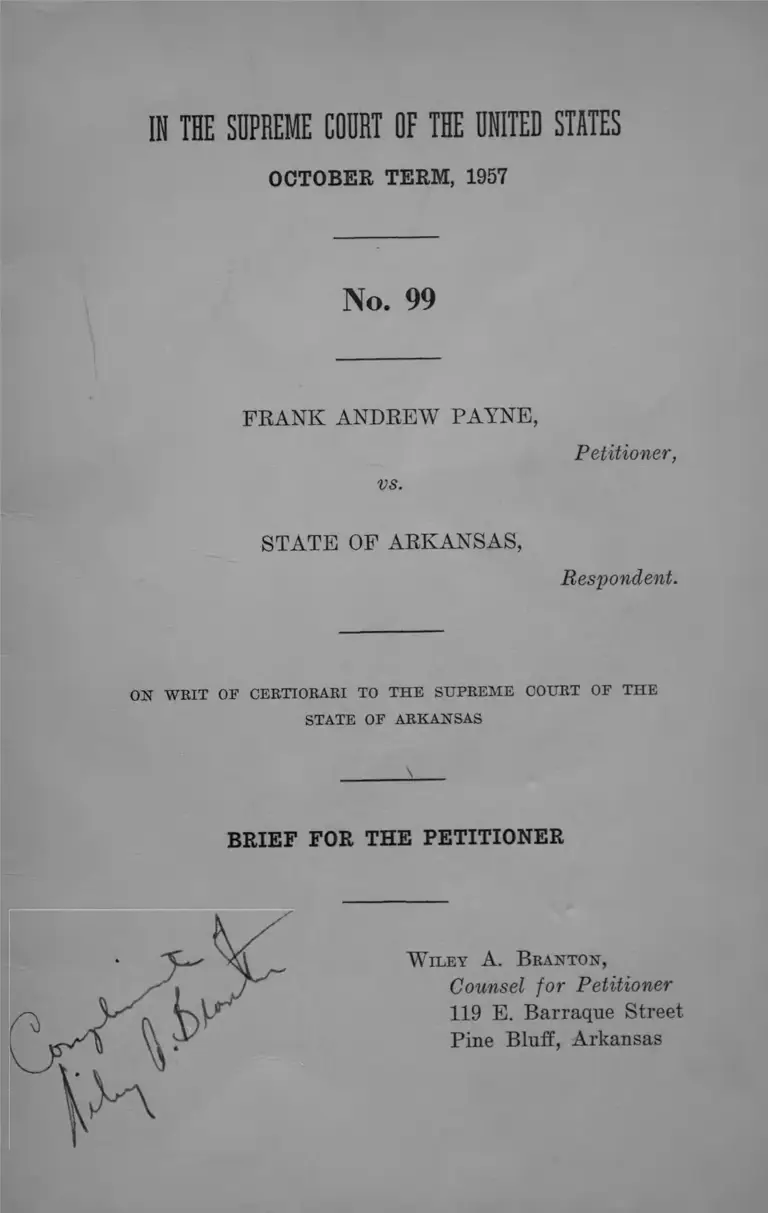

Payne v. Arkansas Brief for the Petitioner

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Payne v. Arkansas Brief for the Petitioner, 1957. fae14cef-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/84da5019-266c-415d-bb6e-ad540ed4a4c3/payne-v-arkansas-brief-for-the-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IK THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1957

No. 99

FRANK ANDREW PAYNE,

Petitioner,

vs.

STATE OF ARKANSAS,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

STATE OF ARKANSAS

\

BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONER

W iley A. B ra n ton ,

Counsel for Petitioner

119 E. Barraque Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

B biep poe t h e P e titio n e e

Opinion Below ............................................................ - 1

Jurisdiction ....................................................................... 1

Statutes Involved .............................. .......................... 2

Constitution of the United States—Fourteenth

Amendment ................................................. 2

Title 18 U.S.C. Sec. 243 ......................................... ~ 2

Ark. Stat. (1947) Sec. 39-201 ................................... 2

Ark. Stat. (1947) Sec. 39-206 ................................... 3

Ark. Stat. (1947) Sec. 39-208 ................... 4

Ark. Stat. (1947) Sec. 39-209 ................................... 4

Ark. Stat. (1947) Sec. 39-210.............. 5

Ark. Stat. (1947) Sec. 39-212....................................... 5

Ark. Stat. (1947) Sec. 39-301.1 .............................. . 5

Ark. Stat. (1947) Sec. 43-601 .................................... 6

Ark. Stat. (1947) Sec. 43-605 .................................... 7

Questions Presented for Review ................................ 7

Statement of the Case ........................................... ..... 8

1. Events which preceded the tr ia l...................... 8

2. Preliminary Motion to Quash Jury Panel....... 8

3. Testimony relating to confession............... 10

4. Petitioner’s defense ............................................. 13

Summary of Argument ................................ 13

I Confession ............................................................ 13

II Jury Discrimination ......... 14

Argument ........................................................................ 15

I Confession—Due Process of Law Guaranteed

by the Fourteenth Amendment Was Denied

to Petitioner by Introduction Into Evidence

After Same Had Been Coerced ........................ 15

Page

II Jury Discrimination—There Was Systematic

Exclusion of Negroes From the Jury Com

mission and From the Jury Panel Where

Negroes Represent Only 4.3% of the Persons

Called for Jury Service for the Past 17 Terms

of Court, Although Negroes Comprise 50% of

the Total Population and 30% of the Elec

i i TABLE OF CONTENTS

torate of the County .......................................... 21

Conclusion ................................................. ..................... 31

CASES CITED

Akins V. Texas, 325 U.S. 398, 89 L.ed. 1692 ............... 27

Ashcraft v. Tenn., 322 U.S. 143 .................................. 16

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 ..................................29, 30

Brown v. Allen (1953), 344 U.S. 443, 73 S.Ct. 397 ..... 29

Brown v. State, 198 Ark. 920, 132 S.W. 2d 1 5 ........... 18

Cassell v. Texas (1950), 339 U.S. 282, 70 S.Ct. 629....27, 28

Chambers v. Fla., 309 U.S. 227 .................. ...............15,16

Commonwealth of Va. v. Bives, 100 U.S. 313, 25

L.ed. 512.......................................... ............ ............... 27

Dewein v. State, 114 Ark. 472, 170 S.W. 582 ............... 18

Fikes v. Ala., 352 U .S .------ , 1 L.ed, 2d 246 ..... ....16, 20, 21

Gallegos v. Nebraska, 342 U.S. 5 5 .............................. 16

Green v. State, 258 S.W. 2d 56 .......................... ,....... 27

Haley v. Ohio, 332 U.S. 596 ................... 16

Harris v. S. C., 338 U.S. 68 ....... 15-16

Hernandez v. Texas (1954), 347 U.S. 475, 74 S.Ct. 667 29

Hill v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400, 62 S.Ct. 1159 ................27, 28

Johnson v. Penn., 340 U.S. 881......................... .......... 21

Leyra v. Denno, 347 U.S. 556 ................................... 16, 20

Lyons v. Okla,, 322 U.S. 596 ........................................20, 21

Malinski v. N. Y., 324 U.S. 401 ................................. 16, 20

McNabb v. V. S., 318 U.S. 332 .................................... 16

Maxwell v. State, 232 S.W. 2d 982 .............................. 27

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587, 55 S.Ct. 579 .......27, 29

Patton v. Miss., 332 U.S. 463, 68 S.Ct. 184 ..............27, 29

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85, 76 S.Ct. 167............... 30

Smith v. State (1951), 218 Ark. 725, 238 S.W. 2d 649 27

Stein v. N. Y., 346 U.S. 156........................................16, 21

Page

Strauder v. W. Va., 100 TT.S. 303, 25 L.ed. 664 ....... 26

Thomas v. Texas, 212 U.S. 278, 53 L.ed. 512............... 27

Turner v. Penn., 338 U.S. 62 ......................................16, 21

U. 8. v. Bayer, 331 U.S. 532 ....................................... 19, 20

Ward v. Texas, 316 U.S. 547 ......................................15,16

Washington v. State (1948), 213 Ark. 218, 210 S.W.

