Evans v. Jeff D. Brief for Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

September 6, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Evans v. Jeff D. Brief for Amici Curiae, 1985. 457ed42f-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8736bbac-5bd0-46e8-b170-d91b3099f598/evans-v-jeff-d-brief-for-amici-curiae. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

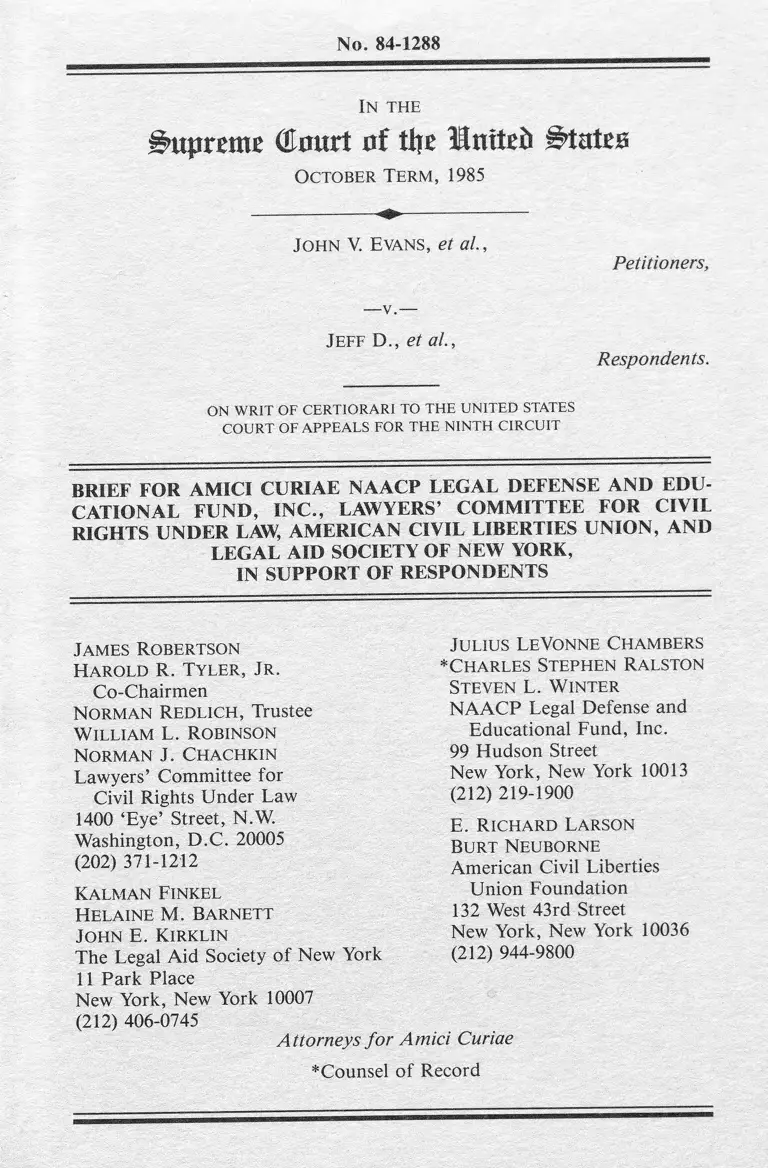

No. 84-1288

In the

Supreme (Emtrt uf tlje United

O ctober Term , 1985

J ohn V. Evans, et a i,

Petitioners,

Jeff D., et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR AMICI CURIAE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDU

CATIONAL FUND, INC., LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW, AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION, AND

LEGAL AID SOCIETY OF NEW YORK,

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

James Robertson

Harold R. Tyler , Jr .

Co-Chairmen

NORMAN Redlich , Trustee

W illiam L. Robinson

Norman J. Chachkin

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 ‘Eye’ Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Kalman F inkel

Helaine M. Barnett

John E. Kirklin

The Legal Aid Society of New York

11 Park Place

New York, New York 10007

(212) 406-0745

Julius LeVonne Chambers

♦Charles Stephen Ralston

Steven L. W inter

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

E. R ichard Larson

Burt Neuborne

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, New York 10036

(212) 944-9800

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

♦Counsel of Record

QUESTION PRESENTED

May a court, in determining post

judgment fee entitlement under 42 U.S.C. §

1988 in a case in which only injunctive

relief is sought, approve a coerced waiver of

all attorneys fees sought by defense counsel

on the eve of trial as a condition of

providing relief on the merits through a

consent decree?

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page :

Question Presented........... i

Table of Contents........................... ii

Table of Authorities....................... iii

Interest of Amici.... ........................1

Summary of Argument....... ..................4

Argument....................... ............. 9

A. The Nature of Civil Rights

Practice Makes Civil Rights

Lawyers Uniquely Vulnerable

to Coerced Waivers of Fees, a

Practice Which if Approved

Would Result in No Fees

Whatsoever..............................9

B. Coerced Waivers of Fee Entitlement

Under 42 U.S.C. § 1988, Obtained

as Prerequite Conditions for i

Merits Settlements, Contravene

the Purposes of the Statute........... 19

C. Enforcement of Congress' Intent,

by Barring Coerced Fee Waivers,

Will not Discourage Settlements

or Make More Difficult the Quick

Disposition of Nuisance Suits........ 39

D. In View of the Federal Courts'

Inconsistency in Confronting

Coerced Fee Waivers, Specific

Guidance Must Be Provided by

this Court Barring Coerced

Fee Waivers 51

Page:

Conclusion. ........................ . ........ 61

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases;

Alyeska Pipeline Service Corp. v .

Wilderness Society, 421 U.S.

240 (1975) ...................... 25, 26

American Family Life Assurance

Company v. Teasdale, 733 F.2d

559 (8th Cir. 1984) .................... 46

Arnold v. Burger King Corp., 719

F. 2d 63 (4th Cir. 1983) ....... .........46

ASPIRA of New York, Inc. v. Board

of Education of the City of New

York, 65 F.R.D. 541 (S.D.N.Y.

1975) ................................ 31, 32

Barrentine v. Arkansas-Best

Freight System, 450 U.S.

728 ( 1981) 20

Blackledge v. Perry, 417 U.S.

21 (1974 ) .................... ........... 23

Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S. ,

104 S.Ct. 1541, 79 L.Ed.2d

891 ( 1984) .................... passim

Bradley v. School Board of City

of Richmond, 416 U.S. 696

(1974 ) ....................................1

- i i i -

Cases; Page:

Brooklyn Savings Bank v. O'Neil,

324 U.S. 697 ( 1944) ............. 20, 21 , 52

Cannon v. University of Chicago,

441 U.S. 677 ( 1979) ..................... 36

Carey v. Piphus, 435 U.S. 247

(1978) .... ......... ..................... 11

Charves v. Western Union

Telegraph Company, 711 F.2d

462 (1st Cir. 1983) ..................... 46

Chattanooga Branch, NAACP v.

City of Chattanooga, No.

79-2111 (E.D. Tenn. Dec. 2,

1981), appeal dismissed,

Nos. 82-5013 & 82-5016 (6th

Cir. April 29, 1982) ............... .....56

Christiansburg Garment Co. v.

EEOC, 434 U.S. 412 (1978) ............ 1, 46

City of Newport v. Fact

Concerts, Inc., 453 U.S.

247 (1981) ............................... 12

Clanton v. Allied Chemical

Corporation, 459 F. Supp.

282 (E.D. Va. 1976) ......................37

Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F.2d

880 (D.C. Cir. 1980) ................. 2, 43

Dennis v. Chang, 611 F.2d 1302

(9th Cir. 1980) ...... .............. 44, 45

El Club del Barrio v. United

Community Corporations, 735

F. 2d 98 (3d Cir. 1984) ...................54

IV

Cases: Page:

Ellison v. Schilling, Civ. No.

L-80-23 (N.D. Ind. July 11,

1983) ..........................

Ford Motor Company v. EEOC,

458 U.S. 219 (1982) ............

Freeman v. B & B Associates, 595

F. Supp. 1338 (D.D.C. 1984) ___

Gibbs v. Town of Frisco City,

626 F.2d 1218 (5th Cir. 1980) .,

Gillespie v. Brewer, 602 F. Supp.

218 (N.D. W.Va. 1985) ......... .52, 54

Hall v. Cole, 412 U.S. 1 (1973) .. .21, 28

Hanrahan v. Hampton, 446 U.S.

754 (1980) ..................... .24, 31, 34

Harlow v. Fitzgerald, 457 U.S.

800 (1982) .....................

