Smith v USA Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

March 1, 1977

65 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Smith v USA Jurisdictional Statement, 1977. 432475bb-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/83b98272-9d85-4d66-8895-356f6f914ffe/smith-v-usa-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

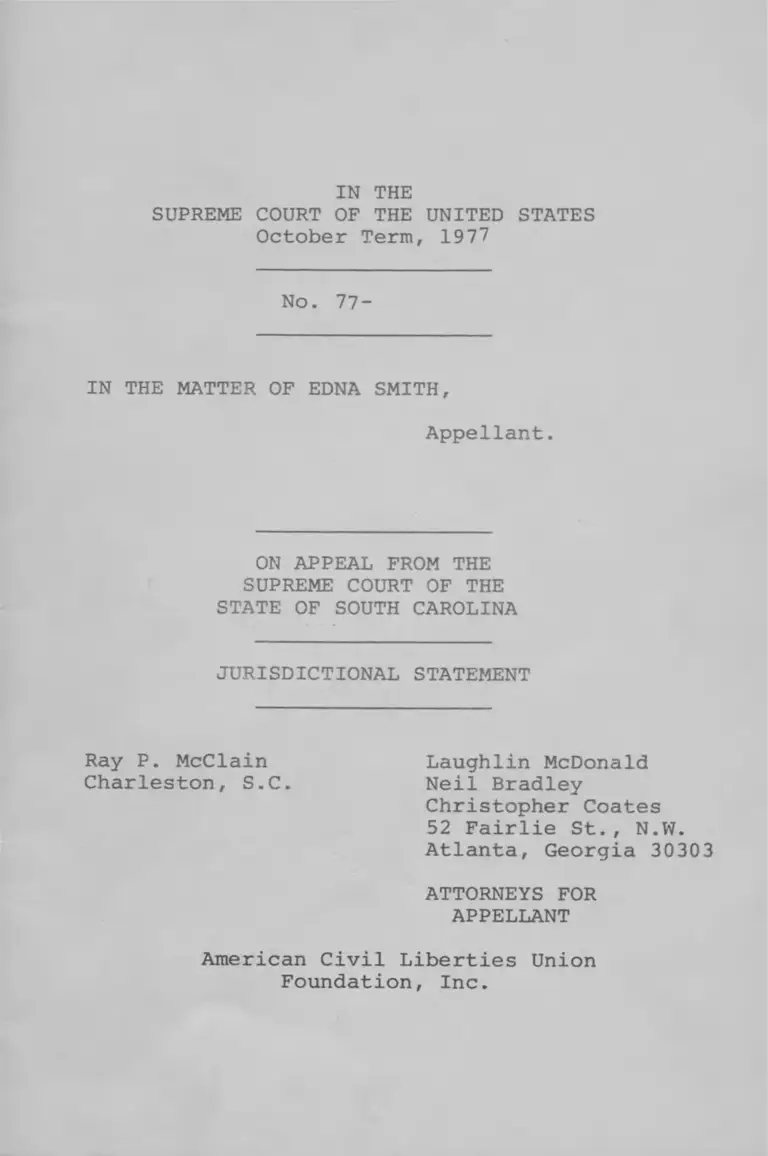

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1977

No. 77-

IN THE MATTER OF EDNA SMITH,

Appellant.

ON APPEAL FROM THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Laughlin McDonald

Neil Bradley

Christopher Coates

52 Fairlie St., N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

ATTORNEYS FOR

APPELLANT

American Civil Liberties Union

Foundation, Inc.

Ray P. McClain

Charleston, S.C.

Page

Jurisdictional Statement.............. 1

Opinions Below........................ 2

Jurisdiction.......................... 3

Constitutional and Statutory

Provisions Involved................ 4

Questions Presented................... 5

Statement of the Case................ 6

The Questions are Substantial......... 10

Conclusion............................ 25

Appendix:

Opinion of the Supreme Court

of South Carolina............... la

Panel Report, Board of Commission

ers on Grievances and Discipline. 15a

Constitutional and Other Provisions

Involved......................... 18a

Complaint before Board of Commis

sioners on Grievances and

Discipline....................... 23a

TABLE OF CONTENTS

l

Page

Notice of Appeal to the Supreme

Court of the United States.... 27a

Order of the United States

Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit................ 28a

n

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Pages

Allen v. School Board of Char

lottesville, 249 F.2d 462 (4th

Cir. 1957)--------------------- 19

American Civil Liberties Union

v. Bozardt, 539 F.2d 340 (4th

Cir. 1976)--------------------- 2

Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan,

372 U.S. 58 (1963)---------- .— 3

Bates v. State Bar of Arizona,

45 U.S.L.W. 4895 (1977)------- 3,5,14,17

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan

County, VA., 321 F.2d 494 (4th

Cir. 1963)--------------------- 19

Belli v. State Bar, 10 Cal3d 824

(1974)------------------------- 18

In re Bloom, 265 S.C. 86, 217

SE2d 143 (1975)--------------- 16

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen

v. Virginia, 377 U.S. 1 (1964)— 20

County School Board v. Thompson,

240 F.2d 59 (4th Cir. 1956)--- 19

Doe v. Pierce, No. 74-475 (D.S.C.

1974)-------------------------- 8, 9, 25

In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967)— 24

In re Griffiths, 413 U.S. 717

(1973)------------------------- 3

Jacoby v. California State Bar,

45 U.S.L.W. 2529 (Ca. 1977)--- 17

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415

(1963)------------------------- passim

In re Ruffalo, 390 U.S. 544 (1968) 5, 24

Thompson v. City of Louisville,

362 U.S. 199 (1960)----------- 5, 24, 25

United Mine Workers v. Illinois

State Bar Association, 389 U.S.

217 (1967)--------------------- 20

iii

Cases Pages

United Transportation Union v.

State Bar of Michigan, 401 U.S.

576 (1971)--------------------- 21

Wolff v. McDonnell, 418 U.S. 539

(1974)---------------------- 24

Other

28 U.S.C. §1257 (2)------------ 3

28 U.S.C. §2103--------------- 5

Civil Rights Attorney's Fees Awards

Act of 1976, 5 U.S. Code Congres

sional & Admin. Nev;s, 5908 (1976)- 20

Disciplinary Rules 2-103(d)- passim

Disciplinary Rules 2-104(A)(2)(5) passim

61 ABA Jo. 464 (1975)--------- 16

Smith, "Canon 2: 'A Lawyer Should

Assist the Legal Profession in its

Duty to Make Legal Counsel Avail

able,'" 48 Tex.L.Rev. 285 (1970)- 16, 23

"3 Carolina Doctors Are Under

Inquiry in Sterilization of Wel

fare Mothers", New York Times,

July 22, 1973, p. 30---------- 7

IV

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1977

In the Matter of )

)Edna Smith, )

)________Appellant. )

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Appellant appeals from the order of the Supreme Court of South Carolina entered

March 17, 1977, which order publicly repri

manded appellant for allegedly unethical

conduct. This disciplinary proceeding against

a member of the bar of the State of South

Carolina was initiated as an administrative

proceeding. The complaint asserted no juris

dictional statute but only that appellant

committed an "act of misconduct or has indulged

in ... [a] practice which tends to pollute

the administration of justice or to bring

the legal profession or the courts into dis

repute", constituting "solicitation in vio

lation of the Canons of Ethics. 1,1

1. The full complaint and letter on

which the complaint is based are apDended hereto at 23a.

2

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Supreme Court of

South Carolina is reported at S.C. ,

233 S.E.2d 301 (1977), and is appended

hereto at la. The report by a three-member

panel of the Board of Commissioners on

Grievances and Discipline of the Supreme

Court of South Carolina recommending a pri

vate reprimand is unreported and is appended

hereto at 15a. This recommendation was

affirmed and a private reprimand administered

orally on January 9, 1976, by the full Board

of Commissioners.

Appellant, by an action in the federal

district court, attempted to enjoin the dis

ciplinary proceedings ab initio. That action

was dismissed by the district court without

reaching the merits, and the dismissal was

affirroed on appeal by the United States Court

of Appeals, American Civil Liberties Union v.

