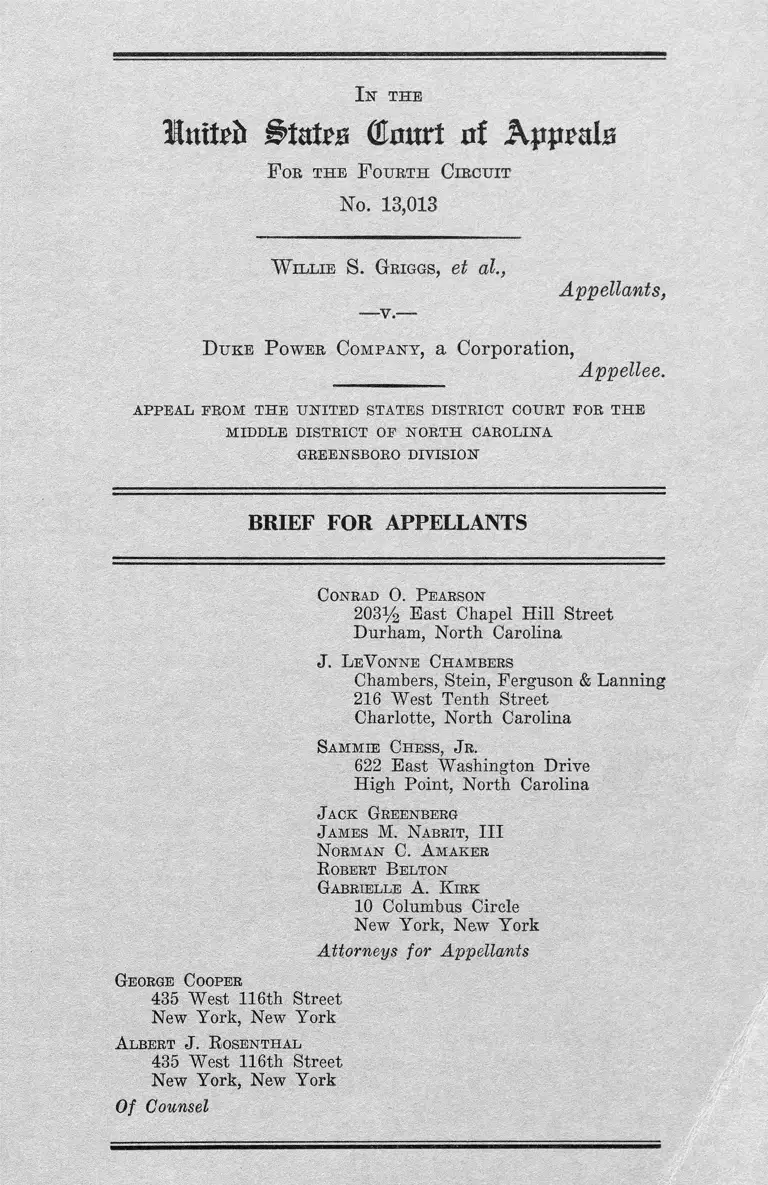

Griggs v. Duke Power Company Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Griggs v. Duke Power Company Brief for Appellants, 1968. 96f2bfdd-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/859f9edd-e1b5-4b59-9b99-ca1be4eda744/griggs-v-duke-power-company-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

luttei* States (to rt of Appeals

F ob the F ourth Circuit

No. 13,013

W illie S. Griggs, et al.,

Appellants,

—v.—

D uke P ower Company, a Corporation,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM T H E U N ITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR T H E

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NO RTH CAROLINA

■GREENSBORO DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Conrad 0. Pearson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

J. LeVonne Chambers

Chambers, Stein, Ferguson & Lanning

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

Sammie Chess, J r.

622 East Washington Drive

High Point, North Carolina

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Norman C. Amaker

Robert Belton

Gabrielle A. K irk

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

George Cooper

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York

Albert J. Rosenthal

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York

Of Counsel

I N D E X

B rief :

Questions Involved...................................................... . 1

Statement of the Case .................................................. 2

Statement of the F ac ts .................................................. 4

Summary of Argument.................................................. 7

A rgument

I. The Transfer Requirements Constitute an Un

lawful Double Standard Based on Race .......... 13

II. Even If the High School and Test Require

ments Were Imposed Equally on All Em

ployees, These Requirements Would Be Un

lawful Because They Are Unjustifiably Based

on Racial Characteristics .................................. 19

A. The General Principle Regarding- Tests

and Educational Requirements — The

Need for Proper Study and Evaluation 19

B. The Legal Authorities Regarding Test

and Educational Requirements................ 32

C. The Evidence Showing a Lack of Busi

ness Need for Duke’s Discriminatory

Transfer Requirements ............................ 35

1. The High School Diploma Re

quirement ........................ 35

2. The Test Requirement ................... 38

III. Duke’s Discriminatory Practices Derive No

Protection From Section 703(h) of Title V II .... 40

PAGE

11

PAGE

IV. The Case Should Be Remanded With Directions

to the District Court to Fashion an Appropriate

Remedy ............................................................... 46

Conclusion ................................................................................... 47

A p pe n d ix :

Extracts from Title VII .............................................. 49

Decision of EEOC, Dec. 2, 1966, CCH Employment

Practices Guide, Tf17,304.53 ............................. 51

Decision of EEOC, Dec. 6, 1966, CCH Employment

Practices Guide, 1117,304.5 .......................................... 53

Mitchell, Albright & McMurray, Biracial Validation of

Selection Procedures in a Large Southern Plant, in

Proceedings of 76th Annual Convention of American

Psychological Association, Sept., 1968 ..................... 56

Order on Validation of Employment Tests by Contrac

tors and Subcontractors, 33 Fed. Reg. 14302, at

§2(b), 10 (Sept. 24, 1968) ....................................... 58

T able op Cases:

Banks v. Lockhead-Georgia Co., 58 Lab. Gas. fl9131

(N.D. Ga. 1968) ........................ 41

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .... 21

Dobbins v. IBEW, 58 Lab, Cas. H9158 (S.D. Ohio

1968) ................................................................ 8,10,16,34

Donahue v. Evy Footwear, Inc., Case 01867-48 ...... 20

Dunlap v. United States, 70 F.2d 35 (7th Cir. 1934) .... 41

Erie Resistor Co. v. N.L.R.B., 373 U.S. 221 (1963) .... 41

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) ............. 20

PAGE

iii

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S, 347 (1915) ..........13,17

Hicks v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 58 Lab. Cas. 1(9145

(E.D. La. 1968) .........................................................8,15

Hicks v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., C.A. 16638 (E.D.

La. 1967) .................. ............. ...................................... 23

Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401 (D.D. C. 1967) .... 28

International Chem. Workers v. Planters Mfg. Co.,

259 F. Supp. 365 (N.D. Miss. 1966) ......................... 33

Johnson v. Rita Associates, Inc., Case C12750-66 ...... 20

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1939) ........................ 13,17

Motorola Decision, reprinted 110 Cong. Rec. 9030-9033

(1964) ........................................................................44,45

Norwegian Nitrogen Prods. Co. v. United States, 288

U.S. 294 (1933) ........................................................... 33

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D.

Ya. 1968) .................................................. ....4,8,15,16,41

Rosenfeld v. Southern Pacific Co., 59 Lab. Cas. H9172

(S.D. Calif. 1968) ....................................................... 41

Ross v. Dyer, 312 F.2d 191 (5th Cir. 1963) ................. 17

Skidmore v. Swift, 323 U.S. 134 (1944) ........................ 33

State Commission for Human Rights v. Farrell, 43

Misc. 2d 958, 252 N.Y.S. 2d 649 (Sup. Ct. 1964) ...... 17

United States v. American Trucking* Associations, 310

U.S. 534 (1940) ................................. 33

United States v. Dogan, 314 F.2d 767 (5th Cir. 1963) .... 17

IV

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Educa

tion, 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), aff’d on rehearing

en lane, 380 F.2d 385 (1967) ...... ............................ 33

United States v. Local 189, 282 F. Supp. 39 (E.D. La.

