Cooper v. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Cooper v. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Brief for Petitioners, 1983. c5c26636-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8308e5f6-1d5a-48e6-a352-eef0a449e271/cooper-v-federal-reserve-bank-of-richmond-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

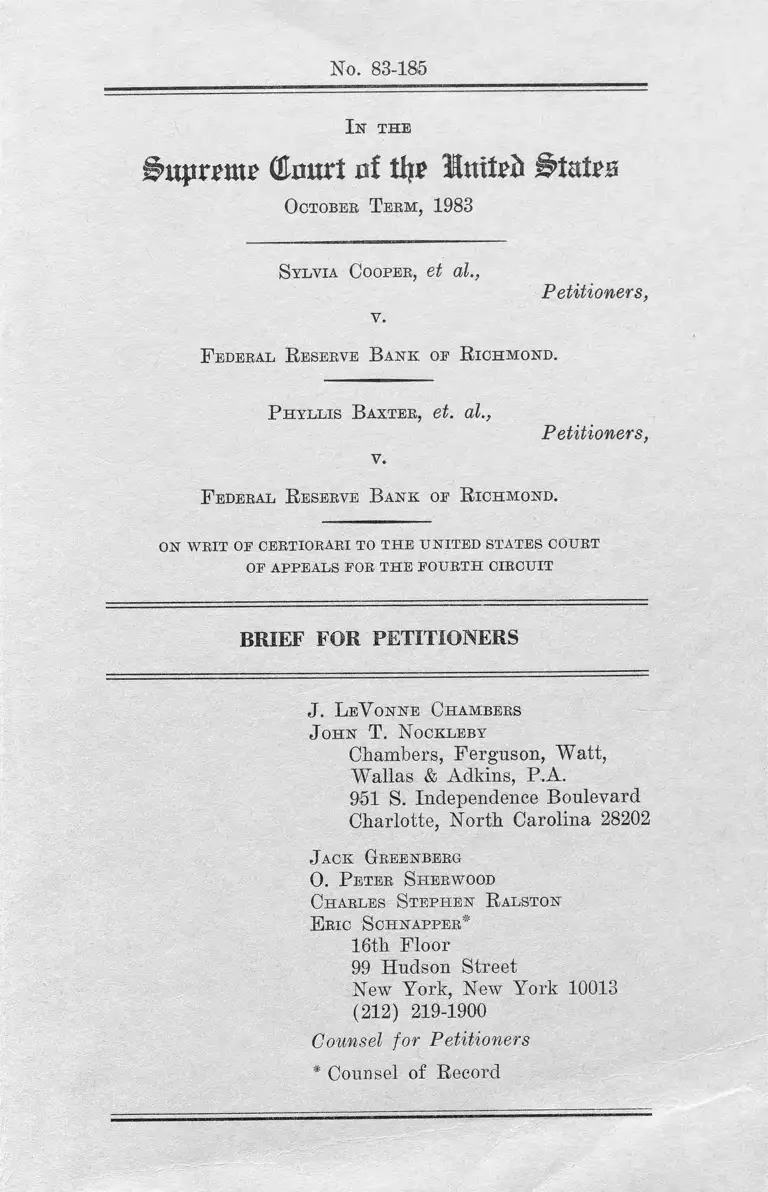

No. 83-185

In t h e

CSIourt of tijf States

October Teem, 1983

Sylvia Cooper, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

F ederal R eserve B ank oe R ichmond.

P hyllis B axter, et. al.,

v.

Petitioners,

F ederal R eserve B ank oe R ichmond.

ON W RIT OP CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT

OF APPEALS POE THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

J. LeV onne Chambers

J ohn T. Nockleby

Chambers, Ferguson, Watt,

Wallas & Adkins, P.A.

951 S. Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

J ack Greenberg

0 . P eter Sherwood

Charles Stephen R alston

E ric Schnapper*

16th Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel for Petitioners

* Counsel of Record

QUESTION PRESENTED*

Did t h e C o u r t o f A p p e a l s e r r in

h o l d i n g t h a t a p r i o r f i n d i n g t h a t any

p a t t e r n o r p r a c t i c e o f employment d i s c r i m

i n a t i o n was not " p e r v a s i v e " p r e c l u d e s , as a

matter o f res j u d i c a t a , a l l employees from

l i t i g a t i n g any i n d i v i d u a l c la ims o f d i s -

c r i m i n a t i o n ? *

*The p a r t i e s t o t h i s l i t i g a t i o n are s e t out

at p . i i o f the P e t i t i o n .

1 -

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Quest ion Presented ......................................... i

Table o f A u t h o r i t i e s .................................... i i

Opinions Below .................................................. 1

J u r i s d i c t i o n ....................................................... 2

Rule In vo lved ..................................................... 3

Statement o f the Case ................................... 4

Summary o f Argument ...................................... 15

ARGUMENT ................................................................ 21

I . The Binding E f f e c t o f

D e c i s i o n s in Class A c t i o n s . . 21

I I . The Baxter Claims Are Not

Barred by Res J u d i c a t a ............ 33

(1) The D i s t r i c t Court in

Cooper Did Not Decide

the Mer i ts o f the

Baxter Claims ...................... 33

(2) The D i s t r i c t Court in

Cooper Ex pr es s ly Reserved

the Right o f the Baxter

P l a i n t i f f s t o Bring

This L i t i g a t i o n ................. 56

I I I . The A p p l i c a t i o n o f C o l l a t e r a l

Estoppel To This Case ............... 63

C onc lu s i on ............................................................ 67

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

American Pipe C o n s t ru c t i o n Co. v. Utah,

414 U.S. 538 ( 1 974) ____ ______. . . 23

Bogard v. Cook, 586 F.2d 399 (5th

C i r . 1 978 ) ........................................ 30

Branham v . General E l e c t r i c C o . , 63

F.R.D. 667 (M.D. Tenn. 1974) . . . 46,48

Brown v. F e l s en , 442 U.S. 132

(1979) 35

Commissioner v. Sunnen, 333 U.S.

591 (1 948) .................................. . . . . . 64

C o nn ec t i cu t v. T e a l , 73 L. Ed 2d 130

(1 982) .......................................... 44

C o s t e l l o v. United S t a t e s , 365 U.S.

265 (1961) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34,35

Dickerson v. United S ta te s S t e e l

C o r p o r a t i o n , 582 F.2d 827

(3d C i r . 1978) ..................................... 45

Federated Department S t o r e s , In c . v.

M o i t i e , 452 U.S. 394 (1981) . . . . 34,49

Franks v . Bowman T ra n s p o r t a t i o n C o . ,

424 U.S 747 (1 976) ........................ 47 ,48 ,50

Furnco C o n s t ru c t i o n Corp. v .

Waters , 438 U.S. 567 (1978) _ 44

Cases: Page

- iii -

General Telephone Co. v . F a l c on , 457

U.S. 147 (1982) ............................... 27 ,3 3 ,4 3

Harr ison v. Lewis , 559 F. Supp. 943

(D.D.C. 1983) ......................................... 46

Hughes v. United S t a t e s , 71 U.S.

(4 Wal l . ) 232 ( 1 866 ) ........................ 35

I n t e r n a t i o n a l Brotherhood o f Team

s t e r s v. United S t a t e s , 431 U.S.

360 (1977) ........................ 5 , 1 6 , 3 2 , 4 3 , 4 7 , 5 0

Kreraer v. Chemical C o n s t r u c t i o n C o r p . ,

456 U.S. 461 (1 982) .................... 17,1 8 ,3 8 , 4 9

Marshal l v . K irk land , 602 F.2d 1281

( 8th C i r . 1979) .................................... 31

Montana v . United S t a t e s , 440 U.S.

147 (1979) ................................................ 63

Muskel ly v. Warner & Swassy C o . ,

653 F.2d 112 (4th C i r . 1981) . . . 46

R u s s e l l v . P l a c e , 94 U.S. 606

( 1 876) ......................................................... 64

Stastny v . Southern B e l l T e l . & T e l .

C o . , 628 F .2d 267 (4th C i r .

19 80 ) ..................................................... 46

Woodson v. Fu l to n , 614 F.2d 940

(4th C i r . 1 980) .................................... 30

St a tu te s

28 U.S.C. § 1254 ( 1 ) ...................................... 3

Cases; Page

IV

Cases: Page

28 U.S.C. § 1292(a) ....................................... 13

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ................. 11

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 ..................... 4

C i v i l R ights Act o f 1964, T i t l e

VII ......................... ............................... .. . 5 , 4 7 , 5 1

Rules

Rule 23, F . R . C . P .......................... 2 2 , 2 4 , 2 7 , 2 8 , 4 7 ,

50

Rule 2 3 ( a ) , F . R . C . P ...................... 26

Rule 2 3 ( b ) , F .R .C .P . . . . . . . . . . . . . ___ 26,32

Rule 2 3 ( c ) , F .R .C .P . ............... 3,23

Other A u t h o r i t i e s

Franke l , "Some P re l im ina ry Observa

t i o n s Concerning C i v i l Rule 23 " ,

43 F.R.D. 39 ( 1 967) ...................... 32

F. James, J r . & G. Hazard, C i v i l Pro

cedure (2d ed. 1977) ................. 25

3B Moore ’ s Federal P r a c t i c e

§ 2360 (2d ed. 1982) . . . . . . . . . . . 22

C. Wright & A. M i l l e r , Federal

P r a c t i c e and Procedure

(1 972) ................. 2 2 , 2 4 , 2 5 , 2 9 , 4 6

Restatement o f Judgments, 2d

(1982) ...................................................... 34,62

v

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1983

No. 83-185

SYLVIA COOPER, e t a l . ,

P e t i t i o n e r s ,

v.

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF RICHMOND,

PHYLLIS BAXTER, e t a l . ,

P e t i t i o n e r s ,

v.

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF RICHMOND.

On Writ Of C e r t i o r a r i

To The United S t a te s Court o f Appeals

For The Fourth C i r c u i t

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

OPINIONS BELOW

The d e c i s i o n o f the c o ur t o f appeal s

i s r e po r te d at 698 F.2d 633, and i s s e t out

a t p p . 1 a - l 8 5 a o f t h e A p p e n d i x t o t h e

2

P e t i t i o n f o r Writ o f C e r t i o r a r i ( h e r e i n

a f t e r c i t e d as " P . A . " ) . The o r d e r denying

r e h e a r i n g , which i s not ye t r e p o r t e d , is

s e t out at P.A. 186a. The d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s

Memorandum D e c i s i o n o f Oc tober 30, 1980, i s

n o t r e p o r t e d , and i s s e t o u t a t P . A .

191a-96a . The d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s F ind ings o f

Fact and Co nc lu s i ons o f Law, which are not

r e p o r t e d , are se t out at P.A. 197a-285a.

The d i s t r i c t c our t o r d e r s o f May 29, 1981,

and F e b r u a r y 26 , 1,9 8 2 , w h i c h a r e n o t

r e p o r t e d , are se t f o r t h at P.A. 286a-89a

and P.A. 290a-97a r e s p e c t i v e l y .