Bozardt, 539 F.2d 340 (4th Cir. 1976).

Three judges dissented from denial of a peti

tion for rehearing en banc in an unreported

opinion appended hereto at 28a. This Court denied certiorari, U.S. ,97 S.Ct.639 (1976). ---

3

JURISDICTION

A disciplinary complaint was issued

naming appellant as respondent on October

9, 1974, by the Secretary of the Board of

Commissioners on Grievances and Discipline

of the South Carolina Supreme Court. On

January 9, 1976, the Board issued a private

reprimand to appellant. Acting on appellant's

petition to expunge the private reprimand,

and with no cross-petition to increase the

punishment, the Supreme Court of South Caro

lina, sua sponte, administered a public

reprimand to appellant on March 17, 1977.

Appellant had defended the allegations

against her on the grounds that she was en

gaged in constitutionally protected free

speech and associational activities and that

the procedures denied her due process of law.

The Supreme Court of South Carolina issued the

public reprimand construing certain Disciplinary

Rules to apply to her conduct and holding the

Rules and the procedures by which punishment

was rendered to be constitutionally valid as applied to appellant.

A notice of appeal was filed in the

Supreme Court of South Carolina on April 15,

1977. 27a. By order dated June 15, 1977, the

Chief Justice extended the time for docketing this appeal through July 11, 1977.

This Court has jurisdiction to consider

this appeal by virtue of 28 U.S.C. §1257(2).

The following cases sustain the jurisdiction

of this Court: Bates v. State Bar of Arizona.

45 U.S.L.W. 4895 (1977); In re Griffiths, 413

U.S. 717 (1973); Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan. 372 U.S. 58, 61, n." 3 (1963) .------------------

4

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The constitutional and statutory pro

visions involved in this case are set forth

in full in the appendix, infra, at 18a, as

follows:

United States Constitution,

Amendment One

United States Constitution,

Amendment Fourteen, §1

Supreme Court of South Carolina,

Rule on Disciplinary Procedure, §4

American Bar Association, Code

of Professional Responsibility,

Disciplinary Rule 2-103(D),

adopted by the Supreme Court of

South Carolina

American Bar Association, Code

of Professional Responsibility,

Disciplinary Rule 2-104(a),

adopted by the Supreme Court of South Carolina.

5

QUESTIONS PRESENTED1

I. Whether the disciplinary rules as

construed and applied to appellant are vague

and overbroad and encroach upon first amend

ment associational activity by prohibiting

attorneys from offering the services of the

American Civil Liberties Union.

II. Whether the decision is in conflict

with NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963),

and subsequent cases, which held that collec

tive activity to assure meaningful access to

the courts is protected by the first amendment

unless the state demonstrates a compelling

interest in support of the particular narrowly

drawn regulation. Bates v. State Bar of Arizona, 45 U.S.L.W. 4895 (1977).

III. Whether the decision below conflicts

with In re Ruffalo, 390 U.S. 544 (1968), in

that the charges of which the appellant had

notice did not state all the elements of the

violations found after the hearing.

IV. Whether the decision is in conflict

with Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U.S.

199 (1960), in that there was no evidence nor

findings to establish all the elements of the

disciplinary rules found to be violated.

1. To the extent that the questions pre

sented are more properly raised by a petition

for certiorari, appellant requests that these

papers be so treated. 28 U.S.C. §2103.

6

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This matter is a professional disciplinary

proceeding formally initiated on October 9,

1974. The complaint issued by the State Board

of Commissioners on Grievances and Discipline

alleged that appellant had committed "solici

tation in violation of the Canons of Ethics"

by writing a letter on August 30, 1973, which

offered the services of the American Civil

Liberties Union (ACLU). Appellant denied

(and has throughout these proceedings denied)

that she had committed "solicitation" and

alleged other defenses, including the vague

ness of the State rules and the protected

associational character of her conduct.

A panel of the Board of Commissioners

held a hearing on the Complaint on March 20,

1975. The panel filed a report recommending

that appellant be found to have violated the

Canons of Ethics for soliciting a client on

behalf of the ACLU, not on behalf of herself.

The panel recommended a private reprimand as

discipline. After a hearing on January 9,

1976. the Board of Commissioners approved

the panel report and administered the private reprimand.

Appellant petitioned the South Carolina

Supreme Court to review and expunge the pri-

vate reprimand. Review was granted. There

was no cross-petition seeking an increased

penalty, yet on March 17, 1977, the South

Carolina Supreme Court entered its order

adopting the panel report and, sua sponte,

increasing the discipline administered from

a private reprimand to a public reprimand.

7

Appellant is a black woman who was ad

mitted to the South Carolina Bar in September,

1972. She is active in the ACLU of South Carolina.

In 1973, local and national newspapers

reported that certain pregnant mothers on

welfare in Aiken County, South Carolina, most

of whom were black, were being sterilized or

threatened with sterilization as a condition

for continuing to receive Medicaid assistance.

See "3 Carolina Doctors Are Under Inquiry

in Sterilization of Welfare Mothers," New

York Times, July 22, 1973, p. 30. Mr.~lGary

Allen, who was active in a number of community

organizations, knew some of the Medicaid

patients who had been sterilized. A local

organization to which Mr. Allen belonged con

tacted appellant through the South Carolina

Council on Human Rights, a private, non

profit organization, with which appellant was

also associated, to request advice and assis

tance on behalf of the welfare mothers. In

response to the request, appellant went to

Aiken, where she met with Mr. Allen and with

three women who had been sterilized in Aiken

County, including Mrs. Williams, the subject

of the alleged solicitation.

Following the Aiken meeting, appellant

received several telephone calls and a letter

from Mr. Allen, advising her that Mrs. Williams

wished to bring suit, and appellant was re

quested by Mr. Allen to write to Mrs. Williams* 1

1. Mrs. Williams testified that she had

not told Mr. Allen she wanted to bring suit;

however, the uncontradicted testimony of ap

pellant and Mr. Allen was that Mr. Allen had

so advised her, and the tribunals below made

no finding discounting this testimony.

8

In response to this request, appellant

wrote the letter of August 30, 1973, that

is the subject of this proceeding. The

letter contained the following paragraph,

by which appellant was found to have com

mitted "solicitation":

You will probably remember me from

talking with you at Mr. Allen's

office in July about the sterili

zation performed on you. The

American Civil Liberties Union

would like to file a lawsuit on

your behalf for money against the

doctor who performed the operation.

We will be coming to Aiken in the

near future and would like to

explain what is involved so you

can understand what is going on.

Mrs. Williams, shortly after receiving

this letter, went to Dr. Pierce's office for

treatment for her child. Dr. Pierce's

attorney was present, read the letter, and

questioned her about litigation against his

client. Mrs. Williams disclaimed any interest

in a lawsuit, and at the attorney's direction

called appellant from Dr. Pierce's office to

so inform her. Appellant never made any effort

to contact Mrs. Williams further. Two women

subsequently sued Dr. Pierce, Doe v. Pierce,

No. 74-475 (D.S.C. 1974), but neither were

represented by appellant or her associate employed by the ACLU.l 1

1. The letter to Mrs. Williams had been

in the possession of Dr. Pierce's attorney

since August of 1973, and was known to the

South Carolina Assistant Attorney Genera], who

represented other defendants in Doe v. Pierce,

(footnote continued to next page)

9

The factual basis for the public repri

mand issued Petitioner is as follows:

The evidence is inconclusive as to

whether the Respondent solicited

Mrs. Williams on her own.behalf,

but she did solicit Mrs. Williams

on behalf of the ACLU, which would

benefit financially in the event

of successful prosecution of the

suit for money damages. 6a.

[The only way in which the ACLU

would possibly receive financial

benefit would be by receipt of a

court award of attorney's fees.]

