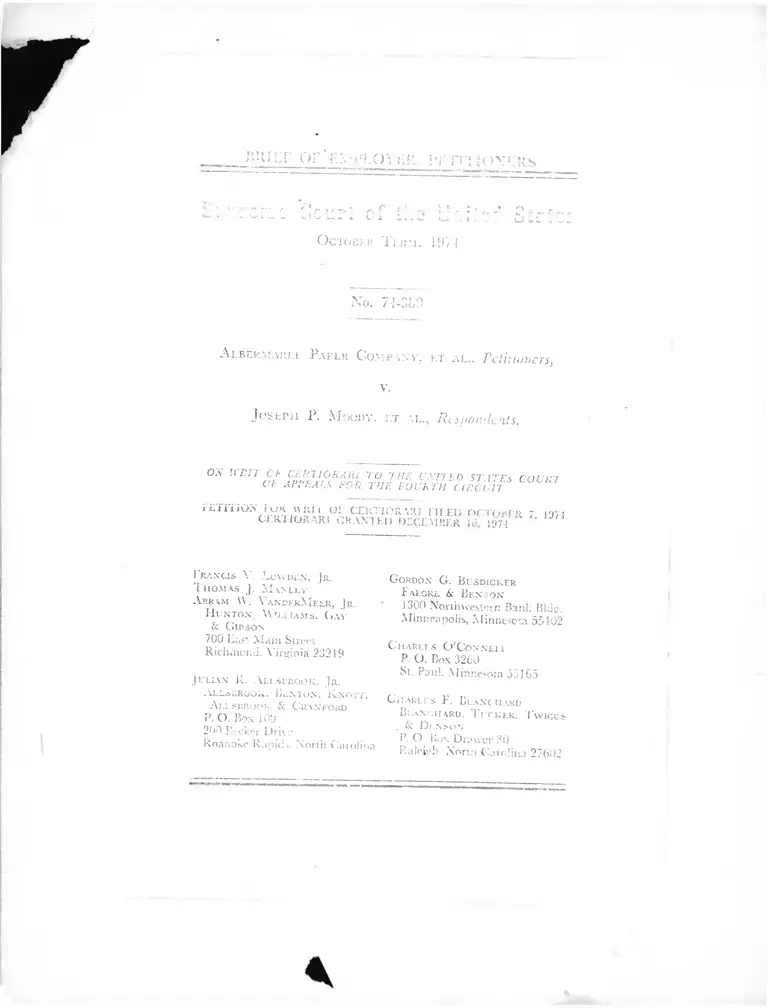

Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody Petition for Writ of Certiorari Filed October 7, 1974 and Certiorari Granted December 16, 1974

Public Court Documents

February 13, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody Petition for Writ of Certiorari Filed October 7, 1974 and Certiorari Granted December 16, 1974, 1975. dc9a6461-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8751c668-5842-40b5-9252-22e6e24f9b0f/albemarle-paper-company-v-moody-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-filed-october-7-1974-and-certiorari-granted-december-16-1974. Accessed February 02, 2026.

Copied!

ISRIKr O r 'l :A M ^LO^j^_jj- r r i? o y j .R S

■ V't r* —v

> U C l j j r '~ * ] r. ? r T. * A p f • l ? ;- * * ^ Q -:• ^ .'• ^_ o t -„„ k v i t u S L i.;,» *6;.: b t c i ,-G 3

O ctober T erm . 1970

No. 74-389

A l b e r m a r u P a p e r C o m p a n y , k t a l „ Petitioners,

v.

JosEDi P. M oody, e t ai.., Respondents.

Oa u m C l- CERl i o r a r i t o THE UNITED S T iTFS C'OUTT

O f APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

rilTiTiON FOk n u n O! CERTIOR \ju n r ri) f i r m i r p -

CERTIORARI GRANTED DECEMMER 1974 * 19/4

I 'rancis V. Lowden, ]a.

T hom a s j . M anley

A bram W. Vandf.rM eer , Jr .

H u n t o .v . V teeia m s. G ay

& G ibson

700 East Main Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

J ulian R. A llserook , J r .

.allser o o k . Re n to n . K.nott .

Allsbrook & C ranford

P. O. Box 100

200 Becker Drive

Roanoke Rapids. North Caioiina

G ordon G. B u s d ic k e r

F aegre & B e n s o n

1300 Northwestern Bank Hleio.

-Minneapolis, Minnesota 55402

C h a r l e s O ’C o n n e u

P. O. Box 3260

St. Paul. Minnesota 55365

C h a r les F . B la n c h a r d

B la n c h a r d , T u c k e r . T w ig g s

. oC D i.NsON

P. O Bom Drawer 30

Raleigh. N'ortn CanC.na 27602

l

*

INDEX

Page.

I. O p in io n s B e l o w ................. .......... .................. ................................ ........ ]

II. J u r is d ic t io n ............................. ........................................................ .......... \

III. St a t u t e s A n d R e g u l a t io n s I n v o l v e d .............. ............... ........... ]

IV . Q u e s t io n s P r e s e n t e d F or R e v i e w ________________ ____ .... 3

V . St a t e m e n t O f T h e C a s e .................. ....... .......................................... 4

VI. S u m m a r y O f A r g u m e n t _____________ _____ _______________ 23

VII. A r g u m e n t

A. The District Court Correctly Refused To Enjoin The

Use Of Albemarle’s Testing Procedures._____________27

1. Introduction__________________________________ 27

2. The Evidence In Tills Case Sliows Albemarle’s Tests

Were Not Discriminatory._____________________ 28

3. Albemarle Demonstrated Its Tests To Be A Reason

able Measure Of Job Performance.________________32

(a) Defendants’ Tests Were Found To Be Job Related

By The District Court.________________________32

(b) The Findings Of The District Court Have Not

Been Shown To Be Erroneous._______________34

(i) Job Analysis______ ___________________36

(51) Supervisors’ R atings_______________ ,__ 39

(in) Business Necessity'______________ ;______ 43

B. In Any Event The.Court Of Appeals Erred In Not

Remanding The Issue To The District Court.________47

i

Page

C. The District Court Had Traditional Equitable Discretion

To Determine Whether Back Pay Was An Appropriate

Remedy.................................. .................................... 59

1. Title VII Leaves I he Award Or Denial Of Back Pay

To The General Equitable Discretion Of The Dis

trict Courts..................................................................... 50

2. The Discretion Of A District Court Regarding The

Back Pay Remedy Should Be Guided By Traditional

Equitable Principles......................................................... 55

3. Even Under A “Special Circumstances” Standard, The

District Court Was Justified In Denying Back Pay..... 61

D. Back Pay Should Not Be Awarded To Class Members

W ho Did i\ot Pile Charges With The Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission.................. ............. .....................' g]

VIII. C o n c l u s io n ........;............................................................................. _ 57

1. Affirm The District Court.............................................._ 57

2. Reverse The Court Of Appeals And Remand To The

District Court For Further Proceedings........................ 67

TABLE OF c i t a t i o n s

Cases' : .. _.

Page

Austin v. Reynolds Metals Co.. 327 F.Supp. 1145 (E.D. Va. 1970) 64

Barlow v. Collins, 397 U.S. 159 (1970) 35

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp., 495 F.2d 436 (5'th. Cir.

" 1974), cert,denied, ...... UjS. Z : , « tJiSX.Wl 3306- (U.S.,

Nov. 26, 1974) 57

Boston Chapter, NAACP v. Beecher, 504 F.2d 1017 (1st Cir. 1974) 37

Rowe v. Colgate Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711 (7th Cir. i969) ..54, 62

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Civil 'Sen-Ice Commission, 482 F.2d

1333 (2nd Cir. 1973) .................................................•'....... 23> 24> 28

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.'2d '315 (8th Cir.), cert, denied, 406

u .s . 950 (1972) -28

Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.‘2d 725 (lst'Cir. 1972) 34

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 330 F.Supp. 2C3 (S.D. N.Y. 1971) .. 31

Commissioner v. Duberstein, 363 U.S. 278 (1960) .......... -.............. 50

Cojc Vf United States Gypsum, 284 F.Supp. 74 (N.D. Irid. 1968),_

afl’d., 409 F~2d 289 (7 th^ ir.'i969)

Curtis v. Loether, 415 U.S. 189 (1974) ....................................... 26, 53

^Dent v. St. Louis & S .F . Ry. Co.,^406 F!2d 399 (Sth^'Cir. 1969) ":../ 65

Duhon v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 494 K2d 81/ (5th Cir. ̂

1974) ---- 51

England v. Louisiana Medical Examiners,' 375 "U.S. 411 (1964)

b z 2 5 / 4 8

Espinoza v. Farah Manufacturing Co., 414 U.S. 86 (1973) ....24, 36

Fishgold v. Sullivan Dry dock and 'Repair Corp., 328 U.S. 275^

(1973) ^ IZ ^ Z Z Z Z Z ^ Z Z Z X X X X :::: :: :: :: : ::^ :: :: :: : ;: :: : . .: 35

m

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d 398 (5th Cir.

