Rivers v Roadway Express Petition for A Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

December 2, 1992

62 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rivers v Roadway Express Petition for A Writ of Certiorari, 1992. a222b286-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8662b1c4-d0fb-4f72-be43-8446570a032c/rivers-v-roadway-express-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

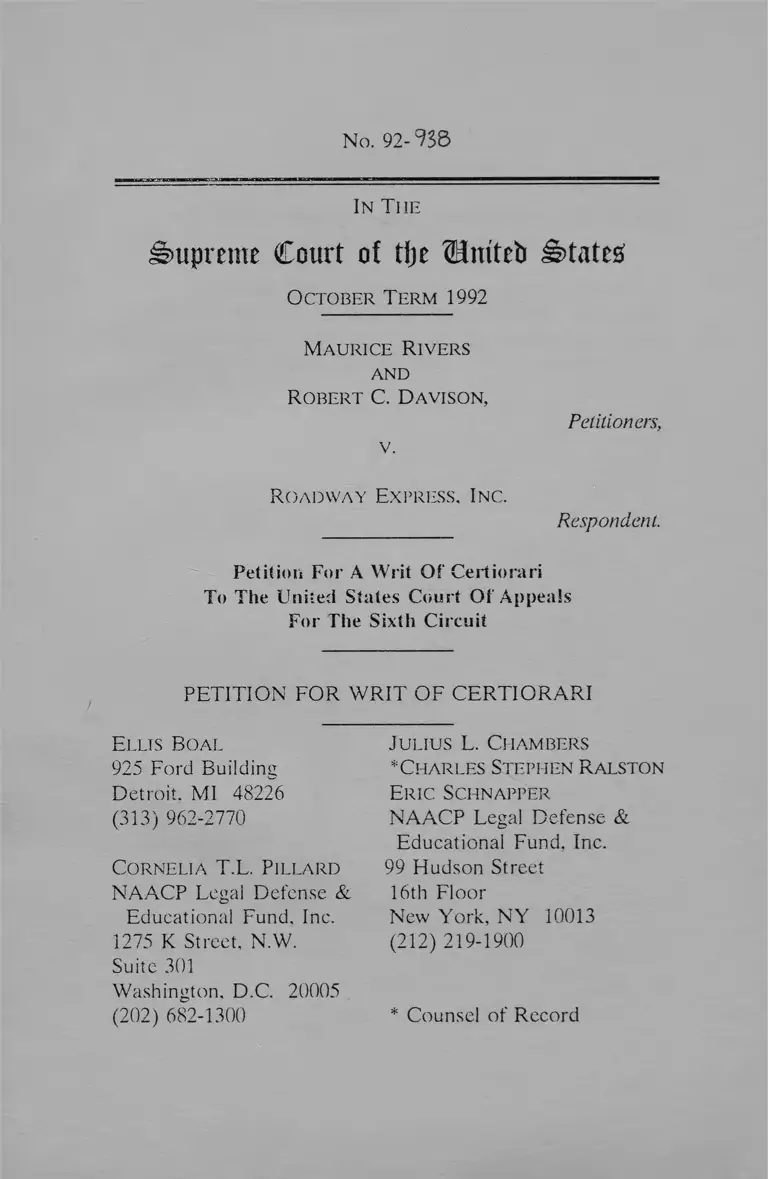

No. 92-938

In The

uprente Court of tfje Hm teb

October Term 1992

Maurice Rivers

AND

Robert C. Davison,

Petitioners,

v.

Roadway Express, Inc.

Respondent.

Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari

To The United States Court Of Appeals

For The Sixth Circuit

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Ellis Boal

925 Ford Building

Detroit. MI 48226

(313) 962-2770

Cornelia T.L. Pillard

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund. Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington. D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Julius L. Chambers

^Charles Stephen Ralston

Eric Sci-inapper

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund. Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

* Counsel of Record

1

Questions Presented

1. Does the Civil Rights Act of 1991 apply to cases

that were pending when the Act was passed?

2. Should this Court’s construction of 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981 in Patterson v. McLean Credit Union be applied

retroactively after it has been legislatively rejected by section

101 of the Civil Rights Act of 1991?

11

List of Parties

The parties are the petitioners Maurice Rivers and

Robert C. Davison and the respondent Roadway Express, Inc.

James T. Harvis, Jr. was an appellant below in a separate

appeal, his claims having been severed by the district court

from those of Rivers and Davison and tried separately. Local

20, International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Chauffeurs,

Warehousemen, and Helpers of America was a defendant in

the district court, but the district court by order dated

November 30, 1988 dismissed all claims against the defendant

union, and that dismissal was not appealed. Neither Harvis

nor Local 20 is a party to this petition.

Ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Questions P resen ted ............................................................. i

List of Parties ...................................................................... ii

Table of A uthorities............................................................. v

Opinions B e lo w .................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ........................................................................... 2

Statute Involved.................................................................... 2

Statement of the Case ........................................................ 3

Reasons for Granting the W r i t .......................................... 5

I. There Is a Conflict Among the Circuits

Regarding Whether the Language of the

Civil Rights Act of 1991 Requires Its

Application to Cases Pending at the

T ime of its Pa s s a g e ............................................. 8

A. There is a Circuit Conflict Over

the Basic Rules for Construing

Statutory Language..................................... 9

B. There is a Circuit Conflict Over

the Role of Legislative Language

and History in Statutory Inter

pretation ................................................... 13

IV

II. There Is a Conflict Among the Circuits

Regarding Whether New Legislation, Such

as § 101 of the 1991 Civil R ights Act,

Should Be Presumed Applicable To Pre-

Act Claims ................... ............. .. 15

A. There are Conflicting Presumptions

Under Bradley v. Richmond School

Board and Bowen v. Georgetown

University Hospital....................... 15

B. There is a Conflict Over Whether

Retroactivity is Determined by

Reviewing the Act as a Whole or

by Reviewing the Section at

Issue .................................................... 20

III. Under the Court’s Prior Decisions, the

Construction of 42 U.S.C. § 1981 in

Pa t t e r s o n v. M c L e a n C r e d i t Un i o n Should

Not Be Applied Retroactively After

Congress Expressly Rejected It . . . . . . . . 21

Conclusion................................... 26

Appendix la-24a

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES PAGES

Bailes v. United States,

cert, denied, 118 L. Ed. 2d 419 (1992)

(No. 91-1075) .................................................................... 17

Baker v. Gulf & Western,

(11th Cir., cert, petition filed Sept. 24, 1992)

(No. 92-552)...................................................................... 7

Baynes v. AT&T Technologies, Inc.,

976 F.2d 1370 (11th Cir. 1992) .............. 6, 8, 12, 16, 17

Beisler v. Commissioner o f Internal Revenue,

814 F.2d 1304 (9th Cir. 1987) ........................................ 11

Bowen v. Georgetown University Hospital,

488 U.S. 204 (1988) ................................................. 15-21

Bradley v. Richmond School Board,

416 U.S. 696 (1974) ............................................... 15 - 21

Chevron Oil Co. v. Huson,

404 U.S. 97 (1971) ................................................. 21 - 25

Colautti v. Franklin,

439 U.S. 379 (1979) ........................................................ 10

Connecticut National Bank v. Germain,

112 S. Ct. 1146 (1992)...................................................... 13

Davis v. City and County o f San Francisco,

No. 91-15113, 1992 WL 251513

(9th Cir. Oct. 6, 1992) 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 16

VI

EEOC v. Arabian American Oil Co.,

I l l S. Ct. 1227 (1991)................................... .. 6

Fray v. Omaha World Herald Co.,

960 F.2d 1370 (8th Cir. 1992) ................ 7, 8, 14, 16, 17

Gersman v. Group Health Assn. Inc.,

975 F.2d 886 (D.C. Cir., 1992)___ 6, 7, 8, 13, 14, 16, 17

Harvis v. Roadway Express,

973 F.2d 490 (6th Cir. 1992) ....................... . . . . . . . . 1

James B. Beam Distilling Co. v. Georgia,

111 S. Ct. 2439 (1991)............................................ 21 - 25

Johnson v. Uncle Ben’s, Inc.,

965 F.2d 1363 (5th Cir., 1992)

(cert, petition filed Sept. 29)

(No. 92-737)......... '. ........................6, 7, 8, 14, 16, 19, 20

Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp. v. Bonjomo,

494 U.S. 827 (1990) ................................... .. 12, 13, 16, 19

Kungys v. United States,

485 U.S. 759 (1988) ................................... 10

Landgraf v. USI Film Products,

968 F.2d at 432 (5th Cir. 1992),

cert, petition filed Oct. 28, 1992)

