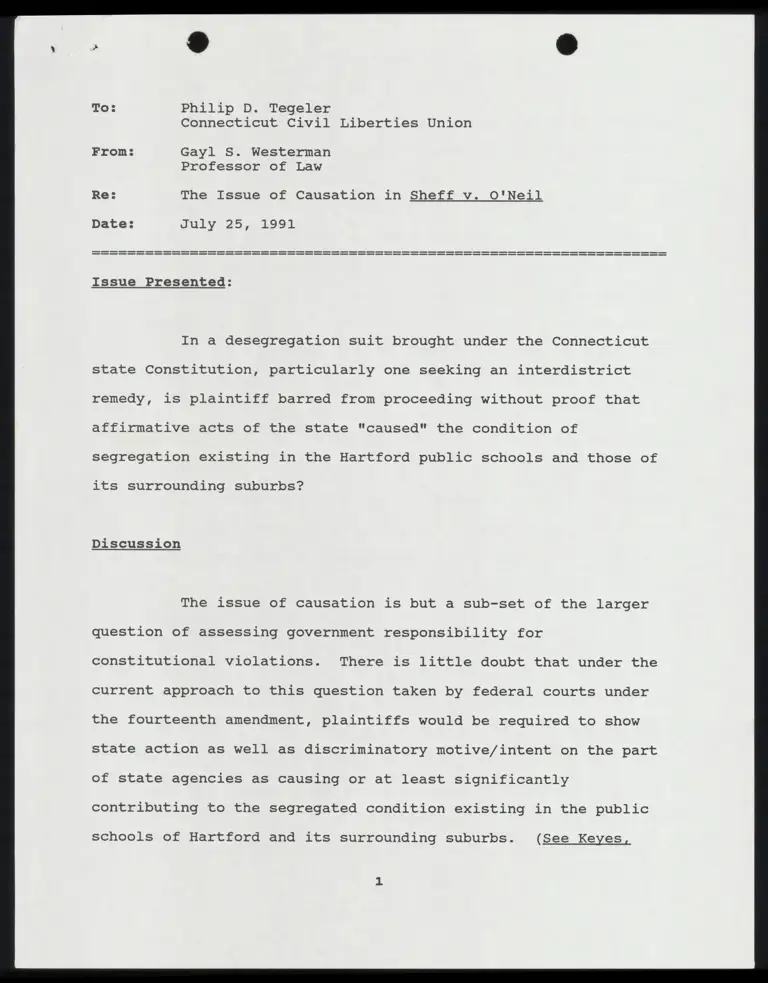

Correspondence from Tegeler to Westerman Re: The Issue of Causation in Sheff v. O'Neill

Working File

July 25, 1991

60 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Correspondence from Tegeler to Westerman Re: The Issue of Causation in Sheff v. O'Neill, 1991. 958afb2e-a446-f011-877a-0022482c18b0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/848a7d61-d9e3-4ce2-a680-b9071fe59afe/correspondence-from-tegeler-to-westerman-re-the-issue-of-causation-in-sheff-v-oneill. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

Philip D. Tegeler

Connecticut Civil Liberties Union

Gayl S. Westerman

Professor of Law

The Issue of Causation in Sheff v. O'Neil

July: 25, 1991

Issue Presented:

In a desegregation suit brought under the Connecticut

state Constitution, particularly one seeking an interdistrict

remedy, is plaintiff barred from proceeding without proof that

affirmative acts of the state "caused" the condition of

segregation existing in the Hartford public schools and those of

its surrounding suburbs?

Discussion

The issue of causation is but a sub-set of the larger

question of assessing government responsibility for

constitutional violations. There is little doubt that under the

current approach to this question taken by federal courts under

the fourteenth amendment, plaintiffs would be required to show

state action as well as discriminatory motive/intent on the part

of state agencies as causing or at least significantly

contributing to the segregated condition existing in the public

schools of Hartford and its surrounding suburbs. (See Keyes,

Milliken, Washington v. Davis and progeny).

It is hardly surprising that all cases cited by the

defendants to support their assertion that plaintiffs are barred

in their claim without proof of causation are federal cases

decided by the U. S. Supreme Court under the equal protection

clause of the fourteenth amendment. No support can be found for

this assertion, however, under Connecticut law. Instead,

defendants rely on federal law combined with a aunber of now

discredited precedents in Connecticut case law which appear to

support the notion that federal and state equal protection

provisions have "like meaning and impose similar limitations."

Defendants must surely realize that the notion that states courts

are bound to apply federal constitutional interpretation

standards has been repeatedly rejected by Connecticut courts,

particularly since the U. S. Supreme Court adopted a

discriminatory intent/causation standard to equal protection

cases in the mid-seventies. Two cases in particular, Fasulo Vv.

Arafeh, 173 Conn. 473 (1977) and Horton v. Meskill, 172 Conn. 615

(1977) (Horton I), have recognized the "primary independent

vitality of the provisions of our own constitution," Horton I,

172 Conn. at 641, and have clearly indicated that state and

federal provisions do not have to be read with like meaning and

limitations. Although Connecticut courts have sometimes inserted

the old "like meaning" language into current cases, the term now

stands for the proposition that the Connecticut Constitution

"shares but is not limited by the content of its federal

counterpart." - Fasulo v. Arafeh, 173 Conn. 473, 475 (1977). As

to the issue of causation itself, the lesson of Fasulo also seems

clear: when the state impinges on a fundamental right in any

manner, whether or not the circumstances which cause the

infringement are of the state's own creation, the state bears the

burden of justifying the intrusion. Although a due process case,

Fasulo illustrates the willingness of Connecticut courts to

depart from federal jurisprudence in effectuating state

constitutional rights.

Connecticut courts have consistently expanded protection of

civil rights under Connecticut constitutional provisions beyond

that offered by their federal counterparts, most notably in

Horton v. Meskill, 172 Conn. 473 (1977) (rejecting the approach

taken by the U. S. Supreme Court in Rodriquez and finding a

fundamental right to education violated by state school finance

laws); in Doe v. Maher, 40 Conn. Supp. 394 (1986) (rejecting the

approach taken by the U. S. Supreme Court in Harris v. McRae and

striking down regulation restricting right to medicaid payment

for abortions under the state due process clause); in State v.

Kimbro, 496 A.2d 498 (Conn. 1985) (rejecting the federal "Gates

rule" on probable cause justifying search and seizure); in State

v. Davis, 506 A.2d (Conn. 1986) (setting forth an independent

Connecticut rule on the ultimate right to call a witness under

Article first, § 8); in Griswold Thin, Inc. v. State, 441 A.24 16

(Conn. 1981) (expanding state protection of religious freedom) ;

in State v. Saidel, 159 Conn. 96 (1970) and State v. Licari, 153

Conn. 127 (1965) (enlarging protections against unreasonable

searches and seizures); and others. In State v. Dukes, 547 A.2d

10, 18 (Conn. 1988), the Connecticut Supreme Court, citing State

Vv. Stoddard, State v. Jarzbek, State v. Scully, State v. Couture

(cites omitted) and others in addition to Horton I and Fasulo,

reaffirmed that although Connecticut courts are free to follow

the lead of the federal courts at their discretion, "this court

has never considered itself bound to adopt the federal

interpretation in interpreting the Connecticut Constitution . . .

. [i]t is this court's duty to interpret and enforce our

constitution . . . . Thus, in a proper case, 'the law of the

land' may not, in state constitutional context, also be 'the law

of the state of Connecticut.'" State v. Dukes, 547 A.2d4 10, 19

(Conn. 1988).

This trend in constitutional adjudication in Connecticut is

part of a larger trend nationwide which finds many state supreme

courts interpreting their state constitutions to afford more

expansive protection to their citizens than is afforded under the

federal constitution. See, e.9., Reeves v. State, 599 P.2d 727

(Alaska 1979); State v. Sporleder, 666 P.2d 135 (Colo. 1983);

Bierkamp v. Rogers, 293 N.W.2d 577 (Iowa 1980); People Vv.

