Linmark Associates, Inc. v. The Township of Willingboro Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Linmark Associates, Inc. v. The Township of Willingboro Brief Amicus Curiae, 1975. 700d3c4f-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8511818c-af79-48c9-8c0f-13588bdd4010/linmark-associates-inc-v-the-township-of-willingboro-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

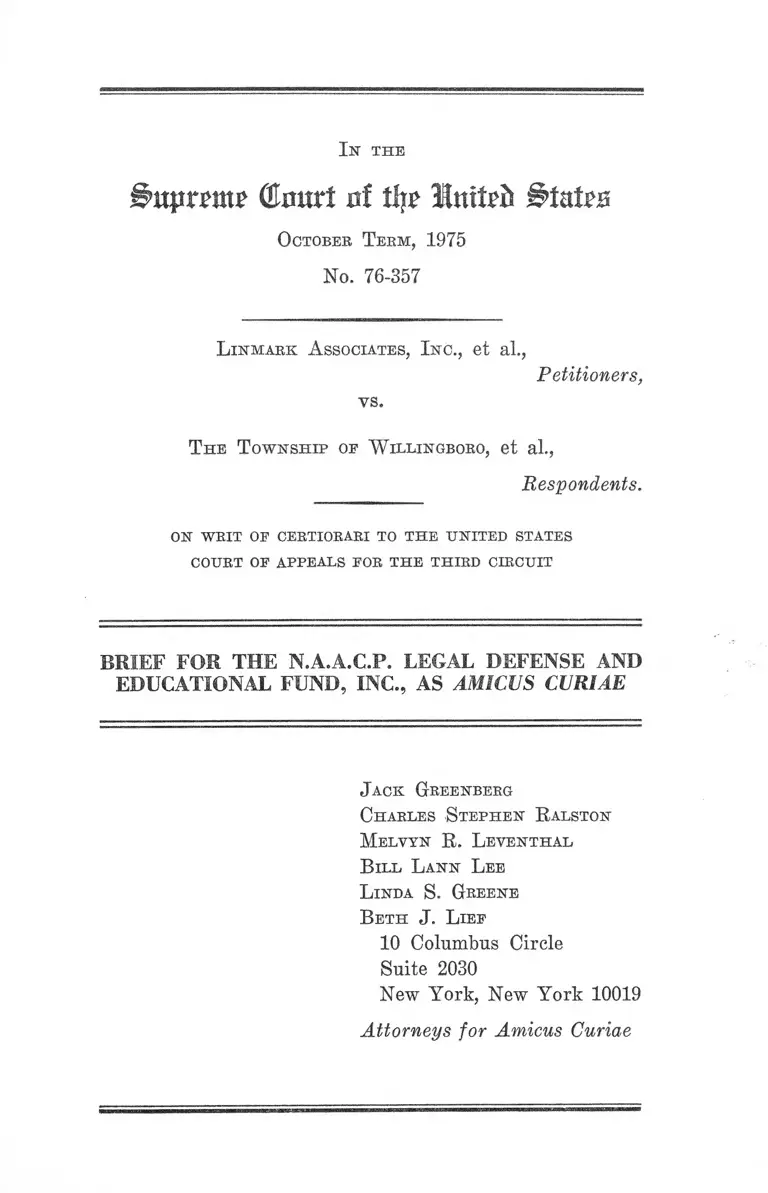

I n t h e

(Eourt of % IttM Btatez

October Term, 1975

No. 76-357

L inmark A ssociates, Inc., et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

T he T ownship of W illingboro, et al.,

Respondents.

o n w r i t o e c e r t i o r a r i t o t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s

COURT OE APPEALS EOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE

J ack Greenberg

Charles Stephen R alston

Melvyn R. L eventhal

B ill L ann L ee

L inda S. Greene

B eth J. L ief

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Interest of Amicus Curiae ............................................... 1

A rgument

Introduction ............................................................................. 2

Summary of Argum ent...................................................... 3

I. The Willingboro Ordinance Enforces the Fair

Housing Guarantee of the Thirteenth Amend

ment and the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment ........................................ 3

A. The National Fair Housing Guarantee .... 3

B. The Willingboro Ordinance .......................... 7

II. The Willingboro Ordinance Is an Appropriate

Means of Thwarting Panic Selling to Pre

serve an Integrated Community And Does

Not Offend the First Amendment ................... 10

A. The Ban on “ For Sale” and “Sold” Signs

Is Closely Belated to Illegal Discrimina

tion in Housing ........................................... 12

B. The Proliferation of “For Sale” and

“ Sold” Signs in a B,acially Tense Com

munity Broadcasts a Threatening and

Deceptive Message ....................................... 14

C. “ For Sale” and “ Sold” Signs Are Thrust

Upon a Captive Audience ............................. 16

Conclusion ...................................................... 18

A p p e n d i x A—

State and Local Anti-Panic Selling Provisions .... la

PAGE

11

T able oe A uthorities

Cases: page

Barrick Realty, Inc. v. City of Gary, Indiana, 354

F. Supp. 126 (N.D. Ind.), aff’d 491 F.2d 161 (7th

Cir. 1974) ..........................................................................5,14

Bigelow y . Commonwealth of Virginia, 421 U.S.

809 .................................................................................. 10,11,12

Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969) .................... 11

Brown v. State Realty Co., 304 P. Supp. 1236 (N.D.

Ga. 1969) .......................................................................... 13

Charles of the Ritz Distribs. Corp. v. PTC, 143 F.2d

676 (2d Cir. 1944) .......................................................... 15

Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1969) ............................. 18

Donaldson v. Read Magazine, Inc., 333 U.S. 178 (1948) 14

E. P. Drew & Co. v. PTC, 235 F.2d 735 (2d Cir. 1956) 14

Erznoznik v. City of Jacksonville, 422 U.S. 205

(1976) ..............................................................................16,18

Head v. Board of Examiners, 374 U.S. 424 (1960) ..... 14

Jacob Siegel Co. v. PTC, 327 U.S. 608 (1946) ........... 14

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968) .... 6

Lehman v. City of Shaker Heights, 418 U.S. 298 (1974) 17

Levitt and Sons, Inc. v. Division Against Discrimina

tion in State Department of Education, 31 N.J.