2d 307 .......................................................................... 27

Watts v. Ind., 338 U.S. 4 9 .................... ..... ................... 21

CONSTITUTION

14th Amendment, Constitution of United States —.2, 9,13,

15, 20, 22, 27,31

STATUTES

18 U.S.C. Sec. 243 ......................................... ........... ... 2, 26

Ark. Stat. (1947) 3-227 ......................................... .......9, 29

Ark. Stat. (1947) 39-201 ........................................... 2, 9, 22

Ark. Stat. (1947) 39-206 ............................................... 3, 22

Ark. Stat. (1947) 39-208 ........................................... 4, 9, 22

Ark. Stat. (1947) 39-209 ....... ........................................4, 22

Ark. Stat. (1947) 39-210 .................. ............................ 5, 22

Ark. Stat. (1947) 39-212 ... ........................................... 5,30

Ark. Stat. (1947) 39-301.1 ............................................. 5, 30

Ark. Stat. (1947) 43-403 ............................................... 18

Ark. Stat. (1947) 43-601 .................. ............................ 6,18

Ark. Stat. (1947) 43-605 ..........................................7,16,18

OTHER AUTHORITIES

20 Am. Jur., Evidence, Sec. 482 .................................. 17

III Wigmore, Sec. 855 ............................................... 20

TABLE OF CON TENTS 111

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1957

No. 99

FRANK ANDREW PAYNE,

Petitioner,

vs.

STATE OF ARKANSAS,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

STATE OE ARKANSAS

BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONER

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Arkansas (R. 131)

is reported at 295 S. W. (2d) 312.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Circuit Court of Jefferson County,

Arkansas, was affirmed by the Supreme Court of Arkansas,

on November 5, 1956. Rehearing was denied December 3,

1956. Petition for Writ of Certiorari and Motion for Leave

to Proceed in Forma Pauperis were granted on April 8,

1957. The printed record was received by petitioner’s coun

sel on October 19, 1957. The clerk of this court, pursuant

2

to a request from petitioner under Rule 34 (5), entered an

Order on November 12, 1957, extending the time for peti

tioner to file his Brief to November 25, 1957.

Statutes Involved

C o n stitu tio n of t h e U n it e d S tates—

14th A m e n d m e n t .

All persons bom or naturalized in the United States, and

subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the

United States and of the State wherein they reside. No

State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge

the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United

States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life,

liberty, or property, without due process of law ; nor deny

to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection

of the laws.

T it l e 18 U.S.C. Sec. 243.

Exclusion of jurors on account of race or color.—No

citizen possessing all other qualifications which are or may

be prescribed by law shall be disqualified for service as

grand or petit juror in any court of the United States, or

of any State on account of race, color, or previous condition

of servitude; and whoever, being an officer or other person

charged with any duty in the selection or summoning of

jurors, excludes or fails to summon any citizen for such

cause, shall be fined not more than $5,000. (June 25, 1948,

c. 645, Sec. 1, 62 Stat. 696.)

A r k an sa s S ta tu tes (1947) Sec. 39-201.

Jury Commissioners—Selection— Oath.—Jurors in both

civil and criminal cases shall hereafter be selected as fol

lows : The circuit courts, at their several terms, shall select

3

three (3) jury commissioners, who shall not be related to

one another by blood or marriage within the 4th degree,

who possess the qualifications prescribed for petit jurymen

and who have no suits in court requiring the intervention

of a jury. The judge shall administer to the Commissioners

the following oath: “ You do swear faithfully to discharge

the duties required of you as commissioners; that you will

not, knowingly, select any person as a juror whom you

believe unfit and not qualified; that you will not make known

to anyone the name of the jurors selected by you, and re

ported on your list to the court, until after the commence

ment of the next term of this court; that you will not,

directly or indirectly, converse with any one selected by

you as a juror concerning the merits of any suit to be tried

at the next term of this court until after said cause is tried

or the jury is discharged.” Jury commissioners shall re

ceive $5.00 per day for their services.

A bk an sas S tatu tes (1947) Sec. 39-206.

Preparation of Lists of Grand Jurors and Alternates—

Qualifications.—They shall select from the electors of the

county sixteen (16) persons of good character, of approved

integrity, sound judgment and reasonable information, to

serve at the next term of the court as grand jurors, and

when ordered by the court, shall select such other number as

the court may direct, not to exceed nine (9) electors, having

the same qualifications, for alternate grand jurors, and

make separate lists of the same, specifying in one list the

names of the sixteen (16) persons selected as grand jurors,

and certify the same as the list of grand jurors; and spe

cifying in the other list the names of the alternate grand

jurors, and certifying the same as the list of alternates;

said grand and alternate grand jurors shall be selected

from all parts of the county.

4

Preparation of Lists of Petit Jurors and Alternates—

Indorsement of Lists.—The Commissioners shall also select

from the electors of said county, or from the area con

stituting a division thereof where a county has two or

more districts for the conduct of circuit courts, not less

than twenty-four (24) nor more than thirty-six (36) quali

fied electors, as the Court may direct, having the qualifica

tions prescribed in Section 39-206 Arkansas Statutes 1947

Annotated to serve as petit jurors at the next term of

court; and when ordered by the court, shall select such

other number as the court may direct, not to exceed twelve

(12) electors, having the same qualifications, for alternate

petit jurors, and make separate lists of same, specifying

in the first list the names of petit jurors so selected, and

certify the same as the list of petit jurors; and specifying

in the other list the names of the alternate petit jurors so

selected, and certifying the same as such; and the two (2)

lists so drawn and certified, shall be inclosed, sealed and

endorsed “ list of petit jurors” and delivered to the Court

as specified in Section 39-207, Arkansas Statutes 1947,

Annotated for the list of grand jurors.

A r k a n sa s S ta tu tes (1947) Sec. 39-209.

Delivery of Lists to Clerk—Oath of Clerk and Depu

ties— Oath of Subsequently Appointed Deputy.—The judge

shall deliver the lists to the clerk, in open court, and admin

ister to the clerk and his deputies the following oath: “ You

do swear that you will not open the jury lists now delivered

to you until the time prescribed by law; that you will not,

directly or indirectly, converse with any one selected as a

petit juror concerning any suit pending and for trial in

this (court) at the next term, unless by leave of the court.”