1968) ......................................................................8,16,41

Yolger v. McCarty, Inc., 55 Lab. Cas. IT9063 (E.D. La.

1967) ........................................................................... 8,16

S tatutes:

.42 U.S.C. §2000e, et seq.

Title VII, Civil Rights Act of 1964

Section 701(b), 42 U.S.C. $2000e(b) ..................... 38

Section 703(a)(2), 42 U.S.C. §2000e(a)(2) ....10,13,32

Section 703(h), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(h)-4 ....12,40,43, 45

Section 706(e) ......................................................... 3

Section 706(g), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g) ................. 40,46

Otheb A uthobities :

110 Cong. Rec. 8194 (1964) ......................................... 40

110 Cong. Rec. 13724 (1964) ....................................... 44

110 Cong. Rec. 13505 ..................................................... 44

110 Cong. Rec. 13503-04 ................................................ 44

110 Cong. Rec. 13492 (1964) ....................................... 44

110 Cong. Rec. 9024-42 (1964) ..................................... 43

88th Cong., 1st. Sess., 2-3 (1963)

H.R. Rep. No. 570 ............ 32

88th Cong., 1st. Sess., 138-41 (1963)

H.R. Rep. No. 914 ..................................................... 32

PAGE

V

88th Gong., 1st. Sess. (1963)

Hearings on Equal Employment Opportunity before

the Subcomm. on Employment & Manpower of the

Senate Comm, on Labor & Public Welfare .............. 32

88th Cong., 1st. Sess. (1963)

Hearings on Equal Employment Opportunity before

the General Subcomm. on Labor of the House Comm,

on Education & Labor .............................................. 32

BN A, Fair Employment Practices Guide at 451:842

(New Jersey) .............................................................. 35

1 Cronbach, Essentials of Psychological Testing, 86,

105, 119 (2d ed. 1960) ............................................... 29

CCH, Employment Practices Guide, 7121,060 (Colo

rado), 7127.295 (Pennsylvania) ....... ............... ......... 35

CCH, Employment Practices Guide, 718048 EEOC Re

lease, Nov. 2, 1968 ........ ............................................. 34

Coleman, J. Equality of Educational Opportunity, 219-

220 (1966) ................ 23

1 Davis, Admin. Law Treatise, §5.06 (1959) .............. 33

Decision of EEOC, Dec. 2, 1966, in CCH, Employment

Practices Guide, 7117,304.53 .............. 33

Decision of EEOC, Dec. 6, 1966, in CCH, Employment

Practices Guide, 7fl7,304.5 .......................................23, 34

EEOC, Guidelines on Employment Testing Proce

dures ................................................ 41

Freeman, Theory and Practice of Psychological Test

ing, 88 (3rd. ed. 1962) .............................................. 30

Ghiselli and Brown, Personnel and Industrial Psychol

ogy, 187-88 (1955) ............. 29,30

Ghiselli, The Generalization of Validity, 12 Personnel

Psychology, 397-398 (1959) ....................................... 28

PAGE

VI

Ghiselli, E., The Validity of Occupational Aptitude

Tests, 137 (1966) ............... ..................................10, 26, 27

Goslin, E. D., The Search for Ability, 137-39 (1963) .... 21

Hearings before the United States Equal Employment

Commission on Discrimination in White Collar Em

ployment, New York City, Jan. 15-18, 1968, at 46-48,

99, 377, 466 ................................................................ 31

Kirkpatrick, J., et ah, Testing and Fair Employment,

5 (1968) ...................................................................... 23

Lawshe and Balma, Principles of Personnel Testing

(2nd ed. 1966) ........ ................................. ................. 30

Lopez, Current Problems in Test Performance of Job

Applicants: 1, 19 Personnel Psych. 10-18 (1966) .... 28

Lopez, Evaluating the Whole Man, 2 The Long Island

University Magazine, 17-21 (1968) ........................ 28

Mitchell, Albright & McMarray, Biracial Validation

of Selection Procedures in a Large Southern Plant,

in Proceedings of 76th Annual Convention of Ameri

can Psychological Association, Sept., 1968 ..........23, 26

Note, Legal Implications of the Use of Standardized

Ability Tests in Employment and Education, 69

Colum. L. Rev. 691, 706, 713 (1968) ..................... 40,41

Order on Validation of Employment Tests by Contrac

tors and Subcontractors, 33 Fed. Reg. 14302, at

§2(b), 10 (Sept. 24, 1968) .......................................... 35

Ruch, Psychology and Life, 67, 456-57 (5th ed. 1958) .... 30

Ruda and Albright, Racial Differences! on Selection

Instruments Related to Subsequent Job Performance

21, Personnel Psych. 31-41 (1968) ............................ 28

PAGE

Vll

PAGE

Science Research Assoc., Inc., a subsidiary of IBM,

Business and Industrial Education Catalog, 1968-69,

at 4 ............................................................................... 25

Siegel, Industrial Psychology, 122 (1962) ...................... 30

State Commission for Human Rights, 1950 Report of

Progress, 40-41, 1951 Report of Progress, 35-36 ...... 20

Super & Crites, Appraising Vocational Fitness, 106

(Rev. ed. 1962) ......................................................... 26

The National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders

(the Kerner Commission), p. 416 (Bantam Books ed.

1968) ................................................................. 24

Thorndike, Personnel Selection Tests and Measurement

Techniques, 5-6 (1949) .............................................. 30

Tiffin and McCormick, Industrial Psychology 119, 124

(5th ed. 1965) ....... ............................... ..................... 30

U.S. Bureau of the Census, U.S. Census of Population:

1960, Vol. I, Part 35, Table 4 7 .................................. 21

Wonderlic Personnel Test Manual 2 (1961) —.6, 21, 23, 29, 30

I n the

(Euxtrt it! A p p a ls

F oe the F ourth Circuit

No. 13,013

W illie S. Griggs, et al.,

—v.—

Appellants,

D uke P ower C o m p a n y , a Corporation,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM T H E U N ITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR T H E

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

GREENSBORO DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Questions Involved

1. Where an employer, before the effective date of

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, hired only white

persons into its more attractive and better paying depart

ments without imposing any educational or testing re

quirements upon them, while relegating Negroes to its least

attractive department, may it subsequent to the effective

date of the Act continue to prohibit its Negro employees

from transferring to jobs in its better paying departments

unless they meet certain educational or testing require

ments—while permitting white employees to remain, and

receive promotions, in those departments without meeting

such requirements?

2. Does Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 forbid

an employer to use educational and testing requirements

2

in situations where the relationship of such requirements

to satisfactory job performance is unknown to the employer

and the requirements are known to discriminate against

Negroes on the basis of racial disadvantages created by

centuries of educational and cultural discrimination?

3. Are the interpretations of Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act, relating to testing and educational require

ments for employment promulgated by the Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Commission, the agency entrusted by

the statute with its administration and implementation, so

clearly wrong that they should be rejected by the courts?

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from the October 9, 1968, judgment of

the United States District Court for the Middle District

of North Carolina, dismissing a complaint on the merits

brought under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. §2000e, et seq. (R. 43a).

On March 15, 1966, appellants, Negro employees of ap

pellee, Duke Power Company, at its Dan River Steam Sta

tion, tiled charges of discrimination with the Equal Em

ployment Opportunity Commission alleging that the com

pany was discriminating against them on the ground of

race in that (a) Negro employees were restricted to the

laborer and semi-skilled laborer classifications, (b) the re

quirements for promotion for Negro employees were not

required of white employees, and (c) locker rooms, show

ers, water fountains and toilets were segregated on the

basis of race (R. lb).

