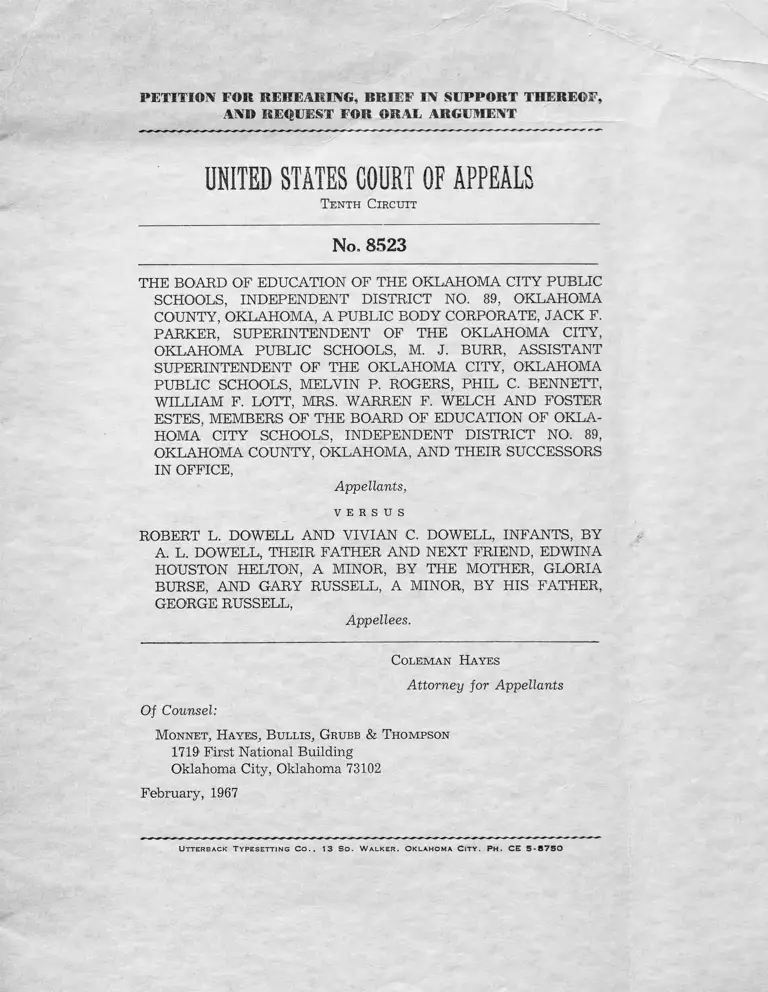

Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Petition for Rehearing, Brief in Support Thereof, and Request for Oral Argument

Public Court Documents

February 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Petition for Rehearing, Brief in Support Thereof, and Request for Oral Argument, 1967. 1a564827-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/840562b5-1ca7-45d2-9b43-2a549b85d571/oklahoma-city-public-schools-board-of-education-v-dowell-petition-for-rehearing-brief-in-support-thereof-and-request-for-oral-argument. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

PETITION FOR REHEARING, RRIEF IN SUPPORT THEREOF,

ANR REQUEST FOR ORAL ARGUMENT

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

Tenth Circuit

No, 8523

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE OKLAHOMA CITY PUBLIC

SCHOOLS, INDEPENDENT DISTRICT NO. 89, OKLAHOMA

COUNTY, OKLAHOMA, A PUBLIC BODY CORPORATE, JACK F.

PARKER, SUPERINTENDENT OF THE OKLAHOMA CITY,

OKLAHOMA PUBLIC SCHOOLS, M. J. BURR, ASSISTANT

SUPERINTENDENT OF THE OKLAHOMA CITY, OKLAHOMA

PUBLIC SCHOOLS, MELVIN P. ROGERS, PHIL C. BENNETT,

WILLIAM F. LOTT, MRS. WARREN F. WELCH AND FOSTER

ESTES, MEMBERS OF THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF OKLA

HOMA CITY SCHOOLS, INDEPENDENT DISTRICT NO. 89,

OKLAHOMA COUNTY, OKLAHOMA, AND THEIR SUCCESSORS

IN OFFICE,

Appellants,

V E R S U S

ROBERT L. DOWELL AND VIVIAN C. DOWELL, INFANTS, BY

A. L. DOWELL, THEIR FATHER AND NEXT FRIEND, EDWINA

HOUSTON HELTON, A MINOR, BY THE MOTHER, GLORIA

BURSE, AND GARY RUSSELL, A MINOR, BY HIS FATHER,

GEORGE RUSSELL,

Appellees.