Henry v. Gross, 84 Civ. 8399

(TPG) (S.D.N.Y. June 18, 1985) .,

Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S.

424 ( 1983) ..... .......... 1 , 4, 24, 41, 47

Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678

( 1978) ....................... 1 , 24, 39, 58

Incarcerated Men of Allen

County v. Fair, 507 F.2d

281 (6th Cir. 1974) ............. .31, 32

Johnson v. Georgia Highway

Express Co., 488 F.2d 714

(5th Cir. 1974) .......................... 2

v

Cases: Page:

Lazar v. Pierce, 757 F.2d

435 ( 1st Cir. 1985) ........ . 22, 52, 55

Leisner v. New York Telephone

Co., 398 F. Supp. 1140

(S.D.N.Y. 1974 ) .................. .... 37

Lipscomb v. Wise, 643 F.2d 319

(5th Cir. 1981) ....................

Lisa F. v. Snider, 561 F. Supp.

724 (N. D. Ind. 1983 ) ... ........ . .41, 53

Maher v. Gagne, 448 U.S. 122

( 1980 ) ..... ................... . 24, 33, 40

Marek v. Chesny, 53 U.S.L.W.

4903 (U.S. June 27, 1985) ........ 6 , 43, 47

Moore v. National Ass'n of

Securities Dealers, 762

F.2d 1093 (D.C. Cir. 1985) ..... 52, 55, 59

Nadeau v. Helgemoe, 581 F.2d

275 (1st Cir. 1978) ................ . .... 41

Newman v. Piggie Park Enter

prises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400

(1968) .................... ......... .passim

New York Gaslight Club, Inc. v.

Carey, 447 U.S. 54 (1980) ..... .

North Carolina v. Pearce, 395

U.S. 711 (1969) ........... ........

Northcross v. Board of Educa

tion of Memphis, 412 U.S.

427 ( 1973) ... .....................

Oldham v. Ehrlich, 617 F.2d

163 (8th Cir. 1980) .... ...........

vi

Cases: Page:

Palmigiano v. Garrahy, 616 F.2d

598 (1st Cir.), cert, denied,

449 U.S. 839 (1980) 10

Parker v. Matthews, 411 F. Supp.

1059 (D.D.C. 1976), aff'd sub

nom., Parker v. Califano,

561 F.2d 320 (D.C. Cir. 1977) .......31, 32

Pigeaud v. McLaren, 699 F.2d

401 (7th Cir. 1983) 47

Prandini v. National Tea Co.,

557 F. 2d 1015 (3d Cir. 1977) ............ 54

Pulliam v. Allen, 466 U.S. ,

104 S.Ct. 1970, 80 L.Ed.2d

565 (1984) ............................... 24

Regalado v. Johnson, 79 F.R.D.

447 (N.D. 111. 1978) ................ 10, 52

Roadway Express, Inc. v. Piper,

447 U.S. 752 (1980) ...................... 47

Schulte v. Gangi, 328 U.S.

108 (1946 ) .......................... 20 , 21

Shadis v. Beal, 685 F.2d 824

(3d Cir.), cert, denied,

459 U.S. 970 ( 1982) ...................... 52

Supreme Court of Virginia v.

Consumers Union, 446 U.S.

719 (1980) ................ 24

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S.

1 (1971) ................................... 6

- vii -

Cases : Page;

White v. New Hampshire Depart

ment of Employment Security,

455 U.S. 445 (1982) .... .1, 34, 35, 41, 60

Wilko v. Swan, 346 U.S. 427

(1953) .............................. 22, 52

Statutes and Rules:

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title

VII, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e, et seq. ....11, 13

Civil Rights Attorney's Fees

Awards Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1988 ........... . ............ passim

Fed R. Civ. P.

Rule 11 ... 47

Rule, 12(b) .......... 46

Rule 16 ............................. 58, 61

Rule 23 .............................. 58, 61

Rule 56 ............. ......46

Rule 68 ........................ 47

Legislative History:

H.R. Rep. No. 1558, 94th Cong.,

2d Sess. (1976 ) ..................... passim

- viii -

P a g e ;

S. Rep. No. 1011, 94th Cong.,

2d Sess. reprinted in 1976

U.S. Code, Cong. & Ad. News

5908 ................................. passim

Municipal Liability Under 42

U.S.C. § 1983; Hearings on

S. 585 Before the Subcomm. on

the Constitution of the Senate

Comm, on the Judiciary, 97th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1981) ................. 39

Attorney's Fees Awards; Hearings

on S. 585 Before the Subcomm.

on the Constitution of the

Senate Comm, on the Judiciary,

97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982) ............. 38

H.R. 5757, 98th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1984) 38

S. 2802, 98th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1984) ................................... 38

Legal Fees Equity Act: Hearings

on S♦ 2802 Before the Subcomm.

on the Constitution of the

Senate Comm, on the Judiciary,

98th Cong., 2d Sess. ( 1984) .............. 38

S. 1580, 99th Cong., 1st Sess.

( 1985) ................................... 39

Ethics Rules and Opinions;

American Bar Association, Model

Code of Professional Responsibility

DR 5-101 (A) 7

IX

Pa g e ;

EC 5-2 ..................................7

EC 7-7 ...... ................ .......... 7

American Bar Association, Model

Rules of Professional Conduct

Rule 1.2(a) ....... ............ ........ 7

Committee on Legal Ethics, The

District of Columbia Bar,

Opinion No. 147, reprinted in

113 Daily Wash. Law Rptr. 389

(Feb. 27, 1985) ........ ..................7

Committee on Professional and

Judicial Ethics of New York

City Bar Ass'n, Opinion No.

80-94, 36 Record of New York

City Bar Ass'n 507 (Nov. 1981)

amended and reissued in

Opinion No. 82-80 (Dec. 1983) .... ...... 54

Law Review Articles:

Bartholet, Application of Title

VII to Jobs in High Places, 95

Harv. L. Rev. 945 ( 1982) ................ 12

Comment, Settlement Offers Con-

ditioned~~Upon Waiver of Attorneys'

Fees: Policy, Legal, and Ethical

Considerations, 131 U. Pa. L. Rev.

793 ( 1983) ............................... 57

x

Page :

Kraus, Ethical and Legal Concerns in

Compelling the Waiver of Attorney's

Fees by Civil Rights Litigants in

Exchange for Favorable Settlement of

Cases under the Civil Rights Attorney's

Fees Awards Act of 1976, 29 Vill. L.

Rev. 597 ( 1984) .... ..................... 54

Levin, Practical, Ethical and Legal

Considerations Involved in the

Settlement of Cases in Which Statutory

Attorney's Fees Are Authorized, 14

Clearinghouse Review 515 ( 1980) ........ 57

xi

BRIEF FOR AMICI CURIAE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND,

LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW,

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION, AND

_______ LEGAL AID SOCIETY OF NEW YORK________

INTEREST OF AMICI 1/

Amici are public interest law organiza

tions that have substantial experience in the

litigation of civil rights cases subject to

various statutes providing for awards of

attorneys fees, particularly the Civil Rights

Attorney's Fees Awards Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1988. We have been involved in many cases,

either as counsel for parties or as amicus

curiae, which have established basic stand

ards for awarding f e e s . —/

1. Letters consenting to the filing of this Brief

have been lodged with the Clerk of Court.

2. E.g., Blum v. Stenson, 104 S.Ct. 1541, 79 L.Ed.2d

891 (1984); Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424 (1983);

White v. New Hampshire Department of Employment Secu

rity, 455 U.S. 445 (1982); Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S.

678 (1978); Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434

U.S. 412 (1978); Bradley v. School Board of City of

Richmond, 416 U.S. 696 (1974); Northcross v. Board of

Education of Memphis, 412 U.S. 427 (1973); Newman v.

Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968);

[footnote cont'd]

1

Our interest in the issues presented by

this case is two-fold. First, we depend on

donated services of attorneys in the private

bar to assist us in conducting litigation.

In our experience, the potential for fee

awards to prevailing parties in such litiga

tion has increased the willingness of the

private bar to participate in civil rights

cases. To the extent that fees and costs

become unavailable even when the party re

ceiving pro bono representation prevails, the

availability of donated services will de

crease .

Second, we also depend to a substantial

degree on fee awards for income necessary to

carry out, through our own staff, our pro

grams of providing legal services to the

victims of civil rights violations. Thus,

the availability of fee awards is essential

Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F.2d 880 (D.C. Cir. 1980);

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express Co., 488 F.2d 714

(5th Cir. 1974).

2

both to the continued provision of legal

services and to the vigorous enforcement of

the civil rights statutes in general.

