McIntosh v. Arkansas Republican Party -- Fank White Election Committee Brief of Appellant

Public Court Documents

July 2, 1984

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McIntosh v. Arkansas Republican Party -- Fank White Election Committee Brief of Appellant, 1984. 8a449296-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/84e72873-03ae-403a-b3c1-8a5483fcda27/mcintosh-v-arkansas-republican-party-fank-white-election-committee-brief-of-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

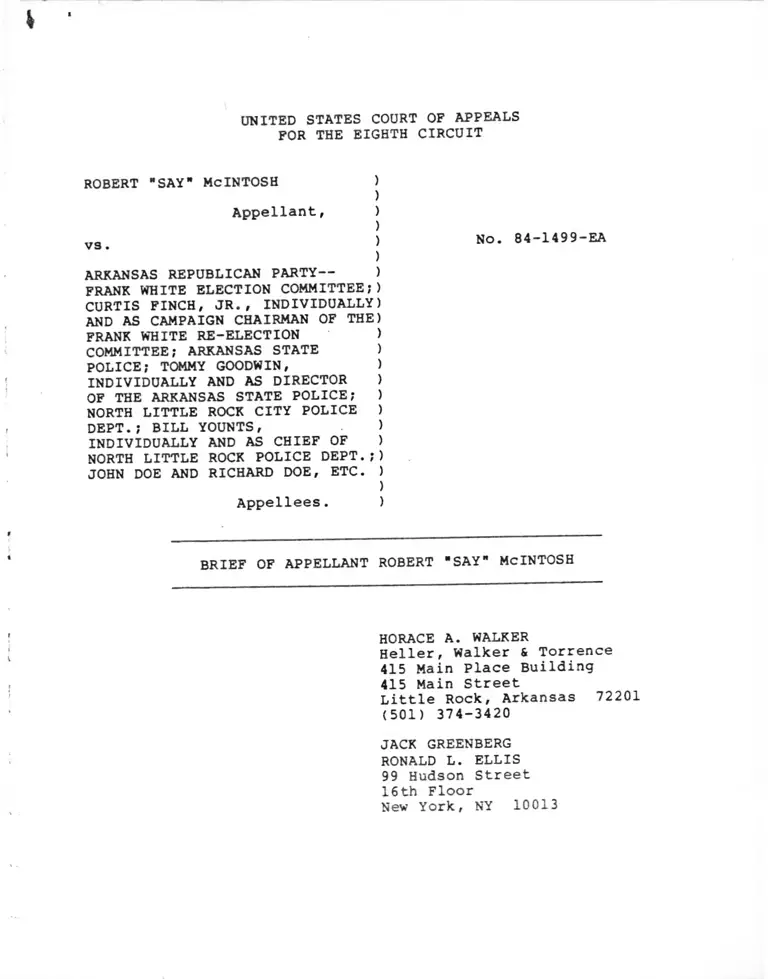

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

ROBERT "SAY" McINTOSH )

)

Appellant, )

)vg ) No. 84-1499-EA

)

ARKANSAS REPUBLICAN PARTY— )

FRANK WHITE ELECTION COMMITTEE;)

CURTIS FINCH, JR., INDIVIDUALLY)

AND AS CAMPAIGN CHAIRMAN OF THE)

FRANK WHITE RE-ELECTION )

COMMITTEE; ARKANSAS STATE )

POLICE; TOMMY GOODWIN, )

INDIVIDUALLY AND AS DIRECTOR )

OF THE ARKANSAS STATE POLICE; )

NORTH LITTLE ROCK CITY POLICE )

DEPT.; BILL YOUNTS, )

INDIVIDUALLY AND AS CHIEF OF )

NORTH LITTLE ROCK POLICE DEPT.;)

JOHN DOE AND RICHARD DOE, ETC. )

)

Appellees. )

BRIEF OF APPELLANT ROBERT "SAY" McINTOSH

HORACE A. WALKER

Heller, Walker & Torrence

415 Main Place Building

415 Main Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

(501) 374-3420

JACK GREENBERG

RONALD L. ELLIS

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

T

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

ROBERT "SAY" McINTOSH )

)

Appellant, )

)

vs. ) No. 84-1499-EA

)

ARKANSAS REPUBLICAN PARTY— )

FRANK WHITE ELECTION COMMITTEE;)

CURTIS FINCH, JR., INDIVIDUALLY)

AND AS CAMPAIGN CHAIRMAN OF THE)

FRANK WHITE RE-ELECTION )

COMMITTEE; ARKANSAS STATE )

POLICE; TOMMY GOODWIN, )

INDIVIDUALLY AND AS DIRECTOR )

OF THE ARKANSAS STATE POLICE; )

NORTH LITTLE ROCK CITY POLICE )

DEPT.; BILL YOUNTS, )

INDIVIDUALLY AND AS CHIEF OF )

NORTH LITTLE ROCK POLICE DEPT.;)

JOHN DOE AND RICHARD DOE, ETC. )

)

Appellees . )

BRIEF OF APPELLANT ROBERT "SAY" McINTOSH

HORACE A. WALKER

Heller, Walker & Torrence

415 Main Place Building

415 Main Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

(501) 374-3420

JACK GREENBERG

RONALD L. ELLIS

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

REQUEST FOR ORAL ARGUMENT

Oral argument would be helpful in this case since impor

tant issues concerning the constitutional rights are presented.

The Court before makes a ruling concerning appellant's denial of

admission to the fund-raising appreciation luncheon as a result

of exercising his First Amendment rights of free expression, and

whether the appellee's had probable cause and acted in good faith

in arresting appellant for disorderly conduct after he sought

admittance to the fund-raising luncheon. To properly address

these issues, appellant respectfully requests thirty (30) minutes

to argue and clarify the issues on appeal.

t

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Request for Oral Argument i

Table of Contents ii

Table of Authorities Cited iii, iv

Preliminary Statement v

Statement of Issues vi, vii

Statement of the Case viii, ix, x

Argument

I. APPELLANT'S FIRST AMENDMENT RIGHT OF FREE

EXPRESSION WAS ABRIDGED WHEN HE WAS UNLAWFULLY

DETAINED AND PREVENTED FROM ATTENDING THE

APPRECIATION LUNCHEON 1

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FINDING THAT

THE STATE POLICE OFFICERS ACTED REASONABLY

AND IN GOOD FAITH AND THAT THEY HAD PROBABLE

CAUSE TO ARREST APPELLANT FOR DISORDERLY CONDUCT 14

Conclusion 19

Certificate of Service 20

District Court Opinion Appendix

ii

f

TA3LE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

Page

Bachella v. Maryland,

397 U.S. 564, 567 (1970) 3

Beck v. Ohio,

379 U.S. 89, 99 (1964) 15

Brown v. Hartlage,

456 U.S. 45, 47 (1982) 5, 6

Brown v. Louisiana,

383 U.S. 131 (1966) 11

Buckley v. Valeo,

424 U.S. 1 (1976) 6, 12

Caplinsky v. New Hampshire,

315 U.S. 568, 571 (1942) 5

Cohen v. California,

403 U.S. 15, 22 (1971) 3, 10, 12

Cox v. Louisiana,

379 U.S. 536 (1965) 9

Dunaway v. State of New York,

442 U.S. 200 (1979) 14

Edwards v. South Carolina,

372 U.S. 229 (1963) 9

Houser v. Hill,

278 F. Supp. 920, 928 (M.D. Ala. 1968) 5

Hudgens v. NLRB,

424 U.S. 507, 526 (1976) 3

James v. Board of Educational of Central Dist. No. 1 ,

461 F.2d 566, 575 (2nd Cir. 1972) 11

McIntosh v. Frank White, et al,

582 F. Supp. 1244, 1248 (E.D. Ark. 1984) 2

Murdock v. Penn.,

319 U.S. 105, 108 (1943) 4

NAACP v. Alabama ,

377 U.S. 288, 307 (1964) 9, 12

iii

NAACP v. Button,

371 U.S. 415, 429 (1963)

NAACP v. Clairborne,

458 U.S. 886, 993 (1982) 8,

Nesmith v. Alford,

318 F .2d 110, 119 (5th Cir. 1963) reh.

denied, 319 F.2d 859 (5th Cir. 1963),

cert, denied, 375 U.S. 945

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan,

376 U.S. 254, 265 (1964) 1, 5, 8,

Norwood v. Harrison,

413 U.S. 455 (1973)

Perkins v. Cross,

562 F. Supp. 85, 87 (E.D. Ark. 1983) 15,

Speiser v. Randall,

357 U.S. 513, 518 (1958) 4

Spence v. Washington,

418 U.S. 405 (1974) 3, 11,

Stromberq v. California,

283 U.S. 359, 369 (1930)

Terminiello v . Chicago,

337 U.S. 1, 4 (1979)

Thornhill v. Alabama,

310 U.S. 88 (1940)

Tinker v. Des Moines School District,

393 U.S. 503, 508 (1969 )

U.S. v. Barber,

557 F .2d 628 (8th Cir. 1977 )

U.S. v. Ganter,

436 F .2d 364 (7th Cir . 1970)

U.S. v. Strickland

490 F .2d 378 (9th Cir . 1974 )

Virginia Pharmacy Board v.

