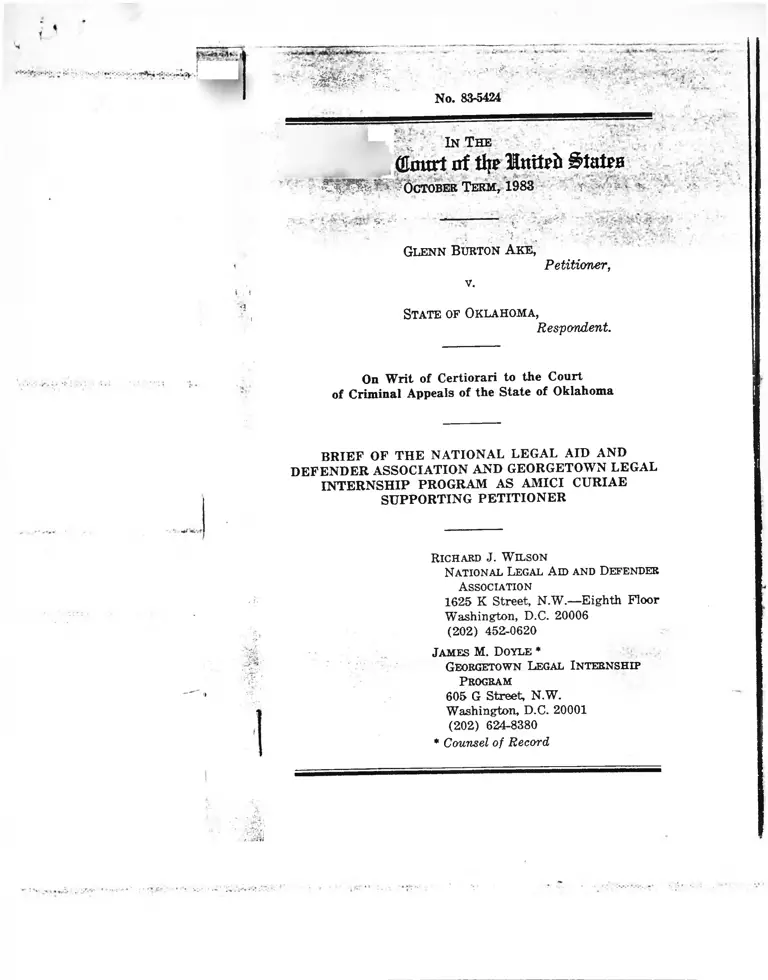

Ake v. Oklahoma Brief of the National Legal Aid and Defender Association and Georgetown Legal Internship Program as Amici Curiae Supporting Petitioner

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ake v. Oklahoma Brief of the National Legal Aid and Defender Association and Georgetown Legal Internship Program as Amici Curiae Supporting Petitioner, 1983. 345f6f2c-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/836ffdc6-bb04-482d-a8f0-85f896cc97eb/ake-v-oklahoma-brief-of-the-national-legal-aid-and-defender-association-and-georgetown-legal-internship-program-as-amici-curiae-supporting-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

■■ s#

\ . \

V|.

• t

;•** . . f . -> .■ v7 :•' .....' --v «srSl

. f r w ~

- .«• - /- 7 .#?*; - *.'”•■ •. • • ‘■ • '. :•' '■■■■: ' ■ '•' ■■ ’ i ' . :'t '< , '

No. 83-5424

In The. v

(Jlnurt of tl|P Ilnitp^ States

•• •^^^<.T.-*>..^5cT0BBB Term, 1988 • r v , X ■

y. <- •• • -------' V *". ,.. . ;■ -:/1;. .‘. y

Glenn Burton Ake, y r i

Petitioner,

v.

State of Oklahoma,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Court

of Criminal Appeals of the State of Oklahoma

BRIEF OF THE NATIONAL LEGAL AID AND

DEFENDER ASSOCIATION AND GEORGETOWN LEGAL

INTERNSHIP PROGRAM AS AMICI CURIAE

SUPPORTING PETITIONER

Richard J. W ilson

N ational Legal A id and Defender

A ssociation

1625 K Street, N.W.—Eighth Floor

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 452-0620

James M. Doyle *

Georgetown Legal Internship

P rogram

605 G Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20001

(202) 624-8380

* Counsel oj Record

Issue Presented

Amici will address the following

issue:

WHETHER THE TRIAL COURT

VIOLATED THE PETITIONER'S

RIGHT TO EFFECTIVE

ASSISTANCE OF COUNSEL WHEN

IT DENIED HIM EXPERT AND

INVESTIGATIVE SERVICES

NECESSARY TO DEVELOP AND

PRESENT HIS INSANITY DEFENSE

AND TO REBUT THE PROSE

CUTION'S PSYCHIATRIC TESTI

MONY AT THE PENALTY PHASE OF

HIS CAPITAL TRIAL?

