Brinkman v. Gilligan Reply Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

April 6, 1978

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brinkman v. Gilligan Reply Brief for Appellants, 1978. ca44688d-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/84d9664c-a005-4812-9f73-ed34d9da261a/brinkman-v-gilligan-reply-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

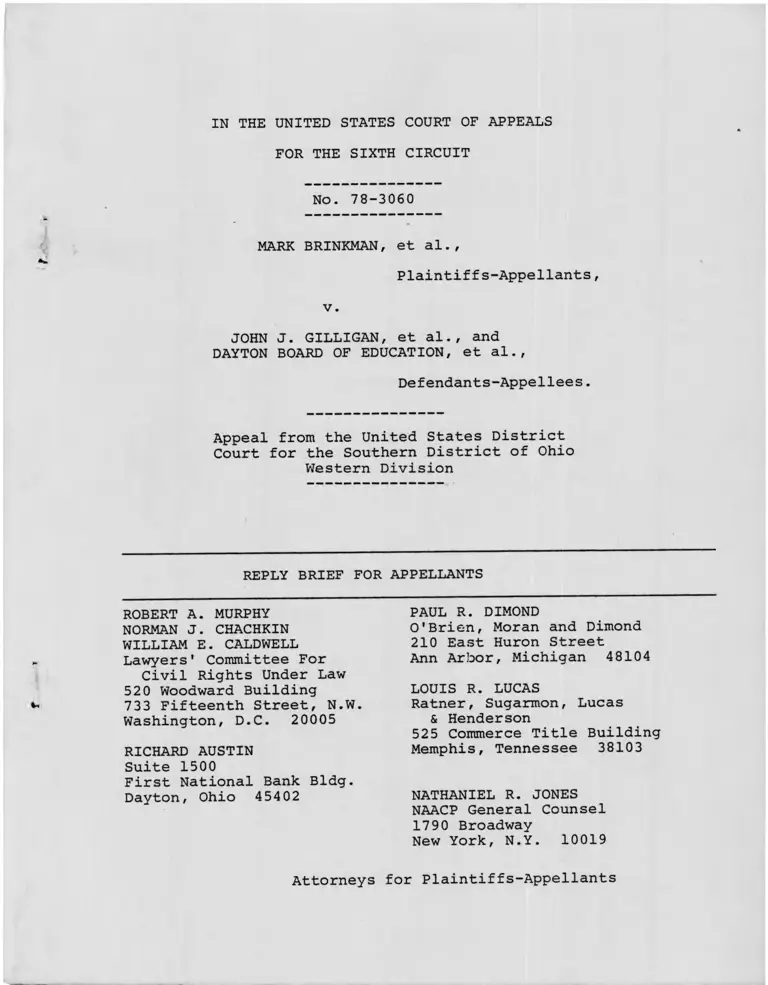

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 78-3060

MARK BRINKMAN, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

JOHN J . GILLIGAN, et al., and

DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Southern District of Ohio

Western Division

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

ROBERT A. MURPHY

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

Lawyers' Committee For

Civil Rights Under Law

520 Woodward Building

733 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

RICHARD AUSTIN

Suite 1500

First National Bank Bldg.

Dayton, Ohio 45402

PAUL R. DIMOND

O'Brien, Moran and Dimond

210 East Huron Street

Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104

LOUIS R. LUCAS

Ratner, Sugarmon, Lucas

& Henderson

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

NATHANIEL R. JONES

NAACP General Counsel

1790 Broadway

New York, N.Y. 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES............................... i

I. THE STANDARDS OF R E V I E W .................... 2

II. THE APPLICABLE PRINCIPLES OF L A W ............. 7

A. The Law in General.................... 7

B. The Pre-Brown Dual System............. 8

C. The Standards for Determining

Segregative Intent of Post-Brown

Conduct.................. ............ 15

D. The Burden of Disproving

Segregative Impact........ •........... 17

III. THE FACTS AND APPLICATION OF THE LAW

TO THE FACTS................................. 18

IV. SYSTEMWIDE IMPACT............................... 2 9

CONCLUSION........................................ 3 0

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE 31

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page No.

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody-

422 U.S. 405 (1975) . 5

Arthur v. Nyquist, Nos. 12-18, 203

(2d Cir. March 8, 1978) f 8

Bronson v. Board of Educ. of Cincinnati,

525 F.2d 344 (6th Cir. 1975), cert, denied,

425 U.S. 934 (1976) 7, 16

Davis v. School Dist. of Pontiac, 443 F.2d

575 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 913

(1971) . 18

Dayton Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406

• (1977) 8

Glasson v. City of Louisville, 518 F.2d 899

(6th Cir.), cert, denied, 423 U.S. 930

(1975) 2

Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, 482 F.2d

1044 (6th Cir.) (en banc), cert, denied,

414 U.S. 1171 (1973) 4, 5

Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430

(1968) 5, 10, 13

Higgins v. Board of Educ. of Grand Rapids,

395 F. Supp. 444 (W.D. Mich. 1973) ,

aff'd, 508 F .2d 779 (6th Cir. 1974) 6 , 17-18

Kelley v. Guinn, 456 F.2d 100 (9th Cir. 1972),

cert, denied, 413 U.S. 919 (1973) 18

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 413 U.S. 189

(1973) ......................................... 5,

13

17

10, 12,

, 15, 16,

, 18, 27

Lemon v. Kurtzman, 411 U.S. 192 (1973).............. 5

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145

(1965) ........................................... 5

Page No,

Mapp v. Board of Educ. of Chattanooga,

477 F.2d 851 (6th Cir.) (en banc),

cert, denied, 414 U.S. 1022 (1973) ' a

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267

(1977) (Milliken II) 5

NAACP v. Lansing Bd. of Educ., 559 F.2d

1042 (6th Cir. 1977), cert denied,

46 U.S.L.W. 3390 (U.S. Dec. 12 , 1977)............ 7, 8, 16

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis

489 F .2d 15 (6th Cir. 1973), cert.

denied, 416 U.S. 962 (1974). T T~................ 4

Oliver v. Michigan State Bd. of Educ.,

508 F.2d 178 (6th Cir. 1974), cert.

denied, 421 U.S. 963 (1975)...................... 7, 16, 18

Robinson v. Shelby County Bd. of Educ.,

467 F. 2d 1187 (6th cir. 1972) .................. 4

Swann v. Charlotte-Macklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1 (1971)................................. 5, 10, 11,

12, 13, 17

United States v. Board of School Comm'rs

of Indianapolis, Nos. 75-1730-1737,

et al. (7th Cir. Feb. 14, 1 9 7 8 ) ................ 8

United States v. Oregon State Med. Soc.,

343 U.S. 326 (1952)..................

United States v. School Dist. of Omaha,

565 F.2d 127 (8th Cir. 1977) (en banc),

cert, denied, 46 U.S.L.W. 3526 (U.S.

