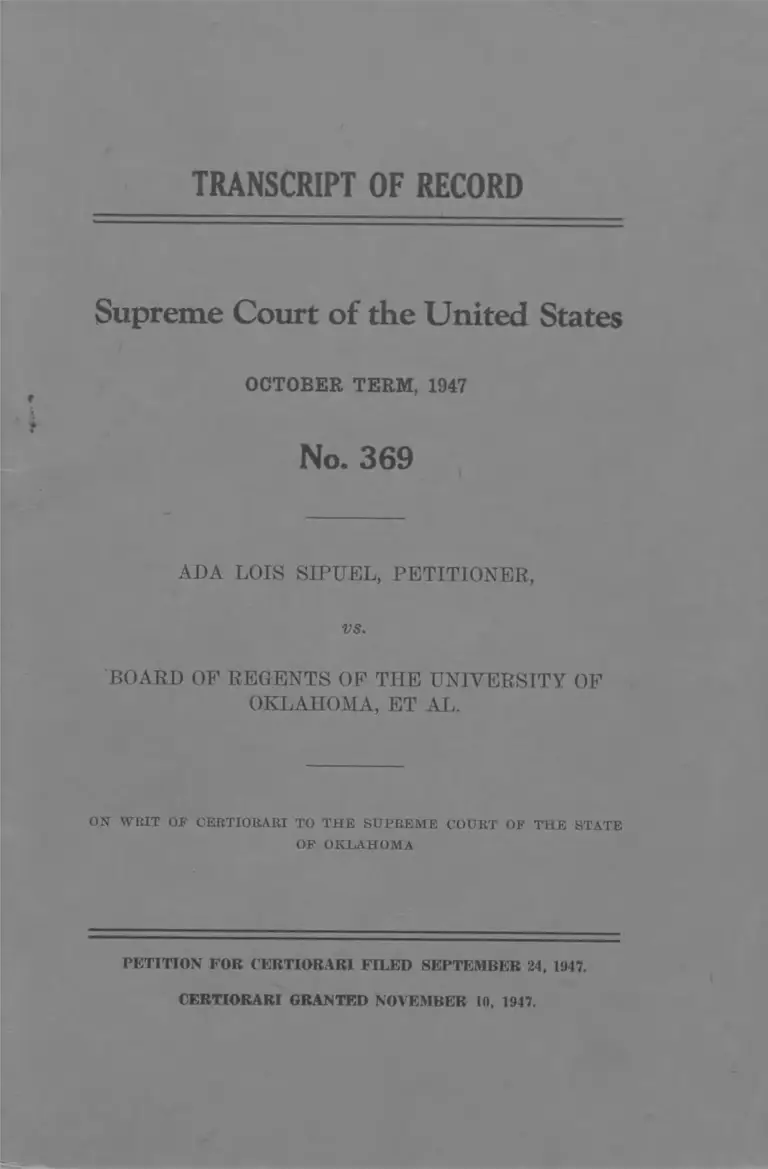

Sipuel v Board of Regents of UOK Transcript of Record

Public Court Documents

November 10, 1947

65 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sipuel v Board of Regents of UOK Transcript of Record, 1947. a7131c91-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8349cd0a-c736-400c-9caf-9fd7546c7dd4/sipuel-v-board-of-regents-of-uok-transcript-of-record. Accessed January 29, 2026.

Copied!

TRANSCRIPT OF RECORD

Supreme Court o f the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1947

No. 369

ADA LOIS SIPUEL, PETITIONER,

vs.

BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF

OKLAHOMA, ET AL.

ON WRIT or CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE

OF OKLAHOMA

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI FILED SEPTEMBER 24, 1947.

CERTIORARI GRANTED NOVEMBER 10, 1947.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

ADA LOIS SIPUEL, PETITIONER,

vs.

BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF

ON PETITION FOR WRIT OP CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OCTOBER TERM, 1947

No.

vs.

3GENTS OF THE UN

OKLAHOMA ET AL.

OP THE STATE OF OKLAHOMA

INDEX

Original Print

Proceedings in Supreme Court of Oklahoma........................... 2 1

Petition in error................................................................................. 2 . 1

Case-made from District Court of Cleveland County, Okla- 4

homa ................................................................................................. 4 2

Appearances ............................................................................... 4 2

Petition for writ of mandamus........................................... 7 2

Minute entry of issuance of alternative writ of

mandamus ............................................................................... 14 6

Alternative writ of mandamus............................................. 15 7

Application for time to prepare and file response. . . . 22 11

Minute entry re extension of time to respond................ 25 13

Order giving defendants additional time to prepare

and file response ................................................................. 25 13

Answer ........................................................................................ 27 13

Minute entries re setting ease for trial............................. 36 19

Minute entries re trial, etc....................................................... 37 19

Oral judgment of the Court.................................................. 39 21

Plaintiff’s Exhibit 1— Agreed statement of facts........... 41 22

Plaintiff’s Exhibit 2— Agreed statement of facts........... 46 24

J udd & Detweiler ( I nc. ) , Printers, W ashington, D.C., September 18,1947.

— 2514

11 INDEX

Case-made from District Court of Cleveland County, Okla

homa— Continued Original Print

Minute entry re denial of writ of mandamus................ 47 25

Motion for new trial................................................................. 48 25

Minute entry re denial of motion for new trial, etc.. . 49 26

Order overruling motion for new trial............................. 50 26

Minute entry re extension of time to make and serve

case-made .............................................................................. 52 27

Order extending time to make and serve ease-made. . 52 27

Journal entry ............................................................................ 55 28

Reporter’s certificate................. (omitted in printing).. 58

Clerk’s certificate...........................(omitted in printing). . 62

Service of case-made................................................................. 63 29

Certificate of attorneys to case-made.................................. 64 30

Stipulation of attorneys to case-made............................. 65 30

Certificate of trial judge to case-made............................. 66 31

Stipulation extending time to file brief...................................... 68 32

Motion for oral argument............................................................ 72 33

Motion to advance............................................................................ 74 34

Order assigning e a s e ........................... 76 35

Argument and submission ............................................................ 77 35

Opinion, Welch, J .............................................. 78 35

Order correcting ............................................................................... 100 51

Note re mandate .............................................................................. 101 52

Application for leave to file petition for rehearing and

order granting sam e..................................................................... 102 52

Order recalling mandate and extending time to file peti

tion for rehearing.......................................................................... 105 53

Petition for rehearing...................................................................... 106 54

Order denying petition for rehearing........................................... 117 61

Note re mandate ............................................................................... 118 61

Clerk’s certificate.................................... (omitted in printing). . 119

Order allowing certiorari.................................................................. 120 61

1

[fols. 1-2] [File endorsement omitted]

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF

OKLAHOMA

No. 32756

A da L ois Sipuel, Plaintiff in Error,

vs.

Boabd of Regents of the U niversity of Oklahoma, George

L. Cross, Maurice H. Merrill, George Wadsack and Roy

Gittinger, Defendants in Error

Petition in E rror— Filed Aug. 17, 1946

The said Ada Lois Sipuel, plaintiff in error, complains of

said defendants in error for that the said defendants in

error on the 9th day of July, 1946, in the District Court of

Cleveland County, Oklahoma, recovered a judgment, by the

consideration of said court, against the said plaintiff in

error, in a certain action then pending in the said court,

wherein the said Ada Lois Sipuel was plaintiff and the said

Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma, George

L. Cross, Maurice H. Merrill, George Wadsack and Roy

Gittinger were defendants.

[fol. 3] The original case-made, duly signed, attested, and

filed is hereunto attached, marked “ Exhibit A ,’ ’ and made

a part of this petition in error; and the said Ada Lois Sipuel

avers that there is error in the said record and proceedings,

in this, to w it:

(1) Error of the court in denying the petition of the

plaintiff for a writ of mandamus.

(2) Errors of law occurring at the trial which were ac

cepted to by the plaintiff.

Wherefore, plaintiff in error prays that the said judg

ment so rendered may be reversed, set aside, and held for

naught, and that a judgment may be rendered in favor of

the plaintiff in error and against the defendants in error,

upon the agreed statement of facts, and that the plaintiff

in error be granted the relief prayed for in her petition

and for such other relief as to the court may seem just.