Virginia Citizens Consumer Council,

425 U.S. 748 (1976)

West Virginia Stat e Board of Education

319 U.S. 624, 639 (1943)

12

12

16

11

5

17

6

12

7

8

9

12

14

14

14

5

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

The Honorable Henry Woods, United States District Judge

for the Eastern District of Arkansas, rendered the decision

appealed from. Robert "Say" McIntosh v. Frank White, et al, No.

LR-C-82-153 .

The grounds on which jurisdiction of the Court appealed

from was invoked pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1982, 1983, 1985,

1986, 1988 and the First, Fourth, Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments

to the United States Constitution.

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. § 1291 appeal from a final order of a district court. The

district court's memorandum opinion and final judgment was

entered on March 19, 1984. See McIntosh v, Frank White, et al,

582 F. Supp. 1244 (E.D. Ark. 1984). Appellant filed notice of

appeal on April 16, 1984.

v

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

I. APPELLANT'S FIRST AMENDMENT RIGHT OF FREE

EXPRESSION WAS ABRIDGED WHEN HE WAS UNLAWFULLY

DETAINED AND PREVENTED FROM ATTENDING THE

APPRECIATION LUNCHEON

Bachella v. Maryland,

397 U.S. 564, 567 (1970)

Brown v. Hartlage,

456 U.S. 45, 47 (1982)

Brown v. Louisiana,

383 U.S. 131 (1966)

Buckley v. Valeo,

424 U.S. 1 (1976)

Caplinsky v. New Hampshire,

315 U.S. 568, 571 (1942)

Cohen v. California,

403 U.S. 15, 22 (1971)

Cox v. Louisiana,

379 U.S. 536 (1965)

Edwards v. South Carolina,

372 U.S. 229 (1963)

Houser v . Hill,

278 F. Supp. 920, 928 (M.D. Ala. 1968)

Hudgens v. NLRB,

424 U.S. 507, 526 (1976)

James v. Board of Educational of Central Dist. No. 1 ,

461 F .2d 566, 575 (2nd Cir. 1972)

McIntosh v. Frank White, et al,

582 F. Supp. 1244, 1248 (E.D. Ark. 1984)

Murdock v . Penn. ,

319 U.S. 105, 108 (1943 )

NAACP v. Alabama,

377 U.S. 288, 307 (1964 )

NAACP v. Button,

371 U.S. 415, 429 (1963 )

NAACP v. Cla i rbor ne ,

458 U.S. 886, 993 (1982)

vi

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan,

376 U.S. 254, 265 (1964)

Norwood v. Harrison,

413 U.S. 455 (1973)

Speiser v. Randall,

357 U.S. 513, 518 (1958)

Spence v. Washington,

418 U.S. 405 (1974)

Stromberg v. California,

283 U.S. 359, 369 (1930)

Terminiello v, Chicago,

337 U.S. 1, 4 (1979)

Thornhill v. Alabama,

310 U.S. 88 (19473 )

Tinker v. Des Moines School District,

393 U.S. 503, 508 (1969)

Virginia Pharmacy Board v.

Virginia Citizens Consumer Council,

425 U.S. 748 (1976)

West Virginia State Board of Education v, Barnett,

319 U.S. 624, 639 (1943)

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FINDING THAT

THE STATE POLICE OFFICERS ACTED REASONABLY

AND IN GOOD FAITH AND THAT THEY HAD PROBABLE

CAUSE TO ARREST APPELLANT FOR DISORDERLY CONDUCT

Beck v. Ohio,

379 U.S. 89, 99 (1964)

Dunaway v. State of New York,

442 U.S. 200 (1979)

Nesmith v. Alford,

318 F .2d 110, 119 (5th Cir. 1963) reh.

denied, 319 F.2d 859 (5th Cir. 1963),

cert. denied, 375 U.S. 945

Perkins v. Cross,

562 F. Supp. 85, 87 (E.D. Ark. 1983)

U.S. v. Barber,

557 F .2d 628 (8th Cir. 1977)

U.S._v._Ganter ,

436 F.2d 364 (7th Cir. 1970)

U.S. v. Strickland,

490 F .2d 378 (9th Cir. 1974)

VI 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This appeal comes to this Court from a final order and

judgment rendered on March 19, 1984 in the United States District

Court, Eastern District of Arkansas, Western Division, by the

Honorable Henry Woods. The issues presented for review are (1)

Appellant's First Amendment right of free expression was abridged

when he was unlawfully detained and prevented from attending the

appreciation luncheon; and (2) The District Court erred in

finding that the State Police officers acted reasonably and in

good faith and that they had probable cause to arrest appellant

for disorderly conduct.

Suit was originally commenced in this action on March 1,

1982 and an amended complaint was filed July 20 , 1982 . The

complaint alleges that appellant's constitutional rights were

violated under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1982, 1983, 1985, 1986, 1988,

the First, Fourth, Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United

States Constitutional after being denied entrance to the then

Governor Frank White appreciation luncheon, and his arrest for

disorderly conduct.

Appellant McIntosh is a black United States citizen and

a resident of Little Rock, Arkansas. On or about February 25,

1982, appellant along with Reverand Daniel Bowman, purchased a

$125 ticket to attend an appreciation luncheon that was given for

then Governor of the State of Arkansas Frank White. The luncheon

was scheduled at the Little Rock Convention Center at noon on

February 26, 1982. The luncheon was designed as a local fund

raiser and was organized and financed the Frank White re-election

viii

campaign committee and the Arkansas Republican party and was

opened to all persons who were willing to purchase a $125 ticket

to attend. Appellant was a member of the Republican party at the

time and purchased a ticket so that he could attend the function

along with other ticket holders. Appellant also contacted the

FBI and Secret Service to inform them of his intentions to attend

the fund-raiser and to assure them that he was not going do

anything to disrupt the proceedings and that his manner of dress

would be his only symbol of protest.

On February 26, 1982, appellant appeared at the fund

raising luncheon in a law abiding and orderly manner but was

informed by defendant's Campaign Chairman Curtis Finch and State

Police Officers Jerry Reinold and Barney Phillips of the Arkansas

State Police that his ticket was purchased illegally and that he

would not be allowed to attend the luncheon. None of the other

ticket holders were refused admittance to the fund raising

luncheon as appellant had been refused admittance. Appellant

explained to appellees that he had lawfully purchased his ticket

and expressed his desire to attend the luncheon as all other

ticket holders were allowed to do. As a result of this,

appellant was abruptly arrested, handcuffed, and hauled off to

the North Little Rock Police Station, where he was unlawfully

jailed, interrogated, and detained until the fund-raising affair

was over. Appellant was detained and interrogated for over two

hours before he was charged with any type of criminal offense and

denied access to a telephone to call his attorney and bondsman,

even though he repeatedly asked that he be allowed to do sc. The

Deputy Prosecuting Attorney, Judy Kay Mason, informed appellees

ix

that they could not just hold appellant in a jail without

charging him with any type of offense and that they must either

charge him with an offense or let him out. Appellant was then

charged with disorderly conduct, but the charges were dismissed

by the North Little Rock Municipal Court. The actions of

appellee's in denying appellant admittance to the fund-raising

luncheon in the same manner as the other ticket holders after he

had purchased his ticket to prevent him from exercising his right

of freedom of expression, and unlawfully arresting, jailing and

detaining him were a violation of his constitutional rights.

The case was tried to the Court on March 13 , 1984. By

order and memorandum dated March 19, 1984 the Court dismissed the

complaint of appellant McIntosh with prejudice and entered

judgment in favor of appellees with costs assessed against

appellant. The District Court held that none of the appellees

deprived the appellant of any of his constitutional rights, nor

did any of them violate the law. A copy of the Court's Opinion

is attached as the Appendix to this brief.