Feb. 21 , 1978)................................... 8

United States v. Texas Educ. Agency,

546 F. 2d 162 (5th Cir. 1977) (Austin III)........ 8

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Dev. Corp., 42 9 U.S. 252 ( 1 9 7 7 )........ 4 , 7, 8

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976)............ 7,8

l i .

Rule 32(a)(2), FED. R. CIV. P........................ 4

Rule 52(a), FED. R. CIV. P............................ 2

Rule 801(d)(2), FED. R. EVID.......................... 4

Rule 804(b)(4), FED. R. EVID.......................... 4

Articles;

Godbold, Twenty Pages and Twenty Minutes —

Effective Advocacy On Appeal, 30 SW. L.J.

801 (1976)......................................... 12

Rules: Page Ho.

iii.

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 78-3060

MARK BRINKMAN, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

JOHN J. GILLIGAN, et al., and

DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Southern District of Ohio

Western Division

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

The brief for defendant Dayton Board of Education

is long on imagery but short on a substantive response to the

controlling law and dispositive record evidence in this case.

1/ The Brief for Defendants-Appellees is referred to herein

as "Board Br."; the Brief for Appellants is referred to

as "Plaintiffs' Br."; the Brief for the United States

as Amicus Curiae is cited as "U.S. Br.," with the

United States' amicus brief in the Supreme Court (which

has been submitted to this Court) being referred to as

"U.S. S.Ct. Br."

As we demonstrate in this reply brief, the Board fails to

come to grips with the merits of plaintiffs' position with

respect to the standards for appellate review (pp. 2-7 , infra)

the applicable principles of law (pp.7-I7 , infra), and the

facts and application of the law to the facts (pp.18-28, infra)

I. THE STANDARDS OF REVIEW

Defendants agree (Board Br. 4) with plaintiffs'

emphasis (Plaintiffs' Br. 6-20) on the appropriate standards

of appellate review. Defendants also seem to agree (Board

Br. 5) with plaintiffs' analysis of the legal principles which

govern review. Thus frustrated by having nothing substantive

to quarrel about, the Board criticizes us for citing so many

2/cases. Board Br. 4 .— The Board then falsely implies that

we have suggested that Rule 52(a) "should be suspended in a

case of this nature" (id.) and that it is our "ultimate

suggestion that this Court should feel free to jump into the

record of this case untrammeled by any 'clearly erroneous'

standard." Id. at 5. This is sheer hyperbole.

In addition, defendants charge, without reference

to any part of the record or any finding of the district

y Despite defendants' criticism, we are obliged to add

the additional citation, previously overlooked, to

Judge McCree's opinion for this Court in Glasson v.

City of Louisville, 518 F.2d 899, 903 (6th Cir.),

cert, denied, 423 U.S. 930 (1975), holding that

"determinations, whether called ultimate findings or

conclusions of law, that attach legal significance to

historical facts may be reversed if upon examination

of the record they are found to be erroneous."

-2-

judge, that "much of the testimony is raw opinion testimony

of [plaintiffs'] witnesses who have obvious ideological moti

vation to secure a specific result" (Board Br. 6), and that

"most of these people [in the main, Board members and other

managing—agent employees of the Board] were unabashed advocates

of the plaintiffs' theories....- id. at 7.-' Aside from

the complete lack of support for these assertions in either

the record or the district court's findings, defendants fail

to realize that their logic equally supports the view that all

of defendants' witnesses are unabashed ideological segrega—

tionists. If the testimony of the Board members and employees

who were called to testify as plaintiffs' witnesses is to be

discounted solely because they testified as part of plaintiffs'

case and therefore are deemed to be biased integrationists,

then the testimony of those Board members and employees called

by the Board should either be similarly discounted or, more

probatively, should be treated as an additional element of

plaintiffs' case of purposeful segregation. There is, of course,

no sound basis for a rule that a witness is ipso facto biased

in favor of the party calling him. Such a rule would relegate

37 Even in this unfounded claim, the Board does not challenge

on grounds of bias or demeanor the testimony of other of

plaintiffs' witnesses (e.g., Phyllis Greer, Ella Lowery

and Gordon Foster), who provided most of the factual

foundation for plaintiffs' case of pervasive discrimination

continuing through the time of trial in 1972.

-3-

litigants to resting their cases on proof produced hy

their opponents! The only remotely relevant rule of

evidence is that admissions of the managing agents of an

adverse party are likely to be probative if they are against

the interests of the adverse party. Cf. Rule 32(a)(2),

FED. R. CIV. p.; Rules 801(d)(2) and 804(b)(4), FED. R.

EVID. Indeed, it is the rare case where, as here, public

officials will admit either segregative purpose with respect

to particular events or a regime of segregation with respect

to an entire system of public administration. Cf. Village

of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Dev. Corp.,

429 U.S. 252, 265 (1977). In all events, the Board's brief

is devoid of a single example of a district court finding

that is predicated upon witness demeanor and credibility.

There are no such findings. To the contrary, the district

judge, albeit by selective misreading, relies upon the testi

mony of those very same Board members and employees whom the

Board now claims were biased for plaintiffs. See, e.g.,

Plaintiffs Br. 19a-20a (Carle testimony).

