Gregg v. Georgia Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gregg v. Georgia Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1976. d871e7a0-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/849bbaaa-5d03-4e59-a46a-d1d4533256f0/gregg-v-georgia-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

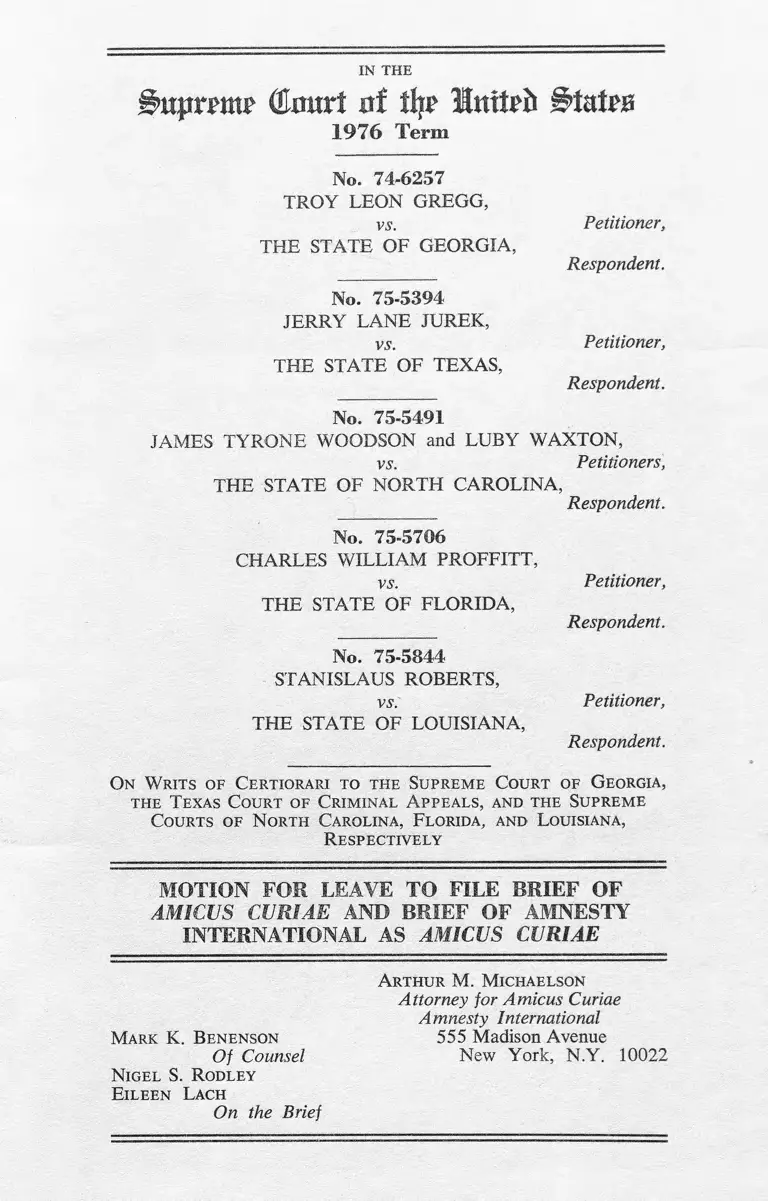

IN THE

j&qiratt? (Unurt nf % Imtefr

1976 Term

No. 74-6257

TROY LEON GREGG,

vs. Petitioner,

THE STATE OF GEORGIA,

Respondent.

No. 75-5394

JERRY LANE JUREK,

vs. Petitioner,

THE STATE OF TEXAS,

Respondent.

No. 75-5491

JAMES TYRONE WOODSON and LUBY WAXTON,

vs. Petitioners,

THE STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA,

Respondent.

No. 75-5706

CHARLES WILLIAM PROFFITT,

vs. Petitioner,

THE STATE OF FLORIDA,

Respondent.

No. 75-5844

STANISLAUS ROBERTS,

vs. Petitioner,

THE STATE OF LOUISIANA,

Respondent.

On Writs of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia,

the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, and the Supreme

Courts of North Carolina, F lorida, and Louisiana,

Respectively

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF OF

AMICUS CURIAE AND BRIEF OF AMNESTY

INTERNATIONAL AS AMICUS CURIAE

Arthur M. Michaelson

Attorney for Amicus Curiae

Amnesty International

Mark K. Benenson 555 Madison Avenue

Of Counsel New York, N.Y. 10022

Nigel S. Rodley

Eileen Lach

On the Brief

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Table of Authorities ................................................. ii

Motion for Leave to File Brief of Amicus Curiae . . . 2

Interest of the Amicus Curiae........................... . 2

Brief of Amicus Curiae....... ..................................... 5

A rgument :

I.—In the absence of authoritative legislative

guidance, the Court, in deciding the death

penalty question, makes a moral decision

which can determine a standard of the hu

mane governance of society if founded on the

sanctity of the right to l i f e .......................... 6

II.—The Court has a unique opportunity to fulfill

a dual role (a) in following the lead of other

humane nations in abolishing the death pen

alty and (b) in serving as a leader to other

nations which have not yet abolished the

death penalty ................................................. 9

III.—The United Nations Charter, interpreted

through the Universal Declaration of Human

Rights and the Covenant on Civil and Po

litical Rights, promotes the humane gov

ernance of society and thus, the abolition of

the death penalty in the United States . . . . 13

Conclusion ............................................................................. 18

A ppendix ................................................................................. A -l

11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases :

A. F. of L. v. American Sash and Door Co., 335

U.S. 538 (1949) ................................................... 10

Bacardi Corp. v. Domenech, 311 U.S. 150 (1940) 14

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) 6

Commonwealth v. O’Neal, No. 3502 (Mass. Sup.

Jud. Ct., Dec. 22, 1975) .................................... 9

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24 (1948) ........................ 13

Kennedy v. Mendosa-Mar tines, 372 U.S. 159 (1963) 17

Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 649 (1948) ........... 13,14

Poivell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932) ................ 6

Shelley v. Kramer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) ................ 6

The Paquette Habana, 175 U.S. 677 (1900) ......... 9

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958) ........................ 10

Wyatt v. Stickney, 344 F. Supp. 387 (M.D. Ala.