Notice of appeal was filed by appellant on April 16,

1984 pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1291 and 2107.

x

ARGUMENT

I. APPELLANT'S FIRST AMENDMENT RIGHT OF FREE

EXPRESSION WAS ABRIDGED WHEN HE WAS UNLAWFULLY

DETAINED AND PREVENTED FROM ATTENDING THE

APPRECIATION LUNCHEON

State Power and The First Amendment

Robert McIntosh dressed as a poor person to symbolize

the economic conditions of the poor in America. Mr. McIntosh was

arrested by state police when attempting to convey his message to

Vice President Bush, Governor Frank White, and other members of

the Republican party at an appreciation luncheon for Governor

White. Mr. McIntosh purchased an admittance ticket to the

luncheon for $125.

Mr. McIntosh's First Amendment rights were violated in

connection with his detention by the State of Arkansas.

the test of state action is not the

forum in which state power has been applied

but whatever the forum, whether such power in

fact has been exercised.

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 265 (1964). Mr.

McIntosh was detained and jailed long enough, by the state

police, to miss his opportunity to either attend the luncheon, or

appear 'symbolically' dressed in the exhibition hall of the muni

cipally owned Little Rock Convention. His detainment away from

the convention center abridged his right to convey his political

and economic message and abridged the right of other Republican

party members to hear McIntosh's message. New York Times, supra.

376 U.S. at 269, Virginia Pharmacy Board v. Virginia Citizens

Consumer Council, 425 U.S. 748 (1976) (upheld the right of con

sumers to make an informed choiced recognizing the value of com

-1-

mercial speech). As a Republican party member, and an executive

officer, Vice President of the Republican party, Tr. at 6, Mr.

McIntosh in a quiet and unobtrusive way attempted to exercise the

highest of his party membership rights for himself and fellow

members of his political party. If the First Amendment protects

anything, it protects political discourse.

The district court summarily dismissed the suit against

Governor Frank White and the Director of the Arkansas State

Police, Tommy Goodwin, and the North Little Rock Police

Department and its Police Chief Bill Younts. Robert "Say"

McIntosh v. Frank White, et al, 582 F. Supp. 1244, 1248 (E.D.

Ark. 1984). The district court's decision was based on its

conclusion that neither Finch nor White ordered the arrest of

McIntosh. The testimony elicited from Mr. Finch, Chairperson of

the Frank White Re-election Campaign, shows that the presence of

McIntosh at the luncheon and the cash purchase of his ticket were

discussed with Governor White bef ore McIntosh appeared at the

luncheon:

Finch: I was notified that McIntosh had— had

sent a message to the Governor, . . . and

advising him that he was going to speak at the

luncheon . . . I talked to Frank White about

it that evening . . .

The next day [at the Convention Center after

offering McIntosh his $125 refund] . . .

1 further told him that he had notified the

Governor in writing that he intended to

disrupt the meeting by speaking, . . . [and] .

• • [W ]e [referring to Finch and the Governor]

had no intention of allowing him to come in

and disrupt the meeting by speaking. We had

the Vice President of the United States there

which we didn't want to make a joke out of the

affair nor have McIntosh create a disturbance,

so we weren't going to allow him to enter and

I told him that. Tr. at 76-77

-2-

It is well settled that speech which is distasteful to

some, or met by unwilling listeners is protected by the First

Amendment. Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15, 22 (1971) (person

wearing jacket insignia "F-K the draft", in opposition to Vietnam

War protected speech), Bachella v. Maryland, 397 U.S. 564, 567

(1970) (remanded case of arrested protestors who lay across

street as action by police may have rested on unconstitutional

grounds to suppress their messages in violation of First

Amendment rights) Further, protection of First Amendment rights

does not turn on an individual's interpretation of its constitu

tional worth. Bachella, supra.; Spence v. Washington, 418 U.S.

405, 413 (1974). Finch's assertion that McIntosh's dress was

"shabby" and not "depicting" a person of modest means, Tr. at 77,

to the degree he acted on behalf of the Governor or to the degree

this lead to McIntosh's detainment was constitutionally imper

missible since his opinion was only a judgment on the content of

the message.

Whether or not a municipality forbids the use of its

facilities for speech purposes, it may not discriminate in its

regulation of expression on the basis of its content. Hudgens v.

NLRB, 424 U.S. 507, 520 (1976). Content based decisions

restricting speech activities by state officials or private per

sons acting through state power is impermissible. Here, the

extent to which the policy officers' actions were based on the

message McIntosh sought to convey is clear from the context in

which they occurred. Finch testified that he had no intention of

allowing McIntosh to attend and "make a joke out of the affair".

His insistence on returning the ticket cost was clearly designed

-3-

to quash the content of McIntosh's message.

In the context of taxation, the Supreme Court has often

made it clear that it is improper for the State to use its power

to suppress speech without meeting the requirements of the First

and Fourteenth Amendments. Murdock v. Penn., 319 U.S. 105, 108

(1943), Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513, 518 (1958). The legi

timate exercise of speech rights are not to be penalized or

encumbered without the state coming forward with 'sufficient'

proof to justify its intrusion. Free expression is a fundamental

personal right. Roth v. U.S. , 354 U.S. 476, 487 (1957). It is

to be protected from those forces which might seek to suppress

because they find the speech activity 'unpopular', 'annoying' or

distasteful. IcL 319 U.S. 116, 87 L.Ed. at 1300 , 357 U.S. at

526, 536, L.Ed.2d at 1473, 1479.

Judicial Review of First Amendment Claims

To determine if McIntosh's First Amendment rights have

been abridged a court should "weigh the circumstances". Here,

McIntosh was a member of the Republican party. McIntosh here

took every precaution to advise the security persons (F.B.I.,

Secret Service) of his intent not to cause any trouble or disrup

tion. Additionally, this luncheon was in part financed and spon

sored by the Republican party and McIntosh was detained from

attending. In an atmosphere of opulence, McIntosh wore simple

clothes in quiet protest. But because of his detainment he was

never heard. The "close analysis" appurtenant to a claim of

abridgment of First Amendment rights was not conducted by the

district court. Speiser, supra, 357 U.S. at 520.

-4-

The manner in which McIntosh's speech was abridged is

likely to have a "chilling" effect on speech activities by the

Petitioner as well as any other person who may find themselves in

disagreement. Id. , at 526 . This Court should carefully review

the findings of the district court because of subsequent

"chilling" effect the district court's decision will have on the

important right involved.

Public and private behavior must be closely scrutinizing

for "a state may not induce, encourage or promote private persons

to accomplish what it is constitutionally forbidden from

accomplishing." Norwood v, Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973) (State

forbidden to lend textbooks to students attending private segre

gated schools). Concomitantly, officials may not effectively

abdicate their professional and public responsibility whatever

the motive. Houser v. Hill. 278 F. Supp. 920 , 928 (M.D. Ala.

1968 ) .

Generally, the First Amendment is applicable to the sta

tes through the Fourteenth Amendment. Chaplinsky v. New

Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568, 571 (1942); West Virginia State Board of

Education v. Barnett, 319 U.S. 624, 639 (1943); Speiser, supra.,

357 U.S. at 530 ; New York Times, supra. , 376 U.S. at 283; Brown

v. Hartlage, 456 U.S. 45, 47 (1982).

First Amendment: Free Expression

McIntosh dressed in "an old suit . . . and cowboy boots

and razorback tie . . . like poor people dress . . . " Tr. at 11,

to symbolize the poor people in the state. Such criticism of

government and official action is both clearly protected by the

-5-

First Amendment and it is a citizen's duty to utilize it. NAACP

v. Clairborne, 458 U.S. 886, 993 (1982):

Discussion of public issues and debate on

qualifications of candidates are integral to

the operation of the system of government

established by our Constitution. The First

Amendment affords the broadest protection to

such political expression in order to assure

[the] unfettered interchange of ideas for the

bringing about of political and social changes

desired by the people.

Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1 (1976), Roth v. U.S., 354 U.S. 476,

484 (1957). The First Amendment guarantees political exchange of

the broadest kind. McIntosh's attendance at the luncheon would

have been extremely consistent with the First Amendment's pur

poses. First his dress illuminated the conditions of the poor.

Through his clothing he peacefully advocated social change to

address these conditions. Discussion of poverty is a public

issue within the comtemplation of First Amendment protection.

McIntosh ran a breakfast program for young children and his per

sonal knowledge would benefit other party members. Moreover,

McIntosh attempted to invoke his First Amendment rights for the

benefit of the encumbent Vice President and the Republican

party's candidate for governor. Not only did McIntosh have the

requisite reasons for utilizing his speech rights he also had an

appropriate audience. In Buckley v. Valeo, supra. , the Court

considered the important role money has on effective political

contribution and expression. Similarly, McIntosh's participation

in political activities, using the luncheon to communicate the

issues of the poor is a fair and realistic view of an effective

relationship between a party and its members. A "free exchange

of ideas provides special vitality to the process of Amercian

-6-

constitutional democracy." Brown v. Hartlage, 456 U.S. 45

(1982). Maintenance of opportunities for free political

discussion allows government to be responsive to the will of its

people. Free expression allows change to be obtained by lawful

means. It's this opportunity which is essential to the stability

of our Republican form of government. McIntosh chose to

peaceably and unobstrusively exercise his First Amendment right.