Hoshowski, 108 Mich. App. 321, 310 N.W.2d 228 (1981); People Vv.

Williams, 93 Misc.2d 93, 402 N.Y.S.2d 289 (1978); State Vv.

Flores, 280 or 273, 570 P.2d 965 (1977); People v. Neville, 346

N.W.2d 425 (S.D. 1984); Miller v. State, 584 S.W.2d 758 (Tenn.

1979); State v. Ringer, 100 Wash. 2d 686, 674 P.2d 1240 (1983);

§:1 . »

Helena Elementary School Dist. v. State, 769 P.2d 684 (Mont.

1989); Stout v. Grand Prairie Ind. School Dist., 733 S.W.2d 290

(Tex. Ct. App. 1987); Edgewood Indep. School Dist. v. Kirby, 777

S.W.2d 391 (Tex. 1989); Jenkins v. Township of Morris School

Dist., 279 A.24 619 (N.J. 1971); Booker v. Bd. of Educ.

Plainsfied, 45 N.J. 161 (1965); and others. This trend is well-

documented in the literature. See Developments in the Law--The

Interpretation of State Constitutional Rights, 95 Harv. L. Rev.

1324 (1982); Brennan, State Constitutions and the Protection of

Individual Rights, 90 Harv. L. Rev. 489 (1977).

As undeniable as this trend may be, I believe that due to

the strong rejection of an interdistrict remedy by the U. S.

Supreme Court in Milliken, which relies in turn on the

discriminatory intent/causation requirement for equal protection

cases announced in Keyes, Washington v. Davis, and progeny, the

defendant's argument that plaintiff's claim is barred without

proof of state action which caused the segregated condition to

exist and, further, that such a causal connection can only be

established by showing defendant's discriminatory intent or

expectation of harm, see Memorandum in Support of Defendant's

Motion to Strike, at 33, may be more difficult to oppose than

might be hoped. State courts, Connecticut included, still pay

lip service, at least, to the notion that U. S. Supreme Court

opinions are "persuasive authority" for state constitutional

interpretations, and the issue of interdistrict remedies in

desegregation cases has been a topic of heated debate between and

among constitutional scholars since the decision in Milliken I

was announced in 1973. (For an exhaustive review of most of

these divergent views, see Liebman, Desegregating Politics:

'All-Out' School Desegregation Explained, 90 Colum. L. Rev. 1463-

1664 (1990)). Both sides in the current conflict over the

Hartford area schools will be able to find ample support for

their arguments in re: intent/causation in this literature.

If the Court decides to follow the federal approach in

assessing government responsibility and requires a showing of

state action/intent/causation, I believe you are well prepared in

this regard and may prevail even in obtaining an interdistrict

remedy. A few lower federal courts have ordered such remedies

since 1973 and the U. S. Supreme Court did so in Columbus Board

of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449 (1979) and Dayton Board of

Education v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526 (1979) by, arguably,

broadening the Keyes standard somewhat and taking note of

precisely the kind of evidence which you propose to introduce.

Nevertheless, I agree that by far the best result would be

Connecticut's adopting its own approach under state law

unburdened by these threshold tests.

The majority opinions of the Connecticut courts in Horton,

Fasulo and_Maher, as well as the forceful dissent by Justice

Peters in Cologne v. Westfarms Associates, 469 A.2d 1201, 1211

(Conn. 1984) (arguing that there is no textual basis for a state

action requirement under the state constitution, but "if we are

to import [one] into the Connecticut Constitution, we must

‘t » &

recognize that its contours will necessarily differ from the

state action concept that has developed under the Constitution of

the United States," id. at 1218, give me a basis for guarded

optimism that the court will be amenable to an approach to

desegregation under the Connecticut Constitution that differs

markedly from that taken by the U. S. Supreme Court in Milliken -

- i.e., that "Sheff is to Milliken as Horton is to Rodriquez".

In my opinion, an excellent basis for a distinctive Connecticut

approach to desegregation has already been created by the

Connecticut Supreme Court in Horton I. In that case, the court,

while retaining the "tiers of scrutiny" aspect of federal equal

protection jurisprudence (later changed somewhat under Horton

IIT), nevertheless declined to adopt a discriminatory intent

and/or causation threshold test. At most, the court appears to

have adopted an "effects" test which was satisfied in that case

by a showing that a specific condition, i.e., inequity in school

financing, which has "resulted" from delegating legislation may

constitute a violation by the state of both the equal protection

clauses of the Connecticut Constitution as well as the

affirmative duty to provide for equal educational opportunity by

"rappropriate’' legislation." Horton I, 172 Conn. at 649. It

seems a very short step from this language to the approach which

you have adopted in Sheff, i.e., that, once again, delegating

legislation by the state has "resulted" in school district

boundaries which have made racially balanced schools, mandated by

state law as essential to equal educational opportunity, an

impossibility in metropolitan areas such as Hartford and its

surrounding towns. The question is, how to encourage the court

to take this step?

There are several avenues of argumentation which might prove

helpful in lending support to your argument that a "causation"

requirement in any of its various forms does not, and, further,

should not exist under Connecticut constitutional jurisprudence.

I have set forth some of these avenues for you in the following

memorandum which, in outline form, makes these points:

l. Connecticut courts should not adopt the federal

standard in school desegregation cases because:

The current federal approach to assessment of

government responsibility in school desegregation

cases is not mandated by the U. S. Constitution or

prior federal case law; is based on flawed legal

theory; and is incapable of providing a

satisfactory remedy to metropolitan-wide

segregation.

The federal approach is based on federalist and

other institutional concerns which do not limit

the power of Connecticut courts to resolve issues

under the Connecticut Constitution. These and

other differences in the two systems of

y ! %

adjudication militate in favor of an independent

Connecticut approach which does not reflect the

federal model.

2. Connecticut courts should develop an independent

approach to school desegregation cases under the

Connecticut state Constitution because:

a. A clear understanding of the problems to be

remedied demands an effects-based jurisprudence

focused on segregative condition. Such an

approach is fully supported by the express

language of the Connecticut Constitution and

Connecticut case law.

b. A per se approach to segregative condition under

the Connecticut Constitution is supported by

empirical research studies which unequivocally

affirm the value of racially balanced schools to

minority and white students alike, to their

parents, and to the society at large. Deprivation

of an opportunity to attend such schools in

metropolitan areas such as Hartford and its

surrounding suburbs is a per se denial of the

fundamental right to equal educational

opportunity, mandated by Horton I.

1. Connecticut courts should not adopt the federal

standard in school desegregation cases because:

The current federal approach to assessment of

government responsibility in school desegregation

cases is not mandated by the U. S. Constitution or

prior federal case law; is based on a flawed legal

theory; and is incapable of providing a

satisfactory remedv to metropolitan-wide

segregation.

Two important cases decided by the U. S. Supreme Court in

the early seventies seemed to point the way toward an enlightened

school desegregation doctrine in which courts moved away from

condemning only those cases of segregation where assignments were

made on the basis of race to a result-oriented approach that

focused on the segregated patterns themselves. Fiss, The

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Case - Its Significance for Northern School

Desegregation, 38 U. Chi. L. Rev. 697 (1971). In Green v. New

Kent County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968), the U. S. Supreme

Court invalidated a presumedly race-neutral student assignment

plan based on "freedom-of-choice", where the result of the plan

was continued racial segregation. The Court expanded on this

approach in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971), by declaring "geographic proximity" an

10

impermissible basis for student assignment, again, because the

plan did not "work" in diminishing the segregated condition of

the schools, and by ordering an interdistrict remedy in which the

greatest degree of actual desegregation must be achieved.

