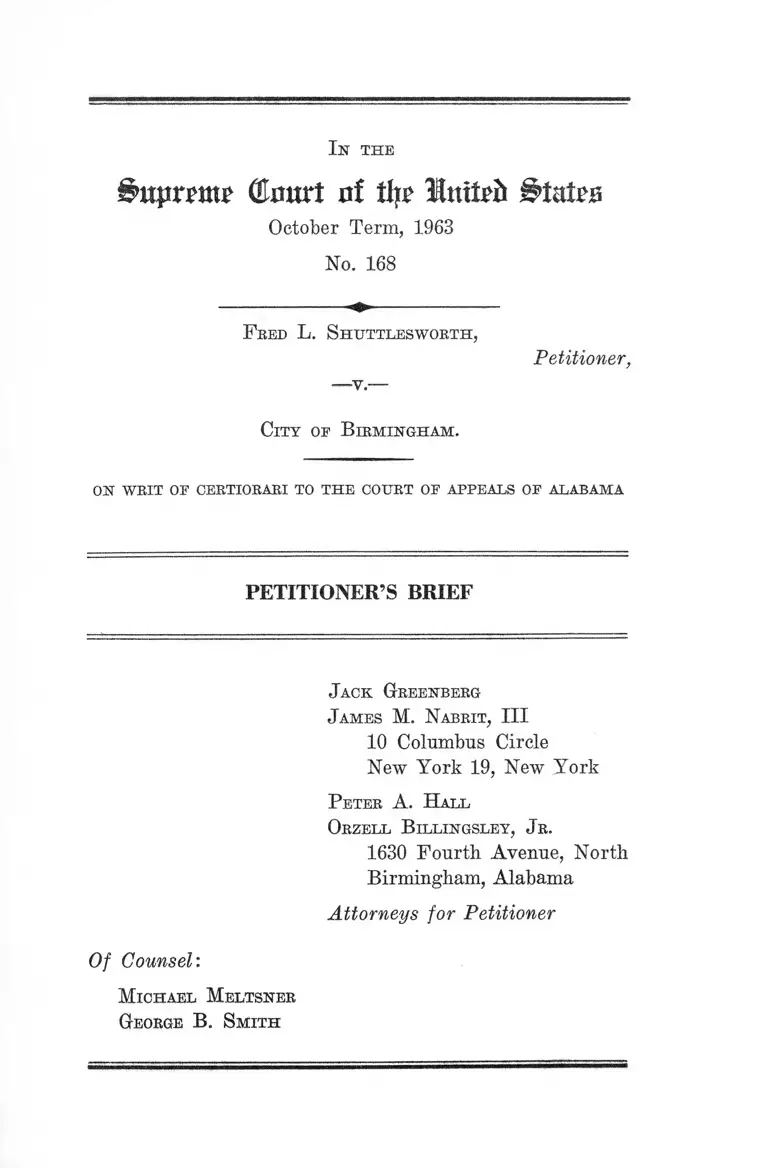

Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Petitioner Brief

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1963

40 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Petitioner Brief, 1963. c3ba8654-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8707aaad-03de-4a0b-8f60-5a386895b935/shuttlesworth-v-birmingham-al-petitioner-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

B n p x m ? (dourt of % Mtttfrd & > U U s

October Term, 1963

No. 168

F eed L. Shuttlesworth,

Petitioner,

City of B irmingham.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE COURT OF APPEALS OF ALABAMA

PETITIONER’S BRIEF

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Peter A. H all

Orzell B illingsley, Jr.

1630 Fourth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Petitioner

Of Counsel:

M ichael Meltsner

George B. Smith

I N D E X

Opinions Below ........................................ .......... .......... . 1

Jurisdiction .......................... 1

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved....... 2

Questions Presented ........ ............ .......................... .......... 3

Statement of the Case ...................................................... 4

Summary of Argument ........ ............................ ...... ....... 10

A rgument............ 13

I. Petitioner Was Denied Due Process in That

He Was Convicted of a Crime on a Record De

void of Evidence of G uilt.................................... 13

II. The Law Under Which Petitioner Was Con

victed Is Unconstitutionally Vague and Fails

to Warn That Petitioner’s Conduct Is Made

Criminal ..... 19

III. Petitioner’s Conviction Was Affirmed Under a

Criminal Statute, the Violation of Which Had

Not Been Charged, Contrary to the Due Proc

ess Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States ..... ......... 20

IV. This Court Is Not Precluded From Reviewing

the Judgment of the Court of Appeals of Ala

bama Where the Supreme Court of Alabama

Refused to Consider the Merits Because the

Certiorari Petition Filed There Was Not on

“ Transcript Paper” ........................................ ..... 22

PAGE

Conclusion 33

11

T able oe Cases:

Accardo v. State, 268 Ala. 293, 105 So. 2d 865 (1958) .... 26

American R. Express Co. v. Levee, 263 U. S. 19 ........... 22, 23

Andersen v. United States, 132 A. 2d 155 (D. C. Mun.

Ct.), aff’d 253 F. 2d 335 (D. C. Cir. 1957) ...... 18

Anderson v. Alabama, 364 U. S. 877 ........... . 23

Aust v. Sumter Farm & Stock Co., 209 Ala. 669, 96 So.

2d 872 (1923) .......................... ............. ....... ........ ........ 26,27

Bates v. General Steel Tank Co., 36 Ala. App. 261, 55

So. 2d 218 (1951) ................ ........ ..... ......... ............ . 27

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454 ......................... ....... 15

Brady v. Brady, 144 Ala. 414, 39 So. 237 (1905) ______ 26

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 ................................ . 15

Burton v. State, 8 Ala. App. 295, 62 So. 394 (1913) ....... 17

Carter v. Texas, 177 U. S. 442 ............ ..... ...................... . 31

City of Montgomery v. Mott, 266 Ala. 422, 96 So. 2d 766

(1957) ________ ________________________ 29

Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S. 196.................... '.....11, 20, 21, 22

Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U. S. 385 .... 20

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ............. .............. ................ 15

Daniels v. Milstead, 221 Ala. 353, 128 So. 447 (1930) .... 15

Edge v. Bice, 263 Ala. 273, 82 So. 2d 252 (1955) ........... 29

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 ................. ..... 20

Elks Lodge v. State, 264 Ala. 223, 86 So. 2d 396 (1956) .. 27

Ex parte Jackson, 212 Ala. 496, 103 So. 558 (1925) ....... 26

Ex parte Nations, 154 So. 2d 762 (1963) ............... . 28

Ex parte Tower Manufacturing Co., 103 Ala. 415, 15

So. 836 (1893) ............ ........ ....... ........ ........... ................ 26

Ex parte Wood, 215 Ala. 280, 110 So. 409 (1926) .......... 27

PAGE

I l l

Flournoy v. State, 270 Ala. 448,120 So. 2d 124 (1960) .... 17

PAGE

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157............ ..... ...... .13,15, 22

Gates Lumber Co. v. Givens, 181 Ala. 670, 61 So. 30

(1913) ............................................... ................................ 29

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 .................................... 15

Gober v. Birmingham, 373 U. S. 374 ........................... 23

Hammerstein v, Superior Court, 341 U. S. 491 .....26, 31, 32

Henry v. United States, 361 U. S. 9 8 .............................. 16

Houston v. State, 265 Ala. 588, 93 So. 2d 439 (1957) .... 27

Hunter v. L. & N. R. R. Co., 150 Ala. 594, 43 So. 802

(1907) ...................................... ..................... ........ .......... 29

Jemison v. State, 270 Ala. 589,120 So. 2d 751 (1960) .... 28

Kennedy v. State, 39 Ala. App. 676, 107 So. 2d 913

(1958) .......................... ....... ............ ........... ............ . 18

Ker v. California, 374 U. S. 2 3 .......................................... 16

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451...... ....... ...... ..... 19, 20

McMaster v. Gould, 276 U. S. 284 .................................. 32

Maddox v. City of Birmingham, 255 Ala. 440, 52 So. 2d

166 (1951)......................................................................... 27

