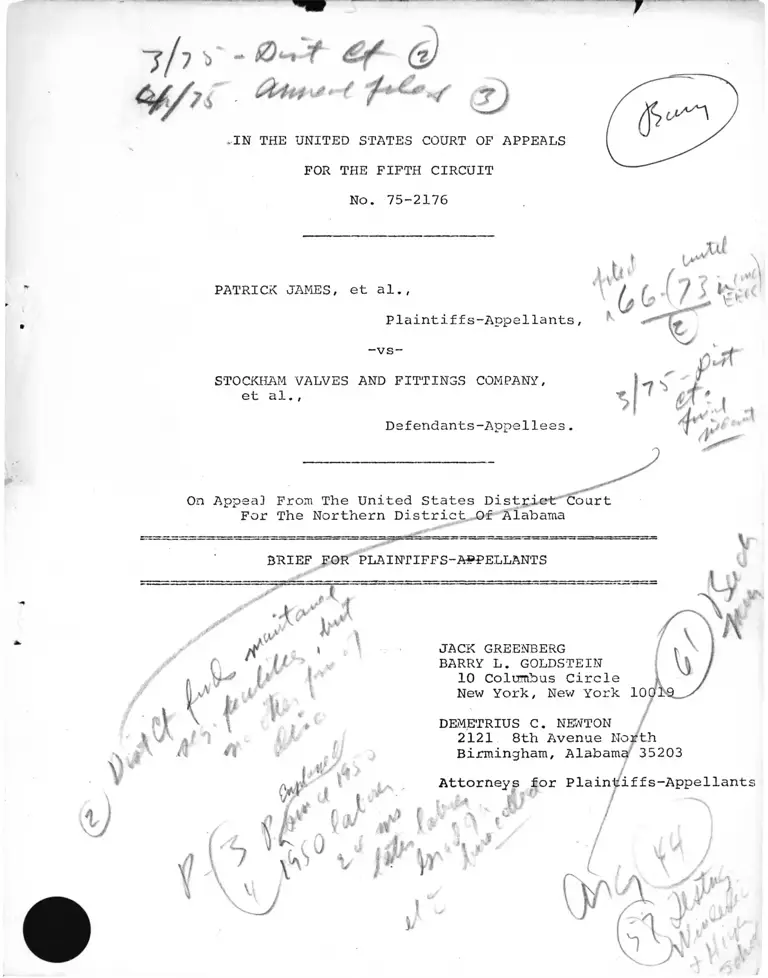

James v. Stockham Valves and Fittings Company Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. James v. Stockham Valves and Fittings Company Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1966. f6cbb410-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/853f5774-9f3f-4a5d-8aa0-5a21f42ac134/james-v-stockham-valves-and-fittings-company-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

'"j/?'* - t (?)

. foiit • / ' { /

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 75-2176

jlJ^' 7 ' t**1PATRICK JAMES, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

t

. jol .

-vs-

A

STOCKHAM VALVES AND FITTINGS COMPANY,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

5 7 V , ,

r s ^

On Appea] From The United States District Court

For The Northern District Of Alabama

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS , 5 v

Page

J. Clerical, Timekeeper, Sales

and Guard Positions.......................... 41

K. Black Employees Have Suffered

Economic Harm ............................... 42

ARGUMENT ..................................... 44

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING

TO AFFORD FULL INJUNCTIVE RELIEF

FROM THE MAINTENANCE OF SEGREGATED

FACILITIES, A DISCRIMINATORY

SENIORITY SYSTEM AND THE DISCRIMINA

TORY SELECTION OF EMPLOYEES FOR JOBS,

TRAINING PROGRAMS AND SUPERVISORY

POSITIONS ...................................... 44

A. The District Court Should be

Ordered to Enter an Injunction

Barring the Company from Main

taining Segregated Facilities

or Programs ................................ 44

B. The District Court Should be

Directed to Enter an Order Which

Remedies the Discriminatory Job

Assignment and Seniority Practices ........ 45

C. The District Court Should be

directed to Enter an Order

Which Would Provide for an

Affirmative Action Plan Designed

to Remedy the Discriminatory

Selection and Training Practices

for Craft and Supervisory Positions ........ 51

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING

TO FIND THAT STOCKHAM1S TESTING

PROGRAM WAS UNLAWFUL ........................... 54

A. It Was Unlawful for Stockham

to Have Imposed Testing Re

quirements on Blacks for

Promotion to Jobs From Which

They Had Previously Been

Excluded Other Than Those

Requirements Imposed On Their

White Contemporaries ....................... 54

B. The Wonderlic Test and the High

School Education Requirement Had

An Adverse Impact On Black

Employees, Were Not Validated

and Consequently Were Unlawfully

Used ....................................... 57

iv

Page

III. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING

TO FIND THAT STOCKHAM'S UNLAWFUL

EMPLOYMENT PRACTICES CAUSED BLACKS

ECONOMIC HARM AND IN NOT AWARDING

BACK PAY .......................................... 61

IV. THE PROCEDURE OF THE DISTRICT COURT

IN ADOPTING IN THEIR SUBSTANTIAL

ENTIRETY THE PROPOSED FINDINGS OF

FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW OF

DEFENDANT STOCKHAM IS SUSPECT ..................... 68

CONCLUSION ................................................. 70

Appendix A, Plaintiffs' Synopsis of

the Court's Opinion

Appendix B, Testimony of Company

Managers and Supervisors

and Colloquy Between the

Court and Counsel Con

cerning the General

Allocation of Jobs by Race

Appendix c. PX 94

Appendix D, PX 91

Appendix E, EEOC Guideline

Appendix F, PX 95

29 CFR § 1607.11

v

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 75-2176

PATRICK JAMES, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants

-vs-

STOCKHAM VALVES AND FITTINGS COMPANY,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED BY FIFTH CIRCUIT

__________LOCAL RULE 13 (a)___________

The undersigned, counsel of record for Plaintiffs-

Appellants, certifies that the following listed parties

have an interest in the outcome of this case. These repre

sentations are made in order that Judges of this Court may

evaluate possible disqualification or recusal pursuant to

Local Rule 13(a).

1. Patrick James, Howard Harville, and Louis Winston,

all plaintiffs.

2. The class of black employees of Stockham Valves

and Fittings Company, whom the plaintiffs re

present .

3. Stockham Valves and Fittings Company, defendant.

i

4 United Steelworkers of America and Local 3036

thereof, defendants.

Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants

- ii -

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Certificate Required by Local Rule 13 (a) .................. i

Table of Contents ............................. iii

Table of Authorities ...................................... vi

Note on Abbreviations ..................................... x

Statement of Issues Presented for Review ................. xi

STATEMENT OF THE CASE 1

STATEMENT OF FACTS 3

A. An Overview of the Parties and the

Operations .................................... 3

B. An Overview of the Discriminatory

Practices ..................................... 6

C. Segregated Facilities and Programs ............... 8

D. The Job Assignment and the Departmental

Seniority System .............................. 12

1. The Job and Pay Structure .................... 12

2. Departmental Seniority Structure ............. 14

E. The Racial Allocation of Jobs at

Stoekham ...................................... 16

F. The Racial Staffing by Departments

and by Jobs Within Departments ................ 21

1. The Predominantly Black or White

Departments ............................... 23

2. The "Racially Integrated"

Departments ............................... 29

G. Training Programs for Hourly Paid

Jobs: Apprentice and On-the-Job .............. 31

H. Training Programs for Supervisory Jobs

and the Selection and Recruitment

of Supervisors ................................ 34

I. Employee Testing Practices ....................... 37

- iii -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Page

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 43 UoS.L.W. 4880, 40, 55, 57

9 EPD 10,230 (June 25, 1975)................ 59, 60, 62

Anderson v. City of Albany, 321 F.2d 649 (5th Cir.

1963).... 45

Barnett v. W. T. Grant Co., 9 EPD 5[ 10,199

(4th Cir. 1975) .............................. 48, 58

Bolten v. Murray Envelope Corp., 493 F.2d 191

(5th Cir. 1974) 45

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co., 457

F .2d 1377 (4th Cir.), cert. denied,

409 U.S. 982 (1972) 49

Buckner v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.,

339 F. Supp. 1108 (N.D. Ala. 1972),

aff'd per curiam, 476 F.2d 1287 (1973)........ 44, 53

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir.

1971), cert. denied, 406 U.S. 950 (1972) . . . . 60

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Bd. of Educ.,

364 F . 2d 189 (4th Cir. 1969) ................ 57

Duhon v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.,

494 F .2d 817 (5th Cir. 1974) ................ 59

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495

F .2d 398 (5th Cir. 1974), Cert. granted

on other grounds, 43 U.S.L.W. 3515 (1975).... 51, 53, 59

Gamble v. Birmingham Southern Railroad Co.,

No. 74-2105 Slip Opinion (5th Cir.

