Valentino v. United States Postal Service Motion for Leave to File Brief and Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

April 26, 1982

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Valentino v. United States Postal Service Motion for Leave to File Brief and Brief Amici Curiae, 1982. 03c444f8-c79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/86f40e31-6462-4a6e-b573-fb88c93dba4c/valentino-v-united-states-postal-service-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-and-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

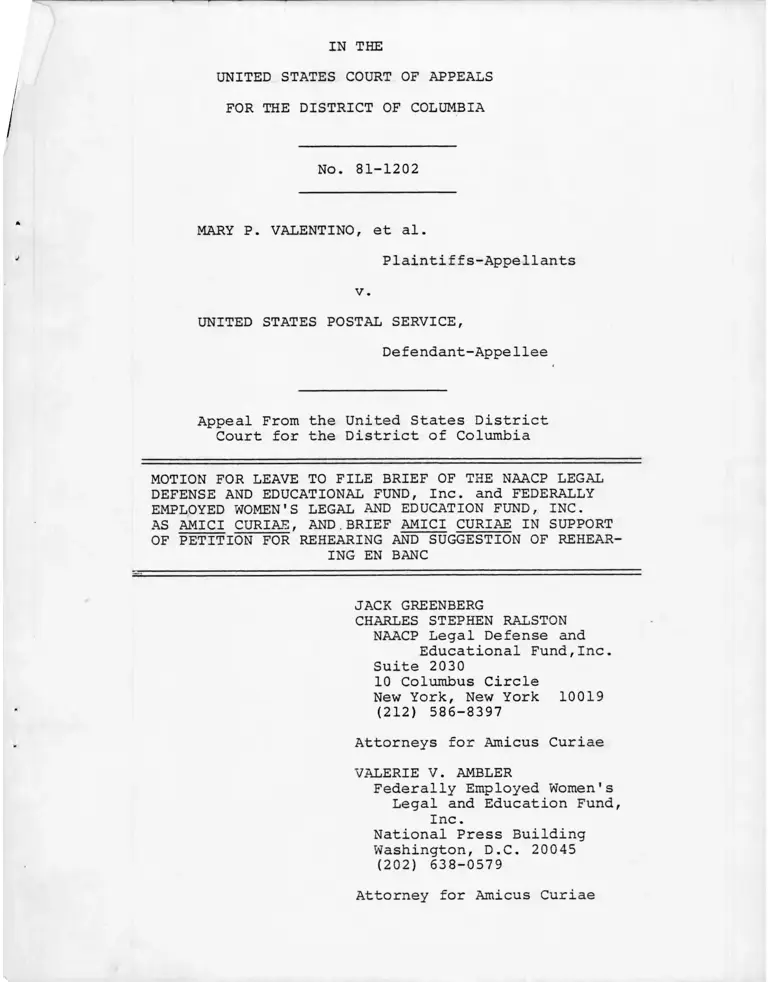

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

No. 81-1202

MARY P. VALENTINO, et al.

Plaintiffs-Appellants

v.

UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE,

Defendant-Appellee

Appeal From the United States District

Court for the District of Columbia

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, Inc. and FEDERALLY

EMPLOYED WOMEN'S LEGAL AND EDUCATION FUND, INC.

AS AMICI CURIAE, AND.BRIEF AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT

OF PETITION FOR REHEARING AND SUGGESTION OF REHEAR

ING EN BANC

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund,Inc.

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

VALERIE V. AMBLER

Federally Employed Women's

Legal and Education Fund,

Inc.

National Press Building

Washington, D.C. 20045

(202) 638-0579

Attorney for Amicus Curiae

INDEX

Page

Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae ... 1

Brief Amici Curiae ............................ 1

I. The Practical Impact of the

Panel Decision ..................... 2

II. The Decision Conflicts With The

Decision of Another Panel of

This Court, With Other Courts of

Appeals, and Is Inconsistent With

The Legislative History of The

Act .................................. 8

A. The Decision Relating

to The Applicable

Time Period ................. 8

B. The Standard for Establish

ing a Prima Facie Case ..... 10

C. The Legislative History

of The 1972 Act .. .......... 11

Conclusion ..................................... 13

Certificate of Service 14

Table of Authorities

Page

Cases;

