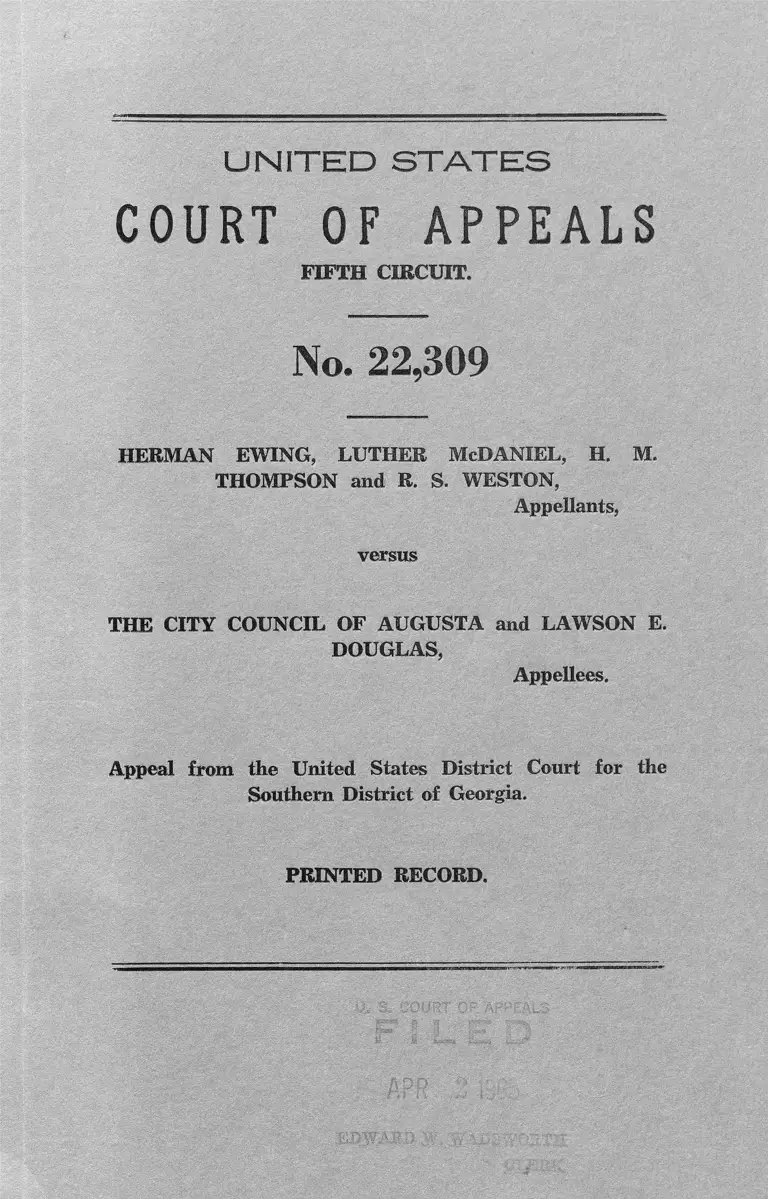

Ewing v. Augusta City Council Printed Record

Public Court Documents

April 2, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ewing v. Augusta City Council Printed Record, 1965. 15230854-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/83b06b60-7cc5-4209-9aaf-1b50f8acc055/ewing-v-augusta-city-council-printed-record. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

UNITED STATES

C O U R T O F A P P E A L S

FIFTH CIRCUIT.

No. 22,309

HERMAN EW ING, LUTHER M cDANIEL, H. M.

THOMPSON and R. S. WESTON,

Appellants,

versus

THE CITY COUNCIL OF AUGUSTA and LAW SON E.

DOUGLAS,

Appellees,

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Georgia.

PRINTED RECORD.

INDEX.

Page

Summons ....................................................................... 1

Complaint .............................................. 3

Exhibit “A”—Agreements between The City

Council of Augusta and Lawson E. Doug

las, March 1, 1952 ................................. 10

Exhibit “A”—Agreement between The City

Council of Augusta and Lawson E.

Douglas, July 12, 1963 ................... 17

Motion for Preliminary Injunction ...................... 21

Motion to Dismiss ........................................................ 23

Letter dated Aug. 21, 1964, to Eugene F. Ed

wards, from Cornelius B. Thurmond, Jr. 24

Motion of Defendant Lawson E. Douglas to Strike

Luther McDaniel as Party Plaintiff for Mis

joinder of Parties .................................. 25

Answer of Defendant Lawson E. Douglas ............ 26

Exhibit “A”—Agreement between The City

Council of Augusta and Lawson E. Douglas 37

Exhibit “B”—Agreement between The City

Council of Augusta and Lawson E. Doug

las, dated June 17, 1960 .......................... 45

Motion to Dismiss of the City Council of Augusta .. 48

Letter dated Aug. 24, to Eugene F. Edwards,

from Samuel C. Waller ............................. 49

Answer to Defendant, the City Council of Augusta 50

Notice to take Depositions ....................................... 53

Deposition of Lawson E. Douglas ............................ 54

Deposition of Mayor George A. Sancken, Jr............... 71

Citation of Authorities in Support of Defendant

Lawson E. Douglas’ Motions .......................... 89

Stipulations ................................................................. ^

Order, that Luther McDaniel be stricken as a party-

Plaintiff on Grounds of Misjoinder and Opinion 103

II

INDEX— (Continued):

Page

Order Dismissing Complaint ..................................... 113

Notice of Appeal ........................ 116

Bond for Costs on Appeal ....................................... 117

Additional Designation of the Record by Defendant 118

Plaintiffs’ Designation of the Record ....................... 119

Clerk’s Certificate ................................................. 120

SUMMONS,

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA—AUGUSTA

DIVISION.

Civil Action File No. 1186.

HERMAN EWING, LUTHER McDANIEL, H. MAU

RICE THOMPSON and R. S, WESTON,

Plaintiffs,

versus

THE CITY COUNCIL OF AUGUSTA and LAWSON E.

DOUGLAS,

Defendants.

To the abovle named Defendants: The City Council of

Augusta and Lawson E. Douglas:

You are hereby summond and required to serve

upon Ruffin and Watkins, 1007 Ninth Street, Augusta,

Ga. and Jack Greenberg and James M. Nabrit III, 10

Columbus Circle, New York, New York, 10019, plain

tiff’s attorney, whose addresses are shown above; an

answer to the complaint which is herewith served

upon you, within Twenty (20) days after service of

this summons upon you, exclusive of the day of serv

ice. If you fail to do so, judgment by default will be

taken against you for the relief demanded in the

complaint.

EUGENE F. EDWARDS,

Clerk of Court,

P. A. BRODIE, JR.,

(Seal of Court) Deputy Clerk.

Date: July 31, 1964.

2

Note.—This summons is issued pursuant to Rule 4

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

Return on Service of Writ.

I hereby certify and return, that on the 4th day of;

August 1964, I received this summons and served it

together with the complaint herein as follows: On

the 4th day of August, 1964 at Augusta, Ga. I served the

within named City Council of Augusta by serving

Mayor George A. Sancken, Jr. personally by hand

ing to and leaving with him a true and correct copy

of this the original.

I certify and return that I further served the within

Writ by serving the within named Lawson E. Douglas

personally by handing to and leaving with him a true

and correct copy of this the original.

This 4th day of August, 1964.

JAMES E. LUCKIE,

United States Marshal,

By RALPH M. TEMPLES,

(Ralph M. Temples),

Deputy United States

Marshal.

Marshal’s Fees

Travel 12 Mi. $1.44

Service 6.00

7.44

3

Subscribed and sworn to before me, a .............. this

. . . . day o f ....................... , 19..........

(Seal)

Filed Aug. 7, 1964.

Note.—Affidavit required only if service is made by

a person other than a United States Marshal or his

Deputy.

COMPLAINT.

Filed July 31, 1964.

(Title Omitted.)

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Title

28, United States Code, Section 1343 (3). This action

is authorized by Title 42, United States Code, Section

1983, to be commenced by any citizen of the United

States or other person within the jurisdiction thereof,

to redress the deprivation under color of a state law,

statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or usage of a

state of rights, privileges and immunities secured by

the Constitution and laws of the United States, to-wit,

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States, Section 1, and Title 42, United States

Code, Section 1981, providing for the equal rights of

citizens and all other persons within the jurisdiction

of the United States.