Should the clerk subsequently appoint a deputy in vaca

tion, he shall administer to him the like oath.

A rkansas Statutes (1947) Sec. 39-208.

5

Clerk to Deliver List to Sheriff—Summons by Sheriff—

Return—Day of Appearance.—Within thirty (30) days be

fore the next term, and not before, the clerk shall open

the envelopes and make out a fair copy of the list of

grand jurors, and a fair copy of the list of alternate grand

jurors; also a fair copy of the list of petit jurors, and a fair

copy of the list of alternate petit jurors, and give the same

to the sheriff or his deputy, who shall, at least three (3)

days prior to the first day of the next term, summon the

persons named as grand jurors, and the persons named as

petit jurors and alternate petit jurors, to attend said term

on such day as the court shall have designated by order,

as petit jurors, by giving personal notice to each, or by

leaving a written notice at the juror’s place of residence

with some person over ten (10) years of age. The sheriff

shall return said list, with a statement in writing of the

date and manner in which each juror was summoned:

Provided, That if no day for the appearance of the petit

jurors shall have been fixed by order of court, they shall

be summoned to attend on the second day of the term.

A rk an sa s S tatu tes (1947) Sec. 39-212.

Nonattendance of Juror or Alternate—Fine.—If a juror

or alternate, legally summoned, shall fail to attend, he may

be fined any sum not less than one ($1.00) nor more than

thirty dollars ($30.00).

A rk an sas S tatu tes (1947) Sec. 39-301.1.

Fees of Jurors.—Persons whose names appear on any

legal and authorized Grand Jury or Petit Jury List of the

respective counties of Arkansas, shall receive in addition

to any other fees allowable now by law, other than under

authority of said Act, No. 48 of 1947 (Section 39-301, Ark.

A rkansas Statutes (1947) Sec. 39-210.

6

Statutes, 1947 Official Edition), the following per diem

fees:

a. When such person or persons fail for any reason to

attend court; None.

b. When such person or persons attend court and are

excused by the Court for any reason from serving as

a juror or jurors; Five Dollars ($5.00).

c. When such person or persons have been sworn touch

ing their qualifications to serve as a juror or jurors

and have been accepted by the Court as qualified:

Seven Dollars and Fifty Cents ($7.50).

A rk an sa s S ta tu tes (1947) S ec . 43-601.

Proceeding When No Warrant Issued.—Where an arrest

is made without a warrant, whether by a peace officer or

private person, the defendant shall be forthwith carried

before the most convenient magistrate of the county in

which the arrest is made, and the grounds on which the

arrest was made shall be stated to the magistrate, and

if the offense for which the arrest was made is charged

to have been committed in a different county from that

in which the arrest was made, and the magistrate be

lieves, from the statements made to him on oath, that

there are sufficient grounds for an examination, he shall,

by his written order, commit the defendant to a peace

officer, to be conveyed by him before a magistrate of

the county in which the offense is charged to have been

committed; or, if the offense is a misdemeanor only,

the defendant may give bail before the magistrate for

appearing before a court or magistrate having jurisdiction

to try the offense, on a day to be fixed by the magistrate

and named in the bail-bond.

7

Procedure.— When a person, who has been arrested,

shall be brought, or in pursuance of a bail-bond shall come,

before a magistrate of the county in which the offense is

charged to have been committed, the charge shall be forth

with examined; reasonable time, however, being allowed

for procuring counsel and the attendance of witnesses.

The magistrate before commencing the examination, shall

"state the charge and inquire of the defendant whether

he desires the aid of counsel, and shall allow a reasonable

opportunity for procuring it.

Questions Presented for Review

I

Whether due process of Jaw guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment was denied petitioner—a mentally re

tarded 19 year old Negro youth with little education—

by introduction into evidence of his “ confession” made

following an arrest without a warrant and without arraign

ment before a magistrate and following sustained interro

gation with deprivation of food—punctuated by threats

of mob violence—while he was held incommunicado from

Wednesday morning until Friday afternoon and where

several members of his family were arrested without a

warrant and petitioner was threatened with the arrest of

his mother.

II

Whether members of the Negro race were systematically

excluded or their number limited in the selection of the

jury panel and of the jury commission where no Negroes

had been appointed to jury commission for over fifty

years; where Negroes have represented only 4.3% of the

persons called for jury service for the past 17 consecutive

A bkansas Statutes (1947) Sec. 43-605.

8

terms in a county where Negroes comprise 50% of the

total population and 30% of the qualified electors and

where names were selected from Poll Tax lists on which

the race of the electors is designated.

Statement of the Case

Petitioner has been sentenced to death following con

viction for the crime of Murder In The First Degree (R.

48). The Supreme Court of Arkansas has affirmed this

judgment (R. 131).

1. E ve n ts W h ic h P receded t h e T rial

J. N. Robertson, an elderly white lumber man, was found

dead in his place of business in the City of Pine Bluff,

Arkansas, on Tuesday, October 4, 1955. The petitioner

is a 19 year old1 Negro (R. 98) who actually went to the

fifth grade in school (R. 102) but was promoted to the

seventh grade on an age basis because he was slow learning

(R. 119). The petitioner was arrested on Wednesday

morning, October 5, 1955, by the city police of Pine Bluff

who had no warrant of arrest (R. 63, 112) and held in

communicado under circumstances to be detailed below

until he “ confessed” on Friday afternoon.

2. P r e l im in a r y M otion to Q u a sh t h e J u r y P a n e l

The petitioner filed in proper time, his Motion to Quash

the Panel of petit jurors for the October Term, 1955, of

the Jefferson Circuit Court, alleging that he was a Negro

and that no member of the Negro race had ever been

selected as a jury commissioner in over fifty years in

Jefferson County; and, that although some members of

the Negro race had been called for jury duty since 1947,

1 Petitioner was 19 at the time of the alleged crime.

9

that Negroes have been discriminated against by an arbi

trary and inapportionate limiting of their number by the

jury commissioners in violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

The Arkansas Statutes provide for the appointment of

a three man jury commission by the Circuit Judge prior

to the beginning of each term of court2 and the com

missioners are required to select the panel from the elec

tors of the county.3 The County Clerk keeps the official

record of qualified voters (E. 17) and the record reflects

the race of the elector (E. 18) as is required by law4 and

the total number of voters in the county at the time of

the trial was 19,452 of which, 5,774 were colored and

13,678 were white (E. 18) and this same approximate

ratio has existed for the past three years (E. 18).

According to petitioner’s exhibit No. 1, which was a

certified copy of a population report of Jefferson County

for the year 1950 as prepared by the Census Bureau,

Jefferson County had a total population of 76,075 of which

37,792 were white persons and 37,835 were Negroes (E. 18).

Jury Commissioner Trulock could not recall a Negro

serving as a Jury Commissioner (E. 8), that they were

told to get some Negroes on the panel (E. 9), that he

could not take anybody that he didn’t know and that

he was limited by his knowledge of the people whom he

was trying to select (E. 10), and that he was not per

sonally familiar with very many Negroes who might be

qualified as jurors (E. 11). Neither of the other two

Commissioners could recall a Negro ever having served

2 Ark. Stat., 39-201, Page 2 herein.

3 Ark. Stat., 39-208, Page 4 herein.

4 Ark. Stat., (1947) 3-227 requires that the color of the taxpayer

be shown on the poll tax receipt record.

