In Re: Campaign of Senator Bilbo Brief for the NAACP

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1946

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. In Re: Campaign of Senator Bilbo Brief for the NAACP, 1946. 5b45f0e1-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/84bbdf3e-b023-402c-b738-2a23f5a0b49c/in-re-campaign-of-senator-bilbo-brief-for-the-naacp. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

1946

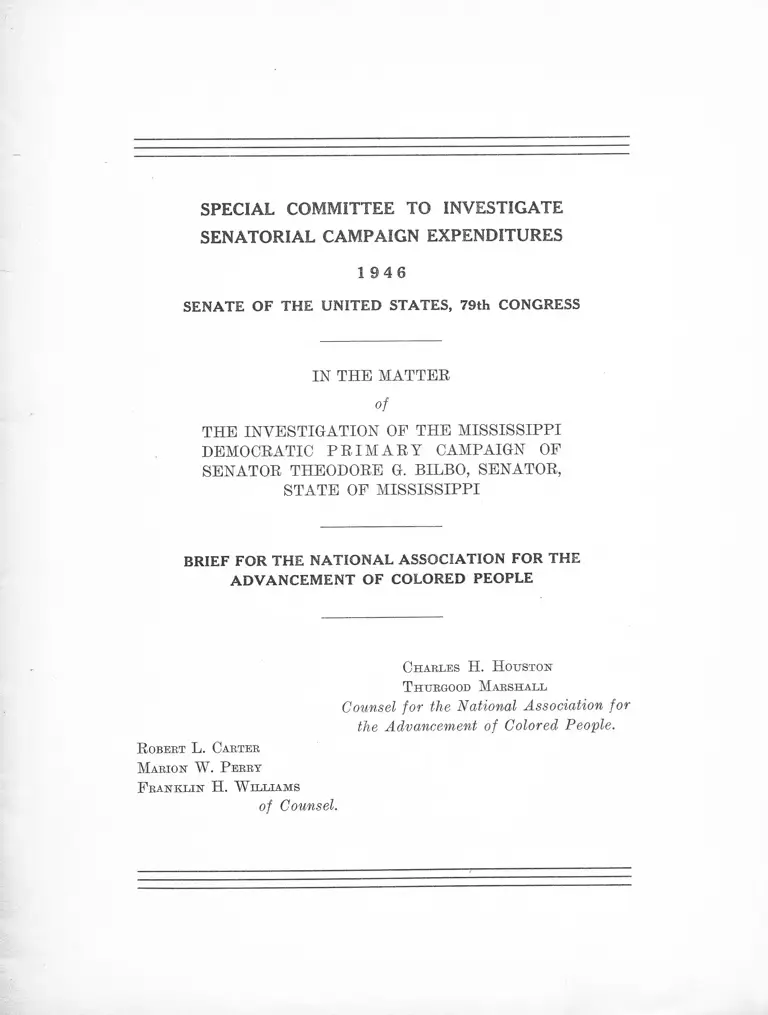

SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES, 79th CONGRESS

SPECIAL COMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE

SENATORIAL CAMPAIGN EXPENDITURES

IN THE MATTER

of

THE INVESTIGATION OF THE MISSISSIPPI

DEMOCRATIC P R I M A R Y CAMPAIGN OF

SENATOR THEODORE G. BILBO, SENATOR,

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE

ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE

Charles H . H ouston

T hurgood M arshall

Counsel for the National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People.

R obert L. Carter

M arion W . P erry

F ra n k l in H. W illiam s

of Counsel.

1 9 4 6

SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES, 79th CONGRESS

SPECIAL COMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE

SENATORIAL CAMPAIGN EXPENDITURES

I n th e M atter

of

T h e I nvestigation of th e M ississippi D emocratic

P rim ary Cam paign of S enator T heodore Gr.

B ilbo, S enator, S tate of M ississippi.

T o: T h e H onorable, T h e M embers of t h e S pecial . Com m ittee to

I nvestigate S enatorial Cam paign E xpenditures—1946:

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

respectfully requests leave to file the accompanying supplemental brief

in the above-named investigation.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

for more than 37 years has dedicated itself to and worked for the

achievement of a functioning democracy and equal justice under the

Constitution and laws of the United States. This organization now

represents 1407 branches in 44 states and the District of Columbia with

a membership of more than 500,000. Its membership includes persons

of all races and creeds.

Prom time to time, issues are presented to the courts and the legis

lative bodies of the United States, the decision of which charts the

future course of the evolving institutions in some vital area of our

national life. Such an issue is presently being considered by your

Committee.

2

The purpose of the immediate investigation is to ascertain whether

the conduct of Senator-elect Theodore G. Bilbo, of Mississippi, during

his 1946 Democratic Primary campaign in the said state was of such

a nature as to taint with fraud and corruption the credentials for a

seat in the Senate of the 80th Congress by the said Senator-elect

Theodore G. Bilbo.

In behalf of our one-half million members and the people of the

United States generally who are interested in the qualifications of our

national legislators, the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People submits this brief for your consideration and respect

fully urges that Senator-elect Bilbo be denied a seat in the Senate of

the United States for the 80th Congress on the grounds that his acts

and conduct during the 1946 Democratic Primary campaign in the

State of Mississippi were contrary to sound public policy, harmful to

the dignity and honor of the Senate, dangerous to the perpetuity of free

government and have tainted with fraud and corruption his credentials

for a seat in the Senate.

C harles H . H ouston

T hurgood M arshall

Counsel for the National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People.

R obert L. Carter

M arion W . P erry

F ra n k lin H . W illiam s

of Counsel.

3

1 9 4 6

SE N A TE OF T H E U N ITE D STATES, 79th CONGRESS

SPECIAL COMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE

SENATORIAL CAMPAIGN EXPENDITURES

I n th e M atter

of

T h e I nvestigation oe t h e M ississippi D emocratic

P rim ary C am paign oe S enator T heodore G.

B ilbo , S enator, S tate of M ississippi.

BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE

ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE

Nature of the Case

The Special Committee to Investigate Senatorial Campaign Ex

penditures for 1946 was appointed pursuant to Senate Resolution No.

224, 79th Congress, 2d Session. One of the specific considerations

included within the scope of its powers was the investigation of the 1946

Democratic Primary campaign conducted by Senator-elect Theodore

G. Bilbo, Democrat, of the State of Mississippi. The Committee, having

held public hearings in the City of Jackson, Mississippi, on the 2nd,

3rd, 4th and 5th days of December, 1946, is now required to report its

findings to the Senate and its recommendations for action to be taken

thereon.

P is respectfully submitted that this report should show that

Senator-elect Bilbo was guilty of acts and conduct which were contrary

4

to sound public policy, harmful to the dignity and honor of the Senate,

dangerous to the perpetuity of free government and of such a nature

as to taint with fraud and corruption the credentials for a seat in the

Senate presented by him; and, that based thereon the Senate should

exclude him from a seat within its body for the 80th Congress by a

majority vote at the time he presents himself to take the oath of office.

A n examination o f the testimony, law, and precedents establishes

that:

I.

The acts and speeches o f Senator Bilbo in his prim ary cam paign

w ere contrary to sound public policy, constituted a known, open, and

notorious violation o f the rights o f Negro citizens and voters o f said

state to register to vote and to vote in said primary, which w ere guar

anteed to them by the Constitution o f the United States, and his open,

notorious and persistent incitement and exhortations to the white citi

zens o f Mississippi to resort to fraud and coercion to deny and deprive

Negro citizens and voters o f Mississippi o f their right to register and

vote in said prim ary so guaranteed them by the Constitution o f the

United States, constitute conduct contrary to sound public policy,

harm ful to the dignity and honor o f the Senate, dangerous to the

perpetuity o f free governm ent and taints with fraud and corruption

the credentials for a seat in the Senate presented by Senator-elect

Bilbo.

II.

The primary election on July 2, 1946, by which Senator-elect Bilbo

was chosen the candidate o f the Dem ocratic Party in Mississippi for

the position o f United States Senator from Mississippi, was not a free

election, but was so thoroughly corrupted by fraud and violence induced

or fom ented by the candidate, Senator-elect Bilbo, that it must be

disregarded and any nomination based thereon held void.