Ada Lois Sipuel, by Amos T. Hall, Attorney for

Plaintiff in Error.

1— 2514

2

[fols. 4-6] In the District Court of Cleveland County,

State of Oklahoma

No. 14807

A da Lois Sipuel, Plaintiff,

vs.

B oard of Regents of the U niversity of Oklahoma, George

L. Cross, Maurice H. Merrill, George Wadsack and Roy

Gittinger, Defendants.

Case Made

A ppearances :

Amos T. Hall, Tulsa, Oklahoma; Thurgood Marshall, New

York, New York; and Robert L. Carter, New York, New

York, Attorneys for Plaintiff.

Mac Q. Williamson, Attorney General of Oklahoma; Fred

Hansen, First Assistant Attorney General of Oklahoma;

Dr. Maurice II. Merrill, Acting Dean of the School of Law,

University of Oklahoma; and Dr. John B. Cheadle, Profes

sor of Law, University of Oklahoma, Attorneys for De

fendants.

Hon. Ben T. Williams, District Judge.

Bob Hunter, Jr., Court Reporter.

[fol. 7] In the District Court of Cleveland County,

State of Oklahoma

[Title omitted]

[fol. 8] Petition for W rit of Mandamus— Filed April 6,

1946

Now comes the plaintiff, Ada Lois Sipuel, and for her

cause of action against the defendants and each of them

alleges and states:

1. That she is a resident and citizen of the United States

and of the State of Oklahoma, County of Grady, and city of

Chickasha. She desires to study law in the School of Law

of The University of Oklahoma, which is supported and

3

maintained by the taxpayers of the State of Oklahoma, for

the purpose of preparing herself to practice law in the State

of Oklahoma and for public service therein and has been

arbitrarily refused admission.

2. That on January 14, 1946, plaintiff duly applied for

admission to the first year class of the school of law of the

University of Oklahoma. She then possessed and still pos

sesses all the scholastic, moral and other lawful qualifica

tions prescribed by the Constitution and statutes of the

State of Oklahoma, by the Board of Regents of the Uni

versity of Oklahoma and by all duly authorized officers and

agents of the said University and the school of law for

admission into the first year class of the school of law of the

said University. She was then and still is ready and willing

to pay all lawful uniform fees and charges and to conform

to all lawful uniform rules and regulations established by

lawful authority for admission to the said class. Plaintiff’s

application was arbitrarily and illegally rejected pursuant

to a policy, custom or usage of denying to qualified Negro

applicants the equal protection of the laws solely on the

ground of her race and color.

[fol. 9] 3. That the school of law of the University of

Oklahoma is the only law school in the state maintained by

the state and under its control and is the only law school in

Oklahoma that plaintiff is qualified to attend. Plaintiff de

sires that she be admitted in the first year class of the school

of law of the University of Oklahoma at the next regular

registration period for admission to such class or at the

first regular registration period after this cause has been

heard and determined and upon her paying the requisite

uniform fees and conforming to the lawful uniform rules

and regulations for admission to such class.

4. That the defendant Board of Regents of the University

of Oklahoma is an administrative agency of the State and

exercises overall authority with reference to the regula

tion of instruction and admission of students in the Univer

sity, a corporation oi’ganized as a part of the educational

system of the state and maintained by appropriations from

the public funds of the State of Oklahoma. The defendant,

George L. Cross, is the duly appointed, qualified and acting

President of the said University and as such is subject to

the authority of the Board of Regents as an immediate

4

agent governing and controlling the several colleges and

schools of the said University. The defendant, Maurice

H. Merrill, is the Dean of the school of law of the said

University whose duties comprise the government of the

said law school including the admission and acceptance of

applicants eligible to enroll as students therein, including

your plaintiff. The defendant, Roy Gittinger, is the Dean

of admissions of the said University and the defendant

George Wadsack is the Registrar thereof, both possessing

[fol. 10] authority to pass upon the eligibility of applicants

who seek to enroll as students therein, including your

plaintiff. All of the personal defendants come under the

authority, supervision, control and act pursuant to the

orders and policies established by the defendant Board of

Regents of the University of Oklahoma. All defendants

herein are being sued in their official capacity.

5. That the school of law specializes in law and pro

cedure which regulates the courts of justice and govern

ment in Oklahoma and there is no other law school main

tained by the public funds of the state where plaintiff can

study Oklahoma law and procedure to the same extent and

on an equal level of scholarship and intensity as in the

school of law of the University of Oklahoma. The arbitrary

and illegal refusal of defendants Board of Regents, George

L. Cross, Maurice H. Merrill, George Wadsack and Roy

Gittinger, to admit plaintiff to the first year of the said

law school solely on the ground of race and color inflicts

upon your plaintiff an irreparable injury and will place

her at a distinct disadvantage at the bar of Oklahoma and

in the public service of the aforesaid state with persons

who have had the benefit of the unique preparation in Okla

homa law and procedure offered to white qualified appli

cants in the law school of the University of Oklahoma.

6. That the requirements for admission to the first year

class of the school of law are as follows: applicants must

be at least eighteen (18) years of age and must have gradu

ated from an accredited high school and completed two full

years of academic college work. In addition applicants

must have maintained at least one grade point for each

semester carried in college or two grade points during the

[fol. 11] last college year of not less than thirty semester

hours. Plaintiff is over eighteen (18) years of age, has

completed the full college course at Langston University, a

5

college maintained and operated by the State of Oklahoma

for the higher education of its Negro citizens. Plaintiff

maintained one grade point for each semester point car

ried and graduated from the above named college with

honors. She is of good moral character and has in all par

ticulars met the qualifications necessary for admittance to

the school of law of the University of Oklahoma which fact

defendants have admitted. She is ready, willing and able

to pay all lawful charges and tuition requisite to admission

to the first year of the school of law and she is otherwise

ready, willing and able to comply with all lawful rules and

regulations requisite for admission therein.

7. O January 14, 1946, plaintiff applied for admission

to the school of law of the University of Oklahoma and

complied with all the rules and regulations entitling her to

admission by filing with the proper officials of the University

an official transcript of her scholastic record, Said trans

cript was duly examined and inspected by the President,

Dean of the School of Law and Dean of Admissions and

Registrar of the University; defendants aforementioned,

and found to be an official transcript as aforesaid entitling

her to admission to the school of law of the University.

Plaintiff was denied admission to the school of law solely

on the ground of race and color in violation of the Constitu

tion and laws of the United States and of the State of

Oklahoma.

8. Defendants have established and are maintaining a

policy, custom and usage of denying to qualified Negro

[fol. 12] applicants the equal protection of the laws by

refusing to admit them into the law school of the University

of Oklahoma solely because of race and color and have con

tinued the policy of refusing to admit qualified Negro appli

cants into the said school while at the same time admitting

white applicants with less qualifications than Negro appli

cants solely on account of race and color.

9. The defendants, George L. Cross, Maurice H. Merrill,

George Wadsack and Roy Gittinger refuse to act upon

plaintiff’s application and although admitting that plaintiff

possesses all the qualifications necessary for admission to

the first year in the school of law, refused her admission

on the ground that the defendant Board of Regents had

established a policy that Negro qualified applicants were not

eligible for admission in the law school of the University of

6

Oklahoma solely because of race and color. Plaintiff ap

pealed directly to the Board of Regents for admission to

the first year class of the law school of said University

and such board has so far refused to act in the premises.

10. Plaintiff further shows that she has no speedy, ade

quate remedy at law and that unless a Writ of Mandamus

is issued she will be denied the right and privilege of pur

suing the course of instruction in the school of law as

hereinbefore set out.

Wherefore, plaintiff being otherwise remediless, prays

this Honorable Court to issue a Writ of Mandamus requir

ing and compelling said defendants to comply with their

statutory duty in the premises and admit the plaintiff in

the school of law of the said University of Oklahoma and

have such other and further relief as may be just and proper,

[fol. 13] (Signed) Amos T. Hall, 107% N. Green

wood Avenue, Tulsa, Oklahoma; Tliurgood Mar

shall, 20 West 40th Street, New York 18, N. Y .;

Robert L. Carter, 20 West 40th Sti’eet, New York,

18, N. Y., Attorneys for Plaintiff.