10

on the Jury Commission (R. 13, 16), and one admitted

that he had race in mind when the panel was selected

(R. 16).

The Circuit Clerk had never known of a Negro serving

on the Jury Commission in Jefferson County (R. 19),

and that he kept a record of the names of persons who

have actually served on jury panels during the past ten

years (R. 19). The Court invited the petitioner’s attorney

to take the stand to show the actual number of Negroes

who have served on jury panels during the past ten

years (R. 22), and his testimony revealed that the number

of Negroes on each panel for the past 17 consecutive terms

of Court has ranged from 0 to 6, the 6 having been reached

at only one term and the average being less than 2 Negroes

per term (R. 24, 25).

Nine Negroes who had formerly served as jurors tes

tified that they had never heard of a Negro serving on

the Jury Commission in Jefferson County and a study

of their testimony reveals that at the time of trial their

average age was 68 years and they had lived in the county

an average of 41 years and most had never served on a

jury until within the past three or four years (R. 28-38).

The Motion to Quash the Jury Panel was denied (R. 43),

and the defendant was tried by an all White Jury (R. 129).5

3. T e st im o n y R el a t in g to C oneession

The State sought to introduce an alleged confession into

evidence and on objection by the petitioner, the Court

and counsel retired to chambers out of the hearing of

the jury where testimony relating to the confession was

5 There were two Negroes on the panel from which petitioner’s

jury was selected but one had died prior to the trial and the other

was excused because he was opposed to capital punishment (R.

129-130).

%

11

had (R. 51). All of the witnesses for the state stated

on direct examination that the defendant was not threat

ened or abused in any manner or promised any reward

in consideration of his confession (R. 51, 63, 72, 76, 79, 84).

The petitioner took the stand in his own behalf (R. 88)

and testified that he was 19 years of age and that he was

arrested about eleven o’clock in the morning on Wednes

day, October 5, 1955, while he was at work at the Bluff

City Lumber Company and that he normally went home

for dinner at twelve o’clock and missed his dinner because

he was in jail and that he was not given any dinner or

supper at the jail on the day of his arrest (R. 88), that

he was awakened about six o’clock the following morning

(Thursday) in order to remove his clothing and shoes

and was then taken by car to Little Rock without break

fast by the Chief of Police and Sgt. Halsell of the State

Police (R. 89); that he was taken to State Police Head

quarters in Little Rock where he was given a lie detector

test and that he was finally given some shoes about 4:30

(R. 89) but the record is silent as to when he was given

clothing and the only food that he was given that day

was a sandwich at one o’clock (R. 89); that he was re

turned to Pine Bluff about six or six-thirty in the after

noon and some time Thursday night was taken to Dumas,

Arkansas,6 by Sgt. Halsell where he was locked up in

jail and kept awake most of the night by the jailer who

questioned him and made threats that petitioner would

be hung (R. 90); that he was given breakfast on Friday

morning about ten-thirty and that other than the sandwich

which he had on Thursday, this was the only food which

he had been given since his arrest on Wednesday morning

(R. 92); that two of his brothers and two of a brother’s

6 Dumas is approximately 45 miles southeast of Pine Bluff in

Desha County.

12

children, ages ten and thirteen were arrested and brought

to the City Jail at Pine Bluff and that the Chief of Police

told Petitioner that he might as well confess or else his

whole family would be arrested including his mother

(R. 93); that later on Friday, Chief Young came to his

cell and told him that there were thirty or forty people

outside who wanted to get the petitioner and that if

he would tell the truth that he (the Chief) would prob

ably keep them from coming in; and that he then went

to the Chief’s office and made a confession (R. 94).

The petitioner’s brother, a 43 year old preacher (R. 86),

testified that he tried to see the petitioner at the City Jail

before Friday but was not permitted to see him (R. 87).

The petitioner’s last teacher testified that he only went

to the fifth grade but that he was promoted to the seventh

grade because he was then fifteen years old and that he

soon dropped out of school (R. 119), and that his grades

were mostly D’s and F ’s (R. 120).

Much of the petitioner’s testimony was corroborated

by the testimony of the State’s witnesses on cross-exami

nation. Sgt. Halsell admitted that the petitioner was

taken to Little Rock without shoes (R. 56), and Chief

Young admitted that petitioner was arrested without a

Warrant (R. 63), that it was possible that petitioner had

no supper on the day of his arrest (R. 64); that he did

not know whether petitioner had breakfast the next morn

ing before being taken to Little Rock (R. 65); that pe

titioner was never taken before a Magistrate or Judge

(R. 65); that petitioner’s relatives would not have been

permitted to see him within 72 hours after his arrest (R.

66-67); that petitioner’s brother and two of his brother’s

children were brought to jail for questioning as well

as another brother and that he told petitioner that there

might be thirty or forty people there in the next few

minutes, just prior to the confession (R. 69).

13

Most of the witnesses for the State were people who

had been brought in merely to witness the signing of the

confession. After the hearing in chambers, the Court

overruled the petitioner’s objection to the admission of

the confession into evidence, and substantially the same

testimony was taken again in the presence of the jury

(B. 102-130). The confession itself begins on page 97 of

the record. The petitioner also took the stand in open

court and stated that profanity was directed at him on

Thursday while in Little Bock and that in returning the

officer told him that if he would tell the truth, that “ the

most you will get out of it is five or six years” on account

of “your age” (B. 124), and that he requested permission

to make a telephone call following his arrest and was told

that he could not call anyone within 72 hours (B. 125).

4. P e t itio n e e ’s D efense

Petitioner took the stand and admitted that he struck

the decedent, his white employer, with an iron bar, which

apparently resulted in his death but that this was done

only after the deceased had struck him following an argu

ment, and that petitioner’s action was done in the sudden

heat of passion.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I

Confession

The introduction into evidence of petitioner’s confession

denied due process of law guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment because it was obtained after the petitioner

had been arrested without a Warrant and held incommuni

cado from Wednesday morning until Friday afternoon,

during which time he was deprived of food for long periods

14

of time and was taken ont of the county to Little Rock

for a lie detector test and was then taken to another city

for safekeeping where he was threatened by the jailer

who told petitioner that “he would be hung.” The pe

titioner was denied the right to consult with a lawyer

or members of his family, and two of his brothers and

three of his nephews were arrested while petitioner was

in the City Jail and the latter was threatened with the

arrest of his whole family including his mother if he

“ didn’t tell the truth.” He was told by the Chief of Police

approximately 30 minutes before his “ formal confession”

that there were 30 or 40 people outside the jail who

wanted to get him and that if petitioner would tell the

truth that he, the Chief, could probably keep them from

getting in. At this point, the petitioner made his incul

patory statement. The totality of the circumstances that

preceded this confession by the nineteen year old mentally

retarded petitioner was a denial of due process.