-i-

TABLE ££ CONTENTS

Table of Authorities............... iv

Interest of Amici ................. 1

Issue Presented ...................

WHERE THE TRIAL COURT DENIED

DEFENSE COUNSEL EXPERT AND

INVESTIGATIVE SERVICES

NECESSARY TO DEVELOP AND

PRESENT PETITIONER'S INSANITY

DEFENSE AND TO REBUT THE

PROSECUTION'S PSYCHIATRIC

TESTIMONY AT THE PENALTY

PHASE OF HIS CAPITAL TRIAL,

THE PETITIONER'S RIGHT TO

EFFECTIVE ASSISTANCE OF

COUNSEL WAS VIOLATED ........... i

I. THE PROPER FUNCTIONING OF

THE ADVERSARIAL PROCESS IS

UNDERMINED WHEN DEFENSE

COUNSEL IS DENIED THE MEANS

NECESSARY FOR DEVELOPING A

DEFENSE ........................ 5

-ii-

II. AN ATTORNEY WITH RESOURCES

WHO FAILED TO INVESTIGATE

AN INSANITY DEFENSE ON

PETITIONER'S BEHALF WOULD

HAVE PERFORMED IN A

CONSTITUTIONALLY DEFICIENT MANNER....................... 13

III. THE GENERAL POLICIES WHICH

SUPPORT DOCTRINES OF

FINALITY IN THE CRIMINAL

LAW ALSO SUPPORT THE

ALLOCATION TO APPOINTED

COUNSEL OF THE RESOURCES

NECESSARY TO FULFILL HIS

CRITICAL ROLE IN THE

ADVERSARY SYSTEM ............... 18

Conclusion............................24

-iii-

TABLE Q£ AUTHORITIES

CASES

Beavers v. Balkcom, 636 F.2d

114 (5th Cir. 1 9 8 1 ) ................. 16

Brennan v. Blankenship, 472

F.Supp. 149 (D.W.D.Va. 1979). . . . 17

Davis v. State of Alabama, 596

F. 2d 1214 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 9 ) ......... 15

Greer v. Beto, 379 F.2d 923

(5th Cir. 1 9 6 7 ) ................... 16

McMann v. Richardson, 397 U.S.

759 (1970).......................... 7

Strickland v. Washington,

___U.S.___ (1984)................. 5,8

13,17,20

United States v. Cronic,

___U.S.___ (1984)................. 5

United States v. Fessel,

531 F.2d 1275

(5th Cir. 1 9 7 6 ) ................... 16

United States ex rel. Smith v.

Baldi, 344 U.S. 561 (1953)........ 22

-iv-

CONSTITUTION AND STATUTES

United States Constitution:

Sixth Amendment . . . .

18 U.S.C. §3006A(e)

(Supp. 1979)........

MISCELLANEOUS:

passim

9

Alschuler, The Defense

Attorney's Role in Plea

Bargaining, 84 YALE L.J.1179 (1975) .................

Bator, Finality in Criminal Law

and Federal Habeas Corpus for

State Prisoner, 76 HARV.L.REV.

21-22

Criminal Defense Technical

Assistance Project, A

Study of Defense Services

for Indigent Criminal

Defendants In South Carolina:

Analysis and Recommendations,

26

- v -

American Bar Association,

Standards Relating to the

Administration of Criminal

Justice, (1970) ............. 7,9

Saltzburg, A Special Aspect

of Relevance: Countering

Negative Inferences

Associated With the Absence

of Evidence, 66 CAL.L.REV.

1011 (1978)................. 12

Note, The Indigent's Right

to an Adequate Defense:

Expert and Investigational

Assistance in Criminal

Proceedings, 55 CORNELL L.REV. 632 (1970)............. 10

53-5425

In The Supreme Court of the United

States

October Term, 1983

Glen Burton Ake,

Petitioner

v.

State of Oklahoma,

Respondent

Interest q± Amici

The National Legal Aid and Defender

Association (NLADA) is the sole national

voice for the overwhelming majority of

- 1 -

public defenders, private attorneys and

defender clients who make up its defender

membership. Representing nearly 600

member public defender offices and about

7,000 individual defenders, NLADA has

spoken out on national issues of concern

to the legally indigent and their

attorneys in both civil and criminal

cases.

