Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

July 19, 1988

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Brief for Appellants, 1988. 2f211f1f-f211-ef11-9f89-6045bda844fd. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/86c87215-e812-4114-b281-c62d11d4d33d/brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

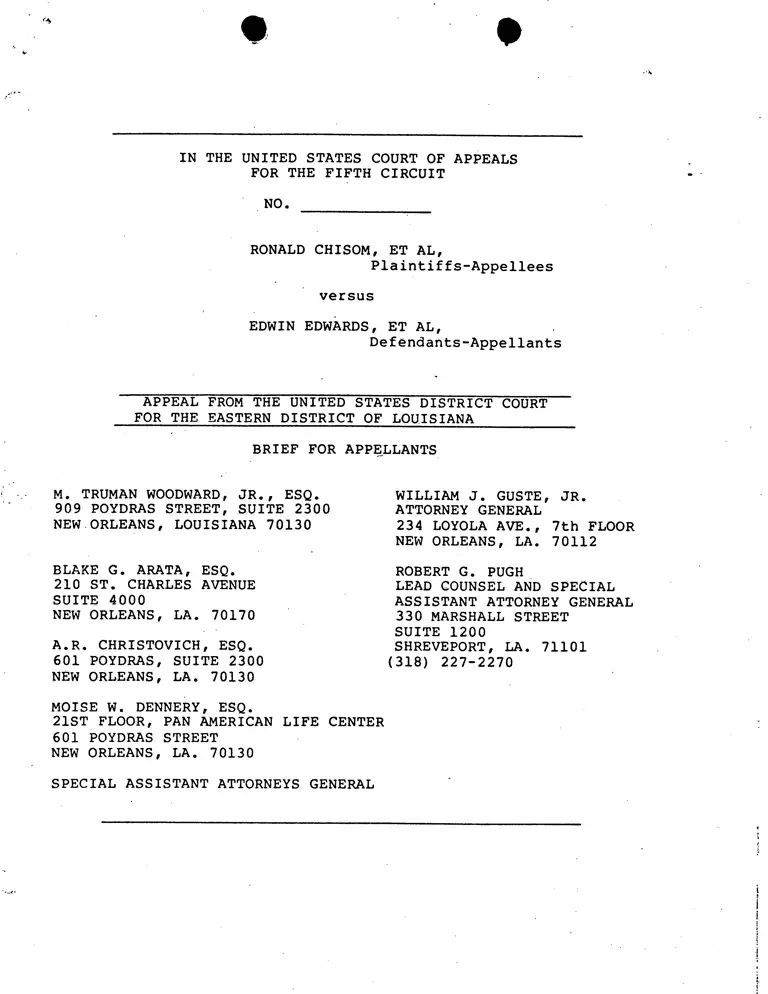

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO.

RONALD CHISOM, ET AL,

Plaintiffs-Appellees

versus

EDWIN EDWARDS, ET AL,

Defendants-Appellants

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

M. TRUMAN WOODWARD, JR., ESQ.

909 POYDRAS STREET, SUITE 2300

NEW.ORLEANS, LOUISIANA 70130

BLAKE G. ARATA, ESQ.

210 ST. CHARLES AVENUE

SUITE 4000

NEW ORLEANS, LA. 70170

A.R. CHRISTOVICH, ESQ.

601 POYDRAS, SUITE 2300

NEW ORLEANS, LA. 70130

MOISE W. DENNERY, ESQ.

21ST FLOOR, PAN AMERICAN

601 POYDRAS STREET

NEW ORLEANS, LA. 70130

LIFE CENTER

SPECIAL ASSISTANT ATTORNEYS GENERAL

WILLIAM J. GUSTE, JR.

ATTORNEY GENERAL

234 LOYOLA AVE., 7th FLOOR

NEW ORLEANS, LA. 70112

ROBERT G. PUGH •

LEAD COUNSEL AND SPECIAL

ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

330 MARSHALL STREET

SUITE 1200

SHREVEPORT, LA. 71101

(318) 227-2270

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO.

RONALD CHISOM, ET AL.

Plaintiffs-Appellees

VERSUS

EDWIN EDWARDS, ET AL

Defendants-Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

- Pursuant to'Rule 28.2.1, the undersigned counsel of

record certifies that the following listed persons have an

interest in the outcome of this case. These representations

are made in order that the Judges of this Court may evaluate

possible disqualification or recusal.

(1) Plaintiffs: Ronald Chisom, Marie-Bookman, Walter Willard,

Marc Morial, Henry A. Dillon, III, Louisiana Voter Registration

Education Crusade.

(2) Defendants: The Governor, Secretary of State and

Commissioner of Elections of the State of Louisiana.

(3) Amicus curiae: John A. Dixon, Jr., Chief Justice of the

Louisiana Supreme Court; Pascal F. Calogero,•Jr., Associate

Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court; Walter F. Marcus, Jr.,

Associate Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court; United States

Dept. of Justice; Washington Legal Foundation.

(4) Counsel for plaintiffs: William P. Quigley, Julius L.

Chambers, Roy Rodney, Ron Wilson, Charles S. Ralston, C. Lani

Guinier, Pamela S. Karlan.

(5) Counsel for Defendants: William J. Guste, Jr., Attorney

General, Robert G. Pugh, M. Truman Woodward, Blake G. Arata,

A.R. Christovich, Moise W. Dennery.

(6) Counsel for amicus curiae: Ira J. Rosenzweig, Charles A.

Kronlage, Jr., Peter Butler, Paul D. Kamener, Mark Gross.

Attorney of Record for

Defendants-Appellants

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

Given the importance of the election of Supreme Court

Justices to the State of Louisiana and its citizens and because

of the complexity of the legal issues raised in this brief,

appellants are inclined to request that oral argument be

granted. However, defendants do not desire oral argument if

this court should deny defendants' motion for a stay of the

order of injunctive relief pending appeal-(a pleading filed

this day) and if scheduling will prevent this court from giving

expedited consideration to this appeal and ruling prior to the

July 27-29, 1988 qualifying period for the 1988 First Supreme

Court District election. In this latter event, appellants will

waive oral argument.

