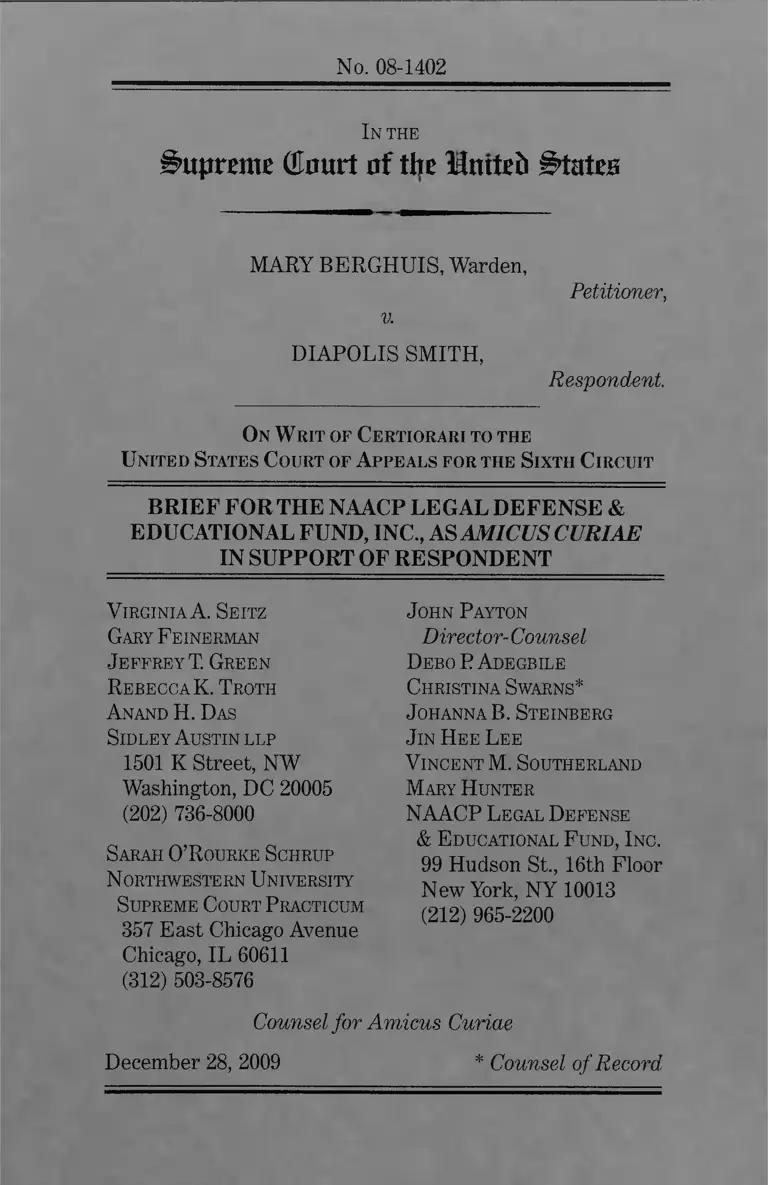

Berghuis v. Smith Brief for the NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund as Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondent

Public Court Documents

December 28, 2009

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Berghuis v. Smith Brief for the NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund as Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondent, 2009. 3e08ecb5-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/83518c08-306a-49ce-a6b8-4307f2223a9a/berghuis-v-smith-brief-for-the-naacp-legal-defense-educational-fund-as-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-respondent. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 08-1402

In THE

Supreme (Court of the lilntteh States

MARY BERGHUIS, Warden,

v.

DIAPOLIS SMITH,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

On W rit of Certiorari to the

U nited States Court of A ppeals for the S ixth C ircuit

BRIEF FOR THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT

V irginia A. S eitz

Gary F einerman

J e ffr e y T. G r een

R ebecca K. T roth

A nand H . D as

S idley A ustin llp

1501 K Street, NW

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 736-8000

Sarah O’R ourke S chrup

N orthwestern U niversity

S upreme C ourt P racticum

357 East Chicago Avenue

Chicago, IL 60611

(312) 503-8576

J ohn P ayton

Director- Counsel

D ebo P A degbile

C hristina Swarns*

J ohanna B. S teinberg

J in H ee L ee

V incent M. S outherland

M ary H unter

NAACP L egal D e fen se

& E ducational F und , I nc .

99 Hudson St., 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2200

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

December 28, 2009 * Counsel of Record

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................................ iii

INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE............ 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT................................. 2

ARGUMENT............................................................. 3

I. REPRESENTATIVE DEMOCRACY IS

THE CENTERPIECE OF THE SIXTH

AMENDMENT RIGHT TO A JURY

CHOSEN FROM A FAIR CROSS-

SECTION OF THE COMMUNITY................. 3

A. The Value Of Representation In Jury-

Service .................................... 3

B. Dureris Prima Facie Test Secures The

Goals Of The Sixth Amendment.............. 5

1. First Prong: Distinctive Groups......... 5

2. Second Prong: Fair And Reasonable

Representation..................................... 6

3. Third Prong: Systematic Exclusion .... 9

II. THE MICHIGAN SUPREME COURT’S

DECISION CONTRAVENES THIS

COURT’S FAIR CROSS-SECTION PRE

CEDENTS .................................................... 9

A. The State Court Proceedings................... 10

B. The Michigan Supreme Court Erred In

Holding That Mr. Smith Failed To

Demonstrate Constitutionally Signifi

cant African American Underrepresen

tation ........................................................ 14

(i)

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS—continued

Page

C. Kent County’s Siphoning Of Prospective

Jurors From The Circuit Court To The

District Courts Systematically Excluded

African Americans From Circuit Court

Venires....................................................... 17

III. AEDPA DID NOT REQUIRE THE

COURT OF APPEALS TO IGNORE

KENT COUNTY’S CONSTITUTIONAL

VIOLATION................................................. 21

A. The Michigan Supreme Court Was

Objectively Unreasonable In Deter

mining That African Americans Were

Not Underrepresented To A Constitu

tionally Significant Degree In Kent

County’s Circuit Court Venire Pool......... 23

1. The Sixth Amendment’s Fair Cross-

Section Requirement Is Clearly

Established Law.................................. 23

2. The Michigan Supreme Court’s Un

reasonable Application Of Clearly

Established Law.................................. 25

B. The Michigan Supreme Court Was

Objectively Unreasonable In Deter

mining That African Americans Were

Not Systematically Excluded From Kent

County’s Circuit Court Venire Pool......... 27

CONCLUSION.................................................... 31

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625

(1972) ...................................................... 1,7

Amadeov. Zant, 486 U.S. 214 (1988)......... 1

Apodaca v. Oregon, 406 U.S. 404 (1972).... 4

Azania v. State, 778 N.E.2d 1253

(Ind. 2002)................................................ 7

Ballard v. United States, 329 U.S. 187

(1946)........................................................ 3

Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986)..... 2

Carey v. Musladin, 549 U.S. 70 (2006)....... 22, 24

Carter v. Jury Comm’n o f Greene County,

396 U.S. 320 (1970).................................. 1

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482 (1977). 9

Davis v. Warden, 867 F.2d 1003

(7th Cir. 1989).......................................... 30

Duren v. Missouri, 439 U.S. 357

(1979)................................. passim

Edmonson v. Leesville Concrete Co., Inc.,

500 U.S. 614 (1991).................................. 2

Ford v. Seabold, 841 F.2d 677

(6th Cir. 1988).......................................... 28

Georgia v. McCollum, 505 U.S. 42 (1992)... 1

Ham v. South Carolina, 409 U.S. 524

(1973) ...................................................... 1

Hobby v. United States, 468 U.S. 339

(1988)........................................................ 1

Holland v. Illinois, 493 U.S. 474 (1990)..... 3

Johnson v. California, 545 U.S. 162

(2005)........................................................ 1, 31

Knowles v. Mirzayance, - U.S. ", 129 S.Ct.