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. S. 643 ........................... .................. 16

Metropolitan Life Ins. Co. v. Korneghy, 260 Ala. 521,

71 So. 2d 301 (1954) ........... 26

Mitchell v. Helms, 270 Ala. 8, 115 So, 2d 664 (1959) __ 28

Morgan Plan Co. v. Beverly, 255 Ala. 235, 51 So. 2d 179

(1951) ............................................................................... 28

Naler v. State, 25 Ala. App. 486, 148 So. 880 (1933) .... 17

Nesmith v. Alford, 318 F. 2d 110 (5th Cir. 1963) ........... 16

IV

Paterno v. Lyons, 334 U. S. 314 .................................... 22

Patterson v. Sylacauga, 40 Ala. App. 239, 111 So. 2d 25

(1959) ........... ..................... ...... ........ ..................... .. 17

Patton v. Colbert County, 265 Ala. 682, 92 So. 2d 691

(1957) ................ ....... ..................... ................. ............... 29

Peterson v. State, 248 Ala. 179, 27 So. 2d 30 (1946)____ 26

Pugh v. Hardyman, 151 Ala. 248, 44 So. 389 (1907) ....... 29

Quinn v. Hannon, 262 Ala. 630, 80 So. 2d 239 (1955) .... 29

Redwine v. State, 36 Ala. App. 560, 61 So. 2d 715

(1952) ........................................... .................................... 30

Rogers v. Alabama, 192 U. S. 226 ..... ..... .......................25, 31

Schmale v. Bolte, 255 Ala. 115, 50 So. 2d 262 (1951) ..... 29

Shuttlesworth v. Alabama, 373 U. S. 262 ...................... 23

Simmons v. Cochran, 252 Ala. 461, 41 So. 2d 579

(1949) ........ ................................................. ..................... 29

Southern Electric Co. v. Stoddard, 269 U. S. 186...... . 22

Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313 ........................... ...... ....25, 31

Stovall v. State, 257 Ala. 116, 57 So. 2d 642 (1952) ...... 27

Tarver v. State, 43 Ala. 354 (1869) ___ 17

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154 ;.................... .......... 13,15

Taylor v. State, 27 Ala. App. 538, 175 So. 698 (1937) .... 17

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199______13,18,

19, 22

United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co., 255 U. S. 81 .... 20

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U. S. 375 ............................ ..... 28

Wilson v. Howard, 266 Ala. 636, 98 So. 2d 425 (1957) .... 29

W olf v. Colorado, 338 U. S. 25 ............... ...................... 16

Wood v. Wood, 263 Ala. 384, 82 So. 2d 556 (1955) ___ 29

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 ...................... ....... 15,16,19

PAGE

V

Statutes and R ules :

28 United States Code, §1257 ......... 22

28 United States Code, §1257(3) ....................... 1

Alabama Constitution of 1901, §140...... ..... .................... 23

Alabama Code, Title 13, §86............ 23

Alabama Code, Title 14, §33 .......................... 17

Alabama Code, Title 15, §153......................... 15

Alabama Code, Title 15, §154............................................ 15

Alabama Supreme Court Rule 8 ...................................... 30

Alabama Supreme Court Rule 21 .... 25

Alabama Supreme Court Rule 32, Appx, to Tit. 7, Ala.

Code 1958 ................................. ............................2,10, 24, 26

Alabama Supreme Court Rule 39, Appx. to Tit. 7, Ala.

Code 1958 ........................................................................23, 30

General City Code of Birmingham of 1944, § 4 ............... 2

PAGE

General City Code of Birmingham of 1944, §825 ....2, 9,13,

17.19, 20, 21

General City Code of Birmingham of 1944, §856 ....2, 4, 9,10,

13.14.19, 20

Other A uthorities :

1963 Report of United States Commission on Civil

Rights ............................................................................... 25

Mr. Justice Douglas, “Vagrancy & Arrest on Suspi

cion” , 70 Yale L. J. 1 ...... ............. ..... ...... ..................... 16

Jones, Alabama Practice and Forms, §§6392, 6393....... 30

Rosenberg & Weinstein, Elements of Civil Procedure

(Foundation Press, 1962) ............................................ 30

In t h e

n p x x n x x ( to r t a! % Inttrtu B t n t x B

October Term, 1963

No. 168

F eed L. Shuttlesworth,

■v.-

Petitioner,

City of Birmingham.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE COURT OF APPEALS OF ALABAMA

PETITIONER’S BRIEF

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals of Alabama (R. 59-

60) is reported at 149 So. 2d 921. The opinion of the Su

preme Court of Alabama (R. 65) is reported at 149 So. 2d

923.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals of Alabama (R.

58) was entered on October 23, 1962. An order overruling

an application for rehearing in that court was entered No

vember 20, 1962 (R. 61). A petition for writ of certiorari

filed in the Supreme Court of Alabama was stricken on

December 20, 1962 (R. 67) and an application for rehear

ing in that court was overruled February 28, 1963 (R. 67).

The jurisdiction of this Court rests on 28 United States

Code, Section 1257(3), petitioner having asserted below

and claiming here the deprivation of rights, privileges and

2

immunities secured by the Constitution of the United

States. The petition for certiorari in this Court was filed

May 29, 1963, and certiorari was granted October 14, 1963

(E. 68).

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

2. This case also involves Section 856 of the General

City Code of Birmingham.

“Any person who knowingly and wilfully opposes

or resists any officer of the city in executing, or at

tempting to make any lawful arrest, or in the dis

charge of any legal duty, or who in any way interferes

with, hinders or prevents, or offers, or endeavors to

interfere with, hinder or prevent such officer from dis

charging his duty, shall, on conviction be punished as

provided in section 4.” *

3. This case also involves Section 825 of the General

City Code of Birmingham.

“ Any person who commits an assault, or an assault

and battery, upon another person, shall, on conviction,

be punished as provided in section 4.”

4. This case also involves Rule 32 of the Revised Rules

of Practice in the Supreme Court of Alabama (Code of

Alabama, 1958, Appendix to Title 7, p. 1172).

# Section 4 of the City Code provides, inter alia, for punish

ment “by a_ fine not exceeding one hundred dollars, or by im

prisonment in the city jail, workhouse or house of correction or

at hard labor upon the streets or public works for not exceeding

six months, or by both such fine and imprisonment. . . . ”

3

■'‘Buie 32. Paper of Applications for Bail, Manda

mus, etc., Must Correspond with Transcript.

All applications to this court to admit bail, or for the

writ of habeas corpus, mandamus, or other writ or

process depending on motion of this court, together

with all papers and proceedings touching the same,

shall be presented on folio paper, of the pattern now

required by the rule for ordinary transcripts, so that

the same may be in suitable form for binding; and no

application shall be heard that is not so presented.”

Questions Presented

1. Whether petitioner was denied due process of law

by his conviction on a record devoid of any evidence of

guilt?

2. Whether petitioner was denied due process in that he

was convicted under a law which failed to give fair warn

ing that his conduct was prohibited?

3. Whether petitioner was denied due process of law

when he was charged, tried and convicted under a law pro

hibiting interfering with a police officer, but the conviction

was affirmed on appeal, on the ground that he had com

mitted another crime for which the same sentence might

be imposed, i.e., assault, even though there had been no ac

cusation or trial on the issue of assault?

4. Whether there is an adequate non-federal ground

which precludes review in this Court where the Alabama

Court of Appeals ruled against petitioner on the merits,

but the Alabama Supreme Court struck a petition for writ

of certiorari that sought to invoke its discretionary juris

diction on the ground that the petition was on the wrong

size paper?