Barrett v. United States Civil Service Commission,

69 F.R.D. 544 (D.D.C. 1975) .................... 9

Chewning v. Schlesinger, 471 F.Supp 767

(D.D.C.1979) ................................... 9

*Chisholm v. United States Postal Service,

665 F. 2d 482 (4th Cir. 1981)................... 9,10

Clark v. Chasen, 619 F.2d 1330 (9th Cir. 1980) ... 13

*Davis v. Califano, 613 F.2d 957(D.C. Cir. 1980) 6,8,10

EEOC v. American National Bank, 652 F.2d 1176

(4th Cir. 1981) 11

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d

398 (5th Cir. 1974)............................. 10

Hackley v. Roudebush, 520 F.2d 108 (D.C. Cir. 1975) 13

Hill v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400 (1942) 7

Luevano v. Campbell, 27 FEP Cases 721 (D.D.C.1981) 4

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 (1974) 12

*Neal v. Delaware, 103 U.S. 370 (1881) 7

Parker v. Califano, 561 F.2d 320 (D.C. Cir. 1977) 7

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) 8,10

Wilkins v. University of Houston, 654 F.2d 388

(5th Cir. 1981) ................................ 5

Williams v. T.V.A., 552 F.2d 691 (6th Cir. 1977).. 9

* Cases Principally Relied Upon.

Pa^e

Other Authorities

Bartholet.Application of Title VII to Jobs

in High Places, 95 Harv. L. Rev. 947

(1982) ............................... 8

Federal Personnel Manual, Chapter 335 .... 3

5 C.F.R. § 713.251 (1977) 9

H. Rep. No. 92-238 (92nd Cong., 1st Sess.,

1971) 12

S. Rep. No. 92-415 (92nd Cong., 1st Sess.

1971) 12

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

No. 81-1202

MARY P. VALENTINO, et al.

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE,

Defendant-Appellee.

Appeal From the United States District

Court for the District of Columbia

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICI CURIAE ON BE

HALF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC. and THE FEDERALLY EMPLOYED WOMEN'S LEGAL

AND EDUCATION FUND, INC.

Movants NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc. and Federally Employed Women's Legal

and Education Fund, Inc. move the Court for permission to

file the attached brief amicus curiae, in support of the

petition for rehearing and suggestion for rehearing en

banc for the following reasons. The reasons assigned

also disclose the interest of amici.

(1) Movant NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc. is a non-profit corporation,

incorporated under the laws of the State of

New York in 1939. It was formed to assist

Blacks to secure their constitutional rights

by the prosecution of lawsuits. Its charter

declares that its purposes include rendering

legal aid gratuitously to Blacks suffering

injustice by reason of race who are unable,

on account of poverty, to employ legal counsel

on their own behalf. The charter was approved

by a New York Court, authorizing the organization

to serve as a legal aid society. The NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund Inc. (LDF),

is independent of other organizations and is

supported by contributions from the public.

For many years its attorneys have represented

parties and has participated as amicus curiae

in the federal courts in cases involving many

facets of the law.

(2) Attorneys employed by movant LDF have represented

plaintiffs in many cases arising under Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in both individual

cases, e.g., McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411

U.S. 792 (1973); Furnco Constitution Corp. v.

Waters, 438 U.S. 567 (1978); and in class actions,

e.g., Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975); Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co., 424 U.S.

2

747 (1976). They have appeared before this

Court in a variety of Title VII cases involv

ing agencies of the federal government both

as counsel for plaintiffs, e.g. , Foster v .

Boorstin, 561 F.2d 340 (D.C. Cir. 1977), and

as amicus curiae, Hackley v. Roudebush, 520

F.2d 108 (D.C. Cir. 1975); Davis v. Califano,

613 F.2d 957 (D.C. Cir. 1980).

(3) Staff attorneys for movant have represented

plaintiffs in Title VII class action litigation

pending decision in the District Court for the

District of Columbia. Thus, they both have a

direct interest in the standards by which such

cases are decided and experience and familiarity

with the issues raised in federal Title VII cases.

(4) Movant Federal Employed Women's Legal and

Education Fund, Inc. is a non-profit organization,

incorporated in 1977 under the laws of the District

of Columbia. It was established to undertake

legal, educational, and research activities in

order to eliminate unlawful discrimination in the

federal government on the basis of race, sex,

religion, national origin, age, handicap, and

lawful political affiliation.