5

The nomination o f Senator-elect Bilbo and the placing o f his name

on the ballot in the Mississippi general election Novem ber 5, 1946, as

a candidate o f the Dem ocratic Party in Mississippi, fo r the position o f

United States Senator, is void because although Senator Bilbo received

a m ajority o f the votes actually cast in the prim ary election o f July 2,

1946, he did not receive a m ajority o f the votes actually cast plus those

votes which otherwise w ould law fully have been cast except for fraud,

violence and corruption to w hich he was privy and which he coun

tenanced and encouraged.

Jurisdiction

The jurisdiction of the Special Committee to Investigate Sena

torial Campaign Expenditures, 1946, rests in Senate Resolution No.

224 as representative of the full body of the United States Senate.

The jurisdiction of the United States Senate in the instant case is

derived from Article I, Section 5, Clause 1, of the United States Consti

tution, providing that “ each House shall be the judge of the elections,

returns, and qualifications of its own members. ’ ’ This provision consti

tutes each House of Congress the sole and exclusive judge of the elec

tions and qualifications of its own members and deprives the courts of

jurisdiction to determine those matters.1 Senatorial precedents, par

ticularly those established in the cases of Senator-elect Prank L. Smith

of Illinois, Senator-elect William S. Vare of Pennsylvania and others

hereinafter cited, recognize the jurisdiction of the Senate to take the

action requested in this brief.

Statement of Facts

The background against which Senator-elect Bilbo conducted his

primary campaign and the political climate in which he made his exhor

tations to the people of Mississippi must be understood for a correct

appraisal of the gravity of his actions.

1 Barry v. United States, 279 U. S. 597; Kilbourn v. Thompson, 103 U. S. 68.

See also: 107 A. L. R. 206.

III.

6

Mississippi is the state with the largest Negro population in pro

portion to the white population. Statewide it is within a few thousand

of the total white population. In some counties there is a large pre

ponderant Negro population (Transcript, p. 765). This has caused

white Mississippians to have a morbid fear of Negro political domi

nation.

In 1890 Mississippi amended its state constitution for the purpose

of establishing white political domination over the Negro.

“ Purposely that amendment was written by Senator George

and adopted by the legislature in 1890, as they were trying to

escape reconstruction and what had been wreaked upon the

people in the South through a war-crazed gang in Washington

that adopted the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, to use

that as a means to eliminate the Negro from the polls.” (Bilbo,

p. 780).

From 1890 to 1946 the white people had the Democratic primary

elections in Mississippi to themselves; there was no effective party of

opposition and nomination in the primary was tantamount to election.

(Testimony of T. B. Wilson, p. 21, Percey Greene, p. 54, Reverend Stan

ley R. Brav, p. 98, E. R. Sanders, p. 619, Ben Cameron, p. 813, Bilbo,

pp. 731, 754.)

Although Senator-elect Bilbo had to face four opponents in the

primary election, not a vote was cast against him in the general elec

tion November 5, 1946 (p. 731).

In 1944 the United States Supreme Court decided the Texas pri

mary case, Smith v. Allwright (321 U. S. 649); in 1946 the United States

Circuit Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit, decided the Georgia primary

case, King v. Chapman (154 F. (2d) 460). Both cases decided that

qualified Negro voters could not be barred from a primary election

which was under substantial state regulation and an integral part of

the election process. The cases were officially considered by the State

Democratic Executive Committee in Mississippi to determine whether

it would thereafter be possible to continue to bar all Negroes from the

7

Mississippi Democratic primaries. The State Democratic Executive

Committee decided that thereafter the Negro had a legal right to vote

in the Mississippi Democratic primaries, but that it did not want him

to vote. This decision was reached before Senator Bilbo began his

active primary campaign, and is a vital part of the background against

which he campaigned. (Testimony of George Butler, member State

Democratic Executive Committee, pp. 823-830.)

In 1946 Mississippi passed a law exempting veterans from pay

ment of poll taxes under certain conditions. A great movement of

Negro veterans to register took place all over the state; aided by per

sons interested in making the base of Mississippi elections more rep

resentative of the people and of raising the Negro to first class citizen

ship. There were 66,972 discharged Negro veterans in Mississippi,

and practically 100% of them could read and write. (See statistics and

discussion by Committee, pp. 491-493.)

Negroes organized a state wide voters league with local chapters.

For the first time since 1890 the white people of Mississippi saw a

substantial threat to their exclusive control of the Democratic primary.

Senator Bilbo further knew that because of his past Negro-baiting and

insulting conduct Negroes would vote against him, and that a sub

stantial Negro vote would be sufficient to throw the primary election

against him. Senator Bilbo was on the spot. It was against this back

ground, in this political climate and with the certain knowledge that

unless he eliminated the Negro voter from the primary election July 2,

1946 his political career was ended, that he conducted a studied, per

sistent and unrestrained campaign to eliminate the Negro voter from

the primary.

Senator Bilbo at the hearings did not deny the substance of the

newspaper reports and other charges against him of advocating the

suppression of the Negro vote in the primary, except to deny that he

had advocated the use of violence or illegal means. He admitted that

if he could have “ legally” prevented it not one Negro would have voted

in the primary (p. 777), that he advocated persuasion to keep the Negro

from the polls and that the best way to do it was to visit the Negro

the night before the election (p. 784); that he might be guilty of sug

gesting heroic treatment of certain people (p. 789) and riding them

out of town on a rail (p. 769) because the white people of Mississippi

were sitting on a volcano (p. 770). He admits he exhorted red-blooded

white men to protect Mississippi from political control by Negroes,

but denies he advocated the use of other than lawful means (p. 747). It

is significant that the uniform reports of the press and the testimony

of the complaining witnesses uniformly fail anywhere to show that

the Senator limited himself at any time to “ lawful means” .

Senator Bilbo filed the script of his last radio talk just before the

primary to prove he advocated “ lawful means” only. The fact the

script contains such a passage is no proof that in the heat of his speech

he actually used the phrase or so limited himself. Significantly enough

the Senator does not testify that he followed the speech verbatim, and

nobody in the record testified he knew that the Senator limited him

self always to advocacy of “ lawful means” . A few defense witnesses

said they had not heard him advocate violence or said they felt he would

not do so; but that is all.

The Committee witnesses testified that Senator Bilbo advocated

open defiance of the United States Supreme Court decision in Smith

v. Allwright (Collier, p. 420); appealed to local officials to keep the

Negro away from the polls (Wilson, p. 325); advised registration clerks

to disqualify them by trick questions on the constitution (Bender, p.

160; Dickey, p. 344); advised the election officials not to count Negro

ballots but to put them aside in envelops (Jones, p. 186); promised

to defend any white person who got in trouble for keeping a Negro

from voting (Wilson, p. 15; Bender, p. 160), and assured the white

people they would be safe from conviction since they would have to be

tried before a white judge and a white jury (Bender, p. 160; Parham,

p. 258; Bilbo, p. 764). He called the spectacle of Negroes voting in

substantial numbers in the Gulfport municipal election June 4, 1946,

a damnable exhibition of demagoguery (Strype, p. 301), and stated

that Negroes were just 150 years from cannibalism (Hightower, p.

712). Senator Bilbo admits he urged Negroes to stay away from the

polls (p. 767).

9

The record refutes the view of certain members of the Committee

that Senator Bilbo’s speeches had no effect on the white population and

the potential Negro voters. “ But this year that opposition was in

creased, in this special election that opposition was increased, it was

intensified. . . . On account of the people were afraid that Mr. Bilbo’s

advices to the white people to refuse to register them, and the people

knew, knowing the people as they do, they thought that they would

take that instruction not to register them, and they found they were

doing that to some extent, and they feared to go.” (Wilson, p. 19).

“ I heard the speeches and saw them in the press releases, and I felt

some of the fear that I think was engendered by the speeches.” (Greene,

p. 39). Reverend Bender testified he heard Negroes in all parts of the

state express themselves as afraid to register or vote because of Senator

Bilbo’s speeches (p. 163). Witness after witness testified that Senator

Bilbo’s speeches intimidated the Negro voters (Spates, p. 189; Wolfe,

p. 208; Reed, p. 217; Strype, p. 300; Dickey, p. 350; Love, p. 489; Eiland,

p. 519; Franklin, p. 633). “ I stated that because of broadcasts and the

newsj there were a number who were afraid to vote. . . . I am referring

to Senator Bilbo’s campaign speeches.” (Moore, pp. 232-233).

