Miller v. Johnson Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Appellants

Public Court Documents

February 1, 1995

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Miller v. Johnson Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Appellants, 1995. 7ab211ac-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8648fc96-758c-4911-a89f-51d17f65af80/miller-v-johnson-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

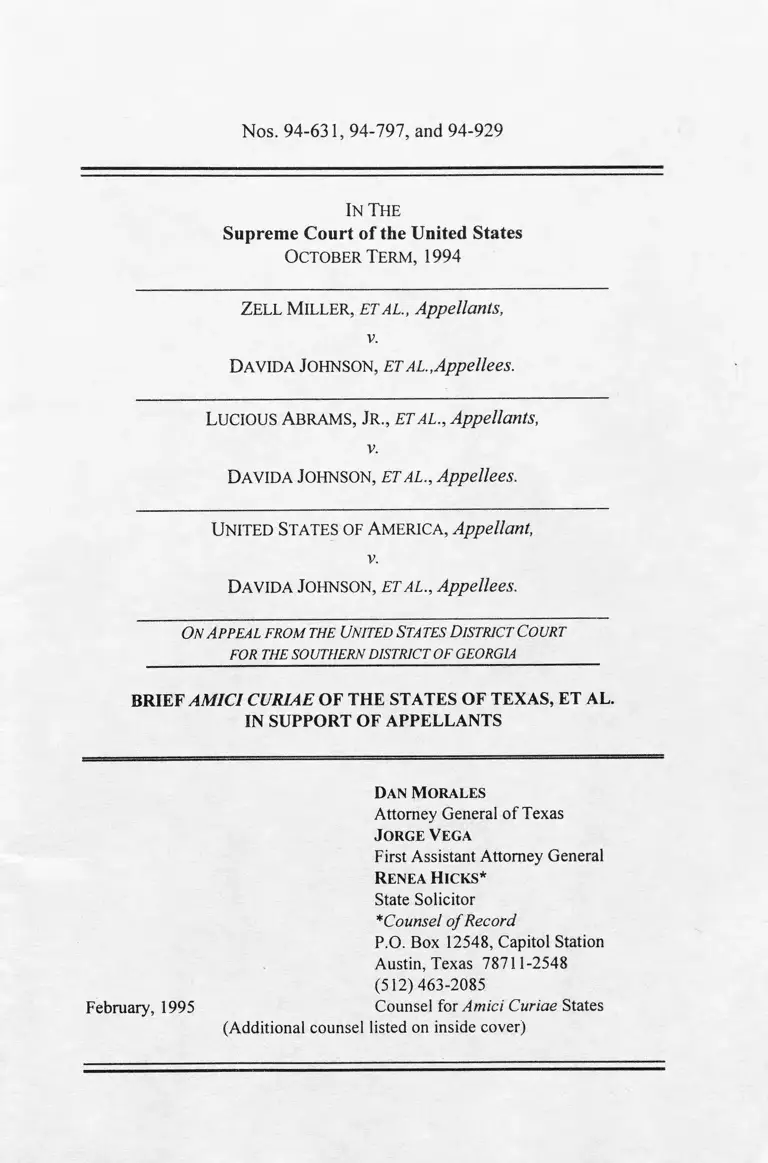

Nos. 94-631, 94-797, and 94-929

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term , 1994

ZELL MILLER, ETAL., Appellants,

V.

Da vida Jo hnson , e t a l ., Appellees.

Lucious Abra m s , Jr ., e t a l ., Appellants,

v.

Da vida Jo hnson , e t a l ., Appellees.

United States of Am erica , Appellant,

V.

Davida Jo hnson , e t a l ., Appellees.

On A p p e a l f r o m th e Un it e d S ta t e s D is t r ic t C o u r t

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE STATES OF TEXAS, ET AL.

IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS

Dan Morales

Attorney General of Texas

Jorge Vega

First Assistant Attorney General

renea Hicks* *

State Solicitor

*Counsel o f Record

P.O. Box 12548, Capitol Station

Austin, Texas 78711-2548

(512) 463-2085

February, 1995 Counsel for Amici Curiae States

(Additional counsel listed on inside cover)

M ichael F. Ea sley

Atto r n ey Gen er a l of

N orth Ca r o lin a

Department of Justice

Post Office Box 629

Raleigh, NC 27602-0629

Counsel for Amici Curiae

T a ble of Co ntents

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ....................................... ii

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE STATES ................ 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................... 3

ARGUMENT ............................................................... 5

I. STANDING IS A CONSTITUTIONAL

PREREQUISITE WHICH MUST BE

ESTABLISHED THROUGH PROBATIVE

EVIDENCE OF THE KINDS OF HARMS

(INCREASED POLARIZED VOTING AND

SELECTIVELY INDIFFERENT LEGISLATIVE

REPRESENTATION) IDENTIFIED IN SHAW

AND WHICH CANNOT BE PRESUMED

MERELY FROM THE PRESENCE OF

OFFENDED SENSIBILITIES......... ............................... 5

II. THE LOWER COURTS’ APPLICATIONS

OF SHAW V. RENO UNDERMINE STATE

PRIMACY IN REDISTRICTING, IGNORE

POLITICAL REALITIES, AND REST ON THE

UNACCEPTABLE PRINCIPLE THAT

MINORITY VOTERS MUST ESCHEW

POLITICAL GIVE AND TAKE IN WHICH ALL

OTHER VOTERS PARTICIPATE ............................... 11

CONCLUSION ................................................................. 18

APPENDIX la

11

T a ble of A u th o r ities

Cases Page(s)

Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S. 737 (1984) ................. ...... 7,10

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) ....................... . 10

Board o f Regents v. Roth, 408 U.S. 564 (1971) ........ 16

Brewer v. Ham, 876 F.2d 448 (5th Cir. 1989) .......... 14

Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109 (1986) ................ 9