Duly sworn to by Ada Sipuel. Jurat omitted in printing.

[fol. 14] [File endorsement omitted]

I n District Court or Cleveland County

M inute E ntry of Issuance of A lternative W rit of

Mandamus

4-9-46— C /M : Alternative writ of Mandamus issued to

defendants to admit Plaintiff to Law School of University

of Oklahoma or appear April 26, 1946, at 10 o ’clock A.M.,

and show cause as per Alternative Writ of Mandamus.

Of the Records of Cleveland County, State of Oklahoma,

in District Court. Civil Appearance Docket No. 24, Page

272.

7

[fol. 15] In District Court of Cleveland County

[Title omitted]

A lternative W rit of Mandamus and Return—April 9,

1946

On this the 9th day of April, 1946, upon due and proper

application of the plaintiff showing the following facts,

to-wit:

%

1. That she is a resident and citizen of the United States

and of the State of Oklahoma, County of Grady, and city

of Chickasha. She desires to study law in the School of

Law of the University of Oklahoma, which is supported and

maintained by the taxpayers of the State of Oklahoma, for

the purpose of preparing herself to practice law in the

State of Oklahoma and for public service therein and has

been arbitrarily refused admission.

2. That on January 14, 1946, plaintiff duly applied for

admission to the first year class of the school of law of the

University of Oklahoma. She then possessed and still

possesses all the scholastic, moral and other lawful qualifica

tions prescribed by the Constitution and Statutes of the

State of Oklahoma and by all duly authorized officers and

agents of the said University and the school of law for ad

mission into the first year class of the school of law of the

[fol. 16] said University. She was then and still is ready

and willing to pay all lawful uniform fees and charges and

to conform to all lawful rules and regulations established

by lawful authority for admission to the said class. Plain

tiff’s application was arbitrarily and illegally rejected pur

suant to a policy, custom or usage of denying to qualified

Negro applicants the equal protection of the laws solely

on the ground of her race and color.

3. That the school of law of the University of Oklahoma

is the only law school in the state maintained by the State

and under its control and is the only law school in Oklahoma

that plaintiff is qualified to attend. Plaintiff desires that

she be admitted in the first year class of the school of law

of the University of Oklahoma at the next regular registra

tion period for admission to such class or at the first regular

registration period after this cause has been heard and de

termined and upon her paying the requisite uniform fees

2— 2514

8

and conforming to the lawful uniform rules and regulations

for admission to such class.

4. That the defendant Board of Regents of the University

of Oklahoma is an administrative agency of the State and

exercises overall authority with reference to the regulation

of instruction and admission of students in the University,

a corporation organized as a part of the educational

system of the State and maintained by appropriations

from the public funds of the State raised by taxation from

the citizens and taxpayers of the State of Oklahoma. The

defendant, George L. Cross, is the duly appointed, qualified

and acting President of the said University and as such is

subject to the Authority of the Board of Regents as an

immediate agent governing and controlling the several col

leges and schools of the said University. The defendant,

[fol. 17] Maurice H. Merrill, is the Dean of the school of

law of the said University whose duties comprise the govern

ment of the said law school including the admission and ac

ceptance of applicants eligible to enroll as students therein,

including your plaintiff. The defendant, Roy Gittinger, is

the Dean of Admissions of the said University and the

defendant George Wadsack is the Registrar thereof, both

possessing authority to pass upon the eligibility of appli

cants who seek to enroll as students therein, including your

plaintiff. All of the personal defendants come under the

authority, supervision, control and act pursuant to the

orders and policies established by the defendant Board of

Regents of the University of Oklahoma. All defendants

herein are being sued in their official capacity.

5. That the school of law specializes in law and procedure

which regulates the courts of justice and government in

Oklahoma and there is no other law school maintained by

the public funds of the state where plaintiff can study

Oklahoma law and procedure to the same extent and on an

equal level of scholarship and intensity as in the school of

law of the University of Oklahoma. The arbitrary and

illegal refusal of defendants Board of Regents, George L.

Cross, Maurice H. Merrill, George Wadsack and Roy Git

tinger, to admit plaintiff to the first year of the said

law school solely on the ground of race and color inflicts

upon plaintiff an irreparable injury and will place her at

a distinct disadvantage at the bar of Oklahoma and in public

service of the aforesaid state with persons who have had

9

the benefit of the unique preparation in Oklahoma law and

procedure offered to white qualified applicants in the law

school of the University of Oklahoma.

[fol. 18] 6. That the requirements for admission to the

first year class of the school of law are as follows: applicants

must be at least eighteen (18) years of age, and must have

graduated from an accredited high school and completed

two full years of academic college work. In addition appli

cants must have maintained at least one grade point for each

semester carrier — and graduated from the above named

college with honors. She is of good moral character and

has in all particulars met the qualifications necessary fox-

admittance to the school of law of the University of Okla

homa which fact defendants have admitted. She is ready,

willing and able to pay all lawful charges and tuition

requisite to admission to the first year of the school of law

and she is otherwise ready, willing and able to comply

with all lawful rules and regulations requisite for admission

therein.

7. On January 14, 1946, plaintiff applied for admission

to the school of law of the University of Oklahoma and

complied with all the rules and regulations entitling her to

admission by filing with the proper officials of the University

an official transcript of her scholastic record. Said trans-

ci-ipt was duly examined and inspected by the President,

Dean of the School of Law and Dean of Admissions and Re-

gistrar of the University; defendants aforementioned, and

found to be an official transcript as afoi-esaid entitling

her to admission to the school of law of the University.

Plaintiff was denied admission to the school of law solely

on the ground of race and color in violation of the Constitu

tion and laws of the United States and of the State of

Oklahoma.

[fol. 19] 8. Defendants have established and are main

taining a policy, custom, and usage of denying to qualified

Negro applicants the equal protection of the laws by refus

ing to admit them into the law school of the University of

Oklahoma solely because of race and color and have con

tinued the policy of refusing to admit qualified Negro appli

cants into the said school while at the same time admitting

white applicants with less qualifications than Negro appli

cants solely on account of race and color.

10

9. The defendants, George L. Cross, Maurice H. Merrill,

George Wadsack and Roy Gittinger refuse to act upon

plaintiff’s application and although admitting that plaintiff

possesses all the qualifications necessary for admission to

the first year in the school of law, refused her admission on

the ground that the defendant Board of Regents had estab

lished a policy that Negro qualified applicants were not

eligible for admission in the law school of the University

of Oklahoma solely because of race and color. Plaintiff ap

pealed directly to the Board of Regents for admission to

the first year class of the law school of said University and

such board has so far refused to act in the premises.

10. Plaintiff further shows that she has no speedy, ade

quate remedy at law and that unless a Writ of Mandamus

is issued she will be denied the right and privilege of pur

suing the course of instruction in the school of law as herein

before set out.

Therefore, the Court being fully advised in the premises

finds that an Alternative Write of Mandamus should be

issued herein.

It is therefore ordered, considered and adjudged that all

of the said defendants, Board of Regents of the University

[fol. 20] of Oklahoma, George L. Cross, Maurice H. Merrill,

and George Wadsack, each and all of them, are hereby com

manded that immediately after receipt of this writ, you

admit into the School of Law of the said University of Okla

homa, the said plaintiff, Ada Lois Sipuel, or that you and

each and all of you, the said defendants, appear before this

court at 10:00 o ’clock A.M., on the 26th day of April, 1946,

to show cause for your refusal so to do and that you then

and there return this writ together with all proceedings

thereof.

(Signed) Ben T. Williams, Judge of the District

Court.

Witness the signature of Honorable Ben T. Williams,

Judge of the said Court and seal affixed to the 9th day of

April, 1946.

