Sweatt v. Painter Appendix to Petition and Brief in Support of Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1948

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sweatt v. Painter Appendix to Petition and Brief in Support of Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1948. 268fbfb5-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/84263c57-733c-40ef-a3b9-20d315693309/sweatt-v-painter-appendix-to-petition-and-brief-in-support-of-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

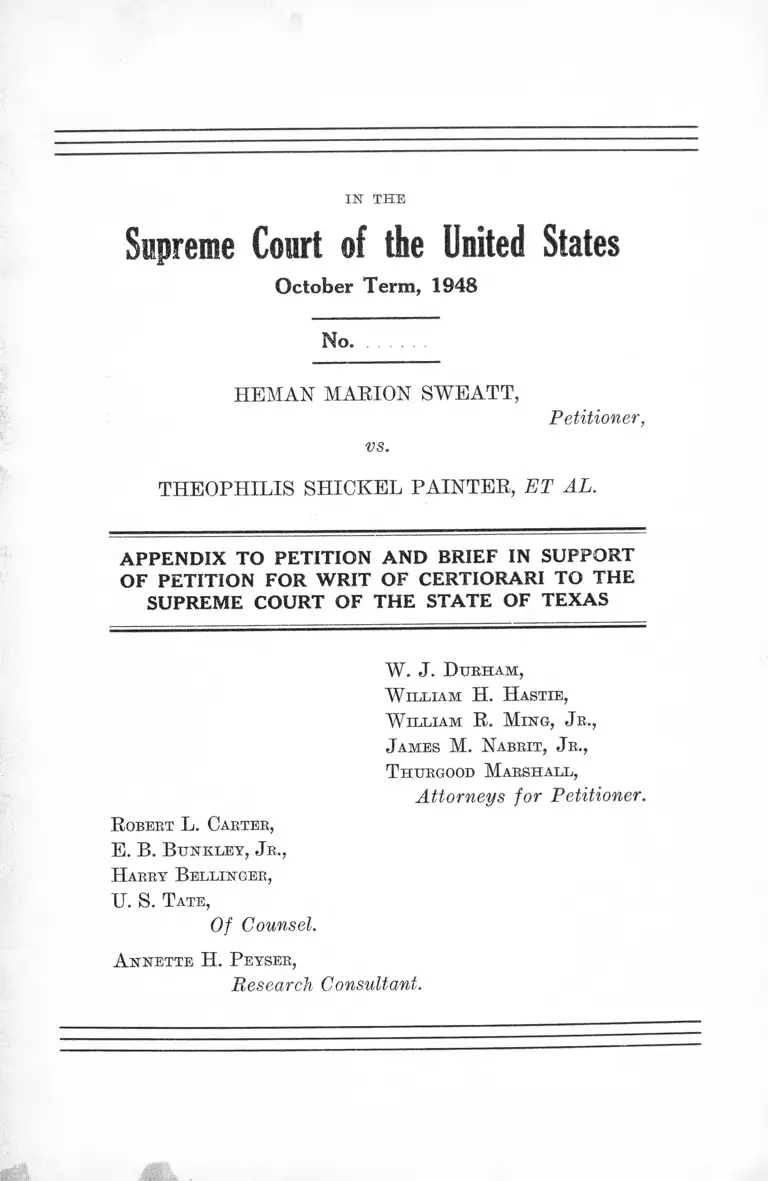

IN T H E

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1948

No.

HEMAN MARION SWEATT,

vs.

Petitioner,

THEOPHILIS SHICKEL PAINTER, ET AL.

APPENDIX TO PETITION AND BRIEF IN SUPPORT

OF PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF TEXAS

W . J . D u rh a m ,

W illiam H . H astie,

W illiam R . M ing , J r .,

J ames M . N abrit, J r .,

T hurgood M arshall,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

R obert L. Carter,

E. B. B unkley , Jr.,

H arry B ellinger,

U. S. T ate,

Of Counsel.

A nnette H . P eyser,

Research, Consultant.

IN TH E

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1948

No.

HEMAN MARION SWEATT,

vs.

Petitioner,

THEOPHILIS SHICKEL PAINTER, ET AL.

A ppendix to P etition F oe W rit op Certioraei

To T he S upreme Court op th e S tate op T exas

i

11

APPENDIX

The following data constitute a portion of a compre

hensive and definitive study which demonstrates the type,

quality, and quantity of the educational facilities available

under the “ separate but equal” formula.

The source material for this study is based upon publi

cations of the United States Department of Education,

publications of other government agencies and bodies, as

well as articles which have appeared in accredited journals

of education.

This portion of the study, which emphasizes the edu

cational inequalities on the higher and professional levels,

is filed to give this Court a true picture of “ separate but

equal” education.

In the seventeen southern states and the District of

Columbia, separate schools are mandatory under law. Of

the remaining thirty-one states, in all but a few segregated

schools are not legal or are actually illegal.1

Approximately ten million or 77% of all Negroes in the

United States live in the southern region, admittedly the

most economically backward section of the country. This

backwardness is overwhelmingly due to the maintenance of

segregation and a caste system which relegates all Negroes

to a position lower than the lowest white. The adamant

stand which the South has taken against the training and

utilization of 22.3% of its human resources, by depriving

1 Reddick, L.D. “ The Education of Negroes in States Where

Separate Schools Are Not Legal,” The Journal of Negro Education,

Summer 1947, Vol. XVI, No. 3, p. 296. The seventeen states requir

ing segregation are: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia,

Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Caro

lina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, West

Virginia, and the District of Columbia.