3

(5) Movant FEW LEF was established because of the

special problems federal employees were encounter

ing in eliminating unlawful employment discrimina

tion. Faced with myriad laws, rules, and

regulations,persons complaining had difficulty

bringing their claims and finding representation.

(6) The Board of Directors of movant FEW LEF

consists of federal attorneys, EEO officials,

complainants, other federal employees, and

attorneys not federally employed who have

extensive experience in the area of federal equal

employment opportunity. These Directors have

been involved in the various aspects of federal

employee complaint processing and litigation.

(7) Through their extensive participation in Title VII

cases, amici have acquired substantial expertise

in issues concerning the burden of proof and the

application of these standards for deciding Title VII

class actions, the issues in the present case

addressed by the attached brief. Therefore, we

believe that our views on the important questions

before this Court will be helpful to their resolution.

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons we move that the

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. and the Federally

4

Employed Women's Legal and Education Fund, Inc. be given

leave to file the attached brief amici curiae.

Respectfully submitted

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

VALERIE V. AMBLER

Federally Employed Women's

Legal and Education Fund,Inc.

National Press Building

Washington, D.C. 20045

(202) 638-0579

Attorney for Amicus Curiae

5

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

No. 81-1202

MARY P. VALENTINO, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appeallants,

v.

UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE,

Defendant-Appellee.

Appeal From the United States District

Court for the District of Columbia

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC. and the FEDERALLY EMPLOYED WOMEN'S

LEGAL AND EDUCATION FUND, INC. AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR REHEARING AND SUGGES

TION OF REHEARING EN BANC

As discussed in the motion for leave to file

this brief, amici are civil rights organizations with

a particular interest in the litigation of class action

Title VII suits against federal government agencies in

the District of Columbia and elsewhere. Attorneys

employed by or associated with amici have been involved

in cases which have either gone to trial or are in pre

paration for trial. Thus, the standards they must meet

to establish a prima facie case of disparate treatment

are of particular importance to them.

We urge that the present case be reheard because the

rules laid down in the panel decision impose nearly insurmount

able burdens on plaintiffs in light of the typical job structure

in most federal agencies and the data reasonably available

to plaintiffs. We also believe that its rules are inconsistent

with those of prior decisions of the Court, the decisions of

other courts of appeals, and, indeed, with the legislative

history of Section 717 of the Equal Employment Opportunity

Act of 1972 which made Title VII applicable in full to federal

agencies.

I.

The Practical Impact of the Panel Decision

The panel is critical of all of plaintiffs' evidence

on the ground that it does not control for qualifications

related to specific jobs at the Postal Service. It notes

that the matching up of qualifications to jobs may impose

an onerous or difficult burden and acknowledges that here

the burden "was especially difficult to meet." Amici

respectfully suggest that this was an understatement.

If the intention of the Court is that persons' qualifications

be matched up job—by—job, then for most federal agencies the

burden imposed just to make out a prima facie case would

be so onerous as to make it unfeasible to successfully litigate

these cases.

2

While it is true that in a typical federal agency there

are some specialized jobs, such as attorneys, engineers,

economists, etc., the large bulk of GS, white collar jobs

are substantially different. They are general professional,

administrative, and managerial positions for which no specific

training or educational standards are imposed as minimal

qualifications. If one examines Manual X-118, which contains

the qualification standards for jobs in the federal government

as developed by the Office of Personnel Management, the entry

level for many of such jobs requires only a general education.

For example, the Multi-Group Standard for Administrative

Positions, which is used to fill many types of jobs depending on

the agency, has both general experience and specialized

experience requirements depending on the grade level at which the

individual is to be found eligible. Education can substitute

for general experience so that a person with a college degree

in any field has the minimum qualifications to enter such a job

at the GS-5 level with no other experience, education, or train

ing required. The individual then may progress through accumulat

ing experience on the job all the way to the GS-15 level both

without competition, if he or she is in a career ladder series,

1/or with competition if he or she reaches the top of a career ladder.

— Whether or not an agency establishes a career ladder and

how high up it goes (often to the GS-12 level) is totally within

the agency's discretion. Seev Federal Personnel Manual, Chapter

335.

3

Many of the jobs in the federal sector have such minimal

2/

requirements. Thus, in a typical agency a comparison of GS

level by educational level, i.e., whether or not someone has a

bachelor's degree, higher than a bachelor's degree, high school

education, etc., will provide a valid comparison of those persons

having the minimal qualifications for a large proportion of the

jobs.