This was held to be in violation of two Dis

ciplinary Rules:

(1) Disciplinary Rule 2-103(D), which,

by its terms, solely prohibits an attorney

from "knowingly assist[ing] a person or

organization ... to promote the use of his

services or those of his partners or asso

ciates." There was no finding that appellant

or the ACLU ever promoted the use of her own

(footnote continued from preceding page)

in early April, 1974; however, the Attorney

General did not forward the letter to the Board

on Grievances and Discipline until August 19,

1974, after an attempt to have Doe v. Pierce

dismissed for solicitation proved unsuccessful.

The letter was forwarded by A. Camden Lewis,

an attorney herein and for certain defendants

in Doe v. Pierce.

10

professional services, or those of her associates.

(2) Disciplinary Rule 2-104(A), which,

by its terms, states that an attorney who has

given unsolicited advice "shall not accept

employment resulting from that advice." There

was never even any contention that appellant

or anyone else accepted employment by Mrs. Williams.

Appellant raised the federal questions

of her constitutional defenses in the answer

and amended supplemental answer to the com

plaint. They were raised as exceptions in

the petition for review filed with the State

Supreme Court, pp. 2-3, and as questions pre

sented in the brief on the merits to that

court, pp. 1-2. See also, la-2a.

The Supreme Court of South Carolina found,

by its adoption of the commission report, the

evidence sufficient under the recited rules. This appeal followed.

THE QUESTIONS ARE SUBSTANTIAL

I

The Disciplinary Rules as construed,

and as applied to appellant, are

vague and overbroad in violation of

the First Amendment and the Due Process Clause.

Edna Smith, appellant here, has been dis

ciplined by the South Carolina Supreme Court

for offering, gratis and at the express request

11

of another, the services of the ACLU to a

person whom Ms. Smith had talked with earlier

and whom Ms. Smith believed had a valid cause

of action. Her conduct was wholly consistent

with Canon 2 of the Code of Professional

Rsponsibility,1 and indistinguishable from

the conduct of the attorneys offering the

assistance of the NAACP in NAACP v. Button,

371 U.S. 415 (1963). Instead of taking the

disciplinary rules at their face value and

taking care to avoid trenching on constitu

tionally protected activity, the court below

gave the rules a novel construction far

beyond their obvious meaning and far beyond

the contemplation of those who drafted the

rules. The result is not only to punish ap

pellant for engaging in protected activity

but also to chill citizens in the exercise

of their constitutional rights by putting

lawyers on notice that the disciplinary

rules — their narrow terms notwithstanding—

can be applied to the most time-honored

traditions of advising citizens of their

rights and of the availability of counsel.

The South Carolina Supreme Court by con

struing the disciplinary rules to cover pro

tected activity, has rendered those rules

necessarily vague and overbroad.

The decision below not only squarely

contradicts this Court's decision in NAACP

v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963), and inflicts 1

1. "A lawyer should assist the legal

profession in fulfilling its duty to make

legal counsel available." See also Discipli

nary Rules 2-104(A)(2).

12

personal obloquy upon appellant; if upheld,

it also threatens to impair the legal

assistance activities on behalf of civil

liberties of the American Civil Liberties

Union and its affiliated organizations. The

ACLU, which is the oldest and largest organi

zation in the nation devoted exclusively to

the cause of civil liberties,1 has for years

stated frankly in The Guide for ACLU Liti

gation, If 5, that:

It is not necessary to await

clients seeking out the Union; it

is often better for the Union to

take the initiative in civil liber

ties cases. NAACP v. Button, 371

U.S. 415 (1963), provides that

organizations need not stand by

while potential litigants forfeit

through ignorance their constitu

tional rights. An organization

with our purposes can thus advise

people that it will handle cases

for them.

The ACLU's opinion of its function is

widely shared. Referring to the activities

of appellant regarding the origin of Doe v.

Pierce, the case subsequently filed on the

Aiken sterilizations, the Honorable Sol Blatt,

Jr., United States District Judge for the

District of South Carolina, made the following 1

1. See NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415,

440, n. 19 (1963).

13

statement at a hearing on September 24, 1974i 1

This Court feels in its posture

of [sic] the American Civil Liber

ties Union has a duty and an obli

gation under the manner in which

it operates to seek out and help

those who it feels are not able to

help themselves, either their lack

of knowledge or lack of funds, the

Court finds no fault with the

situation out of which this suit

arose with the attorneys connected

with the ACLU, m contacting, if

that in fact did happen. . .

(Emphasis supplied.)

Deposition of Mary Roe (Shirley

Brown), Doe v. Pierce, No. 74-475

(D.S.C. 1974)(Sept. 24, 1974, p. 23).

Obviously, if the decision below is sustained,

the ACLU and countless other legal assistance

1. Three judges of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit reached

a similar conclusion, 33a:

The services of ACLU— assisting lay

persons to recognize their legal

rights and making counsel available--

are the very services for which the

individual plaintiff is sought to be

disciplined and they are constitu

tionally protected activities.

14

organizations-*- will be barred from affirma

tively offering assistance to the poor and

untutored. It was precisely the importance

of protecting associational activity to

foster meaningful access to the courts that

guided this Court to the result of NAACP v.

Button, supra, 371 U.S. at 429-31. See,

Bates v. State Bar of Arizona, 45 L.W. 4895,

4902 n. 32 (1977). To affirm summarily this

judgment would be to decide, without plenary

consideration by this Court, that Button is

overruled, in a decision binding upon courts

throughout the nation, and endorsing a most

expansive construction of these Disciplinary

Rules, which have been adopted in most states.

In Button, the NAACP paid modest at

torney's fees to its staff and cooperating

attorneys in connection with desegregation

lawsuits. The organization also sent these

same attorneys to meetings of parents to

encourage desegregation lawsuits. This Court held that activity to be protected, in a

doctrine recently summarized in the Bates

opinion, supra at note 32:

The Court often has recognized

that collective activity under

taken to obtain meaningful access 1

1. The approach adopted in this case

could be applied to the activities of the

National Right to Work Defense Fund; the NAACP

Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc.; the

Mexican-American Legal Defense and Education

Fund; the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund; the

Natural Resources Defense Council; the National

Chamber Litigation Center (U.S. Chamber of

Commerce); the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and

Education Fund; and the Native American Rights Fund, to name only a few.

15

to the courts is protected under

the First Amendment. See United

Transportation Union v. State

Bar of Michigan, 401 U.S. 576,

585 (1971); United Mine Workers v.

Illinois State Bar Ass'n, 389 U.S.

217, 222-224 (1967); Brotherhood

of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia

Bar, 377 U.S. 1, 7 (1964); NAACP

v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 438-440

(1963). It would be difficult to

understand these cases if a law

suit were somehow viewed as an

evil in itself. Underlying them

was the Court's concern that the

aggrieved receive information

regarding their legal rights and

the means of effectuating them.

A. Vagueness. The fundamental error

of the State Court construction is apparent

from the Court's own statement of its findings:

...that [Appellant] had violated

Disciplinary Rules 2-103 (D) (5) (a)

and (c) and 2-104(A)(5) of the Code

of Professional Responsibility by

soliciting a client on behalf of

the American Civil Liberties Union.la.

The State Court expressly declined to find

that appellant had solicited the client on

her own behalf. The prospective client never accepted the offer of assistance.

16

The most thorough examination of the

cited Disciplinary Rules, 18a, will fail to

disclose any provision of either rule that,

on its face, prohibits an attorney from

offering the legal assistance of an organiza

tion. DR 2-103(D) prohibits an attorney from

allowing an organization to promote his own

services — nowhere does it appear that the

Rule prohibits an attorney from offering the

services of an organization, where there is

neither allegation nor proof that the organiza

tion promoted the services of any particular

attorney.^ dr 2-104(A) prohibits an attorney

from accepting employment, with certain excep

tions. It gives no notice whatsoever, much

less the fair notice required for due process

of law, that it prohibits an attorney from

offering the services of an organization to

a person who never employed any counsel.2

1. This section was drafted by the ABA

to regulate group legal services and not the

type organization considered in NAACP v. Button

See, Smith, "Canon 2: "'A Lawyer Should Assist

the Legal Profession in its Duty to Make Legal

Counsel Available.'" 48 Tex.L.Rev. 285, 306-10

(1970). The American Bar Association has sub

stantially rewritten this section so that it

now approves more explicitly the activities of

pre-paid group legal services. 61 ABA Jo. 464

(1975).