DeWitt v. Wilson,

856 F.Supp. 3409 (E.D.Cal. 1994) ...... . 13

Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974) ................ 7

Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735 (1973) ............. 11

Gregory v. Ashcroft, 501 U.S. 452 (1991) ...... 2

Growe v. Emison, 113 S.Ct. 1075 (1993) ................ 16

Hays v. Louisiana,

862 F.Supp. 119 (W.D. La. 1994).......................... . 3

Johnson v. DeGrandy, 114 S.Ct. 2647 (1994) ........... 14,15

Johnson v. Miller,

864 F.Supp. 1354 (S.D.Ga. 1994) ......................... 1,7

League o f United Latin American Citizens v. Clements,

999 F.2d 831 (5th Cir. 3993) ................. .............. 13

Lujan v. Defenders o f Wildlife,

112 S.Ct. 2130 (1992) ........................ ...................... 6,7,8,9

Ill

Moore v. City o f East Cleveland,

431 U.S. 494 (1977) .............................................. 17

Northeastern Florida Chapter o f the Associated General

Contractors o f America v. City o f Jacksonville,

113 S.Ct. 2297 (1993) ............................................ 7

Palmore v. Sidoti, 466 U.S. 429 (1984) ..................... 17

Pleasant Grove, City o f v. United States,

479 U.S. 462 (1987) ............................................. 17

Regents o f the University o f California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 (1978) ............................................... 8

Richards v. Vera, No. 94-805 .................................. 10

Rutan v. Republican Party o f Illinois,

497 U.S. 62 (1990) 12

Shaw v. Barr, 113 S.Ct. 653 (1992) 6

Shaw v. Hunt, 861 F.Supp. 408 (E.D.N.C. 1994) . 1,6

Shaw v. Reno, 113 S.Ct. 2816 (1993) passim

Valley Forge Christian College v. Americans United,

454 U.S. 464 (1982) ............................................... 7

Vera v. Richards,

861 F.Supp. 1304 (S.D. Tex. 1994) ..................... passim

Voinovich v. Quilter, 113 S.Ct. 1149 (1993) ............ 2

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971) ................ 13

White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. 783 (1973) 17

IV

Woodv. Broom, 287 U.S. 1 (1932) .......................... . 16

Constitutional Provisions. Statutes and Rules

2U.S.C. 2c ............................................... ........ ............ 3

42 U.S.C. 1973c ..................................................... . 3

Miscellaneous

Karlan, All Over the Map:

The Supreme Court’s Voting Rights Trilogy,

1993 Sup.Ct.Rev. 245 ........................................ 6

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE STATES

Amici states submit this brief for one basic purpose: to highlight

the threat to state primacy in fundamental redistricting decisions raised

by lower court interpretations of the Court’s opinion in Shaw v. Reno,

113 S.Ct. 2816(1993).

The decisions of the lower courts in this case out of Georgia, in

Hays v. Louisiana, 862 F.Supp. 119 (W.D. La. 1994), probable

jurisdiction noted (Nos. 94-558 and -627), and in Vera v. Richards, 861

F.Supp. 1304 (S.D. Tex. 1994), appeals docketed (Nos. 94-805, -806,

and -988), draw largely identical conclusions from widely divergent

factual settings.1 Particularly disturbing in these conclusions is the

denigration of state policy choices which are independent of race but

made in the maelstrom of redistricting where, by dint of both federal law

and unavoidable reality, race necessarily plays a role. As these rulings

signify, lower courts read Shaw as laying down such broadly prohibitory

constitutional rules that they are overlooking significant state interests

having nothing to do with race and how those interests play out in quite

different ways in the widely differing politics of the various states. The

Court emphasized that Shaw’s prohibition was intended to reach the

“exceptional cases,” 113 S.Ct. at 2826, yet wielding the Shaw sword to

strike down state enactments has become commonplace. Shaw should

be confined to its original narrow channel.

The force of the lower courts’ predominant approach --

combining the most open-ended of standing requirements with the most

confining reading of the role of traditional, long-employed state policy

considerations2 — threatens to convert state legislatures into mere

1 Shaw v. Hunt, 861 F.Supp. 408 (E.D.N.C. 1994), appeal docketed (No. 94-923), while

upholding the North Carolina congressional redistricting effort, disposed of the standing

question in a troubling, expansive fashion, and adopted a disturbingly narrow view of

non-racial redistricting rationales.

2 There are inconsistencies, though, on such fundamental legal points as what counts as a

traditional districting principle. Compare Johnson v. Miller, 864 F.Supp. at 1369 (listing

“protecting incumbents” as a traditional districting principle) with Vera v. Richards, 861

F.Supp. at 1335-36, and Hays v. Louisiana, 862 F.Supp. at 123.

2

formalistic checkpoints on the way to rigid federal judicial control of

redistricting and impermissibly to frustrate conscientious state

legislators by confronting them with indecipherable and possibly

conflicting federal judicial dictates. If the lower court decision here

stands, the path to constitutional redistricting will have become so

narrow and obscure that the only way to successfully navigate it is either

by sheer, blind luck or with a guide — a federal judicial panel — holding

what amounts to a secret map but refusing to reveal it until journey’s

end.

The Court’s stated principles reject such an outcome.

“[Rjeapportionment is primarily the duty and responsibility of the State .

. . rather than of a federal court.” Voinovich v. Quilter, 113 S.Ct. 1149,

1157 (1993). Furthermore, such a result would be anathema to the kind

of federalism the Court has discerned in our federal Constitution, a

federalism which acknowledges the unique and specially protected

position of the states in making choices going to the heart of

representative government. See, e.g., Gregory v. Ashcroft, 501 U.S. 452,

461 (1991).

The states have a strong interest in seeing that their elected

policymakers choose the non-constitutional ideas -- the traditional

districting principles — which inform the configuration of districts

whose voters will elect their representatives in the national Congress.

Now, before a major new round of redistricting has begun and

expectations have settled around lower court interpretations of Shaw v.

Reno, is the time to insure the states retain the authority which some of

the lower courts hearing Shaw claims have taken away: the ability (and

federalism-based right) to comply with the dictates of the Voting Rights

Act while simultaneously balancing and honoring a panoply of other

legitimate state interests.

Almost all states must redistrict congressional seats following

the decennial census and accompanying decennial reapportionment.3

3 At this point, seven states do not have this obligation because they are apportioned

only one congressional representative. They are Alaska, Delaware, Montana, North

Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming. Congressional District Atlas, 103rd

3

All states must perform this task consistently with federal constitutional

law (one-person/one-vote, partisan gerrymandering, and intentional

racial vote dilution, plus, now, whatever the Shaw principle imposes)

and federal statutory law (section 2 of the Voting Rights Act for all

states and section 5 of the Voting Rights Act for some states)4 as well as

with the constitutional and statutory law of the various states.