If, then, the Court here is merely indicating that there

should be some generalized division in a statistical analysis

between positions which may require specialized degrees (in those

instances where there are a substantial proportion of such

positions at an agency)and those that do not, then that may be

done simply by looking at such job categories independently of

other jobs. Such an approach would not be particularly burden

some, could be done when necessary, and, indeed, was done by plaintiff

here, as explained in the petition for rehearing.

Unfortunately, however,' the Court's decision hints at

much more. By citing the Fifth Circuit's decision in Wilkins v.

2/ Thus, for supervisory and management positions in areas

involving no specific technical requirements, there are no

specific education or training qualifications. Rather the

minimum qualifications are in terms of broadly stated "supervisory

or managerial abilities" and experience.

Similarly, the 118 jobs covered by the PACE examination have

as the minimum qualifications for entry at the GS-5 level a college

degree in any one of many fields, three years professional

experience, or a combination of experience and education less then

a degree. The job fields include, inter alia, bond sales _

promotion (GS-011), outdoor recreation specialist (GS-023), history

(GS-170), personnel management (GS-201), computer specialist trainee

(GS-334), administrative officer (GS-341), budget and accounting

(GS-504), paralegal specialist (GS-950), and a variety of claims

examiners (GS-990-997). See,Luevano v. Campbell, 27 FEP Cases

721 (D.D.C. 1981) .

4

University of Houston, 654 F.2d 388 (1981), it suggests that

statistical analysis, where there are a large number of dif

ferent jobs, is inappropriate unless there is a close matching

of the specific qualifications of each group to the myriad of

different jobs. In a typical class action against a federal

agency, however, this would be difficult, to the point of near

impossibility, to do without unlimited resources on the part

of plaintiffs.

The usual starting point in one of these cases is to serve

extensive interrogatories asking for a variety of information.

A typical response of the agency is to proffer computer tapes on

which have been entered employee data. What is on those tapes

varies from agency to agency, but it is unusual to find on them

anything like the particularized information the Court here seems

to require. Rather, educational information will be limited to

number of years or level of education, viz., completion of high

school, some college, college degree, graduate degree, etc.

The use of these tapes by the litigants has obvious,

advantages, since it expedites greatly discovery and the eventual

trial of the case. Moreover, many agencies retain on computer

tapes information relating to employees after they have left.

Therefore, the tapes provide much data not currently available in

the employer's personnel files since, unlike private employers,

federal agencies do not retain the personnel records of departed

employees. If employees go to another federal agency their

official personnel files go with them and tracking them down

5

may be difficult in the extreme. If they leave the federal

service, their OPF's are sent to the federal record center and

their retrieval also takes time.

It is only from these official personnel files that, in

most instances, the type of data which the Court seems to contemplate

3/

in Valentino may be available, since many agencies also do not

retain for long periods of time application forms (Standard Form

171s) on which detailed information relating to type of degree,

subjects studied, etc., is found, except insofar as copies are

placed in OPFs.

Assembling this information, organizing it, key punching it,

computerizing it, and then matching it all up would be a job of

staggering proportions, and one far beyond anything that plaintiffs

may be expected to do to establish a prima facie case of discrimina

tion. If such data can disprove a prima facie case (e.g., if

the agency can show that it has indeed carefully matched up persons

with their qualifications), then the employer, with its easier

access to the data, its ability to retrieve it, and its responsibility

for it not being present, should bear that burden. Davis v.

Califano, 613 F.2d 957, 964 (D.C. Cir. 1980). Put bluntly,

the decision here can be read to impose obligations on plaintiffs

that would price them out of class action litigation against

federal agencies. If merely establishing a prima facie case,

3/ This type of data is not necessarily to be found even in

OPFs, since agencies do not routinely survey their employees to

update education data. In one case recently tried by counsel

for amici, the computer data base had no information regarding

the education of more than 10% of its employees.

6

let alone being prepared to meet its rebuttal, would cost upwards

of $100,000. or more, neither private plaintiffs nor civil rights

organizations of limited resources will be able to bring more than

4/

a handful of cases.

