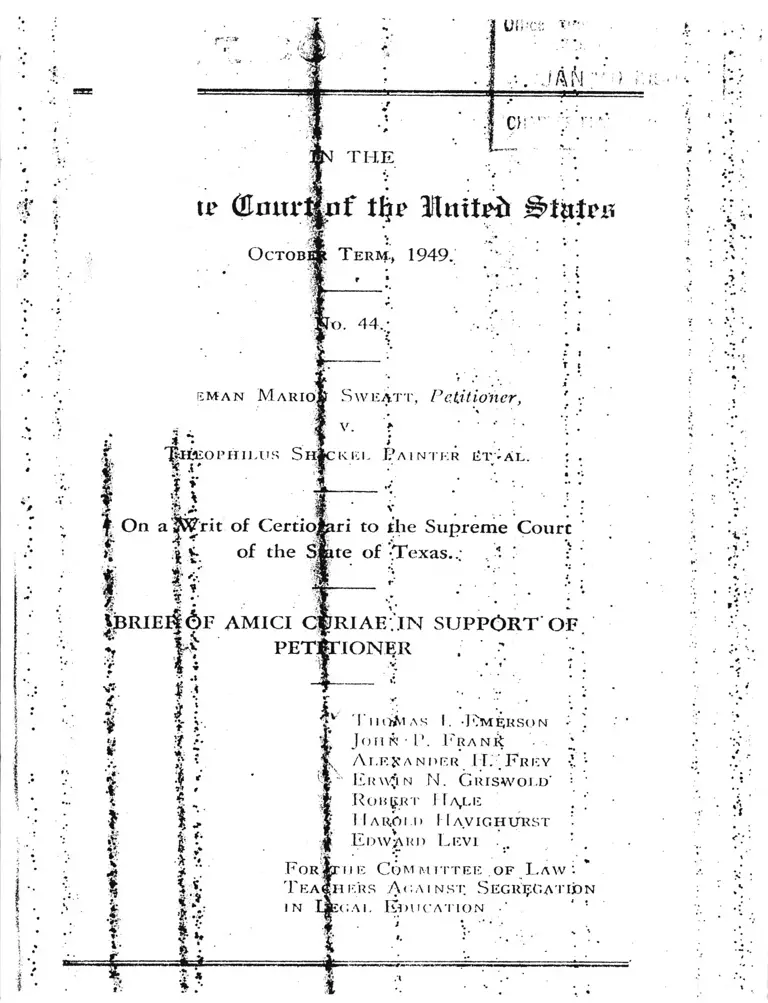

Sweatt v. Painter Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioner

Public Court Documents

January 31, 1950

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sweatt v. Painter Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioner, 1950. 23173b91-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/83fb2eca-9fc7-4853-9a24-13b1f7c97923/sweatt-v-painter-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-petitioner. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

J.»l? «

UH’Cfc v* '

■ .' J A M

T H E

i :

CU '

upremc (Enurfinf tfti' Ultttteii j&iptpn

O ctober T erm., 1949.

No. 44.

: j

t t

» 'T

em an M ario# Svveatt, Petitioner,

„ v *•n ’ • ••

* • ■ z *

fiOPHILUS SHfCKEL F a INTKR ET'AL.

1 .r

| >

I *

1 . .. w \

§: On a jpiTrit of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

\ V* of the Slate of -Texas./

M

f S.V . *

|b r i e i | 6 f A M IC I C f R I A E i n s u p p o r t o f .

" ^ P E T IT IO N E R

€

*

f

s

r

1

%

t.v

»

i <

jf :

.? i

* ?

•&

ft-

2 '

L

n

• > v.

* .•

f A

# -V

i £

= L i

I '

V I iio/vias I. -Emerson • .

x. Jon N • P. F ran it

AI .E JC a NI > E R 11. ‘ F RE Y y !-

F.rw$ n N . G r i s w o i d ' : '

R o b e r t I I a,le . '

I I A R.O I I» II AVIC. H UR ST

E dward L evi ...•

FoRjprriE Co m m it t e e .of L a w '.*

T eaI h icrs A <;a i nSt Segregation

in IjEGAi. Education •' ‘ !

3 r .j

'

•>

̂ *■

i.-

• I .*

• : • •

:k

i

\.

3.V-!

ft,

’fk

t * IN D E X

Statement

Summary of 'Argument......... 5..

Page

1

2

4.

i

"• v*i

Argument ' "• {

J. The Equal Protection -^Clause Was Intended to Outlaw

Segregation ..............i ........... .............................. ................:.......... 4

\ 1. The original meaning of equal protection is incom-

V patible with segregated education........ ...................... 5

2. Contemporary rejection of “ separate but equal” in

V Congress, immediately before and after the Four-

teenth Amendment, represents a judgment incom-

> patible with segregated education.............................;...... 11

.*• 3. In . Railroad Co. V; Brown, this Court early decided

• th&t “ separate” could not be “equal”....................... 18

Plessy v. Ferguson, which undid the Brown case and

the legislative history of equal protection, should be

overruled ........... r................................................................... 20

II. The Basic Policies Underlying the Court’s Approval of

Segregation in Plessy v. Ferguson Have, in the Years

Intervening Since That Decision, Proved to Be Not

] Only -Wholly Erroneous But Seriously Destructive of

•' the Democratic Process in the United States..............:..... 22'A ' •; 1. The judgment of ;ilie Court in Plessy v. Ferguson

:? that direct governfnental action to eliminate segre-

f gjation is ineffective to overcome the prevailing cus-

? tonis of the community has proved to be without

foundation ...........IL......................................................... ........ 23

2. Patterns of segregation have not tended to produce

b harmonious relations between races, as the Court

assumed in Plessy sv. Ferguson, but have increased

■f tensions and become progressively destructive of the

democratic processan the United States................ ........ 29

> 3. This Court has ultimate responsibility, under the

•' Constitution, to review the factual and policy judg

ment of the Texasjlegislature in this situation ...... 32

III. ;-Segregation Should Not’;Be Extended to Education.....: 34

1. 4 he. precedents do jnot uphold segregated education 34

y. 2. Under the rule of Reason created by the precedents,

V segregation is unreasonable........................................ ....... 35

IV. . Equal Facilities for Legal Education Flave Not in Fact

Been. Offered to Sweajft and. Indeed, Segregated Legal

Education Cannot Under Any Circumstances Afford

Equal .Facilities. Heqce Petitioner Has Been Denied

v Equal Protection EverfWithin the Broadest Application

) of Plessy v. Fergusori..............-........................................ . 38

.Concjlrjsion ............................ .*................................. ............................ . 47

'•Appendix A„4„L........................... *........................................................... . 49

11

Index Continued

C IT A T IO N S

Page

C ases *

Baylles v. Curry, 128 111. 287, 21^.^1.^595^(1889) 19

Berea College v. K entucky, 211 U- S ; 45^ (1908)....................... ;U

Buchanan v. W orley , 245 U S- 6° (1917)...........•;...................... . 4

Cm*/ Cases, 109 U. S. 542^ (1883) _

Camming v. Richmond County Bd., 1Jo U.

E x parte Garland, 4 Wall. 333 ( 1867)

528 (1899)....34, 35

...... 14

Liv parte Lranana, ** vvau. \ * ~ 14

£ * * • * * WcC^ * i ritA alC 6f M (.U86P ................ ... ...................35. 59v. H k m /, 333 U. S. 147 (1948)

ffZPZf.UufdftaYesnnl 2(efoct. Term, United States

Supreme Court) ............ .........."TV'To7p

Jones v. Kehrlein, 47 Cal. App. 646 194 R

M cCabe v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa F e ,2 ^ o U . S. lo l ( LJI J

34, 35

55

..................... 31

(1920 ).............---------- 40

(1

M cP herson v. fltarfeer, 146 U. S. 1 (189*'V " o o f 7 ^ 8 ) 3 5 * 30, 40

M issouri ex rel. Games v. Canada, 305 U . S. 331 0 0 ,

M organ v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 (1946 )

N ew Y ork Trust Co. v. Eisner, 256 U. S. 34o (1321)

P erez v. Sharpe, 32 Cal ^11 P 2d 17 ^.948)

Plcssy v. Ferguson,

2d

163 U

711, 198

S. 537

P. 2d 17 (1948).

(1896)........i:.......3, 4, 14,

23

.. 40

20- 1.

39

22

15

25, 29-30, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36,*38

Railroad Co. v. Broum, 17 W all / 445 (1873 W (1M 9 V - ^ 4

Roberts v City o f Boston, 5 Cush. (Mass.) * ( < . v

Sipnel v B d \ f R egents, 332 U. S. 631, ,u5 tfom. 7o,/xer v

̂ H u rst, 333 U. S. 147 ( 1 9 4 8 V . - - ’....."........................

S laughtcr-H ouse Cases, 16 Wall. 36 (1873)...............

Smithv. Alhvright,321 U . S. 649 ( 1944) ........ -........ T"

State v. M cCann 21 U s l 4 4 0 9 3 « ... 39

United States v. t < * d e n e £ r o d u c t s ,S M a S . ^

United States v. H a m s, 106 U. S. 62.) O 88® >

Virginia State Bd. v. Barnett, 319 U.b.