Witnesses further testified that his speeches stirred up the white

people. “ I had several white friends in Grenada that said they didn’t

appreciate the speeches coming from Senator Bilbo, that it was accumu

lating hatred between the Negro and the white man in the State of Mis

sissippi.” (Hightower, p. 710; see also: Collins, pp. 530-538; Wilson,

p. 561.) Emmett E. Reynolds, Circuit Clerk, Louisville, testified con

cerning Senator Bilbo’s speeches: “ Well, of course, it didn’t do me

any good to hear those things.” (p. 381). One of the witnesses called

by Senator Bilbo himself testified: “ I think the statements attributed

to Senator Bilbo were for the purpose of getting the unthinking white

men to vote for him . . . Well, a man that would vote for him on some

matter of prejudice rather than policy or something of that sort.”

(Creekmore, pp. 820-821).

In a state-wide political campaign it is impossible to explore the

mind of each individual voter or citizen, but the fact that so many

10

Negroes and white people would volunteer to come at their own expense,

without the protection of subpoena, to testify to the general state of

intimidation and fear caused by Senator Bilbo’s speeches—realizing

they had to return to their home communities and face the officials they

testified against—shows that if the Committee had been as energetic

and solicitous in using its subpoena power to produce testimony against

the Senator as it was solicitous in producing or trying to produce testi

mony for him, the record would have shown the full extent of the intimi

dation and terror caused by Senator Bilbo’s campaign speeches.

As it was the witnesses who did appear represent a true sampling

of the various sections of the state: *

Father Strype, Pass Christian (S. E. Mississippi)

Dickey, McComb (S. W. Mississippi)

Love, Gulfport (S. E. Mississippi)

Eiland, Louisville (E. Central Mississippi)

Franklin, Tougaloo (Central Mississippi)

Hightower, Grenada (N. Central Mississippi)

Collins, Greenwood (N. W. Mississippi)

Clark Wilson, Greenwood

Reynolds, Louisville

Creekmore, Jackson (Central Mississippi)

Spates, Jackson

Wolfe, Jackson

Reed, Jackson

No serious attempt was made to deny wholesale fraud and intimi

dation of Negro voters in the registration and voting in the July 2, 1948

primary, both by officials and by white private citizens.

Qualified Negro voters were denied registration by triekey, catch

questions put to them by the Circuit Clerks (McComb, N. Lewis, p. 269;

M. Lewis, p. 320; Greenville, Brown, p. 134; Body, p. 139; Myles, pp.

146-147; Tylertown, Dillon, p. 608). The Circuit Clerk took the stand

and admitted they put questions to Negroes which they did not put to

white, and made it harder for Negroes to register than white (Cocke,

p. 365, Holmes, p. 395). The Circuit Clerks would procrastinate and

* See : Appendix A.

11

delay registration of Negroes (Dowdy, p. 137; Gladney, p. 451; Eiland,

p. 515; Hamm, p. 696). Negroes were prevented from registering by

threats of violence from peace officers (Lewis, p. 238).

At the polls Negroes were challenged on the ground they had not

been affiliated with the Democratic party for two years, whereas the

Mississippi statute, sec. 3129, Miss. Code, 1930, merely requires “ with

in” two years (Affidavit, Junkin, election manager, p. 646). Negroes

were assaulted at the polls by peace officers (Bender, p. 159; Daniels,

pp. 282-287; Williams, p. 506). Peace officers refused to protect

Negroes at the polls when others assaulted them (Collier, p. 412).

Election officials refused to let Negroes deposit their ballots in the

ballot box, without stating the ground of challenge except that all Negro

ballots were to be placed in envelops—exactly what Senator Bilbo had

instructed (Lovelady, p. 109, Hodges, p. 117, Hunter, p. 124; Jones, p.

183, Harris, p. 222, Wilson, p. 222, Knott, p. 222).

Instead of officials upholding the rights of qualified Negroes to

vote and giving them protection, they uniformly advised Negroes to

surrender their rights to register and vote “ to avoid trouble” (Hathorn,

p. 102, Parham, p. 248, Reynolds, p. 377, Moore, pp. 402, 407, Collins, p.

527, Moore, p. 597, Raiford, p. 613, Hightower, p. 707, Bostick, p. 719).

In some places, the officials themselves just flatly refused to let any

Negro vote (e. g., Pass Christian,—Strype, pp. 295, et seq., Guyot, p.

309, Roberts, p. 313, Garriga, p. 649).

White private citizens, with the certain knowledge and advice of

Senator Bilbo that they were safe from conviction, added their share

of intimidation and violence to keep Negroes from registering and

voting (Fletcher, pp. 56, 81; Hathorn, p. 102; Bender, p. 158; Parham,

pp. 247, 250; Collier, p. 412; Prichard, p. 582). They joined with officials

or acted alone in advocating and advising Negroes not to exercise their

rights to ‘register and vote in the primary “ to avoid trouble” (Collins,

p. 527, Steele, p. 558; see also Dickey, p. 346, Parham, p. 257).

12

It apparently never penetrated the consciousness of Senator Bilbo,

any Mississippi official or white citizen working with them that the

guarantee of a rule of law and order lies in upholding legal rights, not

in surrendering them. Once again those witnesses testifying to sup

pression, fraud and violence come from all sections of the State, show

ing the conditions were not localized but were state wide.

Mississippi law requires that where a candidate does not receive

a majority of the votes cast in the primary he shall enter a run-off

primary even if he otherwise leads the field (Miss. Code, 1930, sees.

3109 et seq.). Senator Bilbo merely claims a primary majority of

3,834 votes, but when the large Negro population and 66,972 discharged

Negro veterans in Mississippi are considered it is plain his majority

vanishes.*

“ Of course, I knew they were going to vote against me

because they were being organized and led to the polls by the

C. I. O.-P. A. C. and all this Communistic bunch, men like Bloch

yonder. The C. I. 0. had representatives here in the hotels

throughout the campaign. They put up the money in the cam

paign. They helped to organized and all that. They were mess

ing with the nigger. . ; . No, sir, I didn’t want any of them to

vote. . . . Would you want somebody to vote that you knew was

going to vote against you.” (Bilbo, pp. 782-783).

We submit that the testimony shows a state-wide condition of in

timidation not merely of individual Negroes, but of large blocks of

Negroes (e. g. Pass Christian, p. 297; Jackson, p. 42; Greenwood, pp.

538-539; Holly Springs, p. 675; Grenada, p. 723).

“ The only other thing I did was to ask them to read the

section of the Constitution of the State of Mississippi where it

explains the election of the Governor of the State of Mississippi.

I did not require that of the whites, but I did require it of the

* W e further challenge the election of Senator Bilbo on the ground that at the

minimum he should have been thrown into a run-off primary under Mississippi law

on the ground that he did not have a true majority of the votes cast at the primary

election and of the votes which lawfully would have been cast therein except for

fraud and coercion induced and fomented by him.

13

colored. . . . I have no other reason than that they were col-

; ored. . . . As I said a little while ago to this gentleman (indi

cating the Chairman) we want the primaries white and anything

that will make it a little bit harder for the colored man to become

a voter, that is the way I look at it.” (Clifford R. Field, Circuit

Clerk of Adams County, Natchez, pp. 731, 739).

Leaving out the inherent vice of the primary election as a con

trolled, restricted election, the facts conclusively demonstrate that

Senator Bilbo did not receive the nomination by an expression of a

majority of the qualified Democratic voters of Mississippi, through the

primary held July 2, 1946, and that under Mississippi law he was

improperly on the ticket in the general election November 5, 1946, and

that his election is therefore irregular and void.

I.

The Right of Negroes to Vote in Primary Elections Was

Wei! Established Prior to the Campaign of

Senator-elect Bilbo

The United States is a constitutional democracy. Its organic law

grants to all citizens a right to participate in the choice of elected

officials without restriction because of race. The right of citizens not

to be discriminated against because of race in voting at general elec

tions has never been questioned since the adoption of the 15th Amend

ment. The right of citizens to register and qualify as electors without

distinction as to race or color has been firmly established in the cases

of Lane v. Wilson1 and Guinn v. United States,1 2 It is therefore clear

that the right to vote in the election of federal officers and the right to

do so without distinction as to race or color are rights grounded in the

federal Constitution. These rights protected by the federal Consti

1 307 U. S. 268.

2 238 U. S. 347.