II

Jury Discrimination

There was systematic exclusion of Negroes from the

jury commission and from the jury panel in Jefferson

County caused by a system of jury selection which relied

wholly upon the jury commissioners’ personal acquaintance,

where commissioners knew few Negroes qualified to serve

in a county where Negroes comprise 50% of the total

population and 30% of the qualified electors and where

the panel is selected from the poll tax record on which

the race of the elector is designated. This system has re

sulted in no Negro serving on the jury commission in

Jefferson County for at least 50 years and where Negroes

have represented only 4.3% of the persons called for jury

service for the past 17 consecutive terms of court and

15

where the petitioner was tried before an all white male

jury and sentenced to death in the electric chair, in vio

lation of the Constitution and laws of the United States.

ARGUMENT

I

Confession

Due process of law guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amend

ment was denied to petitioner, a mentally retarded 19 year

old Negro youth, by introduction into evidence of his “ con

fession” made following an arrest without a Warrant and

prior to any arraignment following sustained interrogation

with deprivation of food—punctuated by threats of mob

violence—while being held incommunicado in jail from

Wednesday morning until Friday afternoon, and where

several members of his family were also arrested without

a Warrant and petitioner was threatened with the arrest

of his mother.

Petitioner contends that his confession was coerced as a

matter of law. Prior to the introduction of the confession,

the trial court properly heard testimony relating to the

voluntary character of the confession out of the hearing of

the jury and the petitioner proved the existence of many

facts which this court frequently has held to be relevant

on the issue of coercion:

That he was a Negro,7 nineteen years of age,8 had a fifth

grade education,9 that he was held incommunicado from

about eleven A. M. on Wednesday, October 5, 1955, until

7 In ascertaining whether a confession is coerced, this Court

gives weight to the fact that defendant is a member of an un

popular racial group. Chambers v. Florida, 309 U.S. 227, 237,

241; Ward v. Texas, 316 U.S. 547, 555; Harris v. South Carolina,

16

about two P. M., on Friday, October 7th, that he was denied

permission to talk to or phone anyone, that relatives were

■denied the right to see him or speak to him and he was not

arraigned,8 9 10 that he was continuously questioned and abused

by officers,11 that he was taken to Little Eock where he was

given a lie detector test and on being returned to Pine

Bluff was offered the hope that if he confessed he would

only get five or six years on account of his age.12 Peti

338 U.S. 68, 70, as part of considering his “ condition in life,”

Gallegos v. Nebraska, 342 U.S. 55, 67. See, Mr. Justice Jackson’s

dissenting opinion in Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U.S. 143, 156, 173.

8 Whether the defendant is mature or immature is important in

evaluating whether a confession has been coerced. Haleu v. Ohio,

332 U.S. 596.

9 The degree of education which a defendant has had is an im

portant factor in evaluating whether a confession has been coerced.

Ward v. Texas, 316 U.S. 547, 555; Harris v. South Carolina, 338

U.S. 68, 70.

10 Holding petitioner incommunicado was not only in violation

of Arkansas law, Sec. 43-605, Arkansas Statutes (1947), but con

trary to the almost universal rule. See Statutes collected in

McNabb v. U. S., 318 U.S. 332, 342, fn. 7. Although there has

been some controversy over whether this alone should vitiate a

confession is at least a serious factor to be weighed because, “ to

delay arraignment, meanwhile holding the suspect incommunicado,

facilitates and usually accompanies use of ‘third degree’ methods.

Therefore (this Court) regards such occurrences as relevant cir

cumstantial evidence in the inquiry as to physical or psychological

coercion.” Stein v. New York, 346 U.S. 156, 187. See also Harris

v. South Carolina, 338 U.S. 68, 71; Turner v. Pennsylvania, 338

U.S. 62, 64; Ward v. Texas, 316 U.S. 547, 555; Ashcraft v. Ten

nessee, 332 U.S. 143, 152; Malinski v. New York, 324 U.S. 401, 412,

417; Turner v. Pennsylvania, 338 U.S. 62, 66, 67; Pikes v. Ala

bama, 352 U .S .------ , 1 L.ed. 2d 246.

11 Continuous interrogation has been deemed an important factor

in evaluating whether a confession has been coerced, Chambers v.

Florida, 309 U.S. 227, 231; Ward v. Texas, 316 U.S. 547, 555;

Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U.S. 143, 154; Haley v. Ohio, 322 U.S.

596, 600; Turner v. Pennsylvania, 338 U.S. 62, 64.

12 A lighter penalty is one of the inducements which was of

fered in Leyra v. Denno, 347 U.S. 556. Mr. Justice Minton wrote,

17

tioner also stated in his testimony that following his arrest

at 11 A. M., on Wednesday, that he was not given any food

until he was given a sandwich in Little Rock at 1 P. M., on

Thursday and that the only other food which he had prior

to the alleged confession on Friday afternoon was his

breakfast about ten thirty Friday morning in Dumas (R.

92).

It is universally recognized that “ a confession of a

person accused of crime is admissible in evidence against

the accused only if it was freely and voluntarily made,

without duress, fear, or compulsion in its inducement and

with full knowledge of the nature and consequences of the

confession.” 20 Am. Jur. Evidence, Sec. 482. The peti

tioner did not have the mentality or the maturity to under

stand the nature and consequences of his confession.13

All of the surrounding circumstances should be studied

in determining whether or not a confession has been

coerced. “ It has been said that no general rule can be

formulated for determining when a confession is voluntary,

because the character of the inducements held out to a

person must depend very much upon the circumstances of

each case. Where threats of harm, promises of favor or

benefits, infliction of pain, a show of violence, or inquisi

torial methods are used to extort a confession, then the

confession is attributed to such influences. It may be said

at page 585 (concerning the first confession in Leyra): such

“ threats, cajoling, and promises of leniency . . . to induce peti

tioner to confess were soundly condemned by that Court.”

13 The petitioner testified that he was 19 years of age (R. 88)

and that he went to the fifth grade in school (R. 102). Mrs.

S. M. Wimberly, the petitioner’s last teacher, testified that “he

dropped out of school before the term was out, in fact, Frank

was of age and they had to skip him from the fifth grade to the

seventh grade—he was fifteen years of age . . . ” (R. 119) “ They

promoted him on an age basis because he was slow learning— he

was very slow and lazy” (R. 119).

18

also, that in determining whether a confession is voluntary

or not, the Court should look to the whole situation and the

surrounding of the accused.” Dewein v. State, 114 Ark.

472, 170 S.W. 582.14

In reviewing the situation in the instant case, it should

be remembered that the petitioner was arrested without a

Warrant,15 and was never carried before a Magistrate as

required by law,16 either before or after his confession (R.

65), and this deprived the petitioner of the right to be

informed that he could have counsel.17 It has already been

explained, supra, how the petitioner was deprived of food

and this was accompanied by prolonged questioning.18 The

petitioner was taken to Little Rock the morning following

his arrest,19 where he was given a lie detector test (R. 105).

The suggestion of mob violence was raised twice, the first

time by the jailer at Dumas,20 who allegedly told petitioner

14 See Brown v. State, 198 Ark. 920, 132 S.W. 2d 15.

15 This was probably in violation of See. 43-403 of the Ark.

Statutes (1947) as a peace officer may only arrest without a Search

Warrant when there are reasonable grounds for believing that the

person arrested has committed a felony.