St.rPmkerg v. California, 283 U.S. 359 , 369 (1930 ). Because free

expression allows government to be responsive while still main

taining stability, it is a coveted right of citizens to be pro

tected by states and by courts.

Our Republican form of government is based on the

sovereignty of its citizens— the ultimate governors of the State.

New York Times, supra, As a result, the constitutional right of

expression is profoundly committed to national debate. That

debate should be "uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and . . .

it may well include vehement, caustic and sometimes unpleasantly

sharp attacks on government and public officials". id. at 270 .

The First Amendment as repeatedly announced by the Supreme Court

does not turn on the popularity of an idea. Id. at 271. That

any person present at the luncheon might be offended by the ideas

McIntosh sought to convey is the essence of "robust" exposure to

new ideas. The interest of the public in an effective free

speech right outweighs the inconvenience of an individual. Id.

Unorthodoxy is tolerated by the First Amendment.

McIntosh was not required tc express himself in ways more fami

liar to potentially hostile listeners. Speiser, supra., 357 U.S.

a,_ 532 . Historically unpopular and unorthodox expression piaved

-7-

a vital and beneficial role in the history of this Nation. Id.

at 532.

A function of free speech under our system of

government is to invite dispute. It may

indeed best serve its high purpose when it

induces a condition of unrest, creates dissa

tisfaction with conditions as they are, or

even stirs people to anger. Speech is often

provocative and challenging. It may strike at

prejudices and preconceptions and have pro

found unsettling effects as it presses for

acceptance of an idea.

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1, 4 (1949). In Terminiello,

the Court upheld the speaker's rights to expression because the

disorderly conduct statute as applied to the petitioner's conduct

violated his right of free speech. Here, McIntosh was not being

abusive, nor was he asserting a right to use "fighting words"

unprotected by the First Amendment. Cohen v. California, 403

U.S. 15, 20 (1971). Nothing in McIntosh's dress was likely to

provoke the ordinary citizen to violence. Id.

The First Amendment doctrine is particularly protective

of political speech. Our speech rights allow for informed

choices to be made, choices between ideas, policies and can

didates. The right to receive information is linked to making

informed choices. The alternative to real choice is repression.

New York Times, supra. Certainly the Republican party's platform

cannot be formed without significant input from each segment of

the party. Participation in party activities is the most effec

tive way to influence potential and encumbent candidates for

public office.

Statutes

It is apparent that McIntosh was the only person stopped

-8-

and questioned before entering the luncheon. The decision to

charge him under the disorderly conduct statute typifies the

misuse of criminal statutes to unconstitutionally restrain pro

tected speech.

In Terminiello v. Chicago. 337 U.S. 1 (1949), the court

held that the application of a broad disorderly conduct statute

was an unconsitution invasion of the First Amendment as applied

to speech activities. Id. at 6. Similarly, in Edwards v. South

Carolina, 372 U.S. 229 (1963), a conviction based upon a disor

derly conduct statute was overturned because " . . . a state (may

not) make criminal the peaceful expression of unpopular views."

See also Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536 (1965).

Here, the district court failed to respond to McIntosh's

First Amendment claim. It is necessary to consider factors other

than race when inquiring into the motivation leading to

McIntosh's arrest. The record indicates that McIntosh was not

disorderly preceding his arrest. He was detained because of his

views and his manner of expressing those views. His detainment

was unconstitutional and a violation of his First Amendment

rights.

Strong policy reasons demand that broadly written statu

tes be examined as applied where the exercise of important

constitutional freedoms are called into jeopardy. The ".

freedom of speech . . . guaranteed by the Constitution embraces

at least the liberty to discuss publicly and truthfully all mat

ters of public concern without previous restraint or fear of

subsequent punishment." Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88, 101,

102 (1940) (emphasis added) Legitimate government purposes can

-9-

not be pursued by regulations that unnecessarily invade an area

of protected freedom. Nor can government pursue its purposes by

means which stifle fundamental liberties. NAACP v. Alabama, 377

U.S. 288, 307 (1964). Enforcing this law penalizes McIntosh for

his attempted assertion of his right and not for criminal

disorder. Merely fearing disorder is an insufficient reason to

abridge First Amendment rights. Cohen v. California, supra., 403

at 23 (1973), Tinker v. Des Moines School District, 393 U.S. 503,

508 (1969).

Statute: Political Practices Act

The Arkansas statute leading to the revocation of

McIntosh's ticket reads, in pertinent part:

3-1113. Records of contributions and

expenditures.

A candidate, a political party, or person

acting in and candidate's behalf shall keep

records of all contributions and expenditures

in a manner sufficient to evidence compliance

with Sections 3 and 4 [§§ 3-1111, 3-1112] of

this Act. Such records shall be made

available to the Prosecuting Attorney in the

district in which the candidate resides who is

hereby delegated with the responsibility of

enforcing this Act.

3-1116. Cash contributions and expenditures

restricted— Writings required.

No campaign contribution in excess of One

Hundred Dollars ($100.00) or expenditure in

excess of Fifty Dollars ($50.00) shall be made

or received in cash. All contributions or

expenditures in behalf of a campaign activity,

other than in-kind contributions and expen

ditures, in excess of the aforementioned

amounts, shall be made by a written instrument

containing the name of the donor and the name

of the payee.

First, the statute requires the candidate's officials to

-10-

keep records of all contributions. Further, the statute requires

that donations of $100 or more be made by written instrument.

While it appears that this statute was technically violated, it

is clear that the statute was not the basis for Finch's concern

nor the avowed reason for preventing McIntosh's attendance. The

police testified that after discussing the probable attendance of

Mr. McIntosh at the luncheon, they decided to use the disorderly

conduct statute as their excuse to arrest him if he tried to

attend the luncheon. No mention was made of arresting McIntosh

for an illegal campaign contribution. Tr. at 94. In reality,

McIntosh was not arrested for illegally paying in cash, or for

disorderly conduct. Instead the statutes were used as convenient

tools to restrain Mr. McIntosh. These actions strike at the

heart of Mr. McIntosh's First Amendment claim. The ".

danger of unrestrained discretion . . . [ is ] . . . such that the

will of the transient majority can prove devestating to freedom

of expression." James v. Board of Education of Central Dist. No.

1̂, 461 F.2d 566, 575 (2nd Cir. 1972). The testimony of the

police officer arresting Mr. McIntosh indicates that any attempt

by McIntosh to enter the luncheon was going to be resisted, Tr.

at 107. If a reason had to be given, disorderly conduct would be

claimed. Nowhere was it mentioned that the Political Practices

Act was a justification for resisting McIntosh's attendance.

Symbolic Speech

The protection of First Amendment rights of expression

extends beyond the spoken word. The First Amendment aims at pro

tecting effective communication of ideas. Tinker v. Des Moines,

-11-

393 U.S. 503 (1969 ), Spence v. Washington, 418 (J.S. 405 (1974),

Brown v. Louisiana, 383 U.S. 131 (1966), New York Times, supra.

Robert McIntosh was dressed in a manner to convey the

plight of poor people. In a luncheon evidenced by its opulance

he wished to recognize the poor by bringing their condition to

the attention of Vice President Bush. McIntosh's visual symbol

is as protected as the spoken word. Spence v. Washington,

supra., 418 U.S. at 410. His mode of expression falls within the

purview of conduct which has been held protected by the Supreme

Court. Spence v, Washington, supra. (statute proscribing

attaching symbols to U.S. Flag a crime, infringed protected

expression as applied to displayer of flag), Cohen v. California,

supra. ('F-K the Draft' slogan on jacket, protected). Tinker v.

Des Moines Indep. School Dist, supra. (Student's right to wear

black armband in opposition to war upheld.)

In addition to conduct the Supreme Court has recognized

association as a legitimate form of expression. Buckley v.

Valeo, 424 U.S. 1 (1976) (campaign contribution form of political

expression). NAACP v. Alabama. (registration of NAACP members

violation of right of expression). In the interest of a free

exchange of ideas the Supreme Court has consistently upheld

abstract forms of expression and discussion. NAACP v.

Clairborne, 458 U.S. at 910; NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 429

(1963). The communicative element of the speaker's action is

protected speech. The acts do not have to meet any subjective

perceptions or decorum or acceptability NAACP v. Clairborne, 458

U.S. at 911. And of course, a person may not be punished for

expressing his or her view in words or through abstraction.