Many commentators at the time would have agreed with Fiss

that "the net effect of Charlotte-Mecklenburqg is to move school

desegregation doctrine further along the continuum toward a

result oriented approach . . . [in] retrospect, Charlotte-

Mecklenburg will then be viewed, like Green, as a way station to

the adoption of a general approach to school desegregation which,

by focusing on the segregated patterns themselves, is more

responsive to the school desegregation of the North." Fiss,

supra at 704-705.

Two factors, one internal and the other external, conspired

against the continuation of this trend. The Swann case itself,

though result-oriented in part and enormously productive in terms

of remedy (Charlotte-Mecklenburg is now widely seen as one of the

most successful of court-ordered desegregation plans), carried

within it the seeds of a doctrinal trend which veered away from a

focus on segregated condition alone and toward a focus on past

discriminatory practices as forming a causal link to segregated

conditions in the present. Fiss himself noted the danger in this

element of the Court's approach but discounted it for two

reasons: first, he believed that the predominant concern of the

Court was the segregated pattern of school attendance, otherwise

such an "all-out" remedy could not be defended. Second, the

Court's theory of causation itself seemed contrived. Although

discriminatory practices had undeniably played a role in the

past, the Court did not attempt to determine the degree to which

such practices had contributed to the present condition. In

Fiss' words, the Court had merely used past

discrimination/causation as a "trigger . . . for a cannon", i.e.,

the all-out desegregation remedy, as well as a way to preserve

continuity with Brown and add a moral foundation for the

decision. Id. at 705.

Fiss predicted that the result-oriented language of Swann

would outlive the past discrimination/causal link requirement,

largely because the Supreme Court would be unable to treat

segregated conditions in northern and southern schools

differently:

A complicated analysis of causation might . . . serve

to justify the differential treatment afforded these

otherwise identical patterns. But such an analysis is

not likely to be understood or believed by most people.

And no National institutions can afford to be

unresponsive to the popular pressures likely to be

engendered by an appearance of differential treatment

of certain regions of the county.

Fiss, supra pg. 10, at 705.

These confident predictions of a trend toward a result-

oriented jurisprudence in school desegregation cases seemed well-

founded immediately following Swann. Lower federal courts, while

paying heed to the discriminatory intent/causal link elements of

the Court's decision, found these requirements to be easily

satisfied in a variety of creative ways, such as holding the

government responsible for the reasonably foreseeable and

2

»

' %

avoidable results of its actions or for its failure to act when

under a duty to do so, even if no actual causal link to

discriminatory animus could be proved. Courts often adopted the

burden shifting approach taken in Swann to force the state, once

a segregated condition had been shown to exist by plaintiff, to

prove that its actions had not caused that condition to be

created or maintained.

This jurisprudential trend might have continued had not an

external factor intervened in the form of process-oriented

constitutional theorists (Ely, Brest, and others) who maintained

that in a democratic society, essentially nondemocratic

institutions such as courts should avoid reviewing the substance

or the fairness of governmental decisionmaking and should

intervene only if the process of the decision making had become

adulterated in some way. See Ortiz, The Myth of Intent in Equal

Protection Cases, 41 Stan. L. Rev. 1105, 1105 (1989). In equal

protection terms, this adulteration was seen as resulting from

forbidden discriminatory motivations. Id. at 1106. The rapid

ascendancy of process-based theories in the scholarly literature

coincided with the beginning of a period of retrenchment in the

Supreme Court which occurred precisely at the time the Court

decided the first "northern" school desegregation case in 1973.

In Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 411 U.S. 189

(1973), the Court held that the desegregation remedies approved

in Swann were equally applicable to northern school districts

which had never been segregated by law, but only where local

a3.

officials had pursued deliberately segregative policies. Keyes

was followed by Milliken v. Bradley (Milliken I), 418 U.S. 717

(1974), in which the Supreme Court rejected a metropolitan-wide

remedy for Detroit, holding that "it must be shown that racially

discriminatory acts of the state or local school districts, or of

a single school district, have been a substantial cause of

interdistrict segregation." Id. at 744-45. This rejection left

uncorrected the dual school system and the vestiges of school

segregation which the district court had found to exist in

Detroit, vestiges which the Supreme Court had ordered removed

"root and branch" throughout South.

The final pieces of the current Court's equal protection

doctrine were put into place with three cases which left no doubt

as to the emerging doctrinal trend: Washington v. Davis, 426

U.S. 229 (1976), which held that in the absence of a racially

discriminatory motive or purpose, a facially neutral governmental

action, such as the use of screening tests in hiring, which has

an adverse racial impact will not be subject to strict scrutiny;

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development

Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977), which held that race must be shown to

be a motivating factor in the refusal to rezone land for low-

income housing and disproportionate impact alone would not

satisfy the intent standard; and Personnel Administrator v.

Feeney, 442 U.S. 256 (1979), in which the Court refused to import

into equal protection jurisprudence the familiar doctrine that a

person intends the natural and foreseeable consequences of her

14

voluntary actions, a doctrine which had been used productively by

lower federal courts in satisfying the intent/causation

requirement in school desegregation cases.

These decisions have not been totally fatal to school

desegregation. The Court has ordered desegregation plans

implemented in both Dayton, Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman

(Dayton II), 443 U.S. 526 (1979) and Columbus, Columbus Board of

Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449 (1979), on grounds which, it

could be argued, relaxed the Keyes discriminatory

intent/causation standard to some degree while retaining it

doctrinally. Nevertheless, all commentators, whether in favor of

an intent/causation requirement or adamantly opposed, agree that

such a standard has made it very difficult for plaintiffs to

prevail in school desegregation cases, and almost impossible to

prevail in those involving metropolitan-wide segregation of the

type currently existing in Hartford and its surrounding suburbs.

Many commentators have criticized the Supreme Court's use of

a discriminatory intent/causation requirement in school

desegregation cases which, in addition to other rationales often

used to limit the reach of judicial remedies, such as the de jure

- de facto distinction, federalism concerns, and respect for

school district lines and local control, has become a formidable

obstacle to the invalidation of public policies alleged to

violate the fourteenth amendment. See Goodman, De facto School

Segregation: A Constitutional and Empirical Analysis, 60 Cal. L.

Rev. 275 (1972); Fiss, The Fate of an Idea Whose Time Has Come:

15

Antidiscrimination Law in the Second Decade after Brown v. Board

of Education, 41 U. Chi. L. Rev. 742 (1974); Binion, Intent and

Equal Protection: A Reconsideration, Sup. Ct. Rev. 397 (1983);

L. H. Tribe, American Constitutional law (2d Ed.) (1988); Tribe,

The Puzzling Persistence of Process-Based Constitutional

Theories, 89 Yale L.J. 1063 (1980); Tribe, The Curvature of

Constitutional Space: What Lawvers Can Learn From Modern

Physics," 103 Harv. L. Rev. 1 (1989); Stein, Attacking School

Desegregation Root and Branch, 99 Yale L.J. 1983 (1990); See also

Ortiz and Liebman, supra. Most if not all of these legal

scholars would agree that such a standard is in no way implied or

required by the general language of the equal protection clause

of the fourteenth amendment. Nor was it required under prior

federal case law which in general held intent to be irrelevant in

equal protection cases. See, e.qg., Palmer v. Thompson, 403 U.S.

217, 224 (1971) ("[N]o case in this court has held that a

legislative act may violate equal protection solely because of

the motivations of the men who voted for it"). Other

explanations must therefore be provided for such a radical change

of course.