(No. 92-757)............................................ 6, 16, 17, 19, 20

CASES PAGES

Library o f Congress v. Shaw,

478 U.S. 310 (1986) . . . 6

Lorance v. AT&T Technologies, Inc.,

490 U.S. 900 (1989) ........................................................ 6

Luddington v. Indiana Bell Telegraph Co.,

966 F.2d 225 (7th Cir. 1992) ......... 5,1,%, 11, 12, 15, 16

Lytle v. Household Manufacturing, Inc.,

494 U.S. 545 (1990) ............................................ ........... 4

Martin v. Wilks,

490 U.S. 755 (1989) ........................... 6

Mountain States Telegraph & Telegraph Co.

v. Pueblo o f Santa Ana,

472 U.S. 237 (1985) ........................................................ 10

Mozee v. American Commercial Marine Svc. Co.,

963 F.2d 929 (7th Cir. 1992),

cert, denied 113 S. Ct. 86 (1992)......... 7, 8, 14, 15, 16, 17

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union,

491 U.S. 164 (1989) ............................................ passim

Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins,

490 U.S. 228 (1989) ...................................................... 6

Russello v. United States,

464 U.S. 16 (1983) .......................................................... 11

South Carolina v. Catawba Indian Tribe, Inc.,

476 U.S. 498 (1986) ................................................... 11

vii

CASES PAGES

Thorpe v. Housing Authority o f Durham,

393 U.S. 268 (1969) .......................... 19

via

United States v. Security Indust. Bank,

459 U.S. 70 (1982)......... ......................... ......................... 21

United States v. Menasche,

348 U.S. 528 (1955) .......................... .................. ...........n

United States v. Nordic Village, Inc.,

112 S. Ct. 1011 (1992) ...................................................... 11

United States v. Wong Kim Bo,

472 F.2d 720 (5th Cir. 1972) _____ . . . . . . ____ . . . . 11

Vogel v. City o f Cincinnati,

959 F.2d 594 (6th Cir. 1992)

cert, denied, 113 S. Ct. 86

(1992)................................................... 8, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17

Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio,

490 U.S. 642 (1989) .............................. .. 6, 10

West Virginia University Hospitals v. Casey,

111 S. Ct. 1138 (1991)....................... ......................... 6

STATUTES

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) ..................................... ....................... 2

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ...........................................................passim

Civil Rights Act of 1991, 105 Stat. 1071, P.L. 102-166passim

Education Amendments of 1972,

Pub. L. No. 92-318, 1972 U.S.C.C.A.N. (86 Stat.) . . . . 20

CASES PAGES

IX

PAGES

MISCELLANEOUS

Brief for Respondent, Ayala-Chavez v. I.N.S.,

No. 91-70262 (9th C ir .) ............................................... . . 18

Brief of Plaintiff-Appellant Federal Deposit Insurance

Corporation, Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. v. Wright,

No. 90-2217 (7th C ir .) ......................................................18

Defendant’s Memorandum in Opposition to Plaintiffs Motion

to File Second Amended Complaint, Van Meter v. Barr,

Civil Action No. 91-0027 (G A G )......................................19

Reply Brief of the United States to Opposition Briefs,

United States v. Allied Corp.,

Civil No. C-83-5898 FMS (N .D .C al.)...............................18

Response of the United States to Defendants’ Motion to

Strike Claims for Damages and Penalties,

United States v. Rent America,

No. 89-6188-PAINE (S.D.Fla.) ........................................ 18

United States as Amicus Curiae, Davis v. Tri-State Mack

Distribution, Nos. 91-3574, 92-1123 (8th C ir .) .................19

United States Reply to Defendants’ Oral Motion to Dismiss,

United States v. Cannon, Civil Action No. 6:91-951-3K

(D.S.C.) ................................................................................18

No. 92-

In The

Supreme Court of tfje Untteb States;

October Term 1992

Maurice Rivers

and

Robert C. Davison,

Petitioners,

v.

Roadway Express, Inc.

Respondent.

Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari

To The United States Court of Appeals

For The Sixth Circuit

Petitioners Maurice Rivers and Robert C. Davison

respectfully pray that the Supreme Court grant a writ of

certiorari to review the judgment of the United States Court

of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit entered on August 24, 1992.

The Court of Appeals denied a timely petition for rehearing

on October 13, 1992.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Sixth Circuit is reported as Harvis

v. Roadway Express, Inc., 973 F.2d 490 (6th Cir. 1992), and is

set out at la-16a of the Appendix hereto ("App."). The order

of the Court of Appeals denying respondent’s petition for

rehearing and for rehearing en banc is unreported and is

2

set out at App. 17a-18a. The opinion of the United States

District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, Western

Division, is unreported, and is set out at App. 19a-24a.

Jurisdiction

The decision of the Sixth Circuit was entered August

24, 1992. Respondent’s timely petition for rehearing en banc

was denied on October 13, 1992. This Court has jurisdiction

to hear this case pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

Statute Involved

This case involves sections 101, 109(c), 402(a) and

402(b) of the Civil Rights Act of 1991, 105 Stat. 1071, P.L.

102-166, which provide in pertinent part:

Sec. 101. Prohibition Against All Racial

D iscrimination in the Making and Enforcement of

Contracts.

Section 1977 of the Revised Statutes (42 U.S.C. 1981)

is amended —

(1) by inserting "(a)" before "All persons within";

and

(2) by adding at the end the following new

subsections:

"(b) For purposes of this section, the term ’make

and enforce contracts’ includes the making, performance,

modification, and termination of contracts, and the enjoyment

of all benefits, privileges, terms, and conditions of the

contractual relationship.

3

"(c) The rights protected by this section are

protected against impairment by nongovernmental

discrimination and impairment under color of State law."

Sec. 109. Pr o t e c t io n of E x t r a t e r r it o r ia l

Employment.

(c) Applicatio n of Am endm ents.—The

amendments made by this section shall not apply with respect

to conduct occurring before the date of the enactment of this

Act.

Sec. 402. Effective Date.

(a) In General.—Except as otherwise specifically

provided, this Act and the amendments made by this Act

shall take effect upon enactment.

(b) Certain Disparate Impact Cases.—

Notwithstanding any other provision of this Act, nothing in

this Act shall apply to any disparate impact case for which a

complaint was filed before March 1, 1975, and for which an

initial decision was rendered after October 30, 1983.

Statement Of The Case

Petitioners Maurice Rivers and Robert C. Davison,

experienced Black garage mechanics, seek certiorari on the

issue whether section 101 of the Civil Rights Act of 1991

applies to their claims of race discrimination in employment

against their former employer, Roadway Express, Inc.

("Roadway," "the Company"). Rivers and Davison worked

successfully for Roadway from 1972 and 1973, respectively,

until they were discharged in 1986. On August 22, 1986,

without the contractually required prior written notice

routinely provided to white employees, Roadway managers

4

told Rivers and Davison to attend disciplinary hearings on

their accumulated work records. Both petitioners refused to

attend because of the inadequate notice. Both were

disciplined in their absence. They filed successful grievances

complaining of the peremptoiy, racially discriminatory

disciplinary proceedings. In retaliation for their success in

the grievance proceedings, however, Roadway again convened

disciplinary hearings, again without the requisite notice, and

discharged the petitioners on September 26, 1986 after they

refused to attend. App. 2a-3a.

The district court initially denied Roadway summary

judgment on the race discrimination claims, but then

dismissed petitioners’ § 1981 discharge and retaliation claims

based on this Court’s subsequent decision in Patterson v.

McLean Credit Union. 491 U.S. 164 (1989). App. 23a-24a.

The Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit reversed, and

reinstated the claims of racially discriminatory retaliation.

The Court of Appeals held that Patterson applies

retroactively, but that the retaliation claims survive Patterson

because § 1981 protects the right to "enforce contracts," and

petitioners’ "ability to enforce claimed contract rights was

impaired because of their race." App. 8a. The Sixth Circuit

thus remanded the retaliation claims for a jury trial, and

directed a redetermination of the Title VII claims in light of

the jury’s verdict as required by Lytle v. Household Mfg., Inc.,

494 U.S. 545 (1990). App. 9a-10a.

The Court of Appeals affirmed the dismissal of the

claims of race discrimination in firing, however, on the

ground that the Civil Rights Act of 1991 should not be

applied to this case. App. lla-14a. On remand under

Patterson, as applied in this case by the Sixth Circuit, plaintiffs

must prove race-based retaliation relating to their exercise of

a contract right. App. 14a. If § 101 of the 1991 Act applied

or if the decision in Patterson were held no longer to apply

5

retroactively, however, proof of race discrimination in any

aspect of the employment relation would entitle the

petitioners to relief.