514, 158 A.2d 177, appeal dism., 363 U.S. 418 (1960) 7

Linmark Associates, Inc. v. Township of Willingboro,

535 F.2d 786 (3rd Cir. 1976) ...................................... 1, 7, 8

Markham Advertising Co. v. State, 73 Wash. 2d 405,

439 P.2d 248, appeal dism., 393 U.S. 316 (1969) ..... 17

NLRB v. Gissel Packing Co., 395 U.S. 575 (1969) ....... 15

I l l

National Commission on Egg Nutrition v. FTC, 517

F.2d 485 (7th Cir. 1975) .............................................. 14

Packer Corp. v. Utah, 285 U.S. 105 (1932) ................... 17

Pittsburgh Press Co. v. Pittsburgh Commission on

Human Relations, 413 U.S. 376 (1973) .......... .....10,11,13

Public Utilities Comm’n v. Pollack, 343 U.S. 451 (1952) 17

Railway Mail Assoc, y. Corsi, 326 U.S. 88 (1945) ....... 9

Rockville Reminder, Inc. v. United States Postal Ser

vice, 480 F.2d 4 (4th Cir. 1973) ................................... 12

Rosenfeld v. New Jersey, 408 U.S. 901 (1972) ........... 18

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Co., 409

U.S. 205 (1972) ................................................................5,14

United States v. Bob Lawrence Realty, Inc., 474 F.2d

115 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 414 U.S. 826 (1973) .....12,14

United States v. Hunter, 459 F.2d 205 (4th Cir.), cert.

denied, 409 U.S. 934 (1972) ................... .................. 12,13

United States v. Mintzes, 304 F. Supp. 1305 (D. Md.

1969) .................................................................................. 14

United States v. Mitchell, 335 F. Supp. 1004 (N.D.

Ga. 1971) ..........................................................................4,14

United States v. Re, 336 F.2d 306 (2d Cir), cert, denied,

370 U.S. 904 (1964) ...................................................... 15

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Development Corp., No. 75-616 (January 11, 1977) .... 7

Virginia State Board of Pharmacy v. Virginia Citizen’s

Consumer Council, 425 U.S. 748 (1976) .....................10,14

Williamson v. Lee Optical, 348 U.S. 483 (1958) ........... 14

Young v. American Mini Theatres, — — U .S .------ , 49

L.Ed. 310 (1976) .......................................................... 11,14

Zuch v. Hussey, 394 F. Supp. 1028 (E.D. Mich. 1975) .... 14

PAGE

1Y

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes:

First Amendment .......................................... 3, 9,10,11,12,13

Fourteenth Amendment .................................................... 3, 9

Thirteenth Amendment...................................................... 3, 9

23 U.S.C. § 131 .................................................................... 17

42 U.S.C. § 3601 .................................................................. 1

42 U.S.C. § 3604 .................................................................. 12

42 U.S.C. § 3604(c) ............................................................ 13

42 U.S.C. § 3604(e) ............................................... 5,12

42 U.S.C. § 3609 .................................................................. 6

42 U.S.C. § 3610 .................................................................. 6

42 U.S.C. § 3612 .................................................................. 6

42 U.S.C. § 3615 .................................................................. 6

42 U.S.C. § 3616 .................................................................. 6

Other Authorities:

112 Cong. Eec. (1966) ...................................................... 5,7

114 Cong. Eec. (1968) ...................................................... 5,6

Hearings on S.13-58, S.2114 and S.2280 Before the

Subcomm. on Housing and Urban Affairs of the

S.Comm. on Banking and Currency, 90th Cong. 1st

Sess. (1967) ...................................................................... 5

Note, Developments in the Law—Deceptive Advertis

ing, 80 Harv. L. E ev. 1005 (1970) .............................. 15

U.S. Commission on Civil Eights, Twenty Years After

Brown: Equal Opportunity in Housing (1975) ....... 1

U.S. Commission on Civil Eights, Equal Opportunity

in Suburbia (1974) .......................................................... 2

PAGE

I n t h e

(Court of tljr IniM States

October Term, 1975

No. 76-357

L inmark A ssociates, I nc., et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

T he T ownship of W illingboro, et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR TH E THIRD CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE

Interest of Amicus Curiae*

The N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., is a non-profit corporation, incorporated under the

laws of the State of New York in 1939. It was formed to

assist black persons to secure their constitutional rights

by the prosecution of lawsuits. The Legal Defense Fund

receives many requests for assistance in the enforcement

of fair housing laws, and seeks to advance the national

policy of “ fair housing through the United States,” 42

U.S.C. § 3601, in both federal and state courts.

Today integrated communities like Willingboro are beset

with tensions and threat of instability created by “ block

* Letters of consent to the filing of this brief from counsel for

the petitioners and the respondents have been filed with the Clerk

of the Court.

2

busting” which lead to racial segregation, damaging en

tire communities. The fair housing laws seek to prevent

the harm done by blockbusting and sanction efforts by all

levels of government to this end. Willingboro’s effort to

preserve integration and stability is an instance of such

enforcement at the local level. Indeed, early attention by

local authorities may be the best and perhaps only effec

tive remedy for blockbusting; it may be impossible to re

verse the processes of panic and resegregation once under

way.

ARGUMENT

Introduction

Although amicus’ position in this case is that the ordi

nance prohibiting for sale signs is a valid enactment, it

must be emphasized that such may not always be the case.

Under other circumstances such an ordinance may result in

barring blacks from equal access to housing. For example,

in an all-white community where realtors control the hous

ing market, the only way prospective black purchasers

may be able to find houses is to tour the area looking for

“ for sale” signs.