Coleman Hayes

Attorney for Appellants

Of Counsel:

M onnet, Hayes, Bullis, Grubb & Thompson

1719 First National Building

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73102

February, 1967

U t t e r b a c k t y p e s e t t in g C o . , 1 3 S o . W a l k e r . O k l a h o m a C i t y . P h . C E 5 - 8 7 5 0

I N D E X

PAGE

Petition for Rehearing-------------------------------------------------------------- 1

Bell v. School City of Gary, Indiana, 324 F.2d 209 __________ 2

Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas City, 336 F.2d 988 .. 2

Certificate of Counsel__________________________________________ 3

Brief in Support of Petition for Rehearing_______________________ 3

Statement _____________________________________________________ 3

The Faith of the Board—Good or B ad________________________ 3

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U.S. 294 _ 3

Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas City, 336 F.2d 988 .... 4

The Consolidation of Attendance Districts____________________ 6

Bell v. School City of Gary, Indiana, 324 F.2d 209 __________ 6

Civil Rights Legislation______________________________________ 8

Kelley v. Board of Education of City of Nashville, etc., 270

F.2d 209 _______________________________________ 8

42 U.S.C.A., Sec. 2000c-9__________________________________ 9

42 U.S.C.A. Sec. 2000c (b) _______________________________ 8

Other Portions of the Opinion_______________________________ 9

Conclusion ____________________________________________________ 9

United States Court of Appeals

Tenth Circuit

No. 8523

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE OKLAHOMA CITY PUBLIC

SCHOOLS, INDEPENDENT DISTRICT NO. 89, OKLAHOMA

COUNTY, OKLAHOMA, A PUBLIC BODY CORPORATE, JACK F.

PARKER, SUPERINTENDENT OF THE OKLAHOMA CITY,

OKLAHOMA PUBLIC SCHOOLS, M. J. BURR, ASSISTANT

SUPERINTENDENT OF THE OKLAHOMA CITY, OKLAHOMA

PUBLIC SCHOOLS, MELVIN P. ROGERS, PHIL C. BENNETT,

WILLIAM F. LOTT, MRS. WARREN F. WELCH AND FOSTER

ESTES, MEMBERS OF THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF OKLA

HOMA CITY SCHOOLS, INDEPENDENT DISTRICT NO. 89,

OKLAHOMA COUNTY, OKLAHOMA, AND THEIR SUCCESSORS

IN OFFICE,

Appellants,

V E R S U S

ROBERT L. DOWELL AND VIVIAN C. DOWELL, INFANTS, BY

A. L. DOWELL, THEIR FATHER AND NEXT FRIEND, EDWINA

HOUSTON HELTON, A MINOR, BY THE MOTHER, GLORIA

BURSE, AND GARY RUSSELL, A MINOR, BY HIS FATHER,

GEORGE RUSSELL,

Appellees.

P E T I T I O N F D R R E H E A R I N G , B R I E F I N SUPPORT THEREOF,

A N D R E Q U E S T F O R O R A L ARGUMENT * 1

Come now the appellants, and pray that the Court grant them a

rehearing in this cause, and upon reconsideration withdraw the

majority and concurring opinions filed herein on January 23, 1967 and

reverse the order and judgment appealed from for the following

reasons:

1. The affirmance of the decree of the trial court is based on the

erroneous assumption and premise that the Court found that the Board

2 BOARD OF EDUCATION, ETC. V. DOWELL, ET AL.

of Education had not acted in good faith in integrating the Oklahoma

City public schools as required by the Brown cases.

2. That portion of the opinions dealing with the consolidation of

four specific school attendance districts and designating the grades

which each of the four existing schools should serve

(a) is supported by no judicial authority;

(b) is contrary to the decision of the Seventh Circuit in Gary1

and this Court’s decision in Downs;1 2

(c) has the effect of divesting the School Board of Oklahoma City,

and others, of the duties and responsibilities imposed upon

them and permitting the courts to substitute their judgment

regarding administrative procedures for that of the Boards,

provided only that the Boards could have done the same

thing in the exercise of their lawful discretion.