We are convinced that the judgment of

the court below is correct. Allowing defense

counsel to offer lawyers for plaintiffs in

civil rights or other injunctive actions

certain, meaningful relief for their clients

-- on condition that statutory fee entitle

ments be waived — in theory pits plaintiffs

against their attorneys. In fact, long-

settled ethical principles, prudence and

compassion dictate that plaintiffs' counsel

in such cases will be compelled to waive

fees. If this tactic is approved by this

Court, it would destroy the efficacy of the

civil rights acts and would totally undermine

the intent of Congress when it made attorneys

fees available in such suits.

3

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Congress passed the Civil Rights Attor

ney's Fees Awards Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. §

1988 ("the Fees Act"), to increase the avail

ability of counsel to represent plaintiffs in

3 /suits brought under applicable federal law—/

by authorizing recovery of reasonable compen

sation for attorneys' services where plain

tiffs prevail on their claims. See generally

Blum v. Stenson, 104 S.Ct. 1541, 79 L.Ed.2d

891 (1984); Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S.

424 (1983). In the absence of "special cir

cumstances [which] would render such an award

unjust,"— ^ the liability of a defendant whose

conduct violates a statutory or constitu-

3. The Fees Act applies to suits under 42 U.S.C. §§

1981, 1982, 1983, 1985 and 1986, and to suits to en

force provisions of 20 U.S.C. §§ 1681 et seq. or 42

U.S.C. §§ 2000d et seq.

4. Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc,, 390 U.S.

400, 402 (1968), quoted with approval in S. Rep. No.

1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 4, reprinted in 1976 U.S.

Code, Cong. & Ad. News 5908, 5912; and quoted in H.R.

Rep. No. 1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 6 (1976).

- 4

tional obligation encompassed by the applic

able statutes is expanded to include a fee

award to the prevailing plaintiff. "If suc

cessful plaintiffs were routinely forced to

bear their own attorney's fees, few aggrieved

parties would be in a position to advance the

public interest by invoking the injunctive

powers of the federal courts."— /

This case involves perhaps the most

extreme factual situation in which government

defendants, in a private action brought to

compel compliance with these important public

policy requirements, seek to avoid their

statutory liability under the Fees Act by

trying to condition an offer of substantial

relief on the merits to plaintiffs upon their

lawyers' abandonment of any fee entitlement.

5. Newman, 390 U.S. at 402, quoted in S. Rep. No.

1011, supra note 4, at 3, reprinted in 1976 U.S. Code,

Cong. & Ad. News at 5910; and quoted in H.R. Rep. No.

1558, supra note 4, at 6.

5

Unlike the "lump sum" offer context in

Marek v. Chesny, 53 U.S.L.W. 4903, 4905 (U.S.

June 27, 1985), in which the client, in de

ciding whether to accept a monetary offer of

settlement, must confront some necessary

reduction of his recovery in order to permit

his counsel to be compensated, plaintiffs in

an injunctive suit such as in this case will

not have their recovery diminished in the

slightest by waiving the right to prosecute a

statutory fee claim against the defendant.

For this reason, when defense counsel in such

a case propose a substantial merits settle

ment conditioned on a fee waiver, they are

knowingly presenting the plaintiffs and their

attorneys with a "loaded game board"— / — an

offer which plaintiffs could have no reason

whatever to reject and which their lawyers

cannot ethically or morally advise them to

6. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educa-

tion, 402 U.S. 1, 28 (1971).

6

7 /r e j e c t '

It is precisely the devotion of plain

tiffs' counsel to their ethical obligations

7. Plaintiffs in this case are a class of indigent

juveniles, committed involuntarily to state institu

tions , who necessarily had no liability to their Legal

Services counsel for either fees or costs. In these

circumstances, no attorney could, consistent with his

ethical obligation to place the client's interests

above his own, advise rejection of merits relief which

promised some change in allegedly unconstitutional and

dangerous conditions of confinement simply because

counsel's costs would not be reimbursed or fees not

awarded to him. See American Bar Association, Model

Code of Professional Responsibility DR 5-l0l(A) ("Ex

cept with the consent of his client after full disclo

sure, a lawyer shall not accept employment if the

exercise of his professional judgment on behalf of his

client will be or reasonably may be affected by his

own financial, business, property, or personal inter

ests" ); id,, EC 5-2 ("A lawyer should not accept

proffered employment if his personal interests or

desires will, or there is a reasonable possibility

that they will, adversely affect the advice to be

given or services to be rendered the prospective

client"); id., EC 7-7 ("[I]t is for the client to

decide whether he will accept a settlement- offer");

American Bar Association, Model Rules of Professional

Conduct Rule 1.2(a) ("A lawyer shall abide by a

client's decision whether to accept an offer of set

tlement of a matter"); Committee on Legal Ethics, The

District of Columbia Bar, Opinion No. 147, reprinted

in 113 Daily Wash. Law Rptr. 389 (Feb. 27, 1985)

("Plaintiff's counsel owes undivided loyalty to the

client and is obliged to exercise his judgment in

evaluating the settlement free from the influence of

his or her organization's interest in a fee. DR 5-

101(A)").

7

to their clients in this, and in similar

cases, which places in the hands of defense

counsel a potent weapon to defeat the policy

underlying the Fees Act. Attorneys in pri

vate practice who accept pro bono referrals

and who are confronted after years of litiga

tion with coerced waivers of fees are unlike

ly to continue to provide representation in

such cases in the future unless their finan

cial burden is eased in accordance with con

gressional intent. Public interest law

organizations such as amici will be less able

to undertake representation in such cases

without fee awards when their clients pre

vail. Thus, allowing defendants to coerce

waivers of fee awards as a condition of mak

ing available substantial merits relief

through settlement will directly impede real

ization of the purposes of the Fees Act.

8

ARGUMENT

In civil rights injunctive suits such as

this case, federal courts cannot condone,

much less enforce, defense efforts to coerce

fee waivers by conditioning substantial

merits relief for plaintiffs upon counsel's

abandonment of statutory fee entitlement.

A. The Nature of Civil Rights Practice

Makes Civil Rights Lawyers Uniguely

Vulnerable to Coerced Waivers of

Fees, a Practice Which if Approved

Would Result in No Fees Whatsoever

In order to understand fully the pro

blems that arise when defendants demand a

waiver of fees as the price for settling a

civil rights case, particularly one in which

only equitable relief is sought, it is neces

sary first to understand the relationship

between counsel and client in a typical civil

rights suit. That relationship is very dif

ferent from traditional commercial or contin

gent fee practices, in which the client un-

9

dertakes a specific monetary obligation to

the attorney, based either upon an agreed

(usually hourly or daily) rate, or upon a

percentage of the ultimate recovery in cases

where monetary relief is sought.

1. In the vast ma j ority of civil

rights cases, plaintiffs are unable to pay

any fees whatsoever/ Further, by statute,

court rule, or Internal Revenue Service regu

lation, most legal services and legal aid

organizations like amici are prohibited from

charging fees to their clients.2 / Occasion-

8. This fact has been widely recognized by the lower

federal courts, see, e.g,, Lipscomb v. Wise, 643 F.2d

319, 320 (5th Cir. 1981); Regalado v, Johnson, 79

F.R.D, 447, 451 (N.D. Ill, 1978); and it provided the

basic premise for Congress' enactment of the Fees Act,

see infra at 23-30.

9. For example, private organizations in New York

that provide legal assistance are chartered by the

courts as legal aid societies which ordinarily are

prohibited from charging fees. Congress specifically

intended that such groups receive awards under the

Fees Act, see H.R. Rep. No. 1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess.

8 n.16 (1976); Palmigiano v, Garrahy, 616 F.2d 598,

601-02 (1st Cir.), cert, denied, 449 U.S. 839 (1980).

10

ally, civil rights plaintiffs can afford to

pay some of the costs of the litigation or a

reduced fee. But in most instances, we rei

terate, the client has no written or unwrit

ten duty to compensate counsel for his ser

vices .-!£/

In many civil rights cases, even where

monetary relief is demanded, the amounts

likely to be recovered will not be large

enough to cover the reasonable value of the

attorneys' services in the 1 it igat ion .-12/

10. As noted, civil rights and legal aid organiza

tions may not create such an obligation in a retainer

agreement. While private pro bono counsel might do

so, plaintiffs in these cases, many of whom have

already suffered from harassment by legal or govern

mental authorities, are often reluctant to sign such

agreements. The object of the Fees Act was to make it

unnecessary for civil rights plaintiffs to assume fee

payment obligations in order to secure counsel.