In short, no absolute rule that these ordinances either

are or are not valid is possible. In each case, the courts

must carefully weigh a variety of factors, including the

state of integration of the community, the accessibility of

housing through realtors or newspaper advertising, and

the history of the enactment of the ordinance in question.

As we shall show below, the proper result in this case is

to uphold the ordinance. In doing so, we urge that the

Court .should provide guidance to the lower courts to assist

them in striking a proper balance between two purposes

of the Fair Housing Act; ensuring full access to housing,

and preventing the destructive effects of blockbusting.

3

Summary of Argument

The standard for determining the constitutionality of

the Willingboro ordinance banning “ for sale” and “ sold”

signs on residential property must accommodate the State’s

obligation to protect the right of black citizens to equal

access to housing and the right of all Americans to open

integrated communities, guaranteed by the Thirteenth and

Fourteenth Amendments. The proper inquiry is (1) does

the ordinance have a segregative effect; and (2) was the

ordinance enacted to prevent the destructive segregating

effects of fear and panic selling rather than to exclude

minorities from residing in the community; the appeals

court determination that the Willingboro ordinance was

adopted pursuant to the town’s obligations under the Thir

teenth Amendment and Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment is clearly correct. The ordinance

neither had the effect of nor was it intended to create

racial segregation. On the contrary, it preserves racial

integration in Willingboro. From this perspective, the

ordinance’s restriction of commercial speech does not vio

late the First Amendment.

I.

The Willingboro Ordinance Enforces the Fair Hous

ing Guarantee of the Thirteenth Amendment and the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

A. The National Fair Housing Guarantee.

The Commission on Civil Rights’ most recent report on

fair housing finds that “ [s]evere residential segregation

and isolation between races and ethnic groups is a marked

feature of virtually every metropolitan area in which

minorities reside,” 1 and that when blacks move to suburban

1 U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Twenty Years After Brown:

Equal Opportunity in Housing 119 (1975). See also Linmark As

4

communities they frequently find themselves in black en

claves which border central city neighborhoods.2 “ [R]eal

estate agents have abetted th[e] process of racial change

by playing on white fears and prejudices and inducing panic

selling by whites . . . in countless neighborhoods across the

Nation.” 3

“First, a sense of panic and urgency immediately grips

the neighborhood and rumors circulate and recirculate

about the extent of the intrusion (real or fancied), the

effect on property values and the quality of education.

Second, there are sales and rumors of sales, some true,

some false. Third, the frenzied listing and sale of

houses attracts real estate agents like flies to a leaking

jug of honey. Fourth, even those owners who do not

sell are sorely tempted as their neighbors move away,

and hence those who remain are peculiarly vulnerable.

Fifth, the names of successful agents are exchanged

and recommended between homeowners and frequently

the agents are called by the owners themselves, if not

to make a listing then at least to get an up-to-date

appraisal. Constant solicitation of listings goes on by

all agents either by house-to-house calls and/or by

mail and/or by telephone, to the point where owners

and residents are driven almost to distraction.” 4

The real estate industry’s use of “ for sale” and “ sold”

signs is a critical ingredient in “panic selling” for such

signs tend “ no less than overt blockbusting practices, to

undermine any hope of . . . [racial] stability. Once this

sociates, Inc. v. Township of Willingboro, 535 F. 2d 786, 789 n. 1;

see also U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Equal Opportunity in

Suburbia 64 (1974).

2 Id.

3 Id. at 9.

4 United States v. Mitchell, 335 F. Supp. 1004, 1006 (N.D. Ga.

1971).

5

hope is lost and complete racial transformation appears

inevitable, even those desiring to remain are virtually

forced to sell.” BarricTc Realty, Inc. v. City of Gary, Indi

ana, 354 F. Supp. 126, 135 (N.D. Ind.), aff’d, 491 F. 2d 161

(7th Cir. 1974). Ordinances banning such signs “ remove a

significant source of panic selling pressure from those who

wish to remain in the . . . neighborhood.” 354 F. Supp.

at 135.5

Congress has clearly aligned the Nation with the resi

dents of Willingboro in §804(e) of Title V III of the Civil

Eights Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C. §3604(e), which makes it

unlawful “ [f]or profit, to induce or attempt to induce any

person to sell or rent any dwelling by representations

regarding the entry or prospective entry into the neighbor

hood of a person or persons of a particular race, color,

religion or national origin.” Legislative history indicates

that Congress used the strongest language to condemn the

effects of blockbusting in creating “new ghettos” ,6 and

recognized that the community suffered substantial injury

from racially discriminatory housing practices, Trafficante

v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Co., 409 U.S. 205, 210

(1972).

Although Title V III is “ a detailed housing law, appli

cable to a broad range of discriminatory practices and

5 See infra.

6 The antiblockbusting provision was introduced by Bepresenta-

tive Bingham as an amendment to Title IY of the Civil Bights Act

of 1966, the predecessor to Title VIII which passed the House but

not the Senate, 112 Cong. Bee. 18177 (1966), in order to overcome

the “ two evil results” of realtor windfall profits and “creating in

the end a new black ghetto.” Blockbusting was described as “one of

the most evil situations accompanying and causing and flowing

from segregation in housing” , id. at 18178. Senator Mondale, the

foremost proponent of Title V lII, compared blockbusting to “pro

fit [ing] by booking young people with drug addiction” and “steal

ing wheelchairs from crippled children; it is as bad as you can

think of . . . ” Hearings on S. 1358, S. 2114 and S. 2280 Before the

Subcomm. on Housing and Urban Affairs of the S. Comm, on

Banking and Currency, 90th Cong. 1st Sess. at 118 (1967). See

also 114 Cong. Bee. 2273, 2275, 2692-2696, 2704, 2992 (1968).