(d) opens wide the door to any and all courts to “take over” and

“run”' the public schools if any degree of racial imbalance

exists, whatever the cause, contrary to the clearly expressed

admonition of the Congress and the views of all courts which

have considered the question.

WHEREFORE, appellants respectfully pray:

1. That they be permitted to present oral argument in support

of this petition, and if the Court deems this an appropriate case

therefor, to the Court en banc;

2. That a rehearing be granted; and

3. That the order and judgment of the trial court be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Coleman Hayes

1719 First National Building

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

Attorney for Appellants

1 Bell v. School City of Gary, Indiana, 324 F.2d 209-

2 Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas City, 336 F.2d 988.

PETITION FOR REHEARING, BRIEF AND MOTION FOR ORAL ARGUMENT 3

CERTIFICATE OF COUNSEL

I, Coleman Hayes, counsel for appellants, certify that the above

and foregoing petition is not filed for vexation or delay, and that I

sincerely believe the same to be meritorious.

It is believed that affirmance here resulted from fatally defective

reasoning springing from an assumption and premise which not only

find no support in the record but are clearly in conflict with specific

findings of the trial court. If this be true, the decision as a whole is

wrong.

If we be mistaken in this belief, it does not follow that the order

(judgment) of the trial court should be approved and upheld in its

entirety. Consequently, argument will be directed to specific portions of

the judgment and opinions under what we hope are appropriate

headings.

It is true, as stated in the majority opinion, that “ the question of

the existence of racial discrimination necessarily goes hand in hand

with the question of the good faith of the Board in efforts3 to desegre

gate the system.” This is in keeping with the statement in Brown4 that:

“Full implementation of these constitutional principles may re

quire solution of varied local school problems. The school authori

ties have the primary responsibility for elucidating, assessing and

solving these problems; courts will have to consider whether the

3 Emphasis throughout is supplied

4 349 U.S. 294. ,

Coleman Hayes

BRIEF

STATEMENT

The Faith of the Board— Good or Bad

4 BOARD OF EDUCATION, ETC. V. DOWELL, ET AL.

action of school authorities constitutes good faith implementation

of the governing constitutional principles.”

A recitation contained in an opinion dated July 11, 1963, filed

August 6, 1965 ('R. 50) that, “The court finds and concludes from the

evidence that the School Board has not acted in good faith in its efforts

to integrate the Oklahoma City Public Schools as defined and required

in the Brown cases, as to pupils and personnel,” is quoted in the ma

jority opinion and heavily relied upon to support affirmance here. This

finding is also said to distinguish this case from Downs.5

In the 1963 opinion, certain directives were given to the School

Board. Although additional hearings were held in August, 1963, and

February, 1964, the trial court did not at any time make a finding that

the Board had not acted in good faith subsequent to the 1963 opinion.

He did suggest at the conclusion of the 1964 hearing that there was

doubt in the hearts of the negro pupils as to the good faith operation of

the plan submitted by the Board (R. 200).

Thereafter, the court appointed a panel of experts who conducted

a survey and filed a report. In August of 1965 a full hearing was held,

at which those experts and witnesses for all parties testified. It was

following that hearing that the order and opinion here for review were

promulgated.

The evidence offered at that hearing traced the actions of the

Board subsequent to the 1963 order. It is interesting and illuminating

that at the conclusion of this hearing the court not only did not make a

finding of bad faith during the interim, but at the conclusion of the

hearing announced: “Next, I’d like to say that my feeling about this

case is not one that challenges the good faith of the School Board or in

any way indicts the School Board” (R. 358).

Not infrequently trial courts make observations from the bench

which for one reason or another are not incorporated in the formal

judgment or opinion. Not so here. On the contrary, the opinion includes

the following finding:

s 336 F.2d 988.

PETITION FOR REHEARING, BRIEF AND .MOTION FOR ORAL ARGUMENT 5

“The School Board has instituted the changes in its policy and

administration required by this court’s order of July, 1963, and has

in good faith attempted to administer the school system in ac

cordance with these changes” (R. 149).

It is obvious, of course, that the 1963 order was never presented to

this Court for review, and that the one which is now here is that of

September 7, 1965 (R. 147). It seems unfair and illogical for this Court

to base its affirmance upon a finding of fact made in 1963 in view of the

contrary finding made in 1965, and to use the 1963 finding to distinguish

its opinion in Downs from that here for review.