In short, amici urge strongly that these Title VII cases

be governed by the same principles laid down by the Supreme Court

over a hundred years ago when it first established the principle

of the prima facie case. In Neal v. Delaware, 103 U.S. 370 (1881),

the Court rejected the state's argument that a defendant challeng

ing the exclusion of blacks from juries had the burden of showing

that the pattern shown by the statistical evidence was the result of

discriminatory actions by the selecting officials. Once the pattern

had been shown, a prima facie case had been made out, and it was

the state's burden to prove its contention that the reason for

the disparities was because blacks were less qualified for

jury service. 103 U.S. at 397. Indeed the Court has rejected

reliance on generalized population data that tended to show that

blacks had higher crime rates, etc., to explain statistical

disparities on the ground that blacks were less qualified. Hill

v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400 (1942).

4/ By using existing computer data bases, plaintiffs can

reasonably expect to prepare and present a case at costs of

up to $50,000, including expert witness fees. If they must

search out, assemble, and computerize large amounts of additional

data, expenses could easily double. Of course, as noted by

this Court in another context, court enforcement of Title VII

against federal agencies is solely up to private litigants.

There is no EEOC,Department of Justice, or OFCCP to act as

public attorney-general. Parker v. Califano, 561 F.2d 320,

331 (D.C. Cir. 1977).

7

In Title VII cases also, plaintiffs are entitled to rely

on the presumption underlying the statute — that in a fair,sex

or race neutral employment situation, women or minorities would

be equitably distributed throughout the workforce. Davis v .

Califano, 613 F.2d at 965; Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S.

324, 339 n. 20 (1977). If they are not, the burden should shift

to the employer to come forward with a legally sufficient

explanation for the phenomenon. As a recent commentator has

persuasively argued, these principles apply with the same force

to higher level white collar positions as they do to blue collar

industrial jobs. There is no basis in either the statute or the

realities of the work force to apply different or more stringent

standards of proof to the former compared to those that have long

applied to the latter. See, Bartholet, Application of Title VII

to Jobs In High Places, 95 Harv. L. Rev. 947 (1982).

II.

The Decision Conflicts With The Decision

nf another Panel of this Court, With Other

Courts of Appeals,and Is Inconsistent With

The Legislative History of the Act.

A. The Decision Relating to The Applicable

Time Period.

The panel opinion applies decisions governing the private

sector relating to the appropriate time period for filing an

administrative complaint to federal sector cases. (SI. op.,

pp. 11-12). In so going, it conflicts with the approach taken

8

by the Fourth Circuit in Chisholm v. United States Postal Service,

665 F.2d 482 (4th Cir. 1981). In Chisholm the Court pointed out

that there is no statutory time established for the filing of an

administrative complaint for federal employees. Rather, the

time periods that are established are administrative, and, there

fore, the court held that the two-year period set out in the

statute for calculating back pay should govern. See also,

Chewning v. Schlesinger, 471 F. Supp. 767 (D.D.C. 1979). The

conclusion that the 30-day administrative time period should not

control the scope of a class action is particularly appropriate

in light of the history of the federal regulatory scheme. When

plaintiff here went to an EEO counsellor in June of 1976, there

was no provision for filing a class discrimination claim

administratively. See, Barrett v. United States Civil Service

Commission, 69 F.R.D. 544 (D.D.C. 1975); Williams v. T.V.A.,

552 F.2d 691 (6th Cir. 1977). Despite the order in Barrett it

was not until April, 1977, that the Civil Service Commission

promulgated regulations allowing the filing of class discrimination

5/

claims. Therefore, it is inappropriate in a class action case

to apply a limitation which under the existing regulations governed

only individual claims.

The panel decision is also inconsistent with the many

cases in which courts have relied on historical evidence to find

5/ The procedures permitted class-type claims to be raised

by organizations as "third-party" allegations of discrimimation,

5 C.F.R. § 713.251 (1977). There were no time limits in which

such claims had to be filed. Back pay and other corrective

action could be obtained.

9

class-wide discrimination. See, e.g., Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324, 337-338, 341, n.21 (1977)(in case filed

in 1971, evidence relating to hiring practices as far back as

1950 introduced, including hiring patterns beginning in 1965

(n. 21), and testimony of individual minorities going back to

1967; Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d 398, 410-11

(5th Cir. 1974), rev'd on other grounds, 424 U.S. 747 (1976) (EEOC

complaint filed 1968; evidence going back to July 1965 — the

effective date of Title VII — relied upon); Chisholm v. U.S.P.S.,

516 F. Supp. 810, 819-822, 824-25, 852-857 (W.D.N.C. 1980), aff'd,

665 F.2d 482 (4th Cir. 1981) (complaint filed 1972; evidence going

back to 1962 relied upon).