4

2.

This is a proceeding for a preliminary and a per

manent injunction enjoining the defendants, from en

forcing any law, ordinance, regulation, custom, usage,

tradition and pattern prohibiting Negro citizens and

residents of the City of Augusta, County of Richmond,

State of Georgia, the use and enjoyment of the Mu

nicipal Golf Course and related facilities and pro

grams and denying to them solely because of their

race and color, the right to visit, use and enjoy the

Municipal Golf Course and related facilities and pro

grams on a basis of equality with other citizens of

the City of Augusta.

3.

This is a class action brought by the plaintiffs on

behalf of themselves and other persons similarly situ

ated pursuant to Rule 23 (a) (3) of the Federal Rules;

of Civil Procedure. The class consists of Negro citi

zens of the United States and the State of Georgia'

who reside in the City of Augusta. All members of

the class are similarly affected by the laws, ordi

nances, regulations, customs, usages, traditions and

patterns of racial discrimination by the defendants

which prevent plaintiffs and members of their class

from using and enjoying the Municipal Golf Course

and related facilities and programs without restric

tions based solely upon considerations of race and

color; said persons constitute a class too numerous

to be brought individually before this Court, but there

are common questions of law and fact involved, com

mon grievances arising out of common wrongs and a

common relief is sought for each plaintiff and for

5

each member of the class, as will more fully herein

after appear. The named plaintiffs fairly and ade

quately represent the members of the class on behalf

of which they sue.

4„

The plaintiffs are Negroes and citizens of the United

States and the State of Georgia who are presently

residing in the iCity of Augusta, and, because of their

race and color, are prohibited from using and enjoy

ing the facilities herein set out, which restriction

violates their constitutional rights as set forth else

where herein. Plaintiffs are ready, willing and able

to abide by all rules and regulations of the defend

ants with respect to the use and enjoyment of such

facilities which are applicable alike to all persons

desiring to use and enjoy such facilities.

5.

Defendant The City Council of August is a munic

ipal corporation in the County of Richmond, State of

Georgia and is organized and exists under the laws

of the State of Georgia. Said municipal corporation

is the owner and lessor of the Municipal Golf Course,

and the defendant Lawson E. Douglas is the lessee

of said golf course, a copy of said lease being here

unto attached, and by reference made a part hereof,

and is marked as plaintiffs’ Exhibit “A” .

6.

Plaintiffs show that on July 4, 1964, they presented

themselves at the Municipal Golf Course and were

6

told by the defendant Lawson E. Douglas that they

could not use and enjoy said golf course and related

facilities and programs unless they were either mem

bers or the guests of a member or members. That

plaintiffs returned on the same day with a member

of said golf course, to-wit, Donald Franks. That the

said Donald Franks paid the green fee for himself

and three ̂ members of plaintiffs’ class, whereupon

the said Donald Franks and his guests were given

permission to use and enjoy the said golf course

and related facilities and programs. That the defend

ant Lawson E. Douglas, upon discovering that the

said guests were Negroes, came out and stopped the

said Donald Franks and plaintiffs Herman Ewing,

H. Maurice Thompson, and R. S. Weston from using

and enjoying the said golf course and related facili

ties and programs and ordered them off the premises

and revoked the membership of Donald Franks in

stantly and without notice.

7.

The Municipal Golf Course and related facilities

and programs are still being operated by the de

fendant Lawson E. Douglas who leases from the

defendant The City Council of Augusta, on a racially

segregated basis. Said supervision, operation and

maintenance by the defendants under color of law,

ordinance, regulation, custom, usage, tradition and

pattern constitute a denial of the equal protection

and due process of law guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

7

8.

Plaintiffs and all other Negro residents of the City

of Augusta have been denied the use and enjoyment

of the Municipal Golf Course and related facilities

and programs and have suffered great injury, in

convenience, and humiliation as a result of the denial

to them of their constitutional rights to use and enjoy

the said facilities on an unsegregated basis without

fear or intimidation, and possible arrest, conviction,

fine and/or imprisonment,

9,

Plaintiffs and all other Negro residents of the City

of Augusta are threatened with irreparable injury by

reason of the conditions herein complained of. They

have no plain, adequate or complete remedy at law'

to redress these wrongs and constitutional depriva

tions other than by this suit for an injunction. Any

other remedy would be attended by such uncertainties

and delays as to deny substantial relief and would in

volve a multiplicity of suits and cause further ir

reparable injury, damage and inconvenience to plain

tiffs and all other Negro residents of the City of

Augusta.

Wherefore, plaintiffs pray that:

(1) The Court advance this complaint on the dock

et and order a speedy hearing thereof according to

law, and that upon such hearing the Court enter a pre

liminary injunction to restrain and enjoin the defend

ants and each of them from enforcing any law, ordi

nance, regulation, custom, usage, tradition and pat

8

tern of racial discrimination, pursuant to which plain

tiffs and all other Negro citizens of the City of Augusta

are denied the right and privilege to use and enjoy

the said Municipal Golf Course, on the ground that

such law, ordinance, regulation, custom, usage, tradi

tion and pattern of racial discrimination are violative

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States.

(2) The Court enter a preliminary injunction to

restrain and enjoin the defendants, and each of them,

from denying to plaintiffs, and to those similarly situ

ated, the use and enjoyment of the said Municipal

Golf Course and related facilities and programs under

the direction and administration of the defendants or

either of them, in the same manner and under the

same terms and conditions as white residents of the

City of Augusta.

(3) The Court enter a preliminary injunction to

restrain and enjoin the defendants, and each of them,

from restricting play to members and their guests,

and that no similar limitation be enforced.

(4) The Court, upon a final hearing of this cause,

will enter a permanent injunction similarly enjoining

the defendants, and will

(a) Enter a final judgment and decree that will

declare that the law, ordinance, regulation, custom,

usage, tradition and pattern of racial discrimination

unconstitutional in that they deny to plaintiffs, and

all other Negroes similarly situated, who are citi

zens of the City of Augusta, privileges, and immuni

ties of citizens of the United States, due process of

9

law and equal protection of the laws secured by the

Fourteenth Amendement to the Constitution of the

United States and the rights and privileges secured

to them by the laws made pursuant thereto.

(b) Enter a final judgment and decree enjoining

the defendants and each of them, their agents, serv

ants and employees, from enforcing the aforesaid

discriminatory practices on the ground that they are

unconstitutional.

(c) Enter a final judgment and decree enjoining

the defendants and each of them, their agents, serv

ants and employees from denying to the plaintiffs,

and others similarly situated, the use and enjoyment

of the Municipal Golf Course and related facilities,

and programs under the direction and administra

tion of the defendants, or either of them, in the same

manner and under the same terms and conditions as

white residents of the City of Augusta.

(5) The Court allow plaintiffs a reasonable amount

as attorney’s fees and their costs in this suit.

(6) The plaintiffs have such other and further re

lief as to the Court seems just and proper.

RUFFIN & WATKINS,

By J. H. RUFFIN, JR.,

1007 Ninth Street,

Augusta, Georgia 30903.

JACK GREENBERG,

JAMES M. NABRIT III,

Attorneys for Plaintiffs.

10 Columbus Circle,

New York, New York 10019.

10

Verification.

H. Maurice Thompson, being duly sworn, deposes

and says that he is one of the named plaintiffs in-

this action and that to the best of his knowledge, in

formation and belief all of the matters contained

herein are true.

H. MAURICE THOMPSON.

Sworn to before mje this 31st day of July, 1964.

BESSIE A. DICKERSON,

Notary Public, Richmond

County, Georgia.

My commission expires: 2/2,5/67.

EXHIBIT A.

Agreement.