June 16, 1965)................................ 45, 61

Goldie v. Cox, 130 F.2d 695 (8th Cir. 1942) . . . 58

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) o . 8 , 55, 56

57, 59, 60

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 420 F.2d 1225

(4th Cir. 1970), aff'd in pertinent

part, 401 U.S. 424 (1971) .................... 56

In re Las Colinas, Inc., 426 F.2d 1005

(1st Cir. 1970), cert. denied, 405 U.S. 1067 . . 69

vi

Page

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.,

491 F .2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1974) .............. 48, 60, 61

Local 189 v. United States, 416 F.2d 980

(5th Cir. 1969), cert denied, 397

U.S. 919 (1970) .......................... .. 48

Louis Dreyfus & Co., v. Panama Canal Co.,

298 F.2d 733 (5th Cir. 1962)................ 69, 70

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965). 56

Mid-Continent Petroleum Corp. v. Keen,

157 F .2d 310 (8th Cir. 1946)................ 58

Moody v. Albermarle Paper Co., 474 F.2d 134

(4th Cir. 1974), vac. & rem., 43 U.S.L.W.

4880, 9 EPD 51 10,230 (June 25, 1975)........ 59

Moore v. Bd. of Educ. of Chidester School

Dist. No. 59, 448 F.2d 709 (8th Cir. 1971) . . 57

Morrow v. Crisler, 491 F.2d 1053 (5th Cir.

1975) (en banc) ............................ 53

Morrow v. Crisler, 479 F.2d 960 (5th Cir.

1973), aff1d en banc, 491 F.2d 1053 (1974) . . 60

NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614 (5th Cir. 1974) . . 53

North Carolina Teacher Ass'n. v. Ashboro City

Bd. of Educ., 393 F.2d 734 (4th Cir. 1968) . . 57

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 46, 47

494 F .2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974) .............. 49, 52, 61

Railex Corp. v. Speed Check Co., 457 F.2d

1040 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S.

876 (1972) .............................. 59

Roberts v. Ross, 344 F.2d 747 (3d Cir. 1965) . . 69

Rolfe v. County Bd. of Educ. of Lincoln County

Tenn., 391 F.2d 77 (6th Cir. 1968).......... 57

Rogers v. Int'l Paper Co., 510 F.2d 1340 49

(8th Cir. 1975) ............................ 52, 59, 60

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 475 F.2d

348 (5th Cir. 1972) ........................ 49, 51, 58

Vll

The Severance, 152 F.2d 916 (4th Cir. 1945) . . . . 6.9

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, 419 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1970 (en banc) . 57

Tanker Hygrade No. 24, Inc. v. The Dynamic,

213 F .2d 453 (2d Cir. 1954) .................. 69

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp.,

446 F . 2d 652 (2d Cir. 1971) .................... 48, 49

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp.,

444 F . 2d 652 (2d Cir. 1971) .................... 49

United States v. Duke, 332 F.2d 759 (5th Cir. 1964). 56

United States v. El Paso Natural Gas Co.,

376 U.S. 651 (1964) ............................ 69

United States v. Forness, 125 F.2d 928 (2d Cir.),

cert. denied, 316 U.S. 694 (1942) .............. 69

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474

F.2d 906 (5th Cir. 1973)........................ 39, 60

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co.,

451 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971), cert.

denied, 406 U.S. 906 (1972) .................. 49, 60

United States v. Local 189, 301 F. Supp. 906

(E.D. La.), aff'd 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir.

1969), cert. denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970)........ 48

United States v. Lynd, 349 F.2d 785 (5th Cir. 1965). 56

United States v. Palmer, 356 F.2d 951

(5th Cir. 1966) .......... ...................... 56

United States v. Ramsey, 353 F.2d 650

(5th Cir. 1966) ................................ 56

United States v. State of Mississippi, 339

F .2d 679 (5th Cir. 1964)........................ 56

United States v. United Carpenters' Local 169,

457 F .2d 210 (7th Cir. 1972) .................. 49

United States v. United States Steel Corp.,

5 EPD H 8619 (N.D. Ala. 1973) .................. 51

Page

- viii -

United States v. Ward, 349 F.2d 795 (5th Cir. 1965)

Volkswagon of America v. Jahre, 472 F.2d

557 (5th Cir. 1973) ..............................

Vulcan Society v. Civil Service Commission,

360 F. Supp. 1265 (S.D. N.Y. 1973),

aff'd, 490 F .2d 387 (2d Cir. 1973) ................

Ward v. Apprice, 6 Mod. 264 (1705) ................

Witherspoon v. Mercury Freight Lines,

Inc., 457 F .2d 496 (5th Cir. 1972) ................

Statutes and Other Authorities:

28 U.S .C. § 1291 ..................................

29 U.S.C. §§ 151 et seq.................... ..

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ..................................

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et_ seq. , Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (as amended 1972) . . .

29 C.F.R. § 1607.11 .............................. 54,

9 Wright & Miller, Federal Practice and

Procedure § 2578, at 707 ..........................

118 Cong. Rec. 4492 (1972) ..........................

56

6 8 , 69

58

58

44

1

2

2

passim

Appendix E

70

64

Page

ix -

Note On Abbreviation

The following abbreviations are used in the

brief:

"Stockhara" or "Company" .............. .. . . Stockham Valves and

Fittings Company

"Steelworkers" ....................... .. . . United Steelworkers

of America

"Local 3036" ......................... .. .. Local 3036, Steel-

workers

"Union" .............................. .. .. Local 3036 and the Steelworkers

"PX" ................................. . .. Plaintiffs' exhibit

"DX" ................................. . .. Stockham's exhibit

"UX" ................................. . .. Union's exhibit

H i p I t . . . Transcript of trial

testimony

"D" .................................. . .. Deposition

"Op." ................................ ... March 19, 1975 opinion

of the district court

x

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

1. Whether the district court erred in concluding that

defendants did not maintain an unlawful departmental seniority

system?

2. Whether the district court erred in concluding that

Stockham did not unlawfully discrimin^je...in the assignment

or selection of employees to hourly paid jobs, or in the

assignment, selection or recruitment of employees for training

programs, or salaried positions?

3. Whether the district court erred in concluding that

the testing and educational programs were lawful?

4. What affirmative relief is necessary and appropriate

to remedy the discriminatory effects of the unlawful practices

of the defendants on the plaintiffs and the class of black

employees whom they represent?

xx

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

5 ^

A

This case of racial discrimination in employment comes here

on appeal from a final judgment of the United States District

Court for the Northern District of Alabama entered or^kMarch 19,

1975. The appeal presents important and often litigated questions

concerning the determination of racial discrimination and the

appropriate remedy for that discrimination. This Court has

jurisdiction of the appeal under 28 U.S.C. § 1291.

On October 5, 1966,'-tihe named plaintiffs, Patrick James,

Howard Harville and Louis wUnston, black men who were employed

at Stockham at that time, filed charges of discrimination with

■the EEOC. (3417a-19a; 107a) A broad spectrum of allegations of

discrimination v/ere levelled against Stockham, including, inter

alia, maintaining segregated facilities, denying blacks job

advancement, training and promotional opportunities, staffing

jobs on a segregated basis, excluding blacks from clerical and

supervisory jobs, and using discriminatory testing and educa-

J j . .tional requirements. (Id..) The EEOC rendered a decision

finding that there was "reasonable cause" to Relieve that

Stockham engaged in discriminatory practices ahd issued the

plaintiffs a notice of right to sue in February, ^1970. (4133a-37a)

Plaintiffs filed this suit as a class action on behalf of

similarly situated black workers under Title VII of the Civil

1/ On June 8 , 1970, Patrick James filed an amended charge of

discrimination with the EEOC which added Local 3036 and the

Steelworkers as respondents. (3420a)

1

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et s«[.( 42 U.S.C. § 1981

and 29 U.S.C. §§ 151 et seq. ("the duty of fair representation"),

on Marcl\ 16, 1970 .J The complaint alleges a pervasive and total

pattern orraclal discrimination ranging from segregated

facilities to the exclusion of blacks from.jobs, training and

supervisory positions. The defendants generally denied these

allegations.

On September 10, 19 70«Sthe district court referred the ^ ̂ ̂

matter to'the EEOC for conciliation. The matter remained

in conciliation until June 1973 when the district court granted

plaintiffs 1 motion to set aside the order staying the matter

for further EEOC proceedings. After the matter was reinstated-^

on the active docket, full discovery was expeditiously under

taken. Pa pre-trial conference was scheduled, and trial was held

»■ ■ a i— in y

for 15 days from February 4, 1974,through February 22, 1974.

