Gibson v. Jackson Brief of Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

April 14, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gibson v. Jackson Brief of Amicus Curiae, 1977. a0501b4d-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/85e0ae13-b678-4542-b6e2-975f9645460f/gibson-v-jackson-brief-of-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

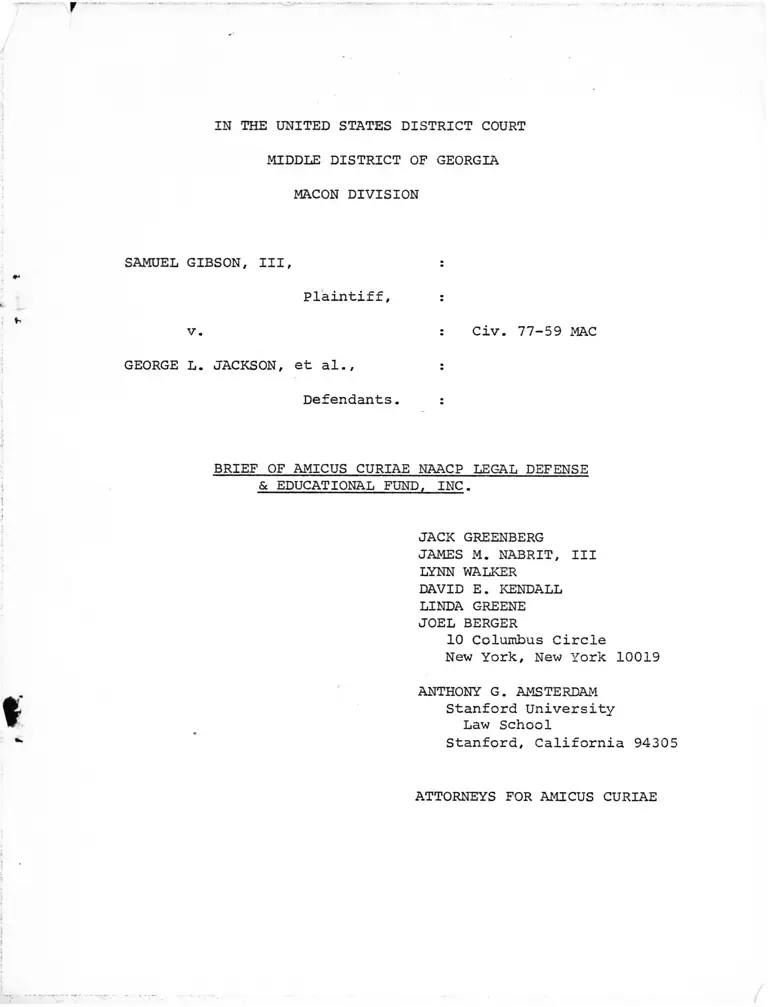

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SAMUEL

GEORGE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

MACON DIVISION

GIBSON, III, :

Plaintiff, :

V. : Civ. 77-59 MAC

L. JACKSON, et al., :

Defendants. :

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

& EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

LYNN WALKER

DAVID E. KENDALL

LINDA GREENE

JOEL BERGER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

Stanford University

Law School

Stanford, California 94305

ATTORNEYS FOR AMICUS CURIAE

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

MACON DIVISION

SAMUEL GIBSON, III,

Plaintiff,

v. Civ. 77-59 MAC

GEORGE L.JACKSON, et al., :

Defendants. :

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICUS

CURIAE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

by its undersigned counsel, submits the attached brief

amicus curiae in this case for the following reasons:

(1) The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., is a non-profit corporation chartered in New York

formed to assist black citizens in securing their constitu

tional rights by the prosecution of lawsuits; it has rep

resented on appeal numerous black defendants and indigent

defendants of all races who have received death sentences.

In 1967, the Legal Defense Fund undertook to represent all

condemned defendants in the United States, regardless of

race, for whom adequate representation could not

otherwise be found, and by June, 1972, represented

about 300 of the approximately 730 persons on Death Row

in the United States. Additionally, the Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc., provided consultative assistance

to attorneys representing a large number of other condemned

defendants. The Legal Defense Fund represented condemned

defendants on appeal in a number of cases in the Supreme

Court of the United States, e,g., Beecher v. Alabama,

408 U.S. 234 (1972); Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 U.S. 262 (1970);

and in State Supreme Courts, e,g., People v. Anderson,

6 Cal.2d 628, 493 F.2d 880, 100 Cal. Rptr. 152 (1972) as

these defendants challenged the constitutionality of their

death sentences, and it represented William Henry Furman

before the Supreme Court of the United States in the case

in which that Court declared capital punishment, as then

imposed, cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the

United States Constitution, Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S.

238 (1972). Most recently, the Legal Defense Fund rep

resented petitioners in three of the five capital punishment

cases which the Supreme Court of the United States decided

on July 2, 1976: Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280;

2

Roberts v. Louisiana, 428 U.S. 325; Jurek v. Texas,

428 U.S. 262. It filed briefs amicus curiae in Gregg

v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 and Proffitt v. Florida. 428

U.S. 242.

(2) The Legal Defense Fund has continued to

provide legal assistance to indigent condemned prisoners

of all races and is now involved as counsel in over one

hundred death cases. it currently represents a number

of indigent death-sentenced Georgia inmates who are at

various stages of habeas corpus proceedings, see, e,g.,

Ross v. Hopper, Tattnall County Super. Ct., No. 76-226(H.C.)

Spencer v. Hopper, Tattnall County Super. Ct. No. ______ ;

McCorguodale v. Stynchcombe, Ga. Sup. Ct. No. 32057; House

v. Stynchcombe, Ga. Sup. Ct. No. 32145.