2. Again with regard to notice, it should

be pointed out that the ethical strictures on

solicitation had received little enforcement in

South Carolina prior to July, 1975. See, In re

Bloom, 265 S.C. 86, 217 SE2d 143 (1975).

17

The only logical interpretation that

appellant's counsel have been able to place

upon the decision below is that the State

Court adopted a general notion of "solici

tation" that included any offer of legal

services, whether or not specifically pro

hibited by the Disciplinary Rules, and then

looked to DR 2-103(D)(1)-(5) for a definition

of organizations authorized to offer legal

services. If this was the approach below, it

suffered the vice of vagueness on two counts:

(1) the rules did not give fair notice of

the definition of "solicitation" adopted, and

(2) the rules did not give fair notice of the

court's draconian construction of the exemptions.

B. Overbreadth. In Bates v. State Bar

of Arizona, supra, 45 U.S.L.W. at 4903, a bar

disciplinary proceeding, this Court recently

reaffirmed the proper application of the

doctrine of overbreadth as applied to pro

tected (non-commercial) speech:

First Amendment interests are

fragile interests, and a person

who contemplates protected acti

vity might be discouraged by the

in terrorem effect of the statute.

See NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415,433 ( 1963).

Appellant submits that the Supreme Court of

California has adopted the correct standard

as to whether a communication about obtaining

legal services is presumptively protected:

that the communication has any discernable

purpose in addition to attracting business

for the attorney's private law practice.

Jacoby v. California State Bar, 45 U.S.L.W.

18

2529 (Ca. 1977); Belli v. State Bar, 10 CaL3d

824 (1974). Of course, measured by this

standard, appellant's offer of the assistance

of an organization was presumptively protected, and it therefore fell to the state to demon

strate both (1) that the state had a compelling

interest in punishing the communication and

(2) that the statute prohibiting the conduct

was so narrowly drawn as not to be applicable to protected activity.

Instead of narrowly construing its Dis

ciplinary Rules, the State Court construed

them to .prohibit any attorney from offering

the services of any organization that has

either of the following characteristics:

(1) the organization has as a "pri

mary purpose,"1 [here construed' as

any major activity of the organiza

tion] the provision of legal services; and

(2) the organization at any time,

in any proceeding, prays for attor

neys' fees awarded by a court against a defendant.

1. There was testimony in the record to

the effect that the purpose of the ACLU is to

protect civil liberties, and to this end it

engages, as did the NAACP, in Button, in public

education, in legislative lobbying, and in

litigation. The lack of fundamental fairness

in the proceeding below was illustrated by the

treatment of the issue of the purpose of the

(footnote continued to next page)

19

By these tests, the activity in Button,

where the NAACP sent staff attorneys to

meetings of parents to encourage school de

segregation lawsuits, and paid modest fees

to the attorneys for any lawsuits brought,

was not protected.-*- Furthermore, under this 1

(footnote continued from preceding page)

ACLU. The Grievance Board curtailed appel

lant's attempts to describe the purposes of

the ACLU, stating, "I don't think the under

lying purposes of the American Civil Liberties

Union really is germane to this inquirey [sic]

at all." The Board and the Supreme Court,

then, proceeded to rely on their own inter

pretation of the "primary purpose" of the

organization as a crucial element in sustaining disciplinary action.

1. In lawsuits sponsored by the NAACP, whose conduct was sanctioned in Button, at

torneys cooperating with the NAACP had been

praying for court awards of attornev's fees for

years, and the federal courts made such awards

in many suits pending at the time of the Button

decision. See, e.g., Bell v. School Board of

Powhatan County, Va., 321 F.2d 494 (4th Cir.

1963)(en banc). Indeed , the complaints in

County School Board v. Thompson, 240 F.2d 59

(4th Cir. 1956), and Allen v. School Board of

Charlottesville, 249 F.2d 462 (4th Cir. 1957),

both cases sponsored by the NAACP and cited by

this Court in, the Button decision, 371 U.S. at

435, n. 16, had prayed for awards of fees to

the plaintiffs' attorneys. (See Appendices

filed with the Clerk, U.S. Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit.) Congress recently found,

(footnote continued to next page)

20

construction, the rule prohibits attorneys

from accepting referrals of pro bono cases

from the ACLU. A rule that destroys the

ability of private attorneys to offer pro

bono legal services through an organization

plainly contradicts the first amendment.

Compare, NAACP v. Button, supra, 371 U.S.

at 440, n. 19.

II.

The decision below conflicts with

NAACP v. Button in that the state

offered no compelling state interest

to justify punishing appellant for

her associational activity.________

The decision below is squarely and ir

retrievably in conflict with the decision of

this Court in NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415

(1963), as amplified in subsequent decisions.

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia

State Bar, 377 U.S. 1 (1964); United Mine

Workers v. Illinois State Bar Association,

(footnote continued from preceding page)

in considering the "Civil Rights Attorney's

Fees Awards Act of 1976," that:

... fee awards are essential if

the Federal statutes to which S.2278

applies [42 U.S.C. §§1981 et seq.]

are to be fully enforced.... [t]he

effects of such fee awards are an

integral part of the remedies neces

sary to obtain such compliance.

5 U.S. Code Congressional & Admin.

News 5908, 5913 (1976).

21

389 U.S. 217 (1967); United Transportation

Union v. State Bar of Michigan, 401 U.S.

576 (1971). In Button, the NAACP sent its

staff attorneys to meetings for the purpose

of soliciting plaintiffs for civil rights

lawsuits, particularly in school desegrega

tion. The NAACP's purpose was "to secure

the elimination of all racial barriers which

deprive Negro citizens in equal citizenship

rights...." To this end, the NAACP engaged

in education, lobbying and "also devotes much

of its funds and energies to an extensive

program of assisting certain kinds of litiga

tion..." 371 U.S. at 419-420. Ms. Smith was

assisting the ACLU in doing no more. The

only differences from Button are that here

the ACLU is seeking to protect civil liberties,

rather than the NAACP seeking to protect

equal citizenship, and the incident occurred

in South Carolina in the mid-1970's rather

than in Virginia in the early 1960's.

If the State Court's regulation of the

legal profession is to avoid constitutional

infirmity, it must be upon a showing that

the possibility that an attorney may be paid

presents a "serious danger"; or more to the

point, that the regulation is justified by a

compelling state interest. No such factor

was claimed or shown here. Nor, for these

purposes, could even a rational distinction

be drawn between organizations t hat have

litigation as one major activity as opposed

to organizations that do not. Nor has this

Court ever suggested that organizations for

feit the protection of the First Amendment

by availing themselves of remedies provided

by Congress, such as praying, in proper cases,

for court awards of attorney's fees.

22

III

The decision below is squarely in

conflict with In re Ruffalo, 390

U.S. 544 (1968) , in that fair notice

of the charges was not given to ap

pellant, and also in conflict with

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362

U.S. 199 (1960), in that not all

the elements of the cited Disci

plinary Rules were proved or found

by the Court below._________________

A. Elements of the disciplinary

violations.

Appellant was held to have "violated

DR 2-10-3 (D) (5) (a) by attempting to solicit

a client for a non-profit organization which,

as its primary purpose, renders legal ser

vices, where respondent's associate is a

staff counsel for the non-profit organization."

DR 2-104(A)(5) was cited by the court below

as proscribing the seeking, not the acceptance

of employment, 9a. The State Court properly

found that a violation of a particular dis

ciplinary rule was necessary to sustain

discipline. la.

DR 2-104(A) appears to require the fol

lowing elements:

(1) giving unsolicited legal advice

to a layman that he should take

legal action, and

(2) accepting employment as a result

of that advice.

23

No one has claimed appellant did the

latter.1 The former, by itself, is never

proscribed.

Disciplinary Rule 2-103(D) requires the

following elements:

(1) that there be a person or or

ganization that recommends, fur

nishes, or pays for legal services;

and

(2) that the lawyer knowingly

assists that person or organization,

to promote the use of his services

or those of his partners or associates .