-12-

McIntosh's dress falls easily into the area of protected speech.

-13-

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FINDING THAT THE STATE

POLICE OFFICERS ACTED REASONABLY AND IN GOOD FAITH

AND THAT THEY HAD PROBABLE CAUSE TO ARREST McINTOSH

FOR DISORDERLY CONDUCT

The district court erred in finding that the police

officers acted reasonably, in good faith and that they had pro

bable cause to arrest McIntosh for disorderly conduct. The defi

nition of the crime of disorderly conduct appears in Ark. Stat.

Ann. 41-2901 (1977), where it is stated:

(1) A person commits the offense of disor

derly conduct, if, with the purpose to cause

public inconvenience, annoyance or alarm, or

recklessly creating a risk thereof, he:

. . . (d) Disrupts or disturbs any lawful

assembly or meeting of persons; or

. . . (f) congregates with two (2) other per

sons in a public place and refuses to comply

with the lawful order to to disburse of a law

enforcement officer or other persons engaged

in enforcing or executing the law . . .

Probable cause in this context means:

Such a state of facts known to the prosecutor,

. . . as would induce a man of ordinary

caution and prudence to believe, and did

induce the prosecutor to believe, that the

accused was guilty of the crime alleged, and

thereby cause the prosecution.

Within these definitions, the officers had no probable

cause to believe that McIntosh had engaged in or was guilty of

the crime that cause his arrest. McIntosh was arrested by the

State police officers, Reinold and Phillips, as he was standing

m the public lobby requesting that he be allowed to attend the

appreciation dinner since he had purchased his ticket to do so.

Be was arrested despite the fact that he was neither loud nor

-disruptive at any time during his conversation with Finch,

Reinold, and Phillips. Tr. at 52. Officer Phillips testified at

trial that appellant was arrested solely for requesting that he

be allowed in the luncheon and refusing to leave the lobby area,

an area open to the public. Tr. at 147. Ms. Alyson Lagrossa, a

reporter for the Arkansas Democrat, who was assigned to cover the

luncheon, testified that she was present when McIntosh arrived at

the luncheon and was refused admittance by Finch, Reinold and

Phillips. Her testimony confirmed that at no time was McIntosh

loud or disruptive prior to his arrest and that he did not use

abusive or profane language in addressing Finch and the officers

when requesting that he be allowed in. Tr. at 52.

An arrest is not constitutionally valid unless probable

cause exists to make it valid. The constitutionality of

warrantless arrests depends on whether at the moment of the

arrest, the facts and circumstances within the arresting

officer's knowledge are sufficient to warrant a prudent man to

believe that the arrestee had committed or was committing a cri

minal offense. D.S. v. Strickland, 490 F.2d 378 (9th Cir. 1974);

Dunaway v. State of New York, 442 U.S. 200 (1979). A deter

mination of probable cause for arrest does not rest upon a tech

nical framework, but rather a consideration of the entire body of

facts and circumstances existing at the time of the arrest. U.S.

v. Ganter, 436 F.2d 364 , 369 (7th Cir. 1970). In Ark, Stat.

43-403 (1977), which provides the grounds for a warrantless

arrest, the police officer must have reasonable grounds for

believing that the person arrested has committed a felony, and

these "reasonable grounds" are the equivalent of probable cause.

U.S. v. Barber, 557 F.2d 628 (8th Cir. 1977).

In the case at bar, the officers had no probable cause

to believe that McIntosh had engaged in a crime to justify his

arrest. His behavior was not threatening or loud. He had

notified authorities of his intention to make symbolic protest,

i.e. dressing in rags to represent the poor people. No one

stated a dress code and no reference was made to one on the

ticket. Tr. at 142. The particular mode of dress simply was not

an issue. When approached by the officers, he did not create a

scene or act in any way to warrant suspicion by the officers that

he had committed or would commit any disruptive act. The offi

cers merely arrested McIntosh without questioning his motives or

waiting for sufficient probable cause to arrest him. In view of

the entire factual record, i.e. McIntosh's writing a letter

stating his form of peaceful protest, his purchase of a $125

ticket; his assurance to the Secret Service that he was not going

to do anything to disrupt the proceeding and that his manner of

dress would be his only symbol of protest, Tr. at 36; and his

lack of disorderly conduct, the circumstances do not support pro

bable cause sufficient to arrest.

While courts assume that officers act in good faith in

arresting, this presumption is not sufficient to establish the

validity of an arrest without a warrant. If this subjective test

were sufficient alone, the protections of the Fourth Amendment

would be diminished and individual protection would be left to

the discretion of the police. Beck v. Ohio, 379 LJ.S. 89, 99

(1964 ). Consequently, more than a good faith arrest must be

found on the part of the officers. Good faith must be grounded

in reasonableness and supported by probable cause. Perkins v.

-16-

Cross, 562 F. Supp. 85, 87 (E.D. Ark. 1983 ). In light of the

facts, circumstances, and relevant testimony, there was not suf

ficient probable cause to arrest McIntosh, and the officers acted

unreasonably in the arrest.

In the instant case, the district court clearly erred in

finding that McIntosh's past behavior and letter to Governor

White gave the officers probable cause to believe that he would

disrupt the luncheon, and therefore had a right to arrest him.

The evidence demonstrates that McIntosh's behavior gave the offi

cers no probable cause to arrest. As Officer Phillips testified

at trial "he was not loud or disruptive at any time prior to his

arrest." Tr. 147. It appears that the Court is saying that

McIntosh's past "criminal status" justifies the arrest. However,

this form of preventive detention is unlawful and unconstitu

tional .

In cases of false imprisonment, lack of malice, presence

of good faith, or presence of probable cause does not affect the

existence of the wrong if the detention is unlawful. Nesmith v.

Alford, 318 F .2d 110, 119 (5th Cir. 1963) reh. denied, 319 F.2d

859 (5th Cir. 1963), cert, denied, 375 U.S. 945 . The only cri

teria necessary to establish false imprisonment is that an indi

vidual have his liberty restrained under the "probable imminence

of force without any legal cause or justification." Id. at 128.

The actions of the police officers in arresting McIntosh and

detaining him for over two hours consititutes false arrest and

malicious prosecution because the officers failed to act with

probable cause and in good faith. Furthermore, there is no doubt

as to the total lack of legal justification for the arrest.

-17-

There was no disorderly conduct or disturbance at any point prior

to the arrest to justify arresting McIntosh for his peaceful,

legal and constitutionally protected actions. Nesmith v. Alford,

318 F .2d at 120.

The testimony shows that McIntosh was arrested and taken

all the way to North Little Rock. He was detained there for

nearly two hours before being charged with a crime until the

fundraising affair, to which he had a ticket, was over. The

testimony of Judy Kaye Mason, who was the North Little Rock

Prosecuting Attorney at the time, indicated that she observed

McIntosh being held in jail without being charged, and she told

Officers Reinold and Phillips that they had to book McIntosh or

let him go. She also testified that this was the first time she

had ever heard of a situation where the arresting officers

arrested a person in Little Rock and took him all the way to

North Little Rock to be detained. Tr. at 58, 59, 61. All of the

above actions prevented McIntosh from attending the fundraising

dinner and leads to the conclusion that the officers acted

unreasonably, in bad faith, and without probable cause to arrest

the appellant. These actions were malicious, willful and without

legal justification, thus depriving McIntosh of his constitu

tional rights. The District Court clearly erred in finding

otherwise. Perkins v. Cross, 562 F. Supp. 85 , 87 (E.D. Ark.

1983 ) .

-18-

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, the decision of the District

Court finding that none of the appellees deprived the appellant

of any of his constitutional or federally protected rights, nor

did they any violate any law, should be reversed. The Court is

asked to reverse this erroneous ruling and remand this case to

the District Court with instructions to enter judgment in favor

of the appellant, and to award costs and reasonable attorney's

fees.

Respectfully submitted,

HELLER, WALKER & TORRENCE

415 Main Place Building

415 Main Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

(501) 374-3420

JACK GREENBERG

RONALD L. ELLIS

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

By:

/ 'Horace A. Walker

-19-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, Horace A. Walker, hereby certify that I have on this

2nd day of July, 1984 , served by mailed a copy of the foregoing

to Ms. Mary Stallcup, Asst. Attorney General, Justice Building,

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201, Mr. James M. McHaney, 1021 First

Commercial Building, Little Rock, Arkansas 72201, and Mr. Terry

Ballard, 2115 Main Street, North Little Rock, Arkansas 72114.