1974), cert, denied, ..... U.S........ , 43 U.S.L.W. 3330 (U.S.

Dec. 10, 1974) ............... ................................................................ 62

Griffin v. Pacific Maritime Ass’n., 478 F.2d 1118 (9th Cir.), cert,

denied, 414 U.S. 859 (1973) .......................................................... 65

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 410 U.S. 424 (1971) ....18, 23, 27, 31, 32,

33, 34, 35, 53, 57 •

Guardians Ass’n v. Civil Service Commission, 490 F.2d 400 (2nd

Cir. 1973) ....................................................................................... 34

Harper v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 359 F.Supp.

1187 (D. Md.), modified sub noin. Harper v. Kloster, 486

F.2d 1134 (4th Cir. 1973) .......................................................... 31

Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., 486 F.2d S70 (6th Cir. 1973)

51, 53, 57, 62

Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321 U.S. 321 (1944) ..................................... 53

Hester v. Southern Railway Co., 497 F.2d 1374 (5th Cir. 1974)

23, 28

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 417 P’.2d 1122 (5th Cir.

1969) ..._................................................... 56

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364 (5th

Cir. 1974) ..!......................................................................... ..... 57, 62

Kirkland v. Department of Correctional Services, 374 F.Supp.

1361 (S.D. N.Y. 1974) .............. :.................................................... 40

Kober v. Westinghouse Electric Co., 480 F.2d 240 (3rd Cir. 1973)

26, 54, 56, 61

LeBIanc v. Southern Bell Telephone and Telegraph Co., 460 F.2d

1228 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 990 (1972) ........... 54, 56

Manning v. General Motors Corp., 466 F.2d 812 (6th Cir. 1972) 54

Mayor v. Educational Equality League, 415 U.S. 605 (1974) ....23, 31

Page

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973)

23, 24, 25, 26, 28, 43, 48, 65

Newman v. Piggy Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968)..54, 63

NLRB v. Boeing Co., 412 U.S. 67 (1973) ............................... ....... 35

Norman v. Missouri Pac. Ry. Co., 497 F.2d 596 (8th Cir. 1974),

cert, denied,.... U.S..... , 43 U.S.L.W. 3433 (U.S. Jan. 28, 1975) 56

Parmer v. National Cash. Register Co.. 503 F.2d 275 (6th Cir

1975) ..................................................., ...._...._................ 43

Pennsylvania v. Glickman, 370 F.Supp. 724 (W.D. Pa. 1974) .... 41

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211 (5th Cir.

1974) ................................................ ................... ;..............51, 52, 57

Phelps Dodge v. NLRB, 313 U.S. 177 (1941) ................................. 52

Porter v. Warner Holding Co., 328 U.S. 395 (1946) ............ ......... 60

Quarles v. Phiiip Morris, 279 F.Supp. 505 (E.D. Va. 1968) __ 14, 15

Rental Development Corp. of America v. Laver)', 304 F.2d 839

9th Cir. 1962) ............ _......................... ....................................26, 59

Richardson v. Miller, 446 F.2d 1247 (3rd Cir. 1971) ............ ..... ,. 65

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir.), petition for

cert, dismissed 404 U.S. 1006 (1971) .... ................................ 59 ̂ 61

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp'., 319 F.Supp. 853 (M.D. N.C. 1970).. 18

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir. 1972) ___ 40

Schaeffer v. San Diego Yellow Cabs, Inc., 462 F.2d 1002 (9th Cir.

1972) ...— ......... ................. ............................... .......................54, 56

Shultz v. Mistletoe Express Service, Inc., 434 F.2d 1267 (10th Cir. .

Snyder v. Harris, 394 U.S. 332 (1969) ........ .......................27, 62, 66

Sperberg v. Firestone Tire & Rubber Co., 61 F.R.D. 70 (N.D.

Ohio 1973) ................................ .................... ...........................27, 66

v

Page

Ste,;b- V- Nati0n'vide Mutual Ins- Co-> 382 F-2d 267 (4th Cir 1967), cert, denied, 390 U.S. 910 (1968) ................ ‘ g5

SteA k 01972)Internati0nal ^ C°” 352 F‘SuPP- 238 (S.D.

‘ .................... ....... ................... - ................................. 38

Untied States v. Dillon Supply Co., 429 F.2d 800 (4th Cir. 1970) .. 56

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906 (5th Cir. 1973)

24, 25, 26, 28, 31, 34, 48, 55

United States v. Local 189, Papermakers Union, 301 F.Sttpp. 906

S u . s l l ^ . t o , 6 K‘2d 980 (5th CIr- ,969)-

' .................................... —....................... 15

United States v. N.L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354 (8th Cir. 1973)

53, 57, 60

United States v. St. Louis & S.F. Ry. Co., 464 F.2d 301 (8th Cir

U72), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1107............ ........ gg ^ •

United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333 U.S. 364 (1948).. 43

VUChn 1973? V‘ CiVi' SerVke Comir‘ission> 433 U2d 387 (2d

' .......................... ................................................ 24, 35, 37

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works, 502 F.2d 1309 (7th Cir. 1974) 57

Wai ? nS,Vo i COtt PapSr C°->..... R 2 d ..... 6 FEP Cases 511 (S D

' ...... ...................................... - ............... - ...........33, 39

'^1973? °f K'nS °f 358 F-Supp- 684 (ED- Pa-

............... ....... ....................................... ~......- ........ 27, 66

Western Addmon^Community Organization v. Alioto, 340 F.Supp.

' ------------------------------------ -------------- 40

W°c S V1973)th AmCriCan Rockwe11 CorP-> 480 F.2d 64-1 (10th

........... ............. ................................................. 23, 28

' ' ’T f o th a r .T s S ? C°' V' P°°' Co,,s,""=do" C»-. 314 r.2d 405 .

................. ................................ 50

Zahn v. International Paper Co., 414 U.S. 291 (1973) ....26, 62, 66

VI

Statutes and Regulations

Page

29 U.S.C. § 160(c) ............ ....................................... .......................... 52

42 U.S.C. § 2000a................................................................................ 51

42 U.S.C. § 2000a-1 (a) ..._........... ........... .....................................5]) 55

42 U.S.C. § 2000a-2...................................................................... 51

42 U.S.C. § 2000a-3(b) .................. ........ ....................... ' ____ 55

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-3(a) .......... ................. .......................................... 51

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(a) ........................ ......................... .............. g3

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g) ............ ................. ...............................25, 51, 55

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) .......... ................. .................... _ _ 5g

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23, 54(c), 8 2 ............ ...............:.... ................J7j 27, 58

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, “Guidelines on Em

ployment lesting Procedures,” 29 C.F.R § 1607 1 et sea

197°) ........................ - ......... -----............................... :..... 34, 35; 40

Other Authorities

Ainsworth, Paper, The Fifth Wonder (2d Ed. 1959) _________ ___ 4

American Psychological Ass’n., Inc., Standards for Educational and

Psychological Tests and Manuals (1966) ........................ 34 37

Barrett, Gray Areas in Black and White Testing, 46 Harv Bus

Rev. 92 (1968) ......... .................... ........................ ;_____ ‘ ' 3Q

BNA, Daily Labor Report No. 8 (Jan. 13, 1975) .............. ............ 36

Boehm,'A'egro-White Differences in Validity of Employment and

rrammg Selection Procedures, Summary of Research Evidence,

55 Journal of Applied Psychology, 33 (1972) ____ ___ ____ ’ 45

Cooper and Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under Fair Employment

Laws: A General Approach to Objective Criteria of Hiring &

Promotion, 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1598 (1969) ........ .... .............. 40

111 Cong. Rec. 12819 (1964) .............. ......... ........... ^

vii

4

Page

E. F. Wonderlic and Assoc., Inc., Negro Norms, A Study of 38,452

Job Applicants for Affirmative Action Programs (1972) ......... 30

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, “Guidelines on Em

ployment Testing Procedures,” BNA Daily Labor Report No.

174 (Sept. 7, 1966) ....... ,.........................................................16, 35

Gael & Grant, Employment Test Validation for Minority and Non-

minority - Telephone Company Service Representatives, 56

Journal of Applied Psychology 135 (1972) ........................ ...... 41

H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong. 1st Sess. (1963) ........................ .... 53

Schmidt, Berner & Hunter, Racial Differences in Validity of Em

ployment Tests: Reality or Illusion, 58 Journal of Applied

Psychology 5 (1973) ................................................................. 41

L’III

I.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit is reported at 474 F.2d 134 (4th Cir 1973).

