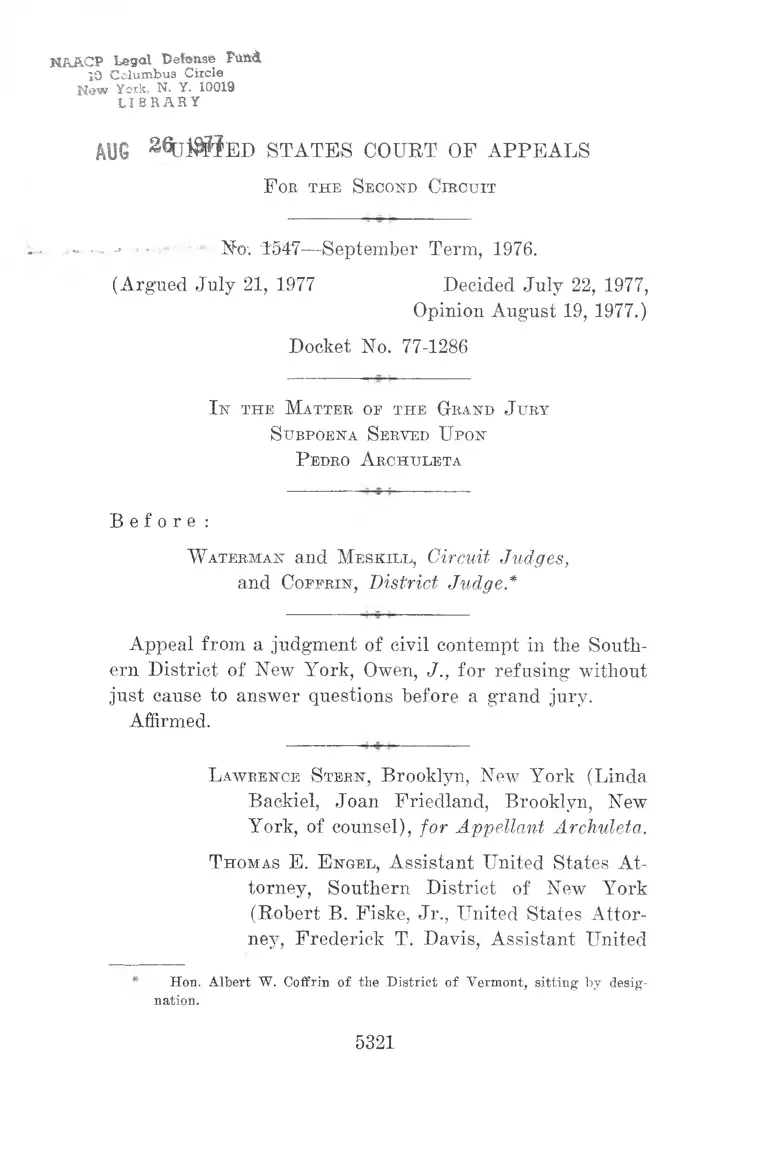

In Re: Pedro Archuleta Grand Jury Subpoena Decision

Public Court Documents

August 26, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. In Re: Pedro Archuleta Grand Jury Subpoena Decision, 1977. b143aa5d-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8653d770-4165-480a-bb4a-da28bc55df9f/in-re-pedro-archuleta-grand-jury-subpoena-decision. Accessed January 30, 2026.

Copied!

NA&CP Legal Defense PtfflA

10 Columbus Circle

Hew York, N. Y. 10019

LI BRARY

MiG 3 % M 'I e D s t a t e s c o u r t o f a p p e a l s

F or t h e S econd C ir c u it

-> No; T547—September Term, 1976.

(Argued July 21, 1977 Decided July 22, 1977,

Opinion August 19, 1977.)

