Katzenbach v. McClung Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Katzenbach v. McClung Brief Amicus Curiae, 1964. ba28fa9c-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/861a2c71-7e00-4966-bf33-568f9b389164/katzenbach-v-mcclung-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

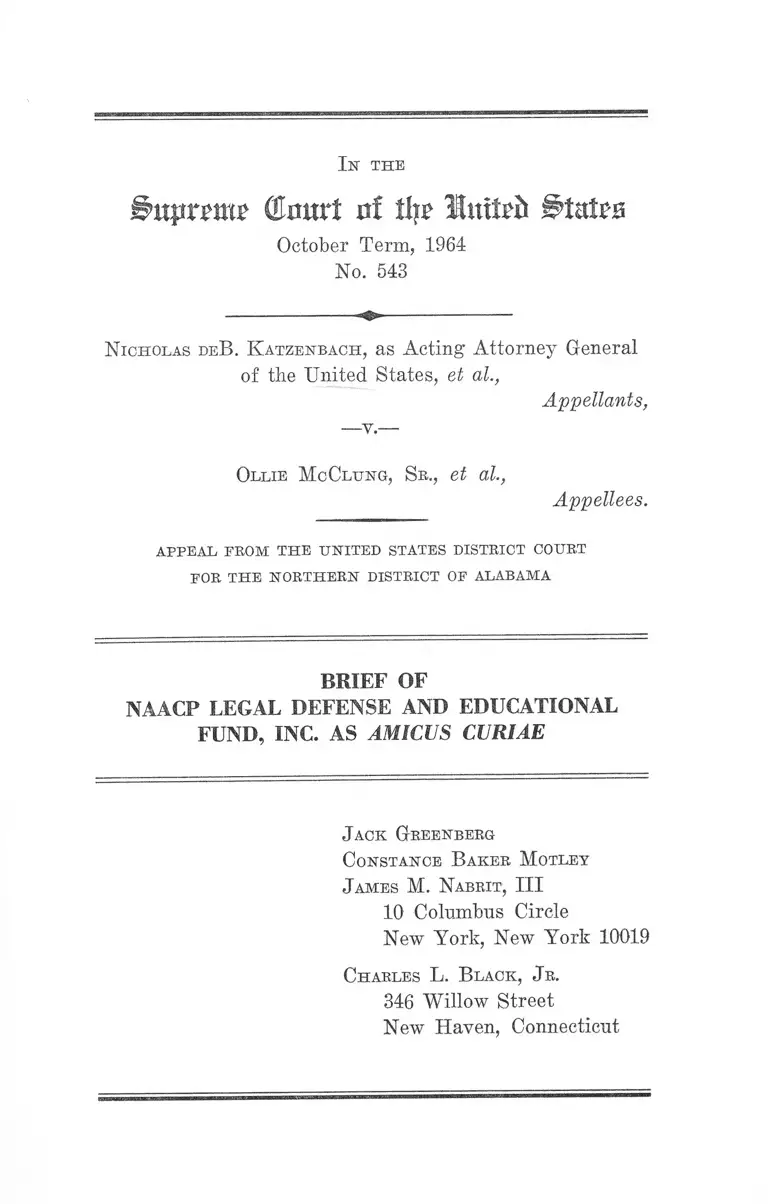

I n t h e

Ihiprm? CEnurt &t tl|? lu t!^ States

October Term, 1964

No. 543

N ich o la s deB . K a tzen b a c h , as Acting Attorney General

of the United States, et al.,

Appellants,

-v.-

Ol l ie M cC l u n g , Sb., et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OE ALABAMA

BRIEF OF

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC. AS AMICUS CURIAE

J ack G reen berg

C o n sta n ce B a k er M otley

J am es M . N abrit , III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

C h a r les L. B la c k , J r.

346 Willow Street

New Haven, Connecticut

I N D E X

PAGE

A r g u m e n t ................................................................................................ 1

Introduction .......... ....................... -................................. 1

I. Appellees’ Restaurant Is a Place of Public

Accommodation Within the Meaning of Sec

tion 201 of the Civil Eights Act of 1964 Reason

ably Construed With Appropriate Regard for

the Purposes and Constitutional Power of

Congress ............................................................. 4

A. Ollie’s Barbecue Offers to Serve Interstate

Travelers Within the Meaning of §201 (c) (2) 6

B. There Is No Proof That Ollie’s Barbecue

Does Not Actually “Serve . . . Interstate

Travelers” ; the Record Tends to Show the

Contrary ........................................................ 12

C. A Substantial Portion of the Food Served

by Ollie’s Barbecue Has Moved in Commerce

Within the Meaning of Section 201(c) (2) .... 14

D. As There Was No Evidence Upon Which

It Might Be Decided Whether Discrimina

tion at Appellees’ Business Was Supported

by State Action Within the Meaning of

§201(d), the Appellee Had No Standing to

Obtain, and the Trial Court No Equity

Jurisdiction to Grant, an Injunction Em

bracing This Provision .............................. 15

E. The Suggested Interpretation Indicated in

This Brief Would Enable the Various Parts

of the Law to Function in a Complementary

Manner to Effectuate the Congressional

Purpose .......................................................... 16

XI

page

II. The Power of Congress to Regulate Commerce

Among the States Supports Title II of the Civil

Rights Act ......................................................... 19

III. Title II Does Not Offend Any Other Constitu

tional Provisions .............................................. 26

A. A Requirement That Restaurateurs Open

to the Public Provide Service Without

Racial Discrimination Does Not Violate the

Fifth Amendment Due Process Clause ...... 26

B. The Thirteenth Amendment Is No Bar to

the Act .......................................................... 27

C. The Tenth Amendment Does Not Invalidate

Title I I ........................................................... 28

T able oe C ases

Cases:

American Communications Assn. v. Douds, 339 U. S.

382 ........................................... .................................... 22

Arver v. United States, 245 U. S. 366 ............................ 28

Bailey v. Patterson, 368 U. S. 346 ................................ 16

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1961) .... 17

Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 28 .......... 27

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454 .......... ............ ..11, 23, 27

Brown Holding Co. v. Feldman, 256 U. S. 170.............. 28

Brown v. Maryland, 25 U. S. (12 Wheat.) 419 .......... 28

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715 27

Caminetti v. United States, 242 U. S. 470 ................. 24

Champion v. Ames, 188 U. S. 321 ................... ............ 23

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 ..................... ..............16, 27

Colorado Anti-Discrimination Com. v. Continental Air

Lines, 372 U. S. 714 .................................................. 27

District of Columbia v. John E. Thompson Co., 346

U. S. 100...................................................................... 27

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160 .......................... 22

Georgia v. United States, 201 F. Supp. 813 (N. D. Ga.