Reasons For Granting The Writ

The question whether any provision of the 1991 Civil

Rights Act applies to pre-Act claims has created a number of

distinct conflicts in the Circuits. The Circuits are in conflict

over whether the plain language of the 1991 Civil Rights Act

commands its application to pending cases, because they

disagree on the applicable rules of statutory construction.

The Circuits are also in conflict over whether, if the statutory

language is not determinative, the decisions of this Court

create a presumption that § 101 of the Act applies. This

conflict is so well developed that the Courts of Appeals have

repeatedly expressly referred to it, and even requested

clarification from this Court. Even among those courts

holding § 101 presumptively inapplicable, there is a split over

whether the question is properly analyzed as one of

applicability of the 1991 Act as a whole, or whether it should

be approached section by section. Finally, there is an

unresolved question under this Court’s own precedent

whether, in light of the 1991 Act’s repudiation of Patterson,

that decision should continue to be applied retroactively to

pending claims.

This case presents issues of great national importance.

Hundreds of judicial decisions have grappled with the

question whether the 1991 Act applies to pre-Act claims, and

hundreds more have sought to apply the correct presumption

regarding the applicability of other new statutes to pending

6

cases.1 The conflicts in the law have led to inconsistent

results among jurisdictions. Moreover, the United States

government, in cases in the lower courts nationwide, is filing

conflicting briefs, some supporting and other opposing a

presumption that new legislation applies to pre-existing

claims. If current experience is any guide, some civil rights

cases filed prior to the 1991 Act will continue to be litigated

for several years, and it is thus important for this Court to set

forth clearly which legal standards will govern those cases.* 1 2

The questions here presented must be resolved in order to

ensure that the current inequities and waste of judicial

resources not persist into the next decade.

1 Indeed, the Seventh Circuit in Lucldington v. Indiana Bell

Telephone Co. commented that the applicability of the 1991 Civil Rights

Act was of such great importance that, even though it had already been

decided by another panel of the Seventh Circuit, the Lucldington panel

would discuss it "as if it were an open question in this circuit, rather than,

as we would ordinarily do, dispose of it with a citation to our recent

decision." 966 F.2d 225, 226 (7th Cir. 1992).

1 Employment discrimination cases unfortunately often take years

to resolve. In the eight cases in which Supreme Court decisions were

overturned by the 1991 Act, for example, the employment discrimination

claim at issue was nine years old on average by the time the litigation

reached this Court. Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 491 U.S. 164 (1989)

(plaintiff harassed 1972-1982, fired 1982); Wards Cove Packing Co. v.

Atonio, 490 U.S. 1642 (1989) (filed in 1974); Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins,

490 U.S. 228 (1989) (plaintiff denied partnership in 1982); EEOC v.

Arabian American OH Co., I l l S.Ct. 1227 (1991) (plaintiff dismissed in

1974); Martin v. Wilks, 490 U.S. 755 (1989) (original suit filed in 1974;

disputed consent decree entered in 1981); Lorance v. AT&T Technologies,

Inc., 490 U.S. 900 (1989) (seniority system adopted in 1979; plaintiff laid

off in 1982); West Virginia Univ. Hospitals v. Casey, 111 S.Ct. 1138 (1991)

disputed practice occurred in January 1986); Libraty o f Congress v. Shaw,

478 U.S. 310 (1986) (Title VII complaints filed in 1976 and 1977).

7

Other petitions for certiorari have already been filed

with the Court addressing the applicability of various

provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 to pending claims.

Baker v. Gulf & Western No. 92-552 (11th Cir., cert, petition

filed September 24, 1992); Johnson v. Uncle Ben’s, No. 92-737

(5th Cir., cert, petition filed September 29); Landgraf v. USI

Film Products, No. 92-757 (5th Cir., cert, petition filed

October 28, 1992); Kuhn v. Island Creek Coal Co., No. 92-787

(6th Cir., cert, petition filed November 3, 1992). This case is

the best vehicle for deciding the common issues for at least

three reasons. First, the largest segment of pending cases in

the lower courts raising the question whether the 1991 Act

applies are cases seeking application of § 101.3 That is the

provision at issue here, but it is not addressed in Landgraf or

Kuhn. Second, the court below, unlike the courts in Uncle

Ben’s and Landgraf, analyzed the applicability of the 1991 Act

as a whole, rather than section by section. Given the

importance of the procedural or substantive nature of the

individual statutory provision at issue to the determination

whether the change applies to pre-Act claims, the decision of

the court below reviewing the Act as a whole specially

warrants review. Third, petitioner in Landgraf seeks

application of the procedures and remedies afforded by the

1991 Act to claims that were fully adjudicated prior to the

Act under then-current procedures and remedies. This case

was reversed and a remand directed on other grounds, and

therefore will be retried in any event, and application of the

3 See, e.g., Baynes r. AT&T Technologies, Inc., 976 F.2d 1370 (11th

Cir., 1992); Gersnian i>. Group Health Ass’n., Inc., 975 F.2d 886 (D.C. Cir.,

1992); Johnson i\ Uncle Ben’s, Inc., 965 F.2d 1363 ( 5th Cir., 1992);

Luddington v. Indiana Bell Tel. Co., 966 F.2d 225; Mozee v. American

Commercial Marine Svc. Co., 963 F.2d 929 (7th Cir. 1992), cert, denied,

__U .S .___ , 113 S.Ct. 207 (1992); Fray v. Omaha World Herald Co., 960

F.2d 1370 (8th Cir. 1992).

8

1991 Act’s procedures and remedies is thus more appropriate

here.

By separate motion, petitioners respectfully request

that this petition be considered jointly with the petitions

already filed in Johnson, Baker, Landgraf and Kuhn.

I. There is a Conflict Among the Circuits

Regarding Whether the Language of the

Civil Rights Act of 1991 Requires its

Application to Cases Pending at the Time

of its Passage

The Sixth Circuit in this case, as well as the Fifth,

Seventh, Eighth, Eleventh and District of Columbia Circuits,

have ruled that the language of the 1991 Civil Rights Act

does not indicate whether it applies to pending cases. Harvis

v. Roadway Express, App. 12a (following Vogel v. City o f

Cincinnati, 959 F.2d 594, 597 (6th Cir. 1992) cert, denied, _

U.S. __, 113 S.Ct. 86 (1992)); Johnson v. Uncle Ben’s, Inc.,

965 F.2d at 1372-73 (5th Cir. 1992); Luddington v. Indiana

Bell Telephone Co., 966 F.2d at 227 (7th Cir. 1992); Fray v.

Omaha World Herald Co., 960 F.2d 1370, 1376 (8th Cir.

1992); Baynes v. AT&T Technologies, Inc., 976 F.2d 1370, 1992

WL 296716, at *1 (11th Cir., Oct. 20, 1992); Gersman v.

Group Health Ass’n., Inc., 975 F.2d 866, 888-890 (D.C.Cir.

1992). The Ninth Circuit disagreed, holding that "the

language of the Act reveals Congress’ clear intention that the

majority of the Act’s provisions be applied to cases pending

at the time of its passage." Davis v. City and County o f San

Francisco, No. 91-15113, 1992 WL 251513 (9th Cir. Oct. 6,

1992). There is thus a conflict in the Circuits requiring

resolution by this Court.

The conflict regarding whether the language of the

1991 Civil Rights Act by its terms applies to pre-Act cases

9

turns on basic rules of statutory interpretation generally

applicable to all types of legislation. The issue thus has

implications far beyond civil rights litigation, and sweeps

more broadly even than the question of statutory retroactivity.

The Circuits disagree over the continued viability of

fundamental rules and methods of statutory construction.

A. There is a Circuit Conflict Over the Basic

Rules for Construing Statutory Language

In determining whether the Civil Rights Act of 1991

applies to pre-Act claims, the Circuits arrived at diametrically

opposing conclusions from the same statutory terms. The

Ninth Circuit in Davis found dispositive the language of

§§ 402(a), 402(b) and 109(c). Section 402(a), entitled

"Effective Date -- In General", provides:

Except as otherwise specifically provided, this

Act and the amendments made by this Act

shall take effect upon enactment.

