Moran v. Connecticut Court Opinion

Public Court Documents

August 5, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Moran v. Connecticut Court Opinion, 1977. cdc9b6b4-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/843a86d6-085a-4631-9126-fae13a34a705/moran-v-connecticut-court-opinion. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

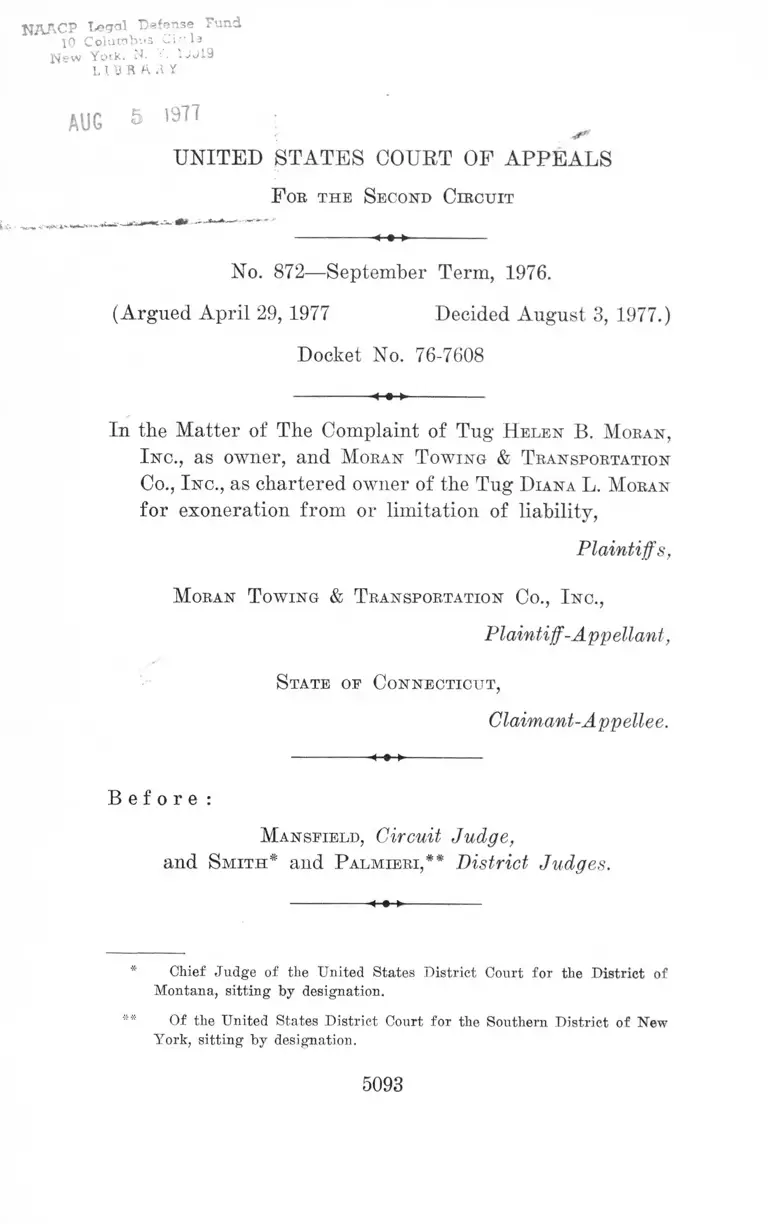

KAACP T-egal Defense Fund

10 Columbus CD-I*

New York. N. 1j j 19

L I B R A H Y

AUG 5 1977

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F oe th e S econd C ibcuit

No. 872—September Term, 1976.

(Argued April 29, 1977 Decided August 3, 1977.)

Docket No. 76-7608

In the Matter of The Complaint of Tug H elen B. M oean,

I n c ., as owner, and M oean T owing & T ranspobtation

Co., I n c ., as chartered owner of the Tug D iana L. M oean

for exoneration from or limitation of liability,

Plaintiffs,

M oean T owing & T ransportation Co., Inc.,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

S tate of Connecticut,

Claimant-Appellee.

B e f o r e :

M ansfield, Circuit Judge,

and S m it h * and P alm ieri,** District Judges.

Chief Judge of the United States District Court for the District o f

Montana, sitting by designation.

Of the United States District Court for the Southern District o f New

York, sitting by designation.

5093

Appeaffrom a judgment denying apportionment of dam

ages resulting from an allision between a vessel and a

drawbridge.

Reversed and remanded.

R obert B. P o h l , Esq., New York, N.Y., for

Plaintiff-Appellant.

D onald M. W aesche, J r ., Esq., New York, N.Y.,

for Claimant-Appellee.

S m it h , District Judge:

The Tomlinson Bridge, which spans Quinnipiac River

near its confluence with Mill River, was completed by the

State of Connecticut in 1925 under a permit granted in

1922 by the Army Corps of Engineers, pursuant to the

authority given by the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1889,

30 Stat. 1151, 33 TJ.S.C. § 401. The bridge is of the bascule-

type construction, with leaves that elevate to allow the

ships to pass.

The approved plans for the bridge specified that the

width of the water between the bridge abutments should

be 126 feet and required that no part of the leaves, when

elevated, would extend over the water. To achieve this

requirement, the leaves must be raised to an angle of 82

degrees above horizontal. The bridge, as constructed, can

not be elevated to an angle of more than 65 degrees above

the horizontal, and the leaves, when elevated, do extend

over the water.