JURISDICTION

The judgment o f the Court o f Appeals

was entered on January 11, 1983. A t ime ly

P e t i t i o n f o r Rehearing was f i l e d , which was

d e n i e d on A p r i l 6 , 19 83 by an e q u a l l y

d i v i d e d c o u r t . (P.A. 186a) . This Court

granted an e x t e n s i o n o f time in which to

3

f i l e the P e t i t i o n f o r Writ o f C e r t i o r a r i

u n t i l August 4, 1983. The P e t i t i o n f o r a

Writ o f C e r t i o r a r i was f i l e d on August 4,

1 9 8 3 , and was g r a n t e d on O c t o b e r 3 1 ,

1 9 8 3 . J u r i s d i c t i o n o f t h i s C o u r t i s

invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1 2 5 4 ( 1 ) .

RULE INVOLVED

R u l e 2 3 ( c ) ( 3 ) , F e d e r a l R u l e s o f

C i v i l Procedure , p r o v i d e s :

(3) The judgment in an a c t i o n

maintained as a c l a s s a c t i o n under

s u b d i v i s i o n ( b ) ( 1 ) o r ( b ) ( 2 ) ,

w h e t h e r o r n o t f a v o r a b l e t o t h e

c l a s s , s h a l l i n c l u d e and d e s c r i b e

t h o s e whom t h e c o u r t f i n d s t o be

members o f the c l a s s . The judgment

in an a c t i o n maintained as a c l a s s

a c t i o n under s u b d i v i s i o n ( b ) ( 3 ) ,

w h e t h e r o r n o t f a v o r a b l e t o t h e

c l a s s , s h a l l in c l ud e and s p e c i f y or

d e s c r i b e t h o s e t o whom t h e n o t i c e

prov id ed in s u b d i v i s i o n ( c ) ( 2 ) was

d i r e c t e d , and who have not r eques ted

e x c l u s i o n , and whom the c o u r t f i n d s

t o be members o f the c l a s s .

4

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On Marcia 22 , 19 77 , t h e c;EuC b r o u g h t

s u i t ag a i n s t the Federal Reserve Bank o f

R i c h m o n d a l l e g i n g t h a t t h e Bank had

d i s c r i m i n a t e d aga ins t b la ck employees in

making promot ions at i t s C h a r l o t t e , North

C a r o l i n a f a c i l i t i e s , and t h a t i t had

d i s c r i m i n a t e d in p a r t i c u l a r ag a i n s t S y lv ia

C o o p e r b e c a u s e o f h e r r a c e , f i r s t by

r e f u s i n g t o promote her t o a s u p e r v i s o r y

p o s i t i o n and t h e n by d i s c h a r g i n g h e r .

J u r i s d i c t i o n was as s er te d under 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e—5. ( J .A . 6a—11a) . On September

21, 1977, Cooper and three o t h e r pr e s e nt or

former Bank employees ( the "Cooper p l a i n

t i f f s " ) were p e r m i t t e d t o i n t e r v e n e as

p l a i n t i f f s . ( J .A . 12 a -23a ) . On A p r i l 28,

1 9 7 8 , t h e d i s t r i c t c o u r t c e r t i f i e d a

p l a i n t i f f c l a s s c o n s i s t i n g o f b lacks who

had been employed at the Bank's C h a r l o t t e

branch s i n c e January 3, 1974, and had been

/

- 5 -

d i s c r i m i n a t e d a g a i n s t on the b a s i s o f

r a c e . ( J .A . 2 4 a - 3 2a ) .

The case was t r i e d wi thout a j u r y in

September, 1980. The case was heard under

the b i f u r c a t e d procedure common in T i t l e

VII c l a s s a c t i o n s , and e x p r e s s l y s an c t i o n e d

by t h i s Court in I n t e r n a t i o n a l Brotherhood

o f Teamsters v. United S t a t e s , 431 U.S. 360

( 1 9 7 7 ) . Under that procedure p l a i n t i f f s

were r eq u i re d t o e s t a b l i s h at the September

1980 hear ing that there had been a p r a c t i c e

o f c l a s s w i d e d i s c r i m i n a t i o n ; i f that burden

were met, the i d e n t i t i e s o f the p a r t i c u l a r

c l a s s members who were the v i c t i m s o f that

p r a c t i c e were t o be r e s o l v e d at a l a t e r

h e a r i n g .

At the September, 1980, t r i a l P h y l l i s

1/

Baxter and f o u r o t h e r b l ac k Bank employees

1 / Brenda G i l l i a m , Glenda Knott , A l f r e d

Harr ison and S he rr i McCorkle. Emma R uf f i n

a l s o s o u g h t t o t e s t i f y , b u t b e c a u s e

she was in grade 4 and thus cove red by the

6

( t h e " B a x t e r p l a i n t i f f s " ) , none o f whom

were named p l a i n t i f f s in the Cooper a c t i o n ,

sought t o t e s t i f y r egard ing a l l e g e d a c t s o f

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n aga in s t them by the Bank.

The de fe nd a nt , however, o b j e c t e d t o t h e i r

t e s t i m o n y , u r g i n g th e d i s t r i c t c o u r t t o

r u l e that i t would not r e s o l v e the mer i t s

o f those " i n d i v i d u a l c la ims and that t h i s

ev i d e nc e we hear j u s t goes to t h e i r c la im

that there i s a pa t t e r n and p r a c t i c e . " Tne

t r i a l c ou r t agreed to so l i m i t c o n s i d e r a -

2 /t i o n cl that testimony.

On O c t o b e r 30 , 1S80, the d i s t r i c t

c ou r t i s sued a Memorandum o f D e c i s i o n which

]_/ c ont inued

t r i a l c o u r t ' s f i n d i n g o f a p a t t e r n o f

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n aga in s t b lacks in grades 4

and 5, she d id not j o i n as a p l a i n t i f f in

the subsequent Baxter l i t i g a t i o n .

2/ T r i a l T r a n s c r i p t , p. 400 (handwri tt en

p a g e number 3 4 0 ) ( t e s t i m o n y o f S h e r r i

McCorkle . )

7

he ld that the Bank had engaged in a p a t t e r n

and p r a c t i c e o f d i s c r i m i n a t i o n in denying

promot ions t o b la ck employees in pay grades

4 and 5. ( P . A . 1 9 4 a ) . With r e s p e c t t o

p r o m o t i o n s o f b l a c k s in pa y g r a d e s 6

and above , however, the c o u r t he ld :

There does not appear t o be a pa t te r n

and p r a c t i c e p e r v a s i v e enough f o r the

c ou r t to o rd er r e l i e f . (P.A. 194a) .

The d i s t r i c t c o ur t c onc luded that two o f

the named p l a i n t i f f s , S y l v i a Coo per and

C o n s t a n c e R u s s e l l , b o t h o f whom were in

pa y g r a d e 6 o r a b o v e , had b e e n d e n i e d

p r o m o t i o n s on the b a s i s o f r a c e . ( P . A .

1 9 2 a - 1 9 3 a ) . The c o u r t ' s O c t o b e r , 19 80 ,

o p i n i o n c o n t a i n e d no r e f e r e n c e t o t h e

t e s t i m o n y o r d i s c r i m i n a t i o n c l a i m s o f

Baxter o r any o f the o th er Baxter p l a i n

t i f f s . The c our t d i r e c t e d coun se l f o r the

p l a i n t i f f s t o propose more d e t a i l e d " f i n d

ings o f f a c t and c o n c l u s i o n s o f law con

8

s i s t e n t w i t h [ i t s ] f i n d i n g s . " ( P . A .

1 9 4 a ) .

Undaunted by the f a i l u r e o f t h e i r

i n i t i a l a t t e m p t t o o b t a i n in t h e C oo pe r

l i t i g a t i o n a d e c i s i o n on t h e m e r i t s o f

t h e c l a i m s o f t h e B a x t e r p l a i n t i f f s ,

c o u n s e l f o r p l a i n t i f f s t r i e d a n o t h e r

approach. The d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s d e c i s i o n

contemplated the appointment o f "a s p e c i a l

master f o r a Stage I I p r o c e e d i n g ] ] t o . . .

i d e n t i f y c l a s s members e n t i t l e d t o r e l i e f . " .

( P . A . 1 9 5 a ) . But t h e c o u r t had f o u n d

c l a s s w i d e d i s c r i m i n a t i o n a g a i n s t o n l y

b l a c k s in p a y g r a d e s 4 and 5 , and t h e

Baxter p l a i n t i f f s were in grades 3, 6 o r 7.

Thus a d e t er m in at i o n as t o which b l a c k s in

g r a d e s 4 and 5 were the v i c t i m s o f d i s

c r i m i n a t i o n would n e c e s s a r i l y have l e f t

s t i l l unreso lved the c laims o f the Baxter

p l a i n t i f f s . S ince those Baxter p l a i n t i f f s

a p p a r e n t l y c o u l d n o t be r e p r e s e n t e d

9

by C o o p e r in the p r i v a t e c l a s s a c t i o n ,

c o u n s e l f o r p l a i n t i f f s u r g e d , in t h e i r

Proposeo Find ings o f Fact and Conc lu s i o ns

o f Law, that the EEOC ins tead be permi t ted

t o pr es s the c la ims o f those employees at

3 /

t n e s t a g e I I p r o c e e d i n g . on F e b r u a r y

27, 1981, however, the de fendant f i l e d a

r e s p o n s e s t r e n u o u s l y o b j e c t i n g t o t h i s

V

p r o p o s a l .

3 / Paragraph 27 o f the Proposed Conc lu

s i o n s o f Law read in p a r t :

The Court i s o f the o p i n i o n . . . that

. . . the M ast er s h o u l d r e c e i v e e v i

d e n c e and make r e c o m m e n d a t i o n s w i t h

r e s p e c t t o P h y l l i s B a x t e r , Brenda

G i l l i a m , Glenda Knott , A l f r e d Harr ison

and S h e r r i M c C o r k l e . . . . They are

w i t h i n the s cope o f [ the] i n d i v i d u a l s

who have c l a i m s whi ch may a p p r o p r i

a t e l y be pursued by EEOC.

This proposed Conc lus i on was not adopted by

the t r i a l c o u r t . See P.A. 283a.

4 / De f en dan t ' s Response t o P l a i n t i f f s '

Proposed Findings o f Fact and Co nc lus i ons

o f Law, pp. 8 - 10 , 14, 18.

10

While t h i s p r o p o s a l f o r EEOC r e p r e s e n

t a t i o n was s t i l l p e n d i n g , c o u n s e l f o r

p l a i n t i f f s made y e t a t h i r d a t t e m p t t o

o b t a i n in the Cooper l i t i g a t i o n a r e s o l u

t i o n o f the m e r i t s o f the Baxter c la i m s .