The increasing complexity of our society, the population growth

which forces more populous congressional districts because of the fixed

number of overall seats, and the indifference of technological

developments in communications and transportation to old political

alignments and subdivisions mean that the next round of redistricting

will call for even more difficult judgments about how to handle the vast

array of state-based, often idiosyncratic considerations falling outside

firmly established federal mandates. Our interest here is to help insure

that Shaw v. Reno will no longer be read by lower federal courts in a

fashion that denigrates non-racial state policy choices.

Aspirations to color-blindness should not be permitted to foist

upon the states a tone-deafness to either their own unique political

concerns or the private racial discrimination which sometimes accretes

through the private ballot to become a powerful bloc of political

exclusion. The lower court’s overly expansive reading of Shaw’s

doctrine threatens precisely such a result, displacing the finely-tuned

political ears of the people’s elected state representatives with the

figurative tin ear of an unelected federal judiciary in a matter lying at the

heart of state governance. The states do not want this to happen.

Congress of the United States, vol. 1 at v (U.S. Dept, of Commerce Feb. 1993). By

federal statute, all congressional districts must be single-member. 2 U.S.C. 2c.

4 All or parts of sixteen states are subject to the preclearance requirements of section 5 of

the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. 1973c. 28 C.F.R. Part 51 App. (listing the states, 9 of

which are covered in their entirety and 7 of which have only parts covered, and giving

the dates on which coverage was formally announced).

4

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Constitutional standing to raise a Shaw claim was not implicitly

or explicitly determined in Shaw v. Reno. In fact, the court expressly

reserved on this issue. The requirement that a Shaw plaintiff

demonstrate some kind of concrete harm from the state action giving

rise to a Shaw claim certainly has not been eliminated, nor, under the

Court’s Article III jurisprudence, could it be. The lower court’s explicit

determination in this case that the plaintiffs had not demonstrated any

harm should suffice to dispose of the case.

Shaw did provide markers for what would constitute standing by

identifying the harms that could arise from a Shaw claim. Demonstrable

evidence of increased racial polarization as a result of the creation of a

contorted minority opportunity district or of a narrowing of the polity to

which the representative elected from a challenged district responds, to a

racially dominant group only, might suffice to establish the kinds of

harm sufficient to impart standing.

Shaw cannot be read to preclude minority voters from engaging

in the rough and tumble of political activity typically associated with

redistricting. Such a reading would run counter to the basic meaning of

the very constitutional provision on which the decision rests, the Equal

Protection Clause. Further, it would constitute its own kind of explicit

racial classification, requiring minorities to abstain from electoral

politics while permitting all others to participate.

Yet, the effect of the lower courts’ reading of Shaw is precisely

to inject such disequilibrium into American redistricting politics. In part

because of the posture in which the original case arrived at the Court,

with the bare bones complaint about race forming the focal point of the

decision, the lower courts have developed a kind of myopia about these

cases. They misguidedly by attribute to race the distortions of the

districts under attack, ignoring the political realities: that state political

actors massage district boundaries to embed non-racial state policies into

the districts finally drawn. Such traditional districting principles include

incumbent protection, preservation of core districts, grouping of

communities of interest (to which the unelected may be blind), and a

5

host of other state-based traditions that are intimately bound up with the

political, economic and social life of the state.

Ultimately, what is at work here is the denigration of the state’s

fundamental right to make non-racial policy choices in this area and the

arrogation to federal courts of their own non-constitutional preferences

about how sovereign states should establish the basic structures to elect

their representatives. Shaw was not a signal for such a break with

longstanding, basic doctrines of federalism. This should be the occasion

for the Court to re-confine Shaw to its original narrow compass and

make clear again what was said in the original decision: it reaches only

the “exceptional cases.” The cases before the Court now do not fit this

description, and they should be held to fall outside Shaw’s reach.

ARGUMENT

In the context of redistricting challenges, standing principles are

being read too expansively and traditional districting principles too

narrowly. Palpable reality — in terms of both individualized, concrete

harm on the standing front and a cleateyed, commonsense acceptance

of everyday political concerns on the traditional districting principle

front -- is in danger of being cast aside in the wake of Shaw v. Reno.

Shaw does not require, or even countenance, such departures, and the

amici states urge the Court to reiterate reality’s place in Shaw

jurisprudence.

I. STANDING IS A CONSTITUTIONAL PREREQUISITE

WHICH MUST BE ESTABLISHED THROUGH PROBATIVE

EVIDENCE OF THE KINDS OF HARMS (INCREASED

POLARIZED VOTING AND SELECTIVELY INDIFFERENT

LEGISLATIVE REPRESENTATION) IDENTIFIED IN SHAW

AND WHICH CANNOT BE PRESUMED MERELY FROM THE

PRESENCE OF OFFENDED SENSIBILITIES.

Standing is a threshold issue of constitutional dimension. The

Court should delineate the contours of standing to raise a Shaw claim in

the setting of this case, which has been fully tried on the merits, and

make clear that the standing requirements applicable in other contexts

6

are fully applicable to redistricting cases and racial discrimination

claims involving them.

Shaw v. Reno did not treat the standing issue at all. While some

have expressed consternation about this omission, see Karlan, All Over

the Map: The Supreme Court’s Voting Rights Trilogy, 1993 Sup.Ct.Rev.

245, 278 (“remarkable departure”), it is fully understandable in the

specific context of the case as it came to the Court the first time. The

lower court had dismissed the action for failure to state a claim. There

was only a bare complaint, and the Shaw plaintiffs at that point had

adduced no evidence on any issue, including any fact-specific issues of

injury and causation of the type emphasized in Lujan v. Defenders o f

Wildlife, 112 S.Ct. 2130 (1992), as essential to the establishment of

constitutional standing.

When the case came up on appeal from the district court’s Rule

12(b)(6) dismissal, the Court expressly refused to note probable

jurisdiction regarding a standing question proffered by the appellants.5

Then, in its opinion, the Court explained that “[tjoday we hold only that

appellants have stated a claim under the Equal Protection Clause . . .”

113 S.Ct. at 2832 (emphasis added). Whether the allegations of a

complaint state a cause of action, and whether the particular plaintiffs

making the allegations have standing to press the action, are entirely

separate issues.