The court requested all parties to submit post-trial briefs,

proposed findings of fact and conclusions of law, and requested

oral argument. On March 19, 1975,the district court rendered

— •— .................................— -------------------- ................ ....................................

'final judgment. The district court found that Stockham

maintained segregated facilities, including cafeteria, bath-

_2 /)oms and locker facility, but engaged in no other form of /

2 / The district court found that the Conciliation Agreement

entered into between the EEOC and Stockham two weeks before trial

effectively resolved the issue of segregated facilities and

accordingly entered no injunction barring the Company from main

taining segregated facilities. However, the district court

awarded the plaintiffs counsel fees for their work Which con

tributed to the integration of Stockham's facilities because

the lawsuit had a "therapeutic role" in bringing about the con

ciliation agreement. (260a)

2

x Jdiscrimination. Specifically, the court found that Stockham

has "at no time" made job assignments on the basis of race, and

that its promotional, transfer, seniority, testing and educa

tional requirements and selection procedures for supervisory,

.4./apprentice and clerical positions were non-discriminatory.

Plaintiffs filed their timely notice of appeal on April 16, 1975,

Plaintiffs moved this Court to correct or modify the record

on appeal to include the post-trial briefs and proposed findings

of fact and conclusions of law submitted by the parties after

the district court had refused to include these documents in

the record on appeal. Judge Simpson issued an Order granting

the plaintiffs' motion on May 28, 1975. (273a-74a)

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A. An Overview of the Parties and the Operations

The named plaintiffs are black workers who have each worked

-5/ ,many years at Stockham. ' Patrick James,)a veteran of World

3/ The Opinion and Judgment of the Court comprise 160 pages.

For the convenience of the Court the plaintiffs have reduced the

Opinion to its outline form, see Appendix A. The plaintiffs have

also included in Appendix A a compilation of the number of find

ings of fact and conclusions of law which the district court

"adopted" from those proposed by Stockham.

4/ Apart from an award of counsel fees to plaintiffs for the

"therapeutic role" the lawsuit played in integrating the facilities

at Stockham, the court granted judgment for the defendants. How

ever, the court with no explanation ordered that the "existing"

age and educational requirements may not be imposed as "uncondi

tional" requirements for entrance into the apprenticeship program.

(259a-60a) and

5/ The plaintiffs brought this case on their own behalf/on behalf

of similarly situated black workers. The district court found that

this is an appropriate class action and that the class "consists of

all black hourly production and maintenance employees currently

employed by Stockham and all black .persons who bave been so employed

at Stockham from July 2 , 1965, to the date of trial." (239a)

3

War II, a high school graduate and a graduate of Booker T.

Washington Business College, has been employed at Stockham since

1950.j Like other blacks Mr. James was relegated to a laborer's

yjob upon hire; and twenty-four years later he is still working

as a laborer/. (632a, 638a-39a, 641a, 643a, PX 15, p. 6 8) ̂ lowcrrc]

I ffarville. was employed ^n"‘I946 and worked until 1970 on the all

black job of arbor molder in the Grey Iron Foundry. (851a)

^ Louis Winston was hired into a laborer's job in the all-black

galvanizing department in 1964. (1373a) In 1965, Winston

was transferred to the electrical department as a laborer, the

only job which blacks were assigned in that department. In

1971 he became one of the first blacks to be enrolled in the

apprentice program. (See infra at 32 )

The defendant Stockham Valves & Fittings Company is incor

porated under the laws of Alabama and is engaged in the manu

facture of cast iron and malleable fittings, and bronze, iron,

steel ar.d butterfly valves. (110a ) Its various product lines

are manufactured at one facility in Birmingham. The plant is

ivided into twenty-two seniority departments. Some departments

2_/

produce the basic materials and molds for Stockham's products

6 / The job requires that workers spend a considerable portion

of their working day on their knees on the hot molding floor.

(857a-58a; 910a-lla) Mr. Harville was forced to retire on medical

disability; at present Mr. Harville receives a medical disability

pension from Stockham of $40.00 per month. (900a )

7 / Except for steel the Company manufactures raw materials

into finished products. (.S-.ee .generally 4125a-26a)

sitr 4

j,y.i -

(e.g. Grey Iron Foundry, Bronze Foundry, Malleable Foundry),

other departments assemble, finish and machine products (e.g.

Tapping Room and Valve Machining and Assembly), and another

group of departments perform maintenance functions (e.g.

Electrical Shop, Machine Shop, Valve Tool Room, Construction).

(116a-20a)

The workforce at Stockham's Birmingham facility has been

_ 8_ /

approximately 56% black from 1966 through 1973. (2946a-47a

3335a-42a)

Black White Total % Black

1966 1 , 0 0 2 760 1,762 56.9

1969 1,055 780 1,835 57.5

1973 1,298 995 2,293 56.5

It is clear that the percentage of blacks in the workforce

exceeded the percentage of blacks in the Birmingham area.

Likewise it is clear that the Company hired blacks for cer

tain positions which are, not surprisingly, the hard, dirty,

menial production jobs; whereas the Company hired, recruited

and trained whites for the skilled, maintenance, clerical and

8 / The district court found that "[h]istorically, approx

imately two-thirds of Stockham's employees have been black."

(101a, 137a) The entire workforce has been considerably

less tnan 2/s biacx although the production ana maintenance

workers are approximately 2/3 black, see fn. 9 , infra.

5

-2/supervisory positions*

The defendant Unions, the United Steelworkers of America

("Steelworkers") and Local 3036, Steelworkers,are the bargaining

unit representatives for the production and maintenance hourly

employees at Stockham's Birmingham facility.

B . An Overview of the Discriminatory Practices

The practices of racial discrimination at Stockham have

to be viewed within the context of entrenched and presistent

segregation of facilities and opportunities at Stockham. At

one time the Company segregated just about every activity

the the the

imaginable, from/entrance gates and/pay windows to/bathroom

the

and/locker-room. (see infra at 8-10) Of course, jobs were

also staffed on a segregated basis as is forthrightly testified

to by E. Reeves Simms, who was the personnel manager from 1950-

1970 :

9 / The racial stratification of job opportunities is generally

revealed by the Company's own classifications on its EEO-1 forms

for 1966, 1969 and 1973. (2946a-47a; 3335a-42a)

1966 1969 1973

Occupations ' B W B W B W

Officials & Managers 1 1 0 1 1 132 6 168

Professionals 1 22 2 29 4 51

Technicians 1 2 1 1 2 1 5 31

Sales Workers 0 1 0 1 0 1 1

Office & Clerical 5 193 8 205 18 189

Craftsmen (skilled)

Operations (semi-

0 162 0 158 4 185

skilled) 854 260 890 213 926 293

Laborers 115 0 218 0 291 38

Service Workers 25 0 25 2 1 44 29

Total 1 , 0 0 2 760 1,055 780 1,298 995

6

10/

"Q. . . . Now, Mr. Sims, this general rule

which we have discussed about their being

black jobs and white jobs at the Company,

is that written down anywhere?

A.

Q.

A.

Q.

A.

No, sir.

How was it enforced, or how was it put

into practice?

It was in practice when I came to Stockham

and —

Would you just say it was a custom?

Yes, sir, custom." (footnote added) (331a)

11/

The segregation of facilities and the denial of equal job

opportunity was maintained after 1965, both overtly and by

employment practices which continued the effects of the past

12/

racial allocation of jobs. First, the Company maintains a

departmental seniority system which restricts transfer. Second,

there was no posting of job openings. Third, the foremen in

each department have substantial discretion to fill jobs,and this

discretion has been used to continue the racial allocation of

jobs within departments. Fourth, the Company excluded blacks

from its formal and informal training programs for skilled and

10/ Mr. Sims had testified earlier that as a general rule (he

could recall no exception) blacks were assigned to one set of

jobs and whites were assigned to another set until 1965.

(305a-06a)

11/ see also Appendix "B" to this brief which includes testimony

by company managers and supervisors concerning the racial alloca

tion of jobs. Despite this direct testimony and undisputed

statistical evidence, the district court found that Stockham "at

no time" assigned employees to jobs by race. ( 140a )

12/ See infra at E-J.

7

supervisory positions until 1970-71, and thereafter admitted

only a token number of blacks. Fifth, the Company in August

1965 instituted the Wonderlic Test for transfer, promotion and

hire without any attempt to validate the test and without

12/requiring the incumbent employees to take the test. Sixth,

the Company instituted age and education requirements for

admittance to the apprenticeship program which have the effect

of excluding or limiting black enrollment. Seventh, the Com

pany has continued to limit black promotion from the hourly

workforce to salaried positions: supervisory, clerical and

technical. Eighth, the Company, while regularly recruiting

for its management program at the predominantly white colleges

in the area, has never recruited at the predominantly black

colleges.

