League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), Council #4434 v. Mattox Memorandum Opinion and Order

Public Court Documents

November 8, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), Council #4434 v. Mattox Memorandum Opinion and Order, 1989. b3711d1e-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/844f93d0-6fc2-4421-ac13-8cc4afe68eac/league-of-united-latin-american-citizens-lulac-council-4434-v-mattox-memorandum-opinion-and-order. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

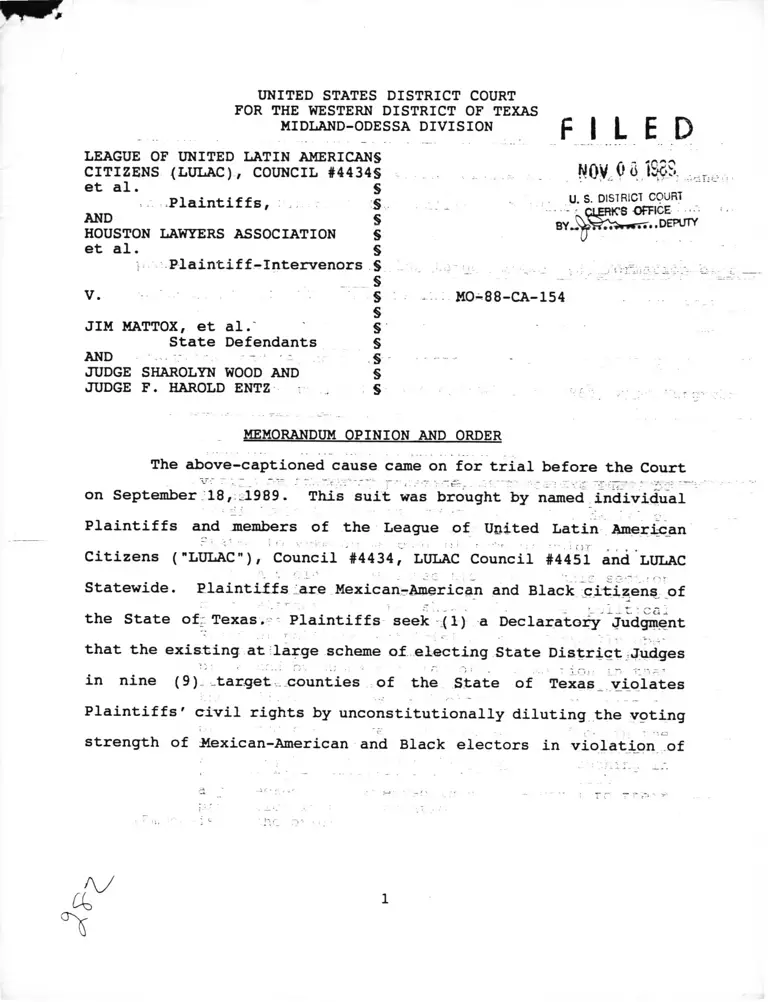

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

MIDLAND-ODESSA DIVISION FI LED

LEAGUE OF UNITED LATIN AMERICANS

CITIZENS (LULAC), COUNCIL #4434§

et al. §

Plaintiffs, §

AND §

HOUSTON LAWYERS ASSOCIATION §

et al. §

Plaintiff-Intervenors §§V. s

§JIM MATTOX, et al.' §

State Defendants §

AND - • §

JUDGE SHAROLYN WOOD AND §

JUDGE F. HAROLD ENTZ §

NOV 08 lS8$. ,,

U. S. DISTRICT COURT. ' ClfFttCS OFFICE

BYi^VW^TT.. DEPUTY

MO-88-CA-154

MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER

The above-captioned cause came on for trial before the Court

on September 18,.1989. This suit was brought by named individual

Plaintiffs and members of the League of United Latin American

Citizens ("LULAC"), Council #4434, LULAC Council #4451 and LULAC

Statewide. Plaintiffs are Mexican-American and Black citizens of

the State of: Texas, Plaintiffs seek (1) a Declaratory Judgment

~ • : \ ; ; •; r - . r : ' c-. • • . . . . . ^ v

that the existing at large scheme of electing State District Judges

in nine (9)- .target counties of the State of Texas violates

Plaintiffs' civil rights by unconstitutionally diluting the voting

strength of Hexican-American and Black electors in violation of

1

«

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C.

S 1973 (West Supp. 1989) ("Voting Rights Act")1; (2) a permanent

injunction prohibiting the calling, holding, supervising or

certifying any future elections for District Judges under the

present at-large scheme in the target areas; (3) formation of . a

judicial districting^scheme by which District Judges__in the target

elected from districts which include single member

districts; and (4) costs and attorneys' -fees. : a*; * rt f -rri ? i:c

This case really had its beginning in 1965, when Congress

Section 2 provides in pertinent part:

"(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to

voting or.standard, practice, or procedure shall be

imposed or applied by any State or political

subdivision in a manner which results in a denial or

abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United

States to vote 'on account of race or color .... ;

"(b) A violation of subsection (a) of this section

is established if, based upon the totality of

tcircumstances, itr> is - shown that the political u

processes leading to nomination or election in the

State" or political subdivision are not.equally open r.. s ;

to participation by members of a class of citizens

protected by subsection (a) of this section in that

its members have less opportunity to participate in

the political process and elect representatives of

their choice. The extent to which members of a

protected class have been elected to office in the '

State or political subdivision is one circumstance

which may be considered: Provided. That nothing in

this section establishes a right to have members of

a protected class elected in numbers equal to their-’ r...."

proportion in the population." \

(Emphasis in the original.) r r::r>-, ...c,, - ..

2

passed the Voting Rights Act and it was signed by President

Johnson. This Act, as everyone knows, had as its purpose -"to -rid

the country of racial discriminating in voting." • --

The next chapter in the saga was the holding in Chisom v.

Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir. 1988), cert, denied, sub nom,

Chisom v. Edwards, 109 S .Ct. 310(1989]-(Chisom I). In Chisom I

Judge Johnson held: "Minorities may not be prevented' from using

Section 2 [of the Voting Rights Act] in their efforts to combat

racial discrimination in the election of state judges; a contrary

result would prohibit minorities from achieving an effective voice

in choosing those individuals society elects to administer -and

interpret the law." ,• • ; -. -- - ---

- Having concluded, as will later be pointed out in formal

Findings of Fact and Conclusions-of Law, that there "is racial

discrimination in the election of state judges in some counties of

the State of Texas, and the law plainly being that uuch

discrimination is prohibited by the Voting Rights Act, this opinion

should not come as any surprise to the attorneys or judges of this

State. ^

Mr. Justice Holmes, in Southern Pacific Co, v. Jensen. 244

U.S. 205, 221, in dissenting, said:

I recognize without hesitation that judges do and - J!

must legislate, but they can do so only intersti—

tially; they are confined from molar to molecular

3

motions.

This dissent has been on the books for 82 years and, while

this Court recognizes that some judges may legislate, this Court

is extremely reluctant to do^so. Legislation should be done by

legislators. This Court has determined that our current system,

as it applies to some counties, violates Section 2 of the Voters,

Rights Act. Some fixing has to be done, because the current system

is broken. n o x ni rr„- r n1- . ,

In writing this opinion, I am cognizant of the fact that our

Texas Constitution will_need to be amended. Legislators should

seriously consider nonpartisan elections for District Judges. As

Chief Judge Tom Phillips, pointed out in his testimony, it really

makes no sense that judges are selected because of their political'

filiation. A judge should decide matters before him without ,

regard to partisan p o l i t i c s I t speaks well of our current

judiciary that our sitting judges have been able to make decisions f

without regard to whether the judge is Republican or Democrat.

As long as judges, ; however, are selected on a partisan

ballot, there will be some rancor and enmity between the successful

the unsuccessful candidate. The loser is going to have regrets

hy virtue of the fact that she or he did not secure enough votes

in an election. It makes no sense to believe that a judge is

4

selected because the top of the ticket is either weak or strong.—

This Court felt the animosity between certain judges in the u.

courtroom. _There is no need for this. Certainly-judicial reform ---

will not make all candidates live by the Golden Rule, but it is a

step in the right direction, x . - •_ .. v. ,;

It was brought to the Court's attention that perhaps a

majority of the voters in a General Election, and for that matter,

in Primary Elections, have no idea of the qualification of a judge

for whom they vote. Their vote is cast because a straight ticket i_La~

is being cast,' 'and a 'straight ticket includes judicial nominees __

from a particular political party.

If the Constitution is to be changed, would it not make

sense to have judges elected when members of school boards or city

councils are elected? These races are traditionally nonpartisan, - 1 7 ?

and people going to the polls to vote for school trustees or mayors L.i: c

have for nthe most part some idea of the qualifications of the

candidates. Judges could be selected at the same time in order to - ̂ ..

make sure that one was not getting votes simply - because one is " n:

Democrat or Republicans Minority voters could go to the polls -

with their heads held high and with some realization that their

preferred candidate either would be or could be elected.