1972) ................................................................... 17

U nited N ations D ocum ents:

Charter of the United Nations, June 26, 1945, 59

Stat. 1031 (1945), T.S. No. 993 (effective Oct.

24, 1945) ....................................................13,14,15,17

Const. U.N. Food and Agricultural Organization

(FAO), Oct. 16, 1945, 12 U.S.T. 980, T.I.A.S.

No. 4803 ............................................................ 7

Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural

Rights, the Covenant on Civil and Political

Rights, and the Optional Protocol, G.A. Res.

2200, 21 GAOR Supp. 16, at 48, U.N. Doc.

A/6316 (1966) ................................................... 15,16

G.A. Res. 103, U.N. Doc. A/64/Add. 1 at 200

(1946) ........................................ 14

G.A. Res. 2857, 26 GAOR Supp. 21, at 94, U.N.

Doc. A/8421 (1971) .............................................. 17

PAGE

1X1

I.C.J. Stat. Art. 3 8 ................................................. 15

Universal Declaration of Human Bights, G.A. Res.

217, U.N. Doc. A/810 at 71 (1948) .................... 15>17

Vienna Convention on the Law of treaties, May

22, 1969 [1972], U.N. Doc. A/CONF. 39/26

(1969) .................................................................. lb ' 11

The World Food Conference Declaration on the

Eradication of Hunger and Malnutrition, U.N.

Doc. SEC/E. 75 II. A. 3, 1 (1974) .................... 7

PAGE

U nited N ations R eports :

United Nations, Economic and Social Council,

Commission on Human Rights (E/CN. 4/1111)

(February 1, 1973) ............................... ...........

United Nations, Economic and Social Council, Re

port of the Secretary-General, Capital Punish-

ment (E/5242) (February 23, 1973) ......... 7,10,11,17

United Nations, Economic _ and Social Council,

Commission on Human Rights (E/CN. 4/1159)

(January 24, 1975) .............................................. ■*-'

United Nations, Economic and Social Council, Re

port of the Secretary-General, Capital Punish

ment (E/5616) (February 12, 1975) ................ 9, 11

United Nations, Economic and Social Council, Re

port of the Secretary-General Addendum, Capi

tal Punishment (E/5615/Add. 1) (April 18,

1975) .................................................................... 11

United Nations, Economic and Social Council, Re

port of the Social Committee,_ Social Develop

ment Questions (E/5664) (April 25, 1975).......... L

Yearbook on Human Rights, U.N. Sales No. E. 48.

XIV. l _ E. 74. XIV. 1 .......................................

M iscellaneous :

Ancel, The Death Penalty in European Countries

(Council of Europe 1962) ...................................

Bowers, Executions in America (1974) ................

IV

PAGE

Cahn, The Moral Decision (1955) ........................ 6

Camus, Reflections on the Guillotine, R esistance,

R ebellion and D eath 131 (Mod. Lib. 1960) . . . . 8

Darrow, The Negative of Dehate Resolved: that

Capital Punishment is a Wise Public Policy

(1924) .................................................................. 8

Falk, The Role of Domestic Courts in the Inter

national Legal Order (1964) ............................. 6

Goodrich, Hambro and Simons, Charter of the

United Nations (3rd Ed. 1969) .......................... 13

Kakoullis, The Myths of Capital Punishment

(Center for Responsible Psychology, Brooklyn

College, C.U.N.Y.) Report No. 13, 1974 ............. 9

Koestler, Reflections on Hanging (Victor Gollancz

Ltd. 1956) ............................... 8

McDougal, The Law School of the Future: from

Legal Realism to Policy Science in the World

Community, 56 Yale L. J. 1345 (1947) . ............. 6

Peaslee, Constitutions of Nations (The Hague, M.

Nijhoff 1956) ..................................................... 12

Schwelb, Human Rights and the International

Community, the Roots and Growth of Human

Rights, 1948-1963 (1964) ................................... 16

Sohn, Editorial Comment, 62 A.J.I.L. 909 (1968) 15

IN THE

B>ujjr?mp (tart at % Hmtrft Btutm

1 9 7 6 Term

No. 74-6257

T roy- L eon Gregg,

Petitioner,

vs.

T he S tate of Georgia,

Respondent.

No. 75-5394

J erry L ane. J urek ,

Petitioner,

vs.

T h e S tate of T exas,

Respondent.

No. 75-5491

J ames T yrone W oodson and L uby W axton,

Petitioners,

vs.

T he S tate of N orth Carolina,

No. 75-5706

Respondent.

C harles W illiam P roffitt,

Petitioner,

vs.

T h e S tate of F lorida,

No. 75-5844

Respondent.

S tanislaus R oberts,

Petitioner,

vs.

T he S tate of L ouisiana,

Respondent.

■o

2

Osr W rits op Certiorari to the S upreme Court

of Georgia, the T exas Court of Criminal

A ppeals, and the S upreme Courts of

N orth Carolina, F lorida, and

L ouisiana, R espectively

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF OF

AMICUS CURIAE AND BRIEF OF AMNESTY

INTERNATIONAL AS AMICUS CURIAE

M otion for Leave to File Brief

Annesty International, by its attorney, Arthur M. Michael-

son, moves for leave to file a brief Amicus Curiae in sup

port of petitioners.

Interest o f the Amicus Curiae

The Amicus Curiae, Amnesty International, is a non

partisan private international humanitarian organization

which works to secure for all persons the right freely to

hold and express their convictions as guaranteed in the

United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Article 1 of Amnesty International’s Statute (copy at

tached as Appendix A), as amended September 8, 1974,

reads in pertinent p a rt:

Considering that every person has the right

freely to hold and to express his convictions and

the obligation to extend a like freedom to others, the

objects of A mnesty I nternational shall be to secure

throughout the world the observance of the provi

3

sions of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,

by:

* # #

(c) opposing by all appropriate means the

imposition and infliction of death penalties and

torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading

treatment or punishment of prisoners or other

detained or restricted persons whether or not

they have used or advocated violence.

Amnesty International was founded in London in 1961

and now has national sections in over thirty countries,

including the United States, with approximately 50,000

individual members in some sixty countries.