The Davis court examined the two statutory subsections that

expressly do "otherwise specifically provide[]..." and confirmed

by negative inference that § 402(a)’s mandate that the Act

"take effect upon enactment" includes application to pending,

pre-Act claims. One of the exceptions to the general

applicability rule in § 402(a) is found in § 402(b), entitled

"Effective Date -- Certain Disparate Impact Cases." Section

402(b) states:

Notwithstanding any other provision of this

Act, nothing in this Act shall apply to any

disparate impact case for which a complaint

was filed before March 1, 1975, and for which

an initial decision was rendered after October

30, 1983.

10

Section 402(b) ensures that the Act shall not apply

retrospectively to the Wards Cove case. The other exception

to § 402(a) is § 109(c), entitled "Protection of Extraterritorial

Employment -- Application of Amendments." Section 109(c)

provides that:

The amendments made by this section [§ 109] shall

not apply with respect to conduct occurring before the

date of the enactment of this Act.

Section 109(c) provides that the amendments giving the Act

extraterritorial reach do not apply to pre-Act conduct.4

The Ninth Circuit in Davis found that the text of the

1991 Act is clear. The "directives from Congress that in two

specific instances [§§ 402(b) and 109(c)] the Act not be

applied to cases having to do with pre-Act conduct provide

strong evidence of Congress’ intent that the courts treat other

provisions of the Act as relevant to such cases." Davis, 1992

WL 251513, at * 14. The court in Davis concluded that

"[t]here would have been no need for Congress to provide

that the Act does not pertain to the pre-passage activities of

the Wards Cove company, see Section 402(b), or of American

businesses operating overseas, see Section 109(c), if it had not

viewed the Act as otherwise applying to such conduct." Id.

4 The Ninth Circuit also considered §§ 2 and 3, which include

Congress’ finding that Wards Cove Packing Co. i\ Atonio, 490 U.S. 642

(1989), "has weakened the scope and effectiveness of federal civil rights

protection," and Congress’ desire to "codify the concepts of ’business

necessity’ and ’job related’ enunciated in ... Supreme Court decisions prior

to Wards Cove..." and to "respond to recent decisions of the Supreme

Court ...." Davis 1992 WL 251513, at *14. According to the Ninth Circuit,

these provisions show "Congress’ sense that the Supreme Court had

constricted the Nation’s civil rights laws so as to afford insufficient redress

to those who have suffered job discrimination," and therefore support

application of the new Act to pending claims. Id. at *15.

11

In thus construing the 1991 Act, Davis applied the rule

that "a statute should be interpreted so as not to render one

part inoperative." See Davis 1992 WL 251513, at *14 {citing

South Carolina v. Catawba Indian Tribe, Inc., 476 U.S. 498,

510 n. 22 (1986), quoting Colautti v. Franklin, 439 U.S. 319,

392 (1979).5 This well established principle was reaffirmed

in United States v. Nordic Village, Inc., 112 S. Ct. 1011, 1015

(1992) (holding that "a statute must, if possible, be construed

in such a fashion that every word has some operative effect").

The other Circuits, however, including the court below, have

declined to apply this rule, thus creating conflicts both among

the Circuits and with this Court’s clear mandate.

The Davis court also relied on the rule of construction

that "where Congress includes particular language in one

section of a statute but omits it in another section of the

same Act, it is generally presumed that Congress acts

intentionally and purposely in the disparate inclusion or

exclusion." Davis at *14, {quoting Russello v. United States,

464 U.S. 16, 23 (1983), quoting United States v. Wong Kim Bo,

472 F.2d 720, 722 (5th Cir. 1972)). The other Circuits

disregarded this rule in determining whether the 1991 Act

applies to pre-Act claims and, again, are in conflict with the

Ninth Circuit and this Court.

In disregarding the rules of statutory construction

applied in Davis, each of the other Circuits that have

considered the issue have not found the statutory language

For this proposition, the court in Davis also cited Kuiigys v. United

Slates, 485 U.S. 759, 778 (1988) (plurality opinion of Scalia, J.); Mountain

States Tel. & Tel. Co. v. Pueblo o f Santa Ana, 472 U.S. 237, 249-50 (1985)

[quoting Colautti)-, United States v. Menasclie, 348 U.S. 528, 538-39 (1955)

[quoting Montclair v. Ramsdell, 107 (17 OFIO) U.S. 147, 152 (1883)); and

Beisler v. Commissioner o f Internal Revenue, 814 F.2d 1304, 1307 (9th Cir.

1987) (tui banc).

12

conclusive. Some Circuits have simply disregarded §§ 402(b)

and 109(c) without comment about the clear inference those

sections create. The Sixth Circuit in Vogel did not consider

§§ 402(b) and 109(c) in construing the statute, found § 402(a)

alone insufficiently clear, and turned directly to the legislative

history, which it found to be inconclusive. 959 F.2d at 598.

The Seventh Circuit in Luddington did likewise. 966 F 2d at

227.

The Eleventh Circuit in Baynes did not specifically

discuss any of the Act’s language, but simply remarked that

"[t]he Civil Rights Act of 1991 does not say whether it applies

retroactively or prospectively." Baynes, at *1. Baynes thus

appears to demand an express general statement using the

words "prospective" or "retroactive" — a level of explicitness

far beyond what this Court has previously demanded. In

Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp. v. Bonjomo, 494 U.S. 827,

838 (1990), the Supreme Court held that the plain language

of the provision of the Federal Courts Improvement Act of

1982 that amended the federal postjudgment interest statute

was on its face clearly inapplicable to judgments entered

before its effective date. 494 U.S. at 838. The Court relied

on (a) a statutory reference to the calculation of interest

"from the date of the entry of the judgment....," 494 U.S. at

838, and (b) the reference to "the rate" and "a rate" of

interest, id., which the Court took to mean that a single rate

should be applied, and that it should be the rate that was in

effect on the date of entry of the judgment. Id. The

inferences to be drawn from §§ 402(b) and 109(c) are more

straightforward than those this Court in Bonjomo held were

facially clear. In demanding a more express statement,

Baynes represents a new approach to statutory construction

inconsistent with this Court’s own precedent.

13

B. There is a Circuit Conflict Over the Role of

Legislative Language and History in Statutory

Interpretation

In addition to the conflict among the Circuits about

how to read the statute’s plain language, the Circuits disagree

over the role that legislative history plays in statutory

construction. Several of the Circuits that found the text

inconclusive did so by drawing on the admittedly unclear

legislative history of the 1991 Act in order to inject some

ambiguity into the statutory language. The Ninth Circuit in

Davis followed this Court’s recent pronouncement in

Bonjomo that "[t]he starting point for interpretation of a

statute ’is the language of the statute itself. Absent a clearly

expressed legislative intention to the contrary, that language

ordinarily must be regarded as conclusive.’" 494 U.S. at 835

{quoting Consumer Prod. Safety Comm’n v. GTE Sylvania,

Inc.. 447 U.S. 102. 108 (1980)). This Court just last Term in

Connecticut Nat’l Bank v. Germain, 112 S. Ct. 1146, 1149

(1992), reaffirmed that "courts must presume that a

legislature says in a statute what it means and means in a

statute what it says there." The other Circuits, however,

failed to apply this principle, thus generating an additional

inter-circuit conflict.

The District of Columbia Circuit in Gersman, for

example, rejected the statutory language argument that was

determinative in Davis by drawing selectively on remarks in

floor debates by legislators opposed to retroactivity, including

Senators Dole, Danforth, and Gorton, and Representative

Hyde. In light of such legislative history, the court in

Gersman concluded that the language of the statute on its

face was unclear, and "one might view these two subsections

14

[402(b) and 109(c)] not as redundancies, but rather as

insurance policies." Gersman, 975 F.2d at 890.6

The court below considered § 402(a) in isolation, and

held that it "could mean that the Act applies to pending cases

or it could mean it should be applied only to conduct

occurring as of that date of enactment." App. at 12a. In an

approach similar to that of the District of Columbia Circuit

in Gersman, the court then quoted at length from the Eighth

Circuit’s analysis in Fray of the legislative history to conclude

that §§ 402(b) and 109(c) do not in fact have any

independent significance, but are only "hedged ... bets" by the

minority in Congress that opposed retroactivity. App. at 13a

(quoting Fray, 960 F.2d at 1377).

Other Circuits, too, have responded to contentions

that the statute on its face is clear by relying on legislative

history to read ambiguity into the statute’s terms. E.g.