•

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Certificate of Interested Persons

Statement Regarding Oral Argument

Table of Contents iv

Table of Authorities vi

Statement of Jurisdiction 1

Statement of Issues On Appeal 2

Statement of the Case 2

(i) Course of Proceedings and Disposition

in the Court Below 3

(ii) Facts 7

Summary of the Argument 9

Argument 12

THE DISTRICT COURT'S DECISION TO ENJOIN

THE 1988 ELECTION WAS IN ERROR BECAUSE PLAINTIFFS

HAVE FAILED TO MEET THE FOUR-PRONGED TEST FOR A

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION 12

(1) Plaintiffs' Likelihood of Success

On the Merits Is Dependent Upon How the

United States Supreme Court Rules On

Defendants' Application for Certiorari;

There Is Also Little or No Likelihood That

Even If They Prevail On the Merits, They Would

Thereafter Succeed In Causing An Election To Be

Held In a Black Majority District For the 1988

Seat 13

(2) Even If Plaintiffs Were To Establish

A Substantial Likelihood of Success on the

Merits, They Will Not Suffer Irreparable

Injury If Their Injunction Request is

Denied 15

(iv)

(A) Even if Plaintiffs Prevail on the Merits,

the 1990 First Supreme Court District Election

Can Be Held for a Black Majority

District 15

(B) Alternatively, Plaintiffs Will Not Suffer

Irreparable Harm if the 1988 Election Is Not

Enjoined Because, If They Later Prevail on the

Merits, the Results of That Election Can Be

Invalidated 24

(3) The Benefits, if any, of An Injunction,

Are Far Outweighed by the Damaging Effects of

Cancelling The Election 27

(4) An Injunction Will Not Serve the

Public Interest 39

Conclusion 43

Certificate of Service 46

(v)

(- TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Banks V. Board of Education, 659 F. Supp. 395

(C.D. III.

1987) 33-35

Bell v. Southwell, 376 F. 2d 659 (5th Cir. 1967) 25

Canal Authority v. Callaway, 489 F. 2d 567,

(5th Cir. 1974) 12, 36-37

Cook v. Luckett, 735 F. 2d 912 (5th Cir. 1984) 25

Dillard V. Crenshaw County, 640 F. Supp. ).247

(M.D. Ala. 1986) 33, 39

Hamer v. Campbell, 358 F. 2d 215 (5th Cir. 1966) 25

Knox v. Milwaukee County Board of Election

Commissioners, 591 F. Supp. 399 (E.D. Wis. 1984) 36

Morial v. Judiciary Commission of the State of La.,

565 F. 2d 295 (5th Cir. 1977) (en banc), cert. denied,

435 U.S. 1013 (1978) 42

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) 18,30,31

Taylor v. Haywood County, 544 F. Supp. 1122

(W.D. Tenn. 1982) 36-37

Constitutions and Statutes:

Louisiana Constitution of 1974:

Article 5, §§3-4 3

Article 5, §22 (B) 29

Louisiana Constitution of 1921:

Article 7, §9 3

Louisiana Constitution of 1913:

Article 87 3

(vi)

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO.

RONALD CHISOM, ET AL,

Plaintiffs- Appellees

EDWIN EDWARDS, ET AL.,

Defendants- Appellants

' ORIGINAL BRIEF OF DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

This Court has jurisdiction pursuant to the provisions

of 28 U.S.C. §1292(a)(1).

STATEMENT OF ISSUES ON APPEAL

Did the trial court err by granting plaintiffs' motion

for a preliminary injunction and cancelling the October 1, 1988

election for the First Supreme Court District?

(A) Will the plaintiffs suffer irreparable injury if

the 1988 election is held, given the fact that even if they

ultimately prevail on the merits, an adequate prospective

remedy will then be available to them?

(B) Alternatively, will plaintiffs suffer irreparable

harm if the 1988 election results can be invalidated when and

if plaintiffs prevail on the merits?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Assuming without admitting -that this Court's earlier

decision (that S2 of the Voting Rights Act applies to judicial

elections) will stand, and that plaintiffs will prevail on the

merits in the district court, should the election for the 1988

First Supreme Court District be enjoined? Will there be

irreparable injury to plaintiffs if that election is allowed to

go forward? That is the major issue which was before the

district court in this case. Shorn of its discussion of other

issues, less significant for the resolution of this appeal, the

district court's thirty-five page opinion discusses irreparable

injury in just three pages. The reasons cited therein are

sparse and, we respectfully submit, adequately answered in the

brief that follows.

(i) Course of Proceedings and Disposition in the Courts Below

This suit involves a challenge to Louisiana's

longstanding method of electing state supreme court justices

from the First Supreme Court District. That district consists

of the most populous metropolitan area in the state, the

Parishes of Orleans, Jefferson, St. Bernard and Plaquemines.

Pursuant to the requirements of the Louisiana Constitution,

this district elects two justices to the seven member state

supreme court, and five other districts each elect one

justice. 1

1 See La. Const. of 1974, Art. 5, §§ 3-4. Two justices

were elected from the identical four-parish First Supreme Court

District under the Louisiana Constitution of 1921 (Art. 7, 0),

and two justices were elected from a First Supreme Court

District that included these four parishes and other

surrounding parishes under the Louisiana constitutions of 1913

(Art. 87), 1898 (Art. 87) and 1879 (Art. 83). Under those same

1921, 1913, 1898 and 1879 Constitutions the other Louisiana

Supreme Court justices were elected from individual districts.

Plaintiffs, Ronald Chisom et al., are black voters who

reside in Orleans Parish. On September 19, 1986, they filed

suit against the Governor of Louisiana, the Secretary of State

and the Commissioner of Elections, claiming that the election

of two justices from the present First Supreme Court District

dilutes black voting strength and violates the "results" test

of §2 of the Voting Rights Act and the intent standard of the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. As a remedy for these

alleged violations, plaintiffs proposed splitting the First

Supreme Court District into two new districts, one such

district to consist of Orleans Parish (in which the majority of

registered voters are black), and the other new district to

consist of the three suburban parishes. (It is the present

intention of defendants, if they are given leave to do so by

this Court, and if it can be accomplished mechanically in short

order, to file a supplemental brief which contains a map that

illustrates the concentration of black and white voters on a

ward and precinct basis in the four parish First Supreme Court

District).

The defendants moved to dismiss plaintiffs' complaint

for failure to state a claim upon which relief could be

granted. They argued that plaintiffs failed to state a cause

of action under either the Voting Rights Act, on the ground

that §2 of the Act does not apply to judicial elections, or

under the Constitution. The district court agreed, and

dismissed the plaintiffs' complaint on May 1, 1987.

Plaintiffs appealed the district court's ruling to

this court, and requested an expedited hearing of their

appeal. The request for expedited consideration was denied.

On February 29, 1988, in an opinion authored by Judge Johnson

and joined by Judges Brown and Higginbotham, this court

reversed the district court and ruled that plaintiffs have

stated viable claims under the Voting Rights Act and the

Constitution. The defendant's petition for rehearing and

suggestion for rehearing en banc were denied on May 27, 1988,

at which time the court issued its mandate.

The defendants intend to seek review by the United

States Supreme Court of this court's ruling that the plaintiffs

have stated a cognizable claim under the Voting Rights Act.

The major issue presented by that application for certiorari

will be whether §2 of the Voting Rights Act, as amended in

1982, applies to judicial elections.

While defendants' application for rehearing of the

February 29, 1988 ruling was still pending, plaintiffs filed a

motion asking this court to enjoin the scheduled October 1,

1988 election for the First Supreme Court District seat

presently held by Justice Pascal F. Calogero, Jr. On May 27,

1988, this request for injunctive relief was denied, for the

reason that any such request should be made in the first

instance to the district court.