Finally, defendants' reliance (Board Br. 7-8)

upon Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, 482 F.2d 1044

(6th Cir.) (en banc), cert denied, 414 U.S. 1171 (1973), is

misplaced. Goss, like similar decisions of this Court,—^

4_/ See, e.g. , Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis,

489 F .2d 15 (6th Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 416 U.S.

962 (1974); Mapp v. Board of Educ. of Chattanooga,

477 F.2d 851 (6th Cir.) (en banc), cert denied,

414 U.S. 1022 (1973); Robinson v. Shelby County Bd.

of Educ., 467 F .2d 1187 (6th Cir. 1972).

-4-

is different from this case (which essentially involves

only questions of liability, see p, 29, infra) because it

involved questions of the adequacy of a district court's

remedial decree in light of the established discretion of

trial judges in formulating equitable decrees. In such

circumstances, appellate review is guided not only by the

"clearly erroneous" standard, but also — as Goss' citation

and quotation (482 F.2d at 1047) of Lemon v. Kurtzman,

411 U.S. 192, 199-201 (1973), makes clear — by the rule

that "[i]n shaping equity decrees, the trial court is vested

with broad discretionary power; appellate review is

correspondingly narrow." Id. at 2 0 0 . The standards of

review in such cases thus accord greater deference to the

district judge's "special blend of what is necessary, what

is fair, and what is workable." Id. (footnote omitted).

Goss and its kind thus do not represent pure applications of

the "clearly erroneous" standard to lower court dispositions

of basic liability issues, such as those involved here.

A more appropriate example of the application of

the "clearly erroneous" standard to a case such as this is the

57 Of course, the "discretion" of trial courts in such

circumstances is not untrammeled, and is governed by

the rules that an equity court must shape its decree

so as to secure "complete justice," Albemarle Paper

Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 418 (1975), and that "the

court has not merely the power but the duty to render

a decree which will so far as possible eliminate the

discriminatory effects of the past as well as bar like

discrimination in the future." Louisiana v. United

States, 380 U.S. 145, 154 (1965). These principles

are as applicable to school cases as they are to

employment and voting rights cases. See, e.g., Milliken

v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977) (Milliken II); Keyes v.

School Dist. No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973); Swann v .

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (1971);

Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430 (1968).

-5-

late Judge William E. Miller's opinion for this Court

in Higgins v. Board of Educ. of Grand Rapids, 508 F.2d 779

(6th Cir. 1974). Although the plaintiffs in that case did

not prevail, Judge Miller's opinion evidences an appropriate

careful scrutiny of the record with respect to all factual,

legal and mixed fact/law issues. A similar approach is

necessary in the instant case.

In addition to its importance as an example of

painstaking appellate review, Higgins provides instructive

comparisons with this case. One such comparison is between

the Higgins facts and those of record here: in contrast to

the overwhelming evidence of longstanding purposeful segrega

tion presented by the instant record, the Higgins facts

reflect a board of education which did not seize upon every

opportunity to institute and perpetuate racial segregation.

Also informative is a comparison of Judge Engel's compre

hensive, meticulous opinion for the district court in Higgins,

395 F.Supp. 444 (W.D. Mich. 1973), with the scattershot,

conclusory opinion below: the quality and logic of the former

command considerable deference, that of the latter virtually

none.

In short, it is not the law of this or any other

reviewing court that whatever the trial court finds in school

or other discrimination cases controls on appeal regardless

of the errors — of law and mixed law and fact, and of

-6-

ultimate and subsidiary fact-finding — committed below.

The standards governing this Court's review of the judgment

below are as stated in our opening brief (pp. 6-20). These

standards do not insulate from review the gross miscarriage

of justice embodied in the judgment below. On the contrary,

these standards mandate correction of such manifest injustice.

II. THE APPLICABLE PRINCIPLES OF LAW

A. The Law in General

Defendants' brief (pp. 9 & 12) leaves the impression

that, because plaintiffs did not cite Washington v.

Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976), and Village of Arlington Heights

v. Metropolitan Housing Dev. Corp., supra, at a particular

point in their brief,—^ plaintiffs have somehow tried to hide

the law. The fact is, however, that the main thesis of

plaintiffs' brief is that the record evidence proves "deliber

ate, purposeful, systematic discrimination" (Board Br. 11)

beyond any reasonable doubt, even without correction of the

6/ Plaintiffs did cite and rely upon these cases throughout

their brief. See Plaintiff's Br. 22, 29, 34, 44, 45, 58.

In contrast, we note that nowhere do defendants cite,

or even acknowledge, the law of this Circuit — set forth

in NAACP v. Lansing Bd. of Educ., 559 F.2d 1042 (6th Cir.

1977), cert, denied, 46 U.S.L.W. 3390 (U.S. Dec. 12, 1977)

Bronson v. Board of Educ. of Cincinnati, 525 F.2d 344

(6th Cir. 1975), cert, d e n i e d 425 U.S. 934 (1976) ; Oliver

v. Michigan State Bd. of Educ., 508 F.2d 178 (6th Cir.

1974), cert, denied, 421 U.S. 963 (1975) — imposing

the "natural, probable and foreseeable result" test for

determining prima facie segregative intent in school cases

(This governing test is not necessary to a disposition of

this appeal in plaintiffs' favor, however, because the

record here contains abundant direct evidence of explicit

[footnote cont'd]

-7-

the major errors of law made by the district court and

perpetuated here by the Board. Our opening brief explicates

the correct principles of constitutional law. The Board's

brief defends the opinion of the district court and,

therefore, contains erroneous statements of the applicable law.

B. The Pre-Brown Dual System

With the exception of the West Side reorganization

(see pp. 19-21 infra), defendants do not deny the facts

showing the Board engaged in extensive pre-Brown purposeful

segregation. The Board's factual concession, that "the

history of the Dayton system has [not] been wholly free from

acts or practices that could be considered segregative" (Board

Br. 14), is considerably understated, however, and its

view of the law is unacceptable.