On September 8, 1966, the Commission found reasonable

cause to believe that the company was in violation of Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in that an investiga

3

tion disclosed that Negro employees were limited to the

lowest job classifications; that the highest paid Negro em

ployee earned less than the lowest paid white employee;

that Negro employees with as many as 20 years of seniority

had not been promoted out of the laborer classification;

that white employees who did not have a high school edu

cation were promoted to higher paying positions whereas

Negro employees who did not have a high school education

were required to pass a battery of tests in order to be

considered for promotions out of the laborer’s category;

that white employees were allowed to work overtime

whereas Negro employees were not; and that the company

maintained segregated facilities (E. 2b-4b). Subsequently,

each of the plaintiffs received notice of his right to sue

under section 706(e) of the Act (R. 5b) and this suit fol

lowed.

The complaint filed on October 20, 1966, alleged that the

company was pursuing a policy and practice of limiting the

employment opportunities of Negro employees because of

race in promotions and transfers, wages, overtime and use

of facilities (R. 3a-9a). The claim as to segregated facili

ties was subsequently abandoned by the appellants.

The company challenged the standing of appellants to

bring this action as a class action as the class was desig

nated in the complaint and amended complaint filed on

April 12, 1967. On June 19, 1967, Judge Edwin M. Stanley

entered an order allowing appellants to bring this action

as a class action. Judge Stanley ruled that the class which

appellants could represent consisted of those Negro per

sons presently employed as well as those who may be sub

sequently employed by the company at Dan River and that

plaintiffs could represent all Negro persons who might

thereafter seek employment at Dan River provided that

plaintiffs could show at least one Negro plaintiff of the

6

At the present time Duke has apparently dropped its

formal policy of restricting all Negroes to the Labor De

partment. However, the effect of that policy has largely

been preserved by a company policy precluding anyone

from transferring to any job in the Coal Handling Depart

ment or in one of the “inside” departments unless he either

(1) has a high school diploma or (2) achieves a particular

score on each of two quickie “intelligence” tests—the 12

minute Wonderlic test and the 30 minute Bennett test

(sometimes referred to as the “Mechanical AA” in the

Record) (R. 20b-22b). These requirements were adopted

without study or evaluation. They apply even to several

Negro laborers who have worked in the Coal Handling

Department for many years and thereby gained experience

and familiarity with the operations of the department (R.

106a, 124b). On the other hand, the requirements have no

application to anyone already in the Coal Handling Depart

ment or an “inside” department either as a requirement

of maintaining his present position or as a condition to

further promotion within his departmental area (R. 102a).

The practical effect of this dual transfer requirement has

been to freeze all but two or three Negroes in low paying

jobs as laborers. On the other hand, employees in the

“inside” departments, all of whom are white, are free to

remain there and to receive promotions in the “inside” de

partments to the best paying jobs in the plant (from

$3.18 to $3.56 per hour) without meeting either of these

requirements (R. 72b, 102a). Within the past three years,

for example, white employees with as little as seventh grade

educations have been promoted to jobs paying $3.49 per

hour in “inside” departments (R. 83b, 127b). Likewise,

employees in the Coal Handling Department, all of whom

are white except for one Negro high school graduate trans

ferred there in 1966, are free to remain on their jobs and

7

be promoted to the top job in the department paying $3.41

per hour.2

The first of these transfer requirements (high school

diploma) has been in effect for a number of years (R.

20b). The second (passing a test battery) is a new require

ment adopted in September, 1965, in response to a request

from a number of white non-high school graduates in the

Coal Handling Department who wanted an alternative

chance for promotion to inside jobs (R. 85a-87a). Both are

being challenged by appellants on the grounds that (1)

they impose a special burden on Negro employees at Dan

River not equally imposed upon white employees, and (2)

that they constitute improper and discriminatory require

ments for transfer.

Summary of Argument

This case presents, as a matter of first impression at the

Court of Appeals level, a question that is crucial to the

efficacy of Title YII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Does

the Act cover patterns and practices which effectively dis

criminate against Negroes when those patterns and prac

tices are superficially color-blind! If the Act does not

cover such patterns and practices, as the Duke Power Com

pany argues, employers will be free to grant gross prefer

ences to whites, and the ability of Title VII to provide true

equal job opportunity will be largely nullified. This can be

2 The only whites on whom the transfer requirements have any

impact are those who work outside the plant in the Coal Handling

Department and the watchman job and wish to transfer inside. It

was at the request of these employees that the test alternative was

introduced. However, since the Coal Handling Department leads

to a top pay rate of $3.41, the impact of transfer requirements

on these employees is far less harsh than that on Negroes who are

frozen in hopelessly low paid jobs. Moreover, only fifteen of eighty-

one white employees are in these outside jobs (R. 73b).

8

seen by examining the impaet of Duke’s transfer require

ments, which on the surface are non-racial requirements.

These transfer requirements produce a racially discrimina

tory pattern or practice for two very important reasons.

I. The Transfer Requirements Constitute an Unlawful

Double Standard Based on Race.

No Negro can obtain a job in any of the better depart

ments without meeting the transfer requirements. On the

other hand, the better departments are populated by many

whites who do not meet these requirements and who are

free to remain there and be promoted to high paying jobs

in those departments. These are whites who entered the

departments before the requirements were imposed. No

Negro is in this preferred position because Negroes were

racially barred from the better departments during the

period before the requirements were imposed.

This system, which grants a preferred position to in

cumbent whites that is denied to all Negroes, preserves and

perpetuates the effects of Duke’s past discrimination and

will maintain its white employees in a superior promo

tional position for years to come. The District Court found

this lawful, holding that Title VII does not cover the

present effects of past discrimination. This holding is con

trary to all authority under Title VII. See Quarles v.

Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D. Va. 1968);

United States v. Local 189, 282 F. Supp. 39 (E.D. La. 1968);

Hicks v. Croivn Zellerbach Corp., 58 Lab. Cas. H9145

(E.D. La. 1968); Dobbins v. 1BEW, 58 Lab. Cas. j[ 9158,

at p. 6635 (S.D. Ohio 1968); Vogler v. McCarty, Inc., 55

Lab. Cas. ff 9063 (E.D. La. 1967). The District Court was

clearly wrong and this ground alone is sufficient to warrant

reversal.

9

II. Even I f the High School and Test Requirements Were

Imposed Equally on All Employees, These Require

ments Would Be Unlawful Because They Are Unjusti

fiably Based on Racial Characteristics.

These requirements bar Negroes from better jobs, not

because of inability to do the jobs, but because of racial

characteristics flowing from cultural and social patterns

produced by centuries of discrimination.

A. The General Principle Regarding Tests and Educational

Requirements.

Racial discrimination arises not only when employment

decisions are openly based on race, but also when they are

based on racial characteristics which prefer whites over

Negroes. A long history of open discrimination against

Negroes in education and economic opportunity has pro

duced a situation where educational requirements or tests

related to education (such as those at Duke) operate to

prefer whites over Negroes by three or more to one.

These racial characteristics may appropriately be used

to deny job opportunity to Negroes where necessary to

satisfy an employer’s business needs. We do not even wish

to suggest that Title VII may require an employer to hire

unqualified Negroes. But where these characteristics are

relied upon to exclude Negroes to an extent not required

by business needs, it is a form of racial discrimination

which can and must be barred if Title VII is to be effective.

In assessing this crucial question of business need, it

should be clear that a test or educational requirement

cannot be viewed as a business necessity simply because the

employer asserts that he believes it is. Such an unsubstan

tiated assertion could, and probably would, be made in

every case. Sound business practice requires study and

10

evaluation of job requirements and needed skills and selec

tion of procedures to appraise those skills on the basis of

rational judgment and careful evaluation. It has been re

peatedly demonstrated in hundreds of studies that, when

adopted without proper study, tests “do not well predict

success on the actual jobs.” 3 The same is true of a high

school diploma requirement. For this reason, no test or

education requirement grossly preferring whites over Ne

groes can fairly be assumed to be a business necessity

absent adequate evidence from the employer in question

that the requirement is supported by appropriate study and

evaluation.

B. The Legal Authorities Regarding Tests and Educational

Requirements.