Docket No. 77-1286

I n t h e M atter of t h e Grand J ury

S ubpo en a S erved U po n

P edro A rch u leta

B e f o r e :

W aterm an a n d M e s k il l , Circuit Judges,

a n d C o ffr in , District Judge.*

Appeal from a judgment of civil contempt in the South

ern District of New York, Owen, J., for refusing without

just cause to answer questions before a grand jury.

Affirmed.

L aw rence S t e r n , Brooklyn, New York (Linda

Backiel, Joan Friedland, Brooklyn, New

York, of counsel), for Appellant Archuleta,

T hom as E . E n g el , Assistant United States At

torney, Southern District of New York

(Robert B. Fiske, Jr., United States Attor

ney, Frederick T. Davis, Assistant United

Hon. Albert W. Coffrin of the District of Vermont, sitting by desig

nation.

5321

States Attorney, Southern District of New

York, of counsel), for the United States of

America.

Meskill , Circuit Judge:

Pedro Archuleta, the appellant here, was found to be in

civil contempt for refusing to answer questions put to him

by a grand jury empanelled in the Southern District of

New York. The order of contempt, issued by Judge Owen,

remanded Archuleta until he purged himself of his con

tempt or until the term of the grand jury expires. 28 U.S.C.

§ 1826(a). Because of the time limitation of 28 U.S.C.

§ 1826(b), we affirmed the order of the district court on

July 22, 1977 this opinion explains the basis of our de

cision.

On January 24, 1975, a bomb exploded in Fraunces Tav

ern, a restaurant in New York City. Four people were

killed, and fifty-three were injured. A group known as

Fuerzas Armadas de Liberacion National Puertorriquena,

or “FALN,” which seeks independence for Puerto Rico,

claimed responsibility for this act of terrorism. A number

of subsequent bombings have been traced to the FALN.

In April, 1975, a grand jury was empanelled in the

Southern District of New York to investigate these bomb

ings. The term of that grand jury expired in October,

1976. A second grand jury, empanelled to investigate the

same crimes, is now sitting.

In November, 1976, a “bomb factory” was discovered in

an apartment in Chicago, owned by one Carlos Torres.

Evidence was found there linking Torres, who is now a

1 28 U.S.C. § 1826(b) provides:

Any appeal from an order of confinement under this section shall

be disposed of as soon as practicable, but not later than thirty

days from the filing of such appeal.

5322

fugitive, to the FALN. Searchers also found a letter from

a church in San Antonio, Texas, to Maria Cueto, the Execu

tive Director of The National Commission on Hispanic Af

fairs of The Protestant Episcopal Church. Miss Cueto and

her secretary, Eaisa Nemikin were called before the grand

jury, and refused to testify concerning the whereabouts of

Torres, after being ordered to do so. See In re Wood, 430

F.Supp. 41 (S.D.N.Y. 1977). They were held in civil con

tempt by the district court, and were remanded until they

testified. This Court affirmed the judgment of contempt,

In re Cueto, 554 F.2d 14 (2d Cir. 1977), and they are pres

ently incarcerated.

Shortly after our decision in Cueto, supra, a grand jury

subpoena was served upon the appellant. He had been a

member of The National Commission on Hispanic A ffairs;

he had also been named in various newspaper accounts as

a possible supplier of dynamite to the FALN. Motions to

quash the subpoena were denied by Judge Lasker. Before

the grand jury, he was asked the following questions:

(1) Did you provide dynamite to anyone you knew to

be in a group called the FALN at any time prior

to January 24, 1975?

(2) Do you know the source of dynamite explosives

used at the bombing of Fraunces Tavern?

(3) Do you know anyone who is responsible for the

bombing at Fraunces Tavern?

(4) In early 1968 did you yourself steal any dynamite

from the Heron Dam Project site near Parkview,

New Mexico?

Archuleta invoked his Fifth Amendment immunity, and

refused to testify. The prosecution then applied for, and

obtained, from Judge Brieant, an order of immunity.

5323

Judge Brieant also entered a protective order designed

to avoid public disclosure of the grand jury proceedings.

