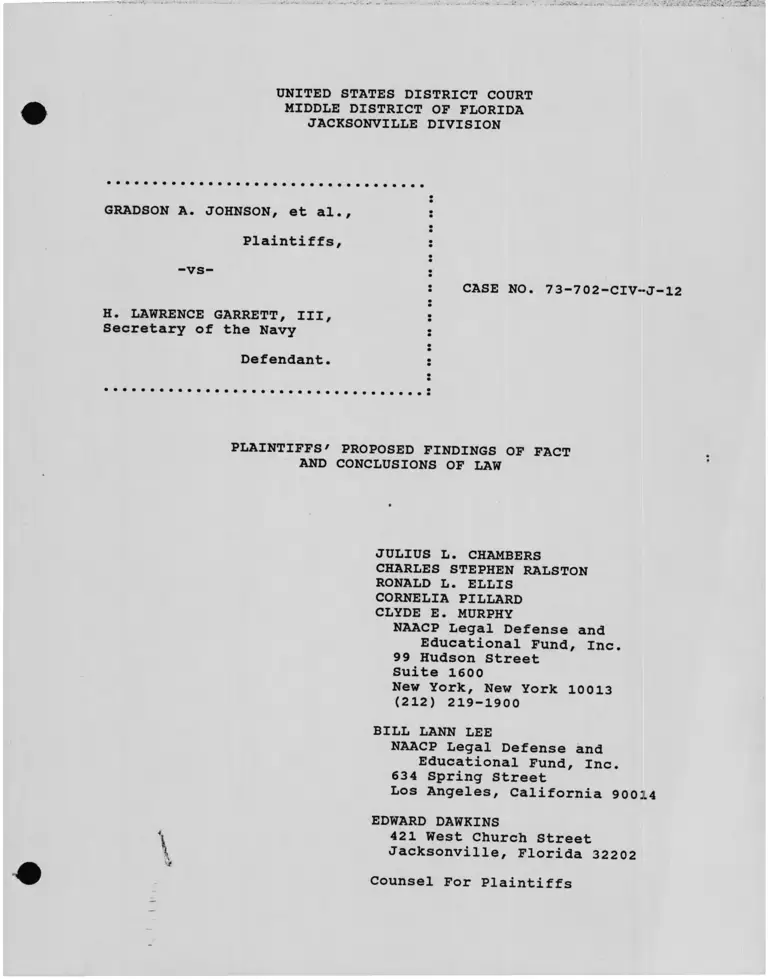

Johnson v. Garrett Plaintiffs' Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

Public Court Documents

November 6, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Johnson v. Garrett Plaintiffs' Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, 1989. 61a02d02-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/871b6198-17ea-4bed-ad10-79b0bd88826d/johnson-v-garrett-plaintiffs-proposed-findings-of-fact-and-conclusions-of-law. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

JACKSONVILLE DIVISION

GRADSON A. JOHNSON, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

-vs-

H. LAWRENCE GARRETT, III,

Secretary of the Navy

Defendant.

CASE NO. 7 3-702-CIV-J-12

PLAINTIFFS' PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT

AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON RONALD L. ELLIS

CORNELIA PILLARD CLYDE E. MURPHY

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.99 Hudson Street Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013 (212) 219-1900

BILL LANN LEE

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.634 Spring Street

Los Angeles, California 90014

EDWARD DAWKINS

421 West Church Street

Jacksonville, Florida 32202

Counsel For Plaintiffs

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

PART I ..................................................... 1

INTRODUCTION ............................................... !

Overview ............................................. i

The Disparate Treatment Case ........................ 3Legal Principles................................. 3

Evidence ......................................... 6

The Disparate Impact Case .......................... 7

Legal Principles................................. 7Evidence ......................................... 9

HISTORY OF PROCEEDINGS ..................................... 14

FINDINGS OF FACT ........................ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 19

PATTERN AND PRACTICE OF DISPARATE TREATMENT .............. 19

THE FUNCTION AND ORGANIZATION OF N A R F .................... 19

THE FUNCTION OF N A R F ...................... ! ! ! . * . * ! 19

THE ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE OF NARF 21NARF'S JOB CLASSIFICATION S Y S T E M .............. * * * 23

ANECDOTAL AND DOCUMENTARY PROOF OF DISPARATE TREATMENT . 29

THE SELECTION PROCESS.......................... ! ! ! 2 9

1973 CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION REPORT ANDEEO AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PLANS .................. 41

EEO DOCUMENTS .......................... ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 45

MANAGERIAL HOSTILITY TO PROMOTION OF BLACK EMPLOYEES* ! 47

DENYING BLACK EMPLOYEES INFORMATION ABOUT THE SELECTIONP R O C E S S ......................................... 53

DENYING BLACK EMPLOYEES DETAILS........... * ! ! . * ! ! ' 55DENYING BLACK EMPLOYEES TRAINING 62

DENYING BLACK EMPLOYEES A FAIR OPPORTUNITY FOR POSITIVE

PERFORMANCE EVALUATIONS, SUPERVISORY APPRAISALS AND AWARDS....................................... 64

NARF'S PROMOTION PROCEDURES PERMITTED MANAGEMENT * TO

SUBJECTIVELY EVALUATE RATING CRITERIA AND TOENGAGE IN SUBJECTIVE DECISION MAKING ............ 68

Qualifications Not Determinative For WhiteEmployees................................... 73

Subjective Decision Making By The Rating Panels . 75

i

Cancellation Of Certificates .................... 79

THE PATTERN OF DISCRIMINATION WAS PERVASIVE FOR BLACKSUPERVISORS, ARTISANS, AND WORKERS .............. 80

FAILURE TO ADHERE TO MERIT PRINCIPLES AND REGULATIONS . 98

FAILURE TO INCLUDE BLACKS ON RATING PANELS .......... 100

FAILURE TO IMPLEMENT AN EFFECTIVE UPWARD MOBILITY

P R O G R A M .........................................103

FAILURE TO POST ANNOUNCEMENTS........................ 10 6

FAILURE TO CORRECT SUPERVISORY APPRAISAL FORM ........ 107FAILURE TO REVISE JOB QUALIFICATIONS ................ 107

FAILURE TO RESTRUCTURE JOBS TO ELIMINATE DEAD ENDPOSITIONS.......................................108

FAILURE TO CURB THE HARASSMENT OF BLACK EMPLOYEES . . . 109PRODUCTION CONTROL ................................... 113

STATISTICAL PROOF OF DISPARATE TREATMENT .................. 116

SUMMARY OF STATISTICAL PRESENTATION .................. 116

STATISTICAL METHODS EMPLOYED ........................ 120WORK FORCE PROFILES...................................... .

THE PLAINTIFFS' DATA B A S E ...................... ! ! ! 12 4PLAINTIFFS' STATISTICAL RESULTS................ .. ’ 127

MOVEMENT BETWEEN GS AND FWS PAY SYSTEMS.............. 13 0

RELATIVE IMPORTANCE OF COMPETITIVE AND NONCOMPETITIVEM O V E S ..............................................

THE COMPETITIVE SELECTION PROCESS............ * * * i32

DEFENDANT'S TEAM OF EXPERT WITNESSES.............. j 13 4THE DEFENDANT'S DATA B A S E S ...................... ’ ’ 134

DEFENDANT'S COMPETITIVE PLACEMENT ANALYSIS .......... 138APPLICANT RATES FOR BLACK EMPLOYEES ................ [ 146DEFENDANT'S MOVEMENT ANALYSIS .................. j 147

DEFENDANT'S NONCOMPETITIVE PLACEMENT ANALYSIS ........ 148CAREER LADDERS ....................................... 149

APPRENTICE P R O G R A M .................. ! ! ! . * . * ! ! ! 151

DEFENDANT'S ANALYSIS OF TEMPORARY PROMOTIONS ........ 152

DEFENDANT'S ANALYSIS OF THE UPWARD MOBILITY PROGRAM . . 152DEFENDANT'S PROMOTION ANALYSIS ...................... I53

FAILURE TO VALIDATE SELECTION PROCEDURES ............ 155

DEFENDANT'S ARGUMENT THAT BLACK EMPLOYEES LACKED PRIOREXPERIENCE..........................................

DEFENDANT'S ARGUMENT THAT FEW EMPLOYEES PROGRESSED " INFWS J O B S ............................................

