Turner v. City of Memphis Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Turner v. City of Memphis Jurisdictional Statement, 1960. f57f0109-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/877d829f-cb85-44e0-9dd7-dba62bbbd5fb/turner-v-city-of-memphis-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed January 28, 2026.

Copied!

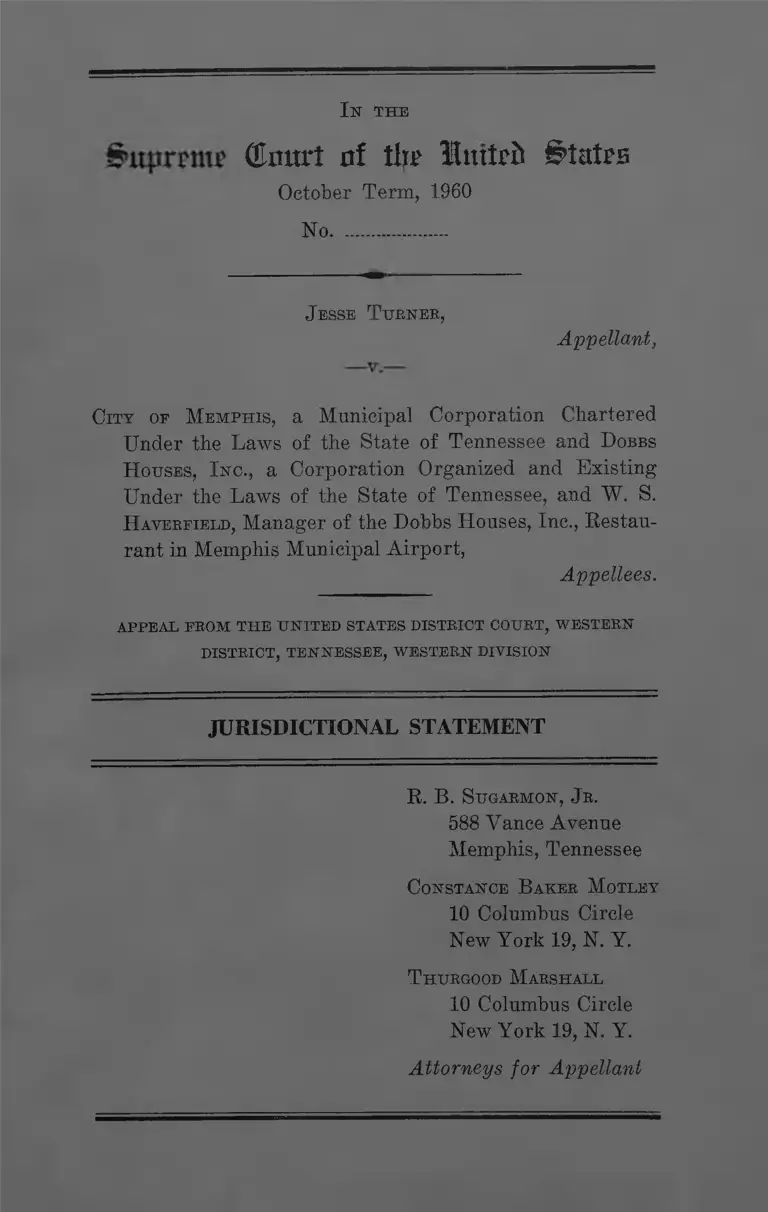

I n t h e

OInurl of tlî littlrJi %>UUb

October Term, 1960

No.....................

J esse T tjenee,

Appellant,

C ity of M e m p h is , a Municipal Corporation Chartered

Under the Laws of the State of Tennessee and D obbs

H o uses, I nc., a Corporation Organized and Existing

Under the Laws of the State of Tennessee, and W. S.

H aveefibld , Manager of the Dobbs Houses, Inc., Eestau-

rant in Memphis Municipal Airport,

Appellees.

APPEAL FEOM THE UNITED STATES DISTEICT COUET, WESTEEN

DISTEICT, TENNESSEE, WESTEEN DIVISION

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

R. B. SUGAEMON, J e.

588 Vance Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee

Constance B akbe M otley

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

T huegood M aeshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellant

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below ................... -....... -..................................... 2

Jurisdiction .......................................................................- 2

Statutes Involved .............................................................. 4

Question Presented ........... 7

Statement ........... 7

The Questions Are Substantial ................................-.... 10

The Court below abused its discretion in denying

injunctive relief ......... 10

The Court below abused its discretion in applying

the doctrine of abstention to this case .............. 11

Simultaneous Appeal Taken to Court of Appeals ....... 13

A p p e n d ix A :

District Court’s Per Curiam Opinion................... .A1-A3

District Court’s Order ............. .A4-A5

A p p e n d ix B :

Memphis Municipal Code, 1949, Vol. 1, §§151.26,

151.27, 151.40 ......................................................... - B1

Memphis Municipal Code, 1949, Vol. 2, §§3044.29,

3044.29(d) ...............................-......................-..... B2-B3

11

T able of Cases

PAGE

Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F.2d 97 (8th Cir. 1958) ............... 10

Alabama Public Service Commission v. Southern Ey.