16 Ark. Statutes (1947) Sec. 43-601, p. 6 herein.

17 Ark. Statutes (1947) Sec. 43-605, p. 7 herein.

18 The petitioner was questioned on the night of the slaying

(Tuesday) and on Wednesday morning prior to his arrest (R. 64)

and was questioned again Wednesday afternoon and Wednesday

night although the approximate length of time is not in the

record. Petitioner was awakened about six o’clock Thursday morn

ing and taken to Little Rock for questioning and a lie detector test

and returned to Pine Bluff late in the afternoon about dark (R.

124), and was then taken to Dumas (See fn. 20 infra) where

he was kept awake most of the night by the jailer (R. 90, 126)

who questioned him.

19 Little Rock is 45 miles north of Pine Bluff.

20 There is a dispute in the testimony as to when the petitioner

was taken to Dumas. The petitioner contends that it was Thurs

day night before the confession and the police officer contends

that it was on Friday night after the confession.

19

that he, the jailer, would be there when the petitioner

“would be hung” (R. 127), and where references were made

about a colored kid in Mississippi.21 The most serious

threat of mob violence was the one suggested by the Chief

of Police (R. 128, 113, 93) and the petitioner testified that

he was afraid.22

There is no dispute that prior to the defendant’s con

fession that two of his brothers and two of his nephews,

ages 10 and 13, were arrested and brought to the City Jail

(R. 93, 114, 125) and the petitioner was threatened with

the arrest of his mother and his entire family “ if I didn’t

tell the truth” (R. 93, 125).

The trial court and the Supreme Court of Arkansas

concluded that because “ Several witnesses were present

when the confession was made and they all testified that

“ at no time, were there any threats . . . ” of petitioner

(R. 133), that the confession was voluntarily given. Most

of these witnesses, however, were people who were brought

in for the sole purpose of witnessing the formal confession

(R. 53) and none of them knew anything concerning the

treatment accorded the petitioner prior to that time (R. 77,

81, 85). The confession which was admitted into evidence

was made by the petitioner within approximately thirty

minutes following his inculpatory statements to the Chief

of Police (R. 69, 77, 108) and was made at a time when he

was laboring under the crushing burden of having already

confessed.23 There had been no significant change in peti

21 This was probably in reference to the atrocious slaying of

Emmitt Till near Money, Mississippi, which was in the news.

22 The petitioner mentions the threat at Dumas and Chief Young’s

threat about “ thirty or forty people outside” as the thing that

made him afraid and caused him to confess (R. 128).

23 As Mr. Justice Jackson wrote in TJ. 8. v. Bayer, 331 U.S. 532,

540, once an accused has confessed, “no matter what the induce

ment, he is never thereafter free of the psychological and practical

20

tioner’s situation from the time of his inculpatory state

ments until his formal confession and such a confession

remains coerced as a matter of law unless the State comes

forward to overcome the presumption created by the facts.

Mr. Justice Minton stated the general rule when he wrote:

“As in the case of other forms of coercion and induce

ment, once a promise of leniency is made a presump

tion arises that it continues to operate on the mind of

the accused. But a showing of a variety of circum

stances can overcome that presumption. The length

of time elapsing between the promise and the confes

sion, the apparent authority of the person making the

promise, whether the confession is made to the same

person who offered leniency and the explicitness and

persuasiveness of the inducement are among the many

factors to be weighed.” Leyra v. Denno, 347 U.S. 556,

588.24

A study of all the surrounding facts in this case should

lead to the conclusion that not only was the alleged confes

sion not voluntarily made but that the petitioner was

denied due process of law in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment to our Federal Constitution.25 Even in cases

disadvantages of having confessed.” In V. 8. v. Bayer, the Court

weighed a time lapse of six months and concluded that this length

of time in conjunction with only a modicum of restraint vitiated a

previous inducement to confess. See Mr. Justice Butledge’s con

curring opinion in Malinski v. New York, 324 U.S. 401, 420, 428;

Mr. Justice Murphy’s dissenting opinion in Lyons v. Oklahoma, 322

U.S. 596, 605, 606.

24III Wigmore Sec. 855, states: “ . . . the general principle is

universally conceded that the subsequent ending of an improper

inducement must be shown-, i.e. it is assumed to have continued

until the contrary is shown.” (Italics in original.)

25 The factual situation in Fikes v. Alabama, 352 U.S. -------,

1 L.ed. 2d 246 is very similar to the factual situation in the

case at bar and there the Court stated that “the totality of the

21

where the Court has upheld the admission of the confes

sion, they look to all the surrounding circumstances. In

Stein v. New York, 346 U.S. 156 at page 185, the Court

said:

“ The limits in any case depend upon a weighing of the

circumstances of pressure against the power of resist

ance of the person confessing. What would he over

powering to the weak of will or mind, might be utterly

ineffective against an experienced criminal.” 26

Because of the introduction into evidence of the peti

tioner’s coerced confession, the judgment below should not

be allowed to stand.

II

Jury Discrimination

The petitioner is a Negro and members of the Negro

race were systematically excluded or their number limited

in the selection of the jury panel and of the jury com

mission where no Negro had ever been appointed to the

jury commission and where Negroes have represented

only 4.3% of the persons called for jury service for the

past 17 consecutive terms in a County where Negroes

comprise 50% of the total population and 30% of the

qualified electors and where names were selected from

poll tax lists on which the race of the elector is shown.

circumstances that preceded the confessions in this case goes be

yond the allowable limits. The use of the confessions secured

in this setting was a denial of due process.” See also Turner v.

Pennsylvania, 338 U.S. 62 and Johnson v. Pennsylvania, 340 U.S.

881.

26 This same standard has been followed in other cases. Pikes

v. Alabama, 352 U .S .-------, 1 L.ed. 2d 246; Watts v. Indiana, 338

U.S. 49; Lyons v. Oklahoma, 322 U.S. 596.

22

The Arkansas Statutes provide for the appointment of

a three man jury commission by the Circuit Judge at

each term27 and this commission is charged with the re

sponsibility of selecting from the electors of the County

a list of grand jurors28 and petit jurors.29 The jurors are

to be selected from the electors and should be persons

“ of good character, of approved integrity, sound judgment

and reasonable information.” The jury commission turns

the list over to the Circuit Judge who delivers it to the

Clerk30 and the latter delivers it to the sheriff within 30

days before the next term of court whose duty it is to

summons the persons named to attend Court for jury

service.31

The petitioner filed in proper time his Motion to Quash

the Panel of Petit Jurors for the October Term, 1955, of

the Jefferson Circuit Court (R. 2) and alleged that he

was a member of the Negro race and a resident of Jeffer

son County, Arkansas and that no member of the Negro

race had been selected as a jury commissioner in over

fifty years in Jefferson County; and, that although some

members of the Negro race had been called for jury duty

in the County since 1947, “ that Negroes have been dis

criminated against by an arbitrary and inapportionate

limiting of their number by the jury commissioners who

have not sufficiently acquainted themselves with the qualifi

cations of all potential jurors, and that this was in vio

lation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States.