(3) The Legal Defense Fund is supported by the

charitable contributions of private individuals and

foundations. In the past, it has sought to provide not

only counsel but investigative services and expert

witnesses for the indigent death-sentenced inmates whom

it represented. Because of the large number of cases

it is now involved in and because of its limited financial

3

and legal resources, the Legal Defense Fund will not

in the future be able to provide such assistance to all

the indigent condemned inmates who apply to it for aid.

(4) The present case thus presents civil rights

and civil liberties of great importance, and the Legal

Defense Fund therefore desires to present its views and

its analysis of certain legal precedents to the Court

in the hope that the Court might be assisted in the

resolution of the issues before it.

4

ARGUMENT

Plaintiff is a black, indigent Death Row inmate

who has filed a complaint under 42 U.S.C. §1983 in this

Court requesting the appointment of counsel and expert

investigative assistance in a state habeas corpus pro

ceeding. On May 14, 1975, when plaintiff was seventeen

years old, he was convicted and sentenced to die for

murder, and the Supreme Court of Georgia affirmed this

conviction, Gibson v. State, 236 Ga. 874, 226 S.E.2d 63

(1976). The Supreme Court of the United States denied

a timely petition for certiorari, Gibson v. Georgia,

45 U.S.L.W. 3400 (U.S., Nov. 29, 1976), and on February

28, 1977, the Superior Court of Jones County, Georgia,

set March 21, 1977, as the date for the execution of plaintiff's

death sentence.

On March 18, 1977, plaintiff filed a petition for

habeas corpus in the Superior Court of Butts County, Georgia,

and obtained a stay of execution. A motion for funds to

pay counsel, investigators, and expert witnesses was made

and denied by the trial court, and plaintiff subsequently

5

filed a §1983 complaint in this Court seeking injunctive

relief to compel the State of Georgia to provide him with

funds for counsel, investigators, and expert witnesses

or* in the alternative, to enjoin the State from executing

plaintiff until he had been afforded a full and fair hearing

on his federal constitutional claims. This brief amicus

curiae is submitted in support of plaintiff's request for

suitable relief to enable him to litigate adequately in

state court the federal constitutional claims alleged in

his petition for writ of habeas corpus.

There is a federal constitutional requirement, en

forceable through 42 U.S.C. §1983, that state post-convic

tion procedures be adequate for the full and fair adjudica

tion of federal constitutional claims. "It is the solemn

duty of . . . [state] courts, no less than federal ones,

to safeguard personal liberties and consider federal

claims in accord with federal law." Schneckloth v.

Bustamonte, 412 U.S. 218, 259 (1973)(concurring opinion

*/

of Mr. Justice Powell). The Supreme Court of the United

— / See Case v. Nebraska. 381 U.S. 336, 344-345 (1965)

(concurring opinion of Mr. Justice Brennan)(footnote

omitted):

"Our federal system entrusts the States

6

States has frequently reversed state court rulings

denying post-conviction relief -where the procedures

afforded by the State were inadequate to determine

fairly federal claims. In McNeil v. Culver, 365 U.S.

109 (1961), for example, a petitioner applied to the

Supreme Court of Florida for a writ of habeas corpus,

alleging facts and circumstances which if true supported

his contention that he was denied the assistance of counsel

at trial. The Florida Supreme Court issued a provisional

writ, but after considering the State's return and without

any hearing on petitioner's allegations, discharged the

writ and remanded the petitioner to custody. On review,

the United States Supreme Court reversed, holding that

since due process of law required petitioner to have the

jj[/ cont'd.

with primary responsibility for the ad

ministration of their criminal laws. The

Fourteenth Amendment and the Supremacy Clause

make requirements of fair and just procedures

an integral part of those laws, and state

procedures should ideally include adequate

administration of these guarantees as well.

If, by effective corrective processes, the

States assumed this burden . . . it would

assure not only that meritorious claims would

generally be vindicated without any need for

7

assistance of counsel if the facts alleged in his

petition were true, "the allegations themselves made

it incumbent on the Florida court to grant petitioner

a hearing and to determine what the true facts are."

365 U.S. at 117.

In Wilde v. Wyoming, 362 U.S. 607 (1960), a state

petitioner alleged in his petition for a writ of habeas

corpus that he had no counsel present when he pleaded

guilty to second-degree murder and that the.prosecutor

had suppressed testimony favorable to petitioner. Vacating

the judgment of the Wyoming Supreme Court, the United States

Supreme Court observed:

"It does not appear from the record

that an adequate hearing on these

allegations was held in District Court,

or any hearing of any nature in, or by

direction of, the [state] Supreme Court.

We find nothing in our examination of

cont'd.

federal court intervention, but that

nonmeritorious claims would be fully

ventilated, making easier the task of

the federal judge if the state prisoner

pursued his cause further."

8

of the record to justify the denial

on these allegations. The judgment

is therefore vacated and the case is

remanded for a hearing thereon."

362 U.S. at 607.

In Sublett v. Adams, 362 U.S. 143 (1960), a state

petitioner applied to the Supreme Court of West Virginia

for a writ of habeas corpus, charging that his confinement

was in violation of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. That court refused to grant the writ, without

either a hearing or a response from the State. On review,

the United States Supreme Court found that the "facts

alleged are such as to entitle petitioner to a hearing

. . . ", 362 U.S. at 143, and remanded the case to the

West Virginia Court for further proceedings. Accord:

Pennsylvania ex rel. Herman v. Claudy, 350 U.S. 116, 123

(1956); Pyle v . Kansas, 317 U.S. 213, 215-216 (1942); Cochran

v. Kansas, 316 U.S. 255, 257 (1942); Reynolds v. Cochran,

365 U.S. 525 (1961); Smith v. O'Grady, 312 U.S. 329 (1940);

Bushnell v. Ellis, 366 U.S. 418 (1961). "Petitioner carries

the burden in a collateral attack on a judgment. He must

prove his allegations but he is entitled to an opportunity."