/

Despite the Court’s refusal to reach the standing issue, the lower

courts hearing Shaw claims have tended to find in the Shaw decision an

implicit disposition of standing. Shaw v. Hunt, 861 F.Supp. at 427

5 See Jurisdictional Statement, No. 92-357, i (“Do white voters have standing to seek

relief from congressional redistricting which was intended by both the state and federal

defendants to result in the election of minority persons to Congress from two majority-

minority districts?”) In noting probable jurisdiction, the Court directed that “[argument

shall be limited to the following question:” “whether a state legislature’s intent to

comply with the Voting Rights Act and the Attorney General’s interpretation thereof

precludes a finding that the legislature’s congressional redistricting plan was adopted

with invidious discriminatory intent where the legislature did not accede to the plan

suggested by the Attorney General but instead developed its own.” Shaw v. Barr, 113

S.Ct. 653 (1992).

7

{Shaw “implied a standing principle”), Vera v. Richards, 861 F.Supp. at

1331 n.38 (Court “inferentially decided they had constitutional

standing”), and Johnson v. Miller, 864 F.Supp. at 1370 {Shaw

“implicitly recognizes”). Even were such a ruling “implicit” in Shaw —

and it was not — the Court has repeatedly emphasized that implicit

pronouncements on constitutional issues — and standing is just such an

issue — do not settle them. Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651, 671

(1974). Thus, standing in cases raising Shaw claims remains an open

issue.

The lower courts’ misreading of Shaw on standing, unless

corrected by the Court, would dramatically increase the exposure of

states to redistricting challenges by plaintiffs not constitutionally entitled

to bring such claims and correspondingly enmesh the federal courts even

further in micromanaging the details of core state activities. It would fly

in the face of this Court’s admonition that federal judges do not have “an

unconditional authority to determine the constitutionality of legislative

or executive acts,” but may only do so where the constitutional

requirements of a “case or controversy,” including the threshold

requirement of standing, are met. Valley Forge Christian College v.

Americans United, 454 U.S. 464, 471 (1982).

Shaw v. Reno does not necessitate the approach taken by the

lower courts and, in fact, offers a roadmap for elucidation of a standing

principle in these kinds of cases that is far more consistent with extant

standing doctrine than the open-ended approach of the lower court in

this case.6 One of the three essential elements of the constitutional law

of standing is that plaintiffs must establish “injury in fact,” meaning that

they must demonstrate some harm that is “concrete and particularized”

instead of merely “conjectural or hypothetical.” Lujan v. Defenders o f

Wildlife, 112 S.Ct. at 2130. Generalized grievances are insufficient for

standing, and the mere claim of a right to a particular type of conduct

falls short of constitutional minimums. Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S. 737

(1984). Northeastern Florida Chapter o f the Associated General

6 The different considerations applicable to standing to raise a vote dilution claim are not

discussed here because, as Shaw explained, the claim it recognizes is “analytically

distinct” from a vote dilution claim. 113 S.Ct. at 2830.

8

Contractors o f America v. City o f Jacksonville, 113 S.Ct. 2297 (1993),

explaining that the existence of higher hurdles, not the likelihood of

achieving a particular goal, imparts standing in an equal protection case,

does not alter Lujan’s fundamental requirement of an injury in fact.

Even under Northeastern Florida, the benefit sought to be attained still

must be concrete (as were the sought-after municipal construction

contracts there).7

In explaining the kinds of concrete harms that might be

attributable to a Shaw claim, the Court pointed to the possibility that

creation of the kind of minority opportunity district targeted by the Shaw

plaintiffs might exacerbate racial division by increasing racial bloc

voting. 113 S.Ct. at 2827. Also, as another potential harm, the Court

posited that representatives elected from the targeted minority

opportunity districts might ignore their polity as a whole while focusing

nearly exclusive attention on the dominant minority group in the district.

Id.

However, whether one of these distinctive harms has actually

occurred and is caused by a disputed districting plan is, like every issue

of injury in a standing case, a question of fact. In this setting, as in all

other standing cases, the plaintiffs bear the burden of demonstrating with

probative evidence that the requisite injury had been caused by the

districting plan at issue. t

The party invoking federal jurisdiction bears the burden

of establishing these elements . . . Since they are not

mere pleading requirements but rather an indispensable

part o f the plaintiff’s case, each element must be

supported in the same way as any other matter on which

the plaintiff bears the burden of proof, i.e. with the

manner and degree of evidence required at the

successive stages of litigation . . . [Tjhose facts . . .

' Regents o f the University o f California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978), similarly

requires a palpability in the goal which is sought to be attained. Once Allan Bakke could

clear the challenged hurdles to admission, he wanted a medical education and degree.

This concrete goal was essential to his standing. 438 U.S. at 280 n.14.

9

must be “supported adequately by the evidence adduced

at the tria l. . . "

Lujan v. Defenders o f Wildlife, 112 S.Ct. at 2136-37 (emphasis added;

internal citations omitted).

The plaintiffs in this case appear to have offered no evidence

going to these two types of harms that must be associated with a Shaw

claim, and the lower court made no findings about the existence of such

harms.8 They thus have failed to establish the requisite injury in fact.

Shaw v. Reno could not have rested on any generalizations about

injuries arising from the impact of irregularly shaped districts drawn

with a race-consciousness. The kind of claim it recognized was, by the

Court’s own terms, new, rare, and exceptional. Until the instant case

and the Louisiana v. Hays case, no case which had been tried on the

merits involving a Shaw claim had made its way to the Court. The Shaw

opinion even continues the emphasis that “racial bloc voting . . . never

can be assumed, but specifically must be proved in each case,” 113 S.Ct.

at 2830, a proposition which necessarily carries with it the requirement

that increases in bloc voting be proven.

Similarly, the Court has explained that evidence is required to

establish that an elected official will fail to represent all of his or her

constituents. In Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109 (1986), the Court

held:

An individual who votes for a losing candidate is usually

deemed . . . to have as much opportunity to influence that

candidate as other voters in the district. We cannot

presume in such a situation, without actual proof to the

contrary, that the candidate elected will entirely ignore the

interests of those voters . . . [Wjithout specific supporting

evidence, a court cannot presume . . . that those who are

elected will disregard the . . . under-represented group.

8 These types of harms cannot be assumed; indeed there is evidence to the contrary in the

Louisiana, Texas and Maryland cases. See Appendix A.

10

478 U.S. at 132 (emphasis added).

Other lower courts have suggested that “stigmatization” by a

race-based redistricting plan might impart standing, a proposition

embraced by some of the parties before this Court in other cases. See,

e.g., Richards v. Vera, No. 94-805, Appellees’ Motion to Affirm at 15.

Yet, the Court in Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S. 737 (1984), rejected

precisely such stigmatic harm as inadequate to establish standing.

