Wallace v. Commonwealth of Virginia Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

April 26, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wallace v. Commonwealth of Virginia Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1966. aab91d60-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/841f5bcf-09a2-4ac0-9895-e2a3be2d4c94/wallace-v-commonwealth-of-virginia-brief-in-opposition-to-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

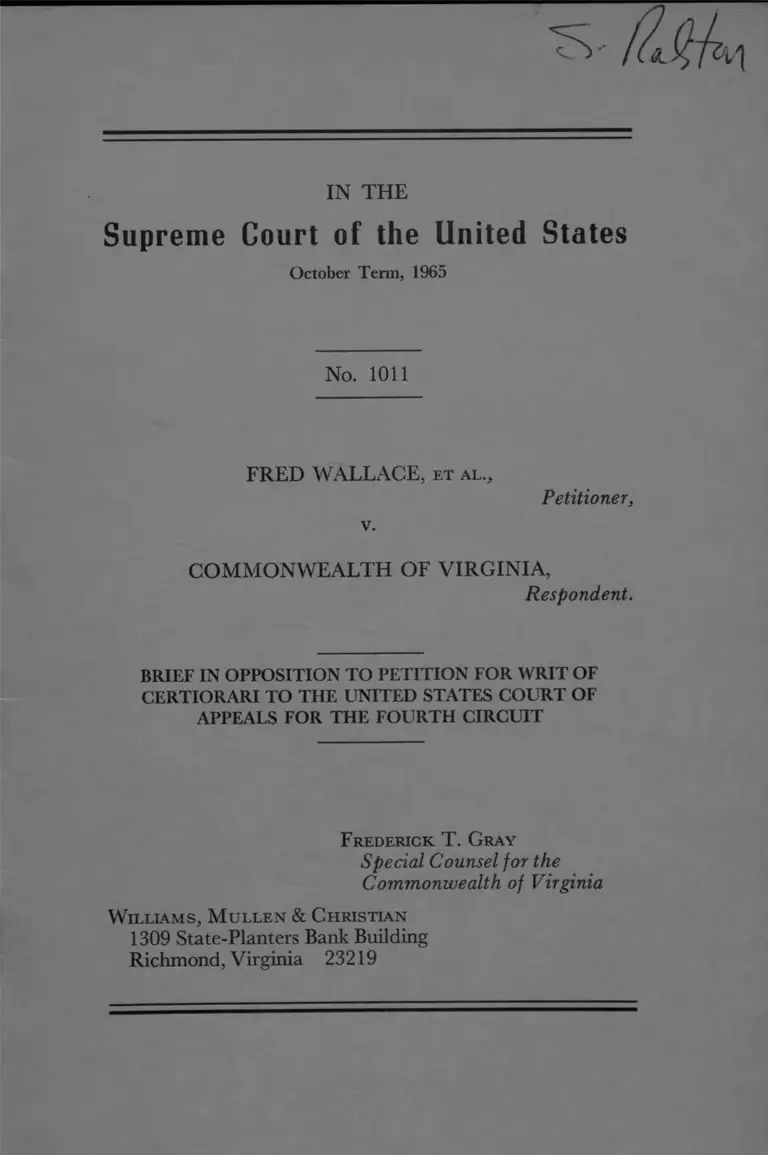

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1965

No. 1011

FRED WALLACE, et al.,

v.

Petitioner,

COM M ONW EALTH OF VIRGINIA,

Respondent.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR WRIT OF

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Frederick T. Gray

Special Counsel for the

Commonwealth of Virginia

W illiams, M ullen & Christian

1309 State-Planters Bank Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Preliminary Statem en t .............................................................................. 1

Argument ......................................................................................................... 2

C on clusion ....................................................................................................... 14

Certificate of Service................................................................................ 14

TABLE OF CASES

Bailey v. Commonwealth, 191 Va. 519, 193 Va. 814 ....................... 9

Baines v. City of Danville, Fourth Circuit, No. 9080 ....................... 3, 8