I ll

its Negro citizens of a fair and equal share of one of the

basic democratic rights—the right to a good education—

means that this right is denied to the very people it seeks

to protect. As President Truman’s Commission on Higher

Education has phrased i t : 2

Segregation lessens the quality of education for

the whites as well. To maintain two school systems

side by side—duplicating even inadequately the

buildings, equipment, and teaching personnel—

means that neither can be of the quality that would

be possible if all the available resources were devoted

to one system, especially not when the States least

able financially to support an adequate educational

program for their youth are the very ones that are

trying to carry a double load.

Thus every southerner suffers from lowered educational

standards, Negroes most severely. Every southerner suf

fers because the maintenance of this dual system demands

that a large percentage of state tax-monies be diverted

away from other fields where it is vitally needed and where

it rightfully belongs. And subsequently the whole nation

suffers because it is bereft of potential talent left unde

veloped.3

Although educational inequities result from segregated

education on every level, it is in the field of higher edu

cation that the results are most easily viewed.

2 Higher Education for American Democracy, Report of the

President’s Commission on Higher Education, Government Printing

Office, Washington, D. C., 1947, Vol. I, p. 34.

3 “We believe that federal funds, supplied by taxpayers all over

the nation, must not be used to support or perpetuate the pattern of

segregation in education, public housing, public health services, or

other public services and facilities generally . . . it believes that

segregation is wrong morally and practically and must not receive

financial support by the whole people.” To Secure These Rights,

recommendation V of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights,

p. 166.

IV

H igher E ducation

The amount and the degree of opportunity, and the ex

tent to which facilities for higher education are available,

are probably the best indices to the educational environ

ment of an area. They reflect the value that the community

places in the education and the maximum achievement of

its people, as well as indicating the general economic and

social conditions of the community itself.

In the 17 states and the District of Columbia, there are

530 institutions of higher learning for whites, 192 public

colleges and universities supported by state and federal

funds included. Institutions for Negroes number 104 in

cluding 39 supported by public funds.4 5 Whereas Negroes

are 22.3% of the southern population, they have but 16.4%

of the total number of institutions providing higher educa

tion in the southern region. More indicative, they have but

16.9% of those supported at public expense, although their

need is proportionately greater. Their proper * share

(22.3%) would entail providing 48 more colleges and uni

versities, 16 to be supported as public institutions.

What does this mean in terms of manpower? 1947 saw

an unprecedented enrollment in colleges and universities

throughout the country with a total of 2,338,226 students

attending classes. 683,235 of these students were enrolled

in southern institutions, making a ratio of students to popu

lation of 1 :66.5 for the region.®

4 Educational Directory, Part 3, “ Colleges and Universities,” U. S.

Office of Education, Washington, 1947.

* By “proper share” we are in no way suggesting a quota, but are

using the population as a means of measuring the adequacy and in

adequacy of facilities and provisions made for the education of Negro

citizens.

5 1947 Fall Enrollment in Higher Educational Institutions, U. S.

Office of Education, November 10, 1947 (Circular No. 238).

V

Enrolled in institutions supported at public expense

were 57.9% of the white students in the South and 54.3% of

the Negro students, while Negroes were only 10.3% of the

total benefiting from these public facilities. Furthermore,

only 5.5% of all expenditures for public institutions in the

South were for Negro colleges and universities.6 The per

cent of Negro students in public institutions should have

been more than doubled and expenditures quadrupled were

they receiving benefits equal to those extended to white

students.* *

Further examination of the data reveals that there

are more institutions both public and private (except in

Delaware) for the use of whites than for Negroes, and which

are consequently more geographically spaced, thereby mak

ing the facilities more readily accessible.

A comparison of the South with the rest of the country

shows further what the duplicated facilities of segregation

mean. Whereas the South maintains more universities and

colleges per 1,000 population than the rest of the nation, its

ability to support them is far less. It may be noted that

even with more institutions, a smaller percentage of the

South’s population as compared with the rest of the coun

try had in 1940 completed four or more years of college. In

1947, there was one student in a southern college or uni

versity for every 66.5 persons in the South, while in the

North and West there was one student for every 52 persons

in the population.

6 Mordecai W. Johnson, Hearings Before Subcommittee on Ap

propriations, House of Representatives, 80th Congress, February 24,

1947, p. 145.

* It is interesting to note that the enrollment in New York Uni

versity in the fall semester of 1947 was 46,312. This is a larger stu

dent body than the total enrollments in 15 of the individual southern

states and the District of Columbia. Only Missouri and Texas had

larger state-wide enrollments than that for this single Northern uni

versity. In this connection, it should also be borne in mind that the

great majority of northern Negroes find it necessary, in the face of

restrictive quotas, to go South for their college education.