39

11

21

15

624 (1943)........ 33

S t a t u t e s :

Civil Rights Act of 1866,

Civil Rights Act of 1875,

12 St at. 805 (1863)..........

>37 (1 8 6 5 ).........

14 Stat. 27 (1866).

8 Stat. 335 (1875).

Mass.

Rule 1

Rules

1 1

13 Stat.

16 Stat. 3 (1 8 6 9 )..............

Mass. Acts 1845. c. 2 1 4 -

Rules of Civil Procedure (Vernon l.)42)

Bar of Texas, Art. 3, § 1, 1 d ex-

, Texas

of State

Stat. 696

(Vernon 1947)....

8

11

18

11

13

46

IllIndex:; Continued

V .V v :?• Page

M iscellaneous ': \

% *

Kxec. Order 9981, Fed. Reg.}4313 (1948)....................................... 27

103 A. L. It 713.......................4.............. 40

Arfierican Civil Liberties Union, 29th Annual Rep., In The

Shadow of; Fear (1949)....;:............................................................ ;.... 29

Anierican Freeman, The (1§66 )....................... .......................... ...... 13

Association "o£ American Law Schools, Teachers’ Directory

($1949-50 % y ............................t ............................. 41

Co fig. Globe, |38th Cong., IsCSess. (1804)..... ........................7, 11, 12

Coug. Globe”, -39th Cong., 1st; Sess. (1805-6).......... .-...7, 8, 9, 10, 11

Coflg. Globe, 40th Cong., 2d <5ess. (1867).............................................13

Cong. Globe, 4lst Cong., 2 d ‘Sess. (1.870).........'........................... 13

Cotig. Globe, 41st Cong., 3d Sess. (1871).................................... 14, 15

Coug. Globe, 42d Cong., 1st Sess. (1871)..... >... ...................... i— 15

Corig. Globe, 42d Cong., 2d Sess. (1871-2) ...................14, 15, 17

2 dong. Rec., 43d Cong., 1st ;Sess. (1874).......................... 15, 16, 22

3 Cong. Rec., -143d Cong., 2d Sess. (1,875)............:....;............... 17

Garrison, Address, 8 Am. LaW School Rev. 592 (1936)....... 45

Letter of Salihon Chase to Charles Sumner, dated Dec. 14,

1949 ........ .4 ................. .......... .1... ..... .....-.............. ............ ............. ...... 6

letter of Senator Morrill to Charles Sumner, undated (prob.

Oct. or Noy. 1865)............4-....................................... - .....- ...... —.... 8

Letter to Thaddeus Stevens, dated Nov. 1, 1865_................. ...... 7

Massachusetts'Const. Art. Ill' (1780)...... ....................................,L. 9

Maine Const. Art. I, § 3 (1$19)_...._ ............ ................................. 9

: New Hampshire Const. Art. V I (1792)...... ............. ............... ..... 9

NeW York State Comm’n Against Discrimination, 1948 Report

of Progre?s4-........- ............~..-4_.....- ....—....... .......— .......-............ -..... 28

President’s Cojnmission of Higher Education, Higher Educa

tion for American Democracy (1947)...........!..._.................... ...... 37

, Report of President’s Committee on Civil Rights, To Secure

These Rights (1947)...........i ..............t.............................25, 26, 27, 35

Resolution of Providence, R..T., Union League Club (1865) 7

. Seni Rep. No..131, 40th Cong., 2d Sess. (1868).......................... 19

Special Report, Commissioner1; of Education on Condition and

Improvement of Public Schools, Dist. Col., H. R. Exec.

Doc. No. 3t5, 41st Cong., 2d Sess. (1870)................................ 12

United States/Fair Employment Practice Committee, Final

R/eport (1946)....................._..L..............- .............................................. 27

: University of :fTexas, Law School, Catalogue .( Aug. 1, 1948) 42

, University 6f Texas for Negroes, School of Law, Bulletin

(1949-50)- ...:.............................4............. :...............2, 41, 42, 44

• > ;

T reatJses a n d A r t i c l e s : V

Abrams, Race'-►Bias in Housing (1947)............. .......... ................26

Abrams, The Segregation Threat in Housing, 7 Commentary

123 (1949)4................. -......- 4 - ........... ................ - ........................... . 26

4

American Council on Education, Thus Be Their Destiny

American Council on Education, Color, Class and Personality

American Management Association, The Negro Worker

Article,2 U T Institutes Placement Service, 12 Texas Bar Jour

nal 208 (1949)._

■;n

2H

V8

23

Bout well, Reminiscences of Sixty Years (1902)........................

Boyd Some Phases of Educational History in the South Since

Boyer, The Smaller Law Schools, 9 Am. Law School Rev.

1469 (1942)...................................... .................-.................................... '*m

Bowen, Divine White Right (1934) ..--............................................ \

Brubacher, Modern Philosophies of Education (193.3).............

Comment, 56 Yale L. J. 837 (1 9 4 7 )-..... •...................— —»•— —

Commission on Discrimination in Employment New York

State War Council, Breaking Down the Color lane, 32 Man

Curry, Brief Sketch of George Peabody (1898) _ ........- . !

Curti, The Social Ideas of American Educators (193a)....... 36. . •

Dewey, Democracy and Education (1916) .................................... . ' '

Flack, The Fourteenth Amendment (1908).............

Fleming, Documentary History of Reconstruction (1.306) U L

Frasier and Armentrout, An Introduction to Education (3d

ccl 1033) ..................................................................... * * *

Gifford, The Placement of Law Students and Law Graduates,

9 Am. Law School Rev. 1063 (1941)........... -....... .............. :

Gillmor. Can the Negro Hold His Job?. National As^cmt.on ^

for Advancement of Colored People Bull. (Sept. 1.341)......v ;

Grosvenor, 24 New Englander 268 (1865)

Key, Southern Politics (1949)

Kilpatrick (E d .), The Educational Frontier 0 - 3 3 ) ...... -.... -

Knight, The Influence of Reconstruction on Education m the

South (1913)......................................;t ;v7o’n.......................................' o

Lew in, Resolving Social Conflicts ( 1948 ) .................................. - *

Maclver, The More Perfect Union (1948)... ........ -..................'

McPherson, Handbook of Politics for 1868 (1868)

t .

r

V

V

f/«

•f

i

'h

>.

7

V

•4

u

*1- '

0

V

f

Y

‘a

4

( . • •’»

'f

• ..

V

*

i.*.

r/i

■f

£

Vw

*4!

>

.f*

yrf».

*»

4

i -age

Maprfing and Phillibs, Negroes as Neighbors, 13 Common

Sense 134 (1944)4.............../................................................................. 20

May6, Ih e Human;. Problems of an Industrial Civilization

37

M err jam, The Making of Citizens (1931)....................................... 30

Mifier, Thaddeus Stevens (1939)........... ....................... ..................... 10

Mojrjson and Comrriager, The Growth of the American Re

public (1942)........ i ................................ ,....................... ;...;.........................K)

Moyljyn, Selected Li|t of Books for the . Small Paw School

library, 9 Am. Law School Rev. 4 09 (’1939).......................... 12

Murrhy (lid .), The Negro Handbook (1949)............-.................... 23

Myprs and Williams, Education in a Democracy (1942)............. 30

Mytdal, An American Dilemma (1944)........................................... 31

Nason, Life of Henry Wilson (1870)................... .......................... 5

NewlOn, Education for Democracy in Our Time (1939)........... 38

Newman, An Experiment in Industrial Democracy, 22 Oppor

tunity 52 (1944)....:;................................................................................ 28

Northfup, Proving Ground for Pair Employment, 4 Commen

tary 552 (1947).. .1............................ .......................... .................. 28

Note, M9 Col. L. Rev*. 029 (1949)....................................................... 31

Note, -50 Yale L. J. 1059 (1947)................................. 30 31

Note, >8 Yale L. J. 472 (1949)........................................ ................... ’ 31

Ottleyj The Good-Neighbor Policy— At Home, 2 Common

Grohnd 51 (1942^............................................................................... 20

Paterson, The Legal j/Kid Clinic, 21 Tex. L. Rev. 423 (1943) 44

Poundf Social Control Through Law (1942).................................. 40

Rossi, They Did It in St. Louis, 4 Commentary 9 (1947)........ 29

Rossi; Tolerance by L<*w, 195 Harper’s Mag. 458 (1947)........... 28

Rostow, Liberal Education and the Law: Preparing Lawyers

fot* Their Work in Our Society, 35 A . B. A. lour. 020

(1949) ...................... :i ...............................................................1.............44-5

Simon)- Causes and Cure of Discrimination, N. Y . Times May

29, 1949, § 0, p. 1 0 ................................... ........................ ;................. 28

Sumner, Works (1874)........... ............................................................... 0, 8

Sweetland, The CIO apd Negro American, 20 Opportunity 292

O H O .......................1..............„......................... ; ......................... .......... 29

Taylor, Negro Teachers in White Colleges, 05 Sch’l and Soci

ety 369 (1947)........ .,............................... :.........................:.................... 20

Warrtep, The Supreme,;Court in U. S. History (1920)............... 21

Wester-maun, Bet ween- Slavery and Freedom, 50 Am. Hist

Rev. 4 213 (1945).....4........................................................... ................. 4

Williams, The Louisiana Unification Movement in 1873 2 J

So;.' Hist. 349 (19450............ ............................ ................................. 12

Wirth, .Segregation, 13 Encyc. Soc. Sci. 043 (1934).................. 31

“4

r

■] • IN T H E

4

l t

#«pr««tp (fuurtaif tlj? IUmtrii States

* ■*•'• • V-•• • „

v v •? O c t o b e r T e r m , 1949.