Hawk v. Olson, 326 U.S. 271, 278 (1945).

9

The ability of a prisoner to establish his federal

constitutional claims in a state post-conviction pro

ceeding will normally depend on the evidence he can

muster and this, in turn, may depend on his economic

status. While the State is under no obligation to

equalize exactly the opportunities of indigent and non-

indigent prisoners to obtain collateral relief from

criminal convictions, a number of precedents during the

last twenty years establish that the Equal Protection

and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment do not

allow a State's criminal justice system to deprive indigent

defendants of basic procedural rights to obtain redress

from illegal or unconstitutional convictions simply

because of their indigence. The State must furnish

indigent defendants with "the basic tools of an adequate

defense or appeal, when those tools are available for

a price to other prisoners." Britt v. North Carolina,

404 U.S. 226, 227 (1971). The fundamental fact

that courts have recognized is that "[t]here can be no

equal justice where the kind of trial a man gets depends

10

on the amount of money he has." Griffin v. Illinois,

351 U.S. 12, 19 (1956). See Coppedge v. United States,

369 U.S. 438, 446-447 (1962). For "differences in

access to the instruments needed to vindicate legal

rights, when based upon the financial situation of the

defendant, are repugnant to the Constitution." Roberts

v. LaVallee, 389 U.S. 40, 42 (1967). Thus, counsel

must be appointed to represent indigent defendants at

felony trials, Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963);

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1931), and misdemeanor

trials, Argersinger v. Hamlin, 407 U.S. 25 (1972), and

on appeal, Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963).

A transcript for appeal may not be denied to a convicted

defendant simply because of his indigence, Griffin v .

Illinois, supra; Draper v. Washington, 372 U.S. 487 (1963)

Williams v. City of Oklahoma City, 395 U.S. 458; Mayer

v. City of Chicago, 404 U.S. 189 (1971); see also Rinaldi

v. Yeager, 384 U.S. 305 (1966). An indigent defendant

may not be forced to pay a filing fee as a prerequisite

for an appeal, Burns v. Ohio, 360 U.S. 252 (1959);

Douglas v. Green, 363 U.S. 192 (1960). A convicted

11

defendant may not be imprisoned simply because he is

unable to pay a fine, Williams v. Illinois, 360 U.S.

252 (1959); Tate v. Short, 399 U.S. 235 (1970). See

also Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371, 375-377,

V382-383 (1971). Cf. Britt v. North Carolina, supra.

The principle that the State cannot deny funda

mental procedural rights in the criminal justice system

simply because of economic status is not, however,

limited to trials and direct appeals: "for the indigent

as well as for the affluent prisoner, post-conviction

proceedings must be more than a formality." Johnson v .

Avery, 393 U.S. 483, 486 (1969). In Johnson, the

Supreme Court of the United States invalidated the

State of Tennessee's prison regulation prohibiting its

inmates from assisting one another in the filing of state

or federal post-conviction writs. The Court held that the

impact of the State's regulation was to unconstitutionally

"forbi[d] illiterate or poorly educated prisoners to file

habeas corpus petitions." 393 U.S. at 487. "Johnson v.

Avery makes it clear that some provision must be made to

insure that prisoners have the assistance necessary to

file petitions and complaints which will in fact be fully

*/ And see United States v. MacCollom, __U.S.__, 48 L.Ed.

2d 666, 674-675 (1976)(plurality opinion).

- 12 -

considered by the courts." Gilmore v. Lynch, 319 F. Supp.

105, 110 (N.D. Cal.), aff1d sub nom. Younger v. Gilmore,

404 U.S. 15 (1971). A federal district court has upheld

state prisoners' rights to an "expensive law library" in

order to ensure "meaningful access to courts," Hooks v .

Wainwright, 352 F. Supp. 163, 165, 167 (M.D. Fla. 1972),

after finding the inmates' due process rights violated

by the "inadequacy and insufficiency of the legal services

provided indigent inmates," 352 F. Supp. at 168. "To be

meaningful, the right of access to the courts must include

the means to frame and present legal issues and relevant

facts effectively for judicial consideration." Battle v.

Anderson, 376 F. Supp. 402, 426 (E.D. Okla. 1974). A

number of United States Supreme Court decisions hold that

access to state post-conviction procedures may not be

limited by economic barriers which have no rational

relationship to the merits of the legal claims sought

to be raised. See Eskridge v. Washington State Board

of Prison Terms and Paroles, 357 U.S. 214 (1958); Ross

v. Schneckloth, 357 U.S. 575 (1958); McCrary v. Indiana,

364 U.S. 277 (1960); Smith v. Bennett, 365 U.S. 708 (1961)

Lane v. Brown, 372 Y.S. 477 (1963); Long v. District Court

13

of Iowa, 385 U.S. 192 (1966); Gardner v. California,

393 U.S. 367 (1969). Although a number of different

procedural rights are involved in these cases, their

common denominator is that discriminations "based on

indigency alone," Lane v. Brown, supra, 372 U.S. at

1/

485, are impermissible.

In the present case, while the State of Georgia

has not denied plaintiff Gibson formal access to its

post-conviction remedies, by denying him funds for counsel

and for investigators (legal resources available to more

affluent defendants), it has rendered these proceedings

a "meaningless ritual," Douglas v. California, supra,

t/ The Court of Appeals for the Fif th Circuit has been

particularly vigilant to ensure that the rights of criminal

defendants are not sacrificed because of their indigence.