VI

We have already indicated the general state of educa

tion prevailing in the southern states. The following data

constitute a specific and graphic demonstration of the in

equities in segregated education.7

1. Southern Negroes are 7.7% of the total United States

population, yet they have only 6.1% of all institutions

of higher education in the country. Southern whites

are 26.7% of the total population, yet they have

31.2% of all the colleges and universities in the coun

try.

2. The South spends 22.3% of all money expended for

higher education in the country, yet Negroes get only

1.8% of this money, while southern whites get 20.5%.

The average expenditure for southern universities

and colleges (even including the Negro institutions)

is over twice the amount spent for the average Negro

institution. Whereas $4.28 is spent per capita white,

only $1.32 is spent per capita Negro population.*

In only 3 states and the District of Columbia does the

number of Negroes enrolled in publicly supported in

stitutions constitute a reasonable percentage of all

students benefiting from such educational provisions

in anything like what their proportion in the popu

lation warrants.

0% 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80

1 1 1 1 1 1 I 1 1 90 100%

1 1

Population lllllllllilllill....... Illllllllllllllllllllll........ ............ ...

Institutions ................................ ................. m m m

Expenditures .. ..............iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii....w m m am m

o%

North and West

South: White

South: Negro

10 20 30 40 SO 60 70 80 90 100%

7 Sources:

The Educational Directory, 1946-47, III, p. 7.

16th Census: 1940, Population, 2nd Series, U. S. Sum

mary, p. 47.

The Journal of Negro Education, Summer 1947, p. 468.

Statistics of Higher Education, 1943-44, p. 70.

* For further data see Charts at the end of Appendix.

vii

It might be asked just how the South manages to sup

port this dual system of education? The answer is self-

evident : by means of segregation which has resulted in the

practice of extensive discrimination as the above charts

indicate. For example, if expenditures in the public insti

tutions for Negroes were equalized on a per capita popu

lation basis, an additional $19,000,000 would have to be

spent for higher education alone. This would raise the

present total expenditures 463%.

Present Share

Proper Share

6 U 12% IStt 25

(in millions of dollars)

Expenditures for Educational Purposes in Public and

Private Colleges and Universities in the 17 States and

the District of Columbia: 1943-44.®

White Institutions Negro Institutions

Expenditures:

Total $150,622,000 $13,438,000

Private 65,033,000 8,149,000*

Public 85,591,000 5,289,000

% of all money expended:

Total 91.8% 8.2%

Private 88.9% 11.1%

Public 94.2% 5.8%

Expenditure per student—■

Total $479.46 $393.16

Expenditure per capita

population:

Total $4.28 $1.32

Public 2.42 .52

College Enrollment:

Total 90% 10%

* Negro private institutions carried about a 50% heavier lead in

terms of expenditures than did private institutions for whites.

9 Adapted from Jenkins, Martin D., “ The Availability of Higher

Education for Negroes in the Southern States,” The Journal of Negro

Education, Op. Cit., pp. 466.

V l l l

At present, the situation is such that Negro private insti

tutions must carry an undue burden in the attempt to fur

nish educational facilities and opportunities to those who

would otherwise be deprived of advanced training. This

process will continue until such time as the southern states

realize that the “ equal but separate doctrine” is economi

cally, and more important, educationally unsound.

The following excerpt from the testimony ottered by Dr.

Mordecai W. Johnson, President of Howard University,

speaks for itself: 10 * *

In states which maintain the segregated system of

education there are about $137,000,000 annually spent

on higher education. Of this sum $126,541,795 (in

cluding $86,000,000 of public funds) is spent on insti

tutions for white youth only; from these institutions

Negroes are rigidly excluded. Only $10,500,000

touches Negroes in any way; in fact, as far as state

supported schools are concerned, less than $5,000,000

directly touches Negroes. . . . The amount of money

spent on higher education by the state and federal

government for Negroes within these states is less

than the budget of the University of Louisiana (in

fact only sixty-five per cent of the budget), which is

maintained for a little over 1,000,000 people in Louis

iana. That is one index; but the most serious index

is this: that this little money is spread over so wide

an area and in such a way that in no one of these

states is there anything approaching a first-class

university opportunity available to Negroes.

In the face of such facts, the amount of money expended

for education assumes extreme importance, becomes, indeed,

so basic to the quality of said education in terms of faculty,

physical plant, educational equipment and curricular scope,

that it renders one as unwilling as he is unable to credit the

10 Johnson, Dr. Mordecai W., Hearings Before Subcommittee on

Appropriations, House of Representatives, 80th Congress, February

24, 1947.

IX

claim made by the southern states that their separate

schools are equal in all respects to those furnished for

whites.

O x the Gbadtjate L evel

A well-known educator recently wrote:12 “ The pro

vision of higher and professional educational opportunities

for Negroes is relatively little better today than fifteen

years ago.” This statement is even more graphic when

viewed contextually: it is mainly within the last fifteen

years that higher and professional education and training

have assumed their broad importance. In the present day

and age of specialization and demand for technical skills,

there is no institution in the South where a Negro may

pursue work leading to a doctorate. The opportunities for

whites are vastly different: doctorates are offered in a pub

lic institution in each of the 17 states as well as in a private

institution in 12 states and the District of Columbia.

There are two accredited schools of medicine for

Negroes in the South, but there are twenty-nine for

whites.

There are two accredited schools of pharmacy for

Negroes in the South, but there are twenty for

whites.