No. 44.«*■ •

t:: ,

P I e m a n M A R io k S v v e a t t , P etition er ,

i v.

.. »

T h e o p h i i .u s S h î c k e e P a i n t e r e t a l .

7 On a. W rit of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

* : of the State of Texas.• * /• ...

i * ir

v 5s------------;

> BRIEF <PF A M IC I (|uRIAE IN SU PPO RT QF

\ PE T IT IO N E R

> r X• ••• • £

V V. \

? >: 1 st a t e m e n t

5

This is a ,brief of amici curiae iii support of petitioner on a

writ’of certiorari to review the judgment, of the Texas Court of

Civil- Appeals-:. ( R. 465) affirming a judgment of the District

Cou?t of Travis County denying petitioner’s request for a writ

of mandamus •'(R. 438-41 ). .* Review was denied by the 4 exas

Supreme Court (R . 466). Certiorari was granted by this Couit

on Nov. 7, r1949. The jurisdictional details are contained in

petitioner’s brief, and the procedural history of the case appeals

at Ra 438-72. i Iy »• v

This brief H filed, with the consent of the parties, on behalf

of tlie Committee of Law Teachers Against Segregation in Legal

f

Education, an organization identified more fully in Appendix A

to this brief.

The essential facts are as follows :

The courts below have denied petitioner’s application for a

writ of mandamus to compel the appropriate officials of the Uni

versity of Texas to admit him to its law school in Austin, Texas.

He is concededly in all respects qualified for admission to that

school except for the disqualification of race, for Texas bars

Negroes from this University (R . 425, 445). The'courts below

have rejected petitioner’s contention that this exclusion and peti

tioner’s consequent relegation to a state colored law school vio

late his rights under the Fourteenth Amendment.

At the time the record below was made, the colored school was

located in Austin, Texas. It has since been moved to Houston

(see R. 51-2 ; Bulletin of the Texas State University for Negroes.

School of Law 5 (1949-50)). Petitioner contends that, for the

decision of the issues on which he petitions, the location is im

material except in one important respect: The use of the Univer

sity of Texas (white) faculty members was contemplated while

the school was in Austin (R . 454), but a separate faculty is to

be recruited for Houston (R . 28-9; see Bulletin, supra, at p. 4).

The Texas law school (colored) was set up in response to the

order of the district court at an earlier stage of this same htiga

tion (R . 424-33), and it does not appear in the record that there

have ever actually been any students in it (though doubtless

there are some), either in Austin or in Houston. Sweatt was the

first Negro to apply for admission to the Texas law-school (white 1

(R . 451), and in any case Texas concedes that the colored sclmo

will have very few students (R . 77).

S U M M A R Y OF A R G U M E N T

The basic position of this brief is that segregated legal ecluca

tion in the state institutions of Texas violates the ^qual pi ol e 1 11<"

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. That position is ap

proached by three different paths.

3v. - ?,

* • ».x* ̂ ̂ ■ •

First, anafyfiis of the origins of “ equal protection” in Arherican

law ihows that, in the form p f “ equality before the law /’ it was

transferred to tjhis country from the French by Charles Sumner as

part bf his attaqk on segregated education in Massachusetts a decade

before the Civil War, and linked by him with the Declaration of

•Independence.-: Popularized i|y Sumner, it or like phrases became

the Sogan oFtfre abolitionists* and it passed into the Constitution

as ai\ important part of the abolitionists’ share o f the Civil W ar. i .« # •

victory. Congress, contemporaneously with the adoption of the

I'oui/teenth Aniendrnent, deafly understood that segregation was

incorjapatible yvith equality, a judgment reflected by this Court in

Railroad C o .'y ., B ro w n , 17 Wall. 445 (1873).

' • ; t '*•

h\'(Plessy yf. B crg u so n , 163$U.S. 537 (1896), this Court aban

doned the original conception-of equal protect ion, adopting instead

the ldgal fiction*that segregation (in that case, in transportation)

is not discriminatory. This tyas a product, in part at least, of a

policy' judgment that the judiciary was incapable of enforcing the

Amendment as.it was written: and that the underlying social evil

* must vbe left to 5th e correction /pf time: The Court erred oil both

counts: the judiciary is not s|> powerless as it supposed, and the

result̂ of its- abdication have* been disastrous. The dissenting

view a) of Mr. Justice Harlan ifo the P lrssy case were correct, and

• should be adopted now. 3

3 i *

Seiiond, we ■■challenge the ^applicability to education of the

"separate but; equal” refinement of the equal protection clause.

\Vhile£we graht-the existence â f troublesome clicta, there is neither

a holding nor even carefully considered dicta by this Court declar

ing that segregation may be enforced.in any phase of education.

In Rl$ssy v. P erg n so n the Court did not say that segregation was

valid in every context in which men could devise ways o f separat-

fing themselves/by color. Orfc the contrary, it made careful dis

tinction between reasonable afid unreasonable segregation/ W e

omtertd that segregation in education, is for this purpose unrea-

Vmablje. • \ ;t

. / v

ilurcl, eveii within the broadest application of P lc ssy v.‘ P c r -

•luson'j petitioner is entitled to absolute equality in education.

4

♦

For reasons set forth in detail in the body of the brief, it is im

possible for petitioner to receive at the improvised colored law '

school a legal education equal to that offered at the well-known

University of 1 exas law school (w hite). Nor,' indeed, can segre

gated legal education ever afford equal facilities.

A R G U M E N T

I.

TH E EQ U AL P R O TEC TIO N CLAUSE W A S IN

T E N D E D T O O U T L A W SEGREGATION.

I }le Court below held (a ) that segregated legal education can

meet the constitutional standard, and (b ) that Texas (colored) '

in fact did so. W e challenge at the outset the entire basis of

any decision which assumes that segregation can meet the stand- '

arc! of the Constitution. The Negro for whom the first section of *

the Fourteenth Amendment was primarily adopted was largely .

read out of that Amendment by nineteenth century decisions.1

The time has come to reconsider the frustration of so much of .

section one of the Amendment as relates to the equal protection •

of the laws.

Society in the past has known intermediate stages of bondage

between the free and the slave. In antiquity, “ between men of

these extremes of status stood social classes which lived outside ’

the boundary of slavery but not yet within the circle of those

who might rightly be called free/’2 The Thirteenth Amendment,

took the Negroes out of the class of slaves. -Section one of the .

1While decisions outside the area of segregation are not directly

involved in this case, the leading segregation decision of Plessy v. .

Ferguson, 1(53 U.S. 537 (189(5), can be understood only as part of

a group of decisions in the latter part of the nineteenth century,

narrowly construing the capacity of the Fourteenth Amendment to

protect Negro rights. Other decisions include the Civil Rights Cases,'"

109 U.S. 542 (1883), and United States v. Harris, 10(5 U S (52!) '

(1883).

2Westermann, Bctzveen Slavery and Freedom , 50 Am Hist Rev

213, 214 (1945). h

4

•f

Fourteenth Amendment was intended to insure that they not be

dropped at some half-way house on the road to freedom. It sought

to bring file ex-slaves within tile circle of the truly free hy obliter

ating l§g*al distinctions based on race.

The ^evidence of intefat to eliminate race distinctions in trans

portation1' and educatioii, relationships which must be considered

together jn the history-;'of equal protection, is particularly clear.

Equal protection first entered American law.in a controversy over

segregated education. r>

1. The original meaning of equal protection is incompatible

with segregated education;

• • * w

It was-, one thing, and a very important one, to declare as a

^political’ abstraction that “ all men are created equal,” and quite

; another-, to attach concrete rights to this state of equality. -.The

^•Declaration of Independence did the former. The latter- was

/Charles; Sumner’s outstanding contribution to American law.

v The great abstractiori|of the Declaration of Independence was

Mhe central rallying point for the anti-slavery movement. W hen

Slavery ;\Vgas the evil to-he attacked, no more was needed. But

iis some; of the New England States became progressively more

'^committed to abolition, the focus of interest shifted from slavery

.̂ Itself to .the status and rights of the free Negro. In the Massa

chusetts1'.; legislature in thfe 1840’s, Henry W ilson, wealthy manu-

Tacturerj abolitionist, anp later ^United States Senator and Vice

president, led the fight A against discrimination, with “ equality”

his rallying cry.3 One/W ilson measure gave the right to recover

-/damages, to any person ^‘unlawfully excluded” from the Massa

chusetts ̂ pbblic schools.4 i\

•v Boston . thereupon established a segregated school for Negro

^children the legality of Which was challenged in R ob erts v. C ity

\pf B oston > 5 Cush. (M ass.) 198 (1 8 4 9 ) . Counsel for Roberts

\------------ _• {

3 For an •'•account of Wflson’s struggles against ant i-miscegenat ii >n

Jaws, against separate transportation for Negroes, and for Negro

^education, see Nason, L ife: o f H en ry W ilson, 48 et seep (187(5).