See, e.q., Bradford v. United States, 413 F.2d 467 (CA5 1969)

Hintz v. Beto, 379 F.2d 937 (CA5 1967); United States v.

Moudy, 462 F.2d 694 (CA5 1972); United States v. Hathcock,

441 F.2d 197 (CA5 1971); Welsh v. United States, 404 F.2d

414 (CA5 1968) ,* Bush v. McCollum, 231 F. Supp. 560 (N.D.

Tex. 1964), aff1d 344 F.2d 672 (CA5 1965); United States

v. Henderson, 525 F.2d 247, 251 (CA5 1975); United States

v. Theriault, 440 F.2d 713, 716-717 (CA5 1971)(Wisdom J.,

concurring); Rheuark v. Shaw, No. 76-1486 (CA5, Mar. 3,

1977) (this opinion is not yet reported and is reproduced

infra as Appendix A).

14

372 U.S. at 358. And this has occurred in a case where

the highest standard of regularity and fairness is

required, for at stake is plaintiff's very life, since

the State has exacted the "unique and irreversible penalty’

of death," Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280, 287

(1976)(plurality opinion)(footnote omitted). In death

cases, courts must be "particularly sensitive to see

that every safeguard is observed," Gregg v. Georgia,

428 U.S. 153, 187 (1976)(plurality opinion). For it

"cannot fairly be denied . . . that death is a punishment

different from all other sanctions in kind rather than

degree [or that] . . . the penalty of death is qualitatively

different from a sentence of imprisonment, however long.

Death, in its finality, differs more from life imprisonment

than a 100-year prison term differs from one of only a

year or two. Because of that qualitative difference,

there is a corresponding difference in the need for

reliability that death is the appropriate punishment

in a specific case."Woodson v. North Carolina, supra,

428 U.S. at 303-305 (plurality opinion)(footnote omitted).

Only a few weeks ago, the Supreme Court of the United

15

States explicitly recognized that "constitutional

developments" of the past three decades "require us

to scrutinize a State's capital sentencing procedures

more closely than was necessary in 1949:"

"Five members of the Court have now

expressly recognized that death is

a different kind of punishment than

any other which may be imposed in this

country. Gregg v. Georgia, __U.S.__,

No. 74-6257 (July 2, 1976), Slip op., at

31 (Opinion of Stewart, Powell and Stevens,

JJ.), see dissenting opinion of Marshall, J.;

Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238, 286-291

(Brennan, J., concurring), 306-310 (Stewart,

J., concurring), see 314-371 (Marshall, J.,

concurring). From the point of view of the

defendant, it is different in both its severity

and its finality. From the point of view of

society, the action of the sovereign in taking

the life of one of its citizens also differs

dramatically from any other legitimate state

action."

Gardner v. Florida, 45 U.S.L.W. 4275, 4277 (U.S., March

1/

22, 1977).

1/ See also Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45, 71 (1932);

Reid v. Covert, 354 U.S. 1, 77 (1957)(Harlan J., concurring);

Stein v. New York, 346 U.S. 156, 196 (1953); Williams v.

Georgia, 349 U.S. 375, 391 (1955); Andres v. United States,

333 U.S. 740, 752 (1948); Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238,

286-287 (1972)(Brennan J., concurring)("This Court, too,

almost always treats death cases as a class apart"); Griffin

v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12, 28 (1956)(Burton & Minton, JJ.,

dissenting)("It is the universal experience in the administra

tion of criminal justice that those charged with capital

offenses are granted special considerations"); United States

16

Ross v. Moffitt, 417 U.S. 600 (1974), is not a barrier

to granting the relief plaintiff seeks for three reasons.

First, Ross was not a capital case but rather involved the

question of whether counsel should be appointed to represent

a defendant convicted of check forgery on his second dis

cretionary) appeal within the State court system and on

certiorari to the Supreme Court of the United States.

A federal district court has distinguished Ross when an

indigent death-sentenced State prisoner sought to compel

the appoint of counsel to seek review of his conviction in

the Supreme Court of the United States on certiorari:

cont'd.

v. See, 505 F.2d 845, 853 fn.13 (CA9 1974)("In striking

a balance between the interests of the state and those of

the defendant, the courts have been admonished . . . to

give more weight to the fate of the person charged with

a capital crime"); United States ex rel. Russo v. Superior

Court, 483 F.2d 7, 12-13 (CA3 1973);McNeal v. Collier, 353

F. Supp. 485, 490 (N.D. Miss. 1972)("In a capital case,

special consideration must be given to the rights of the

accused."), rev1d on other grounds sub nom. McNeal v .

Ho Howe 11, 481 F .2d 1145 (CA5 1973) .

17

"Moffitt, however, faced only imprisonment;

Albert Lewis Carey, Jr., on the other hand,

may conceivably lost his very life, if his

petition for certiorari is not granted; and

the fate of the petitioner, as Justice Rehnguist

recognized, must inevitably be tied, at least

in part, to the quality and persuasiveness of

the petition."

Carey v. Garrison, C-C-75-342 (W.D. N.C. Nov. 11, 1975)

1/

(emphasis in original).

Second, Ross rests partially upon the assumption,

see Ross v. Moffitt, supra, 417 U.S. at 615,that appoint

ment of counsel for a second appeal is unnecessary because

there has already been a trial, which has produced a full

ventilation of issues relating to the defendant's guilt

and an appeal in which a brief, prepared by a trained

lawyer, has organized and researched legal errors which

may infect the conviction. However, in plaintiff Gibson's

case, there appears to be evidence that the counsel appointed

to represent him at trial and on appeal to the Georgia

Supreme Court was incompetent and ineffective. Thus, the

^_/ Carey v. Garrison is not reported and is reproduced

infra as Appendix B .