This Agreement and Lease, made as of the 1st day

of March, 1952, by and between The City Council of

Augusta, a municipal corporation organized and ex

isting under the laws of the State of Georgia, herein

after called Lessor, and Lawson E. Douglas, of the

County of Richmond and State of Georgia, herein

after called the Lessee;

(Witnesseth that the Lessor, for and in consideration

of the sum of Two Thousand Dollars ($2,000.00) per

annum, which is to be paid in the manner herein

after specified, does hereby let and lease to the Les

see, upon the term's and conditions hereinafter stated,

all the following described property, to-wit:

11

All of the Municipal Golf Course of the City of Au

gusta, bounded generally North by Daniel Field;

East by the Wheeless Road and Daniel Field; South

by the Damascus Road; and West by the Damascus:

Road and lands of the Golf Park Apartments; to

gether with the building thereon known as the Golf

Club or Golf Shop, and the equipment used in con

nection with the operation of such golf course, an

inventory of which, duly attested by the signatures

of the Lessor and the Lessee, is hereunto attached,

Marked Exhibit A, and made by< reference a part

of this agreement.

The Terms and Conditions upon which this lease

is made are as follows:

(1) This lease shall begin on the first day of

March, 1952, and shall end on the 31st day of De

cember, 1956, unless sooner terminated in the man

ner hereinafter set out.

(2) The rental to be paid by the Lessee shall be

the sum of Two Thousand Dollars ($2,000.00) per

year, which shall be payable in equal monthly in

stallments of One Hundred and Sixty-six Dollars and

Sixty-six Cents ($166.66) each, payable monthly, in

advance, on the first day of each month, beginning

on the first day of March, 1952.

(3) The Lessor agrees that during the term of this

lease it will furnish the Lessee the water necessary

to operate said golf course, including that necessary

to water the greens and fairways, without charge to*

the Lessee. Lessee shall furnish all other utilities

necessary in connection with the operation of said

12

golf course, in accordance with the terms of this

agreement, at his own expense and without liability

on the part of the Lessor.

(4) The Lessee agrees that during the entire term

of this lease he will maintain said golf course in a

playable condition. He further agrees that during

each calendar year of this lease he will plant not less

than 16,500' pounds of rye grass seed and 300 pounds

of hulled Bermuda seed upon the greens and fair

ways of said golf course, and that during each calen

dar year he will use not less than 25 tons of fair-way

fertilizer (4-8-6 or equal) and 4 tons of Vigoro to

fertilize the same.

Lessee further agrees that he will keep the grass

upon the greens and the grass upon the fairways cut

to the usual requirements of a golf course. He further

agrees that he will take all necessary and proper

steps to control erosion on the entire golf course,

so as to prevent any portion of the leased property

from being damaged by washing or erosion.

Lessee further agrees that the entire length and

width of each fairway and the entire area of each

green on said golf course will be planted with grass

at all times.

(5) Lessee further agrees that he will maintain

the equipment and club house in their present condi

tion, or better, normal wear and tear alone excepted.

(6) Lessee agrees that he will operate said golf

course during the entire term of this lease, accord

ing to the code of ethics and standards which are

13

now and may from time to time hereafter be estab

lished by the Professional Golfers Association.

(7) Lessor and Lessee agree that all monies col

lected by the Lessee from greens fees, memberhips,

club house locker rentals, concessions and all other

sources upon or arising out of the use of such golf

course, during the term of this agreement shall be

the property of the Lessee, and the Lessor shall have

no right or claim to the same so long as the Lessee

carries out his obligations under the terms of this

agreement. !

(8) It is further understood and agreed that

Lessee shall have the right to raise the amounts of

greens fees, membership dues, club house locker

rentals and other charges for the use of said golf,

course, or any of its facilities, when necessary to

meet increased cost of labor and the operation of said

golf course, provided, nevertheless, that Lessee

shall not raise the daily greens fees for the use of

such course to an amount exceeding One Dollar and

Fifty Cents ($1.50) per day on Saturdays, Sundays,

Wednesday afternoons and/or holidays, nor to more

than One Dollar ($1.00) per day on other days, nor

shall Lessee raise the monthly dues for the use of

said golf course and club house abovte the figure of

Seven Dollars and Fifty Cents ($7.50) per month.

(9) The Lessor shall have the right during the

entire term of this lease to make periodic inspec

tions of the equipment hereby leased for the purpose

of determining its condition, and whether or not it is

being maintained in accordance with the terms of

this agreement.

14

(10) Lessee agrees that he will, at his own ex

pense, procure and maintain during the entire term

of this lease a policy of public liability insurance,

with rider attached for the protection of the Lessor

against any/ contingent liability, which policy shall

be in limits of $10,000.00 for one person and $20,000.00

for more than one person. He will also procure and

maintain at his own expense a policy of owner’s,

landlord’s and tenant’s insurance, with rider at

tached for the benefit of the Lessor, which policy

shall be in the sum of $10,000.00.

(11) It is further agreed between Lessor and

Lessee that a Committee from the Municipal Golfers

Association, consisting of three members of that

Association, shall have the right at all times during

the term of this lease to make inspections of the golf!

course and of the golf club house, and the equipment

therein contained, and shall further have the right,

at all times during the term of this lease, to confer

with the Lessee in regard to any improvement neces

sary for the maintenance or operation of said golf

course, or in the maintenance of the same. Said

Committee shall further have the right at all times

during the term of this lease to confer with the Rec

reation Committee of the Council in regard to any

improvements needed on said golf course, or any

recommendations in regard to its maintenance or

operation, or any complaints that they may have in

regard to the maintenance and/or operation of said

golf course, which have not been remedied by the

Lessee after they have conferred with him and given

him a reasonable time to remedy the same.

15

(12) Lessee agrees that contemporaneously with

the signing of this contract he will furnish to the

City Council of Augusta a bond, with good security,

in the amount of $2,000.00, to be approved by the

Mayor and the Finance and Appropriations Commit

tee, conditioned for his faithful performance of all

of his obligations hereunder, including the payment

of the rental hereby reserved, the maintenance of

the golf course and equipment, and the operation of

the same in accordance with this contract, and the

return of the equipment leased hereby in a condition

as good or better than its present condition, ordinary

wear and tear alone excepted.

(13) Should the Lessee fail to perform any of his

obligations under this contract in accordance with

the terms hereof, the Lessor shall have the right,

upon thirty* days’ notice to the Lessee, to declare

this contract null, void and of no effect, and to re

enter and seize all of the property hereby leased, un

less the Lessee shall within such thirty-day period

cure the default existing at the time of such notice.

Any notice given pursuant to this agreement shall

be mailed to the Lessee, by United States Registered

mail, addressed to him at the Club House on the

property, and proof of the delivery of such a regis

tered letter to the Postal authorities of the United

States, so directed to the Lessee and with postage

paid, shall be conclusive evidence of the giving of

such notice. This remedy is cumulative of all of the

other remedies at law or in equity which the Lessor

may have for the enforcement of this contract, and

shall not be the exclusive remedy for such enforce

ment.

16

(14) Should the Lessee default in the performance

of any of the terms of this contract, and should the

Lessor elect either to terminate or not to terminate

this agreement, Lessor shall nevertheless forthwith

have an action at law or in equity, whichever is most

appropriate and expeditious, against both the Lessee

and the surety on his bond for any loss or damage

which the Lessor may have suffered by reason of

such default.

In Witness Whereof, the Lessor has caused these

presents to be executed by its Mayor and attested

by its Clerk of Council, pursuant to resolution duly

adopted on the 3rd day of March, 1952, and the Lessee

has hereunto set his hand and seal, all in duplicate,

and all as of the day and year first above written.

THE CITY COUNCIL OF

AUGUSTA, (L.S.)

By ILLEGIBLE,

(Seal) Mayor,

Attest:

ILLEGIBLE,

Clerk of Council,

Lessor.

Signed, Sealed and Delivered in the presence of:

VERLA L. CHOLOST,

Notary Public, Richmond Co.,

Ga.

LAWSON E. DOUGLAS, (L.S.)

Lessee.

17

Signed, Sealed and Delivered in the presence of:

VERLA L. CHOLOST,

ILLEGIBLE,

Notary Public, Richmond Co.,

Ga.

EXHIBIT “A” .

State of Georgia,

Richmond County.

This Agreement, made and entered into this 12th

day of July, 1963, by and between The City Council

of Augusta, a Municipal Corporation organized and

existing under the laws of the. State of Georgia, here

inafter called lessor, and Lawson E. Douglas, of the

County of Richmond and State of Georgia, herein

after called lessee;

Witnesseth, that whereas on May 30, 1956, the

parties hereto entered into a lease agreement cover

ing certain property in the City of Augusta, designat

ed as the “Municipal Golf Course” , as amended

by instrument dated the 17th day of June, 1960, and

said parties are now desirous of further amending

said lease agreement and of extending the term there

of upon certain terms and conditions.