Ortiz' theory is that several factors combined to produce

the Court's approach to equal protection under the fourteen

amendment. By the early seventies, the Court had so thoroughly

fleshed-out its "tiers of scrutiny" jurisprudence that results in

equal protection cases had become predictable. Once the groups

deserving of strict scrutiny had been put in place, the key

16

question became identifying the group targeted by the

governmental decision. This was a fairly simple task as long as

laws discriminated on their face against protected groups. When

government officials began to use "proxy" classifications, i.e.,

classifications such as wealth and education which appear

facially neutral but which correlate with race and other

protected classifications, the Court needed an intent requirement

to uncover these covert, proxy classifications in order to know

how to proceed with their tiers of scrutiny analysis. Ortiz,

supra p. 13, at 1117-1119. This development coincided with the

ascendancy of process-based theories in constitutional law,

discussed supra, which required a show of intentional

discrimination in the decisionmaking process in order to justify

court intervention.

As necessary or as laudable as such a doctrinal development

may have been, Ortiz argues that it has not served its purpose

and is in fact applied differently depending on the type of case

being adjudicated. In equal protection cases involving housing

and employment, a plaintiff prevails only with absolute proof of

discriminatory motive, an approach which protects the cohort

classifications of wealth and education by which such benefits

are traditionally allocated. In cases involving voting and jury

selection, benefits not traditionally allocated by wealth and

education, discriminatory intent can be considered the "cause" of

an adverse impact by showing the impact on an identifiable group

combined with either the susceptibility of the selection process

17

to manipulation (jury selection cases) or discrimination in other

areas of life (voting cases). Id. at 1135.

It is in the school desegregation cases that the

intent/causation requirement has been most bizarrely applied. At

the initial phase of litigation, plaintiffs must still show

evidence of discriminatory motivation at some time from Brown I

on. Once that has been accomplished by plaintiffs, which is

increasingly hard to do as motivations become more and more

attenuated and causal links to current segregated conditions

become all but impossible to discern, the state can rebut such

evidence only with a compelling justification for segregation,

which no state has ever done. Should a plaintiff prevail in

establishing liability, the state is under an affirmative duty to

achieve a unitary system, and its efforts in this regard are

judged solely on the basis of effect. Once unitariness has been

achieved and the district court has relinquished its jurisdiction

over the case, however, should resegregation occur, plaintiffs

must now carry the burden of showing actual discriminatory

motivation in the current decisionmaking process much as

plaintiffs are required to do in housing and employment cases

discussed above. Id. at 1135-1140. Needless to say, this

approach has not only made the problem of metropolitan-wide

segregation very difficult to remedy but has also made it

virtually impossible to attack de facto resegregation in areas

where the original problem had once been alleviated.

There are other problems inherent in such an approach, not

18

the least of which is its failure to properly take note of the

effect of unconscious racism in the decision-making process.

Lawrence, see Lawrence, The Id, the Ego, and Equal Protection:

Reckoning with Unconscious Racism, 39 Stan. L. Rev. 317 (1987)

has said:

[T]raditional notions of intent do not reflect the fact

that decisions about racial matters are influenced in

large part by factors that can be characterized as

neither intentional . . . nor unintentional . . . a

large part of the behavior that produces racial

discrimination is influenced by unconscious racial

motivation. |

Id. at 322. Lawrence argues that Americans share a common

cultural heritage in which racism has played a dominant role.

Out of this has developed a common cultural belief system

containing certain tacit understandings of which we are largely

unaware. Because they are so widespread in society and are

never, or rarely, directly taught, these beliefs and

understandings are less likely to be experienced at the conscious

level, and even if they do surface occasionally, are quickly

refused recognition because they conflict with a shared moral

code which rejects such thoughts as "racist". Lawrence

continues:

In short, requiring proof of conscious or intentional

motivation as a prerequisite to constitutional

recognition that a decision is race-dependent ignores

much of what we understand about how the human mind

works . . . . The equal protection clause requires the

elimination of governmental decisions that take race

into account without good and important reasons.

Therefore, equal protection doctrine must find a way to

come to grips with unconscious racism.

gd. at 322.

19

Tribe has criticized the doctrine as applied in school

desegregation cases on the same grounds. Rather than contracting

the judicial role in cases of de facto segregation, Tribe

believes the arguments in favor of expanding it are much more

compelling, precisely because the exact motivations, purposes,

intentions and causes in such cases are so difficult to discern:

The harms of both de facto and de jure discrimination

are similar if not identical: racially specific harm

to members of politically less-powerful minority

groups, with discriminatory intent much more often

present than provable, and with even truly unintended

racial consequences reflecting unconscious bias and

blindness traceable to a legacy of racial subordination

initially decreed by law.

L. H. Tribe, supra p.:16, at 1500. Tribe contends that until our

society's widespread racial prejudice recedes and minority

members gain power enough to affect decisions vital to the

exercise of their fundamental rights,

[JJudicially compelled integration may be the only

acceptable response to the high probability of

governmental prejudice and corruption behind all

segregation.

Id, at 1500. See also Goodman, supra p. 15; and Dworkin, Social

Sciences and Constitutional Rights: The Consequences of

Uncertainty, 6 3. of L. and Bduc. 3 (1977).

Other commentators have criticized the current federal

approach on the grounds that it has developed from a form of

legal analysis which seeks to identify wrongdoers and hold them

responsible for "causing" harm to a protected group. Tribe has

identified the problem as one resulting from reliance on

"antidiscrimination" as the mediating principle underlying the

20

equal protection clause. L. H. Tribe, supra p. 16, at 1514. The

problem is that discrimination is an act based on prejudice, and

its essential elements are therefore an actor and an action based

on invidious grounds. Id. at 1515. When mediated by an

antidiscrimination principle, the fourteenth amendment then

becomes a tool for overturning acts motivated by racial or other

bias. Because the focus is on the "perpetrator", this leads

inexorably to the state action, discriminatory intent, and

causation standards currently employed and, therefore, to the

results in Washington v. Davis, Milliken and other cases. In

each case, Tribe asserts, the Supreme Court has noted the

disparate, harmful effect on the victim and then focused on the

intent of the perpetrator rather than the impact. Tribe suggests

that at the present stage, when the problems have become so

entrenched that intent/causation is almost impossible to prove, a

far better mediator for equal protection purposes would be the

principle of antisubjugation which aims not at preventing

discriminatory acts of wrongdoers but rather at breaking down

legally created or legally reinforced systems which treat some

people as second class citizens. L. H. Tribe, supra p. 16, at

1515. (See infra for an application of such an approach to equal

protection under the Connecticut Constitution).

Liebman raises similar concerns. He describes the Court's

move in desegregation cases from reliance on equal educational

opportunity or integration theories in the fifties and sixties,

which tended to focus on remedying the effects of government

21

decisionmaking, to the what he terms the "Correction Theory",

Liebman, supra p. 6, at 1501, which focuses on the evil acts of

wrongdoers. The moral imperative of the Correction Theory is

identical to that which motivates the law of torts, i.e., a "deep

sense of common law morality that one who hurts another should

compensate him." Id. In the desegregation context, this theory

translates into the moral claim that purposeful discrimination is

a wrong whose effects must be eliminated.

Liebman argues that the tort analogy, which fits in neatly

with process-based theories discussed above, has been appealing

to courts because it is "simple, individualistic, and by

hypothesis nonredistributive." Id. Ultimately, however, private

law solutions to public law problems are inherently unsatisfying

and ineffective. In particular, they fail to respond

satisfactorily to "insidiously prevalent, decades-long,

metropolitan-wide, multi-disciplinary and variously harmful

public racial discrimination" for the same reasons that private

law compensatory tort approaches fail to respond satisfactorily

to mass toxic disasters. Id. at 1518.

Liebman draws convincing analogies between the two cases.

He argues that the complicated character and the massive scale of

the problem in both scenarios cause the correctively critical

prerequisites of an identifiable plaintiff and an identifiable

defendant to elude proof, notwithstanding the fact that

"wrongdoers" have undoubtedly visited harms on large numbers of

plaintiffs. As a result, in both the mass toxic tort and school

22

segregation contexts, the supposed moral integrity of the

compensatory system evaporates. d. at 1519.