11. For example, suits to redress the invasion of

fundamental constitutional rights may produce only

nominal damages, Carey v. Piphus, 435 U.S. 247, 266-67

(1978); the requirement that even a wronged party

mitigate his damages may reduce a recovery, see, e.g,,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g) (interim earnings to be de

ducted from back pay award); in suits against public

officials, immunity doctrines and special defenses may

limit or even bar the recovery of damages, see, e.g,,

[footnote cont'd]

11

Moreover, as is true here and as this Court

noted in Newman v. Piqqie Park Enterprises

Inc., 390 U.S. at 402, many cases involve

Harlow v. Fitzgerald, 457 U.S. 800 (1982) (qualified

immunity); City of Newport v. Fact Concerts, Inc., 453

U.S. 247 (1981) (punitive damages unavailable from

municipal defendants); or the offer of partial relief

pendente lite may toll accrual of monetary entitle

ments, see Ford Motor Company v. EEOC, 458 U.S. 219

(1982). In the typical individual employment discrim

ination case, the back pay award will be too small

plausibly to justify either a contingent fee or a fee

premised on reasonable hourly rates for time expended

to obtain a favorable result. Most, but not all,

Title VII cases have involved lower-level, "blue-

collar" positions, see Bartholet, Application of Title

VII to Jobs in High places, 95 Harv. L. Rev. 945, 948-

49 (1982); since monetary recovery in such cases is

restricted to back pay, the amount of recovery is

necessarily limited by the lower prevailing salaries

for these jobs. Thus, at New York City rates for

attorneys with about two years of experience, see Blum

v. Stenson, 79 L.Ed.2d at 897 n.4; Bradford vT~'BlumT~

507 F. Supp. 526 (S.D.N.Y. 1981), an individual Title

VII case requiring 200 hours of lawyer time for fil

ing, discovery and trial would, if handled by a rela

tively young attorney, still require a fee of $19,000

exclusive of costs — more than a year's back pay for

many entry-level jobs. Recoveries are generally small

even in damage actions for killings brought under 42

U.S.C. § 1983, see, e,g,, Gibbs v. Town of Frisco

City/ 626 F.2d 1218, 1220 (5th Cir. 1980) (plaintiff's

son shot and killed by local police; damage award of

$12,000 and fee award of $8,000).

12

only injunctive relief-!!/ All of these

cases, however, are precisely the lawsuits

whose initiation and litigation Congress

wished to encourage through the fee award

mechanism of 42 U.S.C. § 1988.

Thus, the typical civil rights lawsuit

subject to the Fees Act has the following

characteristics: (a) the plaintiff has no or

only a very limited obligation either to

12. Amici do not mean to suggest that serious ethical

and public policy problems do not exist in cases where

relief other than an injunction is at issue. In liti

gation enforcing Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, it is now increasingly common for defendants to

offer a lump sum representing back pay and fees in

total settlement of a case. Since it is rare that the

lump sum is sufficient both to cover the individual

back pay claims of the class members (so as to make

them whole) and to compensate their attorneys, the

interests of the class members are pitted against

those of their attorneys. And since these actions are

class actions in which there is no contractual obliga

tion on the part of either the named plaintiffs or the

class itself to pay fees, the conflicts cannot be re

solved by submission to the clients.

The Court is not faced with such questions in the

case before it, however, and we limit our discussion

in this Brief to demands for complete waiver of fee

entitlements in suits where no monetary relief has

been sought but in which defendants offer substantial

merits relief.

13

provide funds for the costs of litigation or

to compensate his counsel for legal services;

and (b) once the attorney-client relationship

comes into being, plaintiff’s counsel owes

his client the same quality, zeal and effica

cy of representation which he would provide

to a paying client, as required in bar disci

plinary codes. Recognizing these facts,

Congress created, in the Fees Act, an obliga

tion of unsuccessful defendants in civil

rights cases to compensate plaintiffs'

attorneys for their services, in order to

encourage and attract lawyers to provide

representation in these cases.

2. Given this context, the problems

faced by plaintiffs' counsel when the issues

on the merits of a case and the availability

of attorneys fees are linked, in a single

offer proposing waiver of the latter in ex

change for substantial relief on the former,

14

are totally different than in ordinary tort

or commercial litigation.

For example, in a personal injury case

where there is a contingent fee retainer,

client and counsel will share proportionately

in any recovery and the client's decision

whether to accept a settlement will be sub

ject to the client's obligation to share the

proceeds with his attorney. While some dif

ferences of opinion may persist which are

detrimental to the attorney's interest in

maximizing his remuneration, see Br. for U.S.

at 24-25, civil rights suits in which a fee

waiver is demanded differ from this situation

in at least two very significant respects,

(a) So long as there is some recovery for the

client, there is some recovery for counsel;

the two are inextricably linked and cannot be

manipulated one against the other by defense

counsel. (b) There is no strong public poli

cy, much less a federal statute, providing

15

that counsel for successful plaintiffs should

receive reasonable compensation for their

time and effort, to be paid by the defendant.

Similarly, in a case in which the client

has agreed to compensate his counsel at an

established rate, irrespective of the results

of the litigation, the relationship between

attorney and client is impervious to the

tactics of defense lawyers and is unaffected

by any public policy, save that favoring its

confidentiality.

In each of these situations, while dif

ferences may occur, the personal and profes

sional interests of counsel are at least

generally aligned with the interests of the

client when a settlement is proposed. In the

typical civil rights case, however, the si

tuation is diametrically opposite. Because

the client is under no financial obligation

to pay the attorney, a settlement offer of

substantial merits relief conditioned upon a

16

fee waiver necessarily places the personal

interest of the attorney, the professional

interest of the attorney, and the interest of

the client, in conflict. As the Committee on

Legal Ethics of the District of Columbia Bar

aptly put it, supra note 7:

Defense counsel thus are in a uni

quely favorable position when they

condition settlement on the waiver

of the statutory fee: They make a

demand for a benefit that the

plaintiff's lawyer cannot resist as

a matter of ethics and one in which

the plaintiff has no interest and

therefore will not resist.il/

13. These concerns are not abstract or theoretical.

Amici and the attorneys with whom they work have

experienced the problems outlined above in many dif

ferent contexts. In fact, we recently have all been

repeatedly faced with the impossible choice between

obtaining relief for our clients and forfeiting our

statutory entitlement to the fees that would enable us

to bring other actions to enforce civil and constitu

tional rights.

For our cooperating attorneys who are in private

practice and, therefore, dependent on fees for their

very livelihood, the problem is even more severe. We

know of attorneys who have abandoned civil rights

practice because of the widespread use of tactics such

as those employed by the petitioners' attorneys in the

present case. The combination of the loss of income

and the continued threat of being placed in ethical

dilemmas has forced attorneys, otherwise willing to be

involved in the enforcement of the civil rights laws,

[footnote cont'd]

17

Under our adversary system of litiga

tion, counsel are encouraged to compromise

claims favorably to their clients even if the

result is to afford somewhat more or less

than complete and exact compensation to the

victim of wrongdoing. Petitioners and their

amici are frank to advise this Court, how

ever, that they read prevailing principles to

require defense counsel to seek a waiver (not

a compromise) of fees as part of any settle

ment in a civil rights c a s e T h e issue in

this case is thus whether coercing a fee

waiver in settlement of a case subject to the

Fees Act is consistent with that statute —

to abandon this phase of their practice or to limit it

to those few clients who can contract to pay a full

fee out of their own pockets.

14. See, e.g,, Pet. Br. at 31-35; Br. of Alabama, et

al., at 52-53; U.S. Br. at 23; City of New York Br. at

13; but see Br. of Council of State Governments, et

al., at 4 ("The narrow question presented to the court

of appeals for review in this case was the propriety

of defendant's insistence on a waiver of plaintiff's

attorney's fees as a condition of settlements. Amici

take no position with respect to this issue").

18

and it is to that question which we now turn.

B. Coerced Waivers of Fee Entitlement

Under 42 U.S.C. S 1988, Obtained As

Prerequisite Conditions for Merits

Settlements, Contravene the Pur

poses of the Statute

Petitioners and their amici argue that

coerced fee waivers are permissible merely

because the Fees Act does not bar them in

haec verba These arguments, however,

wholly overlook Congress' purposes in enact

ing the Fees Act.

1. It has never been the rule that a

statutory scheme may be vitiated and congres

sional purposes frustrated through ingenious

construction or devious stratagems which were

neither anticipated nor explicitly prohibited

at the time of enactment. For example, this

Court has long refused to permit the direct

15. See pet. Br. at 12-13; Br. of Equal Employment

Advisory Council at 8-9; Br. for Alabama, et al., at

14-17; U.S. Br. at 21-22.