The decision and order of the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of North Carolina is reported in

..... F.Supp ... 4 FEP Cases 561 (E.D.N.C. 1971), and

earlier rulings by that Court on various motions are reported

at 271 F.Supp. 27, i FEP Cases 234 (1967); 2 FEP Cases

1002, 1081 (1970).

II.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit was entered on February 20, 1973. A timely petition

for rehearing en banc was granted on June 25, 1973. After

briefing to oral argument before the en banc court, a ques

tion of appellate procedure was certified to This Court by

the Court of Appeals on December 6, 1973. The opinion of

This Court on the question certified was delivered on June

17, 1974. Pursuant thereto, the Court of Appeals, on July

22, 1974, vacated its earlier order granting the petition for

rehearing en banc and denied Petitioner’s petition for re

hearing. A petition for a writ of certiorari to the Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit was filed on October 7, 1974

and was granted on December 16, 1974.

This Court’s jurisdiction is invoked under 28 U S C

§1254(1).

III.

STATUTES AND REGULATIONS INVOLVED

A. Section 703(h) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, P. L

88-352, 78 Stat. 255, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(h):

2

Notwithstanding any other provision of this title, it

shall not be an unlawful employment practice for an

employer to apply different standards of compensation,

or different terms, conditions, or privileges of employ

ment pursuant to a bona fide seniority or merit system,

or a system which measures earnings by quantity or

quality of production or to employees who work in dif

ferent locations, provided that such differences are not

the result of an intention to discriminate because of

race, color, religion, sex or national origin, nor shall it

be an unlawful employment practice for an employer

to give and to act upon the results of any professionally

developed ability test provided that such test, its ad

ministration or action upon the results is not designed,

intended or used to discriminate because of race, color,

religion, sex or national origin. It shall not be an un

lawful employment practice under this title for any

employer to differentiate upon the basis of sex in deter

mining the amount of the wages or compensation paid

or to be paid to employees of such employer if such

differentiation is authorized by the provisions of section

6(d) of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 as

amended (29 U.S.C. 206(d) ).”

B. Section 706(g) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 P L

88-352, 78 Stat. 255, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g):

If the couit finds that the respondent has intentionally

enSagecl >n or is intentionally engaging in an unlawful

employment practice charged in the complaint, the

court may enjoin the respondent from engaging in'such

unlawful employment practice, and order suchaffinna-

tive action as may be appropriate, which may include

reinstatement or hiring of employees, with or without

back pay (payable by the employer, employment

agency, or labor organization, as the case may be, re

sponsible foi the unlawful employment practice) In

terim earnings oi amounts eamable with reasonable

diligence by the person or persons discriminated against

3

shall operate to reduce the back pay otherwise allow

able.”

* * *

C. Rule 23, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

D. The “Guidelines on Employment Selection Proced

ures” 35 F.R. 12,333 (August 1, 1970); 29 CFR §§1607.1-

1607.14.

This has been reprinted in the Single Appendix hereto

at pages 305-320.

IV.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

A. Whether the District Court’s refusal to enjoin Albe

marle’s use of employment tests was error as a matter

of law.

B. Whether the Court of Appeals usurped the powers and

function of the District Court by failing to remand the

issues on testing.

C. Whether the District Court had traditional equitable

discretion to determine whether back pay was an ap

propriate remedy.

D. Whether a class action for back pay under Rule 23 of

the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure is inherently in

consistent with the Congressional intent behind the re

medial provisions of Title VII, particularly as to class

members who have not filed a charge with the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission.

-a'-* «-• am,I 1,1,

V .

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is an action brought on August 25, 1956 bv four

black employees' of Petitioner's Roanoke Rap ds No-.I

v i? o tb T c -T ? r a/ a private d “ ^t" e ^ v'd ivjghts Act of 1964. ( \ 6 )2

tiom 'm tQ O 7 " T mi" , a t ROan°k t ^ P M s began opera-

operations, papermaking

canv thE’ Albemarle Paper Manufacturing Com

L a ^ W,he , t h 3 iqUireu ‘he mUI- * * * * * l° " x x ta n iw and - echnologically sophisticated machinery And

equipment necessary to bring the mill to its present i 000

•on per day capacity and to make the mill efficiru, V H

t - i m a m -P T ’ ^ Lxhiblt **o. 36A, pp. 68-69)

Dlrx°f V T ke Rapids mil1 is a Ktodem, highly com-

P ci ity, employing approximately 650 people which

operates continuously, 24 hours a dav 7 A ? P ’ ,

days a year. }’ 7 days a week> 3G2

A pulp and paper mill may be simply described3 a

complex,aclity in which raw m a te ria l U "

,(A ........»reterence, to the record are to a d e ^ i f f i S f & £ & c t d

Ainsworth, pjper, The 9 J ° i v '7 derives from

Judge observed the p m c 2 as !t L S Z ? e S t r i c t

during Ins view of the facility Defendant’̂ RaPids Mill

Plaintiffs Exhibit No. 34A, ppy321?367 E* nblt N a 19- See also

5

chemicals and water arc combined in a cooking: or digesting

operation to separate wood fiber to be made into paper

from the lignin and other materials found in the raw wood,

the separated fiber in the form of pulp being delivered to

complex, intricate paper milling machines and the residue

lignin, chemicals, water and waste being recycled through

massive recovery furnaces, precipitation and filtration

equipment to recover the chemicals and to prevent air and

water pollution.

Like ncarlyr all paper mills, the Roanoke Rapids mill is

organized into functionally distinct departments. In order

to provide on-the-job training for functionally related jobs

and to overcome the lack of an adequate specialized labor

market in the locality', each of the departments is organized

into functionally related lines of progression through which

employees can move into more demanding jobs as vacancies

occur, on the basis of seniority', ability and experience. En

try' into a line of progression is generally' from the Extra

Board, a reservoir of employees available as needed to staff

entry level jobs in the various lines of progression. (A 88-

89, 104)

Each of the functionally distinct departments contri

butes to the central purposes of paper-making. The Wood-

yard Department gathers and prepares the wood for fur

ther processing/

4 The wood is delivered (by both railroad and truck) in the form

of Chips, sawdust and logs. The Chip Unloader registers chips and

sawdust receipts, records the condition of the particular shipment,

operates a screen to take foreign matters out of the chips or sawdust,

and then operates conveyor equipment to distribute the screened'

material.

Logs are unloaded by the Large Crane Operator and then are un

loaded by the Long Log Stacker Operator. Next the logs are debarked

and converted into chips by means of a conveyor system, debarking

drums, and Chippers (Nos. 1 and 2). The Chain Operator controls the

conveyor from the woodpile dirough the debarking drum. The Chipper

6

At the time of the trial in this case, the Woodyard De

partment was organized into a line of progression for

seniority and promotion, training and flexibility of the

workforce as follows (A. 109):

UuIlcJozcr

Operator

t___

WOOD YARD DEPARTMENT

Crane Operator (American)

t

Crane Operator

(Large)

t

Long Log Operator

T

Log Stacker Operator

T

Small Equipment Operator

A

Oiler

T

Chip Unloader

Clapper Operator No. 2

T

Chain Operator

T

Chipper Operator No. 1

o- TTractor Operator «

. t

Chip Bin Operator

' f

Laborer

(Start)

— '■ ‘ S

Auxiliary functions in the Woodvard are performed hr rvi

who services the equipment in the Woodvardmhe Buhdozer Operator'

7

The Pulp Mill Department is concerned with the con

version of wood chips into pulp,5 through a cooking opera

tion in a chemical solution under high temperature and

pressure to separate the wood fibers for subsequent con

version into paper, with the residues in the cooking solu

tions being sent to a recovery operation so that the very ex

pensive chemicals can be reclaimed for subsequent recy

cling.6

At the time of trial in this case, the Pulp Mill Depart

ment was organized into lines of progression for seniority

and promotion, training and flexibility of the workforce as

follows (A. 109):

5 Soft wood is basically 50% cellulose, 30% lignin and 20% car

bohydrates, etc. The cellulose is composed of innumerable fibers, finer

than a human hair and 2 to 4 millimeters in length. The fibers are

held together by the lignin. The pulp process separates the fibers by

dissolving the lignin binder in chemical solutions, which in proper

concentration does not seriously attack the fibers. The sodium chemicals

used in the process are reclaimed and reused. While the basic process is

simple, its accomplishment on a scale required by a modem paper

mill is technologically complex.

c The cooking process is the responsibility of the Digester Operator,

who directs the charging of the cookers with the proper mix of pine,

hardwood chips, sawdust and chemical solutions and controls the

temperature and pressures at which this operation must be carried

out.