Now, Therefore, the lessor, for and in considera

tion of the annual rental stipulated in said lease

agreement and the performance and discharge by

the lessee of the other obligations of said lease agree

ment, as heretofore amended, and as herein modi

fied, and of the additional obligations, herein as

sumed, and the lessee, for and in consideration of

the benefits accruing to him under said lease agree

18

ment and the extension of the period of said lease,

do hereby agree as follows:

1.

Paragraph numbered 3 of the the said lease and

agreement dated the 30th day of May, 1956 is hereby

amended so as to read as follows:

“The lessor agrees that during the term of this

lease, it will furnish the lessee the water necessary

to operate said golf course, including that necessary

to water the greens and fairways, at a flat and equal

charge per month of $50.00. Lessee shall furnish all

other utilities necessary in connection with the

operation of said golf course, in accordance with

the terms of this agreement, at his own expense, and

without liability on the part of the lessor.”

2.

Said lease is hereby extended for a period ending

on the 31st day of December, 1971, unless sooner

terminated in the manner provided herein and in

said lease agreement.

3.

The lessee agrees to improve the eighteen (18)

fairways on said golf course so as to bring the said

fairways up to the condition to compare with other

courses in and around the City of Augusta, all at

an aggregate, approximate, improvement cost of

$16,000.00 and to improve said, fairways upon the

following schedule:

19

(a) In the year 1963, to improve six (6) fair

ways provided weather conditions are suitable.

(b) In the year 1964, to improve six (6) additional

fairways.

(e) In the year 1965, to improve the remaining

six (6) fairways.

Time is of the essence of this agreement.

4.

The within lease is hereby amended so as to enure

to the benefit of the heirs and assigns of lessee, pro

vided that lessee shall not in life assign this lease

to a third party without prior approval of lessor.

5.

Should the lessee fail to punctually perform any

of his obligations under the said lease agreement as

amended and in accordance with the terms thereof,

lessor shall have the cumulative remedies specified

in paragraph 13 of said lease agreement.

6.

Except as herein expressly modified, all of the

terms, provisions, conditions of said lease agree

ment dated the 30th day of May, 1956 as amended

by instrument dated the 17th day of June, 1960, shall,

remain of full force and effect and said lease as

amended is hereby fully ratified and affirmed.

20

In Witness Whereof, the lessor has caused these

presents to be executed by its Mayor and attested

by its Clerk of Council, pursuant to authority, con

tained in resolution adopted by lessor in its meeting

on the 6th day of May, 1963, and the lessee has here

unto) set his hand and seal, in duplicate originals,

the day and year first above written.

THE CITY COUNCIL OF

Attest:

AUGUSTA,

By ILLEGIBLE,

As Its Mayor,

(Seal)

ILLEGIBLE,

As its Clerk of Council,

Lessor.

Signed, sealed and delivered by Lessor in the pres-

ence of:

ILLEGIBLE,

ILLEGIBLE,

(Seal) Notary Public, Richmond

County, Georgia.

LAWSON E. DOUGLAS, (L.S.)

(Lawson E. Douglas),

Lessee.

Signed, sealed and delivered by Lessee in the pres-

ence of:

GLORIA R. BRYAN,

CORNELIUS B. THURMOND,

JR.,

(Seal) Notary Public, Richmond

County, Georgia.

21

MOTION FO'R PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION.

Filed Jul. 31, 1964.

(Title Omitted.)

Plaintiffs move this Court for a. preliminary in

junction, pending the final disposition of this cause,

and as grounds therefor rely upon the allegations of

their complaint and show the following:

1. Plaintiffs and others similarly situated are be

ing excluded from the Municipal Golf Course solely

because of their race and color.

2. The exclusion of plaintiffs and those similarly

situated is in violation of the due process and equal

protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States.

3. Plaintiffs are irreparably harmed by the de

fendants’ policy and practice of excluding them from

the Municipal Golf 'Course.

4. The issuance of a preliminary injunction here

in will not cause undue inconvenience or loss to the

defendants.

Wherefore, plaintiffs respectfully pray that this

Court advance this cause on the docket and! order

a speedy hearing of this action according to law

and after such hearing enter a preliminary injunc

tion enjoining defendants, and their agents, em

ployees, successors and all persons in active con

cert and participation with them from:

22

1. Enforcing any law, ordinance, regulation,

custom, usage, tradition, and pattern of racial dis

crimination pursuant to which plaintiffs and all other

Negro citizens of the City of Augusta are denied the

right and privilege of using and enjoying the facili

ties of the Municipal Golf Course.

2. Denying to plaintiffs and those similarly sit

uated the use and enjoyment of the Municipal Golf

Course and related facilities and programs under

the direction and administration of the defendants

or either of them in the same manner and under the

same terms and conditions as white residents of the

City of Augusta.

RUFFIN & WATKINS,

By J. H. RUFFIN, JR.,

1007 Ninth Street,

Augusta, Georgia 30903.

JACK GREENBERG,

JAMES M. NABRIT, III,

Attorneys for Plaintiffs.

10 Columbus Circle,

New York, New York 10019.

23

MOTION TO DISMISS.

Filed Aug. 24, 1964.

(Title Omitted.)

Now comes Lawson E. Douglas, one of the defend

ants in the above styled case and moves the Court

as follows:

1.

To dismiss the action because the complaint fails

to state a claim against this defendant upon which

relief can be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

THURMOND, HESTER,

JOLLES & McELMURRAY,

CORNELIUS B. THURMOND,

JR.,

Attorneys for Defendant

Lawson E. Douglas.

Post Office Address:

Southern Finance Building,

Augusta, Georgia.

24

Law Office

Thurmond, Hester, Jolles & McElmurray

(Successors to Sanders, Thurmond, Hester & Jolles)

Southern Finance Building

Augusta, Georgia

August 21, 1964.

Mr. Eugene F. Edwards,

Clerk of Court,

United States District Court for the

Southern District of Georgia,

Augusta Division,

Federal Post Office and Courthouse,

Augusta, Georgia.

In Re: Herman Ewing, et al. vs. The City Council

of Augusta and Lawson E. Douglas, Civil

Action #1186.

Dear Mr. Clerk:

In reference to the above captioned case, you will

please find enclosed herewith on behalf of defendant

Lawson E. Douglas, the following pleadings which

you will please file in said case:

1. Motion to Dismiss.

2. Motion to Strike for Misjoinder of Parties.

3. Answer.

25

Thanking you for your cooperation in this matter,

I am

Very truly yours,

THURMOND, HESTER,

JOLLES & McELMURRAY,

CORNELIUS B. THURMOND,

JR.,

(Cornelius B. Thurmond,

Jr.).

CBT, Jr./grb.

cc: J. H. Ruffin, Jr.,

cc: Mr. Samuel E. Waller.

MOTION OF DEFENDANT LAWSON E. DOUGLAS

TO STRIKE LUTHER McDANIEL AS PARTY

PLAINTIFF FOR MISJOINDER OF PARTIES.

Filed Aug. 25, 1964.

(Title Omitted.)

Now comes Lawson E. Douglas, one of the de

fendants in the above styled case and moves the

Court as follows:

1.

This defendant moves to strike Luther McDaniel as

a party plaintiff on the ground that said complaint

does not allege that said Luther McDaniel has ever

applied for and been refused the use of the Augusta

Golf Course and therefore to join said Luther

McDaniel as a party plaintiff with plaintiffs Herman

26

Ewing, H. Maurice Thompson and R. S. Weston is a

misjoinder of parties.

Respectfully submitted,

THURMOND, HESTER,

JOLLES & McELMURRAY,

By CORNELIUS B. THURMOND,

JR.,

Attorneys for defendant,

Lawson E. Douglas.

Post Office Address:

Southern Finance Building,

Augusta, Georgia.

ANSWER OF DEFENDANT LAWSON E. DOUGLAS.

Filed Aug. 24, 1964.

(Title Omitted.)