19

or indirect waiver of the minimum wage re

quirements of the Fair Labor Standards Act.

E.g., Barrentine v. Arkansas-Best Freight

System, 450 U.S. 728 (1981); Schulte v.

Gangi, 328 U.S. 108 (1946 ); Brooklyn Savings

Bank v. O'Neil, 324 U.S. 697 (1944). In its

opinion in the seminal case in this line,

O'Neil, the Court justified its decision on

the basis of the overall policy goals of the

statute:

Neither the statutory lan

guage, the the legislative reports

nor the debates indicates that the

question at issue was specifically

considered and resolved by Con

gress. In the absence of evidence

of specific Congressional intent,

it becomes necessary to resort to a

broader consideration of the legis

lative policy behind this provision

as evidenced by its legislative

history and the provisions in the

structure of the Act.

324 U.S. at 705-06 (footnotes omitted).

Indeed, O'Neil is particularly apt since the

congressional purpose underlying the Fair

Labor Standards Act was to ameliorate the

20

results flowing from bargaining between eco

nomically unmatched and unequal interests:

The statute was a recognition of

the fact that due to the unequal

bargaining power as between employ

er and employee, certain segments

of the population required Federal

compulsory legislation to prevent

private contracts on their part

which endangered national health

and efficiency and as a result the

free movement of goods in inter

state commerce.... No one can

doubt but that to allow waiver of

statutory wages by agreement would

nullify the purposes of the Act.

We are of the opinion that the same

policy considerations which forbid

waiver of basic minimum and over

time wages under the Act also pro

hibit waiver of the employee's

right to liquidated damages.

Id. at 706-07 (footnote omitted) .-M/ The

16. It is the peculiar history of the Fair Labor

Standards Act, as construed by this Court in O'Neil

and Schulte, rather than some generically different

approach to writing statutes, which thus accounts for

the unusual language of 29 U.S.C. § 253(a), relied

upon by the Solicitor General, see U.S. Br. at 21.

That section of the Portal-to-Portal Pay Act was

drafted to overrule O'Neil and Schulte as to liqui

dated, but not compensatory damages, and it was

prompted by the specific circumstances in which those

cases arose. It would be ludicrous to suggest that

after those decisions, it was incumbent upon Congress

to add similar language to every federal statute which

created rights enforceable by individuals. Cf_. Hall

[footnote cont'd]

21

same inequalities of access and bargaining

power motivated Congress' enactment of the

Fees Act.-i-̂ -/

v. Cole, 412 U.S. 1 (1973) (attorneys' fees awarded in

suit to enforce statute despite absence of explicit

statutory authorization). Moreover, no suggestion has

been advanced by petitioners or their amici, and none

can be supported in the legislative history, that the

Congress which passed the Fees Act intended to author

ize defendants to coerce fee waivers in settlements.

It is equally significant that the decision in

Wilko v. Swan, 346 U.S. 427 (1953), also cited in U.S.

Br. at 21-22, likewise relied upon the general pur

poses of the Securities Act rather than any provision

explicitly addressing arbitrability:

Two policies, not easily reconcilable,

are involved in this case. Congress has

afforded participants in transactions

subject to its legislative power an oppor

tunity generally to secure prompt, economi

cal and adequate solution of controversies

through arbitration if the parties are

willing to accept less certainty of legally

correct adjustment. On the other hand, it

has enacted the Securities Act to protect

the rights of investors and has forbidden a

waiver of any of those rights. Recognizing

the advantages that prior agreements for

arbitration may provide for the solution of

commercial controversies, we decide that

the intention of Congress concerning the

sale of securities is better carried out by

holding invalid such an agreement for

arbitration of issues arising under the

Act.

346 U.S. at 438 (footnote omitted and emphasis added).

17. The suggestion of Judge Torruella in Lazar v.

[footnote cont’d]

22

2 . Congress' primary purpose in enact

ing the Pees Act was to attract competent

counsel to represent victims of civil rights

violations who otherwise would be unable to

gain access to the courts, and thereby to

provide a mechanism for actual civil rights

enforcement. This overriding goal emerges

clearly from an examination of the legisla

tive history of the Fees Act.-i§/

Pierce, 757 F.2d 435, 439 (1st Cir. 1985), endorsed by

petitioners and their amici — that the statutory fee

entitlement under the Act must be waivable since even

in the criminal sphere, federal constitutional rights

are subject to waiver — is a non sequitur. The issue

is whether the defendant may coerce such a waiver as

the price for agreeing to substantial relief on the

merits. in the criminal area, it is thoroughly set

tled that a prosecutor may not coerce waiver of con

stitutional rights as the price of some other agree

ment with the defendant. E.g,, Blackledge v. Perry,

417 U.S. 21 (1974); North Carolina v. Pearce, 395 U.S.

711 (1969).

18. Despite their broad contentions, petitioners

studiously avoid any examination of the legislative

history, with the exception of four minor and mislead

ing cites to H.R. Rep. No. 1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1976) * See pet‘ Br* at 13. Petitioner's amici

similarly avoid any review of the legislative history.

For example, although the Solicitor General advances a

[footnote cont'd]

23

Running throughout the legislative his

tory, particularly the Reports accompanying

the Fees Act legislationrA2/ are three recur

rent themes. (a) The victims of civil rights

congressional intent argument in his U.S. Br. at 20-

21, nowhere in the argument is there any reference to

the language of the Fees Act or to its accompanying

legislative history.

The overriding importance accorded the legisla

tive history accompanying the Fees Act is illustrated

by, e.g., Pulliam v. Allen, 80 L.Ed.2d 565, 570 & n.4,

580 & n.23 (1984) (relying on the House Report at 9);

Blum v. Stenson, 79 L.Ed.2d 891, 898-900 (1984) (rely

ing on the Senate Report at 6); Hensley v. Eckerhart,

461 U.S. 424, 429-34 & nn.2, 4, 7 (1983) (relying on

the Senate Report at 4, 6; and on the House Report at

1, 7); Maher v. Gagne, 448 U.S. 122, 129, 132 n.15

(1980) (relying on the Senate Report at 5; and on the

House Report at 4 n.7); New York Gaslight Club, Inc,

v. Carey, 447 U.S. 54, 70-71 n.9 (1980) (relying on

the House Report at 5, 8 n.16); Hanrahan v. Hampton

446 U.S. 754, 756-58 (1980) (relying on the Senate

Report at 2, 5; and on the House Report at 4, 7, 8);

Supreme Court of Virginia v. Consumers Union, 446 U.S.

719, 737-39 & n.17 (1980) (relying on the Senate

Report at 4; and on the House Report at 9); Hutto v.

Finney, 437 U.S. 678, 694 n.23 (1978) (relying on the

House Report at 4 n.6).

19. The Senate and House Reports are, respectively:

S. Rep. No. 1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1976) [herein

after "Senate Report"], reprinted in 1976 U.S. Code,

Cong. & Ad. News 5908-14; and H.R. Rep. No. 1558, 94th

Cong., 2d Sess. (1976) [hereinafter "House Report"],

reprinted in E. Larson, Federal Court Awards of Attor

ney' s Fees, 288-312 (1981).

24

violations are ordinarily unable to afford

lawyers, and are thus ordinarily unable to

gain access to the courts. (b) Effective

civil rights enforcement depends upon actions

initiated by private plaintiffs and thus

depends upon encouraging private lawyers,

through the availability of court-awarded

attorneys fees, to represent plaintiffs in

private suits. (c) For these reasons, fee

awards are essential if our Nation's civil

rights statutes are to be enforced.

a. The Senate Report at 2 recog

nized at the outset that in "many cases aris

ing under our civil rights laws, the citizen

who must sue to enforce the law has little or

no money with which to hire a lawyer." This

lack of financial resources, coupled with

this Court's rejection of the "private attor

ney general" doctrine in Alyeska Pipeline

Service Corp. v. Wilderness Society, 421 U.S.

240 (1975), effectively precluded access to

25

the courts. The House Report at 2 made clear

that "civil rights litigants were suffering

very severe hardships because of the Alyeska

decision." " [P]rivate lawyers were refusing

to take certain types of civil rights cases,"

and civil rights organizations, "already

short of resources, could not afford to do

so" either. Id. at 3. For victims of civil

rights violations, the situation was indeed

bleak: "Because a vast majority of the vic

tims of civil rights violations cannot afford

legal counsel, they are unable to present

their cases to courts." Id. at 1.

