NAACP v. Alabama Petitioner's Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. Alabama Petitioner's Reply Brief, 1957. 82251028-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8400b2ec-6c73-4cfb-994f-76e8329c4c17/naacp-v-alabama-petitioners-reply-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

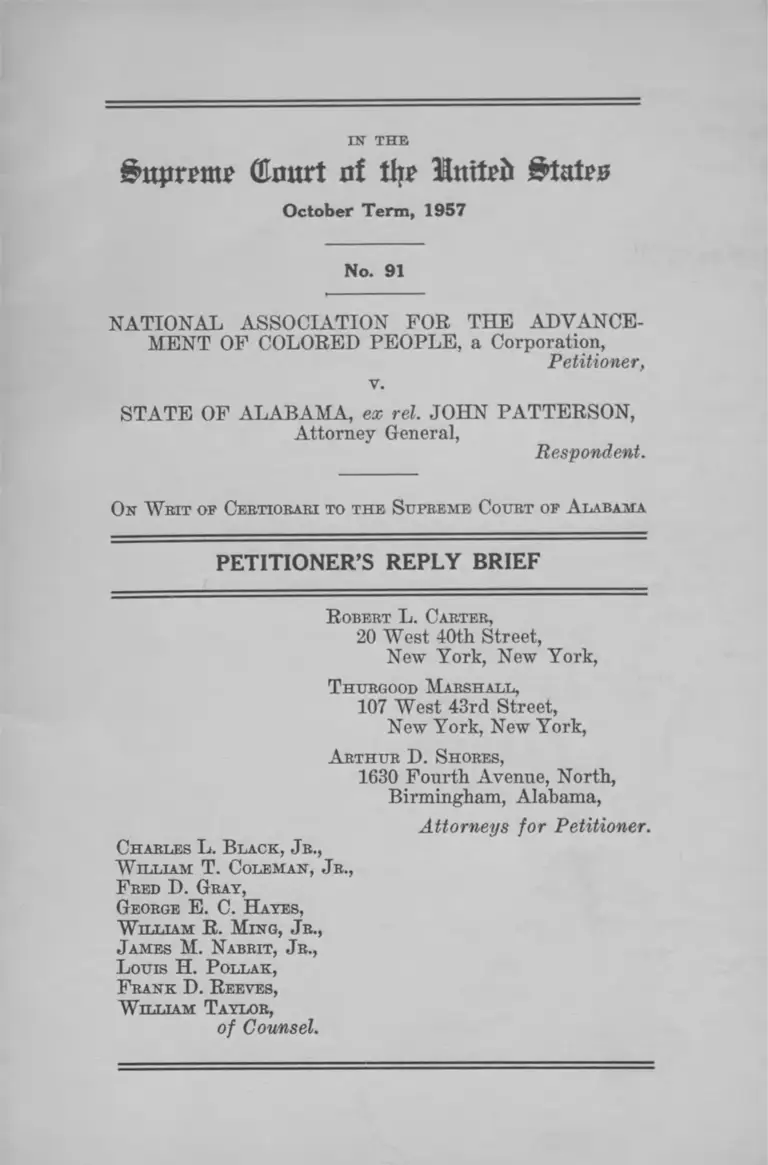

IN THE

£>ujirpmp (Unmet ni tlj? £latp0

October Term, 1957

No. 91

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOB THE ADVANCE

MENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, a Corporation,

Petitioner,

v.

STATE OF ALABAMA, ez rel. JOHN PATTERSON,

Attorney General,

Respondent.

On W rit op Certiorari to the Supreme Court op A labama

PETITIONER’S REPLY BRIEF

R obert L . Carter,

20 West 40th Street,

New York, New York,

T hurgood M arshall,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York,

A rthur D. S hores,

1630 Fourth Avenue, North,

Birmingham, Alabama,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

Charles L . B lack, Jr.,

W illiam T. Coleman, Jr.,

F red D . Gray,

George E. C. H ayes,

W illiam R. M ing, Jr.,

James M. N abrit, Jr.,

L ouis H . P ollak,

F rank D. R eeves,

W illiam T aylor,

of Counsel.