18

record made at trial and on appeal is likely to be

inadequate and unreliable for a proper determination of

plaintiff's constitutional claims. "Where the community

fails to supply — for those who cannot — the effort

and resources required for an adequate exploration of

[relevant factual] issue [s], the trial becomes a facade

of regularity for partial justice." Rollerson v. United

States, 343 F.2d 269, 276 (CADC 1964).

Finally, Ross involved the right to counsel on appeal

where there had already been one appeal. Plaintiff Gibson,

on the other hand, faces the terra incognita of an evi

dentiary hearing where new factual and legal issues must

be prepared and presented. As the Supreme Court of the

United States remarked in Powell v. Alabama, supra, 287

U.S. at 68-69, of an indigent defendant who faced a

capital trial without adequate counsel:

"The right to be heard would be, in

many cases, of little avail if it did not

comprehend the right to be heard by counsel.

Even the intelligent and educated layman has

small and sometimes no skill in the science

of law. If charged with crime, he is incapable,

generally, of determining for himself whether

the indictment is good or bad. He is unfamiliar

with the rules of evidence. Left without the

aid of counsel he may be put on trial without

a proper charge, and convicted upon incompetent

19

evidence, or evidence irrelevant to the

issue or otherwise inadmissible. He lacks

both the skill and knowledge adequately

to prepare his defense, even though he have

a perfect one. He requires the guiding hand

of counsel at every step in the proceedings

against him. Without it, though he be not

guilty, he faces the danger of conviction be

cause he does not know how to establish his

innocence. If that be true of men of in

telligence, how much more true is it of the

ignorant and illiterate, or those of feeble

intellect."

Neither is the existence of 28 U.S.C. §2254 a barrier

to granting the relief plaintiff seeks. The fact that

federal habeas corpus would ultimately be available to a

State prisoner deprived of a fair State post-conviction

hearing did not deter the Supreme Court of the United

States from reversing these denials of relief, see

cases discussed at pp. 7 - 9 , supra; indeed, in none

of these cases did the high Court even mention §2254 as

a relevant factor. In Smith v. Bennett, 365 U.S. 708 (1961),

however, the State of Iowa attempted to use such an

argument to defend its $4.00 filing fee required of

indigent habeas petitioners and its $3.00 appellate fee

required of indigent habeas petitioners denied relief and

seeking to appeal. The State contended that its filing

fees did not violate the rule of Griffin v. Illinois,

20

supra, and Burns v. Ohio, supra, because a prisoner

denied state habeas relief could always secure relief

in federal court under §2254. The Court rejected

this contention and voided the fees: " [w]hen an equivalent

right [to that of filing a habeas corpus petition under

§2254] is granted by a State, financial hurdles must not

be permitted to condition its exercise," 365 U.S. at 713.

The Court added that "the state remedy may offer review

of questions not involving federal rights and therefore

not raisable in federal habeas corpus." Ibid.

Likewise, the relief requested is not barred by

Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37 (1971), Huffman v. Pursue,

Ltd., 420 U.S. 592 (1975), Judice v. Vail, 45 U.S.L.W. 4269

(U.S., Mar. 22, 1977), and similar cases, for plaintiff's

§1983 suit is designed to effectuate rather than prohibit

State court proceedings. For one thing, the criminal

prosecution of plaintiff has already terminated. Moreover,

ensuring a full and comprehensive State habeas hearing will,

in fact, foster comity since such a hearing may make

unnecessary a later federal evidentiary hearing. Indeed,

one of the central purposes of the Georgia Legislature

when it drastically restructured the State1s habeas

corpus statutes in 1967 was to forestall litigation

21

in federal courts pursuant to Townsend v. Sain. 372 U.S.

293 (1963) and Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391 (1963), of

constitutional issues involving evidentiary questions

arising out of state criminal convictions. See Wilkes,

Georgia Habeas Corpus, 9 GA. L. REV. 13, 53 (1974). The

Preamble to the 1967 Act declared an intention to strengthen

the "state courts as instruments for the vindication of

constitutional rights" and to effectuate the "expansion

of state habeas corpus to include sharply-contested

issues of a factual nature", Section 1, Ga. L. 1967,

p.835.

Amicus curiae does not here suggest the precise

kind of relief which should be afforded to plaintiff

Gibson under §1983. The foregoing precedents clearly

indicate, however, that the State is under an obligation

to grant a full and fair post-conviction hearing to an

indigent death-sentenced inmate, if it vouchsafes such

procedural rights to more affluent prisoners. Moreover,

derelictions of this duty are remediable through §1983.

While it may be necessary to mandate the expenditure

22

of State funds, the rights of an indigent defendant

are not subject to a balancing test. in Mayer v. City

of Chicago, 404 U.S. 189 (1971), for example, the City

argued that it should not have to provide transcripts

for an appeal of right to indigent prisoners sentenced

to pay a fine. The Court flatly rejected this contention

"The city suggests that . . . [an indigent

defendant's] interest in a transcript is

outweighed by the State's fiscal and other

interests in not burdening the appellate

process. This argument misconceives the

principle of Griffin . . . Griffin does

not represent a balance between the needs of

the accused and the interests of society; its

principle is a flat prohibition against

pricing indigent defendants out of as

effective an appeal as would be available

to others able to pay their own way. The

invidiousness of the discrimination that

exists when criminal procedures are made

available only to those who can pay is not

erased by any differences in the sentences

that may be imposed. The State's fiscal

interest is, therefore, irrelevant."

404 U.S. at 196-197.

It may be the wisest course here to order the

appointment of counsel for plaintiff Gibson in the

State habeas action and then retain jurisdiction of the

suit to see what particular investigative resources are

necessary and not furnished in some way by the State.