Although these practices will be analyzed separately, they

interrelate and above all, when these practices are taken to

gether with the history of total segregation at Stockham, they

make it perfectly clear to both the white supervisory staff

and the black workers that there was a specific "place" for

blacks at Stockham.

C . Segregated Facilities and Programs

In 1965 Stockham maintained a system of total segregation

1 3 / The Company halted the use of the Wonderlic Test after the

decision in Griggs v. Duke Power Company, 401 U.S. 424 (1971).

In 1973 the Company hired a consultant to develop another test

ing program for Stockham. Although tests were developed and

were being given to employees, they were not as of the date of

trial being used to select employees for jobs, see infra at

39-40.

8

employee identifica-14/which even extended to entrance gates,

15/tion numbers and pay windows. All the toilet facilities

built prior to 1965 were divided into "colored" and "white"

15/ . ±2/ areas. (3449a-50a; 4123a) similarly, the cafeteria

18/

and the bathhouse for the hourly employees

1 4/ Partitions divided two entrance gates to the Company; blacks

entered on one side and whites on the other side. (284a) in

1965, plaintiff Harville was physically prevented from entering

a gate marked "white" by a plant guard. When Harville reported

this event to his foreman, a Mr. Snyder, he was told that he

did not have any business going through that gate. (859a-860a)

The particularly racist nature of partitioned entrance gates

struck the Stockham Board of Directors as being contrary to Title

VII and these partitions were removed by order of the Board in

mid-1965. Peculiarly, the Board did not have the same reaction

to the partitions segregating the bathrooms, the cafeteria and

the bathhouse. (3455a-57a)

15/ The Company assigned employees identification numbers by-

race until 1969: all white hourly employees had numbers beginning

with 3000 and continuing upwards; all black hourly employees had

numbers which ranged from 300 to 2999. (4124a-

25a) During the period in which black and white employees had

separate identification numbers, the Company paid employees in

cash which was disbursed through pay windows. There were separate

pay windows for employees with badge numbers 300-2999, i.e.

black employees, and employees with badge numbers 3000 and up,

i.e. white employees. (4123a-4124a)

16/ There were six bathroom facilities with adjoining separate

rooms or with one room which was partitioned. See 10-11, infra.

17/ The cafeteria contained two serving lines, one on each side

of the partition. (3436a-37a; 4122a)

18/ The bathhouse was divided by a partition running east-west;

each side of the partition contained locker, shower and toilet

facilities. The lockers on the north side were assigned solely

to black employees and on the south side solely to white

employees. (4123a)

9

11/

were partitioned into segregated areas.

These segregated facilities lasted until the eve of trial.

The persistence by which the Company clung to segregation is

amply illustrated by their practice of removing the partition

in the cafeteria each year (including 1973) for a labor day

picnic and then reinstalling the partition after the picnic.

(466a, T. 1043-44)

On January 21, 1974, Stockham entered into a "conciliation

agreement" with the EEOC concerning certain segregated facilities.

' (1420a-142la; 3902a-3908a) Stockham agreed to remove the partitions i.

the cafeteria, bathhouse and in five toilets, and to reassign

the lockers in the bathhouse. (3902a-3908a)

The conciliation agreement also affected the YMCA program

21/

at Stockham. The program was established in 1918 solely

2 0/

19/ Although the signs demarcating "white" and "colored" areas

were removed in 1965, the partitions remained and the custom Oi.

segregation continued. A Company manager, Mr. Sims, testitie

that an overwhelming majority of blacks_continued to eat on one

side of the cafeteria and the overwhelming majority of whites

continued to eat on the other side. (282a-283a; 1101a-10l2a;

4123a)

20/ The agreement was rather peculiar in timing and in the

procedure by which it was entered. The conciliation agreement

developed from charges filed in 1970 by a Mr. Darden and a

Mr. Williams, who complained that they were unlawfully dis (1419a_

charged and that Stockham maintained segregated facilities. \

' 1420a, 1435a-1436a) The agreement was only between EEOC and

Stockham; the charging parties were not even informed of the

Agreement, nor did they participate in the negotiations.

(1435a) Neither the plaintiffs nor their attorneys were_

informed about the Darden-Williams charges or the negotiations

concerning the removal of the segregated facilities. (

21/ The YMCA program sponsors activities such as athletics

bible classes for the employees. (3430a-3432a, 3435a,

1471a-1472a) These activities were once totally segregated.

and

(Id.)

10

for employees and derives its support from Stockham. (207a)

Until December 1973 there were two segregated Boards which22/

made suggestions concerning the activities of the YMCA. In the con

ciliation Agreement the Company agreed to create one integrated

Board. (3902-3908a) However, the conciliation agreement

failed to terminate one set of segregated bathrooms - a women's

23/

bathroom in the Dispensary.

The black employees at Stockham had repeatedly attempted

to end these degrading practices of segregation. The members

2A/of the Union's Civil Rights Committee ("CRC") have repeatedly

22/ The Company actually integrated the Boards a month before

they entered into the Conciliation Agreement. (4].22a)

The present Board consists of eighteen employees, nine

white and nine black. (Id..)

23/ The court found that there were no "racially discrimina

tory practices" concerning this women's bathroom. (208a)

This is contrary to the evidence in the record.

Briefly, the undisputed facts are as follows: (1) Stockham

maintains a dispensary at the plant which provides medical and

dental care for employees; (2 ) there are seven women who work

in the dispensary as receptionists, dental hyqenists or nurses

(297a-298a; 2853a-2858a); (3 ) there are two women's bathrooms located

side-by-sxde for these seven individuals (296a-297a); (4) there

are two black women and five white women who work in tne dis

pensary (2853a-2858a); (5) the two black women, as testified to

by a black nurse, have lockers in and use one bathroom while

the white women have lockers in and use the other bathroom.

(2853a-2 958a)

24/ In 1965 the Steelworkers ordered Local 3036 to establish a

Civil Rights Committee. (PX 6 8 , D. Robbins 6 8) Through an

informal understanding officials of the Company agreed to meet

with the CRC of Local 3036. In 1970, a joint Company and Union

Civil Rights Committee was established under the collective

bargaining agreement. (3132a; I329a-l330a)

Any action proposed by the union members of the CRC had to be

approved by the Company officials before any corrective action

would be taken.

11

requested that the partitions which segregated the cafeteria,

bathhouse and toilets be removed. (3454a; PX 6 8 ,

D. Robbins 52-53) Furthermore, the plaintiffs listed the

segregated facilities as discriminatory practices in their EEOC

charge. The EEOC found "reasonable cause" in a decision issued

in 1968 that Stockham's facilities were segregated. (4l33a-4l34a)

Yet, the Company refused to integrate its facilities until 1974.

D . The Job Assignment and the Departmental

Seniority System

1. The Job and Pay Structure

Stockham divides its hourly production and maintenance jobs

into twelve job classes which run from job class ("JC") 2 through

13. (PX 24, Appendix C) The pay rate for each job is based on

25/

the job class in which it is located, although merit raises

26/

and incentive earnings may result in differentiation of

earnings within job classes.

While non-incentive workers are paid a straight hourly

rate there is a range of pay for each job class. For example,

as of June 10, 1973, for JC 2 the pay range was $2.85 to $3.30

25/ The job class for each job is established by developing job

descriptions in accordance with a system set forth in a "Job

Evaluation Manual." Prime elements of the job, e.g. "responsi

bility," "manual skill," etc., are each assigned numerical values;

the total point value of the job determines its job class, and

accordingly its pay rate. (4125a-4l26a)

26/ A disproportionate number of the employees on incentive are

black. Approximately 70% of the black employees are on an incen

tive program, as compared to 31.7% of white employees (125a; 3852a-

53a) It should be noted that no job which is classified m

the top four job classes, JC 10-13, is on an incentive program.

12

per hour, while the range for JC 13 was $3.66 to $4.47 per

22/hour. ( 3l90a-3198a) When he is first assigned to a

job an employee begins at the low-end of the scale, e.g. $2.85

per hour for JC 2. Within each job class there are specific

gradations or steps of pay; to receive a pay raise within a

job class an employee must obtain a predetermined score under

a "merit rating system" and be approved for the raise by his

2-2/supervisor. ( 126a-12 7a) All employees receive merit ratings

from their foremen every six months, even though incentive

29/

, workers are not eligible for merit raises.

There are two types of incentive programs: direct and

30/

indirect. (See 123a-25a) An incentive worker is guaranteed

27/ The pay range for the job classes from 1965-1973 are in the

record, PX 35.

28/ Each employee is rated twice a year; if he has a high enough

rating he is awarded a merit raise, at least once a year even

though his supervisor does not recommend him for a raise.