1961), aff’d 371 U. S. 9 ........ ...................................... 17

Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U. S. (9 Wheat.) 1 ....2,19,20,21,28

Gloucester Ferry Co. v. Pennsylvania, 114 U. S. 196 .... 22

Gober v. Birmingham, 373 U. S. 374 ............................ 15,16

Hammer v. Dagenhart, 247 U. S. 251............................ 23

Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States, No. 515,

Oct. Term, 1964 ........... ....... ........... ..... ........... .......... 25

Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816 .................. 27

Hoke v. United States, 227 U. S. 308 ............................ 24

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267 ........................ 15,16

McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 IT. S. (4 Wheat.) 316.......... 2, 28

McDermott v. Wisconsin, 228 U. S. 15 ........... 24

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 8 0 ......................... 27

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 ................................ 23

N. L. E. B. v. Fainblatt, 306 U. S. 601 ......................... 22, 25

N. L. R. B. v, Jones & Laughlin Steel Co., 301 U. S. 1 24, 26

N. L. E. B. v. Reliance Fuel Corp., 371 U. S. 234 .......... 2, 22

Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 ......................... 27

Railway Mail Assoc, v. Corsi, 326 U. S. 88..................... 27

Robinson v. Florida, 378 U. S. 153 ............................ 15,16

Slaughterhouse Cases, 83 U. S. (18 Wall.) 3 6 .............. 28

Swift & Co. v. United States, 196 U. S. 375 ................. 3

Ill

PAGE

Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 ................................3, 27

United States v. Carotene Products, 304 U. S. 144...... 20

United States v. Darby, 312 U. S. 100 —.21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 28

United States v. E. C. Knight Co., 156 U. S. 1 .............. 3

United States v. Employing Plasterers Assn., 347 U. S.

186 ............................................................................... 25

United States v. Ferger, 250 U. S. 199......................... 22

United States v. Rock Royal Co-Operative, 307 U. S.

533 ............................................................................... 24

United States v. Sullivan, 332 U. S. 689 ................... 24, 25

United States v. Women’s Sportswear Mfg. Assn., 336

U. S. 460 .................................. 25

Wickard v. Filburn, 317 U. S. I l l .................................. 22

Willis v. Pickrick,----- F. Supp.------ (N. D. Ga., No.

9028; September 4, 1964) ........ 3

Other Authorities:

Hearings Before Joint Subcommittee No. 5 of the

House Committee on the Judiciary, 88th Cong., 1st

Sess., ser. 4, pt. 1 (1963) ...........................................7-8,18

Minority Report, H. R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st

Sess. 79 (1963) ........................................................... 8

110 Cong. Rec. 1456 (Daily Ed., Jan. 31,1964)...... 9

110 Cong. Rec. 1901 (Daily Ed., Feb. 5, 1964) .... 9

110 Cong. Rec. 7177 (Daily Ed., Apr. 9, 1964) ............. 11

iv

PAGE

I n t h e

gnifiruittu (fliinrt nf tip United States

October Term, 1964

No. 543

N ich o la s deB . K a tzen b a c h , as Acting Attorney General

of the United States, et al.,

Appellants,

----Y.----

Ollie M cClung , Sr ., et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

POE THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OP ALABAMA

BRIEF OF

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC. AS AMICUS CURIAE

ARGUMENT

Introduction

Proponents and opponents alike agree that the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 is one of the most significant legislative

enactments in our history. Both Houses of Congress sub

jected it to lengthy and exhaustive hearings, debate, and

controversy, and finally passed it by large majorities. Much

of the lengthy consideration and debate focused on the part

of the Act involved in this case, Title II providing for “In

junctive Relief Against Discrimination in Places of Public

Accommodation.” We think it appropriate to say of this

law, as Chief Justice Marshall said of the bill incorporating

the bank of the United States, that i t :

2

. . . did not steal upon an unsuspecting legislature,

and pass unobserved. Its principle was completely

understood, and was opposed with equal zeal and

ability. After being resisted, . . . in the fair and

open field of debate . . . with as much persevering-

talents as any measure has ever experienced, and

being supported by arguments which convinced minds

as pure and intelligent as this country can boast, it

became a law. . . . It would require no ordinary share

of intrepidity to assert that a measure adopted under

these circumstances was a bold and plain usurpation,

to which the constitution gave no countenance.1

Yet, appellees, with extraordinary intrepidity, have sum

moned arguments rejected by Congress and have persuaded

a Court of the United States that the public accommoda

tions law is an exercise of “naked power” by the Congress

unsanctioned by the Constitution.

The importance of such a case is manifest. The desira

bility of promptly determining this issue has been recog

nized. We submit below that Congressional power to enact

this law under the power to “regulate Commerce . . . among

the several States” can be sustained by settled and conven

tional constitutional doctrine reflected in decisions as old

as Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U. S. (9 Wheat.) 1, and as recent as

N. L. R. B. v. Reliance Fuel Corp., 371 U. S. 234. Indeed, in

light of the precedents, the commerce issue cannot be re

garded as difficult or close.

We shall also discuss a more subtle danger lurking behind

appellees’ frontal, and perhaps premature,2 attack on the

1 McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U. S. (4 Wheat.) 316, 401.

2 We recognize that the issues of justiciability and equity juris

diction raised by the United States involve substantial questions

which may well necessitate reversal of the judgment below inde

pendent of the constitutional and statutory issues. Because of time

3

Civil Eights Act. This danger is that the force and ef

fectiveness of the Act may be weakened, even temporarily,

by a restrictive construction.3 Compare the “Sugar Trust

Case,” United States v. E. C. Knight Co., 156 U. S. 1, with

Swift <& Co. v. United States, 196 U. S. 375. Even an inad

vertent or implied restriction on the coverage of the Act

could cripple it immeasurably, by undermining the pattern

of voluntary compliance which has emerged in many locali

ties as well as by its effect on enforcement proceedings in

lower courts. This danger is acute here because neither the

United States nor any person aggrieved by discrimination

has made an effort to present facts establishing that ap

pellees’ restaurant is covered by the Civil Eights Act.4

The only evidence of coverage was presented by the appel

lees themselves, and they naturally had no interest in de

veloping any facts pertaining to coverage which would

undercut their constitutional theories. Despite this, it does

limitations this brief is limited to a discussion of the paramount

issues of constitutionality and interpretation.