The Tug MORAN, with the Barge BECRAFT in tow,

while passing through the Tomlinson Bridge, was so ma

neuvered that the port side of the BECRAFT rubbed the

granite abutment of the bridge, damaging both the barge

5094

and the bridge.1 The BECRAFT was deflected to the star

board, and shortly thereafter a chock on the port side of

the BEORAFT snagged a girder of the raised bascule leaf

of the bridge, resulting in substantial damage to the leaf.

The State of Connecticut did not have any authorization

from the Chief of Engineers and the Secretary of the Army

to deviate from the approved plans.2 The deviation was a

breach of a statutorily-imposed duty, and it constituted

negligence.

The district court found that the MORAN was negli

gently maneuvered, that such negligence was the cause of

the damage, and, relying on In re Great Lakes Towing Co.,

348 F.Supp. 549 (N.D. 111. 1972), concluded that the negli

gence of the State of Connecticut was not a legal cause of

the damage.

In The Pennsylvania, 86 U.S. 125 (1873), a case involv

ing a collision between moving vessels, the Supreme Court

held that once a ship is shown to have violated a statutory

rule, she then has the burden of proving that her fault

could not have been one of the causes of the accident. The

State of Connecticut could not sustain that burden here.

The chock which struck the girder on the birdge did not

protrude over the side of the barge. The barge was in the

channel, and had the leaves of the bridge not extended over

the channel, there could have been no contact between the

chock and the girder. The violation of the statute was, as

1 The issues relative to the damages resulting from the allision with the

bridge abutment are not before us on this appeal.

2 The Bivers and Harbors Act o f 1899, 30 Stat. 1151, 33 TJ.S.C. §401,

provides in part:

. . . That when plans for any bridge or other structure have been

approved by the Chief o f Engineers and by the Secretary o f the

Army, it shall not be lawful to deviate from such plans either before

or after completion o f the structure unless the modification of said

plans has previously been submitted to and received the approval

o f the Chief o f Engineers and o f the Secretary of the Army.

5095

a matter of fact, a cause of the accident. The district

court in Im re Great Lakes Towing Co., supra, distin

guished between the minor, or passive, negligence of the

bridge owner and the active negligence of the ship and

applied a sometimes-stated tort doctrine which exonerates

one whose passive negligence does no more than create a

static condition which makes the damage possible,3 and

held that the doctrine of The Pennsylvania, supra, did not

apply to bridges.4

3 Many courts have sought to distinguish between the active "cause”

o f the harm and the existing "conditions” upon which that cause

operated. I f the defendant has created only a passive, static con

dition which made the damage possible, he is said not to be liable.

But so far as the fact o f causation is concerned, in the sense of

necessary antecedents which have played an important part in pro

ducing the result, it is quite impossible to distinguish between active

forces and passive situations, particularly since, as is invariably

the case, the latter are the result o f other active forces which have

gone before. I f the defendant spills gasoline about the premises,

he creates a "condition;” but his act may be culpable because of

the danger of fire. When a spark ignites the gasoline, the condition

has done quite as much to bring about the fire as the spark; and

since that is the very risk which the defendant has created, he will

not escape responsibility. Even the lapse o f a considerable time

during which the "condition” remains statie will not necessarily

affect liability; one who digs a trench in the highway may still be

liable to another who falls into it a month afterward. "Cause” and

"condition” still find occasional mention in the decisions; but the

distinction is now almost entirely discredited. So far as it has any

validity at all, it must refer to the type of case where the forces

set in operation by the defendant have come to rest in a position

of apparent safety, and some new force intervenes. But even in

such eases, it is not the distinction between "cause” and "condition”

which is important, but the nature o f the risk and the character

o f the intervening cause. (Footnotes omitted.)

— W. Prosser, The Law o f Torts

247-48 (4th ed. 1971)

4 The district court’s conclusion that the doctrine of The Pennsylvania

86 U.S. 125 (1873), did not apply to bridges was repudiated on appeal

by the Seventh Circuit, although the judgment was affirmed because, at

the time o f the allision, the ship was outside the navigational channel

and in an aiea not protected by the permit. Chicago (f- Western Indiana

B.S. v. Motorship Buko Mam, 505 F.2d 579 (7th Cir. 1974).

5096

We hold that, where the violation of a statutory duty

is a cause of an accident, that liability may not be avoided

on causal grounds by drawing distinctions between active

and passive negligence. It is axiomatic that the wider the

water channel under a drawbridge the less is the likelihood

that passing ships will touch the bridge. To excuse the

negligence which narrows a navigable channel would, in

our opinion, simply frustrate the congressional purpose to

safeguard navigation. This view accords with the rationale

underlying the decision in The Pennsylvania, supra. The

result which we reach is in accord with the decisions in

In re Wasson, 495 F.2d 571 (7th Cir. 1974); The Fort

Fetterman v. South Carolina Highway Department, 261

F.2d 563 (4th Cir. 1958); Petition of McMullen & Pits

Construction Co., 230 F.Supp. 726 (E.D. Wis. 1964); United

States v. Norfolk-Berkley Bridge Corp., 29 F.2d 115, 125

(E.D. Va. 1928).

The failure of the State of Connecticut to comply with

the terms of the permit was a contributory cause of the

allision between the bridge leaf and the chock, and the

damages should be apportioned between the MORAN and

the State of Connecticut.

The judgment is reversed, and the cause is remanded

for further proceedings not inconsistent herewith.

5097

480-8-4-77 USGA— 4221

MEILEN PRESS INC., 445 GREENWICH ST., NEW YORK, N. Y. 10013, (212) 966-4177

219