Johnson v. Unde Ben’s, Inc., 965 F.2d at 1363 (holding that

the express exceptions to applicability in §§ 402(b) and 109(c)

do not clearly imply a general rule of applicability in § 402(a),

"given the swirling confusion surrounding the Act’s passage");

Mozee, 963 F.2d at 933 (holding §§ 402(b) and 109(c)

inconclusive because the legislative history makes "fairly clear"

that these sections were no more than "clear assurance" or

6 Ironically, the Gersman court emphasized that "we do not inquire

what the legislature meant; we ask only what the statute means," id. at 891,

quoting Starr, Obsen’ations about the Use o f Legislative History’, 1987 Duke

L. J. 371, 378 quoting O.W. Holmes, The Theory o f Legal Interpretation in

Collected Legal Papers, 207 (1920), because "it is only the statute itself

that is law," id. Yet the court nonetheless did dig below the surface of the

statutory language and drew on "snippets" of the legislative history to find

ambiguities behind the otherwise clear message of §§ 402(b) and 109(c)

Id. at 890.

15

"extra assurance" of prospective application in specified

circumstances).7

In sum, the Circuits have taken conflicting approaches

on the basic questions of interpreting statutory text, and of

the proper role of legislative history in construing legislative

terms. These questions are important, and they continue

frequently to vex the lower courts. Seven Circuits have

already addressed these issues in the context of the

applicability of the 1991 Civil Rights Act, and their conflicting

approaches call for resolution by this Court.

II. There is a Conflict Among tiie Circuits

Regarding Whether New Legislation,

Such as § 101 Of The 1991 Civil Rights

Act, Should Be Presumed Applicable To

Pre-Act Claims

A. There are Conflicting Presumptions Under

Bradley v. Richmond School Board and Bowen v.

Georgetown University Hospital

The Circuits are in conflict regarding the appropriate

presumption to determine the applicability of new legislation

to pending claims, and the Circuits identify conflicting

decisions of this Court as the root of the confusion. The

court below referred to "conflicting rules of construction"

announced by this Court in Bradley v. Richmond School Bd.,

416 U.S. 696 (1974), and Bowen v. Georgetown University

Hospital. 488 U.S. 204 (1988). App. lla-12a; see Vogel, 959

7 Although the Seventh Circuit in Mozee asserts that the legislative

history makes clear that § 402(b) and § 109(c) are only intended to

provide extra assurance of the Act’s nonretroactivity, the court

paradoxically acknowledges that "[a] clear indication of congressional

intent cannot be deciphered from the legislative history." 963 F.2d at 934.

16

F.2d at 597 (referring to Supreme Court doctrine on

application of new legislation as "not yet settled"). Bradley

held that a new statute applies to a pending claim "unless

doing so would result in manifest injustice or there is

statutory direction or legislative history to the contrary." 416

U.S. at 711. Bowen, on the other hand, stated that generally

"[rjetroactivity is not favored in the law. Thus, congressional

enactments and administrative rules will not be construed to

have retroactive effect unless their language requires this

result." 488 U.S. at 208. This Court in Bonjomo, 494 U.S. at

828, referred to this "apparent tension" in the prior decisions,

but did not resolve it because the statute at issue in Bonjomo

was clear on its face.

Other Courts of Appeals have also expressly referred

to a conflict in this Court’s cases, and have struggled to apply

the decisions in Bradley and Bowen. The Seventh Circuit in

Mozee referred to "conflicting Supreme Court precedent," and

to "two seemingly contradictory lines of cases." 963 F.2d at

934, 935. See Luddington, 966 F.2d at 227 (stating that "the

courts do not have a consistent rule for deciding whether a

statute shall be given retroactive, or merely prospective, effect

when the statute does not say," and agreeing with Justice

Scalia’s observation in Bonjomo that the Supreme Court’s

rules are "in irreconcilable contradiction"). The Eighth

Circuit in Fray agreed that the Supreme Court has established

"two contradictory rules of construction." 960 F.2d at 1375.

The Eleventh Circuit in Baynes similarly stated that this Court

"has so far declined to resolve the conflict in its own rules on

presumptions of statutory retroactivity." 1992 WL 296716 at

*1. The Fifth Circuit in Johnson lamented being "[fjorced ...

to choose a cannon of construction without the guidance of

controlling authority...." 965 F.2d at 1473.

In the face of this conflict, some courts have simply

made a choice to follow either Bradley, or Bowen. See, e.g.,

17

Landgraf v. USI Film Products, 968 F.2d 427, 432 (5th Cir.

1992) (holding under Bradley that § 102 of the 1991 Act

should not apply); Mozee, 963 F.2d at 938, 940 (holding under

Bowen that the 1991 Act should not apply); Fray, 960 F.2d at

1375, 1378 (referring to prior Eighth Circuit cases choosing

to follow Bowen rather than Bradley, and holding that the

1991 Act should not apply under either presumption); Baynes,

1992 WL 296716 *2 (referring to prior Eleventh Circuit cases

choosing to follow Bradley rather than Bowen, and holding

that the 1991 Act should not apply under either

presumption). Other courts have made attempts to reconcile

Bradley and Bowen by identifying the distinct circumstances

in which each applies. E.g. Vogel, 959 F.2d at 598 (holding

that Bradley applies only when new legislation does not alter

substantive rights); Johnson, 965 F.2d at 1374 (same);

Gersman, 975 F.2d at 892-900 (same). Certiorari should be

granted in this case because the Circuit courts need

additional guidance from this Court on which presumption to

apply.

The confusion in the law governing application of new

legislation is also reflected in the fact that, of the Courts that

have declined to apply the 1991 Act to pending claims,

several have done so over strong dissents. See, e.g., Mozee,

963 F.2d at 940 (Cudahy, J., dissenting); Fray, 960 F.2d at

1379 (Heaney, J., dissenting); Vogel, 959 F.2d at 601 (Ryan,

J., dissenting). Moreover, well over two hundred district

courts cases around the country have used various rationale

to reach conflicting decisions on the applicability of the same

provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 to pending claims.

See generally. Fray, 960 F.2d at 1374, 1383-84 (referring to the

confusion in the district courts, and appending a list of cases);

Vogel, 959 F.2d at 598 (referring to split among the district

courts).

18

The need for further guidance from this Court is also

demonstrated by the fact that, in litigation to which it is a

party, the United States has not taken a consistent position

on whether Bradley or Bowen governs. In a confused and

important area of the law, the lower federal courts might

ordinarily look to the Department of Justice for principled

guidance. Since this Court decided Bowen, however, the

United States has varied its position from case to case,

enthusiastically advocating application of the Bradley rule in

some cases, then disavowing it in others. For example, in

several recent briefs, the United States has asserted that

"Bradley correctly states the law,"8 describing the holding as

"important," "well-established,"9 "fundamental"10 11 a "time-

honored principle,"11 "well settled," and the rule which

"should control."12 In these cases, government attorneys

repeatedly quote the holding in Bradley that

8 Reply Brief of the United States to Opposition Briefs, United States

v. Allied Corp., Civil No. C-83-5898 FMS (N.D.Cal.) at 18.

The briefs cited herein are on file with this Court as Materials

Lodged by Atnicus NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

accompanying the petition for certiorari in Hades v. United Stales, No. 91-

1075 certiorari denied,__U .S .__ , 118 L.Ed.2d 419 (1992).

9 Response of the United States to Defendants’ Motion to Strike

Claims for Damages and Penalties, United States v. Rent America, No. 89-

6188-PAJNE (S.D.Fla.), at 23.

10 Brief for Respondent, Ayala-Cliave: i\ I.N.S., No. 91-70262 (9th

Cir.), at 19.

11 United States Reply to Defendants’ Oral Motion to Dismiss,

United States v. Cannon, Civil Action No. 6:91-951-3K (D.S.C.), at 4.

12 Brief of Plaintiff-Appellant Federal Deposit Insurance

Corporation, Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. v. Wriglit, No. 90-2217 (7th

Cir.), at 26, 27.

19

a court is to apply the law in effect at the time it

renders its decision, unless doing so would result in

manifest injustice or there is legislative history to the

contrary.13

Elsewhere, however, the United States has denigrated Bradley

and the similar decision in Thorpe v. Housing Authority o f

Durham, 393 U.S. 268 (1969), as

two exceptional Supreme Court decisions that

conspicuously depart from the general and

longstanding rule against retroactivity .... Nothing in

the Bradley Court’s reasoning compelled the

conclusion that its broad language suggests ....

* * *

["]It is significant that not a single one of the

earlier cases cited in Thorpe and Bradley ...

even 1purports to be applying a presumption of

retroactivity.14

When the United States has decided to oppose application of

a particular new statute to a pre-Act claim, it has repeatedly

urged the lower courts to "choose [Bowen v.J Georgetown

over Bradley," insisting that "Georgetown is the better

13 See, e.g., United Stales Reply to Defendants’ Oral Motion to

Dismiss, United Slates v. Cannon, Civil Action No. 6:91-951-3K (D.S.C.),

at 4, quoting Bradley i'. Richmond School Bd., 416 U.S. at 711.