Thereafter, Archuleta refused a second time to answer

these four questions. After the foreman had expressly

directed him to answer, the questions were asked a third

time. Bather than responding, appellant made a series of

political speeches explaining his refusal to testify. After

polling the jury to determine that they all felt the ques

tions to be “reasonably necessary and proper,” Judge

Brieant directed appellant to testify. When Archuleta

persisted in his contumacious conduct, he was held in con

tempt on June 30, 1977, by Judge Bichard Owen, and re

manded, pursuant to 28 II.S.C. § 1826.

I.

Appellant’s first contention is that the grand jury had no

evidentiary basis upon which to call him. In Blair v. United

States, 250 U.S. 273 (1919), it was stated that a witness

before a grand jury i s :

bound not only to attend but to tell what he knows in

answer to questions framed for the purpose of bring

ing out the truth of the matter under inquiry.

He is not entitled to urge objections of incompetency

or irrelevancy, such as a party might raise, for this is

no concern of his.

Id. at 282. This has continued to be the rule. Becentlv,

Judge Friendly explained:

The safeguards built into the grand jury system, such

as enforced secrecy and use of court process rather

than the constable’s intruding hand as a means of

gathering evidence, severely limit the intrusions into

personal security which are likely to occur outside the

grand jury process. To be sure, on occasion, a grand

5324

jury may overstep bounds of propriety either at its

own or the prosecutor’s instance, and conduct an in

vestigation so sweeping in scope and undiscriminating

in character as to offend other basic constitutional pre

cepts. When this occurs courts are not without power

to a c t . . . . A part from such cases, when the grand jury

has engaged in neither a seizure nor a search, there is

no justification for a court’s imposing even so appar

ently modest a requirement as a showing of “reason

ableness”-—with the delay in the functioning of the

grand jury which that would inevitably entail.

United States v. Doe (Schwarts), 457 F.2d 895 (2d Cir.

1972), cert, denied, 410 U.S. 941 (1973). See Branzburg v.

Hayes, 408 U.S. 665, 701-02 (1972); Hale v. Henkel, 201

U.S. 43, 65 (1906).

The actions of the grand jury here are clearly justified.

The questions asked of Archuleta were narrowly focused

on criminal conduct which had occurred in the Southern

District. His common association with two fugitives sought

by the FB I in connection with a possibly related crime,2 as

well as the newspaper reports of his activities, wrnre fully

sufficient to justify the subpoena. See Branzburg v. Hayes,

supra, at 701-02; Costello v. United States, 350 U.S. 359,

362-63 (1956). Archuleta’s attempt to evade his duty as a

citizen on this ground is without merit.8

2 Arrest warrants for Torres and Oscar Lopez, charging possession of

explosives and unlawful flight, have been issued in Chicago.

Archuleta now complains that he was never asked a question about

the whereabouts of Torres. I t ill becomes a witness who contuma

ciously refused to testify to claim a deprivation of rights based on the

grand jury’s failure to question him further.

3 Archuleta also appears to claim that this grand jury is not interested

in finding the bombers responsible for four deaths, but is merely per

secuting him and those who share his political views. There being no

evidence to support this contention, we consider it groundless.

5325

II.

Archuleta’s second claim is that the questions asked him

in the grand jury were based on illegal electronic surveil

lance, and thus that the contempt order must be vacated

under Gelbard v. United States,, 408 U.S. 41 (1972). This

claim is also without merit.

The appellant made sweeping allegations of illegal wire

tapping before the district court. The evidence marshalled

in support of this was a recitation of difficulties in com

pleting calls, together with strange noises heard on com

pleted calls. There was also an affidavit, from one Mary

Lujan, stating that she had been asked by FB I agents if

she had telephoned Archuleta.

