Correspondence between Judge Thompson and Cochran

Public Court Documents

March 21, 1986

3 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Correspondence between Judge Thompson and Cochran, 1986. 64b373c1-b8d8-ef11-a730-7c1e527e6da9. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/866a97cd-1b3a-4274-9186-33c8a0db6818/correspondence-between-judge-thompson-and-cochran. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Q. STATES DISTRICT COURT ( ov

MIC D y 98

2

MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA 36101

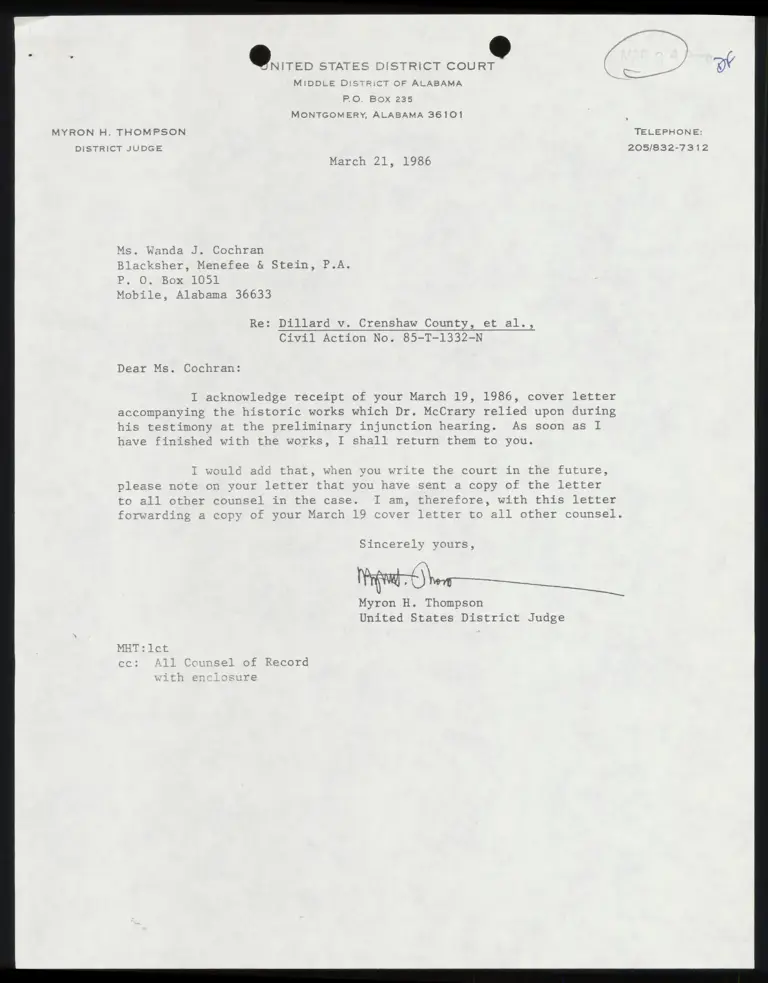

MYRON H. THOMPSON TELEPHONE:

DISTRICT JUDGE 205/832-7312

March 21, 1986

-

i Ms. Wanda J. Cochran

lacksher, Menefee & Stein, P.A.

.: 0. Box. 1051

, Alabama 36633

Re: Dillard v. Crenshaw County, et al.,

Civil Action No. 85-T-1332-N

Dear Ms. Cochran:

I acknowledge receipt of your March 19, 1986, cover letter

accompanying the historic works which Dr. McCrary relied upon during

his testimony at the preliminary injunction hearing. As soon as I

have finished with the works, I shall return them to you.

I would add that, when you write the court in the future,

please note on your letter that you have sent a copy of the letter

to all other counsel in the case. I am, therefore, with this letter

forwarding a copy of your March 19 cover letter to all other counsel. 5 k J

Sincerely yours,

Myron H. Thompson

United States District Judge

MHT:lct

cc 11. C sel of Record

Pla laa V Als BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN, P.A.

405 VAN ANTWERP BUILDING

FP. 8. BOX 1051

MOBILE, ALABAMA 36633-1051

ITED

JAMES "LIT

LARRY T. MEN

TELEPHONE

March 19, 1988 (205) 433-2000

MAR 0 0) 1086

Hon. Myron H. Thompson MAR 2 0 1986

United States District Judge TILIA AD

Middle District of Alabama mh Lot eh

15 Lee Street aa

Montgomery, AL 36101

RE: Dillard v. Crenshaw County, Alabama, et al.

Civil Action No. 85-1332—-N

st

aN ON andard

Eric Anderson, Race and Politics in North Ca

1901 (1981);

H o — I

5 cv fo

nd

0

~

J

20 ct vie]

C. Van Woodward, Origins of the New South, 1877-1913 (1951);

~ o - oy n tas *

Shy fF 3c ~ ~~ s \ “5 “ Fa - Lawson, Black Ballots V in the South,

- rs

4 (1978)

X =i w/ s

x; - a TE A a I TES

ahs he vv 4 5TH 1 ¥= 1 19 Son ~N CS \ 7 - { .

TITY YOTEe D1iution SEs Li 4 on 80 1884 ) ;

i RT ~~" Ds - ow al a Ti = «= -- — de Py ~ = wa 1 jo lb pe - ~~ Tr . ES } 1 Ww TY nea oO Jd. NOTTEll, HEADlIDY 1 1 aie Lal ViE 81 S

: inn col or FF = CE =

= 24S rege e WE Rioie] ) eg

McMillan, M.

Leder

ra i

EPR

il

-

3

T

e

a

n

M

P78.

Fai

C

KSHER

A

7S

724

"Wanda J.

PE

e

d

oO

oO

FD

o

=

=]