There, the Court stressed that stigmatic injury is never sufficient to

support standing unless accompanied by proof of “some concrete

interest with respect to which respondents are personally subject to

discriminatory treatment. That interest must independently satisfy the

causation requirement of standing doctrine.” Id. at 757 n.22 (emphasis

added). The same absence of concrete injury that was fatal to standing

in Allen is fatal to the stigmatic injury claim in this case.

The lower court in this case did make an explicit finding

relevant to the standing issue. It determined that the plaintiffs “suffered

no individual harm [and that] the 1992 congressional redistricting plans

had no adverse consequences for these white voters.” 864 F.Supp. at

1370. The fact that the court then went on to find standing demonstrates

the abandonment of standing principles for Shaw v. Reno claims. The

Court has not countenanced such an abandonment and cannot do so

without overruling, at a minimum, Allen v. Wright.

Offended sensibilities were not enough for standing in Allen v.

Wright, and they are not enough for standing in cases such as this one.

Furthermore, the harms the Court has identified as possibly associated

with a Shaw claim are not to be presumed; they must be proven as part

of the plaintiffs case on standing. That did not happen in this case, and

it does not appear to have happened in the other Shaw cases now

pending before the Court.

Until the decision in Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962), just

over thirty years ago, redistricting law fell largely outside federal

jurisdiction for reasons of justiciability. Now, under the lower court’s

theory at any rate, we have moved to the point where there are virtually

11

no justiciability restraints in this arena even though standing doctrine is

widely perceived to have moved onto a more restrictive constitutional

path. This unjustified expansion of Shaw v. Reno’s reach calls out for

correction by the Court.

II. THE LOWER COURTS’ APPLICATIONS OF SHAW V

RENO UNDERMINE STATE PRIMACY IN REDISTRICTING,

IGNORE POLITICAL REALITIES, AND REST ON THE

UNACCEPTABLE PRINCIPLE THAT MINORITY VOTERS

MUST ESCHEW POLITICAL GIVE AND TAKE IN WHICH ALL

OTHER VOTERS PARTICIPATE.

In Shaw v. Reno, the Court recognized a new, “analytically

distinct” claim in the equal protection law of redistricting and voting

rights.

[Rjedistricting legislation [is unconstitutional if it] is so

extremely irregular on its face that it rationally can be

viewed only as an effort to segregate the races for purposes

of voting, without regard for traditional districting principles

and without sufficiently compelling justification.

113 S.Ct. at 2824.

But nothing in Shaw serves to undo the Court’s longstanding

acceptance of the quite obvious fact that politics in all its forms, both

refined and raw, plays a central role in redistricting decisions. Labeling

efforts to squeeze politics out of the redistricting process “politically

mindless,” the Court has noted the “impossible task of extirpating

politics from what are the essentially political processes of the sovereign

states.” Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735, 753-54 (1973):

Nor is the goal of fair and effective representation

furthered by making the standards of reapportionment so

difficult to satisfy that the reapportionment task is

recurringly removed from legislative hands and performed

by federal courts which themselves must make the

political decisions necessary to formulate a plan or accept

12

those made by reapportionment plaintiffs who may have

wholly different goals from those embodied in the official

plan. From the very outset, we recognized that the

reapportionment task dealing as it must with fundamental

“choices about the nature of representation,” . . . is

primarily a political and legislative process.

Gaffney, 412 U.S. at 749 (emphasis added; internal citations omitted).

Shaw’s necessarily narrow frame of reference has had

unfortunate consequences for the lower courts deciding cases in its

wake. Confined as it was to the pleadings, virtually its only ingredient

was race; the rich stew of trial that holds other ingredients — an

especially diverse mixture in redistricting cases — had not yet begun to

be prepared.

This confined focus of the Shaw opinion has induced a myopia

in the lower courts. Wherever they look, they seem to see only race.9

This reflects “a naive vision of politics,” to use a phrase from Rutan v.

Republican Party o f Illinois, 497 U.S. 62, 103 (1990) (Scalia, J.

dissenting). More than race nearly always informs congressional (or, for

that matter, any) redistricting. It is safe to observe that congressional

districts never are drawn in a vacuum; potential candidates are evaluated

and potential political repercussions are pored over regardless of

whether a particular district is intended to be a minority opportunity

district satisfying the commands of the Voting Rights Act or the redoubt

of some important or long-powerful state political figure.

For this decade’s round of redistricting, the technology for these

kinds of evaluations, in the form of sophisticated computer systems, had

evolved to become at least an order of magnitude more powerful than

ever before and the raw information similarly more voluminous and

9 For example, highly integrated, single-county urban districts have been struck down,

see Vera v. Richards, supra, in the face of Shaw’s description of the archetype of a

distorted district. Such a district, posited the Court, is one that includes “individuals who

belong to the same race, but who are otherwise widely separated by geographical and

political boundaries.” 113 S.Ct. at 2827 (emphasis added).

13

more detailed. Population data, for example, was available down to the

census block level for the first time, and there were 7 million such

blocks. Congressional District Atlas, supra n.3, vol. 1 at v. The result

of this technological evolution tended to be the same in the political

redistricting world as biological evolution has in the natural one:

increased complexity of organization.

Some of the information used in this decade’s redistricting was

racial in character. Compliance with sections 2 and 5 of the Voting

Rights Act, not to mention the antidiscrimination principle of the Equal

Protection Clause, required it. The census information on race also

provided other useful insights about the consequences of drawing

congressional district lines in one place or another, but only when used

in combination with other data and the political knowledge peculiarly

available to elected officials.10

It hardly follows from such uses, though, that race is the sole11

or even dominant factor accounting for the ultimate shaping of any

given district. It would be, to borrow a phrase from Shaw, an

“exceptional case[]” in which this were so. Working from the tandem

elements of a Shaw claim — that the district shape be irregular (i.e.,

wildly inconsistent with traditional districting practices) and that the sole

(or even dominant) reason for the irregularity be race — it might be

possible to arrive at an idea of an archetypal district which would require

10For example, in regions where racial voting patterns tend to divide along partisan

lines, useful information about the partisan tendencies of a particular area could be

gleaned from a sophisticated reading of such census data to get a reading “on the basis of

their politics rather than their race or ethnicity[,]” Rutan, 497 U.S. at 108 (J. Scalia,

dissenting). The Court has seen such phenomena at work in electoral settings and even

found it determinative as a non-racial explanation for questioned voting activity. See,

e.g., Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971). Lower courts have taken a similar tack

in rejecting section 2 claims, finding partisan activity where plaintiffs assert racial

patterns. See, e.g., League o f United Latin American Citizens v. Clements, 999 F.2d 831

(5th Cir. 1993) (en banc), cert, denied, 114 S.Ct. 878 (1994) (rejecting section 2

challenge to Texas judicial election system).