(PX 85, D. Bagwell 22; 126a)

29/ The foreman makes the rating by completing a form which lists

several general work characteristics. As an example, the foreman

is asked to rate an employee from "poor" to "exceptional" on

"quantity of work." (137a); 3728a is an example of a ratmq

form). An employee in the Personnel Department then quantifies

the completed form according to a chart which assigns points to

each category. (128a ) As might be expected, the overwhelm

ingly white supervisory staff rated white employees substantially

higher than black employees. See infra at 49 . The defendant's

expert testified that in 1973 blacks averaged 71.3 while whites

averaged 79.5 on merit ratings. (3971a; It should be noted

that a merit rating becomes part of a worker's personnel file

and is a factor considered in promotion and training selection.

(PX 85, D. Bagwell 25; 3353a-3355a)

30/ The indirect incentive worker, unlike the direct incentive

worker, does not receive incentive pay on the basis of "his pro

duction." (1460a) Rather, his pay is calculated on the basis

of the production of direct-incentive workers for whom he pro

vides a service. (1460a-1462a)

13

a On the2l/

certain hourly wage depending on his job's JC.

basis of the incentive program established at Stockham, a

direct incentive worker's pay averages approximately 25% above

his base incentive rate, ( 124a ) ; indirect incentive workers

average something less than that amount. (1481a-82a)

2. Departmental Seniority Structure

At least since 1240 Stockham has maintained a departmental

seniority system. ( 130a) The jobs in the plant are divided

31/into twenty-two seniority departments which have determinative

12/promotion and regression consequences for the bargaining

unit employees. The basic seniority provision in the collective

bargaining agreement has remained unchanged in substance and

was in effect at the time of trial. Other factors being equal,

departmental seniority determines promotions, lay-offs and

recalls. Accordingly, a worker who transfers departments is

now, and always has been, a new employee for purposes of promotion

3A/and regression in the new department.

3 ]/ For example, the incentive rate for JC 2 is $2.85 per hour,

while it is $3.29 per hour for JC 9. ( 3l90a-3l98a) _ An

indirect incentive worker is guaranteed a slightly higher rate

than a direct incentive worker in the same job class. ( 124a)

32/ The seniority departments are set out by stipulation of

the parties, 3725a-3727a.

3 3 / As used in this brief, "regression" is a short form for the

movement of an employee(s) during a reduction-in-force and lay

off? in other words, the term refers to the process by which

employees are laid-off from a job, department, and the plant.

14/ lee. 1964 Agreement, 3093a-3094a; 1967 Agreement,

3119a? 1970 Agreement, 3145a? 1973 Agreement,

317 3a-3l74a.

14

Prior to June 10, 1970, if a worker transferred departments,

he immediately lost all seniority in his old department.

(3096a; 3121a) Consequently, if there was a reduction-

in-force he would be among the first employees laid-off.

In 1970, this harsh requirement was slightly modified. An

employee had eighteen months after transfer to decide if he

wanted to return to his old department. If within that time he

decided to return he would be permitted to re-enter his old

department within twenty-four months of his transfer with his

35/

accumulated seniority. (3l48a-3l49a)

A further modification was instituted by the 1973 collec

tive bargaining agreement. If after eighteen months an employee

elected to remain in the department to which he transferred,

then he was allowed to retain his seniority in his old department

solely for lay-offs, but only until he had been in the new

department as long as he had been in the old department. If

during this period he was laid-off, 'he was permitted to return

Jlfi/to his old department with his accumulated seniority.

(3177a-3l78a)

Under both the 1970 and 1973 Agreements, the basic features

of Stockham's seniority system remained unchanged: (1) an

employee who transfers departments forfeits his accumulated

35/ If he elected to stay in the new department he lost his

accumulated seniority in his old department.

36/ The Union from 1967 through 1973 had been negotiating for

major revisions in the departmental seniority system, see

infra at 61, n. 157.

15

seniority at some point; (2 ) an employee who transfers depart

ments is a new employee for all promotion and regression pur

poses in his new department; and (3) a departmental employee

has the first opportunity to promote to all vacancies within

his department.

E . The Racial Allocation of Jobs at Stockham

The evidence is uncontroverted that at least until 1965

Stockham assigned jobs on a racial basis. The plant manager,

personnel manager and a superintendent testified that the racial

32/

allocation of jobs was the "general rule," that they could

not recall a single exception prior to 1965 to the general rule

3 ft/of segregated job staffing, and that it was a "custom" to

33/staff jobs on a segregated basis at Stockham. In addition,

the statistical evidence clearly confirms the segregated

practices. The plaintiffs introduced an exhibit, PX 1, which

listed the jobs in which "current employees," i.e. those employed

as of September 1973, were working as of June 1965, June 1968,

40/ As of June, 1965,

November 1970 and June 1973. /in the several hundred hourly-

3 7 / Sims (Personnel Manager), 305a-306a, 3568a-69a ,

Carlisle (Superintendent) 3607a.

38/ Burns (Plant Manager) 3679a-3680a; Sims, 305a-306a.

3 9 / Sims, 331a. This testimony as to segregated staffing of

jobs, as well as relevant colloquoy between Counsel and the

district court is set out in Appendix "B."

4 0 / px 1 was compiled from forms ("McBee forms") in each employee'

personnel file which detail the work history of the employee, in

cluding his race, job, job class level and "payroll" department.

Some payroll departments are identical to seniority unit department

Other seniority unit departments may include more than one payroll

department; however, payroll departments are not divided between

seniority departments. (PX 80 contains a stipulation between the

Company and the Plaintiffs detailing the payroll and seniority

departments.)

paid job categories, there was not one in which both a black

and white were working. (2887a-2936a) Furthermore, a half-dozen

company managers and supervisors testified that jobs within

departments were segregated and that the segregation, in many

41/

cases, continued well after 1965.

Not surprisingly, the segregated staffing of jobs resulted

in blacks generally being placed in the lowest-paying jobs at

Stockham. The following chart lists the job classes whites and

blacks who were working as of September 1973 held in June .1965,

June 1968, November 1970 and June 1973 { 2887a-2888a, see fn. 9 supra)

INCENTIVE WORKERS

42/Job Class June 1965 June 1968 Nov. 1970 June 1973

B W B W B W B W

B9 0 5 0 1 0 1 1 2 22

B8 0 47 2 53 4 60 18 1 1 1

B7 0 4 18 1 23 1 70 9

B6 25 0 34 0 47 0 64 0

B5 134 0 214 1 235 1 279 1 1

B4 2 1 1 72 1 82 0 109 5

B3 89 0 80 0 94 0 102 4

B2 58 0 2 1 1 32 1 157 15

TOTALS 32 7 57 441 58 517 74 801 177

40/ (Continued)

The plaintiffs in preparing pxl placed each worker for

whom they had a McBee form (i.e. every worker employed as of Septembe

1, 1973) in the job that he was working as of four dates, June

1965, June 1968, November 1970 and June 1973. The results are

recorded in PX 1, which lists the jobs by payroll department.

Al/ See e.g. Sims, 325a (Tapping Room); Carter, 911a-9l6a- (Grey

Iron Foundry including the Ductile Foundry); Waddy, 1056a-1057a

(Brass Foundry); Waddy, 1060a-1064a (Brass Core Room); Burt 1672a

(Shipping, Receiving and Dispatching); Vann, Il30a-ll38a (Valve

Machining and Assembly); Pugh, 1227a-1228a, Sims 3l0a-3l5a

(Malleable Foundry); see Robbins, President of Local 3036, I308a-1309

(Valve Tool Room)

42/ "B" indicates an incentive pay rate.