Following the cooking process, the cellulose fibers are washed clean

and the clean fibers are then put in storage tanks for use on the paper

machines. The washing operation is the responsibility of the Stock

Room Operator with the assistance of the Stock Room 1st Helper

and 2nd Flelper.

The C. E. Recovery' Operator, with the assistance of the 1st Helper

No. 6, Evaporator Operator, 1st Helper No. 5, 2nd Helper, and Utility-

Helper, is responsible for the intricate process of operating the

recovery- boiler for purposes of reclaiming the chemicals used in the

cooking process. In that connection, the Caustic Operator, with the

help of the Lime Kiln Operator, is responsible for reclaiming lime

for use in the cookers.

- —

Digester Operator

[Cooker)

t

Stock Room Operator

T

Stock Room 1st Helper

Stock Room 2nd Helper

A

PULP MILL DEPARTMENT

C. E. Recover)' O perator Caustic O perator

! f

1st H elper No. 6 Lime Kiln O perator

‘‘'E vaporator O perator

t

1st H elper No. 5----------------------

T

2nd H elper

t

U tility H elper

By Products O perator

_ t

hen Used

, tLead loader-Blower

T

Loader

(S tart)

1 he B Paper Mil]7 is concerned with the conversion of

pulp into paper.s At the time of trial in this case, the B

7 At the time of trial, the mill also had an “A Paper Mill” which

served the same functions as the B Paper Mill on a much smaller

p ile with less intricate machinery. The A Paper Mill is no longer

in operation. °

® From the Storage tanks at the end of the pulp operation, the

pulp goes to the Stock Room (Seater Room in old mills), where it

goes through refiners which cut the fibers into the desired lengths

and reject that part of the pulp not usable.

After passing through the Stock Room, where the pulp is refined

and subjected to chemical analysis by the Stock Room Operator helped

b>,,the, St?ck Room ls* and 2nd Helpers, the pulp is introduced into

a l ordrmier paper machine. The pulp is there distributed in a thin

layer onto a moving wire screen and then moves continuously through

a series of presses and steam-heated driers which remove water, con-

tro] t.nckness and convert the pulp into a continuous sheet of paper,

ihis intricate process must be under the constant control of the

won; force, who must make the proper adjustments in speed of flow

pressure, temperature, and other factors in order to keep the paper

of acceptable weight, moisture content and configuration As the

paper sheet leaves the paper machine, it is wound onto a reel. The

9

Paper Mill was organized into lines of progression for sen

iority and promotion, training and flexibility of the work

force as follows (A. 109):

B PAPER MILL DEPARTMENT

PA PER M A C H IN E ST O C K R O O M

Line of Progression Line of Progression

M achine T ender Stock Room O perator

t T

Back T ender Stock Room 1st Helper

t t

T hird H and Stock Room 2nd Helper

T

Fourtli H and

t

l i f th H and

t

Sixth H and

o tSeventh H and

t

Sparc H and No. 4

(S tart)

In 1965, the Mill began operation of a technologically

complex modern Power Plant Department to generate and

distribute electric energy to the mill and steam to the Pulp

Mill and Paper Mills in an amount necessary to supply the

needs of a small city. (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 4-9, p. 139).

This separate highly automated and controlled department

is organized into a line of progression as follows (A. 109):

POWER PLANT DEPARTMENT

Power Plant Operator

t

1st Helper

t

2nd Helper

(S tart)

paper machine operates continuously. As one reel of paper is filled

and removed, a new reel begins to wind without an interruption in

die process. The reel is then transferred to a winder, where the paper

is cut and sized.

10

The Technical Service Department is really the quality

control department of the mill, controlling the quality of

the raw materials used and of the products produced

throughout the entire 24-hour-a-day operation. The quality

control employees must have a working knowledge of phy

sics and chemistry, although a college degree is not re

quired. The department is organized into lines of progres

sion as follows (A. 109):

TECHNICAL SERVICE

M IL L L A B O R A TO R Y

B Mill Shift Testman General L ab Testm ant

Additive M an T

General Lab Assistant

t A

A Mill I estrnan

T

i '

Sam rlcm an

*T .

Trainee

There are also several additional support-function de

partments at the mill.9

With modernization of the mill in the early 1950’s10

9 T1^ Boiler Room Department operates small package boilers for

pp'Ts” 365)” *

The Service Department services the whole mill with general labor

services, fPlaintiffs Exhibit No. 34A, pp. 330-331). There is also

a Shipping Crew m the B Mill which weighs and bands the rolls of

paper at the loading docks and places them in either freight can or

341-344)r0ad S °r Shipment- (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No 34A, pp.

ThP r ^ ‘ ' n time! Certain, mi11 factions have been discontinued

he hamvT Department, which prepared surplus pulp for sale to

othei mills, was discontinued in 1969. ''A 245) The Prnrh,ot n

T ? " IS l!,FiniSlr S Cre"' « * d -o m in u e d k ? ^ 7 1 2« r Si I r Cr ,Q ^ shut oown in August of 1971, restarted in part (one

machine) m 19/2, and shut down entirely again in 1974, 1

11

Albemarle found itself in need of a significantly greater

number of skilled employees. (A. 346) The Company did

not have such employees in its employ and there was no

supply of skilled and experienced paperworkers in the local

labor market. (A. 347-348) In an effort to develop and

tiain its own pool of employees who could, with training,

progress to higher skilled jobs in the lines of progression,

Albemarle began to require that applicants for its skilled

lines of progression have a high school education. (Plaintiffs’

Exhibit No. 31, p. 219) When Albemarle found that the

high school education requirement by itself was not an ade

quate predictor of job success, its Personnel Manager was

directed to develop a better procedure for the selection of

employees for successful progression in the skilled lines of

progression. (A. 329, 339) The Personnel Manager, who

was professionally trained in industrial psychology, selected

the Revised Beta Examination (Beta)" and the Bennett

Mechanical Aptitude Test (Bennett).12 In order to verify

that the tests werc.,_a useful prcdirinr of joh .,n.

dertook a “concurrent validation study” by comparing

of the test results of a sampling of employees in the skilled

lines of progression with supervisory ratings of the em

ployees. (A. 99) 330) He determined that the Beta correlated

positively with job performance (A. 3301 and its use at the

mill continued. (A. 99)13 In 1963, as part of the continuing

effort to improve the quality of its workforce, Petitioner

, ” .A Professionally developed non-verbal test designed to measure

the intelligence of illiterate and non-English speaking persons.

skilTsA pr0feSS‘0nall>' deveIoped test for mechanical ability and verbal

13 Petitioner found that the Bennett test did not validate for its

operations and use of this test was discontinued sometime in 1963

or be,ore. 1 here is no evidence that any employee or potential employee

was disqualified by reason of his score on Bennett.

12

added the Wonderlic Test Forms A and B34 (A 9C?n n

^ « P < U £ M

education os ifs ^ ^

off score of 100 nn the p • j r f d f achleve a cut-

either the Wonderlic A ?**?, Examination and 18 on

100) CSt °r the W°nderlic B test. (A. 99,

c * t ™ T Z l « L : T A">emar,C had the edu-

employees’ ^

j ° bs it. fo? ^

changes in tn ill opera tion" , ™ gT o f c e rta ,t

r - t r c s S iF ,-W A r a S r ?en try in to a to ta l o lfifteen i™ f ° r

to “ “^%^XssiK3.ta:

» A professionally developed test of mental ability and reading skills.

gression; Pulp Mill Grew line of pro-

Operator and Caustic Operator l £ S C' E’ Rccover>'

Department Paper Machine and Beater ^ Paper Ml11 *

B laper Mill Department— Paper M a c h in e !? ° Progression ;

progression; Product Department—FfnUh r ‘St°,ck Rooin lines of

tor, finishing Crew Siieeter Operator and^ e, few.'Rev^ ncJer Opera-

progression; Power Plant Department—Pm ShlPpinff ^ rew lines of

of progression; Technical Sendee Deoartm! ^ iTJu?* ° perator line

lines of progression; and Boiler Room^Denan ^ ,aild laboratory

line of progression. ' K°°m Department—Boiler Operator

13

certain changes in the lines of progression at the mill and, as

a result, Albemarle was able to reduce the test coverage

to applicants for entry into a total of twelve lines of progres

sion situated in six departments.16 Thereafter, further auto

mation and curtailment of certain mill operations occurred

(A. 90, 231-232) and by the time of trial in 1971, applicants

for entry into a total of only eight lines of progression, situ

ated in four departments, were required to fulfill the testing

requirements.17

Prior to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 3 964, there

were predominantly white skilled lines of progression and

predominantly black unskilled lines of progression. (A. 89)

The skilled lines of progression led generally to the higher

paying jobs in the mill. (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit Nos. 12-15, Ap

pendices A) The unskilled jobs, however, are among the

highest paying jobs in the Roanoke Rapids area—jobs

which paid on the average more than those of policemen,

schoolteachers, and most other jobs in the area. (Defendant

Albemarle’s Exhibit Nos. 11-17).