An examination of Title VII leaves no doubt that racial

discrimination accomplished through the subtlety of un

necessary educational or test requirements was to be

barred. The statute prohibits any limitation or classifica

tion of employees which “tends to deprive” or “otherwise

adversely affect” status because of race. Section 703(a) (2),

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(a)(2). In light of the racial character

istics on which they are based, an unnecessary educational

or test requirement which screens out Negroes at three or

more times the rate of whites clearly violates this provi

sion. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission,

the agency charged with administration and implementa

tion of Title VII, has so ruled, as has the one Federal

Court (other than the District Court below) to consider

the question. Dobbins v. IBEW, 58 Lab. Cas. U 9158 (S.D.

Ohio 1968). The Office of Federal Contract Compliance

(enforcer of the President’s Executive Order against dis

8 See E. Ghiselli, The Validation of Occupational Aptitude Tests

51 (1966).

11

crimination by government contractors) has adopted a sim

ilar policy.

C. The Evidence Showing a Lack of Business Need for

Duke’s Discriminatory Transfer Requirements.

The crucial issue is the business need for the require

ments adopted by Duke. The evidence in this case shows

that Duke’s educational and test requirements are no|

based on business need and were adopted without proper

study and evaluation. A lack of need is clearly demon

strated by Duke’s readiness to permit present white em

ployees in better departments to stay and be promoted

without meeting these requirements. However, even if this

irrefutable evidence of lack of need were not present, it

would be clear that the requirements are not demanded by

business needs.

1. The High School Diploma Requirement—Company

officials testified that this requirement was adopted with

out study or evaluation and without any particular evi

dence that it would serve the employment needs of the com

pany. It was adopted on the basis of what can be charitably

described as a blind hope. Any company in the world could

advance a similar basis for use of a high school diploma

requirement or some other educational requirement which

similarly preferred whites over Negroes, by three to one.

2. The Test Requirement — This requirement was

adopted in an attempt to protect a group of white em

ployees in Coal Handling from the burdens of the high

school diploma requirement. As in the case of the high

school requirement it was adopted without study, evalua

tion or validation. Attempts at relating test scoring to job

success have been unsuccessful. Its only justification is as

a substitute for the high school requirement and if that

falls the test requirement must also fall.

12

III. Duke’s Discriminatory Practices Derive No Protection

From Section 703(h) of Title VII.

Section 703(h) provides that an employer may rely upon

a “professionally developed ability test” which is “not de

signed, intended, or used to discriminate.” This section of

course has no relevance to the high school diploma require

ment which clearly violates Title VII for the reasons set

out above. While section 703(h) could have relevance to

the test requirement, it does not apply because Duke’s tests

are not “professionally developed” within the meaning of

the statute, are “intended” to discriminate, and are being

“used” to discriminate even if not so intended.

IV. The Case Should Be Remanded With Directions to the

District Court to Fashion an Appropriate Remedy.

Because the fashioning of a remedy will require the care

ful evaluation of certain employment records, a remand

with directions to the District Court is the appropriate

relief in this case.

13

ARGUMENT

I.

The Transfer Requirements Constitute an Unlawful

Double Standard Based on Race.

It is elemental in the enforcement of fair employment

that an employer cannot establish two unequal standards

and demand that Negroes meet the higher one while per

mitting white to qualify under the lower one. The law for

bids not only a categorical refusal to promote a Neg*ro, but

also any limitation or classification which would “tend to

deprive” him of employment opportunity because of race.

See section 703(a)(2), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(a)(2). If Duke

had openly declared that wdiites and only whites were

exempted from its high school and test requirements there

would have been no doubt that these requirements would

have been an unlawful double standard. Duke has not made

such an open declaration. But an examination of the im

pact of the transfer requirements shows that the same thing

has been done without an open declaration. These transfer

requirements are nothing more than the time worn “grand

father clause” approach to segregation wearing a modern

industrial cloak. Cf. Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347

(1915); Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1939).

The “inside” departments and Coal Handling all lead to

well paid jobs on which a satisfying career can be built.

The Labor Department is low paid and unpromising for a

decent career. Since Duke’s earlier open discrimination had

relegated every Negro to the Labor Department prior to

the time that the transfer requirements were imposed, every

Negro must now meet the requirements to obtain a decent

job. Whites, on the other hand, who were in better depart

ments prior to imposition of the requirements, are now free

14

to stay on their jobs and to be promoted to the highest pay

ing jobs in the plant even if they do not meet the require

ments, as a large percentage of whites, in fact, do not

(B, 127b).

In many situations where a middle or upper level job in

one of the better departments is open, a Negro from the

Labor Department may be eligible to compete directly

against a white for the job.4 The Negro must pass the high

school or test requirements. The white normally need not.

Thus this case presents a situation where a burden is

placed on incumbent Negro employees from which incum

bent whites are effectively exempted. Whites are exempted

because they have a status that Negroes never had a chance

to get due to Duke’s past overt discrimination. The impos

ing of this additional burden on Negroes preserves and

perpetuates the effects of Duke’s past discrimination by

maintaining its white employees in a superior position. The

company was appropriately solieitious of the career aspira

tions of its white employees who did not meet high school

and test requirements. By extending an exemption on a

departmental basis they have effectively protected those

whites while freezing Negroes in a situation with no career

opportunity. We ask only that Negroes be entitled to the

same solicitude as whites.

The District Court found Duke’s preferential practice

lawful, holding that Title VII does not cover the present

effects of past discrimination (B. 36a). If this meant only

that the Act does not retroactively apply to pre-1965 dis

crimination, it would be clearly correct. But to the extent

that it means, as the District Court seems to have intended,

that an employer who put his Negro employees in an in

ferior position before 1965 may freely penalize them now

4 Transferring employees at Dan River are potentially eligible

to move into another department above the entry level (R. 38a-40a).

15

as a result of this status, it is in direct conflict with the

other authoritative decisions on this question, most im

portantly Judge Butzner’s decision in Quarles v. Philip

Morris, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D. Ya. 1968).

The key issue in Quarles, as in the present case, was the

legality of a department promotional system which con

tinued the effect of prior segregation. In Quarles, promo

tions were made on the basis of seniority within a depart

ment under a longstanding practice. Since the better de

partment in the plant had been foreclosed to Negroes until

the mid-1960’s, many whites had accumulated substantial

departmental seniority in this department while Negroes

had little or none. The court in Quarles pointed out the

disadvantages suffered under this system by a Negro who

had worked for the company for ten years but had been

relegated to a less attractive department because of his

race, as compared with a white employee who had been

with the company for a shorter period but had been allowed

to start work in the desirable department. Although the

allocation of these employees to their respective depart

ments had occurred before the effective date of the Act, con

tinued promotions on the basis of departmental seniority

after the effective date of the Act caused the Negro to

suffer continuing disabilities as to job opportunities in the

desirable department. Since operation of the company’s

business on departmental lines served “many legitimate

management functions” the departmental structure itself

could not be found unlawful. 279 F. Supp. at 513. But the

use of a departmental seniority system could be unlawful

insofar as it perpetuated the effects of past discrimination.

The crucial question, as stated by Judge Butzner, was:

“Are present consequences of past discrimination cov

ered by the act [Title VII] V’ 279 F. Supp. at 510.

The answer, after an extensive analysis of the legislative

history, was affirmative. The court ordered the company to

16

establish a new promotional system that would not penalize

Negroes for lacking the seniority they had been discrimina-

torily denied. 279 F. Supp. at 519-21.

The situation at Duke’s Dan River Station is virtually

indistinguishable from that in Quarles. In both situations

the company’s promotional standards appear to be non-

racial. However, Negroes have been put at a promotional

disadvantage relative to their white counterparts because

of past discrimination. In Quarles the promotional dis

advantage was lesser seniority. At Duke the disadvantage

is even worse—an absolute promotional bar to nonqualify

ing Negroes from which whites are effectively exempted.