4Mass. Acts 1845, c. 214*

was Charles Sumner, scholar and lawyer, whose resultant oral

argument was widely distributed among abolitionists as a pamph

let.5 * Sumner contended that separate schools violated the Massa

chusetts state constitutional provision that “ All men are created

free and equal.” 0 He conceded that this phrase, like its counter

part in the Declaration of Independence, did not by itself amount

to a legal formula which could decide concrete cases. Nonethe

less it was a time-honored phrase for a time-honor.ed idea and, in

a broad historical argument, he traced the theory of equality from

Herodotus, Seneca and Milton to Diderot and Rousseau, philos

ophers of eighteenth century France.

A t this point Sumner made his major contribution to the theory

of equality. He noted that the French Revolutionary Constitu

tion of 1791 had passed beyond Diderot and Rotjsseau to a new

phrase: “ Men are born and continue free and equal in their

r ig h ts .” Using a popular French phrase in English for the first

time, Sumner referred to “ egalite devant la loi,” or equality before

the laiv. The conception of equality before the law, or equality

“ in their rights,” was a vast step forward, for this was the firs!

occasion on which equality of rights had been made a legal con

sequence of “ created equal.”

Equality before the law, or equality of rights, Sumner insisted,

was the basic meaning of the Massachusetts constitutional pro

vision. Before it “ all . . . distinctions disappear.” Man,

equal before the law, “ is not poor, weak, humble, or black; nor

is he Caucasian, Jew, Indian, or Ethiopian; nor is he French.

German, English, or Irish; he is a M A N , the equal of all his

fellow men.” 7 Separate schools were unconstitutional because

they made a distinction where there could be no distinction, at

the point of race, and therefore separate schools violated the prin

ciple of equality before the law.

r’Among those active in distributing the pamphlet was Salmon l‘

Chase of Ohio. Diary and Correspondence o f Sainton P. Chn.u .

Chase to Sumner, Dec. 14, 1849, in 2 Ann. Rep. Am. Hist. Ass'n

188 (1902).

ttThe following summary of argument is taken from the complete

argument reprinted in 2 Sumner. If'orks 327 et seq. ( 1874 ).

■Ibid.

6

.V

2

s argu-The Massachusetts court, impersuaded, rejected Sumner

nieq̂ t, and Wal in turn reversed by the state legislature.8 But the

argument outlasted the cas|, and from it the phrase ‘ ‘.equality

before the law,” or its briefer counterpart, “ equal rights,” , became

the tneasuriiigi stick for all proposals’ concerning freedmen.

a. # •> * # r*-

Pjpor to the Civil W ar, the controversy over equality for the

freepmen was'primarily a depute within the States, but national

: emancipation ^brought the isiue to Congress where Sumner kept

“equality’ iti.thc forefront of ( ongressional attention." -Shortly

before the first, meeting of tHe 39th Congress in December, 1865,

the new Black Codes in th-e Southern States had shocked the

North into widespread recognition of the need to secure equality.10

•• Sumner's popularization of ijis equality theory had been so sue-'

cessfcul that it§ echo returned from Radicals everywhere.11 Rep-

■ rese^tative Bingham of Offro offered a proposed Fourteenth

‘ Amendment-in which the keyjphrase was a guarantee to the people

of “6qual protection in their ^rights, life, liberty, and property.” 12

Senator Mop rill of Vermoift, shortly to be a member of the

Join£.Committee on Reconstruction, sent a note to Sumner sug-

gestipg that.-tfie best “ jural’'*phrase*’ for an amendment would

1 be a .'guarantee that citizens £re “ equal in their civil rights, im~

.munfties and,<privileges and Equally entitled to protection in life,

------ *4jt----- ’ ’

, 8Mjass Acts; 1855, c. 250. <

"See, e.g., liis discussion in She Senate of the possible wisdom of

including “equality” in the Thirteenth Amendment. Cong. Globe,

38th Cong., 1st Sess. 1482 (1884).

1 "Inanely compilations of these Codes are McPherson, Handbook o f

Politics fo r 18(58, 29-44 ( 1808)£ 1 Fleming, Docum entary H istory o f

Reconstruction ic. 4 (1900). y»

’ ’ “Equality.before the law” jjivas the general cry. A Pennsylvania

State-Equal Rights League signed its correspondence “ Yours for

justice and equality before theflaw.” Letter to Stevens of Nov. 1,

pS t evens'-Mss. (1805), Lib. Cong. And see resolution of Provi

dence, R. I., . Union League £lub, ibid, asking “our members in

.Congress” to secure “equal rights of all men before the law.” “ Ab

solut ,̂ equality before the law” jivas demanded in Grosvenor, 24 New

duiglander 20^ (1865). See also James, The Framing o f the Four-

Iccntdx Am endm ent 29 et seq. ,'Jl939), an unpublished Ph.D. thesis

in thq-library of. the University^ of Illinois. On the relative amount

'of attention giyejn the first, as ^bmpared to the other sections of the

.-Amendment, sfeefnote 22 infra. .-

• 12Cbng. Glot?e> 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 14 (1805).

«

liberty and property.” 13 Sumner himself introduced a reconstruc

tion plan, an important part of which included “ equal protection

and equal rights.” 14

The first relevant measure actually to he considered by Con

gress was the hill which became the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

This hill was originally introduced by Senator W ilson of Massa

chusetts, the same W ilson who had been so active earlier in the

equality struggles in that state,15 * and we may assume that the

proposal represented the joint policies of W ilson and Sumner.10

The W ilson proposal invalidated all laws “ whereby or wherein

any inequality of civil rights and immunities” existed because.of

“ distinctions or differences of color, race or descent.” 1 his meas

ure, as it passed the Senate, contained a clause forbidding any

“ distinction of color or race” in the enforcement of certain laws,

and assured “ full and equal benefit of all laws” relating to person

and property. Senator Howard, a member of the Joint Com

mittee on Reconstruction, said of the Act, “ In respect to all civil

rights, there is to be hereafter no distinction between the white

race and the black race.” 17

The Civil Rights bill was enacted, but over the protest of one

extreme radical in the House. Representative Bingham of Ohio

opposed the measure on the ground that the Thirteenth Amend

ment gave it an inadequate base. He preferred to wait until

13Morrill to Sumner, undated, prob. Oct. or Nov., 1865, in Sumner

M ss., quoted in James, supra note 11 at 31.

14H) Sumner, W orks 22 (1874). .

ir,Though the measure was introduced by Wilson, actual leadership

on the proposal passed from him to Senator Trumbull of Illinois,

chairman of the Judiciary Committee. The proposal originated with

S.9 in the 39th Cong., introduced by Wilson, from, which the.text

quotations are taken. A few days later, after floor discussion which

revealed that Trumbull was willing to take the lead on the measure.

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 43 (1865), Wilson introduced a

new bill, S. 55, which retained and enlarged the language of S. 9.

This bill was referred to by Trumbull’s name but retained Wilson's

proposals. S. 61 became the Civil Rights Act of 1866. 14 Stat.

(1866).

10Wilson hinted as much. Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 3't

(1865).

11 Id. at 504.

8

9

a .^ w Am^iidlment might |ass which would eliminate all “ dis

crimination lie tween citizens on account of race or color.” 18 A s

a member of*the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, Bingham

wa^ then ^ k . n g on just|such an Amendment. W ith fellow

: Coipmittee members such a§ those extreme equalitarians Stevens

H ° f ard’ aAd jMorrill, there yras no serious obstacle in Committee.’