There are two (one provisionally accredited) schools

of law for Negroes in the South, but there are forty

for whites.

There is no accredited school of engineering for

Negroes in the South, but there are thirty-six for

whites.

The chart on the following page demonstrates these

facts graphically.* * 18

12 Thompson, Charles H., The Journal of Negro Education,

Howard University Press, Fall Issue, 1945, Vol. XIV, p. 267.

18 Educational Directory, 1946-7. The quote is from Higher Edu

cation for American Democracy, Vol. I, p. 36, Op. Cit.

Four Year Institutions Supported at Public Expense, Offering Training

in Specified Fields with Departments Accredited by Their

Respective Professional Association: 1946-7.14

W hite :

Law Medicine Dentistry Engineering Pharmacy

Alabama 1 2 1

Arkansas 1 1 1

Delaware 1

D. C.

Florida 1 1 1

Georgia 1 1 1 1

Kentucky 2 1 1 2

Louisiana 1 1 1

Maryland 1 1 1 1 1

Mississippi 1 1 1 1

Missouri 1 1 (2 yr. course) 1

N. Carolina 1 1 (2 yr. course) 1 1

Oklahoma 1 1 2 1

S. Carolina 1 1 3 2

Tennessee 1 1 1 1 1

Texas 1 1 1 * 3 1

Virginia 2 2 1 3 1

West Virginia 1 1 (2 yr. course) 1 1

T otal : 18 15 5 26 13

14 Source: Educational Directory, Part 3, Colleges and Universities, U. S. Office

of Education, 1947.

* Provisionally accredited, or accredited with some reservation, or admitted on

probation.

X I

N egro :

Law Medicine

Alabama

Arkansas

Delaware

D. C. 1

Florida

Georgia

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maryland

Mississippi

Missouri 1 *

N. Carolina

Oklahoma

S. Carolina

Tennessee

Texas

Virginia

West Virginia

T o t a l : 2

1

Dentistry Engineering Pharmacy

1 1

1

1 0 2

14a Source: Educational Directory, Part 3, Colleges and Universities, U. S.

Office of Education, 1947.

A ccrediting A ssociations :

Law: The American Bar Association

Medicine: The American Medical Association

Dentistry: The Council on Dental Education of the American Dental Association

Engineering: The Engineers’ Council for Professional Development

Pharmacy: The American Council on Pharmaceutical Education, Inc.

X ll

The paucity of institutions offering opportunities for

Negroes to pursue graduate and professional work in the

South, coupled with the quota * system of Northern colleges

and universities, has resulted in a serious curtailment of

the number of highly-skilled Negro physicians, lawyers,

engineers, etc. In 1940 there was one skilled Negro and

white out of the following number of the South’s Negro and

white population, respectively: 15

Profession White Negro

Doctors: 843 4,891

Lawyers: 702 27,730

Dentists: (male) 2,589 13,425

Engineers: (male) 655 142,944

Pharmacists: (male) 1,711 25,246

* The President’s Commission on Higher Education comments:

“ The Quota System. At the college level a different form of

discrimination is commonly practiced. Many colleges and uni

versities, especially in their professional schools, maintain a se

lective quota system for admission, under which the chance to

learn, and thereby to become more useful citizens, is denied to

certain minorities, particularly to Negroes and Jews.

“ This practice is a violation of a major American principle and

is contributing to the growing tension in one of the crucial areas

of our democracy.

“ The quota, or numerous clausus, is certainly un-American. . . .

“ The quota system denies the basic American belief that intelli

gence and ability are present in all ethnic groups, that men of

all religious and racial origins should have equal opportunity

to fit themselves for contributing to the common life.

“ Moreover, since the quota system is never applied to all groups

in the Nation’s population, but only to certain ones, we are

forced to conclude that the arguments advanced to justify it are

nothing more than rationalizations to cover either convenience

or the disposition to discriminate. The quota system cannot be

justified on any grounds compatible with democratic principles.”

Higher Education for American Democracy, A Report of the

President’s Commission on Higher Education, Government

Printing Office, Washington, D. C., December, 1947, p. 35.

15 16th Census; 1940, Population, Labor Force.

Xlll

These are the results of segregated education. Broken

down by individual states, the figures show up in even

sharper relief (see Appendix Chart Y for this data).

The implications of the figures presented above are ex

tremely serious. The fallacy that Negroes are not desirous

or capable of absorbing and utilizing specialized training

has often been voiced by people from all parts of our nation.

The findings of such sciences as anthropology, sociology,

and psychology, however, refute these arguments. The

fact is that the opportunities for Negroes are too limited

and too few, in these and other fields as well. As a southern

educator has recently phrased it: “ They don’t teach us

what they blame us for not knowing. ’ ’ 16 That Negroes want

the benefits of more and better education is evidenced by

recent court cases, by the great increase in enrollments in

Negro institutions, and by reports from the schools them

selves. Howard University for the present school year

stated that the total enrollment was over 7,000. The medical

school which can accommodate 70 freshmen had to turn

down 1,180 ably qualified applicants. The pharmacy and

dentistry schools which can each accommodate 50 had over

700 and 500 applicants, respectively.17 And Howard, it must

be remembered, is the only public institution in the South

where Negroes can get professional training in these fields.