(Signed) Dess Burke, Court Clerk. (Seal)

State op Oklahoma,

Cleveland County, ss :

I received this alternative Writ of Mandamus this 9th

day of April, 1946, and served the same on the persons

11

named therein as defendants on the date and in the manner

following to-wit: On the Board of Regents by serving Emil

R. Kraettli, he being the Secretary to the Board of Regents;

On George L. Cross, President of the University of Okla-

home; On Maurice H. Merrill, Dean of Law, University of

Oklahoma, and on Roy Gittinger, Dean of Admissions, Uni

versity of Oklahoma; on George Wadsack, Registrar, Uni

versity of Oklahoma, by delivering to each of the above

named individually and in their official capacity as above set

forth, personally, a full- true and correct copy of the fore

going alternative Writ of Mandamus on the 10th day of

April, 1946, in Norman, Cleveland County, Oklahoma.

[fob 21] Key Durkee, County Sheriff. By (Signed)

Geo. N. Jones, Deputy Sheriff.

Sheriff’s Fees

Serving Summons, first person.......................................$ .50

4 additional persons.......................................................... 1.00

5 copies of summons.......................................................... 1.25

Mileage: 10 Miles.............................................................. 1.00

Total ........................................................................$3.75

Endorsed on front as follows: Filed in District Court,

Cleveland County, Okla., Apr. 10, 1946. (Signed) Dess

Burke, County Clerk. C.J. 31, P. 4, 5, 6.

Endorsed on back as follows: Alternative Writ of Man

damus. Writ allowed this 9th day of April, 1946. (Signed)

Ben T. Williams, Judge of District Court.

[fol. 22] I n the District Court of Cleveland County,

State of Oklahoma

[Title omitted]

A pplication for T ime to Prepare and F ile Response—

Filed April 23, 1946

Comes now the above named defendants, and each of

them, and respectfully inform the court that on April 9,

12

1946, an alternative writ of mandamus was issued in the

above case in which defendants were commanded

‘ ‘ immediately after receipt of this writ, you admit into

the School of Law of the said University of Oklahoma,

the said plaintiff, Ada Lois Sipuel, or that you and

each and all of you, the said defendants, appear before

this court at 10:00 o ’clock A.M. on the 26th day of

April, 1946, to show cause for your refusal so to do and

that you then and there return this writ together with

all proceedings thereof. ’ ’

That by reason of the fact that it will be necessary for

the Attorney General of Oklahoma, as attorney for the

above named defendants, to consult with the Oklahoma

[fob 23] Board of Regents for Higher Education, as well

as the Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma,

together with the Governor of the State, on the important

questions raised by this litigation before preparing and

filing an answer or response to plaintiff’s petition and said

alternative writ of mandamus, it will be necessary for the

court to grant defendants twenty (20) days additional

time within which to prepare and file said answer or re

sponse.

That telegraphic notice of this application was given by

the Attorney General on April 20, 1946, to Mr. Amos O’.

Hall, one of the attorneys of record for the plaintiff herein,

who on the same date acknowledged by telegram to the

Attorney General that he had received said notice and that

“ in view of the circumstances set out in your message you

are advised that we offer no objection to the court granting

you twenty (20) days additional time * *

Wherefore, premises considered, the above named de

fendants and each of them, respectfully ask the court to

grant them twenty (20) days additional time within which to

prepare and file an answer or response to plaintiff’s peti

tion and alternative writ of mandamus in the above cause.

(Signed) Mac Q. Williamson, Attorney General of

Oklahoma; (Signed) Fred Hansen, First Assistant

Attorney General, Attorneys for Defendants.

[fol. 24] [File endorsement omitted.]

13

[fol. 25] In District Court of Cleveland County

Minute E ntry re Extension of T ime to Respondent

4-23-46— C /M : Defendants granted 20 days additional

time to respond to alternative writ as per order.

Of the Records of Cleveland County, State of Oklahoma,

in District Court. Civil Appearance Docket No. 24,

Page 272.

I n the District Court of Cleveland County, State of

Oklahoma

[Title omitted]

Order Giving Defendants A dditional T ime to Prepare

and F ile Response—April 23,1946

Now on this the 23rd day of April, 1946, the application

of defendants for twenty (20) days additional time within

which to prepare and file an answer or response to plaintiff’s

petition and alternative writ of mandamus in the above

cause came on to be heard, after due notice, in regular

[fol. 26] order; and the court having examined said appli

cation and the allegations set forth therein finds that said

application should be granted.

Wherefore, premises considered, it is ordered and de

creed by the court that defendants and each of them have

twenty (20) days additional time within which to prepare

and file their answer or response to plaintiff’s petition and

alternative writ of mandamus, to wit, until Thursday,

May 16, 1946, inclusive.

(Signed) Ben T. Williams, Judge.

[File endorsement omitted.]

[fol. 27] I n the District Court of Cleveland County,

State of Oklahoma

[Title omitted]

A nswer— Filed May 14, 1946

Comes now the above-named defendants, and each of

them, and in answer to the petition of plaintiff and the

14

alternative writ of mandamus issued herein, allege and

state:

[fol. 28] 1. That the material allegations of fact set forth

in plaintiff’s petition and in said alternative writ of man

damus are not sufficient to constitute a cause of action in

favor of plaintiff and against defendants, or either of them.

2. That defendants, and each of them, deny the material

allegations of fact set forth in Paragraphs 1 to 10, inclu

sive, of plaintiff’s petition and in said alternative writ of

mandamus (said paragraphs being identical in said petition

and writ both as to number and phraseology), except such

allegations as are hereinafter alleged or admitted.

3. Defendants admit the material allegations of fact set

forth in Paragraph 1 of said petition and writ, except the

allegation that plaintiff was “ arbitrarily refused admis

sion’ ’ to the School of Law of the University of Oklahoma.

4. Defendants admit the material allegations of fact set

forth in Paragraph 2 of said petition and writ, except the

allegation that plaintiff possessed all “ other lawful quali

fications’ ’ for admission to the first year class of the School

of Law of the University of Oklahoma, and the allegation

that plaintiff’s application for admission to said class was

“ arbitrarily and illegally rejected.”

5. Defendants admit the material allegations of fact set

forth in Paragraph 3 of said petition and writ, except the

allegation which implies that plaintiff is “ qualified to at

tend” the School of Law of the University of Oklahoma.

6. Defendants admit the material allegations of fact set

forth in Paragraph 4 of said petition and writ.

7. Defendants admit the material allegations of fact set

forth in Paragraph 5 of said petition and writ, except the

[fol. 29] allegation which implies that the refusal of de

fendants to admit plaintiff to the first year class of the

School of Law of the University of Oklahoma was an “ arbi

trary and illegal refusal.”

8. Defendants admit the material allegations of fact set

forth in Paragraph 6 of said petition and writ, except the

allegation that plaintiff has “ in all particulars met the

qualifications necessary for admittance to the School of

Law of the University of Oklahoma which fact defendants

15

have admitted,” and in this connection allege that while

plaintiff is ‘ ‘ scholastically qualified for admission to the

Law School of the University of Oklahoma” (which fact

has been admitted by defendant), she does not have the

qualifications necessary for admittance at said school for

the reason that under the constitutional and statutory pro

visions of this State, hereinafter cited and reviewed (Para

graphs 14 to 21 hereof), only white persons are eligible for

admission to said school.

9. Defendants admit the material allegations of fact set

forth in Paragraph 7 of said petition and writ, but deny the

conclusion of law therein that the refusal of defendants to

admit plaintiff to the School of Law of the University of

Oklahoma on the ground of race and color was “ in viola

tion of the Constitution and laws of the United States and

of the State of Oklahoma.”

10. Defendants admit the material allegations of fact set

forth in Paragraph 8 of said petition and writ, but deny the

conclusion of law therein that the “ policy, custom and

usage” of defendants in refusing to admit negro applicants,

otherwise qualified, to the School of Law of the University

[fol. 30] of Oklahoma while continuing to admit white appli

cants, otherwise qualified, is a denial to said negro appli

cants of “ the equal protection of the laws.”

11. Defendants admit the material allegations of fact set

forth in Paragraph 9 of said petition and writ, except the

allegation which implies that the defendants, George L.