Tort scholars, see P. Schuck, Agent Orange on Trial: Mass

Toxic Disasters in the Courts (1986) (distinguishing private law

and public law toxic tort litigation), have drawn attention to

the problems of victims of cancer who can prove beyond doubt

their exposure to a toxic agent that is known to increase the

incidence of cancer in the population but which may be only one

of many "causes" of the victims' cancers. Typically, these

plaintiffs can also show that the agent was produced at a given

time by one or several chemical companies, but ultimately cannot

prove which. Leibman argues that the case of residentially and

educationally segregated minority children is similar, in that

they can show "exposure" to myriad acts of school, housing and

other government officials, any one of which, in addition to a

like-myriad of "neutral" factors, may have "caused" the

segregation. Liebman sees the most problematic feature of both

mass toxic tort and desegregation litigation to be the difficulty

of proving specific causation of injuries that cannot be proven

to be either "substance- or discrimination-specific." Liebman,

supra p. 6, at 1519. A further problem is linking the

plaintiffs' provable harms, known to have been "caused" by some

one or some group of defendants, to the defendant who can be

found "responsible" under the current preponderance of the

evidence rule.

Liebman concludes that as in toxic torts, the traditional

23

tort approach is not an effective legal response to the

polycentric problems posed by school desegregation cases but is

instead "an ostrich-like avoidance of them." Id. at 1521.

Moreover, the current public law approach being taken to some

mass toxic torts, using a classwide solution which relies on

proportional liability (e.g., market share) and probabilistic

proof of causation, is not transportable to the school

desegregation context; and even if it were, continued reliance on

a tort model makes even less sense when the version of that model

chosen for application completely vitiates the moral imperative

of the Correction Theory -- i.e., holding a specific wrongdoer

liable for the specific harm "caused" in the most fundamental

way. Liebman favors the abandonment of the Correction Theory in

federal jurisprudence, but, curiously, argues for the retention

of some form of the intent standard, even though he admits that

to do so makes the problem of metropolitan-wide segregation

nearly impossible to resolve. Id. at 1663.

Many commentators have argued that it would be better by far

to abandon the tort model completely as having failed to

eliminate a society-wide harm in any but the most ad hoc and

arbitrary fashion. Under the current federal approach, the Court

appears to be saying to plaintiffs, "If you can prove by a

preponderance of the evidence that a given actor's discriminatory

animus during the decisionmaking process caused the harm you are

currently suffering, in an era in which a reluctant society is

ever more skillful at disguising such animus and obliterating the

24

causal links, then we will use the full force of declaratory and

injunctive relief to remedy your suffering. If you fail to

surmount this burden, however, we must turn a blind eye to your

suffering" and, in some cases, actually deny that it exists,

thereby legitimating it.

Tribe has been a harsh critic of that particular result of

the current federal approach:

A corollary of responsible modernism is to admit that

we can see more than we can do. But this does not mean

that we should lie about what we see.

Tribe, supra p. 16, at 38.

Tribe argues that by utilizing a reference point of detached

neutrality to selectively reach in to society, make a few "fine-

tuning adjustments", and step back out, the federal courts are

ignoring the lesson of modern quantum mechanics which tells us

that the act of observing always affects what is being observed,

and that the observer is never really "detached" from the system

being studied. Id. at 13. The results courts announce, the way

they view the legal terrain, and what they say about it have

continuing effects that reshape the nature of what the courts

initially undertook to review. Id. at 20. Fiss has also

observed the power of a court's response to a given claim to

reshape both the legal and societal framework from which the

claim arose:

Shrouded in the mantle of the Constitution, dedicated

to the reasoned elaboration of our communal ideals,

courts have a unique capacity to create the terms of

their own legitimacy . . . . The moral status of a

claim may derive from its legal recognition: morality

shaped the judgment in Brown v. Board of Education and

25

that judgment then shaped our morality.

O. M. Fiss, The Civil Rights Injunction 95 (1978).

Tribe points out that the legal landscape that creates the

perception that white flight is an inherently private matter

beyond the scope of law and that the resulting ghettoization of

inner cities is therefore inevitable has itself been explicitly

shaped by Supreme Court decisions. Pierce v. Society of Sisters,

Swann, Milliken, and even Brown I (due to its original focus on

the school district rather than the state as the responsible

party) read together say in effect that white parents have the

right to keep their children in white, affluent classes by moving

to the suburbs. Tribe, supra p.16, at 27. Fiss has also

recognized that the clear legitimating message of a state's rigid

adherence to geographic criteria for school attendance is to say

to the parent who does not want her children to attend an

integrated school, your desire can be fulfilled simply by moving

to a white neighborhood. Fiss, Racial Imbalance in the Public

Schools: The Constitutional Concepts, 78 Harv. L. Rev. 564

(1965) .

Criticizing the Supreme Court's decision in Milliken as a

failure to create a rights-remedy dialogue in society which might

have eventually located a solution to the problem of

metropolitan-wide segregation, Tribe says:

Even if it would have had no impact on judicial

remedies, a judicial proclamation that inner-city

ghettoization was constitutionally infirm might have

avoided legitimating this nation-wide travesty. Had

the Court exerted the one thing it clearly can

control -- its rights declaration powers -- to

26

w»

: A

recognize the role of law and of state action in

creating ghettoization, the Court could at least have

created positive social and political tension, the sort

of tension that makes kids grow up thinking that

something is wrong, instead of inevitable, about

ghettoization.

Tribe, supra p.16, at 30.

Counselling abandonment of the current federal approach to

equal protection, Tribe suggests that the Court should be much

more willing than it has been to recognize government

responsibility for the "racially separationist consequences of

neutrally motivated acts." Id. at 33. Such recognition, he

continues, demands less an effort by courts to uncover the

"hidden levers, gears, or forces" that causally link governmental

action to objective effects than an attempt to "feel the contours

of the world government has built -- and to sense what those

contours mean for those who might be trapped or excluded by

them." Id. at 39. To announce that government bears no

responsibility for problems it has not intended to cause is to

legitimate both the governmental actions and their effects and,

worse, to relieve both governmental and non-governmental actors,

as well as other remedial fora such as state courts, executives,

and legislatures, of the responsibility for resolving these

problems. Id. at 33-34, citing Sager, Fair Measure: The legal

Status of Under-Enforced Constitutional Norms, 91 Harv. L. Rev.

1212 (1978). A far better outcome, in Tribe's view, would be a

court's admission that a protected group has been impermissibly

harmed but this court has no way to remedy it, than to say no

harm has been done or that government is not responsible for

27

finding a remedy. Arguing for a theory of government

responsibility based on the government's ability to avoid harmful

effects rather than on its intent to cause such effects, Tribe

says:

We may all be engulfed by, and dependent upon, the

structure of the law, but we are not all rendered

equally vulnerable by it. If the special dependance

upon the law and its omissions that is experienced by

the most vulnerable among us could be dismissed as

irrelevant because it was not directly created by any

state force targeting such individuals, their

heightened dependence might be seen as irrelevant. But

if the systemic vulnerability of some . . . is instead

regarded as centrally relevant to how the law's shape

should be understood, then one is more likely to ask

whether the legal system's failure to do more for such

persons might not work an unconstitutional deprivation

of their rights.

Id. at 13, (emphasis added).

b. The federal approach is based on federalist and other

institutional concerns which do not limit the power of

Connecticut courts to resolve issues under the Connecticut

Constitution. These and other differences in the two systems of

adjudication militate in favor of an independent Connecticut

approach which does not reflect the federal model.

The federal courts comprise a crucial bulwark against

evulsive depredation of constitutional values; but

against scattered erosion they are relatively

powerless.

Sager, supra p. 27, at 122s.