These conditions would seem to apply to other schools as

well.*

However, the case for the extension of equal educa

tion for the Negro rests only in part upon his equal

______ educability. The basic social fact is that in a democ-

16 Quoted in Fred H. Hechinger’s column, The Washington Post,

March 7, 1948.

17 The Crisis, November, 1947, p. 324.

*85% of all Negro doctors and 90% of all Negro dentists are

trained at Howard and Meharry, report Henry and Katherine Pringle,

“ The Color Line in Medicine,” The Saturday Eveninq Post, Tanuary

24, 1948.

X IV

racy his status as a citizen should assure him equal

access to educational opportunity.* 18

E ducational Opportunity

Dr. Charles H. Thompson, Dean of the Howard Grad

uate School, reviewing the limited number of trained Negro

professionals, remarks: 19

Whatever other inferences may be drawn from the

facts . . . one of the most important and inevitable

conclusions is that Negroes in the separate school

systems of the 17 states and the District of Columbia

which require racial segregation have been the vic

tims of gross discrimination in the provision of edu

cational opportunities. On the whole Negroes have

had only about one-fourth the educational oppor

tunity afforded to whites in the same school systems,

as indicated by the product turned out.

White WMmmmmwmmmmmm,

Negro h h h h

j, 1 i 1 I 1 1 1 1 1 J 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 I I 1

The following quote demonstrates some of the results

of the conditions described above :

In the 17 states and the District of Columbia the

median years of schooling for the white population

was 8.4; for Negroes the median was 5.1; with a range

for the whites running from 7.9 in Kentucky to 12.1

in the District of Columbia; and for Negroes from

3.9 in Louisiana to 7.6 in the District of Columbia.

Some 13.2% of the white population had completed

4 years of high school as compared with only 2.9%

of the Negroes; 12.1% of the whites had had some

18 Higher Education for American Democracy, Op. Cit., Vol. II,

p. 30.

18 Thompson, Charles H., The Journal of Negro Education,

Howard University Press, Vol. XVI, Summer, 1947, p. 265.

X V

college education, as compared with only 2.5% of the

Negroes; and 4.7% of the white population had had

4 or more years of college as contrasted with only

1.1% of the Negroes. There were, therefore, 4 times

as many whites as Negroes with a high school or

college education in these states which require racial

segregation by law.20

Although it is on the higher and professional levels of

education that the inequities resulting from a segregated

system can best be demonstrated, there are some differ

entials in the indices of education which show up most

graphically in the lower or primary levels. The following

pages will demonstrate some of these differentials.

Inequities in Lower or Primary Education

T he T ax-P ay ee ’s D ollae

White

Negro

$*o I 1 I

25

I - 1 I

50 1 1 1 1 1 100

The tax-payer’s dollar for public education in the South

is divided between the schools for white children and the

schools for Negro children. The average expense per white

pupil in ten southern states in 1944-5 was 189% greater

than the average expense per Negro pupil. Specifically, the

tax-payer paid $88.70 to educate his white citizens and only

$46.95 to educate his Negro citizens.

20 Thompson, Op. Cit., p. 264.

X V I

A verage E xpenditure P er P u pil in A verage

D aily A ttendance : 1944-5 21

State White Negro % White is Greater

Alabama $68.07 $27.62 246%

Arkansas $59.63 $27.22 219%

D. C. (1947) $160.21 $126.52 127%

Florida $108.02 $54.88 197%

Georgia $88.13 $27.88 316%

Louisiana $113.30 $34.06 333%

Maryland $78.00 $69.00 113%

Mississippi * $45.79 $10.10 453%

North Carolina $74.86 $59.26 126%

South Carolina $90.00 $33.00 273%

A verage : $88.70 $46.95 189%

* Per pupil enrolled.

The value of school property in 8 southern states * in

1944-5 amounted in all to $867,960,280.21 22 Distributed, it

looks like this:

(in millions of dollars)

Negroes

$o 100 200

I

300 I I I

400 500 600 700 800 900 1000

On a per capita basis of enrolled students, the picture looks

like this:

White child

Negro child

25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 225 250

In other words, 427.6% more was invested for each white

pupil than for each Negro pupil.

21 The Journal of Negro Education, Howard University Press,

Vol. XVI, Summer, 1947, passim.

* The eight states: Ala., Fla., Ga., Md., Miss., N. C., S. C., Tex.

22 Washington, Alethea H., The Journal of Negro Education,

Howard University Press, Summer Issue, Vol. XVI, 1947, p. 446.

X V II

A verage V alue of S chool P roperty P er P u pil E nrolled :

1944-528

State White Negro % White is Greater

Alabama $143.00 $29.00 493%

Arkansas ** $142.87 $42.59 335%

Florida $284.11 $59.76 475%

Georgia $160.00 $35.00 457%

Louisiana ** $281.97 $50.29 561%

Maryland ** $364.06 $163.69 222%

North Carolina $203.80 $73.08 279%

South Carolina $204.00 $40.00 510%

Texas $230.25 $76.79 300%

Virginia ** $221.51 $85.54 259%

** Data for these states is for 1943-4.

T eachers ’ S alaries

$0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 1400 1600 1800 2000

I I i I I I I I I I I

The amount of salary paid teachers is an important

factor in securing and holding capable teachers. In 1944-5

average salaries for teachers in the South were $1,513.57

for whites and $1,187.28 for Negroes.* * The differential in

the average for whites and Negroes amounted to $326.29,

or phrased differently, the average salary per white was

127.5% greater than that per Negro.

