Bryan v Koch Reply Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1980

9 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bryan v Koch Reply Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1980. 15391737-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8490b9a7-ce12-4e71-ade7-bdd16c2abe7a/bryan-v-koch-reply-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

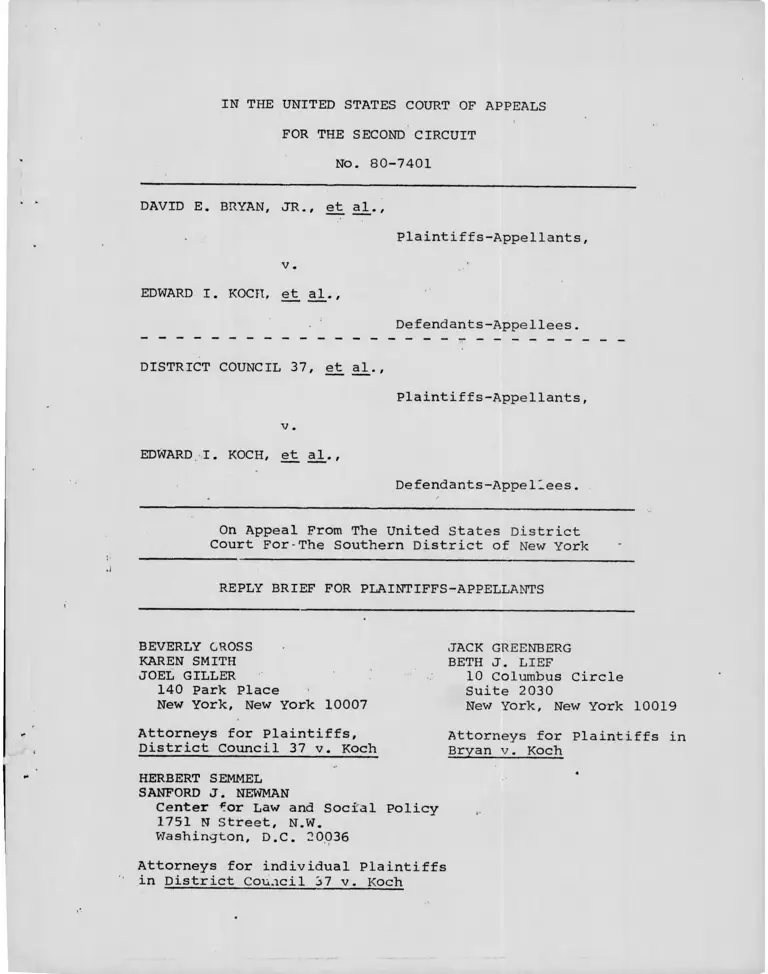

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

NO. 80-7401

DAVID E. BRYAN, JR., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v .

EDWARD I. KOCH, et al_. ,

Defendants-Appellees.

DISTRICT COUNCIL 37, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v .

EDWARD I. KOCH, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District

Court For-The Southern District of New York

REPLY BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

BEVERLY CROSS

KAREN SMITH

JOEL GILLER

140 Park Place

New York, New York 10007

JACK GREENBERG

BETH J. LIEF

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs,

District Council 37 v. Koch Attorneys for Plaintiffs in

Bryan v . Koch

HERBERT SEMMEL

SANFORD J. NEWMAN

Center for Law and Social Policy

1751 N Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

Attorneys for individual Plaintiffs

in District Council 37 v. Koch

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

No. 80-7401

DAVID E. BRYAN, JR., e* ?!.,

Plaintiffs-Appe Hants,

v .

EDWARD I. KOCh, et al..

Defendants-Appellees.

DISTRICT COUNCIL 37, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v .