Co., 341 U.S. 341 (1951) .................... .........................11,12

Browder v. Gayle, 142 P. Supp. 707 (M.D. Ala. 1956),

aff’d 352 U.S. 903 ......................................................... 13

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) .............................................................................. 12

Bryan v. Austin, 354 U.S. 933 (1957), 148 F. Supp. 563

(E.D. S.C. 1957) ..... 3

Burford v. Sun Oil Co., 319 U.S. 315 (1943) ...............11,12

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, No. 164,

Oct. Term 1960, decided April 17, 1961, -----

U.S. ....... 10,12

Bush V. Orleans Parish School Board, 138 F. Supp.

336 (E.D. La. 1956), mandamus denied, 351 U.S. 948

(1956) .............................................................................. 14

Chicago V. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Pe Ry. Co., 357

U.S. 77 (1958) ................................................................. 11

City of Greensboro v. Simkins, 246 F.2d 425 (4th Cir.

1957) .............................................................................. 10,11

City of Meridian v. Southern Bell Telephone, 358 U.S.

639 (1959) .....................................................................11,12

Clay V. Sun Insurance Co., 363 U.S. 207 (1960) ............11,12

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, 228 F.2d

853 (6th Cir. 1956), cert, denied 350 U.S. 1006 ......... 10

Coke V. City of Atlanta, 184 F. Supp. 579 (N.D. Ga.

1960) ................................................................................ 10

County of Allegheny v. Frank Mashuda Co., 360 U.S.

185 (1959) .......... 11

U1

PAGE

Department of Conservation and Development v. Tate,

231 F.2d 615 (4th Cir. 1956) 10

Derrington v» Plnmmer, 240 F.2d 922 (5th Cir. 1956),

cert, denied Casey v. Plummer, 353 U.S. 924.............. 10

Ex parte Poresky, 290 U.S. 30 (1933) .....................— 14

Harrison v. N.A.A.C.P., 360 U.S. 167 (1959), 159 F.

Supp. 503 (E.D. Va. 1958) .... 3,4,9,11,12

Henry v. Greenville Airport Commission, 284 F.2d 631

(4th Cir. 1960) ................................................................ 10

Lawrence v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp. 1004 (S.D. W.Va.

1948) ....................................... 10

Louisiana Power & Light Co. v. Thibodaux, 360 U.S.

25 (1959) ......................... -............................................. 11,12

Oklahoma Gas and Electric Co. v. Oklahoma Packing

Company, 292 U.S. 386 (1934) ...............................- 15

Martin v. Creasy, 360 U.S. 219 (1959) .......................... 11

Muir V. Louisville Park Theatrical Ass’n, 347 U.S. 971,

vacating and remanding 202 F.2d 275 (6th Cir.

1953) ........................................................................ 10,12,14

N.A.A.C.P. V . Bennett, 360 U.S. 471 (1959) .................. 3,4

Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 268 F.2d 78 (5th

Cir. 1959) ........................................................................ 13

Phillips V . United States, 312 U.S. 246 (1941) ........... 14

Propper V. Clark, 337 U.S. 472 (1949) .......................... 11

Public Utilities Commission v. United States, 355 U.S.

534 (1958) ...................................................................... 11

IV

PAGE

Eailroad Commission of Texas v. Pullman, 312 U.S. 496

(1941) ................. .......................................................... 11,12

Spector Motor Service v. McLaughlin, 323 U.S. 101

(1944) .............................................................................. 11

Stainback v. Mo Hock Ke Lok Po, 336 U.S. 368 ....... 14

The Vessel Tungus v. Skovgaard, 358 U.S. 588 (1959) .. 11

Union Tool Co. v. Wilson, 259 U.S. 107 (1922) ........... 10

S tatutes

Title 28, United States Code, §1253 ..........................— 3

Title 28, United States Code, §1343(3) ......................2, 8,13

Tennessee Code Ann., Vol. 9, §53-2120 ...................... 4, 8,12

Tennessee Code Ann., Vol. 9, §53-2121 ...........................4,12

Tennessee Code Ann., Vol. 11, §62-710...................... 6, 9,12

R egulatio ns

Department of Conservation of the State of Tennessee,

Division of Hotel and Restaurant Inspection, Regu

lation No. R-18(l). Approved June 18, 1952 .......... 4,8

O rdin ances

Memphis Municipal Code, 1949, Vol. 1, §§151.26, 151.27,

151.40 ................................................................................ 7

Memphis Municipal Code, 1949, Vol. 2, §§3044.29,

3044.29(d) ........................................................................ 6

I n t h e

#uprj?m? OInurt of t̂at^a

October Term, 1960

̂‘ ................... No.................. ...