Statement of the Case

Petitioner, Reverend Fred L. Shuttlesworth, was arrested

May 17,1961, at the Greyhound Bus Station in Birmingham,

Alabama, and charged with violating Section 856, General

City Code of Birmingham of 1944. The complaint filed

against him in the Circuit Court of the Tenth Judicial Cir

cuit of Alabama1 charged that he (R. 4 ):

. . . did knowingly and wilfully interfere with, hinder,

or prevent a police officer of the City of Birmingham;

namely, Jamie Moore, Police Chief for the City of

Birmingham, in the discharge of his legal duty in that

said defendant did knowingly and wilfully place him

self between said officers and a group of people com

monly called “ freedom riders” when said people were

being placed in protective custody by said officer, and

said defendant did knowingly and wilfully refuse to

■ move out of the way of said police officer after being

so ordered, contrary to and in violation of Section 856

of the General City Code of Birmingham of 1944.

On the day in question, Reverend Shuttlesworth, pastor

of a Birmingham church and a well known civil rights

leader there (R. 46-47), went to the bus station with a group

of persons referred to in testimony as “ freedom riders.”

The group, eighteen or more persons, including petitioner,

had tickets for bus travel to Montgomery, Alabama, and

arrived at the terminal between two and three o’clock in the

afternoon. A crowd had gathered in nearby streets and

about thirty to forty police officers were on duty in the

area (R. 28-29). Police Captain Garrison said that the

1 Petitioner was originally charged and convicted of the same

offense in the Recorder’s Court of the City of Birmingham. He

was sentenced to pay $100 fine and to perform hard labor for

180 days in that court. Upon posting an appeal bond (R. 3), he

obtained a trial de novo in the Circuit Court.

5

crowd had a “belligerent” attitude directed at the freedom

riders (B. 29), and he thought their lives were in danger

(B. 27). The police checked to see that all persons in the

station were passengers with tickets (B. 25, 28). Shuttles-

worth and his group had difficulty in getting transportation

when a driver refused to drive a bus scheduled to leave

between two and three o’clock (B. 43, 29); the group de

cided to wait for the next bus (B. 43).

At approximately four o ’clock Birmingham Police Chief

Jamie Moore went to the station and approached the group

on a loading platform. He s a i d w e n t out and told

that group of people in a voice loud enough to be heard

who I was, I identified myself, and told them that due to

the circumstances that day that I as Chief of Police was

arresting them and taking them into protective custody of

the City of Birmingham” (B. 15). According to the Chief,

Shuttlesworth, who had been at a pay phone, “ came on out

there about the time that I was talking to those people”

(B. 16). Then, in the Chief’s words (B. 16):

Well, he [Shuttlesworth] walked around to my left

right close to me and got eventually between—I say

eventually, it wasn’t a lot of time there, and I told him

to leave the bus station. I called him by his name, I

called him Fred, that he was not concerned with what

was happening there, and he walked around and then

got between me and some of those people I was talking

to and I believe I asked him to go—to get out of my

way, and he said, if those people have to be arrested,

why, he wanted to be arrested also.

The Chief then ordered that petitioner be taken into cus

tody. On cross-examination Chief Moore gave some slight

additional detail. He said that Shuttlesworth was two or

three feet away from him, that he spoke to Shuttlesworth

first, that petitioner did not put his hands on anyone, and

6

was not profane or loud (E. 18-19). Chief Moore testified

(E. 18):

A. I told him, “Fred— ” I called him Fred—I said,

“ You are not concerned in this. We are engaged in

business,” or words to that effect. “ You get out of my

way and don’t bother us.”

Q. Well, now, what occasioned you to speak to him

at that time? A. He was in my way and he was asking

what was happening, what was taking place, and 1 had

already announced to those people in a good loud clear

voice who I was and my intention.

Q. Now, did he do anything other than ask those

questions as to what was happening? A. He walked

around to my left and was between me and some of

those people.

Q. Did he do any other act? A. Your Honor, I

would like for him to ask specifically, if he will, what

he has in mind there.

Q. Did he do any physical act? Did he put his hands

on anyone? Did he do anything other than ask the

questions and walk around to your left? A. He didn’t

put his hands on anyone that I saw, if that is what you

are talking about.

Q. Was he profane, Chief, or loud? A. He wasn’t.

Q. Or argumentative? A. He was not profane.

Q. Was he loud and argumentative while talking to

you? A. I wouldn’t say he was loud.

It may be noted that there was no statement that Shut-

tlesworth blocked the Chief’s path or that the Chief was

trying to walk anywhere; the Chief merely said that peti

tioner “walked around and got between me and some of

the people I was talking to” (E. 16), and that “he was. in

my way and he was asking what was happening, what was

taking place” (E. 18-19).

7

The entire group was arrested without resistance (E. 26)

and taken to the City Jail,2 but no charge was made against

any member of the group except Shuttlesworth (E. 19, 54);

the rest of the group finally got a bus to Montgomery the

following Saturday (E. 23).

The testimony of police Captain Garrison who was stand

ing with Chief Moore at the time of the arrest was sub

stantially the same as the Chief’s. On cross, Captain Gar

rison was asked (E. 25):

Q. Did he at any time exhibit any pugnacious atti

tude? Did he put his hands on anyone or offer any

argument? A. Not verbally, but he didn’t move.

Q. But he asked what was going on and he didn’t

move ? A. To the best of my recollection he asked what

was going on and he did make the one statement that

if they were placed in jail he wanted to go too.

Another officer, Captain Warren, described the incident in

similar fashion,3 stating that neither the Chief nor the peti

tioner raised his voice in speaking to the other (E. 35).

2 One member of the group said that she was confined in the

City Jail for 12 hours before she was released without being

charged (R. 54).

3 Captain Warren testified (R. 34):

“A. The conversation, such as it was that took place between

Chief Moore and the Reverend Shuttlesworth was at the fore

front of the group of Freedom Riders. The Chief was at the

front of them at the bus and the Reverend Shuttlesworth was

there and the Chief endeavored then after he placed them

under protective custody to get them down the ramp toward

the waiting patrol wagon, and the Reverend Shuttlesworth

was in between the Chief and the Freedom Riders going along

with them after having been asked not to interfere.

Q. So, he was going along with them down the ramp? A.

That is correct.

Q. Towards the waiting patrol wagon? A. In that general

direction, yes.”

Police officer Trammell testified that when the Chief ad

dressed the group Shuttlesworth “ wanted to know why they

were being placed under protective custody” (E. 36); he

heard the Chief ask him to move out of the way but did not

recall whether petitioner did move (R. 37). He said that

the group was standing at a bus stall, apparently about to

board a bus, when the Chief came up ; and that he arrested

petitioner on instructions of his superior officer (R. 40).

Shuttlesworth testified that he was with the group when

Chief Moore walked up to them. His version of the con

versation was as follows (R. 43-44):

A. He identified himself and said, “ I am Chief Moore,”

or words to that effect, Chief of the Birmingham City

Police, and we have decided to arrest you all for your

own protection.”

And I asked him what did he say, and he said he

decided to arrest us for our own protection. And then

he recognized me in the crowd and he said, “ Shuttles

worth, are you with the group ?”

I said, “ I am. We have been trying to get the bus out

for two hours or more.”

And he said, “Well, you go on, I don’t want any

trouble out of you.”

And I said, “ I am with the group and I want to catch

a bus.” And he said, “ If you don’t go on, I will have to

arrest you.” And I said, “Well, whatever happens on

all them will happen to m e; we are all together.”

So, he asked—I don’t know— one of the officers to

arrest me, and they took me in the patrol car and the

rest of them in the wagon. We all started off about

the same time.

Testimony by defense witness Vera Brown was similar

(R. 53-54).

9

In short, all the witnesses agreed that petitioner was

entirely peaceful in his conduct and in his language; that

he did nothing to resist arrest or to stop his companions

from being arrested; and that he merely inquired why they

were being arrested and asked that he be treated as his

companions were. Neither the Chief nor any of the other

officers gave any indication why it was desired to arrest each

member of the group of freedom riders except Shuttles-

worth, and place them under “protective custody.”

On December 5, 1961, petitioner was tried before the

Circuit Court sitting without a jury and found “ guilty as

charged in the complaint” (R. 10). The trial court rendered

no opinion. Shuttlesworth was sentenced to 180 days at

hard labor and a $100 fine and costs. In default of payment

of the fine and costs he is to serve additional 52 day and

16 day periods at hard labor (R. 10-11).