23 The Journal of Negro Education, Summer, 1947, passim, and

Statistics of State School Systems, 1943-44.

* The salary paid Negroes in 1944-5 is lower than the average

salary paid to all teachers in the United States in 1933-34.

XV111

A verage A n n u a l T each ers S alaries : 1944-45 24

State White Negro % Wkite is Greater

Alabama $1,185.50 $ 784.50 158%

Arkansas 1,020.00 624.00 163%

Delaware 1,953.00 1,814.00 108%

Florida 1,757.07 1,174.34 150%

Georgia 1,130.00 540.00 209%

Kentucky 1,085.00 (medians) 1,225.00

208%Louisiana 1,683.33 810.98

Maryland ** 2,085.00 2,002.00 104%

Mississippi 1,018.01 407.81 250%

Missouri 1,239.00 1,519.00

North Carolina 1,294.50 1,305.59

Oklahoma ** 1,428.00 1,438.23

South Carolina 1,314.00 785.50 167%

Tennessee 1,147.36 1,087.88 105%

Texas 1,627.00 1,136.00 143%

Virginia ** 1,364.00 1,129.00 121%

West Virginia

D. C. 3,400.00 3,400.00

A v e r a g e : 1,513.57 1,187.28 127.5%

** Data for these states is from Statistics of State School

Systems, 1943-44.

n.b.

K y.: Heavy concentration of Negro teachers in wealthier city

districts accounts for higher salaries.

M o.: Most Negro teachers are in the 2 largest cities where both

groups are paid higher salaries than elsewhere in the

state.

N. C .: Both groups are paid by the same salary schedule. Negroes

are either better trained or have greater employment

stability.

Tenn.: Negroes had .39 more college years of training.

D. C .: These salaries are estimates. Salary range is from

$3,150-3,750.

Negro students, as reported for 1943-44, received only

$1,349,834 (10 states reporting) out of a total of $43,448,777

spent by these states to take their children to and from

school. Negro students, who in that same year comprised

25% of the school population in the South, received only

3.1% of all funds spent for transportation purposes. 24

24 The Journal of Negro Education, Howard University Press,

Vol. XVI, Summer, 1947, passim.

25 50

% of school population

°/o of funds for transportation

I - I I

0% 25 50

Whereas $6.11 is spent on an average per white child, only

$.59 is similarly spent on each Negro child.25 26 This means

that even when the schools exist, Negro children encounter

far greater difficulties in reaching them.

T ran spo r tatio n E x p e n d it u r e : 1943-4426

State White Negro White Negro

(total) (total) (per capita enrolled student)

Alabama $ 2,520,102 $ 179,927 $ 6.09 $ .79

Arkansas 1,508,979 107,083 5.01 1.07

Delaware 311,064 9.05

D. C. 15,271 .28

Florida 1,589,182 106,168 6.18 1.08

Georgia 2,777,531 71,523 6.52 .28

Kentucky 1,961,947 4.02

Louisiana 3,389,131 12.58

Maryland 1,370,715 231,846 6.10 3.91

Mississippi 3,170,384 60,000 11.52 .22

Missouri 4,270,391 7.31

North Carolina 2,304,334 392,157 4.05 1.53

Oklahoma 2,464,424 192,449 5.77 5.28

South Carolina 1,410,421 8,681 5.66 .04

Tennessee 2,050,277 4.07

Texas 5,888,904 397,663 5.64 1.99

Virginia 2,702,596 6.89

West Virgina 1,995,627 5.20

T o t a l : $42,098,943 $1,349,834 $ 6.11 $ .59

The pattern of inequities resulting from segregation is

uniform throughout the seventeen southern states and the

25 Statistics of State School Systems, Government Printing Office,

Wash., D. C., 1943-44.

26 Ibid.

X X

District of Columbia. In order to demonstrate briefly that

these conditions pertain in Texas, a few data are included

to show the inequities in the lower and higher levels of

education.

E ducational F acilities in th e S tate of T exas

Despite the fact that petitioner’s State of Texas is a

relatively wealthy state, the white median distribution of

state-supported Negro classrooms is 200% greater than the

Negro median.27 If as much money was spent on the aver

age Negro classroom unit as there was for whites, Texas

would have to spend an additional $5,320,000 on its 7,600

Negro units.

The military rejection rates for failure to pass minimum

“ intelligence” standards in the war period of June-July

1943 showed great differentials between the rates for whites

and Negroes. In Texas 10.4% of whites were rejected for

this reason, while the comparative figure for Negroes was

20.5%.28 In 1940 the functional illiteracy in the State of

Texas was 16% for whites, but 36.4% for Negroes. Simi

larly, Texas spent $92.69 in 1947 to educate each white child,

but only $63.12 to educate each Negro child.29 Money in

vested in school property shows a similar pattern; Texas

in 1944 invested $230.25 for each white child and $76.79 for

each Negro child.30

The length of a school term is another index for good

educational standards. In 1943-44 the average school term

for Negroes in Texas was 7.7 days shorter for Negroes than

it was for whites. (This is one-third of a school month.)31

27 Norton, John K., and Lawler, Eugene S., An Inventory of

Public School Expenditures in the United States, Vol. I, pp. 91, 97.