In response, the government produced affidavits from

the Assistant United States Attorney and FB I agents in

charge of the investigation of FALN bombings in New

York. These affiants stated that they were unaware of

any illegal electronic surveillance of Archuleta. A similar

set of affidavits was submitted from federal authorities in

Chicago, where an investigation into related crimes is

underway. Finally, the prosecutor submitted an affidavit

from the person in charge of the records of electronic sur

veillance maintained by the FB I in Washington stating

that a search of those records revealed no electronic sur

veillance of appellant. The appellant now challenges this

response as inadequate and argues that searches of state

and local records in New Mexico, Illinois and New York

were required before he could be held in contempt.

We doubt whether the appellant has made even the

preliminary showing necessary to require the government

to respond to his claim of illegal electronic surveillance.

Some mechanical troubles with a telephone, together with

knowledge of a call easily derived from long distance tele-

5326

phone records/ is such insubstantial evidence that in most

cases it puts no burden on the prosecutor to “affirm or

deny” the existence of wiretapping. See In re Grand Jury

(Vigil), 524 F.2d 209, 214 (10th Cir. 1975), cert, denied,

425 U.S. 927 (1976).

However, if, as the district court held, the showing

made was sufficient to trigger a governmental response,

the answer of the prosecutor was sufficient. As we recently

explained in United States v. Yanagita, 552 F.2d 940 (2d

Cir. 1977):

But even in a grand jury proceeding, upon the gov

ernment’s production of a valid warrant the witness

has been held not to be entitled to a full-blown hear

ing on the legality of the warrant prior to testifying

since “the traditional notion that the functioning of

the grand jury system should not be impeded or inter

rupted could prevail at that time over the witness’

interest . . . .” In re Persico, 491 F.2d 1156, 1160 (2d

Cir. 1974). See also Gelhard v. United States, supra,

408 IJ.S. at 70, 92 S.Ct. 2357 (White, J., concurring).

Similarly, where the questions asked of a grand

jury witness are narrow in scope, an affidavit by the

Assistant United States Attorney in charge of the

grand jury proceeding, as distinguished from an all

agency search, will suffice, since he would know if his

questions were derived from illegal surveillance.

“It must be remembered that any electronic sur

veillance by the government is relevant only if it

is somehow used in formulating questions that the

grand jury intends to ask. Thus, surveillance con

ducted by the government, the results of which were

not known to the agents investigating this case,

4 There is no claim that the FBI knew of the contents of the call.

5327

would not be relevant. . . . I think that the assistant

United States attorney handling a case and the FB I

agent in charge of the investigation of a case are

the two people most likely to know if the fruits of

any electronic surveillance were used to gain in

formation on which the grand jury would base its

questions. Thus, I think that the denial was suffi

cient.” United States v. Grusse, 515 F.2d 157, 159

(2d Cir. 1975) (Lumbard, J., concurring).

In addition, the duty of the government to respond

under % 3504 may vary with the specificity of the

claims raised by the witness. United States v. See,

505 F.2d 845, 856 (9th Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 420 U.S.

992, 95 S.Ct. 1428, 43 L.Ed. 2d 673 (1975); United

States v. Stevens, 510 F.2d 1101 (5th Cir. 1975).

Id. at 944. See Gelbard v. United States, 408 U.S. 41, 71

(1972) (White, J., concurring). (“Of course, where the

Government officially denies the fact of electronic surveil

lance of the witness, the matter is at an end and the witness

must answer.”) The standard set out in Tanagita was fully

complied with. The questions put to Archuleta were nar

rowly focused on specific criminal activity. I t was thus

relatively simple for the prosecutor to determine the evi

dentiary basis for the questions. In response to vague,

sweeping charges of wiretapping, the government re

sponded with specific, factual denials of illegal conduct.

Gelbard requires no more.6

5 After oral argument, Archuleta’s counsel submitted a letter to the

Court alleging that the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms

("AFT”) was also investigating the FALN. He now demands that

appellant be released until an affidavit is secured from ATF denying

any illegal electronic surveillance.