In both cases the question is whether the employer can

continue to rely on the discriminatorily created disadvan

tage after the effective date of Title VII. We submit that

the conclusion reached in Quarles is the only sound one. To

hold otherwise, as did the District Court in the present

case, would, in Judge Butzner’s words, tend to “freeze an

entire generation of Negro employees into discriminatory

patterns that existed before the act” in violation of con

gressional intent. Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F.

Supp. at 516.

The decision in Quarles was expressly followed in United

States v. Local 189, 282 F. Supp. 39 (E.D. La. 1968), where

Judge Heebe held that a job seniority system (similar in

effect to the departmental seniority in Quarles) is unlawful

under Title VII because it “perpetuates the consequences

of past discrimination.” Accord, Hicks v. Crown Zeller-

bach Corp., 58 Lab. Cas. U9145 (E.D. La. 1968); Dobbins

v. IBEW , 58 Lab. Cas. H9158, at p. 6635 (S.D. Ohio 1968).

To the same effect is Vogler v. McCarty, Inc., 55 Lab. Cas.

H9063 (E.D. La. 1967) where Judge Christenberry struck

down a union requirement that new members be related to

old members. This requirement was non-racial on its face,

but, as in the Quarles and Duke Power Co. situations, a

17

past practice of Negro exclusion from the union made this

requirement unlawfully discriminatory.6

The approach taken by the Duke Power Company—fol

lowing a “non-racial” rule which perpetuates the effects of

its past discrimination—has obvious parallels in other civil

rights contexts. A recent example of this tactic in the vot

ing rights area was described in United States v. Bogan,

314 F.2d 767 (5th Cir. 1963). The defendant, a sheriff, is

sued instructions that any person coming in to pay a poll

tax for the first time, “black or white” be required to see

him personally. The rule was reasonable on its face and

non-racial. However, the court found that substantially all

of the eligible whites had previously been permitted to pay

the poll tax and that not one of the eligible Negroes had

done so, and drew this conclusion:

“Obviously a blanket requirement that all persons who

have never paid the poll tax before, that being a rela

tively small percentage of white people and all Negroes,

who now desire to pay their poll taxes for the first

time must see the Sheriff personally operates unequally

and discriminatorily against the Negroes.” 314 F.2d at

772.

This same principle has been recognized in many other situ

ations. See Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1939) (voting

rights); Guinn v. United States, 238 TT.S. 347 (1915) (voting

rights); Ross v. Dyer, 312 F.2d 191 (5th Cir. 1963) (school

desegregation).

The point is clear. Title VII is violated if an employer

gives preference in future promotions on the basis of a

status discriminatorily denied Negroes prior to the effective

date of Title VII.

6 Cf. State Commission for Human Bights v. Farrell, 43 Misc. 2d

958, 965-966, 252 N.Y.S. 2d 649 (Sup. Ct. 1964) (family prefer

ence for union membership struck down under New York fair em

ployment law).

18

This principle will have only slight consequences on an

employer’s promotional arrangements. I t will not limit at

all the requirements he may set for promotion, but rather

will demand that those requirements be applied equally to

all employees without regard to discriminatorily denied

status. In the context of this case, the principle means that

since Duke has chosen to give white employees in the bet

ter departments an exemption from educational and test

requirements, and has over the past few years frequently

upgraded white employees not meeting the requirements,

that same treatment must be extended to Negroes who were

discriminatorily excluded from the better departments.

That is, the high school and test requirements must be

waived with regard to Negroes subjected to this discrimina

tory exclusion.

It cannot be contended that the appellants are seeking

to apply Title YII retroactively or to redress discrimina

tion which occurred before the effective date of Title YII.

We are not asking that white employees who received jobs

or promotions in the attractive departments because of

racial discrimination now be made to give them up. All

that we seek is that as future opportunities for positions

in these departments open up, Negro employees already

working at the plant not be subjected to further, additional,

future disadvantage because of discrimination in the past.

This relief need apply only to Duke’s present Negro em

ployees, and only to those who were hired at a time when

Negroes were barred from the better departments. These

constitute the appellant class in this case. For the future,

Duke will presumably not be denying its new Negro em

ployees any status because of race. The principle upon

which relief is being extended to present employees—that

they are victims of past discrimination which is being per

petuated—will not apply to these new employees.

19

II.

Even If the High School and Test Requirements

Were Imposed Equally on All Employees, These Re

quirements Would Be Unlawful Because They Are Un

justifiably Based on Racial Characteristics.

The argument in Section I has demonstrated that the

application of educational and test requirements at the Dan

River Steam Station is an unlawful reliance on status

created by past discrimination to deprive Negroes of future

promotional opportunity. However, even if applied equally

to whites and Negroes, i.e., with no departmental exemp

tions, these particular requirements would create unlawful

racial discrimination. These requirements are not justified

by Duke’s business needs. Yet the use of these requirements

greatly prefers whites over Negroes on the basis of racial

characteristics flowing from cultural and social patterns

produced by centuries of discrimination. This is a form of

racial discrimination which is, and must necessarily he,

forbidden by Title VII. If it were not forbidden, any em

ployer would be free to grant arbitrary gross preferences

to whites and drastically undercut Negro employment op

portunity.

A. T he General Principles Regarding Test and Educational

R equirem ents— T he Need fo r Proper S tudy and Evalua

tion.

If this were a world with no backlog of racial discrimina

tion, it might be possible to effectively enforce a fair em

ployment law simply by barring future discrimination that

is openly grounded on race. However, this narrow approach

will not suffice in the United States where the accumulated

impact of centuries of discrimination has created racially

derived cultural and social patterns which lead to discrimi

nation from seemingly neutral requirements. For example,

20

housing discrimination has produced a pattern of racial

ghettos in most cities. Discrimination flowing from a char

acteristic of that racial housing pattern (for example, a

refusal to hire persons coming from a designated area of

the city which approximated the Negro ghetto) would he

superficially color blind, but would nonetheless be a form

of racial discrimination. This discrimination would be un

lawful notwithstanding the fact that, because of the impos

sibility of precision in drawing geographical lines and the

possibility of future population shifts, it might also exclude

some whites and might allow some Negroes to slip through.

This was made clear in Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339

(1960) where, in striking down gerrymandering tied to

racial housing patterns, Mr. Justice Frankfurter pointed

out:

“It is difficult to appreciate what stands in the way of

adjudging a statute having this effect invalid in light

of the principles by which this Court must judge, and

uniformly has judged, statutes that, howsoever spe

ciously defined, obviously discriminate against colored

citizens.” 364 U.S. at 342.6

Duke has not chosen to base its discrimination on hous

ing patterns. Instead it has used educational and cultural

patterns which are also directly traceable to race. The ap

pellants, who were born black, received a different educa

6 This same principle has been recognized repeatedly in the en

forcement of the New York State fair employment law. Employers

have been forbidden from insisting on Yiddish-speaking employees

(.Donahue v. Evy Footwear, Inc., Case C1867-48 (unlawful pref

erence to Jews)) ; from requiring that employees have attended an

“out-of-town college” (State Commission for Human Rights, 1950

Report of Progress 40-41, 1951 Report of Progress 35-36 (unlawful

national origin discrimination against recent immigrants as well

as racial discrimination)) ; and from requiring that employees have

prior experience working in an East Side hotel (Johnson v. Bita

Associates, Inc., Case C12750-66 (discrimination against Negroes,

few of whom have such experience)).

21

tion in segregated schools and grew up in a different cul

tural environment than they would have had they been born

white. They were forced to drop out of school earlier be

cause of economic necessity produced by discrimination and

because discrimination led them to conclude that they could

not make use of further education. These facts are largely

true even for the Negro child born today. They are over

whelmingly true for appellants, many of whom finished

their schooling before the 1954 Brown decision began the

erosion of pervasive practices of segregation and discrimi

nation. The resulting inferior education and a tendency to

earlier dropping out of school are racial characteristics of

appellants just as clearly as is living in a ghetto.