At the time of passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

there were two Extra Boards, one feeding the skilled lines of

progression and another feeding the unskilled lines of pro-

16 These were: Pulp Mill Department—Digester Operator, C. E.

Recover)' Operator and Caustic Operator lines of progression; B Paper

Mill—Paper Machine and Stock Room lines of progression; Product

Department (B Paper Mill)—Rewinder Operator, Sheeter Operator,

and Shipping Crew lines of progression; Technical Sendee Depart

ment—Mill and Laboratory lines of progression; A Paper Mill Depart

ment—Paper Machine line of progression; and Power Plant Depart

ment—Power Plant Operator line of progression.

17 These were: Pulp Mill Department—Digester Operator, C. E.

Recovery' Operator and Caustic Operator lines of progression; B

Paper Mill Department—Paper Machine and Stock Room lines' of

progression; Power Plant Department—Power Plant Operator line

of progression; and Technical Service Department—Mill and Labora

tory lines of progression.

1 di

gression. Employees were placed on the respective Extra

Boards either as new employees or by election to take Extra

Board work rather than lay-off in cases of reduction in

force. (A. 104) Prior to 1965, the Extra board for the

skilled lines of progression was predominantly white, that

for the unskilled lines was predominantly black. (A. 104)

With the passage of Title VII on July 2, 1964, to be

effective July 2, 1965, Petitioner undertook a series of steps

to insure that its employment practices would be in compli

ance with the law. Commencing in 1964, Petitioner began

an affirmative recruiting program to obtain black graduates

from high schools for its apprentice maintenance program

and for its other skilled lines of progression. (Plaintiffs’ Ex

hibit No. 32, pp. 531-533) While blacks had not been bar

red from taking the employment tests, after passage of Title

VII, Albemarle affirmatively sought to have all of its black

employees who had a high school education take the tests

so as to make them eligible for transfer into skilled lines of

progression. (A. 105) Thereafter, in 1965, Petitioner waived

the educational requirement as to all incumbent employees

and again sought to have all black employees take the tests.

(A. 105) In conjunction with the union, Petitioner in 1968,

organized and funded a school at which its employees could

acquire the verbal skills necessary to perform jobs in the

skilled line of progression. (R. 1181-1186).

As the law developed under Title VII it became appar

ent that seniority systems or other work conditions which

were racially neutral but which had the effect of perpetuat

ing past discrimination could be found violative of the

Act.18

In light of the judicial interpretations of the Act, Peti-

18 In Quarles v. Philip Morris, 279 F.Supp. 505, 516 (E.D. Va.

1968), tlie Court found “it is also apparent that Congress did not

intend to freeze an entire generation of Negro employees into dis-

15

tioner, at the first opportunity, took further affirmative

measures to ensure equal opportunities. In. 1968,..the two

Extra Boards were merged into a single board. (A. 245-246)

Employees who had formerly been in unskilled lines of pro

gression were given temporary assignments to skilled lines

even though such employees did not meet test and educa-

tional requirements, if it reasonably appeared from past

experience that the employees might be able to do some of

the lower Jobs in the skilled lines of progression. (A. 246)

The collective bargaining agreement at the Roanoke

Rapids mill which ran for the term September 18, 1965

through September 15, 1968, provided a system of “job

seniority” in a line of progression for advancement. (A. 286-

290) There was a provision for transfers from one line of

progression to another and from one department to another,

but there was no seniority . iglit to transfer and the transferee

did not carry either his rate of pav of his seniority with him.

It thus appeared to the Company' that under the developing

law the seniority provisions of the collective bargaining

agreement at Roanoke Rapids “tended to perpetuate past

discrimination as had the seniority’ provisions involved in

Quarles and Crown-Zellerbach.

Therefore, in 1968, in the first contract negotiations fol

lowing the Quarles and Crown-Zellerbach decisions, the

criminatory patterns that existed before the act,” and held a seniority

system which tends to perpetuate past discrimination is not bona fide

under Section 703(h) of Title VII.

On March 26, 1968, the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Louisiana, in the case of United States v. Local 1S9,

Papermakcrs Union (Croivn-Zellcrbach), 301 F.Supp. 906 (E.D. La)

1969) aff’d., 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919

(1970) entered a temporary injunction ordering the Crown-Zellerbach

Corporation to abolish the “job seniority” system at its paper mill in

Bogalusa, Louisiana, and to replace it with a “mill seniority” system

with transfer provisions including carrying seniority to a new job with

red-circling of rates.

16

Company and the Unions negotiated a contract clause to

provide for transfers on the basis of “mill seniority,” 19 for

the carrying, of “mill seniority” with the transferee for pur

poses of advancement and for the “red-circling” of the trans

feree's rate of pay (i.e., if an employee transferred to a lower

paying job, he would be paid his old rate of pay until his

late m the new line of progression caught up to Iris old

rate). (A. 98) This collective bargaining agreement was for

a term beginning September 23, 1968. The relevant seniority-

provisions were sections 10.2.2 and 50.2.3. (A. 292-293)

In May, 1966, charges were filed with the Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Commission by Joe P. Moody, Theodore

Daniels, Henry Hill and Arthur Mitchell, alleging discrimi

nation because of their race. (A. 273-282)

These charges were served on defendants on August 11,

1966, and the EEOC investigator gave defendant, Albe

marle Paper Manufacturing Company, fifteen days, i.e., until

August 26, 1966, to answer. However, before the Company

could respond, on August 24, 1966 the first EEOC Guide

lines on Employment Testing Procedures20 were published

and on August 25, 1966 the complaint in this case was filed

m the United States District Court for the Eastern District

of North Carolina. (A. 6-10) The Complaint simply alleged

in very general terms discrimination on account of race

against Plaintiffs in violation of Title VII. The prayer was

for injunctive and other equitable relief on behalf of Plain

tiffs and the class they claimed to represent. (A. 10) By mo

tion for summary judgment, Albemarle immediately raised

the question whether Plaintiffs could bring a class action

19 While the contract did not, sirictly speaking, provide for mill

S(T°2r33y-234)e SyStCm nCS°tlated was tantamount to mill seniority.

” BNA> DaiIy Labor Report No. 174 (Sept. 7, 1966).

17

under Rule 2 3 . (See Motion for Summary Judgment filed

October 5, 1966.) In their brief in opposition to that motion,

Plaintiffs maintained the position :

“It is important to understand the exact nature of the

class relief being sought by Plaintiffs. No money dam

ages are sought, for any member of the class not before

the Court, nor is specific relief sought for any member

of the class not before the Court. The only relief sought

for the class as a whole is that defendants be enjoined

from treating the class as a separate group and dis

criminating against the class as a whole in the future.”

(A. 13-14) (Emphasisadded).

The District Judge, John D. Larkins, Jr., overruled the

motion for summary judgment, but in the same order

granted a motion to dismiss the International Union as a

defendant on die ground ir had not been named in the

charges filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission. (A. 16-20)

Following Judge Larkins’ ruling, the case proceeded to

the discovery stage. While the case was in this posture, on

October 31, 1968, the assets of the Mill were sold to

Hoemer Waldorf Corporation, a Delaware Corporation,

which in turn assigned them to a new Albemarle Paper

Company, a Delaware Corporation. The proceeds of the

sale were assigned to First Alpaco Corporation which later

merged into Ethyl Corporation, the parent of the old

Albemarle Paper Company." (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 36B pp.

67-69)

On March 12, 1970, the United States District Court for

the Middle District of North Carolina, decided the case of

21 F ed . R. C iv . F . 23.

22 For convenience, the term “Albemarle” is used in referring to

the employer of Respondents.

1

18

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 319 F.Supp. 835 (M.D.N.C.