14

tution extend to each and every step of the electoral process and em

brace primary as well as general elections.8 As the United States

Supreme Court said in the case of United States v. Classic:

“ Where the state law has made the primary an integral part

of the procedure of choice, or where in fact the primary effec

tively controls the choice, the right of the elector to have his

ballot counted at the primary, is likewise included in the right

protected by Article I, Section 2. And this right of participation

is protected just as is the right to vote at the election, where the

primary is by law made an integral part of the election ma

chinery, whether the voter exercises his right in a party primary

which invariably, sometimes or never determines the ultimate

choice of the representative. ’ ’

Prior to the primary campaign of Senator-elect Bilbo, the right

of Negroes to vote in such primary had been clearly established. In

the case of Smith v. Allwright, the United States Supreme Court recog

nized the right of Negro electors to vote in primary elections in states

where the primary is an integral part of the election machinery of the

state. This principle was re-emphasized in the case of King v. Chap

man.1'

A. In Mississippi the Primary Is by Law an Integral

Part of the Election Machinery

The Constitution and statutes of Mississippi affecting and control

ling the conduct of primary elections in that state are of such an all-

inclusive nature that party primaries are clearly an integral part of the

election machinery of that state.

Article XII, Section 248 of the Constitution of Mississippi pro

vides: “ The legislature shall enact laws to secure fairness in party

primary elections, conventions, or other methods of naming party

candidates.” In interpreting this constitutional provision it was held 3 4

3 Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649; United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299.

4 154 F. (2d) 460 (C. C. A. 5th, decided March 6, 1946).

15

that it authorizes the nomination of public officers by primary election

exclusively.5

Article XII, Section 249 of the Constitution of Mississippi pro

vides: “ . . . registration under the Constitution and laws of this state

by the proper officers of this state is hereby declared to be an essential

and necessary qualification to vote at any and all elections.”

Pursuant to the constitutional requirement contained in Section

247, the Mississippi State Legislature enacted an entire chapter of the

Code, devoted solely to primary elections. (Title 14, Chapter 1, Sec.

3105-3203-Miss. Code-1942.) These statutes control every conceiv

able phase in the operation of a party primary in the state. In Section

3105, the following language can be found: “ All primary elections

shall be governed and regulated by election laws of the state in force

at the time the primary election is held . . . ” Thus, in the statute,

there appears the clear intent of the state to make party primaries an

integral part of its election machinery.

The statutes affecting and governing primary elections run the

gamut of control from modes of nominating state, district, and other

officers (3105), dates of primaries (3110, 3111) as amended by Laws

of 1944 (ch. 173), manner of recording registrants (3112, 3113, 3114),

form of ballot (3124), ballot boxes (3126), voting hours (3164), to poll

tax exemptions (3199).6 The clear cumulative effect is to bring the

Democratic Party primary in Mississippi into the election machinery

of the state.

B. Primary in Mississippi Effectively Controls

Choice of Officers

The primary in Mississippi not only meets the above test, as set

forth in the Classic and Alhvright cases, but also meets the alternative

test in that it “ effectively controls the choice of officers.”

5 Mclnnis v. Thames, 80 Miss. 617, 32 So. 286.

6 Sections referred to are from the Mississippi Code.

16

The candidate who is successful in the party’s primary is assured

of victory at the general election for two reasons: (1) an unsuccessful

primary candidate may not be a candidate in the general election on

his party’s ballot (Op. Atty. Gen. 1931-33, p. 37), Ruhr v. Cowan, 146

Miss. 870, 112 So. 386; and, (2) the only candidates who may run at

the general election are those nominated in the preceding primary

(Tit. 14, Chap. 1, Sec. 3111 and 3156 Miss. Code).

No party other than the Democratic Party has held an organized,

state-wide primary in Mississippi for the last 56 years. Since 1892,

the Democratic nominees for United States Senator, Eepresentative in

Congress, Governor and other state officers nominated at these pri

maries have been elected at ensuing general elections. For all intents

and purposes there is but one party in Mississippi—the Democratic

Party (E. 793ff).

This fact has become so apparent to qualified electors of Missis

sippi that interest in the general election is practically non-existent

(E. 21, 54, 98, 813). The complete control over the choice of officers

that is held by the Democratic Primary in Mississippi can best be illus

trated by owrds of Senator Bilbo, in discussing the general election:

“ It wasn’t necessary for anybody to go. As a matter of fact, I didn’t

have any opponent. I could have just gone and voted for myself and

been elected.”

It is apparent, therefore, that under both of the alternatives set

forth in the Classic and Allwright cases the right to vote in the primary

in Mississippi without discrimination because of race or color is pro

tected by the federal Constitution. In other words, there cannot be a

lawful “ white Democratic Primary” in Mississippi as alleged by Sena

tor Bilbo (see testimony, E. 729ff).

Prior to the primary campaign of Senator-elect Bilbo, the right of

Negroes to vote in the primary was not only well established at law,

but was recognized by officials of Mississippi, including the State Demo

cratic Executive Committee. A special committee of the State Demo

cratic Executive Committee, after careful consideration of the prece

dents cited above, concluded that Negroes had the right to vote in the

17

primary elections (E. p. 826). This decision of the State Democratic

Executive Committee was made before Senator-elect Bilbo began his

active campaign (E. p. 830).

II.

Use of Force or Intimidation to Prevent Negroes

from Registering for and Voting in Democratic

Primaries in Mississippi Is Sufficient to Invalidate

Election of Senator-elect Bilbo

State courts have clearly established the principle that where quali

fied electors, sufficient in number to have changed the result of the

election, were corruptly and fraudulently deprived of an opportunity

to vote, the election is void.1

The true effect of intimidation and violence upon elections has been

set forth as follows: “ It is the essence of free elections that the right

of suffrage should be exercised without coercion or the deterrent of

any intimidation or influence. An election will be set aside, or the

returns from a particular precinct rejected, on the grounds of threats,

intimidation or violence, when the threats, intimidation or violence

change the result or render it impossible to ascertain the true result

with certainty, but threats, violence or disturbances not materially

affecting the result will not invalidate an election. Some authorities hold

that if the progress of the election was not in fact arrested, there must

have been such a display of force as ought to have intimidated men of

ordinary firmness, but according to other authorities, the general rule

applies regardless of the personal courage of the voters deterred.

While a threat must be serious, citizens are not bound to fight their

way to the polls. Threats or intimidation exist where there is a putting

in fear; and there may be a moral intimidation independent of threats

or violence or physical injury . . . . ” 1 2

1 Montova v. Ortiz, 24 N. M. 616; Snyder v. Blake, 35 Okl. 294: Martin v.

McGarr, 27 Okl. 653.

2 29 C. J. S. (Elections) Sec. 220, p. 323.

18

This is particularly true where the deterrent to the free exercise

of the ballot is directed against members of a class. Thus a referendum

held in the City of Des Moines was declared null and void where the

denial of the right to vote was directed at all women as such and where

this denial was widely publicized in the press and in discussions in

women’s organizations with the result that only three women presented

themselves to vote. There the Iowa Supreme Court stated:

‘ ‘ The distinction must be kept in mind between depriving the

individual of the ballot because of some disqualification peculiar

to himself and the denial thereof to an entire class of voters.” 3

While the court recognized no remedy in the former case, the court

stated that in the latter case if the class is numerous enough to have

changed the result, a remedy exists.

“ The denial is then in the nature of oppression and operates

to defeat the very purpose of the election.” 4

A similar decision was rendered by the Superior Court of Warren

County, Ga., where municipal elections were declared void when held

under a local law limiting voting to white citizens, upon a showing that

there existed in the town persons of color qualified to vote in numbers

sufficient to have changed the result of the election.5 In a recent case

decided in 1941, by a District Court of Appeals in California, it was

determined that the vote on a bond issue in a school district must be

declared void where threats and intimidation were applied to third

persons in order to prevent qualified voters from voting and thus

deterred qualified voters from the free exercise of the franchise in suf

ficient numbers to affect the outcome of the election. The court found

that the coercion while applied to third persons “ was equally effective

in accomplishing its intended purpose as though it had been directly

3 Coggeshall v. City of Des Moines, 138 Iowa 730.

4 Ibid.

5 Howell v. Pate, 119 Ga. 537.

19

applied to the qualified electors who failed to vote.” 6 Early decisions in

courts of many states have established that:

“ An election to be free must be without coercion of every

description. An election may be held in strict accordance with

every legal requirement, yet if in point of fact the voter casts

the ballot as the result of intimidation; if he is deterred from

the exercise of his free will by means of any intimidation what

ever, although there be neither violence nor physical coercion, it

is not a free and equal election within the spirit of the consti

tution. ’ ’ 7

Precedents established by the courts of last appeal of many states

have thus established the principle that any deterrent of the free exer

cise of the ballot which affects a sufficient number of voters to change

the result of the election had they voted for the next highest candidate

render the election void regardless of the responsibility for such activi

ties. 8

The Senate of the United States can have no lower standards for

judging the validity of the elections which furnish the basis for the

credentials presented by a Senator than are used by the States for

judging the validity of elections of state officials.