J esse T tjenee,

Appellant,

-V -

CiTY OE M e m p h is , a Municipal Corporation Chartered

Under the Laws of the State of Tennessee and D obbs

H o uses, I nc., a Corporation Organized and Existing

Under the Laws of the State of Tennessee, and W. S.

H aveepield , Manager of the Dobbs Houses, Inc., Restau

rant in Memphis Municipal Airport,

Appellees.

APPEAL FEOM THE UNITED STATES DISTEICT COUET, WESTEEN

DISTEICT, TENNESSEE, WESTEEN DIVISION

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Appellant appeals from the judgment of the United

States District Court, Western District of Tennessee, West

ern Division, which denied, after notice and hearing, ap

pellant’s prayer for injunction enjoining appellees from

segregating Negroes in the Dobbs Houses Restaurant in

the Memphis Municipal Airport. Appellant submits this

statement demonstrating the jurisdiction of this Court upon

this appeal and further demonstrating that the question

presented is a substantial federal question.

Opinions Below

The per curiam opinion of the three-judge District Court,

consisting of Sixth Circuit Judge John D. Martin, District

Judge Marion S. Boyd, Western District Tennessee, West

ern Division, and District Judge William E. Miller, Middle

District Tennessee, Nashville Division, is not yet reported

and is, therefore, attached hereto as Appendix A.

Jurisdiction

This suit was brought in the United States District Court,

Western District Tennessee, Western Division, on April 1,

1960 by appellant Turner on behalf of himself and other

Negroes similarly situated. That Court’s jurisdiction was

invoked pursuant to provisions of Title 28, United States

Code, §1343(3). The relief sought was an injunction en

joining the City of Memphis and its lessee, Dobbs Houses,

from pursuing a policy, practice, custom and usage of

segregating appellant, and other members of his class, in

the use of certain airport facilities and with respect to

service in the Dobbs Houses Restaurant located therein.

Appellees’ answers admitted the segregation complained of

and the leasing of the restaurant facility to Dobbs Houses

but alleged that certain state statutes, a state agency reg

ulation, and several city ordinances either authorized or

required segregation in the airport’s restaurant and rest

room facilities. Appellees alleged that unless and until

these state statutes, regulation and ordinances were de

clared unconstitutional, segregation would be required by

them and prayed for the convening of a statutory three-

judge court to hear and determine this cause. However,

appellees also claimed that the restaurant operated by

Dobbs Houses, although leased from the city, is operated

“ as a jjrivate facility, to which the 14th Amendment

does not apply, and tlie operator has a legal right to en

force any rules and policies which it deems advisable in

regard to the seating of patrons, including the right to

seat and serve patrons in separate areas because of race

or color.” The District Court agreed with appellees that

this, was a case for a three-judge court which was sub

sequently convened. The per curiam opinion of that court

—staying this cause pending suit for declaratory judg

ment by appellant in the state courts for construction of

the statutes, regulation and ordinances involved—was ren

dered January 23, 1961. The order to this effect was en

tered on February 10, 1961. Notice of appeal was filed in

the District Court on March 1, 1961. Jurisdiction of this

Court to review this cause by direct appeal is conferred

by Title 28, United States Code, §1253 which provides as

follows:

Except as otherwise provided by law, any party

may appeal to the Supreme Court from an order

granting or denying, after notice and hearing, an in

terlocutory or permanent injunction in any civil ac

tion, suit or proceeding required by any Act of Con

gress to be heard and determined by a district court

of three judges.

The following decisions sustain the jurisdiction of this

Court to review the judgment on direct appeal: NAACP v.

Bennett, 360 U.S. 471 (1959) ■, Harrison v. NAACP, 360 U.S.

167 (1959) and Bryan v. Austin, 354 U.S. 933 (1957). In

the case of Bryan v. Austin, supra, the District Court

rendered a decision, similar to the decision below, invoking

the doctrine of equitable abstention in a case involving the

constitutionality of a South Carolina statute denying public

employment to NAACP members (E.D. S.C. 1957, 148 P.

Supp. 563). However, on direct appeal to this Court, this

Court vacated the order below on the ground that the case

had become moot, the statute sought to be enjoined having

been repealed after the decision of the District Court in

that case. In the case of NAACP v. Bennett, in which the

constitutionality of an Arkansas statute affecting the

NAACP was attacked, the District Court automatically

remanded the case to the state court for construction of

the statute (unreported). Upon appeal to this Court, the

judgment of the District Court was vacated and the case

remanded for consideration in the light of Harrison v.

NAACP, supra. In the Harrison case, a direct appeal was

taken to this Court from a judgment holding three Virginia

statutes unconstitutional (E.D. Va. 1958, 159 P.Supp. 503).

