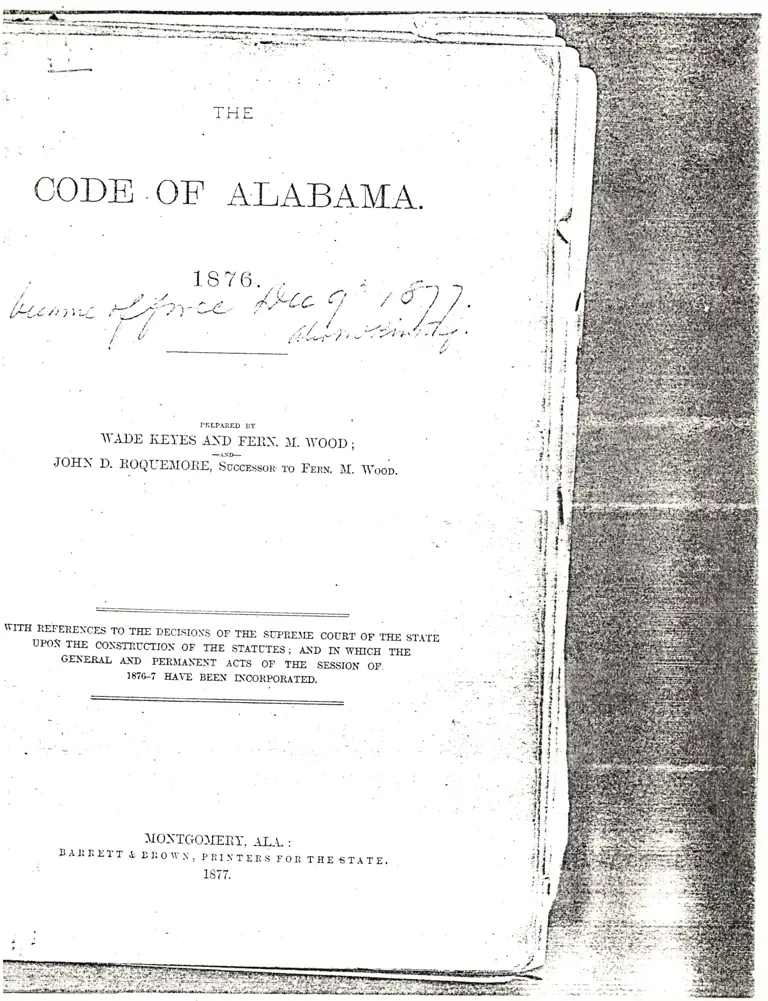

Excerpts from the Code of Alabama 1876

Working File

January 1, 1876 - January 1, 1876

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Excerpts from the Code of Alabama 1876, 1876. a09bb20b-ee92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/82f82690-17ad-4224-8d7e-bc787edc798e/excerpts-from-the-code-of-alabama-1876. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

THE

OODtr OF ALABAMA.

/lLLi t't i tt,'

.\l ADE IiETDS

PnEP-UiED tiY

A^\D FUt\. M. llIOOD;

_.\sr

JOHN D. ROQL'EIIOIiE, Succnsson.ro FrHx If. Tl.ooo.

I'ITII SEFENE._CES TO TEE DECISIOSS OF TE-F SUPNEUE COLIR,? OF TEX STI,.IDuPO]* THE CO\STnucfIo*- oF rEE STATUTES; AIiD IN \'EICE THEGE!iE.&{I AID PERIIAIT\T ACTS OF TITP SESSION OF.

1876-7 EA\T BEEN A'CORPOR,ATED.

tlo\Tc+olrEBr, -\-Ll' :

!AIlnDTT.l. UtlO\\-\, pnI.\-TEnS FOn TIIE €TATE.

1877.

.d

910 Pent 5.1 OITENSES AG.]JTS? SUTTBAGE. [Trra 1,

' $ l2si. Becon"irut inrmicaterr.tbttil uotiny flace on erection rJrn1._

{#;i*.,,*"r;,-t"irf

ffi{

j:.T,*j,,ffi r,;:il,;;,1.;':t?k*[:ii#fi 'ffi

. n 1286. Selting or gui,t ciu"g1-y,qr{, oi it "t;ii"y, anct ctanr p,.e-. erb.se.eg. cedinty._r1-\ny$ersoir *h"o sl_ral] 9,"fi or-gi;;;;;,d;;;i#;-

.the day on.rrlich any electionl,l"-Id; t"ff ;trl, or ou the dav'p*ececling, iu violaridn oI sectio;rsi; ffi a;.[i; -rdr"=;"";. ', rnisclemeanor, and, on .o""i"tio", ;;t b" il.il;d'fip.rili#r;the cliscretion of lhe

"o*t.