There is a substantial public interest in prompt resolution of

the issues of constitutionality, and since the Act is clearly valid

under settled principles, there is no compelling reason for post

poning decision. Cf. Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350. Further

guidance to the lower courts on questions of interpretation of the

Act—again where the congressional purpose is manifest—is also

plainly desirable and appropriate notwithstanding the procedural

difficulties in this case. Rules of self-restraint applicable to de

cisions of constitutional issues do not apply with equal force to

statutory interpretation, because Congress can rectify any error of

interpretation.

3 Already some judges have construed the Act so restrictively

as to remove most restaurants from coverage. See the special con

curring opinion of Circuit Judge Bell with Judge Hooper in

Willis v. PickricJc, ——- F. Supp.----- (N. D. 6a., No. 9028; Sep

tember 4, 1964) ; earlier proceedings reported at 231 F. Supp. 396.

4 Consistent with its view that there was no equity jurisdiction

and no justiciable controversy, the United States made no investi

gation of this restaurant, and presented no witnesses or exhibits.

4

plainly appear from the record that “Ollie’s Barbecue”

is a “place of public accommodation” as defined in Section

201 of the Act. The case properly presents an occasion

for application and interpretation of the Act.

I.

Appellees’ Restaurant Is a Place of Public Accommo

dation Within the Meaning of Section 201 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 Reasonably Construed With Appro

priate Regard for the Purposes and Constitutional

Power of Congress.

All parties agree, and the evidence is conclusive, that

Ollie’s Barbecue is a “restaurant . . . principally engaged

in selling food for consumption on the premises,” and is one

of the types of facilities mentioned in Section 201(b)(2)

of the Act. Equally undisputed, this restaurant “serves the

public” (§201(b)). No one contends that the restaurant is

excepted from the Act as a “bona fide private club or other

establishment not open to the public” (§201(e)). There is

clear proof that appellees deny to Negroes (including cus

tomers, potential customers and employees) “the full and

equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, privileges,

advantages, and accommodations” of the establishment by

discrimination and segregation on the ground of race and

color.5

5 Both appellees testified to their policy of refusing Negroes

food service except at a take-out counter for Negroes (Tr. 34, 60,

et seq.). They mentioned several occasions when Negroes had been

denied table or counter service on racial grounds (Tr. 43, 60).

Ollie Me Clung, Sr. acknowledged that Negro employees were segre

gated from white employees when eating on the premises (Tr. 57).

(The reference in §201 (a) to “all persons” is surely broad enough

to cover employees as ŵ ell as customers.)

5

A restaurant is a place of public accommodation covered

by the Act “if its operations affect commerce, or if dis

crimination or segregation by it is supported by State

action” (§201(b)). In Section 201(c)(2) the Act provides

that the operations of a restaurant “affect commerce with

in the meaning of this title” if “it serves or offers to serve

interstate travelers or a substantial portion of the food

which it serves, or gasoline or other products which it sells,

has moved in commerce.” Section 201(d) provides criteria

for determining whether discrimination or segregation by

an establishment is “supported by State action within the

meaning of this title.”

Appellees argued below that their restaurant was covered,

but only by virtue of §201 (c)(2) relating to the movement

in commerce of food served. The District Court agreed,

stating that the issues “require our consideration of only

that portion of the statute relating to restaurants which

serve food, ‘a substantial portion’ of which ‘has moved in

commerce.’ ” The court held that provision unconstitu

tional. Also, the Court undertook to cast doubt upon the

validity of the alternative criterion in §201(c)(2) provid

ing coverage of a restaurant if “it serves or offers to serve

interstate travelers,” by observing:

No case has been called to our attention, we have

found none, which has held that the national govern

ment has the power to control the conduct of people

on the local level because they may happen to trade

sporadically with persons who may be traveling in

interstate commerce. To the contrary, see 'Williams

v. Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F. 2d 845 (4th

Cir. 1959); Elizabeth Hospital, Inc. v. Richardson, 269

F. 2d 167 (8th Cir. 1959); United States v. Yellow Cab

Co., 332 IT. S. 218 (1947).

6

Whatever the limitations of its opinion, the order of

the District Court enjoined the Attorney General from

enforcing Title II, as a whole, against appellees. It is sub

mitted below that Ollie’s Barbecue is a place of public ac

commodation within the Act in that it “offers to serve inter

state travelers.” Next, it will be demonstrated that appel

lees failed to establish that they did not actually “serve . . .

interstate travelers” and that the most logical inference

from the record is that they do and are covered by this

criterion as well. Further, it will be urged that the evi

dence concerning this restaurant establishes that “a sub

stantial portion of the food which it serves . . . has moved

in commerce.” Finally, it will be submitted that insofar

as there was no substantial evidence from which absence of

state support for segregation as defined by subsection

201(d) can be ascertained, there was no occasion for a

ruling on the validity or applicability of this subsection, and

no justification for the broad injunction.

A. Ollie’s Barbecue Offers to Serve Interstate Travelers

W ithin the Meaning of § 2 0 1 (c ) (2 ) .

The evidence relevant to the “offer to serve” criterion

may be summarized briefly. The trial court found that:

5. The restaurant is eleven blocks from the nearest

interstate highway, a somewhat greater distance from

the nearest railroad and bus station and between six

and eight miles from the nearest airport.

6. Plaintiffs seek no transient trade and do no ad

vertising of any kind except for the maintenance of

a sign on their own premises. To their knowledge

plaintiffs serve no interstate travelers.

Ollie McClung, Sr. testified that his restaurant, which

has ample parking facilities (Tr. 35), is located on a state

7

highway which intersects an interstate highway eleven

blocks away (Tr. 32) ;6 and that he makes no effort to at

tract “transients” (Tr. 36).

The restaurant is of course open to the public (including

Negroes if they will submit to the indignity of segregated

“take-out” service), and there is no evidence that the general

offer to serve the public expressed by the existence of an

open restaurant has been in any way qualified to exclude

an offer to serve interstate travelers, either passing through

the City, or at the beginning or end of a journey, or in

the City on a brief or prolonged stopover during an inter

state trip.

On this state of the record, the question is whether §201

(c)(2), construed in the light of constitutional limitations,

must be read as embodying a requirement that the offer

to serve be—in some sense—“substantial.”

Appellants submit that nothing in the purpose of the Act,

its legislative history, or the Constitution requires that

the statute be construed as if it had read “substantially

offers to serve.”

Numerous considerations oppose any such reading. First,

an initial version of the bill contained a substantiality

requirement as to actual service, but Congress amended

that version and passed the bill in its present form.7 Dele

6 The sworn complaint also mentioned a truck route one block

from the restaurant but asserted that no trade was derived from

this route (Complaint, jf3).