Clark v. Commonwealth, 167 Va. 472, 189 S.E. 143.......................... 11

Cooper v. State of Alabama, 353 F. 2d 729 ........................................ 7

England v. Louisiana State Board of Medical Examiners, 375

U.S. 411 ............................................................................................. 13

Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U.S. 463, 68 S. Ct. 184, 92 L. ed. 76 ....... 10

Peacock v. City of Greenwood, 347 F. 2d 679 .................................... 2

Rachel v. Georgia, 342 F. 2d 336 ........................................................ 8

United States v. Gugel, 119 F. Supp. 897 ............................................ 6

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U.S. 338 .............................................................. 13

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1965

No. 1011

FRED WALLACE, et al.,

v.

Petitioner,

COM M ONW EALTH OF VIRGINIA,

Respondent.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR WRIT OF

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

This brief is filed on behalf of the Commonwealth of

Virginia in opposition to the granting of the Writ of Cer

tiorari prayed for in the petition. The opposition of the

Commonwealth is bottomed upon the following general

grounds:

1. As to the Wallace Case it is clear that the acts

for which prosecution in a state court are sought are not

such as were done “ under color of authority derived

from any law providing for equal rights” (28 U.S.C.

§ 1443 [2 ]) . The acts for which Wallace is charged are

2

disorderly conduct, using abusive language, obstructing

justice and wounding with intent to maim. If the 14th

Amendment or any Civil Rights Act gives a law clerk

(not an attorney) the right to curse and abuse police

officers and kick his way into the cell block to see his

employer’s clients then there is a possibility that the

Court of Appeals has erred and its decision should be

reviewed.

2. If the Court desires to reverse the doctrine of

“ vertical enforceability” sustained in Virginia v. Rives,

100 U.S. 313, 322 and Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U.S. 1

and grounded upon the elementary principle of comity

and establish instead a rule of conclusive presumption

against the effectiveness of Virginia’s Appellate pro

cedures, then certiorari should be granted in the Wal

lace case. If, on the other hand, this Court considers

the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia capable and

willing to correct any unfairness which may occur in a

trial due to the alleged “ prejudice and animosity” in

Prince Edward County then certiorari should not be

granted on that allegation.

3. If this Court reads the opinions of the Supreme

Court of Appeals of Virginia as approving a practice of

limiting the number of Negroes who serve on juries in

criminal cases then certiorari should be granted.

We submit none of the propositions set forth above should

be determined in a manner favorable to the granting of this

writ.

ARGUMENT

Answer To Petitioner’s Reasons For Granting The Writ

I

Petitioners assert that these cases present many of the same

issues presented in Peacock v. City of Greenwood, 347 F.(2)

679, they fail to state what those issues are.

3

They seem to argue under Section I of their brief that

since Congress has permitted an appeal from a remand order

that it has somehow broadened the scope of removal—

though Congress, while recognizing the limitations, did not

attempt to broaden the scope. As the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit noted in Baines v. City of

Danville, 4th Circuit, No. 9080 (See Appendix III of Peti

tion for Writ of Certiorari herein)

“ There is one final item in the formal legislative

history which may be noticed. When the Congress

provided in Section 901 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

for appellate review of orders remanding removed civil

rights cases, its attention was drawn to the judicial con

struction of the “ cannot enforce” portion of the removal

statute. In the Senate and in the House, there were

expressions of opinion that the Rives-Powers cases in

the Supreme Court were too narrow and that the

Supreme Court should or would relax their rule. Those

expressions reflect no appreciation of the fact that the

reason § 1441(1) was not as useful and available as the

Thirty-ninth Congress may have intended was con

gressional prohibition of post-conviction removal and

not judicial penuriousness in the effectuation of con

gressional intention. If a majority of the Congress in

1964 thought the Supreme Court had misinterpreted the

predecessors of 28 U.S.C.A. § 1443, it did nothing

about it, though attention had been clearly focused on

the subject. Minority expressions of an expectation of

judicial reconsideration of congressional intent is not

the equivalent of congressional redefinition of its inten

tion. The absence of the latter is significant.”