6

enforceable by a complete arsenal of federal authority,” 7

the coordinate enforcement role of state and local author

ities is recognized and made part of the statute’s enforce

ment scheme. § 815 of Title VIII, 42 U.S.C. § 3615, ex

pressly provides that Title V III is not meant to preempt

any state or local antidiscrimination measure “ that grants,

guarantees, or protects the same rights as are granted by

this Title.” Although “ the authority and responsibility for

administering this Act shall be in the Secretary of Housing

and Urban Development,” the Secretary “ shall consult with

State and Local officials . . . .” ;8 and Title V III carefully

integrates state and local enforcement authority into the

very “ arsenal of federal authority” in the enforcement

provisions of Title V III.9

Senator Mondale emphasized the need to supplement the

increasing number of state and local government fair hous

ing laws in introducing the Mondale-Brooke bill: “ These

scattered and local developments, far from absolving us

from action, make it even more important than before that

Congress enact a national fair housing law that will place

all States and all localities upon an equal footing.” 10 With

respect to the antiblockbusting provision in § 804(e), 42

U.S.C. § 3604(e), legislative history is specific that anti

blockbusting measures of state and local authorities, in

7 Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409, 417 (1968).

8 § 809, 42 U.S.C. § 3609; see also § 816, 42 U.S.C. § 3616.

9 See §§ 810 and 812, 42 U.S.C. §§ 3610 and 3612.

10 114 Cong. Rec. 2277; compare 2273, 2274, 2992 and 9554.

Senator Mondale echoed Attorney General Clark’s comments in

hearing.

“ This legislation . . . would not in any way interfere with State

and local governments in their efforts to enforce their laws.

On the contrary, it would be designed to encourage and vital

ize those efforts. And it would provide for the Secretary of

Housing and Urban Development to encourage and support

state and local governments in the enforcement of their laws

and in the conduct of their affairs under those laws.”

Hearings on S. 1358, S. 2114 and S. 2280 Before the Subcomm.

on Housing and Urban Affairs of the S. Comm, on Banking and

Currency, supra, p. 15.

7

eluding, “provisions . . . which go into the same thing”

are permitted and encouraged under the act.11

B. The Willingboro Ordinance.

Willingboro Ordinance No. 5-1974 is a legislative mea

sure consistent with Title VIII. The history of the town,

the sequence of events preceding enactment of the ordi

nance, and its impact compel the conclusion that the pur

pose of the measure was to control incitement of I’acial

fears and panic selling induced by realtors’ use of “ for

sale” and “ sold” signs. See Village of Arlington Heights

v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., No. 75-616

(January 11, 1977), slip op. at 11-15.

After racial exclusion by the developer of Willingboro

was enjoined,12 the town committed itself to becoming

racially integrated.13 However, shortly before the passage

of the ordinance, residents became increasingly preoccu

pied with racial problems and fears of resegregation. Con

cern was expressed that local newspapers had published

articles about racial tensions, blockbusting, and an influx

of blacks into the community.14 *

The Willingboro Human Relations Commission recom

mended the ordinance because investigations demon

strated that realtors’ use of “ for sale’’ and “ sold” signs

had induced widespread fear and panic selling.16 Those

recommendations were endorsed by organizations devoted

11112 Cong. Rec. 18177 (colloquy between Rep. Bingham and

Rep. Colmer). See Appendix A, State and Local Anti-Panic Sell

ing Provisions.

12 Levitt and Sons, Inc. v. Division Against Discrimination in

State Department of Education, 31 N.J. 514, 158 A. 2d 177, appeal

dim., 363 TJ.S. 418 (1960).

13 See discussion at 535 F. 2d 786, 789.

14 Joint Appendix, pp. 51a, 96a.

16 Joint Appendix, pp. 233a, 234a-336a (Gladfelter); 239a-240a,

244a (Porter); 247a-248a, 251a (Lyght).

8

to civil rights, including the N.A.A.C.P.16 At public hear

ings held by the Township Council to consider the ordi

nance, “ [c]omplaints were stated regarding phone calls,

letters and house-to-house solicitations by realtors inquir

ing whether the home owner wishes to sell;17 about panic

selling;18 about ‘sold’ signs remaining up for six weeks

in violation of an ordinance requiring their removal in five

days (in response to which Council members cited the great

difficulty of enforcement) ;19 about the ‘forest’ of signs,

which created the impression ‘that there was something

wrong with the community’,20 21 and consequent departure

of persons who might otherwise have remained.” 21 535

F.2d at 791.

After two years of investigation, the Township Council

enacted the ordinance. We submit that the record is crucial

to resolution of this case and there is no evidence in the

record to support the claim that the impact of the ordinance

has been to discriminate against black home purchasers.

And, of course, segregation is not its purpose. Indeed, the

purpose was the opposite—maintenance of integration.

Real estate agents testified at trial that sales had not

diminished.22 Willingboro public school enrollment statis

tics, which the court may judicially notice, show that the

absolute number of black students has continued to increase

18 535 F. 2d at 793-794, n. 6. At the hearing, community resi

dents were proponents of the ordinance while the real estate indus

try was its major opponent.

17 See, e.g., Joint Appendix, pp. 46a, lOOa-lOla.

18 See, e.g., Joint Appendix, p. 102a; see also pp. 158a, 162a-163a.

19 See, e.g., Joint Appendix, pp. 34a-35a, 39a, 85a, 89a, 90a, 93a-

94a, 109a.

20 See, e.g., Joint Appendix, pp. 44a-45a, 63a-64a, 71a, 90a, 92a,

93a, 105a, 113a-114a.

21 See, e.g., Joint Appendix, p. 102a. Blockbusting was also

raised. See id. at 96a, I l i a ; see also 158a,

22 Joint Appendix, p. 163a.

9

after enactment of the ordinance, both systemwide and in

almost every school.23

That the ordinance was enacted to prevent panic selling

does not mean that an identical ordinance might not be

passed elsewhere in order to exclude blacks or to have that

effect. However, Willingboro is not a community which

has no black residents, the ordinance was not passed in

response to the entry of the first black family or families

into the community, nor has the impact been to exclude

black homeseekers from living in the township.24 No facts

which would support a finding of unconstitutionality under

the Thirteenth Amendment and the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment are present here.