14 Defendant’s Memorandum in Opposition to Plaintiffs Motion to

File Second Amended Complaint, Van Meter v. Bair, Civil Action No. 91-

0027 (GAG) (D.D.C.) at 14, 16 (emphasis in original) (quoting in part the

concurring opinion of Scalia, J., in Bonjorno, 110 S.Ct. at 1584)

20

decision."15 The inconsistent positions taken by the

government from case to case underscore the national

importance of the issues presented in this petition, and the

need for a resolution of the conflict among the circuits.

B. There is a Conflict Over Whether Retroactivity

is Determined by Reviewing the Act as a

Whole or by Reviewing the Section at Issue

There is a separate conflict in the Circuits about

whether the applicability of the 1991 Act should be analyzed

with reference to the Act as a whole, or to the particular

section sought to be applied. For example, the Fifth Circuit

expressly limited its determinations in Johnson and Landgraf

to the applicability of the particular sections before it; the

court below, in contrast, held that the Act as a whole is

inapplicable. Compare Johnson, 965 F.2d at 1372, 1374, and

Landgraf968 F.2d at 432-33, with Harvis, App. 14a. Johnson

expressly declined to consider "whether the Act’s provisions

affecting Title VII disparate impact claims are retroactive,"

because those provisions would have had no effect on

Johnson’s claims. 965 F.2d at 1372. The court then

examined § 101 alone to determine whether it "affects

substantive antecedent rights." Id. at 1374. Landgraf similarly

looked separately at each provision at issue in that case to

analyze whether its application would create "manifest

injustice" under Bradley. 968 F.2d at 432-33. The Sixth

Circuit in this case, however, held that the "distinction

between § 101 [at issue here] and § 108 [at issue in Vogel] is

immaterial, as both Fray and Vogel examined the retroactivity

of the 1991 CRA as a whole, not in terms of specific sections,

and both courts concluded that applying the Act retroactively

15 Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae, Davis v. Tri-State

Mack Distribution, Nos. 91-3574, 92-1123 (8th Cir.), at 13, n.6.

21

would adversely affect substantive rights and liabilities." App.

14a (emphasis added).

The Court of Appeals decisions that analyze the

applicability of the 1991 Act as a whole conflict with clear

precedent from this Court requiring section-by-section

analysis. In Bradley itself, this Court examined only § 718 of

the Education Amendments of 1972, relating to attorney’s

fees, to determine whether any "manifest injustice" would be

created by applying that particular provision to the pending

case. Bradley, 416 U.S. at 710-724. The Court in Bradley did

not consider the potential effects on pending cases of the

entire 176 pages of statutory provisions included in the

Education Amendments of 1972. See Pub. L. No. 92-318,

1972 U.S.C.C.A.N. (86 Stat.) 278-454. Similarly, this Court

in United States v. Security Industrial Bank determined the

inapplicability to pending claims of only § 522(f)(2) of the

Bankruptcy Reform Act of 1978, even while it acknowledged

the applicability of the balance of the amendments, on the

ground that only § 522(f)(2) would "destroy previously vested

property rights." 459 U.S. 70, 79 (1982). Certiorari should be

granted here to review the decision below which erroneously

determined the non-retroactivity of the 1991 Civil Rights Act

as a whole.

III. Under This Court’s Prior Decisions, The

Construction Of 42 U.S.C. § 1981 In Pa t t e r s o n v.

M cL e a n Cr e d it Un io n Should Nor Be Applied

Retroactively After Congress Expressly

Rejected It

Certiorari should be granted to determine the proper

application of Chevron Oil Co. v. Huson, 404 U.S. 97 (1971),

and James B. Beam Distilling Co. v. Georgia, 111 S. Ct. 2439

(1991), to this case. The court below applied the Patterson

decision retroactively to Rivers’s and Davison’s § 1981 claims

22

after Patterson's construction of the statute had been

repudiated by Congress. The decision below is thus contrary

to this Court’s decisions.

The common animating principle behind Chevron and

the fractured opinions in James B. Beam is that a new,

judicially announced rule should be promptly and uniformly

applied because the new rule is the one which has been

determined to be correct, and which will apply in all future

cases. Application of a new — and therefore presumably

correct — rule to pending cases advances the purposes

behind the judicial new rule, and promotes prompt uniformity

among judicial decisions. However, these considerations are

inapplicable where the new judicial rule has been repudiated

by Congress and will not be applied in the future. The effect

of retroactive application of a judicial construction that

Congress has rejected, such as Patterson's interpretation of

§ 1981. is simply to ensure more inconsistent decisions and to

perpetuate bad law.16

The propriety of non-retroactive application of new

rules of decision has long been governed by the standard set

forth in Chevron, 404 U.S. 97. This Court last Term in James

B. Beam limited Chevron by holding that when a new rule of

constitutional law is applied in the case announcing that rule,

the rule must then also be applied retroactively to all other

pending claims. James B. Beam did not overrule Chevron.

Because there were five separate opinions in James B. Beam,

and no plurality opinion, however, the precise scope of the

16 This reasoning does not depend on a determination that the 1991

Civil Rights Act applies to pending cases. Rather, it rests on a more

general notion that, to the extent that James B. Beam disfavors application

of defunct rules to pending cases and insists on prompt application of new

rules, that interest is subverted, not furthered, by anachronistic application

of Patterson.

23

decision is unclear, as is the continuing role of Chevron. This

case offers an ideal opportunity to refine the principles of

James B. Beam and Chevron, and to clarify the circumstances

in which each decision applies.

Because the Supreme Court’s holding in Patterson

interpreted 42 U.S.C. § 1981 and not the Constitution, the

holding of James B. Beam is inapplicable here, and Chevron

remains the test for determining retroactivity of Patterson.

Justices Scalia, Blackmun and Marshall concurred in the

judgment in James B. Beam in support of the retroactivity of

a constitutional decision to the claim before them, but they

did not support the broader reasoning of Justice Souter’s

opinion, nor reject the earlier holding of the Chevron case.17

Only Justices Souter, Stevens, and White adhered to a

general principle of retroactivity not limited to constitutional

decisions.18

Even if James B. Beam applied to decisions regarding

statutory as well as constitutional law, it should not apply to

this case because James B. Beam did not involve the

retroactive application of a rule of decision which has been

subsequently repudiated by Congress. The test announced in

Chevron thus applies here. The Court below, however,

applied Chevron improperly because it failed to consider the

impact of the 1991 Act on the retroactivity analysis.

17 111S. Ct. at 2449 (opinion by Blackmun, J., joined by Marshall

and Scalia, JJ., concurring in the judgment) (stating agreement only "that

failure to apply a newly declared constitutional rule to cases pending on

direct review violates basic norms of constitutional adjudication.")

(emphasis added).

18 111S. Ct. at 2442 (opinion by Souter, J., joined by Stevens, J.);

id. at 2448 (opinion by White, J., concurring in the judgment).

24

The three Chevron factors strongly counsel against

application of Patterson after Congress has rejected it. First,

Congress’ numerous references in enacting the 1991 Act to its

desire to restore § 1981 to its pre-Patterson construction make

clear that the decision "establish[ed] a new principle of law..."

at variance with the prior construction of § 1981. Chevron,

404 U.S. at 106.19 Second, the "purpose and effect" of

Patterson’s reading of § 1981, and the interest in "furthering]

... its operation," id. at 106-107, do not support Patterson’s

retroactivity because there is no valid interest in perpetuating

the operation of an obsolete rule by continuing to apply it

retroactively after it has been expressly repudiated. Third,

"the inequity imposed by retroactive application" and the

mandate of Chevron to avoid "injustice or hardship," id. at

15 Congress passed the 1991 Act "to respond to recent decisions of

the Supreme Court...." § 3(4). The legislative history corroborates the

plain language of the statute on § 101’s restorative function. There was

no disagreement by any member of Congress that legislation overturning

Patterson would restore what until 1989 had been the established reading

of § 1981. See. e.g. 137 Cong. Rec. S 15235 (daily ed. Oct. 25, 1991) (Sen.