On March 24, 1381, the Baxter p l a i n t i f f s

moved t o in ter ven e as i n d i v i d u a l s in the

Cooper l i t i g a t i o n . ( J .A . 39 a - 5 1 a ) . The

proposed compla int in i n t e r v e n t i o n a s s e r te d

that each o f the Baxter p l a i n t i f f s had been

den ied a promotion as a r e s u l t o f r a c i a l

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n , bu t d i d n o t a l l e g e t h a t

ther e was any gen era l p r a c t i c e o f d i s c r i m i

n a t i o n a g a i n s t b l a c k s in p a y g r a d e s 6

and a b o v e . The d e f e n d a n t bank o p p o s e d

t h i s m ot i on , i n s i s t i n g that i f the Baxter

p l a i n t i f f s w i sh ed t o p u rs u e t h e i r i n d i -

v i d u a l c la ims they cou ld and should f i l e a

5 /

s e p a r a t e l a w s u i t . The d i s t r i c t c o u r t

5 / See pp. 57 -58 , i n f r a .

- 1 1 -

agreed, and at a hear ing on May 8 , 1981,

den ied from the bench the motion t o i n t e r -

1 /

v e n e ; t h e c o u r t a l s o i n d i c a t e d t h a t

i t would not permit the EEOC to r e p r e se n t

the Baxter p l a i n t i f f s in the Cooper l i t i q a -

1/t i o n .

Four days l a t e r , on May 12, 1981, the

Baxter p l a i n t i f f s , f o l l o w i n g the s ug g e s t i o n

o f the d i s t r i c t c o ur t and the de fe nda nt ,

f i l e d a c i v i l a c t i o n a l l e g i n g r a c i a l

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n in employment in v i o l a t i o n

o f 42 U.S.C. § 1981. On May 29, 1981, the

d i s t r i c t j u d g e e n t e r e d a w r i t t e n o r d e r

f o r m a l l y denying the motion t o in ter ven e in

C o o p e r , e m p h a s i z i n g , " I s e e no r e a s o n

why, i f any o f the would be in te r v e n o r s are

6/ T r a n s c r i p t o f Hearing o f May 8 , 1981,

pp. 17 -18 . That d e c i s i o n was memoria l i zed

in an o r d e r o f May 2 9 , 1 9 8 1 . ( P . A .

2 8 6 a - 2 8 9 a ) .

7 / T r a n s c r i p t o f Hearing o f May 8 , 1981,

p . 19.

12

a c t i v e l y i n t e r e s t e d i n p u r s u i n g t h e i r

c l a i m s , t h e y c a n n o t f i l e a S e c t i o n 1981

s u i t next w e e k . . . . " (P.A. 291a) . On the

same day the judge i s sued h i s F ind ings o f

Fact and C onc lu s i o ns o f Law, which f o r m a l l y

r e j e c t e d the p r o p o s a l t o permit the EEOC to

pursue in the Cooper l i t i g a t i o n the c la ims

o f the Baxter p l a i n t i f f s .

Having thus s u c c e e d e d in t h w a r t i n g

three d i f f e r e n t attempts to o b t a i n in the

C o o £ e r l i t i g a t i o n a r e s o l u t i o n o f t h e

c l a i m s o f t h e B a x t e r p l a i n t i f f s , t h e

de fendant Bank moved on Ju ly 2, 1981, t o

d i s m i s s t h e B a x t e r c l a i m s , a s s e r t i n g

t h a t t h e y were " b a r r e d by r e s j u d i c a t a "

because o f the d e c i s i o n in C oo pe r . ( J .A .

71a e t s e q . ) . On February 26, 1982, the

d i s t r i c t c o u r t denied the motion t o d i s

miss . (P.A. 290a) . The d i s t r i c t ju d ge ,

h o w e v e r , e n t e r e d t h e f i n d i n g s n e c e s s a r y

to permit the de fendant t o appeal from i t s

- 13 -

d e c i s i o n pursuant t o 28 U.S.C. § 1 2 9 2 ( a ) .

The c o u r t o f appeal s granted the de fendant

l e av e t o take such an appeal .

On Ja n u a ry 11 , 1983 , t h e c o u r t o f

a p p e a l s r e v e r s e d t h e d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s

d e c i s i o n in B a x t e r . The F o u r th C i r c u i t

d id not suggest that the t r i a l c o u r t had

i m p l i c i t l y c o n s i d e r e d and r e s o l v e d the

c o n f l i c t i n g c o n t e n t i o n s r e g a r d i n g t h e

s p e c i f i c c l a ims o f the Baxter p l a i n t i f f s ;

i t r e a s o n e d , r a t h e r , t h a t the l a c k o f a

f i n d i n g o f c l a s s w i d e d i s c r i m i n a t i o n i n v o l v

ing grades 6 and above barred as a matter

o f r e s j u d i c a t a any c o n s i d e r a t i o n o f the

p a r t i c u l a r c l a i m s o f b l a c k s in t h o s e

g r a d e s ;

They . . . are . . . p r e c l u d e d by the

de te r m in at i o n o f the D i s t r i c t Court

t h a t t h e r e was no d i s c r i m i n a t i o n in

promotion out o f pay grades above pay

grade 5 . . . . (P.A. 179a) .

One o f t h e B a x t e r p l a i n t i f f s , A l f r e d

Ha rr i so n , was in pay grade 3. Ne i ther the

14

d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s Memorandum o f D e c i s i o n

nor i t s Find ings o f Fact and Co nc lu s i o ns o f

Law even c o n s id e r e d whether there was c l a s s

wide d i s c r i m i n a t i o n regard ing promot ions

o u t o f g r a d e 3 . The c o u r t o f a p p e a l s

n o n e t h e le s s he ld that H a r r i s o n ' s c la im too

was barred by res j u d i c a t a . The d i s t r i c t

c o u r t had found a p r a c t i c e o f d i s c r i m i n a

t i o n in promot i ons from grades 4 and 5, and

t h e c o u r t o f a p p e a l s o v e r t u r n e d t h a t

d e t e r m i n a t i o n :

We . . . r e v e r s e the D i s t r i c t C o u r t ' s

F i n d i n g s and C o n c l u s i o n s o f c l a s s

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n in p r o m o t i o n s o u t o f

g r a d e s 4 and 5 . . . . ( P . A . 1 2 9 a ) .

The c ou r t o f a p pe a l s , nominal ly r e l y i n g on

t h i s c o n c l u s i o n , h e l d t h a t H a r r i s o n ' s

c la im was

pr ec lud ed by our de te rm in at i on on t h i s

appeal that there was no p r a c t i c e o f

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n in pay g r a d e 5 and_

be low. (P.A. 179a) (Emphasis added) .

In f a c t t h e d e c i s i o n o f t h e c o u r t o f

appeal s on the c l a s s c l a i m s , l i k e that o f

15

the d i s t r i c t c o u r t , r e f e r r e d o n l y t o grades

4 and 5, and was devo id o f any d i s c u s s i o n

o f whether there was c la s s w id e d i s c r i m i n a

t i o n ag a i n s t b l ac ks in pay grade 3. Upon

c o n s i d e r a t i o n o f the B a x t e r p l a i n t i f f s '

P e t i t i o n f o r Rehearing and Sugges t i on f o r

Rehearing En Banc , the p a n e l ' s d e c i s i o n was

upheld by an e q u a l l y d i v i d e d (4 -4 ) c o u r t .

(P.A. 188a) .

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I . The q u e s t i o n p r e s e n t e d by t h i s

c a s e i s n o t w h e t h e r a j u d g m e n t on t h e

m e r i t s o f a p a r t i c u l a r i s s u e in a c l a s s

a c t i o n o r d i n a r i l y p r e c lu d es members o f the

c l a s s f r o m r e l i t i g a t i n g t h a t s p e c i f i c

i s s u e . P e t i t i o n e r s acknowledge the c o r

r e c t n e s s o f that p r i n c i p l e . The problem

h e r e i s t o a s c e r t a i n what the d i s t r i c t

c our t in f a c t d e c i d e d .

1 6

1 1 . ( 1 ) The d i s t r i c t c o u r t in the

Cooper l i t i g a t i o n n e i t h e r c o n s id e r e d nor

r e s o l v e d t h e m e r i t s o f t h e i n d i v i d u a l

c la ims o f the Baxter p l a i n t i f f s .

The t r i a l in C o o pe r was a l i m i t e d

s t a g e I p r o c e e d i n g whose p u r p o s e was t o

determine whether there was a p r a c t i c e o f

c l a s s w i d e d i s c r i m i n a t i o n . The d i s t r i c t

c ou r t c onc luded regard ing d i s c r i m i n a t i o n in

pay grades 6 and above that " t h e r e does not

ap pe ar t o be a p a t t e r n and p r a c t i c e o f

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n p e r v a s i v e enough f o r the

c o u r t t o o r d e r r e l i e f . " (P.A. 194a) . That

f i n d i n g does not p r e c lu d e the p o s s i b i l i t y

t h a t t h e r e were p a r t i c u l a r a c t s o f d i s

c r i m i n a t i o n aga in s t the Baxter p l a i n t i f f s

in g r a d e s 6 and a b o v e . T h i s C ou r t has

r e p e a t e d l y r e c o g n i z e d t h a t even in the

absence o f c l a s s w id e d i s c r i m i n a t i o n there

may be " i s o l a t e d or ' a c c i d e n t a l ' o r spo

r a d i c d i s c r i m i n a t o r y a c t s . ' " Teamsters v.

1 7

United S t a t e s , 431 U.S. 324, 336 (1977 ) .

The t r i a l judge in Cooper r e p e a t e d l y

r e fu s e d t o c o n s i d e r and r e s o l v e the c la ims

o f the Baxter p l a i n t i f f s . When the Baxter

p l a i n t i f f s s o u g h t t o t e s t i f y a t t h e

Cooper t r i a l s , the judge ac cepted a de fe nse

p r o p o s a l t h a t t h e c o u r t n o t " r u l e on

i n d i v i d u a l c l a i m s . " The d i s t r i c t c o u r t

r e fu s e d t o permit the EEOC to p r e s e n t the

c l a i m s o f the B a x t e r p l a i n t i f f s in the

Cooper l i t i g a t i o n , and r e j e c t e d an attempt

by t h e B£ x, t. £ L p l a i n t i f f s t o a c t u a l l y

i n t e r v e n e i n C o o p e r . Thus t h e Ba x t e r

p l a i n t i f f s n e v e r had in Co o pe r "a ' f u l l

and f a i r o p p o r t u n i t y ' t o l i t i g a t e [ t h e i r ]

c l a i m s . ' " Kremer v . Chemical Co ns t r u c t i o n

Corp . , 456 U.S. 461, 480 (1982 ) .