PAGE

Petitioner’s, and its Members’, Right to Free Asso

ciation ........................................................................... 1

The Constitutional Right of Anonym ity.................... 3

The Place of Anonymity in a Democratic Society.. 3

Anonymity as an Aid to Free Expression.................. 6

Secret Elections in Democracies................................... 8

The Absence of Justification for Compulsory Dis

closure .......................................................................... 8

Table of Cases

Adler v. Board of Education, 342 U. S. 485................ 3

American Communications Associations v. Douds,

339 U. S. 382 .............................................................. 3

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 ............................. 3

De Jonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 ............................... 2

Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U. S. 233.......... 11

Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization,

307 U. S. 496 .............................................................. 2

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath,

341 U. S. 1 2 3 .............................................................. 3

Kedroff v. St. Nicholas Cathedral, 344 U. S. 94 . . . . 3

New York ex rel. Bryant v. Zimmerman, 278

U. S. 63 ...................................................................... 9,10

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 5 1 0 ................ 2,10

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 5 1 6 ................................. 2

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 8 8 ......................... 11

Roth v. United States, 352 U. S. 964, 1 L. ed. 2d.

(Adv. pp. 1498, 1506-1507) ..................................... 11

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U. S. 75___ 3

Watkins v. United States, 354 U. S. 1 7 8 .................. 3, 8

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357 .......................... 2

INDEX

11

Statutes

PAGE

Title 7, Code of Alabama (1940), Section 370 .......... 4

Other Authorities

Blankenship, How to Conduct Consumer and Opinion

Research (1946) ........................................................ 6,7

Bleyer, Main Currents in the History of American

Journalism (1927) ..................................................... 4

Cantril, Gauging Public Opinion (1944) .................... 7

Cushman, Civil Liberties in the United States (1956) 2

Defoe, Shortest Way with the Dissenters.................. 4

The Federalist, Henry Holt Edition (1898) ............ 4, 5

The Federalist, Modern Library Edition (1937)___ 5

Foreign Affairs, Yol. 25, Nos. 1 & 4, Vol. 27, No. 2,

Vol. 36, No. 1 ............................................................ 5

Maclver, ed., Conflict of Loyalties (1952) ................ 5

Minto, Daniel Defoe (1909) ....................................... 4

National Opinion Research Center, Interviewing for

NORC (1945) ............................................................. 6

Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four ................................... 7

Schlesinger, Paths to the Present (1949) ................ 5

“ State Control of Political Organizations’ First

Amendment Checks on the Powers of Legislation, ’ ’

66 Yale L. J. 545 (1957) ........................................... 3

Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234 .................. 2, 8, 9

Taylor, How to Conduct A Successful Employees’

Suggestion System ................................................... 7

IN THE

S u p r e m e CUmtrt rtf tljp S t a i r s

October Term, 1957

No. 91

-----------------------0----------------------

N ational A ssociation fob the A dvancement of

Colored P eople, a Corporation,

Petitioner,

v.

S tate of A labama, ex rel. John Patterson,

Attorney General,

Respondent.

O n "Writ of Certiorari to the S upreme Court of A labama

-------------------------- o-----------------------

PETITIONER’S REPLY BRIEF

Petitioner’s, and its Members’ , Right to Free

Association

Respondent concedes that corporations enjoy freedom

of speech and press. While it does not clearly deny that

in some circumstances there may be a constitutional right,

founded in free speech and association, to withhold the

kind of information the state has tried to exact here, it

argues principally that corporations have no constitutional

right to free association and, at any rate, may not assert

constitutional defenses on behalf of their members—these

must be set up by the individual himself.