Certainly, it is not Court's intention to tell the

5

legislature how its job is to be accomplished. Single member

districts may or may not be the answer if we are to continue to

have partisan elections. There may be easier and better solutions

that can evolve through the legislative process.

These are troubled- waters. n One liesitates to plunge into

such waters, because our system of selecting judges has, for the.

most part, served us well for many many years. Our Congress,

however, in -1964, made changes. LOur: Courts ’have construed thosei

changes, and it is ' now necessary to move forwardo so that

minorities can realize the rights legally bestowed upon'them, and

which have, in the past, been denied.-

THE PRESENT AT-LARGE SYSTEM , il. „ ^

This litigation ’challenges trhe system of electing 172

District Court Judges at—large from areas composed of entire

counties.2 ■ jl ... . .... :__. v

The present system of electing District Court Judges in

Texas requires that each judge be elected from a District no

smaller than a county. Tex. Const. Art. 5 § 7a(i) (Vernon Supp.

The counties at issue are: Harris, Dallas, Tarrant, Bexar,

Travis, Jefferson, Lubbock, Ector and Midland.

6

1989) .3 - _Each Judge serves a term of four (4) -years.~ Tex. Const.

Art. 5 § 7 (Vernon Supp. 1989). Candidates for District Judge must

be citizens of the United States and the State of Texas, licensed

to practice law in this State and a practicing lawyer or Judge of

a Court in this State, or both combined for four years. Id.

Candidates must have been a resident of that election district for

at least-two |2) years and reside in that district during his or

her term of election. Id. District Court Judges must be nominated

in a primary election by a majority of the votes cast. Texv

Election Code § 172 .DG3=tVernon 1986) . - Each candidate's political -

Party is indicated on the election ballot.Judicial candidates are

usually listed far riown on an election ballot. 'They run for t

specifically numbered courts and must secure a plurality of the

vote in the general election to win a judicial seat. -.ho

s . i - I W T .-n i - • ■ ; i-* r r > r ... C C O i C ; ' "■.; i r 1.0 o f - v . i c -. • . ■ •; : ‘ i ' ' xrc

r- • METHODOLOGY, DATA AND ELECTIONS ANALYZED V : ,, . i&J fa-

Statistical analysis is the common methodology employed and t

accepted to prove the existence of political cohesiveness and

-This system is "at-large" because judges are elected from i

the entire county rather than from geographic subdistricts within -V’ the county. ■-

7

racial bloc voting necessary to establish a voter dilution case.4

Ecological regression analysis5 and extreme case analysis6 were the

types of statistical analysis used by Plaintiffs' experts in the

present case.7

In Thornburg v. Ginales. 478 U.S. 30, 106 S.Ct. 2752, 92

L.Ed.2d 25 (1986), Justice Brennan held thatracial bloc^voting can

be established by a type of abstract statistical inquiry called

"bivariate regression analysis." This analysis correlates the race

of the voters and the level of support given to the candidate.

Id. at-61-» - - If a candidate is supported by a large proportion of

the minority group yet does not win, the vote is declared to be

racially polarized in a legally significant sense and racial bloc

voting is taken to be established.

All-variables beside race of the voters and support given

the candidates that might also explain voters' , choices are

expressly excluded from consideration. In Justice Brennan's view,

"[i ]t is the difference between the choices made by [minorities]

and whites - not the reasons for that difference - that results in

[minorities] having less opportunity than whites to elect their

preferred representatives." Id. at 63.

5c Ecological regression analysis shows the relationship

between the ethnic composition of voting precincts and voting

behavior, i.e.^ which candidate receives how many-votes from each

race/ethnic group. This type of analysis incorporates the 4ise of

a coefficient of correlation or Pearson r, accompanied by an

estimate of the statistical significance of r, the coefficient-Of

determination and the regression line. See Overton v. City of

Austin. 871-F.2d 529, 539 (5th Cir.i 1989) . i.he ' =;-ni :cans ,

6 Extreme case or homogenous precinct, analysisalooks to

homogenous precincts in which almost all of the people of voting

age belong to one ethnic group. If race/ethnicity reflects voting

behavior, then election results in predominately minority precincts

should differ from results in predominately Anglo precincts. .

•j ^The majority which agreed with Justice Brennan that voter

dilution was demonstrated by the'impact or results of the Zimmer

factors and the Gingles threshold analysis deserted him when he

came to the proof of the second and third Gingles factors. -'..

8

The data used by Plaintiffs to support their statistical

analysis varied according to the type of information available to

them since the 1980 Census. Plaintiffs used voting age population

data by census tract to establish the Ginales 1 factor of size and

geographic compactness. Plaintiffs used a variety of data sets to

establish the Singles 2 cohesiveness and Ginales 3 white-bloc

voting factors depending on information available in the County in

question. __

In Counties where Plaintiffs presented a case on behalf of

Hispanics ’• only, they 'relied on ~the percentage of Hispanic

• Justice White maintained that under Justice-Brennan's test

there is racially polarized voting whenever a majority of whites

vote differently from a majority of blacks, regardless of the race

of the candidates. Ginqles. supra, at 83. To illustrate his

disagreement, Justice White posited the hypothetical which assumed

an eight-member multimember district that was 60% white and 40%

black, the blacks being geographically located so that two safe

black single-member districts could be drawn. Justice White

further assumed that there were six white and two black Democrats

running against six white and two black Republicans. Justice White

wrote, "[u ]nder Justice Brennan's test, there would be polarized

voting and a likely § 2 violation if all the Republicans, including

the two;: blacks, are elected, and 80% of the blacks in -the

predominately black areas vote Democratic." Id. at 83. Justice

White concluded that such analysis was "interest—group politics

rather that a rule hedging against racial discrimination." Id. at 83.

Justice O'Connor and the three other Justices for whom she

wrote did not reject bivariate regression analysis solely to

establish political cohesiveness and assess the minority groups

prospects for electoral success. , Id. at 100. However, Justice

0 Connor did reject Justice Brennan's position that evidence that

explains divergent racial voting patterns is irrelevant.

9

registered voters in voting precincts in any given year. These

figures were based on Spanish surname counts done by the Secretary

of State of Texas. In other instances, Plaintiffs used counts of

Black and Hispanic total or voting age population in each.precinct

of a particular county.- When counts were not available, Plaintiffs

based their analysis on 1980 census information. In some counties,

precincts retained the same boundaries reported in the 1980 census.

1980 census data, from precincts with unchanged boundaries were used

in those counties. In several counties, Plaintiffs reconfigured

precinct lines8 and used demographic data from these newly created-

precincts. When relying on census data, Plaintiffs calculated the

number-of non^minorities ̂ within precincts by subtracting the number

of Hispanics and Blacks from the total number of persons within the

precinct. -

Plaintiffs' experts only reviewed elections where a minority

candidate-opposed an Anglo.£ They preferred to analyze general

elections, however primary elections were analyzed when no minority

candidate made it past that stage of the electoral process.

The Supreme Court in Thornburg v. Ginoles. supra, requires

This process requires comparing new precinct maps with

their new lines and census block maps that show racial composition

of the blocks. This process is frequently used to update precinct data.

10

the analysis of several elections to determine if there is a

pattern of voting related to race/ethnicity. In the present case,

when there were District Court elections in a county in question

in which a minority opposed an Anglo, Plaintiffs relied solely on-

analysis of District Court elections. In some Counties this

included both general and primary elections. Where there were not

enough such District Court elections other elections were analyzed.

First, County Court elections in which minorities opposed Anglos

were selected. Next, Plaintiffs turned to Justice of the Peace

elections where the election district was at least as large as a

city within the county at -issue. Finally, if no relevant local

judicial races occurred, Plaintiffs analyzed statewide judicial

elections. See Testimony of Dr. Robert Brischetto.

All jurisdictional:;_ prerequisites necessary to the

maintenance of the claims'of the parties have been fulfilled.

After reviewing the testimony'and exhibits introduced at rtrial, as-

well as the arguments and authorities of counsel, the Court hereby

enters the following Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 52. ....

11

FINDINGS OF FACT

INDIVIDUAL PLAINTIFFS

1. The names and counties of residence-of the ten (10)

named individual Plaintiffs are as follows: (a) Christina Moreno -

Midland; (b) Aquilla Watson - Midland; (cj Joan Ervin - Lubbock;

(d) Matthew W. Plummer, Sr. - Harris; (e) Jim Conley - Bexar; (f)

Volma Overton - Travis; (g) Gene Collins - Ector; (h) Al Price -

Jefferson; - (.i) Mary -Ellen Hicks - Tarrant; and (j) Rev. James

Thomas - Galveston. Each named Plaintiff is a citizen of the

United States registered end -qualified to vote in District Court

elections in Texas.-Except for Christina Moreno, who is Hispanic,

each named Plaintiff Black. j • . 't,.: ''

ORGANIZATIONAL PLAINTIFFS

2. Plaintiffs LULAC #4434 and LULAC #4451 are local

chapters of the larger Statewide LULAC organization. J Members of

the LULAC Statewide organization reside in all of the counties

challenged in this suit. Depo. of John Garcia. The organization

is composed of both Mexican-American and Black residents of the

State of Texas. The members of LULAC #4434 reside in Midland

County. The members of LULAC #4451 reside in Ector County.