Upon appeal to this Court, the judgment was vacated and

the case remanded with instruction to retain jurisdiction

but to afford appellees a reasonable opportunity to bring

appropriate proceedings in Virginia courts for construc

tion of the statutes held unconstitutional. The exercise of

jurisdiction by this Court in these three cases sustains the

exercise of jurisdiction by this Court in this case.

Statutes Involved

Appellant did not rely upon or seek to enjoin the en

forcement of any state • statute, state regulation or city

ordinance in his complaint.

In the answers filed, appellees relied upon a state reg

ulation, promulgated by the Division of Hotel and Restau

rant Inspection, Department of Conservation of the State

of Tennessee, Regulation No. R-18(l), which provides:

Restaurants catering to both white and negro patrons

should be arranged so that each race is properly segre

gated. Segregation will be considered proper where

each race shall have sejDarate entrances and separate

facilities of every kind necessary to prevent patrons

of the different races coming in contact with the other

in entering, being served, or at any other time until

they leave the premises. (Tennessee Laws, Eules and

Eegulations for Eestaurants, Department of Conserva

tion, Division of Hotel and Restaurant Inspection. Ap

proved June 18, 1952.)

This regulation was adopted pursuant to the provisions of

§53-2121 of the Tennessee Code Ann., Vol. 9, which provides

as follows:

Rules and regulations authorized—Arbitration of in

consistencies.—The division is hereby authorized to

make such rules and regulations, including a code of

sanitation, as may be necessary to carry out the pur

poses of §§53-2101-53-2121 and to protect the public

health and safety. In any instances where there is

an inconsistency as between the requirements of the

division and those of a local county, or city, health

officer, such inconsistency is to be arbitrated by a three

(3) man board consisting of the director, the local

health officer concerned, and a third member to be

chosen by these two.

Appellees claimed that violation of the regulation is

declared to be a misdemeanor, punishable by fine, by

§53-2120, Tennessee Code Ann., Vol. 9, which provides as

follows:

Violation of regulations or provisions penalized.—

Every owner, manager, proprietor, agent, lessee, or

other person in charge of conducting any hotel or res

taurant, who shall fail or refuse to comply with any

of the provisions of §§53-2101-53-2121 or with the

rules and regulations promulgated by the division,

shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall be

fined not less than ten dollars ($10.00) nor more than

one hundred dollars ($100) for each offense, and each

day after sufficient notice has been given shall con

stitute a separate offense.

By amendment to their answer, appellee Dobbs Houses

also relied upon §62-710, Tennessee Code Ann., Vol. 11,

which provides as follows:

Right of owners to exclude persons from places of

public accommodation.—The rule of the common law

giving a right of action to any person excluded from

any hotel, or public means of transportation, or place

of amusement, is abrogated; and no keeper of any

hotel, or pnblic honse, or carrier of passengers for

hire (except railways, street, interurban, and com

mercial) or conductors, drivers, or employees of such

carrier or keeper, shall be bound, or under any obliga

tion to entertain, carry, or admit any person whom he

shall, for any reason whatever, choose not to entertain,

carry, or admit to his house, hotel, vehicle, or means

of transportation, or place of amusement; nor shall any

right exist in favor of any such person so refused ad

mission ; the right of snch keepers of hotels and public

houses, carriers of passengers, and keepers of places

of amusement and their employees to control the ac

cess and admission or exclusion of persons to or from

their public houses, means of transportation, and

places of amusement, to be as complete as that of

any private person over his private house, vehicle, or

private theater, or places of amusement for his family.

The answer of appellee. City of Memphis, relied upon

a city ordinance requiring segregation in rest room facili-

ties.‘ As the basis for enforcing this ordinance, the City

also cited ordinances extending the police power of the

^Memphis Municipal Code, 1949, Vol. 2, §§3044-29 and 3044-

29(d).

City to the airport,^ prohibiting disorderly conduct at the

airport,® and providing for the removal of any person

using the airport in violation of the law relating thereto.*

These ordinances are set forth in Appendix B. Appellant

is informed that the rest rooms in the Memphis Municipal

Airport are no longer segregated. The only facility still

segregated is the Dobbs Houses Restaurant.

Question Presented

Whether the three-judge court below, in a case involving

segregation of Negroes by the lessee of a municipally-

owned airport restaurant, abused its discretion in refusing

to issue a permanent injunction enjoining such segrega

tion and in postponing exercise of its jurisdiction pending

suit for declaratory judgment by appellant in the state

courts for interpretation of statutes, regulation and ordi

nances pleaded by appellees.