The acts and speeches of Senator Bilbo and his open and persistent

incitement and exhortations to the white citizens of Mississippi to

resort to fraud and coercion to deprive Negroes of their right to vote

effectively prevented large numbers of Negroes from registering and

6 Williams v. Venneman, 42 Cal. App. (2d) 618.

7 DeWalt v. Bartley, 146 Pa. St. 529.

8 Inmates of an asylum refused, they being of sufficient number to change elec

tion result; Renner v. Bennett, 21 Ohio St. 431.

Polls closed early on improper notice of election voided election in following

cases: Barry v. Lauch, 5 Coldw. 588, Newcum v. Kirtley, 113 B. Mon. 515; Re

Johnson, 40 U. C. Q. B. 297; Woodward v. Sarsons, L. R. 10 C. P. 733 (Parlia

mentary election).

Failure to provide opportunity to persons qualified to register voided election

where group denied was materially large enough to affect result, McDowell v. Mass.

& S. Constr. Co., 96 N. C. 514, 2 S. E. 351; State ex rel. Harris v. Scarborough,

110 N. C. 232, 14 S. E. 737.

20

voting. The transcript of testimony of the hearings in this inquiry

is replete with testimony of actions of violence, intimidation and coer

cion induced or fomented by Senator Bilbo. Negro voters in suf

ficient number to have deprived Senator Bilbo of the majority of votes

necessary for nomination at the first primary were thereby prevented

from voting.

III.

The Authority of the Senate to Exclude Senator-elect

Theodore G. Bilbo from a Seat in the Senate of the 80th

Congress at the Time He Presents Himself to Take the

Oath of Office Is Clear Under the Senate’s Constitutional

Power and Precedents Established in Prior Cases

The jurisdiction of the United States Senate is derived from

Article I, Section 5, Clause 1 of the United States Constitution, pro

viding that “ Each House shall be the Judge of the Elections, Returns

and Qualifications of its own members.” This provision constitutes

each House of Congress the sole and exclusive judge of the elections

and qualifications of its own members and deprives the Courts of juris

diction to determine those matters.1 This constitutional grant of power

to the Senate is interpreted to mean that even though a Senator-elect

possesses all of the qualifications set out in Article I, Section 3, Clause

3 of the Constitution,1 2 the Senate may “ judge” him disqualified to sit

1 Barry v. United States, 279 U. S. 597; Kilbourne v. Thompson, 103 U. S.

68. See also: 107 A. L. R. 206.

2 “ No person shall be a Senator who shall not have attained to the age of 30

years and been 9 years a citizen of the United States and who shall not when

elected be an inhabitant of that state for which he shall be chosen.”

21

within its body and declare his seat vacant because of acts or conduct

which “ taint” his credentials with fraud or corruption.3

In the cases of Senators-elect Frank L. Smith of Illinois and

William S. Vare of Pennsylvania, it was squarely held that corrupt

actions amounting to implicit or implied bribery by a Senator-elect or

such action done with his knowledge or encouragement, which did not

actually affect the result of the elections, may still affect the validity

thereof, thereby furnishing grounds for exclusion from a seat in the

Senate by a majority vote.4 These cases also squarely settled the right

of the Senate to consider acts which corrupt only the Primary election

as sufficient to come within their power to “ judge the elections and

returns” of their members.

On the 17th day of May, 1926, the Senate of the 69th Congress

appointed a special committee to investigate and report on campaign

expenditures, promises, etc., made to influence the nomination of any

person as a candidate or to promote the election of any person as a

member of the Senate at the general election to be held in November

1926. This committee, pursuant to the resolution, investigated the

campaigns of Frank L. Smith of Illinois and William S. Vare of Penn

sylvania.

The investigation in Illinois showed that Senator-elect Frank L.

Smith had expended over $450,000 in his 1926 primary campaign. It

further showed that over $200,000 of this money had come from utility

companies under the control of the Illinois Commerce Commission, of

3 Prior cases in which exclusion was based upon this principle: Phillip F.

Thomas, Senator-elect from Maryland, 40th Congress, charged with disloyalty in

that he gave his son $100 and his blessing when he went off to fight for the Con

federacy.— Excluded (Senate Election Cases, 1879-1903, Taft, Furber and Buck,

pp. 333-339; Cong. Globe, pt. 2, 40th Cong., 2nd Sess., pp. 1260-1271; Feb. 19, 1868.

ITinds Precedents, Vol. 1, pp. 466-470).

B. F. Whittemore, House of Rep., 1870, found guilty of selling a cadetship,

resigned to escape expulsion; was re-elected and was excluded when he attempted

to return. (Hinds Precedents, Vol. 1, p. 47).

Brigham Roberts, House of Rep., an admitted polygamist from Utah, excluded

(53 Cong., Jan. 20, 1900, Hinds Precedents, Vol. 1, Section 447, p. 529, et seq.).

4 This issue had never been squarely settled before. See: Appendix B.

22

which Smith was a member, and that the receipt and granting of such

money constituted a misdemeanor under Illinois statutes.

Its investigation in Pennsylvania showed numerous instances of

fraud and corruption in behalf of the candidacy of William S. Yare.

It further showed that there had been expended in his behalf at the

primary election a sum exceeding $785,000.

The committee presented these facts in its final report to the Senate

of the United States.

On the 5th day of December, 1927, the opening day of the 70th

Congress, Senator-elect Smith, having previously filed his certificate

of election, appeared with Senator-elect Yare and others to take the

oath of office. At this point, Senator Norris presented Senate Resolu

tion No. 1, which recited the previous appointment of the special com

mittee by the 69th Congress, the facts about the receipt and expendi

ture of money by Smith theretofore filed with the Senate, and concluded

with the following clauses:

“ Resolved, That the acceptance and expenditure of the vari

ous sums of money aforesaid in behalf of the candidacy of the

said F ran k L. S m it h is contrary to sound public policy, harmful

to the dignity and honor of the Senate, dangerous to the per

petuity of free government, and taints with fraud and corruption

the credentials for a seat in the Senate presented by the said

F ran k L. S m it h ; and be it further

“ Resolved, That the said F ran k L. S m it h , is not entitled

to membership in the Senate of the United States.” 5

The exact procedure on the same day was followed in connection

with the case of Senator-elect Vare.

On December 6, 1927, Senator Norris, in support of his resolution,

said:

“ The question as to whether Mr. S m it h and Mr. Y are should

be seated pending the decision of the question as to whether 6

6 70th Cong., 1st Sess., Cong. Rec., vol. 69, pt. 1, p. 3.

23

they will be allowed to remain here permanently is another point

involved. It is true that in ordinary cases a Senator is sworn

in upon the presentation of his certificate of the election and,

if his right to a seat here is then contested, he remains in the

Senate as a Member until that question is finally determined

by the Senate. That procedure is followed because, in the ordi

nary case, the only official evidence that the Senate has of the

election or the qualifications of one claiming the right to be a

Member of the Senate is the certificate of election. No other

evidence of an official kind is ordinarily in the possession of the

Senate, and hence, when the Senate is called upon to act, either

to permit or to refuse to permit the applicant to take the oath

of office, there is no evidence except the certificate of election.

It, as everyone knows, is only prima facie evidence of the facts

which it purports to state.

“ In the case of Mr. S m it h and Mr. V are an entirely different

proposition confronts the Senate. The Senate has appointed its

committee and directed it to make an investigation, and in obedi

ence to the commands of the Senate, the committee has gone

into Illinois and Pennsylvania and made an investigation.

“ The committee has reported the results of its investigation

to the Senate. It has submitted to the Senate the sworn testi

mony taken in this investigation and, therefore, the Senate is

now, and has been for many months, in possession of the official

information contained in the report of the committee and the

evidence which it has taken. Therefore at the very threshold

the certificates of election of these men are challenged by this

report and this evidence. It is worthy of note, also, that both

Mr. Vare and Mr. Smith appeared in person before this com

mittee and testified, and that the facts reported by the committee

stand practically uncontradicted.