EDWARD I. KOCH, et al.,

Defendancs-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District

Court For The Southern District of New York

REPLY BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

The complaints in these actions each alleged that the

conduct of the defendants, in addition to violating Title VI,

also contravened the requirements of the regulations issued

by HHS. App. 12, 22, 246, 255. The trial court expressly

recognized, as did the defendants below, that those regula

tions, 42 C.F.R. § 80.3, establish a disparate impact

standard. The court expressly held that the regulations,

together with the HHS opinions and r jcommendations elaborat

ing on their meaning, are invalid. App. 590-600. In this

Court appellees discussion of the regulations is largely-

limited to the contention that the regulations are not entitled

to deference in construing Title VI. Appellees Brief, pp. 31-

35. We urge that, even if Title VI itself applies only to

instances .of discriminatory purpose, the regulations forbid

ding certain types of disparate racial impact would nonetheless

be valid.

It is clear beyond peradventure that an agency authorized

under a statute may at times establish by regulation new obliga

tions not contained in the statute itself. "[T]he role of

regulations is not merely interpretative; they may instead

be designedly creative in a substantive sense, if so authorized

Usery v. Turner Elkhorn Mining Co., 128 U.S. 1, 37, n. 40 (1976)

In Mourning v. Family Publications Service, 411 U.S. 356

(1973), the Federal Reserve Board had promulgated a regulation

under the Truth in Lending Act requiring the disclosure of

certain information, such as the total cost of the goods, in

any instalment transaction involving more than four payments.

12 C.F.R. '§ 226.2(k). Although the Truth in Lending Act itself

required disclosures only if the case of transactions involving

a finance charge, the Board's regulation required disclosures

regardless of whether there was a finance charge so long as

more than four instalment's were involved. The defendant in

that case challenged the regulation, arguing it created obliga

tions not contained in the statute itself, and was in excess

- 2 -

of the Board's authority. The Supre le Court unanimously

rejected that contention.

The defendant in Mourning, like the court below, recog

nized that the power to issue regulations ordinarily authorized

regulations "reasonably related to the purposes of the enabling

legislation", Thorpe v. Housing Authority of Durham, 393 U.S.

268, 280-81 (1969), but urged that the statute and regulation

were "inconsistent" because the regulation created obligations

not found in the statute." The purported conflict arises be

cause the statute specifically mentions disclosure only in

regard to transactions in which a finance charge is in fact

imposed, although the rule requires disclosure in some cases

in which no such charge exists." Mourning, 411 U.S. at 372.

Compare App. 592-93. But the Supreme Court held that the im

position of obligations on parties Vvuo might not be within

the coverage of the statute was permissible. It recognized

that some contracts providing for more than four instalments

would involve hidden finance charges, and held that the Board

was not obligated to determine in each case whether there was

such a charge and the Act itself applied.

The fact that the regulation applied the obligations of

the statute to some individuals who had not violated and were

not covered by the act itself did not render the regulation

invalid.

- 3 -

Where, as here, the transaction or conduct

which Congx ass seeks to administer occur in

myriad and changing forms, a requirement that

a line be drawn which insures that not one

blameless individual will be subject to the

provisions of an act would unreasonably encumber

effective administration . . .

411 U.S, at 356.

The Court also sanctioned the ust of regulations broader

than the underlying statute in Gem co v. Walling, 324 U.S.

244 (1945). In that case the Administrator of the Wage and

Hour Division was charged with enforcing the minimum wage

provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act. Although the

Act itself established no limitations on where workers could

be employed, the Administrator forbade employers from giving

their employees work to do at home. The Administrator reasoned

that it could not effectively monitor the number of hours

being worked. Gemsco, however, argued that the regulation

was invalid, urging, not only that homework had not been for

bidden by the act, but that it was "an independent subject

matter wholly without the .statute1s purview . . .." 324 U.S.

at 261. 3ut the Court held that the regulation was lawful

because it was reasonably directed at achieving the statutory

objectives. 324 U.S. at 259.

Title VI, in addition to prohibiting discrimination,

authorizes and directs every federal agency granting federal

assistance "to effectuate the provisions of section 20006 of

this title . . . by issuing rules, regulations, or orders of

general applicability' . ..." 42 U.S.C. § 2000d-l. This is

on its face a grant cf authority comparable to that in Mourning,

- 4 -

and broader than that in Gemsco, which was effectively limited

to preventing e\asion. See 324 U.S. at 248. As four members

of the Supreme Court noted in University of California Regents

v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978).