Actually, the findings in both cases are substantially identical,

for as is pointed out in the majority opinion, the trial court in Downs

“ * * * then held that the School Board had acted in good faith in its

efforts to comply with Brown, supra, and the subsequent cases in

volving school segregation.” In the concurring opinion the writer says:

“I start with the premise of the trial court’s finding that the Board of

Education,. despite statements of completely acceptable policy, had not

acted in good faith in effectuating such policies after having been

afforded an opportunity to do so.”

The record establishes exactly the opposite, and the reliance

placed on the 1963 finding is misplaced. What the trial court said in its

1965 opinion is in effect, when paraphrased for simplicity, that “In 1983

I felt that the Board had not acted in good faith in its efforts to integrate

the Oklahoma City schools, and I told the Board what to do about it.

The Board made the changes which I directed, and on the basis of the

evidence now before me, I find that the Board has made those changes

and has in good faith attempted to administer the school system in ac

cordance therewith.”

This is a far cry from what the trial court said in its 1963 order. If

the opinion appealed from had been silent with respect to the good or

bad faith of the Board, it might be argued that at the conclusion of the

1965 hearing the trial court viewed the actions of the Board in no dif

ferent light than it had in 1963. Such, however, is simply not the case.

It is believed that it is basic in the application of principles of logic that

if a premise is wrong, reasoning based thereon will lead to a result

which is likewise wrong. If this be true, it would seem to follow that

concurrence in the majority opinion resulted from the mistaken belief

that there was in truth and in fact in the order and opinion here for

review a finding of bad faith by the trial court.

The Consolidation of Attendance Districts

That portion of the trial court’s order directing the consolidation

of four attendance districts into two and a radical conversion of the four

schools now serving such districts is unique, revolutionary and danger

ous. It is unique because notwithstanding the vast number of so-called

segregation cases which have been before the trial and appellate courts,

none of them has even approached, as to either nature or extent, the

action of the trial court in this case.

It is revolutionary and dangerous because for the first time a

Federal Court has invaded a field heretofore reserved to public officials,

and in effect has authorized and approved the substitution of the judg

ments of trial courts for those of Boards of Education in the administra

tion of public school affairs. If this were not otherwise clear, it is made

so by the statement in the concurring opinion that the courts may do

that which a Board of Education could so long as such action does not

violate constitutional rights.

If this is as sweeping as we think, it would permit a Federal Court

to interfere with and control curricula, location of school buildings,

creation of attendance districts, and any other area in which a School

Board could act without violating anybody’s constitutional rights. The

pronouncement, whether we have exaggerated it or not, finds no sup

port in any decided case. The absence of any citation undoubtedly re

sults from the fact that this Court was unable, as were the plaintiffs in

Gary,6 “ * * * to point to any court decision which has laid down the

principle which justified their claim that there is an affirmative duty

on the Gary school system to recast or realign school districts or areas

for the purpose of mixing or blending negroes and whites in a particular

school.”

6 BOARD OF EDUCATION, ETC. V. DOWELL, ET AL.

s 324 F.2d 209.

PETITION FOR REHEARING, BRIEF AND .MOTION FOR ORAL ARGUMENT 7

It is alarming and surprising that this Court should approve such

novel and radical action by the trial court in such a summary manner7

as is done. The reason given in the majority opinion for such approval is:

“It is obvious that this part of the plan would result in a broader

attendance base and in a better racial distribution of the pupils.”

Thus far, at least, the Supreme Court has not announced its ap

proval of any plan which is designed to remove racial imbalance or to

bring about a broader attendance base or a better racial distribution of

students. Other courts have condemned a program designed to that end.

In Gary the Court held that “ * * * There is no affirmative United States

Constitutional duty to change innocently arrived at school attendance

districts by the mere fact that shifts in population either increase or

decrease the percentage of either negro or white pupils.”

This Court in Downs, in response to a contention that de facto segre

gation existed in Kansas City and should be eliminated, said:

“While there seems to be authority to support that contention,

the better rule is that although the Fourteenth Amendment pro

hibits segregation, it does not command integration of the races in

the public school, and negro children have no constitutional right

to have white children attend school with them.”

The concurring Judge withheld approval of the use of “forced

integration” when viewed as an end in itself, but felt that resort thereto

is justified where it is “ * * * the path to elimination of discrimination.”

We have no quarrel wth this philosophy, but it simply has no place

under the record here.