Amnesty International has formal consultative status

with the United Nations, UNESCO, the Organization of

American States, the Council of Europe, the Interameri-

can Commission of Human Rights, and in regard to

refugees, the Organization of African Unity. Many mem

bers of these organizations (e.g. the United Nations,

UNESCO, the Council of Europe and the Organization of

American States) have abolished the death penalty de jure;

others have de facto stopped executions. I t also is the world

wide experience of Amnesty International that the death

penalty is applied in a highly discriminatory fashion against

ethnic and religious minorities, against political prisoners,

against the disadvantaged.

Amnesty International does not approve of and would

not defend any violent crime. However, it cannot regard

the death penalty other than as an anachronism and an act

of cold blood beneath the dignity of a modern state.

4

Amnesty International frequently appeals to govern

ments not to impose, or to commute, sentences of death

upon “ political” criminals. It believes that if the death

penalty were abolished in the United States, other nations

would be greatly influenced to follow in the same course.

Accordingly, Amnesty International moves for leave to

file the following brief as amicus curiae.

Respectfully submitted,

A rthur M. M ichaelson

Attorney for Amicus Curiae

Amnesty International

555 Madison Avenue

New York, N. Y. 10022

Mark K. B enenson

Of Counsel

N igel S. R od-ley

E ileen L aoh

On the Brief

IN THE

Bupnmx (Ernxt at % MnlUb

1976 Term

-------------------o-------------------

No. 74-6257

TROY LEON GREGG,

VS.

Petitioner,

THE STATE OF GEORGIA,

Respondent.

No. 75-5394

JERRY LANE JUREK,

vs.

Petitioner,

THE STATE OF TEXAS,

Respondent.

No. 75-5491

JAMES TYRONE WOODSON and LUBY WAXTON,

Petitioners,

vs.

THE STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA, i

Respondent.

No. 75-5706

CHARLES WILLIAM PROFFITT,

vs.

Petitioner,

THE STATE OF FLORIDA,

Respondent.

No. 75-5844

STANISLAUS ROBERTS,

vs.

Petitioner,

THE STATE OF LOUISIANA,

Respondent.

On Writs of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia,

the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, and the Supreme

Courts of North Carolina, F lorida, and Louisiana,

Respectively

-------- -----------o-—--------------- -

BRIEF OF AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL AS

AMICUS CURIAE

6

A R G U M E N T

I .

I n the aSisence o f specific constitu tional d irec tion , the

C ourt, in decid ing the death penalty question , m akes

a m ora l decision w hich can d e te rm in e a s tan d ard o f the

h u m an e governance o f society if fo u n d ed on th e sanctity

o f th e rig h t to life .

The issue of the death penalty presents the court with

a question devoid of specific constitutional direction.

There is no explicit language by which the Court is to be

governed, but rather it must interpret the Eighth and

Fourteenth Amendments. Judicial interpretation which

results in law is a process of value realization, a reflection

of standards of and for the community.1 Consequently, in

an area such as the issue of the death penalty, the Court

is left to determine an aspect of the humane evolution of

society.2

The abolition of the death penalty is a useful standard

of development for a nation which historically has pro

nounced and demonstrated its concern for human rights

law. It is also a valid indicator by which a society may

measure its humanity. The acceptance or rejection of the

1 For a brief summaries and views of law as a value-realizing

process see Cahn, The Moral Decision (1955); McDougal, The Law

School of the Future; from Legal Realism to Policy Science in the

World Community, 56 YALE L.J. 1345, 1345-50 (1947). A similar

perspective concerning internationally significant issues and their rela

tion to domestic courts can be found in R. Falk, The Role of

Domestic Courts in the International Legal Order (1964).

2 The Court has assumed this task in many notable decisions, e.g.

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932); Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U.S. 1 (1948); Brown v. Board of Education, 247 U.S. 483 (1954).

7

humane standard is a moral question which concerns both

the sanctity of life and the humane governance of a nation.3

The dignity of human life and the right to life have

had a history of legal recognition.4 Other extended rights

have been predicated on the basic right to life, tending to

show the inalienability of the right.5

The possibility of mistake accentuates a realization of

3 The Secretary-General of the United Nations noted:

The debate on the death penalty continues to revolve around

two main questions of its morality and its usefulness. The moral

issue is the right of any society to put any person to death, i.e.

to deny him his basic human rights to live. The question of the

utility of capital punishment turns essentially on its efficiency

in preventing crime.

He also observed:

In some respects it is surprising that these [moral and utili

tarian] issues of principle are not yet settled . ..

United Nations, Economic and Social Council, Report of the

Secretary-General, Capital Punishment (E/5242) 4 and 3 (February

23, 1973). Also reprinted in United Nations, 31 Int’l Rev. Crim.

Pol’y 91, 92 (1974) [hereinafter Secretary-General’s Report 1973],

4 See Point III infra, concerning the provisions and acceptance of

the United Nations Charter, the International Bill of Human Rights

and the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties.

5 Note, for example, the predicative assumptions of The World

Food Conference Declaration on the Eradication of Hunger and

Malnutrition, U.N. Doc. SEC/E. 75 II.A.3, 1 (1974) meeting under

the authorization of Const. U.N. Food and Agricultural Organ

ization (FAO), Oct. 16, 1945, 12 U.S.T. 980, T.I.A.S. No. 4803:

Recognizing that:

The grave food crisis that is afflicting the peoples of the devel

oping countries where most of the world’s hungry and ill-

nourished live and where more than two-thirds of the world’s

population produce about one third of the world’s food . .

is not only fraught with grave economic and social implications,

but also acutely jeopardizes the most fundamental principles and

values associated with the right to life and human dignity as

enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

8

the sanctity of life which no temporal process is empowered

to abridge. Camus points out this basic concept:6

A classic treatise of French law, in order to

excuse the death penalty for not involving degrees,

states this: “ Human justice has not the slightest

desire to assure such a proportion. Why? Because

it knows it is frail.” Must we, therefore, conclude

that such frailty authorizes us to pronounce an abso

lute judgment and that, uncertain of ever achieving

pure justice, society must rush headlong, through

the greatest risks, toward supreme injustice?. . . .