1970) aff’d. 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir.), petition for cert, dis

missed, 404 U.S. 1006 (1971), in which District Judge

Eugene A. Gordon, in a Title VII case, on motion first made

after his findings on the merits of the case, in his discretion,

allowed damages in the form of back pay. Thereafter, in

1970, the issue of damages was injected into this case far

the first time. (A. 28-29) On June 25, 1970, Plaintiffs moved

to join Iioerner Waldorf Corporation, Ethyl Corporation,

First Alpaco Corporation and the new Albemarle Paper

Company (Delaware) as parties defendant. The old Albe

marle Paper Company (Virginia) filed a motion to dismiss

on August 20, 1970. The District Judge, John D. Larkins,

Jr., issued his opinion and order on these motions on Sep-

tembei 29, 19/0, (A. 30-39) denying' the motion to dismiss,

permitting the joinder of the parties defendant23 and stating:

“Rule 54(c) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

provides in part: ‘except as to a party against whom a

judgment is entered by default every final judgment

shall grant the relief to which the party in whose favor

it is rendered is entitled, even if the party has not de

manded such relief in his pleadings.’ The'possibility of

an award of money damages upon a determination of

liability is still with us. It is not yet the proper time to

drop the plaintiffs’ claims, which are, at least, litUable ”

(A. 37-38) 5

Following This Court’s decision in Griggs v. Duke Power

Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971), the management • at the Mill

promptly employed Dr. Joseph Tiffin, a professor at Purdue

University, and an eminent industrial psychologist. Using

the standard “concurrent” method of validation, Dr. Tiffin

Process was never served on I'irst Alpaco Corporation and it has

never participated in this case.

conducted further validation studies on the tests in use for

certain of the skilled lines of progression. (A. 165-166)

As a result of his study, Dr. Tiffin concluded that the tests

could reasonably be used for both hiring and promotion for

most of the jobs in the Mill. (A. 438)

In the meantime, this case was transferred from Judge

John D. Larkins, Jr. to Judge Franklin T. Dupree, Jr., who,

at a conference of attorneys on May 17, 1971, on motion

of Defendant, ordered the case set for trial beginning at

10 a.m., July 26, 1971, at Raleigh, North Carolina.

First on May 28, 1971 and again on June 15, 1971, the

District Court ordered plaintiffs to answer Defendants sup

plemental interrogatory, which read:

“List the specific names of each employee or former

employee whose personnel record or records in any way

establishes or tends to establish any discrimination by

Albemarle Paper Company in its employment prac

tices and explain how such a record or records show

discrimination giving the specific dates and instances.”

(A. 44,46).

By order dated July 8, 1971, the District Judge defined

the class, provided for notice to the class, ruled that dam

ages might be recovered in this action and stated his inten

tion to have all such claims for individual monetary relief

tried with other issues at the trial, reserving the right to

refer some of such issues to a master if the claims were too

numerous or complicated to be completed at trial. (A.

50-52)

On July 10, 1971, the parties agreed to a Stipulation of

Facts, which included most of the relevant facts in the case,

(A. 86) and on July 19, 1971, the parties agreed to and

executed an elaborate pretrial order.

20

I j etrial Order, Plaintiffs listed 134 witnesses of

whom 128 were:

“Black employees or former employees of Albemarle

Paper Company who may be called to testify about

their terms, conditions, privileges of employment such

as jobs held, wages l'cceived and testimony going to the

question of backpay.” (See Pretrial Order entered Tuly

19,1971 at pp. 78-90)

The case came on for trial before the Honorable Franklin

T. Dupree, Jr., promptly at 10:00 a.m., Monday, July 26,

1971. There were four major issues: (1) Whether there

should be injunctive relief with respect to the seniority sys

tem at the mill; (2) whether the testing and high school

educational requirements were unlawful; (3) whether there

should be back pay and (4) whether there should be attorney

fees.

In an efrort to reduce the scope of the trial, Albemarle

consented to the entry of an order providing mill seniority

and red-circle rates for members of the class by representing

in its opening statement as follows:

If tne Court please, I think there are four issues here

and I will address myself to them very briefly. First

the injunctive relief. The defendants believe that no

injunction is warranted in this case. We believe that

whatever relief they may have been entitled to some

years ago we took care of in 1968, and that under the

circumstances we would fight very hard not to be en-

joined. However, without admitting any violation of

Title VII, we have concluded to say to your Honor this

morning that insofar as an injunction to provide plant

seniority for these people along the lines of the system

that vve set forth in the proposed consent agreement, a

copy of which I have left on your desk, we would not

buiden the Court today with all the evidence that we

21

think bears on that issue. I think it’s all in the deposi

tions. And without admitting any guilt on our part, we

can eliminate that part of the case because we would

not object to an order along those lines.” (A. 114-115)

The trial of the case consumed eight full trial days and one

day for the Court to view the Mill. There were literally

scores of members of Plaintiffs’ class in attendance at the

trial. The District Judge did not limit the evidence in any

way. Plaintiffs called eleven employee, or former employee,

witnesses and introduced the depositions of five others.

The District Judge made extensive findings of fact, found

the Company’s testing program “job-related” and declined

to enjoin its use. In his discretion the Judge denied back

pay to plaintiffs. However, the Court ordered a mill sen

iority system and, finding the tests sufficient for the purpose,

proscribed the use of a high school education requirement

for employment. (See A. 497, 499-502)

Plaintiffs appealed to the United States Court of Ap

peals for the Fourth Circuit and the case was heard by a

panel, consisting of Circuit Judge J. Braxton Craven and

Senior Circuit Judges, Herbert S. Boreman and Albert V.

Bryan, whose decision is best explained by them:

“The district court refused to order the abolition of or

changes in the pre-employment testing procedures used

by Albemarle. Plaintiffs appeal from the district court’s

determination. Judge Boreman concurs with Judge

Craven in reversing and remanding to the district court

on this issue. Judge Bryan dissents.

“The district court also refused to award the plaintiffs

back pay. Judge Bryan concurs with Judge Craven in

reversing the district court on ’this issue. Judge Bore

man dissents.

22

“The effect of this division in the court is to reverse

and remand the district court's determinatipn as to the

testing procedures and the refusal to award back pav ”

(A. 531) J

Defendants asked for a rehearing and made a suggestion

of rehearing en banc which was granted on June 25, 1973.

Supplemental briefs were filed and argument was heard on

October 2, 1973.

On December 6, 1973, Chief Circuit Judge Clement F.

Haynsworth certified to This Court the following-

“Under 28 U.S.C. §46 and Rule 35 of the Federal Rules

of Appellate Procedure, may a senior circuit judge, a

member of the initial hearing panel, vote in the deter

mination of the question of whether or not lire case

should be reheard en banc?” (A. 540)

The certification also stated:

“If the en banc court reaches the merits, the tentative

vote is that it will modify the panel decision with re

spect to an award of back pay.” (A. 540)

17, 1974 Phis Court answered the certified ques

tion in the negative and on July 22, 1974 the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit denied Defendants’

petition for rehearing.

On October 7, 1974 Defendants filed a petition for a

writ of certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit with This Court. The writ was granted

on December 16, 1974.

23

VI.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

A. The District Court Correctly Refused To Enjoin The Use Of

Albemarle’s Testing Procedures.

1. I n t r o d u c t io n

This case involves the interpretation of principles laid

down-in Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1970),

with respect to the use of employment tests.

2- T h e . E v id e n c e I n T h i s C a s e S h o w s A l b e m a r l e ’s T e s t s

W e r e N o t D is c r im in a t o r y .

There was no demonstration in the trial court that Albe

marle’s tests, the Beta and the Wonderlic A & B, had a

racially disparate effect upon a proper statistical universe

i.e. otherwise qualified blacks emploved in, or candidates

for employment at the Roanoke Rapids mill. Mayor v. Edu

cational Equality League, 415 U.S. 605, 620 (1974). The

tests not having been shown to discriminate in the first place,

there was no basis to proscribe their use. McDonnell Douglas

Carp. v . Green, 411 U.S. 792 ( 1973); Bridgeport Guardians,

Inc. v. Civil Service Commission, 482 F.2d 1333 (2d Cir.

1973); Hester v. Southern Railway Co., 497 F.2d 1374 (5th

Cir. 1974); Woods v. North American Rockwell Corp. 480

F.2d 644 (10th Cir. 1973).

3. A l b e m a r l e D e m o n st r a t e d T h e T e s t s T o B e A R e a s o n

a b l e M e a s u r e O f J ob P e r f o r m a n c e .

(a ) The District Court Found That Albemarle’s Tests Were

Job Related.

The District Court found, based in part on a view of the

mill, that certain native intelligence and reading skills

were required for the safe and efficient operation of the

mill. That Court also found that Albemarle’s tests had

24

undergone validation studies and had been proven to be

job related.

(b) The Findings Of The District Court Have Not Been Shown

To Be Erroneous.

Ih e attack on the tests in the Court of Appeals was not.

that the tests were not job related, but that Albemarle had

not proven them to be job-related in strict accordance with

the EEOC Guidelines. The proper test is not compliance

with the guidelines, Espinoza v. Far ah Manufacturing Co.