1411 (2009)............................................... 24

Lockhartv. McCree, 476 U.S. 162 (1986)... 4, 5, 6

Lockyerv. Andrade, 538 U.S. 63 (2003)..... 22

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—continued

Page

Miller-Elv. Cockrell, 537 U.S. 322 (2003)... 1

M iller-Elv. Dretke, 545 U.S. 231 (2005).... 1

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935)..... 16

Panetti v. Quarterman, 551 U.S. 930

(2007)......................................................... 22

Paredes v. Quarterman, 574 F.3d 281

(5th Cir. 2009).......................................... 28

Parents Involved v. Seattle, 551 U.S. 701

(2007)......................................................... 17

People v. Burgener, 62 P.3d 1 (Cal. 2003)... 7

Peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493 (1972)...... 4, 5, 6, 9

Ramseur v. Beyer, 983 F.2d 1215

(3d Cir. 1992)............................................ 17

Schriro v. Landrigan, 550 U.S. 465

(2007)......................................................... 24

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940)....... 3, 4

State v. Dixon, 593 A.2d 266 (N.J. 1991).... 7

Statev. Gibbs, 758 A.2d 327 (Conn. 2000).. 7

State v. Lovell, 702 A.2d 261 (Md. 1997) .... 7

State v. Williams, 525 N.W.2d 538

(Minn. 1994)............................................. 7

Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668

(1984)......................................................... 24

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965)...... 1

Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522

(1975)..................................................... passim

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970)....... 1

United States v. Green, 435 F.3d 1265

(10th Cir. 2006)........................................ 6

United States v. Butler, 615 F.2d 685

(5th Cir. 1980).......................................... 16

United States v. Jackman, 46 F.3d 1240

(2d Cir. 1995)........................................ 7, 8, 15

United States v. Maskeny, 609 F.2d 183

(5th Cir. 1980).......................................... 16

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—continued

Page

United States v. Rogers, 73 F.3d 774

(8th Cir. 1996)...................................... 8, 16, 17

United States v. Weaver, 267 F.3d 231

(3d Cir. 2001)............................... 7,28

Washington v, People, 186 P.3d 594

(Col. 2008)................................................. 7

Williams v. Taylor, 529 U.S. 362

(2000)................................................. 21,22,24

Wright v. Van Patten, 552 U.S. 120

(2008)........................................................ 24

STATUTE

28 U.S.C. § 2254................................... 26

SCHOLARLY AUTHORITIES

David Kairys, Joseph Kadane and John

Lehoczky, Jury Representativeness■ A

Mandate for Multiple Source Lists, 65

Cal. L. Rev. 776 (1977)............................. 8,15

Jeffrey Fagan, et. ah, Brief for Social

Scientists, Statisticians, and Law

Professors as Amici Curiae Supporting

Respondent, Berghuis v. Smith (No. 08-

1402) 26

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE1

The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund,

Inc. (“LDF”), is a non-profit corporation formed to

assist African Americans and other people of color

who are unable, on account of poverty, to employ

legal counsel to secure their rights through the

prosecution of lawsuits. LDF has a long-standing

concern with democracy, representation, fair jury

service and selection, and the influence of racial

discrimination on the criminal justice system. LDF

has therefore represented defendants and/or served

as amicus curiae in numerous jury

underrepresentation and jury selection cases before

this Court including, inter alia, Amadeo v. Zant, 486

U.S. 214 (1988); Hobby v. United States, 468 U.S. 339

(1984); Ham v. South Carolina, 409 U.S. 524 (1973);

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1972) and

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965).

LDF also pioneered the affirmative use of civil

actions to end jury discrimination in Carter v. Jury

Comm’n o f Greene County, 396 U.S. 320 (1970), and

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970); and appeared

as amicus curiae in cases challenging the

discriminatory use of peremptory challenges. See

Miller-El v. Dretke, 545 U.S. 231 (2005); Johnson v.

California, 545 U.S. 162 (2005); Miller-El x. Cockrell,

537 U.S. 322 (2003); Georgia v. McCollum, 505 U.S.

42 (1992); Edmonson v. Leesville Concrete Co., Inc.,

1 No counsel for a party authored this brief in whole or in

part, and no such counsel or party made a monetary

contribution intended to fund the preparation or submission of

this brief. No person other than the amicus curiae, or its

counsel, made a monetary contribution intended to fund its

preparation or submission. The parties have consented to the

filing of this brief and such consents are being lodged herewith.

2

500 U.S. 614 (1991); and Batson v. Kentucky, 476

U.S. 79 (1986).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The right to a jury drawn from a fair and

representative cross-section of the community is a

core value of the Sixth Amendment and is essential to

the integrity and legitimacy of the judicial system.

By embodying the value of representative democracy,

the fair cross-section requirement secures the right to

a fair trial, guarantees that all members of distinctive

groups in the community will play a role in the

administration of justice, and allows citizens to serve

as a check on the government. These are the issues

at the heart of Respondent Diapolis Smith’s case.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit correctly found that Mr. Smith’s Sixth

Amendment right was violated after he was convicted

by a jury in Kent County, Michigan, that was drawn

from a pool from which African Americans were

systematically excluded. Mr. Smith established that

in the month his jury was selected, African

Americans were 34 percent less likely to be in the

venire pool relative to their jury-eligible percentage

in the County. He also presented the uncontradicted

testimony of Kent County officials who admitted that

the County’s established practice of “siphoning”

prospective jurors away from its circuit court and to

its district courts caused African Americans to be

underrepresented in the circuit court venire pool, and

that the practice was ultimately terminated because

of those disparities.

Although this uncontested evidence proved that

Kent County’s jury-selection system violated

Mr. Smith’s Sixth Amendment rights, the Michigan

Supreme Court rejected his claim by misapplying this

3

Court’s fair cross-section precedents. Its decision was

not only incorrect, but also objectively unreasonable

under the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death

Penalty Act (“AEDPA”).

ARGUMENT

I. REPRESENTATIVE DEMOCRACY IS THE

CENTERPIECE OF THE SIXTH AMENDMENT

RIGHT TO A JURY CHOSEN FROM A FAIR

CROSS-SECTION OF THE COMMUNITY.

A. The Value Of Representation In Jury Service

As explained by Respondent and supporting amici,

Duren v. Missouri, 439 U.S. 357 (1979), is the

culmination of this Court’s long line of decisions

emphasizing the unique constitutional importance of

jury representativeness.2 This Court has repeatedly

recognized that all qualified segments of the

population must have the opportunity to participate

in the jury process. See Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128,

130 (1940). Thus, “those eligible for jury service are

to be found in every stratum of society,” Ballard v.

United States, 329 U.S. 187, 193 (1946), and the

systematic exclusion from jury service of distinctive

groups is “at war with our basic concepts of a

democratic society and a representative government.”