Compassion does not exclude punishment, but it

suspends the final condemnation. Compassion

loathes the definitive, irreparable measure that does

an injustice to mankind as a whole . . .

The limitation on the power of and potential for abuse

by the state follows from the recognition of the sacredness

of life free from the ultimate interference of a state-imposed

death penalty. A society is entitled to choose the means

by which it protects its citizens. However, the means

selected under a system of humane governance should be

limited to methods which positively deter criminal be

havior. It is not clear that the death penalty fulfills that—

6 A. Camus, Reflections on the Guillotine, in Resistance,

Rebellion and Death 131, 165-66 (Mod. Lib. 1960). See A.

Koestler, Reflections on Hanging (Victor Gollancz, Ltd. 1956).

See also C. Darrow, The Negative of Debate Resolved: That

Capital Punishment is a Wise Public Policy, 41 (1924).

9

or any—utilitarian purpose.7 Human rights law, from

Magna Carta onward, serves to limit the abuse of indi

viduals by the national power. The conception of a society

under a humane system of government has evolved since

that time, through legal decisions which shape human rights

standards. In the absence of specific constitutional im

peratives, the Court in this group of cases decides a pro

found question of humane societal governance and stand

ards of human rights. A cognizance of the right to life is

fundamental to the decision.

I I .

T he C ourt has a u n iq u e o p p o rtu n ity to fu lfill a dual

ro le (a ) in fo llow ing the lead o f o th e r hum ane nations

in abolish ing th e death penalty and (b ) in serving as a

leader to o th e r na tions w hich have not yet abolished the

dea th penalty.

The Court has long been sensitive to the imperatives

“ of this country’s status and membership in the community

of nations” .8 Within the context of its deliberations on

7 United Nations, Economic, and Social Council, Report of

the Secretary-General, Capital Punishment (E/5616) 4 (February

12, 1975) [hereinafter Secretary-General’s Report 1975] states:

In the past the United Nations has considered most of the

problems involved in capital punishment. The focus in the UN

reports on capital punishment of 1962 and 1967 was on the

deterrent effect of the death penalty. The conclusion of these

reports was that no significant differences between the rates of

capital offenses could be found before and after the abolition

of the death penalty in abolitionist countries. They also indicated

that in general, no significant differences could be found in

the rates of capital offences in countries with capital punishment

and those in countries without it.

Commonwealth v. O’Neal, No. 3502 (Mass. Sup. Jud. Ct., Dec. 22,

1975). See Bowers, Executions in America 160 (1974); Kako-

ullis, The Myths of Capital Punishment (Center for Responsible

Psychology, Brooklyn College, C.U.N.Y.) Report No. 13, 1974.

8 The Paquette Habana, 175 U.S. 677, 700 (1900).

1 0

other international issues, it has been mindful of the prac

tices of other nations.9 In fact, there is precedent for the

Court to survey international practices and policy in form

ing judgments as to the cruelty of punishments.10

The practices and policies of the Western European

nations, the group of nations with which the United States

readily identifies in its juridico-cultural heritage, provide

guidance in their commitment to humane standards in the

abolition of capital punishment.11 This is particularly

significant in a violent world where, as the United Nations

has noted:

As new forms of terror and violence evolve in

society, the tendency to revert to the death penalty

as the main deterrent is conspicuously increased.12

The overwhelming majority of European nations have

abolished the death penalty de jure or de facto for “ ordi

0 See, e.g. A.F. of L. v. American Sash and Door Co., 335 U.S.

538, 548 (1949), in which the Court considered collective bargain

ing, “in the light of the experience of countries advanced in industrial

democracy, such as Great Britain and Sweden”.

10 Trap v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 103 (1958) which concerns

whether loss of citizenship due to military desertion is crued and un

usual punishment.

11 The following discussion of Western European de jure and de

facto abolition is limited to those situations similar to the facts of the

cases presently before the Court. We do not consider herein the use

of the death penalty for acts of terrorism, treason, state assassination

or political acts related to the security of the state in times of war or

extreme national turbulence. The Secretary-General’s Report 1973

refers to the excluded class as “political” offenses. The remainder

constitute “ordinary” crimes. Secretary-General’s Report 1973, 9,

94.

12 Secretary-General’s Report 1973, 4, 92.

1 1

nary crimes” 13 as a minimum.14 Legislation in Europe

within the past ten years has displayed an increasing trend

toward total abolition of the death penalty.15 Several

13 See note 11, supra.

14 A total of twenty-two nations have abolished capital punish

ment since 1863. Those in Western Europe are: Austria, de jure

in 1945; Belgium, de facto; Denmark, de jure in 1930 for ordinary

crimes; Finland, de jure in 1949; Federal Republic of Germany,

de jure in 1949; Iceland, de jure in 1928; Italy, de jure in 1944 for

ordinary crimes; Luxembourg, de facto with no executions for at

least 40 years; Netherlands, de jure in 1870 for ordinary crimes;

Norway, de jure in 1905 for ordinary crimes; Portugal, de jure in

1867 for ordinary crimes; Sweden, de jure in 1921; United Kingdom,

de jure in 1969 for ordinary crimes. For a definition of “ordinary”,

see note 11, supra. Secretary-General’s Report 1975, Tables 1 and 2.

For a history of Western European abolition of capital punish

ment, see M. Ancel, The Death Penalty In European Coun

tries (Council of Europe 1962).

15 In 1973 Denmark, which since 1930 had retained the death

penalty only in time of war, amended the Military Criminal Code

to limit the scope of criminal offenses for which the death penalty

could be imposed. United Nations, Economic and Social

Council, Report of the Secretary-General Addendum, Capital Pun

ishment (E/5616/Add. 1) 1-2 (April 18, 1975).

In 1921 Sweden abolished de jure the death penalty in times of

peace. From July 1, 1973 it extended the abolition to wartime as

well, thus becoming the tenth nation to completely abolish the death

penalty. Secretary-General’s Report 1975, 7.

The United Kingdom abolished the death penalty for an experi

mental period by the Death Penalty Act of 1965, and made the

action permanent by affirmative resolutions of both Houses of Par

liament in 1969. A capital offense under the Dockyards Protection

Act of 1792 was repealed by the Criminal Damage Act of 1971.

These reforms occurred despite a considerable upsurge in terrorism.