3. - i - Plaintif f-Intervenor the Houston Lawyers Association

12

("HLA"), is an association of Black lawyers in Harris County. The

participation of Plaintiff-Intervenor the Texas Black Legislative

Caucus ("TBLC") is limited to the remedy stage of this litigation.

DEFENDANTS & DEFENDANT-INTERVENQRS

4. Defendants are sued in their official capacities only*

Defendant' Jim Mattox is the Attorney General of the

State of Texas and charged with the responsibility of enforcing the

laws of the State. /

Defendant George Bayoud is.-Secretary of-State of Texas.

As such he functions- as chief elections officer charged with

administering the election Jaws of the State. Secretary Bayoud'is

substituted as a party in this litigation for former Secretary of

State Jack Rains. oC 2 . ' . . ) ^ l ... :

Defendants Thomas R. Phillips, Michael J. McCormick, Ron

Chapman, Thomas J. Stovall, James Fr Clawson, Jr., Joe E. Kelly,:

Robert M. Blackmon, Sam M. Paxson, Weldon Kirk, Jeff Walker, Ray

D. Anderson, Leonard Davis and Joe Spurlock, II are members of the

Judicial Districts Board9 created by Art. V Section 7a of the Texas

Several members of the Judicial Districts Board- were

replaced by new members during the interim of this litigation.

Michael J. McCormick replaced John F. Onion, Robert M. Blackman^

replaced Joe B. Evans and Jeff Walker replaced Charles Murray.

13

Constitution and Art. 24.911 et seq. of the Texas Government Code.

The Judicial Districts Board is charged with reapportioning

districts from which District Court Judges are elected. . .. .

----- Sitting- District Court Judge Sharolyn Wood, 127th

District Court, Harris County and Judge Harold Entz, Jr., 194th =

District Court, Dallas County Intervened in their individual

capacities as Defendants.10 ' ;

GINGLES THRESHOLD ANALYSIS

Size and Geographic Compactness

• "5* Harris County. - Harris County has the largest

population among the nine target Counties in this case. Plaintiffs 1

are proceeding only on behalf of Black voters in Harris - County. ror

With a total population of 2,409,544,11 its Black population i s 1 01.

473,698 (19.7%). There are 1,685,024 people of voting age,12 with .--'In

305,986 (18.2%) voting age Black residents of Harris County.

10 Thirteen District Court Judges from Travis County initially - ■ y

intervened as Defendants. The Court struck their intervention at their request. • •.•••

11 In each County, Plaintiffs rely upon the 1980 Census for

total population of Blacks and Hispanics within the County.

For all Counties in this case, Plaintiffs relied on a - -.1-

computer print out of voting age populations prepared by the Data ^-ir:

Center at Texas A&M University _ directly from 1980 U.S. Census~ m e tapes ~ : : • ; T ; 1 h • • •

14

-- There are fifty nine (59) State District Courts in

Harris County. Black residents are concentrated in the North

Central, Central and South Central .sections of Harris County. H-

04, p.> 2, Map, of Proposed Districts.13 Evidence was introduced

that nine (9) Black single member districts of greater than fifty

percent (50%) Black voting age population were possible. Id. at

1; Plaintiff-Intervenor Harris. County ( "P-I.-f H") Exhibits 2, :2a.

6. Dallas County. Dallas County is the second largest

County involved in this case. -Plaintiffs are proceeding only on

behalf of Black voters in Dallas County. Dallas County has a total

population of 1,556,549. Its Black population is 287,613 (18.5%)..

There are 1,106,757 people of voting age, with 180,294 (16%) voting

age Black-residents . Plaintif f s ' DDallSs Ccfiinty ("D",). Exhibit 017-

There were thirty six /(36) State District Courtsmin

Plaintiffs' Harris County ("H") Exhibit 01.

13 Plaintiffs drew districts in each County of approximately

equal size based on the number of District Courts in the County.

Plaintiffs calculated the size and number of precincts in each

proposed district on the basis of both total population and voting

age population. This Court recognizes that the concept of "one man

one vote" does not apply to the judicial elections. Chisom I .

supra, at 1061. Accordingly, this Court's analysis rests upon

Plaintiffs' calculation based upon voting age population.

Plaintiffs drew each district on this basis under the assumption

that each district should contain l/m of the voting age population

in the County,-with n being the number of District Courts in the

County. ‘ -Plaintiffs' Post Trial Brief at 11.

15

Dallas County at the time this case was filed. On September 1,

1989, the Texas Legislature created a thirty-seventh State Judicial

District-Court in Dallas County. Black residents are concentrated

in the Central and South Central sections of Dallas County. D-04,

p. 2, Map of Proposed Districts based on 3̂6 District Courts_

Evidence was introduced that seven (7) Black single member

districts 'of greater than fifty percent (50%) Black" voting age

population were possible. Id. at 1, 3-9;14 Plaintiff-Intervenor

Dallas ("P-I D") Exhibits 34. Plaintiff-Intervenors' Exhibit 7

reflects that there are approximately 36 homogeneous precincts of

90% Black population. __ ___ . _ . _ ___i-.-t ___ .

7 Tarrant County. Plaintiffs are proceeding-only on

behalfr of Black voters in Tarrant County. Tarrant County has a

total ^population of 860,880> ̂The rBlack population-of "Tarrant

County is 101,183 (11.8%). There are 613,698 people of voting age,

with 63,851 -(10.4%) voting age'Black residents of Tarrant County.

Plaintiffs' Tarrant County ("Ta") Exhibit 01. .*

There are twenty three (23) State District Courts in

Tarrant County. Black residents are concentrated in the Center of

Proposed single member districts 1 & 3 barely meet the

Overton majority - minority voting age population requirement.

These proposed districts contain 51.33% and 52.05% black voting age

population respectively.

16

Evidencethe County. Ta-04, p. 2, Map of Proposed Districts,

was introduced that two (2) Black single member districts of

greater than fifty percent (50%) Black voting age population were

possible. Id. at 1_., , :=;• i.'V' ' :: 1-h= -,-.vr

8. Jexar County. Plaintiffs are proceeding only on behalf

of Hispanic voters in Bexar County. _ ;.Bexar County - has a .total

population of 988,800. Its Hispanic population is 460,911

(46.61%). There are 672,220 people iof vating1-age with 278,577

(41.1%) voting age Hispanic residents of Bexar County.e-

Plaintiffs' Bexar County~("B") Exhibit 01. --

There are nineteen (19) State District Courts in Bexar

County. Hispanic residents are concentrated in the Central and

South Central sections of the County comprising most of the

population! of the City of San Antonio. B-04, p.-2, Map of

Proposed Districts. Evidence, was introduced ithat eight (8}r

Hispanic single member districtsvof greater than .fifty percent

(50%) Black voting age population were possible. Id. at 1.

9. Travis County. Plaintiffs are proceeding only on

behalf of Hispanic voters in Travis County. With a total

population of 419,335, its Hispanic population is 72,271 (17.2%).

There are 312,392 people of voting age with 44,847 (14.4%) voting

age Hispanic residents of Travis County. Plaintiffs' Travis

17

There are thirteen (13) State District Courts in Travis.

County. The largest concentration of Hispanic residents in one

area, if at all, appears to be located in the Eastern portion of

the County. Tr-04, p. .2; Tr-05, p.l, Map of Proposed Districts.

Mr. David Richards testified that in his opinion the Hispanic

community was pretty ~ - well ~ dispersed in “'Travis County.

Nevertheless, evidence! was _ introduced that one (1) !combined

minority single member district of greater than fifty’percent (50%)

Hispanic voting age population was possible. Id. at 1.

Plaintiffs! Exhibit Tr-04 depicts the single member -. Hispanic

district proposed for Travis County, v The Court finds that"it is

without moment that the proposed district appears to be minimally

contiguous. ■ ' .• Courts i r . i

10. Jefferson County. Plaintiffs are proceeding only on

behalf of Black voters in Jefferson County. cJefferson County has

a total population of 250,938. Its Black population is 70,810

(28.2%). There are 179,708 people of voting age of. which there are

44,283 (24.6%) voting age Black residents of Jefferson County.

Plaintiffs' Jefferson County ("J") Exhibit 01.

There are eight (8) State District Courts in Jefferson

County-r Black residents are concentrated in the Central and South

County ("Tr") Exhibit 01.