Smith, 311 U.S. at 130; see also Lockhart v. McCree,

476 U.S. 162, 175 (1986) (explaining that the

2 In advancing this argument, am icus curiae does not assert

that Mr. Smith has the right to a petit jury “of any particular

composition.” Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522, 538 (1975).

Rather, the Sixth Amendment fair cross-section right

contemplates a “fair possibility” of a representative jury, which

is satisfied by the “inclusion of all cognizable groups in the

venire.” H olland v. Illinois, 493 U.S. 474, 478 (1990) (citation

and in ternal quotation marks omitted).

4

wholesale exclusion of women, African Americans

and Mexican Americans “clearly contravened . . . the

purposes of the fair-cross-section requirement”)!

Apodaca v. Oregon, 406 U.S. 404, 413 (1972) (“[T]he

Constitution forbids. . . systematic exclusion of

identifiable segments of the community from jury

panels and from the juries ultimately drawn from

those panels,” and groups have “the right to

participate in the overall legal processes by which

criminal guilt and innocence are determined.”).

Although “[t]he principle of the representative jury

was first articulated by this Court as a requirement

of equal protection,” it long ago “emerged as an aspect

of the [Sixth Amendment] . . . right to jury trial.”

Peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493, 500 n. 9 (1972). Thus, in

Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522, 528 (1975), this

Court made explicit that “the selection of a petit jury

from a representative cross section of the community

is an essential component of the Sixth Amendment

right to a jury trial.”

Soon thereafter, in Duren v. Missouri, this Court

established a three-part test for demonstrating a

prima facie case of a Sixth Amendment fair cross-

section violation. 439 U.S. at 357. Specifically, this

Court stated that:

In order to establish a prima facie violation of

the fair cross-section requirement, the defendant

must show (l) that the group alleged to be

excluded is a ‘distinctive’ group in the

community! (2) that the representation of this

group in venires from which juries are selected is

not fair and reasonable in relation to the number

of such persons in the community! and (3) that

this underrepresentation is due to systematic

exclusion of the group in the jury-selection

process.

5

439 U.S. at 364. Once the prima facie showing has

been made, “it is the State that bears the burden of

justifying [its infringement on the Sixth Amendment

fair cross-section right] by showing attainment of a

fair cross section to be incompatible with a significant

state interest.” Id. at 368.

B. Dureiis Prima Facie Test Secures The Goals

Of The Sixth Amendment.

Each prong of Dureiis prima facie test furthers the

purposes of the Sixth Amendment’s fair cross-section

requirement: “guarding] against the exercise of

arbitrary power [by] makting] available the

commonsense judgment of the community as a hedge

against. . . bias,” Taylor, 419 U.S. at 530, “preserving

‘public confidence in the fairness of the criminal

justice system,’ and implementing our belief that

‘sharing in the administration of justice is a phase of

civic responsibility.’” Lockhart v. McCree, 476 U.S. at

174-75 (quoting Taylor, 419 U.S. at 530-31).

1. First Prong: Distinctive Groups

This Court has not “precisely define [d] the term

‘distinctive group,”’ but it has made clear that its

meaning is “linked to the purposes of the [Sixth

Amendment’s] fair cross-section requirement.” Id. at

174. Thus, women, African Americans and Mexican

Americans have been properly designated distinctive

groups because their exclusion offends the Sixth

Amendment by undermining the legitimacy of the

criminal justice system, denying the fundamental

fairness guaranteed by an impartial jury trial, and

removing a unique voice in the community from

participation in the administration of justice. Id. at

175; see also Peters, 407 U.S. at 499-500, 503-04

(describing how exclusion of African Americans from

6

jury service thwarts the purposes served by the Sixth

Amendment).3

2. Second Prong: Fair And Reasonable

Representation

Because “the selection of a petit jury from a

representative cross section of the community is an

essential component of the Sixth Amendment right to

a jury trial,” Taylor, 419 U.S. at 528, courts must

ensure that the representation of distinctive groups

in venires is “fair and reasonable” relative to their

presence in the community. This is, by definition, a

context-sensitive evaluation. Since distinctive group

size and composition vary from county to county, the

determination whether venire representation fulfills

the Sixth Amendment’s requirements must take into

account all individual circumstances.

Thus, there is no “one size fits all” mathematical

standard or formula for measuring the

reasonableness of a distinctive group’s representation

3 Petitioner’s contention that smaller groups (groups th a t

constitute less than 10% of the venire pool) are not “distinctive

groups” for this purpose, Pet. Br. a t 45-46, is wrong because it

would eviscerate the fair cross-section requirem ent in most

counties in this country and contravene the purposes of the

requirem ent as set forth in Duren and Taylor. To the contrary,

a group is distinctive whenever its exclusion implicates the

Sixth Amendment. See, e.g. Lockhart, 476 U.S. a t 174-75;

Peters, 407 U.S. a t 499-500, 503-04. Thus, federal courts of

appeals determine whether a group is “distinctive” by examining

whether “(l) [ ] the group is defined by a limiting quality (i.e.,

th a t the group has a definite composition such as by race or sex);

(2) a common thread or basic similarity in attitude, idea, or

experience runs through the group,' and (3) [there is a]

community of interests among members of the group such that

the group's in terest cannot be adequately represented if the

group is excluded from the jury selection process.” U nited S ta tes

v. Green, 435 F.3d 1265, 1271 (10th Cir. 2006) (gathering cases).

7

in venires. See Alexander, 405 U.S. at 630 (noting, in

an equal protection case, that “[t]his Court has never

announced mathematical standards for the

demonstration of ‘systemic’ exclusion” of distinctive

groups). Variations in population figures and factual

scenarios have led federal appellate courts to consider

different measures of representativeness depending

on the size of the distinctive group. See United

States v. Weaver, 267 F.3d 231, 242-243 (3d Cir.

2001) (considered facts to determine appropriate

measure of representativeness); United States v.

Jackman, 46 F.3d 1240, 1246-47 n.4 (2d Cir. 1995)

(choosing measure of representativeness after

considering facts).4

The most frequently used measures of

representativeness are the absolute disparity and

comparative disparity tests. “The absolute disparity

test compares the members of a distinctive group that

are jury eligible with those that appear on the

4 Many state supreme courts do the same. See W ashington v.

People, 186 P.3d 594, 605 (Colo. 2008) (en banc) (advancing

argum ent th a t “all the statistical evidence presented” should be

examined by a court facing a fair cross-section claim); People v.

Burgener, 62 P.3d 1, 22 (Cal. 2003) (noting th a t the California

Supreme Court has declined to adopt a particular measure of

underrepresentation); Azania v. State, 778 N.E.2d 1253, 1260

(Ind. 2002) (applying both absolute and comparative disparity);

S ta te v. Gibbs, 758 A,2d 327, 336-37 (Conn. 2000) (explaining

tha t the choice of proper statistical method is fact driven); State

v. Lovell, 702 A.2d 261, 281 (Md. 1997) (advising M aryland state

courts to use multiple measures and supplement absolute

disparity figures with comparative disparity figures when the

distinctive group population falls below 10 percent); Sta te v.

Williams, 525 N.W.2d 538, 543 (Minn. 1994) (validating reliance

on multiple statistical measures of venire representation); Sta te

v. Dixon, 593 A.2d 266, 271 (N.J. 1991) (looking to multiple tests

of underrepresentation in examining a fair cross-section and

equal protection challenge to jury selection process).