Ibid.

In February 1968, Austria abolished the death penalty for the

execptional crimes to which it could still be applied. Secretary-

General’s Report 1973, 10.

On June 1, 1972, Finland abolished the death penalty during

wartime, the only time it had previously been allowed. Ibid.

12

European nations have, in fact, incorporated the abolition

of the death penalty into their national constitutions.10

This state of affairs has led the United Nations Counsel on

Economics and Social Affairs to observe tha t:

. . . in the period 1969-1973 further progress has

been made in some countries by abolishing capital

punishment either totally or for ordinary crimes, or

by suspending it, or by restricting the number of

capital offences . . .1T

The overwhelming abolition of the death penalty in

Western Europe provides the Court with a sound model

for a decision holding capital punishment unconstitutional.

The example of other societies which have adopted this as

pect of a commitment to humane standards urges such a

decision and supports its moral rightness.

The Court in the present case has a second unique op

portunity to affect the leadership capacity of the United

States in global affairs. All but 22 countries 16 17 18 currently

allow for the death penalty. If the United States, pre

eminent in physical power among the nations, joined the

ranks of those humane states which have abolished capital

punishment, it could not fail to positively influence a re

consideration of the death penalty among its remaining

adherents.

16 For example, Austria, West Germany, Italy and Portugal. For

the texts of these and other constitutional abolition provisions, see

A. Peaslee, Constitutions of Nations (The Hague, M. Nijhoff

1956).

17 United Nations Economic and Social Council, Report

of the Social Committee, Social Development Questions, (E/5664)

6 (April 25, 1975).

18 See note 14, supra.

13

T he U nited N ations C harter, in te rp re te d th ro u g h the

U niversal D eclara tion o f H um an R ights and th e Covenant

on Civil and P o litica l R ights, p rom otes th e h um ane gov

ernance o f society and thus , th e abo litio n o f the death

penalty in th e U nited States.

Chronologically, the Court’s recognition of the rele

vance of international legal considerations to domestic

adjudications19 followed the creation of the United Nations

Organization and United States adherence to the Charter.

The Court has noted that under Articles 55C and 56 of

the Charter “ we have pledged ourselves to cooperate with

the United Nations to promote universal respect for, and

observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms

for all without distinction as to race, sex, language or

religion.’’20 The “ good faith” clause of the Charter,

19 Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24, 34-35 (1948).

20 Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633, 649 (1948) (Black,

concurring). Article 55 of the Charter of the United Nations,

June 26, 1945, 59 Stat. 1031 (1945), T.S. No. 993 (effective Oct.

24, 1945), reads in relevant part:

With a view to the creation of conditions of stability and

well-being which are necessary for peaceful and friendly rela

tions among nations based on respect for the principle of equal

rights and self-determination of peoples, the United Nations

shall promote: ❖ * ❖

c. universal respect for, and observance of, human rights

and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to

race, sex, language, or religion.

Article 56 reads:

All Members pledge themselves to take joint and separate

action in cooperation with the Organization for the achieve

ment of purposes set forth in Article 55.

The records of the San Francisco meetings on the drafting of the

Charter illustrate that the framers attached importance to the words

“separate action”. The qualifying words “in cooperation” were

intended to prevent direct United Nations intervention in domestic

affairs rather than to limit the obligation of member nations to

observe human rights. See Goodrich, Hambro and Simons,

Charter of the United Nations, 380-82 (3rd ed. 1969).

I I I .

14

Article 2,21 lias been applied in practice by the Court in

invalidating an Alien Land Law which prohibited land

ownership by Japanese.22 * * 2 Although unmentioned by the

Court, its decision was consistent with an act of the Gen

eral Assembly in which that body had voted in a 1946

Resolution on Persecution and Discrimination, to call “ on

the Governments . . . to conform both to the letter and

to the spirit of the Charter. ’,2a

Alternative methods exist to read general provisions

in terms of more specific human rights to be protected

under the United Nations Charter. A right to individual

freedom from capital punishment may be interpreted

through a principle of construction similar to that articu

lated by the Court in Bacardi Corp. v. Domenech, 311 U.S.

150, 163 (1940) :

According to the accepted canon, we should con

strue the treaty liberally to give effect to the pur

pose which animates it. Even where a provision of

a treaty fairly admits of two constructions, one

restricting, the other enlarging, rights which may

be claimed under it, the more liberal interpretation

is to be preferred.

21 U.N. Charter art. 2, para. 2:

All members, in order to ensure to all of them the rights and

benefits resulting from membership, shall fulfill in good faith

the obligations assumed by them in accordance with the present

Charter.

22 Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. at 673 (Murphy, concur

ring) :

The Alien Land Law stands as a barrier to the fulfillment of

that national pledge [to the United Nations Charter], Its in

consistency with the Charter, which has been duly ratified and

adopted by the United States, is but one more reason why the

statute must be condemned.

2S G.A. Res. 103, U.N. Doc. A /64/Add. 1 at 200 (1946).

15

In the alternative, the rights sought to be protected by

the United Nations Charter may be established with a

reading of:

(a) any subsequent agreement between the par

ties regarding the interpretation of the treaty or

the applications of its provisions;

(b) any subsequent practice in the application

of the treaty which establishes the agreement of the

parties regarding its interpretation;

(c) any relevant rules of international law ap

plicable in the relations between the parties.24

Within the human rights context, the International Bill

of Human Rights25 constitutes a. subsequent agreement

which reflects the general principles of law recognized by

the overwhelming majority of nations and international

customs of general practice. Indeed, it is commonly ac

cepted that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

has become a part of international customary law and, in

that sense, can be construed as an interpretation of the

United Nations Charter.20 Given that general interpre- 24 25

24 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, May 22, 1969

[1972], U.N. Doc. A/Conf. 39/26 (1969), Art. 31(3) (a)-(c).

25 The International Bill of Human Rights comprises four docu

ments: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, G.A. Res 217,

U.N. Doc. A/810 at 71 (1948), and the Covenant on Economic,

Social and Cultural Rights, the Covenant on Civil and Political

Rights, and the Optional Protocol, G.A. Res. 2200, 21 GAOR Supp.

16, at 48, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1966).