18

Eastern portions of Jefferson County. J-04, p. 2, Map of Proposed

Districts. ''Evidence was'^introduced that two (2) Black single

member districts of greater than fifty percent (50%) Black voting

age population were possible. Id. at 1 ’ - J ’- « —

11. Lubbock County. Plaintiffs are proceeding on behalf • n>.

of the combined Black and Hispanic voters in LLubbock County. .There ...

is a total population of 211,651 in Lubbock County. The Black ^ _.

population of Lubbock County is;15,780 (7-5%), while the Hispanic

population is 41,428 (19.6%). There are-150,714 people of voting ;

age, with 9,590 (6.4%) voting age Black residents and 22,934 ;

(15.2%) voting age Hispanic residents. The combined minority

votings age : population is 32,524 (21.6%). Plaintiffs' Lubbock'■ ;:al r

County ("L") Exhibit 01. : * ; ( ,

There are six (6) State District Courts in the Lubbock----.. -

Crosby County area. The combined minority population is non -

concentrated in thes.North Eastern, Eastern and South Eastern Lons

sections of those Counties. L-04, p. 2, Map of Proposed Districts.

Evidence was introduced that one (1) combined minority single

member district of greater than fifty percent (50%) Black voting

age population was possible. Id. at 1. This remains true when

Plaintiffs controlled for voting age population of non-United Vs

States citizens of Spanish origin. Plaintiffs' Exhibit L-ll. •• -V

19

12. Ector County. Plaintiffs are proceeding on behalf of

combined Black and Hispanic voters in Ector County.... The total

population of Ector County is 115,374. Its Black population is

5,154 (4.5%) and the Hispanic population is 24,831 (21.5%). There.

are 79,516 people of voting age. The voting age population by

minorities consists of 3,255 (4.1%) Black voters and 14,147 (17.8%)

Hispanic voters for a combined minority voting age population of

17,402 (21.9%). Plaintiffs' Ector County ("E") Exhibit 01.

■"7There are four (4) State District Courts in Ector

County.' Minority residents are "concentrated in the Southwest

section of the County. E-04, p. 2, Map of Proposed Districts.

Evidence -was introduced that-one (1) combined minority single

member district of greater than fifty percent (50%) minority voting

age population was possible. Id. at 1. It is possible to draw a

district of combined minority population of voting age even if non

citizen voting age HiSpanics are eliminated -from .the calculations.

Plaintiffs' Exhibit E-13. •_ - ,

13.: Midland County. Plaintiffs proceed on behalf of Black

and Hispanic voters combined in Midland County. Midland County has

a total population of 82,636. Its Black population is 7,119 (8.6%)

and its Hispanic population is 12,323.(14.9%). There are 57,789

r hr >— v* r f

people of.voting age,.-4,484 (7.8%) voting age Black voters and

20

6,893 (11.9%) voting age Hispanic voters. The combined voting age

population is 11,377 (19.7%). ̂Plaintiffs' Midland County ("M")'

Exhibit 01. ------ — -

There are three (3) State District Courts "in Midland

County. Black residents ~are concentrated largely in the

Northeastern, East Central and Southeastern sections of Midland

County. M-04, p. 2, Map of Proposed Districts. Evidence was

introduced^that one (1) combined minority single member district

of greater than fifty percent (50%) combined voting age population

was possible. Id. at 1. It'is possible to draw a district in

which the combined minority population is in the majority even if

non-citizen Hrspanics of 'voting age are excluded. Plaintiffs'

Exhibit M-15.

Political Cohesion and White Bloc Voting

14. Racially polar-ized voting indicates that the group

prefers candidates of a particular race.15 ‘Monroe v. City of'

Woodyille, No.' 88-4433, slip op. at 5573, (5th Cir. Aug. 30, 1989).

The Supreme Court in Ginqles adopted the definition of

racial polarization offered by Dr. Bernard Grofman, appellees'

expert.-Dr. Grofman explained that racial polarization "'exists

where there is a consistent relationship between [the] race of the

voter and the way in which the voter votes' ... or to put it

differently, where 'black voters and white voters vote

differently.'" Ginqles. 478 U.S. at 53 n. 21.

21

Political cohesion, on the other hand, implies that the group

generally .unites behind a single political "platform" of common

goals and common means by which to achieve them. Id.at 5573.

The inquiry into political cohesiveness is not. to be

made prior to and apart from a study of polarized voting. The

Supreme Court made clear that "[t]he purpose of inquiring into the

existence of racially polarized voting is twofold: to ascertain

whether minority group members constitute a politically cohesive

unit and to determine whether whites vote sufficiently as a bloc

usually to defeat the minority's preferred candidates." Gingles,:.

478 U.S. at 56.

15. Plaintiffs presented testimony of two experts. - Dr.

Richard Engstrom ("Dr. Engstrom") testified only about Harris and

Dallas j.Counties. Dr. Robert r.Brischetto ("Dr. Brischetto")

t. '* r.-. T O - ’ T i m o r . V O t D r . F T 1- s >« r’ .V OU! j i; . i r

testified concerning all other counties at issue in this case.:

16. Harris County.

a. Dr. Richard Engstrom testified on behalf of Plaintiffs

and Plaintiff-Intervenors in Harris C o u n t y D r . Engstrom used 1980

U.S. Census counts of total Black population by precinct to analyze

1980 election results. For .1982, 1984, 1986 and 1988, Dr. Engstrom

used precinct voter registration estimates supplied by Dr. Richard

Murray, a non-testifying expert. K.Plaintiffs' Exhibit P-I H-08ri-

22

Dr. Engstrom verified or "matched" the reliability of Dr. Murray's

estimates and the 1980 Census counts by comparing Dr. Murray's

estimates to an Hispanic precinct voter registration list compiled

by the Secretary of State; Testimony of Dr. Richard Engstrom.

Dr. Engstrom testified that there was "a very good: match.",

b..̂ . Dr-Engstrom analyzed,17 _ general elections in Harris

County. He calculated "r". values16 between 0.798 and 0.880 for the

17 elections analyzed.17 tPlaintiffs' Exhibit P-I H-01 pp. 1-2.

Dr. Engstrom's regression analysis shows a strong relationship

between race and voting patterns in Harris County. See Appendix.

A to this opinion ("Appendix"), Plaintiffs' Exhibit P-I H-01 pp.

1-2. All of his correlation coefficients18 exceed .79 (79%) except;

16 The "r" value describes the relationship between the racial

composition of a precinct and ..the number of votes a particular

candidate receives. Testimony of Dr. Engstrom. To put it another

way, "how consistently a vote for Black candidate changes as the

racial composition of the precinct changes." Id.

"Crucial to the validity of regression analysis are .the

values for 'r' and 'r[squared]' , which measure the strength of the

correlation and linear relationship of the variables being

examined, in this case the race of the voter and the candidate he

supports." Overton, 871 F.2d at 539.

The "r" value is also referred to as the "correlation

coefficient" or "Pearson r." A positive Pearson r shows that as

the percentage of minorities in a precinct increases, so does the

support that a minority candidate receives. A Pearson r of -1

shows the opposite, as the percentage of minorities in a precinct

increases, cthere is decrease in the support that a minority

candidate receives. A Pearson r of 0 shows that there is no

23

one. Id.., see section on Bivariate Regression under the column

heading of Correlation Coefficient. Dr. Robert Brischetto

generally testified with regard to the counties in issue other than

Dallas and Harris County, that a ..Pearson r of 1 (100%) would show

perfect correlation. He further testified that social scientists -

consider anything over 0.50 (50%) as showing a strong correlation.

c. Further, each Pearson r is accompanied by an estimate

of the likelihood that the estimate would occur by chance. This

figure is known as the significance level. In the regression

analyses for Harris County, as well as all the counties in issue,

the significance level was much smaller than the generally accepted

level of extremely high significance of . 05.19 Testimony of Dr.

Robert Brischetto; Testimony of Dr. Richard Engstrom. Dr. Engstrom

testified that the probability that the Harris County estimates--

would have occurred by chance were less than 1 out of 10,000.

H d. The lowest squared for these analyses is “

approximately .62 (62%). This describes the percentage of the

variance in voting behavior explained by race/ethnicity. Testimony

relationship between the racial/ethnic composition of precincts and

voting behavior. 1 , • . •

19 A -significance level of -.01, for example, ;means that the

Pearson r in question would have occurred by chance only one time

out of .one hundred. Cvcx ■ : - -j. " G r

24

of Dr. Robert Brischetto.20 Squaring these "r" values21 to

calculate coefficients of determination demonstrates in the present

case that race explains at least 62% of the variance in voting in

all 17-elections relied on by Plaintiffs and Plaintif f-Intervenors.._

m e . t= The one judicial race that did not exceed the 79%

figure actually had a negative correlation. This race involved

Mamie Proctor, a Black candidate running on a Republican ticket

against Henry Schuble, an Anglo, for State Family Court 245. In

the 1986 Proctor race, the correlation coefficient was -0.836

(approx. -84%). Id. at 1; Plaintiffs' Exhibit P-I H-10 p. 2. ..This

reflects that, as the percentage of Blacks in voting precincts

increases, 'Proctor*s support decreased. In other words, even

though Ms. Proctor is Black, she did not receive the support of the

Black community. Hence, she was not the preferred, .candidate of ;

Black voters in Harris County. Dr. Engstrom testified on cross

examination tJhat the "candidate of choice" .was the-candidate who

For example, if a Pearson r is .5, then 25% (5 x 5 or r

squared) of the variance in voting behavior is explained by

race/ethnicity.