7 The Bill, as originally introduced in the House by Congress

man Celler as H. B. 7152, did contain such a limiting requirement

in Sec. 202(a)(3):

. . . (i) the goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages,

or accommodations offered by any such place or establishment

are provided to a substantial degree to interstate travelers . . .

8

tion of this requirement carries with it not only the plain

implication that Congress intended no requirement that

there be a substantial amount of actual service of interstate

travelers, but implicates, as well, that there was no intent

that offers be “substantial.” If it were otherwise the in

dependent “offer to serve” criterion would make no sense

as it would refer to a highly unlikely category of restau

rants; those that make a substantial offer (or effort) to

serve interstate travelers but actually serve few or none.

Second, the criterion relating to movement of foods in

commerce is immediately contiguous to the “offers to serve”

clause and does have an explicit substantiality requirement.

Congress knew how to say “substantial” when it meant

to do so.

Third, Congress did desire to cover virtually all restau

rants, just as it quite clearly wished to cover all hotels,

motels, etc., by §§201(b)(l) and 201(c)(1), and almost

all motion picture houses, etc. by §§201 (b) (3) and 201(c) (3).

The court below correctly assumed that the purpose of Con

gress was “to put an end to racial discrimination in all

restaurants,” save only an eccentric (and probably thereto

fore nonexistent) class of public restaurants refusing to

admit interstate travelers and serving no substantial por

tion of food which has moved in commerce. The evidence is

persuasive that the purpose of Congress was to enact for

the nation a public accommodations law broadly comparable

in coverage of restaurants (and hotels, theatres, etc., as

Hearings Before Subcommittee No. 5 of the House Committee

on the Judiciary, 88th Cong., 1st Sess., ser. 4, pt. 1, at 653

(1963).

This section of the Act was changed to its present broader form

after passing through the full House Judiciary Committee. Mi

nority Report, H. R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. 79 (1963).

9

well) to the public accommodations laws of 30 states and the

District of Columbia.8

8 In presenting the Bill, Congressman Celler said:

“All we do here is to apply what those 30 States are now

doing and what the District of Columbia is now doing to

the rest of the States so that there shall be no discrimination

in places of public accommodation privately owned. . . . ”

110 Cong. Rec. 1456 (Daily Ed., Jan. 31, 1964).

The issue was sharply focused when Mr. Willis sought to amend

Section 201(c) to “strike out the following, ‘it serves or offers to

serve interstate travelers or’ and insert in lieu thereof the fol

lowing: ‘a substantial number of the patrons it serves are inter

state travelers and.’ ” 110 Cong. Rec. 1901 (Daily Ed., Feb. 5,

1964).

Congressman Celler opposed the amendment:

“This amendment would change that. Instead of being in the

disjunctive, it would be in the conjunctive, and the Attorney

General would have to prove two things. First, he would have

to prove that in a particular restaurant the service is to a

substantial number of interstate travelers. Not merely to in

terstate travelers but to a ‘substantial’ number of interstate

travelers. And, in addition, he would have to prove that a

substantial portion of the food which is served has moved in

interstate commerce. That is a proof that is twofold, and it

makes it all the more difficult for the Attorney General to

establish that proof. It cuts, as it were, the import of the

words ‘affect commerce,’ which are on page 43, line 24, in

half. You have this situation, for example. Whereas, in the

proposal before us, many restaurants are within the orbit

of the prohibition of the bill, many of such restaurants would

not be covered under this amendment. Take, for example, a

roadside restaurant which sells home-grown food which does

not come from outside the State. That would not be covered

under the amendment. Furthermore, a local restaurant which

serves local people with food coming from all over the United

States would not be covered under the amendment. Let me

repeat that.

“We have very significant results here. Instead of having

all restaurants covered, under this amendment you would elim

inate the restaurant, for example, a roadside restaurant that

sells home-grown food. You would also eliminate the local

restaurant that serves local people with food that comes from

all over the country. I do not think we want such a situation

to develop, and for that reason I believe that the whole pur-

10

Fourth, an implied “substantiality” standard would make

it so difficult for citizens and restaurateurs to know their

rights as to completely cripple its administration. Of course,

Title II contains no criminal penalties; its applicability to

numerous categories of restaurants could be hammered out

on a case-by-case basis in the courts. To a certain degree

that is inevitable with any law. But with this law there is

a clear recognition by Congress that its real effectiveness

would in some measure depend upon the fact that the people

of our land are law abiding and will obey the law when it

is clear and unequivocal. The establishment of the Com

munity Relations Service (Title X of the Act) to resolve

disputes concerning the law without litigation (cf. §§204(d),

205), demonstrates the importance which Congress attached

to obtaining voluntary compliance and avoiding many

thousands of lawsuits against individual establishments.

The uncertainties that would befall the law if a substan

tiality test is read into the “offers to serve” criterion may

be illustrated by a few questions and examples. Does the

criterion cover “offers to serve” which are inexplicit as to

interstate travelers, but are, because of the circumstances

in which they are made, highly likely to come to the at

tention of such travelers! Can location be considered so

that a restaurant would be covered merely by being open

to the public in the immediate neighborhood of an interstate

route or terminal absent any actual off-the-premises effort

to attract such travelers? Would Ollie’s Barbecue be in a

different position if the state highway it now adjoins is

made a part of the interstate highway system? Would

pose of covering restaurants would be defeated by this amend

ment.” (Id. at 1902.) (Emphasis supplied.)

The amendment was rejected at p. 1903. It should be noted that

this amendment would have entirely deleted the “offer to serve”

criterion.

11

Ollie’s be covered if: (a) located two blocks from a ter

minal! (b) listed in a national credit card directory! (c)

it advertised in a local paper with substantial interstate

circulation! (d) located in a metropolitan area straddling

a state line—Texarkana, for example!

We have no doubt of the capacity of the courts to re

solve these and manifold similar questions which a substan

tiality requirement would entail. We do doubt and deny

that the Congress really intended to require a Negro citi

zen seeking restaurant service to make these calculations

before he can know his rights.9 This should not be required,

any more than Bruce Boynton was required to know the

intercorporate relations between interstate carriers and

the operator of a terminal restaurant in order to be pro

tected by the Motor Carriers’ Act. Boynton v. Virginia,

364 U. S. 454. The Civil Rights Act is also available as a

defense against criminal charges (§203). The Eighty-eighth

Congress never envisioned that it was assuring the Negro

first class citizenship in restaurants only along interstate

highway routes and in the more or less immediate environs

of air, bus, rail or sea terminals, and only there after an

almost inevitable lawsuit.