' ' i n a California redistricting case, the court read Shaw as condemning redistricting

based “solely” on race. DeWitt v. Wilson, 856 F.Supp. 1409, 1412 (E.D.Cal. 1994),

appeal docketed (No. 94-275). But other lower courts, including the one here, expand

the Court’s language on this point. See 864 F.Supp. at 1373-74.

14

the state to satisfy the twin tests of compelling interest and narrow

tailoring. If circumstances in the state, especially those surrounding the

question of whether racial bloc voting persists, were such that

reasonable legislators drawing district lines would rtQl have concluded

that section 2 of the Voting Rights Act required the creation of a

minority opportunity district and that (for those covered) section 5 of the

Voting Rights Act required the maintenance of such a district, and if

they nonetheless drew such a district by meticulously searching for blocs

of racial minorities to string together into a district without regard to

state-based districting principles, then a Shaw claim could be made out.

In a less extreme scenario, it was not infrequent during the last

round of redistricting that legislators preparing to redraw their state’s

congressional districts were confronted with circumstances indicating

that failure to draw a minority district in a region of the state12 would

result in liability under section 2. Political reality suggests that they

would hardly simply turn on the computer, find a concentration of

minority voters sufficient to satisfy section 2’s requirements,13 and then

draw the district lines in as neat a fashion as geography and the

computer would permit. That would constitute making race the clearly

dominant, if not sole, factor in the shape of a district, and that would

probably constitute a Shaw violation, especially if the district were

misshapen and there were an absence of meaningful communities of

interest among the district’s residents.

But that scenario is not what happens in the real world of

political redistricting. Once it is determined that the Voting Rights Act

is going to require the creation or maintenance of a minority opportunity

12Despite the Court’s having left open the question of whether the proper frame of

reference in a statewide redistricting for a statewide body for evaluating the first Gingles

factor (geographic compactness and sufficient minority population) is localized or

statewide, Johnson v. DeGrandy, 114 S.Ct. 2647, 2662 (1994), legislatures as a practical

matter tend to assess the question by region. It is noteworthy that the United States,

which urged a statewide frame of reference, id., is the principal enforcer of section 5 of

the Voting Rights Act.

13A leading section 2 standard requires a threshold of 50% minority voting age

population to create a minority opportunity district. See Brewer v. Ham, 876 F.2d 448

(5th Cir. 1989).

15

district, a host of other factors and players make their appearance.

Those factors and players (for example, incumbent members of

Congress, or their surrogates, from the affected region) begin to mold

the districts as much as they can so that Voting Rights Act compliance

can coexist with other political interests and redistricting principles.

When the molding is complete, the likelihood is high that the neat lines

of the initial conceptual minority district have been changed, even

distorted, to accommodate other interests having nothing to do with race.

A minority opportunity district, compliant with the Voting Rights Act

and perforce drawn with some attention to race, will continue to exist

but as part of the state’s larger political, economic and social life. As

long as the non-racial considerations affecting the ultimate boundary

lines for such a minority opportunity district are reasonably related to

the state’s larger political, economic or social life and the purpose of

redistricting, a Shaw claim should fail.

Assuming sections 2 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act themselves

are constitutional (an unchallenged proposition in the Shaw cases to

date), to hold otherwise, and constitutionally forbid politics-driven

distortion of minority opportunity districts while permitting it for other

districts, would create its own invidious racial classification. It would

set up one rule for the creation of minority opportunity districts —

politics is forbidden and only purely racial considerations shall operate -

- and quite another for non-minority (i.e., white dominant) districts. In

short, minorities would be forbidden to play non-racial politics that are

fully available to everyone else. 14 Not only is such a result not required

by the Equal Protection Clause; it runs directly counter to it. Cf.

DeGrandy, 114 S.Ct. at 2661 (“minority voters are not immune from the

obligation to pull, haul, and trade” in the political sphere).

The appropriate test of whether the factors driving the shapes of

minority opportunity districts are reasonably related to the state’s larger

political economic or social life is keyed to the traditional districting

^4At least one of the lower courts hearing a Shaw claim insists on such a rule for

minority opportunity districts. Vera v. Richards, 861 F.Supp. at 1343 (district “must

have the least possible amount o f irregularity in shape, making allowance for the

traditional districting criteria”) (emphasis added).

16

principles referenced in Shaw. Consistent with the longstanding

doctrine that redistricting is primarily a state function, see, e.g., Growe

v. Emison, 113 S.Ct. 1075, 1081 (1993), state law and state tradition are

the proper source for discerning traditional districting principles.

Certainly, federal law is not the place to look. In Wood v. Broom, 287

U.S. 1, 7 (1932), the Court held that the 1929 federal reapportionment

act for Congress deliberately omitted requirements of compactness and

contiguity for congressional districts. These requirements never have

been reinstated in federal law.

This, however, is a state-specific inquiry; just as the Court

recognizes that different constitutional requirements flow from the

states’ different rules about property, Board o f Regents v. Roth, 408 U.S.

564 (1971), so too must it recognize that different Shaw implications

flow from the states’ different traditions about redistricting. The

specialized redistricting abstention doctrine applied in Growe v. Emison

is implicit recognition of this proposition.

Some states have explicit congressional redistricting

requirements. West Virginia, in article I, section 4, of its constitution

requires compactness and contiguity. California, in article XXI, section

1, of its constitution requires “respect” for the “geographical integrity of

any city, county, or city and county, or of any geographical region” to

the extent possible without violating other standards. Some states, on

the other hand, have no explicit constitutional or statutory redistricting

requirements for congressional seats. Texas, for example, falls in this

latter category.

To discern in any given case whether a state has distorted

minority districts with an indifference to its traditional districting

criteria, a court considering a Shaw claim must look to several potential

sources. State constitutional and statutory law on the topic, state case

law, prior redistricting and political history, and contemporaneously-

created districts other than the one under challenge all must be

evaluated. If a minority opportunity district is severely distorted (for

example, far beyond the kind of hypothesized district that might satisfy

the first Gingles threshold factor in a section 2 setting) and creeps in and

17

out of city boundaries,15 while other contemporaneous wo/i-minority

districts in the state do not do so, then further inquiry may be warranted

to determine whether other traditions — e.g., incumbent protection and

preservation of the core of old districts, White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. 783,

791 (1973) -- explain the result.