Plaintiffs then sought a preliminary injunction from

the district court, which held a hearing on plaintiffs' motion

on June 29, 1988. 2 On July 7, 1988, the district court

enjoined the scheduled 1988 election, and it is from this

ruling that the defendants now appeal. On July 13, 1988,

defendants asked the district court to stay its order of

injunctive relief pending appeal of that order, and on the same

dat the district court denied that motion.

2 Interestingly, plaintiffs have represented that after the

Fifth Circuit rejected their request for injunctive relief

pending appeal, they did not. intend then to seek a preliminary

injunction from the district court. What happened was that the

district court judge provoked a status conference, at which

plaintiffs stated that they "were prepared at •that time to file

a motion for summary judgment." Plaintiffs' Reply Memorandum

in Support of Motion (to the district court) for A Preliminary

Injunction at 5. However, plaintiffs decided to seek a

preliminary injunction after the district judge advised them of

his "reluctance to rush defendants to a final adjudication on

the merits." Id. at 5 n. 2.

-6-

(ii) Facts

The key facts which pertain to the issue of whether or

not the district court erred by enjoining the election are not

in dispute. Those facts have been supplied by affidavits and

stipulations. No testimony was offered at the June 29, 1988

hearing before the district court.

In addition to being undisputed, the pertinent facts

make clear that this is a unique case. A thorough

understanding of certain essentials is critical to an

understanding of defendant's position on -appeal, which is that

the district court's decision to enjoin the election is not

legally supportable, primarily because it is unnecessary, since

plaintiffs will not suffer irreparable injury if the 1988

election is allowed.

It is most important for any court considering the

question of whether the 1988 First Supreme Court District

election should be enjoined to know that:

(1) Plaintiffs' goal in this litigation is

the creation of a new district, drawn within

the contours of the present four-parish

First Supreme Court District, in which the

majority of registered voters are black.

See Plaintiffs' Amended Complaint at V.

n.

(2) Any such newly created black voter

majority district would necessarily consist

of most or all of Orleans Parish, given the

black/white voter distribution within the

present First Supreme Court District. See

Plaintiffs Statement of Facts As To Which

They Contend There Is No Dispute, nos. 10-16

& 62.

(3) Thus, the other new district which would

be created by a division of the present

First Supreme Court District would include

most or all of the suburban parishes of St.

Bernard, Jefferson and Plaquemines.

(4) Elections for the two First Supreme

Court District seats are, and traditionally

have been, staggered.

(5) The First Supreme Court District seat

scheduled for an election in 1988 is

presently held by Justice Pascal F.

Calogero, Jr., a resident of Jefferson

Parish who is an active candidate for

reelection in 1988. See affidavit of Pascal

F. Calogero, Jr., exhibit to Defendant's

Opposition to Plaintiffs' Motion (in the

district court) for a Preliminary Injunction.

(6) The other First Supreme Court District

seat is held by Justice Walter F. Marcus,

Jr., a resident of Orleans Parish, and an

election for that seat is scheduled in

1990. Justice Marcus has indicated through

arguments made in amicus curiae briefs filed

earlier in the district court and in the

court of appeals that he intends to seek

re-election in 1990.

(7) The qualifying period for the 1988

election is scheduled for July 27-29, 1988.

(8) Justice Calogero and at least one other

are active candidates in the 1988 election and

have expended considerable time and effort

in preparing for that election.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The foregoing facts demonstrate that the existing

electoral system will provide plaintiffs with an adequate

prospective remedy. The drastic step of enjoining the 1988

election is not necessary as a means of accomplishing that

remedy. In fact, an injunction which stops the 1988 election,

while harmful to all voters of the First District because it

denies them the opportunity which they otherwise would and

should have, to elect a supreme court justice in 1988, almost

certainly will not accomplish the plaintiffs' goal of having a

supreme court justice elected from a black voter majority

district any sooner than that goal could be accomplished if the

election is not enjoined.

Even if plaintiffs ultimately prevail on the merits,

no election for the district which they espouse could be held

in 1988. For reasons set forth in detail below, it is

extremely unlikely that any such election could be held before

1990. That being the case, there was no need for the district

court to enjoin the 1988 election. If that election goes

forward as scheduled and plaintiffs later prevail on the

merits, the election scheduled in 1990 no doubt will be held

for the district advocated by plaintiffs, with the, 1990 justice

incumbent who resides in Orleans seeking reelection from that

district. In 1998, at the expiration of the ten year term of

the justice elected in 1988, an election would be held for the

other newly created (suburban) district. [There is no

complaint in this litigation by white majority voters that the

present system is unconstitutional or in violation of §2 of the

Voting Rights Act or that allowing the 1988 election to go

forward would in any respect injure their interests.]

Though the district court supported its order of

injunctive relief with a lengthy opinion, scant attention was

given therein to the defendants-' major argument, which is that

there is no irreparable injury which justifies an injunction

because the present system will allow for a black majority

district election in 1990, without the necessity of cancelling

any election. Nor did the district court offer any convincing

reasons for rejecting our alternative argument, which is that

the plaintiffs will not suffer irreparable injury if the

election is held because the results of that election could be

invalidated if plaintiffs prevail on the merits. In the brief

• • •

S

treatment which the district judge afforded the irreparable

harm issue (District Court Opinion Section II(A) at 24-27), he

acknowledged that an injunction will not provide any present

benefit or advantage to plaintiffs, but instead speculated that

plaintiffs might suffer future injuries if the election is not

enjoined. Id. at 25-26. For reasons set forth in detail

below, we submit that this speculation on the part of the trial

judge was unwarranted, and that allowing the 1988 election to

be held will not cause injury to plaintiffs, now or in the

future.

-11-

ARGUMENT

THE DISTRICT COURT'S DECISION TO ENJOIN THE 1988 ELECTION WAS

IN ERROR BECAUSE PLAINTIFFS HAVE FAILED TO MEET THE

FOUR-PRONGED TEST FOR A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION.

For the issuance of a preliminary injunction to be

appropriate, the plaintiffs are required to prove that:

(1) there is a substantial likelihood that

they will prevail on the merits;

(2) they will suffer irreparable injury if

an injunction does not issue;

(3) any such injury outweighs the harmful

effects of the injunction, and

(4) granting an injunction will serve the

public interest.

Canal Authority v. Callaway, 489 F. 2d 567, 572 (5th

Cir. 1974).

As set forth below, the case for enjoining the

election falls short on all four points, particularly so on the

question of irreparable harm.

-12- 1

(1) Plaintiffs' Likelihood of Success on

the Merits Is Dependent Upon How the United

States Supreme Court Rules On Defendants'

Application for Certiorari; There Is Also

Little or No Likelihood That Even If They

Prevail On the Merits, They Would Thereafter

Succeed In Causing An Election To Be Held In

A Black Majority District For the 1988 Seat

The threshold issue in this litigation is whether §2

of the Voting Rights Act applies to judicial elections

(plaintiffs do not rely on their constitutional claim,

unresolved up to now, as a ground for seeking injunctive

relief). The district court concluded that §2 does not apply

to judicial elections. This court reached a contrary

conclusion, and defendants will ask the United States Supreme

Court to consider the issue.