The Legal Internship Program is a

graduate degree program in Trial

Advocacy. Each year since 1960 ten E.

Barrett Prettyman Fellows have

represented indigent criminal defendants

in the District of Columbia Court of

Appeals, the District of Columbia

- 2 -

superior Court and the United states

District Court and the United States

Court of Appeals for the District of

Columbia Circuit. since the program's

inception, Georgetown graduate fellows

have represented more than two thousand

indigent clients in the District of

Columbia courts. Fellows also supervise j

third year law students from Georgetown

University Law Center who undertake to

represent indigents charged with

misdemeanor offenses in the Superior

Court. The third component of the

fellowship — alongside teaching and

practice — is scholarship. Fellows must

complete a thesis of publishable quality

-3-

in order to earn an LL.M. degree.

Amici are vitally interested in the

role played by defense counsel in the

administration of criminal justice. it

is that interest which leads us, after

considering the content of this case, to

join as amici curiae in urging this Court

to hold that the Petitioner's right to

effective assistance of counsel was

violated when the trial judge refused to

Provide expert psychiatric and

investigative services necessary to

develop his insanity defense and to rebut

prosecution psychiatric testimony at the

Penalty phase of his capital trial.

- 4 -

I

proces?PERtoFUNCTIONING of the adversarial

This term in United StafPc v.

£r'°nifi/ ---U,S*---' 52 USLW 4560 (1984)

and Strickland v. __u.s.__ _

52 USLW 4565 (1984) this Court made its

first extended statements concerning the

scope and content of a criminal

defendant's right to effective assistance

of counsel. A central theme in the

Court's opinions was stated by Justice

O'Connor, writing for the Court in

S trickland v. Washinqfpn .

-5-

The benchmark for judging

any claim of ineffectiveness i

must be whether counsel's

conduct so undermined the

proper functioning of the

adversial process that the

trial cannot be relied on as

having produced a justresult. j i

52 USLW at 4570. j

Amisi contend that unless attorneys j

acting on behalf of indigent defendants

are provided with the means necessary to ;

develop reasonable defenses, their

representation is doomed to fall below

the standard set in Stricklanri v.

Washington,

Not every lawyer can be a tactical |

genius and even very good lawyers do not

perform equally well in every case. That

-6-

\

there will be some variance in lawyer

performance was implicity accepted by

this Court when in McMann v. Richarrifinn

it referred to "the range of competence

demanded of attorneys in criminal cases".

397 U.S. 759, 771 (1970). It is fair to

say, however, that no one disputes that

counsel has a duty to explore and develop

the factual context of reasonable

defenses. ABA, Standards Relating to the

Prosecution Function and the Defense

Function §4.1 (1970); Alschuler, The

Defense Attorney's Role in Plea

Bargaining, 84 Yale L.J. 1179 (1975).

At times this exploration quickly

will lead to obvious dead-ends. At times

-7-

totoo, it may be possible adequately

conduct an exploration without seeking

the provision of expert or investigative

service. For example, counsel may be

able to eliminate potential defenses

Simply by conferring with his client.

£txickIan(1 v- Washington,

---U.s.---, 52 USLW at 4571. m other

cases, published works on forensic

techniques may obviate the need for

expert services. Nevertheless, there

will continue to be cases in which

defense counsel, barred by ethical

standards from testifying at trial,

cannot develop a defense without having

an investigator available to testify.

Moreover, there will continue to be

cases, such as the Petitioner's, in which

the absence of a witness is compounded by

the absence of any personal expertise on

the part of counsel in a highly

specialized and technical field.The

Congress and the vast majority of state

legislatures make provision for such

cases. 18 U.S.C. §3006A(e) (Supp. 1979);

Statues cited, Petition for Certiorari at

13n. °f the legal commentators who

have addressed the issue agree that some

cases will call for the appointment of

expert psychiatrists. See e.g., ABA

Standards Relating to the Administration

of Criminal Justice §1.5 (Draft 1968);

Note, The Indigent's Right to an Adequate

Defense: Expert and Investigational

Assistance In Criminal Proceedings, 55

Cornell L. Rev. 632, 641-643 (1970) .

Petitioner1s case provides an

illustration of the wisdom of those

views.

When a defense lawyer is deprived

of services necesary to develop his case

that deprivation does not create merely a

gap in the evidence; it also removes an

important check on the opposing advocate.