This figure is also known as the coefficient of

determination. It is the coefficient of correlation or Pearson r

multiplied by itself. It shows how much or little "noise" there

is around the line ofT correlation or, in other words, "the

percentage of variance in the vote that is explained by the race

of the voters." Overton, 871 F.2d at 539 n. 11.

25

received the majority of the black vote, not necessarily the Black

candidate. - - : • - -

f. When Dr. Engstrom controlled for Hispanic votes, Dr.

Engstrom's regression analysis shows that Blacks consistently gave —

more than 97% of their vote to their preferred candidate. Id., see r

last two columns. - , .J

g. Dr. Engstrom's homogenous precinct analysis

corroborates the results of his regression analysis .t> See Appendix ;

A, Plaintiffs' Exhibit P-I H-01 pp. 1-2. It shows that Black

voters in Harris County gave more than 96% of their votes to the

preferred candidate of Black voters in every election except

Proctor's . : Ms . Proctor received 5% of the Black vote. ~

' - h . ~ Finally, in all counties including Harris County,

Plaintiffs "weighted"1 precinct data in f order 'to account for

variations in the population size of the various precincts.

Testimony of Dr. Richard Engstrom; O v e r t o n rsupra, at 537. Dr. 1-

Engstrom testified that on the basis of his analysis the Blackc

community in Harris County votes cohesively in-general elections

for State District Court Judges. i. Harris County

Defendant-Intervenor Judge Sharolyn Wood-("Judge Wood"), attacks:-^-

Plaintiffs and Plaintiff-Intervenor's proof on the following’:

grounds: (1) Dr. Engstrom failed to establish the reliability of

26

his data set; (2) absentee votes were not allocated to election

returns; (3) the analysis does not reflect the effect of the influx

of the Vietnamese population into Harris County and traditionally

Black -precincts; and {4) the .analysis fails to reflect black

candidate successes in primary elections or uncontested races.-- -■

j. In reference to the reliability of the data set, Judge

Wood points to numbers on Dr. Murray's printouts that have been

written over.,: struck out or crossed through, pencil notations and

other marks. This Court finds the data set to be reliable.

k. - ..In response to the other concerns, Dr. Engstrom

testified that: (1) primary elections were not examined in Harris

County because those elections were not filtering out the candidate

of choice of Black voters; (2) uncontested races do not assist

researchers in their analysis; (3) the appropriate comparison in

Voting Rights cases is Black and non-Black; (4) while :he did not

specifically control for Asian Americans, they would be included

in the percentage of non-Black votes; and (5) the range of absentee

votes between 1980 and 1986 never exceeded 2.2% to 7.6%, while in

1988 that range rose to approximately 13.6% per precinct. This

Court finds that Dr. Engstrom's testimony adequately addresses

these concerns. The Court further finds that the lack of control

for absentee votes and Asian Americans does not significantly

27

affect Dr. Engstronr's analysis.

-1. The State Defendants and Defendant-Intervenors argue

that it is a candidate's political party and the strength of

straight ticket party voting that determines ~the result of any

election contest and not the difference between the preferred

candidates of whites and minorities. In support.of -this argument,

Defendants and Defendant-Intervenors point to the.1982 and 1986

Democratic sweep for judicial candidates in- Harris County and a

similar Republican sweep in the years 1984 and 1988. n All

Defendants attribute this phenomenon to top of the ticket straight

party voting.22

m. Correlation and regression can also prove the third

Ginqles prong by showing that a white bloc vote exis-ts. This is

shown when the percentage of ■ votes received by .'the minority

candidate decreases as the percentage of minority persons of voting

age decreases . In other twords, the minority candidate^receives

fewer votes as the percentage of non-minority persons in a precinct

increases.; Regression results estimate the percentage of non

minority support for minority candidates, otherwise known as the

In 1982, Senator Lloyd Bentsen was the lead Democratic

candidate on the ballot. In 1986, Governor Mark White represented

the top of the ticket Democratic candidate. In Presidential

election years 1984 and 1988, President Ronald Reagan and President

George Bush, respectively, were the top Republican candidates.

28

Anglo cross over vote. Plaintiffs' Exhibit P-I H-01 pp. 1-2,

column 4. This is also referred to as the Y intercept. . .. ..

n. Dr. Engstrom calculated Y intercepts for the Black

preferred candidate between 29 and 39 percent for the 17 elections

analyzed. The highest Y intercept was 33.6%, but this percentage

of the non-Black vote was for the non-preferred candidate Mamie

Proctor. The highest percentage of Anglo cross over votes

received by the preferred candidate of Black voters was 39 percent.

See 1986 race Carl Walker, Jr., Black Democrat against George

Godwin; Id. This is corroborated by a 40% Anglo cross over vote

figure calculated for the same race in homogenous precincts of 90%

or more non-Black population. Td. at column 1. Mr. Walker was

the Black preferred candidate and won. > Plaintiffs' Exhibit P-I H

10. Two other Black preferred-candidates-drawing opposition .inJthe

1986 elections lost their elections even though they had identical

Black community support; These two candidates had slightly?.less;

Anglo cross over vote. Plaintiffs' Exhibit P-I H-01 pp* J.-2,

column 1. Five other Black preferred candidates drawing opposition

in what appears to be county-wide elections lost in t h e -1986

elections. -= Plaintiffs' Exhibit P-I H-10.23 This ianalysis

j These candidates are: Bonnie Fitch, Raymond Fisher,

Francis Williams, Sheila Jackson Lee, and Cheryl Irvin-ar.

29

demonstrates that an Anglo bloc vote exists. Dr. Engstrom

testified that the Anglo or white bloc vote in Harris County is

sufficiently strong to generally defeat the choice of the Black

community-.-*- This Court a g r e e s -? •- r :•1 r- ,-.

o. Plaintiff-Intervenor Sheila Jackson Lee also testified

about political cohesiveness among Black voters in .Harris County.

Ms. Lee has lived in Harris County approximately 11 years and has

been a candidate in several- judicial^ e l e c t i o n s P l a i n t i f f s '

Exhibit P-I H-01 pp. 1-2; Exhibit P-I H-10 pp. 1-3. She had many

different endorsements and campaign strategies but still lost.

She testified that her loss was attributable to not getting enough

white votes. f •. v 1^3 ^Urv.. ]•••••'••• : • • • - r. i.V J . \

p. This testimony was supported by the deposition

summaries of Thomas Routt,! Weldon Berry, Francis -Williams and

Bonnie Fitch. _,ul' v r.-

q. Defendant-Intervenor Wood presented the testimony^of

Judge Mark Davidson. As a hobby, Judge Davidson analyzes the

results of judicial elections in Harris County. His testimony

concerned his views on what he has termed "discretionary judicial

voters" ("DJV").24 Judge Davidson testified that 15% of the vote

He defines DJV's as voters who vote for at least one

judicial candidate of one party and at least one of the other

party. DJV's are also referred to as "swing" voters.

30

in judicial elections in Harris County were DJV's. The remaining

85% split roughly evenly between straight . Democrat party and:

straight Republican party voting. Based upon his analysis, Judge

Davidson believes that race and ethnicity are irrelevant_to voting.,

behavior as it relates to. ;the .judiciary in Harris County. : Hew

opines that DJV's determine the outcome of judicial contests in

Harris County and the DJV vote can somewhat be garnered by various

campaign factors. While this Court finds Judge Davidson to be a

credible witness, under controlling law, the Court finds that his

testimony is irrelevant. _

r. The Court further finds Defendant-Intervenor Wood's

contention that -the Black preferred candidate lost their respective

judicial races due to their failure to win the Harris County bar

or preference poll orito" obtain the Gay Political Caucus ("GPC"),

endorsement to be legally incompetent.

s. The complete data set used by Dr. Engstrom was used by

Defendant's expert, Dr. Delbert Taebel for his analysis of Harris

County. Dr. Taebel did not weight his precinct data to.account for

variations in population size of various precincts in Harris County

or any other county at issue.

t. Dr. Taebel analyzed 23 District Court general elections

where minorities opposed white candidates -in Harris C o u n t y S t a t e '