Now comes Lawson E. Douglas, one of the defend

ants in the above stated case and files this his An

swer and respectfully shows to the Court:

First Defense.

The complaint fails to state a claim against this

defendant upon which relief can be granted.

Second Defense.

This Court is without jurisdiction over the subject

matter of this complaint because for this Court to

have jurisdiction under Title 28 United States Code,

27

Section 1343 (3), the action complained of must be

State action under color of State Law and the acts

alleged of this defendant Lawson E. Douglas are

the acts of an individual and do not constitute State

action within the meaning of the lav/.

Third Defense.

These plaintiffs are not entitled to maintain a class

action in the absence of allegations and proof that

citizens other than plaintiffs had been excluded from

using the golf course on same or similar grounds as

plaintiffs allege, if such allegations constitute depri

vation of rights, privileges, or immunities secured

to plaintiffs by the Constitution of the United States

within the meaning of the law and under the facts

of this case.

Fourth Defense.

That this defendant is entitled to the rights, priv

ileges and immunities secured by tht Constitution

and Laws of the United States, to-wit, the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States,

Section 1 and Title 42, United States Code Section

1981 providing for the equal rights of citizens and

of all persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States to make and enforce contracts, etc , and that

this defendant as lessee under the Lease Agreement

alleged in the complaint is entitled to operate the

Augusta Golf Course under the terms and conditions

of his said lease, the same which does not expire until

the 31st day of December, 1971, as his own private

enterprize and business, in a manner and fashion in

accordance with his plans and desires and in ac

28

cordance with the desires of his business customers

and guests.

(a) That reference to Lease Agreement dated the

1st day of March, 1952, (Exhibit “A” to Complaint)

will show that the real estate on which is located the

Augusta Golf Course was leased by The City Council

of Augusta to Lawson E. Douglas from the 1st day

of March, 1952 until the 31st day of December, 1956,

that lessee Douglas would pay an annual rental pay

able monthly in advance and that with the exception

of water, lessee would furnish all utilities, would

maintain the golf course in playable condition, plant

not less than 16,500 pounds of Rye Grass Seed and

300 pounds of hulled Bermuda Seed, use not less

than 25 tons of fairway fertilizer and 4 tons of Vigoro,

take all necessary steps to prevent erosion, main

tain equipment and club house in present condition

or better condition, pay all costs of labor in operation

of the golf course, maintain at his own expense publid

liability insurance, maintain owner’ s, landlord’s and

tenant’s insurance for the benefit of the lessor, fur

nish bond with good security conditioned for the faith

ful performance of his obligations, payment of rental,

maintenance of course and equipment, all of these

things at this defendant’s own expense.

(b) That thereafter by instrument dated the 30th

day of May, 1956, the aforementioned Lease Agree

ment was modified and extended, a copy of said

agreement dated the 30th day of May, 1956 is hereto

attached and marked defendants Exhibit “A” and

that reference to said agreement will show that the

Lease Agreement was extended to the 31st day of

29

December, 1961, all the provisions of the lease dated

the 1st day of March, 1952 were republished and in

addition thereto a paragraph numbered 15 was added,

whereby the lessee was to rearrange holes numbers

10, 11, 12 and 13 so that there would be no joint use

of any fairway for two greens and to provide an

additional safety factor to the players using the golf

course and that lessee would install permanent air

conditioning in the golf shop, all of these at his own

expense.

(c) That thereafter, by instrument dated the 17th

day of June, 1960, a copy of which is hereto' attached

and marked defendants Exhibit “B” , the said Lease

Agreement of May 30, 1956 was extended to the 31st

day of December 1966, and paragraphs 6, 8, 11 and

15 of the lease were eliminated, lessee agreed to re

place the grass upon all the greens with Tifton 328

Grass, to lime, aerate and fertilize the fairways and

to enlarge and improve 12 of the 18 tees in use all at

the approximate improvement cost of $8,000.00, which

cost was to be born by lessee, this defendant.

(d) That thereafter by instrument dated the 12th

day of July, 1963, a copy of which is attached to the

complaint as Exhibit “A” , the said lease was further

amended and extended to the 31st day of December,

1971, the lessor no longer to supply water to the golf

course but the lessee to pay for water in addition

with his other utilities, the lease was amended so as

to enure to the benefit of the heirs and assigns of

lessee and particularly in paragraph 3 thereof, the

lessee (this defendant) agreed to improve the 18 fair

ways at an approximate improvement cost of $16,-

000.00, this to be the sole expense of the said lessee.

30

(e) That in the operation of the golf course, this

defendant has had to purchase much valuable and

expensive equipment, the same consisting of three

tractors, six greens mowers, a pick up truck, four mis

cellaneous mowers, one five section gang-mower, one

three section gang-mower, a fertilizer distributor,

combination fertilizer distributor and seeder, har

rows, edgers, aerating machine, verticut machine,

power sprayer and much miscellaneous equipment

including water hoses, sprinklers, and all the other

necessary small tools and equipment necessary in

the operation of a golf course, all of this equipment

having been purchased with the money of this de

fendant and the title to said equipment being in this

defendant.

(f) That this defendant bears all of the expenses

of operations of said golf course, his latest operating

expense statement being as follows:

Rent and Water ................................. $ 2,400.00

Gas, Oil and Repairs ......................... 2,665.58

Advertising .......................................... 315.00

Utilities ............................................... 1,516.67

Seed, Fertilizer and Supplies ............ 8,990.13

Insurance .............................................. 463.62

Salaries to employees ......................... 12,484.00

Payroll Taxes ....................................... 870.72

Licenses and Taxes .............................. 214.10

Depreciation on equipment ................ 976.35

Total ................................ $30,896.17

(g) That the real estate which this defendant

leases is not contained within premises on which the

31

City Council of Augusta carries on or operates any

of its functions, nor is there contained within said

real estate any facility operated by the said City

Council of Augusta, nor is the operation of the golf

course by this defendant necessary to or dependant

upon the operation by the City Council of Augusta of

any function, but on the contrary, this defendant has

the sole and exclusive use and possession of said

real estate.

(h) That since the 1st day of March, 1952, the

operation of the Augusta Golf Course has been the

sole business enterprize of this defendant, that this

defendant has been solely responsible for the acquisi

tion of equipment to maintain it, responsible for the

maintenance of improvements, responsible for uti

lities, responsible for payment of all labor, all as

shown above, that none of such operation is under

written or supervised in any fashion by the lessor,

that there is no guarantee by anyone that this de

fendant would o*r will make a profit in the operation

of this golf course but on the contrary in the event

that the operation of said golf course should become

unprofitable, that the monetary loss would be the

menetary loss and debt of this defendant and of no

other person, firm, corporation or of The City Coun

cil of Augusta, the other defendant.

Fifth Defense.

That this defendant operates the Augusta Golf

Course as a private club which is not in fact open

to the public but whose membership is genuinely

selective upon the basis that they possess that degree

of physical training and skill to enable them to play

32

golf upon the course with reasonable skill, with the

least fear of harm to others using the golf course

without damaging or abusing the course and with

that mental knowledge and acumen of the rules,

ethics and etiquette of golf necessary to allow one

member or group of members to be compatible com

panions or participants in the use of the golf course

with other members and that these plaintiffs have

not alleged that they possess said physical and men

tal qualifications or that Negroes as a class, who they

allege they represent, possess them.

Sixth Defense.

1.

In answer to paragraph 1 of the complaint, this

defendant admits that the provisions of the sections

cited of the United States Code and the Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States cited provide

and authorize certain actions and confers jurisdiction

upon United States District Courts as to the subject

matter contained within said sections and within said

Fourteenth Amendment but except as herein admit

ted, the allegations of said paragraph 1 as they are.

alleged to apply to the plaintiffs are conclusions and

are denied.

2.

In answer to paragraph 2 of the complaint, this de

fendant admits that the purpose for which plaintiffs

filed this proceeding is for a preliminary and per

manent injunction enjoining this defendant from pro

33

hibiting the plaintiffs from the use of Augusta Golf

Course (erroneously referred to as Municipal Golf

Course) but except as herein admitted, the allega

tions of said paragraph 2 as they apply to the plain

tiffs are conclusions and are denied.

3.