Attorney General Robert Kennedy testified that

regulations had not been written into the legislation

itself because the rules and regulatxons defining dis

crimination might differ from ore program to another

so that the term would assume different meanings in

different contexts. 438 U.S. at 343. (Opinion of

Justices Brennan, Marshall, White and Blackmun)

(Emphasis added).

Clearly the definition of "discrimination" could only vary

from program to program, as thus contemplated, if the agencies

were authorized to define it as something other than just

"purposeful discrimination." The action of eight Federal

agencies in promulgating in 1964 substantive regulations

demonstrates their view, to which deference is certainly due,

that section 2000d-l authorized the establishment of such

substantive requirements which did not merely incorporate

the language of the statute or the Fourteenth Amendment.

The majority opinion .in Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563

(1974), cited both Title VI and the regulations at issue in

this case. While the majority seems to have read Title VI

itself to create an effect standard, it held that the practices

in Lau had the "earmarks of the discrimination banned by the

regulations," 414 U.S...at 568. (Emphasis added),. Although

the majority did not reach the question of the validity of

the regulation section 80.3 if its commands exceeded those

of the statute, three members of the Courc did so. Justice

Stewart, in an opinion joined by Justice Blackmun and the

- 5 -

Chief Justice, expressed doubts as to whether Title VI,

"standing alone, would render illegal the expenditure of

funds" on the disputed schools. 414 U.S. at 570.

On the other hand the interpretive guidelines

published by the Office of Civil Rights of the

Department of Health, Education and Welfare . . .

clearly indicate that affirmative efforts to give

special training for non-English-speaking pupils

are required by Title VI . . .. The critical

question is, therefore, whether the regulations and

guidelines promulgated by HEW go beyond the authority

of section 601.

414 U.S. at 570-71. Relying on Mourning, Justice Stewart

held the disparate impact regulation valid as "reasonably

related to the purposes of the enabling legislation." 414

U.S. at 571.

Although only three members of the Supreme Court have

expressed an opinion as to whether, regulation section 80.3

V

would be valid even if Title VI itself required proof of dis

criminatory purpose, Justice Stewart's view is clearly correct

The regulations require remedial action where the conduct of

a grant recipient has a disproportionately adverse impact on

minorities and other means exist for achieving the purported

purpose of that action. Certainly prohibiting grantee conduct

which has such an impact furthers the anti-discriminatory

policy of Title VI, regardless of whether Title VI itself

applies only to intentional discrimination. The existence of

such a disparate impact alone is clearly significant evidence

r '•of discriminatory purpose; where the recipient's professed

purpose for its action could have been achieved without so

burdening minorities, that fact raises serious questions as

to whether tnat purpose was the actual or sole motive involved

- 6 -

Thus the circumstances specified by the regulation, like

more than four instalmentcontracts in Mourning and the use

of homework in Gemsco. gives substantial reason to believe

that the underlying statute is being violated. HHS, like

the Federal Reserve Board or the Wage and Hour Administrator,

is not obligated to determine or consider on a case by case

basis whether such a violation actually occurred. The problems

involved in establishing the presence or absence of discrimina

tory intent are enormously difficult, consistently confounding

and dividing the federal courts. See, e.g., City of Mobile

v. Bolden, 48 U.S.L.W. 4436 (1980). HHS was well within its

authority in promulgating an adverse impact standard which,

although cccasionally covering conduct and individuals not

in violation of the Act, afforded a more administrable and

predictable method by which HHS, the courts, and recipient

agency themselves could test a proposed course of action.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

BETH LIEF

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Appellants in Bryan v . Koch

BEVERLY GROSS

KAREN SMITH

JOEL GILLER

140 Park Place

New York, New York

- 7 -

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Appellants in District Council

37 v. Koch

HERBERT SEMMEL

SANFORD NEWMAN

Center for Law and Social

Policy-

1751 N. Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Appallants in District Council

37 v. Koch

MARGARET MCFARLAND

University of Michigan

Intern, Center for Law and

Social Policy

- 8 -