-20-

1244 5 8 2 F E D E R A L S U P P L E M E N T

See S ru ly k v. Heckler, 575 F.Supp. 1266,

1268 (N.D.111.1984) (“... to Bimply declare

that plaintiffs complaints of pain were ‘not

entirely credible,’ without further explana

tion, constitutes error on the part of the

AU.”) Finally, plaintiff testified that he

has problems with his grip and has offered

to this court medical evidence which sup

ports the existence of tunnel carpal syn

drome. Considered as a whole, the record

indicates that plaintiff s physical limitations

sufficiently compromise his ability to do

basic work activities. The requisite level

of impairment severity has been met.

Conclusion

The cross motions for summary judg

ment are denied. This case is remanded £o

the Secretary for further proceedings con

sistent with this opinion. The Secretary is

to take the next steps in the sequential

evaluation mandated by the regulations.

(O f «[VMUMBf«SYSTlM>

Robert “Say” McINTOSH, Plaintiff,

v.

Frank WHITE, Individually and as Gov

ernor of the State of Arkansas, Arkan

sas Republican Party— Frank White

Election Committee, Curtis Finch, Jr.,

Individually and as Campaign Chair

man of the Frank White Re-Election

Committee, Arkansas State Police;

Tommy Goodwin, Individually and as

Director of the Arkansas State Police,

North Little Rock City Police Depart

ment, Bill Younts. Individually and as

■ Chief of North Little Rock Police De

partment, John Doe. and Richard Roe,

etc., Defendants.

No. LR-C—82-153.

United States District Court,

E.D. Arkansas.. W.D

March 19, 1984.

Black plaintiff who was excluded from

political luncheon brought civil rights ac

tion which included state law claim for

false arrest or malicious prosecution. The

District Court, -Henry Woods, J., held that

(1) with regard to plaintiffs exclusion from

political luncheon held at city convention

center, there was no significant involve

ment of state sufficient to meet section

1983 requirefnent of state action; (2) in

determining that plaintiff should be exclud

ed from luncheon which was a purely pri

vate event, chairman of campaign commit

tee acted reasonably and in good faith and

solely as a private person, and thus actions

of chairman did not violate plaintiffs con

stitutional rights; (3) evidence was insuffi

cient to support allegation that exclusion

constituted purposeful discrimination on

basis of plaintiffs race; and (4) plaintiff

faded to state claim for false arrest or

malicious prosecution, where officers who

arrested plaintiff for disorderly conduct

upon his exclusion from luncheon had prob

able cause and acted in good faith.

Order accordingly.

1. Civil Rights ®=13.5(2, 4)

A plaintiffs claim under section 1983

must be based upon proof that actions of

defendant deprived him of a right secured

by Cocstitution or laws of the United

States, while defendant was acting under

color of state law; statute does not reach

purely private conduct. 42 -U.S.C-A.

§ 1983

2. Civil Rights «=13.5(2)

In order to establish state action, plain

tiff mast establish a close nexus between

challenged conduct and the state, so that

the state can be said to have a significant

involvement in the activity.

3. Civil Rights ®=13.5(4)

There was no ’significant involvement

of state sufficient to meet section 1983

requirement of state action with regard to

incident in which black plaintiff was barred

entry to political luncheon held at conven-

M cIntosh v . white 1245

C ltt u K 2 F « u p p . 1244 (1964)

tion -center owned by dty, where city al

lowed persons to rent center for private

functions and to exclude members of public

as they wished, and reelection campaign

committee and political party which organ

ized the luncheon were private organiza

tions. 42 U.S.C.A. § 1983.

4. Constitutional Law ©=90.1(4)

Fact that a private function is held at a

public facility does not render the activity

or the function itself a public forum for aU

speakers, trespassers, or uninvited guests,

regardless of the facility’s other potential

uses as a public forum.

5. Civil Rights £=>13.5(4)

Although a political party’s function in

holding election primaries or other clearly

public functions may meet a liberal “state

action” requirement, in its function of fund

raising and campaigning, party is clearly

private.

6. Civil Rights <8=13.5(2)

In determining whether state action

exists, court must look to specific activity

which is subject of the lawsuit and not to

unrelated activities.

7. Civil Rights ©=13.4(1), 13.5(4)

Actions of chairman of campaign com

mittee in refusing to accept proffered cam

paign donationv thereby excluding black

plaintiff from political luncheon, did not

violate plaintiffs constitutional rights so

as to establish a section 1983 cause of

action, since chairman acted reasonably

and in good faith and solely as a private

person. 42 U.S.C.A. § 1983.

8. Conspiracy «=7.6

Actions of chairman of campaign com

mittee and others in excluding black plain

tiff from political luncheon did not consti

tute invidious class-based discrimination,

as required by section 1983, in view of fact

that others of black race were allowed ad

mission to the luncheon. 42 U.S.C.A

§ 1983.

9. Civil Rights ©=13.4(6)

In order to succeed in a section 1981

action based on racial discrimination, plain

tiff must show purposeful discrimination.

42 U.S.C.A. § 1981.

10. Civil Rights ©=13.13(3)

Evidence in section 1981 action alleg

ing that defendants’ exclusion of black

plaintiff from political luncheon constituted

discrimination was insufficient to support

plaintiffs allegation that conduct of de

fendants in excluding him was purposeful

and based upon his race. 42 U.S.C.A.

§ 1981.

11. Conspiracy ©=19

Evidence in civil rights action brought

by black plaintiff who was excluded from

political luncheon faded to' establish that

exclusion was based upon some racial, or

otherwise class-based invidiously discrimi

natory animus, as required by section 1985.

42 U.S.C.A. § 1985.

12. Conspiracy «=13

If plaintiff is not able to state or prove

a claim under section 1985, a derivative

Claim under section 1986-tnust fail as well.

42 U.S.C.A. §§ 1985, 1986.

13. False Imprisonment ®=10, 13

Malicious Prosecution «=18(2)

In order to establish a cause of action

for false arrest or malicious prosecution

under pendent tort claims raised in civil

rights action brought by black plaintiff

who was arrested for disorderly conduct

following his exclusion from political lunch

eon, plaintiff was required to show that

police officers who effected arrest were not

acting in good faith and upon probable

cause.

14. False Imprisonment «=13

Malicious Prosecution «=24(2)

- Fact that plaintiff who brought action

against police officers for arrest and mali

cious prosecution was officially acquitted

of charge of disorderly conduct was not in

and of itself sufficient to establish that the

officers acted without probable cause.

15. False Imprisonment ®=13

Malicious Prosecution ©=18(1 >

Under Arkansas lav.. probable cause in

context of a false arrest or malicious prose-

1246 582 federal supplement

cution case means such a state of facts

known to the prosecutor as would induce a

man of ordinary caution and prudence to

believe, and did induce the prosecutor to

believe, that accused was guilty of the

crime alleged, and thereby caused the pros

ecution.

16. False Imprisonment «=20(1)

Where plaintiff failed to show that po

lice officers who arrested him for disorder

ly conduct acted without probable cause or

in bad faith, plaintiff failed to state a claim

for false arrest.

Horace A. Walker, Little Rock, Ark., for

plaintiff.

Mary Stallcup, Asst. Atty. Gen., State of

Ark., Little Rock, Ark., for defendants.

James M. McHaney, Little Rock, Ark.,

for Curtis Finch, Jr.

Walter Paulson, Jr, Little Rock, Ark.,

for Frank White.̂

Jim Hamilton, City Atty., No. Little

Rock, Ark., for North Little Rock Police.

FINDINGS OF FACT AND

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

HENRY WOODS, District Judge.

FINDINGS OF FACT

1. The plaintiff, Robert “Say” McIntosh

is a United States citizen and a resident of

Little Rock, Pulaski County, Arkansas. He

î a member of the black race.

2. ' Defendant Frank White was during

the time frame relevant to this lawsuit

Governor of the State of Arkansas and

titular head of the Arkansas Republican

Party. In February, 1982 he was a candi

date for reelection.

3. Defendant Curtis Finch, Jr. was at

all times material to this action chairman of

the Frank White Re-Election Campaign

Committee. He was charged with the ex

ecutive control of the Frank White Re-Elec

tion Campaign Committee and thereby ex

ercised the executive authority over its

fund-raising activities He is a citizen of

Arkansas and holds no public office in the

State of Arkansas.

4. Defendants Jerry Reinold and Bar

ney Phillips are police officers of the Ar

kansas State Police and as such are

charged with the responsibility for enforce

ment of the criminal laws of the State of

Arkansas.

5. A Governor Frank White Apprecia

tion Luncheon was scheduled to be held at

the Little Rock Convention Center at noon

on February 26; 1982. The Little Rock

Convention Center is owned and operated

by the City of Little Rock.