201.C.J. Stat. Art. 38.

Evidence that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights has

secured the status of international customary law is reflected generally

in the country by country reporting series of the United Nations,

Yearbook on Human Rights, U.N. Sales No. E. 48. XIV. l.-E. 74.

XIV. 1. (covering 1948-1971). See the Editorial Comment by Louis

B. Sohn, 62 A.J.I.L. 909 (1968), which reviews the accepted status

of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

16

tation, support for more specific rights, like the freedom,

from capital punishment, can be established.

Two particular constituent elements of this customary

law of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights are

relevant to the issue of the death penalty, Article 3:

Everyone has the right to life, liberty and the

security of person.

and Article 5:

no one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel,

inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

The right to life specified by Article 3 of the Universal

Declaration of Human Rights is reaffirmed by Article 6 of

the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights* 27

which provides that “ Every human being has the inherent

right to life. This right shall be protected by law. . . . ”

The Charter of the United Nations, the Universal Declara

tion of Human Rights and the other unanimously adopted

declarations of the United Nations have established a legislative

framework for the protection of human rights throughout the

world. The Montreal Statement of the Assembly for Human

Rights, of March 27, 1968, expressed the general consensus of

international experts that the “Charter of the United Nations,

the constitutional document of the world community, creates

binding obligations for Members of the United Nations with

respect to human rights”; and that the “Universal Declaration of

Human Rights constitutes an authoritative interpretation of the

Charter of the highest order, and has over the years become a

part of customary international law.” Similarly, the intergov

ernmental Proclamation of Teheran, of May 13, 1968, empha

sized that the “Universal Declaration of Human Rights states a

common understanding of the peoples of the world concerning

the inalienable and inviolable rights of all members of the human

family and constitutes an obligation for the members of the

international community.”

See also E. Schwelb, Human R ights and the International

Community, The Roots and Growth of Human Rights, 1948-

1963 (1964).

27 While the Covenant does not outlaw the use of capital punish

ment, it demands restrictions. Furthermore, Article 6 indicates what

the trend ought to be. Article 6, paragraph 6 provides that:

Nothing in this Article shall be invoked to delay or prevent

the abolition of capital punishment by any States Party to the

present Covenant.

17

The United Nations has considered these Articles as

standards by which the legitimacy of capital punishment

is to be measured..28 Taken as standards, the Articles

strongly suggest that the freedom from capital punishment

is a right supported under “ subsequent”29 interpretation

of the United Nations Charter. It is a right which may

legitimately be recognized and protected by nations which,

like the United States, have pledged to take action con

sistent with the thrust of the United Nations Charter which

states as essential to a felicitous future for our species,

“ universal respect for, and observance of, human rights.”30

28 United Nations. Economic and Social Council. Commis

sion on Human Rights (E/CN. 4/1111) 7 (February 1, 1973);

United Nations, Economic and Social Council, Commission on

Human Rights (E/CN. 4/1159) 10 (January 24, 1975); Secretary-

General’s Report 1973, Annex II, 101.

29 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, May 22, 1969

[1972], U.N. Doc. A/CONF. 39/26 (1969), Article 31 (3) (a)-

(c).

30 Note 20, supra.

Although the resolutions of the General Assembly do not carry

the obligations of agreements or customary practice flowing from

the United Nations Charter, they provide a source of evidence on

general customary law and the resolutions of important international

legal issues. The Court in the past has consulted the work product

of United Nations resolutions, e.g., Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez,

372 U.S. 159, 161 n. 16 (1963).

Resolutions of the United Nations have “the intention . . . to

promote abolition” of the death penalty. Secretary-General’s Re

port 1973, 20, 99. The linkage to Article 3 of the Universal

Declaration of Human Rights is clear:

[I]n order fully to guarantee the right to life, provided for in

Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the

main objective to be pursued is that of progressively restricting

the number of offences for which capital punishment may be

imposed with a view to the desirability of abolishing this punish

ment in all countries.

G.A. Res. 2857, 26 GAOR Supp. 21, at 94, U.N. Doc. A/8421

(1971).

See also Wyatt v. Stickney, 344 F.Supp. 387, 390 n. 6 (M.D.

Ala. 1972) where the Court’s “decision with regard to habilitation

is supported not only by applicable legal authority, but also by a

resolution adopted on December 27, 1971, by the General Assembly

of the United Nations”.

18

CONCLUSION

The death penalty shou ld be abolished .

Respectfully submitted,

A rthur M. M ichael,son

Attorneyfor Amicus Curiae

Amnesty International

555 Madison Avenue

New York, 1ST. Y. 10022

M ark K. B enenson

Of Counsel

N igel S. R odley

E ileen L ach

On the Brief

A -l

APPEND IX

S ta tu te o f A m nesty In te rn a tio n a l

As amended by the seventh International Council meeting

in Aslcov, Denmark, 8 September 1974

Objects

1. Considering that every person has the right freely to

hold and to express his convictions and the obligation to

extend a like freedom to others, the objects of A mnesty

I nternational shall be to secure throughout the world the

observance of the provisions of the Universal Declaration

of Human Rights, by:

(a) irrespective of political consideration work

ing towards the release of and providing assistance

to persons who in violation of the aforesaid provi

sions are imprisoned, detained, restricted or other

wise subjected to physical coercion or restriction by

reason of their political, religious or other conscien

tiously held beliefs or by reason of their ethnic ori

gin, colour or language, provided that they have not

used or advocated’violence (hereinafter referred to

as ‘Prisoners of Conscience’).

(b) opposing by all appropriate means the deten

tion of any Prisoners of Conscience or any political

prisoners without trial within a reasonable time or

any trial procedures relating to such prisoners that

do not conform to recognized norms to ensure a fair

trial.

(c) opposing by all appropriate means the im

position and infliction of death penalties and torture

or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or

punishment of prisoners or other detained or re

stricted persons whether or not they have used or

advocated violence.