67 (cont'd)

segregative intent.) In addition to this Court

(see Lansing, supra), three other Circuits (two in

cases in which, like Lansing, the Supreme Court has

declined review) have applied the test in school

desegregation cases in the light of the Supreme Court

decisions in Washington v. Davis, Arlington Heights,

and this case, Dayton Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman, 433

U.S. 406 (1977). See Arthur v. Nyquist, Nos. 12-18,

203 (2d Cir. March 8, 1978); United States v. School

Pist. of Omaha, 565 F.2d 127 (8th Cir. 1977) (en banc) ,

cert, denied, 46 U.S.L.W. 3526 (U.S. Feb. 21, 1978);

United States v. Texas Educ. Agency, 546 F.2d 162

(5th Cir. 1977) (Austin III). See also United States v.

Board of School Comm'rs of Indianapolis, Nos. 75-1730-

1737, et al. (7th Cir. Feb. 14, 1978) (opinion of

Swygert, J.).

-8-

In our opening brief, we argued (Plaintiffs' Br,

26-30), as did the United States (U.S. Br. 12-15; U.S. S.Ct.

Br. 23-33), that the essentially undisputed pre-Brown

facts establish that "in 1954 the Dayton School Board operated

two school systems, one primarily for white students and another

primarily for blacks." U.S. Br. 12; U.S. S.Ct. Br. 28.

Defendants answer this argument (Board Br. 12-15) by miscasting

the argument and by attempting to minimize the legal signifi

cance of the facts.

Defendants mis-state the argument by treating it

as though it "suggested that a point in time twenty-four

years ago be picked as a determinative point of inquiry."

Board Br. 13. On the contrary, we have not attempted to

cut off the inquiry at 1954. But the pre-1954 events are,

for two reasons, highly relevant. One is the factual reason

that, in Justice Jackson's words, "present events have roots

in the past, and it is quite proper to trace currently

questioned conduct backwards to illuminate its connections

and meanings." United States v. Oregon State Med. Soc. ,

343 U.S. 326, 332 (1952). Thus, as we emphasized throughout

our opening brief, the pre-Brown part of the record has

immense significance because "it illuminates or explains the

present and predicts the shape of things to come." Id. at 333.

The second reason why the pre-Brown events are

relevant is the legal one that the Board was under an affirma

tive post-Brown duty to undo, rather than build upon, the

-9-

extensive segregation of pupils and teachers which the Board

had intentionally created. If the Board's pre-Brown deliberate

segregative practices were systemwide in purpose and effect,

then the Board's post-Brown obligation was affirmatively to dis

mantle such a dual system or otherwise to show with particularity

that continuing one-race schools were genuinely nondiscrimina-

tory rather than the legacy of the historic dual system.

Swann, 402 U.S. at 24-26; Keyes, 413 U.S. at 205, 210-14.

In that circumstance, even if the Board were correct in

asserting that "the School Board has done nothing to alter

attendance boundaries in any significant manner or to otherwise

channel black or white students to different schools for

twenty-four years" (Board Br. 1 3 ) the Board is plainly

wrong in concluding, without more, that "the point of

attenuation would clearly appear to have been reached even

if there were anything twenty-four years ago to attentuate!"

Id. at 13-14. No "southern" school system would have been

required to desegregate, as mandated by Green and Swann, if

there were any merit in defendants' simplistic argument that

the passage of time alone proves attenuation,

Swann, Keyes and common sense are a complete and

sufficient answer to the Board's argument that the mere

passage of time in conjunction with ostensibly race-neutral

school board action attenuates illegal segregation.

7/ Which, of course, is wholly untrue.

-10-

In Swann the Court ordered all-out desegregation, necessarily

rejecting any such time-equals-attenuation theory, despite

the Chief Justice's recognition of the following complicating

factors (402 U.S. at 14) (footnote omitted) (emphasis added):

The failure of local authorities

to meet their constitutional obliga

tions aggravated the massive problem

of converting from the state-enforced

discrimination of racially separate

school systems. This process has been

rendered more difficult by changes

1954 in the structure and patterns

since

of

communities, the growth of student

population, movement of families, and

other changes , some of which had marked

impact on school planning, sometimes

neutralizing or negating remedial action

before it was fully implemented. Rural

areas accustomed for half a century to

the consolidated school systems imple

mented by bus transportation could make

adjustments more readily than metropolitan

areas with dense and shifting population,

numerous schools, congested and complex

traffic patterns.

Despite these factors, the Court in Swann recognized

the long-term segregative impact of race-based school board

actions (id. at 20-21), and held that such a "loaded game

board" must be set right even if it is necessary to employ

race-conscious, instead of "[rjacially neutral," means.

Id.at 28. The Board here is thus wrong in assuming that

post-Brown racial neutrality and the passage of time alone

require the conclusion that the pre-Brown segregation has

been attenuated. But even if attenuation is an appropriate

inquiry in these circumstances, where the Board undertook

virtually no post-Brown affirmative efforts to disestablish

the dual system, it obviously is an investigation dependent

-11-

upon a factual showing that there is no substantial

"relationship between past segregative acts and present

segregation...," Keyes, 413 U.S. at 2 1 1 . Here the

Board has made no real effort to show "that its past

segregative acts did not create or contribute to the current

segregated condition...," Id. Any such effort would,

in any event, be defeated by the facts detailed in our

opening brief (and summarized at pp.22-28.infra) which

reveal that the Board's post-Brown conduct was not aimed

at uprooting the dual system, but at perpetuating it.

Defendants' final relevant effort—^ to dispose

of the Brown violation argument is the claim that the facts

do not add up to a dual system at the time of Brown.

87 Swann holds that, in the context of a prior dual system,

school boards will be relieved of their post-Brown

obligations only "once the affirmative duty to desegregate

has been accomplished and racial discrimination through

official action is eliminated from the system." 402

U.S. at 32. In acknowledging a possible attenuation

defense, Keyes cites (413 U.S. at 211) this part of

Swann, but the Keyes discussion of attentuation must be

placed in the context of findings of intentional segre

gation directed at only a part of the system (38% of

the black students). We assume arguendo, however, that

attentuation is also a proper issue in the context of

proven systemwide segregative practices.