8

venire.” Pet. App. 18a. The difference between these

two data ■ the distinctive group’s jury eligible

population figure and presence on the venire - is the

absolute disparity. The comparative disparity

standard, in contrast, measures the percentage by

which the probability of serving on a jury venire is

reduced for the members of the distinctive group.

Comparative disparity is calculated by dividing the

absolute disparity by the population figure of the

distinctive group at issue. David Kairys, Joseph

Kadane & John Lehoczky, Jury Representativeness-

A Mandate for Multiple Source Lists, 65 Cal. L. Rev.

776, 790 (1977).

While the absolute disparity method may have

some utility when the minority population is

relatively large, the approach is of little value when

applied to an underrepresented group that is a

smaller percentage of the total population. Where, as

here, the minority population comprises less than 10

percent of the population, the absolute disparity test,

with a maximum allowable disparity of 10 percent,

yields meaningless results. Underrepresentations of

small and medium-sized minority groups would be

validated under this approach because, by definition,

a smaller group can never have a large absolute

disparity. See Kairys, supra, 65 Cal. L. Rev. at 795-

96. In such circumstances, applying the absolute

disparity measurement improperly allows total

exclusion of the minority group. See United States v.

Rogers, 73 F.3d 774, 776-77 (8th Cir. 1996); Jackman,

46 F.3d at 1247. As the Sixth Circuit properly found

below, the comparative disparity measurement is the

“more appropriate measure of underrepresentation”

where “the distinctive group alleged to have been

underrepresented is small.” Pet. App. 20a.

9

3. Third Prong: Systematic Exclusion

When the underrepresentation of a distinctive

group is “inherent in the particular jury-selection

process” used, it is deemed “systematic.” Duren, 439

U.S. at 366. Fair cross-section claims, unlike equal

protection claims, do not require proof of intentional

discrimination. See id. at 368 n.26. Consistent with

their distinct purposes, the Sixth Amendment focuses

on exclusion caused by the jury selection process,

while the Equal Protection Clause is concerned with

intentional discrimination by government officials

involved in the jury selection process. See Castaneda

v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482, 492-94 (1977) (addressing

equal protection challenge to intentional racial

discrimination in selection of grand jurors); Peters,

407 U.S. at 499-500 (describing constitutional values

offended by purposeful exclusion of African

Americans from jury service). While racially-based

exclusion from jury service may be relevant to finding

a Sixth Amendment violation, intentional

discrimination is not necessary to such a claim, and

the “disproportion itself demonstrates an

infringement of the defendant’s interest in a jury

chosen from a fair community cross section.” Duren,

439 U.S. at 368 n. 26. The Michigan Supreme

Court’s decision must be evaluated within the context

of this legal framework, which has been clearly

established by this Court’s precedent.

II. THE MICHIGAN SUPREME COURT’S

DECISION CONTRAVENES THIS COURT’S

FAIR CROSS-SECTION PRECEDENTS.

The Michigan Supreme Court properly identified

Duren s three-prong test as the standard for

evaluating Mr. Smith’s fair cross-section claim. Pet.

App. 144a. Its determination that Mr. Smith failed to

10

prove a Sixth Amendment violation cannot, however,

be reconciled with this Court’s precedents.

A. The State Court Proceedings

Mr. Smith first raised his Sixth Amendment fair

cross-section claim during jury selection for his Kent

County Circuit Court trial. JA 3a-7a. The circuit

court rejected Mr. Smith’s claim, but, on appeal, the

Michigan Court of Appeals remanded his case for an

evidentiary hearing to determine whether his jury

was drawn from a fair cross-section of the

community. Pet. App. 176a.

At the evidentiary hearing, Mr. Smith, an African

American, presented evidence that, although African

Americans constituted 7.28 percent of the potential

jurors in Kent County, Pet. App. 179a, 214a, his

venire panel of 60 to 100 prospective jurors included,

at most, three African Americans. JA 6a-7a. The

parties examined 37 potential jurors during voir dire,

all of whom were white. Pet. App 86a.

Dr. Michael Stoline, testifying as an expert

statistician in support of Mr. Smith, established that

in September 1993, the month of Mr. Smith’s jury

selection, African Americans were underrepresented

by 34.8 percent, using a comparative disparity

measure. JA 181a; Pet. App. 218a. In the six months

preceding Mr. Smith’s trial, African Americans were

underrepresented by an average of 18 percent.5 Id.

5 Dr. Stoline testified as to the number of African-American

prospective jurors expected to appear on juror lists in each of the

six months from April 1993 to October 1993. JA 217a. In the

month tha t Mr. Smith’s jury was selected, an unbiased selection

process should have produced 11.5 African-American

prospective jurors on the juror lists. Id. a t 218a. Yet, under the

County’s selection process, one could expect to see only 7.5

African Americans for circuit court venires. This resulted in an

11

Through the uncontested testimony of Kim Foster,

Kent County’s Circuit Court Administrator, and

Richard Hillary, Director of Kent County’s Public

Defender’s Office and Co-Chair of the Jury Minority

Representation Committee of the Grand Rapids Bar,

Mr. Smith also presented evidence about the method

of allocating prospective jurors to Kent County’s 12

district courts and one circuit court. The circuit court

is a court of general jurisdiction that presides over

felony criminal cases, like Mr. Smith’s case,

throughout Kent County. By contrast, the district

courts cover discrete geographic areas within the

County and have limited criminal jurisdiction,

hearing only misdemeanor criminal cases and

preliminary criminal hearings.

Prior to October 1993, Kent County had a practice

of filling the district courts’ juror needs before

assigning any prospective jurors to the circuit court

panels. JA 20a, 22a! Pet. App. 8a. Thus, it was only

after the 12 district courts received their prospective

jurors that the remaining prospective jurors were

made available for service in the circuit court. Id.

The district courts used only prospective jurors who

resided in their districts, while the circuit court used

prospective jurors from throughout the County. Pet.

App. 176a. Prospective jurors who were not selected

for district court service were not returned to the

circuit court jury pools. JA 64a - 65a.

Kent County jury selection officials admitted that

this practice of assigning prospective jurors to district

courts before the circuit court effectively “siphoned”

estimated underrepresentation of four prospective African-

American jurors (or 34.8 percent) from the 11.5 figure that

would have occurred without the selection bias. Id. Further

details on the statistical methods employed by Dr. Stoline can be

found in Resp. Br. a t 6-8.

12

jurors away from circuit court venire panels. Pet.

App. 176a-77a, 168a. The qualified jurors siphoned

away from the circuit court included residents of the

City of Grand Rapids, which, at the time, was 18.5

percent African-American and contained 85 percent

of Kent County’s African-American population. JA

197a! Pet. App. 29a. As Mr. Foster, the circuit court

administrator, testified, the “districts essentially

swallowed up most of the minority jurors,” leaving

the circuit court with a jury pool that “did not

represent the entire county.” JA 22a.

Contrary to Petitioner’s contention, Pet. Br. at 61,

Kent County jury officials were unequivocal in their

testimony that the systematic siphoning significantly

reduced the number of African-American prospective

jurors available to the circuit court jury pool.

Indeed, Mr. Foster testified that one month after

Mr. Smith’s September 1993 jury selection, the

County ended the siphoning practice because of the

resulting racial disparities in the circuit court jury

pool. JA 20a, 22a. He further noted that this change

allowed the circuit court to access a “larger

representation of the community [from which] to

select [jurors],” thus remedying the “problem” of

African-American underrepresentation. Id. at 22a.