In answer to paragraph 3 of the complaint, this

defendant admits that Rule 23 (a) 3 of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure pertains to class actions,

admits that the Negro citizens of the United States

and the State of Georgia who reside in the City of

Augusta would constitute a class under some cir

cumstances but except as herein admitted, the al

legations of paragraph 3 as they relate to these plain

tiffs and as they relate to Negro citizens as a class

are conclusions and are denied.

4.

In answer to paragraph 4 of the complaint, this de

fendant admits upon information and belief that plain

tiffs are Negroes and citizens of the United States and

the State of Georgia who are presently residing in the

City of Augusta but except as herein admitted, para

graph 4 of the complaint is denied and for answer,

this defendant shows that the plaintiffs Herman

Ewing, H. Maurice Thompson and R. S. Weston were

prohibited by this defendant solely from using the

Augusta Golf Course because the Augusta Golf

Course is a private business club and has a member

ship roster of sufficient number and quantity so that

the playing capacity of said golf course is already

over-taxed and over-extended and for the Augusta1

34

Golf Course to take on plaintiffs as new members

would prevent some of the present members from

using the said golf course for which they have al

ready paid their membership dues; further, that

there existed on and prior to July 4, 1964. and at

present, the situation that because of the large num

ber of the present members, the course was and

is customarily crowded, making it on many occas-

sions difficult and unpleasant for the present mem

bers to use the said course so as to enjoy it in the

manner and at the time which it would be their desire

to so use and enjoy same.

5.

In answer to paragraph 5 of the complaint, this de

fendant admits all of said allegations with the ex

ception of the allegation that a copy of said lease is

attached as Exhibit “ A” to the complaint because

the Lease Agreement actually consists of that lease

dated March 1, 1952 and the amendment dated July

12, 1963, both of which are attached to the complaint,

and in addition thereto, two additional amendments

dated May 30, 1956 and June 17, 1960, which are here

to attached as this defendants Exhibits “A” and “B”

respectively.

6,

In answer to paragraph 6 of this complaint, this de

fendant denies that plaintiffs did on July 4, 1964 pre

sent themselves at the Augusta Golf Course and says

that on said July 4, 1964, three of said plaintiffs, to-wit,

the plaintiffs Ewing, Thompson and Weston applied

35

to his defendant to play golf, but did not apply to

use related facilities and programs and those three

plaintiffs mentioned were informed that the Augusta

Golf Course was a private club and that they would

not be permitted to play on the golf course unless

they were either members or the guests of a mem

ber. This defendant denies that Donald Franks paid

the Green Fee for himself and three members of

plaintiffs class, but admits that part of the plaintiffs,

to-wit, the plaintiffs, Ewing, Thompson and Weston

did apparently return on the same date with the said

Donald Franks whereupon the said Donald Franks

alone entered the Pro Shop, showed his membership

card and registered in three persons as his guests

but that the said Donald Franks failed and refused

and the said plaintiffs Ewing, Thompson and Weston

failed and refused to enter the Pro Shop and sign the

Guest Register properly and in accord with the regu

lation of this defendant and in as much as this de

fendant had informed plaintiffs Ewing, Thompson

and Weston that this defendant operated the Augus

ta Golf Course as his private business and as a pri

vate club and in as much as neither said plaintiffs

Ewing, Thompson and Weston nor the said Donald

Franks had registered in the Guest Register as re

quired, this defendant requested plaintiffs Ewing,

Thompson and Weston to leave, that said plaintiffs

did leave at this defendants request and because of

the infraction of the rule of this defendant, the mem

bership of the said Donald Franks was revoked and

the said Donald Franks was refunded the unused

portion of his annual membership which he had pre

vious! v purchased, and except as herein admitted

the remaining allegations of paragraph 6 are denied.

36

7.

In answer to paragraph 7 of the complaint this de

fendant admits that he operates a golf course which

is called the Augusta Golf Course and admits that

he leases the real estate on which is located the

Augusta Golf Course from The City Council of Au

gusta but except as herein admitted, denies the re

maining allegations of paragraph 7.

8.

This defendand denies the allegations of para

graph 8 of the complaint.

9.

This defendant denies the allegations of paragraph

9 of the complaint.

This Defendant Demands Trial By Jury.

Wherefore this defendant prays:

(a) For judgment declaring that the complaint

fails to state a claim upon which relief can be granted;

and/or

(b) For judgment that this Court is without juris

diction because said complaint is not one under color

of State Law; and/or

(c) For judgment that the plaintiffs cannot main

tain this action as a class action; and/or

37

(d) That his defenses be sustained and that he

be henceforth discharged without costs.

THURMOND, HESTER,

JOULES & McELMURRAY,

By CORNELIUS B. THURMOND,

JR.,

Attorneys for Defendant,

Lawson E. Douglas.

Post Office Address:

1400 Southern Finance Building,

Augusta, Georgia.

DEFENDANT’S EXHIBIT “ A” .

Agreement.

This Agreement and Lease, made by and between

The City Council of Augusta, a municipal corpora

tion organized and existing under the laws of the

State of Georgia, hereinafter called “Lessor” , and

Lawson E. Douglas, of the County of Richmond and

State of Georgia, hereinafter called the “Lessee” ;

Witnesseth, that the Lessor, for and in considera

tion of the sum of Two Thousand Dollars ($2,000.00)

-per annum, which is to be paid in the manner herein

after specified, does hereby let and lease to the

Lessee, upon the terms and conditions hereinafter

stated, all the following described property, to wit:

All of the Municipal Golf Course of the City of

Augusta, bounded generally North by Daniel Field;

East by the Wheeless Road and Daniel Field; South

by the Damascus Road; and West by the Damascus

38

Road and lands of the Golf Park Apartments; to

gether with the building thereon known as the “ Golf

Club” or “ Golf Shop” , and the equipment used in

connection with the operation of such Golf Course,—

an inventory of which, duly attested by the signa

tures of the Lessor and the Lessee, is attached as

Exhibit “ A” to a former agreement and lease be

tween Lessor and Lessee, dated as of March 1, 952.

The Terms and Conditions upon which this lease

is made are as follows,:

(1) This lease shall begin on the first day of Janu

ary, 1957, and shall end on the 31st day of December,

1961, unless sooner terminated, in the manner here

inafter set out.

(2) The rental to be paid by the Lessee shall be

the sum of Two Thousand Dollars ($2,000.00) per

year, which shall be payable in equal monthly in

stalments of One Hundred and Sixty-Six Dollars and

Sixty-Six Cents ($166.6'6) each, payable monthly, in

advance, on the first day of each month, beginning

on the first day of January, 1957.

(3) The Lessor agrees that during the term of

this lease it will furnish the Lessee the water neces

sary to operate said golf course, including that

necessary to water the greens and fairways, with

out charge to the Lessee. Lessee shall furnish ail

other utilities necessary in connection with the

operation of said golf course, in accordance with

the terms of this agreement, at his own expense,

and without liability on the part of the Lessor.

39

(4) The Lessee agrees that during the entire term

of this lease he will maintain said golf course in a

playable condition. He further agrees that during

each calendar year of this lease he will plant not

less than 16,500 pounds of rye grass seed and 300

pounds of hulled Bermuda seed upon the greens and

fairways of said golf course, and that during each

calendar year he will use not less than 25 tons of

fairway fertilizer (4-3-6 or equal) and 4 tons of Vigoro

to fertilize the same.

Lessee further agrees that he will keep the grass

upon the greens and the grass upon the fairways cut

to the usual requirements of a golf course. He further

agrees that he will take all necessary and proper

steps to control erosion on the entire golf course, so

as to prevent any portion of the lessed property from

being damaged by washing and erosion.

Lessee further agrees that the entire length and

width of each fairway and the entire area of each

green on said golf course will be planted with grass

at all times.

(5) Lessee further agrees that he will maintain

the equipment and Club House in their present con

dition, or better, normal wear and tear alone ex

cepted.

(6) Lessee agrees that he will operate said golf

course during the entire term of this lease, accord

ing to the code of ethics and standards which are

now and may from time to time hereafter be es

tablished by the Professional Golfer’s Association.