The d e c i s i o n o f the co ur t o f appeals

a p p e a r s t o h o l d t h a t the f a i l u r e o f the

d i s t r i c t c o ur t t o d e c id e the mer i t s o f the

i n d i v i d u a l Baxter p l a i n t i f f s in the Cooper

18

c l a s s a c t i o n somehow p r e c l u d e s the Baxter

p l a i n t i f f s from b r i n g i n g a second a c t i o n .

Such a r u l e would be i n c o n s i s t e n t with the

e s t a b l i s h e d p r i n c i p l e t h a t r e s j u d i c a t a

o n l y bars c la ims p r e v i o u s l y r e s o l v e d "on

the m e r i t s . " Krerner v . Chemical Cons t ruc

t i o n Corp . f 456 U.S. 461 , 466 n .6 (1 982) .

(2) Res j u d i c a t a does not apply where

the j u d g e who i s s u e d t h e f i r s t d e c i s i o n

e x p r e s s l y r e ser ved the r i g h t o f the p l a i n

t i f f s t o b r i n g a s e c o n d a c t i o n . At the

hear ing on the Baxter p l a i n t i f f s ' motion t o

i n t e r v e n e in C o o p e r , t h e d i s t r i c t j u d g e

announced:

I 'm go ing t o deny the motion wi thout

p r e j u d i c e t o t h e i n d i v i d u a l r i g h t s

o f the f o u r would be i n t e r v e n o r s t o

mainta in a se pa ra te a c t i o n . 8/

The c o u r t ' s w r i t t e n o r d e r d e n y i n g t h a t

motion r e i t e r a t e d :

8/ See p. 60, infra.

- 19

I s e e no r e a s o n why, i f any o f the

would be i n t e r v e n e r s are a c t i v e l y

i n t e r e s t e d in pursuing t h e i r c la i m s ,

they cannot f i l e a S e c t i o n 1981 s u i t

next week, nor why they cou ld not f i l e

a c l a i m w i t h EEOC n e x t week. ( P . A .

2 8 8 a ) .

Thus i t was the c l e a r i n te n t o f the d i s

t r i c t c o u r t in Cooper t o permit the in s ta n t

l i t i g a t i o n .

The a p p l i c a t i o n o f r e s j u d i c a t a i s

p a r t i c u l a r l y i n a p p r o p r i a t e s i n c e t h e

de fendant in Cooper e x p r e s s l y argued that

B a x t e r c o u l d and s h o u l d f i l e h e r own

l a w s u i t . In s u c c e s s f u l l y oppos ing B a x t e r ' s

m o t i o n t o i n t e r v e n e in C o op er the Bank

a s s e r t e d :

A p p l i c a n t s . . . can s t i l l go t o the

EEOC o f f i c e and f i l e a l l the charges

they d e s i r e . . . t h e r e f o r e , there i s no

way ther e w i l l be any p r e j u d i c e to the

a p p l i c a n t s in d e n y i n g t h e i r m o t i o n ,

s i n c e they can pursue any i n d i v i d u a l

c la ims they have in se parate p r o c e e d

in g s . 9 /

9/ See p. 61, infra.

20

Less than two months a f t e r i n s i s t i n g in

Cooper that the Baxter p l a i n t i f f s c o u ld and

should f i l e t h e i r own s u i t , the Bank moved

t o d i sm is s that s u i t , arguing that i t was

barred by res j u d i c a t a .

I I I . The Baxter p l a i n t i f f s are barred

by c o l l a t e r a l e s t o p p e l from l i t i g a t i n g o n l y

those i s s u e s which were a c t u a l l y d ec id e d in

C oo pe r .

The B a x t e r p l a i n t i f f s in pay g r a d e s

6 and above are bound by the Cooper d e c i

s i o n that any c l a s s w i d e d i s c r i m i n a t i o n in

those grades was not s u f f i c i e n t to warrant

a c la s s w id e remedy.

One o f the Baxter p l a i n t i f f s , A l f r e d

Harr i son , i s in pay grade 3. S ince n e i t h e r

c o u r t b e l o w e v e r c o n s i d e r e d o r d e c i d e d

whether there was c la s s w id e d i s c r i m i n a t i o n

in pay g r a d e 3, H a r r i s o n s h o u l d be p e r

m i t t e d t o o f f e r p r o o f on remand o f the

21

e x i s t e n c e o f such a p a t t e r n and p r a c t i c e o f

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n .

The d i s t r i c t c o u r t f ou nd t h a t t h e r e

had been i n t e n t i o n a l d i s c r i m i n a t i o n ag a i n s t

two named p l a i n t i f f s in C o o p e r , S y l v i a

Cooper and Constance R u s s e l l , both o f whom

were in pay grade 6 o r above . The c o ur t o f

a p p e a l s r e v e r s e d t h e s e f i n d i n g s o f d i s

c r i m i n a t i o n ; the c o ur t o f a p pe a l s , however,

app are nt l y misunders tood the d i s t r i c t c our t

to have he ld that there was no d i s c r i m i n a

t i o n in grades 6 and above. A c c o r d i n g l y ,

the c ou r t o f a p pe a l s ' d e c i s i o n regard ing

the i n d i v i d u a l c la ims o f Cooper and R u s s e l l

should be vacated and remanded.

ARGUMENT

I . THE BINDING EFFECT OF DECISIONS

IN CLASS ACTIONS___________________

The q u e s t i o n presented by t h i s case i s

not whether a judgment de termining on the

mer i t s a p a r t i c u l a r i s s ue in a c l a s s a c t i o n

22

o r d i n a r i l y p r e c l u d e s members o f the

c l a s s f r o m r e l i t i g a t i n g t h a t s p e c i f i c

i s s u e . P e t i t i o n e r s d id not q u e s t i o n that

p r i n c i p l e below and do not seek t o cio so

he r e . The c o u r t o f ap p e a l s , however, ap

p l i e d a f a r more sweeping r u l e , app ar ent ly

assuming that an adverse de te r m in at i o n on

t h e m e r i t s o f any s i n g l e c l a s s i s s u e

p r e c l u d e s c l a s s members from l i t i g a t i n g a l l

o t h e r i s s u e s i n v o l v i n g t h e same s u b j e c t

mat ter .

P r i o r t o the 1966 amendments t o Rule

23, there was in the case o f a s o - c a l l e d

" s p u r i o u s " c l a s s a c t i o n no p r o c e d u r e

10/ The a p p l i c a t i o n o f t h i s p r i n c i p l e

p r es u p p os es , i n t e r a l i a , tha t the c l a s s was

in f a c t c e r t i f i e d , t h a t c l a s s members

r e c e i v e d any r e q u i r e d n o t i c e , t h a t the

named p l a i n t i f f adequate ly r e pr ese n ted the

i n t e r e s t s o f the c l a s s , and that the co ur t

r e nde r i ng the d e c i s i o n had j u r i s d i c t i o n to

do s o . See 18 C. Wr ight and A. M i l l e r ,

F e d e r a l P r a c t i c e and P r o c e d u r e , § 4455

(19 7 2 ) ; 3B Moore ' s Federal P r a c t i c e 1i 2360

(2d ed . 1982) .

23

f o r de termining p r i o r t o judgment which o f

the p o t e n t i a l members o f the c l a s s c la imed

in the compla int were ac t ua l members and

would thus be bound by the ju d g m e n t . A

number o f c o u r t s h e l d o r i n t i m a t e d t h a t

c l a s s members might be permi tted t o i n t e r

vene a f t e r a d e c i s i o n on the mer i t s f a v o r

ab le t o t h e i r i n t e r e s t s , in o rd er t o secure

the b e n e f i t o f the d e c i s i o n f o r themse lves ,

a l t h o u g h t h e y would p r e s u m a b ly be u n a f

f e c t e d by an u n f a v o r a b l e d e c i s i o n . In

o r d e r t o prevent such "one-way i n t e r v e n

t i o n , " s e c t i o n s ( c ) ( 1 ) and ( c ) ( 2 ) were

a d d e d t o R u l e 2 3 , d i r e c t i n g t h a t t h e

p r o p r i e t y o f c l a s s c e r t i f i c a t i o n be r e

s o l v e d " a s s o o n as p r a c t i c a b l e , " and

r e q u i r i n g c l a s s members in a Rule 2 3 ( b ) ( 3 )

a c t i o n t o d e c i d e p r i o r t o any r e s o l u t i o n on

the mer i t s whether t o remain in the c l a s s .

American Pipe Co ns t r u c t i o n Co. v . Utah, 414

U.S . 538 , 54 6 -9 ( 1 9 7 4 ) . Rule 2 3 ( c ) ( 3 )

24

d i r e c t s the c o u r t a d j u d i c a t i n g a c l a s s

a c t i o n to in c l ud e in i t s judgment a d e s i g

na t i on o f the i n d i v i d u a l s who are memoers

o f the a f f e c t e d c l a s s .

Rule 23 does n o t , however, purpor t to

"determine the b ind ing e f f e c t o f a judgment

. . . [or ] p r e s c r i b [ e ] any p a r t i c u l a r a d j u d i -

JJ_/

c a t o r y e f f e c t t o i t ------ " Rather , Rule

23 d i r e c t s t h e a t t e n t i o n o f t h e c o u r t

d e c i d i n g a c l a s s a c t i o n , and o f any c o ur t

sub sequent ly c a l l e d upon to a s c e r t a i n the

a d j u d i c a t o r y e f f e c t o f that d e c i s i o n , to

the a c t u a l language o f the judgment. I t i s

in the p a r t i c u l a r t erms o f t h e judgment

t h a t the f i r s t c o u r t i s c a l l e d upon t o

s p e l l out what i t has de c i de d and wfto were

the p a r t i e s t o t h a t l i t i g a t i o n , and i t

1 1/ 7A C. Wright and A. M i l l e r , Federal

P r a c t i c e and P r o c e d u r e , § 17 89 , p . 177

(1972 ) .

25

i s by t h o s e t e rms t h a t the r e s j u d i c a t a

e f f e c t o f the judgment must be determined .

In a s c e r t a i n i n g what i s s u e s o r c l a i m s

cannot be l i t i g a t e d because o f the d e c i s i o n

in an e a r l i e r c l a s s a c t i o n , " s p e c i a l care

nay be requ i r ed in i d e n t i f y i n g the i s sue s

or c la ims prese nte d and in r e l a t i n g them to

the s c o p e o f the c l a s s a c t i o n . " 18 C.

Wright & A. M i l l e r , Federal P r a c t i c e and

1 2/

P r o c e d u r e , § 4455, p . 473 ( 1 9 7 2 ) ~

In a c i v i l a c t i o n on b e h a l f o f a

s i n g l e i n d i v i d u a l , one would o r d i n a r i l y

e x p e c t t h e p l a i n t i f f t o p r e s e n t , and

the c o u r t t o r e s o l v e , a l l o f h i s o r her

c l a i m s and c o n t e n t i o n s w i th r e g a r d t o a

J_2/ See a l s o F. James, J r . & G. Hazard,

J r * ' C i v i l P r o c e d u r e , § 11 .2 8 , p. 587 (2d

ed. 1S77) ( " [ T ] h e very nature o f a c l a s s

s u i t r e q u i r e s t h a t t h e r u l e s o f r e s

j u d i c a t a be a p p l i e d t o i t w i th s p e c i a l

c a u t i o n . " }

26

p a r t i c u l a r s u b j e c t matter or t r a n s a c t i o n .