Bingham:;drafted for the ^Committee the essential language of

sectfon one of.the Fourteenth Amendment..' In the vital equality

■ cause he combined the language of his own earlier proposed

amendment,- equal protection in their rights” and the Civil Rights

b' " benefit.|of all laws” into the concise “equal

protection of the laws.” '" th e prompt adoption of the Amend

ment: earned the aholitionisf theory of racial equality into our

, hast0 document.2" As S en io r Howard, floor leader for the

, moidnient in. the Senate, sa|d of the clause, it “abolishes all class

legislation m.the States and does away with the injustice of sub

jecting one caslte of persons tp a code not applicable to another.” -

i le J ore o i , the clause he deduced to Sumner’s meaning: “ It.

establishes equality before the< law , ” 21

-____JL '1; , 4 * ,

18I3. at 1290, j293. J :

w-Triot f„ref ,S ? co';trib"'i°n J>f the Bingham draft of the clause

nrVrv^i t rWOr.ds he usecU but in‘ those he omitted. Previous

! ' ? ®a S had l^ e tim e s carried words of qualification as to the par- '-

t.ailar types of laws as to whidj equal protection was to be afforded

1 he Cwfi Rights bill in the S^ate had referred to “equal benefits

^ d f c r e d " gS- • -eCurity of I>erson and estate,” andnacl rjtei red iq discriminatiQn in civil rights and immunities”

Bingham saw hbpelcss confusidli in these refinements, see remarks ■

utcd, qupra note •!8, and omittedjthem. He thus brought the language

■ !nto af CPrd w,t.h the broad “equality before the law.” ' * •

do nois ) n tracing th,s history of the phrase “equal nrotec-

lion, qverloolc sporadic earlier jitses of similar language. See e q ;

Me c £ °s tStA r C l H ConSt- Ar«.gV I8 ( ,7 9 8 ).; and• ’ - S r ' •’ ̂ ̂ (1819). *.The context of those Articles deni

mg w.ft freedom of religion, art so aliert to .he subject a hand h

!nenlAfre " ever- r” k'rred tl> «>f>«*ion will, the Fourteenth Ameiuh

l ' V ^ Globe,',39th Cong., tsi Sess. 27CCi f 18G0) Some of the

aS the text "bove,must

L * *

10

Because the primary concern of those who enacted the Four

teenth Amendment was with sections two and three of t e men

meat rather than section one which includes equal protection,

we do not have complete evidence of the views of all the respon

sible men of the time on the meaning of equal protection W c

do know that the clause found its way into the Constitution

through Sumner, through Wilson, through Trumbull and through

the twelve majority members of the Joint Committee on Recon

struction. O f those fifteen at least eight— Sumner, W ilson, Bing

ham, Howard, Stevens, Conkling, Boutwell and M orrill-th ou gh t

the clause precluded any distinctions based on color. lh e

Trumbull, Fessenden, and Grimes— had some mental reservations,

particularly as to miscegenation, although they agreed generally

22Mnrh of the murkiness in the history of “ privileges and lin-

>» ii rcnn ” and “due process,” as well as equal protect > ,

"s produced by the 'fact that what has become the only significant part

nf the Amendment was then the least significant part. iL >

?• . represented a coalescence of certain economic and political

interests along with the abolitionists. Standard references on * *

mtercsts, S f R - r Am crlcan Civilization c. 23

^ d ’ “ Morri^n and C o n n e r , The Growth o f Re-

a n ,u<>\ The pest telling of the manner in which the s<

^ I t i ^ n ^ ^ ' s r ^ t h e i r prohilnis by the ,F ™ rte^th AnienT

„ol the middle sections of the Amendment, while section one was

abolitionists’ share of the victory.

«.vnu. views of Sumner, Wilson, and Howard are apparent from

Pout well are apparent from their consistent support of the Sun n<

civ rights hiil! discussed in detail, infra The case a. to B ingW

• rle-ir since his pre-occupation in the Amendment was argi

wi h !i h " pr’S s ’ an 1 inunu’ ities clan* hi, specia contr iu.,,0

r-f 9 P nut well Ramin sconces o f S ixty Years 41. lluw"

view'was apparently in accord with the others o this> -

evidenced at least hy some phrases. See, c.g., CO g.

Cong., 1st Sess. 121)3 (18GG).

r

IH

V

with;.t:he other*!. Fhe positions of the remainder we do not know,

though somfe,..at least, doubtless agreed with Sumner.25- It was

tliuŝ the dominant opinion *;of the Committee that the clause

eliminated distinctions of cofor in civil rights

• '.r • > ■

.; ; •. V . .

2. Contemporary rejection^ of ’ ’separate but equal” in Con

gress, impiediately before and after the Fourteenth

Amendment, represent^ a judgment incompatible with

segregated, education. 1 ■ '‘ \ 1 . .. • t ■

Congress Repeatedly considered “ separate but equal” in the Re-

construction decade, particularly in connection with transporta

tion. ̂ Railroad".and street carxompanies in the District o f Colum

bia early began to separate '(while and colored passengers, put

ting them in: separate cars oij, in separate parts of the same car,

with quick Congressional response. As early as 1863, Congress ,

amended the charter of the Alexandria and Washington Railroad

to provide tha,t “ No person .Shall be excluded from the cars on.

account of color.” "0 When, irj 1864, the Washington and George

town* street c)ap company attempted to handle its colored passen-

gers Jyy putting them in serrate cars, Sumner denounced the

practice in the . Senate and sjet forth on a crusade to eliminate

street- car segregation in the$District.27 After a series o f skir- '

mishes, he finally carried to passage a Jaw applicable to all District

carriers that .‘up person shall be excluded from any car on account

•of color.” 28 5 • )• / t ••

■' 6 * y

24Ffessenden'a^nd Trumbull believed that the Civil Rights Act and ;

the Atnendmefit did not affect 'jmti-miscegenatiqn legislation. Cong.

Clobe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (ft)5 (180(5) (Fessenden) ; id\ at 322

( 1 rufihbull). In 1864 Grimes tfro light segregated transportation was '

qiuab Cong. Qlobe, 88th Cong., pst Sess. 8133 (1864), with Trumbull

apparently contra on that issuer «/. at 3132. Whether the views of

.brinies changed- is not known. ■%

2BTjiese fouf jnembers, 11 arris, Williams, Blow, and Washburne,

-were conventional radicals andj Harris,-Blow, and Washburne had '

very strong anti-slavery backgrounds. It is therefore highly probable

jliat alt least SQntp of them shared the views of Sumner and Stevens,

but wfe have np direct evidence.;

2012 Stat. 8Of):( 18(53). §

a7Cfcng. Globe;-'38th Cong., IsCSess. 553, 817 (1864)

2813 Stat. 537 X1865). *

i

The discussion of the street car bills, all shortly prior to the

Fourteenth Amendment, canvassed the whole issue of segregation

in transportation. Those who supported the measures did so on

grounds of equality. Senator Wilson denounced the “ Jim Crow

car,” declaring it to be “ in defiance of decency.” 20 Sumner per

suaded his brethren to accept the Massachusetts view, saying that

there “ the rights of every colored person are placed on an equality

with those of white persons. They have the same right with white

persons to ride in every public conveyance in the common

wealth.” * 30 Thus when Congress in 1866 wrote equality into the

Constitution, it did so against a background of repeated judgment

that separate transportation was unequal.31

The history of equal protection and separate schools, though

less clear, suggests a similar interpretation. The close of the War

found public education almost non-existent in the South,32 and

Negro school status in the North ranged from total exclusion from

schools to complete and unsegregated equality.33 Four Southern

Reconstruction constitutions provided for mixed schools, and the

Northern educational aid societies offered unsegregated education

in the South.34 Although these efforts to achieve unsegregated

education were of little practical effect, they indicate the intel

lectual atmosphere from which equal protection emerged. The

abolitionists were absolutely confident that the races both could

12

See rc-

2nCong. Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess. 3132, 3133 (1864).

30/</. at 1158. .

:nThis was clear even from the conservative viewpoint,

marks of Senator Reverdy Johnson, id. at 1156.

},2One of the many works on the subject is Knight,' The Influence

o f Reconstruction on Education in the South (1913).

3:?An extensive account contemporary with Reconstruction, much

broader in scope than the title indicates, is Spec. Rep., Commissionci

o f Education on Condition and Im provem ent o f Public Schools, Dust.

Col., H R. Exec. Doc. No. 315, 41st Cong., 2d Sess. (1870).

•^Materials are collected in 2 Fleming, supra note 10 at 171-212.

Even conservative Southerners, when they sought to give full com

pliance to the Fourteenth Amendment, conceded that equality required

unseeregated education. See Williams, The Louisurna Unification

M ovem ent in 1873, 2 J. South. Hist. 349 (1915), describing the con

cession of mixed schools by a political group headed.by Gen. 1 . 1.

Beauregard.

arid should, -under the principle of equality, mingle in the school

rooms.30 - . |

?The primary responsibility of Congress for education was in

the; District pf Columbia, where a segregated system was a going

operation prior to the endjjof the Civil War. Securing a place

on.; the District of Columbia Committee, Sumner proceeded to

atfĉ ck discriminations in t£e District one at a time.30: Since he

ch&se first:, to eliminate restrictions on Negro office-holding and

jufry service,- he did not r^acli the school question on his own

agenda until 1870.37 He then twice carried proposals through

the Committee to eliminate the segregation,38 and urged his

piqiposal oil the floor of th£ Senate on the grounds of equality:

C^ery child, white or blacfi:, has a right to be placed under pre

cisely the Ratine influences, jwith the same teachers, in the same

school rooffi, without any ̂ discrimination founded on color ” 30

— it-------- •« fr*• *

/ T'he Arrtendment must b© read in the light of this psychology of

optimism. Immediately after’jh e War the abolitionist societies under

took educational work in the fouth on a large scale, fully recorded in

such of their journals as The .American Freeman and the Freem an 'v

Journal The‘Constitution of, the Freeman’s and Union Commission

provided that No schools or Supply depots shall be maintained from

the benefits of-winch any person shall be excluded because of color”

Ih d A m . Freeman 18 (1866)^ Lyman Abbott, General Secretary of

the Commission, published a statement explaining that the policy had

heerj fully considered: “ it isjinherently right. To exclude a child

Irorh a free scliool, because h£ is either white or black, is inherently

wrong . . . i [W e must | lead public sentiment toward its final

goal-, equal justice and equal rights . . . . The adoption of the

leverse principle would really jlend our influence against the progress

of liberty, equality, and fraternity, henceforth to be the motto of the

republic. Id, at 0. 1 he fact is* that few whites attended these schools,

floyd, Some Phases o f Educational H istory in the South since JS65

Studies in Southern History 259 (1914).