The lower courts decisions to date in Shaw cases, however, fail

to accord sufficient weight to the states’ own legitimate traditions. By

giving an unduly pinched reading to “traditional districting criteria,”

lower courts ignore the reality that these criteria spring from the states

and their political, economic and social traditions, not from some free-

floating federal ideal. The approach of the lower courts raises the

concerns flagged by the plurality in Moore v. City o f East Cleveland,

431 U.S. 494, 502 (1977) (Powell, J.) (“there is reason for concern lest

the only limits to such judicial intervention become the predilections of

those who happen at the time to be Members of this Court”).

If left unchecked, this unduly restrictive view — constitutionally

unwarranted and federalism-insensitive — inevitably will create strong

disincentives for state compliance with the Voting Rights Act. State

legislators hardly are going to embrace the Voting Rights Act and

willingly comply with section 2’s strictures if they are being told by the

federal courts that, in doing so, they must sacrifice a host of other

perfectly legitimate objectives in a rippling effect across the state or

region. The Shaw doctrine requires no such unraveling of states’ rights

or of the protections afforded minority voters by the Voting Rights Act.

It does not require a state to choose between its own non-racial politics

and a recognition, where the facts warrant it, of the need to account for

the reality of private racial biases, cf. Palmore v. Sidoti, 466 U.S. 429,

433 (1984), in the way it groups voters into districts to roughly

counterbalance those biases.

1 Political subdivision boundaries themselves carry no imprimatur of purity. Section 5’s

preclearance requirement applies to changes in such boundaries precisely because they

are subject to manipulation for racial ends. See City o f Pleasant Grove v. United States,

479 U.S. 462 (1987) (upholding preclearance denial to annexation).

18

Shaw is not a license to lower courts to ignore legitimate state

policy choices or to pick and choose among them according to what fits

their judicial sensibilities. The states urge the Court to reinstate their

primacy in the redistricting field, consistent with the longstanding

principle the Court has embraced since redistricting became litigable in

the federal courts.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the amici curiae states urge reversal

of the decision of the court below.

Respectfully submitted,

Dan M orales

Attorney General of Texas

Jorge Vega

First Assistant Attorney General

Renea H icks*

State Solicitor

*Counsel o f Record

P.O. Box 12548, Capitol Station

Austin, Texas 78711-2548

(512) 463-2085

APPENDIX

la

Summary of Record Evidence In Redistricting

Cases Showing Decreasing Racial Polarization

in Minority Opportunity Districts

The facts, taken from the record in this and other cases, show

that the creation of minority opportunity districts has not

exacerbated racially polarized voting. To the contrary, expert

evidence on racially polarized voting shows that white voting for

minority candidates generally has increased in minority opportunity

districts. For example, Districts 2 and 11 in Georgia became

minority opportunity districts for the first time in 1992. From 1984

to 1990, only one percent of white voters in the precincts now within

District 2 voted for black and hispanic candidates in statewide

elections. The corresponding white vote for black and hispanic

candidates in District 11 was only four percent. A dramatic increase

in white voting for black and hispanic candidates occurred in 1992,

simultaneously with the first campaigns in the new minority

opportunity congressional districts. Twenty-nine percent of white

voters in District 2 and 37 percent of white voters in District 11

voted for black and hispanic candidates in statewide elections in

1992.'

Evidence from other States shows that minority opportunity

districts, including irregularly-shaped districts, have resulted in

increased white support for minority candidates. In 1984, only 8

percent of white voters voted for the black candidate in the

Democratic congressional primary in what is now Louisiana, District

2. In 1990, the first year as minority opportunity district, 44% of

white voters voted for black candidates and in 1992 the white vote

for black candidates rose to 74%. (Years between 1984 and 1990 did

not involved any black vs. white congressional elections that could

be included in the analysis). Louisiana’s District 4 became a

minority opportunity district in 1992. From 1986 to 1990, white

voting for black congressional candidates in that District ranged

from a low of 3% (3 elections) to a high of 22% (one election). In

1992, white voting for black candidates rose to 58%. Declaration of

Richard Engstrom, July 20, 1994, Chart One, Hays v. Louisiana. 1

1 See DOJ Ex. 24, Report of Dr. Allan J. Lichtman, May 26, 1994, Tables 1-3.

2a

In Texas, the chart below2 reports pre-1992 and 1992 white

voting for Black candidates in Texas’ two African American

opportunity districts (Districts 18 and 30) and for Hispanic

candidates in Texas’ seven Hispanic opportunity districts.

TEXAS POLARIZED VOTING

ELECTIONS HELD IN MAJORITY-MINORITY

CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICTS MINORITY VERSUS WHITE

ELECTIONS 1992 AND PRE-1992

Minority Opportunity Districts

15 16 18 20 23 27 28 29 30

% WHITE VOTE

FOR BLACK/HISPANIC

CANDIDATES *

1992

ELECTIONS 37% 33% 29% 25% 16% 50% 0% 5% 64%

PRE-1992

ELECTIONS 22% 30% 24% 6% 9% 27% 7% 5% 15%

* Results are averages for Statewide, Countywide and

Legislative District elections held within the precincts of the

minority opportunity districts. 1992 results for Districts 27,

28, and 30 are based on one election.

In both African American districts, white bloc voting decreased in

1992. This decrease in white bloc voting occurred even though

District 18 was made more irregular by the 1991 redistricting and

District 30 is admittedly irregular in shape (although no more

irregular than majority-white districts in Texas). Significantly,

District 30, the newly-created African American opportunity district

2 From information set out in State Ex. 14, Final Report of Dr. Alan J. Lichtman,

App. 2 Tables 1-9, Vera v. Richards.

3a

in Dallas, showed a large increase in white vote for black candidates,

from only 15% of white voters in pre-1992 elections to 64% in 1992.

Texas’ Hispanic opportunity districts show a consistent

pattern, with substantial decreases in white bloc voting in 5 districts,

no change in one district (29) and an increase in only one of seven

districts (28). Significantly, the single district which showed an

increase in white bloc voting, District 28, is not irregularly shaped

and was found to meet constitutional requirements by the District

Court in Vera v. Richards.