PLAINTIFFS' REBUTTAL MOVEMENT ANALYSIS 165

DEFENDANT'S SURREBUTTAL ARGUMENT THAT QUALIFIED PEOPLEARE MORE LIKELY TO BE PLACED.................... 17 0

DEFENDANT'S SECOND SURREBUTTAL ARGUMENT THAT QUALIFIEDPEOPLE GET P L A C E D .............................. ...

CLAIMS OF DISPARATE IMPACT ................................. 173

INDIVIDUAL DISPARATE TREATMENT .......................... 173

GRADSON JOHNSON........................ 17 4

MARCUS GARVEY ELLISON................ . * ! ! ! ! . . * . ’ 177

ii

WILLIE ROBINSON ....................................... 182S.K. S A N D E R S ............................................

ANDREW NORRIS ......................................... 191

WILLIE MORAN ......................................... 195

PART I I I ................................................... ...

CONCLUSIONS OF L A W ..................................... | I97

JURISDICTION ............................................... 197

PATTERN AND PRACTICE OF DISPARATE TREATMENT ............... 197

CLASSWIDE CLAIMS OF DISPARATE IMPACT ...................... 203

INDIVIDUAL DISPARATE TREATMENT .......................... 219NAMED PLAINTIFFS.............................. ’ ’ * 223Gradson Johnson.................................* * [ 225Marcus Ellison ....................................... 226

Willie Robinson.....................................[ 229

Andrew Norris.................................. * [ 230

S. K. SANDERS............................ ! ! ! ! ! . ’ ! 231

PART I V ................................................... ...

FURTHER PROCEEDINGS ....................................... 233

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ............

PART I

INTRODUCTION

A. Overview

The underlying premise of plaintiffs7 case is that black

NARF employees are denied a fair opportunity to obtain promotion

and thereby reach their full potential in the work force. This

fundamental denial is accomplished through a promotion/selection

system in which discrimination is a "standard operating

procedure", International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324, 336 (1977) ("Teamsters"). NARF7 s system

relies on a series of discretionary and subjective judgments

which evidences a purposeful practice of disparate treatment of

blacks, and has an unjustified disparate impact on black

employees.

The defendant's subjective decision making system, is a

multistep promotion process that is primarily distinguished by

the numerous opportunities that it offers the virtually all-white

supervisory force to make subjective judgments that directly and

adversely impact the promotional opportunities of black

employees. Indeed, the system requires supervisors to make wide

ranging subjective rating, appraisal, training and assignment

decisions, as well as such fundamental decisions as whether the

position will be filled by outside hire or internal selection,

and if filled by internal selection, whether the position will be

filled by competitive or noncompetitive means.

1

Blacks as a class of employees, regardless of their pay plan

and grade, are systematically victimized by this selection

system. As a result of the operation of this system, class

members receive fewer career-enhancing details and training;

poorer supervisory ratings; lower ratings from the rating panels;

and therefore are selected for promotion less often than

similarly situated white employees. Specifically, plaintiffs

contend that a comparison of similarly situated black and white

employees demonstrates that blacks are less likely than whites to

be promoted; and, that this discrepancy has continued throughout

the period relevant to this lawsuit, notwithstanding the

knowledge of the defendant.

The underlying premise of NARF's defense is that the

complexity of the jobs involved somehow justifies employment

procedures that are discriminatory. Congress, in enacting Title

VII and amending it to include employees of the federal

government, has rejected this premise. Plaintiffs do not contend

that unqualified blacks must be promoted in proportion to their

appearance in the work force. Title VII commands that blacks

must not be presumed less qualified then whites and that the

failure of blacks, who are similarly situated to whites, to

achieve a reasonable share of employment opportunity within the

defendant's work force is evidence that discrimination is

present. Here, the evidence establishes a violation of Title

VII by NARF under both the Disparate Treatment and Disparate

Impact theories of discrimination.

2

B. The Disparate Treatment Case

Plaintiffs' ability to attack this system is unaffected by

the Supreme Court's decision in Wards Cove Packing Co. Inc.. v.

Atonio. 490 U.S. --- , 104 L. Ed 2d 733, 109 S. Ct. (1989)

("Atonio"). In the first instance, Atonio only addresses the

issue of the parties respective burdens in the context of a

Disparate Impact case. Here, plaintiffs have challenged the

defendant's promotion system under both the Disparate Treatment

and Disparate Impact theories of discrimination. Second, Atonio

confirms, rather than inhibits, the ability of plaintiffs to

attack a "subjective decision making" system id. at 751, as a

single practice under the disparate impact theory. Additionally,

in this case, the statistical evidence of both parties

establishes that the NARF's use of the merit selection process is

a discrete promotion practice, within a system that includes both

competitive and noncompetitive means of advancement, and that

this practice accounts for the disparate impact suffered by black

employees seeking advancement. 1

1. Legal Principles

The decision of the United States Supreme Court in Atonio.

was concerned exclusively with the Disparate Impact analysis, and

did not explicitly or implicitly affect the judicial framework

for determining Disparate Treatment specified in Teamsters and

other cases. In Teamsters. 431 U.S. at 335-36 n. 15, the

Supreme Court stated:

3

" 'Disparate treatment . . . is the most easily

understood type of discrimination. The employer simply

treats some people less favorably than others because

of their race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

Proof of discriminatory motive is critical, although it

can in some situations be inferred from the mere fact

of differences in treatment. [Citation omitted]

Undoubtedly disparate treatment was the most obvious

evil Congress had in mind when it enacted Title VII. "

Statistics can establish discriminatory motive by

demonstrating a consistently adhered-to practice, Sweeney v.

Board of Trustees, Keene State College. 569 F.2d 169, 177-79 (1st

Cir. 1977), and may alone justify the an inference of a

discriminatory motive and thus establish a prima facie disparate

treatment violation. Hazelwood School District v. United States.

433 U.S. 299, 307-308 (1977); Davis v. Califano. 613 F.2d 957,

962-65 (D.C. Cir-. 1979) ; Seqar v. Civiletti . 25 FEP Cases 1453

(D.D.C. 1981).

The courts have relied upon a variety of evidence to

buttress class action claims of improper motive or discriminatory

intent, including historical, individual and circumstantial

evidence and perpetuation of prior discrimination.1 In

particular, the use of subjective criteria may create or

strengthen an inference of discrimination since the rejection of

PacTe v-_B-S;_Indus., Inc.. 726 F.2d 1038, 1046 n. 91(5th Cir. 1984) (historical, individual and circumstantial

evidence); Payne v. Travenol Laboratories, Inc.. 673 F.2d 798,

®17. (.5th cir-), reh'q denied. 683 F.2d 417 (5th Cir.), cert denied, 459 U.S. 1038 (1982) (testimony of specific instances of

discrimination against plaintiff class members) ; Pavne v.

Travenol— Laboratories,__Inc. . supra. Van Aken v. Young. 541

F.Supp. 448, 457 (E.D. Mich. 1982), aff'd. 750 F.2d 43 (6th Cir.

1984) (the undisputed existence of discrimination priofr to the enactment of the equal opportunity law) . j.

4

an otherwise qualified individual on the basis of subjective

considerations provides an opportunity for unlawful

discrimination and entitles plaintiff to an inference of

discrimination. Burrus v. United Tel. Co.. 683 F.2d 339 (10th

Cir.) cert denied. 459 U.S. 1071 (1982); O'Brien v. Skv Chefs

Inc^, 670 F. 2d 864 (9th Cir. 1982) . Reliance on procedures

involving the use of vague and subjective criteria can serve to

corroborate statistical evidence of discrimination. United

States v. Hazelwood School District. 534 F.2d 805, 813 (8th Cir.

1976), rev'd on other grounds. 433 U.S. 299 (1977)

In a class wide disparate treatment case, the allegedly

discriminatory conduct is not a single, isolated decision

affecting only one. individual, but rather a broadly applicable

practice of intentional discrimination affecting the class as a

whole. In such a case, plaintiffs establish a prima facie case

by introducing statistical and other evidence of a "standard

operating procedure" of class wide disparate treatment,

Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 336; see also Page v. U.S. Indus.. Tnc.,

726 F.2d 1038, 1046 n.91 (5th Cir. 1984), or by proving the

class wide application of a facially discriminatory policy.

T^ans— World Airlines v. Thurston. 469 U.S. Ill, 121 (1985).