9/ The Board also attempts to dispel the Brown argument

by references to the questions propounded by individual

Justices during the oral argument in this case last

Term. Board Br. 15. Even if the views expressed by an

individual Justice during questioning are not the

product of confusion and represent the actual views of

that Justice (an assumption that is not necessarily

correct, see Godbold, Twenty Pages and Twenty Minutes—

Effective Advocacy On Appeal, 30 SW. L.J. 801, 818 (1976))

[footnote cont'd]

-12-

I

Board Br. 14. Factual misrepresentations aside, — ^ the

Board's thesis is that a school system cannot be classified

in the "dual" category unless all of the students attend

100% segregated schools. The facts (see generally Plaintiffs

Br., App. C) are these: The Board operated about 50 schools

enrolling about 35,000 students (19% of whom were black)

during the 1951-52 school year (the last one before 1963

for which race data is available). Fifty—four percent

(.3,602 of a total 6,628) of the black students were enrolled

in the four schools officially designated for blacks only;

9/ (cont'd)

and even if that Justice would vote to have his views

incorporated into a judicial decision (another not-

necessarily-correct assumption) it is difficult to

understand how such views, not even mentioned in the

Supreme Court's subsequent unanimous decision in this

case, can be of benefit to this Court, which is

bound to carry out the opinions and judgments of the

Supreme Court, and not what might have been. Especially

is this so when it is realized that defendants' speculation

about what might have been includes the necessity to

explicitly overrule all or parts of Keyes, Swann,

Green and Brown II. This Court is not free to act on

such hypothesis, even in the unlikely event that the

Court is persuaded by defendants' speculation.

I V illustrative example of the Board's factual misrepre

sentations is the statement that, with respect to "the

two optional high schools...[,] any student in the system

was free to attend or not to attend..." Board Br. 14. The

"true facts" are that white students were not "free"

to attend the blacks-only (pupils and teachers) Dunbar

High School (black teachers were not allowed to teach

white children during the pre-Brown period, and Dunbar

had only black teachers assigned to it), nor were black

students "free" to attend the 100% white (students and

faculty) Patterson Co-op. See Plaintiffs Br., App. C.

Also untrue is defendants' statement that the three

elementary schools (Garfield, Willard and Wogaman) which

had been converted into blacks-only schools in the 1930's

and 1940's to contain the growing black population "simply

reflected in student compostion the race of the geographic

[footnote cont'd]-13-

83% (23,514 of a total 28,320) of the white students

attended schools which were virtually (90% or more) all

white. S. Ct. A. 312 (PX 2B), 506 (PX 100E). Thus,

without regard to the fact that at least another 19% of the

black pupils were attending the five schools which were

about to become black schools by virtue of the West Side

reorganization (as to which there is an "ultimate fact"

dispute, see pp.19-21, infra), well over three-fourths of

all pupils and virtually all teachers attended one-race

schools.

We think, and we are supported by the persuasive

brief of the United States, that the Brown facts are

sufficient to constitute the Dayton district a dual system

at the time of Brown, and that the defendants never thereafter

complied with their affirmative remedial duties until the

instant litigation. It may not have been a "perfect" dual

system as in states where absolute apartheid was mandated by

10/ (cont'd)

neighborhoods they served." Board Br. 14. Wholly

apart from the impact on residential racial patterns

of the Board's de jure policies and practices which

identified these schools and their neighborhoods

as unfit for whites, the fact is that there were

white students residing in these neighborhoods —

white students whom the Board persistently accommodated

by providing them, over the years, with "free transfers"

and "optional attendance" areas to enable them to

avoid attendance with black students. See Plaintiffs'

Br., App. C. at pp. 17a-18a and n. 11.

-14-

state, law, but, by reason of the Board's systemwide

policies and practices, the tolerated breaches of the color

line were few and far between. If the sum of these facts

is not "dual system," then there can be no such thing in

the nonstatutory, "northern" context. To so conclude,

however, is to say that Keyes was based on a false premise

or was otherwise wrongly decided — a conclusion which only

the Court that decided Keyes is authorized to reach.

* * * *

We have not rested our case at this point, however,

and we urge the Court not to stop here. For the Board's

post-Brown conduct, detailed in our opening brief and

discusssed again in part III, infra, also requires judgment

for plaintiffs; since 1954 the Board purposefully perpetuated

supplemented and expanded the extensive pre-Brown intentional

segregation so that almost no black and white children

attended school together at the time of complaint and trial

in 1972.

C. The Standards for Determining Segregative

Intent of Post-Brown Conduct_____________

In our opening brief we pointed out that the

district court had, in addition to its mistaken legal evalua

tion of the pre-Brown facts, committed two basic legal errors

in analyzing post-Brown conduct for segregative intent: first,

the court ignored altogether the prima facie case principles

-15-

laid down in Keyes, and, second, the court disregarded

the principle, laid down in the applicable decisions of

this Court, that an actor is presumed to have intended the

plainly foreseeable consequences of his action. Plaintiffs'

Br. 30-33. In lieu of responding to our argument pertaining

to the second error, the Board engages in a rhetorical

dialogue with itself (Board Br. 15-18) which ignores both

the facts and the law, and which both misrepresents the

testimony of three witnesses (present and former Board

members and employees) and treats them as though they

were plaintiffs' legal spokesmen. The basic purpose of

this smokescreen is to argue, without saying so, that

the "natural, probable and foreseeable result" test of

segregative intent is wrong, even though only recently re

affirmed by this Court in Lansing.— ^

With respect to plaintiffs' argument that the

court below violated Keyes by refusing to employ its burden-

shifting principles to the issue of segregative intent,

the Board seeks to obfuscate the issue, as did the district

court, by including it with a discussion about the burden

of proving segregative impact (which we discuss next). The

ii/ As we have noted (see note 6, supra) , the Oliver/Bronson/

Lansing test is not essential to plaintiffs' success in

this case because the direct evidence, much of it of

a subjective nature, of segregative intent is overpowering.

-16-

Board’s argument on the intent burden (Board Br. 18-22)

boils down to the naked contention that "there is no basis

for the triggering of a shift of the burden from the

plaintiffs to the defendants...[because] the plaintiffs

here simply failed to establish any intentionally segregative

policies practiced in a meaningful or significant segment of

the school system." Id.at 19.— ^— In our opening brief

(pp. 26-60, 7a-54a) we have shown that this is wishful thinking

by defendants.