With all due deference and respect to this court's

ruling that S2 of the Voting Rights Act applies to judicial

elections, it cannot be denied that the issue is one of

national importance. The ultimate resolution of that issue

could have far-reaching consequences for the 38 states which

elect members of their judiciaries. As such, defendants submit

that it is likely that the United States Supreme Court will

grant their application for certiorari in order to resolve this

important issue. 3

3 The defendants' application for certiorari is in the

process of being prepared and will shortly be filed, well in

advance of the expiration of the 90 day period allowed for

filing.

Defendants do not, as the district court opinion

suggests (p. 17), ask any court to predict the "odds" that the

Supreme Court will act favorably to their position. Instead,

we simply point out that the real possibility that the Supreme

Court will conclude that §2 of the Voting Rights Act does not

apply to judicial elections argues against enjoining the 1988

election. Furthermore, and with due deference to the

three-judge panel, we submit that there is not a substantial

likelihood that plaintiffs will prevail on the merits and

thereafter succeed in causing a black majority district

election for the 1988 seat. (i.e., a substantial likelihood

that (1) the defendants' application for.certiorari will be

denied, or that the Supreme Court will grant certiorari but

affirm the panel's determination that §2 of the Act applies to

judicial elections, and that (2) a merits trial will result in

a determination that the present system violates the Act and

that (3) upon such a determination, the district court will

properly employ a remedy which will provide plaintiffs relief

that they would not be able to obtain unless the 1988 election

is enjoined (see the succeeding section of this brief)).

•

(2) Even If Plaintiffs Were To Establish A

Substantial Likelihood of Success on the Merits, They

Will Not Suffer Irreparable Injury If Their Injunction

Request is Denied [For:]

(A) If Plaintiffs Prevail on the Merits, the 1990

First Supreme Court District Election Could Be Held

For A Black Majority District.

Any analysis of the irreparable injury issue should be

prefaced by a consideration of two questions: (1) what do the

plaintiffs ultimately seek to achieve in this litigation, and

(2) when is it reasonably possible to expect that such relief

could be achieved? The Complaint, the briefs filed by the

plaintiffs on various issues, and the evidence placed in the

record at the district court's hearing on plaintiffs' motion

for a preliminary injunction provide clear answers to these

questions.

Plaintiffs desire to have created a new supreme court

district which would include .a portion of the present First

Supreme Court District and which would have a minority voter

registration of approximately 50%. See Plaintiffs' Complaint

at 5. Such a district would necessarily include most or all of

Orleans Parish.

-15-

At oral argument before the district court on

plaintiffs' motion for a preliminary injunction, plaintiffs'

counsel referred to the possibility of a remedy other than

dividing the present First District. Specifically, she raised

the possibility that the remedy, if plaintiffs' prevail, might

be elimination of the staggered terms but the continuity of the

present First District, with two justices being chosen in a.

limited vote option plurality election. 4 However, she was

quick to point out that she was not advocating such relief on

behalf of her clients, but merely pointing. out a potential

remedy which might be employed if plaintiffs prevail.

Such a remedy would seem extremely unlikely in this

case. While plurality elections may be appropriate remedies in

cases where a number of districts are simultaneously

reapportioned, such a remedy is unlikely here for, among other

4 The mechanics of such a remedy were not discussed in

detail at oral argument, but the limited vote option system

presumably would provide for one election for both First

Supreme Court seats, with each voter entitled to vote only for

one candidate and the two candidates who receive the highest

number of votes being elected.

reasons, it would produce an indefensibly peculiar method for

selecting the justices of the Louisiana Supreme Court (i.e.,

five of the supreme court districts in the state would elect

one justice, in each instance by majority vote and to staggered

terms, while the First Supreme Court district would elect two

justices simultaneously and then by what is essentially a

plurality vote). Defendants do not concede that the present

election system for the First Supreme Court District violates

the Voting Rights Act, but if it does, the obvious remedy would

be to split the current district into two-new districts. That

is the only remedy advanced in the plaintiffs' complaint (see

Plaintiffs' Complaint at 5).

The likely remedy if plaintiffs are successful on the

merits, then, is the election of a supreme court justice from a

newly created district which has a black voter majority and

which of necessity would consist of most or all of Orleans

Parish. Defendants submit that even if plaintiffs prevail on

the merits, the earliest that an election for the Orleans

district advocated by plaintiffs would be held is 1990,

regardless of whether the 1988 election is enjoined or not.

-17-

It is a certainty that no election for a newly created

district will be held in 1988. If plaintiffs do prevail on the

merits, possibly time would permit a special election for one

of the two new districts in 1989. This seems unlikely, for the

district court would probably be inclined to give the Louisiana

Legislature time to redraw the district itself, an option which

is always preferable to judicial redistricting. See Reynolds

•v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 585-86 (1964). However, even if a

special election were called in 1989, it would almost certainly

be for the new district that includes Jefferson Parish, where

the 1988 hold-over incumbent resides, rather than for the

Orleans-based district, where the 1990 incumbent resides. A

1989 election for an Orleans district would be manifestly

unfair to the 1988 hold-over incumbent, who resides in

Jefferson Parish and who also would be deprived by such an

election of the opportunity to run for re-election in a

district in which he resides. Furthermore, a special election

in 1989 for an Orleans district would also be unfair to the

1990 incumbent, who resides in Orleans Parish and who

-18-

S

presumably would be prevented by such an election from running

for reelection in the year 1990 (the concluding year of his

present term) from a district in which he resides. Surely

neither the federal district court nor the state legislature

would adopt a remedy which effectively gerrymanders both

incumbents, or one of the incumbents, out of the opportunity to

seek reelection, when a fairer alternative (holding the

election for the Orleans district in 1990) is readily

available. 5

5 Plaintiffs seem to be of the view that if the present

system violates §2 of the Voting Rights Act, it would be

fitting not to have an incumbent running in the first election

for the new district which they advocate. See Plaintiffs'

Reply Memorandum in Support of Motion (in the district court)

for a Preliminary Injunction at 10-11 n. 6. This argument has

no merit. Even if one were to assume (though defendants do

not) that the present system is in violation of §2 of the

Voting Rights Act as amended in 1982, both of the First

District incumbents were elected to the supreme court years

before that amendment, in fact the years 1974 and 1980

respectively, at a time when there did not exist the asserted

impediments created by the 1982 amendment to the Voting Rights

Act. For this reason, the district court was incorrect when it

stated (p. 25 of the opinion) that "the justice who won his

seat in 1974 [did so] under a voting system that at this

preliminary point has been determined to have been prima facie

illegal." There is no reason why either of the two longtime

incumbent justices for the First Supreme Court District should

be denied the right to run for re-election as incumbents.