30Sumner expounded this seriatim policy in Cong. Globe 10th

tong., 2nd Sess. 39 (1807). 7.

,7The jury and office law was twice pocket-vetoed by President

Johnson, and Sumner, therefore, had to secure its passage three times

nefote it became effective in President Grant’s administration 10 Stat

3 (1809). ..............

,18S. 301, (Joiig. Globe, 41st) Cong., 2nd Sess. 3273 (1870) and

S. 1244, u l at 1053 et seq. :V

™fd. at 10557

14

The most important new voice heard in the District of Colum

bia school debate on Sumner s proposal was that of Senator Matt

Carpenter of Wisconsin, a leading constitutional lawyer of his

time and prevailing counsel in E x parte Garland, A- W all. 333

(1867), E x parte M cC ardle, 7 W all. 506 (1869), and the

S la u g h ter-H ou se C ases, 16 Wall. 36 (1873). Carpenter said:

“ M r. President, we have said by our constitution, *we

have said by our statutes, we have said by our party plat-

foi ms, we have said through the political press, we have

said from every stump in the land, that from this time hence

forth forever, where the American flag floats,[there shall'he

no distinction of race or color or on account of previous

condition of servitude, but that all men, without regard to

these distinctions, shall be equal, undistinguished before the

law. Now, Mr. President, that principle covers this whole

case.” 40

Filibuster, not votes, stalled the District of Columbia school

measure.41 Sumner thereupon terminated his efforts to clear up

discriminations one at a time and determined to make one supreme

effort along the entire civil rights front. He put his whole energy

behind a general Civil Rights bill, which forbade segregation

throughout the Union, in the District of Columbia and outside

it, in conveyances, theaters, inns, and schools.42 The consideration

by the Senate of this measure, which in modified form became

the Civil Rights Act of 1875, represents an overwhelming con-

tempoi ary judgment that separate but equal” schools, wherever

located, violate the equal protection clause.

In the debates on this new civil rights bill, the leading cases

on which this Court relied in R lcssy v. b crgusovi were pressed

upon the Senate and rejected as unsound. R ob erts v. C ity o f

"'Cong. Globe, 41st Cong., 3rd Sess. 1033 (1871).

41 Hy 1872, the filibuster had come into frequent use in the defense

against radical legislation. By a vote of 35 to 20 Sumner defeated

those who sought to keep his District school measure off the floor

entirely, Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong., 2d Sess. 3124 (1872), but his time

was used up before he could bring the matter to final vote.

42 1 he measure was proposed by Sumner both as a bill and as an

amendment to other lulls over a period of years. Its final presenta

tion was in the 43rd Cong., S. 1.

€5 15

Rost on, supra, was quoted without avail 4!l a , . ,

(),f ĉecisioii', State v. M c& am i, 21 Ohio St 198 ( 1 8 7 2 f

f “ “ — is f e 12 a , e qi,ate° t s ! e je(^ :

T ^ S r /L T n ';0 kne* '!,e FoUrtee" th Amendment b e lt -

M a d e A c t i o n s b eT u s f of T J c ag^ 1 ^ at the A mend,nent

u j , . u i . , . v ,,J race. A s Senator Edmunds of

• V 2 ‘ ?r C lalrm;ui ofltbe Senate Judiciary Committee nut

t e° ,e r̂ eC,etl - l « - ‘ efecbo„ls : “ This is a matter A b s ent

■gfit, unless you adopt the Slave doctrine that color and race are

teaspns for; distinction among citizens.” " ' Sumner himself de

.need separate but equag’ in the Senate as he had denounced

* "1 h,S ° ri i n t e n t in R ^ r t s v. C ity o f B oston years W ore

N e n a T a & h ^ T ‘C otfter excusewhich finds Equality in

f %?‘ e,s- sel>arate conveyances, sepmate

• the ? ; T te, ! 1U,,rd,C5' a,lf' ^ r a t e c e m e t e r i^

•• tL coTtrivanr ' fit,a ^ "bstlU,tes for Equality; and this is .the contrivance hy which a transcendent right, involving a

«. transcendent duty, is evaded. ^

Assuming \Vhat is most absurd to assume and

ri at '*. eontradicted b)j all experience, that a substitute can

,be an equivalent, it is .so in form only and not in real v

',s tJZ t Xith’ theem •>‘ t,SJ n )" Kli8 " i,y to : the colored race, im

•'acter Jt L w 1 • <$ slavery, and this decides its char-

acter. U is S lavery m f t s last appearance.” 40

T je bill started its final rqad to passage in the 43rd Congress

As Sumner had died, Senator Frelinglniysen o f New Jersey led

tie debate fertile bill, beginning on April 29. 1874, with an ex

tensive argument that segregation was incompatible with the

. fourteenth Amendment. Ttie bill, he said, sought “ freedom from

all disci mmiatlon before the Jaw on account of race, as one of the

^'Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong., gd Soss. .320 1 (1872).

th$ on the McCann case. Id. at! '* th$ time of its hnahconsideration Seminr Tr,-.>i: i

,,, cljarge of; tile bill in the Senate, explained why he 111 "uglCthc

S es?o 's74T .'STl° l " 0t CO" trf • 2 C° " « - Rcc-.34r>a. 43rd Cong., 1st

^’<£ong. Glpl*\ 42nd Cong., Id Sess. 82(10 ( 1872).

Cong, dope, 42nd Cone \2d Sess •■iqo aua / iq^ i \ / ,added). "t,-, ĉ.ss> J84 (.18*1) (emphasis

i

16

fundamental rights of United States citizenship.” 47 For this he

found full warrant in the equal protection clause. Segregation

in the schools, he said, could only be voluntary, for the object of

the bill is to destroy, not to recognize, the distinctions of race.” ‘s

There were in the Senate three distinct views on the problem

of segregated schools. A minority thought that ‘ ‘separate but

equal” schools should be permitted. On May 22, 1874, an amend

ment to that effect offered by Senator Sargent o f California was

rejected, 26 to 21. Those 26 included Morrill, Colliding and

Boutwell, who had been on the Committee which had drafted the

Amendment. By voting to reject the “ separate but.equal” school

clause, they necessarily indicated a judgment that Congress had

power to legislate against segregated schools under the equal pro

tection clause. This contemporary affirmative and deliberate

interpretation of the Constitution is entitled to great weight here.

M cP h erson v. Slacker, 146 U.S. 1, 27 (1892).

The 26 were not themselves of one mind. Senator Boutwell

represented a small minority view that separate schools neces

sarily bred intolerance and therefore should not be allowed to exist

even if both races desired it.40 However, the dominant Senate

opinion was that separate schools should be forbidden by law, ns

the Amendment and this bill forbade them; but that if the entire

population were content in particular instances to accept separate

schools, it might do so. Senator Pratt of Indiana, one of the

most vigorous supporters of the bill, noted that Congress was con

tinuing separate schools in the District of Columbia because both

races were content with them; and at the same time he pointed

out that where there were very few colored students, they would

have to be intermingled/’0 Senator Howe put it most concretely

when he observed that if, by law, schools were permitted to be * 4

472 Cong. Rec. 3452, 43rd Cong., 1st Sess. (1874). •

4i'“ lf it were possible, as in the large cities it is possible, to estabh-h

separate schools for black children and for white children it is mi l "

highest degree inexpedient to either establish or tolerate siu '

schools.” From speech of Senator Boutwell, id. at 44 lf>.

■•"Id. at 4081, 4082.

4

17

V r t

serrate, thej would never in fact be equal. He believed in pro-

■' ! " t T f SeP7 a ‘ ? Sl!h00lS a" l ,he" People do as they chose:

the individuals and n<rt the superintendent of schools judge

ot the comparative merits <̂ f the schools.” 51 '

' ., I he bin^ f SSed the .Se«4«> but in the House the result was

different. Th.e bill passed, l*ut with the school clause deleted.

this deletion was the product of many factors. The House

had.J>reviouSly voted to require mixed schools,5* but on this occa-

Sion, it was, confronted with- the firm opposition of the George

eabody Fund. Peabody, American merchant who founded

wha{ became. J; P. Morgan &*Co„ established a fund of $3,000,000

to aid education in the Sofith. As abolitionist education aid

: societies ran put o f money# and collapsed, the Peabody p'und

became the only major outside agency aiding Southern education.