40

(7) Lessor and Lessee agree that all monies col

lected by the Lessee from greens fees, memberships,

club house locker rentals, concessions and all other

sources upon or arising out of the use of such golf

course, during the term of this agreement shall be

the property of the Lessee, and the Lessor shall have

no right or claim to the same so long as the Lessee

carries out his obligations under the terms of this

agreement.

(8) It is further understood and agreed that

Lessee shall have the right to raise the amounts

of greens fees, membership dues, club house locker

rentals and other charges for the use of said golf

course, or any of its facilities, when necessary to

meet increased cost of labor and the operation of

said golf course, provided, nevertheless, that Lessee

shall not raise the daily greens fees for the use of

such course to an amount exceeding One Dollar and

Fifty Cents ($1.50) per day on Saturdays, Sundays,

Wednesday afternoons and—or holidays, nor to more

than One Dollar ($1.00) per day on other days, nor

shall Lessee raise the monthly dues for the use of

said golf course and club house above the figure

of Seven Dollars and Fifty Cents ($7.50) per month.

(9) The Lessor shall have the right during the en

tire term of this lease to make periodic inspections

of the equipment hereby leased for the benefit of

determining its condition, and whether or not it is

being maintained in accordance with the terms of

this agreement.

(10) Lessee agrees that he will, at his own expense,

procure and maintain during the entire term of this

41

lease a policy of public liability insurance, with rider

attached for the protection of the Lessor against any

contingent liability, which policy shall be in limits

of $10,000.00 for one person and $20,000.00 for more

than one person. He will also procure and maintain

at his own expense a policy of owner’s, landlord’s

and tenant’s insurance, with rider attached for the

benefit of the Lessor, which policy shall be in the

sum of $10,000.00.

(11) It is further agreed between Lessor and

Lessee that a Committee from the Municipal Golfers

Association, consisting of three members of that As

sociation, shall have the right at all times during

the term of this lease to make inspections of the golf

course and of the golf club house, and the equipment

therein contained, and shall further have the right,

at all times during the term of this lease, to confer

with the Lessee in regard to any Improvement neces

sary for the maintenance or operation of said golf

course, o!r in the maintenance of the same. Said

Committee shall further have the right at all times

during the term of this lease to confer with the Rec

reation Committee of the Council in regard to any

improvements needed on said golf course, or any

recommendations in regard to its maintenance or

operation, or any complaints that they may have in

regard to the maintenance and/or operation of said

golf course, which have not been remedied by the

Lessee after they have conferred with him and given

him a reasonable time to remedy the same.

(12) Lessee agrees that contemporaneously with

the signing of this contract he will furnish to the

City of Augusta a bond, with good surety, in the

42

amount of $2,000.00, to be approved by the Mayor and

the Finance and Appropriations and Charity Com

mittee, conditioned for his faithful performance of

all of his obligations hereunder, including the pay

ment of the rental hereby reserved, the maintenance

of the golf course and equipment, and the operation

of the same in accordance with this contract, and

the return of the equipment leased hereby in a con

dition as good or better than its present condition,

ordinary wear and tear alone excepted.

(13) Should the Lessee fail to perform any of his

obligations under this contract in accordance with

the terms hereof, the Lessor shall have the right

upon thirty days’ notice to the Lessee, to declare

this contract null, void and of no effect, and to re

enter and seize all of the property hereby leased,

unless the Lessee shall within such thirty day period

cure the default existing at the time of such notice.

Any notice given pursuant to this agreement shall be

mailed to the Lessee, by United States Registered

Mail, addressed to him. at the Club House, and upon

the delivery of such a registered letter to the postal

authorities of the United States, so directed to the

Lessee and with the postage paid, shall be conclu

sive evidence of the giving of such notice. This

remedy is cumulative of all of the other remedies

at law or in equity which the Lessor may have for

the enforcement of this contract, and shall not be

the exclusive remedy for such enforcement.

(14) Should the Lessee default in the performance

of any of the terms of this contract, and should the

Lessor elect either to terminate or not to terminate

43

this agreement, Lessor shall nevertheless forthwith

have an action at law or in equity, whichever is most

appropriate and expeditious, against both the Lessee

and the surety on his bond for any loss or damage

which the Lessor may have suffered by reason of

such default.

(15) It is expressly agreed between the parties

hereto that in keeping with a certain communication

of April 2, 1956 to The City Council of Augusta, that

the Lessee herein is to re-arrange holes 10 through

13 as are now laid out at the golf course, so that

there will be no joint use of any fairway for two

greens, and so as to provide an additional safety

factor to the players using said golf course, which

re-arrangement is to be in keeping with a certain

set of plans of prior date now in the Engineer’ s

Office of the City Council of Augusta, Georgia.

Furthermore, that the Lessee agrees to install for

use during the summer of 1956 a permanent air-

conditioning system at the Golf Shop, at the expense

of the Lessee.

The execution of these presents, and the renewal

of the Lease as herein provided, is made upon the

representations of the Lessee to, in good faith, make

the alterations herein set forth expeditiously, so that

the same might be used during at lease a portion of

the summer of 1956 golf season.

In Witness Whereof the Lessor has caused these

presents to be executed by its Mayor and attested

by its Clerk of Council, pursuant to action of The

44

City Council of Augusta in its meeting of April 16,

1956, and the Lessee has hereunto set his hand and

seal, all in duplicated, this 30th day of May, 1956.

THE CITY COUNCIL OF

AUGUSTA (L.S.)

By ILLEGIBLE,

Mayor,

Attest:

ILLEGIBLE,

Clerk of Council,

Lessor,

Signed, Sealed and Delivered by Lessor, in the pres

ence of:

THELMA RABUN,

LOUISE STORY,

(Seal) Notary Public, Richmond

County, Ga.

My Commission Expires August 19, 1958.

LAWSON E. DOUGLAS (L.S.),

Lessee.

Signed, Sealed and Delivered by Lessee, in the

presence of:

VER.LA L. CHOLOST,

ILLEGIBLE P. FULLER,

(Seal) Notary Public, Richmond

Co., Ga.

My Commission expires 11-7-56.

45

DEFENDANT’S EXHIBIT “ B ” .

State of Georgia,

Richmond County.

This Agreement, made and entered into this 17th

day of June, 1960, by and between The City Council

of Augusta, a municipal corporation organized and

existing under the laws of the State of Georgia, here

inafter called Lessor, and Lawson E. Douglas, of

the County of Richmond and State of Georgia, here

inafter called the Lessee:

Witnesseth, that Whereas, on May 30, 1956 the

parties hereto entered into a lease agreement cover

ing certain property in the City of Augusta designat

ed as the “Municipal Golf Course” and said parties

are now desirous of extending the period of said

lease upon certain terms and conditions.

Now, Therefore, the Lessor, for and in considera

tion of the annual rental stipulated in said lease

agreement and the performance and discharge by

the Lessee of the other obligations of said lease agree

ment, except as herein modified, and of the additional

obligations herein assumed, and the Lessee, for

and in consideration of the benefits accruing to him

under said lease agreement and the extension of the

period of said lease, do hereby agree as follows:

(1) Paragraphs six (6), eight (8), eleven (11) and

fifteen (15) of said lease agreement are hereby elim

inated and shall no longer be considered effective

as conditions of the agreement between the parties.

46

(2) Said lease is hereby extended for a period

ending on the 31st day of December, 1966, unless

sooner terminated in the manner provided herein

and in said lease agreement.

(3) The Lessee agrees to replace the grass upon

the present greens with Tifton 328 grass, to ade

quately lime, aerate, and fertilize the fairways and

to enlarge and improve twelve (12) of the tees now in

use, all at an aggregate, approximate, improvement

cost of Eight Thousand Dollars ($8,000.00).

(4) Lessee agrees that work on said improve

ments shall begin immediately and all of said im

provements shall be satisfactorily completed within

twenty (20) months from this date. Time is of the

essence of this agreement.

(5) Should the Lessee fail to punctually perform

any of his obligations under this agreement as here

by amended in accordance with the terms thereof,

the Lessor shall have the cumulative remedies speci

fied in paragraph thirteen (13) of said lease agree

ment.

(6) Except as herein expressly modified, all the

terms, provisions, and conditions of said lease agree

ment dated May 30, 1956 shall remain of full force

and effect.