28 The Black and White of Rejections for Military Service, Ameri

can Teachers Associations Studies, 1944, p. 6.

29 The Negro Yearbook, 1947, Tuskegee Institute, p. 76.

30 Statistics of State School Systems, Government Printing Office,

AYash., D. C., 1943-44.

81 Ibid.

X X I

A one-teacher, one-room type of school is ordinarily not the

optimum condition under which to study. In Texas 68%

of the schools for whites were of this type, but the figure

for the Negro child was 81%. The amount of money spent

for school transportation for each white child was $5.64,

whereas only $1.99 was spent for each Negro child.

The present state of higher education in Texas follows

the same patterns of discrimination established on the lower

levels. Certain examples typify how state and federal

funds allocated for the purpose of higher education are dis

proportionately channeled into the institutions for whites

only.

1. In Texas, the highest salary paid a full professor at

Prairie View University (Negro) is lower than the

salary paid (one exception) in any of the 13 other

public institutions for whites.32

2. Texas: “ Public institutions for Negroes do not have

as many students enrolled as the private

institutions. Only 39.8 per cent of all Negro

students enrolled in Texas colleges in 1929

were attending public institutions. This fig

ure increased to 45.2 per cent in 1944. As

far as enrollment is concerned, the burden of

higher learning for Negroes is actually being

carried for Texas by the Negro private col

lege. __Five public and two private colleges

offer courses in engineering for white stud

ents. There is no engineering course for

Negro students in Texas. One public and

one private college offer medicine to white

students. There is no medical school for

Negro students in Texas. With the exception

of teacher-training, nursing, and Divinity, no

professional training is available to Negroes

within the state. ’ ’ 83 * 38

32 See testimony of Dr. Charles H. Thompson in Record of this

case, p. 262.

38 The Journcil of Negro Education, Summer, 1947, p. 431.

X X II

Petitioner has submitted this appendix in order to show

a factual picture of the inequities which have and do result

under a segregated system of education. This picture, as

well as the general pattern of segregation, leads us to agree

with this statement from the Report of the President’s Com

mission on Higher Education:

“ We have proclaimed our faith in education as a

means of equalizing the conditions of men. But there

is grave danger that our present policy will make it

an instrument for creating the very inequalities it

was designed to prevent. If the ladder of educa

tional opportunity rises high at the doors of some

youth and scarcely rises at all at the doors of others,

while at the same time formal education is made a

prerequisite to occupational and social advance, then

education may become the means, not of eliminating

race and class distinctions, but of deepening and

solidifying them.

“ It is obvious, then, that free and universal access

to education, in terms of the interest, ability, and

need of the student, must be a major goal in Amer

ican education. ’ ’ 34

34 Higher Education for American Democracy, A Report of the

President’s Commission on Higher Education, Government Printing

Office, Washington, D. C., December, 1947, Vol. I, p. 36.

XX111

Public Institutions of Higher Education: Texas, 1945-46

Appendix Chart I

W kite

Prairie View

(Negro )

% of population 85.7% 14.3%

Number of institutions * 15 2

% of institutions 88.2% 11.8%

Value of plant & equipment ** $72,790,097 $4,170,910

Value per capita population $12.88 $4.71

Total expenditures $32,007,219 $871,678

Expenditure per capita

population $5.85 $.94

State & Federal appropriation $17,712,820 $297,318

Appropriation per capita

population $3.23 $.32

Total Current income $33,912,086 $914,141

Library expense per year $577,093 $19,720

Number of faculty *** 2,133 (av. 178) 118

Total salaries $8,504,031 $253,133

Average salary $3,987 $2,145

Number of students *** 43,040 1,576

% of all students in public

institutions 96.5% 3.5%

* Unless otherwise indicated these figures are based on 13 insti

tutions for whites and one for Negroes. Data for the others

is not available (Thompson).

** The figure for whites is based on only 11 institutions.

*** The figures for whites are based on 12 institutions.

Data is from reports from the U. S. Office of Education, Form

SRS-21.0-46, Parts I and II.

X X IV

Appendix Chart II

Total Institutions of Higher Learning

North & W est

% of total U. S.

population 65.5%

Total number of

institutions 1066

% of all institutions 64.7%

1 institution per every

............. population 80,978.0

Total expenditures * $573,074,370

% of total expenditures 77.7%

Expenditure per capita

population $6.66

Average expenditure per

institution $537,593

% of total population

with 4 or more years

of college ** 2.9%

% of respective

population

South

Total Negro White

34.5% 7.7% 26.7%

634 104 530

37.3% 6.1% 31.2%

71,524.9 97,586.6 66,410.9

$164,060,000 $13,438,000 $150,622,000

22.3% 1.8% 20.5%

$3.61 $1.32 $4.28

$258,770 $129,212 $284,192

2.0% 0.1% 1.9%

0.5% 2.5%

Sources:

The Educational Directory, 1946-47, III, p. 7.