27 Ark. Stat. 39-201, p. 2 herein.

28 Ark. Stat. 39-206, p. 3 herein.

29 Ark. Stat. 39-208, p. 4 herein.

30 Ark. Stat. 39-209, p. 4 herein.

31 Ark. Stat. 39-210, p. 5 herein.

23

The petitioner called several witnesses in support of his

Motion to Quash the Panel of Petit Jurors. The three

present jury commissioners either did not know or had

never heard of a Negro serving as a jury commissioner;

the County Clerk, Allen Sheppard, answered “ No” when

asked if he had ever known of a Negro to serve on a

jury commission (E. 17); the Circuit Clerk, M.. V. Mead,

testified that he had lived in Jefferson County for 59 years,

had been Circuit Clerk 12 or 13 years and was County

Judge and served as a deputy in the Sheriff’s office for

several years prior to that (R. 19), and that he could

not remember a Negro having ever served on the Jury

Commission in Jefferson County. Of nine Negro witnesses

who had formerly served as jurors in Jefferson County,

none could remember any Negro having ever served as

a jury commissioner. This undisputed testimony showed

conclusively that Negroes have been systematically ex

cluded from serving as jury commissioners in Jefferson

County and the Motion to Quash the Jury Panel should

have been granted for that reason.

The petitioner alleged in paragraph 23 of his Motion

to Quash the Jury Panel (E. 5) that prior to the March,

1947, term of the Jefferson Circuit Court, not a single

Negro had been called for jury service in more than 50

years. As proof of that fact, the petitioner introduced

as Exhibit No. 3 to his Motion to Quash the Jury Panel,

a Motion to Quash the Panel of Petit Jurors which was

filed in the Jefferson Circuit Court on March 27, 1947,

in a case then pending, styled, State of Arkansas v. Albert

Wilkerson, et al. (E. 38). The essence of the motion was

that no Negro had served on a jury for many years and

that there was an unlawful discrimination against Negroes

by excluding them from jury service. The docket entry

in the Circuit Clerk’s office shows that the Motion was

granted in the Wilkerson case and the panel quashed

(E. 43).

24

Petitioner’s Exhibit Number 1 to this motion consisted

of a certified c o p y of the 1950 census report of Jefferson

County, Arkansas, as prepared by the IT. S. Census Bureau

and showed the total population of Jefferson County in

1950 to be 76,075, classified as follows :

Native Born

White ................. 37,792 Negroes ................. 37,835

Foreign Born

White ................. 360 Other Races ......... 88

Allen Sheppard, County Clerk, testified that he kept

the official record of the qualified voters within Jefferson

County and that the race of the taxpayer is reflected

therein (R. 17). He testified further that he had made

an actual count to determine the number of white and

colored qualified electors in Jefferson County for the past

three years which revealed the following information:

Year Total No. Electors No. White No. Colored

1953 ................ 18,315 12,674 5,641

1954 ................ 18,887 13,157 5,730

1955 ................ 19,452 13,678 5,774

M. Y. Mead, the Circuit Clerk, testified that he kept a

record of the names of persons who had actually served

on jury panels in Jefferson County and the said record

was produced in the hearing on this motion (R. 19). The

petitioner attempted to prove the total number of Negroes

who had served on the jury panel in the County since

1947 by Henry Albright, a deputy sheriff. Mr. Albright

testified that he had been a deputy sheriff in Jefferson

County for about 18 years and that he did not think that

there had been a single Negro juror that he did not know

personally (R. 21). The Court objected to the petitioner’s

request that Mr. Albright look at the record of jurors

from the Clerk’s office and pick out by name those persons

25

whom he knew to he Negroes (E. 22), on the grounds

that it would unduly delay the trial. Upon the suggestion

of the trial judge (E. 22), the proof sought by Mr. Al

bright’s testimony was made by Counsel for the defendant,

who had already examined the jury record in the Clerk’s

office.

Wiley A. Branton, attorney for the petitioner, testified

in the hearing on the Motion to Quash the Jury Panel

that he had lived in Jefferson County for all of his 32

years and had been active in political and civic matters,

had visited the Courts frequently, and felt that he was

qualified by knowledge to ascertain what persons were

Negroes by looking at the names on the jury record in

the Clerk’s office (E. 23). He testified further that he had

examined the said jury record and found the following

information:

Term of Court

October, 1947

March, 1948

October, 1948

March, 1949

October, 1949

March, 1950

October, 1950

March, 1951

October, 1951

March, 1952

October, 1952

March, 1953

October, 1953

March, 1954

October, 1954

March, 1955

October, 1955

Total No. Jurors

..... 31

..... 31

..... 38

..... 24

..... 32

..... 64

..... 29

..... 54

..... 35

..... 31

..... 50

..... 42

...... 46

...... 25

...... 39

...... 40

...... 58

...... 669

Total No. Negroes

2

0

1

2

2

1

0

2

1

2

1

2

6

1

0

4

2

29T o t a l

26

Based on the figures just cited, although Negroes com

prise 50% of the total population of Jefferson County

and 30% of the qualified electors, Negroes have repre

sented only 4.3% of the persons called for jury service

for the past 17 consecutive terms of the Jefferson Circuit

Court. The highest number of Negroes ever called for

any term of Court was 6 in the October Term, 1953, and

this number only represented 13% of the total number

called. The petitioner contended in paragraph 22 of his

Motion to Quash the Jury Panel that only 23 different

Negroes had ever been called for jury service and that

more than half of those were over the age of 65 years

(R. 4). As proof of that fact, 9 Negroes who had formerly

served as jurors testified in the hearing on the motion

and the average age of the 9 jurors was 68 years and

they had lived in the County an average of 41 years. Most

testified that they had never served on a jury until within

the past 3 or 4 years and 5 of the 9 have served during

more than one term of Court (R. 26-36). Of the 2 Negroes

on the present panel, one had died prior to the trial and

the other was excused for cause. The defendant was tried

by an all white male jury (R. 129).

Congress has expressly provided that no citizen pos

sessing all other qualifications shall be disqualified for

service as a juror in any court on account of race or

color.32 The Supreme Court of the United States has held

that “ the constitution of juries is a very essential part of

the protection such a mode of trial is intended to secure.

Strauder v. West Virginia (1880), 100 U.S. 303, 25 Law

Ed. 664. If there is a denial of the right of Negroes to

serve on juries because of their color, then there has been

32 See Title 18 U.S.C., See. 243.

27

a denial of equal protection of laws as guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment.33

Since the rulings relating to discrimination on account of

race apply to grand juries as well as petit juries, the same

ruling should, a fortiorari, apply to the jury commissioners

who are charged with the selection of jurors.

The petitioner does not contend that he is entitled to

proportional representation or that he is entitled to have a

member of his race on the panel or even on the jury that'

tries him.34 This court restated the principle that propor

tional racial representation was not required in Cassell v.