Thus, whether a 1989 special election could be held or

not, it is highly probable that the first election for the

Orleans district would not be held until 1990. (In addition to

considerations of the parsihes of residence of the two

incumbents, other factors which make a 1989 special election

unlikely are the uncertain delays of litigation, as one can

only speculate as to when a final determination on the merits

will actually be made, and the "significant lead tiffe" which

plaintiffs assert will be required for any black candidate to

mount a serious campaign for a seat on the supreme court, see

Plaintiffs' Statement of Facts As to Which They Contend There

Is No Dispute, No. 64, and the district court opinion at 8).

That being the case, there is simply no need to enjoin the 1988

election, as there is already an election scheduled in 1990 in

which the incumbent is an Orleans resident, and that election

should be designated as the election for a new chiefly Orleans

Parish district.

Plaintiffs have argued in response to this contention

that regardless of whether an election is held for their

district in 1990, they would still suffer irreparable harm if

an election is held in 1988 under a system that dilutes black

voting strength. This is a highly theoretical argument at

best. Because plaintiffs have the same prospects for relief

regardless of whether the 1988 election is held (i.e., an

election for a black majority district in 1990), their

interests are not irreparably harmed if the 1988 election is

allowed to go forward and is followed in 1990 by an election

for a black voter majority district.

In fact, such a remedy would allow minority voters

(and candidates) the opportunity to participate in both the

regularly scheduled 1988 election, held for the present First

Supreme Court District, and a 1990 election held for the

_

minority district (if plaintiffs prevail on the merits). On

the other hand, if the 1988 election is cancelled, all voters

will be denied the opportunity to participate in the election

process.

The district court acknowledged that enjoining the

election provides no present advantage to black voters. See

District Court Opinion at 24-25. Further, the district court

provided only two reasons in support of its conclusion that

allowing the election to be held would cause plaintiffs

irreparable harm. First, the district court theorized that

allowing the 1988 election to go forward might have a future

detrimental impact on black candidates, in that the justice

elected in 1988 would have an undue advantage as a recently

elected incumbent in any subsequently held special election.

Id. at 26. Secondly, the district court stated that if the

1988 election is held, there would be no guarantee that the

1990 election would be held for the black majority district

rather than a newly created suburban district.

We respond to these contentions as follows. The

district court's reasoning regarding the supposed advantage to

the 1988 incumbent in a special election held shortly

thereafter is flawed in at least three major respects. First,

under the solution proposed herein if plaintiffs prevail on the

merits, the justice elected in 1988 would not have to run again

in a special election, for the 1990 election would then be held

for the majority black district. Because of the availability

of that remedy, there would be no need to overturn the results

of the 1988 election (a harsh remedy which is rarely employed

under any circumstances, as discussed in the section 2(B) of

this brief). Secondly, the district court assumed that the

justice elected in 1988 would be a candidate in any special

election called shortly thereafter for a black majority

district. Of course that would not be the case if, as likely,

the 1988 election were allowed to stand, but even if not and

elections for two new districts were called, there is no reason

to assume that the justice elected in 1988 would run in the

new, mainly Orleans District. Incidentally, as earlier noted,

the 1988 incumbent resides in Jefferson Parish, within the

suburban area, while the 1990 incumbent resides in Orleans

Parish, which is populated in part by the large majority of all

blacks who reside within the present First Supreme Court

District. Thirdly, even if the justice elected in 1988 were to

run shortly thereafter in a black majority district as a

recently elected four parish incumbent, it is sheer speculation

to say that incumbency under those circumstances would

constitute a significant or unfair advantage, and it is

possible that under those circumstances incumbency and the

recent election by a four parsih constituency could have

disadvantages.

The district court also expressed concern that the

1990 race would not necessarily be provided for a black

majority district, and that, instead, the choice of which new

district has the first election might be randomly made.

However, if this court reverses the trial court's order of

injunctive relief on the ground that, as argued by defendants,

an adequate remedy could be provided by an Orleans Parish race

in 1990, it is, if not a foregone conclusion, a virtual

certainty that the 1990 race would be so designated if

plaintiffs prevail on the merits.

(2)(B) Alternatively, Plaintiffs Will Not Suffer

Irreparable Injury if the 1988 Election Is Held

Because, if They Later Prevail on the Merits, the

Results of That Election Can Be Invalidated.

Our primary argument relative to the absence of

irreparable injury is discussed above (Section 2(A)). Our

alternative argument, however, is alone sufficient to warrant

reversing the district court's judgment; If this Court is not

swayed by our argument that a 1990 election in a black majority

chiefly Orleans Parish district would provide adequate and

timely relief for plaintiffs, we submit that the irreparable

harm prong is still so deficient as to warrant reversal of the

district court's order of injunctive relief, for there remains

the possibility that the results of the 1988 election can be

invalidated after the fact if plaintiffs prevail on the merits.

We emphasize that if this Court were to accept our

argument that an injunction should not issue because the 1990

election provides plaintiffs with the potential for an adequate

prospective remedy, then the results of the 1988

election almost surely would not be subsequently invalidated.

There would be no need to overturn past election results

because the 1990 election could be held for the black majority

district. Since this Court has repeatedly emphasized that the

power of federal courts to invalidate state elections is one

which should be guardedly exercised and employed only under

extreme circumstances, see Cook v. Luckett, 735 F.2d 912 (5th

Cir. 1984); Bell v. Southwel)., 376 F.2d 659, 662 (5th Cir.

1967); Hamer v. Campbell, 358 F.2d 215 (5th Cir. 1966),

certainly a prospective remedy which assigned the 1990 election

to a new black majority district and -leaves the 1988 election

results undisturbed would pass constitutional muster.

Incidentally, it is our respectful contention that Hamer is

readily distinguishable from this case, as it involved a

decision to overturn a state election under particularly

onerous circumstances, i.e., the outright deprivation of the

right of blacks to vote.

However, assuming that defendants are not correct with

respect to the foregoing, and that the ultimate result if the

election is not enjoined is that the results of that election

would subsequently be invalidated, this very fact, that the

election results will be invalidated if it is later deemed

necessary to do so, is all the more reason not to enjoin the

election. Because the election results can be subsequently

invalidated, our alternative argument is that there is simply

no irreparable harm which would be caused by allowing the

election to be held. From the perspective of the state's

judicial system, allowing the election to go forward despite

the risk of future invalidation is preferable to enjoining the

election, defendants respectfully submit.

This Court's per curiam opinion of May 27, 1984,

stated, in dicta, that "any election held under an election

scheme which this Court later finds to be unconstitutional or

in violation of the Voting Rights Act is subject to being set

aside and the office declared to be vacant." While the

district court seemed to interpret this comment as a suggestion

that the election should be enjoined to avoid the risk of

future invalidation, we submit that the panel's comment also

points to the fact that the possibility of subsequent

invalidation means that the plaintiffs will not be irreparably

harmed if the 1988 election is held. In any event, whatever

meaning was intended by the panel's dicta regarding the power

of federal courts to invalidate election results, the question

of whether the 1988 election should be enjoined is now squarely

before this court, and one reason the election should not be

enjoined is that allowing it to be held would not cause

plaintiffs irreparable harm since the election results could,

if necessary, be invalidated.