31

Defendants' Exhibit D-05 pp. 9, 13, 29, 33, 37, 41, 45, 53, 61, 81,

85, 89, 93, 97, 101, 105, 137, 141, 145, 161, 165, 173 & 177.-

Black and white voters voted differently in all 23 District Court

elections. Id. The Blackr preferred candidate won"only six'(6)"

times." The Black preferred candidate won seven (7) of 11 County

Court general elections. Id. D-05-pp. -lr 5, 17^-21, 25, 109, 113,-

117, 121, 175 & 129. Blacks and whites voted differently in each

of those elections . Id.a mDr. * -Taebel i also analyzed >nine r ( 9 ) h

judicial primary elections; seven (7) for District Court posts and

two (2)-County Court posts. Id. D-05 pp. 49, 57, 65, 73, 77, 145

157, 169 & 181. The Black preferred candidate won six (6) of the

nine (9) primaries. Interestingly enough, each preferred candidate

winning the primary lost the general election. Id. D-05 pp. 61,

69, 81, 153,: 161, & 17 3 . ~ v;-.v • v — -i-i

17. Dallas County.: - ~ >' ̂qu ~ • m - -

a. Dr. Engstrora used the same data set for his analysis

of Dallas County. However, the 1980 Census counts were updated in

1982 and 1988 by the Dallas County Elections Office by

reconfiguring precincts according to the changes made in precinct

lines. Testimony of Dr. Richard Engstrom. Dr. Engstrom accepted

the updated census counts for 1982 and 1988 as reliable. Id. In

32

the intervening years of 1984 and 1986, Dr. Engstrom looked for

precincts that combined or split and aggravated precinct counts

for those precincts. Id. ' ••• ■ . .

b. Dr. Engstrom analyzed seven (7) general elections_for

State District Court where Blacks opposed Anglos between 1980 and.

1988 in Dallas County. The correlation coefficient or "rM values

exceed 0.864 (86%) for six ̂ 6) of the seven (7) elections analyzed.

See Appendix A, Plaintiffs' Exhibit D-02. Dr. Engstrom's

homogenous precinct analysis and regression analysis shows a strong

relationship between race and voting patterns in Dallas County.

Id., see columns 2 & 3. Dr. -Engstrom -testified that the-

significance -level was much smaller than the generally-accepted

level of extremely khigh significance of .05 and that the

probability bhat the Dallas County estimates would have occurred

by chance were less than 1 out of 10,000.

c; I- The lowest’K r L squared cbor - these analyses is

approximately .75 (75%). This figure is found from multiplying the

r value by itself for Jesse Oliver's judicial race in 1988. This

coefficient of determination demonstrates that race explains at

least 75% of the variance in voting in at least six (6) of the

seven (7) elections relied on by Plaintiffs and Plaintiff-

Intervenors. - — -

33

d. Plaintiffs' Exhibit D-02 further shows that in five (5)

of the seven (7) elections as the percentage of Blacks increased

in precincts, so did Black support for the preferred candidate of

Black voters;■>> See Homogeneous precinct analysis, column 2;-~ rrr~-

e . r■ Bivariate regression analysis reflects a negative

correlation for Carolyn Wright's.-, .judicial .race in .1986.. Judge

Wright is a Black who ran on the Republican ticket. She received

-1.5% of .r the Black vote <i.and 71-.7% gof ̂ the non-Black vote.

Plaintiffs' Exhibit D-02, columns 4< & 5. The correlation

coefficient was -0.872 (-87%). -Id^ column 3. This reflects

that, as the percentage of Blacks in voting precincts increases,

Judge Wright's support decreased::: in other words, even though Ms.

Wright is Black, she did„not receive the support of the Black

communityg Hence, she was not .the preferred candidate of JBlack

voters in Dallas County. Black voters also failed to support

Judge Baraka, a Black Republican candidate in 1984.

f. When Dr. Engstrom controlled for Hispanic votes, Dr.

Engstrom's regression analysis shows that Blacks consistently gave

more than.97% of their vote to their preferred candidate. Id., see

last two columns. Dr. Engstrom's analyses shows that Blacks are

politically cohesive in general elections for State District Court

in Dallas County. - • • ; : -

34

g. His analysis is confirmed'by the testimony of

Plaintiff-Intervenors' Joan Winn White, Fred Tinsely, H. Ron White

and Jesse Oliver. The Exhibits ^reflect that each Plaintiff-

Intervenor received 97% or better of the Black, homogenous precincts

and at least 83% of the votes in precincts with Black population

of 50% to 90%. "Plaintiffs Exhibit P-I D-16 - D-22a.

h. Plaintiffs calculated the percentage of votes for-the

Black preferred candidate, Jesse Oliver, and his white opponent'.

Brown, in each of the proposed hypothetical single member

districts. Plaintiffs' Exhibit D-12a. They .repeated this

procedure.-for^ the judicial races involving the Black preferred

candidates in Plaintiffs' Exhibit D-t)2 and Nathan Brin (an Anglo

preferred by Black voters in Dallas County). Plaintiffs' Exhibits

D-12b,i 12c & 12d. ■ In each , instance,an the Black t. community's

preferredl* candidate received a r majorityr of votes a in each

predominately Black hypothetical districts i, > :■

i. Defendant-Intervenor Judge Harold Entz ("Judge Entz"),

attacks Plaintiffs and Plaintiff-Intervenors evidence on the ground

that: (1) the data is based on total population and not voting age

registered voters; (2) the analysis does not reflect changes in the

distribution of population over time as a result of growth of

Dallas suburbs and geographic dispersal of minorities; (3) Dr.

35

Engstrom did not control for absentee or Oriental votes; (4) there

is a stronger association between partisan affiliation and success

then there is between race and success; and (5) the analysis shows

what happened, but not why it happened.“ In support of fiis fourth

attack, Judge Entz argues that five of the seven elections analyzed _

involved Black candidates who are the candidate of choice, while

all seven involved Democratic candidates who were the Black

preferred candidate of choice. Thus, Judge Entz concludes that

political party is a; better predictor of the Black preferred

candidate and that candidate is a victim of partisan politics not

discriminatory vote dilution.

'^ j . Dr. Engstrom testified-that: (1) he was never given-

precinct data by race and voting age registered voters; and (2) the

range of support for the Democrat.candidates between 1980 and 1986

varied 10 to 17 percentage points. Thus, Dr Engstrom concluded

that something other than just straight party voting is going on

in judicial elections. i'-. 1

k. Dr. Dan Wiser's testimony confirms Dr. Engstrom's

results. Dr. Wiser's data set was based on 1980 Census data,

Dallas County election returns and Dallas County precinct data

adjusted for changes in precincts. Precincts that split were

reconstructed by estimating the part of the precinct that shifted

36

to another and apportioning the registered vote based on the shift

and past history. Testimony of Dr. Dan Wiser. The adjusted data

was checked against the 1986 Justice Department submissions, id.

Plaintiffs' Exhibit P-I D-H. Ninety eight percent (98%) of the

vote in homogeneous precincts of 90% Black voters went to the Black

preferred candidate. Plaintiffs' Exhibit P-I D-ll, D-16 through

D-23a. At least 83% of the Black community vote supported the

Black preferred candidate in homogenous precincts of between 50%

and 90% Black. Id. ‘ ' t c

"1. Dr. Wiser calculates that the Asian community only

comprised approximately 2^6% of the total Dallas County population

as of 1985. Plaintiffs',Exhibit P-I D-03. He testified that the

best estimate of the growth of the Asian community between 1985 and

the present is supplied by the Bureau of Census. Plaintiffs'

Exhibit P-I D-02. He believes there has only been a growth of

approximately 3% between 1985 and 1988 and does not agree with

estimates of Asian leaders in Dallas County.

m.-.; Plaintiffs and Plaintiff-Intervenors established the

third Ginqles prong by showing that a white bloc vote exists. The

Y intercepts-calculated by Dr. Engstrom for the Black preferred

candidate ranged between 29 and 39 percent for the seven elections

analyzed. Plaintiffs' Exhibit D-02. The highest Y intercepts were

37

61.8% and 71.7% for Judges Baraka and Wright respectively, the non

preferred candidates. Id. The highest percentage of Anglo Cross

over votes received by the preferred candidate of Black voters was

approximately 39 percent. -1 Id.-,- 1980 race -involving Joan Winn

White. There are 197 precincts in Dallas County that are 90% or

greater white population. Plaintiffs' Exhibit P-I D-06 & 07.

n. This is corroborated by Dr. Engstrom's homogenous

precinct analysis and Dr. Wiser's analysis. r,.-Id. at-column 1. -

This analysis demonstrates that an Anglo bloc vote exists. The

Court finds on the basis of the exhibits and testimony of Dr.

Engstrom and Dr. Wiser that the Anglo or white bioc vote in Dallas

County is sufficiently strong to generally defeat the choice of the

Black community. ..

o. Dr. Anthony Champagne testified that judicial elections

in Dallas County were characterized by strong partisan affiliation

rather than racially polarized voting. Dr. Champagne analyzed

contested District Court general elections between 1976 and 1988.