Congress responded by authorizing court-

awarded fees as a financial incentive to

attract counsel to represent persons whose

rights had been violated. "In authorizing an

award of reasonable attorney's fees [the Fees

Act] is designed to give such persons effec

tive access to the judicial process where

their grievances can be resolved according to

26

law." House Report at 1. "This bill ...

provides the fee awards which are necessary

if citizens are to be able to effectively

secure compliance with these existing [civil

rights] statutes." Senate Report at 6.

b. Congress thoroughly understood

that most of our "civil rights laws depend

heavily upon private enforcement," Senate

Report at 2, for the obvious reason that

"there are very few provisions in our Federal

laws which are self-executing." Id. at 6.

"The effective enforcement of Federal civil

rights statutes depends largely on the ef

forts of private citizens." House Report at

1. In creating the incentive of fee awards

to facilitate the functioning of the enforce

ment mechanism, Congress made "fees ... an

integral part of the remedy necessary to

achieve compliance with our statutory [civil

rights] policies." Senate Report at 3.

Congress did so consciously and

27

purposefully. It was aware of Hall v. Cole,

412 U.S. 1 , 13 ( 1973 ) , in which this Court

endorsed a fee award in a union member's suit

to enforce the Landrum-Griffin Act because:

"Not to award counsel fees in cases such as

this would be tantamount to repealing the Act

itself by frustrating its basic purpose."

Senate Report at 3. Similarly, both Reports

quoted from this Court's decision in Newman

v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S.

400, 402 (1968): "If successful plaintiffs

were routinely forced to bear their own

attorneys' fees, few aggrieved parties would

be in a position to advance the public

interest by invoking the injunctive powers of

the Federal courts." Senate Report at 3;

House Report at 6. Finally, the legislative

history demonstrates that Congress reviewed

the enforcement success achieved through fee-

shifting provisions in other civil rights

statutes: "These fee-shifting provisions

28

have been successful in enabling vigorous

enforcement of modern civil rights

legislation." Senate Report at 4.

c. The legislative history leaves

no doubt that Congress believed fee awards to

be essential both to secure future legal

representation for aggrieved individuals and

to create an ongoing mechanism for civil

rights enforcement in general. As summarized

in the Senate Report:

"tC]ivil rights laws depend heavily

upon private enforcement, and fee

awards have proved an essential

remedy if private citizens are to

have a meaningful opportunity to

vindicate the important Congres

sional policies which these laws

contain."

Id. at 2 (emphasis added); "fee awards are

essential if the Federal statutes to which

[the Fees Act] applies are to be fully en

forced," id. at 5 (emphasis added); fee

awards "are necessary if citizens are to be

able to effectively secure compliance with

these existing statutes," id. at 6 (emphasis

29

added); "[i]f our civil rights laws are not

to become mere hollow pronouncements which

the average citizen cannot enforce, we must

maintain the traditionally effective remedy

of fee shifting in these cases," id. (empha

sis added).

In sum, Congress enacted the Fees Act to

"insure that reasonable fees are awarded to

attract competent counsel in cases involving

civil and constitutional rights," and thereby

"to promote the enforcement of the Federal

civil rights acts, as Congress intended."

House Report at 9.

3. It is also evident that Congress

intended to make fee awards available to

counsel who further private enforcement of

national civil rights laws by successful

resolution of lawsuits through settlement

rather than formal adjudication.

30

The Fees Act "by its terms ... permits

the award of attorney's fees only to a 'pre

vailing party.'" Hanrahan v. Hampton, 446

U.S. 754, 756 (1980). Giving meaning to this

statutory phrase, the legislative history

demonstrates Congress' intent to make fee

awards available after a party "prevails"

through settlement as well as through trial.

The House Report at 7 states:

The phrase 'prevailing party'

is not intended to be limited to

the victor only after entry of a

final judgment following a full

trial on the merits. It would also

include a litigant who succeeds

even if the case is concluded prior

to a full evidentiary hearing be

fore a judge or jury. If the liti

gation terminates by consent

decree, for example, it would be

proper to award counsel fees.

Incarcerated Men of Allen County v.

Fair, 507 F.2d 281 (6th Cir. 1974);

Parker v. Matthews, 411 F. Supp.

1059 (D.D.C. 1976); Aspira [sic] of

New York, Inc, v. Board of Educa

tion of the City of New York, 65

F.R.D. 541 (S.D.N.Y. 1975). A

"prevailing" party should not be

penalized for seeking an out-of-

court settlement, thus helping to

lessen docket congestion.

31

By equating success through settlement or a

consent decree with success through judgment

following a full trial, and particularly by

emphasizing that a prevailing party should

not be penalized by a denial of fees for

seeking an out-of-court settlement, Congress

certainly did not intend to diminish statu

tory fee entitlement, much less obliterate

it. Congress instead meant nothing less than

what it said: fee entitlement follows the

achievement of prevailing party status won

through settlement or a consent d e c r e e ^

20. The three cases relied on in the House Report at

7 further illustrate Congress' intent. In two of the

cases, the consent decrees addressed and resolved the

merits of the litigation without any reference to

attorneys fees. Incarcerated Men of Allen County v.

Fair, 507 F.2d 281 (6th Cir. 1974), aff'g 376 F. Supp.

483 (N.D. Ohio 1973); ASPIRA of New York, Inc, v.

Board of Education of the City of New York, 65 F.R.D.

541 (S.D.N.Y. 1975). The consent decree in the third

case reserved the fee issue for later resolution by

the court. Parker v. Matthews, 411 F. Supp. 1059

(D.D.C. 1976), aff*d sub nom., Parker v. Califano, 561

F.2d 320 (D.C. Cir. 1977). Significantly, in all

three cases, fee entitlement was held to flow from the

fact, and after the fact, of the plaintiffs having

achieved prevailing party status.

32

The Senate Report, albeit less elabo

rately, confirms this interpretation. After

noting that fee awards are "appropriate where

a party has prevailed on an important matter

in the course of litigation," the Senate

Report at 5 further states: "Moreover, for

purposes of the award of counsel fees, par

ties may be considered to have prevailed when

they vindicate rights through a consent judg

ment or without formally obtaining relief."

Once again, according to Congress, a plain

tiff's achievement of prevailing party status

means that fee entitlement follows.

4. This basic congressional intent was

recognized by this Court in Maher v. Gagne,

448 U.S. 122 , 129 (1980), where the Court

held that the "fact that [plaintiff] pre

vailed through a settlement rather than

through litigation does not weaken her claim

to fees." The Court further observed:

33

Nothing in the language of § 1988

conditions the District Court's

power to award fees on full litiga

tion of the issues or on a judicial

determination that the plaintiff's

rights have been violated. More

over, the Senate Report expressly

stated that "for purposes of the

award of counsel fees, parties may

be considered to have prevailed

when they vindicate rights through

a consent judgment or without for

mally obtaining relief." S. Rep.

No. 94-1011, p.* 5 ( 1976) .

Id. See also Hanrahan v. Hampton, 446 U.S.

at 756-57 (quoting with approval the House

and Senate Reports) . And in White v. New

Hampshire Department of Employment Security,

455 U.S. 445 ( 1982), the Court held that a

post-consent decree fee motion was not a Fed.

R. Civ. P. Rule 59(e) motion to alter or

amend a judgment on the merits because § 1988

"provides for awards of attorney's fees only

to a 'prevailing party,'" id. at 451, fee

entitlement "under § 1988 raises issues col

lateral to the main cause of action," id.

(footnote omitted), and any "decision of

entitlement to fees will therefore require an

34

inquiry separate from the decision on the

merits — an inquiry that cannot even com

mence until one party has prevailed," _id_. at

451- 52 .-^1/

21 . Also in whi te, as petitioners and their amici

here are fond of pointing out, this Court "decline[d]

to rely on" plaintiff's alternative "reason for find

ing Rule 59(e) inapplicable to post-judgment fee

requests": that "prejudgment fee negotiations could

raise an inherent conflict of interest between the

attorney and client," and that "to avoid this conflict

of interest any fee negotiations should routinely be

deferred until after the entry of a merits judgment."