16th Census: 1940, Population, 2nd Series, U. S. Summary, p. 47.

The Journal of Negro Education, Summer 1947, p. 468.

Statistics of Higher Education, 1943-44, p. 70.

* Since the expenditures for 137 institutions (56 in the South, 81 in the North

and West) were not reported, we made an average of those reporting per insti

tution ($443,608.45), making an additional $59,404,358 thereby changing the total

to $737,134,370 spent on higher education in the United States in 1943-44.

** Percent for the country as a whole is 2.6%.

X X V

Appendix Chart III

Length of School Term: 1943-44

State White Negro

Alabama 169.6 166.1

Arkansas 165.3 141.8

Delaware 181.5 181.7

D. C. 175.0 177.0

Florida 172.4 168.2

Georgia 175.3 165.0

Kentucky 159.2 171.6

Louisiana 180.0 156.7

Maryland 186.7 186.5

Mississippi 165.5 130.0

Missouri 182.4 193.9

North Carolina 179.9 179.9

Oklahoma 169.0 175.8

South Carolina 176.0 160.4

Tennessee 166.7 169.0

Texas 173.9 166.2

Virginia 180.0 180.0

West Virginia 172.1 173.7

A verage :

U. S. A verage:

173.5

175.5

164.0

Statistics of State School Systems, 1943-44, Federal Security

Agency, U. S. Office of Education.

X X V I

Rejection Rates for Failure to Meet Minimum “ Intelligence”

Standards June-July, 1943: The South

Appendix Chart IV

Per Cent Rejected

State White Negro

Alabama 8.5 25.8

Arkansas 9.8 31.1

Delaware *

D. C. 0.6 9.0

Florida 3.4 19.6

Georgia 8.2 27.4

Kentucky 6.1 5.4

Louisiana 6.0 30.6

Maryland 2.0 21.7

Mississippi 5.0 31.1

Missouri 2.1 10.4

North Carolina 10.7 16.3

Oklahoma 3.9 16.1

South Carolina 8.7 43.0

Tennessee 5.6 9.5

Texas 10.4 20.5

Virginia 8.4 18.8

West Virginia 4.7 4.8

The Black and White of Rejections for Military Service, Ameri

can Teachers Association, 1944, p. 6.

* Less than 200 registrants during this period.

Appendix Chart V

Ratio of Professionals to Population by Race: The South, 1940

D octors D e n t is t s L a w y e r s E n g in e e r s P h a r m a c is t s

W N W N W N W N W N

Alabama 1,050 10,034 3,279 25,876 1,133 245,823 860 245,823 2,217 54,627

Arkansas 913 13,657 4,177 36,418 954 122,911 1,396 491,645 2,119 140,470

Delaware 714 4,485 2,305 7,175 941 17,938 218 2,022 4,485

D. C. 308 955 1,113 2,881 100 2,497 151 15,606 651 4,355

Florida 704 5,843 2,050 13,185 507 51,420 637 1,116 20,568

Georgia 850 6,955 2,651 21,699 760 135,616 802 216,985 1,625 49,315

Kentucky 1,070 2,326 3,458 7,380 997 10,192 1,181 71,344 2,626 14,269

Louisiana 686 9,132 2,043 23,314 796 141,551 555 141,551 1,492 24,266

Marvland 536 2,876 1,816 10,411 431 9,435 334 50,322 1,317 21,567

Mississippi 864 19,538 2,837 37,054 850 358,193 682 268,645 1,740 97,689

M issouri 733 1,228 1,588 5,200 661 6,789 616 34,912 1,466 9.399

N. Carolina 1,063 5,911 3,581 16,637 1,061 36,337 1,297 490,649 2,200 30,666

Oklahoma 976 2,156 2,931 8,850 643 6,726 658 28,025 1,669 8,007

S. Carolina 910 11,467 3,410 20,354 938 162,833 905 814,164 1,467 50,885

T ennessee 958 2,292 3,175 6,875 912 31,796 779 254,368 2,035 14,963

Texas 901 5,637 2,882 11,412 709 40,191 592 154,065 1,559 28,887

V irginia 818 3,985 2,604 10,499 636 13,780 551 165,362 1,705 20,044

W . V irginia 1,059 2,560 3,147 4,528 1,230 6,927 742 117,754 3,366 11,775

Total South

Num ber 41,762 2,075 13,596 756 50,107 366 53,763 71 20,572 402

Ratio 843 4,891 2,589 13,425 702 27,730 655 142,944 1,711 25,246

Source: U. S. Census, Population, Labor Force, 1940.

II

A

X

X

XXV111

Rejections of White Registrants in 7 Southern States and

Negro Registrants in 10 Northern and Border States Due to

Failure to Meet Minimum “ Intelligence” Standards, 1943

Appendix Chart VI

New York City

Illinois............

Massachusetts

Michigan........

Indiana ..........

West Virginia .

Ohio .............

Kentucky . . . .

California

Pennsylvania .

Georgia .........

Virginia ........

Alabama ........

South Carolina

Arkansas

Texas ............

North Carolina

(Selective Service Data)

Per Cent Rejected

Negro

White

Source: The Black and White of Rejections for Military Service, American

Teachers Association, 1944.