Because it is based on these racial characteristics, the

high school diploma requirement tends to deny promotion

to all but a few Negroes while keeping jobs open for a large

proportion of whites. As of the last census, only 12% of

North Carolina Negro males had completed high school, as

compared to 34% of North Carolina white males.7 At the

time of the 1950 census, when the school doors had closed

for many of the appellants, the disparity was even worse—

8% for Negroes and 27% for whites.8

The statistics on performance on the tests used by Duke

are not much different from these high school diploma

figures. Performance on these tests is closely related to

educational and cultural background.9 The Wonderlic test

is a mixture of questions on vocabulary, mathematics, and

other subjects, with a heavy emphasis on vocabulary and

reading ability.10 A testee is expected to answer questions

such as:

7 U.8. Bureau of the Census, U.S. Census of Population: 1960,

Yol. I, P art 35, at Table 47, p. 167.

8 Ibid.

9 See, e.g., D. Goslin, The Search for Ability 137-39 (1963).

10 A copy of the test is reprinted at R. 101b-103b.

22

“No. 11. A dopt A dept—Do these words have

1. Similar meanings,

2. Contradictory,

3. Mean neither same nor opposite?”

# * #

“No. 19. R eflect R eflex—Do these words have

1. Similar meanings,

2. Contradictory,

3. Mean neither same nor opposite?”

* # *

“No. 24. The hours of daylight and darkness in

S eptember are nearest equal to the hours of

daylight in

1. June

2. March

3. May

4. November”

The ability to answer such questions is obviously related

to formal schooling and cultural background. The vocabu

lary questions call for an appreciation of subtle differences

in word meanings and parts of speech;11 the question of

hours of daylight cannot be answered reliably without

knowledge of the vernal equinoxes.11 12 The questions on the

Bennett test are not so obviously academic, but they none

theless involve an understanding of physical principles

11 We cannot resist comment on the irony of asking about such

verbal subleties in a question with such poor grammar. The answer

to No. 19 is particularly obscure and indicates the level of difficulty

of the exam. “Reflect,” a verb (“to bend or throw back” says

Webster) and “reflex,” as an adjective (“turned, bent or reflected

back” says Webster) have similar meanings in one sense. But in

the sense that it is inaccurate to equate meanings of different parts

of speech, they mean neither same nor opposite.

12 The correct answer to No. 24 is March. That is the month of

the vernal equinox and has approximately the same daylight as

September, the month of the autumnal equinox. Without this

scientific knowledge, one might easily guess May or June (begin

ning of summer as compared to September as end of summer) or

November (closest available month to September).

23

which are taught in school. As a consequence of the educa

tional and cultural orientation in these tests, it is univer

sally recognized that the average Negro score is much

lower than the average white score, particularly in areas

such as the South where the disparity in educational op

portunity is greatest.13 The Equal Employment Opportu

nity Commission has reported one typical case where a

requirement of the Wonderlic test plus one of several

others, including the Bennett, resulted in 58% of whites

passing the tests but only 6% of Negroes.14

These statistics make one very salient point. If require

ments such as a high school diploma or passage of “intelli

gence” tests could freely be imposed by any employer,

every employer in North Carolina and throughout the

South could create a promotional preference of three or

more to one in favor of whites. The free use of such re

quirements, which the District Court’s ruling would permit,

would effectively hold Negro employment opportunity to a

bare minimum.

Title VII boldly proclaims itself an “Equal Employment

Opportunity Act.” The free use of requirements based on

educational and cultural patterns mocks this title. Negroes

are never going to have equal employment opportunity if

employers may freely give gross preferences to whites by

capitalizing on well established racial patterns.

13 See, e.g., J. Kirkpatrick, et al., Testing and Fair Employment

5 (1968) ; J. Coleman, Equality of Educational Opportunity, 219-

220 (1966).

14 Decision of EEOC, Dec. 2, 1966, in CCH Employment Prac

tices Guide 1(17,304.53, reprinted in Appendix hereto at pp. 51-52.

See Mitchell, Albright & McMurry, Biraeial Validation of Selection

Procedures in A Large Southern Plant, in Proceedings of 76th

Annual Convention of American Psychological Association, Sept.,

1968, reprinted in Appendix hereto at pp. 56-57 (twice as many

whites as Negroes pass Wonderlic) ; Plaintiffs Exhibit No. 25, Hicks

v. Crown Zellerbach Cory., C.A. 16638 (E.D. La. 1967) (Study

showing that four times as many whites as Negroes pass Wonderlic

and Bennett tests).

24

An employer is, of course, permitted to set educational

or test requirements that fulfill genuine business needs.

For example, an employer may require a fair typing test

of applicants for secretarial positions. It may well be that,

because of long-standing inequality in educational and

cultural opportunities available to Negroes, proportionately

fewer Negro applicants than white can pass such a test.

But where business need can be shown, as it can where typ

ing ability is necessary for performance as a secretary, the

fact that the test tends to exclude more Negroes than whites

does not make it discriminatory. We do not wish even to

suggest that employers are required by law to compensate

for centuries of discrimination by hiring Negro applicants

who are incapable of doing the job. But when a test or

educational requirement is not shown to be based on busi

ness need, as in the instant case, it measures not ability to

do a job but rather the extent to which persons have ac

quired educational and cultural background which has been

denied to Negroes. In such a situation, these requirements

discriminate against Negroes just as surely as a practice

of overt discrimination. The National Advisory Commis

sion on Civil Disorders (the Kerner Commission) recog

nized this:

“Racial discrimination and unrealistic and unnecessarily

high minimum qualifications for employment or promo

tion often have the same prejudicial effect.” 15

The crucial question, then, is the business need for the

requirements in question. In assessing business need, it

should be clear that a requirement cannot be viewed as a

business necessity simply because the employer asserts that

he believes it is. If so, Title VII would be largely nullified

because such an unsubstantiated assertion could, and prob- 16

16 Commission Report at 416 (Bantam Books ed. 1968).

25

ably would, be made in every case. Sound business practice,

as outlined in the testimony of appellants’ expert witness,

Dr. Richard Barrett, calls for an employer to make a care

ful analysis of the exact tasks involved in his jobs and to

determine precisely what, skills and abilities are needed

to carry out those tasks. After such an analysis, the em

ployer can select, on the basis of informed judgment, pro

cedures which will rationally and fairly appraise those

skills. He should then try out those procedures to make

certain they are appropriate to the population and jobs at

his plant, a process known as validating the procedures

(R. 125a-129a).16

Unless this careful procedure is followed, an employer

is simply speculating in the dark when he imposes a re

quirement. The thing that makes educational and test re

quirements so appealing is that they have a superficially

plausible relationship to business need. But study has

shown that this relationship is nothing more than superfi

cial. This has been proven time and again in careful studies

by industrial psychologists investigating the “validity” of

standard tests such as the Wonderlic and the Bennett in

predicting an individual’s ability to perform industrial

jobs. This job performance ability is of course the best

measure of how well the individual satisfies business needs.

It has been demonstrated in hundreds of studies that there * 1

16 Even those in the business of selling tests, who might be ex

pected to ease the way for their use, concede the need for such

study. See Science Research Assoc., Inc., a subsidiary of IBM,

Business and Industrial Education Catalog 1968-69, at 4:

“A sound testing program is based on four critical steps:

1. Careful job analysis.

2. An analysis and assessment of essential job character

istics.