In addition, Mr. Hillary, the Co-Chair of the Jury

Minority Representation Committee, testified that

after “months of study,” his committee “made a

determination that we were losing minorities by

choosing the District Court jurors first and not

returning the unused ones to . . . the pool that the

Circuit Court was [choosing its jurors] from.” Id. at

64a-65a.6

6 As detailed in Resp. Br. a t 48-50, Mr. Smith also presented

evidence tha t Kent County’s system of automatically accepting

13

At the conclusion of the evidentiary hearing, the

Kent County Circuit Court found

underrepresentation of African Americans in the

circuit court venires, but ruled that there was no

systematic exclusion, thus denying Mr. Smith’s fair

cross-section claim. Pet. App. 209a, 212a.

The Michigan Court of Appeals reversed the circuit

court. In addition to holding that the “representation

of blacks in venires from which juries were selected

for Kent County Circuit Courts was at the time, i.e.,

before October 1, 1993, not fair and reasonable in

relation to the number of such persons in the

community,” the court also held that “the evidentiary

record establishes that the juror allocation system in

place before October 1993 [siphoning] drained the

largest concentration of African-Americans from the

master jury list.” Id. at 18la-182a. Thus, the court

ruled that Mr. Smith was entitled to a new trial. Id.

at 183a.

The Michigan Supreme Court reversed the Court of

Appeals. Although the Michigan Supreme Court held

that African Americans are a distinctive group under

Dureiis first prong, id. at 159a, it ruled that

Mr. Smith’s “statistical evidence failed to establish a

legally significant disparity under either the absolute

or comparative disparity tests.” Id. at 146a. In

reaching its result, the court appeared to treat the

absolute disparity test7 and other measurements of

underrepresentation as equally valid, even though

use of the absolute disparity test would have

non-statutory excuses systematically excluded African American

prospective jurors.

7 The state court appears to have applied an absolute

disparity test with a 10 percent threshold. This is consistent

with Petitioner’s recommendation in this case.

14

sanctioned the complete exclusion of African

Americans from the jury pool. See id. The court then

proceeded to give Mr. Smith the “benefit of the doubt”

as to his claim of underrepresentation, and held that

Mr. Smith had not demonstrated that African

Americans were systematically excluded from Kent

County’s circuit court venires. Id. at 147a-49a, 169a-

71a.

One concurring judge noted that the risks of using

an absolute disparity measurement are “particularly

acute when the percentage of the distinctive group

eligible for jury service is small.” Id. at 161a. He

explained that in the instant case, “a complete

exclusion of black jurors would result in only a 7.28

percent absolute disparity.” Id.

B. The Michigan Supreme Court Erred

In Holding That Mr. Smith

Failed To Demonstrate Constitutionally

Significant African American

Underrepresentation.

In September 1993, the month of Mr. Smith’s jury

selection, African Americans were underrepresented

by 34.8 percent, using a comparative disparity

measure. JA 181a-182a! Pet. App. 218a; see also

supra at 10. Although in the six months preceding

his trial, African Americans were underrepresented

by an average of 18 percent, many individual

defendants, including Mr. Smith, faced even higher

underrepresentation on their venires. The extent of

the systematic underrepresentation on any particular

venire impermissibly depended on the extent of the

siphoning to district court juries at the given time.

Thus, for example, in June 1993, the circuit court

disparity spiked to 42.2 percent. Id. This

demonstrated that African Americans were not fairly

15

and reasonably represented on Kent County Circuit

Court venires relative to their size in the community.

Despite this evidence, the Michigan Supreme Court

held that while Mr. Smith “presented some evidence

of a disparity between the number of jury-eligible

African-Americans and the actual number of African-

American prospective jurors selected to the Kent

County Circuit Court jury pool list,” Pet. App. 146a,

he failed to satisfy Dureris second requirement. Id.

In reaching this conclusion, however, the court

improperly relied on the absolute disparity test,

which produces unreliable results when used to

measure disparities in smaller distinctive group

populations, such as the African-American

community in Kent County. See Jackman, 46 F.3d at

1247 (questioning validity of absolute disparity for

smaller populations due to risk of selecting “a large

number of venires in which members of the group are

substantially underrepresented or even totally

absent”); Kairys, supra, 65 Cal. L. Rev. at 793

(criticizing absolute disparity as an inappropriate

measure for smaller populations).

At the time of Mr. Smith’s trial, African Americans

in Kent County comprised 7.28 percent of the adult

population. JA 172aJ Pet. App. 179a, 214a. The

absolute disparity test was, therefore, an

inappropriate method of measuring the

reasonableness of African-American representation

because that test would condone the complete

exclusion of Kent County’s African-American

community in direct contravention of the Sixth

Amendment’s fair cross-section requirement. This

Court and federal courts of appeals have

acknowledged that such an outcome cannot be

reconciled with this Court’s fair cross-section

precedents. See e.g., Taylor, 419 U.S. at 530-31

16

(explaining that the purposes of a jury cannot be

fulfilled when distinctive groups are excluded from

the venire); Rogers, 73 F.3d at 776-77 (recognizing

that absolute disparity insulates wholesale exclusion

from challenge because “the percentage disparity can

never exceed the percentage of [a distinctive group] in

the community.”); United States v. Butler, 615 F.2d

685, 686 (5th Cir. 1980) (clarifying circuit precedent

by stating that in cases where a “less-than-10-

[percent] minority” was at issue, other statistical

measures would be considered); United States v.

Maskeny, 609 F.2d 183, 190 (5th Cir. 1980)

(considering argument that “reliance on absolute

disparity could lead to approving the total exclusion

from juries of a minority that comprised less than ten

percent of the population of the community” and

avoiding speculation on the appropriate measure to

confront such a situation). The Michigan Supreme

Court thus erred in considering an absolute disparity

analysis when evaluating Mr. Smith’s evidence of

African-American underrepresentation.

Given the size of Kent County’s African-American

population, comparative disparity was the only

measure that could effectively evaluate the extent to

which African Americans were underrepresented on

Kent County circuit court venires. See, e.g., Norris v.

Alabama, 294 U.S. 587, 596-97 (1935) (finding an

equal protection violation in the total exclusion of

African Americans from jury service in a jurisdiction

where African Americans constituted less than eight

percent of the relevant population). The results of a

comparative disparity analysis lead to the inexorable

conclusion that the underrepresentation of African

Americans in the Kent County Circuit Court jury pool

was constitutionally significant and satisfied Dureiis

second prong. See Rogers, 73 F.3d at 777

17

(comparative disparity of more than 30 percent

proves underrepresentation under Duren’s second

prong); Ramseur v. Beyer, 983 F.2d 1215, 1232

(3d Cir. 1992) (comparative disparity of 40 percent

establishes underrepresentation).8

C. Kent County’s Siphoning Of Prospective

Jurors From The Circuit Court To The

District Courts Systematically Excluded

African Americans From Circuit Court

Venires.