Plaintiffs' Exhibit P—I D-06-A. Dr. Champagne bases his opinion

on the steady increase of Republican victories in Dallas County

over time. Plaintiffs' Exhibit P-I D-07-A pp.1-2. Only seven (7)

of the contested general elections analyzed involved Blacks

opposing white candidates. Plaintiffs' Exhibit P-I D-09-A p. 1.

38

No Black candidate running on the Democratic ticket won a general

election. Two Black candidates running as Republicans■won. Id.

at 1. - The Court" noted, supra. that it was the non-Black vote

that gave rise to the success of these two candidates . ■~ See Finding

of Fact 17. e. - • v ' • .rl., r. ..U

p. Dr. Taebel analyzed nine judicial elections -in which

Blacks opposed Anglos. In eight of the nine, Blacks and Anglos

voted differently. State Defendants Exhibit D-06 pp. 1, 13, 17;

21, 37, 69, 73, 81 & 89; See Appendix B, Plaintiffs' Re-Evaluation

of Dr. Taebel's Reports ("Re-Evaluation") for Dallas County p.l.

The Black... preferred candidate won only once. Id. This sole

victory arose in the 1988 Republican primary. Id. The Black

choice won only five (5) of the other twelve primary and general

District Court and Appellate ! 'Court races analyzed. : Id.';

Plaintiffs' Re-Evaluation p. 2. k* •:' ' r.

18. Tarrant County. r- rr ' • c'̂ --

-• a. • Dr. Robert Brischetto ("Dr. Brischetto”) testified

concerning on behalf of Plaintiffs and Plaintiff-Intervenors in

Tarrant County and the remaining counties at issue. He weighted

his analysis in all remaining counties. Dr. Brischetto used Black

population data by precinct from the 1980 Census for thirty four

39

(34) precincts in Tarrant County where precinct lines had not

changed. He analyzed four (4) elections in which Blacks opposed

Anglos in Tarrant County (three judicial elections and the 1988

Democratic Primary). See Appendix A, Plaintiffs' Exhibit Ta-02.

b. In Tarrant County and other Contested counties where

there was a large representation of three ethnic/racial groups, DrV

Brischetto used multiple regression analysis. Dr. "Brischetto

testified that this approach shows the effect of the percentage_of

Hispanics in precincts, for example, upon the votes received by a

minority candidate, when accounting for the effect of the

percentage of Hispanics. The statistical calculation that shows

the effect is called the "Partial r." :r- •

c. Dr. Brischetto calculated "Partial r" values of -87%,

-80% and ~90%~ respectively for the three judicial elections

analyzed. Plaintiffs' Exhibit Ta-02. "There was "a negative

correlation in the 1986 Salvant - Drago race and the 1986 Sturns -

Goldsmith race. Salvant and Sturns were Black candidates running

as Republicans. They did not receive the support of the Black

community. Id. Approximately 93% of the Black voters in precincts

analyzed voted for Drago, while approximately 85% of Black voters

voted for Goldsmith. Id. The likelihood that the estimates would

occur by chance (significance level) was much smaller than .05.

40

Testimony of Dr. Robert Brischetto. Dr. Brischetto's regression

analysis shows a strong relationship between race and voting

patterns in Tarrant County. The strength of the correlation is

dependent on the size of the number not on the positive or negative

value assigned to it. The negative correlation in the Salvant and

Sturns races merely reflects that as the percentage of Blacks in

voting precincts increases, the support for Salvant and Sturns

decreased.

d. The lowest r squared for these analyses is

approximately 64% for the 1986 race for Criminal District Court

Place 1. Race explains at least 64% of the variance in voting in

all elections relied on by Plaintiffs and Plaintiff-Intervenors in

Tarrant County.

e. Plaintiffs' Exhibit Ta-02 further analyzes the Jesse

Jackson Democratic Presidential Primary in 1988. The Partial r for

Jesse Jackson was 98%. Although the Jackson race was not a

judicial election, its analysis corroborates the judicial elections

analyzed. However, Dr. Brischetto testified that he would reach

the same conclusions without considering the Jackson contest.

f. Dr. Brischetto's homogenous precinct analysis

corroborates the results of his regression analysis. Plaintiffs'

Exhibit Ta-02. It shows that Black voters in Tarrant County gave

41

more than 89% of their votes to the preferred candidate of Black

voters in every election analyzed. ; c---- = • .-•

9* - -Dr* Brischetto also recompiled and reanalyzed Dr.

Taebel's work concerning Tarrant County. Plaintiffs' Exhibit Ta-

iO. Plaintiffs' Exhibit Ta-10 compiles all of Dr. Taebel's

analysis of countywide elections for judicial positions when Blacks

opposed Anglos. Dr. Taebel also found negative correlation of

-63% and -60% in the Salvant and Sturns elections respectively.

Id. While these correlation figures are not as high as those

found by Dr. Brischetto, they still reflect a strong correlation.

See Finding ;of Fact-16.b; last sentence-— 1 — - - ’ -

h * --D r * Taebel used bivariate regression in his analysis.

Dr. Brischetto is of the opinion that had Dr. Taebel used

multivariate: analysisv'. his correlation estimates would1 have' been

more precise,,. Further Dr. Brischetto believes that the r values

wouid bave been higher, because the analysis -would have eliminated '

the effect of Hispanics. while Dr. Brischetto did not agree with

Dr. Taebel's statistical methodology, he reviewed Dr. Taebel's work

because Dr. Taebel's data set was more complete. r-,.

i._ This Court finds, on the basis of all' of Dr.

Brischetto's analysis, the Black community in Tarrant County votes

cohesively in general elections for State District Court Judges.

42

j. The Court further finds that the Anglo bloc vote in

Tarrant County is sufficiently strong to defeat the minority

community's preferred candidate. In the three general elections

analyzed, the preferred candidate of Black voters lost every time.

This is true even though each of the Black preferred candidates

had a sizeable percent of Anglo cross over votes. Plaintiffs'

Exhibits' Ta-02; Ta-10. The Y intercept~ reflects that Anglo

support for-the Black preferred candidates was between 42% and 49%.

Id. Ta-02.^ec. ,, .. . ; U; ; .... • . ... •>.

_k. The testimony of Plaintiff and sitting District Judge

Maryellen Jiicks corroborates: this analysis. ' Judge Hicks is Black.

She testified that the only time she ran against an Anglo in a

countywide judicial election she lost. Plaintiffs' Exhibit Ta-10,-

County Criminal Court Place 1.- She feels that she lost because she -

could not convince Anglos to vote for her. She also believes that

she could«not win if she had Anglo opposition because of the Anglo

vote. - rv ; ■ : . ,,r,. . .;m,, ... .

1. -.Judge Hicks testified that implementation ; of single

member districts in Tarrant County Jiad .immediate effects. .Before

the districts went into effect, only two Blacks had been elected

to School Trustee positions. Since single member districts were

implemented, two Blacks and one Hispanic have consistently been

't j f r on

43

Trustees. Two Blacks and one Hispanic also took office on the Fort

Worth City Council as a result of single member districts being

implemented for that body. Further, after single member districts

were established for State Representative offices, two minorities

were elected to the Texas House of Representatives.25. - r. .

m.' In the five primary and general judicial elections-

involving Black candidates analyzed by Dr.~Taebel, the Black choice

won only once. State Defendants Exhibit D-39 pp. 1, 29, 33, 37 &

57; See Appendix B, Re-Evaluation for Tarrant County p.l* It is

clear that Blacks and Anglos voted differently in these races, id.

In District Court general- elections that did notr have a Black

candidate, the oandidate preferred by Black voters won three (3)

of five (5) times. Id. D-39 pp. 13, 17, 21, 25 & 61; Re-Evaluation

at 1-2': ~-In-.three other ̂ judicial -general elections the-candidate

of choice of the Black community won all three times. Id. D-39 pp.

9, 49 &-65? -Re-Evaluation at 2. Two of the three were Appellate

Court elections, while the third involved the County Court at Law.

Id. The candidate of choice also won all three primary judicial

elections analyzed by Dr. Taebel. Id. D-39 pp. 5, 41 & 49.' --:

After the lines were redrawn in 1982, one minority has been

elected; rr "-

44

19. Bexar County.

-a. Dr. Brischetto based his analysis of Bexar County on

Spanish surnamed registered voter data by precinct from the office

of the Secretary of State of Texas. Dr. Brischetto testified that

this data was the closest measure of actual registration data by

precinct. Dr. Brischetto used bivariate regression analysis in

Bexar County because of the very small Black population in^the

County r .-i--- ------ - • - •_

- b. He analyzed six (6) general elections from 1980 to 1988

in which Hispanics opposed Anglos. See Appendix A, Plaintiffs'

Exhibit- B-02. He calculated "rJ1 values for Hispanic preferred

candidates between 86% and 88%.v Id. f His regression analysis shows

a strong relationship between race and voting patterns in Bexar

County. In all but one race, ras the percentage :of'Hispanics

increased?'support for the Hispanic preferred candidate increased.