Likewise, with respect to DR 2-103 (D),

the complaint did not allege that any organ

ization was promoting the services of any

particular attorney, including appellant or

her associates.

1. But the State Court held that the

latter was not an element: "The seeking of

and not the acceptance of employment is pro

scribed by DR 2-104(A) (5). " This is directly

contrary to all known constructions of DR

2-104(A);•see Smith, supra, at p. 16, n. 1,

48 Tex.L.Rev. at 295. In addition, the court

below did not find that appellant sought

employment for herself or her associates.

24

B. Notice of the elements.

In re Ruffalo, supra, established that

bar disciplinary proceedings are quasi-

criminal in nature, and require fair notice

to the attorney prior to the hearing on the

violation. At a minimum, this would require

specification of the elements of the offenses

alleged. In re Gault, 387 u7s. 1 (1967);

Wolff y. McDonnell, 418 U.S. 539, 564 (1974).

The disciplinary complaint in this matter

never alleged most of the above-stated ele

ments of the Rules found violated, nor did it

refer to either disciplinary rules by number.

It alleged simply that appellant had committed

"solicitation" by sending a letter that offered the services of the ACLU.

With respect to DR 2-104(A)(5), none of

the elements was alleged in the Complaint.

With respect to DR 2-103 (D), there was never

any allegation that the ACLU was promoting

the services of appellant or her associates.

"The charge must be known before the pro

ceedings commence." In re Ruffalo, supra,

390 U.S. at 551. The failure to specify

either the Disciplinary Rules or the elements

thereof prior to the hearing was a fatal

defect.

C. Findings as to each element.

Thompson v. City of Louisville, supra,

362 U.S. at 206, established that it is "a

violation of due process to convict and punish

a man without evidence of his guilt." Here

there is no evidence that appellant accepted

employment, yet she is punished for violating

DR 2-104(A), which requires acceptance as an

25

element. There was no finding that appel

lant or the ACLU promoted her own services

or the services of her associates, as

expressly required by DR 2-103(D); instead,

the State Court found that appellant solici

ted a client "on behalf of the ACLU," 6a.

Under the Thompson case, then, it is clear

that the finding of violations of both dis

ciplinary rules contravened due process

because an essential element of the offenses

was absent from the proofs and the findings.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, this Court

should note probable jurisdiction of this

appeal, or, in the alternative, grant a writ

of certiorari to review the judgment below.

Respectfully submitted,

LAUGHLIN MCDONALD

NEIL BRADLEY

CHRISTOPHER COATES

RAY P. McCLAIN

ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLANT

1. Contrary to the State Court opinion,

3a, appellant's associate, Mr. Buhl, who was

a staff attorney for the ACLU, never repre

sented any plaintiff in Doe v. Pierce.

la

THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA

In The Supreme Court

In The Matter of Edna Smith . . . .Petitioner.

Opinion No. 20386

Filed March 17, 1977

PUBLIC REPRIMAND

Laughlin McDonald, of Atlanta, Georgia; Ray

P. McClain, of Charleston; and Melvin H. Wulf,

of New York, New York, for petitioner.

Attorney General Daniel R. McLeod and Assistant

Attorneys General A. Camden Lewis and Richard

B. Kale, all of Columbia, for respondent.

PER CURIAM: This matter is before the

Court pursuant to an order, issued under Section

34 of the Rule on Disciplinary Procedure,

granting petitioner's request for review of a

private reprimand administered by the Board of

Commissioners on Grievances and Discipline

(Board). Petitioner is a member of the Bar of

this State and the private reprimand was issued

upon findings that she had violated Disciplinary

Rules 2-103 (D)(5) (a) and (c) and 2-104 (A)(5)

of the Code of Professional Responsibility by

soliciting a client on behalf of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

The grounds urged by petitioner defensively

before the Board are basically the same as she

now presents to have the findings and private

reprimand by the Board set aside. These are:

2a

1. Does the record sustain the find

ings of the Board that petitioner

violated the cited provisions of the

Code of Professional Responsibility?

2. Was petitioner's conduct pro

tected by the constitutional guarantees

of freedom of speech and association?

3. Is Rule 4(d) of the South Carolina

Supreme Court's Rule on Disciplinary

Procedure void for vagueness and over

breadth?

4. Did the complaint in this case

give petitioner notice of the charge

as required by due process of law?

5. Does the record sustain the find

ings of the Board that there was no

retaliatory motive on the part of

the office of the Attorney General in

this proceeding?

We are convinced that the record amply sus

tains the finding of the Board that petitioner

violated the Code of Professional Responsibility

and that disciplinary action was required.

While we affirm the findings of the Board that

petitioner was guilty of unethical conduct, we

conclude that the facts and circumstances are

sufficiently aggravated to justify a public,

instead of a private, reprimand. Accordingly,

this opinion will be published in the Reports

of this Court.

This matter was first heard before a Hearing

Panel which filed its report and recommendations

3a

with the Board. The following portions of the

panel report, affirmed by the Board, set forth

the material facts and correctly dispose of

the issues presented in this appeal:

"The Respondent, Edna Smith, is a prac

ticing attorney in Columbia, South Carolina,

having been admitted to the Bar in September

1972. During the period in which the acts

complained of in the complaint occurred,

respondent was an associate in the Carolina

Community Law Firm, in an expense sharing

arrangement with each attorney keeping his

own fees. One of the associate attorneys was

a staff counsel for the ACLU and was a Counsel

of Record in the Pierce case (hereinafter

mentioned). She was also a legal consultant

of the South Carolina Council on Human Rela

tions, from whom she received compensation,

and was an officer of the Columbia Branch of

the ACLU, and was a cooperating attorney with

the ACLU.

"In response to information received

through the South Carolina Council on Human

Relations, she contacted one Gary Allen, in

Aiken, South Carolina, to arrange for her to

talk to people there who had been sterilized.

The meeting was held in Aiken during the month

of July, 1973, at the office of Gary Allen.

Marietta Williams is a Black woman who had

consented to be sterilized by Dr. Clovis

Pierce. At the meeting in Gary Allen's office,

the respondent advised those present, who in

cluded Mrs. Williams and other women who had

been sterilized by Dr. Clovis H. Pierce, of

their legal rights and specifically that they

could bring suit for money damages against

4a

Dr. Pierce. There was no further contact be

tween respondent and Mrs. Williams until Mrs.

Williams received a letter from respondent

dated August 30, 1973. In this letter respon

dent referred to the meeting in Mr. Allen's

office and indicated that the ACLU would like

to file a lawsuit for her for money against

the doctor who performed the operation. This

letter was written on the letterhead of the

Carolina Community Law Firm and signed by her

as attorney-at-law.

"Prior to the institution of this pro

ceeding, a class action entitled Jane Doe and

Mary Roe, on their behalf and on behalf of all

others similarly situated, v. Clovis H. Pierce,

M.D., et al., was commenced in the United States

District Court of South Carolina to declare the

acts of the defendant in violation of the First,

Fourth, Fifth, Eighth, Ninth, Thirteenth and

Fourteenth Amendments of the Constitution, to

enjoin such acts, and for money damages and

attorneys' fees. Respondent contended at a

procedural hearing in that case, Judge Blatt's

ruling in allowing certain questions to be

propounded to a witnesss involving the contact

of the respondent with the witness was res

judicata or acted as a collateral estoppel

against this proceeding, which contention Judge

Chapman dismissed as is hereinafter reflected.

"After the filing of this disciplinary pro

ceeding against the respondent, an action was

brought in the United States District Court of

South Carolina, Columbia Division, to enjoin

the members of the Board of Commissioners on

Grievances and Discipline, individually and as

members of the Board, and the Attorney General

5a

of South Carolina from prosecuting or other

wise processing the complaint in this pro

ceedings. Complaint also prayed for costs,

plus attorneys' fees and a declaration that

the complaint before the Board was in viola

tion of her rights under the First and Four

teenth Amendments. In dismissing the complaint,

on the grounds that the complainant failed to

state facts entitling respondent to Federal intervention, Judge Chapman held:

1 (1) That to be entitled to injunctive

relief against an action pending in a State

Court the plaintiff must not only prove bad

faith and harassment, which was alleged in

this action, but also show that unless res

trained the proceeding would cause grave and

irreparable injury without providing any

reasonable prospect that the State Court would

respect and satisfactorily resolve the consti

tutional issue raised, which was not alleged or proved in the case.