6. The Center is comprised of several

.exhibit halls and other areas which are

available for rent for the conduct of public

or private functions, and it is a regularly

accepted practice to charge admission

prices for the functions held therein and to

exclude persons who have not paid an ad

mission price.

7. The City of Little Rock does not in

volve itself in private .functions nor does it

require organizations holding private func

tions in the Center to hold them open to the

public.

8. The Governor Frank White Apprecia

tion Luncheon was designed as a fund rais

er and was organized and financed by the

Frank White Re-Election Campaign Com

mittee and the Republican Party. The

luncheon was open to those supporters of

Mr. White who were willing to make a

$125.00 campaign contribution in return for

a ticket to the luncheon.

9. Vice President George Bush ap

peared as the featured speaker at the

luncheon.

10. The luncheon was in all respects a

private function, and admission was limited

to ticket holders only.

11. On February 25, 1982 Reverend

Daniel Bowman, accompanied by Mr. Rob

ert “Say” McIntosh, purchased a ticket

from the Campaign Committee, paying for

the ticket in cash. It is not clear on whose

behalf the ticket was purchased, but Mr.

McIntosh and Rev. Bowman stated that

1247M cIntosh ▼. white

C tu u 5*2 F S u p jk 1144 (19M )

they both contributed toward the purchase

price.

12. On that same day Mr. McIntosh

sent a letter to then Governor Frank White

in which he stated that Mr. McIntosh in

tended to speak at the luncheon and re

quested that Governor White inform him

whether he should speak before or after

the Vice President

13. A previous series of written and

published statements indicated that Mr.

McIntosh was both personally and political

ly opposed to Mr. White and to his candida

cy for governor.

14. Finch was concerned over the pur

chase of a ticket with an amount tendered

in cash, which could not be accepted in

their belief because the amount exceeded

that authorized by law for cash contribu

tions under the Political Practices Act, Ark.

StatiAnn. § 3-1116. In view of plaintiffs

past history, Finch was also concerned that

plaintiff would disrupt a meeting at which

the Vice President was the featured speak

er.

15. The Secret Service had similar con

cerns and called in Mr. McIntosh and se

cured an agreement that he would not ap

proach the head table where the Vice Presi

dent would be seated and would not inter

rupt the latter’s speech. McIntosh left the

definite impression with the Secret Service

agent that he planned to speak at the meet

ing but would speak from his seat.

16. At approximately 11:00 a.m. Mr.

McIntosh tame to the Convention Center

and sought admission to the luncheon. Mr.

Curtis Finch, accompanied by Sergeants

Remold and Phillips, members of the State

Police and of the Governor’s security’ force,

met Mr. McIntosh at "the door. Mr. Finch

informed Mr McIntosh that his ticket had

been purchased in cash, in violation of the

Political Practices Act, and that he would

not be admitted to the function. Mr. Finch

repeatedly tendered a refund and explained

to Mr. McIntosh that he w'ould not be al

lowed to enter the luncheon and asked him

to leave the premises.

17. Mr. McIntosh on each occasion

when asked to accept a refund refused and

stated that he intended to enter the lunch

eon. Sergeant Remold then identified’him

self and Sergeant Phillips and told Mr.

McIntosh that the luncheon was a private

function, that Mr. Finch would not accept

his ticket, ■ and that Mr. McIntosh yvas

therefore requested to leave and would be

required to do so.

18. When Mr. McIntosh refused to

Teave, Sergeant Remold informed him that

he' would be arrested for creating a distur

bance if he failed to leave the premises.

Mr. McIntosh replied, “Well, take me to

jail.”

19. Mr. McIntosh was thereupon arrest

ed at 11:27 A.M., according to the State

Police Radio Log, and escorted out of the

building by Sergeants Reinold and Phillips.

As he was leaving via the escalator, he

yelled to the entering ticket holders, "You

peckerwoods, I shall return.”

20. The officers took Mr. McIntosh to

the North Little Rock jail because the Lit

tle Rock jail policy prohibited acceptance of

prisoners from outside law enforcement of

ficers. He arrived there at 11:36, accord

ing to the State Police Radio Log.

21. At the North Little Rock jail, Mr.'

McIntosh' was charged with disorderly con

duct, questioned, booked and released on

his own recognizance at 1:16 P.M., accord

ing to the records of the North Little Rock

Police Department. There was no inordi

nate delay in booking and releasing plain

tiff. The short delay was caused by two

other individuals being booked ahead of

him and the unfamiliarity of the State Po

lice officers with the paper work required

by the North Little Rock Police Depart

ment.

22. There is no credible evidence that

any pf the actions by any of the defendants

taken against Mr. McIntosh were based

upon his race. There were 25-40 blacks in

attendance at the luncheon.

23 The actions taken by Mr. Curtis

Finch were in his capacity as a private

' * t x* *s, 4;'**

1248 5 8 2 F E D E R A L S U P P L E M E N T

citizen, serving as Chairman of the Frank

White Re-Election Campaign Committee.

24. The actionB taken by Sergeants Rei-

nold and Phillips, -while they were acting in

their capacities as officers of the Arkansas

State Police, were taken reasonably and in

a good faith effort to perform their duties

as law enforcement officers.

25. Sergeants Reinold and Phillips ar

rested Mr. McIntosh because they believed

in good faith that he had committed the

misdemeanor of disorderly conduct in their

presence, both by refusing to leave the

premises and by refusing to comply with a

lawful order of a law enforcement officer.

26. There is no evidence that any action

taken by Sergeants Reinold or Phillips

were based upon Mr. McIntosh’s race.

27. The Court finds no evidence, either

direct or circumstantial, indicating that

these police officers conspired with any

other person to prevent Mr. McIntosh from

attending the luncheon, nor were they told

in advance to arrest Mr. McIntosh. From

the evidence, it appears that they were

warned that Mr. McIntosh would present

himself and demand entry for the purpose

of disrupting the luncheon, but that they

were Dot to arrest him unless he violated

the law.

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

1. At the close of plaintiffs evidence,

the Court dismissed the complaint as to

Governor White, State Police Superintend

ent Tommy Goodwin, and North Little

Rock Chief of Police Robert Younts. The

plaintiffs proof faded to connect those indi

viduals with this episode in .any manner.

Governor White did receive communica

tkms from the plaintiff, but there is no

testimony that he ordered plaintiff s arrest

or was present when he was arrested. The

Court has jurisdiction of the various causes

of action under the statutes alleged, includ

ing the First, Fourth, Fifth, Thirteenth and

Fourteenth Amendments to the United

States Constitution. 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981,

1983, 1985, 1986 &Dd 1988. The Court has

jurisdiction over the common-law claims un

der its pendent jurisdiction because the two

claims derive from a common nucleus of

operative facts and the plaintiff would ordi

narily be expected to try his claims in one

proceeding. U nited M ine W orkers v.

Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715, 86 S.Ct 1130, 16

L.Ed.2d 218 (1966).

[ 1 ] 2. The plaintiffs claims under 42

U.S.C. § 1983 must be based upon proof

that the actions of the defendants deprived

him of a right secured by the Constitution

or laws of the United States, while that

defendant wTas acting under color of state

law. D ai'is v. Paul, 505 F.2d 1180 (6th

Cir.), reversed on other grounds 424 U.S.

693 (1974). The statute does not reach

purely private conduct. See, e.g., B raden

v. Texas A & M U n iversity S ystem s, 636

F.2d 90 (5th Cir.1981).

[2] 3. In order to establish state ac

tion, the plaintiff must establish a close

nexus between the challenged conduct and

the state, so that the state can be said to

have a significant involvement in the activi

ty. R en dell-B aker v. Kohn, 457 U.S. 830,

102 S.Ct. 2764, 73 L.Ed.2d 418 (1982).

[31 4. Based upon the facts as present

ed, the Court finds no significant involve

ment of the state that is sufficient to meet

the requirements to show state action, in

barring entry to the luncheon. Although

the facility is publicly owned, it is owned by

the city' and the city is not a party to this

proceeding. Further, the city allows per

sons to rent it for private functions to

exclude members of the public more or less

as they wish, as for example for failure to

pay an admission price. The Court ex

pressly finds that the city does not require

by contract or otherwise private groups

making use of the facility to grant access

to all members of the public. In fact, to do

so would substantially restrict the useful

ness of such facilities, since many private

groups hold functions for which they

charge admission and for which they must,

as a matter of logic and economic necessi

ty, deny admission tcrxhose who have not

paid the admission price

McLNTOSH v. WHITE J2 4 9

CU« M M2 f S u p p 1244 (1944)

[4] 6. The fact that a private function

is held at such a facility, regardless of the

facility’s other potential uses as a public

forum, does not render the activity or the

function itself a public forum for all speak

ers, trespassers or uninvited guests. H a r

low v. F itzgera ld , 457 U.S. 800, 102 S.Ct.