In c e r t a i n in s ta n c es an i n d i v i d u a l p l a i n

t i f f may be r e q u i r e d t o do s o . But in

d e t e r m i n i n g t h e s c o p e o f t h e d e c i s i o n

in a c l a s s a c t i o n the c o u r t s cannot indulge

in any assumption that every p o s s i b l e c la im

a g a i n s t the d e f e n d a n t o f each and e v e r y

c l a s s member was in f a c t l i t i g a t e d and

d e c i d e d . A c l a i m o f a p a r t i c u l a r c l a s s

member, o r an i s s u e o r f a c t r e l e v a n t t o

that c la i m , i s not o r d i n a r i l y a d ju d i c a t e d

in a c l a s s a c t i o n u n l e s s t h e c l a i m o r

q u e s t i o n i s common to both the c l a s s and

the named p l a i n t i f f , and un less that named

p l a i n t i f f i s in a p o s i t i o n t o " f a i r l y and

a d e q u a t e l y p r o t e c t the i n t e r e s t s o f the

c l a s s . " Ru l e 2 3 ( a ) . Rule 2 3 ( b ) p o s e s

ye t a d d i t i o n a l l i m i t a t i o n s re gard ing what

c la ims and i s s u e s may in f a c t be l i t i g a t e d

in a c l a s s a c t i o n . "The mere f a c t that an

ag gr i eved p r i v a t e p l a i n t i f f i s a member o f

27

an i d e n t i f i a b l e c l a s s o f persons o f the

same race o r n a t i o n a l o r i g i n i s i n s u f f i

c i e n t t o e s t a b l i s h h i s s tand ing t o l i t i g a t e

on t h e i r b e h a l f a l l p o s s i b l e c l a i m s o f

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n aga in s t a common e m plo yer . "

General Telephone Co. v . F a l c o n , 457 U.S.

147, 159 n. 15. (1982) (emphasis added) In

sum, whi le an i n d i v i d u a l p l a i n t i f f o r d i n a r

i l y would n o t , and under some c i r cumstances

c o u l d n o t , p i c k and c h o o s e among t h e

r e l a t e d c la ims and i s s ue s t o p r e s e n t in a

s i n g l e l a w s u i t , " c a r e f u l a t t e n t i o n t o the

requi rements o f . . . Rule . . . 23" r e q u i r e s

j u s t such s e l e c t i v i t y in the c h o i c e o f

q u e s t i o n s t o be r e s o l v e d in a c l a s s a c t i o n .

East Texas Motor F re i ght v . R o d r iq u e z , 431

U.S. 395, 405 (1977 ) .

Those mat ters which a c o u r t d e c l i n e s

t o a c t u a l l y r e s o l v e in a c l a s s a c t i o n o f

c ourse remain open f o r l i t i g a t i o n in some

fu tu re a c t i o n . The same i s t rue o f i s s ue s

28

which co uns e l f o r the r e p r e s e n t a t i v e p a r t y ,

mind ful o f the requi rements o f Rule 23 and

o f the problems o f m an a ge ab i l i t y a s s o c i a t e d

with any c l a s s a c t i o n , d e c l i n e s t o pr es ent

o r p r es s f o r r e s o l u t i o n . Falcon n e i t h e r

encourages nor r e q u i r e s the c l a s s r e p r e s e n

t a t i v e t o p l ead the broad es t c o n c e i v a b l e

c l a s s c la im and f o r c e the c o ur t t o reduce

i t t o a more manageable s u i t c onsonant with

R u l e 2 3 . I f t h e d e f e n d a n t in a c l a s s

a c t i o n b e l i e v e s that the membership o f the

proposed c l a s s or the s cope o f the proposed

c l a s s c l a i m s ar e t o o n a r r o w l y d e f i n e d ,

i t i s f r e e t o u r g e t h e t r i a l c o u r t t o

expand o r a l t e r e i t h e r . But a de fendant

d i s s a t i s f i e d with the c l a s s d e f i n i t i o n or

the c la ims o f f e r e d by a p l a i n t i f f cannot

wi thho ld i t s o b j e c t i o n and l a t e r complain

that o t h e r i s s u e s should have been l i t i

gated o r that o t h e r i n d i v i d u a l s should have

29

oeen members o f the c l a s s .

A s c e r t a i n i n g p r e c i s e l y what i s s u e s

were in f a c t l i t i g a t e d and r e s o l v e d in a

c l a s s a c t i o n w i l l not always be a s imple

t a s k . The mere f a c t t h a t a c o m p l a i n t

a l l e g e s a wide v a r i e t y o f c l a ims does not

i t s e l f ensure that the r e p r e s e n t a t i v e par ty

cou ld o r d id in f a c t l i t i g a t e a l l or most

o f them at t r i a l . C f . Eas t Texas Motor

13/

13/ " Th e b a s i c e f f o r t t o l i m i t c l a s s

a d j u d i c a t i o n as c l o s e as p o s s i b l e t o

m a t t e r s common t o members o f the c l a s s

f r e q u e n t l y r e q u i r e s that n o n p a r t i c i p a t i n g

members o f the c l a s s remain f r e e t o pursue

i n d i v i d u a l a c t i o n s that would be merged or

b a r r e d by c l a i m p r e c l u s i o n had a p r i o r

i n d i v i d u a l a c t i o n been b r o u g h t f o r the

r e l i e f demanded in the c l a s s a c t i o n . An

i n d i v i d u a l who has s u f f e r e d p a r t i c u l a r

i n j u r y as a r e s u l t o f p r a c t i c e s e n jo i n e d in

a c l a s s a c t i o n , f o r i n s t a n c e , should remain

f r e e t o seek a damages remedy even though

c l a i m p r e c l u s i o n would d e f e a t a s e c o n d

a c t i o n had the f i r s t a c t i o n been an i n d i

v i d u a l s u i t f o r t h e same i n j u n c t i v e

r e l i e f . " 18 C. Wright & A. M i l l e r , Federal

P r a c t i c e and P r o c e d u r e , § 4 4 5 5 , p . 474

(1972 ) .

30

F re i g h t v . R o d r i g u e z , 431 U.S. 395, 405-06

( 1 9 7 7 ) . In some in s ta n c e s l i m i t a t i o n s on

t h e c l a i m s o r i s s u e s a c t u a l l y p r e s e n t e d

and r e s o l v e d in a c l a s s a c t i o n may be

a p p a r e n t on t h e f a c e o f t h e c o m p l a i n t

i t s e l f . S e e , e . g . , Bogara v . C o o k , 586

F. 2d 399 (5th C i r . 1978) ( i n d i v i d u a l a c t i o n

f o r damages n o t b a r r e d by e a r l i e r c l a s s

J_4/

a c t i o n seeking o n l y i n j u n c t i v e r e l i e f ) .

The terms o f the t r i a l c o u r t ' s d e c i s i o n or

o r d e r re gard ing c e r t i f i c a t i o n may d e f i n e

t h e c l a s s i s s u e s more n a r r o w l y than the

c o m p l a i n t i t s e l f . See e . g . , Vioodson v .

F u l t o n , 614 F . 2d 940, 942 (4th C i r . 1980)

( c e r t i f i c a t i o n d e c i s i o n e x c l u d e d c l a i m s

r eg ard in g d i s c r i m i n a t o r y d i s c h a r g e ) . In

14/ In s u s t a i n i n g that i n d i v i d u a l a c t i o n ,

the F i f t h C i r c u i t noted that i t had "no way

o f knowing that [ the e a r l i e r s u i t ] would

have been manageable as a c l a s s a c t i o n i f

i n d i v i d u a l damage r e l i e f had b e e n r e

q u e s t e d . " 586 F .2d at 408.

31

the i n s t a n t c a s e , f o r example, the Cooper

c o m p l a i n t a l l e g e d a g e n e r a l p r a c t i c e o f

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n on t h e b a s i s o f b o t h

race and sex (J .A . 15a) , but the c e r t i f i c a

t i o n o r d e r l i m i t e d t h e c l a s s c l a i m t o

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n on the b a s i s o f r a c e . ( J .A .

27 a ) . The s cope o f the i s su es o r c la ims

a c t u a l l y l i t i g a t e d at t r i a l may be narrower

s t i l l . S e e , e . g . , Marshal l v . K i r k l a n d ,

602 F.2d 1282, 1298 (8th C i r , 1979) ( d e c i

s i o n on c l a s s c l a i m n o t r e s j u d i c a t a

as t o c l a s s members whose c laims were not

in f a c t p r es ent ed t o the t r i a l c o u r t ) . The

o p i n i o n and judgment o f the d i s t r i c t c o ur t

must be c a r e f u l l y s c r u t i n i z e d t o a s c e r t a i n

whether each o f the c l a s s c la ims or i s s ue s

prese nte d at t r i a l was in f a c t r e s o l v e d by

the c o u r t on the m e r i t s .

The p o s s i b i l i t y t h a t a t r i a l c o u r t

w i l l not in f a c t r e s o l v e a l l the i s s u e s a

p l a i n t i f f seeks t o l i t i g a t e i s p a r t i c u l a r l y

32

r e a l when, as i s o f t e n the c a s e in Rule

2 3 ( b ) ( 3 ) c l a s s a c t i o n s , the c o u r t uses the

f a m i l i a r d e v i c e o f a s p l i t t r i a l . See

F r a n k e l , "Some P r e l i m i n a r y O b s e r v a t i o n s

Concerning C i v i l Rule 23 , " 43 F.R.D. 39, 47

(1 96 7 ) . Such b i f u r c a t e d p r o c e e d i n g s are

p a r t i c u l a r l y common in the t r i a l c o u r t o f

c o m p l e x T i t l e V I I c l a s s a c t i o n s . In

such cases

[ a ] t the i n i t i a l , " l i a b i l i t y " s t a g e

. . . [ the p l a i n t i f f ] i s not r e q u i re d to

o f f e r e v i d e n c e t h a t each p e r s o n f o r

whom i t w i l l u l t i m a t e l y s e e k r e l i e f

was a v i c t i m o f the e m p l o y e r ' s d i s

c r i m in a t o r y p o l i c y . I t s burden i s t o

e s t a b l i s h a prima f a c i e case that such

a p o l i c y e x i s t e d . . . . [A] d i s t r i c t

c o u r t must us u a l l y c onduct a d d i t i o n a l

p r o c e e d in g s a f t e r the l i a b i l i t y phase

o f the t r i a l t o determine the s cope o f

t h e i n d i v i d u a l r e l i e f . . . . [ T ] h e

q u e s t i o n o f i n d i v i d u a l r e l i e f does not

a r i s e u n t i l i t has been p r o v e d t h a t

the employer has f o l l o w e d an employ

ment p o l i c y o f unlawful d i s c r i m i n a t i o n .