In Petitioner's case this was clearest at

the penalty phase, when no informed

response was possible to the

prosecution's agressive use of

- 10-

psychiatric testimony. The hamstringing

of Petitioner's lawyer was also made

evident during the trial's guilt stage,

however, when the prosecutor repeatedly

emphasized to the jury that the

psychiatrists had no opinion of the

petitioner's sanity at the time of the

offense, capitalizing on the inference

that since the psychiatrists had no

opinion, the defense was meritless.

Since a decision to deny expert services

to a defendant imposes no corresponding

handicap on the prosecution, similar

distortions of the adversary process will

arise whenever services necessary to the

defense are withheld from defense

- 11 -

counsel. See Saltzburg, A Special Aspect

of Kelevance: Countering Negative

Inferences Associated With the Absence Of

Evidence, 66 CAL.L.REV. 1011 (1978)

- 12-

I I

AN ATTORNEY WITH RESOURCES WHO FAILED TO

INVESTIGATE AN INSANITY DEFENSE ON

PETITIONER'S BEHALF WOULD HAVE PERFORMED

IN A CONSTITUTIONALLY DEFICIENT MANNER.

The evidence against the Petitioner

was overwhelming. It included, among

other things: a 44-page statement given

to the police; an oral admission to a

third party; and the possession, in the

presence of the third party, of property

belonging to the victims. Any lawyer

would have been forced to recognize that

the chances for defending the case on the

theory that the Petitioner did not commit

the acts with which he was charged were,

to say the least, bleak. Cf., Strickland

-13-

v* Washington/ aupxa 52 u s l w at 4571.

On the other hand, the Petitioner's

mental state at his arraignment plainly

suggested a potential insanity defense.

A competency evaluation was ordered sua

■SJ2QHt£. Following that evaluation, a

state psychiatrist recommended that:

Because of the severity of

his mental illness and

because of the intensities

of his rage, his poor

control, his delusions, he

requires a maximum security facility. . .

Throughout his trial, Petitioner received

high doses of a powerful anti-psychotic

medication. Particularly in light of the

state of the factual

the only responsible

unpromising

defenses,

-14-

professional decision for Petitioner's

lawyer to make at that point was to

continue to explore the insanity defense.

The trial lawyer in this case

attempted to do so but was thwarted by

the court. if he had not made the

attempt he might well be found to have

rendered constitutionally ineffective

assistance. Indeed he would have been

vulnerable to the criticism voiced by the

Fifth Circuit in v. AlaJaama, 596

F.2d 11214, 1219 (5th Cir. 1979);

In summary, Davis's

attorneys knew that Davis

had a history of mental

problems, knew that insanity

was his only possible

defense, knew, or thought,

that Davis himself would be

little help in developing

the defense, knew what

possible outside sources

might be developed, and - to

judge from what they said

when they argued for a

continuance - knew that

without some investigation

they had practically no

defense to offer. Still

they made no effort to

investigate or develop the

possible sources of

evidence. This is not a

borderline case; it is a

clear breach of the duty a

defense attorney owes to his client.

Numerous opinions have found counsel

ineffective for failing to explore an

insanity defense. See, e.g., Davis v.

Alabama, supra; United States v. Fesspi .

531 F. 2d 1275 (5th Cir. 1976); G r e e r v .

379 F. 2d 923 (5th Cir. 1967);

Beavers v. JBalkcom, 636 F.2d 114 (5th

-16-

Cir. Unit B 1981); Brennan v.

.Blankenship , 472 F.supp. 149 (D.w.D.va.

1979) . The Sixth Amendment guarantee of

effective assistance of counsel is

undermined as significantly when diligent

counsel are prevented from fulfilling

their role in the adversary process as

when incompetent counsel shirk their

duties. The consequences to "a fair

trial, a trial whose result is reliable"

the test of Strickland v. Washington,

.smLa, 52 USLW at 4570 - are the same.

-17-

I

Ill

THE GENERAL POLICIES WHICH SUPPORT

DOCTRINES OF FINALITY IN THE CRIMINAL LAW

ALSO SUPPORT THE ALLOCATION TO APPOINTED

TRIAL COUNSEL OF THE RESOURCES NECESSARY

TO FULFILL HIS CRITICAL ROLE IN THE

ADVERSARY SYSTEM

Final criminal judgments are

desirable for a number of reasons. They

conserve resources; they promote a sense

of judicial responsibility; they enhance

the educational and deterrent functions

of the criminal law and they provide (at

least in some cases) an opportunity to

begin a process of rehabilitation. See

generally, Bator, Finality in Criminal

Law and Federal Habeas Corpus For State

Prisoners, 76 Harv.L.Rev. 441, 451-453

-18-

(1963) . When a state such as Oklahoma

interprets this Court's opinion in United

States -LSLIjl Smith So. Baldi . 344 U.S.