The Georgia State Bar Association has recognized that

23

"[a] lawyer is often no better than the investigation

*/facilities or expert witnesses at his command." In view

of the apparently faulty record compiled during the trial

of this case, the Court may deem it appropriate to allow

counsel for plaintiff Gibson and the State to confer

and to ascertain what kind of factual investigation

* * /

is now appropriate. Whatever the precise relief granted,

ty Committee of the State Bar of Georgia on Compensated

Counsel, Assistance to the indigent Person Charged with

Crime, 2 GA. B.J. 197, 202 (1965).

**/ Gathering information to prepare for trial is a com

ponent of the effective assistance of counsel guaranteed

by the Sixth Amendment. Adams v, Illinois, 405 U.S. 278,

281-282 (1972); Coleman v. Alabama, 399 U.S. 1, 9 (1970).

See AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION PROJECT ON STANDARDS FOR

CRIMINAL JUSTICE, STANDARDS RELATING TO THE PROSECUTION

FUNCTION AND THE DEFENSE FUNCTION, Sec. 4,1 (Approved

Draft 1971) at 225-226:"It is the duty of every lawyer

to conduct a prompt investigation of the circumstances

of the case and explore all avenues leading to facts

relevant to guilt and degree of guilt or penalty."

The Commentary states flatly that "[f3 acts are the basis

of effective representation." Id. at 226. "[T]he Due Process

Clause . . . does speak to the balance of forces between

the accused and his accuser," Wardius v. Oregon, 412 U.S.

470, 474 (1973), and the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit has frequently recognized that the Government has

a duty "to ameliorate disparities between those who can

and those who cannot afford the [investitive] resource

sought." United States v. Henderson. 525 F.2d 247, 251

(CA5 1975). See, e.g., Mason v, Balcom, 531 F.2d 717, 724-

725 (CA5 1976); Windom v. Cook, 423. F.2d 721 (CA5 1970);

24

since "[t]he magnitude of a decision to take a human life

**/ cont'd.

Brooks v. Texas, 381 F.2d 619 (CA5 1967); Hintz v. Beto,

379 F.2d 937 (CA5 1967). "Effective counsel includes

familiarity of counsel with the case and an opportunity

to investigate it if necessary in order meaningfully to

advise the accused of his options." Calloway v. Powell,

393 F.2d 886, 888 (CA5 1968). " [T]he right to counsel

is meaningless if the lawyer is unable to make an effective

defense because he has no funds to provide the specialized

testimony which the case requires." Bush v. McCollum, 231

F. Supp. 560, 565 (N.D. Tex. 1964), aff'd 344 F.2d 672

(CA5 1965). See also Goldberg, Equality and Govern,mental

Action, 39 N.Y.U. L.REV. 202, 222 (1964):

"The right to counsel at trial and on

appeal may prove hollow if appointed counsel

is not armed with the tools of advocacy —

investigatory resources, expert witnesses,

subpoena, trial transcript. If the right

to counsel is to be given meaningful content,

and if our adversary process is to retain its

vitality, the appointed attorney, like the

retained attorney, must be permitted to per

form as an advocate . . . . If representation

is to be as effective for poor as for rich,

it follows that services necessary to make

this right effective must be supplied at

government expense to those unable to afford

them."

And see United States v. Johnson, 238 F.2d 565, 572

(CA2 1956) (Frank J., dissenting), rev1d 352 U.S. 565

(1957) :

"Furnishing [a poor defendant] with a lawyer

is not enough: The best lawyer in the world

cannot competently defend an accused person

if the lawyer cannot obtain existing evidence

crucial to the defense, e.g., if the defendant

cannot pay the fee of an investigator to find

25

is probably unparalleled in the human experience of

a member of a civilized society," Marion v. Beto, 434

F.2d 29, 32 (CA5 1970), it should be adequate to insure

that this indigent, death-sentenced inmate has a realistic

opportunity to present in his state habeas corpus proceed

ing the federal constitutional contentions which may save

his life.

cont’d.

a pivotal missing witness or a

necessary document, or that of an

expert accountant or mining engineer

or chemist. It might, indeed, reasonably

be argued that for the government to defray

such expenses, which the indigent accused

cannot meet, is essential to that assistance

by counsel which the Sixth Amendment guarantees."

26

RESPECTFULLY SUBMITTED

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

LYNN WALKER

DAVID E. KENDALL

LINDA GREENE

JOEL BERGER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

Stanford University

Law School

Stanford, California 94305

ATTORNEYS FOR AMICUS CURIAE

BY

DATE: April 14, 1977

27

Jack RHEUARK, Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

Bill SHAW, Clerk of Dallas County Court,

and the State of Texas, Defendants-Appellees.

No. 76-1486

United States Court of Appeals,

Fifth Circuit

March 3, 1977.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Texas.

Before MORGAN and HILL, Circuit Judges, and

NOEL,* District Judge.

JAMES C. HILL, Circuit Judge:

The issue in this case is whether a prisoner1s suit

for damages and injunctive relief against a state court

clerk and court stenographer for their alleged failure

to forward a state trial court transcript to the state

appellate court is in the nature of a civil rights suit

or a habeas corpus petition. Since we conclude that the

action is in the nature of a civil rights suit, we reverse

the dismissal by the district court and remand for further

proceedings.

Appellant, Jack Rheuark, filed a complaint in the district

court seeking injunctive and monetary relief against the clerk

of the Dallas County Court and the court reporter pursuant to

42 U.S.C.A. § 1983. Appellant was convicted of armed robbery

in a Texas state court and sentenced on February 10, 1975. His

attorney promptly filed a notice of appeal to the Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals. The state trial court then ordered that the

transcript of the trial he prepared at state expense. Approximately

twelve months thereafter, appellant instituted the instant

* Senior District Judge for the Southern District of Texas,

sitting by designation.

proceeding against the court clerk and the court

stenographer alleging that they were unreasonably

delaying the preparation and transmittal of his state

trial court records because of his indigent status.