Proof of a prima facie case shifts the burden of persuasion, not

the burden of production, to the employer. See Teamsters. 431

U.S. at 360; Thurston, 469 U.S. at 122-25. Once plaintiff has

borne his burden of proof to establish a violation of Title VII,

defendant then has the burden of establishing what is, in

5

essence, an affirmative defense. The decision of the Supreme

Court in Atonio, did not alter these respective burdens.

Once an employer has set forth its proffered reasons for its

actions, the plaintiff may prove pretext either directly, by

persuading the court that a discriminatory motive more likely

motivated the employer, or indirectly, by showing that the

employer's proffered explanation is unworthy of credence. Bell

v. Birmingham Linen Serv.. 715 F.2d 1552, 1557 (11th Cir. 1983),

cert denied, 467 U.S. 1204 (1984); Fields v. Bolaer. 723 F.2d

1216, 1219 (6th Cir. 1984); Tate v. Weyerhaeuser Co. . 723 F.2d

598, 603 (8th Cir. 1983), cert denied. 469 U.S. 847 (1984);

Thorne v . City of El Sequndo. 726 F.2d 459, 465 (9th Cir. 1983),

cert denied, 469 U.S. 979 (1984); Martinez v. El Paso County.

710 F.2d 1102, 1104 (5th cir. 1983).

2. Evidence

The defendant has a particularly tough burden in this case

because its affirmative action plans so clearly commit NARF to

remedying the very discriminatory practices challenged in this

lawsuit. Unfortunately, NARF did not do so. The plans, in fact,

demonstrate the pretextual nature of any justification belatedly

presented. Management was presented with feasible remedial

options but refused to implement them in any meaningful fashion

during the liability period.

Plaintiffs established discrimination under the Disparate

6

Treatment theory, by the introduction of documentary, anecdotal

and statistical proof of discrimination.

The evidence presented by plaintiffs unequivocally

established that the policies and practices of the defendant

were applied differently to blacks than to whites, and that the

defendant was aware of this effect but failed to take remedial

action. The Civil Service Commission report established in 1973

the problems regarding details, training, and promotion boards,

and every narrative Affirmative Action plan has reiterated these

problems and suggested alternatives such as rotating details,

adding blacks to promotion boards and more training details for

blacks, however these recommendations have yet to be implemented.

This evidence was collaborated by testimony from class

members, and in many instances, witnesses for the defendant, who

confirmed that black employees were indeed affected by problems

first identified in 1973. Additionally, the testimony of NARF's

Deputy EEO Officers, covering a combined period from 1972 to 1977

and 1980 to 1988, confirmed that management at NARF was

repeatedly made aware of the problems that existed and the

remedial action required, but that NARF was consistent in its

refusal to address these problems.

C. The Disparate Impact Case

1. Legal Principles

The Supreme Court has uniformly held, that once the

plaintiff establishes a prima facie disparate impact case under

7

§703 (a) (2), the burden shifts to the employer to show that the

challenged practice is justified. See. e.g.. Griggs v. Duke

Power Co.. 401 U.S. 424, 431,432 (1971) ("The touchstone is

business necessity"; "Congress has placed on the employer the

burden of showing that any given requirement must have a manifest

relationship to the employment in question").

The Supreme Court's Atonio decision does not eviscerate the

Disparate Impact Theory. Rather, the Court held that the

language of its prior cases was misinterpreted as requiring the

employer to bear the burden of persuasion rather than one of

production. The Court emphasized that the employer's burden was

nevertheless substantial: it must produce evidence that "a

challenged practice serves, in a significant wav, the legitimate

employment goals of the employer", and that "[a] mere

insubstantial justification . ✓ . will not suffice". 104 L.Ed.2d

at 752.

Though we have phrased the query differently in

cases, it is generally well-established that

at the justification stage of such a disparate impact

case,_ the dispositive issue is whether a challenged

practice serves, in a significant way, the legitimate

employment goals of the employer. Watson. 101 L.Ed 2d

827' N.Y. Transit Authority v. Beazer. 440 U.S. at 587,

^•31; Griggs, 401 U.S. at 432. The touchstone of this

inquiry is a reasoned reviewed of the employer's

justification for his use of the challenged practice.

A mere insubstantial justification in this regard will

not suffice, because such a low standard of review

would permit discrimination to be practiced through the

use ° ̂ spurious, seemingly neutral employment practices.

104 L.Ed 2d at 752-53.

8

The Supreme Court's decision in Atonio does not alter the

conclusion that a subjective decision making system can be

challenged under the Disparate Impact theory. Indeed Atonio is

clear that a subjective selection system is a practice, that can

be challenged under the Disparate Impact approach Atonio. 104

L.Ed.2d at 751 ("use of 'subjective decision making'" is a

practice that can be challenged along with objective practices);

Watson v. Fort Worth Bank & Trust Co.. 487 U.S. ____, 101 L.Ed.2d

827, 848, 108 S. Ct. 2777, ____ (1988) ("Watson") (application of

Disparate Impact analysis "to a subjective or discretionary

promotion system").

NARF, therefore, is wrong in stating that the various

elements of its subjective decision making system must be

separately quantified.

The plaintiffs in a case such as this are not required

to^ exhaust every possible source of evidence, if the

evidence actually presented on its face conspicuously

demonstrates a job requirement's grossly discriminatory

impact. If the employer discerns fallacies or

deficiencies in the data offered by the plaintiff, he

is free to adduce countervailing evidence of his own.

Watson, 101 L.Ed 2d at 846; Atonio. 104 L.Ed 2d at 747 n. 6.

2. Evidence

In this case plaintiffs have proved that "subjective

decision making" is the practice which causes the disparate

impact on blacks seeking promotion. Moreover, the testimony and

documentary evidence - particularly the 1973 Civil Service

Commission report, the subsequent Affirmative Action Plans, and

9

the testimony of the defendant's Deputy EEO Officers

demonstrate via admissions, that supervisory discretion in

performance appraisals, evaluations, selections for details and

temporary promotions and rating panel evaluations have a

disparate impact on black employees' promotional opportunity.

Moreover, plaintiffs' statistics show by pay plan, grade, and

occupation series that blacks are adversely affected by this

practice.

Even if the Court were to hold that plaintiffs were

required to specify a discrete practice within the defendant's

subjective decision making system which accounts for the

disparate impact on black employees, the statistical evidence

demonstrates that the Merit Promotion Process is that discrete

practice. As repeatedly demonstrated by witnesses for both

and defendant, the Merit Promotion Process, although

only one of several means of attaining advancement within NARF,

accounts for the disparate impact suffered by black employees.

The documentary, anecdotal and statistical evidence

presented by plaintiffs to establish Disparate Treatment, is

relevant and sufficient to establish plaintiffs' claim of

Disparate Impact. The evidence establishes that the defendant's

practice of operating a subjective decision making system had a

disparate impact on black employees.

The defendant here failed to come forward at trial with

admissible evidence to justify the use of its subjective decision

making system. Instead the defendant relied on the efforts of

10

its statistical experts to establish that its promotion system

did not have a discriminatory impact on black employees. No

evidence was presented that the system was valid. The

defendant's expert, Mr. Ruch, admitted that he had done no

validation study and had not examined the manner in which the

Navy's promotion procedures were implemented at the NARF.

Similarly, defendant's personnel expert, Mrs. Kay Marti, admitted

that no validation study had been done. Since the defendant was

unable to offer any evidence that this system has was valid or

that alternatives recommended to the defendant but untried were

inappropriate to address this disparate impact, the evidence,

viewed in its totality, demonstrates a violation of Title VII

under the Disparate Impact theory.

The evidence in this case — statistical, documentary and

anecdotal - establishes a classwide violation of Title VII under

both the Disparate Treatment and Disparate Impact theories of

^̂ -®c--̂’i®iriation; that the named plaintiffs have suffered as a

result of this discrimination; and that the named plaintiffs and

other members of the class are entitled to have their individual

claims of discrimination evaluated under the standard established

by the Supreme Court in Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co. 424

U.S. 747 (1976) ("Franks") and Teamsters in subsequent

proceedings.

11

Plaintiffs respectfully submit their Proposed Findings of

Fact and Conclusions of Law for consideration by this Court in

rendering its decision. The Proposed Findings outline the

history and scope of this class action, which was brought on

behalf of black employees challenging the promotion policies of

the Jacksonville, Florida, Naval Air Rework Facility (NARF), H.