Discrimination in Fourteenth Amendment cases can only mean the

denial of equal treatment. No instance is cited by appellees where a

colored child has, at least since 1963, been accorded different treatment

because of his race. It therefore seems entirely appropriate and proper

to inquire what and whose constitutional rights have been violated,

7 The subject is exhausted in one page in the typewritten majority opinion,, all of

which is devoted to a discussion o f the plan itself and the percentage o f racial mixture

which would result except for the quoted reason for approval.

a BOARD OF EDUCATION, ETC. V. DOWELL, ET AL.

particularly since the majority opinion seems to recognize that, as the

Sixth Circuit said in K elley: 8

“It is not the business of the Federal Courts to operate the public

schools, and they should intervene only when it is necessary for

the enforcement of rights protected by the Federal Constitution.”

The opinion provides a test for determining the propriety of trial

court’s action. The test is said to be whether “ * * * such compelled ac

tion can be said to be necessary for the elimination of the unconstitu

tional evils pointed out in the court’s decree.” The test should be applied,

not to the court’s decree, but to the record in which it must find support.

The statement of the dissenting Judge that, “Here the court does not

find any explicit discriminatory act,” and with respect to the actions of

the Board following the decision in Brown, “There is no evidence that

since the adoption of that system any child of any race has been dis

criminated against,” cannot be challenged. On the contrary, it appears

that the order appealed from, as the opinion points out, would only

“ * * * result in a broaded attendance base and in a better racial distri

bution of the pupils.” Such motivation or end result has not heretofore

justified any court in doing what the trial court did here.

Civil Rights Legislation

Although not controlling, and if constitutional rights are violated,

clearly ineffective, Civil Rights Legislation, admittedly remedial, should

be of some interest. Congress left no doubt as to the evils which it sought

to remedy in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but was careful to spell out

the limits of the Act. It defined desegregation as follows:

“ ‘Desegregation’ means the assignment of students to public

schools and within such schools without regard to their race, color,

religion, or national origin, but ‘desegregation’ shall not mean the

assignment of students to public schools in order to overcome racial

imbalance.” 42 U.S.C.A. Sec. 2000c (b).

Although admittedly a legislative definition, no court to our knowl

edge has come up with a better one unless it be that of the trial court in

8 Kelley v. Board of Education of City of Nashville, etc., 270 F.2d 209-

PETITION FOR REHEARING, BRIEF AND MOTION FOR ORAL ARGUMENT 9

Gary that “ * * * A simple definition of a segregated school, within the

context in which we are dealing, is a school which a given student

would be otherwise elegibile to attend, except for his race or color, or,

a school which a student is compelled to attend because of his race or

color.”

Furthermore, Congress, in order to make its intention perfectly

clear in this field, said:

“Nothing in this subchapter shall prohibit classification and as

signment for reasons other than race, color, religion, or national

origin.” 42 U.S.C.A., Sec. 2000c-9.

If the congressional definition meets constitutional requirements,

then there can be no question under this record but that the Board has

desegregated the school system in Oklahoma City.

Other Portions of the Opinion

The “majority to minority” transfer policy and the faculty integra

tion portion of the order are subject to the same infirmities as are those

hereinabove discussed for the same reasons. However, it is felt that if

the Board has failed to convince the court that its decision is wrong for

the reasons stated, further argument would not only be unavailing but

burdensome. It has no desire to place itself in that position, and conse

quently refrains from further discussion of these features,

CONCLUSION

This is an important case, not only to Oklahoma City but to all

other School Boards whose duty it is to administer the school systems of

this country within the framework of constitutional decisions in the

field of civil rights. As pointed out in the argument, the opinion and

order of the trial court constitute a big step beyond any which the

courts have heretofore taken in the field of education. If approved, they

could and likely will bring about a rash of litigation in which persons

believing themselves aggrieved will, in reliance on them, seek relief at

the hands of the courts which should rest in those of the Boards, thus

creating a situation bordering on chaos.

10 BOARD OF EDUCATION, ETC. V. DOWELL, ET AL.

For the reasons heretofore discussed, the Board prays that its

petition for rehearing be granted and the cause reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Coleman Hayes

Attorney for Appellants

Of Counsel:

M onnet, Hayes, B u m s, Grubb & Thompson

17191 First National Building

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73-102

February, 1967

\

\

\