D- The Burden of Disproving Segregative Impact

The Board argues, in support of the district court,

that "the burden of proof on the issue of incremental

segregative effects rests upon the plaintiffs" (Board Br. 21),

and that Keyes does not require application of a presumption

"to the remedial issue of determining incremental segregative

effect." Id. at 20. The Board is wrong. See Keyes, 413 U.S.

at 211 n. 17, 213—14; Swann, 402 U.S. at 26; see also the

numerous similar holdings cited in Plaintiffs' Br. 33-34, 61-65.

12/ The Board cites Higgins, supra, 508 F.2d at 789, for

the proposition that "this Court questioned the

applicability of the Keyes presumption to teacher

assignment practices," Board Br. 19. What the Court

actually said in Higgins was this (emphasis in original)

(footnote omitted):

Keyes involved findings as to various

geographical areas. It did not deal with

separate aspects or features of a total

system, such as teacher assignments as

opposed to student assignments. Here,

while there was a finding of illegal dis

crimination in teacher assignments, it

is not clear that the placement of teachers

[footnote cont'd]-17-

III. THE FACTS AND APPLICATION OF THE

LAW TO THE FACTS________________

1. Defendants CBoard Br. 22-27) string together

several unrelated fact situations, and selectively rail against

the testimony of a few witnesses (a Board member, the former

superintendent, and the former assistant superintendent)

called by plaintiffs, in support of the astounding contention

12/ (cont'd)

according to race, largely corresponding

to teacher preferences and under the

educational rationale considered to be

valid at the time, should give rise to

the Keyes presumption.

This language must be read in, and confined to,the

factual context that produced it. In Higgins

Judge Engel had predicated his faculty-violation findings

on rather meager direct evidence of segregative intent

pertaining to the 1940's and on the statistical pattern

of assigning teachers over the years on a largely

segregated basis. See 395 F. Supp. at 474-79. There was

not in Higgins, as there is in this case, direct or any other

evidence of a board policy prohibiting black teachers from

teaching white children, subsequently modified to become

more demeaning by allowing black teachers to teach white

children only if the affected white communities agreed, and

not requiring white teachers against their will to teach

black children. See Plaintiffs' Br., App. C. The Dayton

Board's faculty-assignment policy, until interdicted by

HEW in 1969, was the equivalent of a proclamation of

racial segregation. Standing alone, this proof has more

probative value to the question of segregative intent than

all of the evidence in Keyes combined. Whatever the merits

of the Higgins dictum, it is manifestly inapplicable here.

This Court and others have, of course, also noted that the

intentional segregation of staff is highly probative as to

Cl) a school board's intent with respect to other areas of

school administration resulting in segregation of pupils,

and (2) the racial earmarking or tailoring of schools for

"blacks" or "whites." See,e,g., Oliver v, Michigan State

Bd. of Educ., 508 F.2d 178, 185 (6th Cir. 1974) , cert,

denied, 421 U.S, 963 (1975); Kelley v. Guinn, 456 F.2d 100,

107 (9th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 413 U.S. 919 (1973);

Davis v. School Dist. of Pontiac, 443 F.2d 575, 576 (6th

Cir. ),cert, denied, 404 U.S. 913 (1971).

-18-

that (id, at 23) :

Wherever there has been unequivocal

direct or circumstantial evidence of

the Board's intent, that intent has

been exposed as an intent to make

access to schools as convenient as

possible for the greatest number of

students and, wherever possible, to

improve the racial mix of students

attending a given school.

Not even the district court, which from the outset bought

almost every ultimate conclusion advanced by defendants,

recited this fable! Most of these pages in the Board's

brief do not touch on significant facts, but we briefly

respond to each point.

The only point where the Board attempts to meet

a real issue pertains to the West Side reorganization

(Board Br. 23-24, 24-25), which is also the only instance

in which the Board disputes plaintiffs' ultimate factual

conclusions drawn from the undisputed pre—Brown subsidiary

facts. Plaintiffs' Br., App. C. Defendants have not

presented anything which detracts from our opening brief's

discussion (pp. 39-41 and App. C, pp. 16a-21a) of the West

Side reorganization. Defendants assert (without the context

of the other pre-Brown segregation policies) that the

"express purpose" of the changes was "attempting to place

more black students [from the deliberately-created blacks-

only schools] in integrated school environments." Board

Br. 23. But nothing in the statement or the supporting

-19-

, 13/record citation— ' refutes either (1) the undeniable

fact that the changes served to perpetuate intentional

segregation at the blacks-only schools which were born of

subjective racism, or (2) the plain conclusion that the

Board's "express purpose" was a sham, a subterfuge for the

Board's actual purpose of expanding the dual system so as to

contain (or find a new segregated place for) the growing black

population and — via a new system of optional zones,

construction of the all-black Miami Chapel elementary

school, and the implementation of a new racial staff assign

ment policy — to make the transition of the affected schools

from "mixed" to all-black status as convenient as possible

for the affected white population. See also note 10, supra.

13/ Defendants cite A. 813-14 and S, Ct. A. 591-92 in

support of their statement. The former citation is

to the testimony of a former Board employee called

by defendants (we wonder why he isn't characterized

as being "obviously biased" in favor of the Board,

cf. Board Br. 25), who testified that the purpose of

the West Side changes was to "allow some of the [black]

students in the periphery of those respective [blacks-

only] districts to attend integrated school [districts]

....» A. 814. The latter citation is to Joint

Exhibit I, a 1968 written statement to the Board by

former Superintendent Carle (made in August 1968

shortly after his arrival in Dayton that same year),

which was no more than a description of what the

Board's records said. Neither of these bits of evidence

casts doubt on the only conclusion (discussed again

in text) to be drawn from the basic facts which are

wholly undisputed.

-20-

Imagination must be exalted over reality to reach any conclu

sion other than thatthe West Side reorganization was a

deliberate perpetuation of the basically dual system.