'(2) That Judge Blatt's ruling in Doe

v. Pierce, in regards to allowing questions

as to solicitation, was solely because they

might go to the issue of the appropriateness

of the class action, and was in no way res

judicata or acted as a collateral estoppel

upon the Board or the Supreme Court of South Carolina.'

"The evidence presented indicated that the

ACLU has only entered cases in which substantial

civil liberties questions are involved, and that

contrary to their former practice, they are now

asking for fees, in addition to any damages

that might be awarded to the plaintiffs, and

6a

that they are never reimbursed out of the

damages awarded the plaintiffs.

"The evidence is inconclusive as to whether

the respondent solicited Mrs. Williams on her

own behalf, but she did solicit Mrs. Williams

on behalf of the ACLU, which would benefit fi

nancially in the event of successful prosecution

of the suit for money damages.

"Respondent's contention that her actions

were protected by the First and Fourteenth

Amendments of the United States Constitution

gives us some concern, but the other defenses

are of little merit and will be disposed of first.

"Respondent's contention that Judge Blatt's

ruling in a preliminary hearing in the case

of Jane Doe and Mary Roe v. Clovis H. Pierce,

M.D., et al., is res judicata or operates to

estop the Board of Commissioners on Grievances

and Discipline is patently erroneous. As

stated in Respondent's own Pre-trial Memorandum,

'Under the Doctrine of res judicata a former

judgment operates as a bar against a second

action upon the same cause of action, but in a

later action upon a different cause of action

it operates as an estoppel or conclusive adjudi

cation as to such issues in the second action

as were actually litigated and determined in

the first action. Lorber v. Vista Irrigation

District, 127 F. (2d) 628 (10th Cir. 1942) ,

Exhibitor's Poster Exhange, Inc, v. National

Screen Service Corp. , (2d) 1313 (5th

Cir. 1970). The relevant inquiry into the

application of this doctrine is identity of

7a

parties, subject matter, cause of action and

whether or not the persons against whom es

toppel is asserted had a full and fair opportu

nity for judicial resolution of the said issue.’

In the case before Judge Blatt neither of the

parties to this proceeding were parties, the

subject matter and causes of action were

totally different, and finally the complaint

in this case had no opportunity for judicial

resolution of the issue of solicitation.

"Respondent's contention that the pro

ceedings were initiated in retaliation because

of her race, sex and in violation of the First

and Fourteenth Amendments are not well taken.

While respondent did introduce evidence of

her race, sex and certain of her associational

activities, there is a total lack of proof that

the Board of Commissioners on Grievances and

Discipline or the Attorney General issued the

complaint against her in retaliation. Respondent

properly takes the position that evidence is

particularly suspect when it is procured -by a

party who is acting adversely to the respondent

in other litigation. However, the evidence

here does not bear out her position that the

complaint against her was initiated by the Office

of the Attorney General, and even if it had been

the Attorney General was not acting adversely

to the respondent in other litigation in which

she was a party, as the letter written to Mrs.

Williams came to the attention of the Attorney

General during proceedings in the case of Jane

Doe and Mary Roe v. Pierce.

"Respondent contends that Rule 4 of the

Rules of Disciplinary Procedure of the South

Carolina Supreme Court is vague and overbroad.

8a

Misconduct is defined in Rule 4(b) as violation

of any provision of the Canons of Professional

Ethics as adopted by this Court from time to

time. The Code of Professional Responsibility

of the American Bar Association was adopted by

the South Carolina Supreme Court on March 1,

1973. Canon 2 of the Code of Professional

Responsibility deals specifically with solici

tation. While the complaint may have been

loosely drafted in that violation of Rule 4 (d)

of the South Carolina Disciplinary Rules was

charged, wherein misconduct was defined as

conduct tending to pollute or obstruct the

administration of justice or to bring the

Courts or the legal profession into disrepute,

the specification of the charge was solicita

tion, and the Panel is of the opinion that

violation of any of the disciplinary rules is

such an action as would, at least, bring the

legal profession into disrepute.

"In any event the Panel is of the opinion

that respondent was fully apprised of the

charges against her by the complainant, and

even if she had not been, the proper procedure

would have been by motion to have the complaint

made more definite and certain.

"Discriplinary Rule 2-104 (A) provides:

'(A) A lawyer who has given un

solicited advice to a layman that

he should obtain counsel or take

legal action shall not accept

employment resulting from that

advice, except that:

9a

' (5) If success in asserting rights

or defenses of his client in litiga

tion in the nature of a class action

is dependent upon the joinder of

others, a lawyer may accept, but

shall not seek, employment from those

contacted for the purpose of obtaining their joinder.'

"Here, by respondent's own testimony, she

met with Mrs. Williams in Aiken, gave un

solicited advice as to what her rights were as

she, the respondent, saw them. Then respondent

followed up with her letter of August 30, 1973,

wherein she solicited Mrs. Williams to join in

a class action suit for money damages to be

brought by the ACLU. The seeking of and not

the acceptance of employment is proscribed by DR 2-104 A (5).

"Disciplinary Rule 2-103 D (5) provides:

1(D) A lawyer shall not knowingly

assist a person or organization that

recommends, furnishes, or pays for

legal services to promote the use of

his services or those of his partners

or associates. However, he may co

operate in a dignified manner with

the legal service activities of any

of the following, provided that his

independent professional judgment is

exercised in behalf of his client

without interference or control by

any organization or other person:

10a

'(5) Any other non-profit organiza

tion that recommends, furnishes or

pays for legal services to its members

or beneficiaries, but only in those

instances and to the extent that con

trolling constitutional interpretation

at the time of the rendition of the

service requires the allowance of

such legal service activities, and

only if the following conditions,

unless prohibited by such interpre

tation, are met:

"(a) The primary purpose of such

organizations do not include the

rendition of legal service.

" (c) Such organization does not de

rive a financial benefit from the

rendition of legal service by the

lawyer."'

"Testimony at the hearing established that

one of, if not the primary purpose of the ACLU,

was the rendition of legal services. It was

also set out in respondent's Pre-trial Memoran

dum that the ACLU and its state affiliates on

any given day are involved in several thousand

active cases throughout the country. It is,

also, the policy of the ACLU to ask for attorneys'

fees in their lawsuits, and their fees go into

its central fund and are used among other things

to pay costs and salaries and expenses of staff

attorneys.

11a

"Consequently, the Panel is of the opinion

that the respondent has violated Disciplinary

Rule 2-103 (D)(5)(a)(c) and is therefore guilty of solicitation.

"In the case of NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S.

415, 9 L. Ed. (2d) 405, 83 S. Ct. 328, the

facts revealed that the State of Virginia had

statutory regulations of unethical conduct of

attorneys from 1849, which forbade solicitation

of legal business in the form of 'running' or

'capping'. Prior to 1956 no attempt was made

to proscribe under such regulations the activi

ties of the NAACP, which had been carried on

openly for years. In 1956, however, the Virginia

Legislature amended the Virginia Code by passage

of Chapter 33, forbidding solicitation of legal

business by a 'runner' or 'capper' to include

in the definition of 'runner' or 'capper' an

agent for an individual or organization which

retains a lawyer in connection with an action

to which it is a party and in which it has no

pecuniary right or liability. The Supreme

Court in its decision stated 'the only issue

before us is this constitutionality of Chapter 33, as applied to the NAACP.'

"The final query then is was the solicita

tion protected under the First and Fourteenth

Amendments, as earnestly urged by respondent.