“ Taking this evidence and the report of the committee upon

its face value, it absolutely annihilates the presumption in favor

of the certificates of election. It brings both cases clearly wdthin

the rule laid down by the Senate in the Newberry case, and if

the Senate still adheres to that rule and desires to enforce the

principle of government therein enunciated it will refuse to per

mit either of these gentlemen to be seated.” 8 6

6 70th Cong., 1st Sess., Cong. Rec., vol. 69, pt. 1, p. 122.

24

Senator .Deneen then offered to amend the Norris resolution to

the effect that Frank L. Smith is entitled to be sworn in as a member

of the Senate upon his prima, facie case.7 This amendment was de

feated.

Thereafter, the Norris resolution, still denying Smith the right to

the oath, but, having been amended to afford him a further right to be

heard and the privilege of the floor to answer in his own defense, when

the matter came up for final Senate action, on December 7, 1927, was

carried.8

On January 17, 1928, the committee reported that “ Smith was not

entitled to take the oath of office and is not entitled to membership . . .

and that a vacancy exists . . . . ” Thereafter, on January 19, 1928,

after extensive debate the Senate adopted the following resolution and

preamble:

“ Whereas on the 17th day of May, 1926, the Senate passed

a resolution creating a special committee to investigate and de

termine the improper use of money to promote the nomination

or election of persons to the United States Senate, and the em

ployment of certain other corrupt and unlawful means to secure

such nomination or election

“ Whereas said committee in the discharge of its duties

notified F ran k L. S m it h , of Illinois, then a candidate for the

United States Senate from that State, of its proceeding, and the

said F ran k L. S m it h appeared in person and w as permitted to

counsel with and be represented by his attorneys and ag’ents.

“ Whereas the said committee has reported—

“ That the evidence without substantial dispute shows that

there was expended directly or indirectly for and on behalf of

the candidacy of the said F ran k L. S m it h f o r the United States

Senate the sum of $458,782; that all of the above sum except

$171,500 was contributed directly to and received by the personal

agent and representative of the said F ran k L. S m it h with his

full knowledge and consent; and that of the total sum aforesaid

7 70th Cong., 1st Sess., Cong. Rec., vol. 69, pt. 1, p. 160.

8 70th Cong., 1st Sess., Cong. Rec., vol. 69, pt. 1, pp. 161-162.

25

there was contributed by officers of large public-service insti

tutions doing business in the State of Illinois or by said insti-

tions the sum of $203,000, a substantial part of which sum was

contributed by men who were nonresidents of Illinois, but who

were officers of Illinois public-service corporations.

“ That at all of the times aforesaid the said F ran k L. S m it h

was chairman of the Illinois Commerce Commission, and that

said public-service corporations commonly and generally had

business before said commission, and said commission was,

among other things, empowered to regulate the rates, charges,

and business of said corporations.

“ That by the statutes of Illinois it is made a misdemeanor

for any officer or agent of such public-service corporations to

contribute any money to any member of said commission, or for

any member of said commission to accept such moneys upon

penalty of removal from office.

“ T hat said S m it h has in no m anner con troverted the truth

o f the fo re g o in g fa cts , a lthough fu ll and com plete op p ortu n ity

w as g iven to him , not on ly to present evidence but argum ents in

his b e h a lf ; and

“ Whereas the said official report of said committee and the

sworn evidence is now and for many months has been on file with

the Senate, and all of the said facts appear without substantial

dispute; Now therefore be it

“ Resolved, That the acceptance and expenditure of the

various sums of money aforesaid in behalf of the candidacy of

the said F r an k L. S m it h is contrary to sound public policy,

harmful to the dignity and honor of the Senate, dangerous to

the perpetuity of free government, and taints with fraud and

corruption the credentials for a seat in the Senate presented by

the said F ran k L. S m it h ; and be it further

“ Resolved, That the said F ran k L. S m it h is not entitled to

membership in the Senate of the United States, and that a

vacancy exists in the representation of the State of Illinois in

the United States Senate.” 9

9 70th Cong., 1st Sess., Cong. Rec., vol. 69, pt. 2, pp. 1582-1597, 1665-1672,

1703-1718.

26

It is clear from a reading of this resolution that Smith was excluded

from the Senate. He had never been administered the oath nor allowed

to take his seat in the Senate chamber.

The case of Senator-elect Vare, involving even greater primary

expenditures, resulted in the same preliminary procedure in the 70th

Congress and the same reference to the committee for furthr oppor

tunity for Yare to appear in person. However, Vare became fatally ill

before he could avail himself of the opportunity to appear so that the

Senate never had an opportunity to vote a final exclusion resolution.

The Smith and Vare cases recognized the rule that an election is

invalidated by a single act of bribery or corruption participated in,

encouraged or condoned by the Senator-elect, though not affecting the

numerical result.10

Considering the fact that neither the Senate nor its committee in

the Smith case found that the sums of money used by him were used

to purchase votes sufficient to change the result or that a single voter

or worker was bought, bribed or influenced with this money by Smith

or his supporters with his knowledge, expressed or implied, it must be

concluded that the acceptance and expenditure of this money in connec

tion with an election, even a primary election, of itself was an act

“ contrary to sound public policy, harmful to the dignity and the honor

of the Senate, dangerous to the perpetuity of free government and

taints with fraud and corruption the credentials for a seat in the Senate

presented by the said Frank L. Smith. ’ ’

Thus the last word of the Senate construing its right as well as

power to “ judge the elections” of its members not only holds that as

a Senate it has the power to consider acts done in a primary as sufficient

to invalidate the credentials for a seat, but that a new standard, unre

lated to the old rules applicable to bribery and corruption, prevailing

10 See: Appendix B.

27

prior to the adoption of the Seventeenth Amendment, has been estab

lished; namely, that acts which are

“ contrary to sound public policy, harmful to the dignity and

honor of the Senate, dangerous to the perpetuity of free govern

ment . . . ”

affect “ the credentials” presented by the Senator-elect so that the

validity of the election is involved and the Senator-elect can be ex

cluded.11

It happened that in the Smith case the acceptance and expenditure

of vast sums of money in connection with a primary election were the

facts which constituted the prohibited acts, but, if the principle be

sound, and it is, then the principle remains as a living, vital part of

our democratic way of life. Since this is true, then any other or dif

ferent acts, which likewise fall within this prohibition when measured

by sound standards of morality and democratic values, will also meet

the standard.

IV.

The Acts and Conduct of Senator-Elect Theodore G.

Bilbo During his 1946 Democratic Primary Campaign in

the State of Mississippi Clearly Fall Within the Prohibi

tions of the Legislative Rule Established by the Senate

in the Smith and Vare Cases.

When the principles established by the Smith and Vare cases are

applied to the facts set forth in this brief on pages 5 to 13, it is

clear that Senator-elect Bilbo’s actions in the primary election in

Mississippi fall directly within the Smith and Vare cases and he must

therefore be excluded. 11

11 See Senator Borah, supra, and Senator Reed of Pennsylvania in the Vare

case, who offered to stipulate that if Vare was allowed to take the oath, the Senate

clearly had the power, thereafter, to exclude him by a majority vote— (Cong. Rec.,

70th Cong., vol. 69, pt. 1, pp. 298-9, December 9, 1927).

A cts and Conduct “ Opposed to Sound Public Policy”

The American way of life is dedicated to the perfection of a class

less democratic society in which race, creed and national origin are

invalid and irrational criteria. Our government was founded on the

principle that all men are created equal. Our Constitution and our

national institutions are dedicated to the achievement of that concept.

The public policy of the United States condemns discrimination based

on race, creed or color.

History has proved that freedom cannot exist where classifications

and distinctions because of race or color are tolerated. Our govern

ment, in recognition of this historical fact, has long been dedicated to

the achievement of racial and religious freedom, not only in the United

States, but throughout the world. In recognition of this principle,

specific provisions were added to the United States Constitution to pre

vent the erection of distinctions and classifications on the basis of race

or color.

In Strauder v. West Virginia,1 the Supreme Court stated in com

menting upon the purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment:

“ What is this but declaring that the law in the States shall

be the same for the black as for the white, shall stand equal

before the laws of the States, and, in regard to the colored race,

for whose protection the Amendment was primarily designed,

that no discrimination shall be made against them by law because

of their color? The words of the Amendment, it is true, are

prohibitory, but they contain a necessary implication of a posi

tive immunity, or right, most valuable to the colored race—the

right to exemption from unfriendly legislation against them dis

tinctly as colored; exemption from legal discriminations, imply

ing inferiority in civil society, lessening the security of their

enjoyment of the rights which others enjoy, and discriminations

which are steps toward reducing them to the condition of a sub

ject race.”