B. The Standard for Establishing a Prima

Facie Case.

Amici urge that the approach taken by the panel in this

case is fundamentally at odds with that taken in Davis v. Califano,

613 F.2d 957 (D.C. Cir. 1980). The Court focuses on one phrase

in Davis, but fails to follow its general approach, which is that

a detailed explanation of differences in promotion rates, etc.,

should be the burden of the employer, which has full access to the

information bearing on such issues. 613 F.2d at 964. As we

have discussed above, the imposition of the burden on plaintiff at

the point of establishing a prima facie case is both inequitable

and unrealistic.

-10

The panel decision here essentially holds that the statistical

evidence showing a maldistribution among grades of men and women

at the Postal Service is entitled to little or no weight. This is

also contrary to Davis, which specifically holds that such statis

tics, which it terms "Category One," are probative and relevant,

even when specialized occupations are combined with other jobs.

613 F.2d at 960, 963, 964, n. 43, and 964-965. It is only for

the "Category Two" promotion statistics that Davis holds it was

necessary to compare those with "minimal objective qualifications.

The panel decision's approach is also inconsistent with decisions

of other circuits such as EEOC v. American National Bank, 652

F.2d 1176 (4th Cir. 1981), which holds that such statistics establish

a prima facie case.

C. The Legislative History of the 1972 Act.

The panel's denigration of general grade distribution data

also fails to recognize that it was precisely this type of evidence

that led Congress to conclude that Title VII had to be amended by

the inclusion of § 717 in the first place. Thus, Congress found

in the concentration of blacks and women in the lower grade levels

evidence both of employment discrimination and of failure of

existing programs to bring about equal employment opportunity.

The House Report stated:

Statistical evidence shows that minorities

and women continue to be excluded from large

numbers of government jobs, particularly at the

higher government levels . . . .

11

This disproportionate distribution of

minorities and women throughout the Federal

bureaucracy and their exclusion from higher

level policy-making and supervisory positions

indicates the government's failure to pursue

its policy of equal opportunity.

H. Rep. No. 92-238 (92nd Cong., 1st Sess., 1971) p. 23. The

House Report went on to refer to the "entrenched discrimination

in the Federal Service," based on these same statistics. Id.

at 24.

The Senate report also included statistics which showed

the concentration of women and minorities in the lower grade

levels, and concluded that this indicated "that their ability

to advance to the higher grade levels has been restricted."6/

S. Rep. No. 92-415 (92nd Cong., 1st Sess.) pp. 13-14. The

Supreme Court cited the language of the House Report quoted

above in its discussion of the reasons why § 717 was passed.

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535, 546, at n. 22 (1974).

As this Court has itself held, in 1972 Congress was

deeply concerned with the "government's abysmal record in minority

6/ Thus, the Senate Report set out a table with data strikingly

¥imilar to that discounted here, showing the distribution by

percentages of women by grade level in federal agencies:

GS-1 through GS-6 .................. 76.7%

GS-7 through GS-12 ................. 21.7%

GS-13 and above .................... 1.1%

A similar table was set out giving the grade distribution of

minorities. Id. at 13.

12

employment" and with the "rooting out of every vestige of

employment discrimination within the federal government."

Hackley v. Roudebush, 520 F.2d 108, 124, 136 (D.C. Cir. 1975).

See also, Clark v. Chasen, 619 F.2d 1330, 1332 (9th Cir. 1980).

These concerns sprung directly from the statistics this Court

now rejects. Surely if such evidence was sufficient to

convince Congress that § 717 was necessary in the first place,

it cannot now be held irrelevant or of little weight to the

proof of a violation' of the same law.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons,rehearing should be granted

and the decision below reversed.

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

VALERIE V. AMBLER

Federally Employed Women's

Legal and Education Fund,Inc.

National Press Building

Washington, D.C. 20045

(202) 638-0579

Attorney for Amicus Curiae

13

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that copies of the foregoing

motion and brief have been served on all the parties

herein by depositing the same, first class postage pre

paid, in the United States mail addressed as follows:

Stephen N. Shulman, Esq.

11 Dupont Circle, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

William H. Briggs, Jr.

Assistant United States Attorney

U.S. Courthouse

3rd and Constitution Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20001

Done this 26th

day of April,1982.