In the absence of such a finding, “a State may choose to

put its authority behind one of the cherished aims of

American feeling by forbidding indulgence in racial . . .

prejudice to another’s hurt.” 25 To use the First and Four

teenth Amendments “ as a sword against such State power

would surely stultify” 2S the national open housing policy.

23 Brief For Respondent, Exhibit A.

24 Compare discussion concerning Medford Lakes at 535 F. 2d

at 803 n. 27, 811.

25 Railway Mail Assoc, v. Corsi, 326 U.S. 88, 98 (1945) (Mr.

Justice Frankfurter concurring).

26 Id.

10

II.

The Willingiboro Ordinance Is an Appropriate Means

of Thwarting Panic Selling to Preserve an Integrated

Community and Does Not Offend the First Amend

ment.

Unlike political and ideological dialogue, the posting of

“ for sale” signs is commercial product advertising which

does “no more than propose a commercial transaction,”

Pittsburgh Press Co. v. Pittsburgh Commission on Human

Relations, 413 U.S. 376, 385 (1973).27 This Court has con

sistently recognized that significant distinctions between

commercial advertising and other types of speech support

the need for differences in the degree and type of permis

sible regulation in each category. Virginia State Board of

Pharmacy v. Virginia Citizen’s Consumer Council, 425 U.S.

748 (1976); Bigelow v. Commonwealth of Virginia, 421 U.S.

809 (1975).

Moreover, unlike the statute in Pittsburgh Press, the

Willingboro ordinance does not ban all advertisement of

homes which are for sale, but rather allows such advertis

ing by all means other than the posting of “ for sale” signs

on residential property. The fear expressed in Virginia

Board of Pharmacy that a commercial message will not

reach consumers is substantially weakened where the reg

ulation only encompasses one of many channels of com

munication.28 Indeed, at the trial which occurred nine

27 The advertising here is distinguishable from the advertisement

in Bigelow v. Virginia, supra, which announced the availability of

legal abortions in New York and “contained factual material of

clear ‘public interest’ ” . Id. at 822, or from other types of commer

cial advertisements which contain public interest elements. See

Virginia Pharmacy Board v. Virginia Citizens’ Consumer Council,

supra, 425 U.S. at 760-761 and cases cited therein.

28 Prior to the enactment of the ordinance, the real estate indus

try advertised by word of mouth and by newspaper advertisements.

The majority of its business came from these sources, not from

signs. Joint Appendix, pp. 33a, 36a.

11

months after the ordinance was passed and “ for sale” signs

had disappeared from Willingboro, witnesses testified

that sales of homes had not diminished. Thus, as the Court

noted in Young v. American Mini Theatres, “ [vjiewed as

an entirety, the market for the commodity is essentially

unrestricted,” ------U .S .--------, 49 L.Ed. 310, 321 (1976).

The analysis of the protection accorded commercial

speech under the First Amendment has involved a careful

balancing of the interests in each case. The interest of a

community in protecting a seldom-achieved racial integra

tion and in preventing the destructive segregating effects

of a panic selling and blockbusting clearly outweighs the

desire of real estate brokers to advertise by one particular

method.29

29 Suggestions in the briefs of petitioners and the American Civil

Liberties Union as amicus curiae that the proper standard of re

view is the “clear and present danger” test or a “substantial govern

mental interest” test find no support in the Court’s opinions.

The clear and present danger test, most recently refined in

Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969), was formulated in

cases arising under criminal syndicalism statutes which sought to

punish on the basis of an individual’s political beliefs. Because the

freedom to possess such beliefs forms the core of First Amendment

values, the principle emerged that “ [t]he constitutional guarantees

of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or

proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except

where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent

lawless action and is likely to incite such action.” Id. at 447.

Nor is the rigid application of a “substantial governmental in

terest” test warranted. The touchstone of this Court’s opinions in

the commercial speech area has been flexibility; the varying types

of commercial speech necessitate a separate consideration of all

issues in each case. For example, as the Court noted, some adver

tisements contain “factual material of clear ‘public interest’.”

Compare Bigelow v. Virginia, supra, 421 U.S. at 822 with Pitts

burgh Press Co. v. Pittsburgh Commission on Hum. Bel., supra.

The burden of justifying regulation of the former may well have

to be greater than the burden of justifying restriction on the latter,

since “ [t]he question whether speech is, or is not, protected by the

First Amendment often depends on the context of the speech” and

“ [e]ven within the area of protected speech, a difference in context

may require a different governmental response.” Young v. Ameri

can Mini Theatres, supra, 49 L. Ed. 2d at 323, 324.

12

A. The Ban on “ For Sale” and “ Sold” Signs Is Closely

Related to Illegal Discrimination in Housing.

The question of “ the precise extent to which the First

Amendment permits regulation of advertising that is re

lated to activities the State may legitimately regulate or

even prohibit” was explicitly left open in Bigelow v. Vir

ginia, supra, 421 U.S. at 825. This Court observed, id. at

825, n. 10:

“We have no occasion, therefore, to comment on deci

sions of lower courts concerning regulation of adver

tising in readily distinguishable fact situations. Wholly

apart from the respective rationales that may have

been developed by the courts in those cases, their re

sults are not inconsistent with our holding here. In

those cases there usually existed a clear relationship

between the advertising in question and an activity

that the government was legitimately regulating. See,

e.g., United States v. Bob Lawrence Realty, Inc., 474

F.2d 115, 121 (CA5), cert, denied, 414 U.S. 826, 38

L. Ed. 2d 59, 94 S. Ct. 131 (1973). Rockville Reminder,

Inc. v. United States Postal Service, 480 F. 2d 4 (CA2

1973); United States v. Hunter, 459 F. 2d 205 (CA4),

cert, denied, 409 U.S. 934, 34 L. Ed. 2d 189, 93 S. Ct.

