Letter from Lani Guinier to Sharon Holland RE Bozeman v. Lambert Fees

Administrative

October 2, 1984

1 page

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Letter from Lani Guinier to Sharon Holland RE Bozeman v. Lambert Fees, 1984. 3cb62ae3-e692-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/83fffdc5-923c-410f-bf3c-fc59406b0e5a/letter-from-lani-guinier-to-sharon-holland-re-bozeman-v-lambert-fees. Accessed February 14, 2026.

Copied!

Lesa,UDrenseE,

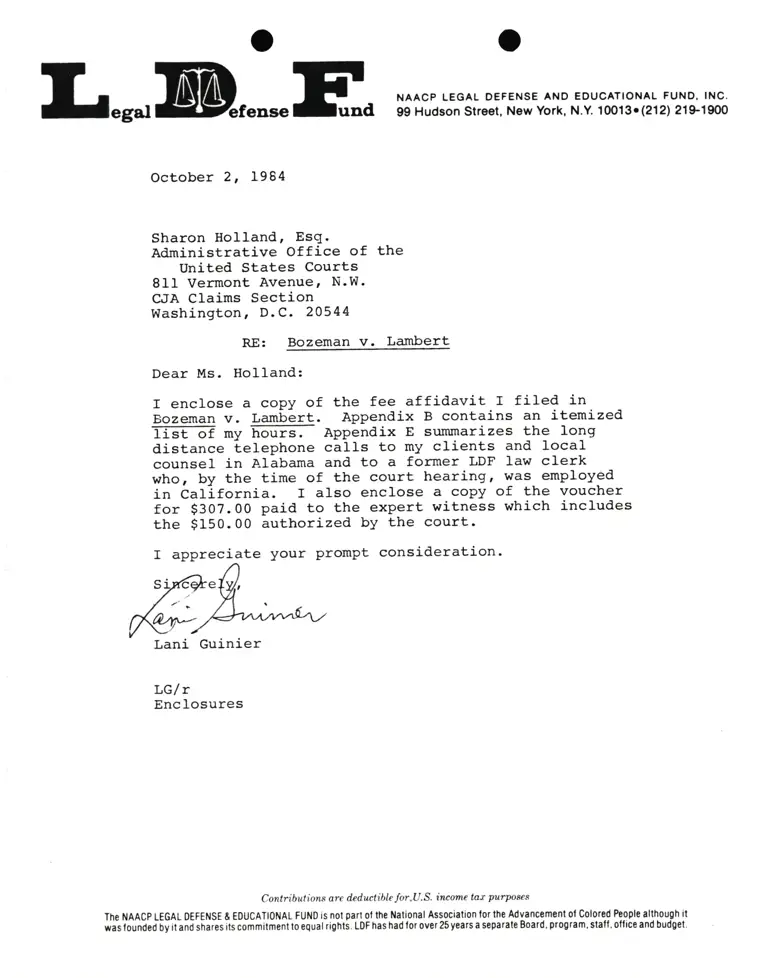

October 2, 1984

Sharon Holland, Esq.

Administrative Office of the

United States Courts

811 Verrnont Avenue, N.W.

CJA Claims Section

Washington, D.C. 20544

RE: Bozeman v. Lambert

Dear I'ls. Holland:

I enclose a copy of the fee affidavit I filed in

Bozeman v. Lambert. Appendix B contains an itemized

ffiT rny troffi Appendix E summarizes the long

distance Lelephone calls to my clients and local

counsel in Alabama and to a former LDF 1aw clerk

who, by the time of the court hearing, was employdd

in california. I also enclose a copy of the voucher

for $3o7.OO paid to the expert witness which includes

the $150.00 authorized by the court.

I appreciate your prompt consideration.

Lani Guinier

LG/ r

Enclosures

Contibutions are dcdwtible lm,U.S. intatne tan purpoaes

The NAACp LEGAL OEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND is not part ol the National Association tor the Advancement ol colore.d Psople although il

wai rounOeO U11 il ind shares its commitment to equal rights. LOF has had lor over 25 years a separate Board, program, stall, ollice and budget.

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EOUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

99 Hudson Street, New york, N.y. 10013o(212) 21S1900

f\\r

FI YR' \

sT s\NF!

)qJi\

I

tr\..J

\

\

\L:

SLA

P>

}N

sL+

,N