-

' $ 1287. False.noeanincl of o-ote, or-toitws.t whrn Tnrsons "ruAr*i. ,arb.src.s6. ilf any person whose i.oi" i.-gnud;ff;i,;;1fr vrtness sworruncler lhe provisions Li ."Jtio" zzs J?u.iJ ci.rll:tru knowinelv.rssrof cormpilv swear f"t.;iy, ["""-n"ri u'"' j*-a*."i;rTf?i

perj ury, ancl, on 6onviction theredf , ;h ril-il ; ; J.;"1" ;"" ffi ;"rI]onment in the penitentiary not less'tnrr- tr"r,t;#"."1" inH"i'"-"years. (1)

jrrarch6,1s75, S 12S8. .FuLse swearinrr rtt rrttnt.itiTril-electiryn._ilnyperson whop'eJe' shall filsely, rvillf-*lly an'cl corruptry't"n. *"y'irtn *quir.eci byraw ., at auy muilcipat.eldcti.on, is griiii 9i.p;;.b,;,1, ou convicrion,m*st be punishecl by imprslnment in the penitentiarv not lessthan o,el nor- more it

""

'tn.""-;;;;";i;;i#i""ll'"-ti.i, r"ilxri'iii

ilp.ll tr a! elecrion rrerd *.cler ;"v'i;* ;l;;"i";;"visiou is orh:er*ise macle rbr trre p*nishment oi p"4"ry;i;rh eiectio,s.

i3,t;'lrl'.tt"','^_i.1?S9,. Ilkpl uotiitl.-.i A"y.pers,, voring more ilran once atanv election hercl in trris state,'oi ,t"p..itiogLJJtn"" one bafloitbri the same offi"u, o""rri.- iotu at such erection. or knorvinorwatteppting.to-vote 'rvhen he is nor e,titt",r i;j;;"] J, ri.irir#i{any kiari c,f illegal or francl'lent *rr"g,l" ililli?i ;'f;"X;,;":l:on conviction thereof, shall be rmprrso,ec[ rn the p.;i;;;il;-;;.;

less than two, uor more than-a;=';;;;;;;t-tn"- al""i#;ili d"jury. /2)

S 4290. D trty oy' j tulqe lo thrt rrrc tt rctncl iur rt ;ity,t.irll ,,, rb s'c 39

:tl.riir t;*ir'fJt;,}Tf#}*iidiii,{3ruft':';lili,

juries, a.cr clirecr the'r toisnedui r*iri.;;;r:;li ulegal roting,*ntl also i'to any aucl -all iit"grl-L"[. ;;;i;;d bv rnspectors,. returllng g$ce*, or.other oEiiers nf electioo---"''!rb.cec.r0r. $ 49c1. Lbtirt,t tuilhuut rerlistt.otion

",,'i-ti,i.irri otr.trt.-r-\ny personvo.ting at.any countv or strite

"t".rio", iuir; hx;;;r"gisterecr aucltaken *,cl srib_scribed to ihe ."G;i;;tirr-;";i;, i" ;,ilji;l ,;;i":tlerue&rrt)r, ir,nd, on conviction, do"t t

"

n"",i"r.it^[s'. thrn one hua-checl, ,ormo.e thau one thousa",r ,inrh;;,1-r"iro"i.i.ooed iu theco*nty jrril, or se,tencecl to Lrarci r*b,.,. fn.-ihe-iiorrty, not lessthau.one, n-or mot'e than six months,

^t itr"-.ii."riti'on oi gre court.arb. s@.e2. $ +292. Bribit,rl or rilletnltlittq tu ;rr'rl,reriii-;;;;;;[;""";";;;;

by lrribery, or oA"r,ing to'l_n.ite, or' b.1. ;;r;-;;l"r'-cormpr uuans,aitemlts i" i,,nli",i""'.,L"

"i;;;;; i, g(i,;;'h['1:,itl, or creter trimfi'oru giving the san,o, oi tlisiurb

"r:

tfi",t"F rrir, i. i"n" free exercise,f the righi.t sutfrage,.irt;r,v electi,rri, Le,

-i;

g,,iTir-,rt ,"ilii+ru-r_rrciux)l', itrr(1, on.couvictiorr, ruust Le tirretl nr,[ ]f-* tt *,, oue trir,ir-rL'etl, uor nrore thrr,n one thousnrra ,i..,ir,ir", ,r".r'*"irt"r,cetl to h1r,clLrbor for the countv, or irnnrisorre,r i,, tlie'"n,irt" llii, for nob ]essthan trrirtv days, n6r mo.e rhiru "i, *o"trr",'ii'tir" discretion ot'the jur.v. "

t- N;;;""i,.ri"r, it p*t, l,;

hur.iog kn,rrvledgu.t his l;i11h. thst he',vas rrf *ge. -_j.l .{lr. :lr)rJ. Snfrieieucr of ;rlle-grt i.rr iu iutlictrnerr r. _- nr. \, r t.r ,u vie r inn if o.fii t.,iJi o li,,;;;,, ,";il;;;.i;;f .;;il;;oath not I deteuse, hut nrrv he ,rrgoil iu n,itig,rti,,n. __li, ifi' - '"'

. ,. i2 .Ua. 299. - ".

1.

'l.a