561 (1953) as sanctioning the uniform

denial of expert psychiatric assistance

in every case it makes the attainment of

these incidents of prompt, final

judgments impossible.

Petitioner's case, is an

illustration. The difficulty is not

simply that the defendant had a

persuasive insanity defense and was

unable to present it; the difficuty is

that Oklahoma has adopted a procedure

which makes it impossible to know whether

a potential defense existed or not.

-19-

Where defense counsel is provided

with the resources necessary for

exploring a defense, an early, final

resolution can be achieved in several

ways. A psychiatric examination may

reveal that no defense exists, or it may

reveal that the defense is so implausible

that legitimate tactical considerations

mandate foregoing it. See, Strickland v.

Washington. supra. It may result in a

defense being presented at trial and

accepted or rejected by the trier of

fact. The Oklahoma approach eliminates

all of these potential means for

resolving a case. It preserves only the

potential for a post hoc analysis which

- 20-

is not only too late but is less reliable

since it is conducted by a reviewing

court inevitably less informed than trial

counsel or the trial jury before whom a

defendant has a right to present his

defense if he chooses.

Even those commentors who take the

most restrictive approach to collateral

attacks on criminal convictions would

permit collateral attacks where the

meaningfulness of the trial process is at

issue. Professor Bator, writing

specifically about the right to counsel;

notes that:

Deprivation of counsel in

cases where the demands of

fairness embodied in the due

process clause call for

- 21-

representation by counsel

is, I submit, precisely the

kind of error which should

deprive a state litigation

of sanctity. It casts doubt

on the meaningfulness of the

process provided by the

state for the resolution of

all the issues in the case:

we cannot say that any

question in the case, state

or federal, has had a fair

and full litigation, for

purposes of finality, if the

defendant is found to

require the assistance of

counsel because in the

circumstances of the case he

was incapable of making an

adequate defense himself.

Bator, supra, at 458.

The interests of the administration of

justice are not served if the states are

allowed to believe that Smith v. Bflldl

permits them to withhold necessary

subsidiary services from defense counsel

- 22-

only to discover that convictions must be

vacated when, during the course of a

collateral attack, impressive exculpatory

psychiatric evidence is generated. Amici

urge this Court to clarify for state

courts and legislatures the fundamental

fact that the guarantee of effective

assistance must be understood to include

not merely the services of an attorney

but of an attorney equipped to fulfill

his or her role as an adversary: equipped

where it is necesary with expert

assistance.

-23-

CONCLUSION

Amici join in supporting

Petitioner's claims that his rights to

due process of law* egual protection of

the laws and compulsory process were

violated. The particular interest of our

organizations, however, is in the

guarantee of effective assistance of

counsel and we have sought in this brief

to emphasis that aspect of Petitioner's

claim.

The reported opinions suggest that

there may be serious deficiencies in the

pretrial preparation of many defense

lawyers. Strazzella, Ineffective

Assistance of Counsel Claims: New Uses,

-24-

New Problems, 19 ARIZ.L.REV. 443 (1977).

These deficiencies ought not to be

aggravated by a grudging attitude towards

the allocation of rescources demonstrably

necessary for a functioning defense.

Empirical research seems to indicate that

just that aggravation is occuring. One

study notes that: "The problems

discussed above have caused several

private attorneys appointed to represent

indigent defendants to simply forego

these necesary services on the assumption

that they are no longer available...

Lawyers have given up any hope of

receiving funds for these necessary

services and believe that, even if

-25-

if requested, they will not be

approved___ " Criminal Defense Technical

Assistance Project, A Study of Defense

Services For Indigent Criminal Defendants

In South Carolina: Analysis and

Recommendations, 39-40 (1981).

Amici urge this Court to state

clearly that the right to effective

assistance of counsel includes the right

to those services necessary for the

fulfillment of counsel's adversary role,

to eliminate whatever confusion may have

survived this Court's opinion in Unitsd

States ex rel. Smith 2L±. Bflldl t SUPISf anc*

to remand this case for a new trial.

-26-

» r« ,

Respectfully submitted,

JAMES M. DOYLE

(Counsel of Record)

RICHARD J. WILSON

-27-

*