Cross, Maurice H. Merrill, Geoi'ge Wadsack and Roy Git-

tinger, have admitted that plaintiff “ possesses all the

qualifications necessary for admission to the first year in

the school of law” of the University of Oklahoma, and the

allegation which implies that plaintiff was denied admission

by defendants to said school solely “ on the ground that the

defendant, Board of Regents, had established a policy that

negro qualified applicants were not eligible for admission

in the law school of the University of Oklahoma solely

because of race and color,” and in this connection allege

that plaintiff was denied admission by said defendants to

said school not only by virtue of said policy, but by reason

of the constitutional and statutory provisions of the State

of Oklahoma, hereinafter cited and reviewed (Paragraphs

14 to 21 hereof).

3— 2514

16

12. Defendants deny the conclusions of law set forth in

Paragraph 10 of said petition and writ.

13. Defendants, and each of them, allege and admit that

the plaintiff, Ada Lois Sipuel, a colored or negro citizen and

resident of the United States of America and the State of

Oklahoma, duly and timely applied on January 14, 1946,

for admission to the first year class of the School of Law

of the University of Oklahoma for the semester beginning

January 15, 1946, and that she then possessed and still

[fol. 31] possesses all the scholastic and moral qualifica

tions required for such admission by the constitution and

statutes of this State and by the Board of Regents of the

University of Oklahoma, but deny that she was then pos

sessed and still possesses all “ other qualifications” re

quired by said constitution, statutes and board, for the

reason that under the public policy of this State announced

in the constitutional and statutory provisions hereinafter

cited and reviewed (Paragraphs 14 to 21 hereof), colored

persons are not eligible for admission to State school estab

lished for white persons, such as the School of Law of the

University of Oklahoma.

14. That Section 3, Article 13 of the Constitution of

Oklahoma provides, in part, that:

“ Separate Schools for white and colored children

with like accommodation shall be provided by the

Legislature and impartially maintained.”

15. That 70 0. S. 1941 § 363 provides in part that:

“ All teachers of the negro race shall attend separate

institutes from those for teachers of the white

race, * * *.”

16. That 70 0. S. 1941 § 455 makes it a misdemeanor,

punishable by a fine of not less than $100.00 nor more than

$500.00, for

“ Any person, corporation or association of persons

to maintain or operate any college, school or institu

tion of this State where persons of both white and

colored races are received as pupils for instruction,”

and provides that each day same is so maintained or

operated “ shall be deemed a separate offense.”

17

[fol. 32] 17. That 70 0. S. 1941 § 456 makes it a misde

meanor, punishable by a fine of not less than $10.00 no- more

than $50.00, for any instructor to teach

“ in any school, college or institution where members

of the white race and colored race are received and en

rolled as pupils for instruction,”

and provides that each day such an instructor shall continue

to so teach “ shall be considered a separate offense.”

18. That 70 O. S. 1941 § 457 makes it a misdemeanor, pun

ishable by a fine of not less than $5.00 nor more than $20.00,

for

“ any white person to attend any school, college or

institution, where colored persons are received as

pupils for instruction,”

and provides that each day such a person so attends “ shall

• be deemed a distinct and separate offense.”

19. That 70 O. S. 1941 § § 1591, 1592 and 1503, in effect,

provide that if a colored or negro resident of the State of

Oklahoma who is morally and educationally qualified to

take a course of instruction in a subject taught only in a

State institution of higher learning established for white

persons, the State will furnish him like educational facili

ties in comparable schools of other States wherein said

subject is taught and in which said colored or negro resi

dent is eligible to attend.

20. That the material part of Senate Bill No. 9 of the

Twentieth Oklahoma Legislature (same being the general

departmental appropriation bill for the fiscal years ending

June 30, 1946 and June 30, 1947), which was enacted to

finance the provisions of 70 O. S. 1941 § § 1591, 1592 and

1593, supra, is as follows:

[fol. 33] State B oabd of E ducation

Fiscal Year Fiscal Year

ending ending

June 30,1946 June 30,1947

“For payment of Tuition Fees and transpor

tation for certain persons attending insti-

tions outside the State of Oklahoma as

provided by law ............................................... $15,000.00 $15,000.00.”

18

21. That 70 0. S. 1941 §§ 1451 to 1509, as amended in

1945, established a State institution of higher learning now

known as “ Langston University” for “ male and female

colored persons” only, which institution, however, does not

have a school of law.

22. That the constitutional and statutory provisions of

Oklahoma, heretofore cited and reviewed (Paragraphs 14

to 21 hereof), have been uniformly construed by defendants

and their predecessors as prohibiting the admission of

persons of the colored or negro race to the School of Law

of the University of Oklahoma, and pursuant to such inter

pretation it has been their administrative practice to admit

only white persons, otherwise qualified, to said school.

23. That petitioner has not applied, nor in her petition

and/or alternative writ of mandamus alleged that she has

applied, to the Board of Regents of Higher Education of

this State for it, under authority of Article 13a of the Con

stitution of Oklahoma, to prescribe a school of law similar t

to the school of law of the University of Oklahoma as a part

of the standards of higher education of Langston Univer

sity, and as one of the courses of study, thereof, so that

she will be able as a negro citizen of the United States and

[fol. 34] the State of Oklahoma to attend said school without

violating the public policy of said State as evidenced by

the constitutional and statutory provisions of Oklahoma

heretofore cited and reviewed (Paragraphs 14 to 21 here

of).

24. That by reason of the foregoing constitutional and

statutory provisions and administrative interpretation and

practice, it cannot properly be said that “ the law specifically

enjoins” upon defendants, or either thereof (within the

meaning of 12 0. S. 1941 §§1451 to 1462, inclusive, relating

to “ Mandamus” ), the duty of admitting plaintiff to the

School of Law of the University of Oklahoma.

Wherefore, premises considered, defendants, and each

of them, respectfully ask the court to decline to issue the

writ of mandamus prayed for in this cause, that plaintiff

take nothing by her petition, and that defendants recover

their cost herein expended.

Mac Q. Williamson, Attorney General of Oklahoma.

(Signed) Fred Hansen, First Assistant Attorney

General, Attorneys for Defendants.

19

Duly sworn to by George L. Cross. Jurat omitted in print

ing.

[fol. 35] [File endorsement omitted.]

[fol. 36] I n Disteict Court of Cleveland County

M inute E ntries be Setting Case for T rial

5-21-46— C /M : Cause set for trial Friday, May 31, 1946,

at 10:00 o ’clock A. M., by agreement and clerk ordered to

notify counsel.

Of the Records of Cleveland County, State of Oklahoma,

in District Court. Civil Appearance Docket No. 24, Page

272.

Thereafter, and under date of May 31st, 1946, the Clerk

of the District Court entered herein a Minute, same appear

ing in words and figures as follows, to-wit:

5- 31-46— C/M : Cause continued at request of plaintiff’s

counsel to be reset by agreement.

Of the Records of Cleveland County, State of Oklahoma,

in District Court. Civil Appearance Docket No. 24, Page

272.

Thereafter, and under date of June lltli, 1946, the Clerk

of the District Court entered herein a Minute, same appear

ing in words and figures as follows, to-wit:

6- 11-46— C /M : Cause set for trial by agreement of coun

sel for Tuesday, July 9, 1946, at 10:00 o ’clock A. M.

Of the Records of Cleveland County, City of Oklahoma,

in District Court. Civil Appearance Docket No. 24, Page

272.

[fol. 37] I n District Court of Cleveland County

M inute E ntries re Trial, etc.

Now on this the 9tli day of July, 1946, the above styled

and numbered cause came regularly on for trial before the

20

Honorable Ben T. Williams, District Judge in and for the

Twenty-First Judicial District, State of Oklahoma, upon

plaintiff’s petition for a Writ of Mandamus filed herein.

The plaintiff, Ada Louis Sipuel, appeared in person

and by counsel, Amos T. Hall; and the defendants, Board

of Regents of the University of Oklahoma, et ah, appeared

by counsel, Fred Hansen, First Assistant Attorney General

of Oklahoma, and Dr. Maurice H. Merrill, Acting Dean of

the School of Law, University of Oklahoma, and both par

ties announced ready for trial.

AVhereupon, the following proceedings were had and

entered herein, to-wit:

Thereupon, Mr. Hall, Counsel for Plaintiff, offered into

evidence Plaintiff’s Exhibit “ 1” , being a written stipulation

of facts, signed by counsel, and there being no objections,

the Court ordered same marked Plaintiff’s Exhibit “ 1” and

introduced in evidence.