414 U.S. 86, 94 (1973), but whether the tests are proven

job related to the satisfaction of the Court. Vulcan Society

v. Civil Service Commission, 490 F.2d 387, 394 (2d Cir

1973); Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725 (1st Cir. 1972);

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Civil Service Commission, 482

F. 2d 1333 (2d Cir. 1973) ; United States v. Georgia Power

Co., 474 F.2d 906 (5th Cir. 1973). Relying primarily on the

guidelines and on contentions of fact raised for the first time

on appeal, the Court of Appeals erroneously found fault with

Albemarle’s proof of job relatedness.

(i) Job Analysis

Albemarle’s expert conducted an empirical validation

study which correlated test scores with supervisory- ratings of

actual job performance. In such a situation a written job

analysis is unnecessary and its absence is irrelevant to the

integrity of the correlations.

(ii) Supervisor R atings

Test validations do not fail as a matter of law upon an un

supported presumption that supervisors’ ratings are racially'

biased. McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U S 792

(1973). There is no basis for a presumption of supervisors’

bias in the first place and such bias clearly could not have

affected the correlations obtained in this case.

25

(iii) Business Necessity

The objections raised concerning the use of a test for

incs of progression m which' the test had not been speci

fically shown to validate are based primarily on the Court

of Appeals nnsassumption of facts and, in any event vo

o the utilization of the tests, not their job-relatedness. The

lawful USC thC lCStS by th e m a tic is reasonable and

B' D m D r VC7 Th; C°Urt ° f Appeals Errcd ^ Not Remanding J lle Testing Issue To 1 he District Court.

\Vhen new standards of proof are set forth, simple fair-

ness requires the party against whom the new rule is in-

VM?D ' C // n dCd; 311 °PPOrtUnity to present its evidence.

MQmT p f T Corp- v- U.s. 792, 807(ty/Oy , England v. Louisiana Medical Fram^rcrs *7^ TT c

411 (1964); W J * S!ales v. £ £

6 (5th Gir. 1973). Especially is this true where, as here

the factT °f APPCalS engaged in its own determination of

c - The District Court Had Traditional Equitable Discretion To

Determine Whether Back Bay Was An Appropriate Remedy.

1 T it c e V I I L ea ves T h e A w a r d O r D e n ia l O f Ba c k P ay

C ou rts '" “ E 2 u ita b le D i s c r e t e O f T h e D is t r ic t

D; Phe Pi f m Ia^ u ag e of the Statute expressly vests the

<< ™ , C°Urt Wlth thc discretion to fashion remedies as

nay be appropriate, which “may include reinstatement

nng ° CmpI°yces, Wlth or without back pay.” Section

reverfil 0f thU'SDC't .§20? ° '‘5 (g ) ' The Fourth Circuit’s e\ ersal of the District Judge’s denial was based on its

adoptive special circumstances” standard. This standard

whch mandates an award of b a d p a , in e v ^

O

26

sa\ c exceptional cases, contravenes the legislative intent

behind the express language of the Act. Curtis v. Loctker,

415 U.S. 189 (1974) ,■ hober v. IVeslinghousc Electric Co.,

480 F.2d 240 (3d Cir. 1973); 111 Cong. Rec. 12819 (1964).

2. 4 h e D is c r e t io n O f A T ria l C o u r t R egarding T h e B ack

P ay R e m e d y S h o u l d B e G uid ed B y T r a d itio n a l E q u it a b l e

P r in c ip l e s .

Xiial courts in fashioning decrees to remedy violations

of Title VII should be free to apply equitable considerations

in light of all the facts and circumstances of the case. Two

of those factors were cited by the District Judge below: the

good faith of Albemarle, and the plaintiffs’ tardiness,

amounting to laches, in presenting the back pay claims.

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906 (5th Cir.

1973); Rental Development Corp. of America v. Lavery

304 F.2d 839, 842 (9th Cir. 1962).

f

3. E v e n U n d e r A “S pe c ia l C ir c u m s t a n c e s ” S ta nd ard , T he

D is t r ic t C o u r t W as J u s t if ie d I n D e n y in g B a c k P ay /

Even if a “special circumstances” rule is correct, the

factors cited by the District Court make this an excep

tional case.

D. Back Pay Should Not Be Awarded To Class Members Who Did

Not File Charges With The Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission.

Back pay is individual redress for damages actually suf

fered as distinct from class wide prospective remedial meas

ures. The previous filing of a charge with the EEOC is a

jurisdictional requirement for individuals seeking relief under

Title VII. McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S.

792 (1973). The device of a class action under Rule 23 of

27

the Pederal Rules of Civil Procedure may not be manipu

lated to confer jurisdiction over such individual claims where

it does not otherwise exist. F ed . R. C iv . P. 82; Zahn v. Inter

national Paper Co., 414 U.S. 291 (1973); Snyder v. Harris,

394 U.S. 332 (1969); JVeincr v. Bank of King of Prussia,

358 F. Supp. 684 (E.D. Pa. 1973); Sperberg v. Firestone

Tire&Rubber Co., 61 F.R.D. 70 (N.D. Ohio, 1973).

VII.

ARGUMENT

A. The District Court Correctly Refused To Enjoin The Use Of

Albemarle’s Testing Procedures.

1. I n t r o d u c t io n

This case presents to the Court several questions either not

reached or not definitively settled in Griggs v. Duke Power

Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971). In Griggs the Court considered

the use of a standardized general intelligence test as a condi

tion of employment in or transfer to jobs when (a) the stan

dard is not shown to be significantly related to successful job

performance, (b) the requirement operates to disqualify

ISegioes at a substantially higher rate than white applicants,

and (c) the jobs in question formerly had been filled only by

. white employees.

In this case the District Court found that the jobs in

Albemarle’s skilled lines of progression formerly had been

filled only by white employees, made no finding with in

spect to whether Albemarle’s tests had a disparate racial

effect, and finally found that, in any event, Albemarle’s

tests were significantly related to successful job perform

ance.

I

1

i

1

I

28

2. T h e E v id en c e I n T h i s C a se S h o w s A l b e m a r l e ’s T e s t s

W e r e N o t D is c r im in a t o r y .

In any Title VII case, plaintiff bears the burden of show

ing prima facie, discrimination. McDonald Douglas Corp. v.

Green, 411 U.S. 792, 802 (3973); Woods v. North Ameri

can Rockwell Corp., 480 F.2d 644, 647 (10th Cir. 1973).

In the testing context plaintiffs most often make this showing

with statistics from tests previously administered by the de

fendant employer. Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725 (1st Cir.

1972) ; Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Civil Service Commis

sion,482 F.2d 1333 (2d Cir. 1973) ; United States v. Georgia

Power Co., 474 F.2d 906 (5th Cir. 1973); Carter v. Gal

lagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir.), cert, denied, 406 U.S. 950

(1972). But whatever the method, failure to show that a test

has a disparate effect on . the minority group has been and

should be fatal to a Title VII plaintiff’s case, Bridgeport,

supra at 1339; Hester v. Southern Railway Co., 497 F.2d

1374, 1381 (5th Cir. 1974) ; Woods, supra, at 647.

This threshold question of whether Albemarle’s tests had

a disparate effect on the members of the class in this case

was never specifically addressed in the District Court and

the District Court made no findings of fact as to any dis

criminatory effect of the tests. Indeed, plaintiffs’ proposed

findings did not even include a provision bearing on this

issue.

The Amicus Curiae, Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission (hereinafter EEOC), tried to correct this

glaring deficiency in plaintiffs’ case, in its brief24 to the Court

of Appeals. Purportedly utilizing plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 10,25

24 All briefs filed in the Court of Appeals were included in the record

sent to this Court.

25 Exhibit No. 10 is supposedly a composite of all of Albemarle’s per

sonnel records, which plaintiffs had taken two weeks to microfilm. No

29

Amicus Curiae contended that it showed that on Wonderlic

A blacks averaged 17 and whites averaged 24.9, with 96% of

the whites and 64% of the blacks obtaining a passing score,

and that on Wonderlic B blacks averaged 14.8 and whites

averaged 21.9. Amicus Curiae did not point out that the

same exhibit also showed that on the Beta, blacks averaged

104.20, whites 107.56 against a cut-off score of 100.00. But

in their Supplemental Brief on Rehearing at page 36, the

Amici Curiae (the EEOC now joined by the United States)

conceded:

. . the evidence on the Beta alone showed only a

slight, and perhaps not statistically significant impact.”

(Brief for the United States and the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission as Amici Curiae on Prehear

ing En Banc, p. 36).

Nevertheless, the majority panel of the Court of Appeals

began its discussion of testing by noting:

“The plaintiffs made a sufficient showing below that

Albemarle's testing procedures have a racial impact.”

(A. 515)

In support of that conclusion the Court of Appeals Panel

cited in a footnote some statistics concerning the Wonderlic

tests, but never mentioned the Beta.