Statement

The facts in this case are not disputed. The appellant,

Jesse Turner, is an adult Negro citizen of the United

States and of the State of Tennessee, residing in Memphis,

Tennessee. He is the executive vice-president and cashier

of the Tri-State Bank in Memphis. He is also an elected

official, holding the position of member of the Executive

Committee of the Shelby County Democratic Party. In con

nection with his work, he uses the Memphis Airport ap

proximately three or four times a year. On April 28, 1959,

he and two business associates went into the main dining

room of the Dobbs Houses Restaurant in the airport. Upon

entering the restaurant he was stopped by a hostess and

® Ibid., Vol. 1, §151.26.

̂Ibid., Vol. 1, §151.27.

* Ibid., Vol. 1, §151.40.

8

directed by her to a small room reserved for Negroes ad

jacent to the main dining room. Mr. Turner requested

that he be allowed to see the manager. Appellant was

addressed by appellee Haverfield who identified himself as

the manager and said that Negroes are not served in the

main dining room but in a separate area reserved for them.

Appellant declined the invitation to be served in the small

room reserved for Negroes. Thereafter, on October 29,

1959, upon returning from Atlanta as a passenger on East

ern Air Lines, appellant again requested service in the

main dining room of the Dobbs Houses Restaurant. Again

he was informed by the manager, Mr. Haverfield, that

Negroes could not be served in the main dining room.

When he asked why he could not be served in the main

eating facility, he was told by the manager that the state

law prevented it.

This suit was commenced by appellant on April 1, 1960

to restrain the enforcement of this segregation. Jurisdic

tion was invoked pursuant to the provisions of Title 28,

United States Code, §1343(3). The complaint did not rely

upon or seek to enjoin the enforcement of any state statute,

state regulation or city ordinance. On April 21, 1960, all

appellees filed answers in which they admitted all the seg

regation complained of and the leasing of the restaurant

to Dobbs Houses but israyed the convening of a three-judge

court on the ground that there had been promulgated a

valid regulation of the Division of Hotel and Restaurant

Inspection, Department of Conservation of the State of

Tennessee. Regulation No. R-81(l), and claimed that a

violation of the regulation would constitute a misdemeanor

punishable by fine under p3-2120. Tennessee Code Anno

tated. Appellees aUeged that, unless and until the regula

tion shall have been declared unconstitutional, their duty

is to object to desegregation of the races in the airport

restaurant, since such desegregation would be a violation

9

of the laws of the State of Tennessee and a violation of

Paragraph 20 of the lease between the City and Dobbs

Houses requiring the latter to abide by all state laws.

Appellees also claimed that operation of the restaurant

is a private facility to which the 14th Amendment does not

apply, and that Dobbs Houses has the legal right to enforce

any rules and policies which it seems desirable in regard

to seating patrons, including segregation on account of race.

Appellee Dobbs Houses also relied upon §62-710 of the

Tennessee Code granting owners the right to exclude per

sons from certain places of public accommodation.

There is no question that the purpose of the lease of the

restaurant facility to Dobbs Houses was to provide food

service for airline passengers and the members of the public

using the airport.

On May 18, 1960, appellant filed a motion for summary

judgment which came on for hearing on June 3, 1960. The

single-judge District Court hearing the motion ruled that

it could not act on the motion because the case was one for

a three-judge court. Thereafter, on June 6, 1960 appellant

renewed his motion for summary judgment. On June 9,

1960, an order was entered by Chief Judge McAllister of

the Sixth Circuit designating the three members of the

court below. The case came to trial before that court on

November 9, 1960. Subsequently, on January 23, 1961 a

per curiam opinion was rendered in which the court, relying

upon Harrison v. NAACP, 360 U.S. 167 (1959), ruled that

“in the light of the Harrison case, with its clear enunciation

of the doctrine of abstention in cases of this type, we hold

that the plaintiff’s cause herein shall be stayed joending the

prosecution of a proper declaratory judgment suit to be

brought by the plaintiff in the courts of Tennessee for the

purpose of obtaining an interpretation of the state statutes,

regulations and city ordinances under consideration herein.”

10

The Questions Are Substantial

The Court below abused its discretion in denying

injunctive relief.

The right of Negro residents to service, without discrim

ination against them because of race, in publicly owned fa

cilities leased to private persons for operation for the

benefit of the public is a right guaranteed by the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States. Burton v. Wilmington Park

ing Authority, No. 164, Oct. Term 1960, decided April 17,

1 9 6 1 ̂ __ U.S. ----- ; Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical

Ass’n, 347 U.S. 971, vacating and remanding 202 F.2d 275

(6th Cir. 1953). This right has been upheld by the Courts

of Appeal and the District Courts. Aaron v. Cooper, 261

F.2d 97 (8th Cir. 1958); City of Greensboro v. Simkins,

246 F.2d 425 (4th Cir. 1957); Derrington v. Plummer, 240

F.2d 922 (5th Cir. 1956); cert, denied Casey v. Plummer,

353 U.S. 924; Department of Conservation v. Tate, 231

F.2d 615 (4th Cir. 1956); Coke v. City of Atlanta, 184 F.