Although the Michigan Supreme Court recognized

that “minority jury representation in Kent County

has long been a problem,” Pet. App. 156A, it

concluded that African Americans were not

systematically excluded from Kent County Circuit

8 Petitioner suggests tha t reliance on the comparative

disparity test prevents fair cross-section violations only if the

county “creates a self-conscious process” th a t “identif[ies] the

race and ethnicity of every prospective juror,” thereby

“effectively requir[ing] a quota system.” Pet. Br. a t 43. This

invocation of quotas is a red herring that this Court should

ignore. First, as previously noted, comparative disparity is a

legitimate and effective measure of representation endorsed by

numerous courts and experts. Second, regardless of the method

of proof, a quota is never a proper remedy for a Sixth

Amendment fair cross-section violation. Quotas are applicable

only to very limited circumstances involving demonstrated

intentional discrimination. See Parents Involved v. Seattle, 551

U.S. 701, 795-796 (2007) (Kennedy, J., concurring) (describing

the “allocation of benefits and burdens through individual racial

classifications” as “sometimes permissible in the context of

remedies” for a “de jure” wrong like “segregation”,). Finally, both

Duren and Taylor expressly state that the fair cross-section

mandate does not require “that petit juries actually chosen must

m irror the community,” but rather m ust simply prevent the

systematic underrepresentation of distinctive groups in jury

pools. Duren, 439 U.S. a t 364 n.20 (quoting Taylor, 419 U.S. a t

538). That requirem ent is not a quota, and will not lead to one.

18

Court jury pools. This conclusion cannot be

reconciled with this Court’s precedents. Kent

County’s jury selection process systematically

excluded African Americans by siphoning prospective

jurors away from the circuit court and to the district

courts. Accordingly, Mr. Smith satisfied Dureiis

third prong.

As detailed above, 85 percent of Kent County’s

African-American population lived in Grand Rapids,

which composes one of the 12 districts. As previously

noted, it was Kent County ’s practice to prioritize

district courts over the circuit court for the

assignment of prospective jurors, allowing only

residents of the district in which the district court

sits to serve on juries in that court. Also, prospective

jurors were excused after district court service rather

than returned to the jury pool for circuit court

service. As a consequence, the district courts

“siphoned” African Americans away from circuit court

jury service. This process was “inherent” to Kent

County’s jury selection system, see Duren, 439 U.S.

at 366, and resulted in the persistent

underrepresentation of African Americans in circuit

court venires, with 34 percent underrepresentation in

the month of Mr. Smith’s voir dire, an average of 18

percent underrepresentation over six months, and a

high of 42 percent just two months before Mr. Smith’s

jury selection. JA 181a-82al Pet. App. 218a.

Precise numbers documenting how many

prospective African-American jurors were affected by

this process were unavailable because the County

chose not to collect race data.9 However, as the Sixth

9 Petitioner is incorrect to the extent tha t it suggests tha t

underrepresentation can be shown only by actual race data, as

opposed to extrapolations from a data set such as the 1990

19

Circuit explained, it logically follows that the jury

selection process resulted in “fewer African

Americans [being] available to serve as jurors for

county circuit court[ ].” Pet. App. 29a.

Moreover, the Kent County Circuit Court

Administrator readily admitted that the siphoning

used by Kent County to select circuit court jury pools

at the time of Mr. Smith’s trial systematically

excluded African Americans. See supra at 12.

Indeed, one month after Mr. Smith’s September 1993

jury selection, the County ended the siphoning

practice because it believed that siphoning caused

unacceptable African-American underrepresentation

in the circuit court jury pool. JA 20a, 22a. The

Circuit Court Administrator noted that ending the

siphoning practice allowed the circuit court to access

a “larger representation of the community to select

[jurors] from,” thus remedying the “problem” of

African-American underrepresentation. Id. at 22a.

The record also reflects that once the County

terminated its siphoning practice, the racial

disparities began to fade. Dr. Stoline’s analysis

included data covering the eleven months following

Mr. Smith’s jury selection, beginning in October 1993

when Kent County officials testified they

discontinued siphoning African Americans away from

the circuit court and towards the district courts. JA

20a, 22a. Using a method consistent with that used

for his analysis of the prior six months, Dr. Stoline

found that African Americans were underrepresented

census. No court has so held; in fact, Duren expressly permitted

the use of census data. See Duren, 439 U.S. at 364-65.

Moreover, adoption of Petitioner’s position would allow court

adm inistrators in communities with smaller, but sizeable,

minority populations to foreclose fair cross-section challenges

simply by choosing not to collect race data.

20

by 15.1 percent in the eleven-month post-siphoning

period studied. Id. at 102a-03a. Extremely high

levels of underrepresentation, similar to those

occurring in the siphoning period, were concentrated

in two of the first five months of the post-siphoning

period: African Americans were underrepresented by

41.1 percent in the third month and 43.5 percent in

the fifth month. Id. at 102a. These spikes appear to

have faded away over time such that the highest

African-American underrepresentation in the final

six months of the eleven-month post-siphoning study

was 22.2 percent, occurring in the penultimate

month, and the average for the final six months was

15.1 percent. Id. These figures suggest that it took

several months before the positive effects of the new

non-siphoning system were reflected in the data.

Petitioner’s contrary suggestion, Pet. Br. at 50, 61,

that the post-siphoning data somehow proves that

the systematic removal of over three-quarters of the

county’s African Americans from the qualified pool

never had any effect - is therefore baseless.

Despite this undisputed evidence, the Michigan

Supreme Court held that the third Duren prong was

not satisfied. This conclusion is incorrect and

unreasonable because the practice of allocating

prospective jurors to the district courts before the

circuit court necessarily “siphoned” African

Americans away from the circuit court, leaving a

persistent and serious underrepresentation in that

court. This logical inference is supported by

testimony from institutional actors within the jury

selection system, see supra at 11-12, and by the

recommendation of the study committee that ended

the practice, JA 64a_65a. This evidence has

dispositive weight because it reflects the most

pertinent and knowledgeable observations of the

21

effect of siphoning in Kent County’s jury selection

system. The Michigan Supreme Court’s decision that

Mr. Smith failed to establish systematic exclusion of

African Americans is incorrect.

III. AEDPA DID NOT REQUIRE THE

COURT OF APPEALS TO IGNORE

KENT COUNTY’S CONSTITUTIONAL

VIOLATION.

As shown above, the Michigan Supreme Court

erred in rejecting Mr. Smith’s Sixth Amendment fair

cross-section claim. Under AEDPA, however, a

federal court may not grant habeas relief merely

because it believes, in its own “independent

judgment,” that the state court “erroneously or

incorrectly” decided a federal constitutional claim.

Williams v. Taylor, 529 U.S. 362, 411 (2000)

(O’Connor J., concurring). Rather, a federal habeas

court must determine that the decision was an

“objectively unreasonable” application of “clearly

established” United States Supreme Court law, as

properly held by the Sixth Circuit below. Id. at 409

(O’Connor, J., concurring).

The phrase “clearly established law” “refers to the

holdings, as opposed to the dicta, of this Court’s

decisions as of the time of the relevant state-court

decision.” Id. at 365. “[Rjules of law may be

sufficiently clear for habeas purposes even when they

are expressed in terms of a generalized standard

rather than a bright-line rule.” Id. at 382. States are

bound by clearly established law regardless whether

it is expressed in general or specific terms, and state

court decisions applying such law must be

reasonable.

AEDPA does not require state and federal courts to

wait for some nearly identical factual pattern before a

22

legal rule must be applied.” Carey v. Musladin, 549

U.S. 70, 80-81 (2006) (Kennedy, concurring). Nor

does AEDPA prohibit a federal court from finding an

application of a principle unreasonable when it

involves a set of facts “different from those of the case

in which the principle was announced.” Lockyer v.