(3) The Benefits, if Any of An Injunction,

Are Far Outweighed by the Damaging Effects

of Cancelling The Election

There are some serious consequences which will ensue

if this Court cancels the 1988 election.

First, the normal operation of state law--here, an

election required by the Louisiana Constitution--will be

disrupted by a federal court injunction in a suit which not

only has not yet gone to trial, but in which there has been no

final determination of the threshold issue (whether §2 applies

to judicial elections), an issue which will be reviewed on

certiorari application by the United States Supreme Court.

Second, the voters within the current First Supreme

Court District will be totally deprived in 1988 of their right

to choose by election a justice of the Louisiana Supreme

Court. Although those voters would be able to participate in a

special election at some point in the future if the election is

cancelled, the right to vote, or to otherwise participate in

the political process, should not be delayed absent extreme

circumstances.

Third, the candidates who have been preparing to

qualify for the 1988 race would be adversely affected if an

injunction issues at this late stage. The efforts which they

have made in this 1988 election, see affidavit of Justice

Pascal F. Calogero, Jr., Exhibit 4 to Defendants' Opposition to

Plaintiffs' Motion (in the District court) for a Preliminary

Injunction, will be undercut if the election is delayed.

Plaintiffs attempt to minimize the disadvantages to

the 1988 candidates by suggesting that any harm suffered by

them is inconsequential when balanced against the federally

protected interests of black voters, No doubt both incumbent

First Supreme Court District justices will take no issue with

that assertion. The simple fact is, however, that the

interests of black voters can be protected without enjoining

the election. That being the case, the harm that an injunction

will cause to individual candidates should be given some

weight. Plaintiffs also suggest that the potential candidates

have been on notice since the institution of this suit in 1986

that an order enjoining the 1988 election would be sought.

This is a totally irrelevant point, as in the real world

candidates for public office cannot suspend their

preparations and then campaign on the possibility of judicial

intervention (candidates have been particularly disinclined to

do so in this case, since the plaintiffs' complaint was met

with a successful motion to dismiss and their claims were only

reinstated this Spring when a panel of this Court reversed the

district court judgment).

Fourth, the term of the justice who holds the 1988

seat expires at the end of this year. Even if, as apparently

permitted by La. R.S. 42:2, the term of that justice is

extended until such time as a special election is held, 6 the

6 .Because the Louisiana Constitution makes no provision

for the extension of a supreme court justice's term, the

validity of a hold-over justice's votes might be subject to

challenge, a disturbing possibility considering the important

cases which the Louisiana Supreme Court routinely considers,

such as death penalty cases, and the fact that such cases may

sometimes be decided by 4-3 votes. See Defendants Memorandum

in Opposition to Plaintiffs' Motion (in the District Court) for

a Preliminary Injunction at pp. 16-17, and affidavit of Gregory

Pechukas, attached thereto. In response to this argument, the

district court alluded to the fact that Art. 5, S22(B) of the

Louisiana Constitution provides that the state supreme court

may appoint judges to fill judicial vacancies. However, it

seems highly unkikely that this article was intended to apply

in a situation where an election has been enjoined and the

incumbent's term expires, for the article provides that any

judge appointed to fill a vacancy cannot run for that judgeship

in the next election. Application of that article in this

context would force the sitting incumbent to leave office

before having the opportunity to run for reelection or to

accept an appointment to an interim judgeship (if offered) at

the penalty of being unable to seek reelection. Such an absurd

and unjust result surely could not be countenanced by any court.

fact is that the voters of the First Supreme Court District

will, after December 31, 1988, be deprived of an elected

justice serving in the position and voting on the many

important cases that are considered by the Louisiana Supreme

Court. Regardless of whether the configuration of the present

district is ultimately changed as a result of this litigation,

and even if the 1988 election results were to be invalidated,

the sounder approach is to have an elected justice serving

until such a change is made, rather than a justice who is

appointed, or whose term is extended by court decree.

Fifth, the state's interests in conducting elections

under its own constitution and laws are entitled to deference

from the federal judiciary, in that a state election should not

be enjoined unless there are compelling reasons for doing so.

Granted, the federal judiciary has the power to intercede in

the state electoral process, but when, as here, plaintiffs will

not suffer irreparable injury, that power should not be

exercised.

The damaging consequences of an injunction thus

outweigh any advantages which plaintiffs would gain from

cancelling the 1988 election, particularly since, as discussed

above, plaintiffs can achieve their ultimate goal in this

litigation even if the 1988 election goes forward. Considering

the overall circumstances of the case and the adverse

consequences of an injunction, the district court erred by

granting plaintiffs' request for a preliminary injunction.

In the landmark reapportionment case of Reynolds v.

Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964), the Supreme Court recognized that

federal courts have the discretion not to enjoin pending state

elections even after there has been a determination that the

districting scheme for the pending election is unconstitutional:

However, under certain circumstances, such

as when an impending election is imminent

and a State's election machinery is already

in progress, equitable considerations might

justify a court in withholding the granting

of immediately effective relief in.a

legislative apportionment case, even though

the existing apportionment scheme was found

invalid. In awarding or withholding

immediate relief, a court is entitled to and

should consider the proximity of a

forthcoming election and the mechanics and

complexities of a state's election laws, and

should act and rely upon general equitable

principles. With respect to the timing of

relief, a court can reasonably endeavor to

avoid a disruption of the election process

which might result from requiring

precipitate changes that could make

unreasonable or embarrassing demands on a

state in adjusting to the requirements of

the court's decree. As stated by Mr.

Justice Douglas, concurring in Baker v.

Carr, "any relief accorded can be fashioned

in the light of well-known principles of

equity." 377 U.S. at 585-86.

The Reynolds Court went on to commend the district court for

initially declining to stay a pending election until the state

legislature "had been given an opportunity to remedy the

admitted discrepancies in the State's legislative apportionment

scheme." Id.

If the Supreme Court expressed reluctance to enjoin

elections when the existing apportionment system had been found

unconstitutional, surely any federal court should harbor even

greater reluctance to cancel state elections when, as here,

there has been no final determination that the challenged

system is in violation of the Voting Rights Act or is

unconstitutional (constitutionality has not been reached at all

in this litigation, and plaintiffs do not seek a preliminary

injunction on the strength of constitutional claim), and where,

even if plaintiffs succeed in their claim that the Voting

Rights Act has been violated, their remedy need not affect the

district to which the successful 198-8 cindfdate later

assigned.

As the Fifth Circuit's recent memorandum .ruling in

this case points out, an injunction should be sought at the

district court level. For that reason most of the decisions

involving injunctive relief are district court decisions. A

review of those decisions makes clear that federal district

courts have been extremely reluctant to cancel state elections

and have frequently declined to do so upon considering the

equities of the case.