Ihe-fund °0P|?sec' mixed sclibols, withdrawing its aid where they

were required.J3 It claimed fredit for inducing President Grant

to '"Struct lriSi House floor leader to abandon the school provi

sion, ̂ Coupled with this pressure were tlireats from Southern

representatives’ that they would end their newly founded-public

schoql systems i f the Senate measure passed.05 In addition, some

■ teprgsentativ.es felt that the courts would protect the Negroes on

tlie sphool issue, and thus as a matter of legislative discretion

waived the right to legislative aid.00 ] 'or whatever combination------1 v ■*’ . *T “ r t '

R,M. at 415i. h -- i

104? Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong., 2d Sess. 2074 (1872)

( ouge refused, <4 to 99. to la^bill on table) ; id. at 2270 2271 (en-

* , vS ei a,K! reat?-ll,rcc ,i,,u's’ J<*> «> 78) ; no final action taken

•2 Fleming, supra note 10 at 194. During this period the Fund

was tinder the direction of Dr. ifarnas Sears, later succeeded by I 1

C? rr#. ,l? a volume on: the work of the Fund, introduces

" U t(>eic. of llllx^ schools with the words. “ Some persons, not to ‘the

liannef born , took the lead in organizing a crusade for the co-ecluea-

( IK08°/. ' rry’ B f f SkctCh ° f GcorSc Peabody .10

•'Vf/. at 64, l

\ i S,4 . ^ctission of this IX)int by Representative Roberts, who

slated *hat he preferred to prohibit segregated schools but would vote

o omit the clause for fear thp South would abolish all schools

.1 Con£ Rec. 981; 43rd Cong., 2cJ Sess. (3875).

' Se6 remarks of Representative Monroe, id. at 997 998

r \ » • ’

of reasons, a leading Negro Representative from South Carolina

consented to eliminate the school clause in return for assurance

that the rest of the bill would pass.57 The House result, clearly,

thus represented a political rather than a constitutional judgment:

In summary, ecpial protection as a legal conception originated

before the Civil War in Sumner’s attack on segregated schools.'

It became the abolitionist rallying cry and was brought into the

Constitution by the abolitionist wing of the Republican Party.

Before the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, “ equal rights’’

was thoroughly understood to mean identical, and not separate

rights, particularly in transportation. That was the view of the

dominant group among those who actually phrased the Fourteenth

Amendment. Throughout the debate on the Amendment its sup.-

porters acknowledged no doctrine of equal but separate as an

exception to the fundamental concept of equal rights. Contem

porary legislative action confirms this basic position.

3. In Railroad Co. v. Brown, this Court early decided that

“ separate” could not be “ equal” .

In the leading case o f R ailroad Co. v. B row n , 17 Wall. 445

(1873), this Court early decided that separate accommodations,

no matter how identical they might otherwise be, were not equal.

On February 8, 1868, Catherine Brown, colored, attempted to

board a railroad car on a line from Alexandria to ;.Washington.

That road had a “ Sumner amendment” in its charter which pro

vided that “ no person shall be excluded from the cars on account

of color.” ™ The railroad maintained two identical cars, one next

to the other on the train, using one for white and the other for

colored passengers. When Mrs. Brown attempted to sit in the

“ white” car, she was ejected with great violence.

The pertinent legal issue in Mrs. Brown’s case'was whether

segregation amounted to the same thing as “ exclusion from the

cars.” The episode attracted immediate attention. because Mrs.

18

r,7See remarks id. at 1)81, 1)82.

r,s 12 Slat. 805 (18(33).

t ■ •

( .

j t

-f

*« 19

Brdwn was }n charge of gie ladies’ rest room at the. Senate.

A Senate investigating committee concluded that the Company

:• latt vlolab-d dts charter, aijd recommended that the charter be

; reP.?aled ifVMrs. Brown \fere not fully compensated by civil

damages.B0 V i

i -

At the ttfel, the Compariy unsuccessfully asked for a charge

to tpe jury ihat separate but* equal cars complied with the statute,

• and; in the Supreme Court argued that “ making and enforcing

the separation of races in itij cars” was “ reasonable and legal.” 00

, Tjjhe Supreme Court unanimously rejected the “ separate but

equal” argument as “ an ingenious attempt to evade a compliance

with the obViQus meaning o| the requirement.” 01 The object of

the jSumner^aftiendment, said! the Court, was not merely tp let the

Negroes buy transportation,; but to let them do so without “ dis

crimination” :v

> Congress, in the belie£j.that this discrimination was unjust,

.acted, y It told the cojfnpany, in substance, that it could

.road into tlfe District as desired, but that this

^discrimination must cesfcse, and the colored and 'white race,

the *se o f the cars, be placed on an equality. This con

dition it 'had the right;-to impose, and in the temper of

CCongrejjs'.at the time, it As manifest the grant could not have

vbeen m£de without it.” 0?

: y r‘ ••

Thus in its first review of |‘separafe but equal,” this Court held

that 'segregation was “ discrimination” and not “ equality.” We

ask the Court to apply that 6ame principle in the instant case.

------ _------ j z ' ■

50Sen. RepC Jtfo. .131, 40th C$ng., 2d,Sess. (18G8).

fl°The quotatipn is taken frorft the brief on file in the Supreme Court

•t t «■ p

0117 Wall. 445, 452. The sapie approach as that of the Brown case

is taken whenever a statute which requires “equal” treatment is held

[°. X ° - ~ segr€gati°n. See, ela., Baylies v. Curry, 128 111. 287 21

N.E..595 (1889 ) (restricting Negroes to particular theater seats held

violapon of statute) ; Jones v. Kehrlein, 47 Cal. App. G4G 194 P 55

(1920) (same).' '• ’

°“W Wall. 445 at 152, 153 (%niphasis added).

f

4. Plessy v. Ferguson, which undid the Brown case and the

legislative history of equal protection, should be over

ruled.

Twenty years after R ailroad C o. v. B row n , this Court took

a wholly different view of segregation.

The exact issue in P lessy v. F erguson , 163 U.S. 537 (1896),-

was whether a Louisiana requirement of separate railroad ac

commodations denied equal protection. Mr. Justice Brown for

the majority held that this segregation did not stamp “ the colored

race with a badge of inferiority.” If it did so, said he, “ it is'

not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because

the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it.” <i:j

Mr. Justice Harlan, dissenting, states our case:

“ It was said in argument that the statute of Louisiana

does not discriminate against either race, but prescribes a

rule applicable alike to white and colored citizens. But this

argument does not meet the difficulty. Everyone knows that

the statute in question had its origin in the purpose, not

so much to exclude white persons from railroad cars occu

pied by blacks, as to exclude colored people from coaches

occupied by or assigned to white persons . . . .

“ The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in

this country. And so it is, in prestige, in achievements, in

education, in wealth and in power. So, I doubt not, it will

continue to be for all time, if it remains true to its great

heritage and holds fast to the principles of constitutional

liberty. But in view of the Constitution, in the eye of the

law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling

class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution

is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among

citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal

before the law. The humblest is the peer of the riiost power

ful. The law regards man as man, and takes no account

of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as

guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved. It'

is, therefore, to be regretted that this high tribunal, the final

expositor o f the fundamental law of the land, has reached

20

03Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 551 (1896).

*4

r.■$

, f ' T ? " ’ the D r o d f c o t t case.” (1 6 3 -U S. at 556-9)

•,. C° re ? f?M r- Justice Brown’s argument is i„ his assunin

• ,v " t a‘ Ŝ g a t i o n is not aSwhite judgment of colored inferior-"

ty ,Th,s would be so palpably preposterous aŝ a statement o f

t e o f ^ e V St aSSUme Jt l 'Ce Brown " ’ ‘ ended it as. a legal

t z s & r f f s t t f . - r * r - « • *

W esj, castes ^ I,lilia ,fj, ” » £ 5 " * ^

. a & s j ? * 11* *...... t * ” 'r « . » - . l a s :

• The real question, thereto*, is why should the Court'have

f t S n l y t o ^ ll fiCti0n? S' ,DWcI the C m ' n have thought

than discrimination? ** Cte'1S<|t,,at segregation is anything other

s i s . ^ ; r nth “ ient- ,,ot

c s s s z z ?

*" ' 1 erve for l" e N- ° 3 ^

nf:d^PourreerTil^Am^dnieilh<:fw e rgtr^nt ” leanjn*’

termination of 'segregation is & t &. • ? ^ ' y m,pl,es- that

rontenrf: that th e * ^s n I •£ W,th traditio"- But we

_ ____ £. ? nothing ,h the tradition of Negro slavery

Me 3 War^em'rfe fi!^ rra !cyCuWrtS ?f /V •l'ec,°’I.struc*,'° n decisions,

(1926) « He lists Brree factors-d i/ " .U m M ,? '«* «* H istory fins

T ,estion': from national politics'- fhe deshe V’ el" / " nate “ ‘ he Negro

"> state authority,- 'and the desh-i ... , ’ r,-eleK:lfe the Negroes

Shuth. O ^ ’ central ^ on£ S i ? " " " " the Court

been sacrifice* for an£ or all fcf Z J L ’S S S ' 8h° UW * *

V v :j { 21

22

that is worth preserving. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fif

teenth Amendments committed the country to the -great experi

ment of making a complete break with that tradition. When

Charles Sumner gave the abolitionists the formula of equality

before the law, he did not mean equality with reservations, equal

ity with segregation. Decisions such as P lessy v. F ergu son turn

the Fourteenth Amendment into a phantom or a grotesque mis

take. A s Senator Frelinghuysen said in presenting the anti-segre

gation Civil Rights Bill of 1875 to the Senate:

“ If, sir, we have not the Constitutional right thus to legis

late, then the people of this country have perpetrated a

blunder amounting to a grim burlesque over which the world

might laugh were it not that it is a blunder over which

humanity would have occasion to mourn. Sir, we have the

right, in the language of the Constitution, to give ‘to all

persons within the jurisdiction of the United States the equal

protection of the laws’ .,M1,>

This Court should return to the original purpose of the equal

protection clause, to forbid distinctions because of race. State

enforced segregation is unconstitutional because it makes such a

distinction. A s Senator Edmunds put it, it is “ slave doctrine

to make color and race reasons for distinctions among citizens.