Supp. 579 (N.D. Ga. 1960); Lawrence v. Hancock, 76 F.

Supp. 1004 (S.D. W.Va. 1948).

There was no dispute as to the facts in this case. All

appellees admitted that Negroes are segregated in the

Dobbs Houses Restaurant. The leasing was also admitted.

The lease specifically requires Dobbs Houses to serve the

public food at prices prevailing in Memphis and to make

soft drinks and other items available to the public.

Failure to apply well settled principles of law to undis

puted facts is an abuse of discretion in law. Union Tool Co.

V. Wilson, 259 U.S. 107 (1922); Henry v. Greenville Airport

Commission, 284 F. 2d 631 (4th Cir. 1960); Clemons v.

Board of Education of Hillsboro, 228 F. 2d 853 (6th Cir.

11

1956), cert. den. 350 U.8. 1006. Consequently, the court

below abused its discretion in failing to issue a permanent

injunction as prayed,

The Court below abused its discretion in applying the

doctrine of abstention to this case.

The doctrine of abstention which was invoked by the

court below has been held by this Court to be a “extraordi

nary and narrow exception to the duty of a District Court

to adjudicate a controversy properly before it.” County

of Allegheny v. Frank Mashuda Co., 360 U.S. 185, 188

(1959). See also Propper v. Clark, 337 U.S. 472 (1949);

Public Utilities Commission v. United States, 355 U.S. 534

(1958); Chicago v. Atchison, Topeka d Santa Fe R. Co., 357

U.S. 77 (1958); The Vessel Tungus v. Skovgaard, 358 U.S.

588 (1959); NAACP v. Bennett, 360 U.S. 471 (1959). I t is a

doctrine which involves an exercise of discretion in “ex

ceptional circumstances” which certainly are not present

in the instant case. County of Allegheny v. Frank Mashuda

Co., supra, at 188-189, but which were present and identified

in those cases to which the doctrine has been applied. Rail

road Commission of Texas v. Pullman, 312 U.S. 496 (1941) ;

Burford v. Sun Oil Co., 319 U.S. 315 (1943); Spector Motor

Service v. McLaughlin, 323 U.S. 101 (1944); Alabama Public

Service Commission v. Southern By. Co., 341 U.S. 341

(1951); City of Meridian v. Southern Bell Telephone, 358

U.S- 639 (1959); Louisiana Power and Light Co. v. Thibo-

daux, 360 U.S. 25 (1959); Harrison v. N.A.A.C.P., 360 U.S.

167 (1959); Martin v. Creasy, 360 U.S. 219 (1959); Clay v.

Sun Insurance Go.,363 V .^.201 (1960).

In the Pullman case this Court made clear that the doc

trine is applicable to those cases where “constitutional ad

judication plainly can be avoided if a definitive ruling on

the state issue would terminate the controversy” (at 498),

12

pointing out that, “Federal courts should avoid a tentative

answer which may be displaced by a state adjudication”

(at 500). This test was employed in the Spector case, supra,

the Alabama Public Service Commission case, supra, in

City of Meridian v. Southern Bell Telephone, supra, Harri

son V. N.A.A.C.P., supra, and Clay v. Sun Insurance Co.,

supra, when the doctrine was applied.

Here it is plain that a definitive ruling on the state law

relied on by Dobbs Houses (62-710 and 53-2120) and the

statute (53-2121) and regulation (No. E-18(l)) relied on

by all appellees would not terminate the controversy as to

whether the lessee here is subject to the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

In the Pullman case this Court also ruled that the absten

tion doctrine should be applied by District Courts where

its invocation would avoid “needless friction with state

policies” (at 500). This criterion was used to sustain ap

plication of the doctrine in Burford v. Sun Oil Co., supra,

where only domestic policy issues were involved, in Ala

bama Public Service Commission v. Southern By., supra,

involving predominantly local factors, and in Louisiana

Light and Power Co. v. Thibodaux, supra, where the issue

touched upon the relationship of City and State.

Again, it is too plain to require argument that this case

does not fall into this latter category. The state policy of

segregation in a public airport restaurant is constitutionally

void, not only as to the state, but as to its lessee, in this

instance. Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, supra;

Muri V. Louisville Park Theatrical Ass’n, supra; Brown v .

Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). The

issuance of an injunction here would have upheld the Fed

eral constitutional policy so often reaffirmed by this Court.

13

As the District Court said in Browder v. Gayle (M.D.