Thereupon, Mr. Hall, Counsel for Plaintiff, offered into

evidence Plaintiff’s Exhibit “ 2,” being a written stipula

tion of facts, and there being no objections, the Court or

dered same marked Plaintiff’s Exhibit “ 2” and introduced

in evidence.

And Thereupon the Plaintiff rested and the Defendants

rested.

Whereupon, there being no further evidence or testimony

in this case, Mr. Hall, of Counsel for Plaintiff, made the

opening argument on behalf of plaintiff; Mr. Hansen and

Dr. Merrill, of Counsel for Defendants, made the argument

on behalf of the defendants; and Mr. Hall made the closing

argument to the Court on behalf of the plaintiff.

[fol. 38] Thereafter, and at the conclusion of the argu

ment in this case the following remarks were made by the

Court and Counsel for Plaintiff, to-wit:

By the Court: Let the record show that at the conclusion

of the argument in this case the Court suggests to Mr. Hall

that while the Court is not suggesting that Mr. Hall’s re

marks might be improper in any way, still the law, in the

Court’s estimation, presumes that all Courts have the cour

age to do their duty and certifies to the record that to the

best of his understanding and ability that this Court feels

that he has the courage to do his duty in this or any other

judicial proceeding.

21

By Mr. Hall, of Counsel for plaintiff: I f the Court please,

I do not mean to imply that this Court hasn’t the courage

to do his duty. In cases of this kind it does require courage,

but I feel sure that if your honor holds and finds and renders

judgment against us that would not indicate to me at all

that you do not have the courage. I didn’t mean that this

Court doesn’t have the courage, but all courts must have

the courage to give the the colored people their rights. They

have been to the Legislature and to the Board of Regents

and haven’t received their rights, and the courts are the

last resort. I realize that we have dropped a hot potato

in the court’s lap, and whatever the judgment is, we know

it will be the court’s honest decision and judgment. I am

sorry that the Court misunderstood me as I had no inten

tion of inferring that your Honor didn’t have the courage

to render a just decision in this case.

[fol. 39] Thereupon, the Court ordered the hearing in this

cause recessed to the hour of 7 :30 P. M., this date.

And Thereafter, at the hour of 7 :45 P. M. the Court

reconvened and the Court made and entered herein the

following judgment, to-wit:

In District Court of Cleveland County

Oral Judgment of the Court

By the Court: Gentlemen, the Court adopts the view ad

vanced by Mr. Hansen in his argument wherein, among other

things, we find this quotation from a Kansas case (Sharp

less vs. Buckles, 70 Pac. 886):

“ Mandamus will not lie to require a county canvass

ing board to recanvass returns and exclude from the

count certain votes because cast and returned under a

law that is claimed to be unconstitutional, since the

determination of such question is not a duty imposed

upon the board, nor within its power.”

And the quotation found in an Indiana case (State ex rel.

Hunter vs. Winterrowd (Ind.), 92 N. E. 650):

“ It is quite a different thing to hold that such an

officer must at his peril disobey the specific commands

of a law duly enacted and promulgated, at the behest

22

of any one who may be of the opinion that such law is

unconstitutional. The proper function of mandamus

is to enforce obedience to law, and not disobedience,

or even to litigate its validity.”

And also the quotation found in a Connecticut case (Com-

ley vs. Boyle, 162 A. 26):

[fol. 40] “ The court properly refused to consider con

stitutionality of ordinance. Court in such case properly

refused to consider the constitutionality of the ordi

nance, whether such conclusion be based upon the trial

court’s valid exercise of its discretion in refusing the

building permit or upon the broader ground that it was

not the province of that court to pass upon the ques

tion.”

The Court heard with interest the argument of Dr. Mer

rill, but does not pass either pro or con upon the validity

of such argument.

The application for mandamus is denied and exceptions

allowed.

[fol. 41] In the District Court of Cleveland County,

State of Oklahoma

[Title omitted]

Plaintiff’s E xhibit “ 1 ” A greed Statement of F acts

1. That the plaintiff is a resident and citizen of the United

States and of the State of Oklahoma, County of Grady and

City of Chickasha; that she desires to study law in the

School of Law in the University of Oklahoma for the pur

pose of preparing herself to practice law in the State of

Oklahoma.

2. That the School of Law of the University of Oklahoma

is the only Law School in the State maintained by the State

and under its control.

3. That the Board of Regents of the University of Okla

homa is an administrative agency of the State and exer

cising overall authority with reference to the regulation

of instruction and admission of students in the University ;

23

that the University is a part of the educational system of

the State and is maintained by appropriations from the

public funds of the State raised by taxation from the citizens

[fol. 42] and taxpayers of the State of Oklahoma; that the

School of Law of Oklahoma University specializes in law

and procedure which regulates the Court of Justice and

Government in Oklahoma; that there is no other law school

maintained by the public funds of the State where the plain

tiff can study Oklahoma law and procedure to the same

extent and on an equal level of scholarship and intensity

as in the School of Law of the University of Oklahoma;

that the plaintiff will be placed at a distinct disadvantage at

the bar of Oklahoma and in the public service of the afore

said State with persons who have had the benefit of the

unique preparation in Oklahoma law and procedure offered

to white qualified applicants in the School of Law of the

University of Oklahoma, unless she is permitted to attend

the School of Law of the University of Oklahoma.

4. That the plaintiff has completed the full college course

at Langston University, a college maintained and operated

by the State of Oklahoma for the higher education of its

Negro citizens.

5. That the plaintiff duly and timely applied for admis

sion to the first year class of the School of Law of the

University of Oklahoma on January 14, 1946, for the

semester beginning January 15, 1946 and that she then

possessed and still possesses all the scholastic and moral

qualifications required for such admission.

6. That on January 14, 1946, when plaintiff applied for

admission to the said school of law, she complied with all

[fol. 43] of the rules and regulations entitling her to ad

mission by filing with the proper officials of the University,

an official transcript of her scholastic record; that said

transcript was duly examined and inspected by the Presi

dent, Dean of Admissions and Registrar of the University

and was found to be an official transcript, as aforesaid,

entitling her to admission to the School of Law of the said

University.

7. That under the public policy of the State of Oklahoma,

as evidenced by the constitutional and statutory provisions

referred to in defendants’ answer herein, plaintiff was

4—2514

24

denied admission to the School of Law of the University of

Oklahoma solely because of her race and color.

8. That the plaintiff at the time she applied for admission

to the said law school of the University of Oklahoma was

and is now ready and willing to pay all of the lawful charges,

fees and tuitions required by the rules and regulations of

the said University.

9. That plaintiff has not applied to the Board of Regents

of Higher Education of the State of Oklahoma for it, under

authority of Article 13-A of the Constitution of Oklahoma,

to prescribe a School of Law similar to the School of Law

of the University of Oklahoma as a part of the standards

of higher education of Langston University, and as one of

the courses of study thereof.

Dated this 8th day of July, 1946.

[fols. 44-45] (Signed) Amos T. Hall, 107^2 North

Greenwood Ave., Tulsa, Oklahoma; Tliurgood Mar

shall, 20 West 40th Street, New York 18, New York;

Robert L. Carter, 20 West 40th Street, New York

18, New York, Attorneys for Plaintiff.

(Signed) Mac Q. Williamson, Attorney General of

Oklahoma; (Signed) Fred Hansen, First Assistant

Attorney General; Maurice H. Merrill, Attorneys

for Defendants.

[fol. 46] In District Court op Cleveland County

Plaintiff’s E xhibit “ 2 ” — A greed Statement of F acts

It is hereby stipulated and agreed by and between counsel

for plaintiff and defendants that the court may consider the

following as an admitted fact:

That after the filing of this cause the Board of Regents

of Higher Education, having knowledge thereof, met and

considered the questions involved therein; that it had no

unallocated funds in its hands or under its control at that

time with which to open up and operate a law school and

has since made no allocation for that purpose; that in

order to open up and operate a law school for negroes in

this state, it will be necessary for the board to either with

draw existing allocations, procure moneys, if the law per

25

mits, from the Governor’s contingent fund, or make an

application to the next Oklahoma legislature for funds

sufficient to not only support the present institutions of

higher education but to open up and operate said law school;

and that the Board has never included in the budget which

it submits to the Legislature an item covering the opening

up and operation of a law school in the State for negroes

and has never been requested to do so.