Prior to, during, and after the trial petitioner made

appropriate motions objecting to the ordinance, the com

plaint, and the conviction on Fourteenth Amendment

grounds (Motion to Quash, R. 5-6; Demurrers, R. 7-8;

Motion to Exclude, R. 8-9); each of the motions was over

ruled (R. 9-10, 13, 42, 55). On appeal to the Court of Ap

peals of Alabama, petitioner assigned as errors the over

ruling of the motions mentioned above (R. 56). The Court

of Appeals affirmed in a brief opinion (R. 59-60), in which

it described “protective custody” as “ the receiving of some

one who places himself voluntarily under the protection of

a peace officer.” The Court mentioned petitioner’s argu

ment that the Chief was not acting in the discharge of any

legal duty but said that this argument “ can avail the appel

lant nothing, because his conduct was also that prohibited

by §825 of the City Code which provides for the same degree

of punishment as §856, §825 making it an offense against

the City for any person to commit an assault” (R. 60).

10

The Court referred to the common law definition of assault,

and said that “ it is our view that an assault is an offense

included in §856 in the alternative here pertinent” (E. 60).

The Court then concluded (E. 60) :

Inasmuch as Shuttlesworth blocked the chief’s path

using words from which the intent to do so “ in rudeness

or in anger” could probably and rationally be inferred,

there was no error in his conviction, since he could

have been clearly convicted of a simple assault.

After the Court of Appeals denied rehearing (E. 61),

Shuttlesworth petitioned the Supreme Court of Alabama to

grant a writ of certiorari (E. 62-64), and filed a brief to

which the City filed a reply brief likewise addressed to the

merits of the case. The Supreme Court of Alabama, how

ever, ordered that the petition for certiorari be stricken

because it was not filed on “ transcript paper” as required

by that court’s Eule 32 (E. 65), and denied rehearing

(E. 66).

Summary of Argument

Petitioner was denied due process of law secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment in that he was convicted of crime

without evidence of guilt. He was charged with interfering

with an officer in the exercise of his legal duty. The police,

however, were not exercising any legal duty when they

took freedom riders into “protective custody.” There ap

pears to have been no such concept as “protective custody”

in Alabama law, prior to petitioner’s arrest, but as defined

by the Alabama Court of Appeals, such custody contem

plates a voluntary surrender, which did not occur here. In

fact, the police illegally arrested freedom riders in the

exercise of federally protected rights. But beyond this,

petitioner did not, in fact, “ interfere” with the police in

11

whatever it was they were doing. He was merely politely

and quietly inquiring concerning their treatment of his

companions.

That petitioner was not guilty of “ interfering” may he

discerned from the fact that the Court of Appeals evaded

passing on the validity of the conviction for that offense,

but affirmed by holding petitioner guilty of the crime of

assault, which is punishable by the same penalty as inter

fering. But neither was there evidence of “ assault.” The

Alabama law of assault has heretofore involved some ele

ment of violence as indicated by the cases cited below.

There was, however, no violence here. Petitioner was held

to have committed an assault because he spoke in “ rudeness

and anger,” but neither is there any evidence that this oc

curred.

Moreover, the ordinances under which petitioner was

charged and convicted are unconstitutionally vague as ap

plied to his situation. Neither the ordinance dealing with

interfering with a police officer, not that forbidding assault

gives any notice that mere inquiry of a police officer as to

why he is arresting one’s companions in the lawful exercise

of their rights as bus passengers constitutes either the

crime for which petitioner was originally convicted or

the crime for which he was held guilty in the Court of

Appeals.

The conviction below also should be reversed because it

was affirmed under an ordinance, the violation of which had

not been charged, contrary to the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment. Petitioner was charged with in

terfering with the police officer but the conviction was af

firmed on the ground that he had committed an assault.

Cole v. Arkansas, 333 IT. S. 196, holds that it is as much a

violation of due process to send an accused to prison fol

lowing a conviction of a charge on which he was never tried

12

as it would be to convict him upon a charge that was never

made. Cole is directly in point.

This Court has jurisdiction to review the cause notwith

standing refusal by the Supreme Court of Alabama to re

view for the reason that the petition filed with it was not on

transcript paper. Certiorari in this case properly runs to

the Alabama Court of Appeals, the appellate court below

the State Supreme Court, and the highest court of the state

in which a review of right could be had. The Court of

Appeals heard and necessarily disposed of the constitu

tional claim. The State Supreme Court could have con

sidered the merits despite the procedural flaw but exercised

a discretionary power not to pass upon these claims, and

where it has discretion either to hear or not to hear, its

refusal to pass upon the federal questions cannot rob this

Court of jurisdiction. Moreover, its refusal was based upon

a highly formalistic and technical procedural rule which

has no relation to the decision making process, the rights of

the parties in this case, or the administration of the flow of

business in the Alabama courts as it affects the rights of

other litigants. The rule relating to the size of paper of

certiorari petitions is based upon the fact that the record

racks in the clerk’s office are of a certain size and relates to

binding of the record. There is no adequate and substantial

nonfederal ground which precludes review here.

Finally, the judgment of the Alabama Court of Appeals,

the highest court where review could be had as a matter of

right, is reviewable here notwithstanding the fact that the

Alabama Supreme Court may have declined to exercise its

discretionary certiorari jurisdiction because of an adequate

state law ground.

13

A R G U M E N T

I.

Petitioner Was Denied Due Process in That He Was

Convicted of a Crime on a Record Devoid of Evidence

of Guilt.

The judgment below should be reversed because there

was no evidence of petitioner’s guilt of any crime. Thomp

son v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199; Garner v. Louisiana, 368

U. S. 157; Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154.

Because of the peculiar treatment which the Alabama

Court of Appeals accorded this case—putting aside the

charge of interfering with an officer (Section 856) and find

ing petitioner guilty of another offense, i.e. assault (Section

825)—petitioner’s argument is divided as follows. First, it

will be demonstrated that there w’as no evidence that peti

tioner interfered with Chief Moore in the discharge of any

legal duty as charged in the complaint. Second, it will be

shown that there was no evidence that petitioner committed

an assault. In a subsequent portion of the argument (part

II), it will be shown that neither ordinance gave fair warn

ing that petitioner’s conduct was criminally punishable,

and that the conviction thus denies him due process on the

ground of vagueness. Then it will be urged (in part III

of the argument) that the affirmance of petitioner’s con

viction on the theory that he committed an assault—in

violation of an ordinance under which he had been neither

charged, tried, nor convicted—violated due process.

A careful review of the trial evidence leads to the in

escapable conclusion that there was no proof that petitioner

interfered with, hindered, or prevented Chief Moore from

discharging any legal duty. Indeed this failure of proof

14

might be surmised from the manner in which the opinion

of the Alabama Court of Appeals attempted to escape the

issue by holding petitioner guilty of another offense sub

ject to the same punishment. “ There was no error in his

conviction,” the Court of Appeals held, “ since he could

have been clearly convicted of a simple assault” (R. 60).

This attempt to circumvent the question of whether there

was evidence to sustain the charge under §856 is readily

explainable when it is considered that there was no evi

dence either that Chief Moore was performing any legal

duty or that Shuttlesworth interfered with, hindered, or

prevented its exercise. Chief Moore walked up to the

group of persons traveling with petitioner and announced

peremptorily that he “ was arresting them and taking them

into custody of the City of Birmingham” (R. 15). Peti

tioner, who according to the Chief arrived during this

announcement (R. 16) immediately walked up to the Chief

and asked “ what was happening,' what was taking place”

(R. 18-19). The Chief told Shuttlesworth “ to leave the bus

station” , “ to get out of my way” , and that “he was not

concerned with what was happening there” . When Shuttles

worth did not move, but responded by saying “ if those

people have to be arrested, why, he wanted to be arrested

also” (R. 16) then the Chief ordered him placed under

arrest and subsequently charged him under §856. Shuttles

worth and the group of freedom riders traveling with biin

were arrested without any resistance.