Lawrence Garrett, III, Secretary of the Navy. The Proposed

Findings describe the organization and function of the NARF, the

nature of its work force, and the method of advancement within

the Facility. In addition, these Findings recount elements of

the past history of discrimination at NARF and describe the

background and component parts of the promotion system at issue

, in this action. The statistical evidence presented by the

parties is discussed, along with an explanation of the manner in

which the promotion system operated in fact; the problems that

plagued the system; and, the defendant's failure to show that the

selection system was valid. The Findings also set forth numerous

examples of the defendant's continued awareness that racial

discrimination existed at NARF, and the Facility's failure to

address, redress or eliminate the causes or effects of its

discriminatory practices. Finally, the historical information,

statistical evidence, and analyses of the selection procedures

are buttressed by Findings on the class member testimony.

Plaintiffs also submit herein a set of Conclusions of Law

establishing the legal framework within which the facts of this

case should be reviewed.

12

Throughout this document, the following record citations are

used:

"P. Exh. No." designates Plaintiffs' Exhibits;

"D. Exh. No." designates Defendant's Exhibits;

"T.T." refers to Trial Transcript testimony:

"Depo" refers to Deposition testimony.

\

13

HISTORY OF PROCEEDINGS

1. This action was instituted when Plaintiff Andrew Norris,

filed an administrative Third Party group complaint on behalf of

a group called Concerned Minorities of NARF, on April 26, 1973,

which was refiled on June 4, 1973. The Third Party Complaint

made allegations of class wide discrimination, alleging that

qualified black employees were being systematically denied equal

employment opportunity at the facility by virtue of policies and

practices that had the intent and effect of limiting and

classifying black employees on the basis of their race. NARF

rejected the complaint on August 19, 1973! Complaint at 6;

Amendment To Complaint at 1-2; P. Exh. No. 267 at Vol III p. 84-

85.

2. On June 4, 1973, plaintiffs Andrew Norris, Gradson A.

Johnson, Marcus G. Ellison, Willie Robinson, and S.K. Sanders,

all filed individual administrative complaints alleging racially

discriminatory employment policies at NARF.2 Specifically, the

complaint of Mr. Norris, and the other named plaintiffs alleged

that the NARF engaged in racial discrimination against black

employees as a matter of custom, tradition, policy, pattern and

ky limiting and classifying blacks to deprive them of

Willie Moran, who is now deceased, also filed an administrative complaint. By Order dated April 20, 1983, this

Court substituted his widow, Mrs. Emma Moran, for Mr. Moran in the limited capacity of class member.

14

equal employment and promotional opportunities. Complaint at 6 ;

Amendment To Complaint at 2.

3. Following the rejection of their Third Party and Individual

Administrative Complaints by NARF, the plaintiffs timely filed

this lawsuit on September 13, 1973. Complaint.

4. By Order dated December 5, 1978, the Court denied NARF's

Second Motion for Summary Judgment as well as their Motion to

Dismiss. These motions challenged the Court's jurisdiction

based on the individual claims and administrative complaints.

The Court ruled that the charges were an adequate basis for the

lawsuit. The Court denied NARF's motion to reconsider on July

19, 1979.

5. On August 22, 1980, and again on September 14, 15, and 16,

1982, the Court heard plaintiffs' Motion for Class Certification.

In particular the Court considered the accuracy and reliability

statistical exhibits and data bases offered by

plaintiffs to establish the propriety of class certification. By

Order dated April 25, 1983, the Court certified this action as a

class action, and defined the class to include, "black employees

at NARF who are employed, or who were employed on or after March

24, 1972, at NARF". Order at 9. On February 23, 1987, the Court

ordered that:

[T]he class in this case is redefined to include all

black employees of NARF who are now employed or who

were employed on or after April 1, 1973 and who are or

were permanent employees eligible for promotion.

Order at 1-2.

15

6. By Order dated February 27, 1985, the Court ordered that

the trial of this matter would be "bifurcated into Stage One to

determine the question of liability and, if liability is found,

Stage Two to determine individual entitlement to relief for

members of the class." Order at 2.

7. By Order dated May 6, 1985, this Court upheld and/or

amodified sanctions imposed on plaintiffs by the Magistrate in

connection with delays in the development of plaintiffs'

computerized data bases and the statistical exhibits. Those

sanctions prohibited the introduction of evidence by plaintiffs

on a number of factual questions and required plaintiffs to

identify various statistical trial exhibits, and to make their

expert available for deposition. The requirements of those

sanctions having been met, this' Court concludes that the

defendant has been allowed sufficient access to discoverable

information, so as to allow NARF to properly prepare its case for

without suffering any prejudice, and consistent with the

aim of the sanctions.3 * 1

During the course of the trial the defendant objected on seven separate occasions to plaintiffs' evidence on the basis

of the sanctions imposed during pretrial discovery by the

Magistrate. Specifically, the defendant asserted that the

evidence being offered violated sanctions prohibiting evidence

(1) "challenging any of the specific eligibility standards as

being inconsistently applied", 1 T.T. at 65-66 (Clark), 6 T.T. at

69—77 (Shapiro); (2) showing that blacks were inadequately represented on any promotional board, 1 T.T. at 168-170 (Ware) 2

T.T. at 76-87 (Guy), 9 T.T. at 40-41 (Mack); (3) showing the

concentration of blacks caused by an employment classification

system in the production controllers division, that there were

placement levels for which blacks were otherwise qualified but

were not placed, and showing systematic exclusion of blacks from

specific departments and high level positions, 6 T.T. at 48-51,

16

61-63, 65-66 (Shapiro), 6 T.T. at 69-77 (Shapiro); and, (4) being

outside the time frame of the litigation, 3 T.T. at 162-163 (Bailey), 10 T.T. at 6-7 (Vanderhorst).

Plaintiffs responded by asserting as to (1) that the intent

of the sanctions was to prevent testimony that was aimed at

challenging specific eligibility requirements that had not been

identified to the defendant during pretrial discovery.

Plaintiffs further noted that they had "not challenged specific

eligibility standards", and that the thrust of their case

continued to be the pattern of subjective decision-making, not the identification of specific eligibility requirements; (2) that

the sanctions were derived from plaintiffs inability to provide,

in what the Magistrate considered a timely fashion, an

evaluation of the Pro-Op files, which would indicate which

particular promotion panels had an insufficient number of blacks,

and the number of blacks and whites on those panels. The

plaintiffs further responded that the sanction did not apply to

the testimony of individual witnesses, whose information was

unrelated to plaintiffs statistical evaluation of the Pro—Op

fil®s, and who at all times were available for deposition by the

defendant; (3) that the purpose of the P.Exh. No. 10X was not to

show concentration of blacks in the production controllers

position or in occupation series 1152, but for the purpose of

addressing the movement of black and white employees into and out

of 1152 and to show crossover between the FWS and GS pay categories; (4) that the testimony went to the question of the

witnesses qualifications, but was additionally relevant in that

the defendant's pre—Act history is relevant in support of a

showing of a pattern and practice of discrimination, and (5)

plaintiffs additionally responded to the objection to the

testimony of Dr. Shapiro at 6 T.T. at 69-77, (evaluation of the

Pro-Op^ files)^ arguing that his testimony made no reference to

specific eligibility standards, and was addressed instead to the

reason for plaintiffs' determination that an evaluation of the

pro-ops was not an appropriate means for determining the impact

or intent of the defendant's promotional system. Specifically

Dr. Shapiro testified that the various elements of the

defendant's selection system did not operate separately, and

therefore there was no way to do a statistical analysis of the

steps in the process since they were neither clearly defined or

separable steps. Consequently plaintiffs analyzed the data in

terms of the actual movement of employees that would capture all the different ways of moving within the system.

Each of the defendant's objections were overruled, at least insofar as the offered evidence did not conflict with the

sanctions. Additionally, as to the defendant's objections to

testimony regarding the racial makeup of rating panels, the Court

17

■ •U'l'vii »> —■ k +*+ —Xs ,<I>AW '---------- .O u ’.kAwCVw-i.t ■ ’_.: .-•

8. By Order dated February 9, 1988, discovery in this action

was closed as of April 7, 1989.