I n t e r n a t i o n a l Brotherhood o f Teamsters v.

United S t a t e s , 431 U.S. 324, 360-62 (1 97 7 ) .

Shou ld a t r i a l c o u r t c o n c l u d e in such a

33

case that there was no c la s s w id e d i s c r i m i

n a t i o n , i t would o r d i n a r i l y have no o c c a

s i o n t o c o n s i d e r at any l a t e r p r oc e e d i n g

w h e t h e r p a r t i c u l a r i n d i v i d u a l s m i g h t

n o n e t h e l e s s h a v e b e e n t h e v i c t i m s o f

i s o l a t e d ac t s o f d i s c r i m i n a t i o n . Just as

the c o u r t s cannot assume t h a t , i f a c l a s s

i s c e r t i f i e d , " a l l w i l l be w e l l f o r s u r e l y

the p l a i n t i f f w i l l win and manna w i l l f a l l

on a l l members o f t h e c l a s s , " Gen era l .

T e l e p h o n e v . __F a l c o n , 457 U. S . a t 1 6 1 ,

so t o o they cannot assume that every c la im

somehow r e l e v a n t t o the p l a i n t i f f s ' com

p l a i n t w i l l in f a c t be l i t i g a t e d and

r e s o l v e d on the m e r i t s .

I I . THE BAXTER CLAIMS ARE NOT BARRED

BY RES JUDICATA______________________

(1) The D i s t r i c t Court in Cooper Did

Not Decide The Meri ts o f th e

Baxter Claims

A f i n a l judgment on the m e r i t s o f a

c l a i m p r e c l u d e s the p a r t i e s , i n c l u d i n g

34

c l a s s m e m b e r s , f r o m r e l i t i g a t i n g t h a t

c la i m . Federated Department S t o r e s , I n c , v .

M o i t i e , 452 U.S. 394, 398 (1 98 1 ) . But t h i s

p r i n c i p l e o f r e s j u d i c a t a does not apply t o

a l l cas es in which a par ty f a i l s t o o b t a i n

the r e l i e f i t sought in the i n i t i a l l i t i g a

t i o n ; o n l y i f t h a t d e n i a l o f r e l i e f was

based on a d e c i s i o n on the mer i t s o f the

c la im i s the u n s u c c e s s fu l p a r t y t h e r e a f t e r

pr ec lu d ed from l i t i g a t i n g the same c la im.

" I f the f i r s t s u i t was d i sp o s e d o f on any

ground which d id not go t o the m e r i t s o f

the a c t i o n , the judgment r e n d e r e d w i l l

prove no bar t o another s u i t . " C o s t e l l o v .

United S t a t e s , 365 U.S. 265, 286 (1 96 1 ) ;

see R e s i a t e m e n t _ ^ _ J u d £ n i e n t s 2d, § 20

( 1 9 8 2 ) . This Court has r e p e a t e d l y d e c l i n e d

t o g i v e such p r e c l u s i v e e f f e c t t o d e c i s i o n s

whi ch f a i l e d t o r e s o l v e the m e r i t s o f a

35 -

d i s p u t e d c l a i m . a f i n d i n g t h a t some

e a r l i e r a c t i o n d id r e s o l v e the mer i t s o f a

c la im , l i k e any a p p l i c a t i o n o f r e s j u d i

c a t a , must be made " o n l y a f t e r c a r e f u l

s c r u t i n y . " Brown v . F e l s e n , 442 U.S. 127,

132 ( 1 979) .

There i s no qu e s t i o n that the Baxter

p l a i n t i f f s wanted and r e p e a t e d l y attempted

t o l i t i g a t e t h e i r i n d i v i d u a l c la ims in the

Co 0£ £ £ a c t i o n . I t i s e q u a l l y c l e a r ,

however, that the de fendants s u c c e s s f u l l y

prevented them from do ing so . Although the

Baxter p l a i n t i f f s were permit ted t o t e s t i f y

at the Cooper t r i a l , the de fendant i n s i s t e d

that the d i s t r i c t c our t not r e s o l v e t h e i r

i n d i v i d u a l c l a i m s , b u t c o n s i d e r t h e i r

t e s t i m o n y o n l y i n s o f a r as i t t e nd e d t o

15/ C o s t e l l o v . United S t a t e s , 36 5 U.S.

765 ( 1 9 6 1 ) ; Hughes v . Un i ted S t a t e s , 71

U.S. (4 W a l l . ) 232 (1 86 6 ) ; Gilman v. R i v e s ,

35 U.S. (10 P e t . ) 298 (1836 ) .

36

e s t a b l i s h t h e e x i s t e n c e o f c l a s s w i d e

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n . This d i s t i n c t i o n was made

when t h e f i r s t B a x t e r p l a i n t i f f was

c a l l e d t o the s tand :

[DEFENSE COUNSEL]: . . . My understand

ing now i s t h a t , e x c e p t f o r [ C o o p e r

and the thre e o th e r named p l a i n t i f f s ] ,

you w o n ' t r u l e on i n d i v i d u a l c l a i m s

and t h a t t h i s e v i d e n c e we h e a r j u s t

g o e s t o t h e i r c l a i m t h a t t h e r e i s a

p a t t e r n and p r a c t i c e .

* * *

THE COURT: . . . I think the answer t o

your q u e s t i o n i s that i s c o r r e c t . The

o n l y p e o p l e as t o whose r i g h t s the

C ou r t has a d u t y t o make a p r e s e n t

d e c i s i o n ar e t h e f o u r p e r s o n s named

who have themselves a s s e r te d in t h i s

case a p e r s o na l r i g h t t o r e c o v e r y . 16/

F o l l o w i n g t h e d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s i n i t i a l

Memorandum o f D e c i s i o n , which apparent ly

p r e c l u d e d C o o pe r f rom r e p r e s e n t i n g the

i n t e r e s t s o f the Baxter p l a i n t i f f s at the

Stage I I p r o c e e d i n g s , c o uns e l f o r p l a i n -

16/ See n . 2 , supra.

37

t i f f s sugges ted that the EEOC be permi t ted

t o pr es en t in those p r o c ee d i n gs the i n d i

v i d u a l c l a i m s o f the B a x t e r p l a i n t i f f s .

(See p . 9 , s u p r a ) . The d e f e n d a n t a g a in

o b j e c t e d :

The d e f e n d a n t s u b m i t s t h a t t h o s e

w i t n es s es are not e n t i t l e d t o p a r t i

c i p a t e in Stage I I p r o c e e d i n g s . The

pe op le in qu e s t i o n t e s t i f i e d at t r i a l ,

but had not p a r t i c i p a t e d in the a c t i o n

o t h e r than as p a s s i v e c l a s s members.

T h e i r t e s t i m o n y was on the i s s u e o f

£i£.JLS l i a b i l i t y , a l t h o u g h t h e i r

t e st imony f ocused on pe rs o na l g r i e v

ances . These peop le are not p a r t i e s

[and] they are not i n t e r v e n o r s . . . . 17/

The t r i a l c o u r t uphe ld the d e f e n d a n t ' s

a r g u m e n t t h a t t h e EEOC s h o u l d n o t be

J_8/

permi t ted t o pursue the Baxter c la i m s .

F i n a l l y , the Baxter p l a i n t i f f s attempted to

in te r ve ne in the Cooper l i t i g a t i o n in o rder

J_7/ De fen da n t ' s Response to P l a i n t i f f s '

Proposed F ind ings o f Fact and Conc lus i ons

o f Law, p . 8. (Emphasis in o r i g i n a l ) .

18/ See p . 11, s u p ra .

38

t o p r e s e n t t h e i r i n d i v i d u a l c l a i m s f o r

a d j u d i c a t i o n at the Stage I I p r o c e e d i n g s .

The d e f e n d a n t s u c c e s s f u l l y o p p o s e d t h i s

attempt as w e l l . (P.A. 28 6a - 289 a ) . Far

f r om h a v i n g in C o o pe r "a ' f u l l and f a i r

o p p o r t u n i t y ' t o l i t i g a t e [ t h e i r ] c l a i m , "

Kremer v . Chemical C o n s t r u c t i o n C or p . , 456

U.S. 461, 480 (1 98 2 ) , the Baxter p l a i n t i f f s

in f a c t had no o p p o r t u n i t y whatever t o do

so in that ca se .

I t i s a l s o c l e a r that the t r i a l c o ur t

d i d n o t in f a c t d e c i d e t h e i n d i v i d u a l

c la ims o f the Baxter p l a i n t i f f s . P h y l l i s

B a x t e r , f o r e x a m p l e , a l l e g e d t h a t on

s e v e r a l o c c a s i o n s between 1975 and 1978 she

a p p l i e d f o r c e r t a i n v a c a n c i e s , " b u t was

den ied the p o s i t i o n s beause o f her race and

c o l o r " . ( P . A . 6 6 a ) . P l a i n t i f f G i l l i a m

contended that she was denied promot ion to

a j u n i o r C o m p u t e r C o n s o l e p o s i t i o n in

November o f 1976 b e c a u s e o f r a c i a l d i s -

39 -

c r i m i n a t i o n . P l a i n t i f f s K n o t t , Harr ison

and McCorkle made e q u a l l y s p e c i f i c c l a ims

about d e n i a l s o f promotions t o p a r t i c u l a r

v a c a n c i e s . ( . Id*) N e i t h e r the d i s t r i c t

c o u r t ' s Memorandum o f D e c i s i o n (P.A. 191a)

nor the Judgment (P.A. 52a-62a) c o n t a in any

r e f e r e n c e w h a te v e r t o B a x t e r , G i l l i a m ,

Knott , Harr i son , o r McCorkle. The lower

c o u r t ' s F ind ings o f Fact and Co nc lus i ons o f

Law d e s c r i b e t h e c l a i m s o f t h e B a x t e r

p l a i n t i f f s , n o t i n g t h a t in g e n e r a l t h e y

were f u l l y q u a l i f i e d f o r the p r o m o t i o n s

they sought and o f t e n more exp er i en ced than

the whi tes who were a c t u a l l y appointed t o

the p o s i t i o n s i n v o l v e d . (P.A. 247a-254a ) .

But nowhere in the Findings i s there the

s l i g h t e s t s u g g e s t i o n that the t r i a l judge

had in f a c t reached any c o n c l u s i o n as to

why the Baxter p l a i n t i f f s had been denied

those p a r t i c u l a r promot i ons .

40

The C ou r t o f A p p e a l s , h o w e v e r , b e

l i e v e d that the c la ims o f f o u r o f the f i v e

19 /

B a x t e r p l a i n t i f f s were p r e c l u d e d by

r e s j u d i c a t a b e c a u s e o f t h e d i s t r i c t

c o u r t ' s d e c i s i o n r e g a r d i n g c l a s s w i d e

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n . At the time o f t r i a l these

f o u r p l a i n t i f f were in pay g r a d e s 6 o r

above , and both Cooper and the EEOC c laimed

and s o u g h t t o p r o v e t h a t t h e r e was a

ge n er a l p r a c t i c e o f p r om ot i ona l d i s c r i m i n a

t i o n aga in s t b l ac ks in those pay gr ade s .