However, if respondent concedes a corporate right to

free speech and press it agrees that rights exist which

any reasonable appraisal inextricably connects with

free association. This has been made clear in the opinions

of this Court. “ The right of peaceable assembly is a right

cognate to those of free speech and free press and is

2

equally fundamental.” DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353,

364. The three rights, indeed, are “ inseparable.” Thomas

v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516, 530. As a distinguished scholar

has observed, thus the right of assembly is “ an independent

right similar in status to that of speech and press. ’ ’ Cush

man, Civil Liberties in the United States (1956), p. 60.

Like the other basic First Amendment freedoms, free

dom of assembly is protected by the Fourteenth Amend

ment against unreasonable impairment by the states.

DeJonge case, supra; Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357;

Thomas v. Collins, supra; Hague v. Committee for Indus

trial Organization, 307 U. S. 496.

This constitutional status of freedom of association

was most recently reaffirmed by this Court in Sweezy v.

New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234, 250:

“ . . . Our form of government is built on the prem

ise that every citizen shall have the right to engage

in political expression and association. This right was

enshrined in the First Amendment of the Bill of

Rights. Exercise of these basic freedoms in America

has traditionally been through the media of political

associations. Any interference 'with the freedom

of a party is simultaneously an interference with

the freedom of its adherents.”

It is, of course, not entirely realistic to speak of a

corporation’s freedom of association. These artificial

entities express themselves and associate through officers,

agents, and (in the case of membership corporations)

members. As a practical matter, to say that only peti

tioner’s members may assert their individual rights to

anonymity is to concede a self-nullifying right for then

the only ones who could claim the right to non-exposure

would be those who already are exposed. But, beyond this

obvious realistic consideration, the cases have, when

appropriate, permitted one person or entity to assert the

rights of another. We have, in our original brief cited

and discussed Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510;

3

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath, 341

U. S. 123; Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249. We may

add, as other decisions which expressly or implicitly recog

nize the propriety of such assertion: Kedroff v. St.

Nicholas Cathedral, 344 U. S. 94; Adler v. Board of Educa

tion, 342 U. S. 485; American Communications Association

v. Douds, 339 U. S. 382; United Public Workers v. Mitchell,

330 U. S. 75; see also Comment: “ State Control of Political

Organizations: First Amendment Checks on Powers of

Regulation” 66 Yale L. ,T. 545, 546-550 (1957).

The Constitutional Right of Anonymity

Aside irom the harassing aspect of the requirement of

exposure, petitioner submits that it impairs a constitutional

right of anonymity that may not be infringed in the absence

of an overriding communal interest which the state is con

stitutionally competent to protect. The right of anonymity

is an incident of a civilized society and a necessary adjunct

to freedom of association and to full and free expression

in a democratic state.

In Watkins v. U. S., supra, this Court said (354 U. S.

at 187):

‘ ‘ There is no general authority to expose the private

affairs of individuals without justification in terms

of the functions of Congress.”

What is true of individuals, petitioner submits, is true of

associations; and what is true of Congress is true of all

other agencies of government, Federal and state. Govern

ment may not, without justification, pierce the veil of

anonymity.

The Place of Anonymity in a Democratic Society

It is important to recognize that there is nothing in

herently wrong in desiring to keep one’s name from the

public. Alabama itself by statute, recognizes the value of

4

anonymity in some circumstances: Title 7, Code of Ala

bama (1940), Section 370 expressly confers upon a news

paperman the immunity from being compelled to disclose

in any legal proceeding or before a legislative committee

the source of any information procured or obtained by him

and published in his newspaper.

Anonymity has a long and honorable history and may

serve important social objectives. The cause of civilized

progress was greatly benefited by the fact that Daniel

Defoe could publish anonymously his Shortest Way with

the Dissenters, and it was correspondingly greatly harmed

when Defoe’s identity was discovered and he was fined and

pilloried for his offense (Minto, Daniel Defoe (1909), pp.

38-40).

In this country, even before the founding of our repub

lic, the practice of speaking anonymously on social and

political matters was accepted as normal and proper.