Thus, the finding by the Court of Appeals Panel is first of

all grievously and astonishingly deficient in enjoining Albe

marle’s use of the Beta, as to which there was absolutely no

evidence, either presented to the District Court or otherwise,

to show a disparate racial effect. As Dr. Richard Barrett

specific contentions based on Exhibit No. 10 were ever made in the

District Court despite Albemarle's strenuous efforts to elicit them.

(See R. 52-54.)

30

pointed out in his article, Barrett, Gray Areas in Black mid

White Testing, 46 Harv. Bus. Rev. 92, 93 (1968):

“A test that places no special obstacle in the path of

Negro applicants cannot be said to be discriminatory.” 26

As a consequence of this failure of proof by plaintiffs,

Albemarle is clearly entitled to a reversal of that portion

of the Court of Appeals’ judgment proscribing further use

of the Beta.

But even as to Wonderlic, plaintiffs’ proof is deficient

on the threshold question of whether the test was dis

criminatory. The Court of Appeals Panel concluded that

this requirement was satisfied by reference to Exhibit No. 10

and to general statistics. But, while these factors may be

the basis for speculation that the Wonderlic tests exclude

more blacks than whites, they are not proof of discrimina

tory effect at the mill at Roanoke Rapids.

The calculation and factual extrapolation from Exhibit

No. 10 was never presented to the District Court; in fact, it

was before the Court of Appeals that the possibility was first

raised that Exhibit No. 10 could be utilized as proof of dis

parate effect, and then the suggestion was made not by plain

tiffs, but by the Amicus Curiae, EEOC. The District Court

thus was never afforded an opportunity to consider the force

of this supposed evidence.27 Further, Albemarle was never

afforded the opportunity to demonstrate at trial that the

conclusion drawn by the EEOC and the Court of Appeals

26 This conclusion was confirmed by plaintiffs’ other expert, Dr.

Katzcll, as well. (A. 403).

27 Nor was the District Court ever given the study, E. F. Wonderlic

and Assoc. Inc., Negro Norms, A Study of 38,452 job Applicants for

Affirmative Action Programs (1972) because it was fiied for the first

time with the Court of Appeals and served oil counsel for Albemarle

along with Appellants’ Reply Brief in August, 1972.

I

31

from Exhibit No. 10 was erroneous for the reason that the

statistical universe included test scores of employees who

could hardly read or write and whose verbal facility was no

more than 1 on the Wonderlic (R. 1135-6), and who were

therefore not potential candidates for the skilled lines of pro

gression.28

Having failed to prove disparate effect of the tests at

trial, plaintiffs may not rely on the suggestion in Griggs, 401

U.S. at 430, n. 6, that the Wonderlic has been shown to have

a disparate effect in other cases. If meaningful conclusions

are to be drawn a test “must be evaluated in the setting in

which it is used.” Georgia Power, supra at 912.29 A rule to

the contrary, aside from being illogical, would be inequitable

in imposing the heavy financial burden of validation on an

employer even though his tests do not discriminate against

minorities. In other words, if the test does not discriminate

in the first place, it should not have to be validated.

28 Since the District Court found that ability to read and write is a

job and safety requirement for the skilled lines of progression, the in

clusion of illiterate persons in the statistics relied on by the Court of

Appeals renders its conclusions about differential impact meaningless.

I This Court has recognized with respect to racial statistics that unless

j “the relevant universe for comparison purposes” is limited to poten

tially qualified persons, “simplistic percentage comparisons undertaken

by the Court of Appeals lack real meaning.” Mayor v. Educational

Equality League, 415 U.S. 605, 620 (1974). And see Harper v. Mayor

and City Council of Baltimore, 359 F. Supp. 1187, 1193 (D. Md.),

modified, sub nom. Harper v. Klostcr, 486 F.2d 1134 (4th Cir. 1973) ;

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 330 F. Supp. 203, 214 (SD N Y

1971); aff’d., 458 F.2d 1167 (2nd Cir. 1972).

29 Even Dr. Katzell, one of plaintiffs’ experts, acknowledged that,

in order to determine whether a particular test has a racially disparate

impact, it would be necessary to study its impact upon the particular

group involved. (A. 394-5).

t

32

3. A l b e m a r l e D e m o n s t r a t e d I t s T e s t s T o B e A R e a so n a b l e

M e a s u r e O f J ob P e r f o r m a n c e .

1 his Court held in Griggs at page 436:

“Nothing in the Act precludes the use of testing or

measuring procedures; obviously they are useful. What

Congress lias forbidden is giving these devices and

- mechanisms controlling force unless they are demon

strably a reasonable measure of job performance.

Thus, the question presented here is whether, even if

the unproven assumption that Albemarle’s tests had a

racially disparate effect were accepted, the Court of Ap

peals could hold as a matter of law that Albemarle failed

to make an adequate demonstration that its tests arc a

reasonable measure of j'ob performance. Albemarle sub

mits that the Couit of Appeals was in error in making that

determination.

(a) Defendants’ Tests Were Found To Be Job Related By The

District Court.

The tests used by Albemarle were professionally developed

to measure the very attributes found by the District Court to

be required for the skilled lines of progression. The Beta

measures the intelligence of the taker, even though he is

illiterate, (Katzell deposition, A. 360-2) ; the District Court

found that a high degree of native intelligence was a neces

sary attribute for workers in the skilled lines of progression.

(A. 494) The Wonderlic tests also measure general mental

ability and indicate the taker’s ability to read" and to under

stand what he has read. (Katzell deposition, A. 362-3); the

District Court found that reading ability was also a necessary

requirement for workers in the skilled lines of progression.

(A. 497) Without more, therefore, it would appear that the

33

tests were reasonable measures of a prospective employee’s

ability to perform the skilled jobs in the mill.

But Albemarle’s case docs not rest, merely upon this basis

since, through validation studies, Albemarle’s tests were

found to correlate significantly with actual job performance

at the mill. Before use of the Beta was instituted, in 1958,

a concurrent validation study established positive correla

tions.30 Further, after this Court’s decision in Griggs, Albe

marle retained an unquestioned expert in industrial psychol

og)7 to conduct a further validation study.31 As found by the

District Court this study confirmed the validity and utility of

the tests:

“This court has also found as a fact that a certain level

of native intelligence is required for the safe and effi

cient operation of Albemarle’s often complicated and

sophisticated machinery. The personnel tests adminis

tered at the plant have undergone validation studies and

have been proven to be job related. The defendants

have carried the burden of proof in proving that these

tests are “necessary for the safe and efficient operation

of the business” and are, therefore, permitted by the

Act. However, the high school education requirement

used in conjunction with the testing requirements is un

lawful in that the personnel tests alone are adequate to

measure the mental ability and reading skills required

for the job classifications.” (A. 497)

30 Sec, supra, p. 11.

31 The study was conducted by use of the “concurrent validation”

method. Ten skill-related job groupings were selected on the basis of

skill level and content of the jobs, as being typical of jobs in the skilled

lines of progression. Each employee in each group was rated in com

parison with each other employee in the group to obtain a ranking of

job performance and statistical correlation was performed to deter

mine correlation between job performance and test results. (A. 490).

The same method was also expressly approved in Watkins v. Scott

f .___ Efiper C o.,...F. Supp......, 6 FEP Cases 511, 537 (S.D. Ala. 1973).

34

It is clear, therefore, that the District Judge, who was

the trier of fact in this case, had no doubt that Albemarle

had demonstrated that its tests were related to perform

ance on the job.

(b) The Findings Of The District Court Have Not Been Shown

To Be Erroneous.

Plaintiffs’ contention in the Court of Appeals was not that

Albemarle’s tests were not job related (indeed the EEOC’s

Brief to the Court of Appeals as Amicus Curiae at p. 32 con

ceded that “they may very' well be job related” ). Rather,

plaintiffs contended that Albemarle had not proven job

relatedness in the manner required by the EEOC guidelines

in that (1) Dr. Tiffin's study had not been shown to have

fulfilled all of the technical requirements of the guidelines,

and (2) Dr. Tiffin had not been shown to have vone through

all the procedures detailed in American Psychological Asso

ciation, Inc., Standards for Educational and Psychological

Tests and Manuals (1966) (Plaintiffs Ex. 71), and that Al

bemarle had not presented evidence on extraneous issues not

raised in the District Court.

Other Courts of Appeals reaching the question have held

that an employer may satisfy the job relatedness standard of

Griggs independently of the specific requirements of the

EEOC guidelines. Castro v. Beecher,*459 F.2d 725, 737-38

(1st Cir. 1972): Guardians Ass’n v. Civil Service Commis

sion, 490 F.2d 400, 403 n. 1 (2nd Cir. 1973); United States

v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906, 913 (5th Cir. 1973).

The error of the Court of Appeals panel below was in equat