Ala. 1956), 142 F. Supp. 707, aff’d 352 U.S. 903, “The short

answer is that doctrine has no application where the plain

tiffs complain that they are being deprived of constitutional

civil rights for the protection of which the Federal courts

have a responsibility as heavy as that which rests on the

State courts” (at 713). And, “No cause for abstention by

the federal court is shown merely because a suit is brought

against state officials whose conduct may be affected by

untested state legislation. I t is only when the federal court

is called on to interpret such state statutes or rule on its

constitutionality that the rule applies.” Orleans Parish

School Board v. Bush, 268 F.2d 78, 80 (5th Cir. 1959).

Appellant, therefore, believes that the questions pre

sented are substantial and that they are of public impor

tance.

Simultaneous Appeal Taken to Court of Appeals

Appellant invoked the jurisdiction of the District Court

pursuant to Title 28, United States Code, §1343(3) alleging

that appellees, acting under color of the laws of the State

of Tennessee and ordinances of the City of Memphis, were

pursuing a policy, practice, custom and usage of segregating

Negroes and white persons in the Dobbs Houses Restaurant

in the Airport. Appellant did not rely upon or seek to have

the District Court enjoin the enforcement of any specific

state statute or regulation or city ordinance. Appellant’s

theory was that the City as well as its lessee of municipal

property, which is to be operated for the benefit of the

public, are clearly subject to the prohibitions of the Four

teenth Amendment—state statutes, regulations, or city ordi

nances to the contrary, notwithstanding, same being clearly

unconstitutional in the light of prior recent decisions of this

14

Court. Muir v. Louisville Parle Theatrical Ass’n, supra.

Consequently, appellant conceived that an injunction could

be entered by the District Court enjoining Dobbs Houses

and the City of Memphis from segregating Negroes without

bringing about any sudden doom of state-wide policy about

which there might he some genuine questions as to consti

tutionality. E x parte Poreshy, 290 IJ.S. 30 (1933); Bush

V. Orleans Parish School Board, 138 F. Supp. 336 (E.D.

La. 1956), mandamus denied, 351 U.S. 948 (1956).

Subsequently, a three-judge court was convened and the

case came on for trial after due notice. Thereafter, the

court applied the abstention doctrine. Since appellant be

lieves that there is some doubt as to whether this case is

properly one for a three-judge court, appellant has taken

a simultaneous appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit as a precaution against the possibility that this

Court might find that a three-judge court was improperly

convened and the appeal should have been taken to the

Court of Appeals from the District Court’s application of

the abstention doctrine. If this Court were to so rule, the

time within which to appeal to the Court of Appeals would

have expired. Appellant is preparing to docket an appeal

in that Court by May 25, 1961 (the time having been duly

extended by order of Judge Boyd). Appellant will then

move the Sixth Circuit for an order staying all proceedings

in that appeal pending this Court’s disposition of the instant

appeal. Stainbach v. Mo Hoch Ke Loh Po, 336 IJ.S. 368,

380-381. See also, Phillips v. United States, 312 U.S. 346,

15

355 (1941) and OMahoma Gas and Electric Co. v. Oklahoma

Packing Company, 292 U.S. 386 (1934).

Respectfully submitted,

R. B. SUGAEMOIT, J b .

588 Vance Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee

CoNSTAisroE B akeb M otley

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

T hxjbgood M aeshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellant

A1

APPENDIX A

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

P oe t h e W e st e e n D istbict op T e n n e sse e

W e st e e n D ivision

Civil Action No. 3934

J esse T xjenee,

Plaintiff,

—vs.-

CiTY OP M e m p h is , D obbs H o uses, I n c ., an d

W . S. H avbepield ,

Defendants.

B e f o r e

M a e t in , Circuit Judge,

B oth a n d M iix e b , District Judges.

P e e CuEiAiL This is a .suit by the plaintiff, w h o is a Negro

residing in Memphis, Tennessee, on behalf of himself and

others similarly sitnated, asking injnnetive relief against

the defendants, City of Memphis, Dobbs Houses, Inc., and

the Manager of the latter concern’s restaurant in the

Memphis Municipal Airport.

The plaintiff seeks under Title 42, U.S.C.A., Sections 1981

and 1983, to secure certain rights, privileges and immuni

ties guaranteed by the Constitution and laws of the United

States. More particularly, the plaintiff is seeking to per

manently enjoin the defendants from continuing to operate

the eating and rest room facilities located in the airport

aforesaid on a racially segregated basis.

A2

Plaintiff claims that he was denied service in the main

dining room of the Dobbs Houses Restaurant at the airport

because of his race and color, pursuant to the policy, prac

tice, custom and usage of the defendants.

The defendants contend that there are certain statutes

and regulations of the State of Tennessee and ordinances

of the City of Memphis which require that separate facili

ties for the Negro and White races be maintained at the

Memphis Municipal Airport. In this connection, they con

tend that this Court should apply the principle of absten

tion, thereby giving the Courts of Tennessee an opportunitj^

to declare the rights of the plaintiff thereunder.