The d i s t r i c t c o ur t c onc luded t h a t , o the r

t h a n r e g a r d i n g b l a c k s in pa y g r a d e s 4

and 5 , " t h e r e d o e s n o t a p p e a r t o be a

p a t t e r n and p r a c t i c e o f d i s c r i m i n a t i o n

p e r v a s i v e enough f o r the c o u r t t o o r d e r

r e l i e f . " (P.A. 194a) . This h o l d in g cannot

p l a u s i b l y be read as a d e c i s i o n that there

had never been any d i s c r i m i n a t i o n aga ins t

1_9/ Baxter , Knott , G i l l i a m and McCorkle.

41

b l a c k s above g r a d e 5, o r even t h a t such

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n had b e e n p a r t i c u l a r l y

rare o r unique. S ince the d i s t r i c t c our t

in the same o p i n io n a l s o held that p l a i n

t i f f s Cooper and R u s s e l l , both o f whom were

in grades 6 o r above , "were d i s c r im in a t e d

a g a i n s t on ac c ou n t o f t h e i r r a c e " ( P . A .

19 2a ) , i t s h o l d i ng o n t h e c l a s s c l a i m

c a n n o t mean t h a t the re was no such d i s -

c r i m i n c i t i o n in t h o s e g r a d e ! s . The o n l y

p l a u s i b l e c o n s t r u c t i o n o f t h e c o u r t ' s

d e c i s i o n i s t h a t a c t s o f d i s c r imin at i o n

a g a i n s t e m p lo y e e s in g r ades 6 and above

were not s u f f i c i e n t l y widespread t o warrant

a c la s s w id e remedy.

That the d i s t r i c t j u d g e ' s d e c i s i o n on

c la s s w id e d i s c r i m i n a t i o n in grades 6 and

a b o v e was n o t i n t e n d e d t o r e s o l v e t h e

p a r t i c u l a r i n d i v i d u a l c la ims o f the Baxter

p l a i n t i f f s , o r o f any o t h e r e m p l o y e e s ,

was c o n f i r m e d by the j u d g e ' s s u b s e q u e n t

42

s ta tements and o r d e r s . At the hear ing on

the a p p l i c a t i o n o f the Baxter p l a i n t i f f s to

i n t e r v e n e in C o o g e r , a q u e s t i o n a r o s e

reg ar d in g whether the j u d g e ' s p r i o r d e c i

s i o n on the c l a s s c la im might somehow l i m i t

subsequent c o n s i d e r a t i o n o f the i n d i v i d u a l

c l a i m s . The t r i a l c o u r t e x p r e s s l y r e j e c t e d

any s u c h c o n s t r u c t i o n o f i t s e a r l i e r

d e c i s i o n :

I 'm not r u l i n g that t h e i r r i g h t s are

barred — t h e i r i n d i v i d u a l r i g h t s to

make i n d i v i d u a l c l a i m s are b a r r e d

by res j u d i c a t a . You can have s e v e r a l

pe op le who may be e n t i t l e d t o r e c o v e r y

w i t h o u t t h a t e v i d e n c e p r o v i n g t h a t

there had been a c la s s w id e d i s c r i m i n a

t i o n . 20/

In i t s o r d e r d e n y i n g i n t e r v e n t i o n , the

d i s t r i c t c o ur t exp l a ine d that i t s e a r l i e r

o p i n i o n had merely " found no p r o o f o f any

c l a s s w i d e d i s c r i m i n a t i o n a b o v e g r a d e

5 .......... " ( P . A. 287a) .

20/ T r a n s c r i p t o f Hearing o f May 8, 1981,

p . 20.

43

The d i s t i n c t i o n drawn by the d i s t r i c t

c o u r t between p r o o f o f c l a s s w id e d i s c r i m i

n a t i o n and p r o o f o f i n d i v i d u a l a c t s o f

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n i s f u l l y supported by the

d e c i s i o n s o f t h i s C o u r t . In T e a m s t e r s

v. United S t a t e s , 431 D.S. 324 ( 1 9 7 7 ) , che

C o u r t h e l d t h a t p r o o f o f a p a t t e r n o r

p r a c t i c e o f d i s c r i m i n a t i o n r e q u i r e s more

t h a n p r o o f o f " t h e mere o c c u r r e n c e o f

i s o l a t e d o r ' a c c i d e n t a l ' o r s p o r a d i c

d i s c r i m i n a t o r y a c t s . " 431 U .S . at 336.

G e n e r a l T e l e p h o n e v . F a l c o n n o t e d t h a t

there i s a "wide gap" between the o c c u r

rence o f an i n d i v i d u a l ac t o f d i s c r i m i n a

t i o n and e x i s t e n c e o f a c la s s w id e d i s c r i m i

na tory p r a c t i c e :

Even though ev idence that [a m in o r i t y

employee] was passed over f o r promo

t i o n when s e v e r a l l e s s d e s e r v i n g

whites were advanced may support the

c o n c l u s i o n t h a t [ t h e e m p l o y e e ] was

d e n i e d the p r o m o t i o n b e c a u s e o f h i s

n a t i o n a l o r i g i n , such ev idence would

not n e c e s s a r i l y j u s t i f y the a d d i t i o n a l

44

i n f e r e n c e . . . that t h i s d i s c r i m i n a t o r y

t r e a t m e n t i s t y p i c a l o f [ t h e em

p l o y e r ' s ] p r o m o t i o n a l p r a c t i c e s . . . .

457 U.S. at 157-58. This Court has c o n s i s

t e n t l y r e j e c t e d e f f o r t s t o t r e a t t h e

absence o f c l a s s w id e d i s c r i m i n a t i o n as i f

i t were an a f f i r m a t i v e de fe ns e t o a c la im

o f p a r t i c u l a r a c t s o f d i s c r i m i n a t i o n .

In C o n n e c t i c u t v . T e a l , 73 L . E d . 2 a 130

( 1 0 8 2 ) , the Court e x p l a i n e d :

[ p ] e t i t i o n e r s seek s imply t o j u s t i f y

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n aga in s t respondent on

the b a s i s o f t h e i r f a v o r a b l e t reatment

o f o t h e r members o f r e s p o n d e n t ' s

r a c i a l g r o u p . . . . I t i s c l e a r t h a t

C o n g r e s s n e v e r i n t e n d e d t o g i v e an

e m p l o y e r a l i c e n s e t o d i s c r i m i n a t e

ag a in s t some employees on the b a s i s o f

race or sex merely because he f a v o r

a b l y t r e a t s o t h e r members o f t h e

employees group.

73 L.Ed.2d at 141-42. Furnco C o n s t r u c t i o n

C o r £ . _v_.__W a t e r s , 438 U . S . 567 ( 1 9 7 8 ) ,

emphasized that " [a] r a c i a l l y ba lanced work

f o r c e c a n n o t immunize an e m p l o y e r f rom

l i a b i l i t y f o r s p e c i f i c a c t s o f d i s c r i m i n a

tion. 438 U.S. at 579.

45

The l o w e r c o u r t s h a v e r e p e a t e d l y

r e c o g n i z e d t h a t p r o o f t h a t t h e r e i s no

c l a s s w i d e d i s c r i m i n a t i o n does not pr ec lu d e

the p o s s i b i l i t y that there may have been

i n d i v i d u a l in s ta n c e s o f d i s c r i m i n a t i o n . In

D i c k e r s o n v . U n i t ed S t a t e s S t e e l Corpora-

t i o n , 582 F .2d 827 (3 r d C i r . 1 978 ) , the

employer advanced the same argument o f f e r e d

by r e s p o n d e n t h e r e , i n s i s t i n g t h a t the

d i s m i s s a l o f a c l a s s w i d e c l a i m b a r r e d

s u b s e q u e n t i n d i v i d u a l l a w s u i t s by c l a s s

members . The c o u r t o f a p p e a l s r e j e c t e d

that c o n t e n t i o n :

The c l a s s c la ims were not examined as

a mere a g g r e g a t i o n o f i n d i v i d u a l

c l a i m s . . . . R a t h e r , the d i s t r i c t

c o u r t l ooked t o s t a t i s t i c a l ev idence

o f f e r e d t o s u p p o r t the e x i s t e n c e o f

a p r a c t i c e or p a t t e r n o f d i s c r i m i n a

t i o n ____ The d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s f i n d i n g

o f an absence o f c l a s s - w i d e d i s c r i m i

na t i on i s not n e c e s s a r i l y i n c o n s i s t e n t

with a c la im that d i s c r e t e , i s o l a t e d

i n s t a n c e s o f d i s c r i m i n a t i o n o c c u r

r e d . . . . T h e r e f o r e , t h e c o u r t ' s

d e c i s i o n as to the c l a s s - w i d e c la ims

o f d i s c r i m i n a t i o n d o e s n o t , as a

46

m a t t e r o f r e s j u d i c a t a , b a r c l a s s

members f rom a s s e r t i n g i n d i v i d u a l

c l a i m s o f p e r s o n a l d i s c r i m i n a t i o n .

582 F.2d at 830-31 .

See a l s o Harr ison v . L e w is , 559 F. Supp.

943, 947 (D.D.C. 1983) ; Branham v. General

e l e c t r i c Co . , 63 F.R.D. 667 671-71 (M.D.

Tenn. 1 9 7 4 ) ; 18 C. Wr i ght & A. M i l l e r ,

Federal P r a c t i c e and P r o c e d u r e , § 4455, p p .

4 7 3 - 7 4 ( 1 9 8 2 ) . S e v e r a l c i r c u i t s h a ve

c o n s id e r e d or upheld c la ims o f i n d i v i d u a l

c l a s s members or r e p r e s e n t a t i v e s d e s p i t e

ho l d in g that the ev id enc e d id not suppor t a

H /

f i n d i n g o f c l a s s w i d e d i s c r i m i n a t i o n .

The d i s t i n c t i o n r e p e a t e d l y r e c o g n iz e d

by t h i s Cour t , and c o r r e c t l y a p p l i e d by the

d i s t r i c t c o u r t in t h i s c a s e , d o e s n o t

r e c r e a t e a s i t u a t i o n s i m i l i a r t o t h e

21/ S e e , e . g . , Muskel ly v . Warner & Swasey

C o . , 653 F.2d 112 (4th C i r . 1981) ; S tastny

v. Southern B e l l T e l . & T e l . Co . , 628 F.2d

267 (4th C i r . 1980) .