Kennedy) (section 101 "will reverse ... Patterson... and restore the right of

Black Americans to be free from racial discrimination in the performance

— as well as the making — of job contracts"); 137 Cong. Rec. S 15489

(daily ed. Oct. 25, 1991) (Sen. Leahy) ("The Patterson decision drastically

limited section 1981’s application.... The Civil Rights Act of 1991 returns

the originally intended broad scope of this statute"); 137 Cong. Rec. H

9526 (daily ed. Nov. 7, 1991); (Rep. Edwards) (section 101 "reinstates" and

"restores" law prior to Patterson)-, 137 Cong. Rec. H3900 (daily ed. June 4,

1991) (Rep. Goodling) ("[H.R.l] reverses ... the Patterson case.... [T]he

substitute restores the expansive reading of Section 1981 that racial

discrimination is prohibited in all aspects of the making and enforcement

of contracts"); 137 Cong. Rec. H. 3935 (daily ed. June 5, 1991) (Rep.

Goodling) (describing Administration proposal as "same provision" as the

§ 101 precursor in H.R. 1); 136 Cong. Rec. S 9851 (daily ed. July 17,1990)

(Sen. Kassebaum) (§ 101 codifies "the law as it was prior to Patterson")-,

137 Cong. Rec. S 15285 (daily ed. Oct. 28, 1991) (Sen. Seymour) (Act

"restores section 1981").

25

107, requires that Patterson not be applied. Accrued claims

of racially discriminatory firing that were filed prior to the

Supreme Court’s decision in Patterson and that were

ultimately decided after Congress rejected Patterson should

not be eliminated simply because they were pending during

the brief life of Patterson. Similar claims survived simply

because they were decided earlier or arose later. Certiorari

should be granted to review the decision of the court below

because it applied Patterson retroactively without properly

analyzing the impact of the 1991 Act on application of

Chevron to this case.

26

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above, a writ of certiorari

should issue to review the judgment and opinion of the Sixth

Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

Ellis Boal

925 Ford Building

Detroit, MI 48226

(313) 962-2770

Cornelia T.L. Pillard

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Julius L. Chambers

Charles S. Ralston

Eric Schnapper

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

December 2, 1992

A P P E N D I X

Recommended For Full-Text Publication

Pursuant to Sixth Circuit Rule 24

No. 91-3348

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

JAMES T. HARVIS, JR.,

Plaintiff,

MAURICE RIVERS and

ROBERT C. DAVISON.

Plaintiffs-

Appellants.

ROADWAY EXPRESS. INC.

Defendant-

Appellee.

On Appeal from

the United States

District Court for

the Northern

District of Ohio

Decided and Filed August 24, 1992

Before: GUY, BOGGS, and SILER, Circuit Judges.

BOGGS. Circuit Judge, delivered the opinion of the

court, in which GUY, Circuit Judge, joined. SILER, Circuit

Judge (pp. 14-16) [14a-16a], delivered a separate opinion

concurring in part and dissenting in part.

2a

BOGGS, Circuit Judge. In this race discrimination

case, the appellants originally claimed they were discharged

because of racial discrimination and now state that the claim

was also for retaliatory discharge for winning a grievance,

exercised for racial reasons. The claim was dismissed by the

district court based upon the United States Supreme Court

ruling in Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 491 U.S. 164

(1989). On appeal, appellants argue that the district court

misapplied Patterson, but that even if their claim had been

properly dismissed, this court should reinstate their claim by

retroactively applying to this case the new Civil Rights Act

of 1991 (CRA of 1991), Pub. L. No. 102-166, 105 Stat. 1071-

1100, 42 U.S.C. § 1981, which explicitly enacted the

interpretation of § 1981 rejected in Patterson. We reverse on

the grounds that the district court misapplied Patterson to

dismiss appellants’ retaliatory discharge claim. We affirm

the district court’s dismissal of the race discrimination in

firing claim, and hold that the CRA of 1991 should be not

applied retroactively to this case.

I

Plaintiffs-appellants Maurice Rivers and Robert C.

Davison are Black garage mechanics who were employed by

defendant Roadway Express, Inc. since 1972 and 1973

respectively. On the morning of August 22, 1986, Roadway

verbally informed Rivers and Davison that they were

required to attended disciplinary hearings that same day

related to their accumulated work record. Both plaintiffs

refused to attend, alleging inadequate notice. Roadway was

contractually required to provide prior written notice of such

hearings and allegedly routinely did so for white employees.

The hearings resulted in two-day suspensions for both

appellants. Appellants filed grievances with the Toledo

Local Joint Grievance Committee (TUGC), which granted

the grievances based on "improprieties" and awarded each

appellant two days of back pay.

3a

Shortly after these initial hearings, disciplinary

hearings were again called by Roadway’s Labor Relations

Manager, James O’Neil, who announced that he would hold

disciplinary hearings against Rivers and Davison within

seventy-two hours. Rivers and Davison again refused to

attend, claiming inadequate notice. As the result of the

hearings, both Rivers and Davison were discharged on

September 26, 1986, for refusing several direct orders to

attend the hearings and for the accumulated work record.

In February 1987, Rivers and Davison, along with

James T. Harvis, filed this suit, alleging that Roadway

discriminated against them on the basis of race, in violation

of 42 U.S.C. § 2000e. They also alleged that Roadway

violated the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947

(LMRA), 29 U.S.C. § 185(a), and brought an unfair

representation claim against their union. Both of these

latter claims were dismissed on summary judgment by the

district court.

The district court then separated Harvis’s case, which

went to trial and ended in a jury verdict on the § 1981 claim

for Roadway. The district court ordered judgment against

Harvis on his § 1981 and Title VII claims. Harvis’s appeal

to this court was denied and the trial court’s judgment

affirmed. Harvis v. Roadway Express, Inc., 923 F.2d 59 (6th

Cir. 1991).

On June 15, 1989, shortly after Harvis’s verdict and

before appellants went to trial, the Supreme Court decided

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 491 U.S. 164, 109 S. Ct.

2363 (1989), which held that the right to make contracts

protected by § 1981 does not apply to conditions of

employment, but only covers discrimination in the formation

of the employment contract or the right to enforce the

contract. The district court, while holding that Patterson was

not retroactive with respect to Harvis’s jury verdict, held it

did have retroactive effect on the untried and pending

4a

§ 1981 claims of Rivers and Davison. The district court

concluded that appellants’ claims were for discriminatory

discharge and thus, based on Patterson, could not be

maintained under § 1981. Rivers and Davison argued that

their claims were not simply for discriminatory discharge, but

rather for retaliation for their success in enforcing contract

rights in a grievance hearing. However, the district court

held that these were only basic breach of contract claims,

and not claims based on the right to enforce contracts, which

would fall under § 1981. After dismissing the § 1981 claims,

the district court held a bench trial on plaintiffs’ Title VII

claims and ruled in favor of Roadway, holding that Rivers

and Davison failed to establish that their discharge from

employment was based upon their race.

Rivers and Davison appeal the district court’s

dismissal of their § 1981 claims on two grounds. First, they

argue that Patterson does not preclude this action, as it is

not an action for discriminatory discharge, but rather an

action based on retaliation for attempting to enforce the

labor agreement, thus squarely falling under § 1981. Second,

while this appeal was pending, the CRA of 1991 was

enacted, explicitly contradicting the Patterson decision.

Appellants argue that the CRA of 1991 should be applied

retroactively to their § 1981 claims, thus invalidating the

district court’s decision. The case, they argue, should be

remanded for a new determination under this new

legislation.

II

42 U.S.C. § 1981 provides:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State and

Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal

benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of

5a

persons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens,

and shall be subject to like punishment, pains,

penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions of every kind,

and to no other.

The Patterson court limited the scope of § 1981

actions by holding that § 1981 does not apply to

discrimination in conditions of employment, but only

prohibits discrimination in the formation of the employment

contract or the right to enforce the contract. Patterson, 491

U.S. at 176. Thus, under Patterson, § 1981 "covers only

conduct at the initial formation of the contract and conduct

which impairs the right to enforce contract obligations

through legal process." Id. at 179.

While Patterson did not directly address the issue of

whether § 1981 applied to discriminatory discharges, this

court, along with a majority of other courts, has held that

claims of discriminatory discharge arc no longer cognizable

under § 1981 because discharge does not involve contract

formation. See Prather v. Dayton Power & Light Co., 918

F.2d 1255 (6th Cir. 1990), cert, denied, 111 S. Ct. 2889

(1991); Hull v. Cuyahoga Valley Bd. o f Educ., 926 F.2d 505

(6th Cir. 1991), cert, denied, 111 S. Ct. 2917 (1991). The

plaintiffs, below and on appeal, argue that theirs were not

discriminatory discharge claims, but rather, claims of

retaliatory discharge where plaintiffs were punished for

attempting to enforce their contract rights to be treated

equally with white people. The district court rejected this

claim as "bootstrapping" and held that this was solely a

discriminatory discharge case.

