANE PERKINS DEC 2 0 1990

5 | NATIONAL HEALTH LAW PROGRAM

2639 S. La Cienega Blvd. RICHARD W. WI

6 | Los Angeles, CA 90034 CLERK, U.S. DISTRICT COST

(213) 204-6010 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

STEPHEN RONFELDT

8 || SUSAN SPELLETICH

LEGAL AID SOCIETY OF ALAMEDA COUNTY

9| 1440 Broadway, Suite 700

Oakland, CA 94612

10] (415) 451-9261

11 { BILL LANN LEE

KEVIN S. REED

12 | NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

315 W. 9th Street, Suite 208

13 || Los Angeles, CA 90015

(213) 624-2405

MARK D. ROSENBAUM : ) ‘ . a I

15 | ACLU FOUNDATION OF SOUTH CAL IN A 0 “ez §

633 South Shatto Place

16 Los Angeles, CA 90005

(213) 480-3221

37

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

18 (Additional counsel on following page)

19 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

20

ERIKA MATTHEWS AND JALISA MATTHEWS, )

21 | by their guardian ad litem Lisa ) Civ. No.

Matthews, and PEOPLE UNITED FOR A )

22 || BETTER OAKLAND, On Behalf of ) CLASS ACTION

Themselves and All Others Similarly )

23 || Situated, ) [PROPOSED] ORDER

) APPOINTING GUARDIAN

24 Plaintiffs, ) AD LITEM

)

25 Vie )

)

56 | KENNETH KIZER, Director, California )

Department of Health Services, )

27 )

Defendant. )

28 )

l. [ PROPOSED] ORDER APPOINTING GUARDIAN AD LITEM

EDWARD M. CHEN

ACLU FOUNDATION OF NORTHERN CALIFORNIA

1663 Mission Street, Suite 460

San Francisco, CA 94103

(415) 621-2493

2.

PROPOSED] ORDER APPOINTING GUARDIAN AD LITEM

Litem regularly came on for hearing before the Honorable

The vor 1 ds Lisa Matthews for svodliP seit of Guardian Ad

on January , 1991. Having considered the

arguments of counsel and the evidence presented, the Court finds

that:

1) Infant plaintiffs Jalisa and Erika Matthews do not have

the capacity to bring their own claims challenging the

denial of lead blood screening or treatment and lack any

other guardian or duly appointed representative;

2) The movant and mother of the infant plaintiffs, Lisa

Matthews, will competently represent plaintiffs’

interests in this action and does not have any interests

adverse to them.

NOW, THEREFORE, it is hereby ordered that Lisa Matthews is

appointed Guardian Ad Litem in this action for her two infant

children, plaintiffs Erika Matthews and Jalisa Matthews.

Dated: January +1991

U.S. District Court Judge

3.

[PROPOSED] ORDER APPOINTING GUARDIAN Al