17

NON-INCENTIVE WORKERS

Job Class June 1965 June 1968 Nov. 1970 June 1973

B W B W B W B W

13 0 46 0 55 4 77 1 144

12 0 9 0 7 0 9 3 34

1 1 0 10 0 9 0 14 0 22

10 0 5 0 14 0 14 2 30

9 0 24 2 34 3 42 9 52

8 0 2 1 4 3 6 7 7

7 0 2 1 5 2 1 1 24 24

6 2 9 16 1 1 19 8 27 25

5 103 3 108 1 129 5 143 9

4 8 0 1 1 0 15 1 40 1

3 31 0 43 1 45 0 56 5

2 34 0 59 3 61 2 190 14

TOTALS 178 1 1 0 239 144 281 189 502 36 7

These charts plainly illustrate the allocation of lower-paying

jobs to blacks. First, in 1965 not one of the 502 black workers

who were working as of September 1973 was in a job located in

job class 7 and above, as compared to 154 or 92% of the 167 white

workers who were working in job class 7 and above. Secondly,

the persistent disparity in earnings opportunity continued after

1965 with only slight improvement in the employment position of

blacks (2887a-2936a)

The Average Job Class For Black

And White Incentive Workers

BLACKS WHITES

June 1965 3.94 7.95

June 1968 4.50 7.78

Nov. 1970 4.50 8 . 0 1

June 1973 4.35 7.15

18

The Average Job Class For Black

And White Non-Incentive Workers

BLACKS WHITES

June 1965 4.04 10.74

June 1968 4.02 10.35

June 1970 4.25 10.51

June 1973 3.90 10.23

The plaintiffs corroborated the job class analysis which

resulted from the McBee forms (PX 1) by doing a job class analysis

(and also earnings analyses, see infra at K ) from the payroll

43/

register of the Company dated September 2, 1973 (PX 15). The

continued disparity in earning positions of blacks and whites

is fully demonstrated by the analysis of the September 2, 1973

44/

register, (3815a)

43/ The plaintiffs placed the payroll register for that date,

(PX 15), which contains earnings, seniority and job class data

for each employee on computer tape and ran that information in

order to obtain comparisons in earning and seniority data between

whites and blacks. (See 3765a-3855a) The plaintiffs submitted the

working tapes for these charts to the Company and, after the

Company reviewed the tapes for mechanical errors, reworked the

tapes to correct those errors pointed out by the Company. (1827a)

44/ NON-INCENTIVE WORKERS - 9/02/73

JC 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 1 12 13 Total

#B 12 8 38 47 91 28 22 6 5 2 0 2 2 371

#w 15 4 2 12 23 26 10 53 26 23 31 141 366

INCENTIVE WORKERS — 9/02/73

JC B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B7 B8 B9 Total

#B 209 138 105 263 68 69 18 2 872

#w 17 4 4 9 0 9 106 29 178

For the convenience of the court, PX 94 is attached hereto as

Appendix "C." It should be noted that PX 94 includes 30 individuals

in JC 1; these individuals were listed in the hourly payroll

register as either clerks or apprentices and, as such, are not in

a particular job class. ( 5.82a ) They are not included in the

above tables.

19

non-incentive workers was 3.90 compared to 10.23 for white non

incentive workers; (2 ) the average job class for black incentive

workers was 4.15 compared to 7.19 for white incentive workers;

(3) of the 366 white non-incentive workers> 274 or 75% were in

JC 9 or above, compared to only 11 or 3% of the 371 black non

incentive workers; of the 178 white incentive workers, 135 or

76% were in the two highest incentive job classes, 8 and 9, com-

pared to only 20 or 2% of the 872 black incentive workers.(Appendix C

The jobs to which blacks were assigned were also the most

menial and most unpleasant in terms of heat and dust. Laborer

46/

jobs at Stockham were reserved for blacks. (2946a-2947a;3335a-3342

see also PXl) Blacks filled the laborer positions even in depart

ments (Electrical, Pattern Shop, Valve Tool Room, and Tapping

Tool Room) which were otherwise staffed by white employees,

The disparity is startling: (1) the average job class for black

4.5 / The district court wrongly discounted the evidence of dis

criminatory job class assignment on the basis of its faulty

finding that there was no correlation between job class and

earnings. (143a ) Of course, this argument simply falls by

its own weight when non-incentive workers are compared since

there is a direct and determined relationship between job class

and earning rate for non-incentive workers, see supra at 12-3.

Also, there is a relationship between job class and earnings for

incentive workers as well, although there is greater variability

depending on the particular incentive program and the individual

worker, see supra at 13-4.

Moreover, the racial disparity in job class is mirrored

by a pronounced disparity in actual earning rate and gross

earnings between blacks and whites, see infra at 42-3.

46/ The number of laborers as illustrated by the Company's

EEO 1 Forms (2946a-2947a; 3335a-3342a) is as follows:

1966 1967 1968 1969 1971 1972 1973

White 0 0 0 0 14 30 38

Blacks 115 118 131 12 8 12 3 204 291

20

see infra at 28. A company superintendent readily admitted

that the hottest dirtiest and dustiest departments at Stockham

jjj-g the foundries: Grey Iron/ Malleable and Ductile. (945a — 946a)

Of the 586 hourly employees in these departments as of September

42/ 48/

1 9 7 3 , 551 or 94% were black. (PX 91, 3765a-66a)

F. The Racial Staffing by Department

and by Jobs Within Departments

The racial allocation of jobs at Stockham has resulted in

the racial staffing of departments and in racial staffing within

and white employees in each seniority department as of September

4 7/ Also it is important to note that the jobs in JC 11 13 in the

foundries are "white only" jobs, see infra at 25-7. The district

court found despite the plain evidence in the record that blacKs

were not assigned to hotter, dustier or dirtier jobs them whites.

(1 2 2a)

48/ PX 91 is attached hereto as Appendix "D." On PX 91 the

"seniority departments are numerically designated; the numerical

code is set out in PX 80, 3725a-3727a. Departments listed as 23-26

on the printout, PX 91, refer to hourly -payroll departments

which are not in the bargaining unit, but which were included m

the September 2, 1973 hourly payroll register. These departments

are as follows:

No. on PX 91-97 Hourly Payroll Dept,. PayrolOio^

2 3 Employment (Industrial) 7(3

4 9/ The district court did not make any finding of fact per sj|.

concerning the racial staffing of departments, but simply found,

without further explanation, that blacks work in every department.

(138a) This finding ignores the disproportionate racial depart

ment assignment and the segregation of jobs within departments.

50/ The source for this listing is PX 91, Appendix "D" hereto,

see fn. 48, supra.

The chart below indicates the number of black

50!/1973, and the number of white and black employees who were

24 Plant Protection and Personnel 71

72

7525

26

Services

Medical

Y.M.C.A.

21

still employed as of September 1973, by department as of June 1965.51/

52/ 53/ 1 9 7 3 % b 1 9 6 5 o/cB

No. Seniority Depts. R w R TaT 1 CkfZNo. Seniority Depts. B W 1973 B W 1965

14 Galvanizing 15 0 1 0 0% 9 0 1 0 0%

04 Coreroom & Yard 76 1 99% 24 0 1 0 0%

03 Grey Iron Foundry 2 92 16 95% 92 0 1 0 0%

1 1 Final Inspection 52 4 93% 16 0 1 0 0%

01 Malleable 259 19 93% 88 4 96%

02 Brass Foundry 59 8 8 8% 30 1 97%

17 Shipping 56 8 8 8% 22 0 1 0 0%

12 Foundry Inspection 56 9 8 6% 25 0 1 0 0%

18 Dispatching 2 7 7 79% 4 0 1 0 0%

20 Brass Core Room 1 1 3 79% 1 1 0 1 0 0%

15 Tapping Room 151 45 77% 53 16 77%

13 Valve Finishing Insp. 20 18 53% 8 4 6 7%

2 1 Construction 15 18 45% 5 6 45%

6 Valve Machining & Assembly 70 171 2 9% 76 36 68%

10 Foundry Repairs 12 55 18% 4 10 2 9%

09 Machine Shop 8 50 14% 3 9 2 5%

08 Electrical 2 19 1 0% 1 7 1 2%

05 Pattern Shop 3 37 8% 1 7 1 2%

07 Valve Tool Room 1 17 6% 0 5 -

16 Tapping Tool Room 2 30 6% 0 1 1 -

.5 y The source for this listing is PX 1 , see fn. 40 , supra.

32/ The "No." refers to the numerical designation of the depart

ments on P>r 91-97, see fn. 48, supra.

53/ The departments purchasing (22) and metalurgical (19) have

been left off the chart because they are relatively insignificant

— respectively they have seven (7) and three (3) employees.

(Appendix D)

22

For the purpose of the following discussion the plaintiffs

have classified the departments into three categories: pre-

54/dominantly "black," predominantly "white" and racially integrated.

However, all have one fundamental similarity - there is a tradi

tion of racial assignment of jobs within each department. The

precise employment pattern in each seniority department is not

detailed here; rather, examples of the discriminatory practices

33/

in each category of departments are set forth.

1. The Predominantly Black or

White Departments

The following departments are staffed predominantly with

black employees: Galvanizing, Coreroom and Yard, Grey Iron

Foundry, Final Inspection, Malleable, Brass Foundry, Shipping,

Foundry Inspection, Dispatching and Brass Cove Room. As of

September 1973, there were 903 or 72% of all blacks in the

hourly workforce in these departments, compared to only 75 or

13% of the whites. (Appendix D)

The following departments are predominantly staffed with

white employees : Tapping Tool Room, Valve Tool Room, Pattern

Shop, Electrical Shop, Machine Shop and Foundry Repairs. As of

September 1973, there were 208 or 36% of all whites in the hourly

workforce in these departments as compared to 28 or 2% of all

blacks . (IcU )

54/ The departments classified as predominantly "black1 or "white"

have at least 80% of the predominant race in that department.

55/ A detailed evaluation of the racial staffing of jobs in

departments may be undertaken by a close review of PX 1.