Segregation is discrimination. Railroad Co. v. Brozvn, supra.

II.

TH E BASIC POLICIES U N D E R L Y IN G TH E C O U R T ’S

A P P R O V A L OF SEGREG ATIO N IN PLESSY V . FER

G U SO N H A V E , IN TH E YEARS IN T E R V E N IN G SINCE

T H A T DECISIO N, PROVED T O BE N O T O N L Y

W H O L L Y ERRONEOUS B U T SERIOUSLY" D ESTRU C

TIV E OF TH E D EM O C R ATIC PROCESS IN THE

U N IT E D STATES.

If the meaning of equal protection, whether considered in terms

of historic intent or of the ordinary meaning of words, is clearly

incompatible with segregation, as we say it is, then the further

task confronts us of assessing the underlying bases of P lessy v.

(,r>2 Cong. Rec. 3451, 43rd Cong., 1st Sess. (1874).

23

Fergus o n ., .Concededly ‘a^page of history is worth a volume of

logic.” N ew Y ork Trust. C o. v. E isner, 256 U .S . 345 , 349

( f^ 21) . This Court must deal with the same practical consider

ation that ;faced the Court-tin the nineteenth century. Petitioner,

if fie woul<ji persuade you t$ reconsider E lessy, must persuade you

Ha r lap's dissent had more than a theoretical validity.

jTwo fundamental judgments of fact and policy underlay the

decision of the majority m P lcssy v. F ergu son . One was the

Court’s acceptance of the premise that, since “ [legislation is pow

erless to eradicate racial iititincts or to abolish distinctions based

upon physical d ifferen ces,it is impossible to eliminate segrega

tion founded in the “ usage£, customs and traditions” of the com

munity, arfd hence the Constitution must bow to the inevitable.

Tlp ̂ other^vwps the Court s«assumption that the wiser policy was

to det events /take their course and that governmental intervention

“cffn only result in accentuating the, difficulties of the present situ

ation.” ld3; U .S . at 550-2£• ‘ r* .*

.Over half '.a century has passed since the Court decided P lessy

v. ip erg us of 1, In these ye^rs much that was obscure about the

practice o£ segregation has become clarified. A s events have

unfolded, as', trends have ^become more distinct, as additional

knowledge has been gained,/the impact of segregation upon Am er

ica^ life has ̂ -emerged more clearly. Tn the light of these inter

vening developments, the b£sic judgments made by the Court in

P lessy v. F ergu son have proved to be erroneous. Indeed, far

frofn solving* Or even alleviating the problem of racial segregation

th^-decision of the Court hî s tended to intensify it and to create

conditions that threaten to itndermine the very structure of Am er

ican democratic society. I

V *■ - V

T .^The ju>dgnient of the-Court in Plessy v. Ferguson that

direct governmental intervention to eliminate segrega

tion is ineffective to overcome the prevailing customs of

the com/nunity has proved to be without foundation.

There are severe limitations, of course, upon the effectiveness

of (direct legal.compulsion td wipe out the gap that exists between•• •" ' >* .■

*

24

5

American theory and certain American practices in race relations.

But the fact is that the ideal of racial equality is a deeprooted

moral and political conviction of the American people. Decisions

of this Court upholding that conviction, therefore, cannot fail to

have a profound and far reaching effect upon the constant strug- ^

gle being waged between ideal and practice. And, conversely, j

a decision that fails to give support to that conviction must neces-

sarily have important depressing and retarding consequences. J

Ji

Experience has shown that this Court is not as impotent in the >

field of race relations as the majority in P lessy v. F ergu son

assumed. On the contrary every decision of this Court against v

racial discrimination has made a significant contribution toward' i

the achievement of racial equality.

Concrete evidence is available, for instance, that the decisions |*

of this Court in the white primary cases have not only eliminated 5

the institution of white primaries but have resulted in a substan- .

tial increase in Negro voting. V. O. Key, in his careful study

entitled S outhern P olitics, reports that except in four states of

the Deep South the decision in Sm ith v. A lhvriglit, 321 U.S. 649

(1 9 4 4 )t was accepted “ more or less as a matter of course.” 00 J*

Pointing out that the effect o f the decision was not felt until the- |

1946 primaries, he notes that “ Florida experienced a sharp in-' j.

crease in Negro registration after 1944” ; that “ [i]n 1946 the j'

voting status of Georgia Negroes changed radically,” the number-

of Negro registrants rising to an estimated 110,000; and that in

Texas, “ with a few scattered local exceptions, Negroes voted f.

without hindrance in the 1946 Democratic primaries.” 67 Key j,

reports that four states— South Carolina, Alabama, .Mississippi

and Georgia— made strenuous efforts to avoid the-effect of the

A lh vriglit case, but that these efforts were quickly nullified by the

courts in both South Carolina and Alabama. With respect to. 5

South Carolina he observes :

“ Negroes have encountered stubborn opposition to even t.

a gradual admission to Democratic primaries in South Caro-

« «K ev . Southern Politics (>25 (1049 ).

" ' Id ' at t>25. 519-521.

4

4

t

>i*.

v<• 25

f-r

i

* Ima. The last vestige: of the white primary was 'stricken

f, t,own oy? court action fn that state in 1948. Prior to that

; time virtually no Negroes voted in the primaries. About

> 35,000}-are reported to;have cast ballots in the 1948 prim-

.* ai>- 4

^hus it is iClear that judicial decisions have been a powerful

• influence in^assisting the N^gro to obtain the right of franchise.

I h^.decision of this Court i|i M organ v. V irgin ia , 328 TJ.S. 373

(19^6), has; made an important contribution to racial equality in

the.^ield ofyt^ansportation.°4' And evidence was offered in the

\ i,,st^nt case-showing that where segregation in the University

of $farylan(| Taw School wps ended by judicial compulsion the

subsequent experience was \yholly satisfactory.70

TJiat the majority in P lessy v. F ergu son greatly over-estimated

the practical difficulties of eliminating segregation through gov

ernmental action is likewise; apparent from the accumulation of

evidence in recent years that’discriminatory practices, long rooted

m tbe "usages, customs and traditions" of the community, can

be successfully eradicated. The President’s Committee on Civil

• Pigftts, in opt; of the most significant findings of its well-docu

mented repottc concludes: :

: »’• • f:

? reason and history were not enough to substantiate

pie argument against segregation, recent experiences further

strengthen it. For tlies^ experiences demonstrate that segre

gation i$ an obstacle to Establishing harmonious relationships

.simong groups. They pijove that where the artificial barriers

t hat divide people and groups from one another are broken,

tension and conflict begip to lie replaced by cooperative effort

and an environment in which civil rights"can thrive.’ ’71

___ 1 * /•

.<>8// • a* 522: : For a Till account of Negro voting and the white

primary litigation, see id. at 51 £ 2?. 019-43.' See also Murray (PM )

N ie h c g r o Handbook 48-53 (1949). It has been estimated that the

S n n i l ’° i o ^ ° eS registered| ° vote 1n the -South increased from' *J1.1,0©0 in 1940 Jo over 1.000.000 in 1948. Id. at 53.

<!!>Sye, e.g., uj. ‘at 94. v

This evidence waj excluded by the trial court.

W 'Rt e rt, o f- ? res,’dent’s Committee on Civil Rights To Secure

ThrsHRig/its 82+3 (1947). .1 ° £ r£

26

Specifically in the field of education I. E. Taylor,' after noting

the increase of Negro teachers in white colleges, observes:

“ Reports are coming in that Negro scholars are giving

a good account of themselves, that their students are enthu

siastic and open-minded, and that alumni and parents are

taking the situation calmly.’ ’72 73

The elimination of segregation in public housing raises issues

perhaps more difficult than those involved in its elimination from

higher education. Yet Charles Abrams, one of the country’s fore

most authorities on housing, writes :

“ Where Negroes are integrated with whites into self-

contained communities without segregation, reach daily con

tact with their co-tenants, are given the same privileges and

share the same responsibilities, initial latent tensions tend

to subside, differences become reconciled, cooperation en

sues and an environment is created in which interracial

harmony will be effected.

“ This conclusion is supported by many reports of housing

authorities who have ventured into mixed occupancy.” ™

Experience with the abandonment of segregation in the armed

services, again closely comparable with the situation in higher

education, has been similar. The report of the President’s Com

mittee on Civil Rights cites an illustration involving Negro and