Like Sager, other commentators (see, e.g., L. H. Tribe,

supra p. 16, at 1513) have observed that while federal courts

28

have been effective against overt apartheid -- Jim Crow and

"white's only" signs -- the "contemporary symptoms of inertial

and unconscious prejudice are more subtle" and have proven much

more difficult to eradicate. The federal courts have been

retarded in their eradication efforts by many limitations, some

institutional, some doctrinally self-imposed, which do not apply

to state courts. The current trend, noted above, of independent

state constitutional interpretations which carve out additional

protections to those offered under the fourteenth amendment has

led to a growing perception among judges and legal scholars that

Supreme Court decisions, which we have tended to consider as the

end of the constitutional decisionmaking process, represent

instead the mid-point of an evolving system in which, if the

decision strikes down the action complained of, it sets a federal

minimum but if it upholds the action as constitutional, it may

lead to a series of "second-looks" by state decisionmakers in

which Supreme Court decisions no longer carry presumptive

validity. Williams, In the Supreme Court's Shadow: Legitimacy

of State Rejection of the Supreme Court's Reasoning and Result,

35 S.C.L. Rev. 353 (1984); See also Brennan, supra p. 5; Mosk,

The Law of the Next Century: The State Courts in American law:

The Third Century, 213, 220-25 (B. Schwartz ed. 1976)). There is

now an extensive literature favoring this trend as well as

numerous court decisions, both state and federal, which attest to

its validity.

One justification for this evolving pattern is found in the

29

fact that state courts simply are not bound by the same

institutional limitations which, whether implicitly (Milliken) or

explicitly (Rodriquez) expressed, often form the basis for a

federal decision. The first of these limitations is the Court's

concern for federalism, especially in equal protection cases.

See L. H. Tribe, supra p. 16, at 1510-12. Tribe believes that

the Supreme Court's deep reservations about the efficacy and

legitimacy of intrusive federal injunctive remedies lie at the

base of their decisions in cases involving a discriminatory

intent/causation requirement. In each case, the remedies sought

posed the risk that the federal court would become deeply

enmeshed in the machinery of state and local government, an

institutional concern that is serious and legitimate but does not

excuse the Court from ignoring the underlying problem by imposing

a threshold test. In Tribe's view (discussed in part supra),

rather than saying "there is no constitutional violation here

because no discriminatory intent has been shown," the Court

should say "there is a constitutional violation here but

institutional considerations (such as our awareness of our role

in the federal system) prevent us from offering a remedy." The

significance of this very different message is that the problem

is then passed on to other branches of government, who are

equally obliged to uphold constitutional values, for resolution.

Officers of state governments, regardless of branch, are not

restrained by the principles of federalism that may hinder a

federal court's ability, or reluctance, to enforce a decree. In

30

particular, state courts may play a role vis-a-vis the other

branches of state government that differs markedly from the

limited "interstitial" role of the federal courts. Id. at 1513.

Presumably, Tribe would approve of the U. S. Supreme Court's

approach in Rodriquez which, while denying a basis for a federal

right to education under the U. S. Constitution, clearly stated

that their decision was not to be viewed as placing its judicial

imprimatur on the status quo and, as the Connecticut Supreme

Court interpreted it in Horton I, issued a call to arms for

states to resolve the issue, unburdened by the federalist

concerns made explicit by the Supreme Court in that case. Horton

I, 172 Conn. at 634-35. Justice Peters, dissenting in Pellegrino

V. O'Neill, 193 Conn. 670, 673 (1984), expressed the idea

clearly: "We are free to consider this matter unencumbered by

the considerations of federalism which have led federal courts to

doubt the propriety of federal intervention in the administration

of state judicial systems."

A second limitation on federal constitutional analysis,

overlapping somewhat with federalist concerns above, is the state

action requirement which federal courts have derived from the "No

state shall . . ." language of the fourteenth amendment. In

addition to the obvious lack of any such limiting, state-specific

language in either of the equal protection provisions of the

Connecticut Constitution, there is an even more fundamental

reason for not importing a state action requirement into state

constitutional decisionmaking: the purpose served by that

31

requirement in interpreting the federal constitution does not

exist in the state context.

The original purpose of the state action requirement was to

shield some portion of state sovereignty from the seemingly broad

reach of the fourteenth amendment. Margulies sees the

requirement of state action as a misleading shorthand expression

which implies a balancing of interests of the complainant with

two countervailing factors: the interests of the wrongdoer and

the interests of the state in resolving the matter without

federal interference. The latter factor is missing in state

court adjudication. Margulies, A lawyer's View of the

constitution, 15 Conn. L. Rev. 107,111 (19582).

Justice Peters, dissenting in Cologne v. Westfarms

Associates, 469 A.2d 1201, 1211 (Conn. 1984), argues that the

state action requirement was designed by the federal courts to

address the demands of federalism, to create space for state

regulation. Id. at 1218, citing Tribe, supra p. 16, at 1149-50.

As discussed above, Peters believes there is no basis for a state

action requirement under state constitutions because this

"federalism component" is missing; but if the state courts should

decide to devise one independently, it should not conform to

federal law but be more flexible and "more readily found for a

claim of racial discrimination." Id. at 1218, citing Lockwood Vv.

Killian, 172 Conn. 502, 503. Justice Peters cites, Cologne, 469

A.2d at 1212-1213, numerous decisions in other state courts

rejecting a state action requirement under their state

32

“«

.

constitutions. E.g., Robins v. Pruneyard Shopping Center, 23

Cal. 34 899 (1979), aff'd, 447 U.S. 74 (1980); State v. Schmid,

84 N.J. 535, 599-60 (1980), appeal dismissed, sub nom; Princeton

Univ. v. Schmid, 455 U.S. 100 (1982); Batchelder v. Allied Stores

Int'l, Inc., 388 Mass, 83, 88-89 (1983).

When defendants assert, therefore, that plaintiffs in the

Sheff case cannot proceed without first satisfying "the state

action requirement", they are once again invoking a federal

doctrine devised by federal courts for federal purposes under the

fourteenth amendment. Technically, there is no state action

requirement under the Connecticut or any other state

constitution. In Connecticut, this assertion could be based

solely on the different language in the federal and state

provisions, a difference which many state courts have used

persuasively to avoid implying a state action requirement into

state constitutional adjudication. Williams, supra p. 29, at

369-70. But even if the language of the state and federal

provisions were exactly the same, many would agree that there

would be no inherent reason for state courts to read that

language as imposing the same limitations as have their federal

counterparts. Id. at 389-90. As Brennan has observed, supra p.

5, at 495, an increasing number of state courts have construed

state constitutions and state bills of rights as guaranteeing

even more protection than the federal provisions, even if

identical in wording. Brennan cites several cases in New Jersey,

Hawaii, Michigan, South Dakota, Maine, and other states as

33

examples of this phenomenon, id. at 499-501, and in particular

these exemplary words of the California Supreme Court: "We

declare that [the decision to the contrary of the United States

Supreme Court] is not persuasive authority in any state

prosecution in California . . . . We pause . . . to reaffirm the

independent nature of the California Constitution and our

responsibility to separately define and protect the rights of

California citizens, despite conflicting decisions of the United

States Supreme Court interpreting the Federal Constitution."

Nor are U. S. Supreme Court statements in Pruneyard and

other cases to the effect that state courts are free to interpret

their constitutions to expand constitutional rights as they see

fit the source of state power in this regard. It is now widely

accepted that a state constitution is an independent source of

rights, to be elaborated on its own terms. The majority opinion

in Cologne v. Westfarms Associates, 469 A.2d 1201, 1206,

reaffirms this principle, citing State v. Ferrell, 191 Conn. 37,

45 n.12 (1983), Griswold Inn, Inc. v. State, 183 Conn. 552, 559

n.3 (1981): Fasulo v. Arafeh, 173 Conn. 473, 475 (1977); and

Horton v. Meskill, 172 Conn. 615, 641-42 (1977).