Dr. Brischetto testified that the probability that 'correlation of

this size would happen by .chance was much smaller '-than the

generally accepted level of .05.26 • c ' • h : . - j:

c. In the 1982 Barrera - Stohlhandski race, the Hispanic

The significance level for each election is .0000.

Plaintiffs' Exhibit B-02. Dr. Brischetto testified that there was

practically no [or zero] probability that these correlations would happen by chance.

45

candidate, Roy Barrera, Jr. running as a Republican, received very

little Hispanic support. The correlation coefficient for Mr.

Barrera was -80%. Id. As the percentage of Hispanics in voting

precincts increased, Barrera's support decreased. Barrera received

approximately 17% of. the Hispanic vote. Id. He was not the

preferred candidate of Hispanic voters in Bexar. County. o :l ..

•::i■ d.;..... The lowest r : squared for - these r analyses is

approximately 64% for Mr. Stohlhandski, an Anglo running as a

Democrat in the 1982 Barrera - Stohlhandski race. The highest r

squared was 77% for the 1986 Cisneros - Peeples race. This

demonstrates inBexar County that race explains at least 64% to 77%

of the variance in voting in all six elections.

e. Dr. Brischetto's background and homogeneous precinct

analysis confirm the fact that iHispanics are politically cohesive

in Bexar County. Dr. Brischetto lives in Bexar County and analyzed

election behavior there in a Section 2 case involving the San

Antonio River Authority.-., Plaintiffs' Exhibit B-16v- There he

found polarized voting along racial and ethnic lines in a

nonpartisan election involving low profile campaigns. Dr.

Brischetto's homogeneous precinct analysis shows that Hispanic

voters in Bexar County gave 73% to 93% of their votes to the

preferred candidate of Hispanic voters in every election.

46

f. Dr. Brischetto controlled for absentee votes in 1988

elections based on allocated data from the Bexar County Elections

Administrator. He testified that the additional data did not • •

change his conclusions. .....

• g. Plaintiffs presented evidence from four hypothetical

districts carved out of existing precincts for each of the six

elections analyzed.- Plaintiffs' Exhibits B-12a - 12e. Almost ~'

always, the Hispanic candidate who actually lost at-large would

have won if he had run from a hypothetical majority Hispanic y ̂ a .,

district. _.__In one case, the 1988 Republican primary between^

Arellano and White, the Hispanic^-candidate won in cnly three of the.-.wr, = ,

four hypothetical districts.~ Id. B-12e. . ■ • v--- — , — *na

h. In the 1988 Arellano — White Republican primary for the I

150th District Courts Arellano * ran...as jianii appointed Incumbent. <- ross

White,.an Anglo, decided late in the campaign that he did not want

to run for office. .. It was too -late to withdraw, but he endorsedro get.

his opponent Arellano. White nevertheless -won. Adam Serrata Judae

testified in his deposition that this was a classic example of r.-iw.:

polarized voting. Deposition Summary of Adam Serrata ("Serrata

Depo. ") . . hss

i. Other testimony suggests the same conclusion. J u d g e ..

Anthony Ferro testified in his deposition that he -ran for County ’.‘.n-rr.

47

Court at Law four times in Bexar County. He won two races were he

did not have Anglo opposition. Deposition Summary of Anthony Ferro

("Ferro Depot") at 1. Both Messrs. Serrata and Ferro testified

that it is not possible to get elected in Bexar ^County to the

position of District-Judge without Anglo support. Id.; Serrata v

Depo. — . - • -u: --.

- j .- Dr/ Brischetto further concluded that the-Anglo bloc ,

vote in Bexar County is sufficiently strong to defeat^the Hispanic -

community's preferred candidate. In the six elections analyzed, th

the preferred candidate of Hispanic voters won only once. See 1988

Mireles - Bowles race. The Y intercept reflects that non-Hispanic

support for the Hispanic preferred candidates was between 18% and

35%. It is' not surprising that the one Hispanic candidate of

choice who won also received_the highest percent of Anglo cross

over votes. -r‘ >.1-,

k. Judge Ferro testified that he has only been able to get w

elected when he did not have an Anglo opponent. Ferro Depo. Judge

Paul Canales testified that voters in Bexar County pay attention

to the race/ethnicity of candidates in-judicial elections. -

l. The effect of fairly drawn single member districts has

had a positive effect on minority election results in Bexar County.

Immediately after the creation of single member districts in White - -

48

v. Reoester. Hispanics were elected to the Texas House of

Representatives. further, immediately after the City Council

implemented single member districts, the number of minorities on

the San Antonio City Council increased. Serrata Depo.; Ferro Depo.

• m. Whites and Hispanics voted differently in 28 of the 29 njn e t

judicial elections involving Hispanic candidates in Bexar County. -,_j

State Defendants Exhibit D-07 pp.. 2-5U.-18; See Appendix B , Re- -

Evaluation for Bexar County p.1-2. In the twelve general elections

analyzed by Dr. Taebel, the Hispanic preferred candidate won three .sLr-r

(3) times. Id. D-07 pp. 4, ’5, 7, 15-16, 18-21 & 25-28; Re-

Evaluation at 1. Only one of those was a District Court election.

Id. D-07 at 5. The Hispanic choice won six (6) out of 18 primary cv ~ .

elections. Id. Re-Evaluation a.t 1-2. ̂ -- ■ r

' J ' v— — '■ ^ • • ■ • j . « . j • - - i v 4

‘•■20 .anTravis County. ' r ? • -nv/ed.

Sc.a.r.ppDr. Brischetto analyzed othree (3) 1988 countywide rved

judicial elections in Travis County: one primary election for the one

345th District Court and two County Court, at Law general elections. t.;-

Dr. Brischetto testified that there has only been one Hispanic -

Anglo District Court election between 1978 and 1988. . In that race,

the Anglo won. Plaintiffs' Exhibit Tr-11; Testimony of Jim

Coronado. Mr. David Richards testified that the Republican party nonov

! ■ i ; ; : n t | - v i'i i i i •

49

is insignificant in Travis County. Hence, Mr. Richards concluded

that the Democratic Primary is the true testing ground for opposed

candidates in judicial elections.

b. Dr. Brischetto used Hispanic population data by

precinct from the 1980 Census reconfigured +to 1988 'precinct

boundaries. He based his polarization and homogenous precinct

analysis ton total population figures for Blacks, Hispanics and

Anglos in approximately 178 precincts ̂ (virtually ali^of t-them) in

the County. Amalia Rodriguez Mendoza^ the Travis County Registrar

of Voters, provided the data.

— c » Dr. Brischetto 's~multivariate or multiple regression

analysis shows that the Hispanic community in Travis County is

politically cohesive, when the effect of the Black vote is

considered. Dr. Brischetto calculated "Partial r" valges~of -84%,

85% and 90% respectively for the three judicial elections analyzed.

See Appendix A, Plaintiffs' Exhibit Tr-02. The Hispanic preferred

candidate received at least 77% of the Hispanic vote ‘ in one

election27 , 93% in the Democratic Primary election and 95% in the

Garcia - Phillips race. Id. The likelihood that the estimates

would occur by chance (significance level) was much smaller than

rThe 1988 County Court at Law race between Castro Kennedy

and Hughes. Castro is the Hispanic preferred candidate.

Plaintiffs' Exhibit Tr-02.

50

.05. Testimony of Dr. Robert Brischetto. Dr, Brischetto's

regression analysis shows a strong relationship between race and

voting patterns in Travis County. : ~- • y

d. The homogenous precinct analysis for Travis County

establishes 4a similar pattern. Plaintiffs' Exhibit Ta-02. It?

shows ■that Hispanic voters gave more than 63% arid as high as 90%

of their votes to the Hispanic preferred candidate.

e. Dr. Brischetto also reanalyzed the same three elections

using bivariate regression analysis based upon voter registration

data. See Appendix J A, -Plaintiffs' Exhibit ~'Tr-19. These

correlation figures are very close to those -calculated using

multivariate analysis, and clearly reflect strong correlation;- See

Finding of Fact 16.b. last sentence. With either data set," Dr.

Brischetto's analysis shows that as the percentage of Hispanics in

precincts increase, so does support for the Hispanic, preferred

candidate. The r squared figures all exceed approximately 64%.- -

1 f. The Hispanic preferred candidates took the majority of

the votes from Plaintiffs' hypothetical districts even though they

lost countywide. Plaintiffs' Exhibit-Tr-12.

g. The State Defendants were concerned that Plaintiff's

did not analyze Statewide judicial or legislative elections. See

Cross examination of Jim Coronado; Cross examination of Dr.

51

Brischetto. Dr. Brischetto testified that Plaintiffs focused on

local elections when that data was available and these elections

were not reached in Plaintiffs' hierarchy of priority. He further

testified that the elections analyzed were the closest in nature