First, it is obvious that Chief Moore was not performing

a “ legal duty” or even a lawful act in purporting to arrest

Shuttlesworth’s companions for “protective custody” . No

such crime or concept as “ protective custody” appears in

the Birmingham or Alabama Codes. The Alabama Court of

Appeals said protective custody was “ the receiving of some

one who places himself voluntarily under the protection

15

of a peace officer” (R. 59). There is nothing in the record

to indicate that Chief Moore intended that the gronp would

have any choice—he told them that he “was arresting them”

(R. 15); nothing shows that they agreed to the custody.

Certainly if he was asking that the group voluntarily sub

mit to his custody for protection, petitioner’s questions as

to what was going on would have been entirely natural and

appropriate. But actually it rather plainly appears that

the group was given no choice about the matter, that the

arrest was unjustified, and that petitioner’s questions were

appropriate in the context of an unjustified arrest. It is

quite clear that the members of the group had violated no

law which justified an arrest by Chief Moore. They had

a right to use public buses without regard to racial seg

regation customs (Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454; Gayle

v. Browder, 352 IT. S. 903), and their right may not be

abridged on account of “ the possibility of disorder by

others” ( Wright v. Georgia, 373 IT. S. 284; Taylor v. Louisi

ana, 370 U. S. 154; Garner v. Louisiana, 368 IT. S. 157, 174;

ef. Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 80-81; Cooper v. Aaron,

358U. S .1).

As the freedom rider group had not committed any crime

—there has never been any claim that they did—their arrest

was unlawful. Alabama law authorizes arrests only under

warrant (Tit. 15, Ala. Code §153), or without a warrant

for offenses in the presence of an officer or where there is

“ reasonable cause” to believe the person has committed a

felony (Tit. 15, Ala. Code §154). See Daniels v. Milstead,

221 Ala. 353, 128 So. 447 (1930). The Fifth Circuit recently

said that “ There is yet no single Alabama case to indicate

that the suspected threat of mob violence at the hands of

the law breakers may be avoided by arresting those whose

actions are perfectly peaceful and legally and constitu

tionally protected merely because such lawful and peaceful

conduct provocatively incites the incipient mob.” Nesmith

16

v. Alford, 318 F. 2d 110, 120 (5th Cir. 1963). Whatever the

Alabama law governing arrests without warrants might be,

surely there was nothing in the freedom riders’ peacefully

waiting for a bus that could meet the test of “probable

cause” embodied in the Fourth Amendment (Henry v.

United States, 361 U. S. 98,102) and made applicable to the

states by the due process clause of the Fourteenth ( Wolf

v. Colorado, 338 U. S. 25; Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. S. 643;

K er v. California, 374 U. S. 23). The Fourth Amendment

no more permits arrests for “ protective custody” than it

permits arrests on “ suspicion” or arrests “ for investiga

tion” . Henry v. United States, supra; ef. Mr. Justice Doug

las, “Vagrancy and Arrest on Suspicion” , 70 Yale Law J.,

1, 12-13. The sum of the matter is that if Shuttlesworth

did interfere with Chief Moore, it was while the latter was

making an illegal arrest and not while he was performing a

legal duty.

But Shuttlesworth’s mere act of asking the Chief what

was happening did not “ interfere” with the arrests or

“ prevent or hinder” them. The Chief had already told the

assembled group that they were under arrest and none re

sisted in any way. Nor can Shuttlesworth’s failure to in

stantly obey the chief’s command “ to go—to get out of my

way” and “ to leave the bus station” constitute an unlawful

interference with the Chief. This did not in fact prevent

or hinder the arrests, but in any event Shuttlesworth had

no duty to “ obey the command of an officer if the command

itself is violative of the Constitution” (Wright v. Georgia,

373 U. S. 284), and Shuttlesworth had a plain right to be

in the bus station, as well as to inquire as to the reason

for the arrest of his companions.

It is also apparent that petitioner never assaulted Chief

Moore or anyone else, at least as assault has been defined

17

in prior Alabama decisions and as it was defined by the

Court of Appeals in this case.

Neither the Birmingham City Code (§825), nor the Ala

bama Code (Tit. 14, §33) contain any definition of the

crime “ assault” ; the court below made reference to the

common law definition of the crime without elaboration or

citation (R. 60). But the Alabama courts have many times

set out their common law definition of assault in language

which clearly excludes petitioner’s conduct. They have de

fined assault as “any attempt or offer, with force or vio

lence, to do a corporal hurt to another, whether from malice

or wantonness, with such circumstances as denote, at the

time, an intention to do it, coupled with a present ability

to carry such intention into effect.” Tarver v. State, 43

Ala. 354, 356 (1869). To the same effect see Flournoy v.

State, 270 Ala. 448, 451, 120 So. 2d 124 (1960); Taylor

v. State, 27 Ala. App. 538, 175 So. 698 (1937): Burton v.

State, 8 Ala. App. 295, 62 So. 394 (1913); Naler v. State,

25 Ala. App. 486, 148 So. 880 (1933). There was simply

no evidence at all that Shuttlesworth made any “ attempt

or offer” to “ do a corporal hurt” to Chief Moore, and there

is not a hint of “ force or violence” on his part.

It is mystifying to ponder how the Court of Appeals

could have thought petitioner guilty of assaulting Chief

Moore without finding him guilty of interfering with him.

In any event, the Court of Appeals found an assault be

cause it said that petitioner “ blocked the chief’s path using

words from which the intent to do so fin rudeness or in

anger’ could probably and rationally be inferred” . Apart

from the fact that this was a new and unique statement of

the Alabama law of assault, and that none of the cases

cited by the court below remotely resemble what occurred

here,4 there was simply no evidence that petitioner either

4 Among the cases cited by the court below were Patterson v.

Sylacauga, 40 Ala. App. 239, 111 So. 2d 25 (1959) where the

18

“ blocked the chief’s path” or used any words “ in rudeness

or in anger”. There was no evidence that the Chief was

attempting to walk anywhere, and none that petitioner

“ blocked his path” or barred his way. At most petitioner

moved in front of the chief to ask him a question while

the chief was standing and talking with the group. There

was nothing to indicate that petitioner’s language was rude

or angry in tone or in content; indeed, all the evidence is

to the contrary. There is nothing unusual, and certainly no

assault, in standing near a person while talking to him,

which is all that the evidence shows Shuttlesworth did.

It is a “ violation of due process to convict and punish a

man without evidence of his guilt” . Thompson v. Louis

ville, 362 U. S. 199, 206. Inquiring of a police officer as to

what is happening to one’s companions when they are

ordered arrested in “ protective custody” , and refusing to

leave a bus station where one has a right to be as a paying

passenger, is neither an interference with an officer under

Birmingham Code §856 nor an assault punishable under

city code §825. The conviction should be reversed and the

petitioner discharged.

defendant, among other things, advanced on an officer with a

butcher knife and subsequently knocked him across a room; Ken

nedy v. State, 39 Ala. App. 676, 107 So. 2d 913 (1958) where the

defendant fought with the sheriff until two deputies came to his

assistance and subdued him; and Andersen v. United States, 132

A. 2d 155 (D. C. Mun. Ct.) aff’d 253 F. 2d 335 (D. C. Cir. 1957)

where the defendant pushed a policeman.

19

II.

The Law Under Which Petitioner Was Convicted Is

Unconstitutionally Vague and Fails to Warn That Peti

tioner’s Conduct Is Made Criminal.

The factors which make it apparent that there was no

evidence to support the conviction under §856 (and/or

§825) may also enable it to be perceived as constituting a

conviction based upon a law (or laws) which failed to give

fair warning. Indeed Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199,

206; rested in part upon Lametta v. Netv Jersey, 306 U. S.