A-2

Appendix

Methods

2. In order to achieve the aforesaid objects, A mnesty

I nternational shall:

(a) at all times maintain an overall balance be

tween its activities in relation to countries adhering

to the different world political ideologies and group

ings;

(b) promote as appears appropriate the adop

tion of constitutions, conventions, treaties and other

measures which guarantee the rights contained in

the provisions referred to in article 1 hereof;

(c) support and publicize the activities of and

cooperate with international organizations and

agencies which work for the implementation of the

aforesaid provisions;

(d) take all necessary steps to establish an effec

tive organization of national sections, affiliated

groups and individual members;

(e) secure the adoption by groups of members or

supporters of individual Prisoners of Conscience or

entrust to such groups other tasks in support of the

objects set out in article 1;

(f) provide financial and other relief to Prisoners

of Conscience and their dependents and to persons

who have lately been Prisoners of Conscience or who

might reasonably be expected to become Prisoners

of Conscience if they were to return to their own

countries and to the dependants of such persons;

(g) work for the improvement of conditions for

Prisoners of Conscience and political prisoners;

(lx) provide legal aid, where necessary and pos

sible to Prisoners of Conscience and to persons who,

A-3

if convicted, might reasonably be considered likely

to become Prisoners of Conscience and, where desir

able, send observers to attend the trial of such per

sons;

(i) publicize the cases of Prisoners of Conscience

or persons who have otherwise been subjected to dis

abilities in violation of the aforesaid provisions;

(j) send investigators, where appropriate, to in

vestigate allegations that the rights of individuals

under the aforesaid provisions have been violated

or threatened;

(k) make representations to international organi

zations and to governments whenever it appears that

an individual is a Prisoner of Conscience or has

otherwise been subjected to disabilities in violation

of the aforesaid provisions;

(l) promote and support the granting of general

amnesties of which the beneficiaries will include

Prisoners of Conscience;

(m) adopt any other appropriate methods for the

securing of its objects.

Organization

3. A mnesty I nternational shall consist of na tiona l

sections, affiliated groups, ind iv idual m em bers and corpo

ra te m em bers.

4. The directive au th o rity for the conduct of the affairs

of A mnesty I nternational is vested in the International

Council.

5. Between meetings of the International Council, the

International Executive Committee shall be responsible for

Appendix

A-4

the conduct of the affairs of A mnesty I nternational and

for the implementation of the decisions of the International

Council.

6. The day to day affairs of A mnesty I nternational

shall be conducted by the International Secretariat headed

by a Secretary General under the direction of the Inter

national Executive Committee.

7. The office of the International Secretariat shall be in

London or such other place as the International Council

may determine.

N ational S ections

8. A national section of A mnesty I nternational may

be established in any country, state or territory with the

consent of the International Executive Committee. In order

to be recognized as such, a national section shall (a) consist

of not less than two groups or 10 members, (b) pay such

annual fee as may be determined by the International

Council, (c) be registered as such with the International

Secretariat on the decision of the International Executive

Committee. National sections shall take no action on mat

ters that do not fall within the stated objects of A mnesty

I nternational. The International Secretariat shall main

tain a register of national sections.

9. Groups of not less than three members or supporters

wishing to adopt Prisoners of Conscience may, on payment

of an annual fee determined by the International Council,

become affiliated to A mnesty I nternational or a national

section thereof. Airy dispute as to whether a group should

be or remain affiliated shall be decided by the International

Executive Committee. An affiliated group shall accept for

Appendix

A-5

adoption such prisoners as may from time to time be al

lotted to it by the International Secretariat, arid shall adopt

no others as long as it remains affiliated to A mnesty I nter

national. No group shall be allotted a Prisoner of Con

science detained in its own country. The International

Secretariat shall maintain a register of affiliated groups.

Groups shall take no action on matters that do not fall

within the stated objects of A mnesty I nternational.

Appendix

I ndividual Membership

10. Individuals residing in countries where there is no

national section may, on payment to the International Sec

retariat of an annual subscription fee determined by the

International Executive Committee, become members of

A mnesty I nternational. In countries where a national

section exists, individuals may become members of

A mnesty I nternational, with the consent of the national

section. The International Secretariat shall maintain a

register of such members.

Corporate Membership

11. Organizations may, at the discretion of the Inter

national Executive Committee and on payment of an annual

subscription fee determined by the International Executive

Committee, become corporate members of A mnesty I nter

national. The International Secretariat shall maintain a

register of corporate members.

I nternational Council

12. The International Council shall consist of the mem

bers of the International Executive Committee and of

representatives of national sections and shall meet at inter

A-6

vals of approximately one year but in any event of not

more than two years on a date fixed by the International

Executive Committee. Only representatives of national sec

tions and members of the International Executive Commit

tee elected by the International Council shall have the right

to vote on the International Council.

13. National sections may appoint representatives as

follows:

2 - 9 groups — 1 representative

10 - 49 groups — 2 representatives

50- 99 groups — 3 representatives

100 -199 groups — 4 representatives

200 - 399 groups — 5 representatives

400 groups or over — 6 representatives

National sections consisting primarily of individual mem

bers rather than groups may in alternative appoint repre

sentatives as folows:

50- 499 — 1 representative

500 - 2499 — 2 representatives

2500 and over — 3 representatives

Only sections having paid in full their fees as assessed by

the International Council for the previous financial year

shall vote at the International Council. This requirement

may be waived in whole or in part by the International

Executive Committee.

14. Representatives of groups not forming part of a

national section may with the permission of the Secretary

General attend a meeting of the International Council as

observers and may speak thereat but shall not be entitled

to vote.

Appendix

A-7

15. A national section unable to participate in an Inter

national Council may appoint a proxy or proxies to vote

on its behalf and a national section represented by a lesser

number of persons than its entitlement under article 13

hereof may authorize its representative or representatives

to cast votes up to its maximum entitlement under article

13 hereof.

16. Notice of the number of representatives proposing

to attend an International Council, and of the appointment

of proxies, shall be given to the International Secretariat

not later than one month before the meeting of the Inter

national Council. This requirement may be waived by the

International Executive Committee.

17. A quorum shall consist of the representatives or

proxies of not less than one quarter of the national sections

entitled to be represented.

18. The Chairman of the International Executive Com

mittee, or such other person as the International Executive

Committee may appoint, shall open the proceedings of the

International Council, which shall elect a chairman. There

after the elected Chairman, or such other person as he may

appoint, shall preside at the International Council.