9. This cause was tried before the Court from May 22, through

July 14, 1989.

held,_ that the disputed testimony went to the question of

consciousness or intention of discrimination, and allowed the

testimony on this issue, reasoning that the sanction would not,

however, permit plaintiffs "to show that there were certain

boards on which the blacks were inadequately represented".

18

PART II

FINDINGS OF FACT

PATTERN AND PRACTICE OF DISPARATE TREATMENT

THE FUNCTION AND ORGANIZATION OF NARF

THE FUNCTION OF NARF

1. The Naval Air Rework Facility, NARF, is a depot level

maintenance facility of the Naval Shore Establishment. It is a

quasi-commercial activity with civilian personnel and naval

officer upper management. The mission of NARF is to provide

aviation maintenance, engineering, logistics, and support

services to the fleet. Joint Pretrial Stipulation at V-l.

2. There are six Naval Air Rework Facilities in the country,

including NARF Jacksonville. The Navy maintains a large fleet of

fixed-wing and rotary-wing aircraft, a percent of which is

continually in for rework and overhaul. id.

3. NARF is a large industrial complex. It covers 102 acres,

has about 41 buildings, and employed roughly 2450-3100 people at

any given time during the 1973-1982 time period. Stipulation at

V-2 .

4. NARF performs standard depot level maintenance functions

for aircraft, engines, aircraft components, and ground support

19

equipment. The aircraft and its engine(s) and components are

completely taken apart, cleaned, inspected, refurbished,

repaired, rebuilt, reassembled, inspected, and tested by NARF.

It manufactures parts when commercial sources are not available,

provides technical and professional services in support of rework

of specific aircraft, engines, and aircraft components, and

performs calibration of electronic instruments. Id.

5. The main function of NARF is the rework, repair, and

modification of aircraft engines, components (including flight

instruments, electronics, test equipment, mechanical and

hydraulic systems, metal surfaces, electrical systems, and

ordnance), and ground support equipment (including tow tractors,

aircraft power] units, hydraulic jacks, and work stands). A

number of different aircraft are reworked at NARF, including the

A-7 attack bomber and the P-3 patrol plane. Engines and

components reworked at NARF may be from aircraft being

simultaneously reworked, or may be inducted separately. Some of

the engines and components reworked at NARF are from aircraft

reworked elsewhere. Stipulation at V-ll-12.

6. The aircraft, engines, components, and ground support

equipment reworked at NARF are complex and varied, as are the

industrial processes performed. Stipulation at V-12.

7. The basic work flow through NARF can be categorized as

rework/repair, manufacturing, and calibration. All products

undergoing rework/repair require basically the same set of steps

to be performed: induction, initial examination and evaluation

20

(E&E); disassembly; follow-up E&E; repair; inspection;

reassembly; and test. Stipulation at V-10.

8 . The work performed at the NARF throughout the period from

1975 through the present was quite similar. The vast majority of

the required knowledges, skills and abilities have been the same

or substantially similar throughout this time period.

Stipulation at V-ll.

THE ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE OF NARF

9. NARF's Commanding Officer is held accountable for the

efficiency, effectiveness of performance, and economy of

operations. NARF is run by military personnel at a management

level above_ the department level. Reporting to the Commander

(and the Executive Officer) are the Production Officer, the

Management Services Officer and Comptroller, and the Quality

Assurance Officer. In addition, the Safety Director and the

Deputy Equal Employment Opportunity Officer report to the

Commander. Stipulation at V-6-7 .

10. Organizationally, departments are subdivided into

divisions. Divisions are subdivided into branches. Branches (in

the case of the Production Department) are subdivided into shops.

11. The NARF consists of departments, which are divided into

divisions, branches, sections, and shops. The departments as of

May 1987 were as follows:

000 Commanding Officer's Staff

200 Management Controls Department and Comptroller

21

300 Engineering Department

400 Quality and Reliability Assurance Department

500 Production Planning and Control Department

600 Production Engineering Department

700 Material Management Department

800 Flight Check Department

900 Production Department Stipulation at V-13-14.

12. The Production Department employs more than 50 percent of

the civilians employed by Jacksonville NARF, and is divided into

four divisions: Process and Manufacturing Division; Avionics

Division; Weapons Division; and Power Plant Division.

Stipulation at V-14.

13. NARF employs individuals in a wide variety of job

classifications, each encompassing different specialized skills

and abilities. Work on aircraft involves a number of job

classifications, including Equipment Cleaners, Sandblasters,

Sheet Metal Mechanics, Aircraft Mechanics, Aircraft Electricians,

Electroplaters, and painters. Work on engines is performed

primarily by Aircraft Engine Mechanics as well as by Equipment

Cleaners, Sandblasters, Electroplaters, Machinists, Painters, and

Pneudraulic Systems Mechanics. Work on components is performed

by employees in a wide variety of job classifications, including

Electronics Mechanics, Instrument Mechanics, Electronic

Integrated Systems Mechanics, Aircraft Mechanics, Sheet Metal

Mechanics, Welders, Aircraft Electricians, Aircraft Ordnance

Systems Mechanics, Electrical Equipment Repairers, Powered

22

Support Systems Mechanics, and Machinists. Stipulation at V-12-

13 .

14. In addition to a broad range of job classification in these

production jobs, NARF also employs a variety of non-production

employees. These include different types of engineers

(aerospace, electronics, and mechanical) and technicians to

provide design services and technical engineering guidance;

Production Controllers, Planners and Estimators, and Progressmen

to schedule, monitor, and expedite the flow of work; Quality

Assurance Specialists to monitor and maintain the quality of

work; numerous trade employees to maintain the physical plant at

which the work is done; Tools and Parts Attendants to store and

deliver materials, tools, and parts; and various' clerical,

accounting, computer, and management personnel to provide

administrative services. Stipulation at V-13.

NARF'S JOB CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM

15. NARF's jobs are organized in standard categories established

by federal law and regulation, and administered by the Office of

Personnel Management, formerly the United States Civil Service

Commission.

16. The Pendleton Act established a centralized personnel

agency to monitor and control civil service employment in the

federal government. This agency, originally the United States

Civil Service Commission later became the Office of Personnel

23

Management as a result of the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978.

Joint Pretrial Stipulation at V-15.

17. The Office of Personnel Management publishes the Federal

Personnel Manual which contains rules and regulations governing

civilian personnel management in the federal government and

instructions and guidance for the implementation, administration,

and review of federal personnel programs. Id.

18. The Office of Personnel Management also has the primary

responsibility for organizing and systematizing the personnel

policies and procedures for federal agencies. Joint Pretrial

Stipulation at V-16.

19. The General Schedule (GS) pay system includes positions

which are primarily professional, administrative, technical, or

clerical in nature.

20. The Office of Personnel Management has developed

tification standards for GS positions which are published in

the Handbook X-118,_Qualification Standards for Positions Under

the— General--Schedule. This handbook presents the minimum

qualifications in terms of the knowledges, skills, and abilities

(KSAs) required for selection to each position as well as the

minimally qualifying level of education or amount of experience.

D. Exh. Nos. 241-43.

21. The Federal Wage System (FWS) covers skilled trades, craft,

and labor jobs. Jobs in FWS are organized into occupations and

job families which are defined in terms of the nature of the work

performed.

24

22. The Office of Personnel Management has developed

qualification standards for FWS jobs. These are described in the

Handbook X-118C. Internal Qualification Guides for Trades and

Labor Occupations. as supplemented by Officer of Personnel

Management internal qualification guides. The handbook includes

a general explanation of the FWS system; identifies knowledges,

skills and abilities and other personnel characteristics,

collectively known as basic worker requirements, necessary for

selection; examining guidelines and a description of the process

for rating applicants. Joint Pretrial Stipulation at V-18.

23. NARF acts within a framework, defined by the Office of

Personnel Management in the Federal Personnel Manual, of which

Department of Defense personnel policy issuances, Department of

the Navy issuances, and command and activity (e.g., NARF)

directives and instructions are a part.