Brennan agrees that federal court decisions are not the

source of a state's power to interpret its own constitution, and

points out further that the notion that state constitutional

provisions were intended to mirror the federal does not comport

with history, which reveals that the drafters of the federal Bill

of Rights drew on provisions of already existing state

34

constitutions as their source. Additionally, prior to the

adoption of the fourteenth amendment, the state bills of rights

were independently interpreted, since the federal Bill of Rights

had been held inapplicable. Therefore, Supreme Court decisions

"are not, and should not be, dispositive of questions regarding

rights guaranteed by counterpart provisions of state law." See

Brennen, supra p. 5, at 501-502; See also generally, Brennan, The

Bill of Rights and the States, in The Great Rights (E. Cohn ed.

1963).

In sum, despite the obvious language differences between the

Connecticut and federal equal protection provisions, the

institutional limitations on federal courts which produced the

state action requirement under the fourteenth amendment provide

Connecticut courts with ample reason to reject a state action

requirement in Connecticut equal protection cases, most

fundamentally because this requirement has nothing to do with the

substantive Connecticut constitutional guarantee of equality.

Federal doctrine is also dictated in part by other

institutional limitations which do not hamper state courts.

First, U. S. Supreme Court decisions must operate in all areas of

the nation and must, therefore, represent the lowest common

denominator of rights protection. Second, the doctrine of

selective incorporation used for applying the Bill of Rights to

the states leads to questions regarding the dilution of those

rights in a state context. Williams, supra p. 29, at 389.

Third, "state courts that rest their decisions wholly or even

35

partly on state law need not apply federal principles of standing

and justiciability that deny litigants access to the Courts."

Brennan, supra p. 5, at 501.

In addition to the institutional infirmities cited above,

Williams has cited many functional differences between federal

and state courts which militate against adopting a federal

approach to a state constitutional question. First, state courts

are often deeply involved in the state's policymaking process,

which reflects a very different institutional position from that

of the U. S. Supreme Court. Second, a state court's judicial

function is often quite different. State courts perform a great

deal of nonconstitutional law making, a power which federal

courts have been denied since Erie Railroad v. Tompkins, 304 U.S.

64 (1938). Most state supreme courts promulgate law through

their rulemaking powers and exercise various inherent powers,

often devolved upon state courts from the legislature. Williams,

supra p. 29, at 399.

In addition to the fact that state constitutional rights

provisions may differ qualitatively from the federal, other "non-

rights" provisions of state constitutions may differ from the

federal constitution so greatly as to profoundly change the

balance of power in state government. For example, many state

constitutions contain provisions enlarging judicial authority at

the expense of the legislature. Also, the text of a state

constitution may explicitly provide for judicial review of

legislative and executive action. In fact, Williams asserts,

36

judicial review was a phenomenon of state law long before Marbury

v. Madison; and contrary to the federal experience, most

judiciary provisions of state constitutions have been revised and

ratified in this century, often quite recently, without a serious

struggle over the exercise of judicial review. Williams, supra

P. 29, at 398-403.

For all of the institutional and functional differences

cited above and others, see Williams, supra p. 29, at 397-401,

the judicial review exercised by the court in the Sheff case

should be qualitatively and doctrinally different from that

exercised by the federal courts. This is particularly so in an

era in which the federal approach to school desegregation cases,

including the state action and discriminatory intent/causation

requirements, has failed overall to address so fundamental a

societal problem as metropolitan-wide segregation. Viewing U. S.

Supreme Court decisions as presumptively valid for state

constitutional analysis, as many of the older state cases tended

to do when parallel decisionmaking under provisions of both the

federal and state constitutions was still the norm, denigrates

the importance of state constitutional jurisprudence. Efforts to

limit state decisionmaking by analytical formulations and

doctrines designed to serve the purposes of the fourteenth

amendment and the federal judicial system constitute an

unwarranted delegation of state power to the federal courts and a

resultant abdication of state judicial responsibility to provide

to some of its most vulnerable citizens "the full panoply of

37

rights which Connecticut residents have come to expect as their

due." Horton I, 172 Conn. at 641.

2. Connecticut courts should develop an independent

approach to school desegregation cases under the

Connecticut State Constitution because:

a. A clear understanding of the problem to

be remedied demands an effects-based

jurisprudence focused on seqregative

condition. Such an approach is fully

supported by the express lanquage of the

Connecticut Constitution and Connecticut

case law.

Through a series of events and doctrinal missteps described

above, federal school desegregation law has moved away from the

early promise of Brown I, Green, and Swann, which held the

segregated condition of schools an unconstitutional deprivation

of equal protection, and into a process-oriented jurisprudence

which has erected a progressively more impenetrable

intent/causation barrier to resolving the unique problems posed

by metropolitan-wide segregation. It would be possible, of

course, for the Connecticut courts to avoid the full chilling

38

. v Ee

effect of this approach by carving out a narrow path through the

federal jurisprudential wilderness, much as was done by some

lower federal courts following Swann. This path could be

constructed by adopting a doctrine of state responsibility based

on the foreseeable segregative consequences of state acts. See

in general Binion, supra p. 16; Goodman, supra p. 15; Liebman,

supra p. 6. See also Note: School Desegregation after Swann: A

Theory of Government Responsibility, 39 U. Chi. L. Rev. 421, 424-

29 (arguing that segregative intent can easily be shown in

facially neutral acts such as attendance zone designation or

school site location which have the natural and probable effect

of fostering residential segregation and which may subsequently

result in racially imbalanced schools); and Fiss, supra p. 26, at

584-85 (arguing that a deliberate choice of geographic criteria

with knowledge of the probable consequences, combined with a

deliberate decision not to mitigate the consequences of the prior

choice reinforces the ascription of responsibility). The same

result could be achieved by enlarging the categories of evidence

deemed relevant in establishing intent/causation to include

"root" evidence, such as community attitudes and their effect on

elected officials and/or "branch" evidence, such as the decisions

of other branches of state government in addition to school

boards which have played a part in creating or maintaining a

segregated system in both schools and housing. See Stein, supra

p. 16, at 2005; Tribe, supra p. 16, at 1500 (this is also the

approach taken by the federal district court in Milliken). The

39

path could also be constructed by shifting the burden of proof on

intent/causation to defendants once racial isolation has been

established by objective criteria, as the U. S. Supreme Court did

in Swann. (The Connecticut Supreme Court took a similar burden

shifting approach in Horton v. Meskill, 195 Conn. 24, 37-38

(1985) (Horton IIXI)).

One might also argue that current federal doctrine

encourages the approaches described above, based on the language

in Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 464-65

(1979) which blurred the de facto-de jure distinction by

suggesting that, even in a city like Columbus which had had no

statutorily mandated segregation in this century, disparate

racial impact and foreseeable consequences could be "fertile

ground for drawing inferences of segregative intent," even though

they "do not, without more, establish a constitutional

violation." Even under federal law, the argument has been made

that the textual, philosophical and practical difficulties that

militate against the recognition of an affirmative constitutional

duty to act -- the negative constitutional language of the

fourteenth amendment, the state action doctrine, and the problem

of tangible standards and remedies -- do not apply, at least not

as forcefully, to questions of exclusion once the state has

undertaken to act. See Goodman, supra p. 15.

All of these avenues could be utilized by Connecticut courts

seeking a "way around" the federal standards. Constructing such

a pathway under Connecticut law would, however, be a mistake.

40

All of the approaches suggested above were developed in response

to federal decisions which were dictated by federal concerns and

the language of the fourteenth amendment. In addition, all have

been designed to conform to the so called process theory of

constitutional law which holds (see supra) that courts must not

intervene to remedy the conditions of segregation which have

resulted from myriad government and private decisions unless this

condition was "caused" by defects in the decisionmaking process

itself, i.e., that the process was infected with discriminatory

bias. Agreeing with Fiss that "[t]here is no independent or

objective standard that can fairly ensure that race has not

influenced governmental decisions," Fiss, supra p. 26, at 575

(emphasis added), we strongly suggest that the Connecticut courts

reject the federal approach in full and carve out a distinctive

jurisprudence based solely on the original understanding that

informed Brown and all school desegregation cases prior to

Keyes -- i.e., that it is the seqregative condition itself which

constitutes the wrong which must be remedied.