3. Selection of the test or tests.

4. Testing the tests.”

26

is commonly little or no relationship between test scores

and job performance. An eminent industrial psychologist,

Dr. Edwin Ghiselli of the University of California, re

cently reviewed all the available data on the predictive

power of standardized aptitude tests in an attempt to de

velop better testing practices. Dr. Ghiselli is a strong sup

porter of tests. Yet he was forced to conclude that in

trades and crafts aptitude tests “do not well predict suc

cess on the actual jobs,” 17 and that in industrial occupa

tions “the general picture is one of quite limited predictive

power.” 18 In many situations there is actually a negative

relationship between test scores and job success.19

What does this mean in practical terms? An example,

which is by no means unusual, is contained in a report of a

study performed in a large Southern aluminum plant.20 The

study showed that scores on the Wonderlic test had no re

lation whatsoever to job performance. Negroes were scor

ing only half as well as whites on the test, but there was no

difference between races in job performance ability. If the

test had been blindly used, Negroes would have been grossly

screened out without business need and contrary to the

interests of the employer. Other studies have shown, for

example, that the Wonderlic test is of no significant value

in predicting performance of ordnance factory workers or

radio assembly workers,21 and that there is a negative rela-

17 E. Ghiselli, The Validity of Occupational Aptitude Tests 51

(1966).

18 Id. at 57.

19 E.g., id. at 46.

20 Mitchell, Albright & McMurry, Biracial Validation of Selec

tion Procedures in a Large Southern Plant, in Proceedings of 76th

Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association,

Sept., 1968, reprinted in Appendix hereto at pp. 56-57.

21 Super & Crites, Appraising Vocational Fitness 106 (Rev. ed.

1962).

27

tionship between test scores and job performance (i . e low

scorers on the test do better on the job) for workers in the

printing and publishing industry22 and for workers in the

manufacture of finished lumber products and transporta

tion equipment.23 As to the Bennett, studies have shown,

for example, that test scores can be negatively related to

job success in occupations such as textile weaving24 * and jobs

in the manufacture of electrical equipment.26

These results should not be surprising. Aptitude tests

may be expected to predict future academic performance

rather well because academic grades are measured by per

formance on more tests. But industrial job performance

involves a range of skills and abilities entirely divorced

from a pristine test room setting. There is an understand

ably low correlation between test taking skills and job per

formance skills.

This is particularly true when the test is being given to

a mixed racial group. One of the basic assumptions under

lying tests is what might be called the “equal exposure”

assumption. A test measures how well a person has learned

various skills and information. To the extent an entire

group tested has had equal opportunity to learn those

skills and information, test scores may sometimes make a

reasonably useful prediction of performance on the job.

But when this equal exposure assumption is false—as it

surely is in the case of comparisons between Southern

Negroes and whites—the already shaky basis for test pre

22 B. Ghiselli, The Validity of Occupational Aptitude Tests 137

(1966).

23 Id. at 135, 148.

24 Id. at 132.

26 Id. at 147.

28

dictions is drastically undercut.26 For this reason, as Dr.

Barrett testified he found in his Ford Foundation study, a

test may predict differently for one racial group than it

does for another (R. 140a). Several other recent studies

have confirmed Dr. Barrett’s conclusions.27

Of course, tests are not always so poor at predicting.

In some cases tests may be reasonably useful. The point

is that predicting job performance on the basis of tests or

on other measures of educational background is a highly

precarious endeavor dependent on a myriad of factors.28

26 This point was made verv clearly by the court in Hobson v.

Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401, 484-485 (D. D. C. 1967) :

“A crucial assumption [in evaluating aptitude test scores] . . .

is that the individual is fairly comparable with the norming

group in terms of environmental background and psycho

logical make-up; to the extent the individual is not com

parable, the test score may reflect those differences rather than

innate differences . . .

“. . . For this reason, standard aptitude tests are most precise

and accurate in their measurements of innate ability when

given to white middle class students.

“When standard aptitude tests are given to low-income Negro

children, or disadvantaged children, however, the tests are less

precise and less accurate—so much so that test scores become

practically meaningless. Because of the impoverished circum

stances that characterize the disadvantaged child, it is virtually

impossible to tell whether the test score reflects lack of ability

—or simply lack of opportunity. . . .” (Emphasis added).

27 See, e.g., Lopez, Current Problems in Test Performance of Job

Applicants: 1, 19 Presonnel Pysch. 10-18 (1966) ; Lopez, Evaluat

ing the Whole Man, 2 The Long Island University Magazine 17-21

(1968) ; Ruda and Albright, Racial Differences on Selection In

struments Related to Subsequent Job Performance, 21 Personnel

Psych. 31-41 (1968).

28 See Ghiselli, The Generalization of Validity, 12 Personnel

Psychology 397-398, 400 (1959) :

“A confirmed pessimist at best, even I was surprised at the

variation in findings concerning a particular test applied to

workers on a particular job. We certainly never expect the

repetition of an investigation to give the same results as the

29

Because of the frequency with which test scores show little

or no relation to job performance, it cannot be assumed in

any particular case that a test is making a useful predic

tion without comprehensive supporting evidence based on

the employer’s own jobs and population. All standard tests

on test use insist on such evidence, known as a validity

study, as a prerequisite to using any particular test to deny

promotions or jobs.* 29 Even the manual for the Wonderlic

Test, upon which Duke relies, unequivocally states:

original. But we never anticipated them to be worlds apart.

Yet this appears to be the situation with test validities. . . .”

“. . . We start off by making the best guesses we ean as to which

tests are most likely to predict success and are not at all sur

prised when we are completely wrong.”

29 “Some adequate measure of validity is absolutely necessary be

fore the value of a test can really be known and before the

scores on the test can be said to have any meaning as predictors

of job success. . . . The use of unverified tests, whether through

innocence or intent, cannot be condoned. . . . For example, if

a test is known to measure some psychological ability, such as

ability to work with mechanical relations, and certain me

chanical performances are required in the performance of the

job, the test still cannot be considered valid until the scores

have been checked against some index of job success.” Ghiselli

and Brown, Personnel and Industrial Psychology 187-88

(1955);

“Tests must always be selected for the. particular purpose for

which they are to be used; even in similar situations, the same

test may not be appropriate . . . Tests which select super

visors well in one plant prove valueless in another. No list

of recommended tests can eliminate the necessity for carefully

choosing tests to suit each situation . . . No matter how com

plete the test author’s research, the person who is developing

a selection or classification program must, in the end, confirm

for himself the validity of the test in his particular situation.

. . . In most predictive uses of tests, the published validity

coefficient is no more than a hint as to whether the test is

relevant to the tester’s decision. He must validate the test in

his own school or factory . . . ” 1 Cronbach, Essentials of

Psychological Testing 86, 105, 119 (2d ed. 1960) ;

“It is of utmost importance that any tests that are used, for

employment purposes or otherwise be validated. . . . I t is only

30'

“the examination is not valuable unless it is carefully

used, and norms are established for each situation in

which it is to be applied. (Emphasis added).30

Insofar as a high school diploma requirement is used to

measure job performance abilities it is no better than a

test and probably much worse. There is so much variation

in the quality of high schools, the nature of the courses

taken, the grades in the courses and many other factors

that a high school diploma is a highly unreliable indicator.

While high school diploma requirements have not been

given the same extensive scientific study as tests, it should

be obvious that if a consistent and highly reliable measure

of educational background (such as a test) cannot well

measure job performance potential, an inconsistent and

unreliable measure of the same thing (such as a high school

diploma requirement) cannot do so.31 Many companies

when a test has been demonstrated to have an acceptable de

gree of validity that it can be used safely with reasonable as

surance that it will serve its intended purpose.”

̂ ̂ ̂ ^

“The point to be emphasized throughout this discussion is that

no one—whether he is an employment manager, a psychologist,

or anyone else—can predict with certainty which tests will be

desirable tests for placement on any particular job.” Tiffin

and McCormick, Industrial Psychology 119, 124 (5th ed.

1965) .

See also e.g., Ghiselli and Brown, supra, at 210; Ruch, Psy

chology and Life 67, 456-57 (5th ed. 1958) ; Siegel, Industrial

Psychology 122 (1962) ; Thorndike, Personnel Selection Tests

and Measurement Techniques 5-6 (1949) ; Freeman, Theory

and Practice of Psychological Testing 88 (3rd ed. 1962) ;

Lawshe and Balma, Principles of Personnel Testing (2nd ed.

1966) .