Beyond that, however, it is obvious that Congress did not

intend every criminal case against a member of a minority

group, whose rights are protected by the equal protection

clause, to be “ per se” removable.

4

This obvious conclusion demands, therefore, that we re

view the particular facts to ascertain whether the statute

permits removal.

Laying aside the jury question for later consideration, we

are left with the sole question of whether in the Wallace case

{Morris, et al., involves only the jury question) there are

sufficient grounds to determine (1) that he cannot enforce in

the Courts of Virginia a right under a law providing for equal

rights or (2) that he is being prosecuted for an act done

under color of authority derived from a law providing for

equal rights.

The only ground asserted under (1) above is that there

is intense prejudice and animosity of public officials and

white citizens in Prince Edward County against those advo

cating the end of racial discrimination and particularly

against the law firm with which Wallace was associated.

There is no question in this case about the need for an

opportunity for a hearing because the Courts below con

sidered “ all well pleaded facts as established.” (See Appen

dix to Petition, p. 5a)

Assuming the existence of the alleged prejudice, the ques

tion remains whether Wallace can “ enforce in the Courts of

such State” the equal rights. No hearing is necessary, the

Courts below were required to judge whether the Supreme

Court of Appeals, if necessary, and the Circuit Court of

Greensville County in the first instance would properly

protect Wallace’s rights. We submit that no different an

swers could have been reached.

Under (2) Wallace alleges that he was arrested solely on

account of his race and to prevent and interfere with his

working in defense of persons arrested for protest demon

strations. Herein lies an important aspect of this case. What

act was Wallace doing which led to his arrest and which

5

was “ under color of authority derived from any law provid

ing for equal rights” ?

He was not charged with obstructing traffic while demon

strating or with trespass under circumstances that freedom

of speech, assembly and petition are involved. This man faces

charges of

(1) Unlawfully, feloniously and maliciously kicking, hitting,

wounding, beating, cutting, illtreating and otherwise

injuring J. W. Overton, Jr., a Deputy Sheriff, with in

tent to maim, disfigure, disable and kill.

(2) Becoming disorderly in a public place by cursing.

(3) Cursing and abusing P. F. Gay, a Deputy Sheriff while

he was performing his official duties.

(4) Becoming disorderly in the Sheriff’s Office.

(5) Assaulting P. F. Gay while he was performing his official

duties.

(6) Cursing and abusing J. W. Overton while he was per

forming his official duty.

Those are the acts for which the accused is facing prosecu

tion in Prince Edward County.

What law authorizes any person whomsoever to commit

one of these acts? Can it be seriously contended that the law

of the United States gives the accused “ color of authority”

to curse, abuse, strike, kick and wound law enforcement

officers?

The petition for removal admits the commission of the

acts:

“ The said criminal prosecutions are for acts committed

by petitioner under color of authority derived from a

6

law providing for equal rights * * *” (Italics supplied).

(Petition for Removal, see Appendix of United States

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit)

Thus petitioner admits that he cursed, abused, struck,

kicked and wounded law enforcement officers. He seeks to

justify his actions but what law providing for equal rights

grants any such right?

We are, of course, mindful of the right of one accused of

crime to be represented by counsel. If, as accused alleges,

he was engaged in the representation of such persons there

are adequate lawful means for obtaining access to the client

for interview. We know of no law which authorizes an at

torney to use “ self-help” and fight his way into the cell

block. The accused here shows not a right of his own but

rather he seeks to shield himself with the client’s right— the

right to be represented by counsel.

In the court below petitioner cited the case of United

States v. Gugel, 119 F. Supp. 897, as holding that the oper

ation of a camera is a lawful act, unless made unlawful by

statute, and as such is protected by the Federal Constitution.

But does it follow that one who is wrongfully prohibited from

taking a picture by a police officer can claim color of author

ity of a Federal law if he thereupon assaults the officer?