In Harrison v. NAACP, 360 U.S. 167 the United States

Supreme Court, in speaking on the doctrine of abstention

of federal courts to permit action by the state courts, stated

on page 176: “This now well-established procedure is aimed

at the avoidance of unnecessary interference by the federal

courts with proper and validly administered state concerns,

a course so essential to the balanced working of our federal

system. To minimize the possibility of such interference

a ‘Scrupulous regard for the rightful independence of state

governments . . . should at all times actuate the federal

courts,’ Matthews v. Rodgers, 284 U.S. 521, 525, as their

contribution . . . in furthering the harmonious relation

between state and federal authority . . . ’ Railroad Comm’n.

V. Pullman Co., 312 U.S. 496, 501. In the service of this

doctrine, which this Court has applied in many different con

texts, no principle has found more consistent or clear ex

pression than that the federal courts should not adjudicate

the constitutionality of state enactments fairly open to

interpretation until the state courts have been afforded a

reasonable opportunity to pass upon them. (Citing numer

ous cases). This principle does not, of course, involve the

abdication of federal jurisdiction, but only the postpone

ment of its exercise; it serves the policy of comity inherent

A3

in the doctrine of abstention; and it spares the federal

courts of unnecessary constitutional adjudication.”

Thus, in the light of the Harrison case, with its clear

enunciation of the doctrine of abstention in cases of this

type, we hold that the plaintiff’s cause herein shall he

stayed pending the prosecution of a proper declaratory

judgment suit to be brought by the plaintiff in the courts

of Tennessee for the purpose of obtaining an interpretation

of the state statutes, regulations and city ordinances under

consideration herein.

s / J o h n D. M aetin

Circuit Judge

s / M arion S. B oyd

District Judge

s / W illia m G. M iller

District Judge

A4

Order

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

W estern" D iv isio n of T e n n e sse e

W e st e r n D istrict

Civil Action No. 3934

J esse T u r n e r ,

Plaintiff,

-vs.-

CiTY OF M e m p h is , et al.,

Defendants.

This Cause, came on to be heard on the 9th day of

November, 1960, upon the pleadings, testimonies, briefs

and arguments of the parties; and it appearing to the Court

for the reason set forth in opinion heretofore filed that

said Cause should be held in abeyance pending the Declara

tory Judgment suit to he brought by Plaintiffs in the Ten

nessee Courts seeking an interpretation of the State stat

utes under consideration.

I t I s , T h erefo re , Ordered, A djudged a n d D ecreed , that

said Cause be and the same is hereby held in abeyance

A 5

pending the filing of such suit and an interpretation of the

State statutes involved herein.

J o h n D. M a etin

U. 8. Circuit Judge

M aeion S . B oyd

District Judge

W illia m E. M il l e e

District Judge

A ppeoved :

R . B. S ugaemon

Attorney for Plaintiff

F. B. G ia n o tti, J e.

F ea n k

Attorneys for Defendants.

B1

APPENDIX B

Memphis Municipal Code, 1949, Vol. 1.

Section 151.26. Police Powers. All the powers of

the police officers of the city, derived from whatever

source, are hereby extended to the area embraced

within the Memphis municipal airport as the same now

exists, or as the same may he hereafter established.

Section 151.27. Disorderly, etc., conduct. No person

shall commit any disorderly, obscene, indecent or un

lawful act, or commit any nuisance on the airport.

Section 151.40. Violation of regulations; misdemean

ors. Any person operating or handling any vehicle,

equipment, or apparatus or using the airport or any

of its facilities in violation of this chapter, or refusing

to comply herewith, may be removed from the airport,

and deprived of and refused the further use of the air

port and its facilities for such length of time as may be

determined by the airport manager.

Any offense declared to be a misdemeanor by ordi

nance of the city shall be a misdemeanor if committed

on the Memphis municipal airport, and shall he punish

able as provided by the ordinances of the city pertain

ing to such violation.

Memphis Municipal Code, 1949, Vol. 2.

Section 3044.29. General requirements for water

closets, urinals and lavatories in all buildings other

than one- and two-family dwellings and multi-family

dwelling units. In all buildings other than one- and two-

family dwellings and multi-family dwelling units, there

shall he one or more water closets in conformity with

B2

the general requirements of this section, together with

the required number of urinals and lavatories accord

ing to the occupancy, as provided in the following sec

tions. The lavatories shall be in an ante-room or com

partment when more than one commode or urinal is

required, or provided. The space provided for each

fixture and other details shall be as required in Section

3044.27.

(d) Separate facilities required for ivhite and black

races and for both sexes. Where buildings are used

by both white and black races, separate facilities shall

be provided for each race, and separate facilities shall

be provided for both sexes of each race, where both

men and women use any such building.

(e) Proper signs to be affixed. Proper signs shall

be affixed on water closets indicating those provided for

each race and for each of the sexes, in all buildings or

places where such separate facilities are required.

sa