Appellant contends that the actions of the defendants

discriminate against him and deny him equal access to the

appellate process.

The district court dismissed the complaint. It

concluded that appellant's proper remedy was a habeas

petition since he was challenging his physical imprison

ment. This appeal was then perfected.

Subsequent to the dismissal, appellant filed a habeas

petition in the district court, alleging speedy trial

violations and other constitutional errors in his Texas

robbery trial. The district court denied relief on the

basis that appellant's state appeal was pending and, thus,

he had failed to exhaust his state remedies.

On appeal from the dismissal of his habeas petition, this

court reversed.Rheuark v. Wade, 540 F.2d 1282 (5th Cir. 1976).

Noting that the district court took no notice of appellant's

allegation that fifteen months of unexcused delay in preparing

a transcript had rendered his state remedies practically unavail

able, we remanded the case to the district court "with instruc

tions to determine if the delay in preparing a transcript of

[appellant's] state trial has been justifiable." Id. at 1283.

Thus, after two years, two district court cases, and now two

appellate decisions, appellant remains without a transcript

ordered furnished to him by the state court two years ago,

and which he must have in order to prosecute his appeal. In

addition, appellant has made a variety of requests directed

to the Texas state courts to no avail.

Suits against state court clerks are not particularly uncommon

in this circuit and have uniformly been considered civil rights

actions. The most analogous case to the one sub judice is Qualls

v. Shaw, 538 F.2d 318 (5th Cir. 1976). In Qualls, a state prisoner,

preparatory to filing a motion for collateral relief, requested

of the court clerk the cost of sending him copies of records of

another similar lawsuit and of the grand jury lists for 1970, 1971

and 1972. The request was not acknowledged. The prisoner alleged

that the records he sought were regularly made available

to others. He sued for monetary relief and requested an

order directing the clerk to provide the information re

quested. The district court dismissed the complaint as in

the nature of habeas corpus. In reversing, this court said:

The district court erred in its analysis of

appellant's complaint. Preiser v. Rodriquez,

411 U.S. 475, 93 S.Ct. 1827, 36 L.Ed.2d 439 (1973)

provides that a state inmate may not utilize the

civil rights act to challenge his conviction, thus

bypassing habeas corpus procedures and the requirement

that he exhaust state remedies. In this case, the

appellant is not challenging his conviction and he is

not seeking his release from custody. He is claiming

that he has been denied access to records which are

are made available to others and has been subjected

to discriminatory treatment. Were he to prevail in this

action the court's opinion would not impinge in any

manner on the validity of his criminal conviction, and

therefore habeas corpus is not an appropriate remedy and

the district court's reliance on Preiser is misplaced.

Id. at 319.

See also Hill v. Johnson, 539 F.2d 439 (5th Cir. 1976);

Carter v. Thomas, 527 F.2d 1332 (5th Cir. 1976); Carter

v. Hardy, 526 F.2d 314 (5th Cir. 1976).

Also relevant to our inquiry in the instant case, the inmates

in Carter v. Thomas, supra, alleged that the procedure utilized

by the court with regard to in forma pauperis petitions took

months and sometimes more than a year to complete. In finding

that the complaint stated a claim for which relief could be

granted, this court stated:

But the fact that some delay is inherent in a process

does not provide constitutional immunity for extreme

and unreasonable delays. Plaintiffs have alleged

instances of twenty-one month intervals between sub

mission of papers to the court and filing of the com

plaint. We have no way of knowing whether this allega

tion is true or, if true, whether such delay is highly

atypical or is subject to reasonable explanation. We

hold only that this complairt states a claim upon which

relief may be granted. Differences of this magnitude

in treatment accorded indigents and non-indigents

cannot be brushed away. They must be scrutinized

and either justified or ended, (citations omitted)

527 F .2d at 1333.

Of course, the particular factual situation of this case

is dissimilar in some respects. The controversy in this case

is much more intertwined with the administration of the state

appellate courts. However appellant does not ask for any relief

from his sentence in this action, nor does he ask that the federal

court order him released from confinement or modify, in any respect,

the conditions of his confinement. The only possible effect that

this action might have upon appellant's confinement would be that,

if he can obtain the transcript to appeal, and if his appeal should

be successful, he would escape confinement on the state sentence.

However, he would not do so by order of this court, but as a result

of a decision obtained from the appellate courts of the State of

Texas. This case was cognizable as a 1983 suit. It should have

been filed, served, and tried.

In sum, the history of this case demonstrates the plight all

too often encountered by pro se litigants. The appellant in this

case has been doing his dead-level best to obtain the transcript

of his trial so that he may be afforded the opportunity of appeal

ing his case. Unfortunately, he has repeatedly had to invoke the

federal judicial system in his-effort to resolve a rather simple

s ituation that should have been handled promptly and efficiently

in the state courts. The inordinate delay evident in this case

should have been corrected without the necessity of "making a

federal case out of it."

REVERSED AND REMANDED.

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

Charlotte Division

C-C-75-342

ALBERT LEWIS CAREY, JR., Petitioner, )

)

-VS- ) ORDER

)

SAM P. GARRISON, Warden, Central )

Prison, and the STATE OF NORTH )

CAROLINA, )

Respondents. )

Albert Lewis Carey, Jr., has presented a'Petition for

Appointment of Counsel." He was convicted of murder in Mecklenburg

County, North Carolina, and was sentenced to death. The conviction

was affirmed October 7, 1975, by a divided North Carolina Supreme

Court. Carey is now on death row at North Carolina Central Prison,

Raleigh, North Carolina.