Of course, Due Process Clause protects the accused in the

pursuit and learning of his profession. But the acts for

which he is being prosecuted are no part of that profession.

He is not under indictment or warrant for representing his

clients or practicing his profession. He is facing prosecu

tion for acts which seem most unbecoming of one who seeks to

become a member of the legal profession.

If, as accused now contends, he was molested and inter

fered with while attempting to attend to his lawful business

he knew, or should have known, that there are legal processes

7

by which such molestation and interference could have been

abated. If it be held that he had authority to conduct himself

as he did, then surely the same authority that is the basis for

removal must operate to grant him total immunity from

prosecution. If the Due Process Clause authorizes him to

curse, hit, kick and wound police officers it is unthinkable

that he can be prosecuted in either State or Federal Courts

for so doing.

Nothing in the recent act of Congress indicates the need

for certiorari herein.

II

Petitioners assert that there in conflict between the Fourth

and Fifth Circuit and that, in their words, “ a mere reading

of the allegations held sufficient in the Peacock opinion, and

in the Fifth Circuit subsequent opinions * * * makes it im

mediately apparent that had Walace’s petition for remand

been filed in a district court in the Fifth Circuit, it would

have been held to state adequate grounds * * * .” (Petition

for a Writ of Certiorari, p. 15) We disagree and would cite

a statement from Cooper v. State of Alabama, 353 Fed. 2d

729, one of the authorities relied upon here by petitioners, to

demonstrate the factual distinction:

“ The same common denominator appears in this case

as in Rachael, Peacock and Cox, viz.:

“ * * * ‘the defendants, as a result of their actions

in advocating civil rights, are being prosecuted

under statutes, valid on their face, for conduct

protected by federal constitutional guarantees or

by federal statutes or by both constitutional and

statutory guarantees.’

Cox v. State of Louisiana, 5 Cir. 1965, 348, F.2d 750,

754-55.”

8

In the Fifth Circuit cases the conduct for which prosecu

tion was sought was constitutionally protected conduct— in

this case the conduct is not lawful even though petitioner

asserts he resorted to such conduct in his effort to help pro

tect the rights of others.

Petitioners say further that a conflict exists between the

Circuits as to whether the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment is a “ law providing for equal civil

rights.” No decision on that question was reached in this case

except by reference to Baines v. City of Danville, supra,

and no such decision was necessary since, as we have

seen, the acts for which prosecutions are sought here are

obviously not protected by the equal protection clause.

The next “ conflict” which is alleged to exist is that the

Fifth Circuit requires a “ factual inquiry.” No conflict exists

with respect to that matter in this case because here the

Court assumed the allegation to have been established. In

other words, the petition for removal was viewed as though

upon a demurrer and ruled to be insufficient even with the

allegations established as correct.

Finally, the alleged “ serious doctrinal conflict” between

the Fourth and Fifth Circuits arising out of Rachel v. Geor

gia, 342 F. 2d 336, and the Baines decision as it involves this

case arises not out of conflict of law but a basic difference in

fact.

In Rachel the petitioners were charged with trespass after

refusing to leave a place of public accommodations when they

were asked to do so because of their race. The Fifth Circuit

correctly observed that they were given the right so to act

under the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title II and, therefore,

removal was appropriate because state legislation on its

face denied the right which the federal act gave. The Fifth

Circuit said:

9

“ Under the allegations of the petitions in the present

case, these appellants have been denied, because of

State legislation, ‘a right under * * * [a] law providing

for the equal civil rights of citizens of the United States.’

They are entitled to a federal forum as provided for in

28 U.S.C.A. Sec. 1443(1) in which to prove these alle

gations. If the allegations are proved, then the federal

court acquires jurisdiction for all purposes. Under

normal circumstances the state prosecutions would then

proceed in the federal court. Here, however, the finding

of the jurisdictional fact immediately brings the Hamm

case into play. The same fact determination requires

dismissal rather than further prosecution in the District

Court.