Assuming, arguendo, that ATF has actively investigated this case,

our decision is not affected. Gelbard and Tanagita focus the investi

gation of "taint” on the particular questions put to the witness. Here,

5328

III.

Archuleta has also challenged the racial and ethnic com

position of the grand jury.6 All parties agree that this

grand jury was selected by procedures which complied with

the Ju ry Selection and Service Act of 1968, 28 U.S.C.

§ 1861 et seq. The vague, conclusory allegations of under

representation of Hispanics made by Archuleta do not even

make out a colorable claim of a constitutional violation,

let alone a substantial and prejudicial exclusion of mi

nority jurors. Absent such a showing, this jury, selected

in accordance with a valid law, is not subject to attack.7

United States v. Bennet, 539 F.2d 45, 55 (lOtli Cir. 1976),

cert, denied,----- U.S. ------- (197—).

the Assistant United States Attorney, who knows the source of his own

questions, denied any knowledge of electronic surveillance. This meets

the requirements of Gelbard and Tanagita in this ease.

6 Archuleta made the same challenge when called before a grand jury

in the Northern District of Illinois. The district court there rejected

the challenge on the merits.

7 The appellant concedes that he has no statutory standing to mount

this challenge under 28 U.S.G. § 1867. He relies exclusively on his con

stitutional challenge. The government vigorously urges that Archuleta

lacks any standing to raise this claim. In re Maury Santiago, 533 F.2d

727 (1st Oir. 1976), so held, citing United States v. Duncan, 456 F.2d

1401, 1403-04 (9th Cir.), vacated for reconsideration of other matters,

409 U.S. 814 (1972). See Blair v. United States, 250 U.S. 273, 282

(1919).

However, in United States ex rel. Chestnut v. Criminal Court, 442

F.2d 611 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 856 (1971), relied on by

Archuleta, a footnote indicated that a witness before a state grand

jury had standing to challenge its composition. Id. at 615 n.7. How

ever, that grand jury had the power to institute criminal contempt

charges, which it had done. Here, by contrast, we are dealing with a

civil contempt initiated by the United States Attorney. The Chestnut

court focused on these powers of the grand jury, which are unavailable

in federal practice. While we do not decide the issue, the footnote in

Chestnut appears to be a weak reed for any future challenge by a

witness to the grand jury array. Moreover, Chestnut resolved the sub

stantive issue against the eontemnor on the ground that the jury selec

tion procedure was fair, and created no prejudice, even if some groups

were under-represented.

5329

IY.

Archuleta’s final point of any substance is a claim that

his conduct is justified because of newspaper stories con

cerning the FALN, which have appeared during the in

vestigation of the bombings. Apparently, his theory is

that anything he might say in the grand jury might be

disclosed by the jurors or the prosecutor, who may have

“leaked” the material already published.8 His ostensible

concern is that some of this testimony would thus reach

the Chicago grand jurors who are also investigating FALN

bombings. Archuleta is a “target” of that grand jury

investigation.

I t is self-evident that no breach of grand jury secrecy

concerning Archuleta has occurred to date, since he has

refused to answer any questions. The government has

supplied affidavits denying that any breach of grand jury

secrecy was the basis for the articles mentioned. Nor is

there any reason to believe that the jurors or the prose

cutor will violate their oaths, and invade the secrecy of

the proceedings. Appellant’s speculation does not provide

a justification for his contumacious conduct. If such vio

lations do occur, the district court has adequate powers

to remedy the situation.

The remainder of Archuleta’s many claims, consisting

largely of wholly unwarranted attacks on various federal

judges and prosecutors, are not worthy of discussion. The

judgment of civil contempt is affirmed.

The Department of Justice is now investigating those disclosures.

We assume that they will take appropriate measures against those

responsible.

5330

480-8-22-77 . TJSCA—4221

MEIIEN PRESS INC., 445 GREENWICH ST„ NEW YORK, N. Y. 100)3, {212) 966-4177

<7§s||||sĵ *« 219