The Board's random references to three unrelated

events — the construction of Roth High School in 1959

and Jefferson Primary in 1967, together with a 1969

boundary revision at Stivers High School (Board Br. 24) —

simply do not support the hypothesis that the Board was

integration-minded. First, the record citations proferred

by the Board do not support statements of events contained

14/m the Board's brief.— ■ Second, even were the Board

able to come up with a few minor quibble-worthy situations,

it would only serve to underscore the point of our opening

brief, to-wit, that the great mass of the facts lead un

relentingly to the conclusion that racial segregation has

consistently formed a decisive part of the Board's mind-set.

14/ For example, the Board says that "[a[nother clear-

cut example of the intent of the Board is the

building of Roth High School in 1959 in an area

deliberately chosen to provide a mixed student body.

(A. 815)." Board Br. 24. The citation to A. 815

is astonishing. On that page, the Board attorney

asks Board witness Curk the question, "In the

establishment of the Roth High School attendance

zone in 1959, was race taken into consideration?,"

and received the answer, "No. sir, it was not." How

the Board "deliberately chose[] to provide a [racially]

mixed student body" without taking race "into considera

tion" is among the many mysteries presented by the

Board's brief. The brief's other record citations

are of similar quality.

-21-

Similarly insignificant are the Board's quibbles

about the philosophical aspects of the testimony of witnesses

Carle, Harewood and Lucas (the former superintendent,

assistant superintendent, and present Board member, respectively),

the attempt to misuse and mischaracterize the testimony of

witness Williamson, and the attempt to exalt a mediocre

plaintiffs' witness (whom the district court would not even

allow to testify about pre-1954 matters with which the

witness was most familiar, see A. 1026) into "an impartial

historian." Board Br. 24-27. These are diversionary

skirmishes, designed to focus attention away from the main

body of the facts where both defendants and the district

court's opinions are totally vulnerable. This Court should

refuse the gambit.

2. Defendants' brief (pp. 28-39) next turns to an

Alice-in-Wonderland description of "[t]he evidence as a

whole... . " Id. at 28. With a few exceptions noted below

in the margin, these pages contain nothing qualified to

rebut the total factual picture established by the record

and described in our opening brief. It mostly suffices here

to summarize the key elements of that picture; a close

examination of the record will sustain the picture we present

and destroy the illusion which the Board endeavors to project.

-22-

Between 1912 and 1951-52, the Dayton Board

devised and carried out a number of racially discriminatory

policies and practices which both mistreated black students

and faculty and caused them to be confined to segregated

black schools; concomitantly, white teachers and pupils

received favored treatment, and they were accommodated in

reciprocally-maintained segregated white schools. These

policies and practices included; the humiliating operation

of all-black classrooms within, and in an outbuilding in back

of, the Garfield school; the refusal to allow black students

to attend white classes at Garfield, and the ultimate over

night coversion of Garfield into an officially-designated

blacks-only school; the rigid policy of never allowing black

teachers to teach white pupils, always assigning such teachers

only to all-black classes and/or schools; the overnight

conversions, in response to a growing black population, of

Willard and Wogamon schools into official blacks-only

schools; the construction and operation on a city-wide basis

of Dunbar as a blacks-only high school with, of course, an

all-black staff, accompanied by pupil-assignment and counselling

techniques designed to channel black students into Dunbar;

cooperation by contract with public housing authorities to

have children educated on a completely segregated basis in

public housing space officially and explicitly earmarked

according to race; the transportation of black orphanage

children past white schools across town to the blacks-only

23-

Garfield; a variety of within-school racially discriminatory

practices — requiring black children to sit in the back of

the class, not letting them participate in "white"

activities (e.g., being an angel in a school play), segregated

athletic competition, segregated showers, locker rooms and

swimming pools, and the like -- which further branded black

people as unfit for association with whites.

By 1951-52 about 54% of the black children and all

of the black teachers were in the four official blacks-only

schools; 83% of the white children were in virtually all-white

(90% or more) schools taught entirely by white teachers.

It was not against the law for blacks and whites to go to

school together in Dayton, but it clearly was the official

educational policy that learning in all of the public schools —

and, indeed, living — should take place on a racially

segregated or otherwise racially discriminatory basis. The

enormous severity and harm of this sytem were irreparably

compounded in 1951-52 under the guise of ostensibly favorable

responses to protestations from the black community. First,

the Board adopted a faculty-assignment policy that told black

teachers they could teach white children if white parents

were willing, and told white teachers not to worry, that

they would not be assigned against their will to black schools.

-24-

Second, the Board implemented the West Side reorganization

plan, which contracted the zone boundaries of the three

blacks-only elementary schools and added portions of those

zones with their black students to the adjacent "mixed"

schools (which already had substantial black enrollments, a

combined 20% of the total black pupil population), thereby

converting the adjacent five schools (one had just been built)

into all-black schools. The conversion of these latter

schools into all-black schools was not just inevitable: it

was plainly intentional, as evidenced by (1) the creation

of "optional attendance zones" (as a substitute for the

former "free transfer" policy) in white residential areas,

so that white students could easily transfer to the next

ring of white schools, and (2) the traditional means of

earmarking schools according to race, i.e., the assignment

(for the first time and thereafter in ever-increasing numbers)

of black teachers to these schools. By the time of Brown,

therefore, three-fourths of all black pupils and an even

greater percentage of all white students attended schools

segregated by race pursuant to specific official intent to

discriminate. At that time the Dayton Board was operating

a dual school system. Plaintiffs' Br. 37-43, 7a-23a.