19. Except as otherwise provided in this statute, the

International Council shall make its decisions by a simple

majority of the votes cast. In case of an equality of votes

the Chairman of the International Executive Committee

shall have a casting vote.

20. The International Council shall be convened by the

International Secretariat by notice to all national sections

and affiliated groups not later than 90 days before the date

thereof.

Appendix

A-8

21. The Chairman of the International Executive Com

mittee shall at the request of the Committee or of not less

than one-third of the national sections call an extraordinary

meeting of the International Council by giving not less

than 21 days notice in writing to all national sections.

22. The International Council shall elect a Treasurer,

who shall be a member of the International Executive

Committee.

23. The International Council may appoint one or more

Honorary Presidents of A mnesty I nternational to hold

office for a period not exceeding three years.

24. The International Council shall from time to time,

and not less than once in five years, call an International

Assembly consisting of all members of A mnesty I nterna

tional, of national sections and of affiliated groups. Such

an Assembly shall be for the purposes of information, dis

cussion and consultation and shall not have the power to

adopt any decisions.

25. The agenda for meetings of the International Coun

cil shall be prepared by the International Secretariat under

the direction of the Chairman of the International Execu

tive Committee.

I nternational E xecutive Committee

26. (a) The International Executive Committee shall

consist of the Treasurer, one representative of the staff of

the International Secretariat and seven regular members,

who shall be members of A mnesty I nternational, or of a

national section, or of an affiliated group, elected by the

International Council by proportional representation by

the method of the single transferable vote in accordance

Appendix

A-9

with the regulations published by the Electoral Reform

Society. Not more than one member of any national sec

tion or affiliated group may be elected as a regular member

to the Committee, and once one member of any national

section or affiliated group has received sufficient votes to

be elected, any votes cast for other members of that national

section or affiliated group shall be disregarded.

(b) Members of the permanent staff, paid and unpaid,

shall have the right to elect one representative among the

staff who has completed not less than two years’ service

to be a voting member of the International Executive

Committee. Such member shall hold office for one year and

shall be eligible for re-election. The method of voting shall

be subject to approval by the International Executive

Committee on the proposal of the staff members.

27. The International Executive Committee shall meet

not less than twice a year at a place to be decided by itself.

28. Members of the International Executive Committee,

other than the representative of the staff, shall hold office

for a period of two years and shall be eligible for re-elec

tion. Except in the case of elections to fill vacancies result

ing from unexpired terms of office, the members of the

Committee, other than the representative of the staff, shall

be subject to election in equal proportions on alternate

years.

29. The Committee may co-opt not more than four addi

tional members who shall hold office for a period of one

year; they shall be eligible to be re-co-opted. Co-opted

Members shall not have the right to vote.

30. In the event of a vacancy occurring on the Commit

tee, it may co-opt a further member to fill the vacancy until

Appendix

A-10

the next meeting of the International Council, which shall

elect such members as are necessary to replace retiring-

members and to fill the vacancy.

31. If a member of the Committee is unable to attend a

meeting, he may appoint an alternate.

32. The Committee shall each year appoint one of its

members to act as Chairman.

33. The Chairman may, and at the request of the ma

jority of the Committee shall, summon meetings of the Com

mittee.

34. A quorum shall consist of not less than three mem

bers of the Committee or their alternates.

35. The agenda for meetings of the Committee shall

be prepared by the International Secretariat under the

direction of the Chairman.

36. The Committee may make regulations for the con

duct of the affairs of A mnesty I nternational, and for the

procedure to be folowed at the International Council.

I nternational S ecretariat

37. The International Executive Committee may ap

point a Secretary General who shall be responsible under

its direction for the conduct of the affairs of A mnesty I n

ternational and for the implementation of the decisions of

the International Council.

38. The Secretary General may, after consultation with

the Chairman of the International Executive Committee,

and subject to confirmation by that Committee, appoint

such executive and professional staff as appear to him to be

Appendix

A -ll

necessary for tlie proper conduct of the affairs of A mnesty

I nternational, and may appoint such other staff as appear

to him to be necessary.

39. In the case of the absence or illness of the Secretary

General, or of a vacancy in the post of Secretary General,

the Chairman of the International Executive Committee

shall, after consultation with the members of that Commit

tee, appoint an acting Secretary General to act until the

next meeting of the Committee.

40. The Secretary General or Acting Secretary Gen

eral, and such members of the International Secretariat

as may appear to the Chairman of the International Ex

ecutive Committee to be necessary shall attend meetings

of the International Council and of the International Ex

ecutive Committee and may speak thereat but shall not be

entitled to vote.

T ermination oe Membership

41. Membership of or affiliation to A mnesty I nterna

tional may be terminated at any time by resignation in

writing.

42. The International Council may, upon the proposal

of the International Executive Committee or of a national

section, by a three-fourths majority of the votes cast de

prive a national section, an affiliated group or a member

of membership of A mnesty I nternational if in its opinion

that national section, affiliated group or member does not

act within the spirit of the objects and methods set out in

articles 1 and 2 or does not observe any of the provisions

of this statute. Before taking such action, all national sec

tions shall be informed and the Secretary General shall

also inform the national section, affiliated group or member

Appendix

A-12

of the grounds on which it is proposed to deprive it or him

of membership, and such national section, affiliated group

or member shall be provided with an apportunity of pre

senting its or his case to the International Council.

43. A national section, affiliated group or member who

fails to pay the annual fee fixed in accordance with this

statute within six months after the close of the financial

year shall cease to be affiliated to A mnesty I nternational

unless the International Executive Committee decides other

wise.

F inance

44. An auditor appointed by the International Council

shall annually audit the accounts of A mnesty I nterna

tional, which shall be prepared by the International Secre

tariat and presented to the International Executive Com

mittee and the International Council.

A mendments oe S tatute

45. The statute may be amended by the International

Council by a majority of not less than two-thirds of the

votes cast. Amendments may be submitted by the Inter

national Executive Committee or by a national section.

Proposed amendments shall be submitted to the Interna-

national Secreariat not less than two months before the

International Council meets, and presentation to the Inter

national Council shall be supported in writing by at least

five national sections. Proposed amendments shall be com

municated by the International Secretariat to all national

sections and to members of the International Executive

Committee.

Appendix