Petitioner was scheduled to be executed Friday, October 24,

1975, but his state court counsel, Mr. John H. Hasty, has informed

the court that Chief Justice Sharp, of the North Carolina Supreme

Court, ordered Carey's execution stayed for ninety days, to allow

him to seek certiorari in the United States Supreme Court.

Carey asks this court to appoint counsel to represent him in

his petition for certiorari. Mr. Hasty informs the court that the

state court has refused to provide counsel at this stage. Time is

of the essence, because under Supreme Court Rule 22, § 1, the petition,

or a request for an extension of time, must be filed in the Supreme

Court by January -5, 1976, ninety days after judgment was finally

entered against Carey.

Mr. Carey's petition really fits no form, but it is a sworn

petition, and it alleges indigency; it may properly be treated as

a petition for writ of habeas corpus. So construed, the petition

is read to allege that Carey is confined in violation of the Sixth

Amendment, because the state has failed to provide counsel for his

certiorari petition.

Ross v. Moffitt, 417 U.S. 600 (1974), must be reckoned with.

Moffitt had been convicted of forgery, in Mecklenburg and Guilford

Counties, North Carolina. In this court, he sought appointment of

counsel to represent him in a certiorari petition to the North

Carolina Supreme Court, and in the Middle District of North Carolina,

he sought appoint of counsel to seek certiorari to the United States

Supreme Court. Both district courts denied relief, based on existing

cases.

The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed both decisions

in Moffitt v. Ross, 483 F.2d 650 (4th Cir. 1973). That court

remanded for determination of the prima facie merit of Moffitt's

constitutional claims of error in his trial, with instructions to

grant Moffitt a writ of habeas corpus if (1) the claims were not

frivolous, and (2) the state continued to refuse to provide counsel.

Judge Haynsworth, writing for a unanimous panel, concluded

that Douglas v, California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963), required the state

to appoint counsel for Moffitt.

The United States Supreme Court reversed, in a six to three

decision written by Mr. Justice Rehnquist. He gave two reasons

for the decision. First, he concluded that Douglas did not require

the state to appoint counsel for Moffitt's certiorari petitions.

He distinguished Douglas, because it involved review as a matter

of right, and then said:

"This is not to say, of course, that a skilled

lawyer, particularly ore trained in the somewhat

arcane art of preparing petitions for discretionary

review, would not prove helpful to any litigant able

to employ him. An indigent defendant seeking review

in the supreme Court of North Carolina is therefore

somewhat handicapped in comparison with a wealthy

defendant who has counsel assisting him in every

conceivable manner at every stage in the proceedings

But both the opportunity to have counsel prepare an

initial brief in the Court of Appeals and the nature

of discretionary review in the Supreme Court of North

Carolina make this relative handicap far less than the

handicap borne by the indigent defendant denied counsel

on his initial appeal as of right in Douglas. And the

fact that a particular service might be of benefit

to an indigent defendant does not mean that the service

is constitutionally required. The duty of the State

under our cases is not to duplicate the legal arsenal

that may be privately retained by a criminal defendant

in a continuing effort to reverse his cmviction, but

only to assure the indigent defendant an adequate oppor

tunity to present his claims fairly in the context of the

State's appellate process. We think respondent was given

that opportunity under the existing North Carolina system."

(Emphasis added.) P. 616.

Of course this part of the discussion dealt with certiorari to

the North Carolina Supreme Court, but the opinion goes on to

hold this reasoning equally applicable to certiorari to the

United States Supreme Court.

The above-quoted language indicates that the Supreme Court

essentially reviewed all of the facts surrounding Moffitt's

conviction and appeal, and concluded that the handicap suffered

was not sufficient to raise equal protection problems.

Moffitt, however, faced only imprisonment; Albert Lewis

Carey, Jr., on the other hand, may conceivably lose his very

life, if his petition for certiorari is not granted; and the fate

the petitioner, as Justice Rehnguist recognized, must inevitably

be tied, at least in part, to the quality and persuasiveness of

the petition.

Where a man's life is at stake, I am not prepared to

concede that the law in Moffitt, the case of a small time forger,

should apply.

The second reason given for reversal in Moffitt was that

if any duty existed, it was the duty of the federal government

to provide counsel to represent Moffitt in his Supreme Court

petition, because he was seeking relief in a federal court, not

relief provided by the state. The court said it could not place

a burden on stateswhich it refused to place upon itself, and

cited three instances in which it had refused to appoint counsel

for certiorari petitioners. But the cases cited are all one

sentence orders and give no hint that they might have been

capital cases. So again, I am not prepared to say that the

United States Supreme Court would deny counsel to Carey, who

is sentenced to die.

Moreover, the burden of supplying counsel is properly the

burden of the state, because the state is the power which seeks

to deprive Carey of his life, and it seeks to do so without fulfilling

its cbligation under the Douglas view of the Sixth Amendment.

Morgan v. Yancey County Department of Corrections, No.

74-1453, decided by the Fourth Circuit on October 2, 1975, does not

compel a different result, because it, like Moffitt, did not involve

a capital crime.

IT IS THEREFORE ORDERED:

1. That the petition be filed in forma pauperis.

2. That the Clerk mail to Carey a form petition for writ

of habeas corpus.

3. That Carey fill out the form, sign it, and swear before

a notary public to the accuracy of the allegations in it, and

return it to the court not later than December 1, 1975, so the

court may have all of the facts before ruling.

4. That respondents, by December 10, 1975, answer the

allegations of Carey's petition, and show cause why a writ of habeas

corpus should not issue if the state is unwilling to provide counsel.

This the 11th day of November, 1975.

[s] James B. McMillan

United States District Judge