23

since 1965. On the one hand, of the 162 employees who were hired

since 1965 (working as of September 1973) 147 or 90.7% working

in the predominantly white departments are white; on the other

hand, of the 695 employees who were hired since 1965 (working as

of September 1973), 624 or 89.8% working in the predominantly

56/

black departments are black.

The basic pattern of staffing in the predominantly black

departments has been straightforward: the few jobs in the high-

paying job classes are reserved for whites and the remaining

57/jobs are filled by blacks. For example, all the jobs in

The overt racial staffing of these departments has continued

56/ The following charts indicate the departments in which

employees hired since 1965 were working as of September, 1973:

Predominantly

White

Departments

B W

Tapping Tool Room 2 17

Valve Tool Room 0 9

Pattern Shop 2 26

Electrical Shop 1 13

Machine Shop 4 3 7

Foundry Repairs 6 45

Totals 15 147

These figures are derived from PX

the composition of each seniority

race and date of hire. See also

Predominantly

Black

Departments

B W

Galvanizing 8 0

Coreroom and Yard 49 1

G. I. Foundry 218 16

Final Inspection 30 4

Malleable 181 15

Brass Foundry 34 8

Shipping 41 8

Foundry Inspection 37 9

Dispatching 23 7

Brass Core Room 3 3

Totals 624 71

93, (3769a-3819a) which analyzes

department bv, inter alia,

335a-336a, 472a-473a, 911a.

57/ In the few years prior to trial, some whites have begun to

be assigned to jobs in the lower job classes. (316a, 914a-915a

1229a) .

24

the ten predominantly black departments at or above job class

5§/

9 have always been filled by white employees.

Box floor molder (large), has the highest job class (12)

in the G. I. Foundry. At all times since 1951 at least 5-6

59/

employees have held this position, but never a black. (906a-

90'fe) At least six white employees who were hired since 1965 have

become box floor molders or were placed in training programs to

£lQ/become box floor molders (large) . ('3732a-3749a, 925a-928a

The job of craneman, JC 12, in the Grey Iron and Malleable

£1 /Foundries has always been filled by white employees. (922a,

58/ The jobs in JC 9 and above in these departments are as fol

lows : box floor molder (large), JC 12, G. I. Foundry; Craneman,

JC 11, G. I. Foundry and Malleable Foundry; ductile iron melter,

JC 12, G. I. Foundry; oven operator, JC. 13, Malleable Foundry.

59/ On the last day of trial, Stockham announced that a black

employee, Willie Lee Richardson, would be placed on the apprentice

ship program for box floor molder (large). (2674a-2676a) Mr.

Richardson had been employed by Stockham for over nine years,

during which time he only missed 8 days of work. (2882a)

60/ Mr. Wells, who does not have a high school education, was

hired as a craneman learner on September 28, 1965, and sub

sequently became a box floor molder on September 15, 1969. (3732-49a)

Mr. Earnest Alverson, Jr., who does not have a high school educa

tion, was hired as an apprentice molder on October 11, 1965, and

subsequently became a craneman learner, April 27, 1966, and then

a craneman, April 19, 1971. (Id.) Mr. Carlisle was hired at

age nineteen on August 23, 1971, and on June 26, 1972, became an

apprentice molder. (Id.) Mr. Kilpatrick v/as hired on October

28, 1966, as a box floor molder learner, and on May 4, 1970,

became a box floor molder. (jtd.) Mr. Russell was hired at the

age of twenty-one on July 28, 1969, as an apprentice molder, and

on August 27, 1973, became a box floor molder. Mr. Naylor was

hired at the age of nineteen and he became on July 29, 1968 an

apprentice millwright, on June 3, 1970, a box floor molder learner,

and on September 18, 1972, a crane operator. (Id.)

61/ A few weeks prior to trial the company began to train a black

as a crane operator. ( 92 3a)

25

924a, 1227a-28a) It is the normal practice for the Company to

train its crane operators by placing them in the crane with an

experienced operator. (921a-922a, 1567a-1568a) At least seven

white employees who were hired since 1965 have received some train

ing as crane operators in the Grey Iron Foundry or the Malleable

62/

Foundry. (924a-928a, 1574-1575a) Furthermore, there were black

employees who not only had greater seniority than the whites who

were trained as craneman, but blacks also were working in jobs

which provided on-the-job training and experience for operating a

crane. (1559a-1566a) Nevertheless, the Company skipped over these

blacks arid trained whites for the job of craneman.

The ductile iron melter, a JC12 position, is the only

63/ " M /

position in which a white has been placed in the Ductile Foundry.

Oven operator, the only JC 13 position in the Malleable

Foundry, has never been worked by a black employee. (1228a, 3198a)

However, a white employee hired in April 1967 has worked and

been classified as an oven operator. (3750a-52a; 1229a)

62/ Mr. McConnell was hired into the G.I. Foundry on October 7,

1971, and became a crane operator on August 28, 1972. (3758a-63a)

Mr. Parsons was hired into the G.I. Foundry on March 24, 1971, and

became a crane operator on August 30, 1971. (Id_. ) Mr. Hayes, who

does not have a high school education, was hired into the G.I.

Foundry on January 18, 1972, and became a crane operator on June 10,

1973. (Id.*) Mr. Mowery was hired on March 12, 1968, and on March 12,

1973, he became a crane operator in the Malleable Foundry.

(3750a-53; see 1239a)

63/ There is one white employee who works part-time on other jobs

in the Ductile Foundry. (914a-915a) Moreover, when the Ductile

Foundry, which is located in the G.I. Foundry seniority unit began

operation around 1969, the Company placed a white employee from

outside the G.I. Foundry in the job ahead of all the black workers

in that department. (915a-916a)

64/ The first black, a Mr. Hill, who was hired in 1961, was

placed on the job on January 17, 1972. (3755a—3757a) Frank Sorrow,

a white employee who was hired on August 6 , 1973, and who did not nave a high school diploma, became an iron melter in September

1973. (3764a, 1591a) -26-

Of course, all these white employees who were hired since

1965 and who were promoted and/or trained for these jobs were

considerably junior in seniority to many black employees in the

£5/Grey Iron and Malleable Foundries.

The basic pattern of segregated staffing in the predominantly

white departments is as obvious as in the predominantly black

departments. In these six departments blacks have historically

been relegated to laborer, serviceman, clean-up or oiler jobs^

(JC 2-4) , while whites have entered the departments as learners

or apprentices and have progressed to job class 10-13 jobs.

(321a-322a; PX 1-2887a-2936a; PX 93-3769a-3814a)

Plaintiff Winston's employment history is a good example

of the pattern of discrimination in these departments. On

January 1, 1965, Winston was transferred to the Electrical Shoo

67/

as a laborer, JC 2. Winston has continually received excellent

68/

personnel ratings. ^1275a—1276a) In fact Winston's performance

65/ In the G. I. Foundry there were 107 blacks who were hired

to 1966 and who were working as of September 1973, while

in the Malleable Foundry there were 89 such blacks. 3769a 3814a)

-66/ These jobs are not on any incentive program. (PX 1)

Szj/ At that time, the Electrical Shop contained a laborer's

position, an apprentice position and jobs in JC 10-13. (PX 1)

£&/ In late 1965 his first foreman, Mr. Warner, wrote the

following in his file (1384a)

"Louis has been doing a good job. He

helps out whenever he is needed. He

gets along well with the other men. He

needs little supervision. He's always

on the job, has a good attitude and

carries out instructions."

27

was so exceptional that his supervisor, after Winston made the

request (1388a), recommended that his job grade be changed

69/

from JC 2 to JC 3. Yet, despite Winston's acknowledged ex

cellent work record, the Company brought white employees into

the Electrical Shop who had less seniority than Winston and

trained them to become electricians. (I395a-1396a) it was not

until October 1971 that Winston was selected for the apprentice-

70/

ship program for electricians. ( 2944a-2945a)

The employment history in the Valve Tool Room is similar to

that of the Electrical Shop. The job of serviceman, JC 2, has

always been filled by a black, (.1306a-l308a) whereas the other

jobs in the Valve Tool Room, which range from JC 9-13, and

J Vapprentice, remained all-white until April 1971. (1254a,

1309a) The Company has trained 3 or 4 whites as machinists

through the on-the-job training program in the department since

fie/ Winston's foreman, Mr. McDermott wrote on Winston's personnel

report that:

"It's my opinion this man should be re

classified from Job Class 2 to Job Class 3.

This man assists in, one, charging motors

throughout the plant; two, installation of

jobs such as pulling wire in conduit and

overhead; three, waters batteries and checks

conditions of same; four, marks and stops the

spare motors in the shop; five, assembly of

motors in the shop." (i396a)

70/ The Company never selected a black for an apprentice program

until April 1971, see infra at 31.