30 Wonderlic Personnel Test Manual 2 (1961).

31 A witness for Duke, Dr. Dannie Moffie, explained the signifi

cance of a high school diploma in measuring job performance abil

ities :

“Q. Would the High School education by itself tell you [whether

31

honestly interested in fair employment have decided, after

investigating the matter, that a high school diploma re

quirement is not worthwhile and should be dropped. This

group includes the First National City Bank, Metropolitan

Life Insurance Company, American Broadcasting Company

and the Chemical Bank New York Trust Company.32

It is sometimes suggested that a high school diploma

requirement is useful as a measure of motivation and per

severance rather than as a measure of learning. This may

he true in some situations involving the selection of new

employees and may sometimes justify use of the require

ment in such situations (assuming the discrimination in

herent in this measure of perseverance is adequately dealt

with). In this case, however, Duke has made it clear that

the requirement is being used as a measure of learning,

not motivation (R. 102a, 188a). This is necessarily so be

cause it would be foolish to attempt to use a high school

diploma requirement to assess the motivation and perse

verance of employees whose work habits have been ob

served for several years. This direct in-plant observation

enables a far better assessment than any externally based

standard.

an employee has the ability or trainability for a job at a

higher level] ?

A. [by Dr. Moffie] A High School education would merely

tell you that you have the necessary abilities as defined by

a High School education, and if the company feels that this

is required in these jobs, that’s all it would tell you.”

(R. 188a).

In other words, a high school education is a valid measure of

job potential only insofar as it can be shown that the abilities

“defined by a High School education” are required on the em

ployer’s jobs. This cannot be known without examining both the

jobs and the nature of a high school education in light of skills

needed on those jobs.

32 Hearings before the United States Equal Employment Oppor

tunity Commission on Discrimination in White Collar Employment,

New York City, Jan. 15-18, 1968, at 46-48, 99, 377, 466.

32

In view of the low validity and reliability of test and

education requirements in assessing job performance abili

ties, no such requirement that grossly prefers whites over

Negroes can be assumed to be based on business need unless

supported by proper study and evaluation. Absent such

study and evaluation, the use of these requirements con

stitutes an unjustified exclusion of Negroes in violation of

Title VII.

B. T he Legal Authorities Regarding Tests and Educational

R equirem ents.

An examination of Title VII leaves no doubt that racial

discrimination resulting from unnecessary educational or

test requirements was to be barred. The statute prohibits

any limitation or classification of employees:

“which would deprive or tend to deprive any individual

of employment opportunities or otherwise adversely

affect his status as an employee because of such indi

vidual’s race.” Section 703(a)(2), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2

(a)(2) (emphasis added).

In light of the racial characteristics on which they are

based, an unnecessary educational or test requirement

which screens out Negroes at three or more times the rate

of whites clearly tends to deprive or otherwise adversely

affect a Negro’s status.

The legislative history of the Act solidly reinforces this

conclusion. Title VII was motivated by a serious concern

for the waste of human potential resulting from the shock

ing conditions of high unemployment and low income

among Negroes.33 Congress realized this waste of an im

33 See, e.g., H.R. Rep. No. 570, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. 2-3 (1963);

H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. 138-41 (1963) (Concur

ring report of Congressman McCulloch and others); Hearings on

Equal Employment Opportunity before the General Subcomm. on

33

portant national asset was an economic wound damaging

the productivity of the United States, and that it was a

social wound producing festering slums and children des

tined to misery. Title VII was squarely aimed at ending

this waste of human potential by assuring that qualified

men could not be denied jobs for racial reasons. This goal

could not be accomplished if unnecessarily high job qualifi

cations related to race, such as those at Duke, wTere not out

lawed ; and Title VII therefore outlawed them.

Title VII has been so interpreted by the Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Commission. As the agency charged

with administration and implementation of the Act, the in

terpretations of the EEOC are entitled to the highest re

spect, especially when made shortly after passage of the

Act.34 The agency has the greatest familiarity with the

background and purpose of the law and can best appreciate

the overall impact of any interpretation. The EEOC has

consistently ruled that tests (including, specifically, the

Wonderlic test and the Bennett test) are unlawful,

“in the absence of evidence that the tests are properly

related to the jobs and have been properly vali

dated . . .” Decision of EEOC, Dec, 2, 1966, in CCH,

Employment Practices Guide, fT 17,304.53, reprinted in

Appendix hereto at pp. 51-52.

Labor of the House Comm, on Education & Labor, 88th Cong., 1st

Sess. passim (1963); Hearings on Equal Employment Opportunity

before the Subcomm. on Employment & Manpower of the Senate

Comm, on Labor & Public Welfare, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. passim

(1963).

34 See International Chem. Workers v. Planters Mfg. Co., 259 F.

Supp. 365, 366-67 (N.D. Miss. 1966); Norwegian Nitrogen Prods.

Co. v. United States, 288 U.S. 294, 315 (1933); Skidmore v. Swift,

323 U.S. 134, 137, 139-40 (1944) ; United States v. American

Trucking Associations, 310 U.S. 534 (1940); United States v. Jef

ferson County Board of Education, 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966),

aff’d on rehearing en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (1967); 1 Davis, Admin.

Law Treatise, §5.06 and cases cited (1959).

34

This policy has been amplified in the EEOC’s fully devel

oped “Guidelines on Employment Testing Procedures”

which clearly call for tests to be validated against job per

formance.35 The EEOC has ruled the same with regard to

educational requirements, i.e., that they must be related to

job performance. Decision of EEOC, Dec. 6 ,1966, in CCH,

Employment Practices Guide, If 17,304.55,36 reprinted in

Appendix hereto at pp. 53-55.

The EEOC’s position in this regard is supported by the

one Federal court (other than the District Court below)

to consider the question. In Dobbins v. IBEW, 58 Lab.

Cas. ff 9158 (S.D. Ohio 1968), Judge Hogan was confronted

with two tests, one given for entry into a union and the

other for entry into an apprenticeship program. He found

both tests to be “objectively fair” and “fairly graded.”

However, the union entry test was ruled unlawful because

not adequately related to job performance needs. Id. at

pp. 6624-25. The apprenticeship entry test was upheld be

cause it was designed by an expert consultant to fulfill the

precise needs of the program. Id. at p. 6629.

This interpretation is in accord with that of the Office

of Federal Contract Compliance (enforcer of the Presi

dent’s Executive Order prohibiting discrimination by gov

ernment contractors). The OFCC has recently promul

gated an order requiring an employer to produce empirical

data showing that tests and educational standards that dis- * 86

35 These guidelines are set out at R. 129b-136b. Duke has made

some point of the fact that these are “guidelines” and not manda

tory requirements. But this precatory status is only a reflection of

the EEOC’s lack of positive enforcement power, i.e., the EEOC

can do nothing more than issue “guidelines.” Its position on this

issue is firm.

86 See, in addition to the decisions cited in text, EEOC Release,

Nov. 2, 1968, in CHH Employment Practices Guide, If 8048.

35

proportionately screen out Negroes are correlated with job

performance at the employer’s plant. See Order on Valida

tion of Employment Tests by Contractors and Subcon

tractors, 33 Fed. Eeg. 14302, at §2(b), 10 (Sept. 24, 1968),

reprinted in Appendix hereto at pp. 58-61. Similar policies

have also been adopted by state fair employment agencies

in Colorado, Pennsylvania and New Jersey.37

C. T he E vidence Shelving a Lack o f Business Need fo r D uke’s

D iscrim inatory Transfer R equirem ents.

The crucial issue in this case is thus the business need

for the test and educational requirements used by Duke to

deny promotions at Dan River.

The best, and well nigh irrefutable, evidence of a lack of

business need for these requirements is Duke’s readiness

to permit present white employees to stay and be promoted

without meeting them (R. 102a-103a). This double standard

belies any claim that business necessity required Duke to

deny transfers to any of the fourteen appellants because of

a failure to meet the requirements. However, even if this