- 47

"one-way" i n t e r v e n t i o n which e x i s t e d p r i o r

t o the 1966 amendments t o Rule 23 . The

a c t u a l d e c i s i o n a t a s t a g e I p r o c e e d i n g

b inds the p l a i n t i f f c l a s s as we l l as the

d e f e n d a n t , and that d e c i s i o n has a s i m i l a r

impact on both p a r t i e s . I f the p l a i n t i f f s

p r e v a i l at s tage I o f a b i f u r c a t e d T i t l e

V I I h e a r i n g , the f i n d i n g o f a c l a s s w i d e

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n does not r e s u l t au tomat i c

a l l y in the e n t r y o f judgment f o r each

c l a s s member. Rather , that d e c i s i o n merely

c r e a t e s a r e b u t t a b l e presumpt ion, app l i ed

at the s tage I I remedy he a r i ng , that each

c l a s s member was the v i c t i m o f d i s c r i m i n a

t i o n . I n t e r n a t i o n a l Brotherhood o f Tearn-

s t e r s v_.__U n i t e d S t a t e s , 431 U . S . 3 2 4 ,

357-62 and nn. 45-46 (1 97 7 ) . The employer

remains f r e e t o attempt to overcome that

presumption and t o prove that any p a r t i c u

l a r c l a s s member was n o t such a v i c t i m .

Franks v . Bowman T r a n s p o r t a t i o n Co, 424

48

U . S . 7 4 7 , 773 and n . 32 ( 1 9 7 6 ) . C o n

v e r s e l y , a s tag e I f i n d i n g o f no c la s s w id e

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n has an un qu es t i onab le and

c o m p a r a b l e a d v e r s e e f f e c t on any c l a s s

member t h e r e a f t e r seeking t o l i t i g a t e an

i n d i v i d u a l c la im o f d i s c r i m i n a t i o n . Such a

c l a s s member would o r d i n a r i l y be barred by

c o l l a t e r a l e s t o p p e l from seeking t o suppor t

h i s o r her i n d i v i d u a l c l a i m by o f f e r i n g

p r o o f o f a gen era l p a t t e r n o r p r a c t i c e o f

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n . Branham v. General E l e c

t r i c Co . , 63 F.R.D. 667, 671-72 (M.D. Tenn.

1974) ; see pp. 63 -67 , i n f r a .

The o p i n i o n o f the c o u r t o f a p p e a l s

s u g g e s t s an a l t e r n a t i v e b a s i s f o r i t s

d e c i s i o n - - t h a t the B a x t e r p l a i n t i f f s ,

having u n s u c c e s s f u l l y sought t o have t h e i r

c la ims ad ju d i ca te d in the Cooper l i t i g a

t i o n , are not e n t i t l e d t o renew that e f f o r t

in another l a w s u i t . Such a r u le i s impl ied

by the f o l l o w i n g passage ;

49

The p l a i n t i f f s seek t o es cape the bar

c r e a t e d by the d e t e r m i n a t i o n in the

c l a s s a c t i o n s u i t by arguing that they

were prevented by the D i s t r i c t Court

in prov in g t h e i r i n d i v i d u a l c la ims in

the c l a s s a c t i o n t r i a l . This argument

would d i s r e g a r d the f a c t t h a t the

t r i a l was b i f u r c a t e d by agreement o f

the p a r t i e s . (P.A. 179a-180a) .

This argument seems to a s s e r t , and the bank

a p p e a r s t o a r g u e , t h a t i f t h e B a x t e r

p l a i n t i f f s " l o s t " in Cooper in the sense

that they merely f a i l e d i to o b t a i n a d e c i -

s i o n on t h e m e r i t s o f t h e i r c l a i m s ,

such a " l o s s " p r e c lu d e s any fu r t h e r attempt

to o b t a i n a j u d i c i a l de t er mi na t i on o f those

c l a i m s .

Such a r u l e would be c o m p l e t e l y at

odds with the long e s t a b l i s h e d p r i n c i p l e s

o f r e s j u d i c a t a , which p r e c lu d e l i t i g a t i o n

o f on ly those c la ims p r e v i o u s l y r e s o l v e d

" o n t h e m e r i t s " . Kremer v . C he mi c a l

C o n s t ru c t i o n C o r p . , 456 U.S. 461, 466 n. 6

( 1 9 8 2 ) ; Federated Department S t o r e s , I n c .

50

v. M o i t i e , 452 U.S. 394, 398 ( 1 981 ) . In

a d d i t i o n , such a r u l e would wreak ha voc

with the ad m i n i s t ra t i o n o f Rule 23. Every

c la s s member would be f o r c e d t o in ter ven e

to a s s u r e t h a t h i s o r he r c l a i m was not

f o r f e i t e d merely because a c o u r t f a i l e d to

d e c i d e i t . No c o m p e t e n t p l a i n t i f f ' s

c o u n s e l c o u l d e v e r a g a i n a g r e e t o t h e

b i f u r c a t i o n o f the t r i a l o f a c l a s s a c t i o n ,

s ince b i f u r c a t i o n would c a r ry with i t an

i n t o l e r a b l e r i s k that the c la ims o f c l a s s

members would be l o s t merely because they

were n o t r e s o l v e d . In l i g h t o f t h a t

danger , no c o n s c i e n t i o u s d i s t r i c t c o u r t ,

even at the u r g i n g o f d e f e n s e c o u n s e l ,

could ever o rd er b i f u r c a t i o n .

The de f a c t o a b o l i t i o n o f b i f u r c a t i o n

would impose an enormous a d m i n i s t r a t i v e

burden on the f e d e r a l c o u r t s . The p r o c e

dure e x p r e s s l y approved by t h i s Court in

F r _a n k s and T e a m s t e r s e v o l v e d , and has

51

ga ined widespread acceptance in T i t l e VII

c l a s s a c t i o n s , because i t g r e a t l y r educes

the t ime needed to t r y such c a s e s . As the

lower c o u r t s are we l l aware, the t r i a l o f

even a h a n d f u l o f i n d i v i d u a l c l a i m s o f

employment d i s c r i m i n a t i o n can be as time

consuming as a t r i a l t o determine whether

ther e i s a c la s s w id e p r a c t i c e o f d i s c r i m i -

n a t i o n a f f e c t i n g a n e n t i r e p 1 an t . I n

the in s ta n t c a s e , f o r example , the t r i a l

c o n s u m e d a t o t a l o f s i x d a y s ; o f t h i s

p e r i o d l e s s than two days o f t e s t imony

d e a l t with the c l a s s c l a i m, and over f ou r

days o f hear ings concerned the i n d i v i d u a l

c la ims o f the named p l a i n t i f f s and s e v e r a l

c l a s s members. Had each i n d i v i d u a l c la im

o f every c l a s s member been p r e s e n t e d , the

t r i a l would d o u b t l e s s have l a s t e d s e v e r a l

months r a t her than a few days . A s i m i l a r

e x p o n e n t i a l g rowth in the l e n g t h o f a l l

T i t l e VII t r i a l s would be p r e c i p i t a t e d by

52

a r u l e that the f a i l u r e o f a c o ur t t o f i nd

c l a s s w i d e a i s c r i ra m a t r o n a t a s t a g e I

hearing a u t o m a t i c a l l y pr ec lu d e s l i t i g a t i o n

o f a l l i n d i v i d u a l c la i m s .

I f such a r u l e was in f a c t app l i ed by

the c o u r t o f a p p e a l s in t h i s c a s e , the

n o t i c e a c t u a l l y sent t o c l a s s members was

f a t a l l y d e f i c i e n t . The n o t i c e a d v i s e d

c l a s s members

[T]he judgment in t h i s c as e , whether

f a v o r a b l e o r u n f a v o r a b l e . . . w i l l

in c l ud e a l l c l a s s members; a l l c l a s s

members w i l l be bound by the judgment

o r o t he r de t erminat i on o f t h i s a c t i o n .

(P . A . 36a)

The unambiguous meaning o f t h i s n o t i c e was

that the c la im o f a c l a s s member would be

l o s t on ly i f there were in f a c t a "de te rm i

na t i on " o f that c la i m , and i f that de termi

n a t i o n w e r e " u n f a v o r a b l e . " N o t h i n g

in the n o t i c e in any way suggested that a

c l a s s member w o u l d somehow be " b o u n d "

because the c our t d id not i ssue any " ju d g

53

ment o r o t h e r de te rm in at i o n " r egard ing h i s

o r her c la im.

The d e c i s i o n o f the c o u r t o f appeal s

t o d i sm is s the c la ims o f p e t i t i o n e r Ha rr i

son d id not r e s t on. the d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s

d i s p o s i t i o n o f t h e c l a i m o f c l a s s w i d e

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n i n g r a d e s 6 and a b o v e .

S ince Harr ison he ld o n l y a grade 3 p o s i

t i o n , the d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s d e c i s i o n r e ga r d

ing promot i ons out o f the h igher grades was

n o t c o n t r o l l i n g . N e i t h e r the d i s t r i c t

c o u r t ' s Memorandum o f D e c i s i o n , F ind ings o f

Fact and Co nc lus i ons o f Law, or Judgment

c o n t a in any r e f e r e n c e whatever to whether

o r not there was a pa t te r n o f d i s c r i m i n a

t i o n in p r o m o t i o n s o u t o f g r a d e 3. In

ho ld in g that H a r r i s o n ' s c la im was barred by

res j u d i c a t a , the c o u r t o f appeal s as s e r te d

t h a t t h a t c l a i m " i s p r e c l u d e d by o u r

de t er mi na t i on on t h i s appeal that there was

no p r a c t i c e o f d i s c r i m i n a t i o n in pay grade

54

5 and b e l o w . " (P.A. 179a) .

But the p h r a s e " i n pay g r a d e 5 and

b e l o w " masks a c r i t i c a l d i s t i n c t i o n

between the ac tu a l d e c i s i o n o f the Fourth

C i r c u i t and the nature o f H a r r i s o n ' s c la im.

The i s s ue in f a c t c o ns id e r ed and r e s o l v e d

by the c our t o f appeals was o n l y whether

the d i s t r i c t c o ur t erred in f i n d i n g d i s

c r i m i n a t i o n in p r o m o t i o n s f rom g r a d e s 4

and 5; the d i s t r i c t c o u r t made no f i n d i n g

a b o u t , and the c o u r t o f a p p e a l s had no

o c c a s i o n e v e n t o c o n s i d e r , p r o m o t i o n

p r a c t i c e s a f f e c t i n g b l a c k e m p l o y e e s in

g r a d e 3. I t i s c l e a r t h a t the c o u r t o f

appeal s we l l understood that the o n l y i ssue

o f c l a s s w i d e d i s c r i m i n a t i o n b e f o r e i t

i n v o l v e d g r a d e s 4 and 5 . In t w e l v e

d i f f e r e n t p a s s a g e s the c o u r t o f a p p e a l s

d e s c r i b e d the d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s f i n d i n g o f

c l a s s w i d e d i s c r i m i n a t i o n , in e v e r y c a s e

no t in g that that f i n d i n g concerned grades 4

55