The Connecticut approach should take note of the fact that

the goal of a school desegregation case is structural reform.

Structural reform is premised on the notion that the quality of

our social life is affected in important ways by the operation of

large scale organizations. The structural suit is one in which a

judge, confronting a state bureaucracy over values of

constitutional dimension, undertakes to restructure the

organization to eliminate the threat to those values posed by the

41

R A : :

present institutional arrangement. Fiss, The Supreme Court 1978

Term: Forward: The Forms of Justice, 93 Harv. L. Rev. 1, 2

(1978). The ultimate focus of the judicial inquiry is not

particularized and discrete events or acts, but rather a social

condition that threatens important constitutional values and the

organizational dynamic that perpetuates that condition. Id. at

18.

In the structural context, Fiss continues, one function,

that of the "wrongdoer", virtually disappears. The concept of

"wrongdoer" presumes personal qualities: the capacity to have an

intention and to choose. In a structural suit, however, the

focus is not on incidents of wrongdoing but, rather, on a social

condition and the bureaucratic dynamics that produced that

condition. The costs and burdens of reformation are placed on

the organization, not because it has "done wrong" in either a

literal or metaphysical sense "for it has neither an intention

nor a will," but because reform is needed to remove a threat to

constitutional values posed by the operation of the organization.

Id. at 22-23. A school desegregation case is a paradigmatic

structural lawsuit, in which it is alleged that the segregated

condition of the schools in and of itself violates the

constitutional right of students attending those schools to equal

protection of the laws.

The remedy at issue in a structural case is the structural

injunction. O. M. Fiss, supra p. 25. As opposed to preventive

or reparative injunctions, the structural injunction is used to

42

effectuate the reorganization of an ongoing social institution.

Id. at 7. In a structural injunction context, like a school

desegregation case, it is imperative to see that "the

constitutional wrong is the structure itself; the reorganization

is designed to bring the structure within constitutional bounds."

Id. at 11. Such an injunction does not require a judgment about

wrongdoing, future or past. The structural suit and its

injunctive (and/or declarative) remedy seeks to eradicate an

ongoing threat to our constitutional values . . . . [I]t speaks

to the future. Fiss, supra p. 41, at 23.

An understanding of the need for structural reform in

achieving equal educational opportunity, as well as the

usefulness of the structural injunction in achieving that reform,

was expressed clearly by the Connecticut Supreme Court in Horton

IX11:

Our own cases have similarly acknowledged that a court,

in the exercise of its discretion to frame injunctive

relief, must balance the competing equities of the

parties to assure the relief it grants is compatible

with the equities of the case, Dukes v. Durante, 192

Conn. 207, 225 (1984); and takes account of the

possibility of embarrassment to the operations of

government. CEUI v. CSEA, 183 Conn. 235, 248-49

(1981).

Horton TIX, 195 Conn. at 47.

In a school desegregation case, the courts focus must turn

away from the process by which schools become segregated toward

the segregated condition itself and the effects of this condition

on the lives of school children, their families, and their

communities. This is, in fact, the constitutional wrong to be

43

remedied, because it is the effects of racial isolation which

constitute, per se, the deprivation of equal protection and equal

educational opportunity which the Connecticut Constitution

forbids.

Many commentators agree with the structural approach

advocated by Fiss under which government responsibility attaches,

regardless of intent or causation, when the state fails to remedy

the racial imbalance which the state has within its power to

avoid. Since public school attendance is compulsory and the

state and its delegated agents have complete control over

attendance zones, school sites, student assignments, and all

other components of a school system, not to mention the other

units of state government which impact upon the problem, it is

proper to hold the state accountable for harm which can be

prevented. Note, supra p. 39, at 440. All governmental units

are interconnected in many ways, and it would not be unreasonable

to think in terms of the cumulative effect of all governmental

activity and to hold particularly responsible the unit that has

within its power the most effective method of correcting one

facet of the cumulative impact, racially imbalanced schools.

Fiss, supra p. 26, at 587. Tribe has strongly advocated such

an approach, based on a new mediating principle which better

comports with the underlying goal of equal protection. Tribe

argues that the antidiscrimination principle, which has been used

as an equal protection mediator for many years in school

desegregation cases, requires a "perpetrator" who engages in the

44

invidious act of discriminating. This requirement leads

inexorably to a jurisprudence based on state action,

discriminatory intent and causation, and the subsequent

"travesty" of Milliken. Tribe suggests that at the present

stage, when the problems have become so entrenched that

intent/causation is almost impossible to prove, a far better

mediating principle for equal protection cases would be the

antisubjugation principle, which aims not at preventing

discriminatory acts, but rather at breaking down legally

reinforced systems of subordination that treat some people as

second class citizens. "The core value of this principle is that

all people have equal worth," which comes much closer to the core

value underlying the equal protection clause. L. H. Tribe, supra

P. 16, at 1515.

The goal of the equal protection clause is not to stamp out

impure thoughts, Tribe continues, but to guarantee a full measure

of dignity to all citizens. The Constitution may be offended not

only by discrete acts of social discrimination, but also by

governmental rules, policies, and practices that perennially

reinforce the subordinate status of any group. Mediated by the

antisubjugation principle, the equal protection clause asks

whether the particular conditions complained of deprive a

particular group of its right to be fully human. Id. at 1516.

Tribe observes that the anitdiscrimination principle may be

sufficient to contend with the deprivations of equal protection

that result from isolated instances of overt impropriety or

45

[BJut the subjugation of blacks, women, and other

groups today persisting is usually neither isolated nor

hysterical. Regimes of sustained subordination

generate devices, institutions, and circumstances that

impose burdens or constraints on the target group

without resort to repeated or individualized

discriminatory actions.

Id. at 1518. Tribe cites Kovel, J. Kovel, White Racism: A

Psychohistory 60-66 (1971), as reminding us that the inequities

that persist in American society have survived this long because

they have become ingrained in our modes of thought. And as the

U. S. Supreme Court recognized a century ago in Strauder v. West

Yiraginia, 100 U.S. 203, 306 (1880), habitual discrimination is

the hardest to eradicate. Tribe criticizes the Supreme Court's

current approach to equal protection under the fourteenth

amendment because the government cannot be held accountable to

the constitutional norm of equality unless it has actively

created a particular set of conditions at least in part "because

of", not merely "in spite of", its adverse effects upon an

identifiable group. (Citing Personnel Administrator v. Feeney,

422 U.S. 256 (1979). This process-oriented approach, which Tribe

has criticized harshly in other writings, see Tribe, supra p. 16,

at 564, overlooks the fact that minorities can be harmed when the

government is only "indifferent" to their suffering, or merely

blind as to how prior official discrimination contributed to it,

and how current official acts or omissions will perpetuate it.

L. H. Tribe, supra p. 16, at 1518-19. (Fiss has described the

same phenomenon as the "policy of disregard." See Fiss, supra p.

26, at 565). Tribe argues that the pseudo-scienter requirement

46

26, at 565). Tribe argues that the pseudo-scienter requirement

of Washington v. Davis, Keyes, and other cases is, therefore,

utterly alien to the basic concept of equal justice under law.

Whereas the antidiscrimination principle and the intent/causation

requirement which it has spawned look inward to the perpetrator's

state of mind, the antisubjugation principle looks outward to the

victim's state of existence, L. H. Tribe, supra p. 16, at 1519,

and allows the court to focus on the denial of humanity which

that state imposes on certain citizens. In a school

desegregation case, the anitsubjugation principle implies that by

focusing on the condition of segregation existing in the schools

of the nation's metropolitan ghettoes and by declaring outright