Texas (1950), 339 U.S. 282, 70 Supreme Court 629 in

which it stated:

“ Discrimination can arise from the action of Commis

sioners who exclude all Negroes whom they do not

know to be qualified and who neither know nor seek

to learn whether there are in fact any qualified to

serve. In such a case discrimination necessarily re

sults where there are qualified Negroes available for

jury service. With the large number of colored male

residents of the County who are literate, and in the

absence of any countervailing testimony, there is no

room for inference that there are not among them

householders of good moral character, who can read

33 gee:—HiU v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400, 62 S.Ct. 1159; Patton v.

Mississippi, 332 U.S. 463, 68 Supreme Court 184; Norris v. Ala

bama, 294 U.S. 587, 55 Supreme Court 579. This same ruling has

also been followed by the Supreme Court of Arkansas. Maxwell

v. State, 232 S.W. 2d 982; Green v. State, 258 S.W. 2d 56.

34 This Court has held that proportional representation is not

required. See: Commonwealth of Virginia v. Rives, 100 U.S. 313,

322 25 Law Ed. 667, 670; Thomas v. Texas, 212 U.S. 278, 282, 53

Law Ed. 512, 513; Akins v. Texas, 325 U.S. 398, 404, 89 Law Ed.

1692 The Arkansas Supreme Court has followed this same view in

Washington v. State (1948), 213 Ark. 218, 210 S.W. 2d 307 and in

Smith v. State (1951), 218 Ark. 725, 238 S.W. 2d 649.

28

and write, qualified and available for grand jury ser

vice.” 35

The effect of the testimony of jury commissioners Tru-

lock,36 Bobo37 and Williams38 is to bring the case squarely

within the holding in Cassell v. Texas, supra in which Mr.

Justice Reed stated at page 289, “When the commissioners

were appointed . . . it was their duty to familiarize them

selves fairly with the qualifications of the eligible jurors

. . . without regard to race and color. They did not do so

here, and the result has been racial discrimination.”

The petitioner contends that while the jury commission

has gone about to systematically include a few Negroes on

the panel, they have done so in such a manner as to fur

ther discriminate against the Negro by restricting the num-

35 The Court was quoting from Hill v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400, 404,

62 Supreme Court 1159, 1161.

36 (R. 9) “A. . . . I felt that in the selection of a jury I could

not take anybody that I didn’t know. He might be a better qualified

man than the one I would call, but still I wouldn’t know it, so I

was limited again by my knowledge of the people whom I was

trying to select . . .

Q. Mr. Truloek, state whether or not you are personally familiar

with very many Negroes in this County who might be qualified as

jurors? A. I don’t think I am sir.”

37 (R. 14) “ Q. Mr. Bobo, how broad is your knowledge of Negroes

in this County who would be qualified for jury service in your

opinion? A. That I couldn’t answer. I know quite a few colored

people. I have been doing business with them quite a while and

I know quite a few. A ll of them wouldn’t be qualified, they don’t

have poll tax receipts, therefore, wouldn’t be eligible for jurors.

We had to go by the list, people who paid their poll tax.”

38 (R. 16) “ Q. Did you have race in mind when you selected the

Negroes for the panel? A. Yes.

Q. Did you feel that there should be some on the panel? A.

Yes.

Q. Did you think it should be on a proportional basis or any

certain number? A. I didn’t give that any thought.

Q. Was anything said as to how many should be on there? A.

Nothing in particular. We decided that we should have some on

each panel. I think we put some on each panel.”

29

ber to such a few that it would be virtually impossible to

actually get a Negro on a particular jury without the ap

proval of the prosecutor, even though there may be Negroes

on the panel.39 40 It should tax the credulity of this court

to say that mere chance resulted in such few Negroes being

called for jury service where 50% of this class make up

the population of Jefferson County and 30% of the qualified

electors."

The situation in Jefferson County, Arkansas, where but

a few Negroes have been called for jury service during the

past 17 terms of court shows a long continued exclusion

and verdicts returned against Negroes by such juries should

not be allowed to stand41 as, “ token summoning of Negroes

for jury service does not comply with equal protection.” 42

It should also be pointed out that it was easy for the jury

com m ission to discriminate against Negroes because they

were furnished with a record of the qualified electors and

the County Clerk testified that such records show the race

of the taxpayer (R. 57).43 “ Obviously that practice makes

it easier for those to discriminate who are of a mind to

discriminate.” 44

39 The state has ten peremptory challenges in a capital case in

Arkansas.

40 In Hernandez v. Texas (1954), 347 U.S. 475, 74 Supreme Court

667, the petitioner established that 14% of the population of

Jackson County were persons with Mexican or Latin American sur

names. The petitioner was of Mexican descent and offered evidence

showing that for the last 25 years there is no record of a person

with a Mexican or Latin American name having served on a jury

commission, grand jury or petit jury in Jackson County. The Court

adopted the “ rule of exclusion” as supplying proof of discrimina

tion as established by Norris v. State of Alabama, 294 U.S. 587, 55

Supreme Court 579.

41 Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U.S. 463, 68 Supreme Court 184.

42 Brown v. Allen (1953), 344 U.S. 443, 73 Supreme Court 397.

43 Ark. Stat. (1947) 3-227 Requires that the race of the tax

payer be shown on the poll tax record.

44 In Avery v. Georgia (1953), 345 U.S. 559, 73 Supreme Court

891, the jury commissioners printed the names of white persons

30

In Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559, the late Chief Justice

Vinson held the system used there unconstitutional because

it facilitated discrimination and because the commissioners

did not follow a nondiscriminatory course of conduct. The

characteristics which condemned the system in the Avery

case also doomed the system here. They make discrimina

tion easier and require following a course of conduct which

operates to discriminate.

The trial court implied that the jury commission has

selected many colored people who at their request the

court has excused and that their names do not show on the

payroll record because they don’t draw pay (E. 25) and

the Supreme Court of Arkansas, gave weight to this factor

when it said “ On the other hand it was shown that many

others, the numbers undisclosed, had been selected but had

not served for different reasons” (E. 138). All jurors are

required under the Arkansas law to attend Court in an

swer to the summons by the Sheriff,45 under penalty of a

fine and if they attend and are then excused from serving

for any cause they are still entitled to a fee of $5.00 even

though they do not serve.46 Therefore, the payroll record

was probably an accurate record of all Negroes who had

been called for jury service.

In any event, the whole of petitioner’s evidence in con

nection with his Motion to Quash the Jury Panel went un

contradicted by the State and therefore should have been

granted.47

on white tickets and of Negroes on yellow tickets, and placed

them in a box, however, no Negro names were ever drawn from

the box.

43 Ark. Stat. 1947, 39-212 p. 5 herein.

^ Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85, 76 Supreme Court 167.

46 Ark. Stat. 1947, 39-301.1 p. 5 herein.

31

CONCLUSION

The petitioner has set forth in his argument a number of

events which should show that his confession was coerced

and that he was denied due process of law in violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution by the in

troduction of the confession into evidence against him and

that his conviction which followed should not be allowed to

stand. The petitioner has also made as strong a showing

as he possibly could that members of his race were discrimi

nated against in the selection of the jury commission and of

the petit jury panel at the time of his trial and for many

years prior thereto.

Therefore, because of the denial of each of the constitu

tional rights complained of in this Brief, the petitioner sub-

' mits that the judgment below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

W il e y A. B r a h t o n

119 E. Barraque Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

Counsel for Petitioner

*