It is submitted that the “offer to serve” criterion, should

be given its proper broad scope and construed to cover

all restaurants save those which by some means explicitly

and in good faith negative the implied invitation to serve

9 Senator Magnuson, presenting an analysis of Title II, said :

“Most public eating places would be within the ambit of

title II because of their connection with interstate travelers

or interstate commerce. And in some areas, public eating

places would come within the ambit of title II, because of

the factor of State action.

“At any rate, it is clear that few, if any, proprietors of

restaurants and the like would have any doubt whether they

must comply with the requirements of title II.” 110 Cong.

Rec. 7177 (Daily Ed., Apr. 9, 1984).

12

the general public, among whom, by definition, are inter

state travelers.

B. There Is No P roof That Ollie’s Barbecue Does Not

Actually “Serve . . . Interstate Travelers” ; the

Record Tends to Show the Contrary.

The criterion of actual service of interstate travelers

is plainly designed to complement the “offers to serve”

criterion. As noted above, a substantiality requirement was

deleted from the Bill in the House Judiciary Committee,

and an attempt to reintroduce it was defeated on the House

floor.10 As the appellees sought and obtained an injunction

against the entire Title II they had the burden of estab

lishing that they did not fall within this criterion as well.

The Court found that “to their knowledge plaintiffs serve

no interstate travelers” (emphasis supplied). The finding

exactly conformed to the interrogation of Ollie McClung,

Sr. on direct (Tr. 36):

Q. In your judgment, have you attracted any tran

sient people or travelers? A. Not to my knowledge,

Sir.

But there was no evidence that McClung had made any ef

fort to find out whether occasional interstate travelers con

sumed some of the over half-million meals he serves an

nually. McClung claimed many regular customers and to

know many “by face” (Tr. 35). Though he made quite a

point of enumerating nonracial reasons why he sometimes

refused service to customers (persons who had been drink

ing or used profanit}-; Tr. 48), there was no mention of a

policy of refusing to serve interstate travelers. Quite

plainly there was no evidence because there was no such

policy. The verified complaint sworn by Ollie McClung,

Sr. alleges (1f3):

10 See Notes 7 and 8, supra.

13

Plaintiffs do no advertising and make no effort to

attract transient customers. Their trade lias been re

ceived and retained by virtue of the excellent quality

of the food and service and the wholesomeness of the

surroundings (emphasis supplied).

The referent of the word “their” in the last quoted sentence

seems to be “transient customers” but the passage is not

unambiguous. At the least, there was no assertion or find

ing that no interstate travelers were served. If such a claim

had been proved, the injunction should fall for lack of

standing insofar as it applies to both of the statutory cri

teria dealing with interstate travelers. Actually it seems

probable, viewing the record on balance, that some inde

terminate and perhaps small number of interstate travelers

are among McClung’s customers.

Neither the text of the Act nor its legislative history

supports the notion that the Act is limited to restaurants

serving a substantial number (or proportion) of interstate

travelers. The considerations detailed above in discussion

of the “offers to serve” criterion apply equally to the actual

service criterion:

(a) A version containing a substantiality requirement

was amended in committee, and an attempt to insert such a

rule was defeated on the House floor.

(b) A substantiality rule is explicit in the criterion re

lating to movement of food in commerce.

(c) Congress did wish to cover almost all restaurants

and to discourage easy evasion by the three criteria which

undoubtedly overlap for most establishments.

(d) A substantiality rule would render the Act inadmin-

istrable, leaving persons who desire its protection in doubt

as to their rights with respect to any particular place, and

14

thus encouraging experimentation with disobedience pend

ing a court ruling in every case.

C. A Substantial Portion of the Food Served by

Ollie’s Barbecue Has M oved in Com merce

W ithin the Meaning of Section 2 0 1 ( c ) ( 2 ) .

The trial court concluded “as a matter of law, on the

basis of objective evidence, that a ‘substantial’ portion of

the food served by plaintiffs has moved in commerce with

in the meaning of the act.” The evidence amply supported

this conclusion which can be sustained without gauging

the ultimate reach of “substantial” in this clause. This is

no borderline case.

Fifty-five percent (55%) of appellees’ food purchases in

dollar volume during a recent year was meat (Tr. 39), the

principal commodity sold and a house specialty. Between

80 and 90 percent of this meat was purchased in Birming

ham from one supplier, George A. Horrnel & Co., all of

whose meat came from outside Alabama. There was no evi

dence to show the origin of other products sold.

Thus, a substantial “portion” of the food actually served

at Ollie’s had come from other states. (There is no reason

to believe that Congress meant the substantiality criterion

to refer to an external standard, as the words plainly

refer to a substantial portion of the food served by a par

ticular establishment. But if there is an external standard,

the $69,783.00 spent annually by the McClungs to buy out-of-

state meat is a large and significant amount. Compare this

amount, for example, with the $10,000 “amount in contro

versy” requirement for jurisdiction of the District Courts

over federal question and diversity cases, 28 U. S. C.,

§§1331, 1332.)

There is no basis for a contention that Congress meant

to limit coverage to restaurants which purchased directly

15

from out-of-state wholesale suppliers. The phrase “has

moved in commerce” plainly contemplates coverage of busi

nesses such as appellees’ which purchase from local whole

salers who, in turn, are supplied with goods from other

states.

Finally, the definition of “commerce” in §201 (d) is con

ventional, drawing on the many cases defining commerce

for constitutional purposes. The definition quite clearly

covers the shipment of foods from state to state for eventual

retail sale.

D. As There Was No Evidence Upon W hich It M ight Be

Decided W hether D iscrim ination at A ppellees’ Business

Was S upported by State A ction W ith in the M eaning of

% 201(d), the A ppellees Had No Standing to Obtain,

and the Trial Court No E quity Jurisdiction to Grant,

an Injunction Em bracing This Provision.

No party to the case has contended that the discrimina

tion at Ollie’s Barbecue is “supported by state action” as

that familiar constitutional phrase is given a possibly more

limited statutory meaning in §201(d).

No evidence negated the possibility that the discrimina

tion here was “carried on under color of” a regulation en

couraging segregation like that involved in Robinson v.

Florida, 378 U. S. 153, which would seem to be embraced

by §201(d)(l), for example. Neither was there any record

pertaining to state or local enforcement of the custom of

segregation within §201(d)(2). Cf. Lombard v. Louisiana,

373 U. S. 267. As far as this amicus is advised, the Birming

ham segregation ordinance involved in Gober v. Birming

ham, 373 U. S. 374, was repealed after that decision, but

again appellees made no effort to make a record.