Benjamin Franklin signed his first pieces for the New

England Courant as “ Silence Dogwood” (Bleyer, Main

Currents in the History of American Journalism (1927),

pp. 56-57). The use of names like “ Philanthrop,” “ Hu-

manus” and “ Cato” as signatures on articles on public

affairs was widespread (Id., pp. 43-100). In 1775, Thomas

Paine used the signature “ Humanus” in an article for

the Pennsylvania Journal; after Rev. William Smith,

president of the University of Philadelphia, used the name

“ Cato” in attacking Paine’s Common Sense, Paine replied

under the name of “ Forester” (Id., p. 91). The New

Hampshire and Vermont Journal or Farmers Weekly

Museum regularly published articles in the 1790’s written

by such persons as “ The Lay Preacher,” “ Peter Pencil,”

“ Simon Spunkey,” “ Peter Pendulum” and “ The Pedlar”

(Id; p. 128).

The most famous of all American political writings,

The Federalist, written by Alexander Hamilton, James

Madison and John Jay, was published anonymously. In

0

deed, the attribution of several of the essays is still in

doubt. As Professor Earle points out (Tlic Federalist,

Modem Library edition (1937), Introduction, p. ix), dur

ing the controversy over the endorsement of the Consti

tution, ‘ The press o f the day was submerged with con

tributions from anonymous citizens.” Among those

anonymously opposing ratification was New York’s Gov

ernor George Clinton, who wrote under the name “ Cato.”

(See the introduction by Paul Leicester Ford to the Henry

Holt edition of The Federalist (1898), pp. xx-xxi.)

Thus, in the early days of our Republic, persons who

were or were to become President of the LTnited States,

Chief Justice of the United States, Secretary of the

Treasury and Governor of New York did not hesitate to

maintain their anonymity in publishing weighty public

and political documents.

This practice is still used by public officials. Foreign

Affairs, the United States’ most influential periodical

dealing with international policy, has frequently in recent

> eai s masked the names of its contributors, carrying

leading articles signed simply by single initials, including

the famous “ X ” article, “ The Sources of Soviet Conduct,”

which set forth the Government’s policy towards the Soviet

Union (Foreign Affairs, Yol. 25, Nos. 1 & 4, Vol 27 No 2

Vol. 36, No. 1).

The millions of Americans who are members of secret

fraternal orders certainly believe firmly in their right to

operate anonymously (Schlesinger “ Paths to the Present”

[1949], p. 44). ̂ Professor Schlesinger describes them as

playing a “ positive and continuing role in society” (Id

p. 48).1 v v

1 A vigorous warning against the growing tendency to limit pri

vacy and force all our activities into the glare of government super

vision and public inspection is made by Professor Lasswell “ The

Threat to Pnvacy,” in Maclver, ed„ Conflict o f Loyalties (1952)

pp. 121-140. \

6

Anonymity as an Aid to Free Expression

In a number of ways modern society recognizes anonym

ity as a valuable aid in assuring free expression of

opinion. It is standard practice for newspapers to print

letters signed with initials or fictitious names. While the

editors require that the writer disclose his name to them,

they recognize that a freer expression of opinion can be

achieved if they do not require public exposure of the

writer’s identity.

Public opinion researchers similarly accept the fact

that some persons will hesitate to express themselves

freely and honestly if they think that there is a chance

that their names will ultimately be associated with the

answers they give. In Interviewing for NORC (1945),

the National Opinion Research Center, which has con

ducted surveys for many government agencies, advised

its employees (p. 15):

“ A few persons may be reluctant to talk if they feel

their names will be taken. You can explain that

NORC never wants the name of anyone who doesn’t

want us to have it.”