Id. at 453-54 n.15. Apart from the fact that resolu

tion of this alternative argument was no longer neces

sary in view of this Court's favorable ruling for

plaintiff-petitioner on the meaning of Rule 59(e)

given that fee entitlement is "collateral to the main

cause of action," id. at 451, the fact of the matter

is that this Court, in a footnote, "decline[d]" to

rule on this simulatenous negotiation argument, and in

fact said little more than that a defendant deciding

whether to settle a case on the merits "may have good

reason to demand to know his total liability from both

damages and fees":

Although sensitive to the concern that

petitioner raises, we decline to rely on

this proffered basis. in considering

whether to enter a negotiated settlement, a

defendant may have good reason to demand to

know his total liability from both damages

and fees. Although such situations may

raise difficult ethical issues for a plain

tiff's attorney, we are reluctant to hold

that no resolution is ever available to

ethical counsel.

Id. at 453-54 n.15. This is far from any endorsement

[footnote cont'd]

35

Thus, under the statutory scheme, fee

entitlement follows from the precondition of

achieving prevailing party status through

trial or settlement. Petitioners' tactic of

demanding a fee waiver as the price for the

defendant's execution of a settlement agree

ment on the merits, which establishes a

plaintiff's prevailing party status, thus

turns the law on its head.-H/ Judicial ap-

of petitoner's request here for judicial approval of a

coerced waiver of fees altogether, a situation not

presented in White.

22. Petitioners' suggestion that Congress enacted the

Fees Act cognizant of federal court decisions that

"had interpreted Title II and VII to allow [defendants

to coerce] plaintiffs to waive attorney's fees" and

intended to incorporate "this judicial gloss on the

parallel statutes" into the Fees Act, Pet. Br. at 13,

is unsupportable. Congress directed attention speci

fically to "existing judicial standards, to which

ample reference is made in this report," House Report

at 8 (emphasis added); and Congress illustrated those

standards by directing that fees be awarded where

plaintiffs prevail through settlements or consent

decrees, House Report at 7 and Senate Report at 5, see

supra at 31-35. Cf. Cannon v. University of Chicago,

441 U.S. 677, 696-97 (1979).

In any event, the two pre-Fees Act cases cited by

petitioners do not concern waiver at all. One gave

simultaneous approval of settlements of the merits and

fees, without indicating whether both subjects were

[footnote cont'd]

36

proval of petitioners' approach would have

the undeniable effect of removing fee enti

tlement from virtually all cases where plain

tiffs prevail through settlements or consent

decrees.-M/ This, however, would be directly

contrary to Congress’ injunction that a

"'prevailing' party should not be penalized

for seeking an out-of-court settlement."

House Report at 7. And, contrary to Con

gress' directions, it would eliminate fee

entitlement from a large category of cases in

which Congress intended fees to be awarded.

discussed in the same negotiations, and without any

mention of a fee waiver. Leisner v. New York Telephone

Co., 398 F. Supp. 1140, 1142 (S.D.N.Y. 1974) ("Defen

dant has admitted nothing in terms of liability but

has agreed to a compromise guaranteeing substantially

all the affirmative relief sought by plaintiffs, and

further agreed under 'll.A.' to 'payments ... to

Plaintiffs and their Attorneys ...'") (emphasis added

in part). in the other case, Clanton v. Allied Chemi

cal Corporation, 459 F. Supp. 282 (E.D. Va. 1976), the

settlement agreement provided not for a fee waiver but

for the court to determine fee entitlement. Id. In

deed, all of the pre-Fees Act cases cited, see House

Report at 7, involved bifurcated negotiations with the

Court determining the fee, as in Clanton.

23. See supra note 14 and accompanying text.

37

Thus, not only is the position of peti

tioners and their amici not supported by the

express purposes of the Fees Act, it is di

rectly contrary thereto. It is consistent,

however, with the persistent and unsuccessful

efforts of the Department of Justice, the

National Association of Attorneys General,

and other government representatives to con

vince Congress to amend the Fees Act to limit

drastically the availability of attorneys

fees against government agencies .2 A J To

date, they have been unable to get a bill out

of committee in either house

24. See e.g., Attorney's Fees Awards: Hearings on s.

585 Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the

Senate Comm, on the Judiciary, 97th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1982); Municipal Liability Under 42 U.S.C. § 1983:

Hearings on S. 585 Before the Subcomm. on the Consti

tution of the Senate Comm, on the Judiciary, 97th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1981).

25. The latest effort to limit drastically fee awards

against government agencies is legislation entitled

the "Legal Fees Equity Act," which was drafted by the

Justice Department and which was introduced in the

98th Cong., 2d Sess. (1984) as S. 2802 and H.R. 5757.

Hearings were held only on the Senate bill, Legal Fees

Equity Act; Hearings on S« 2802 Before the Subcomm.

[footnote cont'd]

38

The present case is but the latest in a

series of equally unsuccessful government

efforts^/ to have this Court interpret the

Fees Act in such a way as to cripple private

civil rights enforcement.

C. Enforcement of Congress' Intent, by

Barring Coerced Fee Waivers, Will

Not Discourage Settlements or Make

More Difficult the Quick Disposi

tion of Nuisance Suits

Notwithstanding Congress' clearly ex

pressed purposes in enacting the Fees Act,

petitioners and their amici argue strenuously

that restricting the ability of defense coun-

on the Constitution of the Senate Comm, on the Judi

ciary, 98th Cong., 2d Sess. (1984), but the bill was

not even voted out of subcommittee.

This same legislation was recently reintroduced

as S. 1580, 99th Cong., 1st Sess. (1985); see 131

Cong. Rec. S10876 (daily ed. Aug. 1 , 1985). The

section-by-section analysis states that this new bill

is not "intended to preclude discussions between the

parties of attorneys fees, or the waiver thereof,

before the decision on the merits ... or to prevent

the government from discussing liability for attor

neys' fees in conjunction with liability on the merits

as part of a settlement agreement." Id. at S10881.

26. See, e.g., Blum v. Stenson, and the U.S. Br.

therein; Hutto v, Finney.

39

sel to press for fee waivers as part of over

all settlements will have dire consequences

for our judicial system, defeating salutary

policies favoring compromise and settlement

of litigation and burdening the courts with

frivolous, "nuisance" litigation. These

assertions are devoid of merit.

1. As to settlements in general, it is

an historical fact that counsel in many earl

ier civil rights cases followed a bifurcated

approach, settling the merits first and

thereafter resolving the matter of fees.

This is precisely what occurred in the three

settled cases cited with approval in the

House Report at 7.2JJ it also is what

occurred in Maher v. Gagne 448 U.S. 122, 126

(1980) (the "parties informally agreed that

the question whether [plaintiff] was entitled

to recover attorney's fees would be submitted

27. See supra note 20 and accompanying text.

40

to the District Court after entry of the

consent decree"); in White v. New Hampshire

Department of Employment Security, 455 U.S.

445, 447-48 (1982) (the parties first nego

tiated a settlement, and thereafter sought to

negotiate fees, with the district court ulti

mately awarding fees) ; and in hundreds of

other civil rights cases including Nadeau v.

Helgemoe, 581 F.2d 275 (1st Cir. 1978), cited

with approval in Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461

U.S. 424, 433 (1983).

Even more compelling is the fact that

court orders barring defense counsel from

conditioning an offer of settlement upon a

coerced waiver of fees have not deterred

settlement. For example, in Lisa- F. v.

Snider, 561 F. Supp. 724 (N.D. Ind. 1983 )

(Civ. No. S-79-103), where the government

defendants, after four years of litigation,

proposed a settlement on the merits condi

tioned upon a coerced waiver of fees, and

41

where the court ordered any negotiation on

the merits to be conducted "separate from the

question of the plaintiff's entitlement to

attorney fees," id. at 726, this order did

not deter settlement. Less than six months

later, the parties settled the case on the

merits favorably to the plaintiff. Order of

September 15, 1983. Thereafter, fee negotia

tions commenced, no agreement on fees was

reached, the matter was submitted to the

district court, and the court ultimately

awarded fees to plaintiff's counsel. Order

of February 8, 1985.-2^/

28. Similar results have occurred in many other

cases. For example, the same private attorney who

represented the plaintiff in Lisa F. represented the

plaintiffs in another § 1983 class action, Ellison v.

Schilling, Civ. No. l-80-23 (N.D. Ind. consent decree

entered on July 11, 1983), a case in which another set

of government defendants sought a coerced waiver of

fees from this private attorney after nearly three

years of litigation. Plaintiffs immediately there

after filed a motion seeking an order barring simulta

neous negotiation; the district court granted plain

tiffs' motion in an unreported order filed on April 6,

1983; the parties then negotiated a settlement on the

merits favorable to plaintiffs, and the court approved

the consent decree on July 11, 1983; following unsuc-

[footnote cont'd]

42

Rather than deterring settlement, the

certainty of defendants' liability for fees

in meritorious cases not only provides a

powerful incentive for defense counsel to

assess the strength of a case early and to

settle, cf. Marek v. Chesny, 53 U.S.L.W. at

4904, but also serves to deter potential

wrongdoers from violating the law in the

first place. These principles were repeated

ly enunciated by the courts of appeals that

ruled, prior to this Court's decision in Blum

v. Stenson, 104 S.Ct. 1541, 79 L.Ed.2d 891

(1984), that legal 'aid organizations were

entitled to fee awards computed on the same

basis as those for private counsel. As

stated by the en banc court of appeals in

Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F.2d 880 (D.C. Cir.