It hardly need be said that Congress would have power

under the fifth section of the Fourteenth Amendment to pro

scribe segregation practices of the types condemned in the

16

Robinson, Lombard and Gober eases by appropriate means.

If such state support existed the Act could constitutionally

be applied. Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 25. If it did not

exist (and the McClungs, as proponents of the idea car

ried the burden to show that it did not), then the McClungs

made no showing of standing to obtain an injunction against

enforcement of this part of the law. Cf. Bailey v. Patterson,

368 U. S. 346.

The trial court opinion states that counsel for the United

States “conceded at oral argument that the State of Ala

bama, in none of its manifestations, has been involved in

the private conduct of plaintiffs in refusing to serve food

to Negroes for consumption on the premises.” We do not

know the exact nature of the purported concession at the

unreported oral argument. It may have been merely that

the government had no evidence of state involvement to

present and did not rely on the state action criterion in

arguing about appellees’ proof. In any event, a concession

of counsel is a plainly insubstantial basis upon which to

enjoin enforcement of portions of an Act of Congress

directly predicated upon recent decisions of this Court.

Certainly, the government did not consent to such an

injunction.

E. The Suggested In terpretation Indicated in This

B rief W'ould Enable the Various Parts o f the

haw to Function in a C om plem entary Manner to

Effectuate the Congressional Purpose.

It may readily be observed that possible constructions of

the various subsections and clauses more restrictive than

those urged above will present serious problems in harmo

nizing the various parts. For example, as noted, an interpre

tation that only “substantial,” “significant” or “vigorous”

“offers to serve” were encompassed would leave that clause

a meaningless duplication of the actual service criterion.

17

It is hard to imagine that Congress wrote a special clause

for the rare restaurant which made a vigorous effort but

did not succeed in getting any interstate travelers. Con

versely, if a substantial number of interstate travelers

were served, why would Congress bother to provide sepa

rately for those which made “offers to serve”? That would

be in contemplation of a null class of restaurants serving-

substantial numbers of interstate travelers, without offer

ing to serve them—either actively or by implication.

This amicus suggests that the purposes of Congress in

enacting the three criteria were to cover virtually all restau

rants, to close loopholes and prevent easy evasion, and to

conform the statutory criteria for demonstrating an effect

on commerce to approved judicial reasoning on the con

stitutional issue of effect on commerce, in support of its

underlying judgment that racial discrimination in the res

taurant business affected commerce and should be regu

lated.

It is common knowledge that most restaurants would

probably be covered by all three criteria. Congress obvi

ously was aware of the pattern of evasion that might fol

low a law relying on only one of the criteria. The “white

intra-state” waiting room gambit (cf. Baldwin v. Morgan,

287 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1861), and Georgia v. United States,

201 F. Supp. 813 (N. D. Ga. 1961), aff’d 371 U. S. 9), might

have been merely the prototype of a new chain of “white

intra-state only” restaurant signs if Congress had let the

matter rest with the “offers to serve” criterion. But few

restaurants could be expected to police such a rule. Thus

the actual service criterion discourages any such attempted

evasion. The criterion involving movement of food in com

merce, while not so easy of evasion, does have a “substan

tiality” test and consequently may frequently involve con

siderable difficulty, time and expense in proof. In almost

18

any case, such proof might necessitate discovery to ob

tain information concerning suppliers and purchasing pat

terns, followed by an elaborate trial with numerous whole

salers called as witnesses to prove the origin of the food;

restaurateurs will commonly have no personal knowledge

of the origin of their foods and will very seldom know of

such things as seasonal variations in the movement of vari

ous types of foods about the country. And, of course, a

Negro traveler or resident standing in front of a restaurant

with his family wondering if the law required his admission

would find such a state of the law hopelessly confusing and

little better than the old order.

It would do incalculable harm if all the efforts to narrow

the Act which failed in Congress were to be engrafted on

it by construction.

The relation of the statutory criteria to the constitutional

reasoning supporting this exercise of the Congressional

power to “regulate Commerce . .. among the several States”

will appear below. Also, of course, all the arguments that

demonstrate the reasonableness of the proposed construc

tions tie in with the constitutional questions concerning

what Congress might reasonably be empowered to do. But

it should be noted that Congress deleted from the bill a

broad criterion for coverage which would have required

that a litigant prove that an offending restaurant’s opera

tions affected travel or the movement of goods.11

11 See Section 202(a) (iii) of H. R. 7152 (discussed in n. 7 above)

providing for coverage i f :

“ (iii) the activities or operations of such place or estab

lishment otherwise substantially affect interstate travel or the

interstate movement of goods in commerce, . . . ” (Hearings

Before Subcommittee No. 5 of the House Committee on the

Judiciary, 88th Cong., 1st Sess,, ser. 4, pt. 1, at 653 (1963).)

The deletion of this provision and insertion of the present criteria

was an expansive thrust by Congress and a recognition that ad

ministration of the Act would be made difficult by the requirement

of having to make such a record.

19

II.

The Power of Congress to Regulate Commerce Among

the States Supports Title II of the Civil Rights Act.

First, a few general principles. In 1824 Chief Justice

Marshall wrote that commerce was “a general term, appli

cable to many objects,” that it “undoubtedly, is traffic, but it

is something more; it is intercourse. It describes the com

mercial intercourse between nations, and parts of nations,

in all its branches, and is regulated by prescribing rules

for carrying on that intercourse.” Gibbons v. Ogden, 22

U. S. (9 Wheat.) 1, 189-190. The vast power granted was

recognized:

It is the power to regulate; that is, to prescribe the

rule by which commerce is to be governed. This power,

like all others vested in Congress, is complete in itself,

may be exercised to its utmost extent, and acknowl

edges no limitations, other than are prescribed in the

Constitution (22 U. S. (9 Wheat.) 1, 196).

And Chief Justice Marshall, the champion of judicial re

view, added:

The wisdom and discretion of Congress, their iden

tity with the people, and the influence which their con

stituents possess at election, are, in this as in many

other instances, as that, for example, of declaring war,

the sole restraints on which they have relied, to secure

them from its abuse. They are the restraints on which

the people must often rely solely, in all representative

governments (22 U. S. (9 Wheat.) 1, 197).

The rules governing exercise of the commerce power

stated in Gibbons v. Ogden, supra, are still vital today. Con

20

gress is barred from regulation only of “that commerce

which is completely internal, which is carried on between

man and man in a state, or between different parts of the

same state, and which does not extend to or affect other

states.” (Ibid, at 194; emphasis supplied.) That com

merce which does “affect other states” is within the regula

tory power of Congress.