2727 , 73 LEd.2d 396 (1982); Green v.

White, €93 F.2d 45 (8th Cir.1982).

6. The proof adduced at trial indicated

that the Frank White Re-Election Cam

paign Committee was a private organiza

tion, which existed solely for the purpose

of directing the campaign of Frank White

and raising funds pursuant to that effort.

There was no direct involvement by the

state or by any governmental entity.

[5,6] 7. The Arkansas Republican

Party is also private for the purposes of

this litigation. It may be that in the Re

publican Party’s function in holding elec

tion primaries or other clearly public func

tions, the Republican Party could arguably

be said to meet a liberal “state action”

requirement However, in its function of

fund raising and campaigning, the party is

. clearly private. As the court held in Ren-

dell-B aker, su pra , the court in determining

whether state action exists must look to

the specific activity’ which is the subject of

the lawsuit and not to unrelated activities.

8. The facts establish that Mr. McIn

tosh purchased a ticket to the luncheon in

cash, which was at least a technical viola

tion of the Arkansas Political Practices

Act, Ark.Stat.Ann. § 3-1116. That law

provides that no campaign -contribution in

excess of $100.00 can be made in cash. Mr.

Finch had a right and â egal duty to abide

by that statute and was reasonable in di

recting the refund of the cash contribution

after it was mistakenly accepted.

17] 9. Mr Finch did not consider the

plaintiff a campaign supporter, and as a

private citizen in the exercise of his First

Amendment rights to campaign for high

public office, he was free to accept or re

fuse to accept a proffered campaign dona

tion. Mr. Finch chose to refuse, and the

Court does not find that this refusal

amounted to a violation of the plaintiffs

constitutional rights.

10. Mr. Finch, acting in his capacity as

Chairman of the Campaign Committee, was

also reasonable in attempting to tender a

return of the cash donation to the plaintiff

and it cannot be said that as a private party

he violated the constitutional rights of the

plaintiff in excluding him from Jhe lunch

eon.

11. Mr. Finch had been placed on notice

by Mr. McIntosh that he intended to speak

at the luncheon, and the Court finds that

Mr. McIntosh’s previous activities as they

related to Governor White clearly indicated

that he would have been most uncompli

mentary and disruptive. In determining

that Mr. McIntosh should be excluded from

a purely private event, Mr. Finch therefore

acted reasonably and in good faith and

solely as a private person. Plaintiff has

cited no cases, and the Court-, knows of

none, that support the proposition that Mr.

McIntosh had a constitutional right to en

ter and disrupt the luncheon.

12. In fact, to the Contrary, while free

dom of expression iE a fundamental right,

the courts recognize the necessity of pre

venting flagrant abuses of such rights by-

individuals who would utilize no self-re

straint in exercising such a right. P ocket

Books, Inc. v. Walsh, 204 F.Supp. 297

(D.Conn.1962); L lo y d Corp. v. Tanner, 407

U.S. 551, 567-68, 92 S.Ct 2219, 2228, 33

L.Ed.2d 131 (1972).

13. Based upon the reasoning of the

foregoing cases, it is clear that the only

constitutiona] right owed to Mr. McIntosh

was his right to rent the facility from the

city on an equal basis with the defendants,

and there is no allegation that he was de

nied that access. He was not free to im

pose himself upon the listeners at the Ap

preciation Luncheon who had come to hear'

the Vice President of the United States.

[8] 14. Although the plaintiff com

plains that the actions taken byr these de

fendants were on the basis of his race, the

proof clearly shows that others of the black

race were allowed admission to the Appre

1250 6 8 2 F E D E R A L S U P P L E M E N T

ciation Luncheon. While this fact is not

conclusive on the issue of racial motivation,

it is at least persuasive circumstantial evi

dence that race was not the deciding factor

in the decision to exclude Mr. McIntosh.

The evidence adduced on this point raises a

requirement on the part of Mr McIntosh to

establish by direct or circumstantial evi

dence some basis for asking the Court to

conclude that race was any factor in the

decision of defendants. Absolutely no such

evidence has been adduced by the plaintiff

on that issue. It appears to the Court, and

we so find, that the discrimination against

Mr. McIntosh was purely against him as an

individual and not because of his member

ship in any race or class. The Court finds

no invidious class-based discrimination, as

is required under 42 U.S.C. i 1983, which

provides protection only for deprivations of

constitutional rights and creates no inde

pendent tort liability on its own right

19] 15. Plaintiff also raises the issues

under 42 U.S.G. § 1981. In order to suc

ceed the plaintiff must show purposeful

discrimination on the basis of his race.

W ashington v. D avis, 426 U.S. 229, 96

S.Ct 2040, 48 L.Ed.2d 597 (1976); W il

lia m s v. D eK alb C ou n ty , 582 F.2d 2 (5th

Cir.1978); G rigsby v. N o rth M ississipp i

M edical Center, Inc., 586 F.2d 457 (5th

Cir.1978); Johnson r. H offm an, 424

F.Supp. 490 (E.D.Mo.), a jffd 572 F.2d 1219

(8th Cir.), c e r t d en ied 439 U.S. 986, 99

S.Ct 579, 58 L.Ed.2d 658 (1978).

N6. In N ew ton v. K roger, 83 F.R.D. 449,

454 (E.D.Ark. 1979), Judge Arnold, now of

the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals, held

that a plaintiff in order to succeed under

§ 1981 “must show subjective intent ...”

To do so the plaintiff must do more than

show merely that he was a member of the

black race. The plaintiff must introduce

•evidence showing a deliberate intention on

the part of the defendants or any of them

to discriminate against him on the basis of

his race. Thus, he may show “either by

statistical evidence or by testimony of spe

cific racially motivated incidents, that there

is probable cause to believe that {the refus

al to honor his ticket] ... was motivated in

substantia] part by race.” N ew to n v. K ro

ger, su p ra at 454.

[10] 17. There is no evidence in this

case, direct or indirect, of specific racially

motivated incidents, statistical evidence, or

any other form of evidence which would

support the plaintiffs allegation" that the

conduct of the defendants was purposeful'

and based upon his race. The claims under

§ 1981 must therefore fail.

[11] 18. The plaintiff has also alleged

causes of action under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1985

and 1986. It is clear that § 1985 provides a

civil remedy for both public and private

infringements of constitutionally protected

rights. G riffin v. B reckenridge, 403 U.S.

88, 91 S.Ct 1790, 29 L.Ed.2d 338 (1971).

But § 1985 has clearly been limited to ap

plication in cases where the plaintiff is

deprived of a constitutionally protected

right or privilege, and where the act is

based upon “some racial, or perhaps other

wise class-based invidiously discriminatory

animus.” G riffin v. B reckenridge, su p ra '

at 102, 91 S.Ct at 1798. For the reasons

set forth in the foregoing conclusions of

law, the Court finds that there has been no

showing of any class-based invidiously dis

criminatory animus on behalf of any of the

defendants.

19. Further, the Court expressly finds

that there has been no infringement of any

constitutionally protected right by any of

the defendants. There is therefore no ba

sis for an action under § 1985.

[12] .'20. 42 U.S.C. § 1986 is a mispri

sion statute and is derivative in nature. It

is axiomatic that Lfrthe plaintiff is unable to

state or prove a claim under § 1985, the

derivative claim under § 1986 must fail as

welL W illiam s v. S t Joseph H osp ita l, 629

F.2d 448 (7th Cir.1980); T ollett v. D am an,

497 F.2d 1231 (8th Cir.), c e r t d en ied 419

U.S. 1088, 95 S.Ct 678, 42 L.Ed.2d 680

(1974).

[13] 21. In order to establish a cause

of action for false arrest or malicious pros

ecution under the pendent tort claims

raised in this cause of action, the plaintiff

SHIREY v. UNITED STATES

Q l t u 582 F £ u p p 1251 (1984)

1251

is required to show that the police officers

who effected the arrest were not acting in

good faith and upon probable cause. P e r

k in s v. Cross, 562 F.Supp. 85, 87 (E.D.Ark.

1983). This is true even though the police

officer did not choose the wisest or most

reasonable course of action that he could

have taken under the circumstances.

114] 22. As the Court has found, Mr.

McIntosh was eventually acquitted of the

charge of disorderly conduct. This, how

ever, is not in and of itself sufficient to

establish that any of the defendants acted

“without probable cause.”

23. Of course, with respect ,to the de

fendants other than the state police defend

ants, there has been no showing that they

acted at all. The testimony of the police

defendants was that they acted because

they believed that the misdemeanor of dis

orderly conduct, as set forth in Ark.Stat