That the loss of anonymity can have a serious effect

on free expression o f opinion is recognized in the book,

How to Conduct Consumer and Opinion Research, Blank

enship, ed. (1946). The essay on “ Measurement of Em

ployees’ Attitude and Morale,” advises employers to place

(pp. 223-4)

“ . . . emphasis on the point that the questionnaires

must not be signed, that no one in the company will

have access to the answered questionnaires, that

there is no means of identifying a particular person’s

blank. All of the mechanics of distributing the ques

tionnaire forms and the placing of the answered

forms in the ballot box are such as to guarantee

anonymity to the employee.”

7

In the same book, the essay on “ Trends in Public Opin

ion Research’ ’ describes conclusions drawn by the Office

of Public Opinion Research from a comparison of ques

tionnaires answered secretly with others answered by

persons who were told that their identity would be known

xpeiiments with secret ballots as compared with

oral interviews have shown that respondents are not

always frank m stating their opinions. An unpopular

opinion or one that reflects in any way upon the

prestige of the respondent often gets a higher rating

in the secret ballot than in oral replies.” 2

In employees’ suggestion programs, likewise, it is com

mon practice to set up a system in which the person makin«-

the suggestion does not identify himself but receives a

numbered receipt from which he may be identified after

the suggestion has been considered. In How To Conduct A

Successful Employees’ Suggestion System (p. 9), Ezra S.

Taylor rates anonymity as the most important condition for

successful suggestion systems.

, YndGj .lymg 911 these. practice8> anonymous polls, letters

to the editor and the like, is the well-founded belief that

anonymity in the expression of views contributes to the

tree play of ideas and hence to the ultimate search for

truth the same search for truth that the founding fathers

sought to foster by the guarantees of the First Amendment.

Conversely, it. is apparent that a society in which citizens

are not allowed to engage in political activity free of the

watchful eye of the state would be intolerable. As George

Orwell has shown in Nineteen Eighty-Four, such prying

is consistent only with totalitarianism.

- The o^ginal experiments are reported in detail in Cantril

Gauging Public Opinion (1944), Chap. V.

8

Secret Elections in Democracies

Anonymity, 9ecrecy, privacy, however it may be called,

thus has a special value in a democratic society. Nowhere

is this seen better than in the act that symbolizes the unity

of democratic government and its citizens, the election of

public officers. It is not too much to say that the degree

of freedom that prevails in a country’s election is the

surest test of the liberty of its citizens. As Mr. Justice

Frankfurter pointed out, concurring in Siveezy v. New

Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234, 266 (1957):

“ In the political realm, as in the academic, thought

and action are presumptively immune from inquisi

tion by political authority. It cannot require argu

ment. that inquiry would be barred to ascertain

whether a citizen had voted for one or the other of

the two major parties either in a state or national

election. Until recently, no difference would have

been entertained in regard to inquiries about a

voter’s affiliations with one of the various so-called

third parties that have had their day, or longer, in

our political history. This is so, even though ade

quate protection of secrecy by way of the Australian

ballot did not come into use till i888.”

This right of “ political privacy” (354 U. S. at 267) de

serves protection whether exercised through major parties,

through minor parties as in Siveezy, or through organiza

tions with political objectives such as petitioner.

The Absence of Justification for Compulsory Disclosure

Petitioner concedes, of course, that where a paramount

societal interest is to be served or where injury to the com

munity is to be avoided, the right of anonymity must yield

and disclosure of identity may constitutionally be com

pelled. But, as this Court held in Watkins v. U. S. supra,

some justification must be shown. There is, the Court said,

no “ general power to expose where the predominant result

‘J

can only be an invasion of the private rights of individuals”

(354 U. S. at 200). In the words of Mr. Justice Frank

furter, concurring in Sweezy v. New Hampshire, supra,

354 U. S. at 266-7, the Court must strike a balance between

“ the right of a citizen to political privacy, as protected by

the Fourteenth Amendment, and the right of the State to

self-protection.”

Bespondents rely heavily on New York ex rel. Bryant

v. Zimmerman, 278 U. S. 63, for the proposition that the

State of Alabama may properly demand that petitioner

disclose the names and addresses of its members. The

holding in the Zimmerman case, however, is much nar

rower, and does not encompass the questions of constitu

tional law presented in the instant case.