“ Upon remand, therefore, the trial court should give

appellants an opportunity to prove the allegations in the

removal petition as to the purpose for the arrests and

prosecutions, and in the event it is established that the

removal of the appellants from the various places of

public accommodation was done for racial reasons, then

under authority of the Hamm case it would become the

duty of the district court to order a dismissal of the

prosecutions without further proceedings.”

No clearer distinction could be drawn. Certainly, in this

case no one would suggest that even if the petitioner proves

his case he should be dismissed without further prosecution.

On the facts of this case there are no conflicts between the

Circuits.

Ill

The allegation that the highest Court of Virginia sanctions

a practice of limiting the number of Negroes on juries was

repudiated by the Courts below. That repudiation grew

out of the case of Bailey v. Commonwealth, 191 Va. 519,

and 193 Va. 814. The first Bailey case resulted in a reversal

because the Trial Court refused to receive certain evidence

10

as to discrimination in the selection of jurrors. The Supreme

Court of Appeals of Virginia said:

“Jurors should be selected as individuals, on the

basis of individual qualifications, and not as members

of a race. Proportional representation of race is not a

constitutional requisite. The Constitution requires only

a fair jury, selected without regard to race. ‘An ac

cused is entitled to have charges against him con

sidered by a jury in the selection of which there has

been neither inclusion nor exclusion because of race.’

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282, 287, 70 S. Ct. 629,

632, 94 L. ed. 563, 568. ‘But discrimination in this con

text means purposeful, systematic non-inclusion because

of color.’ The command of the Constitution is ‘that no

State purposefully make jury service turn on color.’ ”

* * *

“ While the ultimate issue was whether there had been

discrimination in the selection of the jury for the trial

of this defendant, the evidence offered was admissible,

though not necessarily conclusive, on that point. Patton

v. Mississippi, supra. ‘Since the issue must be whether

there has been discrimination in the selection of the

jury that has indicted petitioner, it is enough to have

direct evidence based on the statements of the jury

commissioners in the very case. Discrimination may be

proved in other ways than by evidence of long continued

unexplained absence of Negroes from many panels.’

Cassell v. Texas, supra, 339 U. S. at p. 290, 70 S. Ct.

at p. 633, 94 L. ed.atp.570.”

The Court also cited with approval the following state

ment from Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U.S. 463, 68 S. Ct.

184, 92 L. ed. 76:

“ ‘ It is to be noted at once that the indisputable fact

that no Negro had served on a criminal court grand or

petit jury for a period of thirty years created a very

11

strong showing that during that period Negroes were

systematically excluded from jury service because of

race. When such a showing was made, it became a

duty of the State to try to justify such an exclusion

as having been brought about for some reason other

than racial discrimination. The Mississippi Supreme

Court did not conclude, the State did not offer any

evidence, and in fact did not make any claim, that its

officials had abandoned their old jury selection prac

tices.’ ”

The first Bailey case was decided in 1950. At least 14 years

earlier in Clark v. Commonwealth, 167 Va. 472, 189 S.E.

143, the Virginia Court recognized the rule which the ac

cused here says it avoids. In the Clark case the Court said:

“ The Supreme Court of the United States has settled

beyond controversy the proposition that the exclusion

of all negroes from the grand jury by which a negro

is indicted, or from the petit jury by which he is tried,

solely because of their race or color, is a denial of the

equal protection of the laws guaranteed to him by the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution.

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587, 589, 55 S. Ct. 579,

79 F. ed. 1074, and cases there cited.”

The second Bailey case resulted in an affirmance by the

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, the denial of cer

tiorari by this Court, the refusal of habeas corpus in the

Federal District Court, affirmance by the Fourth Circuit

and again a refusal of certiorari here. In other words, every

possible Court heard the contentions as to jury selection in

Virginia and the record fully justifies the statement of the

District Judge here:

“ The Court, however, concludes that the case of

Bailey v. Commonwealth cannot be cited to establish

12

the proposition that in Virginia improper racial dis

crimination in the selection of jurors is permitted. That

case must be considered solely upon the facts that were

presented in it and upon the concessions made by

counsel in argument. It cannot be considered as pre

cedent for the proposition that if the defendant es

tablishes in Prince Edward County factual racial dis

crimination, the Virginia courts will hold as a matter

of law that such discrimination is permissible.