In Witness Whereof, the Lessor has caused these

presents to be executed by its Mayor and attested

by its Clerk of Council, pursuant to authority con

tained in Resolution adopted by Lessor in its meet

47

ing on May 16, 1960, and the Lessee has hereunto

set his hand and seal, in duplicate, the day and year

first above written.

THE CITY COUNCIL OF

AUGUSTA (

By ILLEGIBLE,

Its Mayor,

Attest:

ILLEGIBLE,

Its Clerk of Council,

Lessor,

Signed, sealed and delivered by Lessor in the pres

ence of:

ILLEGIBLE,

ILLEGIBLE,

(Seal) Notary Public, Richmond

County, Georgia.

ILLEGIBLE, (L.S.),

Lessee.

Signed, sealed and delivered by Lessee in the pres

ence of:

ILLEGIBLE,

ILLEGIBLE,

Notary Public, Richmond

County, Georgia.

Verification.

(Title Omitted.)

Personally appeared before the undersigned at

testing officer, came Lawson E. Douglas, who after

48

being duly sworn deposes and says that he is one

of the Defendants in the above styled case and that

the facts set forth in the within and foregoing An

swer are true and correct to' the best of his knowledge,

information and belief.

LAWSON E. DOUGLAS,

(Lawson E. Douglas).

Sworn to and subscribed before me this 18th day of

August, 1964.

GLORIA R. BRYAN,

(Seal) Notary Public, Richmond

County, Georgia.

MOTION TO DISMISS OF THE CITY COUNCIL OF

AUGUSTA.

Filed Aug. 24, 1964.

(Title Omitted.)

The Defendant, The City Council of Augusta,

moves the Court as follows:

1. To dismiss the action as against it on the ground

that the complaint fails to state a claim against

the said defendant, The City Council of Augusta, up

on which relief can be granted.

Dated August 24, 1964.

(Signed) SAMUEL C. WALLER,

(Samuel C. Waller),

Attorney For Defendant,

The City Council of

Augusta.

909 Marion Building,

Augusta, Georgia.

49

The City Council

of

Augusta, Georgia

Augusta—Richmond County Municipal Building-

August 24, 1964.

Samuel C. Waller

City Attorney

Mr. Eugene F. Edwards, Clerk

United States District Court

Southern District of Georgia

Augusta Division

Federal Post Office and Court House

Augusta, Georgia

Re: Herman Ewing et al. vs. The City Council of Au

gusta and Lawson E. Douglas, Civil Action No.

1186.

Dear Mr. Edwards:

In connection with the above stated case, we en

close herewith the following pleadings being filed on

behalf of the Defendant, The City Council of Augusta:

1. Motion to Dismiss.

2. Answer.

Very sincerely yours,

SAMUEL C. WALLER,

(Samuel 1C. Waller),

City Attorney.

SCW: co

Enclosures.

50

ANSWER OF DEFENDANT, THE CITY COUNCIL

OF AUGUSTA.

Filed Aug. 24, 1964.

(Title Omitted.)

For answer to the Complaint of the Plaintiffs in the

above entitled cause, and subject to its Motion to

Dismiss, the Defendant, The City Council of Augusta,

says:

1. In answer to the first paragraph of the Com

plaint, which is unnumbered, this Defendant admits

that the sections of the United States Code referred to

therein are correctly paraphrased but denies that the

relief authorized by said Code sections is applicable

to this Defendant.

2. In answer to Paragraph No. 2 of the Complaint,

this Defendant admits that the Plaintiffs have set

forth therein the purpose of the proceeding, but denies

that there is in existence in The City of Augusta a

municipal golf course, and further denies the re

maining allegations contained therein.

3. In answer to Paragraph No. 3 of the Complaint,

this Defendant admits that the Plaintiffs are at

tempting to proceed, under the Rule cited therein, as a

class action, but for want of sufficient knowledge or

information, is unable to form a belief as to the truth

of the remaining allegations contained therein.

4. In answer to Paragraph No. 4 of the Complaint,

this Defendant admits, upon information and belief,

51

that the Plaintiffs are Negroes and citizens of the

United States and the State of Georgia and who are

presently residing in the City of Augusta, but for

want of sufficient knowledge or information, is un

able to> form a belief as to the truth of the remaining

allegations contained therein.

5. In answer to Paragraph No. 5 of the Complaint,

this Defendant admits that it is a municipal corpora

tion under the laws of Georgia and that is is the owner

and lessor of certain property formerly known as the

“Municipal Golf Course” and that Lawson E. Douglas

is the lessee thereof, but denies that Exhibit A at

tached thereto constitutes the entire lease agree

ment between it and said lessee, inasmuch as the

lease agreement consists of two additional amend

ments, one dated May 30, 1956, and another dated

June 17, 1960; and except as herein admitted, denies

the remaining allegations contained therein.

6. That in answer to Paragraph No. 6 of the Com

plaint, this Defendant, for want of sufficient knowl

edge or information, is unable to form a belief as to

the truth of the allegations contained therein.

7. That in answer to the Paragraph No. 7 of the

Complaint, this Defendant admits that the property

formerly known as the “Municipal Golf Course” is

still being operated by the Defendant, Lawson E.

Douglas, but for want of sufficient knowledge or in

formation, is unable to form a belief as to the truth

of the remaining allegations contained therein.

8. In answer to Paragraph No. 8 of the Complaint,

this Defendant, for want of sufficient knowledge or

52

information, is unable to form a belief as to the truth

of the allegations contained therein.

9. In answer to Paragraph No. 9 of the Complaint,

this Defendant denies the allegations contained there

in.

Wherefor this Defendant prays judgment that the

Complaint of the Plaintiffs be dismissed with costs

to the Defendants.

Dated 24 day of August, 1964.

SAMUEL C. WALLER,

Attorney for jthe Defendant,

The City Council of Augusta.

909 Marion Building,

Augusta, Georgia.

Affidavit.

State of Georgia,

Richmond County.

Personally appeared before me, an officer duly

authorized to administer oaths, George A. Sancken,

Jr., who, being duly sworn, deposes and says that he

is Mayor of the City Council of Augusta, and as such

is authorized to make this affidavit; that the facts

set forth in the within and foregoing answer are true.

Sworn to and subscribed before me, this 24th day

of August, 1964.

GEORGE A. SANCKEN, JR.

ELIZABETH -KITCHENS,

(Seal) Notary Public, Richmond

County, Georgia.

My Commission expires Mar. 1, 1967.

53

Filed Aug. 31, 1964.

(Title Omitted.)

To: Cornelius B. Thurmond, Jr., Esquire,

Southern Finance Building,

Augusta, Georgia,

and

Samuel C. Waller, Esquire,

Marion Building,

Augusta, Georgia.

Please take notice that the depositions of: Lawson

E. Douglas, Augusta Municipal Golf Course, Augusta,

Georgia; Mayor George A. Sancken, Jr., City-County

Building, Augusta, Georgia will be taken pursuant to

Rule 30, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure upon oral

examination beginning at 2:30 P. M., on September 4,

1964, in the City-County Building, Room 302, Augusta,

Georgia before the Honorable Patricia Boose, Court

Reporter, or before some other officer authorized by

law to administer oaths. The examination will con

tinue from day to day until completed. You are by

means of this notice afforded an opportunity to be

present at the aforesaid time and place and take such

part in the examination as you may desire and as

shall be fit and proper.

54

This 31st day of August, 1964.

J. H. RUFFIN, JR.,

(J. H. Ruffin, Jr.),

J. D. WATKINS,

1007 Ninth Street,

Augusta, Georgia.

JACK GREENBERG,

JAMES M. NABRIT, III.

Attorneys for Plaintiffs.

10 Columbus Circle,

New York, New York.

DEPOSITION OF LAWSON E. DOUGLAS.

(Title Omitted.)

Room 302, City-County Bldg.

Augusta, Georgia.

September 4, 1964.

The following deposition of Lawson E. Douglas was

taken before me at the place and on the date above

stated. The witness was duly sworn and, under oath,

testified as follows:

55

[2] MR. LAWSON E. DOUGLAS, being first duly

sworn, testified:

Examination by Mr. Ruffin:

Mr. Ruffin:

We’d like to state for the purposes of the record that

this deposition is being taken pursuant to Rule 30 of

the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

Q. Would you state your full name for the benefit