Before proceeding to the particulars of this case, and the

reasoning supporting this particular regulation we discuss

two matters argued by appellees which apparently furnish

some of the basis for the opinion below. First, Title II has

been criticized because Congress inserted no findings in the

Act that regulating intrastate activities was necessary.

Second, the Act is criticized because Congress provided

restaurateurs no administrative or judicial forum to liti

gate whether racial discrimination in their facility affected

commerce among the states.

To the former objection one may say, as this Court did

in United States v. Carotene Products, 304 U. S. 144, that

the Act carries a presumption of constitutionality, and a

presumption that Congress has acted rationally whether

or not it sets out “findings” :

Even in the absence of such aids the existence of

facts supporting the legislative judgment is to be pre

sumed, for regulatory legislation affecting ordinary

commercial transactions is not to be pronounced un

constitutional unless in the light of the facts made

known or generally assumed it is of such a character

as to preclude the assumption that it rests upon some

rational basis within the knowledge and experience of

the legislators (304 U. S. at 152).

As to the second objection, the congressional power to

decide when regulating commerce is appropriate has been

21

clear since Gibbons v. Ogden, supra. Congress lias some

times provided for judicial and administrative determina

tions of the effect of particular practices on commerce, but

it has also on numerous occasions made the legislative de

termination that a particular practice affecting commerce

must be regulated or prohibited. Mr. Justice Stone wrote in

United States v. Darby, 312 U. S. 100, 120:

But long before the adoption of the National Labor

Relations Act this Court had many times held that the

power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce ex

tends to the regulation through legislative action of

activities intrastate which have a substantial effect on

the commerce or the exercise of the Congressional

power over it.

In such legislation Congress has sometimes left it

to the courts to determine whether the intrastate activi

ties have the prohibited effect on the commerce, as in

the Sherman Act. It has sometimes left it to an ad

ministrative board or agency to determine whether the

activities sought to be regulated or prohibited have

such effect, as in the case of the Interstate Commerce

Act, and the National Labor Relations Act, or whether

they come within the statutory definition of the pro

hibited Act as in the Federal Trade Commission Act.

And sometimes Congress itself has said that a par

ticular activity affects the commerce as it did in the

present act [Fair Labor Standards Act], the Safety

Appliance Act and the Railway Labor Act. In passing

on the validity of legislation of the class last mentioned

the only function of courts is to determine whether

the particular activity regulated or prohibited is with

in the reach of the federal power. See United States

v. Ferger, 250 U. S. 199 . . .; Virginian R. Co. v. Sys

tem Federation, R. E. D., 300 IT. S. 515, 533. . . .

22

Darby brings us to the central issue at hand. Can it

fairly be said, as the Court below held, that Congress could

not rationally have believed, considering the information

available, that racial discrimination in virtually all types

of public restaurants (save only those rare and insulated

places which serve only local food to local people) affects

commerce.

We submit but a few of the lines of reasoning which may

support such a regulation. Congress surely can regulate

in light of the aggregate effect of numerous enterprises,

large and small, engaged in a particular practice. Wickard

v. Filburn, 317 U. S. 11, should settle that. It would be an

incredible disablement of the Congress to overturn Wickard

and limit congressional power to regulate components of

an industry to where it can be demonstrated as to each

component, to the satisfaction of the courts, that the indi

vidual practitioner of a prohibited practice has the appre

hended adverse effect on commerce.

This would be just as true of the non-communist affidavit

provision of the Taft-Hartley Act (American Communica

tions Assn. v. Bonds, 339 U. S. 382) or the prohibition

against counterfeit bills of lading upheld in United States

v. Ferger, 250 U. S. 199, as it was of the unfair labor prac

tices condemned in N. L. R. B. v. Fainblatt, 306 U. S. 601,

606, where the Court held immaterial “the smallness of the

volume of commerce affected in any particular case.” See

N. L. R. B. v. Reliance Fuel Corp., 371 U. S. 224.

The Act can be sustained by reference to the congres

sional power to regulate matters affecting interstate trav

elers. The movement of persons is “commerce.” Edwards

v. California, 314 U. S. 160; Gloucester Ferry Co. v. Penn

sylvania, 114 II. S. 196, 203. Congressional power is not

dependent on a finding that local practices have completely

blocked interstate travel, or that the practices have affected

23

the volume of travel. Congress can regulate to promote the

safety, ease, pleasure and convenience of interstate travel,

to assure that travel is not embarrassed or disturbed, to

promote travelers’ “freedom of choice in selecting accom

modations.” Cf. Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373, 381, 383.

Surely if the Congress can compel the humane treatment

of cattle, sheep and swine by requiring carriers to unload

them for rest, water and feeding for five consecutive hours

every twenty-eight hours (Live Stock Transportation Act

of 1906; 34 Stat. 607; 45 U. S. C. §§71-74), it can promote

the convenience of human travelers. Cf. Boynton v. Vir

ginia, 364 U. S. 454. There is no constitutional ground for

limiting the congressional power to prohibit racial discrimi

nation to restaurants located within terminals, for other

accommodations also affect travelers. Interstate travelers

using common carriers commonly wander from the main

routes of commerce during stops for business or pleasure

reasons. Vacationing motorists do the same. Congress is

empowered to promote the convenience of travel of Negro

citizens by assuring that public accommodations generally

are open to them.

The statutory criteria dealing with the movement of foods

are also directly related to the constitutional power. The

power of Congress to prohibit the shipment of goods in

commerce is well established (Champion v. Ames, 188 U. S.

321), and this is true without regard to the “innocent”

character of the goods involved. United States v. Darby,

312 U. S. 100, 116-117, overruling Hammer v. Dagenhart,

247 U. S. 251. Congress could prohibit the shipment of

food in commerce for sale in restaurants that practice racial

discrimination, or the acquisition of goods from the chan

nels of commerce for such purpose. It did prohibit the

shipment of goods manufactured under substandard labor

conditions (United States v. Darby, supra). The fact that

24

tlie one case involves “shipment in” and the other “ship

ment out” does not diminish the congressional power. Cf.

McDermott v. Wisconsin, 228 U. S. 115; United States v.

Sullivan, 332 U. S. 689. The effect of such a drafting of

the public accommodations law would be to deny to discrimi

nating restaurateurs access to the great national market in

foodstuffs in aid of a practice which Congress wants to halt.

Yet the actual law, drafted so as to be much more manage

able administratively, and so as to fasten the regulation

directly upon the discriminator serving food which has

moved in commerce, accomplishes exactly the same thing.