28

1 100 U. S. 305, 308.

29

In Hirabayashi v. United States,2 3 the late Chief Justice S tone ,

writing the majority opinion, said at page 100:

“ Distinctions between citizens solely because of their an

cestry are by their very nature odious to a free people whose

institutions are founded upon the doctrine of equality. For that

reason, legislative classification or discrimination based on race

alone has often been held to be a denial of equal protection.”

Mr. Justice M u r p h y , concurring, said at pages 110, 111:

“ Distinctions based on color and ancestry are utterly incon

sistent with our traditions and ideals. They are at variance with

the principles for which we are now waging war. We cannot close

our eyes to the fact that for centuries the Old World has been

torn by racial and religious conflicts and has suffered the worst

kind of anguish because of inequality of treatment for different

groups. There was one law for one and a different law for an

other. Nothing is written more firmly into our law than the com

pact of the Plymouth voyagers to have just and equal laws.”

The Senate of the United States has recently ratified and adopted

the Charter of the United Nations which is now a part of our funda

mental law.8 Under its provisions, and specifically by virtue of Article

55(c) thereof, our government is obligated to promote “ uniform respect

for, and the observance of, human rights and fundamnetal freedoms for

all without distinction as to race.” The Senate of the United States

has also ratified the Act of Chapultepec in which this nation, along with

Latin-American nations, undertook “ to prevent . . . all that may per

fect discrimination among individuals because of racial or religious

reasons.”

It is clear, therefore, that the public policy of the United States

is dedicated to the eradication of discrimination against persons or

classes of persons because of race, religion or color. From the facts

2 320 U. S. 81.

3 Article 6, Clause 2, United States Constitution.

Also, Kennett v. Chambers, 14 How. 38.

Also, In the Matter of Drummond Wren, (Ontario Reports, 1945, p. 778).

30

which have been set out in the first part of this brief, it has been clearly

shown that Senator-elect Birbo’s conduct during his recent Primary

campaign was directly opposed to that public policy, and that he advo

cated discriminatory acts against Negro citizens to prevent their par

ticipation in the electoral process in the State of Mississippi.

The A cts and Conduct “ H arm ful to the Dignity

and Honor o f the Senate”

Our nation, as a subscriber to the United Nations Charter and to

the Act of Chapultepec, is under an obligation to do all within its power

to fulfill its obligations thereunder. The responsibility for fulfilling

these obligations rests primarily upon the Senate of the United States,

and it is under a duty at all times to take uncompromising steps to

implement obligations to fellow-signatories of these treaties. If the

Senate should fail to live up to these obligations, its honor and dignity

will be forever besmirched. It is immediately obvious, therefore, that

if the United States is to fulfill its solemn obligations, it must have

sitting in its highest legislative body men who are free of narrow,

biased, racist theories condemned by these documents.

Senator-elect Bilbo exhibited, during his primary campaign of

1946, a blatant and crass disregard for basic rights and fundamental

freedoms of American citizens because of race and color. The honor

and dignity of the Senate requires, therefore, that this body, recog

nizing the harm which would come to it by having Senator-elect Bilbo

again seated in its ranks, must, to preserve this honor, exclude him

from a seat in the Senate of the 80th Congress.

The seating of a person such as Senator-elect Bilbo, who advocates

discrimination and classification because of race and color, will make

the other signatories of the Act of Chapultepec and the United Nations

Charter question the good faith of the Senate in carrying out the obli

gations which it has assumed by its ratification of these documents.

31

The A cts and Conduct “ Dangerous to the

Perpetuity o f Free Government”

We have just recently concluded a life and death struggle with

nations dedicated to the principle of racial superiority. We found

this totalitarian concept so dangerous to our own democractic existence

as to warrant the sacrifice of the lives of thousands of American citi

zens to conclude and eradicate these evil forces.

The Senate, as the senior of our two national legislative bodies

whose members must swear to uphold the Constitution of the United

States and to support a government whose essential character is repub

lican, must not and cannot tolerate the presence in its body of an in

dividual who knowingly and wilfully advocates the evasion and thereby

ultimate destruction of the United States Constitution.

Senator Bilbo has shown by his campaign statements that he does

not believe “ that the right of citizens of the United States to vote . . . ”

should “ . . . not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any

state on account of race, color or previous condition of servitude.”

U. S. Constitution, Am. 15, Sec. 1.

The American republic form of government is based upon and

depends for its continued existence upon the free and untrammeled

exercise of the elective franchise by all of its citizens. If men who sit

in the Senate of the United States do not subscribe to this basic prin

ciple the ultimate result will be the same as though this government

were overthrown by military force. Every republican form of democ

racy is founded upon the right of the free exercise of citizenship in

the casting of the ballot. If this is destroyed or taken away, whatever

be the means, the government fails; because the very fundamental prin

ciples of its establishment is violated and taken away.

“ In a republican government, like ours, where political

power is reposed in representatives of the entire body of the

people, chosen at short intervals by popular elections, the tempta

tions to control these elections by violence and by corruption is

a constant source of danger.

32

“ If the Government of the United States has within its con

stitutional domain no authority to provide against these evils,

if the very sources of power may be poisoned by corruption or

controlled by violence and outrage, without legal restraint, then,

indeed, is the country in danger and its best powers, its highest

purposes, the hopes which it inspires and the love which en

shrines it, are at the mercy of the combinations of those who

respect no right but brute force, on the one hand, and unprin

cipled corruptionists on the other.” 4

The acts and speeches of Senator Bilbo per se without reference to

their traceable effect on white Mississippi voters and on Negro voters,

were so contrary to sound public policy, harmful to the dignity and

honor of the Senate, and dangerous to the perpetuity of fre'e govern

ment, as to taint his credentials with fraud and corruption and to dis

qualify him for a seat in the Senate.

Conclusion

The facts in the record constitute the strongest indictment of

Senator Bilbo. This record is made and will be read all over the world.

Senator Bilbo is on trial before this Committee; but the Senate itself

is on trial before the bar of public opinion. And failure to meet the

issues here presented head on and fairly may yet result in drastic and

most serious consequences to our entire nation in world affairs.

Respectfully submitted,

C harles H . H ouston

T httrgood M arshall

Counsel for the National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People.

R obert L. Carter

M arion W. P erry

F ra n k l in II. W illiam s

of Counsel.

4 Matter of Jasper Yarbrough, 110 U. S. 651 (1883).

33

APPEN D IX A

Analysis o f Transcript o f Testimony

I. No. of W itnesses at H earings— 102.

Complainants— 69.

Defense— 33.