24. The jobs at NARF are classified into two major pay systems:

(1) the General Schedule (GS) pay system which includes the

"white collar" positions, and (2) the Federal Wage System (FWS)

pay system which includes the "blue collar" jobs. Within each

pay system, the various jobs are further identified by pay plan

and occupational series. The following lists the pay plans for

both the GS and FWS pay systems:

Pay System

GS

FWS

Pay Plan Code

GM

GS

WG

Pay Plan

General Schedule Merit Pay Plan

General Schedule

Wage Grade

25

WS Wage Supervisor

WL Wage Leader

WD Production Facilitation

WN Supervisory Production

Facilitation

WT Apprentice

WP Printing

YV Summer Aid

YW Student Aid

Prior to the implementation of the Coordinated Federal Wage

System in the early 1970's, blue collar positions were

designated according to the Wage Board system. One result of the

Coordinated Federal Wage System was the reorganization of the

Wage Board pay plans. The WB (trade, craft and manual labor

rating), WX (inspector rating), and WY (supervisor inspector

rating) pay plans were discontinued. They were replaced,

respectively, by WG, WG, and WS pay plans. Joint Pretrial

Stipulation at V-19-20.

25. The Office of Personnel Management assigns specific series

numbers to jobs in either the GS pay system or the FWS pay

system. For the GS pay system, job series numbers range from 1

to 2,499. Numbers 2,500 and above are used for FWS jobs. The

complete identifying code for any given job consists of first,

the two letter pay plan designation (WG, GS, etc.), followed by

the four digit occupation code, (e.g., 5704), followed by a one

26

or two digit designation of level (e.g., 07 or 7 to indicate

grade 7). Joint Pretrial Stipulation at V-20.

26. All blue collar occupations (Federal Wage System) at NARF

are identified by a four digit code. The first two digits

indicate the job family. The second two digits specify the

particular occupation. For example, 8600 identifies the engine

overhaul family. The third and fourth numbers ranging from 01 to

99, stand for specific occupations within the family. For

example, 8602 identifies the aircraft engine occupation within

the engine overhaul family. Joint Pretrial Stipulation at V-20-

21.

27. Each pay schedule is divided into levels, identified by

numbers, and generally an employee identified by a higher grade

number in either the General Schedule or the Federal Wage System

has higher rate of pay than an employee identified by a lower

grade level. There are, however, exceptions to this rule. For

example, a top step of a particular grade may exceed the first

step of a higher grade, thus making the actual pay of the lower

grade employee exceed that of the higher grade employee, if the

lower grade employee is at the top step of the grade when the

higher grade employee is at the first step of the grade.

Each pay level is further divided into steps, and the higher

the step the higher the base rate of pay. Thus a WG-10, step 2

is likely to be paid more than a WG-10, step 1. The Federal Wage

System grades are divided into five steps with each higher

successive step representing a higher rate of pay. The General

27

Schedule follows the same basic pattern, and there are, in most

grades, ten steps, each having a progressively higher rate of pay

in each grade.

Given the same numerical level and step, an employee in the

regular non-supervisory schedule (WG) makes less than an employee

in the leader schedule (WL), and an employee in the leader

schedule (WL) makes less than an employee in the supervisory

schedule (WS) . For example, the following hourly rates were

taken from the March 23, 1980, Jacksonville wage rates:

WG-10/Step 1 is paid $8.84

WL-10/Step 1 is paid $9.72

WS-10/Step 1 is paid $11.50

Joint Pretrial Stipulation at V-21-22.

28. The’ Office of Personnel Management groups the trades and

labor jobs (FWS) into five categories: (1) Worker-trainee jobs;

(2) support jobs; (3) Apprentice jobs; (4) Jobs emphasizing trade

knowledge; and (5) High-level supervisory jobs. The workers at

NARF fall heavily in the group (4) of "Jobs emphasizing trade

knowledge." Joint Pretrial Stipulation V-22 - 23.

29. Under the FWS system a person can start at the helper level,

move to the worker level, and then to the journeyman level. At

the top level is the foreman. Additionally, some of the job

positions at NARF only utilize one or two of the grade levels

even though there are more on the books (in the Civil Service

Standards) . Another path for becoming a journeyman is to enter

as an apprentice, an4 complete the established training program

28

to become a journeyman. There may be more than one journeyman

level. Most helpers enter at wage grade (WG) level 5 and most

workers are wage grade level 7 or 8. Skilled journeymen are

usually wage grade 9, 10, or 11. Once an employee reaches the

foreman level, his designation usually becomes Wage Supervisor

(WS). Joint Pretrial Stipulation at V-22-23.

ANECDOTAL AND DOCUMENTARY PROOF OF DISPARATE TREATMENT

THE SELECTION PROCESS

1. NARF utilizes a multistep promotion process in which

individual supervisors have numerous opportunities to affect the

promotion decision. NARFrS rating and selection criteria reguire

subjective evaluation by management officials, and its

promotional procedures require management officials to make

discretionary decisions throughout the process. Pretrial

Stipulation at V-25 - V-38; 1 T.T. at 57-70 (Clark); 16 T.T. at

38 (Marti).

2. Once a supervisor determined that a vacancy existed,

management had the responsibility to decide whether to fill the

vacancy through competitive merit promotion procedures or other

means including noncompetitive methods. 16 T.T. at 161-62

(Marti); 12 T.T. at 52; D. Exh. No. 4100 at 28. Management was

supposed to get input from the Civilian Personnel Office but was

not required to heed the advice. Id.

29

3. Management also had the final responsibility of defining the

area of consideration. In most cases, the Civilian Personnel

Office made the decision based on management's past experience in

filling the job. 16 T.T. at 167-68 (Marti).

4. If management decided to fill the vacancy through

competitive merit promotion procedures, a crediting or rating

plan was prepared by the Civilian Personnel Office staffing

specialist in conjunction with management. 16 T.T. at 176-177.

Sometimes the staffing specialist met with "subject matter

experts", usually in fact the supervisors of the target

position, in order to determine what qualifications are required

for the job. The staffing specialist often did not have to meet

with the supervisors because the Civilian Personnel Office was in

constant contact with supervisors. Id. The determination of

qualifications was supposed to be incorporated into the crediting

plan. In making this determination the staffing specialists and

supervisors were supposed to consult Office of Personnel

Management and Civilian Personnel Office documents regarding the

position, and determine a screen-out element for the position.

NARF officials had considerable discretion to adjust the

requirements to suit local needs. Pretrial Stipulation at V—26;

11 T.T. at 16 (Robinson); P. Exh. No 119; 16 T.T. at 11 (Marti);

6 T.T. at 123 (Shapiro); 17 T.T. at 42 (Marti).

5. The screen out element was the first rating element

designated in the Office of Personnel Management Handbook X118C.

Federal Wage System (FWS) applicants must meet this requirement

30

in order to establish basic eligibility for the position. Only

after meeting this requirement could they compete for promotion

and be rated by the panel. 17 T.T. at 23 (Marti). The rating

plan for first-level supervisor for the WG-2600 Electronic

Equipment Installation Family was typical. The screen-out

element was the general "ability to lead or supervise". 16 T.T.

at 143-44, 151 (Marti). In order to assess the ability to lead,

raters were supposed to use five factors: "ability to

communicate", "integrity", "willingness to accept policy",

"fairness and equal treatment", and "knowledge of job". Id. at

146-47. Deciding how to rate employees on these factors required

the use of judgment by the raters. 10 T.T. at 153-176 (Marti).

6. The next determination was whether the vacancy should be

announced as a discrete open and closed promotional announcement,

(Pro-Op) or whether it should be an open continuous promotional

announcement (Pro-Op). An open continuous promotional

announcement is one in which after an initial cutoff date for

the first vacancy, applications continue to be accepted.

Subsequent applications were rated and eligible applicants were

integrated into the existing registers, but there was no

specification of how periodically that could be done. Pretrial

Stipulation at V-26. In open continuous announcements the

initial cutoff date could be manipulated to effect the available

pool of applicants. 6 T.T. at 75; 14 T.T. at 128-129.

7. Later in the time period there were multiple listing

announcements and again the times that were selected were

31

discretionary because the announcement could be reopened for the

receipt of new applications either biannually or at some point

when there were not enough eligible applicants to meet the needs

of the user, another discretionary decision. Pretrial Stipulation

at V-26 - V-27.

8. Promotional opportunity announcements provided a brief

description of the duties to be performed, the qualification

requirements, and the elements which would be rated. For General

Schedule (GS) positions, a statement regarding time-in-grade

requirements was also included. Pretrial Stipulation at V-27.