Maryland is also consistent. A new African American

opportunity district, District 4, was created in the 1991 redistricting.

White voting for black congressional candidates in Prince George’s

County, where both new District 4 and old District 5 were centered,

increased from 0% in the 1990 Democratic primary to 44% in the

1992 Democratic primary. Plaintiffs Trial Ex. 22, Affidavit of

Theodore S. Arrington, Sept. 6, 1993, Table 4, NAACP v. Schaeffer,

849 F. Supp. 1022 (D. Md. 1994).

4a

TEXAS POLARIZED VOTING

ELECTIONS HELD IN MAJORITY-MINORITY

CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICTS 1992 AND PRE-1992

DISTRICT

15 16 18 20 23 27 28 29 30

% WHITE VOTE

FOR

BLACK/HISPANIC

CANDIDATES

1992

ELECTIONS 37% 33% 29% 25% 16% 50% 0% 5% 64%

PRE-1992

ELECTIONS 22% 30% 24% 6% 9% 27% 7% 5% 15%

* 1992 RESULTS FOR DISTRICTS 27, 28, AND 30 ARE

BASED ON ONE ELECTION.

SOURCE: FINAL REPORT OF DR. ALLAN J. LICHTMAN,

APPENDIX 2, TABLES 1-9, AL VERA ET AL. V. ANN

RICHARDS ET AL.

5a

GEORGIA POLARIZED VOTING

ELECTIONS HELD IN SECOND AND ELEVENTH

CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICTS BLACK VERSUS WHITE

ELECTIONS 1992 AND PRE-1992*

DISTRICT

2ND 11TH

% WHITE VOTE FOR

BLACK/HISPANIC

CANDIDATES *

1992

ELECTIONS 29% 37%

PRE-1992

ELECTIONS 1% 4%

* RESULTS ARE AVERAGES FOR STATEWIDE

ELECTIONS HELD WITHIN THE PRECINCTS OF THE SECOND

AND ELEVENTH DISTRICTS, 1984-1990 AND 1992.

SOURCE: REPORT OF DR. ALLAN J. LICHTMAN, REPORT ON

ISSUES RELATING TO GEORGIA CONGRESSIONAL

DISTRICTS, MAY 26, 1994, TABLES 1-3, DAVIDA JOHNSON,

ET AL. V. ZELL MILLER, ET AL.

6a

LOUISIANA POLARIZED VOTING: 2ND AND 4TH

CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICTS BLACK VERSUS WHITE

CONGRESSIONAL ELECTIONS: 1984 TO 1992

SECOND DISTRICT: BECAME MAJORITY BLACK IN 1990 *

% WHITE VOTE

FOR BLACK

1984

PRIMARY

1990

PRIMARY

1992

PRIMARY

CANDIDATES 8% 44% 74%

FOURTH DISTRICT: BECAME MAJORITY BLACK IN 1992 **

1986 1986 1988 1988 1990 1992

PRIM RUN PRIM RUN PRIM PRIM

% WHITE VOTE

FOR BLACK

CANDIDATES 3% 22% 3% 15% 3% 58%

* THERE WAS ONE BLACK CANDIDATE AND FOUR

WHITE CANDIDATES IN THE 1984 PRIMARY; SIX BLACK

CANDIDATES AND SIX WHITE CANDIDATES; AND TWO

BLACK CANDIDATES AND ONE WHITE CANDIDATE IN THE

1992 PRIMARY. THE SECOND DISTRICT IS BASED IN NEW

ORLEANS AND HAS CONSIDERABLE OVERLAP DURING THE

PERIOD STUDIED HERE. **

** THERE WAS ONE BLACK CANDIDATE AND FOUR

WHITE CANDIDATES IN THE 1986 PRIMARY; ONE BLACK

CANDIDATE AND ONE WHITE CANDIDATE IN THE 1986

RUNOFF; ONE BLACK CANDIDATE AND FOUR WHITE

CANDIDATES IN THE 1988 PRIMARY; ONE BLACK

CANDIDATE AND ONE WHITE CANDIDATE IN THE 1988

RUNOFF; ONE BLACK CANDIDATE AND TWO WHITE

CANDIDATES IN THE 1990 PRIMARY; AND SIX BLACK

7a

CANDIDATES AND TWO WHITE CANDIDATES IN THE 1992

PRIMARY. THE FOURTH DISTRICT IS BASED OUTSIDE OF

NEW ORLEANS AND HAS LIMITED OVERLAP FOR THE

PERIOD BEFORE AND AFTER THE 1992 REDISTRICTING.

SOURCE: DECLARATION OF RICHARD ENGSTROM,

JULY 20, 1994, CHART ONE, RAY HAYS ET AL. V. STATE OF

LOUISIANA, ET AL.

8a

MARYLAND POLARIZED VOTING:

FIFTH AND FOURTH CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICTS:

BLACK VERSUS WHITE CONGRESSIONAL ELECTIONS

PRINCE GEORGE’S COUNTY 1990 & 1992

ELECTION

1990 1992

DEM. PRIMARY DEM. PRIMARY

% WHITE VOTE FOR

BLACK CANDIDATES 0% 44%

* AFTER THE 1990 ELECTION, IN THE POST-1990

REDISTRICTING, THE FIFTH CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT,

BASED IN PRINCE GEORGE’S COUNTY WAS REDRAWN. A

NEW MAJORITY BLACK DISTRICT, THE FOURTH

CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT, WAS CREATED THAT WAS

LARGELY BASED IN PRINCE GEORGE’S COUNTY. IN THE

1990 DEMOCRATIC PRIMARY, BLACK CANDIDATE ABDUL

MUHAMMAD RAN UNSUCCESSFULLY AGAINST

INCUMBENT STENNY HOYER IN THE FIFTH DISTRICT. IN

1992, SEVERAL BLACK AND WHITE CANDIDATES RAN FOR

THE DEMOCRATIC NOMINATION FOR THE OPEN SEAT IN

THE FOURTH DISTRICT. ELECTION RESULTS FOR THE TWO

YEARS ARE FOR PRINCE GEORGE’S COUNTY ONLY.

SOURCE: AFFIDAVIT OF THEODORE S. ARRINGTON,

SEPTEMBER 6, 1993, TABLE 4, NAACP ET AL. V. WILLIAM

DONALD SCHAEFER ET AL.

■