II. Geographical D istribution :

Jackson, Hinds County

# 1 T. B. Wilson

# 2 Percy Green

qfjfc 10 Plerman L. Caston

# 1 5 Lee Ernest Butler

# 1 8 Quintus Jones

# 1 9 Frank J. Spates

# 2 0 Potts Johnson

# 2 1 Walter Johnson

# 2 2 Edison D. Johnson

# 2 3 Henry C. W olfe

# 2 4 Eddie P. Anderson

# 2 5 Elesha Reed, Jr.

# 2 6 Louis Miles

# 3 0 Benjamin H. Taylor

# 3 1 Willis L. Moore

Meridian, Lauderdale County

# 7 Samuel J. Loodody

# 8 Nathan Hodges, Jr.

# 9 James W . Hunter, Sr.

# 2 7 James Harns

# 2 8 Leon Wilson

# 2 9 Edward Knott, Jr.

Tougaloo, Hinds County

# 7 4 Arthur E. Franklin

McComb, Pike County

# 3 2 Napoleon B. Lewis

# 3 4 Joe Parham

# 3 5 Nathaniel H. Lewis

# 3 6 Samuel B. O ’Neal

# 4 2 Meredith Lewis

# 4 3 Lawrence Wilson

# 4 5 S. J. Dickey

Bay St. Louis, Hancock County

# 4 1 John James

Holly Springs, Marshall County

# 8 0 Samuel K. Phillips

# 8 4 Joe Bell •

Crystal Springs, Copiah County

# 5 3 L. J. Sibbie

Edwards, Hinds County

# 5 5 Charles Clent Mosley, Jr.

Tylertown, Walthall County

# 5 6 A. G. Price

# 6 9 Benton Simmons

# 7 0 Timothy Dillon

# 7 1 J. B. Raiford

Grenada, Grenada County

# 8 5 Walter Hightower

# 8 6 R. S. Bostick

Puckett, Rankin County

# 3 Stoy Fletcher

Vicksburg, Warren County

# 5 Rev. Stanley R. Brav

Greenville, Washington County

# 1 1 Willie Douglass Brown

# 1 2 Leon Dowdy

# 1 3 Joseph H. Bevins

# 1 4 Henry A. Myles

Louisville, Winston County

# 6 John L. Hathorn

# 5 2 Clevaris Gladway

# 5 9 C. N. Eiland

Byhalia, Marshall County

# 8 3 Willis D. Hamm

Poplarville, Pearl River County

# 1 7 J. Monroe Spiers

Canton, Madison County

# 1 6 William Albert Bender

Sibley, Adams County

# 8 1 Joseph Rounds

Gulfport, Harrison County

# 3 7 Richard E. Daniel

# 5 0 Varnado R. Collier

# 5 7 Dr. M. S. Love

34

Pass Christian, Harrison County

# 3 8 Father George T. J. Strype

# 3 9 Thomas Guyot, Jr.

# 4 0 Eugene H. Roberts

Natchez, Adams County

# 75 Mrs. Camille Z. Thomas

# 8 2 Samuel Davis

Marks, Quitman County

# 5 4 Eshmiel Charles Kelly

(drove Bender)

Greenwood, Leflore County

# 6 0 J. D. Collins

# 6 1 A. C. Montgomery

# 6 2 Clark Wilson

# 6 3 Louis Redd

# 6 4 Liesta A. Prichard

Magnolia, Pike County

# 6 7 Junius R. Moore

Port Gibson, Claiborne County

# 8 7 Kattie Campbell

N um ber of Co m pla in in g W itnesses from E ach T ow n

15 Jackson (Hinds) Central

1 Puckett (Rankin) Central

1 Vicksburg (W arren) S. W .

4 Greenville (Washington) West

Central

3 Louisville (W inston) E. Central

6 Meridian (Lauderdale) E. Central

1 Byhalia (Marshall) Extreme

North (Middle)

1 Poplarville (Pearl River) South

( Central)

1 Canton (Madison) Central

1 Tougaloo (H inds) Central

1 Sibley (Adams) S. W .

7 McComb (Pike) S. W .

3 Gulfport (Harrison) S. E.

3 Pass Christian (Harrison) S. E.

1 Bay St. Louis (Hancock) S. W.

( Central)

2 Holly Springs (Marshall)

Extreme N.

2 Natchez (Adams) S. W .

1 Crystal Springs (Copiah) S. W .

Central

1 Marks (Quitman) N. W .

1 Edwards (Hinds) Central

5 Greenwood (LeFlore) N. W.

4 Tylertown (Walthall) Ex.

South-West

1 Magnolia (Pike) Ex. South-

Central

2 Grenada (Grenada) North

Central

1 Port Gibson (Claiborne) West

(South W est)

Defense W itnesses:

# 4 Dr. E. J. Matvanga, Jackson, Chiropodist.

# 33 Ezell Singleton, Brandon, Veterans Registerman.

# 44 Dave P. Gayden, Brandon, Circuit Clerk.

# 46 C. E. Cocke, Greenville, Circuit Clerk.

# 47 Emmett E. Reynolds, Louisville, Circuit Clerk.

# 48 Wendell R. Holmes, Magnolia, Circuit Clerk.

# 49 William Elton Moore, McComb, Sheriff.

# 51 Clifford R. Feld, Natchez, Circuit Clerk.

# 58 Robert L. Williams, Gulfport, City Policeman.

# 64 Shelby S. Steele, Greenwood, Insurance Broker.

# 65 A. D. Saffold, Greenwood, City Mayor.

# 68 E. K. Sauls, McComb (had altercation with Parham) Private Citizen.

# 72 E. R. Sanders, McComb, Chief of Police.

# 73 A. B. Williams, McComb, City Mayor.

Affidavit of John R. Jankin, Natchez, Election Manager.

35

# 76 Eaton Garriga, Pass Christian, Night Marshal.

# 77 Lester Garriga, Pass Christian, Harrison County, Patrolman, Com

missioner of Election.

# 78 A. T. McCollister, Pass Christian, Election Commissioner.

# 79 Charles C. Farragut, Past Christian, Election Commissioner.

# 88 J. V. Simmons, Gulfport, City Judge who convicted Daniel.

# 89 Theodore Bilbo, Poplarville.

# 90 Bedwell Adams, Pass Christian, Lieut. Gov. under Bilbo.

# 91 Ben Cameron, former U. S. Atty., Meridian.

# 92 J. F. Barbour, Yazoo City, former Judge.

# 9 3 H. H. Creekmore, Jackson

# 94 George Butler, Jackson, former Pres. Miss. State Bar Asso., member

State Demo. Exec. Comm.

# 95 J. Morgan Stevens, Jackson, campaigned with Bilbo in 1911.

# 96 Charles B. Cameron.

# 97 Jesse Shanks.

# 98 Hugh B. Gillespie.

# 99 Mrs. Mary Donaldson.

# 1 0 0 George L. Sheldon.

#101 Jesse Byrd.

# 1 0 2 A. B. Friend.

APPEN D IX B

Caldwell o f Kansas

In the case of Senator Caldwell of Kansas, 42nd Congress, 3rd

Session, in February and March, 1875, a Senatorial committee reported

that it found Caldwell guilty of personal bribery and could not, or at

least did not, find whether enough votes were bribed to change the

result. Two resolutions were introduced which clearly raised the

issue, but before it could be decided by the Senate, Senator Caldwell

resigned.

Clark o f Montana

In the 56th Congress, 1st Session, Senator Clark of Montana was

admitted to his seat on March 4, 1899; after an investigation the com

mittee divided in its report, but agreed unanimously April 23, 1900 on

a resolution reading as follows:

‘ ‘ Resolved, That William A. Clark was not duly and legally

elected to a seat in the Senate of the United States by the legis

lature of the State of Montana.”

36

The committee found that enough votes were corrupted to change

the result and that “ It is also a reasonable conclusion upon the whole

case that Senator Clark is fairly to be charged with knowledge of the

acts done in his behalf by his committee and his agents . . . .”

The resolution is in the form of an exclusion, but since the com

mittee found that enough votes were corrupted to change the result,

we cannot know that they considered personal responsibility for an act

or acts of corruption, not sufficient to change the result, the sole grounds

for their exclusion resolution. In any event, Senator Clark resigned

on May 11, 1900 while the resolution was being debated.

Case o f Senator Lorimer, Illinois

In the case of William Lorimer of Illinois, 61st and 62nd Con

gresses, Lorimer took his oath without objection on June 18, 1909. On

May 28, 1910 on his own motion a resolution was introduced to investi

gate his right to his seat as against charges of corruption raised by

The Chicago Tribune. This case in the Senate was heatedly debated

after the majority of the committee reported on December 21, 1910 that

he was entitled to his seat.

Senator Beveridge filed minority views with the following recom

mended resolution:

“ Resolved, That William Lorimer was not duly and legally

elected to a seat in the Senate of the United States by the legis

lature of the State of Illinois.” (Cannon’s Precedents, Yol. 71,

p. 182.)

Lorimer was allowed to retain his seat, the minority resolution being

defeated.

Lorimer was later unseated in the 62nd Congress on July 13, 1912

by a vote of 55 yeas to 28 nays on a resolution reading as follows:

“ Resolved, That corrupt methods and practices were em

ployed in the election of William Lorimer to the Senate of the

United States from the State of Illinois, and that his election

was therefore invalid.” (Cannon’s Precedents, Yol. VI, p. 196.)

37

The broad form of this resolution indicates that it is a forerunner

of the resolution later used in the Smith and Vare cases. It will be

noted that it does not say that the “ corrupt methods” either affected

a decisive number of votes or that Lorimer personally practiced, en

couraged or condoned them, the technical requirements of the law.

Case o f Senator N ewberry

The first case, involving this issue, after the Seventeenth Amend

ment was the celebrated Neivbemj case. Newberry defeated Ford in

the Republican primary of 1918 and later defeated him, as the Demo

cratic candidate, in the general election of that year. He took the oath

and was seated May 19, 1919. He admittedly spent $195,000 in his

campaign. He and others were tried and convicted in 1920 in the United