1980), if market fees could not be awarded

when "a public interest law firm serves as

cessful settlement negotiations as to fees, the court

awarded fees to plaintiffs' attorney on April 10,

1985.

43

plaintiff's counsel," then

the defendant will be subject to a

lesser incentive to settle a suit

without litigation than would be

the case if a high-priced private

firm undertook plaintiff's repre

sentation. That is so because the

marginal cost of each hour of con

tinued litgation would be reduced.

Defendant's counsel could inundate

the plaintiff with discovery re

quests without fear of paying the

full value of the legal resources

wasted in response. We do not

think that Title VII intended that

defendants should have an incentive

to litigate imprudently.

Id. at 899 (citation omitted). Additionally,

the "incentive to employers not to discrimi

nate is reduced if diminished fee awards are

assessed." Id. See also, e.g. , Oldham v.

Ehrlich, 617 F. 2d 163, 168 (8th Cir. 1980)

(with the focus "on deterring misconduct by

imposing a monetary burden on the wrongdoer,

a legal aid organization merits an attorney's

fee fully as much as does the private attor

ney") ; Dennis v. Chang, 611 F.2d 1302, 1306

(9th Cir. 1980) (a full fee "award encourages

potential defendants to comply with civil

44

rights statutes"). As the Ninth Circuit also

correctly observed in Dennis, 611 F.2d at

1307: "if the state could immunize itself

against a fee award . . „ the state would have

less incentive to settle pending litigation

and more incentive to resist civil rights

compliance by defending against the suit

until trial."

2. Just as a rule barring coerced fee

waivers will not deter settlement of meritor

ious cases, neither will such a rule

whether through a Lisa F. order or otherwise

— deter settlement or early disposition of

frivolous cases or nuisance suits. In deal

ing with these suits, defense counsel in fact

possess a considerable array of permissible

tactics provided by federal rules and sta

tutes .

45

Where a matter truly is frivolous at the

outset as a matter of law, defense counsel

may quickly have the case resolved under Fed.

R. Civ. P. Rule 12(b) by filing a dispositive

motion to dismiss or for judgment on the

pleadings. Alternatively, where defense

counsel choose to address matters outside of

the pleadings, they may quickly have the

frivolous case resolved under Fed. R. Civ. P.

Rule 56 by filing a dispositive motion for

summary judgment. In either event, defense

counsel may seek and obtain an award of

attorneys fees from plaintiffs so long as the

case was in fact frivolous. Christiansburq

Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434 U.S. 412, 422

(1978). These fee awards, which are often

substantial pose a strong deterrent to

29. See, e.g,, American Family Life Assurance Company

v. Teasdale, 733 F.2d 559 (8th Cir. 1984) (fee award

of $63,000 assessed against plaintiff under § 1988);

Arnold v. Burger King Corp., 719 F.2d 63 (4th Cir.

1983) (fee award of more than $10,000 assessed against

plaintiff under Title VII); Charves v. Western Union

Telegraph Company, 711 F.2d 462 (1st Cir. 1983) (fee

[footnote cont'd]

46

frivolous litigation. And, as if additional

tools were needed to deter nuisance litiga

tion, fees may always be assessed against

counsel personally for bad faith litigation,

Roadway Express, Inc, v. Piper, 447 U.S. 752

( 1980), and fees now may also be assessed

against counsel under Fed. R. Civ. P. Rule 11

for frivolous litigation.-12/

3. Given this arsenal of procedural

devices available both to dispose of truly

frivolous cases and to obtain compensation

for defending them, it is apparent that de-

30. Defense counsel also have available yet another

permissible tactic: they are free to make an early

offer of judgment under Fed. R. Civ. P. Rule 68 with

out specifically including a fee component. If the

offer is accepted, the available attorneys fees will

be small, Hensley v, Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424 (1983),

and may even be unavailable altogether, Pigeaud v.

McLaren, 699 F.2d 401 (7th Cir. 1983). If the offer

is unreasonably rejected and the plaintiff fails to

secure a superior result, no fees would be available

from the date of the offer, Marek v. Chesny, 53

U.S.L.W. 4903 (U.S. June 27, 1985), and the available

fees again would be small, Hensley.

47

fense counsel's concern is not the frivolous

case but the meritorious case. For example,

in a meritorious case recently brought by

amicus Legal Aid Society of New York against

the City of New York — and contrary to the

impression conveyed to this Court in its

Brief in this case — the City declined a

prelawsuit settlement, waited until the eve

of trial to invoke its policy of offering a

settlement conditioned upon a total waiver of

fees, and ultimately was held liable after

trial for greater relief and for fees.-^i/ In

31 . This chronology occurred in Henry v. Gross, 84

Civ. 8399 (TPG) (S.D.N.Y. June 18, 1985) notice of

appeal filed, (2d Cir. July 18, 1985). Two months

before the suit was filed, Legal Aid lawyers, pursuant

to established Legal Aid policy (similar to the policy

required of all grantees of the federal Legal Services

Corporation), sent the New York City Department of

Social Services a letter describing the claims by a

class of welfare recipients of improper termination of

benefits without hearings, and inviting the City to

take voluntary remedial action. This of course gave

the City ample opportunity "as a matter of policy or

practical judgment ... to dispose of the matter [with

a] ... substantial reduction of attorneys' fees." Br.

for City of New York at 11. Nevertheless, the Depart

ment of Social Services rebuffed this attempt, and

suit was thus filed. Some four-and-a-half months

[footnote cont'd]

48

fact, in amici1s experience, it is precisely

in meritorious cases in which plaintiffs'

claims on the merits are strong that the use

of coerced fee waivers is most p r e v a l e n t /

later, after discovery and after motions for class

certification and for a preliminary injunction had

been filed, and on the eve of a trial, the City made

an incomplete merits settlement offer which was

somewhat favorable on the merits but conditioned upon

a complete waiver of fees under § 1988. Despite the

trial court's oral suggestions to the City that this

negotiating tactic was improper, the City refused to

negotiate separately and decided to risk going to

trial rather than agree to pay reasonable fees. After

a three-day trial, the trial court awarded plaintiffs

sweeping relief on the merits — relief substantially

more favorable than that proposed in the City's with

drawn settlement offer — - and the court also assessed

fees against the City.

This is not an isolated example. Amicus Legal

Aid Society of New York has in other meritorious cases

been confronted with New York City's practice of seek

ing coerced fee waivers, ordinarily after substantial

litigation has taken place, and usually on the eve of

trial.

32. While at first blush it might seem that offers of

substantial merits relief in exchange for fee waivers

would only be made in weak cases, the opposite is

true. Unlike ordinary commercial or tort litigation,

or even individual Title VII cases, weak class action

cases under § 1983 are rarely settled; the government

agency usually prefers to fight the case on the merits

rather than restructure its operations. It often de

cides that the costs of litigation, conducted by staff

counsel and assisted by paid employees in the affected

agency, are lower than the costs of structured relief,

[footnote cont'd]

49

Since this case is neither frivolous nor

a nuisance suit but rather a substantial case

involving a wholly illegitimate effort by

petitioners to evade fee liability imposed by

statute, approval by this Court of the tactic

followed by petitioners in seeking a coerced

waiver of all fees in this case would neces

sarily allow all defense counsel to extract

coerced fee waivers in all settlements, and

it would thus eliminate the very incentive

provided by Congress for enforcement of and

compliance with our civil right laws.

It is thus in the strong cases that waiver de

mands from governmental entities are most common.

Facing long-term, structual relief after substantial

litigation, defendants in these cases are most eager

to reduce their costs by limiting what they know will

be a large attorneys fee bill. Accordingly, just

prior to trial they will often offer some relief on

the merits contingent on a fee waiver. This behavior

is often reinforced by attitudes about local autonomy

and resistance to "outside do-gooders" that make

anathema the idea of liability for the plaintiffs'

attorneys fees. The result is that it is precisely in

the cases where plaintiffs are most likely to prevail

that fees waiver requests are most common.