2 V The only black who has worked in the Valve Tool Room in a

job other than serviceman is Francis Smith who in 1971 became

an apprentice machinist. (1254a,1309a) in April 1971 the

machinist learner position, JC 9, paid $2.91 per hour, whereas

Francis Smith, the black employee who was placed in the apprentice

program, started April 1971 at $2.80 per hour. (PX 35; 1259a-1262a)

28

1965. (1309a-14a)

2. The "Racially Integrated" Departments

22/The integrated departments reflect the traditional pattern

of "vertical segregation." Mr. Sims testified to this traditional

segregation when, referring specifically to the Tapping Room,

he said:

"Q. But, in fact, blacks did not fill the

traditionally white jobs prior to '65,

is that true?

A. True.

Q . And that was irrespective of the depart

mental seniority of the black employee,

isn't that true?

A. Yes, Sir." (328a, see also 324a-325a)

The white employees in these departments generally are

allocated the jobs with greater earning potential, i.e., in the

73/

higher job classes. This is amply illustrated by the largest

72 / The racieilly integrated departments, where at least 2 5% of

each race is in each department, are the following: Valve

Machining & Assembly, Valve Finishing Inspection, Tapping Room

and Construction.

■jjJ The following chart illustrates the average hourly earning

rat® of black and white employees in those departments and their

respective average seniority: (PX 91 - Appendix D)Average Average

Hourly Rate Senior Year

Department B W B W B W

Valve Machining & Assembly 70 171 3.76 4.25 1964.06 1965.45

Valve Finishing Inspection 20 18 3.69 3.57 1963.45 1966.83

Tapping Room

Construction

151 45 3.79 4.05 1964.49 1965.04

15 18 3.54 4.08 1962.00 1966.5C

Except for the Valve Finishing Inspection (where the black average

earnings are slightly higher than those of whites and where whites

average considerably less seniority than blacks), whites earn sub

stantially more and have less seniority than blacks. Whites earn

$ .4 9 more per hour in Valve Machining and Assembly, • 2.6 more per

hour in the Tapping Room, and $.54 more per hour in Construction.

- 29

1A/of these departments, Valve Machining and Assembly. Generally,

25/the higher-paying maching operations are staffed by whites,

25./

while the lower-rated jobs in assembly are staffed by blacks.

Similarly, the jobs in the construction department are allocated

in a manner which places the whites in the best jobs for both

77/

earnings and training.

74/ The department includes machining and assembly operations

for brass, iron, butterfly, steel, and wedgeplug valves. (118a)

75/ For example, brass machine includes a service mechanic,

JC 13, which has always been filled by a white employee (1130a, 2887a

2936a), an automatic screw machine ooerator who has always been

a white employee (1131a, 2887a-2936a,PX3) and approximately 30-35

machine operators in JC 8 , an incentive job. A few blacks, three

or four, now hold positions on this formerly white-only job.

(Il3la-ll32a; 2887a-2936a; PX 1, 5) All of the servicemen and

laborers, JC 3, are black. (Il32a-1133a)

76/ All of the jobs in brass Valve Assembly except for repair

man are JC 5 or below. (1127a-1128a) Until at least Fall 1973,

all these jobs except repairmen have been filled by blacks.

(1127a-1128a, 3769a-3814a)

77/ All of the five or six laborers in the department are black,

(1645a) while all 9 employees in JC 9 and above are white (PX 94-

Appendix C) Moreover, there are three employees in an apprentice

program and five in learner positions, of wnom only one, a

learner, is black. (1643a-1644a)

- 30 -

«

G . Training Programs for Hourly-Paid Jobs:

Apprentice and On-The-Job

The apprentice and on-the-job training programs are im

portant to Stockham, since it, like most companies, is re-

78/

quired to train employees for skilled jobs. In keeping with

the policy of segregating job opportunity, the Company ex

cluded blacks from the apprenticeship program until April 1971,

23/and then enrolled only a token number of blacks. As the

following chart indicates, only 6 out of the 1 0 1 of the em

ployees selected by the Company for the apprentice program since

July 2, 1965 are black (2944a-2945a):

78/ The district court, based on testimony by Mr. Hammock,

manager of the Alabama State Employment Service in

Birmingham, found that there were few black craftsmen

in the area whom Stockham could hire. (139a) However,

the court inexplicably ignored the testimony by the same

witness that there are few white or black craftsmen avail

able to companies and that most individuals who become

craftsmen receive training on-the-job or as apprentices

from their employer. (1496a-1498a)

Similarly, superintenaants testified that workers had

to be trained by the Company for skilled positions. (1506a-

07a, 1557, 1567a-1568a, 1637a) The Company maintains appren

tice programs for the following crafts: Millwrights,

Pattermakers, Machinists, Electricians, Box Floor Molders,

Carpenters, Heat Treaters and Blacksmiths. (375a ) The

Company also trains employees for skilled jobs through

on-the-job training programs.

79/ The district court found that blacks have "never" been

excluded from craft positions and that the apprentice

program has "never" been restricted to whites. (193a)

This finding is as plainly contrary to the evidence as

the Court's finding that Stockham "at no time" maintained

a policy of assigning jobs on a racial basis.

31

Year: '65

(post 7/2)

' 66 '67 ' 6 8 '69 ' 70 ' 71 ' 72 ' 73 Total

Whites: 4 8 6 7 12 17 10 14 17 95

Blacks: - - - - 3 1 2 6

The supervisors of departments containing craft jobs re-

on/commend employees for the apprentice program. (1074a-76a)

The employees who are recommended by the craft department

supervisors must then be approved by an Apprenticeship Com

mittee composed of three Company superintendants. (1073a-1076a)

The Apprenticeship Committee routinely approves the supervisors'

81/

recommendations. (1076a-1077a)

The "paper" qualifications for admission to the apprentice

ship program have varied from July 2, 1965, through to the

' 82/

present. In A.ugust 1965 the Company instituted the use of

80/ The selection of apprentices is not subject to the collec

tive bargaining agreement and an employee may not file a

grievance concerning the Company's apprentice selection.

(1075a-1076a; 1261a) Local 3036 has negotiated, unsuccess

fully, for a joint Union-Company procedure for the

apprenticeship program. (1080a-1081a)

81/ An employee may request the supervisors to consider him for

an apprenticeship program by filing a "timely application",

see infra at 50 n.129. However, it is not necessary for an

employee to file a timely application in order to be con

sidered and selected for the apprenticeship program. (1075a)

In fact, only 38 out of the 101 selected for the apprentice

ship program between July 2, 1965, and December 31, 1973,

filed timely applications. (DX 64; see 198a)

§2/ The apprentice program is a 9000 hour program involving

on-the-job training and some classroom work.(PX 38, section,4;

1327a see 194a) An apprentice is paid according to the

number of hours he has spent in the program. (194a; DX 59)

Even with a "credit of hours" an employee who has Dee

Stockham for a number of years may well have to take

short-term loss in pay in order to enter the program,

which may provide a substantial obstacle to entrance.

I3l5a-I3l9a; see 194a)

32

the Wonderlic Test for selection of employees to the apprentice-

83/

ship program. An employee had to score at least an 18 on the

Wonderlic Test in order to be considered for the apprenticeship

84/

program. (733a, 3709a-10a) In 1969 the Company established a

committee to review the training programs at the plant; a sub

committee on the apprentice programs was also created. (1024a,

1141a, 332la-28a) The work of this sub-committee resulted in two

additional "paper" requirements for admission to the apprentice

program: (1) a high school diploma or G.E.D.; and (2) a 30-year

85/

age limit. The sub-committee did not make any attempt to

validate the high school diploma requirement, nor, in fact, did

the sub-committee even inquire as to the existence or effect of

86/

the previous educational requirement (grade school). (1147a-1148a)

As previously discussed in Section F, supra, blacks have

been denied access to on-the-job training programs for crane

operator, box-floor molder and machinist in the Valve Tool Room.

83/ In addition, the Bennett Mechanical Test has been adminis

tered since 1953 to employees who are being considered for

the apprentice program (PX 18, Ans. to Interrog. No. 29;3048a-49a)

84/ Stockham ceased using the Wonderlic and Bennett tests in

April 1971. ( 216a) The use of employee testing is dis

cussed fully, infra section "I" .

85/ See the Training Manual established by the sub-committee,

PX 38, rules 2.1 and 2.2; compare a pre-1969 apprentice

contract, PX 36, with a post-1969 apprentice contract,

PX 37. (Compare 3268a with 3261a-62a; see 196a, 1141a). These

requirements may be waived in the discretion of the Appren-

tiseship Committee. (196a-97a; 1141a-42a)

8W Despite the court's finding to the contrary (196a)

evidence as introduced by the Company's own expert was

uncontroverted that fewer blacks proportionate to whites