In the post-Brown era the Board found it relatively

easy to build upon and perpetuate the segregated system it

had created. The racist faculty policy continued in raw

form and substantial practice until HEW intervention in 1969

-25-

resulted in an agreement requiring faculty desegregation

over a two-year period; but even under that agreement

remnants of the old policy were still present at the

time of trial.— ^ The Board expanded the use of optional

attendance zones which had their race—oriented origins in

the 1951-52 West Side reorganization — into a number of

new areas which had substantial segregative impact.— ^ In

addition, the Board resorted to a variety of other deviations

from geographic zoning" or the "neighborhood school" concept —

15/ The Board mis-states the testimony of Dr. Green when

it cites his testimony in support of the claim that

teacher assignment practices do not affect the perception

of schools and "had nothing whatsoever to do with the

changing racial compositions of the schools." Board

33. The unclear question and answer cited by the

Board were immediately clarified. Dr. Green emphasized

that the assignment of black teachers for the first

time to selected schools with high percentages of black

pupils, as occurred in the West Side reorganization, for

example, "could well and perhaps does facilitate that

school in becoming perceived as being a black school

or black area if I might use that term." A. 246. A

^iffsrent point made by Dr. Green, which seems to confuse

defendants, is that "desegregating the faculty of a

particular school community when in the past [there]

has been a systematic placement of teachers to schools

based on race, based upon the racial composition of the

school and using the race of the teacher as a factor,

simply desegregating the faculty without at the same

time desegregating the pupils or students within that

system does not change the community perception of that

school. A. 240-41. There is no inconsistency between

these two points: race-based faculty assignments have

a causative effect on the racial identiflability of

schools; once that effect has taken place, however,

more than mere faculty desegregation is required to

uproot the segregative impact on pupil attendance patterns

The Board ignores altogether our more basic point that

the explicit racially discriminatory faculty-assignment

policy constitutes direct, insurmountable evidence of

systemwide segregative intent. See note 12, supra.

Optional zones existed at all but one of the six schools

[footnote cont*d]

-26-

curriculum, hardship and disciplinary transfers; tuition

assignments; "intact" busing; and Freedom of Enrollment

transfers — virtually whenever the need arose for

perpetuation of the segregated system. The Board's brick-and

mortar practices had an even more devastating segregative

impact. Almost without exception, all new schools and

additions to existing schools were constructed on a uniracial

basis, literally sealing up the dual system extant at the

time of Brown. Perhaps the most blatant example of

discrimination in the areas of school construction, location

and utilization are the events attending the "closing" of

the old blacks-only Dunbar High School in 1962: the old

Dunbar building was converted into an elementary school

16/ (cont'd)

specifically named by the Board in conjunction with

the assertion that "there has been no gerrymandering

of the boundaries to help whites escape." Board Br. 34.

The creation of optional zones affecting these schools

refutes the Board's assertion. The very origin of

optional zones in the 1952 West Side reorganization also

belies the Board's claim that "the undisputed evidence

is that racial considerations never played a role in

the establishment" of such zones. Board Br. 35. The

use of such optional zones, as well as other pupil-

transfer practices and explicitly racial staff-assignment

policies, demonstrates beyond peradventure that the Dayton

Board did not operate a racially-neutral "neighborhood

school" system free of manipulation." Keyes, 413 U.S.

at 212. -----

-27-

(renamed McFarlane) with attendance boundaries drawn to take

in most of the black students previously attending the

blacks-only Willard and Garfield schools, which were

simultaneously closed; McFarlane opened with an all-black

faculty and an all-black pupil population; at the same time,

a newly-constructed Dunbar High School, located in a black

neighborhood far from white residential areas, opened with

a virtually all-black student body and faculty. All in all,

of 24 new schools constructed between 1940 and the time of

trial, 22 opened 90% or more black or 90% or more white;

78 of some 86 additions of regular classroom space were

made to schools 90% or more one race at the time of expansion

(only 9 additions were made to schools less than 90% black

or white); and, the intentional segregative nature of

these practices was highlighted by the coordinate assignment

of staffs to these new schools and additions tailored to the

racial composition of the pupils. These policies and

practices were supplemented by grade structure reorganization

and creation of five middle schools. This history culminated

with the 1972 rescission of a 1971 Board-adopted plan of

systemwide desegregation; the rescission undid operative

administrative action and reimposed segregation on a system-

wide basis.

The Board was operating a dual system at the time of

trial. Plaintiffs' Br. 43-61, 24a-54a.

-28-

IV. SYSTEMWIDE IMPACT

In our opening brief (pp. 63-64 & 65), we said

that "the Board has never... contended that plaintiffs are

not entitled to a remedial plan such as that now in place

if plaintiffs are right about the nature of the violation,"

and that " [a]s we understand the Board's position... if

plaintiffs are correct in their claim of a systemwide violation,

then the plan of desegregation currently in place is as good

a cure as any." Defendants' brief (pp. 39-42) does not

dispute these statements. The Board, therefore, must be

deemed to have waived any defense that the systemwide nature

of the violation (if the Court agrees with our description of

it)had less than a systemwide impact. The Court should

expressly hold that defendants have had ample opportunity

to question the scope of the remedy, but instead they have

elected to stick to their all-or-nothing position that there

has been no systemwide violation.

29-

CONCLUSION

The judgment below is due to be reversed in its

entirety, and the case remanded to the district court to

enter judgment in accordance with the opinion and mandate of

this Court (which should direct entry of a permanent injunction

adopting the plan of desegregation now in effect) and to

conduct such future proceedings as are not inconsistent with

the mandate of this Court (e.g., issues pertaining to the

state defendants, plaintiffs' pending application for costs).

Dated: April 6, 1978

Respectfully submitted

ROBERT A. MURPHY

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

Lawyers' Committee For

PAUL R. DIMOND

O'Brien, Moran and Dimond

210 East Huron Street

Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104

Civil Rights Under Law

520 Woodward Building

733 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005 & Henderson

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

LOUIS R. LUCAS

Ratner, Sugarmon, Lucas,

RICHARD AUSTIN

Suite 1500

First National Bank Bldg

Dayton, Ohio 45402

NATHANIEL R. JONES

NAACP General Counsel

1790 Boardway

New York, N.Y. 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

-30-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned hereby certifies that on this

6th day of April, 1978, he served two copies of the

foregoing Reply Brief on each party, as follows —

by Federal Express to:

DAVID C . GREER

LEO F. KREBS

Bieser, Greer & Landis

8 North Main Street

Dayton, Ohio 45402

by hand delivery to:

JOEL L. SELIG

Room 5724

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

and by first-class mail to:

ARMISTEAD W. GILLIAM, JR.

P.O. Box 1817

Dayton, Ohio 45401

ROY F. MARTIN

1658 State Office Tower

Columbus, Ohio 43215

-31-