Before deciding whether or not Patterson was

correctly applied, we must first address whether the district

court was correct in retroactively applying Patterson to the

claims of Rivers and Davison. Our circuit has twice held

that Patterson does apply retroactively to pending cases. In

Prather v. Dayton Power & Light Co., supra, we applied

6a

Patterson retroactively to a pending discriminatory discharge

case based on three factors used to determine whether an

exception mandating non retroactivity exists, as discussed by

the Supreme Court in Chevron Oil Co. v. Huson, 404 U.S. 97

(1971). Under these factors, a decision will not be applied

retroactively if, first, it

establishes a new principle of law, either by

overruling clear past precedent on which

litigants have relied . . . or by deciding an

issue of first impression whose resolution was

not clearly foreshadowed.

Id. at 106 (citations omitted). The second retroactivity

factor is the "prior history of the rule in question, its purpose

and effect, and whether retrospective operation will further

or retard its operation." Id. at 106-07. Finally, the third

factor involves weighing "the inequity imposed by retroactive

application" to avoid "injustice or hardship." Id. at 107.

Weighing these factors, the Prather court held that

applying Patterson retroactively would not "retard its

operation," nor would it produce "substantial inequitable

results" that might otherwise be avoided and concluded that

applying Patterson would not unduly prejudice the plaintiff.

Prather. 918 F.2d at 1258. This decision was reaffirmed in

Hull v. Cuyahoga Valley Bd. o f Educ., supra. The district

court correctly found that Patterson applied retroactively to

the pending § 1981 claims of Rivers and Davison.

Ill

Appellants argue that, even if Patterson is applied

retroactively to their case, their claims still survive Patterson

and the district court wrongly dismissed the claim as a

discriminatory discharge complaint not recognized under

§ 1981. We agree.

7a

Appellants contend that Patterson only eliminates

those claims of retaliation for exercising rights that are

unrelated to the specific § 1981 right to "make and enforce

contracts." But, they argue, Patterson does not eliminate a

cause of action for exercising rights that do relate to the

enforcement of contract rights. Appellants maintain that

they are not making discriminatory discharge claims, but

rather are claiming retaliatory discharge that punished them

for enforcing their contract right to receive notice equal to

that received by whites.

Roadway counters that Rivers and Davison were not

punished for enforcing their contract rights as

The right to enforce contracts does not

however extend beyond conduct by an

employer which impairs an employee’s ability

to enforce through legal process his or her

established contract rights.

Patterson, 491 U.S. at 177-78.

However, the prohibited conduct of impairing the

ability to enforce contract rights is exactly what appellants

are complaining about here. Rivers and Davison were

punished, they contend, for trying to utilize the established

legal process for their grievances. The fact that Roadway

allowed formal "access" to legal process does not imply that

it could never be impairing the employee’s "ability to enforce

through legal process." An employer’s intimidation and

punishment conducted inside formal legal process may

impair an employee’s contract rights just as much as

intimidation and punishment conducted outside formal legal

process. See Carter v. South Central Bell, 912 F.2d 832, 840

(5th Cir. 1990), cert, denied, 111 S. Ct. 2916 (1991) (court

emphasized that the alleged conduct must have impaired the

plaintiffs ability to enforce contractual rights either through

court or otherwise on the basis of race).

8a

Appellants’ claims are similar to those in Von

Zuckerslein v. Argonne National Lab., 760 F. Supp. 1310,

1318 (N.D. 111. 1991), where plaintiffs were permitted to

proceed to trial on their § 1981 claims that "defendants

specifically retaliated against them for pursuing (or intending

to pursue) their contract claims in the internal grievance

forum." Id. at 1318 (emphasis in original). We do not agree

with appellee’s argument that Von Zuckerstein is

distinguishable because it involved an employer who

impaired or impeded the plaintiffs from using the available

legal process to enforce a specific anti-discrimination

contract right. However. § 1981 speaks of the right to

"enforce contracts," which includes any contract rights, not

just anti-discrimination contract rights. The key here is that

plaintiffs were impaired from enforcing contract rights, not

the kind of contract right they were impaired from

enforcing. Just because Rivers and Davison were allowed to

use the available legal process does not mean the employer

did not discriminate against them through retaliation for the

very act of using that legal process. Retaliation is defined

more broadly than mere access to legal process. McKnight

v. General Motors Corp.. 908 F.2d 104. I l l (7th Cir. 199),

cert, denied, 111 S. Ct. 1306 (1991), held that retaliation "is

a common method of deterrence." We hold that appellants

have articulated this essential element of § 1981, that their

ability to enforce claimed contract rights was impaired

because of their race.

Roadway argues that even if retaliatory discharge did

occur, the plaintiffs never alleged retaliatory discharge in

either their first or amended complaints. However, upon

examination of the record, we find that sufficient allegations

exist to form the basis of a retaliatory discharge claim.

While appellants admit that their pre-Patterson complaint

was not specifically structured as a "right to enforce a

contract" claim as opposed to a "condition of employment"

claim, the very basis of their complaint has always stemmed

from retaliatory discharge. They allege, in their amended

9a

complaint, that "Rivers’ [sic] and Davison’s discharges were

taken without just cause. More particularly Roadway

scheduled a hearing for them for September 26, 1986, based

on conduct for which a grievance committee had previously

exonerated them with backpay." We find that the appellants’

claims fall within the Patterson definition of permissible

§ 1981 actions, as the claims involve discrimination in the

right to enforce a contract. We hold that the district court

wrongly dismissed appellants’ § 1981 claims and the case

should be remanded for further proceedings on the § 1981

claims.

Our holding that the case should be remanded for

further proceedings on. appellants’ § 1981 claims raises

potential collateral-estoppel problems. The district court has

already had a bench trial on the appellants’ Title VII claims,

finding that Rivers and Davison were not discharged from

employment based on their race.

A similar situation existed in Lytle v. Household Mfg.,

Inc., 494 U.S. 545 (1990), where Lytle, a Black machinist for

a subsidiary of Household Manufacturing, was dismissed for

unexcused absences. Lytle filed a complaint with the EEOC,

alleging that he had been treated differently than white

employees who missed work. He then brought

discriminatory discharge and retaliation claims under § 1981

and Title VII. The district court dismissed Lytle’s § 1981

claims, concluding that Title VII provided the exclusive

remedy for his racial discharge and retaliation claims. At a

bench trial on the Title VII claims, the district court

dismissed Lytle’s discriminatory discharge claims pursuant to

Rule 41(b), Fed. R. Civ. P„ and granted defendants

summary judgment on the retaliation claim.

The Fourth Circuit affirmed, ruling that the district

court’s findings with respect to Title VII claims collaterally

estopped Lytle from litigating his § 1981 claims because the

elements of a cause of action under § 1981 are identical to

10a

those under Title VII. Lytle, 494 U.S. at 549; see also

Washington v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 756 F.

Supp. 1547, 1555 (M.D. Ga. 1991). The Supreme Court

reversed, based on plaintiffs seventh amendment right to

trial by jury in "suits at common law," noting that:

When legal and equitable claims are joined in

the same action, "the right to jury trial on the

legal claim, including all issues common to

both claims, remains intact."

Lytle, 494 U.S. at 550 (citations omitted).

The Supreme Court distinguished the Lytle situation,

where the equitable and legal claims were brought together,

from the situation in Parklane Hosiery Co. v. Shore, 439 U.S.

322 (1979), where the Supreme Court held that "an

equitable determination can have collateral-estoppel effect

in subsequent legal action and that this estoppel does not

violate the Seventh Amendment." Lytle, 494 U.S. at 550-51

(citing Parklane Hosiery Co., 439 U.S. at 335) (emphasis

added).

We find that our situation falls squarely under the

Lytle precedent and hold that collateral estoppel does not

preclude relitigation of issues decided by the district court in

its bench trial resolution of the equitable claims of Rivers

and Davison under Title VII. As in Lytle, the purposes

served by collateral estoppel do not justify applying the

doctrine in this case. Id. at 553. Collateral estoppel is

designed to protect parties from multiple lawsuits and

potentially inconsistent decisions, as well as to conserve

judicial resources. Ibid. Although remanding for further

proceedings certainly will expend greater judicial resources,

such litigation is essential in preserving Rivers’s and

Davison’s seventh amendment rights to a jury trial.

11a

V