235 (1972).”

The ban on “ for sale” signs is not only related to, but

specifically directed against, panic selling prohibited by the

Fair Housing Title of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, 42

U.S.C. § 3604. United States v. Bob Lawrence Realty,

supra, one of the cases cited in Bigelow, upheld the con

stitutionality of § 3604(e) of the Fair Housing Title, which

forbids blockbusting.

“ Congress was aware that as laudable and necessary

as the profit motive might be for our socio-economic

system, it must on occasion yield to more humane and

13

compassionate mores which are inherent in the system

itself, and necessary for survival.” 30

The court in another case cited in Bigelow rejected a First

Amendment challenge to the Fair Housing- Title’s pro

scription against discriminatory advertising, § 804(c), 42

U.S.C. § 3604(c). United States v. Hunter, supra.

Because of their success at manipulating racial fears,

blockbusting practices “ . . . constitute a fundamental

element in the perpetration of segregated neighborhoods,

racial ghettos and the concomitant evils which have been

universally recognized to emanate therefrom.” 31 The wide

spread posting of “for sale” signs is as intimately related

as any other tactic of blockbusting to aggravation of racial

hysteria, and setting in motion panic selling and resegrega

tion in communities.

In Pittsburgh Press Co. v. Pittsburgh Commission on

Human Relations, supra, a prohibition on publishing em

ployment advertisements in sex-designated columns was

challenged on First Amendment grounds. In upholding the

prohibition, this Court stated:

“Any First Amendment interest which might be served

by advertising an ordinary commercial proposal and

which might arguably outweigh the governmental in

terest supporting the regulation is altogether absent

when the commercial activity itself is illegal and the

restriction on advertising is incidental to a valid limi

tation on economic activity.” 32

The justification for the regulation lay not in the fact that

the advertising explicitly violated a federal or local law,

30 Id., 474 F. 2d at 119.

31 Brown v. State Realty Co., 304 F. Supp. 1236, 1240 (N.D. Ga.

1969).

32 413 TJ.S. at 389.

14

but rather it “ signaled that the advertisers were likely to

show an illegal sex preference in their hiring decisions.”

Id. So, too, the prevalence of “ for sale” signs signals the

incitement of racial panic inimical to the existence of “ truly

integrated and balanced living patterns,” Trafficante v.

Metropolitan Life Insurance Co., 409 U.S. 205, 211 (1972)

which the Fair Housing Title seeks to achieve.83

B. The Proliferation of “ For Sale” and “ Sold” Signs

in a Racially Tense Community Broadcasts a

Threatening and Deceptive Message.

In Virginia Pharmacy Bd. v. Virginia Citizen’s Consumer

Council, supra, 425 U.S. at 771, this Court stated: “We see

no obstacle to a state dealing effectively” with the problem

of “commercial speech [which] is not probably false, or

even wholly false, but only deceptive or misleading.” Such

regulation is not uncommon. Where the potential for de

ception exists, this Court has consistently sustained pro

hibitions on advertising by certain professions. Head v.

Board of Examiners, 374 U.S. 424 (1960) (optometrists);

Williamson v. Lee Optical, 348 TJ.S. 483 (1958) (eyeglass

fram es); see Virginia Pharmacy Bd. v. Virginia Citizen’s

Consumer Council, supra, 425 U.S. at 773, n. 25. The

power of the Federal Trade Commission to prohibit mis

leading as well as false statements in labeling and ad

vertising “has long been recognized,” Young v. American

Mini Theatres, supra, 49 L. Ed. 2d at 328, n. 31,* 34 and the

authority of the Securities and Exchange Commission to

regulate information disclosed in stock solicitations is

83 See, e.g., Barrick Realty, Inc. v. City of Gary, Indiana, supra,

354 F. Supp. at 135; United States v. Bob Lawrence Realty, supra;

United States v. Mitchell, 335 P. Supp. 1004, 1006 (N.D. Ga. 1971);

United States v. Mintzes, 304 F. Supp. 1305 (D. Md. 1969); Zuch

v. Hussey, 394 P. Supp. 1028, 1033, n. 7 (E.D. Mich. 1975).

34 See, e.g., Jacob Siegel Co. v. PTC, 327 U.S. 608 (1946); Don

aldson v. Read Magazine, Inc., 333 U.S. 178 189 (1948); National

Commission on Egg Nutrition v. PTC, 517 P. 2d 485 (7th Cir.

1975) ; E. F. Drew & Co. v. FTC, 235 P. 2d 735, 740 (2d Cir. 1956).

15

settled, United States v. Re, 336 F. 2d 306 (2d Cir.), cert,

denied, 370 TJ.S. 904 (1964). And while there is a chal

lenge to laws barring advertising by, for example, law

yers, there seems to be no serious claim that such advertis

ing may be conducted totally unrestrained as to time, place

and manner.

“ For sale” signs are obviously not literally false ad

vertising when placed in front of houses currently on the

market.35 However, regulation is permissible to prevent

the more subtle but often graver evils caused by messages

which, although literally true, convey underlying illegal

or antisocial meanings. For example, to determine whether

an advertisement is deceptive or misleading and subject

to regulation or prohibition, the FTC employs a standard

that is based not on proof of actual falsehood but on the

“ capacity to deceive” the typical audience which will re

ceive the message. See, e.g., Charles of the Ritz Distribs.

Corp. v. FTC, 143 F.2d 676, 680 (2d Cir. 1944); Note, De

velopment in the Law—Deceptive Advertising, 80 Habv. L.

R ev., 1005, 1040, et seq. (1970).