In Dillard v. Crenshaw County, 640 F. Supp. 1247 (M.D.

Ala. 1986), a group of black citizens sought injunctive relief

pursuant to §2 of the Voting Rights Act. Dillard involved an

action challenging at-large systems used to elect county

commissioners in Alabama. There the Court agreed that the

plaintiffs had proven a likelihood of success on the merits,

and that their prima facie case on the merits had been

unrebutted. Nevertheless, the court refused to enjoin or

postpone the scheduled elections, stating:

The court does not wish to be left in the

position of having either to extend the

terms of incumbents or to appoint temporary

replacements to serve until the new plans

are in place. Both alternatives would

effectively deny the entire electorate the

right to vote and thus seem to offend basic

principles of representative government.

Id. at 1363. (Emphasis added.)

Banks v. Board of Education, 659 F. Supp. 394 (C.D.

Ill. 1987), also involved a request for injunctive relief

pursuant to §2. This was a class action on behalf of all

blacks registered or eligible to register to vote challenging

election procedures for several local bodies in the Peoria,

Illinois, area. Once again the district court refused to

enjoin the election, holding as follows:

Assuming, however, that the plaintiffs could

show a reasonable likelihood of success in

proving their voting rights claim prior to

the April 7 election, the Court would not be

in a position to remedy this possible

violation until it had made a decision after

a complete trial on the merits and had the

opportunity to consider possible forms of

relief. Thus, if the Court were to enjoin

the April 7 election, the Court would

necessarily have to extend the terms of the

present office holders until after a trial

is held....In the meantime, the black voters

of Peoria would be no better off because

they would still be represented by the

public officials currently in office,

elected under the system they claim is

illegal. On the other hand, enjoining the

April 7 election would have the effect of

preventing all of the voters in the

respective election districts from

exercising their right to vote and elect new

representatives this year. (Emphasis added)

Id. at 403.

After considering these factors and others, the

district court concluded that "the best answer is to allow the

election...to go forward so that the public officials whose

terms are due to expire can be replaced and so that the

election procedures, already substantially in place, will not

be made disruptive or made useless." Id. The court

specifically noted that enjoining the election "would not serve

the public interest because it would disrupt an election

process already well advanced toward election day and deprive

all of the citizens of the respective voting districts of their

right to replace public officials whose terms will be expiring

soon." Id. at 404.

-34-

The considerations which led the Banks court to deny

injunctive relief are also present in this case. Enjoining the

election would not provide relief to any of the estimated

506,177 registered voters within the First Supreme Court

District. Instead, those voters would be denied their right to

participate in the regularly scheduled 1988 election. And to

what purpose? If plaintiffs had to wait another ten years to

obtain relief (assuming that they are able to prevail on the

merits), their argument for pre-election injunctive relief

might be more compelling. However, because (1) plaintiffs will

likely obtain such relief through an election for a new

district in 1990, without the necessity of delaying the 1988

election (or overturning the results thereof, as discussed in

the next section of this brief), because (2) plaintiffs do not

desire a 1988 election, nor, we submit a 1989 election if with

inadequate lead time for black candidates to participate

therein, and because (3)prospective change in the system which

gives them relief in 1990 rather than 1989 is likely and will

surely pass constitutional muster, the argument for injunctive

relief is not compelling at all.

The district court also refused to enjoin an election

in Knox v. Milwaukee County Board of Election Commissioners,

581 F.Supp. 399 (E.D. Wis. 1984). The court noted in that S2

case that an injunction would disenfranchise nearly one million

voters. The court concluded "that the prejudice created by an

injunction here would be of the highest magnitude." Id. at 405.

As noted in plaintiffs' brief to the district court in

support of the motion for a preliminary injunction, there are

instances in which district courts have enjoined elections as

the result of challenges being brought under the Voting Rights

Act. No one denies that federal district courts have that

power. However, "[t]he proper focus" of the district court's

inquiry in each case "is upon the balancing of the equities"

involved, and "the public interest which is affected by such a

remedy." Banks, supra, 659 F. Supp. at 404. Also, the Callaway

test for injunctive relief will be satisfied in some factual

contexts and not in others. Given the particular facts and

equities involved in this case, particularly the fact that

plaintiffs will no doubt achieve an adequate remedy in 1990

without the necessity of enjoining any election, the Callaway

requirements for injunctive relief are not satisfied here. For

example, peculiar facts existed in Taylor v. Haywood County,

544 F.Supp. 1122 (W.D. Tenn. 1982), a case cited by the

plaintiff. There Haywood County had employed single member

districts for the Board of Highway Commissioners since 1937.

After the 1980 census, the county adopted an at-large

commission system. The court noted that "It is interesting to

note that this new reapportionment plan was adopted shortly

after an increase in complaints by black citizens over the

conditions of roads in the districts." Id. at 1135. Here,

however, as discussed at the outset of this brief, the method

of electing supreme court justices has existed for many years

(approximately 109 years) and is not a new scheme allegedly

devised to dilute black votes.

Given the particular facts and equities involved in

this case, particularly the fact that plaintiffs if successful

will achieve their remedy just as soon (in the year 1990)

without enjoining the 1988 election, the Callaway requirements

for injunctive relief are not satisfied here. 7

7 Defendants incorporate by reference here the arguments

raised at pp. 2-8 of their district court brief in opposition

to plaintiffs' motion for a preliminary injunction, regarding

the need to protect the integrity of the election system

required by the Louisiana Constitution and the potential impact

which the resolution of this case may have on the judicial

selection systems of other states. Amicus curiae briefs filed

herein by John A. Dixon, Jr., Chief Justice of the Louisiana

Supreme Court, and Pascal F. Calogero, Jr., Associate Justice

of the Louisiana Supreme Court, set forth additional equitable

and legal considerations which weigh against enjoining the 1988

election. See also, however, the amicus curiae briefs filed by

Justice Walter F. Marcus, Jr.

fl

In considering the harm that an injunction would cause

defendants, the district court's only reasons for concluding

that no significant harm would, result were that (1) there is no

showing of harm to the actual defendants, the governor,

secretary of state and commissioner of elections, other than

possibly the expense of a special election, and that (2) the

governor's duty to uphold the law includes the need to protect

the rights of black voters.

This analysis entirely misses the point. There is no

suggestion that enjoining the election would cause harm to the

personal interests of the named defendants, or that the cost of

a special election overrides federal constitutional rights.

The defendants do not appear in their individual capacities, as

voting machine operators, or as state auditors, but as

representatives of the people 'of Louisiana and all voters of

the . First District. The over 500,000 voters in that district

will be totally denied the right to participate in the

scheduled election if the injunction is upheld. This is the

harm to defendants which must be balanced against the asserted

advantages of an injunction. Enjoining the election is a

drastic remedy, and defendants have a duty to uphold state law

in a case where the intervention of the federal judiciary is

not required in order to vindicate constitutional rights.