In the first place, the Zimmerman case dealt with a

New York statute as applied to the Buffalo branch of the

Ku Klux Klan. This Court recognized the Ku Klux Klan

as a “ secret, oath-bound association” (at 71-72) and ex

plicitly noted that the class of organizations in the New

York statute has “ a manifest tendency . . . to make the

secrecy surrounding its purposes and membership a cloak

for acts and conduct inimical to personal rights and public

welfare. (at (5). The opinion also relates “ common

knowledge” and a Congressional report concerning the

Ku Klux Klan’s unconstitutional purposes and illegal

activities.

Petitioner is clearly not the kind of organization with

which this Court concerned itself in the Zimmerman case.

The constitutional nature of petitioner’s aims and activities,

set forth and documented at pp. 2-8 of Petitioner’s Brief j

is well-known throughout the United States and seems a

proper subject for judicial notice.

The New York statute was upheld on the following

ground:

10

“ . . . requiring this information to be supplied for

the public files will operate as an effective or sub

stantial deterrent from the violations of public and

private right to which the association might be

tempted if such a disclosure were not required.”

(at p. 72)

Compliance with the Alabama order to produce, how

ever, will operate rather as an effective and substantial

deterrent on the exercise of constitutional rights of free

speech and association by petitioner and its members.

Moreover, the Zimmerman case involved no such

“ special circumstances” or “ climate of opinion” as exist

in Alabama at the present time. (See Petition, pp. 19-25

and Petitioner’s Brief, pp. 12-18). Thus, the action of the

state of New York in requiring the Buffalo Ku Klux Klan

to reveal its members is completely distinguishable from

the court order at issue here. The infringements upon con

stitutional rights of free speech and association raised in

the case at bar are directly connected to the reprisals

against members indicated by the atmosphere in Alabama—

economic pressure, including loss of employment, harass

ment, intimidation, and threats of violence as well as

actual force.

As the state of Alabama has not demonstrated any

valid reason for requiring production of petitioner’s mem

bership list, petitioner has a right to “ protection against

arbitrary, unreasonable, and unlawful interference with

. . . [its] patrons . . . ” Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268

U. S. 510, 535-536.

Finally, the Zimmermann case has no application in the

instant case because the NAACP, unlike the Ku Klux Klan,

is a political organization which plays an integral role in

the free trade of ideas wdiich is essential to our democratic

form of government. As a consequence, the NAACP neces

sarily has a “ right of anonymity” on behalf of its members

as discussed in the preceding sections of this brief.

11

“ The protection given speech and press was fash

ioned to assure unfettered interchange of ideas for

the bringing about of political and social changes de

sired by the people . . . All ideas having even the

slightest social importance—unorthodox ideas, con

troversial ideas, even ideas hateful to the prevailing

climate of opinion—have the full protection of the

guarantees, unless they encroach upon the limited

area of more important interests.”

Roth v. United States, 352 U. S. 964,1 L. ed. 2d (Adv. pp.

1498, 1506-1507); see also Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S.

88, 101-102 and Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U. S.

233, 249-250.

No constitutional justification exists in this case. The

order requiring that petitioner expose its membership lists,

therefore, should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

R obert L. Carter,

20 West 40th Street,

New York, New York,

T hurgood M arshall,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York,

A rthur D. S hores,

1630 Fourth Avenue, North,

Birmingham, Alabama,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

Charles L. B lack, Jr.,

W illiam T. Coleman, Jr.,

F red D. Gray,

George E. C. H ayes,

W illiam R. M ing, Jr.,

James M. N abrit, Jr.,

L ouis H. P ollak,

F rank D. R eeves,

W illiam T aylor,

of Counsel.

Supreme Printing Co., I nc., 54 Lafayette Street, N. Y. 13, BEekman 3-2320

( 1660)