That whether a message is deceptive depends on the

particular context in which it is delivered is also clear in

the area of labor relations. In NLRB v. Gissel Packing

Co., 395 U.S. 575, 619 (1969), the question whether an

employer’s statements were misleading or coercive and, as

a result an unfair labor practice, turned not on the literal

language of the speech but “ on the question: “ [W]hat did

the speaker intend and the listener understand ?” In Gissel,

this Court reasoned that:

“ . . . any balancing [of the employer’s right of free

speech against the employees’ right to associate] must

35 They became false, however, if allowed to remain in front of

property that has been sold, a practice prevalent in Willington

prior to the enactment of the ordinance. Joint Appendix, p. 38a.

Signs often remained up for weeks after houses were sold. Joint

Appendix, p. 34a.

16

take into account the economic dependence of the em

ployees on their employers, and the necessary tendency

of the former, because of that relationship, to pick up

intended implications that might be more readily dis

missed by a more disinterested ear.” Id. at 617.

“ [T]he understood impact” of “ for sale” signs can only

be viewed in the context of the racial tensions in suburban

communities, the various uses for which real estate brokers

employ “ for sale” signs, and the actual reactions of the

Willingboro residents to the practices of the real estate

industry.36 Within this context, “ for sale” signs convey not

merely a notice of available housing, but a threat to white

homeowners which preys on their racial fears, induces

panic selling, fosters blockbusting and invites resegrega

tion.

C. “For Sale” and “Sold” Signs Are Thrust Upon

a Captive Audience.

As destructive as the message conveyed by the “ for sale”

signs is, the continual bombardment of the message on the

public is impossible to avoid.37 Given the community’s

physical layout, a drive through any residential section of

Willingboro would subject a person to a “ forest” of signs.

This Court has recognized that “ restrictions have been

upheld . . . when the degree of captivity makes it im

practical for the . . . viewer . . . to avoid exposure,” Erznos-

nik v. City of Jacksonville, 422 U.S. 205, 209 (1976). Mr.

Justice Douglas stated, “ [w]hile petitioner clearly has a

right to express his views to those who wish to listen, he

has no right to force his message upon an audience in

38 See supra, Point I.

37 As the Court of Appeals observed, Willingboro dwellings were

built in a line, as is typical of Levitt developments, with each house

placed the same distance from the street on lots having 60-70 foot

street footage.

17

capable of declining to receive it,” Lehman v. City of

Shaker Heights, 418 U.S. 298, 307 (1974) (Mr. Justice

Douglas, concurring).

The Willingboro ordinance in no way restricts the place

ment of “ for sale” advertisements in newspapers; it does

not prevent word of mouth or other dissemination. It only

restricts display signs. As Mr. Justice Brandeis stated for

a unanimous court in Packer Cory. v. Utah, 285 U.S. 105,

110 (1932):

“ . . . [Tjhere is a difference which justifies the classifica

tion between display advertising and that in periodicals

or newspapers . . . Advertisements of this sort are

constantly before the eyes of observers on the streets

. . . without the exercise of choice or violation on their

part . . . In the case of newspapers and magazines,

there must be some seeking by one who is to see and

read the advertisement. The radio can be turned off,

but not so the billboard or . . . streetcar placard.”

And, just like those for whom a public transit system is the

necessary mode of transportation, the residents of suburban

Willingboro use the streets, “ as a matter of necessity, not

of choice.” Public Utilities Comm’n. v. Pollock, 343 U.S.

451, 468 (1952) (Mr. Justice Douglas, dissenting), cited

with approval in Lehman v. City of Shaker Heights, supra,

418 U.S. at 302.

Regulation of billboards on streets is not unprecedented.

A state statute may permit highway billboards to advertise

businesses located in the neighborhood, but not elsewhere.

Markham Advertising Co. v. State, 73 Wash. 2d 405, 439

P.2d 248, appeal dism., 393 U.S. 316 (1969). The Highway

Beautification Act of 1965, 23 USC § 131, 23 U.S.C.A. § 131,

authorizes states to adopt regulations which may signif

icantly curtail use of such signs. If concern for aesthetics

warrants regulation of placard advertisements, the national

18

goal of open housing and prohibition of blockbusting de

mand no less. Exposure to “ for sale” and “ sold” signs is

of a qualitatively different nature than the exposure to the

offending jacket in Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15, 21

(1969), where the public could “ effectively avoid further

bombardment of their sensibilities simply by averting their

eyes.” The ordinance’s restriction of “ for sale” signs is a

justifiable method of preventing the use of the signs’

deliberate “ [visual] assault” on the public as a tool in

panic selling.38

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, amicus curiae urges the Court

to affirm the judgment of the appeals court.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

Charles S tephen- R alston

Melvyn R. L eventhal

B ill L ann Lee

L inda S. Greene

Beth J. L iep

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae,

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

_ 88 Bosenfeld v. New Jersey, 408 TJ.S. 901, 906 (1972) (Mr. Jus

tice Powell, dissenting), quoted with approval in Erznoznik v. City

of Jacksonville, supra, 422 TJ.S. at 210 n. 6.

A P P E N D I X

la

APPENDIX A

State and Local Anti-Panic Selling Provisions

Before and since passage § 804(e) of Title V III of the

Civil Rights Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C. § 3604(e), states and

localities have enacted a variety of measures to counter

blockbusting or panic selling by attacking different aspects

of the process. Title V III’s approach of banning, inter alia,

representations regarding the entry into the neighborhood

of persons of a particular race or color made for profit, in

fact, is based on laws in effect in Ohio and Maryland.1 With

respect to such laws, several states expressly prohibit in

direct as well as direct reference to neighborhood transi

tion,2 some specify the kind of representations prohibited,3

and some do not limit representations only to those made

“ for profit.” 4 Some states and localities provide compen-

1112 Cong. Rec. 18177 (Rep. Bingham), see e.g., Md. Ann. Code

Art. 56, § 230A (1968); Ohio Rev. Code Ann. §4112.02 (Supp.