9. An applicant was supposed to review the vacancy

announcement, complete a Personal Qualifications Statement, SF

171, and deliver it to the Civilian Personnel - Office. The

applicants were supposed to address the rating elements shown in

the announcement, and describe their experience and training on

the SF 171. The vacancy announcement requested that applicants

include the appropriate supervisory appraisals completed by their

immediate supervisors and/or their latest annual performance

ratings, also completed by their supervisors. Other materials

submitted by employees included awards, training, beneficial

suggestions, recommendations and letters of commendation.

Typically, a separate application was required for each

announcement in which the applicant was interested. When an

announcement covered several types of positions, a separate

application was required for each. Pretrial Stipulation at V-27

- V-28; 16 T.T. at 83 (Marti).

32

10. The SF 171 application was used both to rate and select

employees for promotion. In applying the rating standards, the

rater looked at the SF 171, the individual's supplemental sheet

and anything else attached to the application, such as

appraisals, awards, training, education, recommendations,

certificates, beneficial suggestions and letters. 16 T.T. at

151-55 (Marti). The selecting official was given applications

of all individuals on the certificate to use in making

selections. Id. at 180-81.

11. It is impossible to specify the separate weight of any

single element of the promotion process. 17 T.T. at 4 (Marti).

The Navy's personnel expert could not specify the impact or

weight of supervisory appraisals, performance evaluations,

awards, training, experience or any other particular document

used in the promotion process. Id.

12. The Performance Rating Report and the Merit Promotion

Supervisory Appraisal required the supervisor to make subjective

judgments regarding the employee's performance and to rate the

employee as Outstanding, Satisfactory or Unsatisfactory on the

following elements: Quality of Work: "A. Job Knowledge"; "B.

Work Planning and Organization"? "C. Accuracy"; D. Ability To

Interpret Written Instructions" . Quantity of Work: "E. Work

Production"; "F. Ability To Work Under Pressure"; "G. Promptness

of Action." Adaptability: "H. Cooperation"; "I. Ingenuity"? "J.

Dependendability". The form also asked the supervisor to

provide an Overall Annual Rating.

33

13. Upon reviewing the application, the staffing specialist

determines who is eligible to apply for the position, or

sometimes meets with the subject matter experts who will serve on

the rating panel, to determine who is eligible to apply for the

position. The staffing specialist reviewed the application

against the qualification requirements for the position as

published in the PPM Handbook X-118, Qualification Standards for

Positions Under the General Schedule (X-118) for white collar

positions, or the 0PM Handbook X-118C. Job Qualification System

for Trades and Labor Occupations (X-118C) for blue collar jobs,

as modified by local, Navy or Department of Defense instructions,

to determine basic eligibility. An additional document, Internal

Qualification Guides for Trades and Labor Jobs, was also used for

blue collar jobs. Pretrial Stipulation at V-28.

14. Applications for GS positions that were determined to meet

the qualification requirements were then sent to the rating

panel to be evaluated. Applications for FWS jobs that were

determined to meet the acceptable level on the screen-out element

were then sent to the rating panel for final rating evaluation.

Pretrial Stipulation at V-28 - V-29.

15. The basic eligibility determination procedures were

<3ifferent for GS and FWS pay systems. GS positions had time—in-

grade requirements imposed by 0PM. FWS jobs did not have time-

in-grade requirements, however, eligibility of candidates for

FWS jobs was determined at two points: by a staffing specialist

and by the rating panel. The eligibility of candidates for GS

34

positions was determined solely by the staffing specialist.

Pretrial Stipulation at V-29. The rating panel, on which the

supervisor may sit, often has at least the two functions: to

determine who is eligible to apply for the position, and to rate

the actual applicants.

16. For FWS positions, a candidate may have been determined to

be qualified by the staffing specialist but when the application

was sent to the rating panel, the panel, might find the candidate

ineligible. Pretrial Stipulation at V-29 - V-30. It follows

that the design of the process dictates that when an FWS

candidate is ruled ineligible, you cannot tell whether the ruling

came from the staffing specialist or the ruling came from the

rating panel.

17. The rating panel was made up of two or more management

representatives who were knowledgeable about the position or job

to be filled and were at the same or higher grade level as the

vacancy. Sometimes the supervisor of the vacant position was one

of the subject matter experts who served on the rating panel.

Pretrial Stipulation at V-29.

18. The subject matter experts were supposed to independently

review the applications, supervisory appraisals and any

supplemental data against the crediting plan. For each

candidate, panel members recorded their evaluation of each

crediting plan element and added up the scores on the elements to

obtain a total raw score for the candidate. The evaluations were

reviewed by the chairman of the rating panel and the staffing

35

specialist. 16 T.T. at 42 (Marti). Pretrial Stipulation at V-29

- V—30. Though sometimes panel members totalled and discussed

scores without the participation of the staffing specialist. 3

T.T. at 113.

19. The rating process required raters or staffing specialists

to make subjective evaluations of applicants by assigning scores

to rating elements. For example, with respect to the rating of

an applicant on the ability to lead or supervise, NARF's

personnel expert testified that the rating plan stated that a

score at the 2 level indicated "potential or fair experience",

such as the experience of an artisan without supervisory

experience. 16 T.T. at 150-51 (Marti). A score of 3 was for

"good experience," such as having a lead position jvith approval

of small amounts of leave, assigning work load and making sure

things went along but no actual supervisory duties Id.. A score

of 4 was for outstanding or excellent experience, and might be

that the individual has held a snapper position or held a lead

for a considerable amount of time at NARF, private industry, or

the military. Id..

In order to determine if an applicant's experience as a

leader rated a 3 or 4, the rater was supposed to look at the

duties of supervision and balance them against the five rating

factors of ability to communicate, integrity, willingness to

accept policy, fairness and equal treatment and knowledge of job.

Id. at 151-52. Time as a leader would only be "one of many

factors that we look at." Id.. Other factors were quality of

36

performance, particular duties, work situation, and "the entire

situation". Id. at 152-53.

20. Generally, where there was a difference in ratings of more

than two points on the total raw score given by two panel

members for a particular candidate, the reasons for the

differences were discussed and resolved. FWS job applicants who

did not achieve an average score of two points per element were

rated ineligible. For example, a FWS job crediting plan may have

had six elements. To be basically eligible, the applicant must

have achieved at least two points on the Screen-Out Element, as

determined by the Staffing Specialist's initial evaluation, and a

total score of 12 points as determined by the Rating Panel. An

applicant with a total score of 11 would have been ineligible in

this • instance. At the conclusion of the rating panel's

deliberations, the applications were returned to the staffing

specialist. Pretrial Stipulation at V-30.

21. The staffing specialist was supposed to make a second review

after the rating panel completed its task to determine whether

the raw scores were in agreement. The raw scores were then

converted to numerical equivalents by use of an Office of

Personnel Management published conversion table. The Civilian

Personnel Office, then prepared a certificate listing the names

of the candidates from which the Selecting Official could choose.

The procedures as to which names were listed on the certificate

changed several times during the period, but the highest rated

37

candidates were always supposed to be included. Pretrial

Stipulation at V-30 - V-32.

22. In order to be considered highly qualified, an applicant had

to receive a score of 85 or higher. 1 T.T. at 68 (Clark) .

Candidates with scores from 70.0 to 84.9 were considered

qualified. In the event there were ties in the numerical scores,

the staffing specialist normally broke them based on the length

of qualifying experience, or the length of service of the

applicants. Pretrial Stipulation at V-31.

23. Selecting officials had several options in the selection

process. They could use a selection advisory or recommending

panel, they could conduct personal interviews, they could make

the selection, based on the applications alone, or they could

select no one. Section advisory boards were not used very often.

16 T.T. at 110 (Marti) . They were used primarily for upward

mobility positions. Id. There was no requirement for an

interview. Id.

24. If no one was selected, particularly in an open continuous

promotional announcement, the selection process would go back to

the staffing specialist who would continue to collect

applications and ultimately submit them back to the panel. 16

T.T. at 39 (Marti). Pretrial Stipulation at V-33.

25. Selecting officials were not required to use any criteria.

Selecting officials were not restricted to the knowledge, skills

and abilities in making selections. 16 T.T. at 111 (Marti). The

discretion of the selecting official to select or nonselect from

38

a certificate of eligible was absolute. Id. at 165-67 (Marti).

See. e.g.. 23 T.T. at 112 (Aton).