451, a leading case articulating the vice of vague criminal

laws. Petitioner had a perfect right, founded on the Four

teenth Amendment, to be present and to await his bus in

the public bus terminal and a similar right to inquire as to

the basis for the unlawful arrest of his companions. As

this Court said in Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284:

“ & generally worded statute which is construed to

punish conduct which cannot constitutionally be pun

ished is unconstitutionally vague to the extent that it

fails to give adequate warning of the boundary between

the constitutionally permissible and constitutionally im

permissible applications of the statute. Cf. Winters v.

New York, 333 U. S. 507; Stromberg v. California, 283

IT. S. 359; see also Cole v. Arkansas, 333 IT. S. 196.”

There is nothing in §856 which gives warning that one

can be punished for refusing to obey an officer’s unjustified

command to leave a public bus terminal, or punished for a

mere peaceful inquiry as to the reason for an officer’s arrest

of one’s companions, and certainly not where the officer’s

contemporaneous statement of the basis for the arrest—

e.g. “ protective custody”—plainly reveals it to be an un

lawful arrest. The assault ordinance equally fails to warn

2 0

that this type of peaceful conduct is punishable, there being

nothing in the text of the ordinance or in the common law

definition of assault often repeated by the Alabama courts

from which one could so infer. It would require extraordi

nary prescience to know that a conversation such as peti

tioner’s conversation with Chief Moore is criminally pun

ishable. Convictions under criminal laws which give no

adequate notice that the conduct charged is proscribed vio

late the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Lametta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451; Connally v. General

Construction Co., 269 U. S. 385; United States v. L. Cohen

Grocery Co., 255 IT. S. 81; Edwards v. South Carolina, 372

U. S. 229.

III.

Petitioner’s Conviction Was Affirmed Under a Crimi

nal Statute, the Violation of Which Had Not Been

Charged, Contrary to the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

This Court’s holding in Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S. 196,

compels reversal of this conviction. The complaint under

which petitioner was charged, tried and convicted alleged

that he “ did knowingly and wilfully interfere with, burden

or prevent a police officer of the City of Birmingham; . . .

in the discharge of his legal duty,” “ in violation of Section

856” of the Birmingham City Code.

Petitioner argued to the Alabama Court of Appeals that

Ms conviction under §856 should be reversed because based

on no evidence. Without discussing this issue, the Court of

Appeals held that “ there was no error in his conviction

since he could have been clearly convicted of simple assault”

under §825 (R. 60).

21

"Whatever may be the meaning of the two city ordinances

involved here, it is clear that they proscribe separate and

distinct offenses, notwithstanding that they are both punish

able under the same code provision which deals with all

misdemeanors under the Birmingham Code. The problems

of proof and defense are obviously different. "Whatever the

relationship between the two laws, and the opinion below

leaves this in substantial confusion, it is clear that the

complaint never warned Shuttlesworth that he had to de

fend against a charge of assault or be at all concerned

with §825, and that the trial court never found him guilty

under §825.

This disposition of the appeal denies due process, for it

rests affirmance upon an assault ordinance under which

petitioner had never been charged, tried or convicted.

Indeed the word “ assault” was never mentioned at any

time during the trial. This disposition of the case disre

gards one of the most fundamental requirements of due

process—that a person be informed of the specific charge

made against him and be heard in defense thereof. An

affirmance of this kind in effect convicts the defendant

without a trial, as was noted in Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S.

196, unanimously reversing a conviction in similar circum

stances :

No principle of procedural due process is more

clearly established than that notice of the specific

charge, and a chance to be heard in a trial of the issues

raised by that charge, if desired, are among the con

stitutional rights of every accused in a criminal pro

ceeding in all courts, state or federal. Be Oliver, 333

U. 8. 257, 273, decided today and cases there cited. . . .

It is as much a violation of due process to send an

accused to prison following conviction of a charge on

22

which he was never tried as it would be to convict

him upon a charge that was never made. Dejonge v.

Oregon, 299 U. S. 353, 362. (333 U. S. at 201.)

Where, as here, a state provides an appellate procedure,

the proceedings in the appellate court are “ a part of the

process of law” under which a defendant is held in custody,

and must meet basic standards of fairness. Cole v. Arkan

sas, 333 U. S. at 201. This Court has not departed from

the simple and just proposition stated in Cole,5 and should

not do so now.

IV.

This Court Is Not Precluded From Reviewing the Judg

ment of the Court of Appeals of Alabama Where the

Supreme Court of Alabama Refused to Consider the

Merits Because the Certiorari Petition Filed There Was

Not on “ Transcript Paper.”

Discussion of the procedural issues appropriately may

begin with 28 U. S. C. §1257 which confers jurisdiction on

this Court to review certain judgments of “ the highest

court of a State in which a decision could be had.” One

seeking review here must have utilized all available pro

cedures for obtaining review of an inferior state court deci

sion in the state’s highest court, whether it is available as

of right6 or only in the discretion of the state courts.7 But

when a litigant reaches a “ dead end” short of the state’s

highest court (as here where there is no further review

5 The Cole ease has been cited with approval in Garner v. Loui

siana, 368 U. S. 157, 164; Paterno v. Lyons, 334 U. S. 314, 320;

and Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199, 206.

6 Southern Electric Co. v. Stoddard, 269 U. S. 186.

7 American B. Express Co. v. Levee, 263 U. S. 19.

23

as of right and efforts to secure further discretionary

review have failed), this Court may review the judgment

of the inferior court since it is the highest one “ in which

a decision could be had.” 8 These settled propositions

clearly point to the Court of Appeals of Alabama as the

highest court “ in which a decision could be had” in the

circumstances of this case. Decisions by that court were

reviewed here in Anderson v. A la ba m a 364 U. S. 877;

Gober v. Birmingham, 373 IT. S. 374; and Shuttlesworth v.

Birmingham, 373 U. S. 262.

The relevant Alabama law grants to the Court of Appeals

of Alabama “ final appellate jurisdiction . . . of all mis

demeanors, including the violation of town and city ordi

nances” (Title 13, Ala. Code §86). Petitioner could obtain

review of that court’s decision only by seeking a writ of

certiorari in the Supreme Court of Alabama, which is em

powered to issue “ such other remedial and original writs

as may be necessary to give it general superintendence and

control of inferior jurisdictions” (Ala. Const, of 1901, §140),

and which has provided for esercise of this power by con

sidering applications for writs of certiorari “ for the pur

pose of reviewing or revising any opinion or decision of

the court of appeals” (Ala. Supreme Court Rule 39, Appx.

to Tit. 7, Ala. Code 1958, pp. 1178-1179).9

8 American B. Express Co. v. Levee, supra.

9 Rule 39 provides:

CERTIORARI TO COURT OF APPEALS.

This court will not in term time, nor will the justices thereof

in vacation, receive or consider an application for the writ of

certiorari, or other remedial writ, or process, for the purpose of

reviewing or revising any opinion or decision of the court of

appeals, nor entertain, consider, or issue a writ of error, as au

thorized by section 98 of Title 13 of the Code, unless it appears

upon the face of the application therefor that application has

been made to said court of appeals for a rehearing of the point

or decision complained of, and that said application had been

24

When petitioner’s conviction was affirmed by the Court

of Appeals, and it denied rehearing, he sought certiorari

(clearly the proper remedy) in the Supreme Court by

filing a timely petition and an appropriate supporting

brief. This attempt to invoke the discretionary certiorari

jurisdiction of the Supreme Court was conformable to the

established rules and practice except in one respect, i.e.,

petitioner did not comply with Alabama Supreme Court

Rule 32 governing the type of paper to be used for such

petitions. Rule 32 stipulates inter alia that applications for

“ . . . the writ of habeas corpus, mandamus, or other writ

or process depending on motion of this court, . . . shall

decided adversely to the movant, and the application to this court

must be filed with the clerk of this court within fifteen days after

the action of said court of appeals upon the said application for

rehearing. The application for any such writ must be accom

panied by a brief pointing out and arguing the point or decision

sought to be revised or corrected. If the court, upon preliminary

consideration, concludes that there is a probability of merit in

the petition and that the writ should issue, it shall be so ordered,

of which due notice shall be given by the clerk to the parties

or their counsel, and the case shall stand for submission, as herein

provided, on briefs and likewise oral argument if so desired. If

oral argument is desired by petitioner, statement to that effect

shall be filed with the clerk by petitioner within ten days after

service on petitioner of the notice of issuance of the writ. If oral

argument is desired by respondent, then he or his counsel shall,

by endorsement on the last page of his brief, so state his desire.