1970); Minn. Stat. Ann. § 363.03(2) (4) (Supp. 1971); Chicago

Beal Estate Board v. City of Chicago, 36 111. 2d 530, 533-534, 224

N.E. 2d 793, 797 (1967).

2 See, e.g., Mich. Stat. Ann. § 26.1300 (203) (1970).

3 See supra, n. 1. Representative Bingham’s original amend

ment to H.R. 14765 specifically prohibited the following represen

tatives: “lowering of real estate values in the area concerned,”

“ deterioration in the character of the area concerned,” “an increase

in criminal or anti-social behavior in the area concerned,” and “a

decline in the quality of the schools or other public facilities serv

ing the area.” See 112 Cong. Rec. 18179-18180.

4 See, e.g., 111. Am. Stat. ch. 38, § 70-51 (b )-(c ) (Smith-Hurd

Supp. 1971); Md. Ann. Code art. 56, § 230A (Supp. 1970); Ohio

Rev. Code Ann. § 4112.02 (H) (9) (1970); Wis. Stat. Ann.

§101.60(2m) (Supp. 1971); Annapolis, Md. City Code §8-3(a)

(5) (1970) ; Buffalo, N.J., Ordinance § 350 (1970) ; Detroit, Mich.,

Code § 39-1-13.1 (1970); Evanston, 111, Code § 25-%-6 (1970);

Green Bay, Wis., Code of Gen. Ordinances ch. 32.05 (1968); Okla

homa City, Okla. Ordinance 11,848 (1969); Teaneck, N.J. Ordi

nance 1274 (1966).

2a

Appendix A

satory relief such as damages,5 while others specify in

junctive relief,6 criminal sanction,7 or license revokation.8

Other statutes or ordinances prohibit door-to-door solicita

tion made without the consent of the homeowner9 or sus

pend solicitation for a period where blockbusting is

threatened.10 Other provisions prohibit incitement, har-

rassment, intimidation, threats or other conduct that in

duces panic selling.11

“Local ordinances have been passed to eliminate one of

the blockbuster’s major weapons by regulating the size

and location of ‘for sale’ signs so as to limit their capacity

to induce panic.” 12 Some localities limit the time a ‘for

5 See, e.g., N.Y. Exee. Law § 297 (McKinney Supp. 1970).

6 See, e.g., Kan. Stat. Ann. § 44-1022 (Supp. 1971); N.Y. Exee.

Law § 297(6) (McKinney Supp. 1970); Alexandria, Va, Code

§ 17A-4 (1969) ; Green Bay, Wise., Code of Gen. Ordinances eh.

32.05 (1968).

7 See, e.g., Md. Ann. Code at art. 56, § 230A (1968) ; Wis. Stat.

Ann. §101.60(6) (Supp. 1971); Mich. Stat. Ann. § 26.1300 412

(1970).

8 See, e.g., Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. §§ 20-320(11), -328 (1969);

D.C. Code Ann. § 45-1403 (1967) ; N.Y. Exec. Law § 296(3) (Mc

Kinney Supp. 1969).

9 See, e.g., Summer v. Township of Teaneck, 53 N.J. 548, 251

A.2d 761 (1969) (Teaneck ordinance requiring permit upheld);

cf. Breard v. City of Alexandria, 341 U.S. 622 (1951).

10Dayton Ordinances, §§ 115-e (k), & 115-k; New York City

Admin. Code, eh. 1, Title C, Cl-l.Q et seq.; see Blockbusting A

Novel Statutory Approach To An Increasingly Serious Problem,

7 Colum. J. L. & So. Prob. 538 (1971).

11 Buffalo, N.Y., Ordinance ch. VII, art. XVIII, § 351(a)

(1970); Pa. Real Estate Comm’n Regulations 15.9, 15.10, Septem

ber 22, 1966; 111. Ann. Stat. ch. 38, § 70-51 (c) (Smith-Hurd Supp.

1971); Annapolis, Md. Code §8-3 (a) (5) (b) (1970).

12 Comment, Blockbusting, 50 Geo. L. J. 170, 173 (1970) ; see, e.g.,

Detroit, Mich. Ordinance 753-F, reprinted in 7 Race Rel. L. Rptr.

1256 (1962); Teaneck N.J., Ordinance 1157, reprinted in 7 Race

Rel. L. Rptr. 1262 (1962).

3a

Appendix A

sale’ or ‘sold’ sign may be posted. Willingboro, for instance,

before prohibiting signs altogether had a provision reg

ulating the size, restricting its placement within property

lines, and requiring that “ [s]uch signs shall be removed

within five days after the execution of any lease, rental

agreement or agreement of sale for the premises in ques

tion by the occupant of the premises and/or the owner

of the sign.” 13 It was widespread abuse of this ordinance

by realtors14 that led the Willingboro Township Council to

enact Ordinance No. 5-197415 which repealed the prior

ordinance. Prohibition of “ for sale” and “ sold” signs is

an approach adopted by other local authorities as well.16

Indeed, trial testimony indicates that Willingboro “con

tacted National Neighbors and found out that there were

some other communities throughout the country that have

done this type of ordinance,” 17 and then contacted one,

Shaker Heights, Ohio.18

13 Willingboro, N.J. Ordinance Chap. XVIII, § 17-6.5, reprinted

in Joint Appendix, p. 14a.

14 See, supra, p. 8, n. 19.

15 Joint Appendix, p. 27a.

16 See, e.g., Barrick Realty Inc. v. City of Gary, 354 F. Supp.

126 (N.D. Ind. 1973), affirmed, 491 F.2d 161 (7th Cir. 1974)

(Gary, Ind. Ordinance No. 4685 upheld) ; Chicago, 111. Mun. Code,

Ch. 198.7B and Ch. 113-28; Milwaukee Code of Ord. §16.3 (14.1)

(limited to licensed real estate brokers and salsemen).

17 Joint Appendix, p. 184a.

18 Id. at 184a-185a.

MEilEN PRESS INC — N. Y. C. 219