26. In sum, the design of the defendant's promotion system

insured that its operation was interdependent, and that the

supervisors and subject matter experts would play an important

and recurring role in the determination of who gets promoted.

27. The supervisor over the position that has been announced, is

likely to be a member of the rating panel and may also be

advising the selecting official. The supervisor may rate the

very people from whom the selections are to be made, prior to the

issuance of the certificate. The supervisor may determine who

is eligible or ineligible to be rated and, together with the

staffing specialist, have developed the crediting plan or

requirements for the job, which has the effect of determining who

is going to meet the eligibility requirements. At every step

there are people who are participating in other steps of the

process, and their entangled subjective judgments have a critical

impact on an applicant's chances for promotion.

28. The promotion process may begin and end with the selection

picking no one, only to then issue another announcement

for the same position in which the process has to start all over

again as though the first process never occurred. Even after a

certificate is issued, it is still possible to issue a

supplemental certificate to add a list of names or name to the

first certificate. An applicant may be judged ineligible in the

initial step of the application procedure or an applicant may be

39

judged ineligible by the rating panel much further down the line

in the promotion process. Moreover, the whole process may be

side-stepped by the use of a non-competitive procedure such as a

temporary assignment or a temporary transfer or a temporary

promotion which does not require the use of a formal promotional

announcement. 16 T.T. at 42, 161-62 (Marti). Promotion could

also result from reclassification and upgrades, or a promotion

could result from enhancement of duty. Pretrial Stipulation at

V-41; 19 T.T. at 177 (Sanderson). Also after May 7, 1981, when

there were five or fewer promotional eligibles for a particular

position, no formal evaluation was conducted and all

applications were referred directly to the selecting official,

thereby shortcutting the whole procedure. Id. at 25.

29. Although outside hires were technically done through

Orlando, the actual ratings were often done at the NARF because

that's where the subject matter experts were. 10 T.T. at 13-14.

Mrs. Vanderhorst described how the process worked in certain

crafts under Mr. Barilla's jurisdiction:

"We also handled the 171s that would come in

from^ Orlando. When people would apply for

the jobs, they'd send their applications into

Orlando. Orlando would send the applications

to Jacksonville to us, manpower would get them, I would type up the listing of the

supervisors that were going to evaluate the

applications, and when they finished I would

pack them up, give them to Helen Brown and

she would send them back down to Orlando."Id.

30. Since subject matter experts from the NARF rated

applications from Orlando as well as internal applicants they

40

could determine who would be hired from outside as well as who

would be promoted from inside.

31. The Navy's personnel expert was unaware of any validation

studies on any element of the competitive merit staffing process,

other than defense exhibits. 17 T.T. at 33-34 (Marti) . No

written validation study was presented by the Navy.

1973 CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION REPORT AND

EEO AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PLANS

32. Plaintiffs presented evidence that NARF management had

knowledge of discriminatory promotional practices and admitted

its existence in contemporaneous written reports. The reports

also show that NARF failed to correct admitted problems. The

testimony of NARF Deputy EEO officers and NARF employees was

corroborative.

33. Among the duties of the U.S. Civil Service Commission, now

the Office of Personnel Management, was to audit how federal

agencies implement the personnel policies and procedures

promulgated by federal ■ statute and regulation. During the 1973-

85 period, the Commission conducted one such audit. P. Exh. No.

1? 16 T.T. at 160-61 (NARF's personnel expert knew of no other

audits or reviews of NARF's promotion system).

34. The 1973 Civil Service Commission report concluded that

"[m]erit principles and/or regulations are not being adhered to

fully in promotion actions". P. Exh. No.l at 13—14. The report

found "no significant change in the traditional employment

41

patterns of [black] employees" and stated, "[b]lacks are

predominately found in the lower wage grade positions," id. at 8,

as well as an underlying problematic and/or discriminatory denial

of detail assignments, training, awards, and supervisory

appraisals.

35. The critical conclusions of the 1973 Civil Service

Commission report were accepted by NARF's management. P. Exh.

No. 1 at letter of Captain Boeing, dated 28 September 1973, which

declared that it would take remedial action. Id.

36. In 1973 and later years, NARF itself prepared affirmative

action plans in which it admitted the existence of the

promotional discrimination challenged by plaintiffs and resolved

to remedy various specific problems, such as denial of training,

awards, supervisory appraisal and performance evaluations, detail

assignments and unfair rating panels. See infra. As discussed

below in detail, the affirmative action plans constitute

admissions by NARF's management that promotional discrimination

existed, and that remedial measures were necessary to eradicate

discrimination. These remedial measures, which were never

implemented to any significant degree, included rotating detail

assignments, adding blacks to promotion boards and giving blacks

more training.

37. NARF's EEO (Equal Employment Opportunity) Affirmative Action

Plans, which discuss NARF's compliance with Title VII and other

legal and regulatory prohibitions of employment discrimination,

prepared between 1973 and 1978 contain narrative assessments of

42

problems or objectives, and remedial action required. P. Exh.

No. 2 (February 1973 AAP and June 1973 AAP); P. Exh. No. 3; P.

Exh. No. 5; P. Exh. No. 6. Such narrative assessments are

absent from later plans. E.g. . P. Exh. No. 7; P. Exh. No. 11.

38. NARF's EEO Affirmative Action Plans were prepared by the

staff of the EEO office, and reviewed, modified, and signed by

the Commanding Officer. P. Exh. No. 2 (February 1973 AAP & June

1973 AAP); P. Exh. No. 3; P. Exh. No. 5; P. Exh. No. 6; P.

Exh. No. 7; P. Exh. No. 11. NARF' s Commanding Officer was the

NARF' s EEO Officer Id., 1 T.T. at 80-82 (Ware), and was the

final arbiter of what went into the Plans. Id. at 19-21. The

Plans were also approved at higher levels. 1 T.T. at 82 (Ware).

39. Although NARF's Affirmative Action Plans refer generally to

^irionties", blacks are the only minority employees present in

any significant numbers, and general references to minorities in

the Plans were to blacks. 1 T.T. at 130 (Ware).

40. Walter Ware, who testified under subpoena, was NARF's Deputy

EEO Officer between December 1972 through March 1977. 1 T.T. at

74-75. His duties were to monitor and advise the Commanding

Officer of EEO problems and conditions, 1 T.T. at 78, including

briefing the Commanding Officer monthly, and sometimes weekly.

1 T.T. at 78-79. Ware also supervised the EEO office. 1 T.T.

at 80-81

41. Edvie Jean Guy, who testified under subpoena, was NARF's

Deputy EEO Officer between September 1980 through September 1988

43

2 T.T. at 61-62. Her duties were the same as Ware's. 2 T.T. at

62-63.

42. Dwayne Clark worked as an Equal Opportunity Specialist at

NARF from 1973 to 1976, and his responsibilities included

counseling aggrieved employees during the informal process or

pre-complaint stages of the Title VII complaint process, and

attempting to resolve the complaint with members of management,

identifying and keeping track of statistical data to track the

relative progress of minority and white employees, and drafting

Affirmative Action Plans during this period. 1 T.T. at 53-55.

43. As member of the Equal Opportunity Committee Dwayne Clark

was required to assess and identify the problems encountered by

blacks in obtaining promotions and determine why blacks were not

obtaining training opportunities. 1 T.T. at 50-51.

44. Mr. Clark was reassigned as a Labor Relations and Employee

Relations Specialist in the NAS Civilian Personnel Office in

1976, and subsequent to that was reassigned as a Personnel

Management Specialist. As a Personnel Management Specialist Mr.

Clark's responsibilities included writing disciplinary actions

against employees, that is recommending the level of action based

upon the degree of severity of the infraction, and as a

Classification Specialist, evaluating and analyzing the grade

level or pay plan level of both wage grade and general schedule

positions. 1 T.T. at 55-56.

44

EEO DOCUMENTS

45. An evaluation of NARF's personnel management practices

conducted in 1973 by the U.S. Civil Service Commission found

that:

There has been no significant change in the traditional

employment patterns for [black] employees, except for

the [recent promotion of] two wage supervisors . . .

Blacks are predominantly found in the lower wage grade

positions, with a limited number in lower grade

Classification Act [GS] positions . . . [w]ith the

exception of the recently appointed EEO Coordinator,

GS-9, there are no [blacks] in positions GS-9 and above.

P. Exh. No. 1 at 8.