DR 2-103 (D)(5) specifically recognizes the

inherent constitutional problems and provides

for the- same by allowing an attorney to co

operate with the legal service activities of

a 'non-profit organization that recommends,

furnishes, or pays for legal services to its

members or beneficiaries, but only in those

instances, and to the extent that controlling

constitutional interpretation at the time of

12a

the rendition of the services requires the

allowance of such legal service activities,

and only if the following conditions, unless

prohibited by such interpretation, are met....'

Thus, DR 2-103 (D)(5) prohibits solicitation

except where controlling constitutional inter

pretations mandate the allowance of the specific

service. Furthermore, in order for an attorney

to solicit on behalf of a non-profit organiza

tion, the four conditions of DR 2-103 (D) (5)

(a— d) must be met unless application of these

four conditions has, jointly or severally, been

prohibited by controlling constitutional

interpretations.

"The first of the above mentioned four

conditions is that '[t]he primary purpose of

[non-profit] organizations do not include the

rendition of legal services.' The ACLU, the

non-profit organization herein involved, by

its own admission, may have several thousand

lawsuits in progress at any one day and they

classify themselves as private attorneys general.

It follows, therefore, that its primary purpose

is the rendition of legal services. This Panel

has not found, nor has it been furnished with,

any case showing that a state is prohibited,

on constitutional grounds, from regulating

the activities of attorneys' soliciting clients

on behalf of a non-profit organization which

has as one of its primary purposes the rendi

tion of legal services. Respondent relies on

four cases: NAACP v. Button, supra, 371 U.S.

415, 9 L. Ed. (2d) 405, 83 S.Ct. 328; Brother

hood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia, 377

U.S. 1, 12 L.Ed. (2d) 89, 84 S.Ct. 1113; United

Mine Workers v. Illinois Bar Association, 389

13a

U.S. 217, 19 L.Ed. (2d) 426, 88 St.Ct. 353

and United Transportation Union v. State Bar

of Michigan, 401 U.S. 576, 28 L.Ed. (2d) 339,

91 S. Ct. 1076. None of the four non-profit

organizations involved in the above cases, has

as one of its primary purposes, the rendition

of legal services. In NAACP v. Button, the

court addresses itself to the legal services

rendered by the NAACP. However, the court

appears to characterize the NAACP as a politi

cal, rather than legal organization, and depicts

litigation as an adjunct to the overriding

political aims of the organization.

"That the American Bar Association con

sidered the aspect of the NAACP case is obvious

from the fact that the second of the above

conditions allows solicitation where 'the re

commending, furnishing, or paying for legal

services to its members is incidental and

reasonably related to the primary purposes of

such organization.' As pointed out litigation

is the primary purpose of the ACLU; it is not

simply incidental to its primary purpose. This

condition is not constitutionally prohibited,

but is rather constitutionally required by NAACP v. Button.

"In that there is no question but that the

respondent has not violated the second and third

conditions of DR 2-103 (D)(5), there is no need

to question whether they are constitutionally prohibited or not.

"Respondent has, therefore, violated DR

2-103 (D)(5)(a) by attempting to solicit a

client for a non-profit organization which, as

14a

its primary purpose, renders legal services,

where respondent's associate is a staff counsel

for the non-profit organization. If respon

dent 's contention that her actions were pro

tected by the First and Fourteenth Amendments

of the Constitution were upheld, it would

amount to a holding that the pertinent pro

vision of Canon 2 of the Code of Professional

Responsibility was unconstitutional, which we are not prepared to do."

It is therefore ORDERED that petitioner, Edna Smith, be and she hereby is publicly reprimanded.

s/ J. Woodrow Lewis______C.J.

s/ Bruce Littlejohn______A.J.

s/ J.B. Ness_____________ A.J.

s/ Wm. L. Rhodes, Jr. A.J.

s/ George T. Gregory, Jr.A.J.

15a

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA)

)COUNTY OF RICHLAND )

BEFORE THE BOARD

OF COMMISSIONERS

ON GRIEVANCES AND

DISCIPLINE

In the Matter of: )

)John W. Williams, Jr., )

Secretary of the Board )

of Commissioners on )

Grievances and Dis- )

cipline, )

Complainant, )

)-vs- ) PANEL REPORT

)Edna Smith, )

)__________Respondent. )

This proceeding was commenced on or

about the 10th day of October, 1974, by a

Notice and Complaint in which the Respondent

was charged with solicitation in violation

of the Canons of Professional Ethics. Res

pondent answered, denying the charge, and

setting up the following affirmative defenses

1. That her actions were protected by

Canon 2 of the Code of Professional Ethics;

2. That her actions were protected by

the First and Fourteenth Amendments of the

Constitution of the United States;

3. That the Board of Commissioners on

Grievances and Discipline was estopped by

16a

prior proceedings in Doe v. Pierce, No. 74-75,

United States District Court, South Carolina,

and alternatively that such proceedings were

res judicata as to the subject matter in the case;

4. That this proceeding was instituted

in retaliation because of her race, sex and

associational activities with the ACLU, in

violation of the First and Fourteenth Amend

ments of the United States Constitution;

5. That Rule 4 of the Rules of Dis

ciplinary Procedure of the South Carolina

Supreme Court is vague and overbroad.

The matter came on for hearing before

the undersigned panel on the 20th day of

March, 1975, at Columbia, South Carolina.

The Complainant was represented by

Richard B. Kale, Jr., Esquire, Assistant

Attorney General of Columbia, South Carolina.

The Respondent was represented by Laughlin

McDonald, Esquire, ACLU Foundation, Inc.,

Atlanta, Georgia, and Ray P. McClain, Esquire,

Charleston, South Carolina.

The Panel has carefully considered the

evidence and the arguments and briefs of

Counsel, and makes the following Report:

* * *113

In addition to the concern which this

case has given the Panel in its findings with

1. The omitted portion of the panel report

is quoted without chance (with the exception of

adding full citations) in the opinion of the Supreme Court, 3a-14a.

17a

reference to the matter of violation of the

Code of Professional Responsibility, the Panel

has been impressed by the fact that the Res

pondent's activities were neither aggravated

nor widespread. The record before the Panel

does not indicate any continuous activity on

the part of the Respondent, which is pro

hibited by the Canons of Professional Ethics.

The violation as found by the Panel from the

record is isolated to one particular class action.

After considering the entire record, and

after giving the Respondent the benefit of

the doubt, it is the recommendation of the

Panel that the Respondent be given a private reprimand.

Respectfully submitted,

s/ H. Hayne Crum____

s/ Melvin B. McKeown

s/ John B. McCutcheon

Members of Panel.

18a

CONSTITUTIONAL AND OTHER

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION, Amendment One:

Congress shall make no law respecting

an establishment of religion, or pro

hibiting the free exercise thereof; or

abridging the freedom of speech, or of the

press; or the right of the people peaceably

to assemble, and to petition the Government

for a redress of grievances.

UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION, Amendment Fourteen:

Section 1. All persons born or natural

ized in the United States, and subject to the

jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the

United States and of the State wherein they

reside. No State shall make or enforce any

law which shall abridge the privileges or

immunities of citizens of the United States;

nor shall any State deprive any person of

life, liberty, or property, without due

process of law; nor deny to any person within

its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws .-

Supreme Court of South Carolina, Rule on

Disciplinary Procedure, Section 4:

4. Misconduct Defined.

Misconduct, as the term is used herein,

means any one or more of the following:

(a) violation of any provision of the

oath of office taken upon admission to the

practice of law in this State;

(b) violation of any of the Canons of

Professional Ethics as adopted by this Court from time to time;

19a

(c) commission of a crime involving moral turpitude;

(d) conduct tending to pollute or obstruct

the administration of justice or to bring the

courts or the legal profession into disrepute.

(e) emotional or mental stability so un

certain, as in the judgment of ordinary men,

would render a person incapable of exercising

such judgment and discretion as necessary for

the protection of the rights of others and/or

their property or interest in property.

American Bar Association, Code of Professional

Responsibility, adopted by Supreme Court of

South Carolina, Disciplinary Rule 2-103(D):

DR 2-103 Recommendation of Professional Employment.