Andrade, 538 U.S. 63, 76 (2003). The statute

recognizes, to the contrary, that even a general

standard may be applied in an unreasonable manner.

Panetti v. Quarterman, 551 U.S. 930, 953 (2007)

(citing Williams, supra). Thus, “[i]f the state court’s

adjudication is dependent on an antecedent

unreasonable application of federal law, . . . the

federal court must then resolve the claim without the

deference AEDPA otherwise requires.” Id. at 931

(citing Wiggins v. Smith, 539 U.S. 510, 534 (2003));

see also Williams, 529 U.S. at 412 (O’Connor, J„

concurring).

For the reasons detailed below, the Sixth Circuit

properly applied this precedent and determined that

while the Michigan Supreme Court “identified] the

correct governing legal principle from this Court’s

decisions,” it “unreasonably applie[d] that principle to

the facts of [Mr. Smith’s] case.” Williams, 529 U.S. at

412.

23

A. The Michigan Supreme Court Was

Objectively Unreasonable In Determining

That African Americans Were Not

Underrepresented To A Constitutionally

Significant Degree In Kent County’s Circuit

Court Venire Pool.

1. The Sixth Amendment’s Fair Cross-

Section Requirement Is Clearly

Established Law.

In applying Dureiis first step, the Michigan

Supreme Court correctly ruled that African

Americans constituted a distinctive group under the

Sixth Amendment’s fair cross-section requirement.

With respect to Dureiis second step, the Michigan

Supreme Court concluded that because each of the

various measures of representation had

shortcomings, it would “consider all these approaches

to measuring whether representation was fair and

reasonable.” Pet. App. 146a. This is an accurate

recitation of this Court’s clearly established law.

Because the degree of underrepresentation

necessary to implicate these Sixth Amendment

concerns and to satisfy Dureiis second step will

naturally vary with the size of the distinctive group

and the size of the counties from which the venires

are drawn, Duren requires exactly such a case-

specific approach. Thus, the Michigan Supreme

Court properly identified this Court’s clearly

established law.

The fact that Dureiis assessment of “fair and

reasonable representation” must be conducted on a

case-bycase basis does not mean that the test lacks

the specificity necessary to constitute clearly

established law under AEDPA. To the contrary, as

detailed in Respondent’s Brief at 55-57, Dureiis test

24

is analogous to the Strickland v. Washington test, see

466 U.S. 668, 688-89 (1984), for assessing the

effective assistance of counsel - it is the type of

clearly established rule “which of necessity requires a

case-by-case examination of the evidence,” and can

therefore “tolerate a number of specific applications

without saying that those applications themselves

create a new rule.” Williams, 529 U.S. at 382

(quoting Wright v. West, 505 U.S. 277, 308-09

(1992)). The Duren test is a clear standard that must

be reasonably applied by the state courts.

In arguing that Duren’s test is too general to

constitute clearly established law, Petitioner cites

Wright v. Van Patten, 552 U.S. 120 (2008), and

Carey, 549 U.S. at 70. See Pet. Br. at 35-36. These

decisions are, however, inapplicable to Mr. Smith

because they involve attempts to extend Supreme

Court law to novel ground. In Carey, this Court

rejected the Ninth Circuit’s attempt to extend the

clearly established law governing state-sponsored

courtroom practices to private spectator conduct, an

application not previously contemplated by this

Court. See 549 U.S. at 654. And in Wright, this

Court found the state court’s application of federal

law to be reasonable where “[n]o decision of this

Court squarely addresse[d] the issue in this case.”

Wright, 552 U.S. at 125, see also Knowles v.

Mirzayance, -- U.S. ", 129 S.Ct. 1411, 1419 (2009) (no

unreasonable application of clearly established law

where “[t]his Court has never established anything

akin to the Court of Appeals’ ‘nothing to lose’

standard for evaluating Strickland claims”); Schriro

v. Landrigan, 550 U.S. 465, 478 (2007) (no

unreasonable application of clearly established

federal law where “we have never addressed a

situation like this.” (internal citation omitted)). This

25

authority is irrelevant to Mr. Smith because he did

not seek to extend Supreme Court law to a new

context. The fact that the federal courts of appeal

and state supreme courts agree with Mr. Smith that

Duren requires a case-specific approach to measuring

underrepresentation further demonstrates that Mr.

Smith is not seeking to apply Supreme Court law to a

different, and unanticipated, circumstance. See Resp.

Br. at 27-30.

2. The Michigan Supreme Court’s

Unreasonable Application Of Clearly

Established Law.

After properly identifying this Court’s clearly

established law, the Michigan Supreme Court

unreasonably applied it to the facts of Mr. Smith’s

case. The court concluded that Mr. Smith “presented

some evidence of a disparity between the number of

jury-eligible African Americans and the actual

number of African-American prospective jurors

selected to the Kent County Circuit Court jury pool

list.” Pet. App. 146a. It then declared, however, that:

[Djefendant’s statistical evidence failed to

establish a legally significant disparity under

either the absolute or comparative disparity

tests. Nevertheless, rather than leaving the

possibility of systematic exclusion unreviewed

solely on the basis of defendant’s failure to

establish underrepresentation, we give the

defendant the benefit of the doubt on

underrepresentation and proceed to the third

prong of the Duren analysis.

Id. at 146a-47a. Although this ruling is not a model

of clarity, AEDPA controls here because the Michigan

Supreme Court held that Mr. Smith failed to meet his

prima facie burden under Duren’s second prong. See

26

28 U.S.C. § 2254(d). That decision was objectively

unreasonable.

As previously noted, at the time of Mr. Smith’s

trial, African Americans comprised 7.28 percent of

Kent County’s adult population. Under these

circumstances - which are analogous to those

prevailing in the vast majority of African-American

communities throughout the country, see Brief for

Social Scientists, Statisticians, and Law Professors,

Jeffrey Fagan, et. al, as Amici Curiae Supporting

Respondent - the Sixth Amendment can tolerate only

a limited degree of African-American exclusion and

underrepresentation before implicating the Sixth

Amendment’s fair cross-section requirement. Thus,

in order to apply Duren and this Court’s other fair

cross-section precedents reasonably, the state court

should have recognized that relying on an absolute

disparity measurement would have improperly

allowed the total exclusion of Kent County’s African-

American population from its jury venires.

The Michigan Supreme Court ignored this

constitutionally significant fact. Although it properly

acknowledged that Duren required a case-specific

analysis and that the absolute disparity test

“produces questionable results . . . where the

members of the distinctive group comprise a small

percentage of those eligible for jury service,” Pet. App.

145a, the state court nonetheless gave equal

consideration to the results of an absolute disparity

analysis in evaluating Mr. Smith’s evidence of

underrepresentation. Because the absolute disparity

test would permit the total exclusion of Kent County’s

African-American community from venires, the state

court’s application of Duren was objectively

unreasonable.

27

Furthermore, the state court unreasonably applied

Duren by undervaluing Mr. Smith’s comparative

disparity evidence. Mr. Smith demonstrated that

African Americans were underrepresented by 34.8

percent in the month of his jury selection. As the

Sixth Circuit found, this is “sufficient to demonstrate

that the representation of African-American

veniremen in Kent County at the time of

[Mr. Smith’s] trial was unfair and unreasonable.”