If neither party shall thus indicate a desire for oral argument,

the clerk of this court shall, when briefs from all parties have

been filed with him as herein provided, immediately submit the

case in term time upon the transcript and such briefs. If either

party shall have made known a desire for oral argument, the

clerk of this court shall endorse that fact on the proper docket

and set the case down for oral hearing not less than ten days

after notifying the parties, or their attorneys of record, in writing

of such setting. Cases so set for oral argument shall be heard on

the day set unless continued by the court for good cause shown.

Respondent’s brief shall be filed with the clerk of this court

within fifteen days after service on respondent of the notice of

the issuance of the writ, and if not filed within that time, or

within any extended time, the cause shall stand ready for sub

mission.

25

be presented on folio paper, of the pattern now required

by the rule for ordinary transcripts, so that the same may

be suitable for binding; and no application shall be heard

that is not so presented.” The paper mentioned is about

10% x 16 inches in size.10 Petitioner ran afoul of this rule

when his attorneys filed the petition for certiorari on ordi

nary legal cap paper (8% x 14 inches) and the court below

entered an order striking the petition for certiorari.11

It is submitted that this procedural lapse cannot deprive

this Court of jurisdiction for several reasons, stated here

summarily, and elaborated below. First, the Alabama Su

preme Court could have exercised its discretionary juris

diction and considered the merits of the petition notwith

standing the procedural flaw. Such a discretionary refusal

to consider a federal claim cannot prevent this Court from

exercising jurisdiction. Williams v. Georgia, 349 U. S. 375.

Second, assuming, arguendo, that the Alabama Supreme

Court was without discretion to review the petition not

on transcript paper, the rule so harshly works a forfeiture

by exalting form and ritual that it cannot, in view of the

opposing interests at stake, be regarded as a state ground

for decision adequate and substantial enough as to prevent

review here. Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313; Rogers v.

Alabama, 192 U. S. 226.

10 “Eule 21. Paper of Transcripts

“All transcripts of records must be on paper of uniform

size, according to the same furnished by the clerk of the

supreme court, with a blank margin, at the top, bottom, and

sides of each page, of an inch and a half, exactly conforming

to those marked on the sample.”

11 The record does not reveal the reason why paper other than

transcript paper was used. But it is relevant to consider the

extremely heavy volume of civil rights litigation handled by only

a very few lawyers in some states in understanding how this

could have occurred. See 1963 Report of the United States Com

mission on Civil Rights, 117-119.

26

Finally, even where a state Supreme Court’s refusal to

grant a discretionary review is based on an adequate state

ground, the federal questions necessarily decided by the

intermediate appellate court are properly reviewable in this

Court. Cf. Hammer stein v. Superior Court, 341 U. S. 491.

To consider the above points in detail, it is first sub

mitted that the Alabama Supreme Court did have dis

cretion to consider the merits of Shuttlesworth’s petition

despite the fact that it was not on transcript paper. As will

be demonstrated, the Alabama courts have considered the

merits of cases despite noncompliance with the transcript

paper rule (Rule 32) as well as other Supreme Court rules.

Rule 32 was adopted by the Court in 186612 and was first

applied to strike a certiorari petition in 1946.13 Earlier the

rule had been applied to mandamus petitions14 and since

1946 it has been applied on a number of occasions.15 But

in cases involving both mandamus and certiorari petitions

12 The rule appears at 38 Ala. 12 (January term 1866), and in

subsequent Codes and Supreme Court reports without amendment

except for its number.

13Peterson v. State, 248 Ala. 179, 27 So. 2d 30 (1946).

14 Aust v. Sumter Farm & Stock Co., 209 Ala. 669, 96 So. 2d 872

(1923) (mandamus denied because not on transcript paper). The

Aust case is the first such use of the rule. Earlier the court had

indicated that it would tolerate some “ informality” in requests

for mandamus, though it was not clear in what respect the requests

for mandamus did not conform to this rule. See Ex Parte Tower

Manufacturing Co., 103 Ala. 415, 15 So. 836 (1893), and Brady

v. Brady, 144 Ala. 414, 39 So. 237 (1905), both of which are

discussed in Ex Parte Jackson, 212 Ala. 496, 103 So. 558 (1925).

15 The Court has on occasion said such things as “ the require

ment of Supreme Court Rule 32 is mandatory” (Accardo v. State,

268 Ala. 293, 105 So. 2d 865 (1958)) and “we have no alternative

but to strike” the petition (Metropolitan Life Ins. Co. v. Korneghy,

260 Ala. 521, 71 So. 2d 301 (1954)). But in the many decisions

under the rule the Alabama courts have never expressly stated

that noncompliance deprived the court of jurisdiction, and the

force of the above quoted statements is weakened by the courts’

actual actions in the cases discussed in the text infra.

27

not tendered on transcript paper the Alabama courts have

demonstrated their power to consider the merits. The first

such case was Ex Parte Wood, 215 Ala. 280, 110 So. 409

(1926), involving a petition for mandamus to review a de

cree fixing alimony pendente lite. The petition was not filed

on transcript paper, but the court nevertheless delivered a

lengthy holding that petitioner had not sustained his burden

of proof, before adding that “ another reason” for denying

the petition was the transcript paper rule. Then in Houston

v. State, 265 Ala. 588, 93 So. 2d 439 (1957), the court

“ struck” 16 a nonconforming certiorari petition but only

after having acceded to a request to consider the merits.

The Court said:

Subsequent to submission, appellant became aware

that the petition was not on transcript paper and re

quested leave to remedy this defect. In view of this

request, we have considered the petition on its merits

and find no reason to reverse the judgment of the Court

of Appeals. The writ would have been denied had the

application not been stricken. (Emphasis supplied.)

While the action of the Court in Houston was not unam

biguous, and the court has rejected a subsequent attempt to

induce it to consider the merits of such cases,17 the one

16 And it will be noted that in the opinion below in this case,

and in many others, the Alabama Courts have said that such

petitions were “stricken.” But the significance of this terminology

is not apparent because the court has seemingly used the terms

“ denied” and “ dismissed” interchangeably with “stricken” in

transcript paper cases. See Ex Parte Wood, supra; Aust v. Sumter

Farm & Stock Co., supra (“ denied” ) ; Elks Lodge v. State, 264

Ala. 223, 86 So. 2d 396 (1956) ( “denied” ) ; Bates v. General Steel

Tank Co., 256 Ala. 466, 55 So. 2d 218 (1951) ( “dismissed” ) ;

Maddox v. City of Birmingham, 255 Ala. 440, 52 So. 2d 166

(1951) (same) ; Stovall v. State, 257 Ala. 116, 57 So. 2d 642

(1952) (same) ; Morgan Plan Co. v. Beverly, 255 Ala. 235, 51

So. 2d 179 (1951) (dismissed; denied).

17 See, e.g., Jemison v. State, 270 Ala. 589, 120 So. 2d 751 (1960).

28

clear thing about Houston is the court’s plain statement

that it did consider the merits of the petition. Even more

striking is the action of the Alabama Court of Appeals

(which is bound by the same Rule 32) in Ex Parte Nations,

154 So. 2d 762 (1963). Nations, a prisoner appearing pro se,

sought certiorari to review an unfavorable trial court rul

ing on his habeas corpus petition, and the Attorney General

moved to dismiss on several grounds including failure to

use transcript paper. However, the Court said that it was

“ not disposed to cut off a prisoner’s post-conviction reme

dies merely on the bald reference to the Rule” and went on

to “ dismiss” the petition and “ deny” the writ on the ground

that it sought to “ rehash” claims made in earlier habeas

corpus proceedings. The Court stated the purpose of Rule

32 was “ to leave well bound records” and added:

. . . The size of the paper has prescribed the size of

the record racks and the use of much space in the

Judicial Building. To change the system of record

keeping would entail a considerable expense. More

over, the use of noncomplying paper (unless promptly

filmed) gives no assurance against fading and rot.