(D) A lawyer shall not knowingly assist a

person or organization that recommends, fur

nishes, or pays for legal services to promote

the use of his services or those of his

partners or associates. However, he may co

operate in a dignified manner with the legal

service activities of any of the following,

provided that his independent professional

judgment is exercised in behalf of his client

without interference or control by any organi

zation or other person:

(1) A legal aid office or public defender office:

(a) Operated or sponsored by a duly

accredited law school.

(b) Operated or sponsored by a bona

fide non-profit community organization.

20a

(c) Operated or sponsored by a govern

mental agency.

(d) Operated, sponsored, or approved

by a bar association representative of the

general bar of the geographical area in which

the association exists.

(2) A military legal assistance office.

(3) A lawyer referral service ODerated,

sponsored, or approved by a bar association

representative of the general bar of the geo

graphical area in which the association exists.

(4) A bar association representative of

the general bar of the geographical area in

which the association exists.

(5) Any other non-profit organization

that recommends, furnishes, or pays for legal

services to its members or beneficiaries, but

only in those instances and to the extent that

controlling constitutional interpretation at

the time of the rendition of the services re

quires the allowance of such legal service

activities, and only if the following condi

tions, unless prohibited by such interpretation, are met:

(a) The primary purposes of such or

ganization do not include the rendition of legal services.

(b) The recommending, furnishing, or

paying for legal services to its members is

incidental and reasonably related to the

primary purposes of such organization.

(c) Such organization does not derive

a financial benefit from the rendition of

legal services by the lawyer.

21a

(d) The member of beneficiary for whom

the legal services are rendered, and not such

organization, is recognized as the client of

the lawyer in that matter.

American Bar Association, Code of Professional

Responsibility, adopted by Supreme Court of

South Carolina, Disciplinary Rule 2-104:

DR 2-104 - Suggestion of Need of

Legal Services.

(A) A lawyer who has given unsolicited

advice to a layman that he should obtain

counsel or take legal action shall not accept

employment resulting from that advice, except that:

(1) A lawyer may accept employment by

a close friend, relative, former client (if

the advice is germane to the former employ

ment) , or one whom the lawyer reasonably

believes to be a client.

(2) A lawyer may accept employment

that results from his participation in activi

ties designed to educate laymen to recognize

legal problems, to make intelligent selection

of counsel, or to utilize available legal

services if such activities are conducted or

sponsored by any of the offices or organiza

tions enumerated in DR 2-103 (D) (1) through

(5), to the extent and under the conditions

prescribed therein.

(3) A lawyer who is furnished or paid

by any of the offices or organizations enu

merated in DR 2-103 (D) (1), (2), or (5) may

represent a member or beneficiary thereof

22a

to the extent and under the conditions prescribed therein.

(4) Without affecting his right to

accept employment, a lawyer may speak publicly

or write for publication on legal topics so

long as he does not emphasize his own pro

fessional experience or reputation and does

not undertake to give individual advice.

(5) If success in asserting rights or

defenses of his client in litigation in the

nature of a class action is dependent upon

the joinder of others, a lawyer may accept,

but shall not seek, employment from those

contacted for the purpose of obtaining their joinder.

23a

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA )BEFORE THE BOARD OF

)COMMISSIONERS ON

COUNTY OF RICHLAND )GRIEVANCES AND DIS

CIPLINE

In the Matter of: )

)John W. Williams, Secretary )

of the Board of Commissioners )

on Grievances and Discipline, )

)Complainant, )

)vs. ) COMPLAINT

)Edna Smith, )

)___________Respondent. )

Complainant alleges:

I.

The Complainant is the Secretary of the

Board of Commissioners on Grievances and Dis

cipline and a duly licensed attorney in the

State of South Carolina, and the Respondent

is engaged in the practice of lav/ as a duly

licensed attorney who resides or maintains an

office in the County of Richland, State of

South Carolina.

II.

On information and belief the Respondent

committed the following act of misconduct or

has indulged in the following practice which

24a

tends to pollute the administration of justice

or to bring the legal profession or the courts

into disrepute:

A. On or about August 30, 1973, Respon

dent wrote a letter to Mrs. Marietta

Williams of 347 Sumter Street, Aiken,

South Carolina, a copy of which is

attached, by the terms of which Res

pondent informed Mrs. Williams that

"The American Civil Liberties Union

would like to file a lawsuit on your

behalf for money against the doctor

who performed the operation." Com

plainant is informed and believes

that the foregoing constitutes

solicitation in violation of the

Canons of Ethics.

WHEREFORE, Complainant prays that the

Board of Commissioners on Grievances and Dis

cipline consider these allegations and make

such disposition as may be appropriate.

s/ John W. Williams

Complainant

[Verification Omitted]

25a

August 30, 1973

Mrs. Marietta Williams

347 Sumter Street

Aiken, South Carolina • 29801

Dear Mrs. Williams:

You will probably remember me from

talking with you at Mr. Allen's office in

July about the sterilization performed on

you. The American Civil Liberties Union

would like to file a lawsuit on your behalf

for money against the doctor who performed

the operation. We will be coming to Aiken

in the near future and would like to explain

what is involved so you can understand what is going on.

Now I have a question to ask of you.

Would you object to talking to a women's

magazine about the situation in Aiken? The

magazine is doing a feature story on the

whole sterilization problem and wants to talk

to you and others in South Carolina. If you

don't mind doing this, call me collect at

254-8151 on Friday before 5;00, if you receive

this letter in time. Or call me on Tuesday

morning (after Labor Day) collect.

I want to assure you that this inter

view is being done to show what is happening

to women against their wishes, and is not

being done to harm you in any way. But I

want you to decide, so call me collect and

let me know of your decision. This practice

must stop.

26a

About the lawsuit, if you are interested, let me know, and I'll let you know when we

will come down to talk to you about it. We

will be coming to talk to Mrs. Waters at the

same time; she has already asked the American

Civil Liberties Union to file a suit on her behalf.

Sincerely,

s/ Edna Smith

Edna Smith

Attorney-at-Law

27a

[Filed April 15, 1977]

THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA

IN THE SUPREME COURT

In the matter of Edna Smith,

Petitioner.

NOTICE OF APPEAL TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

NOTICE is hereby given that Edna Smith,

the petitioner above-named, hereby appeals to

the Supreme Court of the United States from

the final order imposing discipline on her

entered in this matter on March 17, 1977.

This appeal is taken pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1257(2).

s/ Ray P. McClain

RAY P. McCLAIN

Attorney for Petitioner

28a

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

___________ [Filed April

No. 75-1335 30, 1976]

American Civil Liberties

Union and Jane Koe,

Appellants,

versus

0. Harry Bozardt, Jr., H. Hayne Crum,

Joseph 0. Rogers, Jr., Marion H. Kinon,

Edward M. Royall, II, George F. Coleman,

Robert A. Hammett, Thomas J. Thompson,

Conning B. Gibbs, Jr., Lowell W. Ross,

Frank E. Harrison, J. Malcolm McLendon,

C. Thomas Wyche, William L. Bethea, John

B. McCutcheon, Melvin B. McKeown, Jr.,

individually and as members of the Board

of Commissioners on Grievances and Discipline,

and their successors; and the Attorney

General of South Carolina,

Appellees.

O R D E R

Upon consideration of the petition for

rehearing it is ORDERED, with the consent and

approval of Judge Bryan and Judge Field, that

the petition for rehearing be and the same hereby is denied.

Upon consideration of the suggestion for

a rehearing en banc, a poll of the court having

been requested by a regular active member of

the court, it was established that a majority

29a

of the regular members of the court in

active service did not favor rehearing en banc,

NOW, THEREFORE, IT IS ORDERED that

the suggested rehearing en banc be and the same hereby is denied.

For the court:

s/ Herbert S. Boreman

Senior United States

Circuit Judge.

30a

WINTER, Circuit Judge, dissenting:

I dissent from the denial of rehearing en banc.

This is a classic case for such treat

ment. It presents a question of exceptional

importance, Rule 35(a), F.R.A.P., and there

is substantial reason to conclude that the case is wrongly decided.

I.

The panel holds that the principles set

forth in Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37 (1971)

and its progeny, oust federal jurisdiction of