(Th (4) An Injunction Would Not Serve the

Public Interest

The damaging consequences of cancelling the election,

as discussed above, obviously would not serve the public

interest. Unless the district court's ruling is reversed, the

voters of the First Supreme Court District will be denied the

right to participate in the 1988 election, and will at best be

left with a hold-over or appointed justice, alternatives which

"offend basic principles of representative government."

Dillard v. Crenshaw County, supra, 640 F.Supp. at 1263.

The district court concluded that the public interest

would be disserved if the 1988 election were to be set aside at

some point .in the future. First of all, as argued above, there

is no reason to believe that the election would be set aside.

We assume that this Court will agree with our argument that

assigning the 1990 election to a black majority district will

provide plaintiffs with an adequate prospective remedy.

Secondly, as also set forth above, even if invalidation of the

1988 election were to occur, that would be preferable, from

the perspective of the state's judicial system, to enjoining

the election.

The district court further concluded that even if the

Supreme Court reverses on the issue of the applicability of the

Voting Rights Act, or even if plaintiffs lose on the merits, it

is appropriate to enjoin the 1988 election because the

possibility of a later invalidation of that election will

dampen the interest in 1988 of both the voters and the

potential opponents of the 1988 incumbent. The answer to that

contention is almost self-evident. A legal, constitutional and

proper state election cannot be aborted because of the impact

that non-meritorious litigation might have on potential

candidates and voters. If it were otherwise, an injunction

against pending elections would be automatic whenever a

reapportionment suit is filed, and that is certainly not the

law.

The district court also was of the view that allowing

the election to go forward would be adverse to the public

interest because of the advantages which the justice elected in

1988 would have if that justice were to run shortly thereafter

in a special election (recent campaign publicity, etc.). As

discussed above (in the irreparable injury section of this

brief) this is not an adequate reason for enjoining the

election, because (1) there would be no need for such a special

election if this Court accepts the view that the plaintiffs

will be provided an adequate prospective remedy in 1990; (2)

even if such an election were required, there is no reason to

assume that the justice elected in 1988 would be a candidate in

the black majority district, or (3) that the advantage of

running as an incumbent in such a special election would

necessarily exist.

Further, the district court stated -that no candidate

has a legally cognizable interest in seeking election from a

district which has a configuration that violates the Voting

Rights Act. We have three responses. First, it would be more

accurate to say that no candidate has a legal right to seek

election or to be elected from a district to the prejudice of

the constitutional rights of black voters or other minorities.

That is not the case here, however, for as discussed above a

1988 election would not prejudice the rights of such voters

when followed by an election for a black majority district in

1990. Secondly, the Supreme Court in Reynolds v. Sims

explicitly recognized that pending state elections can go

forward even after a finding that the districts in question are

drawn in violation of the Constitution and ultimately must be

reapportioned, as long as the possibility of adequate

prospective relief is present. If the Court had been of the

view that no election can ever be held under a districting

system that is about to be reapportioned, it would have said

so. Instead, it specifically made clear that such is not the

case. Thus candidates in such an election do have a legally

cognizable interest, that is, an interest in running for

office. Third, the authority cited by the district court on

this issue, Morial V. Judiciary Commission of the State of

Louisiana, 565 F. 2d 295 (5th Cir. 1977)(en banc), cert.denied,

435 U.S. 1013 (1978), simply does not discuss the issue in any

detail, and is not on point. In fact, Morial recognizes the

importance of protecting an individual's right to seek elective

office, and to that extent supports defendants' contention that

the rights of those who seek_to_run_in_1988 should not be

disregarded unless there are compelling reasons for doing so.

The district court also posited that allowing the

justice elected in 1988 to serve a full ten year term. would

constitute a disservice to the voters of the white majority

suburban area, who, he assumes, would object to having a

justice who is elected from the present four parish area

serving them until 1998. This consideration does not present

the necessary compelling need to enjoin the 1988 election, as

representatives of white voters in the suburban areas have not

intervened or otherwise appeared in this litigation. They do

not complain therefore, either that they constitute a minority

(which of course they could not, whether in the four parishes

or only in the three suburban parishes) or that the system

violates the Voting Rights Act or unconstitutionally dilutes

their voting strength.

CONCLUSION

The district court need not, and should not have

enjoined the 1988 election for the First Supreme Court

District. The United States Supreme Court may still rule in

this matter adversely to plaintiffs, and in all events

plaintiffs' success on the merits will not likely include a

black majority district election for the 1988 seat, factors

which cast uncertainty on their alleged "likelihood of success"

on the merits. But even if it were assumed, for the sake of

argument, that plaintiffs have established a likelihood of

success on the merits, they have not established irreparable

injury. In fact, even if plaintiffs ultimately prevail on the

merits, the present system of scheduled elections for the First

Supreme Court District would allow the court to fashion an

adequate prospective remedy without the necessity of enjoining

the 1988 election, nor invalidating the election to be held in

1988. Alternatively, allowing the 1988 election to be held

would not cause irreparable injury to plaintiffs because if

they later prevail on the merits, the election results could be

invalidated.

Under these circumstances, there is no justification

for telling over five hundred thousand registered voters within

the First Supreme Court District that they cannot exercise the

right they would otherwise have, to vote in the scheduled 1988

election, and instead must wait to vote until such time as this

case is resolved on the merits. Instead, the 1988 election

should go forward, as scheduled.

. For these reasons, defendants respectfully submit that

the district court's ruling of July 7, 1988 should be reversed.

All of the above and foregoing is thus respectfully

submitted.

WILLIAM J. GUSTE, JR.

ATTORNEY GENERAL

Louisiana Dept. of Justice

234 Loyola Avenue

New Orleans,'La. 70112

(504) 568-5575 -

M. TRUMAN WOODWARD, JR.

909 Poydras, Suite 2300

New Orleans, La. 70130

BLAKE G, ARATA

201 St. Charles Avenue

New Orleans, La. 70130

By:

A.R. CHRISTOVICH

1900 American Bank Bldg.

New Orleans, La. 70130

MOISE W. DENNERY

601 PoydraS Street

New Orleans, La. 70130

kZO. ERT G. PUGH

`.eid Counsel

330 Marshall Street, Suite 1200

Shreveport, La. 71101

(318) 227-2270

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I HEREBY CERTIFY that a copy of the foregoing

appellant brief has this day been served upon the plaintiffs

through their counsel of record:

William P. Quigley, Esquire

631 St. Charles Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Julius L. Chambers, Esquire

Charles Stephen Ralston, Esquire

C. Lard Guinier, Esquire

Ms. Pamela S. Karlan

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

Roy Rodney, Esquire

643 Camp Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Ron Wilson, Esquire

Richards Building, Suite 310

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70112

by depositing the same in the United States Mail, postage

prepaid, properly addressed. All parties required to be served

have been served.

Shreveport, Caddo Parish, Louisiana, this the / 7 day

of July, 1988.

Robert G. Pugh,

Lead Counsel