There is no interest to be served by requiring Congress to

use an awkward method rather than a direct method for

controlling an evil it has power to prohibit.

And, of course, it is no valid objection to a regulation

or prohibition of commerce that Congress is partly, or even

primarily concerned with fostering the public good or

morality. Hoke v. United States, 227 U. S. 308; Caminetti

v. United States, 242 U. S. 470; United States v. Darby,

supra, at 116; United States v. Rock Royal Co-Operative,

307 U. S. 533, 569.

Numerous other arguments support the regulation in

volved. Among those which have been argued by the United

States are the power of Congress to cope with the injury

to commerce caused by racial strife, including boycotts and

similar demonstrations (cf. N. L. R. B. v. Jones & Laughlin

Steel Co., 301 U. S. 1); the power of Congress to eliminate

the artificial restrictions on the market for goods imposed

by discrimination practices; the power to promote the vol

ume of travel; and the power to reduce other economic dis

locations resulting from discrimination in places of accom

modation. All of these factors were indeed considered by

the Congress which had much evidence on these matters

before it, as the United States has demonstrated at length

25

in its brief in this Court in Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v.

United States, No. 515, October Term 1964.

Finally, it should be reemphasized that the volume of

commerce affected in the particular case is not determina

tive of the congressional power (N. L. R. B. v. Fainblatt,

306 U. S. 601), nor is the partially “local” character of the

particular operation, United States v. Women’s Sportswear

Mfg. Assn., 336 U. S. 460, 464 (“If it is interstate com

merce that feels the pinch, it does not matter how local the

operation which applies the squeeze”). In United States

v. Employing Plasterers Assn., 347 U. S. 186, the Court

was “not impressed” by an argument that the Sherman Act

“could not possibly apply here because the interstate buy

ing, selling and movement of plastering materials had

ended before the local restraints became effective” (347

U. S. at 189). In that case, as in this one, the products had

come to rest never again to move in commerce, yet Con

gress had power to regulate. The application of the Fed

eral Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act of 1938 to a retailer

selling drugs purchased from a wholesaler nine months

after completion of interstate shipment demonstrates the

scope of power to deal with local retail transactions. United

States v. Sullivan, 332 U. S. 689.

26

III.

Title II Does Not Offend Any Other Constitutional

Provisions.

The District Court concluded its opinion by holding

that Title II violated appellees’ rights under the due

process clause of the Fifth Amendment. The Court sum

marily rejected the appellees’ elaborate argument that the

law violated the Thirteenth Amendment. The extent of the

District Court’s reliance upon the Tenth Amendment, which

was quoted in the opinion, is unclear. We shall discuss these

provisions in turn.

A. A R equirem ent That Restaurateurs Open to

the Public P rovide Service W ithout Racial

D iscrim ination Does Not Violate the Fifth

A m endm ent Due Process Clause.

If the District Court’s Fifth Amendment holding is taken

to mean only that the Congress was without power to enact

the law under the commerce clause, the preceding argument

is sufficient answer to it. N. L. R. B. v. Jones & Laughlin

Steel Corp., 301 U. S. 1, 43-47; United States v. Darby, 312

U. S. 100, 125-126.

But perhaps the argument contends that notwithstanding

the commerce power, the right to racially discriminate in

a public restaurant, is a liberty or property right so basic

and fundamental that it may not be regulated by govern

ment at all. This argument would, of course, apply equally

to invalidate all state public accommodations laws under

the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The argument is totally unsupported by precedent. The

validity under the due process clause of state law requir

ing equal treatment in public accommodations has always

27

been assumed. Cf. Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 17-18,

where the Court compared racial discrimination by busi

nesses open to the public with other “private wrongs” and

the discriminating businesses were said to be “answerable

therefor to the laws of the State where the wrongful acts

are committed.” Even more directly applicable is this

statement in District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson

Co., 346 IT. S. 100, 109:

And certainly so far as the Federal Constitution is con

cerned there is no doubt that legislation which pro

hibits discrimination on the basis of race in the use

of facilities serving a public function is within the police

power of the states.

And see Raihvay Mail Assoc, v. Corsi, 326 U. S. 88,

directly rejecting a due process objection to a state law

prohibiting discrimination in employment. Cf. Colorado

Anti-Discrimination Com. v. Continental Air Lines, 372

U. S. 714; Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 28,

34.

Actually, the result urged by appellees would be incon

sistent with a host of decisions of this Court; to name but

a few: Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715; Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350'; Boynton v. Vir

ginia, 364 U. S. 454; Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S. 244;

Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816; and Mitchell

v. United States, 313 U. S. 80.

B. The Thirteenth A m endm ent Is

No Bar to the Act.

The McClungs’ elaborate Thirteenth Amendment argu

ment below is difficult to regard as serious; the District

Court saw nothing in it. It should be remembered that this

argument too would invalidate every state public accom-

28

modations law. Actually, if taken seriously, it would pre

vent almost all economic regulation. It is perhaps sufficient

to note that the argument never comes to grip with the

obvious choice open to any proprietor unwilling to obey a

public accommodations law—but not open to slaves—that

is, to quit and do something else for a living.

This Thirteenth Amendment claim has an especial irony,

in that the McClungs purport to assert the rights of their

employees, most of whom are Negroes. This Court has re

jected attempts like this one to pervert the meaning of the

Thirteenth Amendment from the time of its first construc

tion of the Amendment. Slaughterhouse Cases, 83 U. S. (18

Wall.) 36, 67-72. Cf. Broivn Holding Co. v. Feldman, 256

U. S. 170,199; Arver v. United States (Selective Draft Law

Cases), 245 U. S. 366, 390.

C. The Tenth Am endm ent Does Not

Invalidate T itle II.

The plenary power of Congress over commerce has been

plain from the beginning. Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U. S. (9

Wheat.) 1,197; McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U. S. (4 Wheat.)

316, 407, 421; Brown v. Maryland, 25 U. S. (12 Wheat.)

419. The Tenth Amendment “states but a truism that all

is retained which has not been surrendered.” United States

v. Darby, 312 IT. S. 100, 124. The Amendment does not

limit the power of Congress to regulate commerce by means

appropriate to the permitted end. No matter what “doubts

may have arisen of the soundness of that conclusion” during

a brief period in the Court’s history, they have been “put

at rest.” (Id.)

29

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons it is respectfully submitted

that the judgment below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reen berg

C o n sta n ce B a k er M otley

J am es M . N abrit , I I I

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

C h a r les L. B la ck , J r .

346 Willow Street

New Haven, Connecticut

38

*