“ The Court reaches that conclusion not only from

reading Bailey, but largely from the case of Bailey v.

Smyth in 220 F. 2d 954 (4th Cir. 1955). Of course, as

we all know, the petitioner in Bailey v. Smyth was the

appellant in Bailey v. Commonwealth.

The Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, at 220

F. 2d 955, points out that one of the grounds upon

which a writ of habeas corpus was sought was “ that

there had been discrimination on the ground of race

in the selection of the jury by which he had been tried.”

They found that such discrimination had not been

established and refused to grant the writ.

They went further and held that the issues could be

determined from the state record.

Therefore, this Court does not see how it can de

termine that the case of Bailey v. Commonwealth in

71 S.E. 2d 368 establishes the proposition which coun

sel for the petitioner urges upon this Court. To do

so, the Court would have to disregard the plain holding

of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in

Bailey v. Smyth, which was based not on the redeter

mination of the facts, but on the law.”

IV

We do not assert that the petitioners have no right to be

heard at some stage in a Federal forum. We do submit, how

ever, that the District Court in its opinion of April 22, 1964,

made the best possible summation of those rights:

13

“ This is not to say that the defendant’s constitutional

rights cannot be claimed and finally adjudicated in a

federal court.

Possibly, the best statement of this right is found in

the last paragraph of Virginia v. Rives, 100 U.S. 338:

‘Undoubtedly, if in the progress of a criminal

prosecution, as well as in the progress of a civil

action, a question arises as to any matter under

the Constitution and laws of the United States,

upon which the defendant may claim protection,

or any benefit in the case, the decision thereon may

be reviewed by the Federal judiciary, which can

examine the case so far, and so far only, as to

determine the correctness of the ruling. If the

decision be erroneous in that respect, it may be

reversed and a new trial had. Provision for such

revision was made in the Twenty-Fifth Section

of the Judiciary Act of 1789, and is retained in

the Revised Statutes. That great act was penned

by Oliver Ellsworth, a member of the convention

which framed the Constitution, and one of the

early chief justices of this court. It may be said to

reflect the views of the founders of the Republic

as to the proper relations between the Federal and

State courts. It gives to the Federal courts the

ultimate decision of Federal questions, without

infringing upon the dignity and independence of

State courts. By it harmony between them is se

cured, the rights of both Federal and State govern

ments maintained, and every privilege and immun

ity which the accused could assert under either can

be enforced.’

Mr. Justice Douglas, concurring in England v. Lou

isiana State Board of Medical Examiners, 375 U.S.

411, 434 (1963), restated that proposition: ‘Cases

where Negroes are prosecuted and convicted in state

courts can find their way expeditiously to this Court

provided they present constitutional questions.’ ”

14

CONCLUSION

We respectfully submit that the Petition for Writ of

Certiorari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

Frederick T. Gray

Special Counsel for the

Commonwealth of Virginia

W illiams, M ullen & C hristian

1309 State-Planters Bank Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that I have served three copies of the foregoing

brief upon Jack Greenberg, Esq.; James M. Nabrit, III,

Esq.; Charles H. Jones, Jr., Esq.; Charles Stephen Ralston,

Esq.; and Melvyn Zarr, Esq.; at 10 Columbus Circle, New

York, N. Y. 10019, also, S. W. Tucker, Esq., and Henry L.

Marsh, III, Esq., 214 E. Clay St., Richmond, Va. 23219,

also, George E. Allen, Sr., Esq., 1809 Staples Mill Rd., Rich

mond, Va., and Anthony G. Amsterdam, Esq., 3400 Chest

nut St., Philadelphia, Pa. 19104, by mail this 26th day of

April, 1966.

Frederick T. Gray