Pet. App. 21a (citing Rogers, 73 F.3d at 777).

For these reasons, the Michigan Supreme Court’s

judgment was objectively unreasonable under

AEDPA in concluding that Mr. Smith failed to

demonstrate that African Americans were

underrepresented on Kent County Circuit Court

venires.

B. The Michigan Supreme Court Was

Objectively Unreasonable In Determining

That African Americans Were Not

Systematically Excluded From Kent County7s

Circuit Court Venire Pool.

Duren’s third step requires proof that the

underrepresentation is “due to systematic exclusion

of the group in the jury-selection process.” Duren,

439 U.S. at 364. The Sixth Circuit correctly held that

the Michigan Supreme Court unreasonably applied

Duren in finding no systematic exclusion in Kent

County’s practice of siphoning jurors away from the

circuit court to district courts. Pet. App. 41a_42a.

The “systematic exclusion” analysis focuses on the

identification of processes integral to the jury

selection system that may have caused persistent

underrepresentation of distinctive groups, and must

be conducted independent of Duren’s other steps.

See, e.g., Weaver, 267 F.3d at 241 (“strength of the

28

evidence should be considered under the second

prong, while the nature of the process and the length

of time of underrepresentation should be considered

under the third”)! Fordv. Seabold, 841 F.2d 677, 685

& n.6 (6th Cir. 1988) (“Although the frequency of the

selection of jury venires is not, of itself, helpful in

establishing underrepresentation under the second

prong of the prima facie case, it is of crucial

significance in establishing that any existing

exclusion was systematic.”). Accordingly, the

persistence of African-American underrepresentation

of 18 percent10 over a six-month period supports the

systematic nature of their exclusion from the

qualified circuit court jury pool. See Duren, 439 U.S.

at 367 (“The resulting disproportionate and

consistent exclusion of women from the jury wheel

and at the venire stage was quite obviously due to the

system by which juries were selected.”).11

10 The persistence of the 18 percent underrepresentation over

the course of six months, which satisfies D urens third step, is

separate from the degree of the 34 percent underrepresentation

during the month of Mr. Smith’s jury selection, which satisfies

Duren s second step. To conflate these two analyses would make

either the second or third step superfluous. See Paredes v.

Quarterman, 574 F.3d 281, 290 (5th Cir. 2009) ( [Petitioner]

repeats his position th a t a large discrepancy exists but does not

explain how th a t second-prong statem ent alone satisfies the

requirem ents of the third prong, which requires an independent

showing th a t the discrepancy is systematic. If any discrepancy

sufficient to satisfy the second prong would also satisfy the

third, the th ird inquiry would be superfluous.”).

11 Despite th is Court’s clearly established law th a t no

discriminatory in tent is required in fair cross-section cases, See

supra a t 9, Petitioner attempts to inject an in tent requirem ent

into Duren s concern with the systematic underrepresentation of

distinctive groups. Pet. Br. a t 44. In fact, Duren instructs only

tha t the exclusion be “inherent in the particular jury-selection

process utilized.” Duren, 439 U.S. a t 366. As explained in

29

The Michigan Supreme Court’s analysis of

“systematic exclusion” was fundamentally flawed,

and thus objectively unreasonable, because it ignored

pertinent, uncontested evidence of Kent County’s

siphoning procedure and imposed a burden of proof

that exceeded Dureds mandate for establishing a

prima facie case of a fair cross-section violation.

In rejecting Mr. Smith’s claim of systematic

exclusion resulting from the siphoning procedure, the

Michigan Supreme Court held that he had “failed to

carry his burden of proof’ because the “record does

not disclose whether the district court jury pools

contained more, fewer, or approximately the same

percentage of minority jurors as the circuit court jury

pool.”12 Pet. App. 147a. The state court’s summary

conclusion directly contradicts the evidence in the

record. The uncontested testimony of Kent County

jury officials and the results of a bar study committee

both showed that the siphoning procedure was a

significant source of African-American

underrepresentation in circuit court venire panels,

which led Kent County to terminate this practice in

Section 11(C), supra, Kent County’s siphoning practice meets

th a t test because it was part of the jury selection system and

caused the underrepresentation of African Americans in Kent

County’s circuit court jury pool. Under this Court’s precedent,

ignoring the discriminatory effect of the siphoning and

demanding evidence of a discriminatory purpose would plainly

be unreasonable.

12 The concurring opinion further commented th a t “after Kent

County stopped selecting district court jurors first, the change in

the representation of black jurors in circuit court was small,

suggesting th a t the alleged systematic exclusion was not the

cause of the underrepresentation.” Pet. App. 169a. However, as

noted in Section 11(C), supra at 19-20, the record suggests th a t it

took several months for the effects of term inating the siphoning

procedure to be reflected in the jury pool data.

30

October 1993. There was no contrary evidence in the

record. See supra at 18-20.

The state court’s understanding of Mr. Smith’s

burden of proof under Duren was also objectively

unreasonable. The State in Duren, like Petitioner

here, argued that there was no proof “that the

exemption for women had ‘any effect’ on or was

responsible for the underrepresentation of women on

venires.” 439 U.S. at 368. This Court, however,

determined that Duren’s third step was satisfied by

evidence that the exemption for women was “inherent

in the particular jury-selection process utilized,” thus

shifting the burden to Petitioner to “demonstrate that

[other] exemptions caused the underrepresentation

complained of.” Id. at 366, 368. The same response is

warranted here, where the officials in the best

position to provide information about Kent County’s

jury selection system testified that the siphoning

procedure systematically excluded African Americans

from the qualified circuit court jury pool. See

Section 11(C), supra. The Michigan Supreme Court’s

imposition of a higher burden of proof is an

objectively unreasonable application of Duren.13 See

Davis v. Warden, 867 F.2d 1003, 1014 (7th Cir. 1989)

(“The Supreme Court . . . and other courts have

recognized that defendant should not be expected to

13 Contrary to Petitioner’s assertions (Pet. Br. a t 60),

28 U.S.C. § 2254(e) has no relevance here because Mr. Smith

seeks habeas relief under 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d)(1). Section

2254(e) governs state court factual findings, and Mr. Smith does

not take issue with the facts found by the Michigan Supreme

Court. Instead, he challenges tha t Court’s application o f law to

those facts and, thus, contends th a t the court’s ruling of no

evidentiary support for “systematic exclusion” was an

“unreasonable application of’ Dureris third prong under Section

2254(d)(1).

31

carry a prohibitive burden in proving

underrepresentation.” (citations omitted)); cf.

Johnson, 545 U.S. at 170 (prima facie case of Batson

violation established by “evidence sufficient to permit

the trial judge to draw an inference that

discrimination has occurred”).

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals should be

affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

Virginia A. Seitz

Gary Feinerman

J effrey T. Green

Rebecca K. Troth

Anand H. Das

Sidley Austin llp

1501 K Street, NW

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 736-8000

J ohn Payton

Director - Co unsel

Debo P. Adegbile

Christina Swarns*

J ohanna B. Steinberg

J in Hee Lee

Vincent M. Southerland

Mary Hunter

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson St., 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2200

Sarah O’Rourke Schrup

Northwestern

University Supreme

Court Practicum

357 East Chicago Avenue

Chicago, IL 60611

(312) 503-8576

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

December 28, 2009 * Counsel o f Record