While the Nations opinion made reference to the prob

lem of whether litigants have the means to secure tran

script paper, there was no statement that such paper was

not available to Nations or that he had even so contended.

It can only be inferred that the Court found it sufficient

that the state made no showing that the paper was avail

able to this particular prisoner.

In addition to these cases where the court has considered

the substance of a case before it notwithstanding that it

was not on transcript paper, it is worthwhile to consider

cases where the court has condoned infringement of its

other rules. In Mitchell v. Helms, 270 Ala. 8, 115 So. 2d

664 (1959), a litigant who wrote his assignments of error

29

on transcript paper but did not have them bound into the

record was subsequently allowed to “write the assignments

on the transcript” before submission of the case.18 The

Court has also been liberal in excusing non-compliance with

its rules prescribing the contents of briefs, thus further

demonstrating its discretionary power to excuse violations

of its own rules.19

This, then, is a case where the Court had power to con

sider the merits but declined to do so, and Williams v.

v. Georgia, 349 U. S. 375, should apply. In Williams, the

state courts had power to consider and grant an extraor

dinary motion for new trial but refused. This Court con

cluded that “ the discretionary decision to deny the motion

does not deprive this Court of jurisdiction to find that the

substantive issue is properly before us” (349 U. S. at 389).

Second, even if it be assumed, contrary to the demonstra

tion above, that the Alabama Supreme Court was without

discretion to review the petition, this harsh and ritualistic

rule cannot be regarded as such an adequate and substan

tial state ground for decision as to prevent review here.

Under Alabama practice the certiorari petition itself is

a relatively brief document setting out the claims and

18 Cf. Hunter v. L. & N. B.B. Co., 150 Ala. 594, 43 So. 802

(1907), permitting a litigant, on rehearing, to correct an error

in filing his assignments of error on separate sheets of paper. But

see contra: Pugh v. Hardyman, 151 Ala. 248, 44 So. 389 (1907);

Cates Lumber Co. v. Givens, 181 Ala. 670, 61 So. 30 (1913) ;

Patton v. Colbert County, 265 Ala. 682, 92 So. 2d 691 (1957).

See also, Wilson v. Howard, 266 Ala. 636, 98 So. 2d 425 (1957).

19 Wood v. Wood, 263 Ala. 384, 82 So. 2d 556 (1955); City of

Montgomery v. Mott, 266 Ala. 422, 96 So. 2d 766 (1957); Quinn

v. Hannon, 262 Ala. 630, 80 So. 2d 239 (1955) ; Schmale v. Bolte,

255 Ala. 115, 50 So. 2d 262 (1951) ; Simmons v. Cochran, 252

Ala. 461, 41 So. 2d 579 (1949) ; Edge v. Bice, 263 Ala. 273, 82

So. 2d 252 (1955).

30

points made and requesting relief;20 the brief which must

accompany the opinion elaborates the arguments.21 But

the brief itself need not be filed on transcript paper.22

Ordinary legal cap paper also will suffice for petitions for

rehearing, Redwine v. State, 36 Ala. App. 560, 61 So. 2d

715 (1952). The requirement as to the size of the paper

to be used in certiorari petitions is not relevant to the ulti

mate just adjudication of claims, as are numerous proce

dural requirements. It is unlike time limits which help

establish finality of decisions. It does not regulate the flow

of business in the courts, thereby affecting the just and

prompt disposition of other litigation. It does not serve

any interests of the opposing party. It is not like rules

which aid the court in properly understanding and dispos

ing of the merits of a case, as might be true with rules

governing the contents of briefs or assignments of errors

or even rules regulating the size of type or printing or

to insure legibility.23 While it is a rule, and should be

obeyed and not deliberately flaunted, it relates only to

record keeping and filing problems—to binding the record

and storing it in filing racks of a particular size. This is

not a consideration to be ignored and Alabama might per

haps treat it by means of cost type sanctions, or by re

quiring resubmission of documents on proper size paper,

or perhaps even by striking state law claims, but peti

tioner submits Alabama cannot foreclose this Court from

considering federal constitutional issues on the basis of

20 See, Jones, Alabama Practice and Forms, §§6392, 6393; Ala.

Supreme Court Rule 39.

21 Ala. Supreme Court Rule 39.

22 Ala. Supreme Court Rule 8 provides only that briefs be typed

or printed, clearly legible, and bear the name and address of

counsel.

23 Cf. Rosenberg- & Weinstein, Elements of Civil Procedure, pp.

2-3 (Foundation Press, 1962).

31

that determination. This Court may well determine that

its interest in protecting the constitutional rights of those

charged with crime and threatened with imprisonment

through flagrant infringement of the constitution weighs

more heavily than any obligation to defer to state proce

dural peculiarities bearing no relation to the decision mak

ing process. In Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313, the Court

rejected an argument that failure to comply with a state

requirement that a defensive pleading “ count off, one by

one, the several sections of the ordinance” was an adequate

state ground. The requirement was characterized as . “ an

arid ritual of meaningless form.” Similarly in Rogers v.

Alabama, 192 U. S. 226, this Court disregarded an asserted

nonfederal ground based on the prolixity of a pleading. In

Carter v. Texas, 177 U. S. 442, it refused to allow a defend

ant’s federal claim to be evaded on the ground that his bill

of exceptions did not list the witnesses he proposed to call

and their intended testimony.

The nonfederal ground put forward in this case has

even less substance than those in the Staub, Rogers, and

Carter cases where the state grounds, though procedural,

at least had a connection with the decision making process.

The state ground put forward by Alabama here relates to

a mechanical requirement totally unrelated to the rights of

other litigants, or to the effective functioning of the court,

or to the merits of the case, which no litigant would in

tentionally disobey, and the breach of which might readily

be cured if the state rule did not work a strict forfeiture.

Finally, in Hammerstein v. Superior Court, 341 U. S.

491, this Court held that it need not consider the force of

an expression by the California Supreme Court that its

denial of hearing from the judgment of a lower court was

based on an adequate state ground, where the federal

ground had been decided by the inferior court. The Court

32

said: “ We do not consider the force of that statement since

it is clear that the judgment properly before us is that

of the District Court of Appeal, which did decide the federal

question. . . . We have jurisdiction over that judgment.”

(341 U. S. at 492.) This was a holding that where an

inferior court was the highest court in which a case might

be heard as of right, and an attempt had been made to

secure discretionary review in the state’s highest court,

it did not matter that the latter court might have declined

review because it conceived that an adequate state ground

supported the judgment. Application of this principle

would permit this Court to review the judgment of the

Alabama Court of Appeals in the instant case. It should

be noted that this result is not at all affected by the outcome

of the Hammerstein case—the fact that this Court declined

to exercise its discretionary jurisdiction. That result ob

tained because of a circumstance not at all present here,

e.g., Hammerstein’s failure in a parallel but separate pro

ceeding to use the remedy which could have gained him a

review of the same issues as of right. Indeed, there is a

substantial qualitative difference between a procedural

lapse which pertains only to form like petitioner’s, and the

mistake made in cases where the wrong remedy was sought,

as in one aspect of Hammerstein, supra (mistaken use of

certiorari rather than appeal) and in McMaster v. Gould,

276 U. S. 284 (attempted appeal without leave of court).

Petitioner’s mistake did not work any impediment limiting

the Alabama Supreme Court’s practical opportunity to ex

ercise its discretionary jurisdiction, or deprive that Court

of its jurisdiction. He should not be held to have inad

vertently waived his right to review by this Court of the

plain errors of constitutional dimension upon which his

conviction and the Alabama Court of Appeals’ affirmance

of it rest.

33

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons it is respectfully submitted

that the judgment below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Peter A. H all

Orzell Billingsley, J r .

1630 Fourth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Petitioner

Of Counsel:

Michael Meltsner

George B. Smith

38