[fol. 47] In District Court of Cleveland County

Minute E ntry R e Denial of W rit of Mandamus

7-9-46— C /M : Evidence submitted by written stipulation,

argument heard. Peremptory Writ of Mandamus denied as

per Journal Entry.

Of the Records of Cleveland County, State of Oklahoma,

in District Court. Civil Appearance Docket No. 24, Page

272.

[fol. 48] In the District Court of Cleveland County,

State of Oklahoma

[Title omitted]

Motion for New Trial—Filed July 11, 1946

Comes now the plaintiff and moves the Court to vacate

the judgment rendered in this cause on the 9th day of

July, 1946, and to grant a new trial herein for the reasons

hereinafter set out which materially affect the substantial

rights of the Plaintiff:

(1) Error of the Court in denying the petition of the

plaintiff for a writ of mandamus.

(2) Errors of law occurring at the trial which were ex

cepted to by the plaintiff.

Wherefore, plaintiff prays the Court to vacate, set aside

and hold naught the judgment heretofore rendered in this

cause and to grant a new trial herein.

(Signed) Amos T. Hall, Attorney for Plaintiff.

[File endorsement omitted.]

[fol. 49] I n District Court of Cleveland County

Minute E ntry re Denial of Motion for New T rial, etc.

7-12-46— C /M : Motion for new trial comes on by agree

ment of the parties, is considered and overruled and excep

tions allowed. Plaintiff gives notice in open Court of her

intentions to appeal to the Supreme Court of the State of

Oklahoma and asks that such intentions be noted upon the

Minutes, Dockets and Journals of the Court, and it is so

ordered and done. Plaintiff, praying an appeal but no ex

tension of time, is granted 15 days to make and serve case-

made defendants to have 3 days thereafter to suggest

amendments, same to be settled and signed upon 3 days

notice in writing by either party.

Of the Records of Cleveland County, State of Oklahoma,

in District Court. Civil Appearance Docket No. 24, Page

273.

26

[fol. 50] In the District Court of Cleveland County,

State of Oklahoma

[Title omitted]

Order Overruling M otion for New Trial— July 24, 1946

Now on this 12th day of July, 1946, there comes on before

me, by agreement of the parties, the hearing on the plain

tiff’s motion for new trial in the above entitled cause. Upon

consideration of the same, the court is of the opinion that

the motion should be overruled.

It is, therefore, ordered, adjudged, and decreed that

the motion for new trial filed by the plaintiff herein be, and

the same is, hereby overruled, to which the plaintiff excepts

and which exception is allowed.

[fol. 51] Thereupon, plaintiff gives notice in open court

of her intentions to appeal to the Supreme Court of the

State of Oklahoma and asks that such intentions be noted

upon the minutes, dockets, and journals of the court, and it

is so ordered and done.

Plaintiff, praying an appeal, but no extension of time, is

granted fifteen (15) days to make and serve case-made, the

defendants to have three (3) days thereafter to suggest

27

amendments and the same to be settled and signed upon

three (3) days notice in writing by either party.

(Signed) Ben T. Williams, District Judge.

[File endorsement omitted.]

[fob 52] I n District Court of Cleveland County

Minute E ntry re E xtension of T ime to Make and Serve

Case-Made

7-24-46— C/M : Plaintiff granted extension of 15 days to

make and serve case-made, defendants to have 3 days there

after to suggest amendments, same to be settled and signed

upon 3 days notice in writing by either party.

Of the Records of Cleveland County, State of Oklahoma,

in District Court. Civil Appearance Docket No. 24, Page

273.

I n the District Court of Cleveland County, State of

Oklahoma

[Title omitted]

Order E xtending T ime to Make and Serve Case-Made—

August 2, 1946

[fols. 53-54] Now on this the 24th day of July, 1946, the

above styled and numbered cause came regularly on for

hearing upon the oral application of the Plaintiff for an

extension of time within which to prepare and serve the

case-made herein, and it being shown to this Court that the

Plaintiff has not had sufficient time under the prior order

of this Court within which to prepare and serve the case-

made in this case because the Court Reporter has been busy

in actual court room work and work on case-mades ordered

prior to the time the case-made herein was ordered, and has

not had sufficient time to complete this case-made, this Court

finds that an extension of time should be granted herein.

It is therefore hereby ordered, upon good cause being

shown, that the plaintiff be, and he is hereby allowed fifteen

(15) days time, in addition to the time heretofore allowed

by prior order of this Court, within which to prepare and

28

serve the case-made in this case, and the defendants are al

lowed three (3) days thereafter within which to suggest

amendments to said case-made, and said case-made to be

signed and settled upon three (3) days written notice by

either party.

(Signed) Ben T. Williams, District Judge.

[File endorsement omitted.]

[fol. 55] In the District Court of Cleveland County,

State of Oklahoma

No. 14,807

A da L ois Sipuel, Plaintiff,

vs.

B oard of Regents of the U niversity of Oklahoma, et al.,

Defendants

Journal E ntry— August 6,1946

This cause coming on to be heard on this the 9th day of

July, 1946, pursuant to regular assignment for trial, the

said plaintiff being present by her attorney, Amos T. Hall,

and the said defendants by their attorneys, Fred Hansen,

First Assistant Attorney General, and Maurice H. Merrill;

and both parties announcing ready for trial and a jury

being waived in open court, the court proceeded to hear the

evidence in said case and the argument of counsel, said

evidence being presented in the form of a signed “ Agreed

Statement of Facts” and a supplemental agreed statement

of facts.

And the court, being fully advised, on consideration finds

that the allegations of plaintiff’s petition are not supported

by the evidence and the law, and the judgment is, therefore,

rendered for the defendants, and it is adjudged that the de

fendants go hence without day and that they recover their

[fols. 56-57] costs from the plaintiff; to which findings and

judgment plaintiff then and there excepted, and thereupon

gave notice in open court of her intention to appeal to the

Supreme Court of the State of Oklahoma, and asked that

such intentions be noted upon the minutes, dockets and

29

journals of the Court and it is so ordered and done, and

plaintiff praying an appeal is granted an extension of 15

days in addition to the time allowed by Statute to make and

serve case-made, defendants to have 3 days thereafter to

suggest amendments thereto, same to be settled and signed

upon 3 days notice in writing by either party.

(Signed) Ben T. Williams, District Judge.

O.K. (Signed) Fred Hansen, First Assistant Attorney

General; Amos T. Hall, by F. H.

[File endorsement omitted.]

[fols. 58-61] Reporter’s Certificate to foregoing transcript

omitted in printing.

[fol. 62] Clerk’s Certificate to foregoing transcript omit

ted in printing.

[fol. 63] In the District Court of Cleveland County,

State of Oklahoma

[Title omitted]

Service of Case-M ade

To the Above Named Defendants and Their Attorneys of

Record:

The above and foregoing case-made is hereby tendered

to and served upon you and each of you, as a true and

correct case-made in the above entitled cause, and as a

true and correct statement and complete transcript of all

the pleadings, motions, orders, evidence, findings, judg

ment and proceedings in the above entitled cause.

Dated this the 7th day of August, 1946.

Amos T. Hall, Attorneys for Plaintiff.

30

Acknowledgment of Service

I do hereby accept and acknowledge service of the above

and foregoing case-made, this the 7th day of August, 1946.

Mac Q. Williamson, Atty. Gen. of Okla; Fred Hansen,

1st Asst. Atty. Gen. of Okla.; Maurice H. Merrill,

Attorneys for Defendants.

[fol. 64] In the District Court of Cleveland County,

State of Oklahoma

[Title omitted]

Certificate of A ttorneys to Case-Made

We hereby certify that the foregoing case-made contains

a full, true, correct and complete copy and transcript of all

the proceedings in said cause, including all pleadings filed

and proceedings had, all the evidence offered or introduced

by both parties, all orders and rulings made and exceptions

allowed, and all of the record upon which the judgment in

said cause were made and entered, and that the same is a

full, true, correct and complete case-made.

Witness our hands this 10th day of Aug., 1946. Amos

T. Hall, Attorneys for Plaintiff.

[fol. 65] In the District Court of Cleveland County,

State of Oklahoma

[Title omitted]

Stipulation of A ttorneys to Case-Made

It is hereby stipulated and agreed by and between the

parties hereto that the foregoing case-made contains a

full, true, correct and complete copy and transcript of all

the proceedings in said cause, all pleadings filed and pro

ceedings had, all the evidence offered and introduced, all

objections of counsel, all the orders and rulings made and

exceptions allowed and all of the record upon which the

judgment in said cause were made; and the same is a full,

true, correct and complete case-made; and the defendants

31

waive the right to suggest amendments to said ease-made

and hereby consent that the same may be settled immedi

ately and without notice, and hereby join in the request of

the plaintiff that the Judge of said Court settle the same

and order the same certified by the Court Clerk and filed

according to law.

Dated this 7th day of August, 1945.

Amos T. Hill, Attorneys for Plaintiff; Mac Q. W il

liamson, Atty. Gen. of Okla.; Fred Hansen, 1st

Asst. Atty Gen. of Okla., Maurice H. Merrill,

Attorneys for Defendants.

[fol. 66] In the District Court of Cleveland County,

State of Oklahoma

[Title omitted]

Certificate of Trial Judge to Case-Made

Be It Remembered, that on this the 13th day of August,

1946, in the city of Norman, Cleveland County, Oklahoma,

the above and foregoing case-made was presented to me,

Ben T. Williams, regular Judge of the District Court of

Cleveland County, State of Oklahoma, and before whom

said cause was tried, to be settled and signed as the original

case-made herein, as required by law, by the parties to said

cause, and it appearing to me that said case-made has been

duly made and served upon the defendants within the time

fixed by the orders of this Court, and in the time and form

provided by law; that the said defendants have waived

notice of the time and place of presentation hereof, and the

suggestion of amendments hereto, and said plaintiff is

present by his Attorney of Record, Amos T. Hall, and the

said case-made having been examined by me is true and

correct and contains a true and correct statement and com

plete transcript of all the pleadings, motions, orders, evi

dence, findings, judgment and proceedings had in said cause.

I now therefore hereby allow, certify and sign the same

as a true and correct case-made in said cause and hereby

[fol. 67] direct that the Clerk of said Court shall attest the

same with her name and the seal of said Court and file the

32

same of record as provided by law, to be thereafter with

drawn and delivered to the plaintiff herein for filing in the

Supreme Court of the State of Oklahoma.

Witness my hand at Norman, Cleveland County, State of

Oklahoma, on the day and year above mentioned and set out.

Ben T. Williams, District Judge.

Attest: Dess Burke, Court Clerk, Cleveland County, Okla

homa. (Seal.) ‘

[fol. 68] [File endorsement omitted]

I n the Supbeme Court of the State of Oklahoma

No. 32756

A da Lois Sipuel, Plaintiff in Error,

vs.

Board of Regents of the U niversity of Oklahoma, George

L. Cross, Maurice H. Merrill, George Wadsack, and R-oy

Gittinger, Defendants in Error

Stipulation E xtending T ime to F ile Brief— Filed October

' 18, 1946

It is hereby stipulated and agreed, by and between

counsel for the plaintiff in error and the defendants in

error, that the plaintiff in error may have 30 days from

date hereof in which to file a brief in the above entitled

appeal.

Amos T. Hall, Attorney for Plaintiff in E rror; Fred

Hansen, 1st Asst. Atty. Gen., Attorney for Defend

ants in Error.

[fol. 69]—No. 32756—Ada Lois Sipuel v. Board of Regents

of University of Oklahoma, et al., Plaintiff in error granted

until November 22, 1946, in which to file brief, as per stipu

lation.

T. L. Gibson, Chief Justice.

33

[fol. 70] [File endorsement omitted]

In the Supreme Court of the State of Oklahoma

[Title omitted]

Stipulation Extending T ime to F ile Brief— Filed Novem

ber 22, 1946

It is hereby stipulated and agreed, by and between counsel

for the plaintiff in error and the defendants in error, that

the plaintiff in error may have 15 days from date hereof

in which to file a brief in the above entitled appeal.

Amos T. Hall, Attorney for Plaintiff in Error.

Mac Q. Williamson, Atty. Gen.; Fred Hansen, 1st

Asst. Atty. Gen., Attorney for Defendants in

Error.

[fol. 71] The Clerk is hereby directed to enter the follow

ing orders:

32756—Ada Lois Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the Uni

versity of Oklahoma, et al. Plaintiff in error granted until

December 7,1946 to file brief, per stipulation.

T. L. Gibson, Chief Justice.

[fol. 72] [File endorsement omitted]

I n the Supreme Court of the State of Oklahoma

[Title omitted]

Motion for Oral A rgument— Filed January 24, 1947

Comes now the plaintiff in error and respectfully moves

the court to grant leave to submit oral argument in this

cause, and in support thereof represents and shows to the

court as follows:

1. This appeal presents questions of general and state

wide interest and importance involving the constitution

ality of the separate school laws of the State of Oklahoma.

2. The apeal in this case involves a novel question of

general interest and importance which has not heretofore

been decided by this court, to-wit:

34

The refusal of the Board of Regents and the adminis

trative officers of the University of Oklahoma to admit

[fol. 73] plaintiff in error to the School of Law consti

tutes a denial of rights secured under the Fourteenth

Amendment of the constitution of the United States.

3. The nature and affect of this appeal is such that a

proper presentation of the questions involved warrants

submission of oral argument.

Respectfully submitted, Amos T. Hall, Thurgood

Marshall, Robert L. Carter, Attorneys for Plain

tiff in error.

[fol. 74] [File endorsement omitted]

I n the Supreme Court of the State of Oklahoma

[Title omitted]

Motion to A dvance Cause—Filed January 24, 1947

Comes now said plaintiff in error and respectfully moves

this Honorable Court to advance the above-entitled cause

for early hearing, and in support thereof represents and

shows as follows:

1. This is an action in mandamus wherein the plaintiff in

error seeks to compel the Board of Regents of the Uni

versity of Oklahoma to admit her into the Law School of

said university, and the cause involves the refusal to

[fol. 75] admit plaintiff in error to the said School of Law

and as alleged by the plaintiff in error constitutes a denial

of her constitutional rights.

2. The appeal herein has been pending in this court since

August 17, 1946; that the legislature of the State of Okla

homa is now in session and because of the nature of the

action should be decided by this court while the legislature

is still in session.

Amos T. Hall, Thurgood Marshall, Robert L. Carter,

Attorneys for Plaintiff in Error.

35

[fol. 76] [File endorsement omitted]

I n the Supreme Court of the State of Oklahoma

[Title omitted]

Order A ssigning Case— February 6, 1947

For good cause sliown, it is hereby ordered that the above

styled and numbered cause be assigned for oral argument

on the docket for Tuesday, March 4, 1947, at 9:30 A.M. or

as soon thereafter as same may be heard in regular order,

and the Clerk is directed to notify the parties of such

setting.

Thurman S. Hurst, Chief Justice.

[fol. 77] I n the Supreme Court for the State of

Oklahoma

[Title omitted]

A rgument and Submission

March 4, 1947. J. E. Orally Argued and Submitted upon

the Records and Briefs.

[fol. 78] [File endorsement omitted]

I n the Supreme Court of the State of Oklahoma

No. 32756

A da Lois Sipuel, Plaintiff in Error,

vs.

Board of Regents of the U niversity of Oklahoma, George

L. Cross, Maurice II. Merrill, George W adsack and Roy

Gittinger, Defendants in Error

*

Opinion— Filed April 29,1947

S y l l a b u s

1. It is the state’s policy, established by constitution and

statutes, to segregate white and negro races for purpose

36

of education in common and high schools and also institu

tions of higher education. (State ex rel. Bluford v. Can

ada, 153 S. W. 2d 12.)

2. It is the State Supreme Court’s duty to maintain

state’s policy of segregating white and negro races for